Abstract

Background

Conventional PET imaging has usually been limited to a single tracer per scan. We propose a new technique for multi-tracer PET imaging that uses dynamic imaging and multi-tracer compartment modeling including an explicitly derived arterial input function (AIF) for each tracer using blood sampling spectroscopy. For that purpose, at least one of the co-injected tracers must be based on a non-pure positron emitter.

Methods

The proposed technique was validated in vivo by performing cardiac PET/CT studies on three healthy pigs injected with 18FDG (viability) and 68Ga-DOTA (myocardial blood flow and extracellular volume fraction) during the same acquisition. Blood samples were collected during the PET scan, and separated AIF for each tracer was obtained by spectroscopic analysis. A multi-tracer compartment model was applied to the myocardium in order to obtain the distribution of each tracer at the end of the PET scan. Relative activities of both tracers and tracer uptake were obtained and compared with the values obtained by ex vivo analysis of excised myocardial tissue segments.

Results

A high correlation was obtained between multi-tracer PET results, and those obtained from ex vivo analysis (18FDG relative activity: r = 0.95, p < 0.0001; SUV: r = 0.98, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

The proposed technique allows performing PET scans with two tracers during the same acquisition obtaining separate information for each tracer.

Keywords: Arterial input function, Positron emission tomography, Multi-tracer PET, Gamma spectroscopy

Background

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a diagnostic molecular imaging technique that allows in vivo monitoring of metabolic processes within the body based on the biodistribution of a radiotracer that is administered to the patient. The wide variety of available radiotracers provides access to different biological aspects such as glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, hypoxia, or blood flow. Among the different radiotracers available, each one shows strengths and limitations for a particular clinical application [1]. Therefore, the nuclear medicine physician selects the tracer that will provide the most specific and reliable information for the patient under study. However, in many clinical cases, diagnostic accuracy can be increased considerably if complementary information is obtained from different tracers. An example of diagnosis using multiple tracers is found in ischemic heart disease, which includes evaluation of myocardial blood flow (MBF) using tracers like 13NH3, H215O, or 82Rb and assessment of myocardial metabolism and viability using 18FDG. In this way, a better understanding of the pathophysiology of ischemic heart disease is obtained [2].

Conventional PET imaging has usually been limited to a single tracer per scan. Therefore, in order to perform PET examinations with multiple tracers on the same patient, different scans should be performed sequentially if the half-life of one tracer is short enough (i.e., tracers based on 13N, 15O, or 82Rb) to allow fast clearance of the tracer before the next tracer is administered. Otherwise, scans can be performed in different days. These procedures lead to extended scan time and to increased cost and complexity of patient management. Those limitations can be diminished by performing PET imaging on patients that have been administered with multiple radiotracers. However, multi-tracer PET imaging is still a challenging approach as annihilation photon pairs emitted from either tracer are indistinguishable. Therefore, some extra information is needed to disentangle the signal coming from each tracer.

Two main strategies have been proposed so far in order to enable the possibility of performing PET scans with multiple tracers simultaneously. The first approach uses dynamic imaging with staggered injections. In this case, a multi-tracer compartment model is used to separate the contribution from each tracer. However, different constraints must be applied on the kinetic behavior in order to separate each tracer contribution from the multi-tracer PET signal [3–5]. In the second approach, at least one of the injected tracers must be labeled with a radioisotope that emits a prompt gamma in addition to the positron, which can be detected in coincidence with the annihilation photons [6]. With this additional information, the signal coming from both tracers can be isolated by energy discrimination within the PET scanner. However, a relatively high (> 10%) branching ratio of the prompt gamma is required in this case, reducing the list of candidate radioisotopes to 124I or those with similar prompt gamma branching ratio.

In this study, we propose a new technique for multi-tracer PET imaging that uses dynamic imaging and multi-tracer compartment modeling including an explicitly derived arterial input function (AIF) for each tracer. For that purpose, PET studies should be performed with at least one of the co-injected tracers based on a non-pure positron emitter [7], i.e., which produces additional gamma emissions. In order to end up with a separate AIF for each radiotracer, blood samples are collected during the acquisition and further analyzed by gamma spectroscopy. Once separate AIFs are obtained, multi-tracer compartment modeling is applied to determine the kinetic parameters associated with each tracer. Using this methodology, no constraints to the kinetic behavior are required. In addition, clinically promising isotopes like 68Ga [8], which has a very low branching ratio for the extra gamma photons, can be combined with other regular isotopes like 18F. The proposed methodology was implemented and validated in pigs by a combination of two tracers for cardiac PET imaging, namely 68Ga-DOTA and 18FDG. While 18FDG is a very well-known tracer used in myocardial viability studies among other cardiac applications [9], 68Ga-DOTA has been recently proposed as a new PET tracer for MBF and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) determination [10–13] as well as for pulmonary blood flow [14].

