Abstract

Background

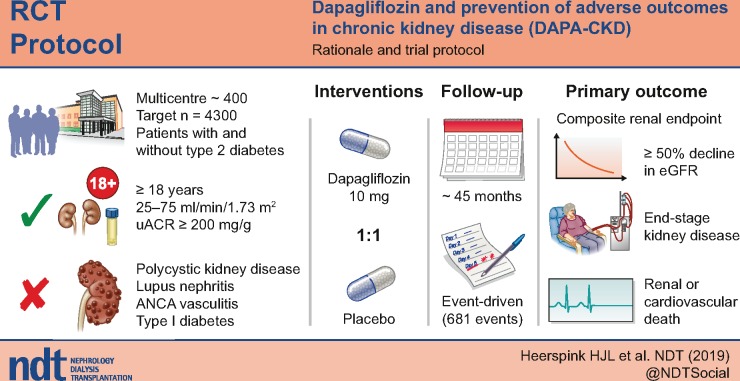

Recent cardiovascular outcome trials have shown that sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors slow the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. Whether these benefits extend to CKD patients without type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease is unknown. The Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in CKD (DAPA-CKD) trial (NCT03036150) will assess the effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on renal and cardiovascular events in a broad range of patients with CKD with and without diabetes.

Methods

DAPA-CKD is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, trial in which ∼4300 patients with CKD Stages 2–4 and elevated urinary albumin excretion will be enrolled. The vast majority will be receiving a maximum tolerated dose of a renin–angiotensin system inhibitor at enrolment.

Results

After a screening assessment, eligible patients with a urinary albumin:creatinine ratio ≥200 mg/g and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) between 25 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 are randomly assigned to placebo or dapagliflozin 10 mg/day. Enrolment is monitored to ensure that at least 30% of patients do not have diabetes and that no more than 10% have an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The primary endpoint is a composite of a sustained decline in eGFR of ≥50%, end-stage renal disease, renal death or cardiovascular death. The trial will conclude when 681 primary renal events have occurred, providing 90% power to detect a 22% relative risk reduction (α level of 0.05).

Conclusion

DAPA-CKD will determine whether the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin, added to guideline-recommended therapies, safely reduces the rate of renal and cardiovascular events in patients across multiple CKD stages with and without diabetes.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, dapagliflozin, randomized controlled clinical trial, sodium–glucose co-transporter inhibitor

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors reduce plasma glucose and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by increasing urinary glucose excretion in a non-insulin-dependent fashion [1]. To date, three large cardiovascular outcome trials have demonstrated that the beneficial effects of these agents extend beyond glycaemic control [2–4]. These trials recruited patients with type 2 diabetes and either established cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors. In all three of these trials, the preservation of renal function has been reported [2–4]. However, the proportion of participants with chronic kidney disease (CKD) was low and the number of patients reaching end-stage renal disease (ESRD) small, highlighting the need for dedicated outcome trials to define the efficacy and safety of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with established CKD. The first trial of SGLT2 inhibition to include patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD reported that canagliflozin 100 mg/day reduced the risk of a composite renal endpoint (comprised of doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD or death due to renal or cardiovascular disease) by 30% compared with placebo [5].

In the cardiovascular and renal outcome trials described above, the renoprotective benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitors did not appear to be completely explained by the modest reductions in HbA1c, which are attenuated in patients with a low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Other mechanisms of benefit, including activation of tubuloglomerular feedback and reduction in intrarenal hypoxia, have been proposed to explain the salutary effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on renal function; these may be relevant to patients with CKD who do not have diabetes [6, 7].

The Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse outcomes in CKD (DAPA-CKD) trial is testing the hypothesis that treatment with dapagliflozin is superior to placebo in reducing the risk of renal and cardiovascular events in patients with CKD (with or without concomitant type 2 diabetes) already receiving an optimized dose of either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as background renoprotective therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study objective

The primary objective of DAPA-CKD is to assess whether dapagliflozin compared with placebo reduces the composite endpoint of worsening of renal function (defined as a composite endpoint of an eGFR decline >50%, ESRD or renal death) or cardiovascular death in patients with CKD. In addition, the trial will examine the effects of dapagliflozin, compared with placebo, on the composite endpoint of worsening of renal function, the composite endpoint of hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality. Additional exploratory endpoints include changes in eGFR and urinary albumin: creatinine ratio (UACR) as well as health-related quality of life. The trial is registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03036150).

Overall study design

DAPA-CKD is a multinational, multicentre, event-driven, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial that will recruit ∼4300 patients at nearly 400 sites in 21 countries (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the overall study design.

FIGURE 1.

Countries participating in DAPA-CKD.

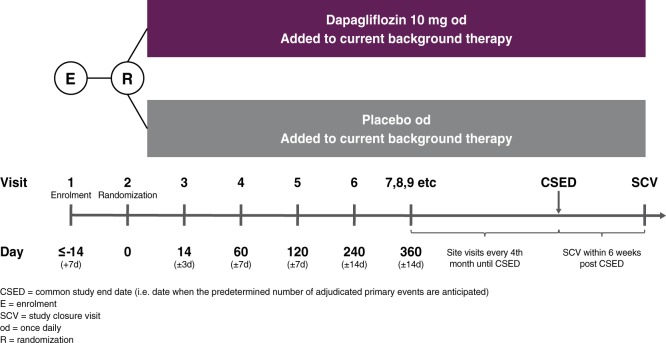

FIGURE 2.

DAPA-CKD study diagram.

Trial participants

The trial participants are adults with CKD with an eGFR ≥25 but ≤75 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a UACR ≥200 mg/g but ≤5000 mg/g (≥22.6 to ≤565 mg/mmol). Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main inclusion and exclusion criteria of the DAPA-CKD trial

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Study periods

Enrolment

Potentially eligible patients are invited for screening. Those with a central laboratory eGFR ≥25 but ≤75 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a UACR between ≥200 and ≤5000 mg/g and who meet all other inclusion and no exclusion criteria can be randomized within 14 (±7) days after the screening visit. Patients with autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, lupus nephritis or anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) vasculitis are not enrolled. Additionally, patients receiving immunotherapy for primary or secondary renal disease within 6 months prior to enrolment are also excluded.

Due to the high day-to-day variation in serum creatinine (eGFR) and UACR, a disqualifying laboratory test for these variables during the screening period can be repeated once at the discretion of the local investigator. Patients who do not qualify based on inclusion or exclusion criteria can be re-enrolled once after appropriate changes to clinical management.

Randomization and stratification

Approximately 4300 patients will be randomly assigned 1:1 to dapagliflozin 10 mg/day or matched placebo. These patients comprise the primary intention-to-treat population for assessing the safety and efficacy of dapagliflozin. Randomization is performed centrally through an interactive web response system on the basis of a computer-generated randomization schedule prepared by the trial sponsor. The stratified randomization scheme is designed to ensure balance in baseline UACR (≤ or >1000 mg/g) and the proportion of patients with and without Type 2 diabetes between treatment groups.

Patients and all study personnel (except the independent data-monitoring committee) are kept blinded to treatment allocation. Study drugs (dapagliflozin and placebo) are packaged in an identical manner, with uniform tablet appearance, labelling and administration schedule. Dapagliflozin 10 mg/day was selected for this study based on broad clinical experience demonstrating favourable efficacy and tolerability. Patients are instructed to take their study medication in the morning at approximately the same time of the day throughout the study.

Recruitment is monitored to ensure that a minimum of 30% of the patients were recruited to either the diabetic or non-diabetic subpopulation, there is adequate geographical representation of different regions of the world and that patients are taking an optimized dose of an ACEi or ARB at randomization, i.e. the guideline-recommended evidence-based dose or highest tolerated dose. The number of patients with an eGFR between 60 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the time of randomization was capped on 27 November 2017 to ensure that no more than 10% of trial participants would start the trial within the eGFR range classified as Stage 2 CKD.

