Abstract

An anaerobic isolate SG772 belonging to the genus Blautia was isolated from a healthy human faecal sample. When compared using 16s rRNA sequence identity, SG772 showed only 94.46% similarity with its neighbour species Blautia stercoris. As strain SG772 showed both phenotypic and genomic differences from other members of the type species within the genus Blautia, we propose the designation of SG772 as novel species ‘Blautia brookingsii SG772T’.

Keywords: Blautia brookingsii SG772T, culturomics, gut microbiota, new species, taxogenomics

Introduction

The human gut microbiome of the European and North American population is typically dominated by Bacteroides whereas Prevotella dominates in Asian and African populations [1]. To determine the cultivable microbial diversity of the Prevotella-dominant human gut microbiota, faecal samples were cultured from six healthy donors using a high-throughput culturomics approach [2]. A new species of a bacterium belonging to the genus Blautia was isolated during this study. We characterized this strain using the recently proposed taxono-genomics strategy which uses the combination of phenotypic and genomic characterization of the strain to define new species. Herein, we describe strain Blautia brookingsii SG772T (DSM 107275 = CCOS 1888) that was isolated from the healthy human gut microbiota.

Isolation and growth conditions

The strain was isolated on a brain–heart infusion (BHI) agar medium after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C in strict anaerobic conditions (85% nitrogen, 10% carbon dioxide, 5% hydrogen). The strain grew in the pH range 5.5–7.5 with optimum growth at 6.8. No growth of was observed after 20 minutes of thermal shock at 80°C, suggesting its non-spore-forming nature.

Phenotypic characteristics

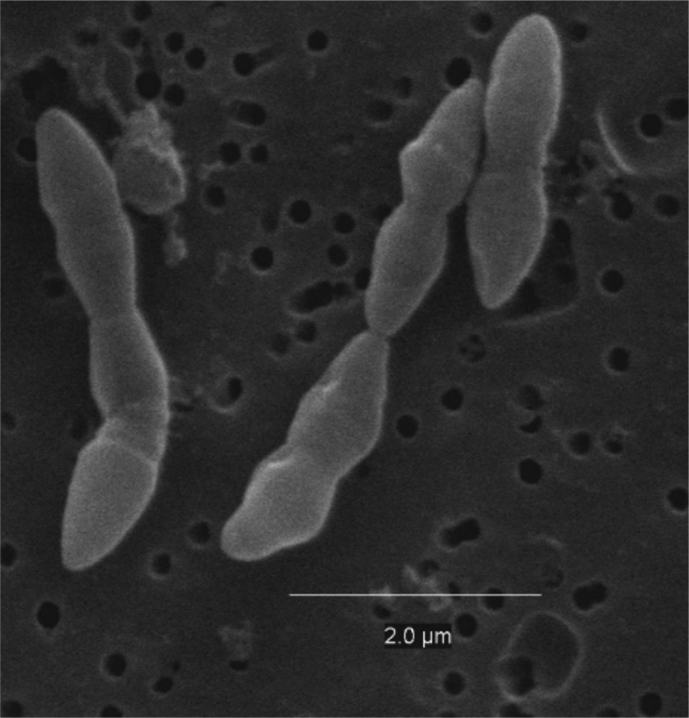

The colonies grown in agar plates appeared to be round, whitish, convex and smooth after 48 hours of anaerobic incubation on BHI plates. Cells were Gram-positive and like a coccobacillus in shape with no flagellum, suggesting a non-motile nature. An overnight culture of the strain SG772T grown in BHI broth was centrifuged at 10 000 × g. The supernatant was then removed to obtain the pellet, which was mixed with 30% glycerol solution and frozen to –80°C and sent to Bowling Green State University Center for Microscopy (Bowling Green, OH, USA) for scanning electron microscopy. The size of the bacterium when imaged using scanning electron microscopy was between 0.5 and 0.8 by between 1.8 and 2.5 μm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of Blautia brookingsii SG772T sp. nov.