Methods

Study design and experiment overview

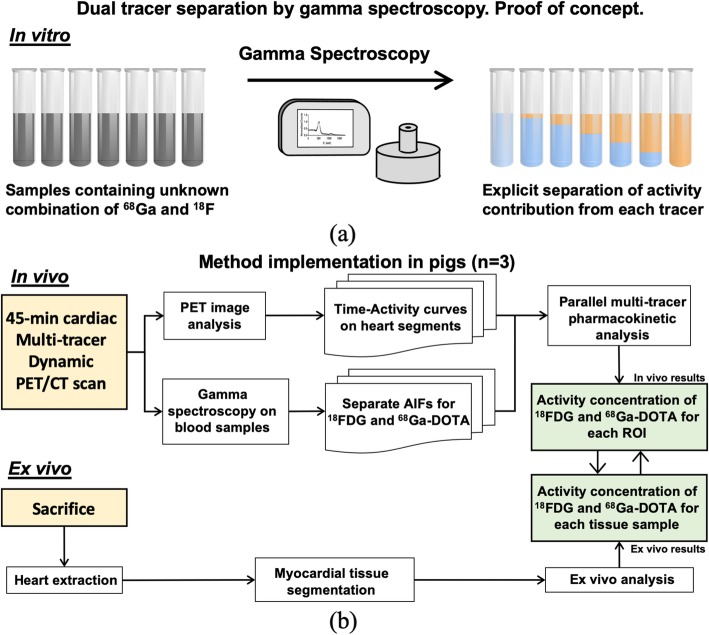

In the first place, in vitro studies were performed as a proof of concept of our proposed methodology. Samples containing unknown mixtures of two isotopes (18F and 68Ga) were analyzed by means of gamma spectroscopy. Several calibration procedures were carried out in order to obtain the individual contribution of each tracer. For in vivo studies, 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA tracers were administered to healthy pigs, and dynamic PET scans were performed. Manual blood samples were collected throughout the PET scan and analyzed by gamma spectroscopy to obtain a separate AIF for each tracer. A multi-tracer compartment model was applied to the dynamic PET imaging using those explicitly separated AIFs. Finally, the model was used to determine the uptake of each tracer at the end of the PET scan on each segment of the myocardium, and the results were compared with those obtained ex vivo directly from myocardial tissue. To do so, animals were sacrificed, and the heart was excised in segments that were further analyzed to determine the individual uptake of each tracer ex vivo. A schematic drawing of the experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the study design. a Firstly, our proposed tracer separation methodology based on gamma spectroscopy was evaluated in vitro as a proof of concept. A calibration protocol was established to obtain the activity concentrations of each radioisotope for samples containing an unknown combination of 18F and 68Ga. b Afterwards, this methodology was implemented in vivo. To do so, three pigs underwent 45-min cardiac dynamic PET/CT scans in which 68Ga-DOTA and 18FDG were injected with a 5-min time gap. After PET/CT examinations, the animals were sacrificed, and their hearts excised, divided into segments, and analyzed to obtain the activity concentration of 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA inside each segment. These results were compared against those obtained in vivo by parallel multi-tracer pharmacokinetic on the same regions of interest (ROIs) of their hearts. Explicitly separated AIFs needed for the pharmacokinetic analysis were obtained with our proposed method by gamma spectroscopy of a set of blood samples withdrawn during the scan

In vitro tracer separation by gamma spectroscopy

We analyzed different combinations of two tracers, one based on a pure positron emitter (18F) and the other one based on a non-pure positron emitter (68Ga). While 18F only emits annihilation photons of 511 keV, 68Ga emits additional photons, but only those emitted at 1.077 MeV have a significant contribution (3.22%). Therefore, a sample containing an unknown combination of both isotopes could be analyzed by means of gamma spectroscopy. To determine the concentration of each tracer in a sample, a methodology was developed using a well counter (Wallac 1470 Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) configured to record events during 1 min at different energy windows simultaneously, one of them covering the entire energy spectrum (200–2000 keV, hereafter named as W200–2000) and the other one covering only high-energy emissions (900–2000 keV, hereafter named as W900–2000). Dead time correction and background subtraction were implemented but not decay correction due to the unknown isotope combination. The amount of 68Ga and 18F contained in the sample was derived using the ratio (QS) between events recorded at W200–2000 and W900–2000 energy windows as explained below.

