Abstract

Introduction

Passive exposure to the use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS or e-cigarettes) has been shown to generalize as a smoking cue. As young adult women in particular are increasingly targeted by ENDS distributors, the present study examined whether passive exposure to the use of a female-marketed ENDS product selectively enhanced smoking urge, cigarette and e-cigarette desire, and smoking behavior among women (vs men) smokers.

Methods

Using a mixed design, young adult smokers (n=64; mean age 28.2 yrs; ≥5 cigarettes/day) observed a study confederate drink bottled water (control cue) and then vape a female-marketed tank-based ENDS (active cue). Main measures were the Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (BQSU) and visual analog scales (VAS) for cigarette and e-cigarette desire pre-and post-cue exposure, followed by a smoking latency task.

Results

Compared to the control cue, the female-marketed ENDS cue increased smoking urge and desire for cigarettes and e-cigarettes to a similar extent in women and men. It also affected subsequent smoking behavior similarly between the sexes, with 68% of men and 58% of women opting to smoke (vs. obtaining monetary reinforcers).

Conclusions

Both women and men were sensitive to the use of the female-marketed ENDS as a smoking cue. Consistent with prior work by our group, findings demonstrate the cue salience of ENDS, which may be attributable to the aspects of vaping that resemble traditional smoking (e.g. hand-to-mouth and inhalation and exhalation behaviors).

Keywords: electronic cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems, urge, cues, sex differences, vaping

Introduction

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS, or electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes) are hand-held devices that use a battery-powered heating element to aerosolize e-liquids containing nicotine and various other chemicals. Rates of ENDS use are at their highest levels since their inception, as over 1 in 3 U.S. adolescents (Kann et al., 2018; Miech et al., 2018) and nearly 1 in 4 young adults (18–24 years old; Bao et al., 2018) report having ever used an ENDS product.

In terms of sex differences, the prevalence of e-cigarette ever use is similar between women and men(Hartwell et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2019; Morning Consult, 2018). This narrow gender gap is unprecedented, as early adoption rates of new tobacco products have historically been higher among men vs women (American Lung Association, 2011; Garrett et al., 2011; Leon et al., 2016; Lipari and Van Horn, 2017; Rouse, 1989). Contributing to this phenomenon may be the marketing strategies implemented by ENDS distributors that normalize and glamorize vaping in women. Similar to the manufacturers of combustible cigarettes that developed the female-preferred pink or pastel packaging (Doxey and Hammond, 2011; Moodie et al., 2014) that contributed to the increased adoption of smoking among women, ENDS distributors have created products to appeal to women, such as pink and other brightly-colored devices and jeweled attachable charms (Yao et al., 2016). Feminine-appealing ENDS may represent a more salient cue to women passively exposed to others, particularly peers (Piñeiro et al., 2016), using the device.

Past research by our group has shown that passive exposure to the use of first, second and third generation ENDS increased observers’ desire to smoke at levels similar to that produced by a traditional cigarette cue. The ENDS cues across these studies were general ENDS products resembling a traditional cigarettes, pens/tools (vape pen), or automobile parts (tank-based mod) (King et al. 2015, 2016, 2018; Vena et al, 2019), and men and women observers showed similar cue reactivity to these exposures. However, ENDS designed to look and feel more comfortable to women may serve as a more potent cue in women than in men. Thus, the goal of the present study was to examine the cue salience of a specific female-marketed ENDS product relative to a neutral control cue in women and men. We hypothesized that women would be preferentially responsive to the cue and exhibit greater smoking desire and subsequent smoking behavior.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This mixed within- and between-subjects study was conducted between December 2017 and May 2018. Following screening and eligibility determination, participants were tested individually in a 1 ½−2 hour session consisting of a 50-minute cue exposure phase followed by a 50-minute smoking behavior task. In the cue phase, the participant engaged in two five-minute tasks with another participant (i.e., the study confederate) separated by a short rest break. The participant then took part in the smoking behavior phase, which was the latency portion of the Smoking Lapse Task (McKee et al, 2006). This component ascertained each participant’s ability to refrain from smoking versus obtain a monetary reinforcer. All sessions were conducted at the Clinical Addictions Research Laboratory at the University of Chicago and the study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Procedure

Candidates were recruited via online advertisements and flyers for a study about “moods, behaviors, and social interactions” to mask the study purpose, as in our prior studies (King et al., 2017, 2015; Vena et al., 2019). Inclusion criteria were age between 18–35 years, daily smoking (5–30 cigarettes per day), not currently attempting to quit smoking, fluent in English, and no major physical or mental disorders or disabilities (e.g., hearing or visual impairments) that would hinder participation. Participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol and recreational drugs for ≥24 hours and cigarette smoking for ≥1 hour before the visit. Screening consisted of informed consent, assessments of demographic, health, and substance use behaviors (for details, see Vena et al, 2019), verbal confirmation of recent abstinence, and breath tests for alcohol (BrAC=<.003) and carbon monoxide levels (as a general indicator to support self-reported time since last cigarette, i.e., <10ppm in those reporting no smoking for >3 hours prior to arrival).

