Abstract

Background

All non-sensitized Rhesus D (RhD)-negative pregnant women in Germany receive antenatal anti-D prophylaxis without knowledge of fetal RhD status. Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma could avoid unnecessary anti-D administration. In this paper, we systematically reviewed the evidence on the benefit of NIPT for fetal RhD status in RhD-negative pregnant women.

Methods

We systematically searched several bibliographic databases, trial registries, and other sources (up to October 2019) for controlled intervention studies investigating NIPT for fetal RhD versus conventional anti-D prophylaxis. The focus was on the impact on fetal and maternal morbidity. We primarily considered direct evidence (from randomized controlled trials) or if unavailable, linked evidence (from diagnostic accuracy studies and from controlled intervention studies investigating the administration or withholding of anti-D prophylaxis). The results of diagnostic accuracy studies were pooled in bivariate meta-analyses.

Results

Neither direct evidence nor sufficient data for linked evidence were identified. Meta-analysis of data from about 60,000 participants showed high sensitivity (99.9%; 95% CI [99.5%; 100%] and specificity (99.2%; 95% CI [98.5%; 99.5%]).

Conclusions

NIPT for fetal RhD status is equivalent to conventional serologic testing using the newborn’s blood. Studies investigating patient-relevant outcomes are still lacking.

Keywords: Genotyping techniques, Rh-Hr blood-group system, Fetus, Benefit assessment, Systematic review

Bulleted statements

what’s already known about this topic? Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for fetal RhD from maternal plasma may enable targeted anti-D prophylaxis for RhD-negative women carrying an RhD-positive fetus.

what does this study add? NIPT of fetal RhD shows high sensitivity and specificity and is equivalent to conventional postnatal testing using a blood sample of the newborn.

Background

During pregnancy, a Rhesus D (RhD)-negative woman may develop antibodies if her fetus is RhD-positive. These maternal allo-antibodies directed against fetal red cell surface antigens that the mother herself lacks can lead to hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) [1]. Anti-D immunoglobulin (anti-D) administration was introduced in the early 1970s to reduce the incidence of alloimmunization (sensitization) of pregnant women to the D antigen and subsequently the incidence of HDFN, which has since decreased dramatically [2]. In many countries, the current policy is to administer anti-D to non-sensitized RhD-negative pregnant women in the 28th week of gestation [3]. After birth, the cord blood is phenotyped and postnatal anti-D prophylaxis is offered only if the newborn is RhD-positive.

In a Cochrane review of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), postnatal anti-D prophylaxis was shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of sensitization 6 months after birth and in a subsequent pregnancy [2]; the benefits were seen when anti-D was given within 72 h of birth, with higher doses being more effective than lower ones. However, postnatal prophylaxis does not prevent antenatal sensitization [4]. The current policy of universal antenatal anti-D administration leads to approximately 50,000 RhD-negative pregnant women per year in Germany receiving anti-D prophylaxis even though they are carrying an RhD-negative fetus [5].

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for fetal RhD from maternal plasma may enable anti-D prophylaxis to be withheld from RhD-negative women carrying an RhD-negative fetus. As early as 1998, Lo et al. [6] described the presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and the possibility of non-invasive determination of the fetal RhD status. These findings enable non-invasive, risk-free antenatal testing, which is mostly performed using the real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

The aim of the current article was to systematically review the evidence on the benefit of NIPT for fetal RhD status in RhD-negative pregnant women and subsequent targeted anti-D prophylaxis. The focus of the assessment was on patient-relevant outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and methodological approach

IQWiG’s responsibilities and general methods are described in its methods paper [7]. The methods for the present assessment were defined a priori and published in a German-language protocol on the website of the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) [8]. The full German-language report including the original literature search [9], as well as an English-language extract [10], are also available on the website. The report is currently being used to inform a reimbursement decision on future RhD testing in Germany, thus potentially affecting about 750.000 pregnant women per year.

An update search was conducted for the current article, which was written according to the PRISMA statement [11] (see Additional file 1).