Double-blind treatment and management of patients

After randomization, in-person visits are scheduled after 2 weeks, 2, 4 and 8 months and at 4-month intervals thereafter. Each follow-up visit includes a collection of information about potential endpoints, adverse events, concomitant therapies and study drug adherence. In addition, vital signs are recorded and blood and urine are collected for laboratory measurements. Finally, further study medication is dispensed. A final study closeout visit will be conducted within 6 weeks of the end of the study, which will occur once 681 patients have experienced a primary outcome event (see below and Figure 2).

Patients who experience a renal or cardiovascular event are advised to continue study medication. A (temporary) dose reduction to dapagliflozin 5 mg/day (or equivalent reduction in matching placebo) or temporary study drug discontinuation is permitted in patients with clinically relevant volume depletion, hypotension or unexpected worsening of renal function.

Discontinuation of the study drug is required for patients who develop diabetic ketoacidosis or become pregnant. Patients can also decide to discontinue the study drug at any time. Patients who prematurely discontinue the study drug (but do not withdraw consent) are encouraged to continue follow-up visits as scheduled or, if that is not possible, they are given the option of follow-up by telephone, contact with a family member or through healthcare professionals known to the patient.

Outcome definitions and event adjudication

Efficacy outcomes

The primary outcome for the evaluation of the effect of dapagliflozin on delaying the progression of renal disease is the time to the first occurrence of any of the following components of the composite renal endpoint: ≥50% eGFR decline (confirmed by a second serum creatinine measurement at least 28 days later), the onset of ESRD or renal or cardiovascular death (Table 2). Secondary and exploratory endpoints are listed in Table 2. A blinded and independent event adjudication committee (EAC) consisting of nephrologists, cardiologists and neurologists will adjudicate the primary and secondary endpoints, except for the sustained ≥50% eGFR decline and sustained eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (which will be ascertained from central laboratory measurements).

Table 2.

Primary, secondary, exploratory and safety endpoints of DAPA-CKD

Primary composite endpoint

|

Secondary endpoints

|

Exploratory endpoints include (but not limited to)

|

Safety endpoints

|

ESRD is defined as the need for maintenance dialysis (peritoneal or haemodialysis) for at least 28 days and renal transplantation or sustained eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 for at least 28 days. Renal death is defined as death due to ESRD when dialysis treatment was deliberately withheld (dialysis was not started or discontinued) for any reason. The 28-day time frame is included in the definition of the ESRD endpoint definition to avoid misclassification of acute kidney injury (AKI) as ESRD. If the dialysis treatment was stopped before Day 28 due to death, futility or patient electing to stop dialysis, then the EAC will decide whether or not the need for dialysis was likely to be permanent and meets the ESRD criteria.

The EAC will also be responsible for adjudicating possible myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke and transient ischaemic attack.

Safety outcomes

Selected adverse event data are being collected, given the extensive prior experience with dapagliflozin. Only serious adverse events and adverse events of interest or leading to premature study drug discontinuation, study drug interruption or dose reduction are recorded. Adverse events of interest include volume depletion, renal events, major hypoglycaemia, fractures, potential diabetic ketoacidosis, adverse events leading to amputations or adverse events leading to an increased risk of lower limb amputations.

Background medication

Efforts are being made to maintain patients on their stable optimized dose of ACEi or ARB for the duration of the trial. Management of blood pressure, lipids and glucose and the use of other essential therapies is left to the discretion of the investigator, in keeping with local clinical practice and guidelines.

