Abstract

A series of compounds (including CCG-1423 and CCG-203971) discovered through an MRTF/SRF-dependent luciferase screen has shown remarkable efficacy in a variety of in vitro and in vivo models, including significant reduction of melanoma metastasis and bleomycin-induced fibrosis. Although these compounds are efficacious in these disease models, the molecular target is unknown. Here, we describe affinity isolation-based target identification efforts which yielded pirin, an iron-dependent cotranscription factor, as a target of this series of compounds. Using biophysical techniques including isothermal titration calorimetry and X-ray crystallography, we verify that pirin binds these compounds in vitro. We also show with genetic approaches that pirin modulates MRTF-dependent luciferase reporter activity. Finally, using both siRNA and a previously validated pirin inhibitor, we show a role for pirin in TGF-β-induced gene expression in primary dermal fibroblasts. A recently developed analog, CCG-257081, which cocrystallizes with pirin, is also effective in the prevention of bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis.

Keywords: pirin, CCG-203971, fibrosis, MRTF-A, TGF-β

Introduction

Myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF) and serum response factor (SRF) are transcription factors activated downstream of the Rho family of GTPases, which regulates actin cytoskeleton and motility.1,2 The MRTF/SRF complex activates a gene transcription program involved in the expression of structural and cytoskeletal genes, as well as pro-fibrotic genes regulated by a serum response element (SRE) in the promoter region.3 This mechanism feeds back on cell motility control and has been strongly implicated in cell migration and proliferation. Rho/MRTF/SRF signaling has also been linked to melanoma metastasis and to fibrotic pathological mechanisms.4,5 In 2007, we reported the first small molecule inhibitor of the Rho/MRTF/SRF pathway, CCG-1423.6 It was identified in a pathway screen using a modified MRTF-dependent serum response element (SRE.L) luciferase assay.6 CCG-1423 was shown to have antimigratory and antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer and melanoma cells in vitro.(6) It has been extensively used as an “MRTF inhibitor” in many biological contexts, including reduction of endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis7 and has efficacy in multiple preclinical disease models, including improvement of glycemic control of insulin-resistant mice8 and reduction of mouse peritoneal fibrosis.9

Subsequent chemical modification and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies based on the cell-based SRE.L-luciferase assay yielded the nipecotic acid derivatives CCG-100602 and CCG-203971,10,11 which removed the labile and potentially reactive N-alkoxybenzamide functionality of CCG-1423. These analogs improved tolerability in vivo and were shown to reduce bleomycin-induced skin and lung fibrosis12,13 and melanoma lung metastasis in two separate preclinical murine models.14 Further improvements to the series resulted in CCG-222740 and CCG-232601, which prevented ocular fibrosis and skin fibrosis in vivo.(15,16) Recent optimization for metabolic stability yielded CCG-257081, which has improved pharmacokinetic properties but it has not been tested in vivo (Figures 1A–D and 2C).16

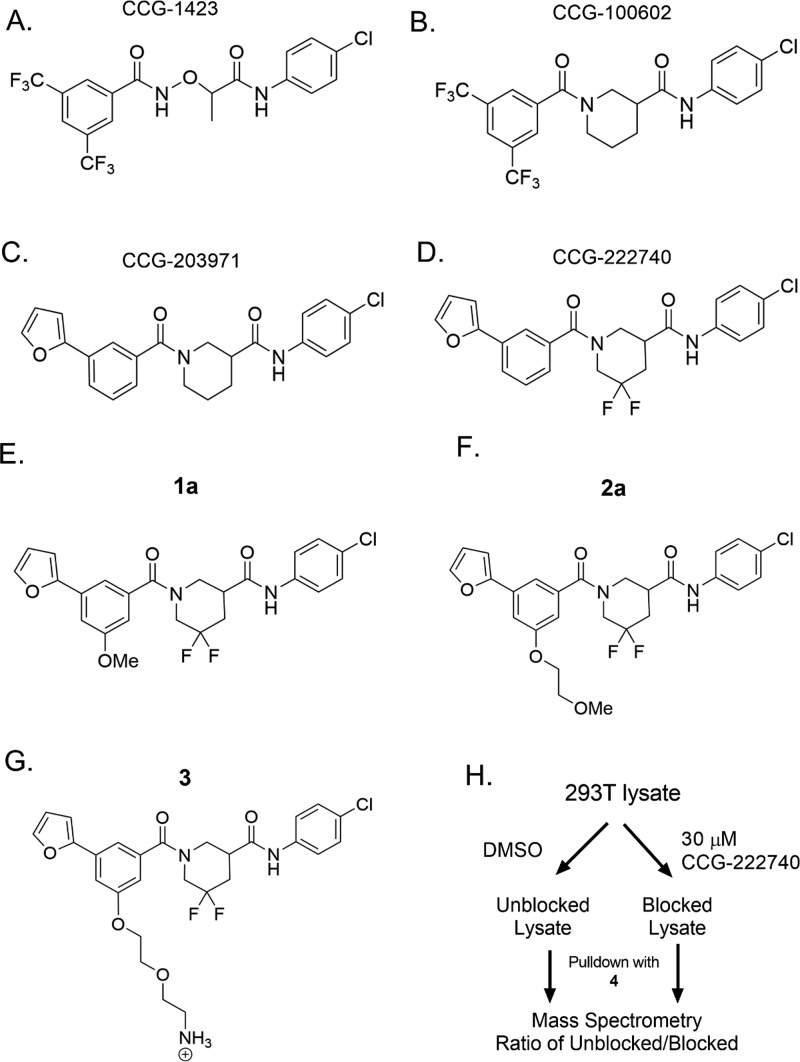

Figure 1.

Key analogs of the CCG series of Rho/MRTF/SRF-mediated gene transcription inhibitors and probe analogs. (A–D) Important analogs within the series that have led to the development of biologically active inhibitors. (E–G) Probe mimic analogs of CCG-222740 (1a and 2a) retained activity in Q231L Gα12 driven SRE.L luciferase (2 and 2.3 μM, respectively). On the basis of this activity, the 5-position of the 3-furyl aromatic ring was selected for PEG-linker attachment for NHS-agarose beads (3). (H) HEK 293T lysates were incubated with probe 4 bound to NHS beads, with or without preblocking lysates with 30 μM of CCG-222740. Proteins bound to the beads were then analyzed by mass spectrometry.