Eligibility criteria

The target population comprised non-sensitized RhD-negative pregnant women investigated in controlled intervention studies of the diagnostic-therapeutic chain. The test intervention was NIPT for fetal RhD, with subsequent administration or withholding of anti-D prophylaxis, depending on the test result. The control intervention was conventional anti-D prophylaxis for all non-sensitized RhD-negative pregnant women using the anti-D dose approved in Germany. The patient-relevant outcomes investigated included rates of mortality, HDFN and adverse events as well as health-related quality of life (if meaningful, referring to both maternal and fetal or pediatric outcomes). Sensitization rates were investigated as a surrogate outcome for HDFN.

If the kind of direct evidence described above was not available, we planned to apply a linked evidence approach [12].

We considered the following evidence and study types:

Either direct evidence from RCTs of the diagnostic-therapeutic chain (if not available, prospective intervention studies were also considered). Or, if no direct evidence was available, linked evidence [12] from studies on diagnostic accuracy, together with controlled intervention studies investigating the benefit (prevention of sensitization) and harm (adverse events) of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis. The detailed eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Direct evidence | Linked evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intervention studies | diagnostic accuracy study | intervention studies | ||

| Population | • RhD-negative pregnant women without sensitization | • RhD-negative pregnant women without sensitization | • RhD-negative pregnant women without sensitization | |

| Study intervention | • non-invasive prenatal RhD-testing of the fetus and omission of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis in the case of an RhD- negative fetus | • non-invasive prenatal RhD-testing of the fetus | • administration of anti-D prophylaxis | |

| Control intervention | • anti-D prophylaxis for all RhD-negative pregnant women | • postnatal RhD-testing of the newborn | • no antenatal administration of anti-D prophylaxis | |

| Benefits | Harms | |||

| Patient-relevant outcomes/diagnostic accuracy measures | • mortality | • test accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, false-negative rate, false-positive rate) | • mortality | • mortality |

| • HDFN (surrogate outcome: sensitization) | • HDFN (surrogate outcome: sensitization) | • adverse events | ||

| • adverse events | • health-related quality of life | |||

| • health-related quality of life | • health-related quality of life | |||

| Study type | • RCTs | • prospective cohort studies | • RCTs | • RCTs |

| • prospective, non-randomized controlled intervention studies | • prospective, non-randomized controlled intervention studies | • prospective, non-randomized controlled intervention studies | ||

| • cohort studies (also retrospective or with historical controls) | ||||

HDFN: hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn

Search strategy and study selection

We searched for relevant primary studies and secondary publications (systematic reviews and HTA reports) in MEDLINE (1946 to October 2019) and EMBASE (1974 to October 2019) via Ovid as well as in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (October 2019). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane Reviews), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (Other Reviews), and the Health Technology Assessment Database (Technology Assessments) were searched for relevant secondary publications. In addition, we screened web-based trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, and the EU Clinical Trials Register). The search strategy, which was developed by one information specialist and checked by another, is presented in Additional file 2. We also screened the websites of the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of the citations retrieved to identify potentially eligible primary and secondary publications. The full texts of these articles were obtained and independently evaluated by the same two reviewers applying the full set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Study selection was performed in IQWiG’s internal web-based trial selection database (webTSDB) [13]. Endnote X9 was used for citation management.

Data extraction

The individual steps of the data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment procedures were always conducted by one person and checked by another; disagreements were resolved by consensus. Details of the studies were extracted using standardized tables developed and routinely used by IQWiG. Depending on the study question (comparison of interventions or evaluation of diagnostic accuracy) we extracted information on study design, sample size, patient-relevant outcomes or diagnostic accuracy, location and period during which the study was conducted, dropout rate, gestational age, treatment regimen and control treatment or index test and reference standard, as well as risk-of-bias items (see below).

Assessment of risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for individual studies, as well as for each outcome, and rated these risks as “high” or “low”.

For controlled intervention studies, the risk of bias was assessed by determining the adequacy of the following quality criteria, which closely follow the criteria of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [14]): generation of random allocation sequence or whether both treatment groups were studied in parallel, allocation concealment or comparability of groups, blinding of participants and investigators, as well as selective outcome reporting. If the risk of bias on the study level was rated as “high”, the risk of bias on the outcome level was also generally rated as “high”. The risk of bias for each outcome was assessed by determining the adequacy of the following quality criteria: blinding of outcome assessors, application of the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, and selective outcome reporting.

For studies on diagnostic accuracy, the risk of bias was assessed by determining the adequacy of the following quality criteria following QUADAS-2 [15]: patient selection, index test, reference standard, as well as flow and timing. Concerns about applicability were assessed by determining the adequacy of the following quality criteria: patient selection, index test and reference standard.

