Abstract

The pathologist workforce in the United States is a topic of interest to the health-care community as a whole and to institutions responsible for the training of new pathologists in particular. Although a pathologist shortage has been projected, there has been a pervasive belief by medical students and their advisors that there are “no jobs in pathology.” In 2013 and again in 2017, the Program Directors Section of the Association of Pathology Chairs conducted surveys asking pathology residency directors to report the employment status of each of their residents graduating in the previous 5 years. The 2013 Program Directors Section survey indicated that 92% of those graduating in 2010 had obtained employment within 3 years, and 94% of residents graduating in 2008 obtained employment within 5 years. The 2017 survey indicated that 96% of those graduating in 2014 had obtained employment in 3 years, and 97% of residents graduating in 2012 obtained positions within 5 years. These findings are consistent with residents doing 1 or 2 years of fellowship before obtaining employment. Stratification of the data by regions of the country or by the size of the residency programs does not show large differences. The data also indicate a high percentage of employment for graduates of pathology residency programs and a stable job market over the years covered by the surveys.

Keywords: pathology employment, pathology graduates, pathology job market, pathology residency, pathology workforce

Introduction

The pathologist workforce in the United States is a topic of interest to the health-care community as a whole and to institutions responsible for the training of new pathologists in particular. Several recent studies have looked at this issue from aspects of the supply as well as the demand for new pathologists.

Robboy et al1 in 2013 developed a model of the supply of pathologists in the workforce based on analysis of 3 key determinants: (1) pathologists in the base year of the analysis (2010), stratified by sex and age; (2) additions to the pathology workforce per year after completion of training; and (3) separations from the workforce due to retirement, mortality, and other causes. The model projected that, for each of the following 20 years, the net balance would be pathologists leaving the field. They concluded that by 2030 the number of pathologists practicing full time will have dropped to about 14 000 full-time equivalent (FTE) practitioners, down from approximately 17 500 in 2010, representing a decline in the per capita ratio of pathologists from 5.7 to 3.7 per 100 000 population. The decline in the number of pathologists between 2007 and 2017 has been independently confirmed by Metter et al2 using the Association of American Medical Colleges Physician Specialty Data Books, which draw from the American Medical Association master file and which showed a decline to 3.94 pathologists per 100 000 population already by 2017.

In a follow-up study in 2015, Robboy et al3 addressed the more difficult issue of modeling the future demand for pathologist services. Consideration was given to 3 major determinants: (1) the medical services that pathologists provide and their service settings; (2) new needs, especially the drivers of new demand, such as an aging population; and (3) trends in new technologies and in new professional roles arising from pathologists’ dual expertise as physicians and providers of laboratory-based health care. If all factors stayed the same, 10% more pathologists would be needed by 2030 to sustain the current number of pathologists per 100 000 population (19 239 FTE). However, the authors consider the assumption of a simple straight-line projection to be “highly suspect” and merely a starting point for further predictions factoring in the service demands of an aging population, practice behavior, service utilization, health-care mergers, the economy, and so on.

These considerations of trends and the stability of the pathology workforce have taken place in the context of the undocumented but nevertheless pervasive belief by medical students and even their advisors that there are “no jobs in pathology.” Although undocumented, this belief is not entirely without justification. The retirement age for pathologists has been rising slowly for decades. Robboy et al1 in 2013 noted that during recent times, pathologists older than 55 years have reported their planned retirement age will rise by about 4 years from age 67 to 71 years. This trend might well have been reinforced by the negative effect of the recession of 2008 on personal finances. A similar retrenchment may have occurred, or at least may have been made more credible, by employment concerns, not only due to the general economic environment but also because of specific concerns about the future of the American health-care system.

Added to these factors was the very real event of elimination of the credentialing or “fifth” year of primary pathology training, which created the phenomenon of 2 classes of residents emerging as board-eligible simultaneously.4 The resulting overflow of graduates understandably spilled over into fellowships. To some extent, this phenomenon merely mirrored a preexisting option in which focused subspecialty training equivalent to a fellowship constituted the credentialing year itself, and elimination of 1 year of training for eligibility toward certification was not the sole factor changing the perception of how much training was needed for employment. Nevertheless, while in the 2018 American Society for Clinical Pathology Fellowship & Job Market Surveys, 96% of residents were planning to take at least one fellowship, in the 2006 survey, of the 742 respondents in the fourth year of residency or fellowship, 542 planned to apply directly for jobs; so even assuming all 104 fellows in that survey planned to apply directly for jobs, at most 31% of fourth-year residents planned to take fellowships.5 Furthermore, by 2016, in a survey by the Program Directors Section (PRODS)6 asking pathology program directors if, in general, they considered most AP/CP residents adequately prepared to enter practice after 4 years of residency training without further fellowship training, 47% indicated a concern that residents were not adequately prepared, compared to 38% who felt that residents were prepared and 18% who were neutral, although 67% of the program directors felt that their own residents were adequately prepared after 4 years.

