Abstract

Acyclic contiguous stereocenters are frequently seen in biologically active natural and synthetic molecules. Although various synthetic methods have been reported, predictable and unified approaches to all possible stereoisomers are rare, particularly for those containing non-reactive hydrocarbon substituents. Herein, a β-boronyl group is employed as a readily accessible handle for predictable α-functionalization of enolates with either syn or anti selectivity depending on reaction conditions. Contiguous tertiary-tertiary and tertiary-quaternary stereocenters are thus accessed in generally good yields and diastereoselectivity. Based on experimental and computational studies, mechanism for syn selective alkylation is proposed, and Bpin (pinacolatoboronyl) behaves as a smaller group than most carbon-centered groups. The synthetic utility of this methodology is demonstrated by preparation of several key intermediates for bioactive molecules.

Subject terms: Reaction mechanisms, Stereochemistry, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Predictable and unified approaches to all possible stereoisomers of acyclic compounds with contiguous stereocentres are rare. Here, the authors disclose a divergent α-functionalization of enolates with either syn or anti selectivity employing a β-boronyl group as a small, directing handle.

Introduction

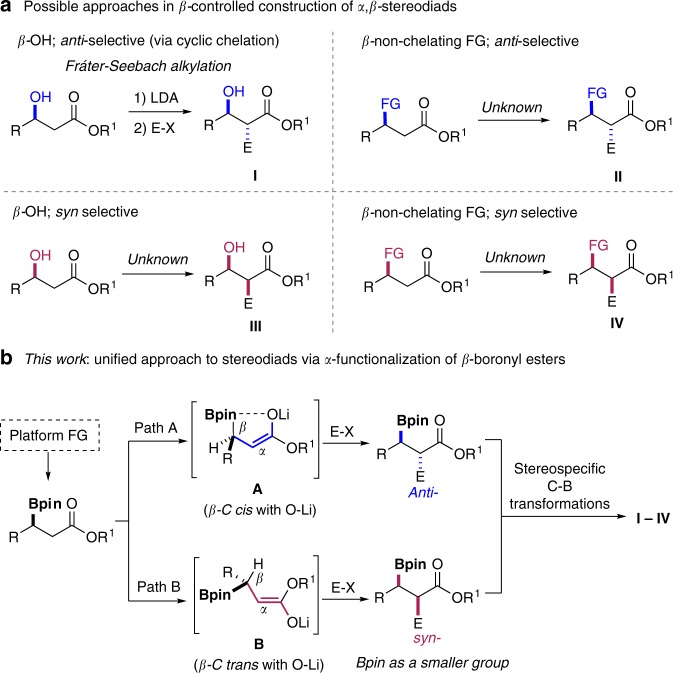

Introduction of substituents with predictable stereoselectivity is crucial for rational synthetic design of functional molecules. Despite the already advanced toolbox for practitioners of synthetic chemistry, it is still challenging to access any and every stereoisomer of contiguous acyclic stereodiads in a predictable fashion, particularly for substrates that contain only hydrocarbon groups1–5. For example, electrophilic α alkylation of an enolate is one of the most fundamental textbook transformation.6 A venerable variant, Fráter–Seebach alkylation, can reliably produce the desired product with anti-selectivity (I) starting from β-hydroxyl carboxylate (Fig. 1a)7–9. A cyclic lithium enolate intermediate involving chelation of the β-alkoxide anion is the key stereo-controlling factor. This method has been extensively employed in syntheses of polyketides and other natural products10,11. However, the syn-product III could not be obtained in similar vein (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, when the β-substituent is a non-chelating group, usually no stereocontrol could be achieved (Fig. 1a, for II and IV). Even in the extreme cases where R1 could be a chiral auxiliary, it is still challenging to access both diastereomers (II and IV). Therefore, a unified approach for predictable construction of syn- and/or anti-stereodiads would be highly desirable yet, to the best of our knowledge, has remained elusive.

Fig. 1. β-Controlled α-alkylation of carbonyl compounds.

a Possible strategies in β-controlled construction of contiguous α,β-stereodiads. b Boronyl group-controlled unified approach to stereodiads via α-functionalization of β-boronyl esters.

Considering that a boronyl group may be readily introduced by recent catalytic asymmetric borylation reactions12–17 and could serve as a platform to access other functional groups in a stereospecific fashion18–26, we hope to develop a stereodivergent α-functionalizations of β-boronyl carbonyls with predictable diastereoselectivity employing the unique role of boronyl group (Fig. 1b). The resulting acyclic compounds bearing contiguous tertiary–tertiary or even tertiary–quaternary stereogenic centers should have great value in syntheses of natural products and pharmaceuticals27–30.

