Abstract

With water and sanitation vital to the public’s health, there have been growing calls to accept water and sanitation as a human right and establish a rights-based framework for water policy. Through the development of international law, policymakers have increasingly specified water and sanitation as independent human rights. In this political development of human rights for water and sanitation, the authors find that the evolution of rights-based water and sanitation policy reached a milestone in the United Nations (UN) General Assembly’s 2010 Resolution on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation. By memorializing international political recognition of these interconnected rights and the corresponding obligations of national governments, states provided a normative framework for expanded efforts to realize human rights through water and sanitation policy. Examining the opportunities created by this UN Resolution, this article analyzes the implementation of the human right to water and sanitation through global water governance, national water policy and water and sanitation outcomes. While obstacles remain in the implementation of this right, the authors conclude that the UN Resolution could have lasting benefits for public health.

Keywords: Global water governance, Human rights, Human rights indicators, United Nations, Water and sanitation policy

1. Introduction

As human rights expand in scope and influence, water and sanitation – both instrumental to the realization of a wide range of human rights – have come to be seen as a distinct, composite human right. The United Nations (UN) General Assembly’s 2010 Resolution on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation reflects international political recognition of the scope and content of this independent right. As international organizations, national governments and non-governmental advocates move to secure the implementation of this Resolution, this article explores opportunities to implement human rights as a means of realizing improved public health through rights-based water and sanitation policy. In examining the development of human rights to address the public health implications of water and sanitation, this article describes the role of human rights as a normative framework for public policy, assesses the evolution of a human right to water under international law and describes the 2010 UN Resolution that now shapes a distinct human right to water and sanitation. From the seminal role of the UN Resolution, the authors analyze the prospects for implementation of this Resolution through global water governance, national water policy, and water and sanitation outcomes. Recognizing that obstacles remain at each step of implementation, the authors outline research needed to examine the process by which human rights impact water and sanitation. With increased human rights specificity facilitating human rights accountability, this article concludes that there are now enhanced opportunities for rights-based water and sanitation policy, but that additional research will be necessary to overcome obstacles in translating human rights into improvements in the public’s health.

2. Development of human rights for water and sanitation

Given the pressing public health implications of water and sanitation – with 780 million people lacking access to improved drinking water and 2.5 billion people lacking access to improved sanitation services, underlying a wide array of communicable and non-communicable health threats – global governance has looked to human rights as a means of addressing these pervasive harms (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, 2012). Beyond viewing water and sanitation as a basic and pressing need, human rights implicate specific legal responsibilities to realize water and sanitation. Drawn normatively from human rights to health, development and an adequate standard of living, water and sanitation have come to be seen as an independent human right, transitioning from soft to hard law in the pursuit of international accountability for state obligations. Increasing in specificity through its normative development under international law, a distinct, composite human right to water and sanitation has found authoritative clarification through the political support of the UN General Assembly.

2.1. Human rights in public policy

Human rights offer universal frameworks to advance justice in global health. Addressing threats to public health as ‘rights violations’ offers international standards by which to frame government responsibilities and evaluate policies and outcomes under law, shifting the policy debate from political aspiration to legal accountability (Steiner et al., 2008). By empowering individuals to seek redress for rights violations rather than serving as passive recipients of government benevolence, international human rights law identifies individual rights-holders and their entitlements and corresponding duty-bearers and their obligations. With a state duty-bearer accepting resource-dependent obligations to realize rights ‘to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights’ (United Nations, 1966), states have been pressed to realize rights progressively through national and international policy (Felner, 2009). As a framework for global health governance, international organizations have increasingly invoked a ‘rights-based approach’ to health. Grounded in the right to health and rights to various underlying and interdependent determinants of health, this rights-based approach seeks to frame the policy environment, integrate core principles into programming and facilitate accountability under international law (Alston & Robinson, 2005).

The codification of human rights became a formal basis for global governance in the aftermath of World War II, with rights related to health serving to prevent deprivations like those that had taken place during the depression and the war that followed (Chapman & Russell, 2002). To provide a formal basis for assessing and adjudicating principles of justice (Donnelly, 2003), states worked under the auspices of the nascent UN General Assembly to enumerate and elaborate human rights under international law (Alston, 1984), proclaiming on December 10, 1948 a Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) to create ‘a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations’ (United Nations, 1948). Building from this non-binding Declaration, states continued to negotiate in the ensuing years to develop specific legal obligations under two separate human rights covenants, enacting in 1966 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). These three documents – the UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR, adopted separately by the UN General Assembly and referred to collectively as the ‘International Bill of Human Rights’ – form the normative basis of the human rights system from which rights to water and sanitation would evolve under international law.

2.2. Evolution of water as a human rights concern

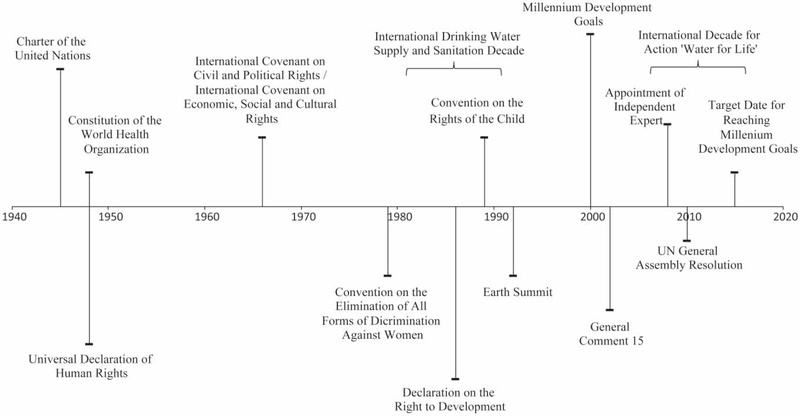

In the politically contentious evolution of human rights (United Nations, 2003), human rights to water and sanitation have developed dramatically, transitioning from implicit responsibility, through explicit obligation, to an independent right (Gupta et al., 2010) (Figure 1). Intertwined with concern for public health, the right to water has long been linked to the right to health, sharing a common history and interdependent evolution, with a distinct right to water and sanitation now finding independent international political consensus in the UN’s 2010 Resolution.