Using API ZYM strip, enzymatic activities were determined. Positive enzymatic reactions were observed for esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), leucine arylamidase, acid phosphatase, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, α-glucosidase and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase. Carbon-source utilization of the strain SG772T was determined using a BIOLOG AN plate. The strain SG772T was grown on BHI agar plate for 48 hours and the cells were scooped using sterile cotton swab and mixed in BIOLOG AN fluid until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.01. Then, 100 μL of the mixture was pipetted into 96 wells of the BIOLOG AN plate and incubated for 24 hours. The initial and final optical densities were measured and compared with control. Those wells with optical density >20% compared with control were considered as showing positive nutrient utilization. Results from this test revealed that the strain used 21 substrates with maximum preference for propionic acid followed by l-alanyl-l-glutamine (Table 1). Furthermore, it was able to use complex carbohydrates like palatinose, rhamnose and arbutin, along with organic acids such as α-ketovaleric acid, urocanic acid, glycoxylic acid, fumaric acid, galacturonic acid and α-hydroxybutyric acid. Comparison of the substrate utilization of strain SG772T with other neighbouring Blautia strains is given in Table 1. Additionally, cellular morphology and optimum pH for growth varied among the different species (Table 1). Antibiotic sensitivity testing using the disc diffusion technique showed that the strain SG772T was resistant to tetracycline and streptomycin. However, it was susceptible to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, erythromycin and novobiocin.

Table 1.

Physiological and substrate utilization characteristics of strain SG772T compared with its phylogenetic neighbours

| Characteristics | Blautia brookingsii SG772T (this study) | Blautia stercoris GAM6-1 [11] | Blautia producta DSM2950 [[12], [13], [14]] | Blautia coccoides DSM935 [11,13] | Blautia schinkii DSM10518 [11,14,15] | Blautia luti DSM 14534 [16] | Blautia obeum ATCC29174 [11,17] | Blautia faecis M25 [14] | Blautia hansenii DSM20583 [11,12,14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram stain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oxygen requirement | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic | anaerobic |

| Motility | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cell diameter (μm) | 0.5–0.8 × 1.8–2.5 | 1.5–2.5 × 0.5–0.8 | 1.0–1.5 × 1.0–3.0 | 1.0–1.5 × 1.0–3.0 | 0.8–1.1 × 1.4–2.8 | 0.7–0.9 | 0.8–1.1 × 0.9–1.5 | 1.0–2.3 × 0.5–0.8 | 1–1.5 |

| Endospore production | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cell shape | coccobacilli | coccoid | coccobacilli | coccobacilli | coccoid | coccoid | coccoid | coccobacilli | coccoid |

| Opt. temperature (°C) | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| Mannose fermentation | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – |

| Raffinose fermentation | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + |

| Glycerol | – | + | – | w | v | – | – | – | – |

| Erythritol | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Methyl α-d-glucoside | – | – | – | – | – | NA | + | – | – |

| N-Acetyl-d-glucosamine | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – |

| Arbutin | + | – | – | NA | – | NA | + | – | – |

| Salicin | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Turanose | – | + | + | – | – | NA | + | – | + |

| l-Fucose | + | + | – | – | v | + | + | – | – |

| d/l-Arabitol | – | – | + | – | – | NA | – | – | – |

| Mannitol | – | – | – | + | NA | – | – | – | – |

| Cellobiose | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – |

| d-Maltose | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Trehalose | – | – | NA | + | NA | + | NA | – | + |

| d-Lactose | – | – | + | + | NA | + | + | – | + |

| Glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Galactose | – | – | NA | + | + | + | + | – | NA |

| Rhamnose | + | – | NA | + | NA | – | NA | – | NA |

| d-Fructose | + | – | NA | + | + | + | NA | – | – |

| Propionic acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| l-Alanyl-l-glutamine | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| α-Ketovaleric acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Palatinose | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Urocanic acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Glyoxylic acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N-Acetyl-d-galactosamine | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Fumaric acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| d-Galacturonic acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pyruvic acid | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | – | NA | NA | NA |