In the past few years, a number of catalytic approaches to boronyl-containing 1,2-stereodiads have been reported by Miura, Ito, Liao, Brown, and other groups31–44. However, usually only one diastereomer rather than the other is preferred, and development of general and reliable methodologies for obtaining all possible stereoisomers of β-boron carbonyls remains highly challenging45–50. The Ito group51 and the Zhong group52 have independently reported diastereoselective borylative alkylation of α,β-unsaturated esters. However, the enantioselective variant has not been accomplished.

Herein, we wish to disclose our results in developing a practical and general, β-boronyl and conditions-controlled approach for divergent synthesis of both syn and anti-products containing contiguous tertiary–tertiary and tertiary–quaternary stereodiads (Fig. 1b). Upon deprotonation, a cis-enolate (path A) or a trans enolate (path B) may be selectively generated. In the cis case, due to the Lewis acidic property of sp2 boron atom, by invoking a five-membered chelation mode A, the anti-selectivity could be realized because the electrophile should attack from the less-hindered face of A (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, if the deprotonation follows an Ireland model53,54, an open-chain trans intermediate B could be formed. 1,3-Allylic strain would induce a relatively fixed conformation and the facial selectivity of alkylation should be dictated by the relative size difference of the Bpin and R group (Fig. 1b, path B). Pleasingly, we discover that in all cases, the Bpin group behaves uniquely as a smaller group than R, and therefore the syn-product is generally favored.

Results

Reaction optimization

We commenced the study by investigating the model reaction between β-boronyl esters 1a and allyl bromide 2. Simple treatment of a solution of 1a in THF with LDA (lithium diisopropylamide) followed by addition of 2 at −78 °C led to a mixture of diastereomers favoring syn-4a in 65% overall yield (anti/syn = 1:2.4, Table 1, entry 1). The relative configurations could be confirmed by transformation of the boronates to the corresponding alcohols. Although toluene was not an effective solvent for this reaction, a mixed solvents (THF/toluene = 1:1 v/v) could slightly improve the diastereoselectivity (anti/syn = 1:3.9, Table 1, entry 3). In contrast, when hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) was used as an additive, the anti-product 3a was obtained with excellent diastereoselectivity (anti/syn > 20:1, Table 1, entry 4), albeit in low yield (33%). Further, a modification of the ethyl ester 1a to 3-pentyl ester 1b markedly enhanced the syn-selectivity (Table 1, entry 5, 77% yield, anti/syn = 1:10). A slightly higher syn-selectivity was achieved when some more toluene cosolvent was used (THF/toluene 1:1.5 v/v, Table 1, entry 6). The best conditions for anti-product 3 was obtained when tert-butyl ester 1c was employed (Table 1, entry 9, 75% yield, anti/syn > 20:1).

Table 1.

Condition optimization for the allylation of β-boronyl estersa.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | 1 | Solvent | Additive | Yield (3 + 4) (%) | d.r. (3/4) |

| 1 | 1a | THF | none | 65 | 1:2.4 |

| 2 | 1a | Toluene | none | 0 | – |

| 3 | 1a | THF/Toluene (1:1) | none | 69 | 1:3.9 |

| 4 | 1a | THF | HMPA | 33 | > 20:1 |

| 5 | 1b | THF/Toluene (1:1) | none | 77 | 1:10 |

| 6 | 1b | THF/Toluene (1:1.5) | none | 77 | 1:11.8 |

| 7 | 1b | THF | HMPA | 50 | > 20:1 |

| 8 | 1c | THF/Toluene (1:1) | none | 75 | 1:3.5 |

| 9 | 1c | THF | HMPA | 75 | > 20:1 |

aReaction conditions: 1 (0.25 mmol), 2 (1.5 equiv), LDA (1.1 equiv), HMPA (0.2 mL, if used) in 1 mL of solvent at −78 °C for 12 h. Yields and diastereoselectivities were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Substrate scope