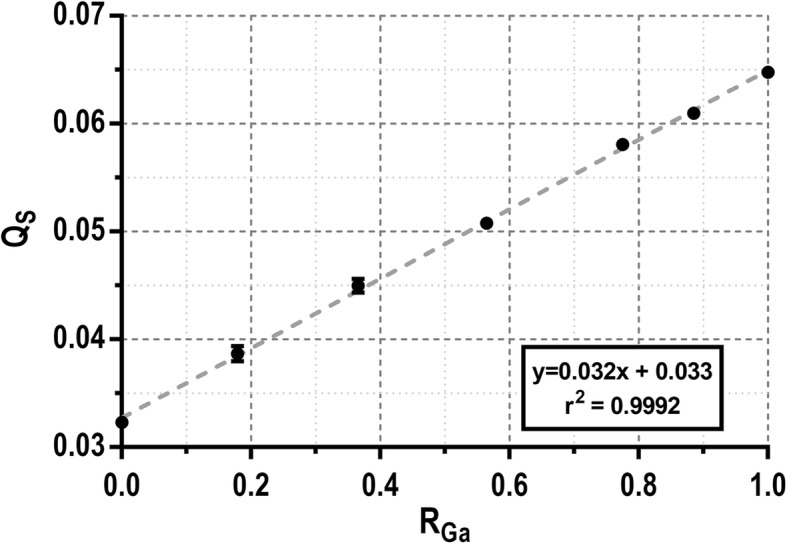

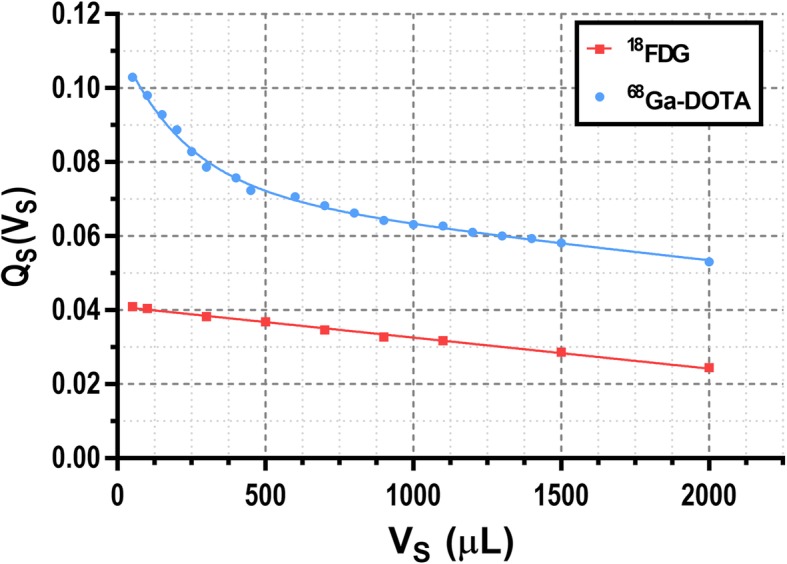

The relationship between QS and the relative activity of 68Ga (RGa) and 18F (RF) in a sample (i.e., the individual fractional contribution of 68Ga and 18F to the total activity of the sample) was calibrated using a set of 68Ga/18F mixtures. Seven 1-ml samples were prepared containing 68Ga to 18F activity ratios 1:0, 9:1, 4:1, 3:2, 2:3, 1:4, and 0:1. These samples were analyzed in the well counter, and the QS values were represented against the known relative activities obtaining a linear relationship (see Fig. 2). Decay correction was applied to recorded values. Since in the subsequent animal studies, blood samples may be collected with different sample volumes (VS); a calibration had to be performed to account for variations in the detection efficiency of gamma photons with different energy and different geometrical distribution. For that purpose, QS values were recorded using pure 18F (QF(V)) and 68Ga (QGa(V)) samples (~ 20 kBq each) with volumes ranging from 50 to 2000 μl (see Fig. 3). For known QF(V) and QGa(V) within a sufficiently wide volume range, RGa and RF can be obtained for a sample with known volume Vs by solving the following equations:

Fig. 2.

Calibration of QS values of a set of 1 ml samples with mixed 68Ga and 18F in different activity ratios. The linear fit (dashed line) shows an excellent linear correlation (r2 = 0.9992) between both datasets

Fig. 3.

Variation of QS values measured with the well counter for pure 18F (red squares) and 68Ga (blue circles) with different sample volumes (VS). Results were fitted to a straight line and a sum of two exponentials respectively in order to obtain the QS values for different volumes

| 1a |

| 1b |

Afterwards, the absolute activity concentrations of each tracer (i.e., AF and AGa) can be obtained for a sample of known volume VS as follows:

| 2a |

| 2b |

where Atot is the total activity of the sample and can be derived from the following equation:

| 3 |

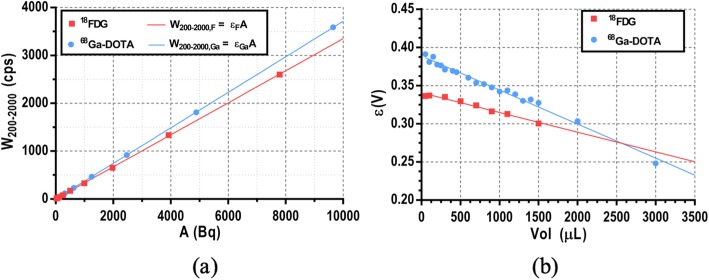

where WF and WGa are the events recorded for each isotope, and εF and εGa are volume-dependent calibration factors obtained from pure 18F and 68Ga samples respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

a Calibration profiles obtained in the well counter for 300-μl pure 18F (red squares) and 68Ga (blue circles) samples with different activity values using the full energy window (W200–2000). Each dataset was fitted to a straight line with y-intercept forced to be 0 obtaining the calibration factors εF = 0.335 cps Bq−1 and εGa = 0.371 cps Bq−1 at this volume. b Variation of calibration factors with the sample volume for 18F (εF) and 68Ga (εGa)

Finally, before the kinetic model can be individually applied for each tracer, AF and AGa were converted to β+decays·s−1 ml−1 multiplying by the branching ratio in order to match the units obtained from the PET images.

Following this procedure, explicitly separated AIFs can be obtained from a multi-tracer PET scan by analyzing a set of blood samples withdrawn from the subject throughout the study and obtaining AF and AGa for each timepoint. The feasibility of this methodology was investigated in animal studies as described below.

Animal protocol

The in vivo study was conducted according to the guidelines of the current European Directive and Spanish legislation and approved by the regional ethical committee for animal experimentation. Three healthy female white large pigs (mean weight = 45 ± 4 kg) were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg), and midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) and maintained by continuous intravenous infusion of ketamine (2 mg/kg/h), xylazine (0.2 mg/kg/h), and midazolam (0.2 mg/kg/h). Oxygen saturation levels via pulse oximetry and electrocardiogram signal were monitored throughout the study. The coccygeal artery of the animal was cannulated and connected to a peristaltic pump placed as close as possible to minimize blood dispersion inside the tubing.