Residents responded to these developments by doing fellowships, often more than one, and program directors recognized that employers were coming to expect the additional credential of a fellowship, whether it was truly necessary for competency or not. The data collected on graduating residents by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) Graduate Medical Education Committee for the years 2012 to 2016 documented that 91% of residency graduates responding to the survey had completed at least one fellowship (delaying their entry into the job market by at least 1 year) and 25% had completed 2 or more fellowships (delaying their entry into the job market by 2 or more years).5 Furthermore, as residents began having to make fellowship commitments earlier and earlier, typically 1½ to 2 years prior to beginning the fellowship, there was often no realistic opportunity to find a job prior to accepting a fellowship. If a job opportunity subsequently became available, the trainee was likely to find himself/herself in the uncomfortably unprofessional situation of having to abandon the prior fellowship commitment in order to secure the job. It was against this background that the PRODS formulated 2 surveys to actually document if recent graduates of pathology residency programs were finding jobs, and how soon after finishing residency they were obtaining them.

Methods

In 2013, the PRODS of the Association of Pathology Chairs (APC) approached these issues from the standpoint of graduate medical education. A survey instrument was distributed to pathology residency directors between April 8 and June 1, 2013, through an online listserv managed by the APC. The survey asked programs to identify themselves by 10-digit ACGME number and to return the number of graduates from the residency program (not fellowships) in 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012. For each of these graduating classes, the programs were asked to then return the number of those graduates who were known to have ever begun a “real” position in pathology, based on personal knowledge, receipt of credential verifications, or other sources. The term “real” job was defined in the survey as “Ever employed as a pathologist or pathology faculty (not a trainee, fellow, postdoc).”

The 2013 PRODS survey of program directors was updated and repeated between April 17 and June 7, 2017. Once again, the survey asked programs to identify themselves by ACGME number, and to return the number of graduates from the residency program (not fellowships) who were known to have ever begun a “real” position in pathology based on personal knowledge, receipt of credential verifications, or other sources, this time for graduates of the years 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. The survey was sent out to the PRODS listserv on April 17, 2017, with a reminder on May 1, 2017. On May 22 and 30, 2017, individual requests were sent to program directors before the survey was closed on June 7, 2017.

Results

In the 2013 PRODS survey, 97 responses were received. Excluding duplicates and incomplete responses, 87 programs with 1514 currently enrolled residents provided complete responses on 1802 of their graduates from 2008 through 2012. Reconciling the responding programs with the ACGME database, there were 77 programs with 882 currently enrolled residents that were not included in the tabulation of responses (either no response or an incomplete response). However, of those 77 programs, 17 were inactive and without any currently enrolled residents, despite still being listed in the ACGME database. The response rate for active programs was therefore 87/(87 + 77 − 17) or 59.2%. The response rate for representation of current residents was 1514/(1514 + 882) or 63.2%.

In the 2017 PRODS survey, 99 responses were received, three of which required clarification of inconsistent responses. There were no duplicates or incomplete responses. The 99 responding programs, representing 1704 currently enrolled residents, provided complete responses on 2065 of their graduates from 2012 through 2016. Reconciling the responding programs with the ACGME database, there were 65 programs with 654 currently enrolled residents that were not responsive. Of these 65, 23 programs in the ACGME database did not have any enrolled residents (22 closed programs plus one recently approved program that had not enrolled residents). The response rate for active programs was therefore 99/(99 + 65 − 23) or 70.2%. The responding programs represented 1704/(1704 + 654) or 72.3% of current residents.

There were thus 147 active programs in 2013, which dropped to 142 in 2017, although one of those was new and had not by then enrolled any residents. The active programs in 2013 included 2396 residents in 2013; the active programs in 2017 included 2358 residents, for a decline of 38 filled positions between the 2 survey years. The average size of all programs in 2013 was 16.3 residents; the average size of those responding was 17.4. The average size of all programs in 2017 was 16.7, and the average size of those responding was 17.2.