Strain identification

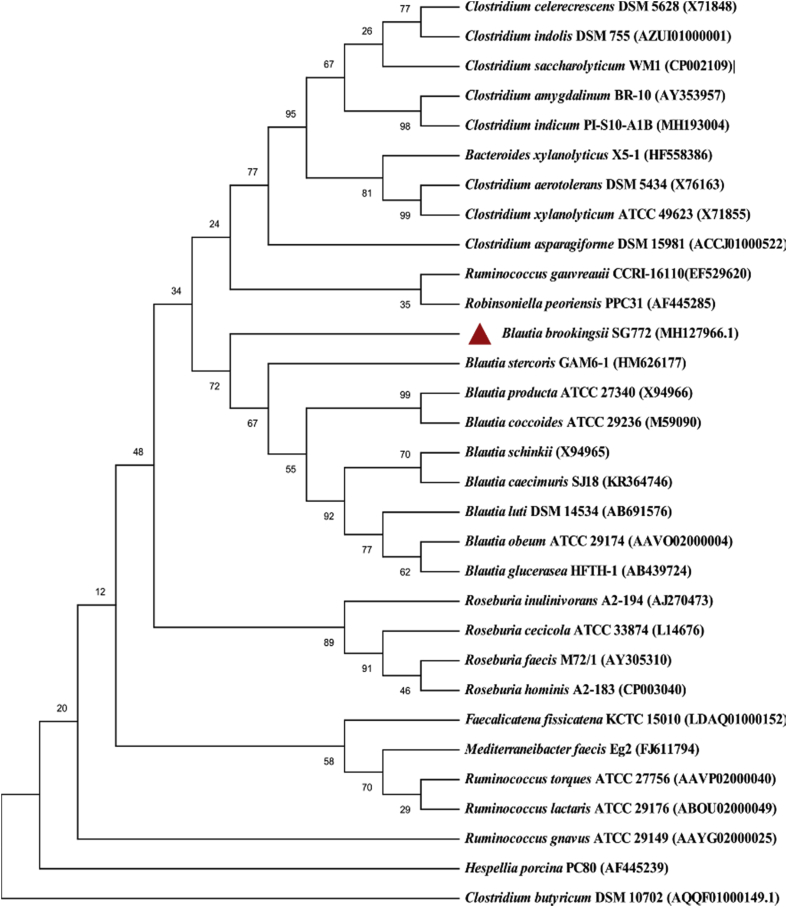

After initial isolation of the strain SG772T, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry was performed, but without identification (score <1.7). Therefore, DNA of the strain was isolated and 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced using Applied Biosystems 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK). The 16S rRNA sequences were trimmed and assembled using Geneious 10.2.3 (https://www.geneious.com). A continuous stretch of 1440 bp of the 16S rRNA gene of strain SG772T was obtained and searched against EzTaxon e-server [3] for identification. This comparison showed that the closest neighbour for strain SG772T is Blautia stercoris GAM6-1 sharing only 94.46% sequence similarity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of strain SG772T with regard to other closely related species. The consensus phylogenetic tree was constructed using 16S rRNA gene sequences from strain SG772T and its top 30 neighbours obtained from EzTaxon. The evolutionary history was inferred using neighbour-joining and the Kimura two-parameter method. The numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap values expressed as percentages of 1000 replications in MEGA X. Clostridium butyricum DSM10702 was taken as an outgroup. GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses.

Genome sequencing and comparison

The genomic DNA was isolated using an E.Z.N.A DNA isolation kit (Omega Bio-tek Inc, GA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The sequencing was performed using Illumina MiSeq (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), 2 × 250 paired end chemistry. The reads were assembled using SPAdes 3.9.0 [4] and the contigs were validated using Quast [5].