Statistical considerations

Sample size calculation

DAPA-CKD is an event-driven trial. The sample size is based on the expected rate of the primary efficacy endpoint and the anticipated size of the effect of dapagliflozin treatment. With the recruitment of at least 4000 patients, the trial will have 90% power to detect a relative risk reduction of 22% in the primary endpoint based on primary events being observed in 681 patients and a two-sided P-value of 0.05. Assumptions underlying the sample size calculation included a placebo event rate of 7.5% events per year (based on event rates observed in relevant patients in prior trials), an annual drug discontinuation rate of 6%, 1% loss to follow-up, a recruitment period of 24 months and a total study duration of ∼45 months.

An interim analysis will be conducted when ∼75% of the primary events are confirmed, using a Haybittle–Peto rule. At the time of the interim analysis, early termination of the trial can be recommended if the superiority of dapagliflozin over placebo is demonstrated for the primary composite at a one-sided α level of 0.001. The significance level for the final analysis will be determined by the Haybittle–Peto function based on the actual number of events and timing of the interim analysis.

Efficacy assessment primary analysis

The primary efficacy analysis will be based on the intention-to-treat population, defined as all validly randomized patients. In the analysis of the primary composite endpoint, the treatments (dapagliflozin and placebo) will be compared using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with a factor for the treatment group, stratified by the factors used at randomization (type 2 diabetes and UACR) and adjusted for baseline eGFR. In general, the analysis will use each patient’s last contact as the censoring date for patients without any primary outcome event. The P-value, hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval will be reported. Kaplan–Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence to the first occurrence of any event in the primary endpoint will be calculated and plotted.

Secondary and exploratory efficacy assessment

The secondary efficacy outcomes will be tested in a similar manner as the primary efficacy outcomes. If superiority is achieved for the primary efficacy outcomes, the secondary outcomes will be tested in hierarchical order as follows: (i) composite renal endpoint consisting of 50% eGFR decline, ESRD or renal death; (ii) composite endpoint of CV death or hospitalization for heart failure; and (iii) time to death from any cause. Statistical significance is required before proceeding to test the next hypothesis in the hierarchical procedure.

Longitudinal repeated eGFR measurements from the two treatment groups will be compared using the mixed-effects maximum likelihood repeated measures analysis. The change in eGFR using on-treatment values will be the dependent variable. The treatment time interaction term is the parameter of interest and indicates the eGFR slope difference between dapagliflozin and placebo.

Patient-reported outcomes

Health-related quality-of-life outcomes will be recorded using the EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) index score and Kidney Disease Quality of Life questionnaires assessed at baseline and every 4 months during the trial.

Study oversight

The trial is overseen by an executive committee consisting of nine academic members and two non-voting members from the study sponsor, AstraZeneca. The executive committee designed the trial, oversees its conduct and will supervise the analysis of the data. The sponsor is responsible for the collection and analysis of data in conjunction with the executive committee. All authors will have access to the study results. An independent data- and safety-monitoring committee reviews safety data and overall study conduct throughout the trial.

DISCUSSION

SGLT2 inhibitors have emerged as powerful agents to reduce the incidence of renal events, as well as cardiovascular events, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Their apparent ability to slow the progressive decline in renal function over time is not completely explained by improved glycaemic control, implicating other, non-glycaemic pathways. These include natriuretic/osmotic diuresis, restoration of tubuloglomerular feedback leading to glomerular afferent vasoconstriction with the reduction in single-nephron hyperfiltration, amelioration of renal tissue hypoxia and attenuation of inflammation and fibrosis [1, 7]. If one or more of these mechanisms are operative, then SGLT2 inhibitors may also be beneficial in patients with CKD without diabetes. DAPA-CKD will test this hypothesis by assessing whether dapagliflozin safely reduces the risk of a composite renal and cardiovascular death endpoint in a broad spectrum of patients with CKD, with and without diabetes, who are already on optimized standard-of-care renoprotective therapy.