With optimal reaction conditions established, we explored the scope of these reactions. We found that the diastereodivergent reaction was successfully performed on a 2.0 mmol scale with little effects on the yield and selectivity (Figs. 2, 3c, 4b). As shown in Fig. 2, a variety of β-boronyl esters and electrophiles participated in these transformations in good to excellent yields with consistent diastereoselectivity for both syn and anti-products. For example, halide substituents on the aryl ring were well compatible in the reaction conditions (7a–7c for anti and 8a–8c for syn-products). The aromatic ring containing methoxy or trifluoromethoxy group proved to be competent reaction partners (7d, 7e, 8d, 8e). It is noteworthy that, substrates with sterically demanding groups furnished the syn-products with higher diastereoselectivity when compared with the phenyl group (8f, 8g versus 4b), which were consistent with our observation that Bpin served as the smaller group. The substrate bearing 2-thiophene furnished the syn-product with lower diastereoselectivity (8h, 62% yield, anti/syn = 1:2.5). This could be understood because the steric hindrance of 2-thiophenyl group should be smaller than phenyl group. Nevertheless, the anti-product 7 h was obtained with high diastereoselectivity. We next examined the viability of substrates with aliphatic substituents. To our surprise, the syn-product 8i could still be obtained with moderate selectivity (anti/syn = 1:3.8), which means that Bpin behaves as a smaller group even than methyl group. As expected, the more bulkier alkyl group was employed, the higher syn-selectivity could be achieved (8j–8n). These results all pointed that Bpin acted as a smaller group in this transformation. In parallel, these β-boronyl esters containing aliphatic substituents successfully furnished the anti-products 7i–7n with excellent diastereoselectivity. In addition, alkenyl-substituted β-boronyl esters also participated in this reaction and generated the corresponding products 7o–7p and 8o–8p with selectivity of same trend.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of the diastereodivergent α-functionalization of β-boronyl carbonyl compounds.

Reaction conditions: unless otherwise noted, the reactions were performed at 0.25 mmol scale with 1.5 equiv allyl bromide, 1.1 equiv LDA, and 0.2 mL HMPA (if used). Isolated yields shown. D.r. values determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude poducts. aIodomethane as the electrophile. bBenzyl bromide as the electrophile. cCinnamyl bromide as the electrophile. dBenzylchloromethyl ether as the electrophile. e3-Bromo-1-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propyne as the electrophile. fDiphenyl disulfide as the electrophile.

Fig. 3. Calculated free energy profiles for the α-alkylation of carbonyl compounds (R1 = 3-pentyl).

The favored pathway is labeled by solid lines. The values given in kcal/mol are the relative free energies calculated by the M06-2X/6-311 + G(d,p)//B3LYP/6-31 G(d) method in THF solvent.

Fig. 4. Optimized structures at nucleophilic substitution steps.

a Transition state of 9-ts and 11-ts. b Transition state of 9-ts-Me and 11-ts-Me. (R1 = 3-pentyl).

We also examined the scope with respect to other electrophiles. Beyond allyl substituent, methyl, benzyl, cinnamyl, benzyloxymethyl, and propargyl groups could also be installed to the β-boronyl esters with high selectivity for both syn and anti-products (7q–7u and 8q–8u). Besides alkyls, the phenylthio group could also be introduced to the α-position of β-boronyl esters with excellent diastereoselectivity when diphenyl disulfide was employed as the electrophile (7v, 8v). Finally, we tested similar alkylation of β-boronyl amides. However, only anti-products could be accessed under either set of conditions (7w–7x), probably because of the severe steric interaction between NEt2 and β-carbon in the Ireland model, leading to exclusive formation of cis-enolate55.