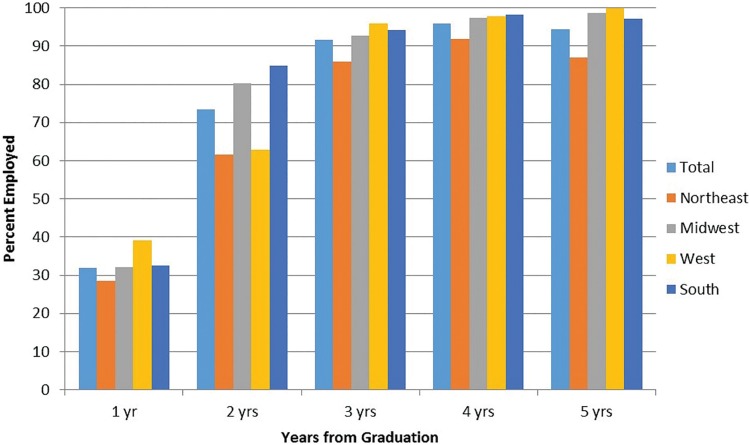

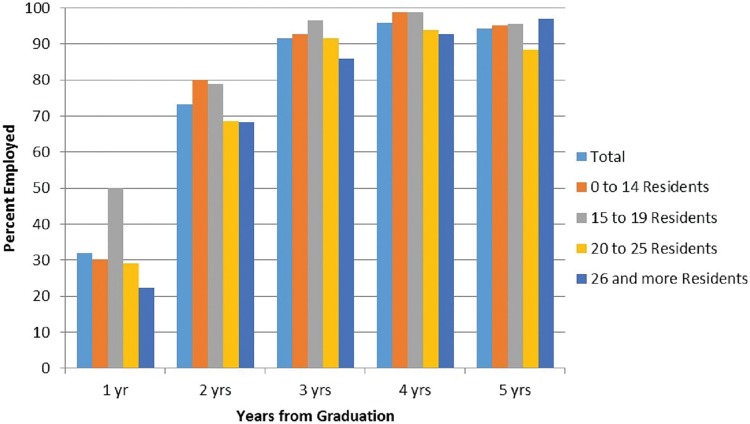

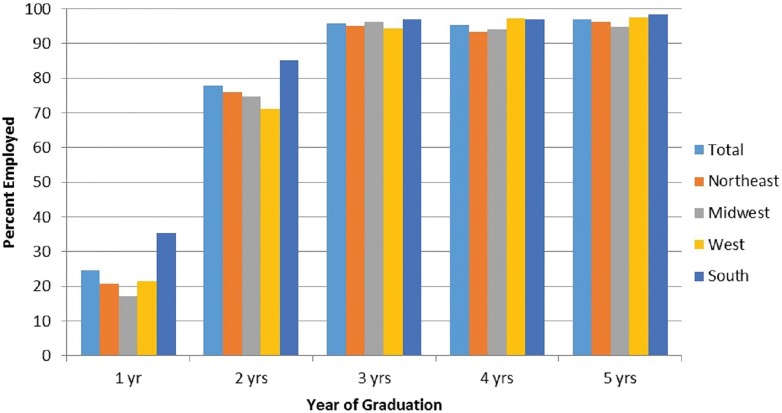

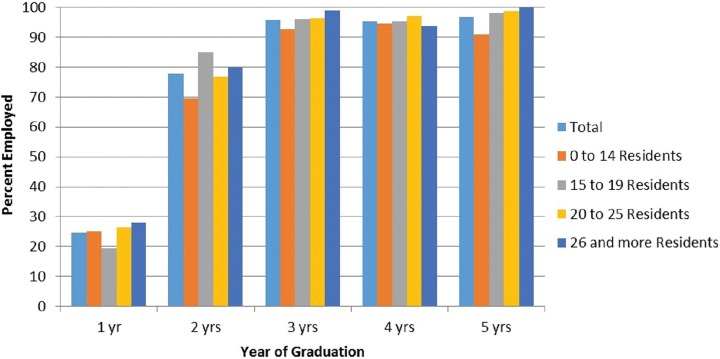

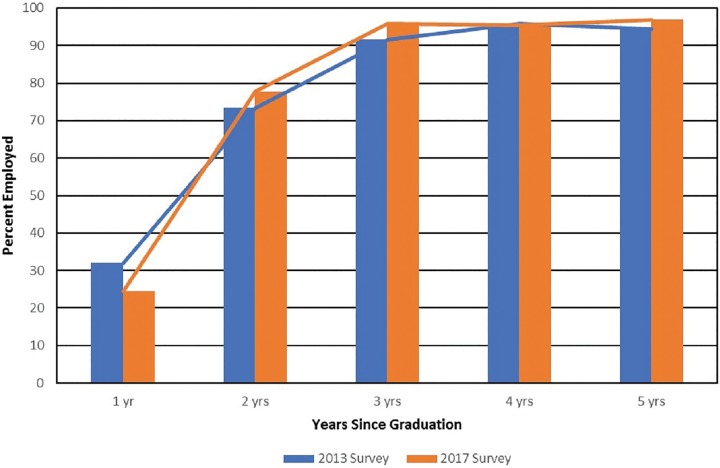

The results of the 2013 PRODS survey for employment by year of graduation are shown in Table 1. The 2013 results broken down by region are shown graphically in Figure 1, and the results broken down by program size are shown in Figure 2. The results of the 2017 PRODS survey for employment by year of graduation are shown in Table 2. The 2017 results broken down by region are shown graphically in Figure 3, and the results broken down by program size are shown in Figure 4. Both surveys document increasing employment with years from graduation as graduating residents pass through one or 2 years of postgraduate fellowships, with an eventual plateau as they exit their fellowships and enter the job market in postgraduate years 2, 3, and 4, when near-full employment is reached. Figure 5 illustrates a comparison between the results for aggregate employment by year in 2013 and 2017. Statistical analysis of the results is shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 1.

PRODS Workforce Survey 2013.

| Total | Responsive Programs | Nonresponsive Programs | Nonresponsive Programs With Residents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 87 | 2008 | 339 | 320 | 94% | 77 | 60 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 359 | 344 | 96% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 1802 | 2010 | 359 | 329 | 92% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 357 | 262 | 73% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 1514 | 2012 | 388 | 124 | 32% | 882 | 882 | ||

| By region | ||||||||

| Northeast | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 26 | 2008 | 115 | 100 | 87% | 23 | 17 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 124 | 114 | 92% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 596 | 2010 | 107 | 92 | 86% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 120 | 74 | 62% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 463 | 2012 | 130 | 37 | 28% | 229 | 229 | ||

| Midwest | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 21 | 2008 | 74 | 73 | 99% | 19 | 13 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 76 | 74 | 97% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 395 | 2010 | 83 | 77 | 93% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 81 | 65 | 80% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 339 | 2012 | 81 | 26 | 32% | 217 | 217 | ||