PET/CT image acquisition

PET/CT images were acquired using a Gemini TF-64 scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Each imaging study consisted of a low-dose CT scan (120 kV, 80 mA) followed by a dynamic 45-min list mode PET acquisition in a single bed position covering the entire heart. 18FDG (155 ± 12 MBq) and 68Ga-DOTA (142 ± 33 MBq) were injected 1 and 6 min after PET scan was started respectively. Both radiotracers were prepared in 6 ml and infused at a rate of 1.0 ml/s through a peripheral ear vein, followed by a 6-ml saline flush at the same rate. Arterial blood was withdrawn during the PET scan through a 1.6-mm internal diameter peristaltic pump tubing (TYGON-XL6, Saint-Gobain, Courbevoie, France) at 5 ml/min for the first 7 min and then at 2 ml/min for the rest of the scan. Blood collection from the coccygeal artery started immediately after the first radiotracer injection and continued during the whole study. During the first 12 min, blood was collected into sample tubes according to the following scheme: 20 × 5 s, 8 × 10 s, 6 × 20 s, 24 × 5 s, 6 × 10 s, 6 × 20 s, and 4 × 30 s. After that, 11 more samples were collected for 1 min with 2-min gaps between consecutive samples. PET images were reconstructed with a voxel size of 4 mm × 4 mm × 4 mm using a 3D RAMLA reconstruction algorithm in 84 consecutive frames (1 × 60 s, 25 × 5 s, 8 × 10 s, 4 × 20 s, 24 × 5 s, 3 × 10 s, 5 × 20 s, 5 × 60 s, 4 × 120 s, 4 × 180 s, and 1 × 300 s, total scan time 45 min). Corrections for dead time, scatter, and random coincidences were applied as implemented on the scanner. Decay and branching ratio corrections were not applied as the amount of 68Ga and 18F on each voxel is unknown, and their values differ (t1/2(68Ga) = 67.77 min and t1/2(18F) = 109.77 min, Br,Ga = 0.891 and Br,F = 0.967). Therefore, reconstructed images were expressed as β+decays·s−1 ml−1.

Separate AIF derivation from blood sample gamma spectroscopy

After each PET/CT examination, the vials containing the collected blood samples were centrifuged briefly to provide a reproducible geometrical distribution of the blood before performing the measurements in the well counter. The volume for each blood sample was determined as the weight difference between empty and filled vial and applying a blood density of 1.03 g/ml [15]. Then, the individual activity concentration of 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA (AF and AGa) for each blood sample was calculated using (1–3). Consequently, the AIFs obtained from blood samples for each tracer (AIFBS,F and AIFBS,Ga) were derived as time series of these values.

Delay and dispersion corrections were applied to AIFBS,F and AIFBS,Ga using the image-derived AIF (AIFID) as this one lacks delay and dispersion. AIFID was obtained from an 8-mm diameter cylindrical volume of interest (VOI) drawn in the descending thoracic aorta over five consecutive slices of the dynamic PET images. Spill-out from the AIF was corrected normalizing to the activity measured inside a 10-mm-diameter spherical VOI placed inside the left ventricle averaged over the latest frames. Delay was corrected by maximizing the cross-correlation between AIFBS (sum of AIFBS,F and AIFBS,Ga) and AIFID. In order to obtain dispersion-free AIFs, we assumed that at the moment of the second tracer injection (at time t2), the blood concentration of the first tracer was changing slowly and therefore did not suffer from dispersion. Thus, dispersion before t2 is corrected by using the AIFID as there is only contribution from the first tracer. After t2, we assume that AIFID,F and AIFBS,F are equal, and dispersion-free AIF for the second tracer can be obtained by direct subtraction of AIFID and AIFBS,F. Therefore, dispersion-free AIFF and AIFGa used for pharmacokinetic analysis can be derived as follows:

| 4 |

Kinetic modeling and image analysis

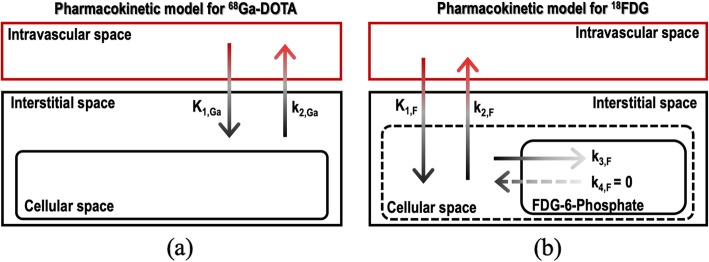

Parallel multi-tracer compartment modeling [3, 5, 16, 17] was applied to the recorded PET data where each tracer’s kinetic behavior is introduced according to its pharmacokinetic model and to its individual AIF. 68Ga-DOTA diffuses bidirectionally between the intravascular and the interstitial space suggesting the use of a single-tissue compartment model (1TCM) [10, 12] (see Fig. 5a). On the other hand, 18FDG is explained with an irreversible two-tissue compartment kinetic model (2TCM) (Fig. 5b). Therefore, the total tracer concentration measured in the tissue (Ctis) could be expressed as the sum contribution from both tracers:

Fig. 5.

Kinetic compartment models for 68Ga-DOTA (a) and 18FDG (b). The model for 68Ga-DOTA is a single-tissue compartment model as the radiotracer diffuses bidirectionally between the intravascular space and extravascular extracellular space (interstitial space). The model for 18FDG is an irreversible two-tissue compartment model as the radiotracer diffuses bidirectionally between the intravascular and cellular space, and once it enters the myocyte, it can phosphorylate to 18FDG-6-phosphate and remains trapped as it cannot be further metabolized

| 5 |

where IRFi({kj,i},t) is the impulse response function for tracer i, {kj,i} are the kinetic parameters, Cp,i(t) is the activity concentration in plasma for tracer i, and PVE(t) denotes the spill-over of radioactivity coming from LV and RV into myocardium. These IRFs can be described by the pharmacokinetic model that follows each tracer:

| 6a |

| 6b |

In order to obtain the free 68Ga-DOTA concentration in the plasma Cp,Ga(t), hematocrit (H), and free metabolite fraction (b) must be used. These values have been previously determined [14]. On the other hand, 18FDG concentration in the plasma for myocardial tissue has already been described [18]. Therefore, the relation between AIF(t) and Cp(t) for both tracers can be described as follows:

| 7a |

| 7b |

PVE contribution was not split for each tracer as it can be considered a function of the total blood activity concentration. It can be further decomposed in different components as follows:

| 8 |

where VLV, VRV, and VAP represent the spill-over fraction for the central LV, RV, and apical LV respectively [19], and CLV, CRV, and CAP represent the corresponding time-activity curves in those regions. The apical term was added to account for temporal differences observed between the central LV and the apical LV in swine hearts. The obtained kinetic parameters were not affected by the fact that decay correction was not applied to AIFs and Ctis functions as both are affected in the same way.

