Abstract

Recently developed melatonin receptor agonists are expected to be effective for delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD). To date, however, no study has described the effect of melatonin receptor agonists on DSWPD. We report the case of a 15-year-old girl with DSWPD who was successfully treated with ramelteon 4 mg at 7 pm. DSWPD symptoms were resolved; her sleep-wake and biological rhythms were normalized.

Keywords: Circadian rhythm sleep disorders, Sleep disorders, circadian rhythm, Melatonin, Sleep wake disorders

INTRODUCTION

Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD) is a circadian rhythm disorder characterized by persistent inability to fall asleep and wake up at conventional times. Treatment for DSWPD requires a multifactorial approach, including pharmacotherapy [1–4], chronotherapy [5], bright light therapy [6], and intervention with zeitgeber [7,8]. According to the current literature, melatonin is the preferred drug treatment for DSWPD [9]. However, reports on the effectiveness of melatonin for DSWPD have been inconsistent. Recently, the melatonin receptor agonist, ramelteon, has been developed. Ramelteon showed very high affinity for human MT1 and MT2 receptors [10]. MT1 reportedly regulates sleepiness, while MT2 is probably involved in the readjustment of the circadian rhythm [10,11]. Therefore, ramelteon is expected to be effective for DSWPD [12]. To date, however, no study has described the effect of melatonin receptor agonists on DSWPD. Here, we report the effects of a combination of ramelteon and bright light therapy on a patient with DSWPD. The patient provided written consent to publish this report.

CASE

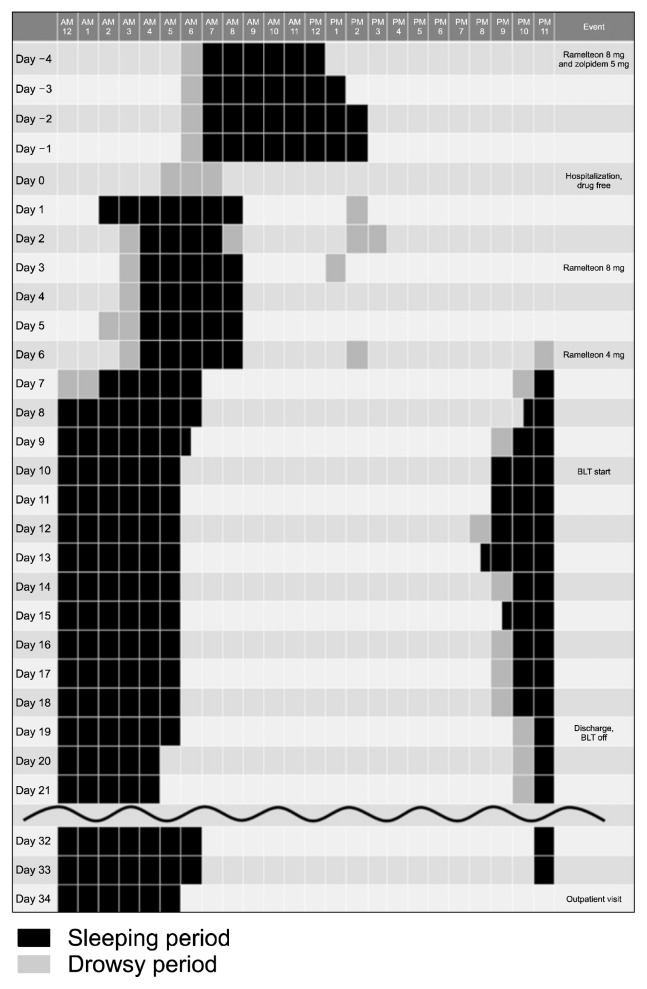

The patient was a 15-year-old girl. Her family and medical histories were unremarkable. On Day –290 (290 days before treatment initiation), at age 14 years, she developed difficulty falling asleep and difficulty waking for no known reason. She developed a sleep-wake rhythm of going to bed at 5 am and waking at 1 pm, and thus, she was late for school. On Day –20, at age 15 years, she visited our department for the first time with the chief complaint of difficulty falling asleep and difficulty waking up on time; subsequently, her condition was diagnosed as DSWPD according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition. After she and her parents agreed to off-label use of ramelteon for DSWPD with written consent, she was administered ramelteon 8 mg at 8 pm and zolpidem 5 mg at 11 pm. Her condition showed no improvement after administration. Therefore, she was admitted to our department (Day 0). At admission, her score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale was 7 and her Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire score was 21. The hospital follows a policy of lights out at 9 pm and lights on at 6 am, and the patient was instructed to comply with the activity rhythm of the hospital. During hospitalization, we monitored the sleep-wake rhythm of the patient using a sleep log and an actigraph (Octagonal Basic Motionlogger Actigraph; Ambulatory Monitoring Inc., Ardsley, NY, USA), and her biological rhythm was monitored by measuring the rectal temperature (Skin Temp & Humidity Logger LT8; Gram Corporation, Saitama, Japan). The sleep-wake rhythm of the patient using a sleep log before and after treatment is shown in Figure 1. Ramelteon and zolpidem were discontinued at admission and her progress was monitored. On Days 0 to 2, she fell asleep at 4 am and woke up at 9 am and napped during the day. The mean nadir rectal temperature was recorded at 7 am. Accordingly, from Day 3, ramelteon 8 mg was administered at 7 pm. Subsequently, the mean nadir rectal temperature shifted to 6 am on Days 3 to 5, which indicated a shift in the biological rhythm of the patient by 1 hour; however, no significant difference was observed in her sleep-wake rhythm. In a previous study investigating the phase advance effect of ramelteon on healthy adults, ramelteon 1, 2, and 4 mg ingested 30 minutes before going to sleep moved the biological clock phase forward compared to a placebo; further, no significant difference was observed between the group that received ramelteon 8 mg and the placebo group [13]. Therefore, we reduced the dose of ramelteon on Day 6 to 4 mg at 7 pm. The delayed sleep phase shifted forward after reducing the ramelteon dose, and on Day 8, she had a sleep-wake rhythm of falling asleep at 10:30 pm and waking up at 6:30 am. In addition, the nadir rectal temperature shifted forward to 4 am on Days 6 to 8. On Day 10, the patient was subjected to irradiation of 10,000 lux of high-intensity white light from 6 am to 8 am. On Day 13, the nadir rectal temperature further shifted forward to 3 am. The patient was discharged on Day 19. She did not use the bright light therapy at home but continued administration of ramelteon 4 mg at 7 pm. The patient was examined as an outpatient on Day 34 and was found to have remained in remission.