An important consideration in the design of DAPA-CKD was the likely efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in patients with CKD without diabetes. Some patients without diabetes have been exposed to SGLT2 inhibitors in prior studies. Collectively these earlier studies showed that SGLT2 inhibition induced glycosuria and led to reductions in blood pressure, body weight and serum urate [8, 9]. With most glucose-lowering drugs, hypoglycaemia is a particular safety concern. However, the glycosuria induced by SGLT2 inhibitors diminishes with diminishing blood glucose concentrations and filtered glucose load, which is why hypoglycaemia is not inherently a risk with these agents. In addition, a compensatory increase in basal hepatic glucose production following urinary glucose loss helps maintain fasting plasma glucose at euglycaemic levels in individuals without diabetes [10]. Additionally, in patients with CKD, the filtered glucose load is reduced due to decreased glomerular glucose filtration. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that in a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials enrolling patients with type 2 diabetes and eGFR between 15 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, the occurrence of hypoglycaemia was similar in the placebo and dapagliflozin treatment groups [11].

We are collecting other specific safety data relevant to glucose-lowering therapy in general and SGLT2 inhibitors in particular, including information on fractures, diabetic ketoacidosis, amputations and AKI. AKI is of particular interest in DAPA-CKD because the haemodynamic actions of SGLT2 inhibitors may lead to an initial reduction in eGFR, similar to that seen with an ACEi or ARB, albeit due to a different purported haemodynamic mechanism (i.e. afferent arteriolar constriction with SGLT2 inhibitors compared with efferent arteriolar dilatation with renin–angiotensin system blockers) [12]. Despite these similarities, fewer episodes of AKI were reported with SGLT2 inhibition in the Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58 (DECLARE-TIMI 58), Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients-Removing Excess Glucose (EMPA-REG OUTCOME), Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) and Canagliflzoin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Establish Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) programmes, although these findings are based on investigator-reported adverse events that did not have a specific definition and were not adjudicated [2–5]. To properly determine the effects of dapagliflozin on AKI in patients with CKD, all potentially severe AKIs, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine compared with the last central laboratory measurement, are being adjudicated by the independent EAC. An unexpected increase in the rate of lower limb amputation was reported with canagliflozin in the CANVAS programme but not in the CREDENCE trial [3, 5]. This has not been observed with dapagliflozin in any prior study, including DECLARE-TIMI 58 and the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure (DAPA-HF), and it was also not seen with empagliflozin in EMPA-REG OUTCOME [2, 4, 13]. However, it is a regulatory requirement that all amputations, and events predisposing to increased risk of amputation, must be collected in all ongoing SGLT2 inhibitor trials, including DAPA-CKD.

From an efficacy perspective, DAPA-CKD will determine the effect of dapagliflozin on a composite renal endpoint, which has been used in previous CKD outcome trials. The most clinically meaningful component of this endpoint is ESRD, defined as the initiation of dialysis for >28 days or renal transplantation. A sustained eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 is also included in the definition of ESRD. It is considered clinically relevant given the increased risk of mortality and decreased quality of life in individuals in whom the eGFR falls below this level. A 50% eGFR decline, equivalent to an ∼80% increase in serum creatinine, is an additional component, contrasting with some other trials that instead have variously used a doubling of serum creatinine or 40% eGFR decline as a component of a composite renal endpoint [14]. We decided not to use a 40% eGFR decline, given that dapagliflozin may cause an acute, haemodynamically mediated reduction in eGFR. This can potentially cause declines in eGFR of up to 40%, which do not reflect the true progression of CKD, diminishing the ability to differentiate between placebo and dapagliflozin and increasing the risk of a type 1 error (T. Greene, submitted for publication). A doubling of serum creatinine was not chosen because a 50% eGFR decline has been shown to be an equally robust measure of the significant decline in renal function and may decrease the sample size and operational complexity of the trial. The primary endpoint also includes death due to renal or cardiovascular causes. All-cause mortality was not included since dapagliflozin is not expected to influence deaths unrelated to renal or cardiovascular causes.