The risk of bias determines the confidence in the conclusions drawn from the study data and can be used to explore possible reasons for heterogeneity if the studies differ in their risk of bias.

Data analysis

For the statistical analysis of controlled intervention studies, we used the results from the ITT analysis. We reported the treatment effects as odds ratios (ORs), including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for binary outcomes. We conducted a random effects meta-analysis of intervention studies using the Knapp-Hartung method [16] as well as sensitivity analyses using the Mantel-Haenszel method and a Beta-binomial model. No subgroup analyses were conducted.

Separate meta-analyses were performed to pool the results of diagnostic accuracy studies. Sensitivities and specificities were summarized in a bivariate meta-analysis. Model parameters were estimated by means of a generalized linear mixed model. No sensitivity or subgroup analyses were conducted.

All calculations were performed with the statistical software SAS.

Results

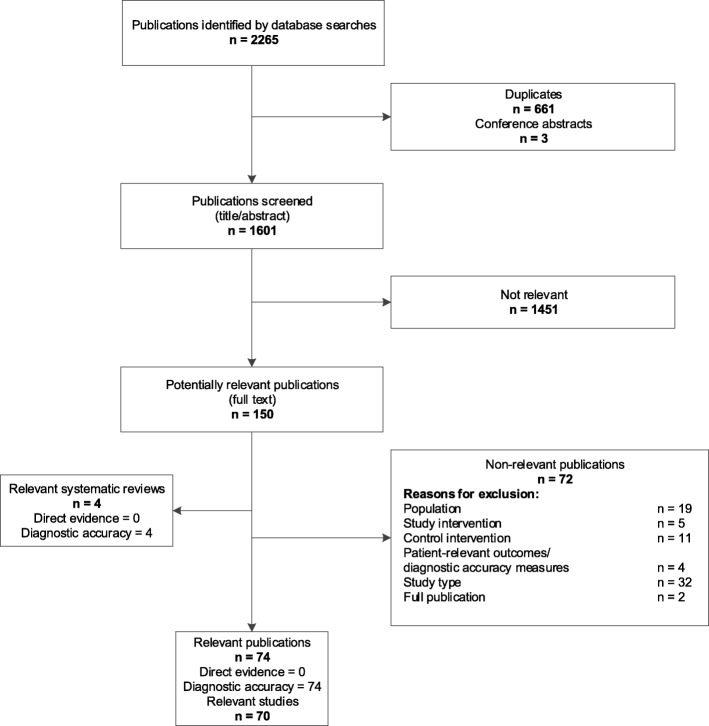

Literature search (see Figs. 1 and 2 for flowchart)

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection for direct trial evidence and linked evidence (diagnostic accuracy studies)

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of study selection for linked evidence (controlled intervention studies – benefit and harm of anti-D prophylaxis)

Overall, 2237 studies were screened. No studies of the diagnostic-therapeutic chain were identified. 70 studies on diagnostic accuracy including approximately 66,000 participants were identified (all in bibliographic databases), of which the 12 largest (including over 90% of the total study population) were included in the analysis [5, 17–28]. Two controlled intervention studies investigating the benefit (prevention of sensitization) of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis were identified (in bibliographic databases). However, they used a low and non-approved dose for anti-D prophylaxis [29, 30]. The results of these off-label studies are described below. No studies investigating harm (adverse events) from anti-D prophylaxis were identified.

Study characteristics

Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the 12 largest diagnostic accuracy studies and the two off-label studies on anti-D prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Study | Study design | Participants (intervention/control) | Treatment/index test | Patient-relevant outcomes/ reference test | Location/recruitment period | Weeks’ gestation Median [min; max] | Drop-out (intervention/control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huchet 1987 [29] | prospective intervention study | 1969 (927/955) with RhD-positive newborns: (599/590) | 100 μg anti-D immunoglobulin, one dose at 26 to 29 and one at 32–36 weeks’ gestation | sensitization | 23 hospitals in the Paris region 01/1983–06/1984 | Not stated | |

| Lee 1995 [30] | RCT | 2541 (1268/1273) with RhD-positive newborns: (513/595) | 250 IU anti-D immunoglobulin at 28 and 34 weeks’ gestation | sensitization | Multi-center study in UK Not stated | 642 (362/280) | |

