Abstract

An efficient in vitro regeneration system using epicotyl segments was developed and then used for optimizing genetic transformation of the Tunisian 'Maltese half-blood' (Citrus sinensis) variety using phosphinothricin (PPT) resistance as a selectable marker. The maximum regeneration efficiency was achieved after incubating epicotyl explants (excised in an oblique manner) in MT culture media containing BAP (4 mg/l) and IAA (0.3 mg/l) hormonal combination in the dark for 3 weeks before their transfer to light. Data from the genetic transformation assays indicated that the highest number of regenerated-transformants was reached when the selection phase was conducted in MT culture media containing PPT (0.25 mg/l) and Carbenicillin (500 mg/l) for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 8 weeks of light. After that, transformed buds were maintained for eight additional weeks in the same culture media but with reduced PPT concentration (0.125 mg/l) before decreasing Carbenicillin dose (250 mg/l) at the second half of this last incubation period which allowed both a good shoot proliferation and an optimal rooting efficiency. Based on molecular analyses, the transgenicity of 21.42% of the regenerated vitroplants was confirmed. The developed regeneration and transformation procedures of the elite ‘Maltese half-blood’ variety can be used for orchard renewal as well as for functional studies and genome editing purposes to develop new cultivars with the desired genetic traits.

Keywords: Citrus sinensis, Maltese half-blood, Organogenesis, Genetic transformation

Introduction

Citrus species are among the most important fruit crops worldwide. Citrus fruits are mainly produced in coastal areas of numerous countries as well as in the Mediterranean region. Citrus fruits are known for their fine flavor, nutritional quality and medicinal value (Ani and Abel 2018).

In Tunisia, citrus occupies the second rank after olive in terms of agro-economic importance (Lakhoua 1997) and extends over 24,000 ha (Zouaghi et al. 2019). In fact, this culture gave rise to a production average of 346,000 tons in 2018. Its cultivation area was increased from 13,500 ha in 1990 to 27,000 ha in 2018 by creating novel plantation zones, reaching approximately 5% of the total fruit plantations (Gifruit 2018).

‘Maltese half blood’ variety which belongs to Citrus sinensis, renowned for being “The Queen of Oranges”, is considered as the best sweet orange in the world for its excellent sugar-acid balance and exceptional aromatic palette (Dhifi and Mnif 2012). This variety is tightly related to Tunisia, the only producer and exporter in the world. It is cultivated on the land of the peninsula of Cape Bon and in some hot areas in the north and center of the country.

In the Cap Bon region, Maltese is grown on an area of 11,000 ha, accounting for 72.3% of the total citrus orchard area, and giving rise to 85% of the total citrus production. The remaining 15% of the citrus production is shared by the regions of Jendouba, Bizerte, Beja, Ben Arous, Ariana and Manouba (Farhat et al. 2016).

Besides its importance in the Tunisian agro-economy, Maltese by-products were reported to be a good source of oleic acid that is known for its health virtues and protective effect against cardiovascular diseases highlighting a potential medicinal use for this variety (Dhifi and Mnif 2012).

In Tunisia, Citrus exportation accounts for 6% of the total production of the country and the Maltese production accounts by itself for 84% of the total citrus exportation towards several countries including France which ranked first in selling the Maltese (82%), followed by Algeria (13%), Libya (4%), and other European and Middle East nations (Gifruit 2018). However, during the last decade, this Maltese production registered a reduction of exports (from 31,005 tons in 1997 to 20,530 tons in 2013) due to the aging of Maltese orange orchards (30%) and global warming (Zekri and Laajimi 2001; Metoui et al. 2014). In this respect, the creation of new orchards with juvenile plants is of prime interest towards revitalization, conservation and evolution of the Maltese market in Tunisia (Farhat et al. 2016). To achieve this goal, an efficient in vitro regeneration system for this variety is needed. Specifically on, no records on the response and competence of ‘Maltese half-blood’ explants to in vitro culture via organogenesis. On the other hand, the optimization of an in vitro regeneration system is mandatory for optimizing genetic transformation for future functional genomic studies to allow the introduction of desired traits into this variety. Nowadays, climate change is a major global concern which leads to the concurrence of a number of abiotic and biotic stresses, thereby affecting agricultural productivity (Pandey et al. 2017) and making agriculture even more risk-prone mainly in the developing world (Tuteja and Gill 2012). Genetic engineering strategies aiming to improve biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and to enhance fruit quality in horticultural crops were established (Parmar et al. 2017). In this context, different methods for plant improvement have been developed for various citrus species (Gong and Liu 2013) using either polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated direct uptake of DNA by protoplast (Olivares-Fuster et al. 2003), particle bombardment (Wu et al. 2016) or Agrobacterium-mediated transformations (Febres et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2017). Agrobacterium is the most frequently used genetic transformation method in citrus using explants collected from seedlings germinated in vitro or under greenhouse conditions as it has been proven most successful in terms of both transformation efficiency and transgenic-plant production rates (Almeida et al. 2003; Donmez et al. 2013). In fact, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of numerous hybrids and species of citrus such as grapefruit, sour orange, sweet orange, trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata Raf.) has been reported (Ghaderi et al. 2018; Dominguez et al. 2004; Molinari et al. 2004; Pena et al. 2004). In this context, almost of genetic transformation experiments were conducted with the aim to produce citrus plants with improved tolerance to diseases (Febres et al. 2008), salinity stress (Cervera et al. 2000) and drought (Alvarez-Gerding et al. 2015).

As known, genetic transformation of other economically important citrus cultivars with the existing protocols has not yet been successful due to species or cultivar specificity (Donmez et al. 2013). Therefore, effective genetic manipulations in citrus require specific studies for each genotype.

The present study aims to standardize an efficient method for multiple shoot induction and regeneration from seedling epicotyl segments of the Tunisian ‘Maltese half-blood’ and the use of the developed regeneration system for optimizing an Agrobacterium-mediated transformation protocol using GUS and PPT as reporter and selective marker genes, respectively.