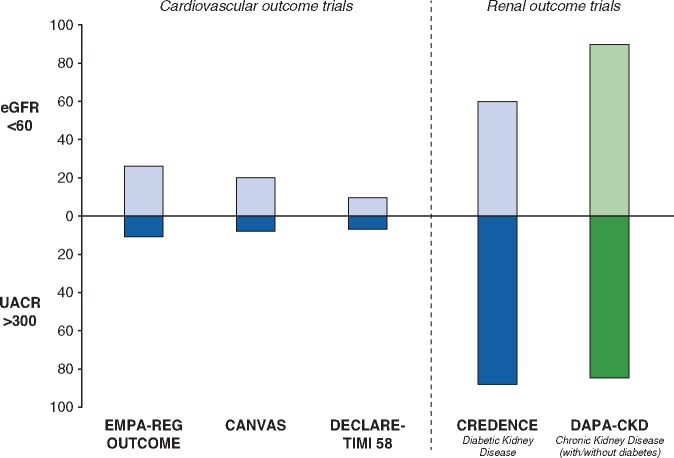

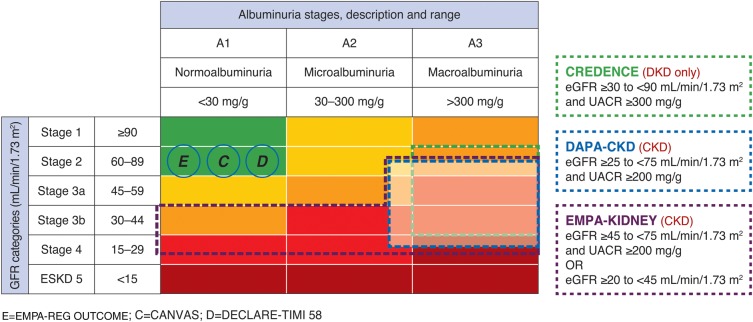

How do DAPA-CKD participants compare with participants enrolled in other SGLT2 inhibitor trials? A minority of patients recruited into cardiovascular outcome trials of SGLT2 inhibitors had CKD defined by eGFR or UACR. CREDENCE is the only trial to date that has recruited only patients with both type 2 diabetes and CKD. In DAPA-CKD, ∼90% of patients will have an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and at least 80% of participants a UACR >300 mg/g (Figure 3). Considering that both a low eGFR and high UACR are strong risk markers for renal as well as cardiovascular events, it is expected that cardiovascular event rates in DAPA-CKD will be at least comparable to the prior SGLT2 cardiovascular outcome trials. In comparing DAPA-CKD with the two other SGLT2 renal outcome trials (CREDENCE and EMPA-KIDNEY), DAPA-CKD will enroll a broader population than CREDENCE; the latter included only patients with type 2 diabetes (Figure 4). The EMPA-KIDNEY trial, assessing the effect of empagliflozin compared with placebo, extends the inclusion criteria further and also enrols patients with type 1 diabetes and patients with UACR <200 mg/g if their eGFR is between 20 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 4). Overall, these three trials will help to define the optimum use of SGLT2 inhibitors in the management of CKD.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR ≥300 mg/g in completed SGLT2 inhibitor trials compared with DAPA-CKD. Interim baseline data from DAPA-CKD (data cut September 2019) were used to create the figure.

FIGURE 4.

National Kidney Foundation classification of chronic kidney disease. The UACR and eGFR range for enrolment in the CREDENCE (green), DAPA-CKD (blue) and EMPA-KIDNEY (purple) trials are shown. White-shaded area indicates the eGFR and UACR inclusion criteria in the DAPA-CKD trial. Cardiovascular outcome trials are indicated in the circles and positioned based on their mean eGFR and median UACR level.