| De Haas 2016 [17] | prospective cohort study | 32,222 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | Netherlands (national screening program) 07/2011–10/2012 | Mean in weeks + days [SD] 27 + 6 [0 + 6] [min; max] [27; 29] | 6433 |

| Clausen 2014 [18] | prospective cohort study | 14,547 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5, 7 or 10 |

serologic cord blood testing | Denmark (national screening program) 01/2010 for 2 years | 25 [n. a.] | 1879 |

| Haimila 2017 [19] | prospective cohort study | 10,814 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing / heel stick | Finland (national screening program) 02/2014–01/2016 | n. a. [24; 26] | 0 |

| Wikman 2012 [20] | prospective cohort study | 4118 |

cff-DNA RHD Exon 4 |

serologic cord blood testing / blood sample of newborn | Sweden 09/2009–05/2011 | 10 [3; 40] | 466 |

| Chitty 2014 [21] | prospective cohort study | 3039 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | England 2009–2012 | 19 [5; 35] | 781 |

| Finning 2008 [22] | prospective cohort study | 1997 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | England/not stated | 28 [8; 38] | 128 |

| Müller 2008 [5] | prospective cohort study | 1113 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | Germany 2006 – not stated | 25 [6; 32] | 91 |

| Macher 2012 [23] | prospective cohort study | 1012 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | Spain 2010 | n.a. [10; 28] | 0 |

| Hyland 2017 [24] | prospective cohort study | 665 |

cff-DNA RHD Exon 5 and 10 |

serologic cord blood testing | Australia Not stated | 19.3 [9; 37] | 66 |

| Akolekar 2011 [26] | prospective cohort study | 591 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | UK Not stated | 12,4 [11; 14] | 5 |

| Minon 2008 [27] | prospective cohort study | 563 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 4, 5 and 10 |

serologic cord blood testing | Belgium 11/2002–12/2006 | 17,5 [10; 38] | Not stated |

| Soothill 2015 [28] | prospective cohort study | 529 |

cff-DNA RHD Exons 5 and 7 |

serologic cord blood testing | England 04–09/2013 | Not stated | 30 |

cff cell-free fetal, n.a not available, RHD rhesus factor, SD standard deviation

Risk of bias

Both off-label studies on anti-D prophylaxis showed a high risk of bias on the study and outcome level, for example, because of unclear information on the blinding of patients and investigators and/or an inappropriate ITT analysis. In 11 of the 12 diagnostic accuracy studies, the risk of bias was high in the total score (Table 3). However, the pooled estimate of all studies were similar to the results of the study with the low risk of bias.

Table 3.

Risk of bias of included studies (QUADAS 2) and concerns regarding applicability

| Study | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Applicability concerns - total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Haas 2016 | low | unclear | low | high | low |

| Clausen 2014 | low | unclear | unclear | high | low |

| Haimila 2017 | low | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Wikman 2012 | low | unclear | unclear | high | low |

| Chitty 2014 | unclear | low | unclear | high | low |

| Finning 2008 | unclear | unclear | low | low | low |

| Müller 2008 | low | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Macher 2012 | low | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Hyland 2017 | low | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Akolekar 2011 | unclear | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Minon 2008 | low | unclear | unclear | low | low |

| Soothill 2015 | low | low | low | low | low |

Effects of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis

The meta-analysis of the results of the two off-label studies (Additional file 3) showed no significant differences in sensitization at the time of delivery (OR 0.33, 95% CI [0; 123,851], number of participants = 2297, number of studies = 2, I2 = 51%). The CI is very wide and the effect could not be estimated with adequate precision. We therefore conducted different sensitivity analyses with 2 different meta-analysis methods, the Mantel-Haenszel (MH) method and the beta-binomial model (BBM). Both led to more precise estimates (MH: 0.37 [0.13; 1.06], number of participants = 2297, number of studies = 2, I2 = 51%; BBM 0.30 [0.07; 1.26], number of participants = 2297, number of studies = 2), but neither showed a significant difference between the test and control groups.