Mechanistic origins of the syn-selectivity

Density functional M06-2X56 with a standard 6-311 + G(d,p) basis set was employed to gain further insight into the diastereodivergent alkylation reactions, paticularly the general syn-selective outcome. In our theoretical calculations, the β-boryl ester 1 and allyl bromide 2 were chosen as reactants in model reaction, which can give syn-product 4b in experimental observations (Fig. 3). As depicted in Fig. 3, ligand exchange between solvent-coordinated LDA C-3 and β-boryl ester 1 forms O-coordinated complex C-4 in an endothermic process with 4.0 kcal/mol free energy, which can attribute to the weak coordination ability of ester. In complex C-4, the coordination onto lithium significantly increased the ester’s α-acidity. Subsequently, amino-assisted deprotonation of ester’s α-hydrogen can smoothly occur via either six-membered ring transition state 5-ts or 7-ts. The calculated relative free energy of 7-ts is 1.3 kcal/mol higher than that of 5-ts, indicating that the generation of open-chain enolate C-6 is favorable with 13.6 kcal/mol exergonic. The energy difference between transition states 5-ts and 7-ts can be attributed to the position of bulky boronylbenzyl group, which is located at the axial position in 7-ts. In this case, 1,3-allylic strain resulted in a lowest energy conformation, where the β-proton and the bulky ester group OR1 of enolate C-6 are cis to each other and nearly coplanar57. The subsequent intermolecular nucleophilic substitution by enolate C-6 with allyl bromide 2 could occur through two different transition states owing to the chiral environment of β-C in enolate C-6. The intermolecular nucleophilic substitution by the si-face of enolate C-6 onto the allyl bromide 2 could occur via linear transition state 9-ts, which leads to the generation of syn-product 4b from intermediate C-10. On the contrary, the anti-isomer might be obtained via transition state 11-ts, where the nucleophilic substitution could take place by the re-face of enolate C-6. The calculated energy barrier of transition state 11-ts is 12.9 kcal/mol, which is 1.9 kcal/mol higher than that of 9-ts. Therefore, the computational study depicted that the syn-4b should be the major product, which is consistent with experimental observations. As shown in Fig. 4a, optimized structure analysis shows that the main difference between 9-ts and 11-ts is the conformation of the α- and β-carbon atoms. To the satisfaction of the minimum steric repulsion of coming allyl bromide in nucleophilic substitution, the β-phenyl group and α-hydrogen adopt an eclipsed conformation in higher free energy transition state 11-ts, while, the β-boryl and α-hydrogen are eclipsed in transition state 9-ts. The phenyl group is larger than that of boryl group, which causes larger steric repulsion between eclipsed β-phenyl group and α-hydrogen in transition state 11-ts. Based on the aforementioned theoretical results, we hypothesized when the bulky phenyl group is masked by a smaller methyl group, poor diastereoselectivity will be observed in the experiment. As shown in Fig. 4b, in the nucleophilic substitution step, the calculated relative free energy of the re-face attack transition state 11-ts-Me is only 0.4 kcal/mol higher than that of si-face attack transition state 9-ts-Me. The theoretically calculated diastereoselectivity value for the methyl masked reaction would decrease to 2.8:1, which is consistent with the experimental observation value (3.8:1). Although the Bpin group contains a five-membered heterocycle and a bulky pinacol moiety, its planar structure combined with substituent-free oxygen atoms might render it a less sterically demanding structural unit than common carbon-centered groups. In a recent report, Tillin et al. also noted smaller size effect of Bpin in comparison with groups such as cyclohexyl58.

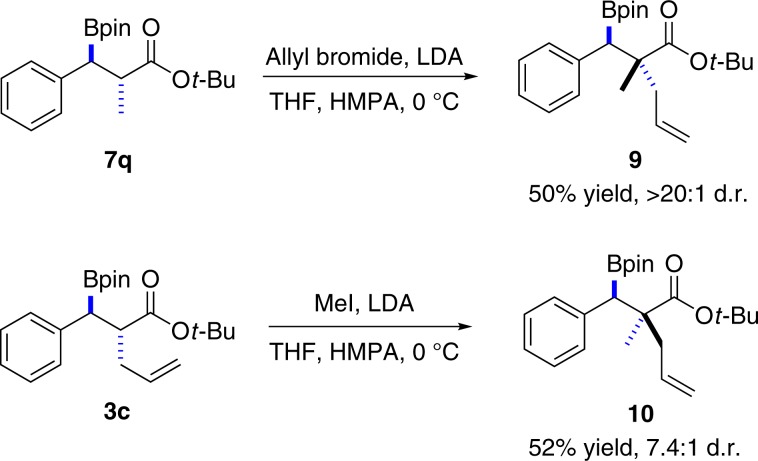

Construction of tertiary–quaternary stereodiads

The construction of quaternary carbon stereocenters, especially in an open-chain molecule, is usually a challenge in synthetic chemistry59. Encouraged by the above results, we proceeded with a second α-alkylation of the obtained products 7q and 3c under the standard anti-selective conditions. Pleasingly, the tertiary–quaternary diastereoisomers 9 and 10 were obtained with high stereoselectivity (Fig. 5). Therefore, all diastereoisomers of the tertiary–quaternary stereocenters could be obtained by simply changing the sequence of α-alkylation. In combination with the well-established enantioselective 1,4-borylation methods12–17, all possible stereoisomers could be accessed in such an approach.

Fig. 5. Construction of tertiary–quaternary stereocenters.

Preparation of the diastereoisomers 9 and 10.