| West | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 11 | 2008 | 46 | 46 | 100% | 11 | 10 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 48 | 47 | 98% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 238 | 2010 | 50 | 48 | 96% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 43 | 27 | 63% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 226 | 2012 | 51 | 20 | 39% | 142 | 142 | ||

| South | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 29 | 2008 | 104 | 101 | 97% | 24 | 20 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 111 | 109 | 98% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 573 | 2010 | 119 | 112 | 94% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 113 | 96 | 85% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 486 | 2012 | 126 | 41 | 33% | 294 | 294 | ||

| By number of residents in program | ||||||||

| 0 to 14 | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | ||

| 35 | 2008 | 84 | 81 | 96% | 51 | 34 | ||

| Graduates | 2009 | 82 | 81 | 99% | Graduates | Graduates | ||

| 444 | 2010 | 97 | 90 | 93% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Residents | 2011 | 85 | 68 | 80% | Residents | Residents | ||

| 377 | 2012 | 96 | 29 | 30% | 336 | 336 | ||

| 15 to 19 | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | |||

| 21 | 2008 | 68 | 65 | 96% | 15 | |||

| Graduates | 2009 | 84 | 83 | 99% | Graduates | |||

| 396 | 2010 | 86 | 83 | 97% | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2011 | 76 | 60 | 79% | Residents | |||

| 347 | 2012 | 82 | 41 | 50% | 254 | |||

| 20 to 25 | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | |||

| 18 | 2008 | 88 | 78 | 89% | 7 | |||

| Graduates | 2009 | 98 | 92 | 94% | Graduates | |||

| 464 | 2010 | 83 | 76 | 92% | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2011 | 92 | 63 | 68% | Residents | |||

| 389 | 2012 | 103 | 30 | 29% | 160 | |||

| 26 up | ||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | |||

| 13 | 2008 | 99 | 96 | 97% | 4 | |||

| Graduates | 2009 | 95 | 88 | 93% | Graduates | |||

| 498 | 2010 | 93 | 80 | 86% | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2011 | 104 | 71 | 68% | Residents | |||

| 401 | 2012 | 107 | 24 | 22% | 132 | |||

Figure 1.

The 2013 Survey: percent of residents employed by years from graduation and region of training, reflecting the effect of fellowships on percent employed in post-residency years 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

The 2013 Survey: percent of residents employed by years from graduation and residency size, reflecting the effect of fellowships on percent employed in post-residency years 1 and 2.

Table 2.