Diagnostic accuracy

Sensitivities and specificities from the 12 studies are described comparatively in Table 4. The bivariate meta-analysis showed high values for both measures of diagnostic accuracy of NIPT in RhD-negative pregnant women (sensitivity: 99.9% (95% CI [99.5%; 100%]; specificity: 99.2% (95% CI [98.5%; 99.5%], number of participants = 60,011, number of studies = 12). Two of the studies [5, 17] assessed discordant results of ante- and postnatal tests by genetic testing. They found that the postnatal test also produced a few incorrect test results (about 35 false-negative results out of 27,000 tests due to RhD variants or confusion of the samples), indicating that both tests can be regarded as equivalent.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy results

| Study | n | TP | FN | FP | TN | Inconclusive results (%)a, b | Sensitivity in % [95% CI]b | Specificity in % [95% CI]b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Haas 2016 | 25,789 | 15,816 | 9 | 225 | 9739 | 0 (0)c | 99.9 [99.9; 100] | 97.7 [97.4; 98.0] |

| Clausen 2014 | 12,668 | 7636 | 11 | 41 | 4706 | 274 (2.2) | 99.9 [99.7; 99.9] | 99.1 [98.8; 99.4] |

| Haimila 2017 | 10,814 | 7080 | 1 | 7 | 3640 | 86 (0.80) | 100 [99.9; 100] | 99.8 [99.6; 99.9] |

| Wikman 2012 | 3652 | 2236 | 55 | 15 | 1331 | 15b (0.4) | 97.6 [96.9; 98.2] | 98.9 [98.2; 99.4] |

| Chitty 2014 | 956d | 535 | 1 | 4 | 341 | 75 (7.8) | 99.8 [99.0; 100] | 98.8 [97.1; 99.7] |

| 2288e | 2563 | 19 | 18 | 1920 | 393 (17.2) | 99.3 [98.9; 99.6] | 99.1 [98.5; 99.4] | |

| Finning 2008 | 1869 | 1118 | 3 | 14 | 670 | 64 (3.4) | 99.7 [99.2; 99.9] | 98.0 [96.6; 98.9] |

| Müller 2008 | 1022 | |||||||

| “Spin column”f | 660b | 2b | 3b | 357b | 0 (0)b | 99.7 [98.9; 100] | 99.2 [97.6; 99.8] | |

| “Magnetic tips”f | 661b | 1b | 7b | 353b | 0 (0)b | 99.8 [99.2; 100] | 98.1 [96.0; 99.2] | |

| Macher 2012 | 1012 | 619 | 0 | 7 | 386 | 0 (0) | 100 [99.4; 100] | 98.2 [96.4; 99.3] |

| Hyland 2017 | 599 | 370 | 0 | 1 | 226 | 2 (0.3)b | 100 [99.0; 100] | 99.6 [97.6; 100] |

| Akolekar 2011 | 586 | 332 | 6 | 0 | 164 | 84 (14.3) | 98.2 [96.2; 99.3] | 100 [97.8; 100] |

| Minon 2008 | 545 | 360 | 0 | 0 | 185 | 0 (0) | 100 [99.0; 100] | 100 [98.0; 100] |

| Soothill 2015 | 499 | 267 | 0 | 1 | 170 | 61g (12.2) | 100 [98.6; 100] | 99.4 [96.8; 100] |

| pooled estimateh | 99.9 [99.5; 100] | 99.2 [98.5; 99.5] | ||||||

a: Proportion of study participants with inconclusive results

b: IQWiG’s own calculation

c: 0.21% of samples were inconclusive (women with RhD variants). In this study these samples were categorized by the positive samples

d: Results of the largest cohort of this study (11 to 13 weeks’ gestation). These results are included in the pooled effect

e: Summarized data for 2288 evaluated women with a total of 4913 data sets including up to 4 measurement points (multiple measurements). The number of blood samples is therefore shown here

f: “Spin column” and “magnetic tips” are two different methods for the extraction of cff-DNA from plasma samples. The patients with samples extracted by the spin column method are included in the pooled effect

g: Treated like positive samples

h: Generalized linear model to take into account the dependency between sensitivity and specificity

cff: cell-free fetal; FN: false negative; FP: false positive; CI: confidence interval; n: number of evaluated participants; RHD: rhesus factor; TN: true negative; TP: true positive

Discussion

The current review shows a lack of studies investigating patient-relevant outcomes after NIPT for fetal RhD status in RhD-negative pregnant women and subsequent targeted anti-D prophylaxis. The analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies shows that NIPT has a high sensitivity and specificity.