Material and methods

Plant material and culture conditions

Tunisian ‘Maltese half-blood’ fruits were harvested from orchards. In vitro germinated seedlings were used as starting tissues. Seeds were removed from fresh fruits and disinfected by dipping in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s followed by 0.5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min. The seeds were then rinsed three times with sterile distilled water.

All assessed cultures were incubated in a culture room with 25 ± 2 °C either in darkness, or in 16 h photoperiod and 70 µmol/m2/s light intensity was provided by cool white fluorescent tubes.

Effect of dark incubation period on seed germination

Seed culture was carried out in test tubes (25 × 150 mm) containing 15 ml of MT solid medium (Murashige and Tucker 1969) supplemented with 15 g/l of sucrose. Seeds were incubated in the dark at 25 ± 2 °C temperature for 2, 3 or 4 weeks. After that, seed germination percentages were recorded for each treatment. When the seedlings reached 5 cm of height, they were transferred to 16/8 h photoperiod. Twenty-eight days later, seedling epicotyls were cut in segments of 0.8–1 cm length and used as explants.

Effect of hormone on bud formation

Epicotyl segments were horizontally placed in Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) containing MT salts and vitamins medium supplemented with Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP). In vitro organogenesis was also assessed under four different hormonal combinations. In fact, IAA was applied at 0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 mg/l concentrations and BAP at 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4.0 mg/l concentrations. The number of formed buds was then scored on the explants. Each replication consisted of a Petri dish with 16 explants.

Effect of cut mode on bud formation

To determine the effect of cut mode on bud formation efficiency, the appropriate hormonal combination was used for culture and epicotyl segments were placed horizontally on the medium with the longitudinal, transversal and oblique cut surface facing upwards.

Effect of dark/light conditions on bud formation

Three dark/light conditions consisting of 2, 3 and 4 weeks of darkness followed by 4 weeks of light were tested on both bud and shoot formation efficiency. The number of developed buds and shoots was counted as mentioned above and the regeneration efficiency was determined after 6 weeks of incubation in the light.

Rooting

The regenerated shoots (> 1 cm in length) were excised from the explants and placed (from the basal portion) into 1/2 MS medium supplemented with 3-Indole butyric acid (IBA). Three concentrations of IBA (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/l) were tested in root induction assays. Both rooting frequency and mean root length parameters were recorded based on 20 transferred shoots within 6 weeks’ post-treatment.

Acclimatization

Regenerated plantlets were removed from their tubes and washed gently with water before their transfer to pots containing common soil. Thereafter, pots were placed in plastic small greenhouse during the first week to retain moisture before their transfer to greenhouse with controlled conditions (a light intensity of 25 W/m2, a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod, an average temperature of 25/18 °C day/night and a relative humidity of 60–70%). Survival rate was evaluated after 30 days.

PPT sensitivity of epicotyls segments

To determine the appropriate concentration of the selective agent phosphinothricin DL-PPT (C5H15N2O4P Duchefa) that is able to suppress the growth of non-transgenic cells, epicotyl segments were cultured on MT medium containing the optimal hormone combination and different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/l) of the selective PPT agent. Culture was carried out according to the optimized regeneration system.

Transformation and regeneration

The binary vector pPZP200-bar-gus-intron (Jardak-Jamoussi et al. 2008) harboring GUS and Bar as reporter and selective genes, respectively, was introduced into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 (Hoekema et al. 1983). GUS encodes for β-glucuronidase expression. The Bialaphos Bar gene confers resistance for the phosphinothricin acetyl transferase (PAT) protein (D’Halluin et al. 1992).

Epicotyl segments (excised with the oblique cut mode) were inoculated with LBA4404 A. tumefaciens strain (5 × 108 cfu/ml) harboring the pPZP200-bar-gus-intron before their incubation in liquid MT medium containing 200 µM acetosyringone for 20 min.

The explants were then washed three times in MT medium containing 500 mg/l Carbenicillin. After that, they were dried on sterile paper and placed on co-cultivation MT medium containing 200 µM acetosyringone and 2.5 g/l PVPP (polyvinylpolypirrolidone) for 48 h. Selection in MT medium containing 2.5 g/l PVPP and the appropriate hormonal combination was carried out based on two distinct procedures: (1) The use of 0.25 mg/l PPT and 500 mg/l Carbenicillin for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 12 weeks of light; (2) the use of 0.25 mg/l PPT and 500 mg/l Carbenicillin for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 8 weeks of light before reducing PPT concentration to 0.125 mg/l but with either maintaining Carbenicillin concentration at 500 mg/l or its reduction to 250 mg/l during the last 4 weeks of the culture.

Regeneration of vitroplants was performed according to the optimized conditions at a temperature of 24–25 °C and a 16/8 h photoperiod with a light intensity of 70 mol/m2/s. Acclimatization was achieved under controlled greenhouse conditions (24 °C temperature, 60% relative humidity and 16/8 h photoperiod).

Gus assay and molecular analyses

Histochemical GUS assay was used to assess transformation efficiency according to Jefferson et al. (1987). This was achieved by recording GUS spot expression in both buds and shoots of the regenerated plantlets. Thus, buds showing GUS expression were assessed in three independent replicates (three Petri dishes) and three explants from each Petri dish were examined per replicate.

PCR and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) were carried out for the analysis of the regenerated transformed plants using the following primers 5′-TCT GCA CCA TCG TCA ACC ACT ACA-3′and 5′- GCA GCC CGA TGA CAG CGA CCA C-3′; to detect the Bar gene. DNA and RNA were extracted from control and putative transgenic plants using Zymo kits (Quick-DNA Plant/Seed Kits; Quick-RNA Plant Kit). Thirty-five cycles of PCR were performed in programmed temperature control system (Genius) with an initial melting step for 2 min at 94 °C. A single cycle consist of the following steps: denaturation for 1 min at 94 °C, annealing of primers for 40 s at the corresponding Tm (62.4 °C), elongation for 1 min at 72C °C and final extension for 5 min at 72 °C (Jardak-Jamoussi et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design (RCBD). The results are means ± standards errors of three replicates. The least significant differences (LSD; p < 0.05) were calculated using STATISTICA Software. Student’s t test (p < 0.05) was used to check for significant differences among parameters related to the PPT assay.