Immediately following screening, eligible participants (65/67; 97% of those screened) started the session by completing baseline mood and craving surveys (see section 2.4). The participant and confederate were then introduced and each selected an envelope which they were told indicated one of five possible tasks: engaging in conversation, viewing pictures, eating, drinking, or smoking. Selection was fixed so that the participant always picked the task of engaging in conversation and the confederate always selected drinking water (control cue). Following this first 5-minute task, the participant completed surveys, engaged in a wash out task [the digit symbol substitution task (Wechsler, 1956)], and then had a short rest period. The participant and confederate reconvened for selection of their second 5-minute tasks that was also predetermined with the participant seemingly selecting engaging in conversation while the confederate seemingly selected vaping an e-cigarette (active cue) (see Vena et al., 2019). To ease the social interaction, a list of topics and conversation prompts were given to the participant (movies, vacations, etc.). After the second task, the participant completed surveys and the washout task, and then after a 15 minute break, completed the final set of surveys.

The final phase was the smoking latency task with the participant presented with a tray with a cigarette of his/her preferred brand, a lighter, and a doorbell. The participant was informed s/he could choose to either smoke the cigarette or receive $.20 for every five minutes of refraining (Pang and Leventhal, 2013). Each participant was told this phase would be 50 minutes regardless of their choice. The session ended after this phase and completion of the final survey to query participants on their estimate of the purpose of the study. Results showed that the majority of participants (98%, 63/64) were unaware that the purpose was to examine urge and desire responses to the vaping and water cues. Participants were paid $100 for participation with a full debriefing sent to them after the study was completed.

2.3. Cues

The control cue was bottled water (16.9 oz. clear plastic bottle) and chosen as a consummatory behavior but is neutral in terms of association to smoking (Drobes and Tiffany, 1997; King et al., 2017, 2015; Vena et al., 2019).The active cue was a hot pink-colored iStick Pico ENDS mod device adorned with a jeweled crown or bow charm (VaporDolls, Etsy). A pretesting survey in an independent sample of 191 men and women confirmed that 79% rated this device as feminine versus only 6% rating the standard black mod as feminine (King et al., unpublished data). The e-liquid used was identical to our prior work with 12 mg nicotine, 73% vegetable glycerin, 17% propylene glycol (Pace Engineering Concepts), and either menthol or tobacco flavor matched to each participant’s smoking preference.

The study confederate was a 26-year-old female (to enhance the ecological validity of this vaping device) of Middle Eastern descent with smoking and vaping experience. On end-of-session surveys, participants identified the confederate as likeable, friendly, and attractive, regardless of sex or sexual preference (p>0.08). The confederate was trained to ease the social interaction and deliver the control and active cues in a standard manner (e.g., 8–10 hand-to-mouth movements) for each five minute task period to mimic naturalistic vaping behavior (Etter & Eissenberg, 2015). Videotapes of the cue intervals were scored after the session and confirmed there were 8.5±2.0 (mean±SD) hand-to-mouth movements on average for both cues and a general positive social interaction for both task periods [3.1±0.6 on the 4-point positive valence subscale (Two-Dimensional Social Interaction Scale, Tse and Bond, 2001)], with no differences between the cue types on these measures.

2.4. Measures and Analyses

Primary dependent measures were 100mm visual analog scale (VAS) items of desire for a regular cigarette (preferred brand) and for an electronic cigarette (Heishman et al., 2010), and the 10-item Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (BQSU) total score (Cox et al., 2001). Additionally, 5 visual analog scale (VAS) items, e.g., desire for conversation, salty foods, etc. were imbedded in the surveys to mask the study purpose. The primary dependent variable from the smoking behavior phase was latency to smoke (in minutes), with values for persons who did not smoke (n=34/64) coded as 50 minutes.