Fig. 1.

International evolution of human rights to water and sanitation.

The evolution of international legal norms in defining access to water as a human right begins in 1948 with the UDHR proclamation that ‘[e]veryone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family’ (United Nations, 1948). Operationalized by the 1948 Constitution of the World Health Organization, states declared that ‘the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being’, defining health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Organization, 1948). Developing through the rise of the UN’s human rights system, this right would be codified under international law in the 1966 ICESCR, elucidating a right to ‘the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ and developing state obligations for the ‘prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases’ (United Nations, 1966). Given rising public awareness of the role of environmental determinants of health (McNeill, 2010), leading to corresponding human rights claims in the late 1960s and early 1970s, international institutions moved to regulate impediments to water access as a means of ensuring public health (United Nations, 1972).

Flowing from national and international regulations to protect water resources, acknowledging the importance that water holds to nearly all aspects of life, a human right to water was recognized explicitly for the first time at the 1977 UN Water Conference in Mar del Plata. As delegates addressed issues of clean water supply and wastewater management, the Mar del Plata Action Plan proposed what would become the UN’s first International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (1981–90), concluding that ‘all peoples, whatever their stage of development and their social and economic conditions, have the right to have access to drinking water in quantities and of a quality equal to their basic needs’ (United Nations, 1977). While the proclamation of this collective right of ‘all peoples’ would not be binding on states (Shelton, 2001), this limited agreement on ‘basic needs’ began to build agreement around more expansive norms (for both access to and quality of water) that would come together in a human right under international law.

Over the next decade, the UN General Assembly adopted a series of international human rights treaties and declarations that extended this explicit recognition of a right to water, alternately derived from:

The Human Right to an Adequate Standard of Living, with the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women promulgating a state obligation to ‘ensure to [rural] women the right … to enjoy adequate living conditions, particularly in relation to housing, sanitation, electricity and water supply’ (United Nations, 1979);

The Human Right to Development, with the 1986 Declaration on the Right to Development finding a ‘mass violation of human rights’ where many in the developing world are prevented from accessing basic resources and prerequisites for development and ‘denied access to such essentials as food, water, clothing, housing and medicine in adequate measure’ (United Nations, 1986); and

The Human Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, with the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child linking health with water and sanitation to reinforce state obligations to ‘combat disease and malnutrition … through the provision of adequate nutritious food and clean drinking-water’ and to ensure that individuals are ‘informed, have access to education and are supported in the basic knowledge of … hygiene and environmental sanitation’ (United Nations, 1989).

Although non-governmental advocates continued to proclaim water as a human right into the 1990s (ICWE, 1992), states moved away from this rights-based approach to water and sanitation policy (Gleick, 1998), with governments agreeing at the 1992 Earth Summit that ‘in developing and using water resources, priority has to be given to the satisfaction of basic needs and the safeguarding of ecosystems. Beyond these requirements, however, water users should be charged appropriately’ (United Nationss, 1992). With progress on access to water intersecting with debates on private sector provision of drinking water, issues of affordable access to water were revisited anew by the 2000 Millennium Declaration, which resolved ‘to halve the proportion of people who are unable to reach or to afford safe drinking water’ (United Nations, 2000). Based upon 1990 baseline levels, the accompanying Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) joined water and sanitation, setting a target to ‘halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation’. Given continuing increases in water scarcity and inequity, limitations on national water policies and conflicts surrounding privatization of water systems, advocates at national, regional and international levels turned to the human right to water as a means of reframing water as a public good and a government responsibility (Bluemel, 2004).

Returning these commitments to the international legal obligations of human rights institutions, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) – authorized by the ICESCR to interpret state obligations and review state reports – sought to codify an independent human right to water. Through its fifteenth General Comment, the CESCR defined the scope and content of a human right to water, holding that ‘the human right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity. It is a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights’ (CESCR, 2002, para 1).

Building upon the water and sanitation targets in the MDGs, commitments criticized for neglecting rights-based approaches to equity in development (Alston, 2005), General Comment 15 delineates the core obligations of a right to water, proscribes violations of those obligations and outlines a policy roadmap for states to progressively realize access to water. Where water is not mentioned in the original text of the ICESCR, the CESCR interpreted it into the ICESCR based upon existing provisions, finding in General Comment 15 that a right to water is normatively situated under the umbrella of the human right to a standard of living (ICESCR, art. 11) and the human right to health (ICESCR, art. 12). Reasoning that ‘…an adequate amount of safe water is necessary to prevent death from dehydration, to reduce the risk of water-related disease and to provide for consumption, cooking, personal and domestic hygienic requirements’, the CESCR (2002) concluded that ‘the human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses’ (para 2).

Framed by overarching obligations to respect (not interfere), protect (from third party interference) and fulfill (take positive steps to facilitate, promote and provide for) the right to water, General Comment 15 articulates discrete state obligations to ‘ensure access to the minimum essential amount of water that is sufficient and safe for personal and domestic uses to prevent diseases’ and ‘to take measures to prevent, treat and control diseases linked to water, in particular ensuring access to adequate sanitation’ (CESCR, 2002, para 37). By invoking this right as a means of realizing public health, thereby including obligations for sanitation under a right to water, General Comment 15 outlines a series of government responsibilities for national water strategies and plans of action, structuring state accountability for water policy.