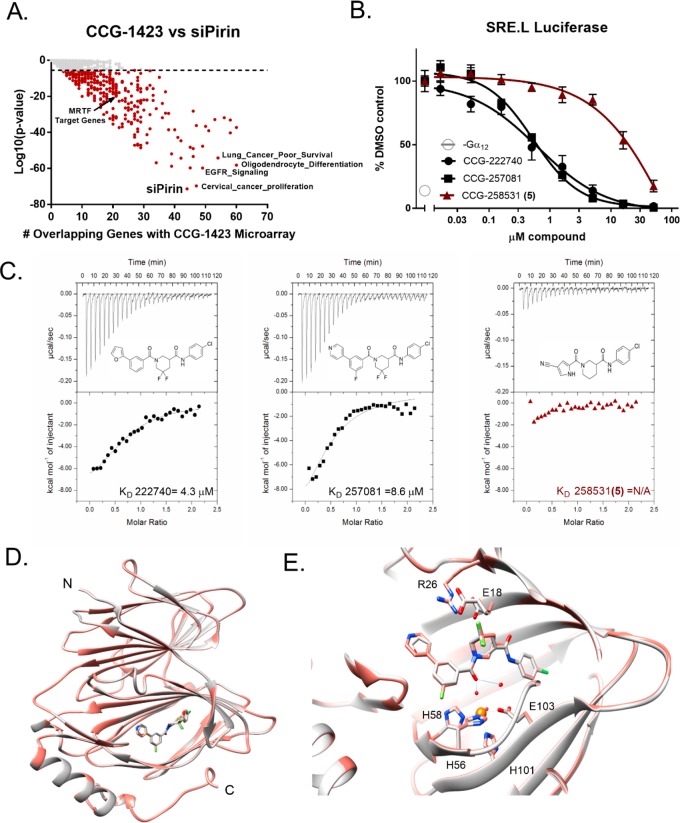

Figure 2.

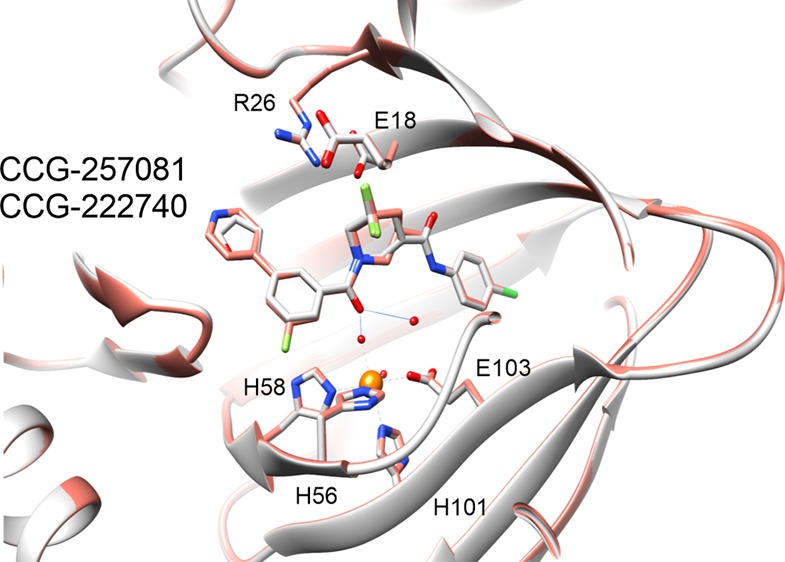

Pirin is a molecular target of CCG-222740 and CCG-257081. (A) Differential gene expression (based on fold change) was calculated for Pirin knockdown (GSE17551) and CCG-1423 treatment (GSE30188) and found to have high significance and an overlap of 44 genes in their data sets. (B) HEK293T cells cotransfected with Q231L Gα12 and a SRE.L luciferase reporter were treated with varying concentrations of CCG-222740, CCG-257081, or CCG-258531 (5). CCG-222740 and CCG-257081 inhibit Gα12 /Rho/MRTF mediated SRE.L luciferase much more potently than CCG-258531 (5). (C) Isotherm generated by ITC shows that CCG-222740 (left) and CCG-257081 (middle) have greater enthalpy changes upon binding to pirin, as compared to that of CCG-258531 (right), indicative of better binding to recombinant pirin. (D) Crystal structure overlap of pirin bound to CCG-222740 (gray), Protein Databank (PDB) code 6N0J, and CCG-257081 (salmon), PDB code 6N0K. (E) Detailed view of the compound binding pocket with overlaid CCG-222740 (gray) and CCG-257081 (salmon) pirin-bound structures. Also indicated is the metal ion (orange) as well as coordinating residues and water molecules (dashed lines), and hydrogen bonds (solid lines).

A major limitation to the development of this series of inhibitors has been the unknown molecular mechanism. Prior target identification campaigns for this series have been inconclusive. For instance, it has been reported that CCG-1423 can interact with the N-terminal nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in the RPEL domain of MRTF-A and block MRTF-A nuclear translocation by inhibition of the interaction between MRTF-A and importin α1/β1.17 CCG-1423 was also shown to bind directly to MICAL-2, an atypical intranuclear actin regulatory protein that mediates SRF/MRTF-A-dependent gene transcription.18 MICAL-2 is proposed to function by inducing redox-dependent depolymerization of nuclear actin, ultimately decreasing nuclear G-actin and increasing MRTF-A in the nucleus.18 Moreover, a photolysis photoprobe was synthesized and specifically labeled an approximate 24 kDa protein band in PC3 cells; however, the identity of the protein band was never validated by mass spectrometry.19 Finally, a microarray analysis of gene transcription changes in PC3 cells treated with CCG-1423 had significant overlap with effects of Latrunculin B, an actin polymerization inhibitor, as well as effects on cell cycle, ER stress and metastasis gene networks, suggesting shared biological targets between these two inhibitors.20

Despite multiple potential molecular targets for the series, there has been no robust biophysical evidence presented to validate these targets. Consequently, we undertook an unbiased mass spectrometry-based target identification approach and identified pirin, a conserved iron binding cotranscription factor that has not previously been associated with Rho/MRTF signaling or fibrosis, as the top biological target candidate for the series. Pirin was the most highly enriched protein upon affinity pulldown with an immobilized active compound. It was subsequently validated through various biophysical techniques, such as X-ray crystallography and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), which show that our compounds bind directly to pirin. Moreover, we show that pirin is involved in MRTF/SRF dependent pro-fibrotic signaling. Finally, we also report antifibrotic effects of CCG-257081 in a bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis model.

Results and Discussion

Identification of Pirin as a Potential Target of CCG-222740

To develop an affinity matrix for target enrichment, CGG-222740 was used as the starting chemical scaffold, mostly because of its superior inhibition of TGFβ-induced ACTA2 gene expression as compared to CCG-203971.16 To identify optimal linker placement, we performed a methoxy scan followed by an ethoxymethoxy scan on each aryl ring (Supplemental Table I). Taking into consideration the flat SAR, retained potency, efficacy, and availability of starting material, we chose to attach the PEG linker at the 5-position of the 3-furyl phenyl ring. Since attaching either small (1a) or large (2a) functional groups at that position did not markedly reduce activity (Supplemental Table I), we were confident that attaching the probe linker and resin there would allow for the probe to maintain acceptable binding affinity to the biological target(s) (Figure 1E–G). 3 was synthesized and linked to NHS-agarose beads using solid-phase amine coupling chemistry followed by blocking of residual reactive groups with ethanolamine to produce 4 (Supplementary Schemes 1–3), which was subsequently used as our affinity pulldown probe.