Comparison with the literature

Anti-D prophylaxis

The Cochrane review by McBain 2015 [4] included the same two off-label studies on antenatal anti-D prophylaxis described in our review [29, 30]. In accordance with our findings, the authors stated that these two studies do not provide conclusive evidence that the use of anti-D during pregnancy shows a benefit in terms of incidence of Rhesus D sensitization.

A systematic review by Pilgrim 2009 [31] contained 12 studies (including one of the off-label studies [29] described in our review) with a high risk of bias, such as studies with historical controls, retrospective studies, and community intervention trials. They concluded that antenatal anti-D prophylaxis may reduce the incidence of sensitization. Furthermore, they noted that anti-D is associated with only minimal adverse effects.

In a systematic review by Turner 2012 [32], a pooled OR of 0.31 (95% CI [0.17; 0.56]) was determined in an adjusted meta-analysis of 10 studies on the administration of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis and the incidence of sensitization. Among these were the two off-label studies described in our review and further studies with historical control groups. The authors concluded that there was strong evidence of the effectiveness of routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for prevention of sensitization.

Diagnostic accuracy

We identified 70 relevant studies on diagnostic accuracy, of which 58 included only a comparatively small number of participants (2 to 467). We therefore restricted our sample to the 12 largest studies, which comprised over 90% of the overall study population. A sufficiently accurate determination of the diagnostic accuracy of NIPT for fetal RhD was thus possible, showing high sensitivity and specificity.

Mackie 2017 [33] included 30 studies and found a sensitivity of 99.3% (95% CI [98.2, 99.7%]) and a specificity of 98.4% (95% CI [96.4, 99.3%]). These results are comparable to our findings, despite a differing study pool (only 2 of the 30 studies were included in our review).

A British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) report from 2016 [34, 35] on diagnostic accuracy included eight studies exclusively using “high throughput” NIPT (six of these studies were included in our review). The corresponding HTA report [36] found that after 11 weeks of pregnancy only 1% of the samples showed an incorrect test result (almost all false-positive) and approximately 7% of the samples showed an inconclusive result. A pooled rate of false-negative results of 0.34% [95% CI [0.15%; 0.76%)] was reported, which is comparable to the sensitivity determined in our review (99.9% [95% CI [99.5%; 100%]). According to NICE, if antenatal anti-D prophylaxis was administered only to RhD-negative pregnant women with RhD-positive fetuses, this would result in potential cost savings between £296,000 and £409,000 per 100,000 pregnancies [36, 37]. NICE has issued a positive recommendation for NIPT [38].

A French Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) report on diagnostic accuracy from 2011 [39, 40] is based on 31 studies, which were not pooled in a meta-analysis. Despite the differing study pools (only two studies were included in our review), their results are comparable: the majority of the studies included (22 of 31) reported a sensitivity and specificity of over 95%. HAS concluded that the expected benefit of NIPT was sufficient to justify reimbursement by the health insurance funds, and it is now being reimbursed in France. They recommend applying the test between the 11th and 28th week of pregnancy.

Limitations

The meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy was limited by fact that the true fetal RhD status could not be determined by genetic testing in the primary studies. Only two studies resolved discrepancies between the ante- and postnatal test. As postnatal testing can also be incorrect, using postnatal test results as the reference standard might underestimate the true accuracy of the prenatal test. An additional limitation of the present review was the restriction of analyses to only the largest primary studies. However, the inclusion of all studies, regardless of sample size, would probably not have altered the main findings. Furthermore, the non-publication of negative findings is more common in smaller studies [41], so focusing on larger studies reduces bias.

Ethical aspects

With the implementation of NIPT for fetal RhD status, almost 40% of antenatal anti-D administrations could be saved per year in Germany [5]. Important aspects are not only the costs, but also ethical issues concerning the acquisition of anti-D: male donors are sensitized with a blood product to produce the vaccine and the number of donors worldwide is limited; most countries rely on imports.

Conclusion

In summary, NIPT for fetal RhD status shows high sensitivity and specificity and is equivalent to conventional postnatal testing using a blood sample of the newborn, which also produces a few incorrect test results. Some countries (e.g. Denmark and Netherlands) have already implemented NIPT and have abolished postnatal testing. However, as studies investigating the effects of NIPT on patient-relevant outcomes are still lacking, before its widespread implementation as the only test to determine RhD status, we recommend evaluating the benefit of NIPT in the respective health care settings.