Following from the adoption of General Comment 15, the UN Human Rights Council directed the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to report on the scope and content of human rights obligations related to equitable access to safe drinking water and sanitation, drawing from the MDGs in joining water and sanitation as separate but interconnected rights-based responsibilities (Weiss, 2007). Further expanding the normative content of the human right, the Office of the High Commissioner surveyed the legal framework of the right; clarified the meaning, scope and content of ‘safe drinking water’, ‘sanitation’ and ‘access’; analyzed states’ obligations to respect, protect and fulfill a right to water and sanitation; and outlined relevant monitoring mechanisms at the international and national levels to ensure state compliance with human rights obligations to realize water and sanitation. From the recommendations of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2007), which concluded that the time had come to define access to safe drinking water and sanitation as a distinct human right, the Human Rights Council (2008) created the position of an independent expert on human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation. Appointing Catarina de Albuquerque as the first Independent Expert to the Human Rights Council, her first report in July 2009 recommended that the UN declare water and sanitation to be interconnected but distinct human rights (de Albuquerque, 2009).

2.3. UN Resolution on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation

One year later, the UN General Assembly departed from this recommendation, declaring safe and clean drinking water and sanitation to be a single human right under international law. Under its July 2010 Resolution – ‘The Human Right to Water and Sanitation’, adopted by a vote of 122 to 0, with 41 abstentions – the General Assembly explicitly joined water and sanitation as a singular, composite human right, an independent right that would necessitate obligations to provide water and sanitation for the most vulnerable. Introduced by the Bolivian representative, Pablo Solón – whose prefatory remarks catalogued the dynamic nature of human rights, the evolution of rights-based norms and the health harms stemming from a lack of water and sanitation (Solón, 2010) – the approved resolution:

Recognizes the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights;

Calls upon states and international organizations to provide financial resources, capacity-building and technology transfer, through international assistance and cooperation, in particular to developing countries, in order to scale up efforts to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all (United Nations, 2010).

As this Resolution was developed and sponsored by a small group of developing states, it quickly raised the objections of excluded state representatives from developed countries, who found that the push for a General Assembly resolution took ‘a short-cut around the serious work of formulating, articulating and upholding universal rights’ in the UN’s Human Rights Council prior to advancing the Resolution to the entire UN General Assembly (Sammis, 2010). Despite these procedural objections – compounded by substantive concerns that the Resolution did not fully reflect the current state of international legal negotiations (leading sponsoring states to replace the word ‘declares’ with ‘recognizes’ in an effort to achieve consensus for paragraph 1) – states opted to abstain from this vote rather than vote in opposition to a politically popular consensus (Crook, 2010). Although commentators have discussed a wide range of substantive concerns underlying state abstentions, from issues of water commodification to international obligation (Pardy, 2011), abstaining states raised only procedural concerns in their public objections (General Assembly Official Records, 2010), reflecting the political resonance of rights-based discourses and raising the political costs of denying the existence of a human right to water and sanitation (de Albuquerque, 2011a). Extending the substance of this General Assembly Resolution, the UN’s Human Rights Council resolved in September 2010 that the human right to water and sanitation was legally binding on state governments under established human rights, avoiding the expansive international obligations declared by the General Assembly while reiterating the ‘primary responsibility’ of national governments for safe drinking water and sanitation (UN Human Rights Council, 2010a).

In building from the evolving formal and informal standards that preceded it and encouraging the work of the UN Independent Expert to substantiate this right in the years to come, the UN Resolution is the culmination of advocates’ past efforts and a fountainhead for future efforts. This Resolution has given political recognition to the establishment of an independent right to water and sanitation, supporting the reasoning of General Comment 15 and declaring a state obligation that many now consider to bind all nations under customary international law (Bates, 2010). Despite arguments that the use of more established human rights (e.g. the right to health) would be more effective in realizing the provision of water and sanitation (Gavouneli, 2011), a complementary approach endorsed by the Human Rights Council (2010b), few continue to doubt the legitimacy of this new right, with the UN Resolution creating a normative framework to implement the right to water and sanitation through water policy.

Transitioning from human rights development to rights-based policy implementation, Independent Expert de Albuquerque – warning that the MDGs are insufficient to create accountability for efforts to make water available, acceptable, accessible (reliable, affordable and sustainable) and of safe quality – has argued that ‘we have an even greater responsibility to concentrate all our efforts in the implementation and full realization of this essential right’ (2010). With the UN appointing de Albuquerque as the first Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, giving her a mandate to engage directly with governments and other stakeholders, she has taken up issues of accountability for implementing the UN Resolution (UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2011).

3. Implementation of the human right to water and sanitation

The political recognition of the right to water and sanitation by the UN represents a milestone in the development of international law, memorializing international consensus on the substantive content of an independent human right to water and sanitation and the corresponding obligations of governments to respect, protect and fulfill the right. Where the right to water and sanitation was thought to be divisive in global governance, unenforceable under national policy and unaccountable for health outcomes, the UN Resolution has provided an international legal framework for what had previously been only the recommendation of scholars and advocates. Examining the prospective impact of the UN Resolution on the implementation of the human right to water and sanitation, this analysis looks to the cascading influence of the UN Resolution on global water governance, national water policy and water and sanitation outcomes.

3.1. Global water governance

In adopting a human right to water and sanitation in global governance, international organizations now have an expanded normative framework by which to structure rights-based water and sanitation policy. Coordinating policies to structure the availability, accessibility and sustainability of high-quality sources of water, institutions of global water governance can provide a basis by which global norms are set and consensus is built, thereby guiding national water policies. Yet as global governance has become increasingly fragmented, with international organizations in the UN system forced to compete for scarce resources and attention in a crowded global health policy landscape (leading at times to redundancy and ineffectiveness (Szlezák et al., 2010)), the human right to water and sanitation can become a basis for building more effective partnerships and establishing shared global goals across existing actors and organizations.