Stereospecific C-B transformations

To exemplify the versatility of this methodology in building contiguous stereodiads, we converted the organoboronic acid derivatives into other classes of compounds by using established methods (Fig. 6). For example, the diastereoisomeric diols 11 and 12 could be accessed easily by an oxidation–reduction sequence from 3c and 4b, respectively. Moreover, the hydroxymethylated product 13 could be prepared by using the in situ formed LiCH2Cl and subsequent oxidation with NaBO360. Furthermore, the coupling of 2-lithiofuran with boronic ester 4b gave the arylated product 14 in high yield with complete stereoretention by using the protocol developed by the Aggarwal group61. Similarly, other heterocycles such as indole and furan groups could be installed without erosion in diastereomeric ratio. These 1,1-diaryl compounds are important pharmacophores, and their stereocontrolled preparation have been challenging through traditional protocols62–65.

Fig. 6. Products Transformations.

Transformations of the boronic ester to alcohols (11 and 12), hydroxymethyl (13), and heterocycles (14, 15, and 16).

In our previous work, the cis-diol 19, a key intermediate of carbocyclic nucleosides66, was successfully employed for total synthesis of prostratin, a potent anti-HIV and antitumor natural product67. The trans-diol 22 is also an important synthetic intermediate of carbocyclic analogs of the antiviral ribavirin68. Evans aldol reaction was previously used for the synthesis of these diols. However, the use of stoichiometric amounts of chiral auxiliaries, excess expensive and sensitive Lewis acid n-Bu2BOTf limited the synthetic efficiency. Herein, based on the current approach, unified catalytic enantioselective syntheses of cis-diol 19 and trans-diol 22 can be achieved using inexpensive chmicals (Fig. 7). Optically pure 5o was obtained through Cu-catalyzed enantioselective 1,4-borylation of the sorbic acid-derived ester69,70. Diastereoselective α-allylation of chiral 5o with standard conditions and subsequent oxidation with NaBO3 furnished 17 and 20 in good yields. The cis-diol 19 and trans-diol 22 were then obtained by ring-closing olefin metathesis of 17 and 20 followed by reduction with LiAlH4, respectively.

Fig. 7. Synthetic utility of the divergent methodology.

Unified enantioselective synthesis of cis and trans diols 19 and 22.

In conclusion, we have developed a predictable and unified protocol for both syn and anti diastereoselective α-functionalization of readily available β-boronyl carbonyls. The key to success was the exploitation of the dual roles of Bpin: its apparently small size and its Lewis acidic character. The structural predictability, operational simplicity, and broad substrate scope in combination with the versatile role of Bpin in synthetic transformations should render the method useful in preparation of contiguous diads, which are present in many types of biologically active molecules yet difficult to access by conventional approaches. The surprising size effect of a boronyl group may well be used in other parts of organoboron chemistry.

Methods

General procedure for anti α-functionalized-β-boronyl esters

A solution of diisopropylamine (0.275 mmol, 38.5 µL) in THF (0.5 mL) was cooled to 0 °C and treated with n-BuLi (110 µL, 2.5 M in hexane) dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min and cooled to −78 °C. To the freshly prepared solution of LDA, a solution was added of β-boronyl ester (0.25 mmol) in THF/HMPA (0.5 ml/0.2 ml) dropwise over 2 min. After stirring at the same temperature for 3 h, the electrophile (0.375 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture dropwise over 1 min and stirred for 8 h. Then the reaction was quenched with saturated aq. NH4Cl solution (1.0 mL) and diluted with DCM (5.0 mL). The layers were separated, the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (2 × 5.0 mL), the combined organic phases were washed with water and brine, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography to yield the desired anti-product.

General procedure for syn α-functionalized-β-boronyl esters

A solution of diisopropylamine (0.275 mmol, 38.5 µL) in toluene (0.6 mL) was cooled to 0 °C and treated with n-BuLi (110 µL, 2.5 M in hexane) dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min and cooled to −78 °C. To the freshly prepared solution of LDA, a solution was added of β-boronyl ester (0.25 mmol) in THF (0.4 mL) dropwise over 2 min. After stirring at the same temperature for 15 min, the electrophile (0.375 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture dropwise over 1 min and stirred for 8 h. Then the reaction was quenched with saturated aq. NH4Cl solution (1.0 mL) and diluted with DCM (5.0 mL). The layers were separated, the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (2 × 5.0 mL), the combined organic phases were washed with water and brine, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography to yield the desired syn-product.