PRODS Workforce Survey 2017.

| Total | Responsive Programs | Nonresponsive Programs | Nonresponsive Programs With Residents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 99 | 2012 | 419 | 408 | 97% | 65 | 42 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 411 | 392 | 95% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 2065 | 2014 | 434 | 416 | 96% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 414 | 322 | 78% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 1704 | 2016 | 387 | 95 | 25% | 654 | 654 | |||

| By region | |||||||||

| Northeast | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 28 | 2012 | 110 | 106 | 96% | 22 | 13 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 106 | 99 | 93% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 551 | 2014 | 122 | 116 | 95% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 117 | 89 | 76% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 456 | 2016 | 96 | 20 | 21% | 240 | 240 | |||

| Midwest | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 21 | 2012 | 96 | 91 | 95% | 15 | 9 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 102 | 96 | 94% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 395 | 2014 | 105 | 101 | 96% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 99 | 74 | 75% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 339 | 2016 | 99 | 17 | 17% | 105 | 105 | |||

| West | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 11 | 2012 | 77 | 75 | 97% | 7 | 4 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 74 | 72 | 97% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 238 | 2014 | 72 | 68 | 94% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 69 | 49 | 71% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 226 | 2016 | 70 | 15 | 21% | 70 | 70 | |||

| South | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 29 | 2012 | 136 | 134 | 99% | 21 | 16 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 129 | 125 | 97% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 573 | 2014 | 135 | 131 | 97% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 129 | 110 | 85% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 486 | 2016 | 122 | 43 | 35% | 239 | 239 | |||

| By number of residents in program | |||||||||

| 0 to 14 | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | Programs | |||

| 35 | 2012 | 98 | 89 | 91% | 45 | 22 | |||

| Graduates | 2013 | 90 | 85 | 94% | Graduates | Graduates | |||

| 444 | 2014 | 110 | 102 | 93% | 0 | 0 | |||

| Residents | 2015 | 95 | 66 | 69% | Residents | Residents | |||

| 377 | 2016 | 88 | 22 | 25% | 228 | 228 | |||

| 15 to 19 | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | ||||

| 21 | 2012 | 102 | 100 | 98% | 11 | ||||

| Graduates | 2013 | 105 | 100 | 95% | Graduates | ||||

| 396 | 2014 | 99 | 95 | 96% | 0 | ||||

| Residents | 2015 | 106 | 90 | 85% | Residents | ||||

| 347 | 2016 | 103 | 20 | 19% | 279 | ||||

| 20 to 25 | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | ||||

| 18 | 2012 | 140 | 138 | 99% | 5 | ||||

| Graduates | 2013 | 135 | 131 | 97% | Graduates | ||||

| 464 | 2014 | 138 | 133 | 96% | 0 | ||||

| Residents | 2015 | 129 | 99 | 77% | Residents | ||||

| 389 | 2016 | 121 | 32 | 26% | 109 | ||||

| 26 up | |||||||||

| Programs | Year | Graduates | Employed | % | Programs | ||||

| 13 | 2012 | 79 | 79 | 100% | 1 | ||||

| Graduates | 2013 | 81 | 76 | 94% | Graduates | ||||

| 498 | 2014 | 87 | 86 | 99% | 0 | ||||

| Residents | 2015 | 84 | 67 | 80% | Residents | ||||

| 401 | 2016 | 75 | 21 | 28% | 35 | ||||

Figure 3.

The 2017 Survey: percent of residents employed by years from graduation and region of training, reflecting the effect of fellowships on percent employed in post-residency years 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

The 2017 Survey: percent of residents employed by years from graduation and residency size, reflecting the effect of fellowships on percent employed in post-residency years 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

Percent of residents employed by years from graduation, reflecting the effect of fellowships on percent employed in post-residency years 1 and 2: comparison of totals from 2013 and 2017 surveys.

Table 3.

Employment by Years From Graduation—Variation by Region.*

| 2013 Employed | 2013 Graduated | 2017 Employed | 2017 Graduated | Sum Employed | Sum Graduated | 2013 Employed/Graduated | 2017 Employed/Graduated | Sum Employed/Graduated | Z | P (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationwide | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 320 | 339 | 406 | 419 | 726 | 758 | 94.40% | 96.90% | 95.78% | −1.703 | .089 |

| 4 years out | 344 | 359 | 392 | 411 | 736 | 770 | 95.82% | 95.38% | 95.58% | −0.300 | .765 |

| 3 years out | 329 | 359 | 416 | 434 | 745 | 793 | 91.64% | 95.85% | 93.95% | −2.474 | .013 |

| 2 years out | 262 | 357 | 322 | 414 | 584 | 771 | 73.39% | 77.78% | 75.75% | −1.418 | .156 |