Founded upon a rich history of inter-organizational water governance efforts – from the 1977 action plan of Mar del Plata, through the 1992 sustainable development agenda of the Dublin Statement, to the 2000 global consensus of the MDGs – cooperation across institutions can provide a structural basis for implementing the human right to water and sanitation. Such longstanding partnerships have created an extant structure for coordination to address water and sanitation, providing a basis in global governance to incorporate the human right to water and sanitation in framing a post-2015 agenda in global water policy (de Albuquerque, 2011b). Similar to global conferences like the World Water Forums and regional sanitation conferences, which seek to translate scientific knowledge into programmatic recommendations (Pahl-Wost & Gupta, 2008), the human rights approach can build upon the MDG for water and sanitation in identifying rights-based concerns (e.g. non-discrimination and equality) in global water policy (de Albuquerque, 2010). As such, the right to water and sanitation offers a normative basis for global coordination and cooperation under a set of shared goals, with General Comment 15 giving credence to the responsibilities of these multisectoral actors:

United Nations agencies and other international organizations concerned with water, such as WHO, FAO, UNICEF, UNEP, UN-Habitat, ILO, UNDP, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), as well as international organizations concerned with trade such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), should cooperate effectively with state parties, building on their respective expertise, in relation to the implementation of the right to water at the national level. The international financial institutions, notably the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, should take into account the right to water in their lending policies, credit agreements, structural adjustment programmes and other development projects … so that the enjoyment of the right to water is promoted (CESCR, 2002).

Despite these calls for a rights-based approach to water governance, many organizations have not often sought to implement human rights in their water and sanitation programming and partnerships (Russell, 2010). Where such avoidance of human rights stems from a reluctance of international organizations to engage ‘political’ discourses without a mandate from their governing bodies (Huang, 2008), the UN Resolution has provided political direction to engage human rights debates and cooperate across organizations to realize water and sanitation. In providing shared norms to structure global partnerships, the Resolution calls specifically on ‘international organizations to provide financial resources, capacity-building and technology transfer, through international assistance and cooperation, in particular to developing countries, in order to scale up efforts to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all’ (United Nations, 2010).

Among UN agencies, WHO has the institutional authority and public health legitimacy to take a leadership role in such partnerships across international organizations, drawing on its constitutional mandate to implement a rights-based approach to health (World Health Organization, 1948). With WHO viewing water and sanitation through the lens of human rights, it has long explored multisectoral partnerships for water and sanitation systems through, among other things:

World Health Assembly support for an integrated WHO strategy for water, sanitation and health, with states requesting that WHO strengthen collaborations with all relevant UN Water members and partners to promote access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene services (World Health Assembly, 2011);

Advocacy to support the inclusion of water and sanitation under WHO frameworks for primary health care (World Health Organization, 1978) and UN frameworks for human rights (Hunt & Backman, 2008);

Hosting the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council following the end of the International Drinking-water Supply and Sanitation Decade (United Nations, 1990);

The promulgation of international guidelines as a basis for national standard setting on drinking water quantity and quality (World Health Organization, 2011);

The establishment of a Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Health Unit, which elaborated water and sanitation guidelines, provided technical support to low- and middle-income countries and supported international water and sanitation conferences (Bartram & Gordon, 2008); and

Collaboration with UNICEF’s Water, Environment and Sanitation Program in developing the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program, reporting state progress on water and sanitation measures, assessing progress toward MDG targets and providing data for UN policymaking (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, 2011).

Through these efforts, WHO became an early proponent of interagency partnerships to operationalize human rights for water and sanitation (World Health Organization, 2003), in accordance with the UN’s cross-cutting commitment to ‘mainstream’ human rights in all programs, policies and activities (Annan, 1997), recognizing ‘the utility of key human rights principles as guides for development programming’ (World Health Organization, 2005). As the UN Resolution has provided an enhanced political basis for this cooperation, WHO has an opportunity to structure global health partnerships to implement the international legal standards of the right to water and sanitation.

Under the WHO’s coordinating authority for global health, such global governance necessitates multisectoral partnerships that are reflective of the influence of water and sanitation as underlying determinants of health, with international political recognition for the right to water and sanitation framing shared goals for interagency cooperation, throughout the UN and among global institutions. Through such collaborative rights-based efforts, these partnerships can enhance information sharing between stakeholders, reduce redundancies in programs, establish best practices and facilitate negotiation processes (Moon et al., 2010). Efforts are already underway by various institutions – whether public, private, or civil society – to legitimize and motivate their activities in accordance with the human right to water and sanitation (Russell, 2010). In partnership with established human rights institutions and individuals (such as the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation), these global water and sanitation actors can collaborate with states to mainstream human rights in global water governance and implement global efforts through national water policy.

3.2. National water policy

As global governance is translated into national policy, this new rights-based agenda has laid the groundwork over which an expanding implementation movement can be established at the intersection of human rights and water and sanitation policy. National water policy serves as the principal means of realizing the human right to water and sanitation (Staddon et al., 2012), implementing human rights through national practice. With the UN Resolution providing states with international political recognition of definitions, standards and obligations – rights-based norms developed over the preceding decades – the normative frameworks of this evolving human right can structure national law, facilitate judicial enforcement and advance political advocacy to ensure human rights implementation through national water policy.

Given that many national regulatory frameworks for water and sanitation are dissociated from international human rights frameworks (Cullen, 2011), implementation of the right to water and sanitation is supported most directly through incorporation into national law, whether enshrined in a national constitution, drafted into implementing legislation, or extrapolated from other rights (Smets, 2006). In accordance with such rights-based implementation, the right to water and sanitation has been proclaimed under an array of modern constitutions – including those of South Africa, Kenya and Ecuador – and such constitutional amendments are expanding in the wake of the UN Resolution (Jeffords, forthcoming). Beyond constitutional law, states have sought to realize the right to water and sanitation through codification of its obligations in national legislation (Bourquain, 2008), evidenced by the extensive development of rights-based laws since the adoption of the UN Resolution (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization, 2012). Finally, among states that have long upheld water rights in national law, these states have sought to interpret water and sanitation obligations from other rights already protected by the nation’s law, as seen where Indian jurists have derived a right to water from the constitutional right to life (Chowdhury et al., 2011). With the UN Resolution now providing international recognition of a universal framework for national policy, states can now meet their obligations through more explicit rights-based legal reforms, tied to the specific norms of the human right to water and sanitation.