Baseline-corrected change scores at the three times intervals [post-water cue, 5 minutes post-active cue, and final timepoint (20 minutes post-active cue)] were analyzed by Generalized Estimated Equations (GEE) with time as the within-subjects factor and participant sex as the between-subjects factor. These models included the baseline rating as a covariate, as high or low baseline scores can affect the magnitude of response. Analyses were also repeated with the inclusion of other possible covariates that may affect the main outcomes (Carpenter et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015), including smoking characteristics (cigarettes per day, expired air CO level), ENDS use [naïve, lifetime, or current (past month use)], and participant characteristics (race, sexual orientation). For smoking latency, the data were not normally distributed, so median values were examined and compared between the sexes via the Cox Hazard model, with the inclusion of the covariates listed above in the model.

3. Results

The sample consisted of 64 young adult smokers (52% female), with a mean age of 28.2±4.4 (SD) years (range 18–35 years). They averaged smoking 8.9 cigarettes per smoking day (range: 2–23) with a frequency of 6.9 days/week (range 4–7). Prior use of ENDS was common with 83% (53/64) of the sample reporting any vaping experience, of which 38% were current past month users (no participants vaped daily). The sexes did not differ on background or smoking characteristics or on their baseline subjective ratings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Group Characteristics

| Men (n=31) | Women (n=33) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and background: | |||

| Age (y) | 29.1 (0.7) | 27.4 (0.8) | p=0.10 |

| Education (y) | 13.7 (0.3) | 13.3 (0.3) | p=0.26 |

| Race: | p=0.99 | ||

| Caucasian | 12 (39%) | 13 (39%) | - |

| African American | 12 (39%) | 13 (39%) | - |

| Othera | 7 (22%) | 7 (22%) | - |

| Preference in Intimate/Romantic Partners: | p=0.23 | ||

| Opposite Sex | 24 (78%) | 21 (64%) | - |

| Same Sex or Both Sexes | 7 (22%) | 12 (36%) | - |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 6.2 (0.9) | 8.7 (1.4) | p=0.03 |

| Spielberger Trait Anxiety (t-score) | 45.22 (0.9) | 45.9 (0.8) | p=0.39 |

| Alcoholic drinks consumed/week | 11.0 (2.7) | 7.7 (1.2) | p=0.26 |

| Smoking patterns and use: | |||

| Days smoked (of past 28 days) | 27.5 (0.3) | 27.6 (0.2) | p=0.94 |

| Cigarettes smoked per smoking day | 9.4 (0.9) | 8.4 (0.7) | p=0.41 |

| FTND (nicotine dependency, 0–10) | 3.9 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.3) | p=0.70 |

| Hours since last reported cigaretteb | 2.6 | 1.8 | p=0.26 |

| CO (ppm)b | 8.0 | 11.0 | p=0.03 |

| Previous ENDS use: | p=0.13 | ||

| Naïve ENDS user (never used ENDS) | 8 (26%) | 3 (9%) | - |

| Lifetime ENDS user (no past month use) | 16 (52%) | 17 (52%) | - |

| Current ENDS user (past month use) | 7 (22%) | 13 (39%) | - |

| Other tobacco use in the past year: | |||

| Hookah | 7 (23%) | 13 (39%) | p=0.15 |

| Cigars | 17 (55%) | 16 (48%) | p=0.61 |

| Other (Smokeless, Pipe, Cloves, etc.) | 6 (19%) | 3 (9%) | p=0.21 |

| Baseline Urge and Desire Ratings | |||

| BQSU (range: 0–70) | 39.4 (1.4) | 42.5 (2.1) | p=0.22 |

| Regular Cigarette VAS (range: 0–100) | 61.1 (3.2) | 61.9 (4.1) | p=0.89 |

| E-cigarette VAS (range: 0–100) | 12 (3.6) | 16.4 (4.5) | p=0.45 |

Note. Values are Mean (SEM) or N (%), as indicated. Variables were compared between groups based on reported biological sex with Student’s t test, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test of independence, as appropriate.

Other racial category includes: American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and more than one race.

CO and Hours since last reported cigarette values are medians due to non-normal distribution, and compared via Mann-Whitney U test.

CO=Carbon Monoxide; ENDS=Electronic nicotine delivery systems; FTND=Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; BQSU=Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges.