Supplementary information

Additional file 3: Table S5. Effects of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lisa Schell and Katrin Dreck for supporting study selection and data extraction, Inga Overesch for conducting the update search, Mandy Kromp for checking the data analysis, and Natalie McGauran for editorial support.

Abbreviations

- BBM

beta-binomial model

- CI

Confidence interval

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- HAS

Haute Autorité de Santé

- HDFN

Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn

- HTA

Health Technology Assessment

- IQWiG

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care

- ITT

Intention-to-treat

- MH

Mantel-Haenszel

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIPT

Non-invasive prenatal testing

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QUADAS-2

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RhD

Rhesus D

- webTSDB

Web-based trial selection database

Authors’ contributions

BR wrote the main part of the manuscript, made substantial contributions to the conception and design, and was involved in the acquisition and interpretation of the data. GB was involved in writing the manuscript and provided clinical expertise. WS performed all statistical analyses and was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. DS developed and conducted the literature search. SP was involved in the screening, collection and interpretation of data. DF made substantial contributions to the conception and design, was involved in the interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received non-financial support from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Four of the six authors are IQWiG employees and were thus involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed in this research are included in this published article or in the full German-language report, https://www.iqwig.de/download/D16-01_Bestimmung-fetaler-Rhesusfaktor_Abschlussbericht_V1-0.pdf

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12884-020-2742-4.

References

- 1.Urbaniak SJ, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Blood Rev. 2000;14:44–61. doi: 10.1054/blre.1999.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowther CA, Middleton P. Anti-D administration after childbirth for preventing Rhesus alloimmunisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1997;(2):CD000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sperling JD, Dahlke JD, Sutton D, Gonzales JM, Chauhan MD. Prevention of RhD alloimmunization: a comparison of four national guidelines. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35:110–119. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1642063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBain RD, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Anti-D administration in pregnancy for preventing Rhesus alloimmunisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD000020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Müller SP, Bartels I, Stein W, Emons G, Gutensohn K, Köhler M, et al. The determination of the fetal D status from maternal plasma for decision making on Rh prophylaxis is feasible. Transfusion (Paris) 2008;48:2292–2301. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo YM, Hjelm NM, Fidler C, Sargent IL, Murphy MF, Chamberlain PF, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal RhD status by molecular analysis of maternal plasma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1734–1738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812103392402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care . General methods: version 5.0. 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care . Non-invasive determination of the fetal rhesus factor to prevent maternal rhesus sensitization: report plan [German] 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Non-invasive determination of the fetal rhesus factor to prevent maternal rhesus sensitization: final report [German]. 2018. https://www.iqwig.de/download/D16-01_Bestimmung-fetaler-Rhesusfaktor_Abschlussbericht_V1-0.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

- 10.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Non-invasive determination of the fetal rhesus factor to prevent maternal rhesus sensitization: extract. 2018. https://www.iqwig.de/download/D16-01_Determination-of-fetal-rhesus-factor_Extract-of-final-report_V1-0.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

- 11.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlin T, Lehman S, Hiller JE, Ryan P. The "linked evidence approach" to assess medical tests: a critical analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29:343–350. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hausner E, Ebrahim S, Herrmann-Frank A, Janzen T, Kerekes MF, Pischedda M, et al. Study selection by means of a web-based trial selection DataBase (webTSDB). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:16–7.

