Introduction

The eye forms an integral part of our identity. However, they maybe removed due to specific indication: ocular tumours, irreparably damaged and painful globes or severe ocular infections. The loss of an eye can cause more anguish than simply the loss of vision, it can also affect our confidence, mental health and our quality of life [1].

Evidence indicates that patients living with anophthalmia have lower health-related quality of life scores. Patients own perceptions of their social relationships are negatively affected and they have been shown to suffer from anxiety and depression [2].

We evaluated the emotional and psychosocial well being of patients that had undergone either enucleation or evisceration to identify whether further emotional support or counselling would be beneficial.

Method

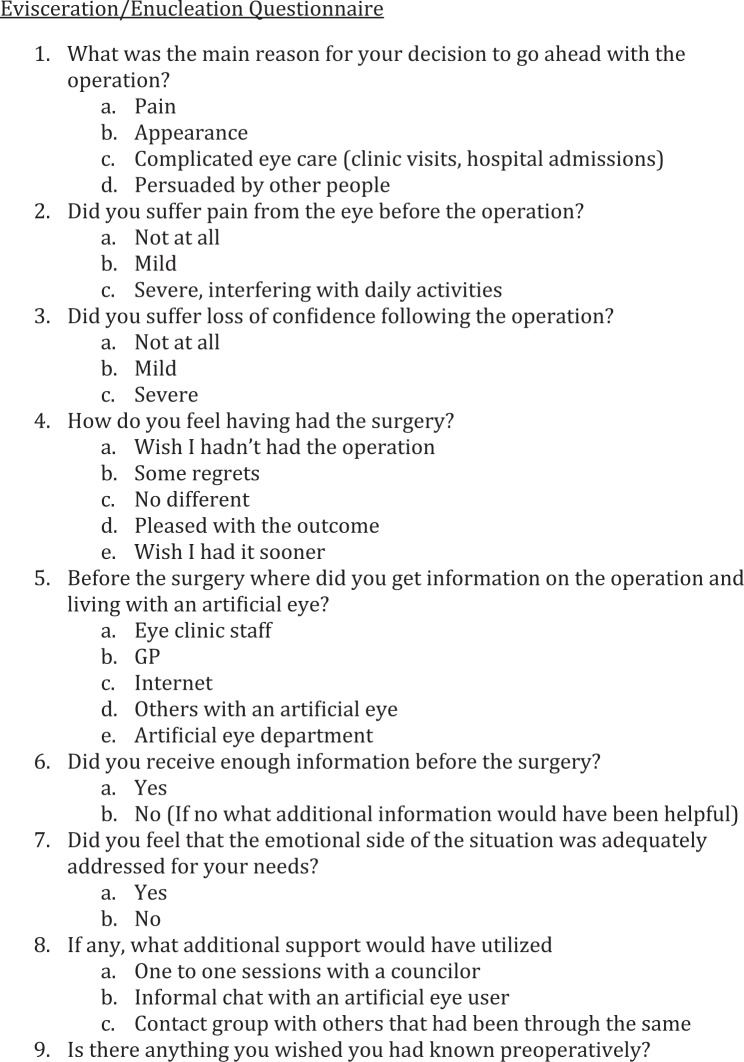

All patients over the age of 18 that had undergone either an evisceration or enucleation performed at the Princess Alexandra Eye Pavilion, Edinburgh between 1 January 2011 and 1 January 2018 were identified. Theatre online coding systems allowed us to identify the selected cohort. A telephone questionnaire (Fig. 1) was then conducted.

Fig. 1.

Evisceration/enucleation telephone interview sheet

Results

Fifty two patients had undergone either enucleation or evisceration. Thirty nine patients were still living. We attempted to contact all 39 patients and received 25 responses (64%).

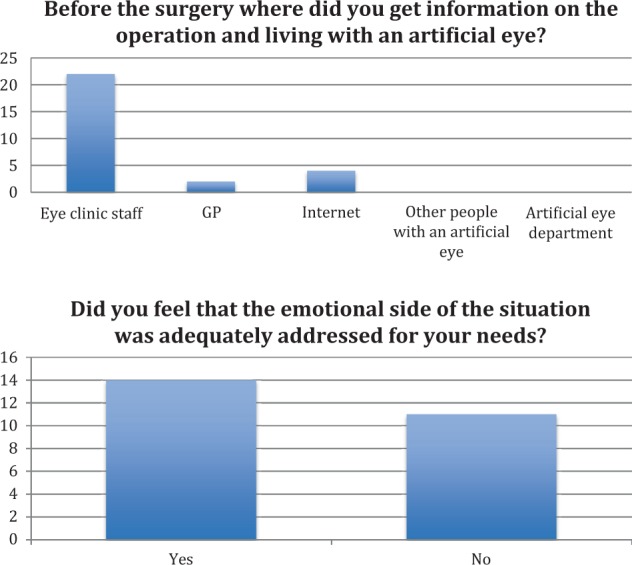

Pain was identified as the overwhelming reason that patients underwent the operation (68%) with more than half of our participants stating that preoperative pain was severe and interfering with daily activities. About 40% of patients indicated a loss of confidence as a result of the surgery, and a lack of emotional support was cited in 44% of patients (Fig. 2). One to one counselling sessions were stated as the most desired from of support both pre and postoperatively.

Fig. 2.

Graphs showing confidence loss post surgery and adequately addressed emotional needs

Discussion

Pain is the predominant cause for most patients undergoing eye removal. Between 30% and 50% of patients suffering from chronic pain also struggle with depression and anxiety [3], therefore preoperatively we are already dealing with a cohort of people who are more likely to suffer from mental health illness.

Our study indicated that patients wanted to know more about the operation: the outcome, cosmesis and how the prosthesis will look and fit. As nearly half of patients requested more emotional support both pre and postoperatively it seems they were not adequately prepared for what was to come.

Anophthalmic patients have poorer health-related quality of life, poorer self-rated health and more perceived stress than the general population. In particular quality of life was limited by emotional problems and mental health disorders [4]. As mental illness remains the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide [5] and the socioeconomic impact of depression on the UK alone has been estimated annually at over £7 billion [6], it is vital that we consider the emotional and psychosocial needs of our patients.

Conclusion

Loss of an eye and the use of artificial eyes have wide ranging emotional and psychosocial impact on patients. Care should not stop when the patient leaves the operating theatre. To maximise postoperative quality of life, a holistic approach, involving counsellors and psychotherapy is essential.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdulkabir AA. Emotional, psychosocial and economic aspects of anophthalmos and artificial eye use. Int J Ophthal Vis Sci. 2008;7:1–7.

- 2.Ahn Jm LS, Yoon JS. Health-related quality of life and emotional status of anophthalmic patients in Korea. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:1005–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbain DGM, Meagher R, et al. Male and femal chronic pain patients categorized by DSM-II psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Pain. 1986;26:18–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen ML. The eye amputated—consequences of eye amputation with emphasis on clinical aspects, phantom eye syndrome and quality of life. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardino VKM. Counselling and psychotherapy: is there an economic case for psychological interventions? London, UK: British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy; 2013.