In interpreting the human right to water and sanitation through judicial enforcement, litigation has the potential to play a crucial role in advancing human rights in national policy, continuously pressing governments to re-examine efforts to realize water and sanitation (Harvard Law Review, 2007). As each state is obligated under international law to ‘progressively realize’ this right ‘to the maximum of its available resources’, such a resource-dependent obligation leaves room for interpretation in implementing the right to water and sanitation through limited national resources (UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2011). Driving national policy forward in the state’s progressive realization of rights, litigation can empower individuals to raise human rights claims, seek impartial adjudication and demand rights-based remedies, with courts often standing as a last resort in advancing the health interests of vulnerable populations (Meier et al., 2012). Through national courts or before supra-national tribunals, legal claims allow individuals to contest government policy for the progressive realization of water and sanitation and thereby clarify national implementation, enforce government obligations and provide restitution for violations (Yamin & Gloppen, 2011). For example, based upon South Africa’s constitutional codification of a right of access to sufficient water, the South African Constitutional Court has found a state obligation to provide water systems through healthy conditions for housing (South African Constitutional Court, 2000), while striking down individual claims to a minimum level of free water for basic hygiene and consumption needs (South African Constitutional Court, 2009) – structuring the progressive realization of water through ‘reasonable’ limitations in national budgeting and planning (Danchin, 2010). As many water-based claims are currently advanced indirectly – under the human rights implicated by water and sanitation policy (exemplified by obligations interpreted from rights to life and health in India, rights to the environment in Argentina and rights to an adequate standard of living in the European human rights system) – direct action under an independent right to water and sanitation has the potential to confront the harm and provide the remedy more precisely (Bluemel, 2004). Supported by international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) has led the way in public interest litigation supporting individuals and communities whose water and sanitation rights have been violated (Roaf et al., 2005). As these claims continue to resonate in transnational social movements, buttressed by the political authority of the UN Resolution, it is likely that legal precedents under the right to water and sanitation will diffuse across a wide range of water advocates and judicial forums, translated into government reforms in water policy.

Complementing these formal means of realizing water and sanitation through national policy, the human rights norms endorsed by the UN Resolution can be employed informally to advance national discourses through political advocacy, wherein ‘naming and shaming’ are employed as a means of advancing human rights progress (Roth, 2004). In this advocacy, the human right to water and sanitation addresses the affordability of water use and infrastructures for water treatment (Moss et al., 2003). With water widely accepted as both an economic good and a social good, national policy becomes necessary for sufficient investment in sustainable water infrastructures (Winpenny, 2003). Given expanding private sector involvement in the water sector, policy efforts are underway to assure mechanisms for the affordable supply of water to all individuals, especially the most vulnerable (Prasad, 2007). Moving away from discussions on what kind of ownership and management is most appropriate, debates on the relative merits of public or private involvement in the water sector have given way to discourses on the conditions under which water services can be provided safely, sufficiently, affordably and sustainably in accordance with human rights standards (Bakker, 2007). By providing a normative framework for infrastructure sustainability, investor confidence and affordable access, human rights can provide principles for political advocacy in the water sector (Rouse, 2007). NGOs, employing rights-based standards in their advocacy, have begun to combine their advocacy efforts under the UN Resolution as a means of holding states responsible for human rights (de Albuquerque & Roaf, 2012). As seen in the work of WaterAid and the Freshwater Action Network, NGOs are now working closely with the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation to pursue the implementation of the human right to water and sanitation in national policies and programming, developing advocacy guides to advance future rights-based policy reforms.

3.3. Water and sanitation outcomes

These global and national efforts have created a policy basis by which implementation of the right to water and sanitation can structure water and sanitation systems to promote the public’s health, but for this right to be established, there must be mechanisms in place to ensure state accountability for water and sanitation outcomes. While there are currently mechanisms for international monitoring of the right to water and sanitation, as seen most prominently in state periodic reporting to the CESCR, states have not routinely reported water and sanitation data to international human rights treaty bodies (Roaf et al., 2005). Analogously, while there are currently public health benchmarks for reporting water and sanitation data (Bartram et al., 2001), these have not been linked to human rights norms, limiting state accountability for their realization (Salman & McInerney-Lankford, 2004). As the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation seeks to achieve accountability for rights-based policy implementation, indicators are increasingly seen to be critical to operationalizing the human right to water and sanitation, providing precision in state reporting and structuring state reports around comparable data (de Albuquerque, 2011b). With a specific mandate to address the MDGs, the Special Rapporteur has argued that these goals are insufficient to realize equity, seeking to reform the water and sanitation targets of the post-2015 (post-MDG) framework to be more responsive to rights-based concerns (de Albuquerque, 2010). The creation of rights-based targets, benchmarks and timelines can facilitate the translation of the human right to water and sanitation into measurable indicators (Fukuda-Parr et al., 2009). As indicators are able to structure rights-based accountability, guide policy formulation, frame international monitoring and catalyze civil society (Conca, 2005), the UN Resolution supports efforts to develop indicators for the human right to water and sanitation and employ those indicators in state human rights reports.

In focusing national resources in accordance with the human right to water and sanitation, these indicators can be employed to create accountability for state obligations to engage water and sanitation to the maximum of their available resources and gradually improve results and increase equity in water and sanitation outcomes (de Albuquerque, 2011b). To assure monitoring of the progressive realization of rights, gauging incremental assessments of state compliance, the CESCR first advocated the development of indicators in national water strategies or plans of action, finding that:

… right to water indicators should be identified in the national water strategies or plans of action. The indicators should be designed to monitor, at the national and international levels, the State party’s obligations … [and] should address the different components of adequate water (such as sufficiency, safety and acceptability, affordability and physical accessibility), be disaggregated by the prohibited grounds of discrimination and cover all persons residing in the State party’s territorial jurisdiction or under their control (CESCR, 2002, para 53).