The model was applied on time-activity curves (TACs) obtained from PET images. For that purpose, the myocardium was segmented using available software [20] following the standard American Heart Association (AHA) 17-segment model [21], obtaining one TAC (Ctis in (5)) per segment. CLV and CAP were obtained from spherical VOIs drawn at the center (15 mm diameter) and apical (12 mm diameter) regions of the LV respectively, while VOI for determination of CRV was manually drawn inside RV over 3–5 slices leaving a margin (> 5 mm) from the myocardium. The 5-parameter model described on (5–8) was used to fit the data from each myocardial segment with a constrained Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm.

In vivo versus ex vivo myocardial tissue analysis

The concentration of both tracers at the end of the PET scan (Ctis,F(tend) and Ctis,Ga(tend)) was computed for each myocardial segment using (5). In addition, the corresponding relative activities (RF,PET and RGa,PET) as well as standardized uptake values (SUVF,PET and SUVGa,PET) were also derived in the same regions at the imaging endpoints, i.e., the values derived from the tracer distribution at the end of the PET scan. In order to validate these results, analogous measurements were obtained from myocardial tissue samples at the same regions of the same animals that had undergone the PET examinations.

For that purpose, each animal was sacrificed at the end of the PET scans, and the heart was excised and divided into 17 segments also following the AHA guidelines [21]. Each segment was further divided into 3 smaller portions to obtain triplicate measurements. These 51 samples were weighted and measured in the well counter. In order to increase the accuracy of myocardial samples analysis, the measurements in the well counter were performed several times for each sample for 15 h using the full energy window (W200–2000). Measurements were corrected for dead time and background. The counts recorded as a function of time were fitted to a sum of two exponentials in order to recover the contribution from each tracer as follows:

| 9 |

where λF and λGa are the radioactive decay constants for 18F and 68Ga respectively, and WF and WGa are the counts measured in the well counter from each isotope. WF(t0) and WGa(t0) were fitted using (9) and converted to activity using the corresponding calibration factors (see Fig. 4). Activity values were decay corrected at sacrifice time (end of PET scan), and the ex vivo relative activities for 18FDG (RF,ex vivo) and 68Ga-DOTA (RGa,ex vivo) were obtained. The results obtained on each myocardial segment were averaged over triplicate samples. SUV values were also derived and extrapolated to the imaging endpoints for each tracer (SUVF,exvivo and SUVGa,ex vivo).

The 18FDG relative activities derived from tissue samples (RF,ex vivo) and from multi-tracer PET imaging (RF,PET) were compared using Pearson’s correlation and the root mean square error (RMSE), which is defined as follows:

| 10 |

where s is the myocardial segment, and N is the number of myocardial segments analyzed (N = 17). In addition, SUV values derived from multi-tracer PET imaging were compared with values obtained from excised myocardial segments. For any statistical analysis, data are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated.

Results

Tracer separation by gamma spectroscopy

The results of the calibration procedure performed to separate the contribution of 18F- and 68Ga-based tracers from blood samples containing a mixture of both tracers are presented here. Figure 2 shows a linear behavior (r2 > 0.999) between the relative activity for 68Ga (RGa) of different 68Ga-18F mixture samples and the QS value measured in the well counter. Figure 3 shows these QS values for pure 18F and 68Ga samples with volumes ranging from 50 to 2000 μl. Of note, the well counter detection efficiency for the high-energy gamma photon emitted by 68Ga is relatively higher at low sample volumes probably due to geometric factors. When the sample volume is small, high energy events represent about 4% of the total counts for 18F samples while it raises up to 10% for 68Ga samples. QS(VS) profiles for 18F and 68Ga were fitted to a straight line and a sum of two exponentials respectively in order to interpolate to any given sample volume. Figure 4a shows the calibrations performed to translate the measurements obtained in the well counter using the full energy window to activity (data shown for 18F and 68Ga). Data presented in Fig. 4a were obtained from 300-μl samples. However, the calibration factors are also volume dependent. Therefore, the calibration was repeated for different sample volumes to account for this effect (see Fig. 4b).

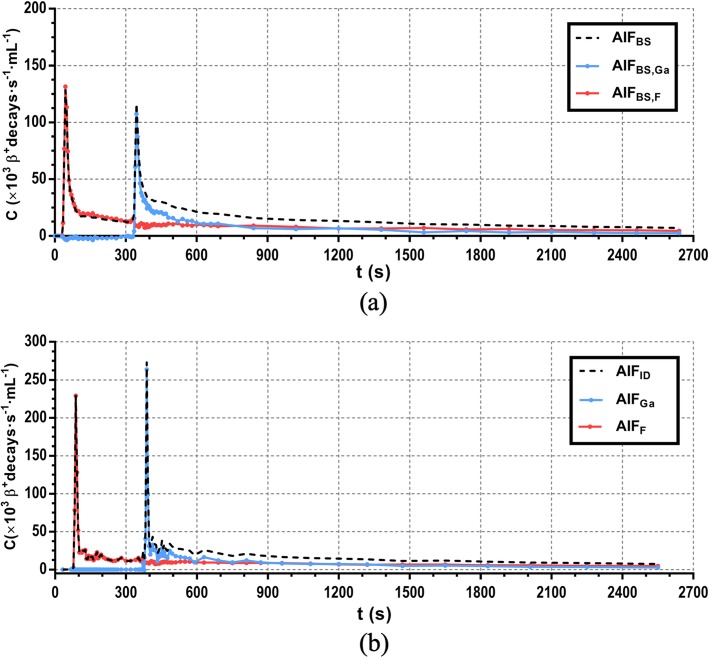

In vivo validation of multi-tracer PET against tissue analysis

Figure 6a shows an illustrative AIFBS,F and AIFBS,Ga obtained from collected blood samples that were analyzed using the gamma spectroscopy methodology previously described. The corresponding AIFID is shown in Fig. 6b as well as the dispersion-free AIFs for each tracer (AIFF and AIFGa) which were obtained using the methodology explained in its corresponding methods section.