Results

Effect of dark incubation on seed germination

To obtain sufficient amount of epicotyls required for the in vitro regeneration experiments, we assessed the effect of dark treatment duration on seed germination efficiency. Our data revealed that, among the different time intervals tested, the time duration of 4 weeks of dark treatment provided the highest seed germination efficiency (33.67 ± 3.06%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of dark incubation duration on seed germination

| Dark incubation duration (weeks) | Germination % |

|---|---|

| 2 | 15 ± 2.65b |

| 3 | 21 ± 1.73b |

| 4 | 33.67 ± 3.06a |

Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The least significant differences (LSD) were calculated. The letters indicate significant differences according to LSD test (p < 0.05)

Effect of hormone concentrations of the combined BAP and IAA

The effect of different BAP:IAA ratios was tested on bud formation from ‘Maltese half-blood’ epicotyl segments. The data (Table 2) indicated that the number of buds per explant increased upon raising BAP and IAA concentrations. In fact, the highest average number of buds per explant (25.33 ± 1.45) was reached when a BAP:IAA ratio of 4:0.3 was applied. All other ratios beside the control treatment induced a significantly lower bud formation.

Table 2.

The effect of different BAP and IAA concentrations on the number of developed buds per explant

| Number of buds/explant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAA (mg/l) | ||||

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| BAP (mg/l) | ||||

| 0 | 0.33 ± 0.33j | 0.66 ± 0.33j | 4.6 ± 0.88efg | 1.6 ± 0.33hij |

| 1 | 1 ± 0.58ij | 2.33 ± 0.33hij | 3 ± 0.58ghi | 6 ± 1de |

| 2 | 3.33 ± 0.66gh | 3.66 ± 0.33fgh | 5.6 ± 0.33def | 9 ± 0.58c |

| 3 | 1.66 ± 0.33hij | 4.66 ± 0.88efg | 6.66 ± 0.88de | 13 ± 0.58b |

| 4 | 3.33 ± 0.33gh | 7 ± 1.15 cd | 15 ± 1.53b | 25.33 ± 1.45a |

Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The least significant differences (LSD) were calculated. The letters indicate significant differences according to LSD test (p < 0.05)

Effect of the cut mode on bud and shoot formation

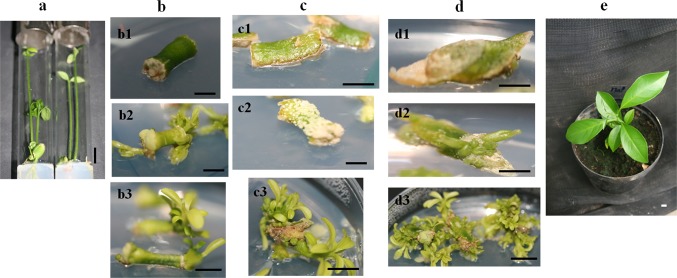

Three different cut modes were tested for their impact on bud and shoot formation rates from ‘Maltese half-blood’ epicotyl segments (Fig. 1a) under 2 weeks dark followed by 4 weeks light with a BAP:IAA ratio of 4:0.3 (Table 3). Our data revealed that the oblique cut mode provided the highest number of buds (37.33 ± 1.45) and shoots (23 ± 2.64) per explant (Fig. 1d) followed by the transversal one (27.67 ± 1.45 buds/explant and 10 ± 1.15 shoots/explants) (Fig. 1c), while, the longitudinal cut mode allowed relatively lower bud and shoot numbers (7.67 ± 1.45 and 4.67 ± 0.88, respectively) (Fig. 1b). Epicotyl segments that were excised with the longitudinal cut mode showed a rapid shoot formation compared to the remaining ones (Fig. 1-b2). Epicotyl segments obtained via the transversal cut mode did not proliferate efficiently when transferred to light (Fig. 1-c2). Both bud formation and shoot development were observed following 2 weeks of culture in the dark before their transfer to light for four additional weeks (Fig. 1-d2).

Fig. 1.

Assessment of the effect of three different cut modes of epicotyl segments excised from the epicotyl of the ‘half-blood Maltese’ variety (a). Bud and shoot formation when the transversal (b), longitudinal (c) and oblique (d) cut modes were applied. b1, c1, and d1: Epicotyl segments after 1-week incubation in the dark. b2, c2, d2: Bud formation after 2 weeks of incubation in the dark before their transfer to light for 4 weeks. b3, c3, d3: Shoot formation and elongation under light conditions. e A regenerated ‘half-blood Maltese’ plant after acclimatization under greenhouse conditions. Bars correspond to 5 mm

Table 3.

Effect of cut mode on bud and shoot formation

| Bud number/explant | Shoot number/explant | |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | 7.67 ± 1.45c | 4.67 ± 0.88b |

| Transversal | 27.67 ± 1.45b | 10 ± 1.15b |

| Oblique | 37.33 ± 1.45a | 23 ± 2.64a |

Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The least significant differences (LSD) were calculated. The letters indicate significant differences according to LSD test (p < 0.05). Mean values of bud number/explant were compared independent of the mean values of shoot number/explant

Compared to the epicotyl explants excised with the longitudinal (Fig. 1-b3) and transversal (Fig. 1-c3) cut modes, those excised with the oblique one (Fig. 1-d3) provided 4.93- and 2.3-fold of shoots, respectively (Table 3).