Framing policy measurements through a normative lens, the human rights practice community has embraced indicators as part of a larger drive for assessment and monitoring of state obligations for the realization of human rights, especially economic, social and cultural rights (Rosga & Satterthwaite, 2009). With indicators long seen as integral to the success of global environmental and global health frameworks (Chasek et al., 2006), the water and sanitation community has begun to look to the development of rights-based indicators as a means of holding governments accountable for realizing the right to water and sanitation (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, 2011).

The Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation has begun a process to identify specific indicators reflective of the realization of the human right (de Albuquerque, 2010), laying the groundwork for global water governance through international rights-based monitoring. To rectify weaknesses in accountability for state obligations to realize the right to water and sanitation, the Special Rapporteur has sought to justify a rights-based approach to indicators, stating that such indicators would more accurately illustrate progress based on the availability, safety, acceptability, accessibility (reliability, affordability and sustainability) and quality of water and sanitation. Engaging interdisciplinary collaborations on human rights accountability, scholars, practitioners and advocates have sought to identify indicators that are relevant at global and national levels, adapting global measures to national contexts and disaggregating national data to reflect sub-national inequities (de Albuquerque, 2011b).

Such an indicator development process, developed under the mantle of the UN Resolution, seeks to create universally applicable rights-based indicators for the use of the CESCR (and other treaty monitoring bodies) in evaluating state compliance with the right to water and sanitation. Where detailed cross-national data sets already exist, water professionals and policymakers have sought to utilize existing public health and development data, but to examine these data through the state obligations of the right to water and sanitation and to assess them through the UN’s human rights institutions (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, 2011). In this indicator development process, the Special Rapporteur stresses that the UN Resolution has given political legitimacy to efforts to incorporate human rights indicators into the global development agenda, with the Resolution endowing these efforts with legal obligations, moral character, clear roles in international relations and powerful legal frameworks for practitioners working in water and sanitation policy (de Albuquerque, 2011b). Creating a post-2015 framework for global water justice (with indicators for water and sanitation scheduled to be addressed at the September 2013 meeting of the UN General Assembly), such rights-based indicators would take measure of government efforts to implement the human right to water and sanitation.

4. Obstacles to implementation of human rights

While the UN’s 2010 Resolution has provided opportunities to realize equitable access to safe water and sanitation, policymakers will face a series of obstacles in implementing the human right to water and sanitation through global water governance, national water policy and water and sanitation outcomes. Despite avenues for implementation, realization of the right to water and sanitation may be hampered by diverse factors, including (i) lack of political will, (ii) financial constraints, (iii) limited access to infrastructure, (iv) lessened administrative capacity for implementation, coordination and monitoring of rights based policies, (v) insufficient technical capacity to ensure water and sanitation polices are followed, (vi) incomplete information on populations without access and (vii) challenges of water scarcity compounded by climate change. With these obstacles potentially impacting water and sanitation – as global, national and local actors seek to implement the rights-based consensus of the UN Resolution – it is vital that scholars conceptualize and examine the causal process by which human rights have an impact on water policy for the public’s health.

As global institutions seek to advance the right to water and sanitation, global water governance may face resistance from developed nations’ foreign assistance programs for water and sanitation, leading to a weakening of international institutions (Weiss, 2005). Despite the tempering of international human rights obligations since the UN Resolution, developed nations have expressed concerns that developing nations may employ the human right to water and sanitation to compel other countries to supply needed water funding under the auspices of rights-based international assistance and cooperation (Khalfan, 2012). With the risk of international claims and without sanctions for non-compliance, there is a fear that such international obligations may lead developed states to entrench themselves further in policy efforts to achieve national self-interest, subverting the promise of cooperative partnerships under the UN Resolution (Pardy, 2011).

At the level of national policy, it is unclear to what degree changes in global health governance will result in beneficial changes in national water and sanitation policy. With many nations facing intense capital constraints, analysts have questioned whether states will continue to support the sustainable financial resources (costs associated with operation and maintenance) and administrative resources (capacity to ensure adherence to water safety and sanitation policies) necessary for the construction of infrastructure to guarantee access to adequate water and sanitation (Briscoe, 2011). Given these resource constraints, there is a risk that efforts to implement the human right to water and sanitation could re-ignite debates on private sector roles (Asthana, 2011). As national policy seeks to assure responsibility for water and sanitation, pricing decisions may cause budgetary tensions and where there are few legal avenues by which to interpret human rights and enforce state obligations (or where such tribunals are not suited to the litigation of water and sanitation issues of a technical nature), disagreements over water and sanitation may not prove amenable to resolution through policy reform (Dennis & Steward, 2004).

Finally, in leading to water and sanitation outcomes, given the myriad threats to water and sanitation, it is unclear whether the implementation of the right to water and sanitation through policy reform will lead to the water and sanitation outcomes sought by proponents. Where the human right is premised on state obligations (Bluemel, 2004), national accountability for safe water and sanitation may be confounded by global threats, among them the environmental constraints brought on by global climate change (Kundzewicz et al., 2007). Further, in establishing state accountability through rights-based indicators, the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation has noted methodological obstacles in identifying data reflective of the realization of the human right, arguing that:

Our challenge is to identify indicators that can be used at the global level. We need to find a way to measure water quality that works in different contexts … to measure affordability of water and sanitation services – understanding the very complex considerations of what gets included in household income, how to calculate unpaid work, etc … How can we measure reliability and sustainability … and adapt them to local and national circumstances? (de Albuquerque, 2011a).

As states enact policies and programming to improve water and sanitation outcomes and indicators are developed to assess those outcomes, it will be necessary to identify measures that are reflective of rights-based obligations, assessable through existing data and conducive to human rights monitoring.

5. Conclusion

The 2010 UN General Assembly Resolution on a Human Right to Water and Sanitation presents a seminal international political consensus for implementing rights-based water and sanitation policy, addressing the most prevalent harms to health among the world’s most vulnerable populations. While there remain obstacles to the implementation of this rights-based agenda, the UN Resolution has created new opportunities to enhance global efforts to realize water and sanitation through water policy. In translating human rights law into public policy, research is needed to explore the causal links between human rights implementation and water and sanitation realization at each level in the policy processes, clarifying the mechanisms by which the human right to water and sanitation is implemented through global water governance, national water policy and water and sanitation outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Global Research Institute, the Fogarty Foundation’s Water Wisdom Program and the Water Institute at UNC. The authors are grateful to Glenn McLaurin, Rachel Baum and Allison Norman for their research assistance and to Eibe Riedel, Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum and Malcolm Langford for their thoughtful comments on previous drafts of this article.