| 1 year out | 124 | 388 | 95 | 387 | 219 | 775 | 31.96% | 24.55% | 28.26% | −2.291 | .022 |

| Northeast | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 100 | 115 | 106 | 110 | 206 | 225 | 86.96% | 96.36% | 91.56% | −2.537 | .011 |

| 4 years out | 114 | 124 | 99 | 106 | 213 | 230 | 91.94% | 93.40% | 92.61% | −0.422 | .673 |

| 3 years out | 92 | 107 | 116 | 122 | 208 | 229 | 85.98% | 95.08% | 90.83% | −2.381 | .017 |

| 2 years out | 74 | 120 | 89 | 117 | 163 | 237 | 61.67% | 76.07% | 68.78% | −2.392 | .017 |

| 1 year out | 37 | 130 | 20 | 96 | 57 | 226 | 28.46% | 20.83% | 25.22% | −1.305 | .192 |

| Midwest | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 73 | 74 | 91 | 96 | 164 | 170 | 98.65% | 94.79% | 96.47% | −1.351 | .177 |

| 4 years out | 74 | 76 | 96 | 102 | 170 | 178 | 97.37% | 94.12% | 95.51% | −1.035 | .300 |

| 3 years out | 77 | 83 | 101 | 105 | 178 | 188 | 92.77% | 96.19% | 94.68% | −1.037 | .300 |

| 2 years out | 65 | 81 | 74 | 99 | 139 | 180 | 80.25% | 74.75% | 77.22% | −0.875 | .381 |

| 1 year out | 26 | 81 | 17 | 99 | 43 | 180 | 32.10% | 17.17% | 23.89% | −2.337 | .019 |

| West | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 46 | 46 | 75 | 77 | 121 | 123 | 100.00% | 97.40% | 98.37% | −1.102 | .270 |

| 4 years out | 47 | 48 | 72 | 74 | 119 | 122 | 97.92% | 97.30% | 97.54% | −0.216 | .829 |

| 3 years out | 48 | 50 | 68 | 72 | 116 | 122 | 96.00% | 94.44% | 95.08% | −0.391 | .696 |

| 2 years out | 27 | 43 | 49 | 69 | 76 | 112 | 62.79% | 71.01% | 67.86% | −0.906 | .365 |

| 1 year out | 20 | 51 | 15 | 70 | 35 | 121 | 39.22% | 21.43% | 28.93% | −2.131 | .033 |

| South | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 101 | 104 | 134 | 136 | 235 | 240 | 97.12% | 98.53% | 97.92% | −0.760 | .447 |

| 4 years out | 109 | 111 | 125 | 129 | 234 | 240 | 98.20% | 96.90% | 97.50% | −0.643 | .520 |

| 3 years out | 112 | 119 | 131 | 135 | 243 | 254 | 94.12% | 97.04% | 95.67% | −1.141 | .254 |

| 2 years out | 96 | 113 | 110 | 129 | 206 | 242 | 84.96% | 85.27% | 85.12% | −0.069 | .945 |

| 1 year out | 41 | 126 | 43 | 122 | 84 | 248 | 32.54% | 35.25% | 33.87% | −0.450 | .653 |

Abbreviation: PRODS, Program Directors Section.

* Statistical comparison of 2013 and 2017 PRODS survey results.

Table 4.

Employment by Years from Graduation—Variation by Size of Residency Program. Statistical Comparison of 2013 and 2017 PRODS Survey Results.

| 2013 Employed | 2013 Graduated | 2017 Employed | 2017 Graduated | Sum Employed | Sum Graduated | 2013 Employed/Graduated | 2017 Employed/Graduated | Sum Employed/Graduated | Z | P (2-Tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-14 residents | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 81 | 84 | 89 | 98 | 170 | 182 | 96.43% | 90.82% | 93.41% | −1.521 | .128 |

| 4 years out | 81 | 82 | 85 | 90 | 166 | 172 | 98.78% | 94.44% | 96.51% | −1.548 | .122 |

| 3 years out | 90 | 97 | 102 | 110 | 192 | 207 | 92.78% | 92.73% | 92.75% | −0.016 | .988 |

| 2 years out | 68 | 85 | 66 | 95 | 134 | 180 | 80.00% | 69.47% | 74.44% | −1.616 | .106 |

| 1 year out | 29 | 96 | 22 | 88 | 51 | 184 | 30.21% | 25.00% | 27.72% | −0.788 | .430 |

| 15-19 residents | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 65 | 68 | 100 | 102 | 165 | 170 | 95.59% | 98.04% | 97.06% | −0.927 | .354 |

| 4 years out | 83 | 84 | 100 | 105 | 183 | 189 | 98.81% | 95.24% | 96.83% | −1.392 | .164 |