The agarose-bound probe was mixed with whole cell lysates from HEK-293T cells containing DMSO (unblocked) or 30 μM CCG-222740 (blocked) (Figure 1H). Beads were then washed several times with cold PBS (adapted from21). Pulldown mixtures were analyzed after trypsin digestion and subsequent proteomic analysis (see the Supporting Information). Comparison between the normalized peptide abundance in the DMSO control lysates and the CCG-222740 treated cell lysates revealed one protein that stood out with 5-fold greater peptide abundance in the DMSO control lysates and a p value of 1.3 e–13 (Table 1 and Supplemental Table II). Consistent with the known activity of our compounds to modulate gene transcription, it was encouraging that the enriched protein was a known cotranscription factor: pirin.

Table 1. List of Putative Targets for CCG-222740: Proteins with >2-Fold Enrichmenta.

| accession | description | peptide count | unique peptides | normalized unblocked/blocked beads | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIR_HUMAN | pirin | 4 | 3 | 4.98 | 1.32 × 10–13 |

| RBM4B_HUMAN; E9PLB0; E9PM61; U3KQD5 | RNA-binding protein 4B | 14 | 1 | 2.87 | 5.41 × 10–04 |

| CKAP4_HUMAN | cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | 2 | 1 | 2.85 | 1.28 × 10–04 |

| WAPL_HUMAN; Q8WVX6 | wings apart-like protein homologue | 6 | 3 | 2.69 | 2.44 × 10–05 |

| SNX4_HUMAN | sorting nexin-4 | 3 | 2 | 2.65 | 2.18 × 10–02 |

| RU1C_HUMAN; A0A0A0MRR7 | U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein C | 5 | 5 | 2.51 | 1.88 × 10–04 |

| PRPS1_HUMAN; B1ALA9 | ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1 | 3 | 1 | 2.46 | 4.68 × 10–03 |

| B4DWR3; PFD3_HUMAN | B4DWR3_HUMAN prefoldin subunit 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.22 | 2.81 × 10–02 |

| HSP72_HUMAN | heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 | 19 | 3 | 2.22 | 1.57 × 10–03 |

| CRIPT_HUMAN | cysteine-rich PDZ-binding protein | 2 | 1 | 2.21 | 1.80 × 10–05 |

| HSP76_HUMAN | heat shock 70 kDa protein 6 | 12 | 1 | 2.20 | 4.77 × 10–05 |

| CNBP_HUMAN | cellular nucleic acid-binding protein | 15 | 12 | 2.18 | 3.59 × 10–06 |

| PLSL_HUMAN | plastin-2 | 4 | 1 | 2.14 | 1.10 × 10–05 |

| RL38_HUMAN; J3KSP2; J3KT73; J3QL01 | 60S ribosomal protein L38 | 6 | 3 | 2.09 | 6.98 × 10–06 |

| K7EKX7; A0A087WT12; A0A087 × 2I2; A0A0A0MTT1; GPX4_HUMAN | K7EKX7_HUMAN glutathione peroxidase (fragment) | 6 | 4 | 2.08 | 1.09 × 10–04 |

| SYDC_HUMAN;H7C278 | aspartate–tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic | 4 | 3 | 2.07 | 1.07 × 10–05 |

| XPO2_HUMAN | exportin-2 | 10 | 5 | 2.06 | 1.49 × 10–03 |

| ZN706_HUMAN | zinc finger protein 706 | 2 | 2 | 2.05 | 1.71 × 10–06 |

| GSTP1_HUMAN;A0A087 × 2E9; A8MX94 | glutathione S-transferase P | 12 | 11 | 2.00 | 5.49 × 10–04 |

HEK 293T lysates were either blocked with 30 μM CCG-222740 or treated with DMSO as a control, and incubated with NHS-agarose bound CCG-262545. Peptides aligning with proteins and counts were compared in unblocked and blocked samples, and arranged in order of decrease in fold differences between the two samples. All protein samples with >2 fold differential peptide amounts are shown.

Pirin Binds to CCG-222740 and CCG-257081

Pirin is a well-conserved protein originally identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen with the transcription factor NF-1.22 A member of the cupin family of proteins,23 pirin has also been implicated in NF-κB signaling through its interaction with Bcl3, a NF-κB coactivator, and through direct interaction with a p65/p65 homodimer.24−26 Pirin is expressed ubiquitously, has been suggested to possess quercitinase activity23 and basal expression is, in part, regulated through Nrf2-regulated gene transcription.27 Two drug discovery campaigns have previously been described for pirin. The first published campaign used fluorescently labeled pirin to identify small molecules in an immobilized compound library that directly bound to pirin; however, the cellular effects of the identified compound, TphA, were modest.25 A second study identified the compound CCT251236 while screening for inhibitors of the heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) transcription pathway.28 Their target identification efforts yielded pirin as the target of CCT251236, which has efficacy in an ovarian cancer model in vivo and inhibits melanoma migration in vitro.(28) The structural comparison between CCT251236 and our series of Rho/MRTF/SRF-mediated gene transcription inhibitors reveals high similarity. This supports our initial rationalization of pirin as a biological target for our series of inhibitors.

To understand whether our series of compounds and pirin regulate a similar set of genes, we took a bioinformatics approach to compare a gene expression signature of CCG-1423 target genes found in PC3 prostate cancer cells20 with 12 922 MSigDB and several a priori derived gene sets which we generated from published microarray data (Supplemental Table V), including a pirin siRNA data set in WM266 melanoma cells. Only 347 (2.7%) of the gene sets showed a statistically significant correlation with the CCG-1423 regulated genes at the Bonferroni-corrected p value (p < 3.87 × 10–6). A siPirin gene set was the most significantly enriched (p = 4.44 × 10–72), with an overlap of 44 genes out of the top 100 differentially expressed genes with the CCG-1423 signature (Figure 2A and Supplemental Table IV). By comparison, the overlap between our entire in-house MRTF signature and the CCG-1423 gene signature was 21 genes (p = 5.01 × 10–20, Supplemental Table VI). Therefore, the bioinformatics analysis comparing the CCG-1423 microarray data set and the siPirin microarray data set was very encouraging and consistent with the idea that pirin may be a direct target of our compounds. Though it should be noted that these signatures were derived from different cell types, the fact that there is such a high degree of overlap suggests a conserved mechanism between pirin and CCG-1423. Despite this caveat, these data suggest that the CCG-1423 series of compounds may modulate pirin, and that only a portion of pirin-regulated transcription may involve MRTF.

To validate pirin as a molecular target, recombinant pirin was purified in order to test whether CCG-222740 and CCG-257081 engaged with pirin in vitro. As a comparison, we also tested CCG-258531 (5), a structurally related inhibitor that was nearly inactive in our Gα12 induced SRE.L luciferase assay (Figure 2B,C). Purified, recombinant pirin was used in isothermal titration calorimetery (ITC) experiments to determine the KD of our compounds. CCG-222740 and CCG-257081 bound to pirin with a KD of 4.3 and 8.5 μM, respectively. The change in enthalpy for the “inactive” compound CCG-258531 (5) was much less than that seen for either CCG-222740 or CCG-257081; it did not provide a reliable fit for binding analysis. Although this is a small set of compounds, it is encouraging to note that an inactive compound in our cell-based assay shows minimal binding to pirin in vitro (Figure 2C).