References

- Alston P (1984). Conjuring up new human rights: a proposal for quality control. American Journal of International Law 78(3), 607–621. [Google Scholar]

- Alston P (2005). Ships passing in the night: the current state of the human rights and development debate seen through the lens of the Millennium Development Goals. Human Rights Quarterly 27(3), 755–829. [Google Scholar]

- Alston P & Robinson M (eds) (2005). Human Rights and Development: Towards Mutual Reinforcement. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Annan K (1997). Renewing the United Nations: A Programme for Reform, delivered to the General Assembly, UN Doc. A/51/950. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Asthana AN (2011). The business of water: fresh perspectives and future challenges. African Journal of Business Management 5(35), 13398–13403. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker K (2007). The ‘commons’ versus the ‘commodity’: alter-globalization, anti-privatization and the human right to water in the global south. Antipode 39(3), 430–455. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram J & Gordon B (2008). The global challenge of water quality and health. Water Practice & Technology 3(4), 957–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram J, Fewtrell L & Stenström T-A (2001). Harmonised assessment of risk and risk management for water-related infectious disease: an overview In Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards and Health. Bartram J & Fewtrell L (eds). World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Bates R (2010). The road to the well: an evaluation of the customary right to water. Review of European Community & International Environmental Law 19(3), 282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bluemel EB (2004). The implications of formulation a human right to water. Ecology Law Quarterly 31(4), 957–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Bourquain K (2008). Freshwater Access from a Human Rights Perspective: A Challenge to International Water and Human Rights Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J (2011). Invited opinion interview: two decades at the center of world water policy. Water Policy 13, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AR & Russell S (2002). Core Obligations: Building a Framework for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Intersentia, Antwerp, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Chasek P, Downie D & Brown J (2006). Global Environmental Politics. Westview Press, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury N, Mustu B, St. Dennis H & Yap M (2011). The Human Right to Water and the Responsibilities of Businesses: An Analysis of Legal Issues. School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS) International Human Rights Clinic for the Institute for Human Rights and Business, London. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) (2002). General Comment 15. United Nations, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Conca K (2005). Governing Water: Contentious Transnational Politics and Global Institution Building. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Crook JR (2010). United States abstains on General Assembly resolution proclaiming human right to water and sanitation. American Journal of International Law 104, 672–673. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P (2011). Water law in a globalised world: the need for a new conceptual framework. Journal of Environmental Law 23, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Danchin P (2010). A human right to water? The South African Constitutional Court’s decision in the Mazibuko case. EJIL, Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law. Available at: http://www.ejiltalk.org/a-human-right-to-water-the-south-african-constitutional-court%E2%80%99s-decision-in-the-mazibuko-case/.

- de Albuquerque C (2009). Report of the Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation. A/HRC/12/2. United Nations, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque C (2010). Statement by Catarina de Albuquerque, Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, 65th session of the General Assembly, Third Committee, Item 69(b), 6 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque C (2011a). Keynote Address: Towards the post 2015 development agenda: The importance of fully integrating human rights. International Conference on Water and Health: Where Science Meets Policy Water Institute and the Environment Institute University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, October 3–7, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque C (2011b). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, 66th session of the General Assembly, Third Committee, Item 69(b), 3 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque C & Roaf V (2012). On the Right Track: Good Practices in Realising the Rights to Water and Sanitation. OHCHR, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MJ & Steward DP (2004). Justiciability of economic, social and cultural rights: should there be an international complaints mechanism to adjudicate the rights to food, water, housing and health? American Journal of International Law 98, 462–515. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly J (2003). Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice. Cornell University Press, Ithaca. [Google Scholar]

- Felner E (2009). Closing the ‘escape hatch’: a toolkit to monitor the progressive realization of economic, social and cultural rights. Journal of Human Rights Practice I(3), 402–435. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda-Parr S, Lawson-Remer T & Randolph S (2009). An index of economic and social rights fulfillment: concept and methodology. Journal of Human Rights 8, 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gavouneli M (2011). A human right to groundwater? International Community Law Review 13(3), 305–319. [Google Scholar]

- General Assembly Official Records (2010), 28 July 2010 108th Plenary Meeting: Agenda Item 48.A/64/PV.108 United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick PH (1998). The human right to water. Water Policy 1(5), 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Ahlers R & Ahmed L (2010). The human right to water: moving towards consensus in a fragmented world. Review of European Community & International Environmental Law 19(3), 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard L Rev. (2007). What price for the priceless? Implementing the justiciability of the right to water. Harvard Law Review 120, 1067–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L (2008). Not just another drop in the human rights bucket: the legal significance. Florida Journal of International Law 20, 353–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P & Backman G (2008). Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Health and Human Rights 10(1), 81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICWE (1992). Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development. International Conference on Water and the Environment Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffords C (forthcoming). Constitutional environmental human rights: a descriptive analysis of 142 national constitutions In The State of Economic and Social Human Rights: A Global Overview. Minkler L (ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Khalfan A (2012). Development cooperation and extraterritorial obligations In The Right to Water: Theory, Practice and Prospects. Langford M & Russell A (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kundzewicz Z, Mata L, Arnell N, Döll P, Kabat P, Jiménez B, Miller K, Oki T, Sen Z, Shlklomanov I, Asanuma J, Betts R, Cohen S, Milly C, Nearing M, Prudhomme C, Pulwarty R, Schulze R, Thayyen R, van de Giesen N, van Schaik H, Wilbanks T & Wilby R (2007). Freshwater resources and their management In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry M, Canziani O, Palutikof J, van der Linden P & Hanson C (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill JR (2010). The environment, environmentalism and international society in the long 1970s In The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective. Ferguson N (ed.). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Meier BM, Cabrera OA, Ayala A & Gostin LO (2012). Bridging international law and rights-based litigation: mapping health-related rights through the development of the global health and human rights database. Health and Human Rights: An International Journal 14, 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S, Szlezák NA, Michaud CM, Jamison DT, Keusch GT, Clark WC & Bloom BR (2010). The Global Health System: Lessons for a Stronger Institutional Framework. PLoS Medicine, 26 January. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Wolff G, Gladden G & Guttieriez E (2003). Valuing Water for Better Governance. How to Promote Dialogue to Balance Social, Environmental and Economic Values? World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl C & Gupta JD (2008). Governance and the global water system: a theoretical exploration. Global Governance 14, 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Pardy B (2011). The dark irony of international water rights. Pace Environmental Law Review 28, 907–920. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad N (2007). Social Policies and Water Sector Reform UN Research Institute for Social Development. Markets, Business and Regulation Programme Paper, Number 3. UNRISD, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Roaf V, Khalfan A & Langford M (2005). Monitoring Implementation of the Right to Water: A Framework for Developing Indicators Global Issues Papers, No. 14, 64 Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Rosga A & Satterthwaite M (2009). The trust in indicators: measuring human rights. Berkeley Journal of International Law 27, 253–310. [Google Scholar]