| 3 years out | 83 | 86 | 95 | 99 | 178 | 185 | 96.51% | 95.96% | 96.22% | −0.196 | .844 |

| 2 years out | 60 | 76 | 90 | 106 | 150 | 182 | 78.95% | 84.91% | 82.42% | −1.041 | .298 |

| 1 year out | 41 | 82 | 20 | 103 | 61 | 185 | 50.00% | 19.42% | 32.97% | −4.396 | .000 |

| 20-25 residents | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 78 | 88 | 138 | 140 | 216 | 228 | 88.64% | 98.57% | 94.74% | −3.271 | .001 |

| 4 years out | 92 | 98 | 131 | 135 | 223 | 233 | 93.88% | 97.04% | 95.71% | −1.175 | .240 |

| 3 years out | 76 | 83 | 133 | 138 | 209 | 221 | 91.57% | 96.38% | 94.57% | −1.528 | .126 |

| 2 years out | 63 | 92 | 99 | 129 | 162 | 221 | 68.48% | 76.74% | 73.30% | −1.369 | .171 |

| 1 year out | 30 | 103 | 32 | 121 | 62 | 224 | 29.13% | 26.45% | 27.68% | −0.447 | .655 |

| 26 or more residents | |||||||||||

| 5 years out | 96 | 99 | 79 | 79 | 175 | 178 | 96.97% | 100.00% | 98.31% | −1.560 | .119 |

| 4 years out | 88 | 95 | 76 | 81 | 164 | 176 | 92.63% | 93.83% | 93.18% | −0.314 | .754 |

| 3 years out | 80 | 93 | 86 | 87 | 166 | 180 | 86.02% | 98.85% | 92.22% | −3.212 | .001 |

| 2 years out | 71 | 104 | 67 | 84 | 138 | 188 | 68.27% | 79.76% | 73.40% | −1.773 | .076 |

| 1 year out | 24 | 107 | 21 | 75 | 45 | 182 | 22.43% | 28.00% | 24.73% | −0.857 | .391 |

Abbreviation: PRODS, Program Directors Section.

| US Census Regions: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | Midwest: | West | South |

| CT | IA | AK | AL |

| MA | IL | AZ | AR |

| ME | IN | CA | DC |

| NH | KS | CO | DE |

| NJ | MI | HI | FL |

| NY | MN | ID | GA |

| PA | MO | MT | KY |

| RI | ND | NM | LA |

| VT | NE | NV | MD |

| OH | OR | MS | |

| SD | UT | NC | |

| WI | WA | OK | |

| WY | PR | ||

| SC | |||

| TN | |||

| TX | |||

| VA | |||

| WV | |||

Abbreviation: PRODS, Program Directors Section.

| US Census Regions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast: | Midwest: | West: | South: |

| CT | IA | AK | AL |

| MA | IL | AZ | AR |

| ME | IN | CA | DC |

| NH | KS | CO | DE |

| NJ | MI | HI | FL |

| NY | MN | ID | GA |

| PA | MO | MT | KY |

| RI | ND | NM | LA |

| VT | NE | NV | MD |

| OH | OR | MS | |

| SD | UT | NC | |

| WI | WA | OK | |

| WY | PR | ||

| SC | |||

| TN | |||

| TX | |||

| VA | |||

| WV | |||

Abbreviation: PRODS, Program Directors Section.

Discussion

Data from the 2013 PRODS survey indicated that 94% of residents graduating in 2008 obtained employment within 5 years of graduation from residency, and 92% of those graduating in 2010 had obtained employment within 3 years. Similarly, data from the 2017 survey indicated that 97% of residents graduating in 2012 obtained positions within 5 years of graduation from residency, and 96% of those graduating in 2014 had obtained employment in 3 years. Although the surveys do not represent a single cohort of graduates followed at yearly intervals, comparison of the results for the different cohorts representing 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years from graduation suggests that for both surveys the 50% employment point occurs between 1 and 2 years out from completion of residency, and a plateau at the final employment figure is reached at the third year out from graduation. This pattern agrees completely with the results from the CAP survey on job search experience showing delayed entry into the job market, with most graduating residents doing one and about a quarter doing 2 years of postgraduate fellowship.7 Furthermore, comparing the percentage employed at 3, 4, and 5 years in the 2013 survey (91%, 96%, and 94%, respectively) and the percentage employed at 3, 4, and 5 years in the 2017 survey (96%, 95%, and 97%, respectively) indicates not only a high percentage of employment but also stability in the job market over the time period surveyed.