Furthermore, to understand how our small molecules bind to pirin, we solved high-resolution X-ray cocrystal structures of pirin in complex with CCG-222740 and CCG-257081 (1.7 and 1.5 Å, respectively) (Figure 2D). The two compounds bind very similarly, with the 4-chloroaniline projecting deep into the hydrophobic pocket and the furan/pyridine rings projecting out into solvent (Figure 2D,E). There are no direct contacts between the compound and the iron; the interaction is mostly mediated by hydrogen bonds with Fe-ligated waters (Figure 2E). When these compound-bound pirin cocrystal structures are compared to both the inactive (Fe2+ bound) and the active (Fe3+ bound) forms described in the literature, a high level of similarity exists. There is an overall RMSD (root-mean-square deviation) between 257081-bound pirin and Fe2+ bound pirin of 0.251 Å and between CCG-257081-bound pirin and Fe3+ bound pirin of 0.582 Å. Overall, these results support the idea that pirin is a molecular target of the CCG-222740 series of compounds.

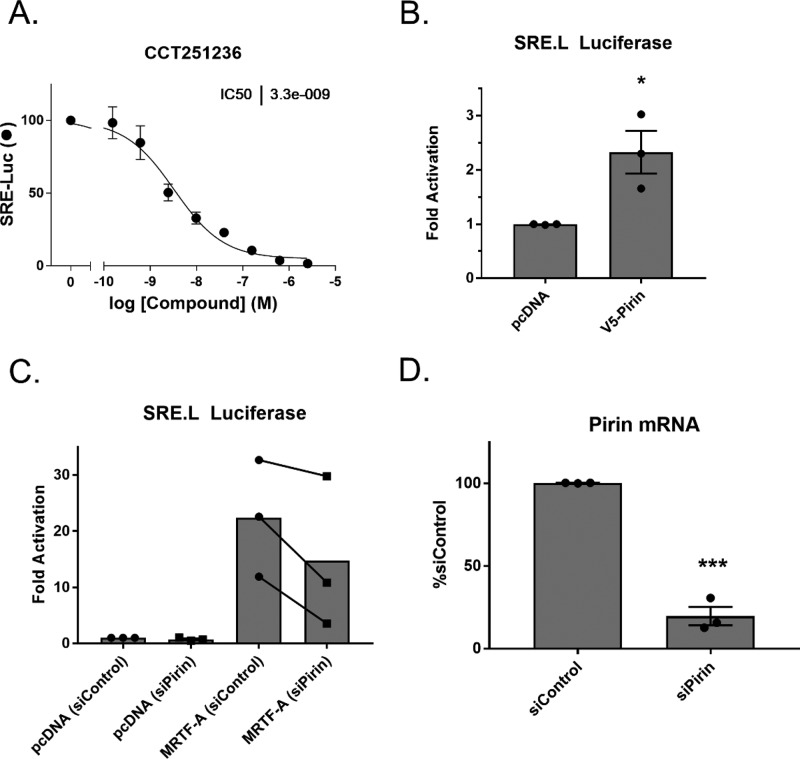

Modulation of Pirin Can Affect MRTF/SRF-Dependent SRE.L Luciferase

To explore the connection between pirin and MRTF/SRF signaling, a previously described pirin inhibitor, CCT251236,28 was tested in the Gα12 mediated SRE.L luciferase assay, the same assay used to discover CCG-1423. The SRE.L luciferase reporter contains several SRF binding sites that were modified to be dependent on MRTF but lack responsiveness to ETS factors.29 CCT251236 has nM potency in a cell-based assay to identify inhibitors of HSF1 transcription and binds to pirin in vitro with a KD of 44 nM as measured by SPR.28 CCT251236 had a remarkable effect on SRE.L luciferase expression, with an IC50 of 3.3 nM, without affecting luciferase catalytic activity directly (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 3). This pharmacologically validates pirin in the same Gα12 driven SRE.L luciferase assay that we used to discover and develop our series of compounds. To determine whether overexpression of pirin alone can modulate SRE.L-dependent luciferase, pirin was overexpressed in HEK293T cells with a SRE.L luciferase reporter. Pirin alone modestly increased SRE.L-driven luciferase expression, suggesting that pirin can enhance MRTF/SRF transcription (Figure 3B). Moreover, to determine whether reduction of pirin through siRNA could suppress MRTF-A-dependent SRE.L luciferase, primary human dermal fibroblasts were treated with a Dharmacon smartpool siRNA targeting pirin. Fibroblasts were used instead of HEK293T cells, due to a significant loss of cell viability upon silencing of pirin in HEK293T cells (data not shown). The MRTF-A-driven SRE.L luciferase signal was reduced when pirin mRNA levels were reduced by siRNA. This suggests that pirin modulates MRTF-A dependent gene transcription (Figure 3C,D). Taken together, these results support an interplay between pirin and MRTF- and SRF-driven luciferase transcription.

Figure 3.

Pirin interacts with the MRTF/SRF pathway. (A) CCT251236 inhibits Q231L Gα12 activated SRE.L luciferase in HEK293T cells; n = 2 (B) Overexpression of C-terminally V5 tagged pirin induces SRE.L luciferase signal in HEK293T cells. Luciferase signals were normalized to cell viability and the pcDNA control, and results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Individual means are represented by filled circles. *, p < 0.05 using an unpaired t test; n = 3 (C) Knockdown of pirin also reduces MRTF-A driven SRE.L luciferase in primary dermal fibroblasts after overexpression of MRTF-A. Luciferase signals were normalized to cell viability and the pcDNA siControl, and results are expressed as the overall mean as well as individual paired mean values. n = 3. (D) Validation of pirin knockdown using qPCR. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM as well as individual mean values ***, p < 0.001 using an unpaired t test; n = 3.