- Roth K (2004). Defending economic, social and cultural rights: practical issues faced by an international human rights organization. Human Rights Quarterly 26(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse M (2007). Institutional Governance and Regulation of Water Services: The Essential Elements. International Water Association, London. [Google Scholar]

- Russell AFS (2010). International organizations and human rights: realizing, resisting or repackaging the right to water. Journal of Human Rights 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Salman SMA & McInerney-Lankford S (2004). The Human Right to Water: Legal and Policy Dimensions. World Bank, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Sammis JF (2010). US Mission to the United Nations, Press Release, Explanation of Vote by John F Sammis, U.S. Deputy Representative to the Economic and Social Council, on Resolution A/64/L.63/Rev. 1, The Human Right to Water. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton D (2001). Environmental rights In People’s Rights. Phillip A (ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Smets H (2006). The Right to Water in National Legislations. Agence Française de Développement, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Solón P (2010). General Assembly Official Records, 108th Plenary Meeting: Agenda Item 48 A/64/PV.108. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- South African Constitutional Court (2000). Government of the Republic of South Africa and Others v. Grootboom and Others, 2000 (11) BCLR 1169 (CC). [Google Scholar]

- South African Constitutional Court (2009). Mazibuko and Others v. City of Johannesburg and Others. (CCT 39/09), ZACC 28. [Google Scholar]

- Staddon C, Appleby T & Grant E (2012). A right to water? Geographico-legal perspectives In Right to Water: Politics, Governance and Social Struggles. Sultana F & Loftus A (eds). Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner HJ, Alston P & Goodman R (2008). International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Szlezák NA, Bloom BR, Jamison DT, Keusch GT, Michaud CM, Moon S & Clark WC (2010). The Global Health System: Actors, Norms and Expectations in Transition. PLoS Medicine, 5 January. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Rights to Water and Sanitation (2011). Available at: http://www.righttowater.info/.

- UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2007). Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Scope and Content of the Relevant Human Rights Obligations related to Equitable Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation under International Human Rights Instruments. A/HRC/6/3. [Google Scholar]

- UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2011). Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation. UN Doc. A/66/255. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council (2008). Resolution 7/22: Human Rights and Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation. United Nations, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council (2010a). Resolution on Human Rights and Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation (A/HRC/15/L.14, 24 September 2010), United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council (2010b). Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health (A/HRC/RES/15/22, 6 October 2010). United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. G.A. Res. 217A (III), at 71, U.N. GAOR, 3d Session, 1st plenary meeting, UN Doc. A/810. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

- United Nations (1972). Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment Stockholm. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1977). Report of the United Nations Water Conference, Mar del Plata 14–25 March 1977, UN Pub. EE77 II A 12, available at: http://www.ielrc.org/content/e7701.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1249 U.N.T.S. 13. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1986). Declaration on the Right to Development GA Res. 41/128. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child 1577 U.N.T.S. 3. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1992). Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 14 June 1992 Report of the UN Conference on Environment and Development UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26/Rev.1, vol. 1, annex I. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2000). Millennium Development Goals. G.A. Res. 55/2, U.N. GAOR, 55th Session, 8th plenary meeting, UN Doc. A/RES/55/2 United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2003). The Right to Water International Year of Freshwater 2003. United Nations Department of Public Information, http://www.un.org/events/water/TheRighttoWater.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2010). Resolution on Human Right to Water and Sanitation. UN General Assembly Resolution; A/64/292. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization (2012). Water Law and Standards, http://www.waterlawandstandards.org/.

- United Nations General Assembly (1990). International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade Resolution A/RES/45/181. United Nations, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EB (2005). Water transfers and international trade law In Fresh Water and International Economic Law. Weiss EB, de Chazournes LB & Bernasconi-Osterwalder N (eds). Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EB (2007). The evolution of international water law In Recueil Des Cours: Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law 2007. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden, The Netherlands, pp. 167–404. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (2012). Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation, 2012 Update. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (2011). Report of the First Consultation on Post-2015 Monitoring of Drinking-Water and Sanitation. Berlin 3–5 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Winpenny J (2003). OECD Global Forum on Sustainable Development: Financing Water and Environmental Infrastructure for All. Michel Camdessus Panel, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Assembly (2011). Drinking Water, Sanitation and Health. Resolution 64/24. 24 May. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1948). Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization ( 2003). The Right to Water. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2005). Health and Human Rights Activities within WHO, http://www.who.int/hhr/en/index.html.

- World Health Organization (2011). Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality. 4th edition. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin AE & Gloppen S (2011). Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health? Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]