These data are also consistent with surveys of residents and fellows from the American Society for Clinical Pathology. In the 2018 ASCP Fellowship and Job Market Surveys,5 which queried all residents taking the 2018 ASCP Resident In-Service Examination, 51% of residents indicated an intent to do one fellowship, and 43% indicated an intent to do 2 fellowships. This would also predict average entry into the job market between 1 and 2 years after finishing residency. Additionally, 2% indicated an intent to do three or more fellowships, and 4% did not intend to do a fellowship, a group that includes individuals going into postdoctoral research positions, industry, or other nonclinical positions. These activities probably account for the employment plateau in both the 2013 and 2017 PRODS surveys falling slightly below 100%.

Stratification of the PRODS survey data by US Census Regions (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South) or by the size of the program (as indicated by the number of residents enrolled in the program in 2013 at the time of the survey) did not show large effects of those variables. Stratification of the data by US Census Regions (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South) showed in the 2017 survey a tendency not visible in the 2013 survey for graduates of Southern programs to progress toward the employment plateau slightly sooner than graduates of programs in other regions; however, the region with the most convincing statistical evidence for improvement between the surveys was the Northeast. The surveys did not provide convincing evidence for differences related to the size of the residency programs.

These survey data from the records of pathology residency program directors confirm with larger numbers and more comprehensive ascertainment the previously gathered survey data of pathology residency graduates,7 indicating that graduates of pathology residency programs are highly successful in finding employment and refuting impressions to the contrary. Currently, the entry of pathology residency graduates into the job market is not immediate but occurs after a delay that corresponds to the 1 or sometimes 2 subspecialty fellowships typically taken.5 That the 50% employment point is reached approximately 1.5 years after graduation is also consistent with the observation that almost all residents do one fellowship. Most residents (75%-80%) appear to be employed by 2 years after graduation, and a practice employment plateau at 95% to 96% of residents is achieved by 3 years after graduation. Perhaps most remarkable is the stability of the employment pattern over the combined time period of the 2 surveys. This indication of stability confirms the independent conclusion of a stable job market by Zynger and Pernick, based on an analysis of pathology job advertisements posted at PathologyOutlines.com from 2013 through 2017.8

Will this pattern continue into the future, given the predictions of workforce supply and demand made by the models of Robboy et al?1,3 The PRODS survey of 2016 asked residency directors if they felt that, given the option of taking a job over a second fellowship, most residents would take the job, and 97% agreed they would.6 However, queried on the choices of residents seeking a job over a first fellowship, the responses were more mixed; only 48% agreed, 26% were neutral, and 26% disagreed. Thus, it is clearly the view of most program directors that a projected trend toward more plentiful jobs may reduce the number of second fellowships done by residency graduates, but there is less consensus among program directors on the effect such a trend might have on first fellowships. As pathology continues past the point where pathologists leaving the workforce outnumber those entering it, and as the potential trends in demand declare themselves more concretely, it will be interesting to see whether residents and employers alike come to trust that both employment and the competency it requires can be achieved sooner than the present pattern documented above. The phenomenon of late unexpected openings in fellowship positions may be the first harbinger of that shift.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: For Drs Brissette and Childs: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The identification of specific products or scientific instrumentation does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the author, Department of Defense, or any component agency.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Charles F. Timmons  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-8569

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-8569

Richard M. Conran  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4053-1784

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4053-1784

Dita Gratzinger  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9182-8123

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9182-8123

References

- 1. Robboy SJ, Weintraub MBA, Horvath AE, et al. Pathologist workforce in the United States. I. development of a predictive model to examine factors influencing supply. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1723–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Metter DM, Colgan TJ, Leung ST, Timmons CF, Park JY. Trends in the US and Canadian pathologist workforces from 2007 to 2017. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2:e194337 doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:1413–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bennett BD. Certification from the American Board of Pathology: getting it and keeping it. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:978–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genzen J, Kasten J, Wagner J. ASCP fellowship & job market surveys. A report on the 2018 RISE, FISE, FISHE, NPISE, PISE and TMISE surveys In: Rittershaus AC, ed. American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2019 Resident Council Fellowship & Job Market Survey. www.ascp.org/residents.

- 6. Naritoku WY, Timmons CF. The pathologist pipeline: Implications of changes for programs and post-sophomore fellowships—Program Directors’ Section perspective. Acad Pathol. 2016;3 doi:10.1177/2374289516646117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gratzinger D, Johnson KA, Brissette MD, et al. The recent pathology residency graduate job search experience: a synthesis of 5 years of College of American Pathologists job market surveys. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zynger DL, Pernick N. Understanding the pathology job market: an analysis of 2330 pathology job advertisements from 2013 through 2017. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]