Inhibition or Ablation of Pirin Reduces TGF-β-Induced Profibrotic Gene Expression

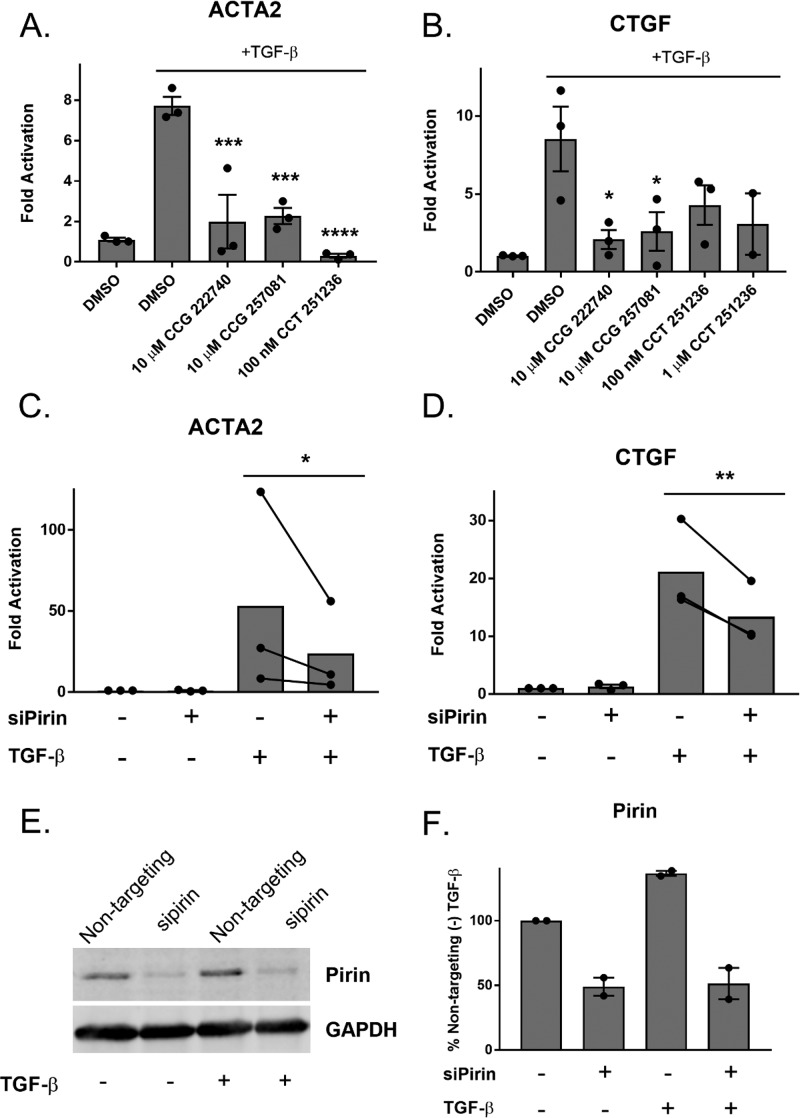

The CCG-203971/CCG-222740 series is known to inhibit pro-fibrotic signaling and a large body of literature exists that suggests this is through MRTF/SRF.12,15,30,31 TGF-β signaling has been shown to activate Rho and MRTF/SRF gene transcription through a noncannonical pathway.4 However, to pharmacologically verify that pirin is involved in TGF-β dependent gene expression, we used CCT251236, the previously described pirin inhibitor.28 Human primary dermal fibroblasts were activated with TGF-β for 24 h with or without CCG-222740 or CCG-257081 as well as CCT251236. All three compounds significantly reduced TGF-β-induced ACTA2 expression (Figure 4A). ACTA2 is the gene for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), which is a marker of myofibroblast transition and a direct target of MRTF/SRF-mediated transcription.31 In addition, we tested these compounds against CTGF expression (CCN2). CTGF is a pro-fibrotic mediator that is also partly regulated by MRTF/SRF.5 We also observed a decrease in CTGF mRNA levels after compound treatment (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Inhibition or ablation of pirin reduces TGF-β-dependent gene expression. (A) Primary dermal fibroblasts from healthy donors were treated with TGF-β and either vehicle control, CCG compounds, or CCT251236. Levels of ACTA2 mRNA were measured by qPCR. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM as well as individual mean values. ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001 using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test as compared to the (+)TGF-β sample ; n = 3 (B). Similarly, CTGF mRNA levels were measured after treatment with TGF-β and pirin inhibitors. Results are expressed as the overall mean ± SEM *, p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test as compared to (+) TGF-β; n = 3, except for the 1 μM CCT 251236 condition, which is n = 2. (C) Pirin knockdown reduces TGF-β stimulated ACTA2 mRNA levels in human primary dermal fibroblasts. Results are expressed as the mean as well as individual paired mean values; n = 3. p < 0.05 using a ratio paired t test. Nontargeting siRNA was used in siPirin (−) conditions. (D) Pirin knockdown reduces TGF-β stimulated CTGF mRNA levels. Primary dermal fibroblasts were treated similarly to C. The results are expressed as the overall mean as well as individual paired mean values from three independent experiments (**, p < 0.01). (E) Western blot of pirin protein after siRNA treatment. (F) Quantification of E. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of two independent experiments.

To further confirm that pirin is involved in TGF-β-mediated gene expression, we reduced pirin expression through siRNA. Knockdown of pirin led to a 50% decrease in TGF-β-induced ACTA2 and CTGF mRNA, further verifying the role of pirin in TGF-β-mediated gene expression (Figure 4C,D). Pirin mRNA levels were reduced 80% in primary dermal fibroblasts after siRNA treatment (Supplemental Figure 4), and protein amounts were reduced by approximately 50% (Figure 4E,F)

Modulation of Pirin Affects TGF-β Signaling and MRTF-A Localization

We have now shown that modulation of pirin and previously described pirin-binding compounds can reduce TGF-β-regulated gene expression. To further explore the connection between pirin and TGF-β signaling, we determined how modulation of pirin through treatment with CCG-257081 or shRNA against pirin affected TGF-β-induced phospho-SMAD2 (p-SMAD2) levels, a primary downstream effector of TGF-β1 receptors.32 Primary dermal fibroblasts were cotreated with 10 μM CCG-257081 and TGF-β for 24 h or pretreated with CCG-257081 and stimulated with TGF-β for 60 min (Figure 5A and Supplemental Figure 6A). We observed that CCG-257081 markedly reduced p-SMAD2 levels as compared to those with DMSO control. We then tested whether ablation of pirin through shRNA affected TGF-β-induced p-SMAD2. We also observed a reduction in p-SMAD2 in the cells expressing shRNA against pirin, although it is unclear whether this is due to reduced total SMAD2 protein levels (Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 6B,C). Furthermore, it has been shown previously that CCG-1423 can reduce TGF-β-induced MRTF-A localization in primary dermal fibroblasts.33 We observed that 24 h after TGF-β stimulation, the percentage of cells with exclusively nuclear MRTF-A is reduced in cells expressing shRNA against pirin compared to shLacZ control cells, suggesting that pirin plays a role in TGF-β-directed MRTF-A localization (Figure 5C,D). Taken together, it appears that modulation of pirin, either through compound binding or silencing through shRNA can reduce SMAD2 phosphorylation as well as MRTF-A nuclear accumulation.

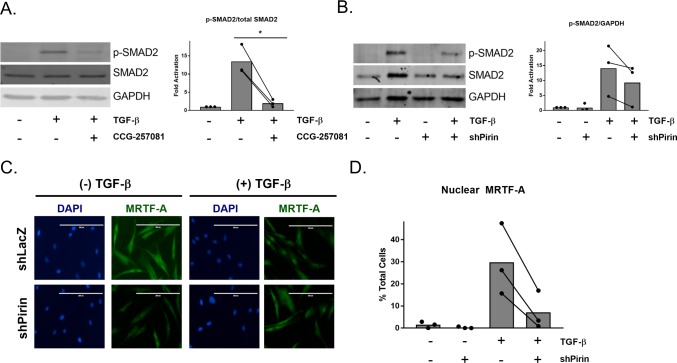

Figure 5.