Spectroscopic methods

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometers. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on a WATERS I-Class VION IMS QTof spectrometer. Enantiomeric excesses (ee) were determined by chiral HPLC analysis using Waters 2489 Series chromatographs using a mixture of HPLC-grade hexane and isopropanol as eluent.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21672168, 21971202, 21702157, 21822303, and 21772020), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2019M653581 and 2017M623148), National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX201600122) and Key Laboratory Construction Program of Xi’an Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (201805056ZD7CG40). P.L. is a “Chung Ying Schlolar” of Xi’an Jiaotong University. The authors thank Ms. A. Lu at the Instrument Analysis Center of XJTU for the assistance with high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis.

Author contributions

P.L. and M.Z. conceptualized and designed the project. M.Z., Z.D., S.D., M.X., Z.L. and M.Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the results. H.C., C.F., C.W. and Y.L. performed the DFT calculations. M.Z., S.D., H.C., Y.L. and P.L. wrote the paper. M.Z., Z.D. and S.D. contributed equally.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Hua-Dong Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu Lan, Email: lanyu@cqu.edu.cn.

Pengfei Li, Email: lipengfei@xjtu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-14592-7.

References

- 1.Krautwald S, Sarlah D, Schafroth MA, Carreira EM. Enantio- and diastereodivergent dual catalysis: α-allylation of branched aldehydes. Science. 2013;340:1065–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1237068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi S-L, Wong ZL, Buchwald SL. Copper-catalysed enantioselective stereodivergent synthesis of amino alcohols. Nature. 2016;532:353–356. doi: 10.1038/nature17191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaldre D, Klose I, Maulide N. Stereodivergent synthesis of 1,4-dicarbonyls by traceless charge–accelerated sulfonium rearrangement. Science. 2018;361:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trost BM, Hung C-I, Saget T, Gnanamani E. Branched aldehydes as linchpins for the enantioselective and stereodivergent synthesis of 1,3-aminoalcohols featuring a quaternary stereocentre. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:523–530. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0093-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruffaerts J, Pierrot D, Marek I. Efficient and stereodivergent synthesis of unsaturated acyclic fragments bearing contiguous stereogenic elements. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:1164–1170. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey, F. A. & Sundberg, R. J. Alkylation of Enolates and Other Carbon Nucleophiles. In: Carey, F. A. & Sundberg, R. J. (eds) Advanced organic chemistry, part B: reactions and synthesis, 5th edn, 1–62 (Springer, New York, 2007).

- 7.Fráter G. Über die stereospezifität der α-alkylierung von β-hydroxycarbonsäureestern. Vorläufige Mitteilung. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1979;62:2825–2828. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19790620832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seebach D, Wasmuth D. Herstellung von erythro-2-hydroxybernsteinsäure-derivaten aus äpfelsäureester. vorläufige mitteilung. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1980;63:197–200. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19800630118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, J. J. Frater–Seebach alkylation. In: Li, J. J. (ed.) Name reactions: a collection of detailed reaction mechanisms, 2nd edn, 127 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg GmbH, New York, 2003).