Effect of the dark treatment duration on bud and shoot regeneration

To assess the effect of the time duration of the dark treatment on the efficiency of bud formation, epicotyl segments were placed in MT medium (with a BAP:IAA ratio of 4:0.3) for 2, 3 or 4 weeks in the dark before their transfer to light conditions for 4 weeks and, thereafter, the number of buds and shoots was recorded (Table 4). Our results showed that a dark treatment duration of 3 weeks allowed the highest number of buds (44.66 ± 3.18%) and shoots (33 ± 2.65%) per explant compared to those subjected to dark treatment intervals of two (37.33 ± 2.51 and 23 ± 2.66 for buds and shoots, respectively) and 4 weeks (31.33 ± 1.86 and 14.66 ± 2.85 for buds and shoots, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of dark incubation duration on bud and shoot formation per explant

| Dark incubation duration | Buds number/ explant | Shoot number/explant |

|---|---|---|

| 2 W D/4 W L | 37.33 ± 2.51ab | 23 ± 2.66b |

| 3 W D/4 W L | 44.66 ± 3.18a | 33 ± 2.65a |

| 4 W D/4 W L | 31.33 ± 1.86b | 14.66 ± 2.85b |

Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The letters indicate significant differences according to LSD test (p < 0.05). Mean values of bud number/explant were compared independent of the mean values of shoot number/explant

Rooting efficiency

The effect of different IBA concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/l) added to 1/2 MS culture media on both rooting efficiency and root length parameters of the regenerated shoots (that were developed on MT medium added with 4 mg/l BAP and 0.3 mg/l IAA) was assessed (Table 5). The use of 0.5 mg/l IBA concentration provided the lowest rooting efficiency (34.33 ± 2.72%) as well as the lowest mean root length (3.4 ± 0.23 cm/plantlet). However, a concentration of 1 mg/l of IBA provided the highest rooting efficiency (69.33 ± 2.96%) and the highest mean root length (5.73 ± 0.34 cm/plantlet). The increase in IBA concentration (2 mg/l) negatively affected both rooting efficiency and mean root length parameters (45.33 ± 1.76 and 4.1 ± 0.79, respectively).

Table 5.

Effect of IBA concentrations on rooting efficiency of the regenerated shoots in 1/2 MS medium

| IBA (mg/l) | Rooting efficiency (%) | Root length (cm/plantlet) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 34.33 ± 2.72c | 3.4 ± 0.23c |

| 1 | 69.33 ± 2.96a | 5.73 ± 0.34a |

| 2 | 45.33 ± 176b | 4.1 ± 0.79ab |

Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The letters indicate significant differences according to LSD test (p < 0.05). Percentages of rooting efficiency were compared independent of the mean values of root length per plantlet

Effect of different PPT concentrations on epicotyl segments

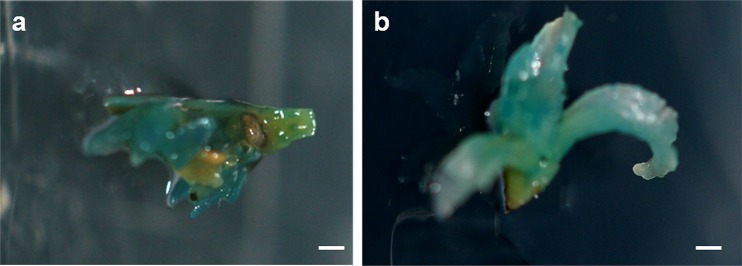

To determine the appropriate concentration of PPT to be used in the selection phase, the response of intact epicotyl segments to various PPT concentrations ranging from 0 to 2 mg/l was assessed (Table 6). Our data (Fig. 2) showed that bud formation occurred only in control explants (0 mg/l of PPT) (Fig. 2a). In addition, the explants cultivated in the presence of PPT (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/l) exhibited only whitening on their surfaces (Fig. 2c, d, e). However, a concentration of 0.25 mg/l led to a slight necrosis accompanied by a swelling of tissues beside the generation of callus as initiation of budding was observed in the cut zone after incubation for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 2 weeks in light conditions (Fig. 2b). Nevertheless, in the following weeks, we observed significantly smaller bud number on almost all explants subjected to 0.25 mg/l PPT compared to control conditions (Table 6). Since the growth of these buds was arrested, we opted for a PPT concentration of 0.25 mg/l to select the transformed cells.

Table 6.

Effect of different PPT concentrations on epicotyl segments

| PPT (mg/l) | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bud number/explant | 25.67a | 6.67b | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data were recorded after incubation for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 2 weeks in light conditions. Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. Values followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to student’s t test

Fig. 2.

Epicotyl segments exposed to PPT at different concentrations; a 0 mg/l PPT; b 0.25 mg/l PPT; c 0.5 mg/l PPT, d 1 mg/l PPT and e 2 mg/l PPT. Bars correspond to 5 mm

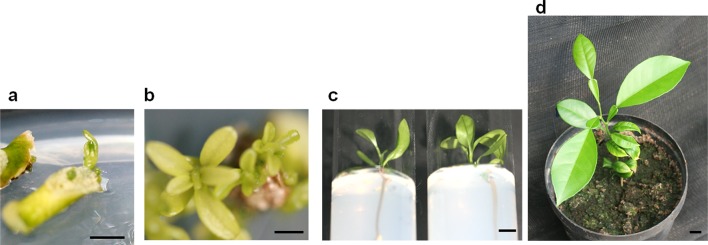

Establishment of PPT-based selection system for ‘Maltese half-blood’ transformation

PPT (0.25 mg/l) resistance was used as a selectable marker to enable selection of the transformed cells after co-cultivation of epicotyl segments with LBA4404. The transfer was carried out in MT including 500 mg/l Carbenicillin. Using the first procedure (0.25 PPT), bud formation could be observed, but their development into shoots was stopped at the 8th week of culture under light conditions and the number of buds per explant was 12.67 ± 1.67. When following the second procedure (PPT concentration was reduced to 0.125 mg/l), the number of generated buds was increased by 1.7-fold (21.67 ± 2.33 buds/explant) as shown in Table 7. At this stage, GUS transient expression (Fig. 3a) was detectable in a high number of buds that were generated under reduced PPT concentration (9.54 ± 3.33 vs 4.67 ± 0.34 buds/explant under 0.125 and 0.25 mg/l PPT, respectively).