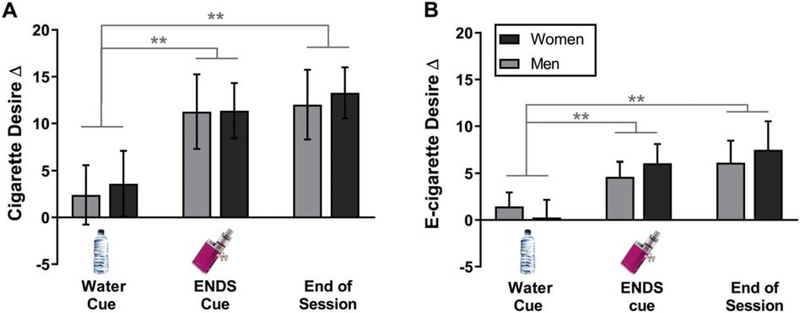

Exposure to the female-marketed ENDS increased desire for a cigarette (time: Waldχ2(2)=34.2, p<0.001), smoking urge (Waldχ2(2)=26.7, p<0.001), and desire for an e-cigarette (Waldχ2(2)=16.4, p<0.001) (Figure 1). Pairwise comparisons revealed that for all these outcomes, both the 5 and 20 minute ratings after the active cue were higher than after the control cue, ps<0.005). Both women and men were sensitive to the ENDS cue, with no main effects of sex (Waldχ2(1)≤0.10, ps>0.75) or interaction between sex and time (Waldχ2(2)≤2.55, ps>0.27).

Figure 1: Ratings of traditional cigarette and e-cigarette desire.

Data are Mean ± SEM. Subjective ratings of cigarette desire (A) and e-cigarette desire (B), represented as change scores from the baseline rating. The time points include following delivery of a water cue and the female-marketed ENDS cue, and at the end of session (20 minutes post-ENDS cue). **p<0.005 for main effect of time.

The majority of participants (63%) chose to smoke during the behavioral task. These rates of choosing to smoke are similar to prior work with cigarette and vape pen cues (King et al., 2018) and were comparable for women and men (58% vs. 68%; hazard ratio (95% CI) =1.27(0.64–2.54), p=0.50), but men had an overall shorter median latency [2.2 minutes (interquartile range: 0.02–50) vs 17.9 minutes for women (interquartile range: 5.4–50); p=0.045]. Including participant demographic (including education level and household income), smoking, and vaping characteristics as covariates did not change the aforementioned results.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to examine the salience of a female-marketed ENDS as a potential smoking cue. As with other ENDS products delivered as in-vivo (King et al., 2017, 2015; Vena et al., 2019) or video cues (Kim et al., 2015; King et al., 2016; Maloney and Cappella, 2016), the current study showed that, compared to a neutral cue, the feminine, bright pink ENDS device adorned with charms increased observers’ ratings of smoking urge and desire and produced a latency to smoke similar to that shown for both cigarettes and other e-cigarette products (King et al., 2017). Contrary to our hypothesis, men were as reactive to the feminine-oriented ENDS cue as women in terms of subjective (smoking and vaping desire ratings) and behavioral indices. In terms of the latter, despite similar proportions of the sexes choosing to smoke after the ENDS cue, the latency to smoke was shorter in men compared with women. This was unexpected and could relate to sex differences in the perceived value of a cigarette, impulsivity (Cross et al., 2011), or possible attraction to the novelty of the feminine ENDS device in men. These speculations would need further testing as they are outside the scope of the present study.

The strengths of the current study include the use of a well-controlled laboratory paradigm, repeated assessments, and methodological strategies to minimize expectancy. Despite these strengths, there are also some limitations worth noting. First, cues were presented in a fixed-order with the control cue preceding the active cue to eliminate potential cue reactivity carryover effects from the active cue. Potential temporal effects cannot be entirely ruled out as affecting outcomes, however, such effects are unlikely to be a major confound given that among young adult smokers averaging a half a pack of cigarettes a day, a twenty minute time difference, even following a short smoking abstinence, likely would not have produced large increases in smoking urge. Second, participants were young adult smokers and it is unknown if the findings would generalize to older or former smokers, or to sole e-cigarette users. Young adults were chosen because they report the highest prevalence of ENDS use and are more likely than older adults to be exposed to ENDS in their social environments (i.e. parties, school, social media, etc.) (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016; Glover et al., 2018; Pokhrel et al., 2018). While future research should consider cue reactivity research among adults who exclusively use ENDS, the prevalence of adult sole e-cigarette users is relatively low (1.4%; Mirbolouk et al., 2018; Thorndike, 2019). Third, similar to a prior study by our group (Vena et al., 2019), the vaping cue included a high level of VG in the e-liquid to create moderately visible aerosol clouds and the cue was delivered by a young adult female confederate. Thus, it is unknown if we would have observed the same responses if we employed a lower level of VG, which is associated with lower cue reactivity (Vena et al., 2019), or used a variety of persons as study confederates. For the latter point, secondary analyses revealed no effects of participants’ biological sex or sexual orientation on the main outcomes, so it is unlikely that the female confederate confounded examination of sex effects.