- 10.Barth R, Mulzer J. Total synthesis of efomycine M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5791–5794. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crimmins MT, O’Bryan EA. Enantioselective total synthesis of spirofungins A and B. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4416–4419. doi: 10.1021/ol101961c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J-E, Yun J. Catalytic asymmetric boration of acyclic α,β-unsaturated esters and nitriles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:145–147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng K, Liu X, Feng X. Recent advances in metal-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-conjugate addition (ACA) of nonorganometallic nucleophiles. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:7586–7656. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornillos V, Vila C, Otten E, Feringa BL. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of phosphine boronates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:7867–7871. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Brien JM, Lee K-s, Hoveyda AH. Enantioselective synthesis of boron-substituted quaternary carbons by NHC−Cu-catalyzed boronate conjugate additions to unsaturated carboxylic esters, ketones, or thioesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10630–10633. doi: 10.1021/ja104777u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L, Kitanosono T, Xu P, Kobayashi S. A Cu(II)-based strategy for catalytic enantioselective β-borylation of α,β-unsaturated acceptors. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11685–11688. doi: 10.1039/C5CC04295J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H, Radomkit S, O’Brien JM, Hoveyda AH. Metal-free catalytic enantioselective C–B bond formation: (pinacolato)boron conjugate additions to α,β-unsaturated ketones, esters, weinreb amides, and aldehydes promoted by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8277–8285. doi: 10.1021/ja302929d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandford C, Aggarwal VK. Stereospecific functionalizations and transformations of secondary and tertiary boronic esters. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:5481–5494. doi: 10.1039/C7CC01254C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Ruiz C, et al. Stereospecific allylic functionalization: the reactions of allylboronate complexes with electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:15324–15327. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rygus JPG, Crudden CM. Enantiospecific and iterative Suzuki–Miyaura cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:18124–18137. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao S, et al. Enantiodivergent Pd-catalyzed C–C bond formation enabled through ligand parameterization. Science. 2018;362:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding S, Xu L, Li P. Copper-catalyzed boron-selective C(sp2)–C(sp3) oxidative cross-coupling of arylboronic acids and alkyltrifluoroborates involving a single-electron transmetalation process. ACS Catal. 2016;6:1329–1333. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b02524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang G, et al. N,B-bidentate boryl ligand-supported iridium catalyst for efficient functional-group-directed C–H borylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:91–94. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Zhang S, Li P. Boron-selective reactions as powerful tools for modular synthesis of diverse complex molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:8848–8858. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00338E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fyfe JWB, Watson AJB. Recent developments in organoboron chemistry: old dogs, new tricks. Chem. 2017;3:31–55. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonori D, Aggarwal VK. Lithiation–borylation methodology and its application in synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3174–3183. doi: 10.1021/ar5002473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surleraux DLNG, et al. Discovery and selection of TMC114, a next generation HIV-1 protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1813–1822. doi: 10.1021/jm049560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi M, et al. Bioorganic synthesis and absolute configuration of faranal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6602–6604. doi: 10.1021/ja00541a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujisawa T, et al. Highly water-soluble matrix metalloproteinases inhibitors and their effects in a rat adjuvant-induced arthritis model. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:2569–2581. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzschentke TM, et al. (–)-(1R, 2R)-3-(3-Dimethylamino-1-ethyl-2-methyl-propyl)-phenol hydrochloride (tapentadol HCl): a novel μ-opioid receptor agonist/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with broad-spectrum analgesic properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323:265–276. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.126052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda N, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Regioselective and stereospecific copper-catalyzed aminoboration of styrenes with bis(pinacolato)diboron and O-benzoyl-N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4934–4937. doi: 10.1021/ja4007645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubota K, Watanabe Y, Hayama K, Ito H. Enantioselective synthesis of chiral piperidines via the stepwise dearomatization/borylation of pyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4338–4341. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L, et al. Highly diastereo- and enantioselective Cu-catalyzed borylative coupling of 1,3-dienes and aldimines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:13854–13858. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logan KM, Sardini SR, White SD, Brown MK. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective arylboration of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:159–162. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itoh T, Kanzaki Y, Shimizu Y, Kanai M. Copper(I)-catalyzed enantio- and diastereodivergent borylative coupling of styrenes and imines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57:8265–8269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201804117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan JB, Miller SP, Morken JP. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective diboration of simple alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8702–8703. doi: 10.1021/ja035851w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng F, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH. Diastereo- and enantioselective reactions of bis(pinacolato)diboron, 1,3-enynes, and aldehydes catalyzed by an easily accessible bisphosphine–Cu complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11304–11307. doi: 10.1021/ja5071202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logan KM, Smith KB, Brown MK. Copper/palladium synergistic catalysis for the syn- and anti-selective carboboration of alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:5228–5231. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato K, Hirano K, Miura M. Synthesis of β-boryl-α-aminosilanes by copper-catalyzed aminoboration of vinylsilanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:14400–14404. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito H, Horita Y, Yamamoto E. Potassium tert-butoxide-mediated regioselective silaboration of aromatic alkenes. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:8006–8008. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32778c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Z, Li X, Zeng T, Engle KM. Directed, palladium(II)-catalyzed enantioselective anti-carboboration of alkenyl carbonyl compounds. ACS Catal. 2019;9:3260–3265. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng J-J, Oestreich M. Tertiary α-silyl alcohols by diastereoselective coupling of 1,3-dienes and acylsilanes initiated by enantioselective copper-catalyzed borylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:8211–8215. doi: 10.1002/anie.201903174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen B, Cao P, Liao Y, Wang M, Liao J. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed methylboration of alkenes. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1346–1349. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H-M, et al. Copper-catalyzed borylative cyclization of substituted N-(2-Vinylaryl)benzaldimines. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1777–1780. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Z-T, et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration of α-dehydroamino acid derivatives: facile synthesis of chiral β-hydroxy-α-amino acids. Org. Lett. 2014;16:1426–1429. doi: 10.1021/ol500219e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie J-B, Lin S, Qiao S, Li G. Asymmetric catalytic enantio- and diastereoselective boron conjugate addition reactions of α-functionalized α,β-unsaturated carbonyl substrates. Org. Lett. 2016;18:3926–3929. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lillo V, et al. Asymmetric β-boration of α,β-unsaturated esters with chiral (NHC)Cu catalysts. Organometallics. 2009;28:659–662. doi: 10.1021/om800946k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kubota K, Hayama K, Iwamoto H, Ito H. Enantioselective borylative dearomatization of indoles through copper(I) catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:8809–8813. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen L, Shen J-J, Gao Q, Xu S. Synthesis of cyclic chiral α-amino boronates by copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative borylation of indoles. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:5855–5859. doi: 10.1039/C8SC01815D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bi Y-P, et al. Stereoselective synthesis of all-cis boryl tetrahydroquinolines via copper-catalyzed regioselective addition/cyclization of o-aldiminyl cinnamate with B2Pin2. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019;17:1542–1546. doi: 10.1039/C8OB03195A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayama K, Kubota K, Iwamoto H, Ito H. Copper(I)-catalyzed diastereoselective dearomative carboborylation of indoles. Chem. Lett. 2017;46:1800–1802. doi: 10.1246/cl.170825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuo Y-J, et al. Copper-catalyzed diastereoselective synthesis of β-boryl-α-quaternary carbon carboxylic esters. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018;16:9237–9242. doi: 10.1039/C8OB02469C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ireland RE, Mueller RH, Willard AK. The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:2868–2877. doi: 10.1021/ja00426a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ireland RE, Wipf P, Armstrong JD. Stereochemical control in the ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. 1. Stereoselectivity in silyl ketene acetal formation. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:650–657. doi: 10.1021/jo00002a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie L, Isenberger KM, Held G, Dahl LM. Highly stereoselective kinetic enolate formation: steric vs electronic effects. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7516–7519. doi: 10.1021/jo971260a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008;120:215–241. doi: 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evans, D. A. Stereoselective alkylation reactions of chiral metal enolates. In Asymmetric Synthesis Vol. 3 (ed. Morrison, J. D.) 2–110 (Academic Press, Orlando, 1984).