Table 7.

Effect of reducing PPT concentration on the number of generated buds/explant

| PPT (mg/l) | Bud number/explant during selection |

|---|---|

| 0.25 | 12.67 ± 1.67b |

| 0.125 | 21.67 ± 2.33a |

Cultures were carried out in the presence of 4 mg/l BAP and 0.3 mg/l IAA. Data are mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. Values followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Student’s t test

Fig. 3.

Regeneration of transformed plants from Maltese epicotyl segments using PPT resistance as selectable marker. a Explants maintained in MT added with 4 mg/l of BAP and 0.3 mg/l of IAA in the presence of 500 mg/l of Carbenicillin and 0.25 mg/l of PPT for 3 weeks in the dark followed by 2 weeks of light. b Proliferation of buds after reducing the concentrations of PPT and Carbenicillin to 0.125 and 250 mg/l, respectively. c Transfer of shoots to ½ MS medium amended with 1 mg/l of IBA for rooting. d A transformed ‘half-blood Maltese’ plant after acclimatization under controlled greenhouse conditions. Bars correspond to 5 mm

An additional cultivation period of 4 weeks, in the presence of 0.125 mg/l of PPT, was also assessed using two different procedures based on two different antibiotic concentrations. We found that the number of shoots (8.78 ± 1.33 shoots/explant) showing GUS transient expression (Fig. 3b) was more elevated in samples exposed to 250 mg/l Carbenicillin compared to that of samples subjected to 500 mg/l carbenicillin.

For rooting, PPT was omitted from the culture medium for six additional weeks, while, Carbenicillin was maintained. Our results showed that reducing Carbenicillin concentration increased significantly the number of rooted plantlets per selected explant by 3.3 fold (14.33 ± 3.48 vs 4.33 ± 1.85 using 250 and 500 mg/l Carbenicillin, respectively).

In total, 70 putatively transformed plantlets were obtained based on the optimized conditions of selection relying mainly on reducing the concentrations of both PPT and Carbenicillin to 0.125 and 250 mg/l, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Gus assays. a Buds showing GUS expression. b Regenerated shoots exhibiting GUS expression. Bars correspond to 5 mm

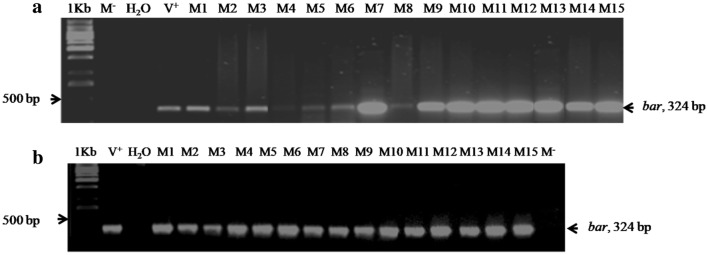

Confirmation of plantlet transformation based on GUS and PCR assays

GUS assay on the 70 regenerated plants revealed that 21.24% were GUS positive (15 plants), 14.28% chimeric (10 plants) and 78.57% GUS negative (45 plants). PCR amplifications using the extracted DNA and the primers of bar gene were carried out on the different putatively transformed plants after rooting. The expected band of 324 bp (Fig. 5a) was detected in the 15 GUS positive ones (21.24%), but not in the control and chimeric ones.

Fig. 5.

Molecular analyses of transformed ‘half-blood Maltese’ plants. a PCR amplification of genomic DNA from control and transformed plants. Specific primers of bar gene were used for the amplification of the corresponding 324 bp DNA fragment. M−: a non-transformed plant; V+: pPZP200-bar-gus-intron; M1-M15: transformed plants; 1 Kb: 1 Kb DNA ladder. b RT-PCR on transgenic M1-M15 vitroplants

RT-PCR was carried out using the same primers to detect the corresponding transcript (Fig. 5b) and, among the 70 regenerated plantlets, only the 15 GUS positive plantlets (21.42%) showed Bar gene expression.

Discussion

The ‘Maltese half-blood' (Citrus sinensis) variety is known for its agro-economic importance in Tunisia (Zouaghi et al. 2019). Nowadays, orchard aging and global warming negatively influenced the Maltese market (Ghaderi et al. 2018). An efficient in vitro regeneration system is a prerequisite for a sustainable management of Maltese orchards (Ghaderi et al. 2018). Here, we established for the first time both an in vitro regeneration system and a genetic transformation procedure useful for the rehabilitation and genetic improvement of this important cultivar. The developed regeneration-protocol was performed using epicotyl explants leading to satisfactory bud formation and plantlet regeneration efficiencies. When compared to other explant types, epicotyl segments are largely used beside being the most responsive ones for citrus plant regeneration and transformation (Febres et al. 2011; Ghaderi et al. 2018).

Explant cutting modes were found to affect the regeneration efficiency from epicotyl explants in citrus. In fact, different cut modes were previously tested like the transversal cut that was described as the easiest and the most popular one but it gave rise to the fewest bud number (Moore et al. 1992; Pena et al. 2004). The longitudinal cut mode has been rarely used to develop in vitro plantlet regeneration protocols (Yu et al. 2002; Kayim et al. 2004). However, the oblique cut mode has been reported to be the most suitable one for citrus in vitro regeneration (Duan et al. 2007). Our results, using the Tunisian ‘Maltese half-blood’ variety, further consolidated the findings previously reported by Duan et al (2007) as they indicated that the oblique cut mode performed on epicotyl segments was the most suitable one for citrus in vitro plantlet regeneration.