CCG-257081 and modulation of pirin decrease SMAD2 phosphorylation and MRTF-A nuclear localization. (A) Left panel: Representative Western blot of p-SMAD2, total SMAD2, and GAPDH of lysates from primary human primary dermal fibroblasts after cotreatment with 10 μM CCG-257081 and 10 ng/mL TGF-β for 24 h. Right panel: Quantification of left panel. The results are expressed as the overall mean as well as mean values from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 using a ratio paired t test. (B) Human primary dermal fibroblasts were infected with virus containing shRNA against LacZ (shPirin −) or Pirin (shPirin +). Cells were then treated with 10 ng/mL TGF-β for 24 h, and Western blotting was performed for p-SMAD2, total SMAD2, and GAPDH. Right panel: quantification of left panel. Bars represent overall mean with paired independent means, n = 3. (C) Cells infected with shLacZ or shPirin were plated in 8-well chamber slides and then were treated with 10 ng/mL TGF-β in 0.5% FBS+DMEM and stained for endogenous MRTF-A. Scale bar represents 200 μm. (D) Quantification of (C) with the percentage of total cells with exclusively nuclear MRTF-A, n = 3. The overall mean is shown (bars). Total number of cells counted in each experimental condition was >200.

CCG-257081 Prevents Bleomycin-Induced Skin Fibrosis

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is an autoimmune disease that leads to overproduction of collagen, primarily from fibroblasts that have transitioned to myofibroblasts after exposure to several cytokines, including TGF-β.34 Although pirin has not been previously been implicated in fibrosis or TGF-β signaling, pirin has been proposed to be a marker of hepatic stellate cell myofibroblasts, as it was found to be overexpressed in these cells as compared to portal myofibroblasts by a proteomic approach.35 One mouse model of scleroderma is bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis, which recapitulates several aspects of scleroderma, including inflammation, activation of fibroblasts, production of collagen, and the presence of autoantibodies specific to scleroderma.36 We have previously shown that CCG-20397112 and CCG-23260116 can prevent bleomycin-induced fibrosis in mice. However, the most recently developed compound in this series and one that we show binds to pirin in this manuscript, CCG-257081, which has improved pharmacokinetics has not yet been shown to reduce bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in vivo.(16) Therefore, CCG-257081 was tested in a bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis prevention model in mice. Fibrosis was induced with daily bleomycin injections and mice were treated with CCG-257081 (50 mg/kg/day by oral gavage) for 14 days. At the conclusion of the experiment, mice were sacrificed and the skin paraffin-embedded. Tissue slices were used for histological analysis by Masson’s trichrome staining. As shown in Figure 6, treatment of mice with CCG-257081 significantly reduced skin thickening and total collagen content.

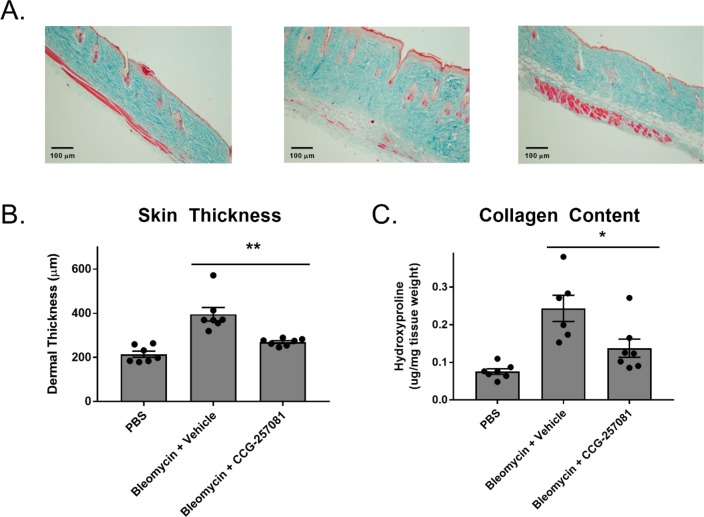

Figure 6.

CCG-257081 prevents bleomycin-induced fibrosis. Mice treated daily with 50 mg/kg CCG-257081 had significantly reduced skin thickness as compared to vehicle control. (A) Masson’s trichrome stained skin sections from vehicle-treated mice (left panel) bleomycin-treated mice (middle panel) and bleomycin+CCG-257081-treated mice (right panel). N = 7. (B) Quantification of (A) by measuring the maximal distance between the epidermal–dermal junction and the dermal-subcutaneous fat junction. Mean values ± SEM are displayed as bar graphs as well as individual values (circles) are displayed. **, p < 0.01 using an unpaired t test. (C) Quantification of collagen using hydroxyproline measurements. Mean values ± SEM (bar graphs) as well as individual mean values (circles) are displayed. *, p < 0.05 using an unpaired t test.

The CCG-series of compounds has been published in many papers and has demonstrated efficacy in a wide range of disease models. Although these compounds were originally identified in a cell-based luciferase assay that relied on MRTF/SRF-regulated gene transcription, no molecular target was fully validated. Our own preliminary work also showed that our series of compounds did not inhibit an actin:MRTF interaction (Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that the RPEL domain of MRTF was not a direct target of these compounds.17 In this study, we describe the identification and validation of pirin as one molecular target of CCG-222740 and CCG-257081, although it is possible that these compounds yield their biological effects through multiple molecular targets, including those that have already been described.17,18

Further work will yield insights into the biology of pirin and how it relates to the MRTF/SRF signaling pathway and pro-fibrotic mechanisms. Pirin has been implicated in melanoma migration and progression25,37,38 but has not been explored in terms of fibrotic disease. This is the first report implicating pirin in a pro-fibrotic signaling pathway, so dissecting the exact role of pirin in TGF-β mechanisms will be an important question to address. Our results show that modulation of pirin through either binding to CCG-257081 or through shRNA reduce TGF-β-induced p-SMAD2 levels suggesting a connection between pirin and TGF-β signaling. It is still unclear whether there is a direct physical interaction between pirin and SMAD proteins or the TGF-β receptor itself. Moreover, pirin has been shown to interact with several different proteins and signaling pathways, including direct interactions with NF-κB26 and Bcl-324 and modulation of the HSF-1 pathway.28 Therefore, by modulation of pirin though binding of our CCG compounds, we may be affecting multiple pathways, as well as genes involved in the cell cycle, which constitute a large portion of overlapping genes between the CCG-1423 and siPirin data sets (Supplemental Table IV).