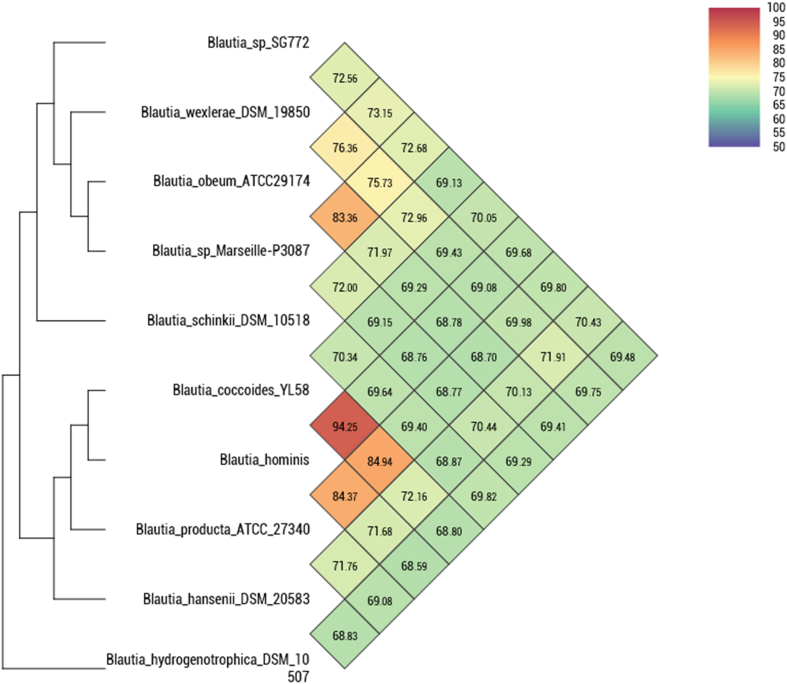

Assembly of the strain SG772T genome produced 52 contigs with the genome size of 3 411 519 bp (N50 = 156 020) and 44.07% GC content. The largest contig was 401 555 bp and the smallest was 610 bp. The genome contains 57 tRNA genes, 1 rRNA gene and 3061 coding sequences. Additionally, for SG772T genome, the open reading frames were predicted using Prodigal 2.6 [6] in Prokka software package [7]. Transfer RNA genes were predicted using Aragorn 1.2 [8] and rRNA genes were annotated using Barrnap 0.7 (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap). Comparison of the SG772T genome with its close species revealed several differences in genome size, G + C content and RNA copies. The closely related species of the strain SG772T for which the genomes were available on NCBI were obtained and the degree of similarity was estimated using OrthoANI software [9]. For the closest neighbours (Fig. 2), OrthoANI values ranged from 69.13% to 73.15%. The type strain SG772T was observed to be close to Blautia wexlerae DSM19850 with 73.15% genomic identity, and Blautia schinkii DSM10518 was the furthest (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) comparison of Blautia brookingsii strain SG772T sp. nov., with other closely related species with standing in nomenclature. Heatmap was generated with OrthoANI values calculated using the OAT software.

Conclusion

As the sequence identity of the phylogenetically closest validated species is <98.7%: the threshold recommended to define a species as per nomenclature [10], we propose the strain SG772T as a new species Blautia brookingsii sp. nov. strain SG772T (broo.king.sii, L., neut., adj., brookingsii, based on the acronym of Brookings city where the type strain was first isolated).

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of SG772T is deposited in GenBank under accession number MH127966.1. Whole genome sequences are deposited in GenBank under BioProject PRJNA436995.

Deposit in culture collection

Strain SG772T was deposited in the DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH under DSM 107275 and in the Culture Collection of Switzerland (CCOS) under CCOS 1888.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicting interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch projects SD00H532-14 and SD00R540-15, and by a grant from the South Dakota Governor’s Office of Economic Development awarded to JS.

References

- 1.Costea P.I., Hildebrand F., Arumugam M., Backhed F., Blaser M.J., Bushman F.D. Enterotypes in the landscape of gut microbial community composition. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(1):8–16. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagier J.C., Khelaifia S., Alou M.T., Ndongo S., Dione N., Hugon P. Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16203. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun J., Lee J.H., Jung Y., Kim M., Kim S., Kim B.K. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(Pt 10):2259–2261. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(8):1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyatt D., Chen G.L., Locascio P.F., Land M.L., Larimer F.W., Hauser L.J. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laslett D., Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(1):11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee I., Ouk Kim Y., Park S.C., Chun J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66(2):1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramasamy D., Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Padhmanabhan R., Rossi M., Sentausa E. A polyphasic strategy incorporating genomic data for the taxonomic description of novel bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(Pt 2):384–391. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S.K., Kim M.S., Roh S.W., Bae J.W. Blautia stercoris sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62(Pt 4):776–779. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.031625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezaki T., Li N., Hashimoto Y., Miura H., Yamamoto H. 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of anaerobic cocci and proposal of Ruminococcus hansenii comb. nov. and Ruminococcus productus comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44(1):130–136. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C., Finegold S.M., Song Y., Lawson P.A. Reclassification of Clostridium coccoides, Ruminococcus hansenii, Ruminococcus hydrogenotrophicus, Ruminococcus luti, Ruminococcus productus and Ruminococcus schinkii as Blautia coccoides gen. nov., comb. nov., Blautia hansenii comb. nov., Blautia hydrogenotrophica comb. nov., Blautia luti comb. nov., Blautia producta comb. nov., Blautia schinkii comb. nov. and description of Blautia wexlerae sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58(Pt 8):1896–1902. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S.K., Kim M.S., Bae J.W. Blautia faecis sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63(Pt 2):599–603. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.036541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieu-Lesme F., Morvan B., Collins M.D., Fonty G., Willems A. A new H2/CO2-using acetogenic bacterium from the rumen: description of Ruminococcus schinkii sp. nov. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140(2–3):281–286. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(96)00195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmering R., Taras D., Schwiertz A., Le Blay G., Gruhl B., Lawson P.A. Ruminococcus luti sp. nov., isolated from a human faecal sample. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2002;25(2):189–193. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson P.A., Finegold S.M. Reclassification of Ruminococcus obeum as Blautia obeum comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65(Pt 3):789–793. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]