Moreover, in our experiments, BAP:IAA hormonal combination allowed an efficient regeneration capacity from epicotyl explants when applied at the appropriate ratio (4:0.3). According to literature, BAP was the most used hormone for bud formation, whereas auxin did not affect shoot regeneration (Garcia-Luis et al. 1999). The use of the cytokinin zeatin riboside has been reported for sweet orange, grapefruit, citron, and citrange rootstock regeneration (Marutani-Hert et al. 2012). Also, the application of a combination treatment containing 0.5 mg/l kinetin and 0.5 mg/l IAA gave rise to a regeneration percentage of 40% in Citrus sinensis, indicating positive interactions of IAA with kinetin when used at appropriate concentrations (Duan et al. 2007). This differs from previous findings that indicated a marginal contribution of auxins to bud formation (Garcia-Luis et al. 1999). This might be due to Citrus genotype-effect beside the specific response to different hormone concentrations.

On the other hand, in our established regeneration system, we found that maintaining cultivated explants in the dark for 3 weeks allowed the highest bud and shoot formation efficiencies. This is in accordance with previous reports describing the positive effect of dark incubation on the regeneration and transformation of internode explants of sweet orange, grapefruit, citron, and a citrange rootstock (Marutani-Hert et al. 2012).

In the frame of Citrus improvement, it is well known that many citrus species exhibited difficulties to be bred (Donmez et al. 2013). Therefore, efficient biotechnological tools are required to face increased threats of biotic and abiotic stresses beside the high competition in the international market (Donmez et al. 2013). Genetic transformation, as the most efficient tool for plant genetic improvement purposes, has been established for many Citrus species in many countries, but not for the Tunisian ‘Maltese half-blood’ elite variety. In the present study, a successful Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was performed for the Maltese variety based on the developed regeneration protocol using epicotyl segments. In this developed transformation procedure, the LBA4404 A. tumefaciens strain was used and PPT was applied as a selective agent. Most of the A. tumefaciens strains used for genetic transformation are EHA 105 and C58. The strain C58 C1 had the highest transformation efficiency (45%), while, strains EHA101-5 and LB4404 allowed transformation efficiencies of 29 and 0%, respectively (Febres et al. 2011). Nevertheless, in our study, we proved that the use of LBA4404 harboring the pPZP200 Bar-Gus-intron was valuable for the ‘Maltese half-blood’ variety. Such a variability in the results would be related to citrus species capacities or cultivar specificity correlated to cell or tissue competence that would be associated to age and type of explant used beside the transformation procedure from co-cultivation conditions to the adequate selection (Febres et al. 2011).

Antibiotics are extensively used as agents of selection in the initial stages of the plant genetic transformation and their efficacy varied according to the regeneration system used across a wide range of plant species (Sundar and Sakthivel 2008). The susceptibility to antibiotics varied among species, genotypes and explant types (Padilla and Burgos 2010). It was reported that the choice of the agent of selection to recover transformed cells is crucial for citrus genetic transformation to eliminate both chimeras and escapes that can occur during this process. In previous reports, both kanamycin (Ballester et al. 2008; Oliveira et al. 2015) for citrus, and Basta for Citrus sinensis (Li et al. 2003), and Citrus reticulata Blanco (Li et al. 2002) were described to be useful for genetic transformation. In our study, PPT (0.25 mg/l) was successfully used as the agent of selection for the first time when reduced by half during the latest 8 weeks of the selection phase. These findings are in accordance with those previously reported by Pereira et al (2016) showing that PPT applied at 5 mg/l was suitable to prevent the growth of Urochloa brizantha embryogenic calli when studying the efficacy of various agents of selection including kanamycin, hygromycin, phosphinothricin and mannose. Additionally, Jardak-Jamoussi et al. (2008) demonstrated that PPT, when applied at 5 mg/l at the beginning of the selection phase before to be reduced to 2.5 mg/l, was suitable for an efficient selection of transformed pro-embryogenic callus of Vitis vinifera. Moreover, PPT is the principal agent of selection in monocots to distinguish transgenic from non-transgenic events (Ishida et al. 2007; Molinari et al. 2007; Han et al. 2009). In Paspalum notatum, PPT applied at 1 mg/l increased the recovery of transgenic plants and minimized the amount of escapes (approximately 10%), and allowed a transformation frequency of 64.2% in this species (Mancini et al. 2014). Generally, the Bar gene with PPT was considered as the most efficient combination for selecting transformed cells in monocots (Gondo et al. 2005; Pereira et al. 2016).

The established ‘Maltese half-blood’ genetic transformation procedure provided an attractive advancement in breeding programs to permit gene functional studies via either overexpression or silencing of the wild-type gene product. Gene overexpression by means of genetic transformation are being exploited as a powerful screening tool in molecular genetics via allowing geneticists identifying pathway-components that might remain undetected using traditional loss-of-function assays (Prelich 2012). In addition, functional genomics and gene function validation by genetic transformation are perquisite steps before creating novel materials to face climate change. Recently, powerful alternatives for genetic engineering were developed like the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/cas9 (CRISPR/Cas9) system. CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing tool was used for enhancing plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Parmar et al. 2017; Aglawe et al. 2018; Jaganathan et al. 2018; Uniyal et al. 2019; Pathak et al. 2019). Applications of this recently developed technology gave rise to the generation of non-genetically modified (Non-GMO) crops with an improved adaptation to environmental constraints (Farooq et al. 2018). This wonderful CRISPR/Cas9 technology was also successfully applied in a number of horticultural crops including citrus (Song et al. 2016). Thus, our optimized protocol for genetic transformation of the ‘Maltese half-blood’ variety provided a foundation for further research work and engineering assays based on recent genome editing tools.

Conclusion

The ‘Maltese half-blood’ variety, an important agro-economically cultivar in Tunisia, was in vitro studied for the first time for revitalization and improvement purposes. Both in vitro regeneration and genetic transformation procedures using seedling epicotyl segments were successfully established. Our findings highlighted mainly that epicotyl segments are good explants for in vitro regeneration when excised in an oblique manner beside the importance of the dark treatment as well as the BAP:IAA hormone combination included in the MT culture medium. Moreover, in our genetic transformation procedure, we showed the usefulness of the LBA4404 strain and the suitability of PPT as the agent of selection which gave rise to a satisfactory percentage of transformed plants. Our developed systems for regeneration and genetic transformation can be used in future routine applications for ‘Maltese half-blood’ orchard renewal and in breeding programs aiming to promote citrus sub-sector under climate change.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for the financial support of this research.