Fig. 6.

a AIFBS,F (red) and AIFBS,Ga (blue) obtained from manual blood sampling during PET scan applying the spectroscopic method. The black dashed line shows the sum of both tracers. b AIFID (black dashed line) obtained from the dynamic PET images using an ROI drawn in the descending thoracic aorta and delay corrected and dispersion-free contributions from 18FDG (red) and 68Ga-DOTA (blue) obtained as detailed in (4)

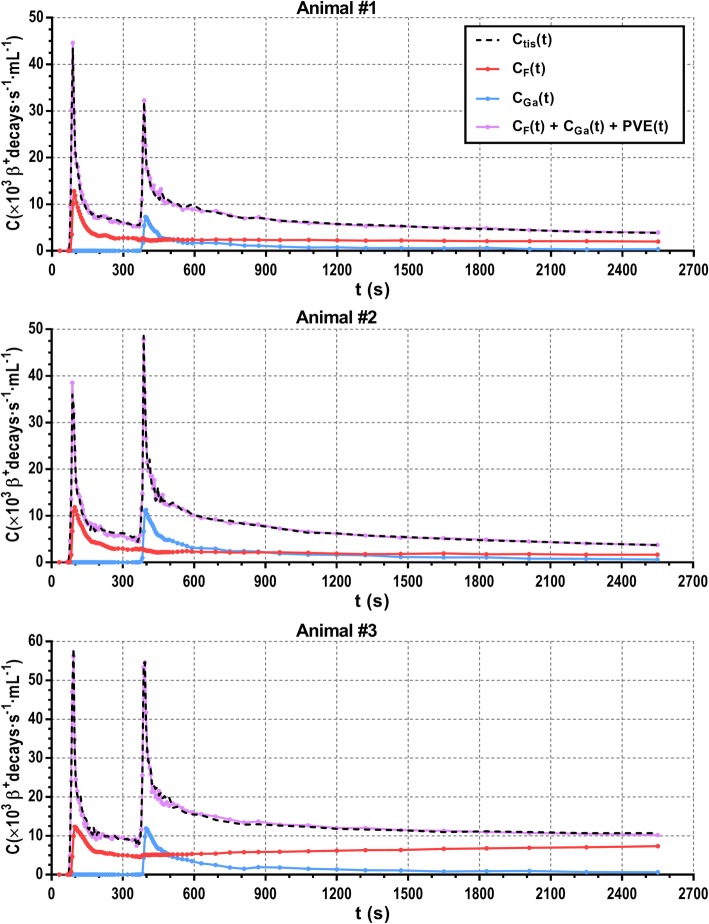

Figure 7 illustrates myocardial tissue TACs (Ctis) obtained from dynamic PET data for each of the animals included in this study. These TACs were fitted using the multi-tracer compartment model shown in (5). The separate contribution obtained for 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA is presented in Fig. 7 along with the total tissue signal including the spill-over.

Fig. 7.

Myocardial tissue TACs obtained from dynamic PET images for each animal included in this study (black dashed lines). Data was fitted to the multi-tracer compartment model shown in (5) (purple line) and separated into tissue TACs for 18FDG (red) and 68Ga-DOTA (blue)

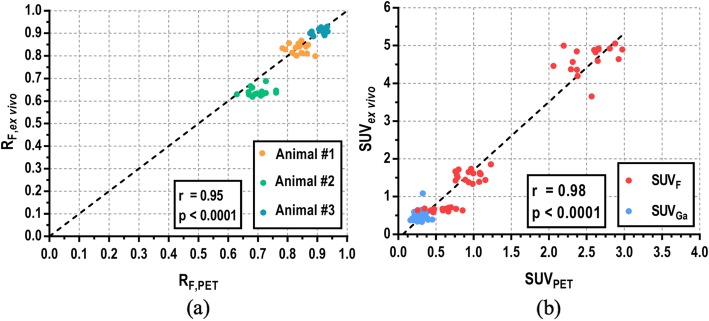

Figure 8a shows the comparison of the relative activity for 18FDG obtained from multi-tracer compartment modeling at imaging endpoints (RF,PET) and from excised tissue (RF,ex vivo) for each animal and myocardial segment. An excellent correlation was obtained (Pearson’s r = 0.95, p < 0.0001). Mean ± SD RF,PET (RF,ex vivo) obtained were 0.84 ± 0.03 (0.83 ± 0.02), 0.70 ± 0.03 (0.64 ± 0.02), and 0.91 ± 0.02 (0.91 ± 0.01) for animals 1, 2, and 3 respectively. These averaged results, as well as RMSE and individualized SUVs for 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA contributions, are presented in Table 1. SUV values obtained for 68Ga-DOTA were similar in all animals. SUVGa is low (~ 0.3) because this tracer reaches equilibrium between the plasma and the interstitial space, and therefore, the tracer does not accumulate in the tissue. On the other hand, low SUVF,PET were obtained for animals 1 (0.97) and 2 (0.62) while higher values were obtained in the third animal (2.54). These SUV values are highly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.98, p < 0.0001) with those obtained from excised tissue (SUVF,ex vivo and SUVGa,ex vivo). The lower RMSE value calculated for the third animal is consistent with the higher SUVF obtained since higher uptake leads to lower statistical noise in the pharmacokinetic analysis, as well as in the measurements performed on excised tissue. In all cases, RMSE values were below 7%.