- 14.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartung J. An alternative method for meta-analysis. Biom J. 1999;41:901–916. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4036(199912)41:8<901::AID-BIMJ901>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Haas M, Thurik FF, Van der Ploeg CP, Veldhuisen B, Hirschberg H, Soussan AA, et al. Sensitivity of fetal RHD screening for safe guidance of targeted anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: prospective cohort study of a nationwide programme in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2016;355:i5789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clausen FB, Steffensen R, Christiansen M, Rudby M, Jakobsen MA, Jakobsen TR, et al. Routine noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal RHD in plasma of RhD-negative pregnant women: 2 years of screening experience from Denmark. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:1000–1005. doi: 10.1002/pd.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haimila K, Sulin K, Kuosmanen M, Sareneva I, Korhonen A, Natunen S, et al. Targeted antenatal anti-D prophylaxis program for RhD-negative pregnant women: outcome of the first two years of a national program in Finland. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:1228–1233. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wikman AT, Tiblad E, Karlsson A, Olsson ML, Westgren M, Reilly M. Noninvasive single-exon fetal RHD determination in a routine screening program in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:227–234. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825d33d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chitty LS, Finning K, Wade A, Soothill P, Martin B, Oxenford K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of routine antenatal determination of fetal RHD status across gestation: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finning K, Martin P, Summers J, Massey E, Poole G, Daniels G. Effect of high throughput RHD typing of fetal DNA in maternal plasma on use of anti-RhD immunoglobulin in RhD negative pregnant women: prospective feasibility study. BMJ. 2008;336:816–818. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39518.463206.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macher HC, Noguerol P, Medrano-Campillo P, Garrido-Marquez MR, Rubio-Calvo A, Carmona-Gonzalez M, et al. Standardization non-invasive fetal RHD and SRY determination into clinical routine using a new multiplex RT-PCR assay for fetal cell-free DNA in pregnant women plasma: results in clinical benefits and cost saving. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyland CA, Millard GM, O’Brien H, Schoeman EM. Non-invasive fetal RHD genotyping for RhD negative women stratified into RHD gene deletion or variant groups: comparative accuracy using two blood collection tube types. Pathology (Phila) 2017;49:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyland CA, Gardener GJ, Davies H, Ahvenainen M, Flower RL, Irwin D, et al. Evaluation of non-invasive prenatal RHD genotyping of the fetus. Med J Aust. 2009;191:21–25. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akolekar R, Finning K, Kuppusamy R, Daniels G, Nicolaides KH. Fetal RHD genotyping in maternal plasma at 11-13 weeks of gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29:301–306. doi: 10.1159/000322959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minon JM, Gerard C, Senterre JM, Schaaps JP, Foidart JM. Routine fetal RHD genotyping with maternal plasma: a four-year experience in Belgium. Transfusion (Paris) 2008;48:373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soothill PW, Finning K, Latham T, Wreford-Bush T, Ford J, Daniels G. Use of cffDNA to avoid administration of anti-D to pregnant women when the fetus is RhD-negative: implementation in the NHS. BJOG. 2015;122:1682–1686. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huchet J, Dallemagne S, Huchet C, Brossard Y, Larsen M, Parnet-Mathieu F. Ante-partum administration of preventive treatment of Rh-D immunization in Rhesus-negative women: parallel evaluation of transplacental passage of fetal blood cells; results of a multicenter study carried out in the Paris region [French] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1987;16:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee D, Rawlinson VI. Multicentre trial of antepartum low-dose anti-D immunoglobulin. Transfus Med. 1995;5:15–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1995.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilgrim H, Lloyd-Jones M, Rees A. Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for RhD-negative women: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:iii, ix-xi, 1–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Turner RM, Lloyd-Jones M, Anumba DO, Smith GC, Spiegelhalter DJ, Squires H, et al. Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis in women who are Rh(D) negative: meta-analyses adjusted for differences in study design and quality. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, Morris RK, Kilby MD. The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124:32–46. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal RHD genotype. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.CRD/CHE Technology Assessment Group . High-throughput, non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal rhesus D status in RhD-negative women not known to be sensitised to the RhD antigen: a systematic review and economic evaluation. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saramago P, Yang H, Llewellyn A, Walker R, Harden M, Palmer S, et al. High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal rhesus D status in RhD-negative women not known to be sensitised to the RhD antigen: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2018;22:1–172. doi: 10.3310/hta22130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . New blood test for pregnant women could help thousands avoid unnecessary treatment. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal RHD genotype: recommendations. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haute Autorité de Santé . Détermination prénatale du génotype RHD foetal à partir du sang maternel: rapport d’évaluation technologique. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haute Autorité de Santé . Détermination prénatale du génotype RHD foetal à partir du sang maternel: avis sur les actes. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence; publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 3: Table S5. Effects of antenatal anti-D prophylaxis

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed in this research are included in this published article or in the full German-language report, https://www.iqwig.de/download/D16-01_Bestimmung-fetaler-Rhesusfaktor_Abschlussbericht_V1-0.pdf