Abbreviations

- IAA

Indole-3-acetic acid

- MT medium

Murashige and Tucker

- BAP

6-Benzylaminopurine

- PPT

Phosphinothricin

Author contributions

RJ designed the work, developed the regeneration system and the genetic transformation procedure, and analyzed data. RJ and HB wrote the body of the paper. HZ provided the Tunisian ‘Maltese half-blood’ seeds. SG and SM gave technical support. AM and AG coordinated the project together with RJ.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Authors confirmed that experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant government’s regulatory guidelines and regulations.

References

- Aglawe SB, Barbadikar KM, Mangrauthia SK, Madhav MS. New breeding technique “genome editing” for crop improvement: applications, potentials and challenges. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:1. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ani PN, Abel HC. Nutrient, phytochemical, and antinutrient composition of Citrus maxima fruit juice and peel extract. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6:653–658. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida WAB, Mourao FAA, Mendes BMJ, Pavan A, Rodriquez APM. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Citrus sinensis and Citrus limonia epicotyl segments. Sci Agric. 2003;60(1):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Gerding X, Cortés-Bullemore R, Medina C, Romero-Romero JL, Inostroza-Blancheteau C, Aquea F, Arce-Johnson P. Improved salinity tolerance in carrizo citrange rootstock through overexpression of glyoxalase system genes. BioMed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/827951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester A, Cervera M, Peña L. Evaluation of selection strategies alternative to nptII in genetic transformation of citrus. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27(6):1005–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera M, Ortega C, Navarro A, Navarro L, Pena L. Generation of transgenic citrus plants with the tolerance to salinity gene HAL2 from yeast. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2000;75:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira CF, Giordani D, Gurak PD, Cladera-Olivera F, Marczak LDF. Extraction of pectin from passion fruit peel using moderate electric field and conventional heating extraction methods. Innov Food Sci Emerg. 2015;29:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- D’Halluin K, Bonne E, Bossut M, Beuckeleer M, Leemans J. Transgenic maize plants by tissue electroporation. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1495–1505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.12.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhifi W, Mnif W. Valorization of some by-products of Maltese orange from Tunisia: peel essential oil and seeds oil. Anal Chem Lett. 2012;1:397–401. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez A, Cervera M, Perez RM, Romero J, Fagoaga C, Cubero J, López MM, Juárez JA, Navarro L, Peña A. Characterisation of regenerants obtained under selective conditions after Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrus explants reveals production of silenced and chimeric plants at unexpected high frequencies. Mol Breed. 2004;14(2):171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Donmez D, Simsek O, Izgu T, Kacar YA, Mendi YY. Genetic transformation in citrus. Sci World J. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/491207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan XY, Liu X, Fan J, Li DL, Wu RC, Guo WW. Multiple shoot induction from seedling epicotyls and transgenic citrus plant regeneration containing the green fluorescent protein gene. Bot Stud. 2007;48:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat I, Damergi C, Boukhris H, Hammami M, Cherif M, Nasraoui B. Etude des caractéristiques pomologiques, physico-chimiques et sensorielles de la maltaise demi-sanguine cultivée dans les nouvelles zones agrumicoles en Tunisie. J New Sci Agri Biotech. 2016;31(13):1832–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq M, Ullah A, Lee DJ, Alghamdi SS. Terminal drought-priming improves the drought tolerance in desi and kabuli chickpea. Int J Agric Biol. 2018;30:1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Febres VJ, Lee RF, Moore GA. Transgenic resistance to Citrus tristeza virus in grapefruit. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27(1):93–104. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febres V, Fisher L, Khalaf A, Moore GA. Citrus transformation: challenges and prospects. In: Alvarez M, editor. Genetic transformation. Rijeka: InTech; 2011. pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gifruit (2018) Groupement Interprofessionnel des fruits. https://www.gifruits.com.

- Ghaderi I, Sohani MM, Mahmoudi A. Efficient genetic transformation of sour orange, Citrus aurantium L. using Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing the coat protein gene of Citrus tristeza virus. Plant Gene. 2018;14:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Luis A, BordoÂn Y, Moreira-Dias JM, Molina RV, Guardiola JL. Explant orientation and polarity determine the morphogenic response of epicotyl segments of Troyer citrange. Ann Botany. 1999;84:715–723. [Google Scholar]

- Gondo T, Tsuruta S, Akashi R, Kawamura O, Hoffmann F. Green, herbicide resistant plants by particle inflow gun-mediated gene transfer to diploid bahia grass (Paspalum notatum) J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:1367–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XQ, Liu JH. Genetic transformation and genes for resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses in Citrus and its related genera. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2013;113:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Han YJ, Kim YM, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Cho KC, Chandrasekhar T, Song PS, Woo YM, Kim JI. Production of purple-colored creeping bentgrass using maize transcription factor genes Pl and Lc through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekema A, Hirsch PR, Hooykaas PJJ, Schilperoort RA. A binary plant vector strategy based on separation of vir and T-region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti-plasmid. Nature. 1983;303:179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Hiei Y, Komari T. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of maize. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1614–1621. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaganathan D, Ramasamy K, Sellamuthu G, Jayabalan S, Venkataraman G. CRISPR for crop improvement: an update review. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:985. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardak-Jamoussi R, Bouamama B, Mliki A, Ghorbel A, Reustle GM. The use of phosphinothricin resistance as selectable marker for genetic transformation of grapevine. Vitis. 2008;47(1):35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jardak-Jamoussi R, Winterhagen P, Bouamama B, Dubois C, Mliki A, Wetzel T, Ghorbel A, Reuslte GM. Development and evaluation of a GFLV inverted repeat construct for genetic transformation of grapevine. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2009;97:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. GUS fusions: Beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987;6(13):3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayim M, Ceccardi TL, Berretta MJG, Barthe GA, Derrick KS. Introduction of a citrus blight-associated gene into Carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbc. X Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.) by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 2004;23:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0823-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhoua H. Quelques réflexions sur le développement de l’agrumiculture en Tunisie. Revue de l’INAT. 1997;12:179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Li DD, Shi W, Deng XX. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of embryogenic calluses of Ponkan mandarin and the regeneration of plants containing the chimeric ribonuclease gene. Plant Cell Rep. 2002;21(2):153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Li DD, Shi W, Deng XX. Factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated embryogenic callus transformation of Valencia sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) containing the pTA29-barnase gene. Tree Physiol. 2003;23:1209–1215. doi: 10.1093/treephys/23.17.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Woitovich N, Permingeat HR, Podio M, Siena LA, Ortiz JPA, Pessino SC, Felitti SA. Development of a modified transformation platform for apomixes candidate genes research in Paspalum notatum (bahiagrass) Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2014;50:412–424. [Google Scholar]