Fig. 8.

Linear correlation between relative activities for 18FDG (a) and between SUVs for both 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA (b) obtained from multi-tracer compartment modeling at imaging endpoints (RF,PET, SUVPET) and from excised tissue (RF,ex vivo, SUVex vivo). Each dot represents one of the 17 myocardial segments for each animal. The results are highly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.95, p < 0.0001 for relative activities and r = 0.98, p < 0.0001 for SUVs)

Table 1.

RF,PET and RF,ex vivo values are represented as the mean ± SD of all the myocardial segments analyzed for each animal along with their comparison obtained using the RMSE value. Mean ± SD SUV for each tracer obtained from multi-tracer PET analysis and excised tissue are also shown

| Animal | RF,PET | RF,ex vivo | RMSE (%) | SUVGa,PET | SUVGa,ex vivo | SUVF,PET | SUVF,ex vivo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 3.6 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 0.96 ± 0.15 | 1.56 ± 0.14 |

| 2 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 6.8 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.65 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 1.7 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 2.55 ± 0.26 | 4.65 ± 0.36 |

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we proposed a novel technique to perform multi-tracer PET imaging using multi-tracer compartment modeling with explicit separation of individual AIF for each tracer. This technique relies on the use of two tracers with different isotopes with at least one of them being a non-pure positron emitter. If the energy of the additional gamma photons emitted by the non-pure positron emitter differs from the energy of annihilation photons, a spectroscopic analysis of blood samples containing both tracers can be performed in order to obtain the concentration of each individual tracer.

First, we developed a calibration procedure that allows the determination of individual tracer concentration of samples containing an unknown mixture of the isotopes used in this study (18F and 68Ga). For that purpose, samples were analyzed in a well counter recording event at two energy windows. The ratio between the counts recorded in both energy windows was later employed to determine the relative activity of each isotope. Corrections were made to account for different sample volumes (see Fig. 3).

The proposed technique was implemented in vivo by performing cardiac PET/CT studies on three healthy pigs, which were injected with 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA during the same acquisition and validated against their analogous ex vivo measurements. A 45-min dynamic PET scan was performed on each animal, and blood samples were collected during the entire acquisition and further analyzed with the well counter to determine the AIF for each tracer. A multi-tracer compartment model was later applied to recover the individual tissue TAC for each tracer on individual myocardial segments (see Fig. 7). Imaging endpoint concentrations were validated against both 18FDG and 68Ga-DOTA concentration measured with the well counter on excised myocardial tissue. Results show that the proposed multi-tracer PET imaging technique offers very similar results to those obtained as a reference from ex vivo analysis (see Fig. 8), with RMSE below 7% in all cases. Moreover, SUV for 68Ga-DOTA and 18FDG was obtained showing normal 68Ga-DOTA uptake for healthy pigs [12] and variable 18FDG uptake as expected, since no prior glucose load was used [22]. An overestimation of SUVex vivo values compared with SUVPET values can be observed, which might be explained by partial volume effect in PET data.

The proposed technique allows performing PET scans with two tracers during the same acquisition obtaining separate information from each tracer. This new method allows explicit measurement of separate AIF for each tracer while other existing methods rely on AIFs based on representative patients [23] or using extrapolation techniques [24]. However, our technique requires using at least one tracer based on a non-pure positron emitter, preventing the combination of tracers based on the same isotope. On the other hand, 68Ga is a suitable isotope for this technique. 68Ga has emerged as a very promising isotope for PET imaging with many relevant applications in clinical diagnosis [8]. Therefore, further combinations of tracers based on 18F and 68Ga, different from that shown in this study, might benefit from this work. Another limitation of our method is that it is invasive as it requires the collection of blood samples while other methods are non-invasive. Separation of AIFs could be generally applied using chromatographic techniques [25] although this is a very time-consuming process, and only a few blood samples could be analyzed.

Other techniques for multi-tracer PET imaging which use non-pure positron emitters with prompt gamma emissions record coincidence events with the PET scanner containing annihilation and prompt gamma photons, which are later used in the reconstruction process to separate the contribution from each tracer [6]. However, a higher branching ratio of the prompt gamma photons is required to obtain enough sensitivity of this type of events, and therefore, those techniques are limited to less common isotopes like 124I. It should be noted that in the proposed method, the additional gamma photons emitted by the non-pure positron emitter can be delayed with respect to the positron decay as they do not have to be detected in coincidence for the spectroscopic analysis.

In this study, the spectroscopic analysis of the blood samples was performed using a well counter. However, an online blood sampling detector [26, 27] could be also used, which would further simplify the implementation of this technique. We recently developed a novel blood sampling detector and successfully tested it in vitro for multi-tracer measurements based on the spectroscopic analysis [28]. In that case, the blood would be extracted from the patient through a catheter that would pass through a gamma photon detector, and a similar methodology to the one applied with the gamma counter would be used. In that way, AIF separation could be obtained immediately while minimizing the radiation exposure of the personnel and avoiding technical issues such as volume dependence of blood samples.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Rubén A. Mota Blanco (Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC)) and Charles River Laboratories España for helping with animal management and care during in vivo experiments.