During the conduct of the DAPA-CKD trial, the results of two other large cardiovascular outcome trials with dapagliflozin, DECLARE-TIMI 58 and DAPA-HF became available. The DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial reported that in patients with type 2 diabetes with predominantly preserved renal function who had or were at risk of cardiovascular disease, dapagliflozin significantly lowered the rate of the composite endpoint heart failure or cardiovascular death by 17% and the risk of a composite endpoint of 40% eGFR decline, ESRD and renal death by 47% [4]. The DAPA-HF trial demonstrated that in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction with or without type 2 diabetes, dapagliflozin significantly reduced the risks of the composite primary outcome of heart failure or cardiovascular death [13]. These effects were remarkably consistent both in patients with and without type 2 diabetes as well as in patients with or without CKD. Moreover, the trial reported that the rate of serious renal-related adverse events was significantly lower in the dapagliflozin (1.6%) compared with the placebo group (2.7%; P = 0.009). These results set expectations for patients with CKD, but they have to be confirmed in the DAPA-CKD study.

In summary, the DAPA-CKD study is the first dedicated clinical trial to explore the potential benefits and risks of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients across multiple CKD stages both with and without diabetes who are already receiving evidence-based renoprotective therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Members of the DAPA-CKD executive committee:

H.J.L. Heerspink (co-chair), D.C. Wheeler (co-chair), G. Chertow, R. Correa-Rotter, T.Greene, F.-F. Hou, J. McMurray, P. Rossing, R.Toto, B. Stefansson and A.M. Langkilde.

Members of the DAPA-CKD independent data-monitoring committee:

Marc A. Pfeffer (Chair; Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA), Stuart Pocock (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK), Karl Swedberg (University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden), Jean L. Rouleau (Montreal Heart Institute, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), Nishi Chaturvedi (University College London, London, UK), Peter Ivanovich (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA), Andrew S. Levey (Tufts Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) and Heidi Christ-Schmidt (Statistics Collaborative, Washington, DC, USA).

Members of the DAPA-CKD event adjudication committee:

Johannes Mann (co-chair; Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany), Claes Held (co-Chair; Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden), Christoph Varenhorst (Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden), Pernilla Holmgren (Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden) and Theresa Hallberg (Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden).

National coordinators:

Argentina: Walter Douthat, Hospital Privado, Córdoba; Brazil: Roberto Pecoits Filho, Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Curitiba (PUC-PR), Curitiba; Canada: David Cherney, Toronto Hospital, Toronto; China: Fan Fan Hou, Southern Medical University, National Clinical Research Center for Kidney Disease, Guangzhou, China; Denmark: Frederik Persson, Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, Gentofte; Germany: Hermann Haller, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Hannover; Hungary: István Wittmann, Pécsi Tudományegyetem, Pécs; India: Dinesh Khullar, Max Super Speciality Hospital, New Delhi; Japan: Kashihara Naoki, Kawasaki Medical School Hospital, Kurashiki; Mexico: Richardo Correa-Rotter, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubiran, Tlalpan, Mexico City; Peru: Elizabeth Escudero, Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, Lima; Philippines: Rey Isidto, Healthlink Iloilo, Iloilo City; Poland: Michal Nowicki, SPZOZ Uniwersytecki Szpital Kliniczny, Łódź; Russia: Mikhail Batiushin, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don; South Korea: Shin-Wook Kang, Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul; Spain: José Luis Górriz Teruel, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia; Sweden: Hans Furuland, Akademiska sjukhuset, Medicincentrum/Njurmedicinska, Uppsala; Ukraine: Oleksandr Bilchenko, Kharkiv City Clinic of Urgent and Emergency Care, Kharkiv; United Kingdom: Patrick Mark, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow; United States: Jamie Dwyer, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN and Kausik Umanath, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI; Vietnam: Pham Van Bui, Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City.