- Marutani-Hert M, Bowman KD, McCollum GT, Mirkov TE, Evens TJ, Niedz RP. A dark incubation period is important for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of mature internode explants of sweet orange, grapefruit, citron and a citrange rootstock. PLoS ONE ONE. 2012;7:e47426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metoui N, Hamrouni L, Benhbal W, Dhaoudi F, Benbrahem R, Betaeib T. La régénération et l’assainissement viral des agrumes en Tunisie par la technique du microgreffage des méristèmes in vitro. J New Sci. 2014;12:2. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari HBC, Bespalhok JC, Kobayashi AK, Pereira LFP, Vieira LGE. Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transformation of Swingle citrumelo (Citrus paradise Macf x Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) using thin epicotyl sections. Sci Hortic. 2004;99(3–4):379–385. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari HBC, Marur CJ, Daros E, Campos MKF, Carvalho JFRP, Bespalhok Filho JC, Pereira LFP, Vieira LGE. Evaluation of the stress-inducible production of proline in transgenic sugarcane (Saccharum spp.): osmotic adjustment, chlorophyll fluorescence and oxidative stress. Physiol Plant. 2007;130(2):218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Moore GA, Jacono CC, Neidigh JL, Lawrence SD, Cline K. Agrobacterium mediated transformation of citrus stem segments and regeneration of transgenic plants. Plant Cell Rep. 1992;11(5–6):238–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00235073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Tucker DPH. Growth factors requirements of citrus tissue culture. Int Citrus Symp. 1969;3:1155–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Fuster O, Fleming GH, Albiach-Marti MR, Gowda S, Dawson WO, Crosser JW. Citrus tristeza virus (CTV) resistance in transgenic citrus based on virus challenge of protoplasts. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2003;39(6):567–572. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla IMG, Burgos L. Aminoglycoside antibiotics: structure, functions and effects on in vitro plant culture and genetic transformation protocols. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29(11):1203–1213. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0900-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey P, Irulappan V, Bagavathiannan MV, Senthil-Kumar M. Impact of combined abiotic and biotic stresses on plant growth and avenues for crop improvement by exploiting physio-morphological traits. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:537. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar N, Singh KH, Sharma D, Singh L, Kumar P, Nanjundan J, Khan YJ, Chauhan DK, Thakur AK. Genetic engineering strategies for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and quality enhancement in horticultural crops: a comprehensive review. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(4):239. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0870-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak B, Zhao S, Manoharan M, Srivastava V. Dual-targeting by CRISPR/Cas9 leads to efficient point mutagenesis but only rare targeted deletions in the rice genome. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:158. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1690-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AVC, Vieira LGE, Ribas AF. Optimal concentration of selective agents for inhibiting in vitro growth of Urochloa brizantha embryogenic calli. Afr J Biotechnol. 2016;15(23):1159–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Pena L, Perez RM, Cervera M, Juarez JA, Navarro L. Early events in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Citrus explants. Ann Bot. 2004;94(1):67–74. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G. Gene overexpression: uses, mechanisms, and interpretation. Genetics. 2012;190:841–854. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar IK, Sakthivel N. Advances in selectable marker genes for plant transformation. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(16):1698–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Jia M, Chen K, Kong X, Khattak B, Xie C, Li A, Mao L. CRISPR/Cas9: a powerful tool for crop genome editing. Crop J. 2016;4:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja N, Gill SS. Crop improvement under adverse conditions. Berlin: Springer Science and Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uniyal AP, Mansotra K, Yadav SK, Kumar V. An overview of designing and selection of sgRNAs for precise genome editing by the CRISPR-Cas9 system in plants. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:223. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1760-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Acanda Y, Jia H, Wang N, Zale J. Biolistic transformation of Carrizo citrange (Citrus sinensis Osb 3 Poncirus trifoliata L Raf) Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35(9):1955–1962. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CH, Huang S, Chen CX, Deng ZN, Ling P, Gmitter FG. Factors affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and regeneration of sweet orange and citrange. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002;71(2):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zekri S, Laajimi A (2001) Etude de la compétitivité du sous-secteur agrumicole en Tunisie. In: Laajimi A, Arfa L (eds) Le futur des échanges agro-alimentaires dans le bassin méditerranéen: Les enjeux de la mondialisation et les défis de la compétitivité. Zaragoza: CIHEAM, 2001. (Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes; n. 57)

- Zhang YY, Zhang DM, Zhong Y, Chang XJ, Hu ML, Cheng CZ. A simple and efficient in planta transformation method for pommelo (Citrus maxima) using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Sci Hort. 2017;214(5):174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zouaghi G, Najar A, Aydi A, Claumann CA, Zibetti AW, Ben MK, Jemmali A, Bleton J, Moussa F, Abderrabba M, Chammem N. Essential oil components of Citrus cultivar ‘Maltaise demi sanguine’ (Citrus sinensis) as affected by the effects of rootstocks and viroid infection. Int J Food Prod. 2019;22(1):438–448. [Google Scholar]