The exact mechanism of compound effects on pirin activity is also unknown. It is possible that these compounds stabilize either an oxidized or reduced form of pirin and therefore affect the ability of pirin to bind to coactivators or transcription factors. It has been shown that only Fe3+-bound pirin will bind to p65, whereas Fe2+ bound will not.26 Also, CCG-1423 has been shown to displace MRTF-A and SRF from the ACTA2 promoter39 which suggests that compound binding to pirin may disrupt a pirin/MRTF-A/SRF/DNA complex. Our own preliminary work has not shown any evidence of direct binding of pirin to MRTF or SRF (data not shown), but we cannot eliminate this possibility. Future work will address these and other questions, including exploring the implications of pirin modulation on global measures of gene transcription.

Materials and Methods

For materials and methods, see the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH NIAMS award R01AR066049 (SDL) and NIH NIGMS award R01GM115459 (RRN). I.G. was supported by the Spartan Innovation Fund. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package. Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsptsci.8b00048.

Coomassie gel of recombinant His-pirin, CCG-257081 bound pirin is similar to inactive pirin, CCG-222740 and CCT251236 have minimal effects on recombinant luciferase activity, pirin mRNA is reduced in siPirin primary dermal fibroblasts, CCG-203971 does not disrupt the MRTFA-RPEL:actin interaction, CCG compounds and pirin affect the TGF-β signaling pathway, exemplary probe development SAR, data collection and refinement statistics, overlap between CCG-1423 and siPirin microarray gene sets, intersection between CCG-1423 and MRTF gene signatures, materials and methods (PDF)

Proteomic results, gene signatures tested and overlap with CCG-1423 gene signature (XLSX)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Drs. Neubig and Larsen are founders and officers of FibrosIX Inc. which has licensed the rights to CCG-257081 and related compounds.