In sum, despite the feminine appearance of the ENDS mod used in the present study, both women and men exhibited cue reactivity on subjective smoking urge and smoking and vaping desire relative to the control cue, with latency to smoke similar to that previously observed with cigarette and vape pen cues (King et al., 2017). Considering these findings in the context of prior work by our group (King et al, 2015, 2016, 2017; Vena et al, 2019), the salient features of ENDS as a smoking cue appear to be independent of the device’s physical appearance and more likely a product of the associated features of vaping that mimic smoking, i.e., hand-to-mouth movements, inhalation/exhalation, and the expired aerosol resembling combustion. In terms of public health, the results underscore the need to examine effects of vaping beyond the user to consider effects on the observer. Feminine-oriented ENDS devices, targeted marketing strategies similar to those employed by the big tobacco industry (Keller, 2018), and online and magazine advertisements (Richardson et al., 2014) appealing to women’s preference may not only increase their use of e-cigarettes but also affect both women and men who are passively exposed to the use of these devices.

Highlights.

Ratings of smoking urge, cigarette desire, and e-cigarette desire were higher after presentation of an ENDS cue compared to after a neutral cue

Women and men had similar sensitivity to a female-marketed ENDS cue

The cue salience of ENDS may be independent of the device’s physical appearance

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is extended to Patrick McNamara for protocol assistance, Deena Sadek for research support, and Tony Pace, Pace Engineering Concepts, Milwaukee, WI for e-liquid preparation and quality control.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (R56-DA044210, R01-DA044210, T32-DA043469)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None Reported

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Lung Association, 2011. Trends in Tobacco Use. [Google Scholar]

- Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, 2018. Changes in Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States, 2014–2016. JAMA 319, 2039–2041. 10.1001/jama.2018.4658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Urman R, Chou CP, Howland S, Wang K, Pentz MA, Gilreath TD, Huh J, Leventhal AM, Samet JM, McConnell R, 2016. The E-cigarette Social Environment, E-cigarette Use, and Susceptibility to Cigarette Smoking. J. Adolesc. Heal. 59, 75–80. 10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, LaRowe SD, McClure EA, Simonian S, Upadhyaya HP, Gray KM, 2014. Craving, Cue Reactivity, and Stimulus Control Among Early-Stage Young Smokers: Effects of Smoking Intensity and Gender. Nicotine Tob. Res. 16, 208–215. 10.1093/ntr/ntt147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG, 2001. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob. Res. 3, 7–16. 10.1080/14622200020032051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross CP, Copping LT, Campbell A, 2011. Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 137, 97–130. 10.1037/a0021591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxey J, Hammond D, 2011. Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tob. Control 20, 353–60. 10.1136/tc.2010.038315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobes DJ, Tiffany ST, 1997. Induction of smoking urge through imaginal and in vivo procedures: physiological and self-report manifestations. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 106, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF, 2011. Cigarette Smoking - United States, 1965–2008, in: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report-United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Atlanta, GA, pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Glover LM, Ma JZ, Kesh A, Tompkins LK, Hart JL, Mattingly DT, Walker K, Robertson RM, Payne T, Sims M, 2018. The social patterning of electronic nicotine delivery system use among US adults. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 116, 27–31. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, Gilmore A, Petticrew M, 2017. E-cigarettes and equity: A systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob. Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Lee DC, Taylor RC, Singleton EG, 2010. Prolonged duration of craving, mood, and autonomic responses elicited by cues and imagery in smokers: Effects of tobacco deprivation and sex. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 18, 245–56. 10.1037/a0019401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier KA, 2018. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 67, 1–114. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K, 2018. Ads for E-Cigarettes Today Hearken Back to the Banned Tricks of Big Tobacco [WWW Document]. Smithsonian; URL https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/electronic-cigarettes-millennial-appeal-ushers-next-generation-nicotine-addicts-180968747/ (accessed 8.3.19). [Google Scholar]

- Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, Nonnemaker J, Makarenko O, 2015. Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob. Control 24, 132–135. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Smith LJ, Fridberg DJ, Matthews AK, McNamara PJ, Cao D, 2016. Exposure to electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) visual imagery increases smoking urge and desire. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 30, 106–12. 10.1037/adb0000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Smith LJ, McNamara PJ, Cao D, 2017. Second Generation Electronic Nicotine Delivery System Vape Pen Exposure Generalizes as a Smoking Cue. Nicotine Tob. Res. ntw327. 10.1093/ntr/ntw327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Smith LJ, McNamara PJ, Matthews AK, Fridberg DJ, 2015. Passive exposure to electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use increases desire for combustible and e-cigarettes in young adult smokers. Tob. Control 24, 501–504. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Kuguru KE, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2017. Gender Differences in U.S. Adolescent E-Cigarette Use. Curr. Addict. Reports 4, 422–430. 10.1007/s40429-017-0176-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon ME, Lugo A, Boffetta P, Gilmore A, Ross H, Schüz J, La Vecchia C, Gallus S, 2016. Smokeless tobacco use in Sweden and other 17 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 26, 817–821. 10.1093/eurpub/ckw032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, Van Horn SL, 2017. Trends in smokeless tobacco use and initiation: 2002 to 2014. The CBHSQ Report. Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney EK, Cappella JN, 2016. Does vaping in e-cigarette advertisements affect tobacco smoking urge, intentions, and perceptions in daily, intermittent, and former smokers? Health Commun. 31, 129–138. 10.1080/10410236.2014.993496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME, 2018. Adolescent Vaping and Nicotine Use in 2017–2018 — U.S. National Estimates. N. Engl. J. Med. NEJMc1814130. 10.1056/NEJMc1814130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirbolouk M, Charkhchi P, Kianoush S, Uddin SMI, Orimoloye OA, Jaber R, Bhatnagar A, Benjamin EJ, Hall ME, DeFilippis AP, Maziak W, Nasir K, Blaha MJ, 2018. Prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use among U.S. adults: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2016. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 429–438. 10.7326/M17-3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodie C, Bauld L, Ford A, Mackintosh AM, 2014. Young women smokers’ response to using plain cigarette packaging: qualitative findings from a naturalistic study. BMC Public Health 14, 812 10.1186/1471-2458-14-812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult, 2018. Percentage of adults in the U.S. who had tried vaping or using electronic cigarettes as of 2018, by gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/881837/vaping-and-electronic-cigarette-use-us-by-gender/ (accessed 12/26/18, 4:43 PM).

- Pang RD, Leventhal AM, 2013. Sex differences in negative affect and lapse behavior during acute tobacco abstinence: a laboratory study. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 21, 269–276. 10.1037/a0033429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro B, Correa JB, Simmons VN, Harrell PT, Menzie NS, Unrod M, Meltzer LR, Brandon TH, 2016. Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: Online survey results. Addict. Behav. 52, 91–97. 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Herzog TA, Laestadius L, Buente W, Kawamoto CT, Lee H-R, Unger JB, 2018. Social media e-cigarette exposure and e-cigarette expectancies and use among young adults. Addict. Behav. 78, 51–58. 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JL, Hammond D, Tariq U, Burkhalter R, Rynard VL, Douglas O, 2019. Tobacco Use in Canada: Patterns and Trends. Waterloo, ON. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Ganz O, Stalgaitis C, Abrams D, Vallone D, 2014. Noncombustible tobacco product advertising: How companies are selling the new face of tobacco. Nicotine Tob. Res. 16, 606–614. 10.1093/ntr/ntt200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse BA, 1989. Epidemiology of smokeless tobacco use: a national study. NCI Monogr. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike AN, 2019. E-Cigarette Use by Young Adult Nonsmokers: Next-Generation Nicotine Dependence? Ann. Intern. Med. 170, 70 10.7326/m18-2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse WS, Bond AJ, 2001. Development and validation of the Two-Dimensional Social Interaction Scale (2DSIS). Psychiatry Res. 103, 249–260. 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00271-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vena A, Howe M, Cao D, King A, 2019. The role of E-liquid vegetable glycerin and exhaled aerosol on cue reactivity to tank-based electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Psychopharmacology (Berl). 10.1007/s00213-019-05202-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 1956. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Psychological Corporation, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Yao T, Jiang N, Grana R, Ling PM, Glantz SA, 2016. A content analysis of electronic cigarette manufacturer websites in China. Tob. Control 25, 188–194. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]