Abbreviations

- AIF

Arterial input function

- FDG

Fludeoxyglucose

- IRF

Impulse response function

- MBF

Myocardial blood flow

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PVE

Partial volume effect

- RMSE

Root mean square error

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- TAC

Time-activity curve

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and acquisitions. CV and SE contributed to the data analysis and processing. CV and SE contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the manuscript discussion, correction, and final approval.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Carlos III Institute of Health of Spain and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, “Una manera de hacer Europa”) (FIS-FEDER PI14-01427) and from the Comunidad de Madrid (2016-T1/TIC-1099). CV holds a fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education (FPU014/01794). The CNIC is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MCNU), and the Pro CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (SEV-2015-0505).

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available on request to the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the current European Directive and Spanish legislation and approved by the regional ethical committee for animal experimentation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yang Y, He MZ, Li T, et al. MRI combined with PET-CT of different tracers to improve the accuracy of glioma diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2019;42(2):185–195. doi: 10.1007/s10143-017-0906-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh N, Rimoldi OE, Beanlands RSB, et al. Assessment of myocardial ischaemia and viability: role of positron emission tomography. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(24):2984–2995. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikoma Y, Toyama H, Suhara T. Simultaneous quantification of two brain functions with dual tracer injection in PET dynamic study. Int Congr Ser. 2004;1265:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ics.2004.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhaeghe J, Reader AJ. Simultaneous water activation and glucose metabolic rate imaging with PET, Phys. La Medicina Biologica. 2013;58(3):393–411. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/3/393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadrmas DJ, Rust TC. Feasibility of rapid multi-tracer PET tumor imaging. In: IEEE Symposium Conference Record Nuclear Science. 2004;4:2664–2668. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreyev A, Celler A. Dual-isotope PET using positron-gamma emitters, Phys. La Medicina Biologica. 2011;56(14):4539–4556. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/14/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti M, Eriksson L. Physics of pure and non-pure positron emitters for PET : a review and a discussion. EJNMMI Phys. 2016;3:8. doi: 10.1186/s40658-016-0144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shetty D, Lee YS, Jeong JM. 68Ga-labeled radiopharmaceuticals for positron emission tomography, Nucl. Med Mol Imaging. 2010;44(4):233–240. doi: 10.1007/s13139-010-0056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bengel FM, Higuchi T, Javadi MS, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography, J. Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Autio A, Saraste A, Kudomi N, et al. Assessment of blood flow with (68)Ga-DOTA PET in experimental inflammation: a validation study using (15)O-water, Am. J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;4(6):571–579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H, Lee SJ, Davies-Venn C, et al. 64Cu-DOTA as a surrogate positron analog of Gd-DOTA for cardiac fibrosis detection with PET: pharmacokinetic study in a rat model of chronic MI, Nucl. Media Commun. 2016;37(2):188–196. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velasco C, Mota-Cobian A, Mota RA, et al. Quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow and extracellular volume fraction using 68Ga-DOTA-PET: a feasibility and validation study in large animals. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Autio A., Uotila S., Kiugel M. et al.,68Ga-DOTA chelate, a novel imaging agent for assessment of myocardial perfusion and infarction detection in a rodent model, J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2019. 10.1007/s12350-019-01752-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Velasco C, Mateo J, Santos A, et al. Assessment of regional pulmonary blood flow using 68Ga-DOTA PET. EJNMMI Res. 2017;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13550-017-0259-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosentrater KA, Flores RA. Physical and rheological properties of slaughterhouse swine blood and blood components. Trans ASAE. 1997;40(3):683–689. doi: 10.13031/2013.21287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koeppe RA, Raffel DM, Snyder SE, et al. Dual-[11C]tracer single-acquisition positron emission tomography studies, J. Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21(12):1480–1492. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kardmas D, Di Bella E, Black N, et al., Rapid multi-tracer PET imaging systems and methods, Patent US7848557B2, Dec. 7, 2010.

- 18.Phelps ME, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, et al. Tomographic measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolic rate in humans with (F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: validation of method. Ann Neurol. 1979;6(5):371–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nesterov SV, Han C, Mäki M, et al. Myocardial perfusion quantitation with15O-labelled water PET: high reproducibility of the new cardiac analysis software (CarimasTM) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(10):1594–1602. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association, Circ. J Am Heart Assoc. 2002;105(4):539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machac J, Bacharach SL, Bateman TM, et al. Positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion and glucose metabolism imaging, J. Nucl Cardiol. 2006;13(6):e121–e151. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadrmas DJ, Rust TC, Hoffman JM. Single-scan dual-tracer FLT+FDG PET tumor characterization. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58(3):429–449. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/3/429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rust TC, DiBella EVR, McGann CJ, et al. Rapid dual-injection single-scan 13 N-ammonia PET for quantification of rest and stress myocardial blood flows. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(20):5347–5362. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/20/018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng X, Li Z, Liu Z, Navab N, et al. Direct parametric image reconstruction in reduced parameter space for rapid multi-tracer PET imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34(7):1498–1512. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2403300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breuer J, Grazioso R, Zhang N, et al. Evaluation of an MR-compatible blood sampler for PET. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(19):5883. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/19/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roehrbacher F, Bankstahl JP, Bankstahl M, et al. Development and performance test of an online blood sampling system for determination of the arterial input function in rats. EJNMMI Physics. 2015;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40658-014-0106-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Velasco C, Mota-Cobián A, Mateo J, España S. Development of a blood sample detector for multi-tracer positron emission tomography using gamma spectroscopy. EJNMMI Physics. 2019;6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40658-019-0263-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordström J, Kero T, Harms HJ, et al. Calculation of left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction from dynamic cardiac-gated 15O-water PET/CT: 5D-PET. EJNMMI Phys. 2017;4(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s40658-017-0195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available on request to the authors.