FUNDING

The DAPA-CKD trial is supported by AstraZeneca.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The DAPA-CKD trial is sponsored by AstraZeneca. The sponsor was involved in the study design, the writing of the report and the decision to submit the article for publication. H.J.L.H. is a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Pharma, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mundi Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe and Retrophin. He received research support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen. G.M.C. serves on the board of directors for Satellite Healthcare. He has served as a consultant for Akebia, Amgen, Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Cricket, DiaMedica, Gilead, Miromatrix, Outset, Reata, Sanifit and Vertex. He has received research support from Amgen and Janssen. He has served on data and safety monitoring boards for Angion, Bayer and Recor. P.R. is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Mundi Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Sanofi Aventis, Merck Sharp and Dome (all honoraria to his institution) and research support from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk. J.M.’s employer, Glasgow University, has been paid by Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardurion, GSK, Novartis and Theracos for participation in clinical trials, advisory boards or symposia (presentations). R.C.R. is a member of DAPA-CKD executive committee and has consulted on clinical trials for AbbVie and Amgen, has served on advisory boards and received honoraria from Boheringer, AstraZeneca and has been a speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer, AbbVie, Takeda, Amgen and Janssen. R.D.T. is a consultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Quintiles, Quest Diagnostics, Relypsa, Reata and MedScape. F.F.H. is a consultant for AbbVie and AstraZeneca and received research support from AbbVie and AstraZeneca. D.C.W. has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Napp, Mundipharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Ono Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline and Vifor Fresenius. P.R. is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Mundi Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Sanofi Aventis and Merck Sharp and Dome (all honoraria to his institution) and research support from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk. B.V.S., M.L. and A.M.L. are AstraZeneca employees.

Contributor Information

for the DAPA-CKD Investigators:

H J L Heerspink, D C Wheeler, G Chertow, R Correa-Rotter, T Greene, F-F Hou, J McMurray, P Rossing, R Toto, B Stefansson, A M Langkilde, Marc A Pfeffer, Stuart Pocock, Karl Swedberg, Jean L Rouleau, Nishi Chaturvedi, Peter Ivanovich, Andrew S Levey, Heidi Christ-Schmidt, Johannes Mann, Claes Held, Christoph Varenhorst, Pernilla Holmgren, Theresa Hallberg, Walter Douthat, Roberto Pecoits Filho, David Cherney, Fan Fan Hou, Frederik Persson, Hermann Haller, István Wittmann, Pécsi Tudományegyetem, Dinesh Khullar, Kashihara Naoki, Richardo Correa-Rotter, Elizabeth Escudero, Rey Isidto, Healthlink Iloilo, Michal Nowicki, Mikhail Batiushin, Shin-Wook Kang, José Luis Górriz Teruel, Hans Furuland, Oleksandr Bilchenko, Patrick Mark, Jamie Dwyer, and Pham Van Bui

REFERENCES

- 1. Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett D. et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms and clinical applications. Circulation 2016; 134: 752–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM. et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW. et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP. et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B. et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2295–2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dekkers CCJ, Gansevoort RT, Heerspink HJL.. New diabetes therapies and diabetic kidney disease progression: the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors. Curr Diab Rep 2018; 18: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rajasekeran H, Cherney DZ, Lovshin JA.. Do effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes give insight into potential use in non-diabetic kidney disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2017; 26: 358–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Komoroski B, Vachharajani N, Boulton D. et al. Dapagliflozin, a novel SGLT2 inhibitor, induces dose-dependent glucosuria in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 85: 520–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lundkvist P, Sjostrom CD, Amini S. et al. Dapagliflozin once-daily and exenatide once-weekly dual therapy: a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study examining effects on body weight and prediabetes in obese adults without diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19: 49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Al Jobori H, Daniele G, Adams J. et al. Determinants of the increase in ketone concentration during SGLT2 inhibition in NGT, IFG and T2DM patients. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19: 809–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dekkers CCJ, Wheeler DC, Sjostrom CD. et al. Effects of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and stages 3b–4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: 2005–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pleros C, Stamataki E, Papadaki A. et al. Dapagliflozin as a cause of acute tubular necrosis with heavy consequences: a case report. CEN Case Rep 2018; 7: 17–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMurray J. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (DAPA-HF) Presented at the European Society for Cardiology Congress 2019, 1 September 2019, Paris,France [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW. et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: results from the CANVAS program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]