This article is made available for a limited time sponsored by ACS under the ACS Free to Read License, which permits copying and redistribution of the article for non-commercial scholarly purposes.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hill C. S.; Wynne J.; Treisman R. (1995) The Rho family GTPases RhoA, Rac1, and CDC42Hs regulate transcriptional activation by SRF. Cell 81 (7), 1159–70. 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E. N.; Nordheim A. (2010) Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 (5), 353–65. 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualdrini F.; Esnault C.; Horswell S.; Stewart A.; Matthews N.; Treisman R. (2016) SRF Co-factors Control the Balance between Cell Proliferation and Contractility. Mol. Cell 64 (6), 1048–1061. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou P. S.; Haak A. J.; Khanna D.; Neubig R. R. (2014) Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 8. Current and future drug targets in fibrosis: focus on Rho GTPase-regulated gene transcription. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol. 307 (1), C2–13. 10.1152/ajpcell.00060.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medjkane S.; Perez-Sanchez C.; Gaggioli C.; Sahai E.; Treisman R. (2009) Myocardin-related transcription factors and SRF are required for cytoskeletal dynamics and experimental metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 11 (3), 257–68. 10.1038/ncb1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn C. R.; Wade S. M.; Wang Q.; Wu M.; Iniguez-Lluhi J. A.; Merajver S. D.; Neubig R. R. (2007) CCG-1423: a small-molecule inhibitor of RhoA transcriptional signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 6 (8), 2249–60. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau D.; Veon W.; Capasso T. L.; Bottcher R.; Shroff S.; Roman B. L.; Roy P. (2017) Pharmacological intervention of MKL/SRF signaling by CCG-1423 impedes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 20 (4), 663–672. 10.1007/s10456-017-9560-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W.; Goldfine A. B.; Boes T.; Henry R. R.; Ciaraldi T. P.; Kim E. Y.; Emecan M.; Fitzpatrick C.; Sen A.; Shah A.; Mun E.; Vokes V.; Schroeder J.; Tatro E.; Jimenez-Chillaron J.; Patti M. E. (2011) Increased SRF transcriptional activity in human and mouse skeletal muscle is a signature of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 121 (3), 918–29. 10.1172/JCI41940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai N.; Chun J.; Duffield J. S.; Wada T.; Luster A. D.; Tager A. M. (2013) LPA1-induced cytoskeleton reorganization drives fibrosis through CTGF-dependent fibroblast proliferation. FASEB J. 27 (5), 1830–46. 10.1096/fj.12-219378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn C. R.; Bell J. L.; Ryu J. G.; Wade S. M.; Kocab A.; Harzdorf N. L.; Hollis Showalter H. D.; Neubig R. R.; Larsen S. D. (2010) Design, synthesis and prostate cancer cell-based studies of analogs of the Rho/MKL1 transcriptional pathway inhibitor, CCG-1423. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20 (2), 665–72. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. L.; Haak A. J.; Wade S. M.; Kirchhoff P. D.; Neubig R. R.; Larsen S. D. (2013) Optimization of novel nipecotic bis(amide) inhibitors of the Rho/MKL1/SRF transcriptional pathway as potential anti-metastasis agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23 (13), 3826–32. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.04.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak A. J.; Tsou P. S.; Amin M. A.; Ruth J. H.; Campbell P.; Fox D. A.; Khanna D.; Larsen S. D.; Neubig R. R. (2014) Targeting the myofibroblast genetic switch: inhibitors of myocardin-related transcription factor/serum response factor-regulated gene transcription prevent fibrosis in a murine model of skin injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 349 (3), 480–6. 10.1124/jpet.114.213520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson T. H.; Ajayi I. O.; Subbotina N.; Dodi A. E.; Rodansky E. S.; Chibucos L. N.; Kim K. K.; Keshamouni V. G.; White E. S.; Zhou Y.; Higgins P. D.; Larsen S. D.; Neubig R. R.; Horowitz J. C. (2015) Inhibition of myocardin-related transcription factor/serum response factor signaling decreases lung fibrosis and promotes mesenchymal cell apoptosis. Am. J. Pathol. 185 (4), 969–86. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak A. J.; Appleton K. M.; Lisabeth E. M.; Misek S. A.; Ji Y.; Wade S. M.; Bell J. L.; Rockwell C. E.; Airik M.; Krook M. A.; Larsen S. D.; Verhaegen M.; Lawlor E. R.; Neubig R. R. (2017) Pharmacological Inhibition of Myocardin-related Transcription Factor Pathway Blocks Lung Metastases of RhoC-Overexpressing Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16 (1), 193–204. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Wai-Man C.; Spencer-Dene B.; Lee R. M.; Hutchings K.; Lisabeth E. M.; Treisman R.; Bailly M.; Larsen S. D.; Neubig R. R.; Khaw P. T. (2017) Local delivery of novel MRTF/SRF inhibitors prevents scar tissue formation in a preclinical model of fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 518. 10.1038/s41598-017-00212-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings K. M.; Lisabeth E. M.; Rajeswaran W.; Wilson M. W.; Sorenson R. J.; Campbell P. L.; Ruth J. H.; Amin A.; Tsou P. S.; Leipprandt J. R.; Olson S. R.; Wen B.; Zhao T.; Sun D.; Khanna D.; Fox D. A.; Neubig R. R.; Larsen S. D. (2017) Pharmacokinetic optimitzation of CCG-203971: Novel inhibitors of the Rho/MRTF/SRF transcriptional pathway as potential antifibrotic therapeutics for systemic scleroderma. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27 (8), 1744–1749. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K.; Watanabe B.; Nakagawa Y.; Minami S.; Morita T. (2014) RPEL proteins are the molecular targets for CCG-1423, an inhibitor of Rho signaling. PLoS One 9 (2), e89016 10.1371/journal.pone.0089016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist M. R.; Storaska A. J.; Liu T. C.; Larsen S. D.; Evans T.; Neubig R. R.; Jaffrey S. R. (2014) Redox modification of nuclear actin by MICAL-2 regulates SRF signaling. Cell 156 (3), 563–76. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. L.; Haak A. J.; Wade S. M.; Sun Y.; Neubig R. R.; Larsen S. D. (2013) Design and synthesis of tag-free photoprobes for the identification of the molecular target for CCG-1423, a novel inhibitor of the Rho/MKL1/SRF signaling pathway. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 9, 966–73. 10.3762/bjoc.9.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn C. R.; Lisabeth E. M.; Wade S. M.; Haak A. J.; Johnson C. N.; Lawlor E. R.; Neubig R. R. (2016) Small-Molecule Inhibition of Rho/MKL/SRF Transcription in Prostate Cancer Cells: Modulation of Cell Cycle, ER Stress, and Metastasis Gene Networks. Microarrays 5, 13 10.3390/microarrays5020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davda D.; El Azzouny M. A.; Tom C. T.; Hernandez J. L.; Majmudar J. D.; Kennedy R. T.; Martin B. R. (2013) Profiling targets of the irreversible palmitoylation inhibitor 2-bromopalmitate. ACS Chem. Biol. 8 (9), 1912–7. 10.1021/cb400380s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler W. M.; Kremmer E.; Forster R.; Winnacker E. L. (1997) Identification of pirin, a novel highly conserved nuclear protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272 (13), 8482–9. 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M.; Jia Z. (2005) Structural and biochemical analysis reveal pirins to possess quercetinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280 (31), 28675–82. 10.1074/jbc.M501034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechend R.; Hirano F.; Lehmann K.; Heissmeyer V.; Ansieau S.; Wulczyn F. G.; Scheidereit C.; Leutz A. (1999) The Bcl-3 oncoprotein acts as a bridging factor between NF-kappaB/Rel and nuclear co-regulators. Oncogene 18 (22), 3316–23. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki I.; Simizu S.; Okumura H.; Takagi S.; Osada H. (2010) A small-molecule inhibitor shows that pirin regulates migration of melanoma cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6 (9), 667–73. 10.1038/nchembio.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; Rehmani I.; Esaki S.; Fu R.; Chen L.; de Serrano V.; Liu A. (2013) Pirin is an iron-dependent redox regulator of NF-kappaB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (24), 9722–7. 10.1073/pnas.1221743110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzoska K.; Stepkowski T. M.; Kruszewski M. (2014) Basal PIR expression in HeLa cells is driven by NRF2 via evolutionary conserved antioxidant response element. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 389 (1–2), 99–111. 10.1007/s11010-013-1931-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman M. D.; Chessum N. E.; Rye C. S.; Pasqua A. E.; Tucker M. J.; Wilding B.; Evans L. E.; Lepri S.; Richards M.; Sharp S. Y.; Ali S.; Rowlands M.; O’Fee L.; Miah A.; Hayes A.; Henley A. T.; Powers M.; Te Poele R.; De Billy E.; Pellegrino L.; Raynaud F.; Burke R.; van Montfort R. L.; Eccles S. A.; Workman P.; Jones K. (2017) Discovery of a Chemical Probe Bisamide (CCT251236): An Orally Bioavailable Efficacious Pirin Ligand from a Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1 (HSF1) Phenotypic Screen. J. Med. Chem. 60 (1), 180–201. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. S.; Wynne J.; Treisman R. (1994) Serum-regulated transcription by serum response factor (SRF): a novel role for the DNA binding domain. EMBO J. 13 (22), 5421–32. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider B. J.; Risinger G. M. Jr.; Haaksma C. J.; Howard E. W.; Tomasek J. J. (2011) Myocardin-related transcription factors A and B are key regulators of TGF-beta1-induced fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131 (12), 2378–85. 10.1038/jid.2011.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speight P.; Kofler M.; Szaszi K.; Kapus A. (2016) Context-dependent switch in chemo/mechanotransduction via multilevel crosstalk among cytoskeleton-regulated MRTF and TAZ and TGFbeta-regulated Smad3. Nat. Commun. 7, 11642. 10.1038/ncomms11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. H.; Chen D. Q.; Wang Y. N.; Feng Y. L.; Cao G.; Vaziri N. D.; Zhao Y. Y. (2018) New insights into TGF-beta/Smad signaling in tissue fibrosis. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 292, 76–83. 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiwen X.; Stratton R.; Nikitorowicz-Buniak J.; Ahmed-Abdi B.; Ponticos M.; Denton C.; Abraham D.; Takahashi A.; Suki B.; Layne M. D.; Lafyatis R.; Smith B. D. (2015) A Role of Myocardin Related Transcription Factor-A (MRTF-A) in Scleroderma Related Fibrosis. PLoS One 10 (5), e0126015 10.1371/journal.pone.0126015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allanore Y.; Simms R.; Distler O.; Trojanowska M.; Pope J.; Denton C. P.; Varga J. (2015) Systemic sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis Primers. 1, 15002. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosselut N.; Housset C.; Marcelo P.; Rey C.; Burmester T.; Vinh J.; Vaubourdolle M.; Cadoret A.; Baudin B. (2010) Distinct proteomic features of two fibrogenic liver cell populations: hepatic stellate cells and portal myofibroblasts. Proteomics 10 (5), 1017–28. 10.1002/pmic.200900257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni R. G.; Varga J.; Tourtellotte W. G. (2016) Animal models of scleroderma: recent progress. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 28 (6), 561–70. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licciulli S.; Luise C.; Scafetta G.; Capra M.; Giardina G.; Nuciforo P.; Bosari S.; Viale G.; Mazzarol G.; Tonelli C.; Lanfrancone L.; Alcalay M. (2011) Pirin inhibits cellular senescence in melanocytic cells. Am. J. Pathol. 178 (5), 2397–406. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licciulli S.; Luise C.; Zanardi A.; Giorgetti L.; Viale G.; Lanfrancone L.; Carbone R.; Alcalay M. (2010) Pirin delocalization in melanoma progression identified by high content immuno-detection based approaches. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 5. 10.1186/1471-2121-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C. T.; Gualdrini F.; Treisman R. (2017) Mutual dependence of the MRTF-SRF and YAP-TEAD pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts is indirect and mediated by cytoskeletal dynamics. Genes Dev. 31 (23–24), 2361–2375. 10.1101/gad.304501.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.