- 58.Tillin C, et al. Complex boron-containing molecules through a 1,2-metalate rearrangement/anti-sn2′ elimination/cycloaddition reaction sequence. Synlett. 2019;30:449–453. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1610389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng J, Holmes M, Krische MJ. Acyclic quaternary carbon stereocenters via enantioselective transition metal catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:12564–12580. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen A, Ren L, Crudden CM. Catalytic asymmetric hydrocarboxylation and hydrohydroxymethylation. A two-step approach to the enantioselective functionalization of vinylarenes. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:9704–9710. doi: 10.1021/jo9914216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bonet A, Odachowski M, Leonori D, Essafi S, Aggarwal VK. Enantiospecific sp2–sp3 coupling of secondary and tertiary boronic esters. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ameen D, Snape TJ. Chiral 1,1-diaryl compounds as important pharmacophores. MedChemComm. 2013;4:893–907. doi: 10.1039/c3md00088e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caruana L, Kniep F, Johansen TK, Poulsen PH, Jørgensen KA. A new organocatalytic concept for asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15929–15932. doi: 10.1021/ja510475n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stadler D, Bach T. Highly diastereoselective Friedel–Crafts alkylation reactions via chiral α-functionalized benzylic carbocations. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:272–284. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubenbauer P, Bach T. Gold(III) chloride-catalyzed diastereoselective alkylation reactions with chiral benzylic acetates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1125–1130. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200700600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crimmins MT, King BW, Zuercher WJ, Choy AL. An efficient, general asymmetric synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides: application of an asymmetric aldol/ring-closing metathesis strategy. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:8499–8509. doi: 10.1021/jo005535p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tong G, Liu Z, Li P. Total synthesis of (±)-prostratin. Chem. 2018;4:2944–2954. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuang R, et al. Enantioselective syntheses of carbocyclic ribavirin and its analogs: linear versus convergent approaches. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9575–9579. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01704-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kitanosono T, Xu P, Kobayashi S. Heterogeneous and homogeneous chiral Cu(II) catalysis in water: enantioselective boron conjugate additions to dienones and dienoesters. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:8184–8186. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44324h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kobayashi S, Xu P, Endo T, Ueno M, Kitanosono T. Chiral copper(II)-catalyzed enantioselective boron conjugate additions to α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds in water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:12763–12766. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information file.