Fig. 1.

The sleep-wake rhythm of the patient using a sleep log before and after treatment.

BLT, bright light therapy.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that ramelteon is effective for the treatment of DSWPD. Consistent with the previous study investigating the phase advance effect of ramelteon on healthy adults [13], our results showed that unlike ramelteon 8 mg administered at 7 pm, ramelteon 4 mg at 7 pm effectively moved forward the sleep-wake rhythm and the biological clock of the patient. Thus, ramelteon 4 mg may be more effective than ramelteon 8 mg for patients with DSWPD, similar to findings observed in healthy adults. Further studies are warranted to investigate the appropriate dosage and timing of ramelteon administration for DSWPD.

The Zeitgeber effect, as in the hospital’s policy of standard lights-off and lights-on times, may have contributed to the remission in this case. Iwamitsu et al. [8] reported that more than 90% of DSWPD patients with school refusal experienced improved sleep-wake rhythm just after hospitalization. In this case, the sleep-wake rhythm and the biological clock of the patient did not markedly improve by hospital admission but required the addition of ramelteon and bright light therapy in the morning, which causes phase advance. Thus, combined use of ramelteon and bright light therapy under hospitalization may enhance the therapeutic effect for DSWPD.

The phase advance effect of hypnotics, such as zolpidem, on DSWPD has not been well investigated [9]. There are several reports describing the effect of hypnotics on DSWPD, but the results are not consistent [14–18]. Thus, the clinical practice guideline does not recommend the use of hypnotics for the treatment of DSWPD [9]. In the future, randomized placebo-controlled trials should investigate the effect of hypnotics on DSWPD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Masahiro Takeshima, Hiroyasu Ishikawa. Data acquisition: Masahiro Takeshima. Writing—original draft: Masahiro Takeshima. Writing—review & editing: Masahiro Takeshima, Hiroyasu Ishikawa, Takashi Kanbayashi, Tetsuo Shimizu.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Geijlswijk IM, Korzilius HP, Smits MG. The use of exogenous melatonin in delayed sleep phase disorder: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2010;33:1605–1614. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.12.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okawa M, Takahashi K, Egashira K, Furuta H, Higashitani Y, Higuchi T, et al. Vitamin B12 treatment for delayed sleep phase syndrome: a multi-center double-blind study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51:275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omori Y, Kanbayashi T, Sagawa Y, Imanishi A, Tsutsui K, Takahashi Y, et al. Low dose of aripiprazole advanced sleep rhythm and reduced nocturnal sleep time in the patients with delayed sleep phase syndrome: an open-labeled clinical observation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1281–1286. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S158865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxvig IW, Wilhelmsen-Langeland A, Pallesen S, Vedaa O, Nordhus IH, Bjorvatn B. A randomized controlled trial with bright light and melatonin for delayed sleep phase disorder: effects on subjective and objective sleep. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31:72–86. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeisler CA, Richardson GS, Coleman RM, Zimmerman JC, Moore-Ede MC, Dement WC, et al. Chronotherapy: resetting the circadian clocks of patients with delayed sleep phase insomnia. Sleep. 1981;4:1–21. doi: 10.1093/sleep/4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueiro MG. Delayed sleep phase disorder: clinical perspective with a focus on light therapy. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:91–106. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S85849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamanaka Y, Waterhouse J. Phase-adjustment of human circadian rhythms by light and physical exercise. J Phys Fit Sports Med. 2016;5:287–299. doi: 10.7600/jpfsm.5.287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwamitsu Y, Ozeki Y, Konishi M, Murakami J, Kimura S, Okawa M. Psychological characteristics and the efficacy of hospitalization treatment on delayed sleep phase syndrome patients with school refusal. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2007;5:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2006.00252.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auger RR, Burgess HJ, Emens JS, Deriy LV, Thomas SM, Sharkey KM. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of intrinsic circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders: advanced sleep-wake phase disorder (ASWPD), delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD), non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disorder (N24SWD), and irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder (ISWRD). An update for 2015: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1199–1236. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K, Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, Ohkawa S, et al. Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubocovich ML. Melatonin receptors: role on sleep and circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep Med. 2007;8(Suppl 3):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams WP, 3rd, McLin DE, 3rd, Dressman MA, Neubauer DN. Comparative review of approved melatonin agonists for the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:1028–1041. doi: 10.1002/phar.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson GS, Zee PC, Wang-Weigand S, Rodriguez L, Peng X. Circadian phase-shifting effects of repeated ramelteon administration in healthy adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:456–461. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.27282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito A, Ando K, Hayakawa T, Iwata T, Kayukawa Y, Ohta T, et al. Long-term course of adult patients with delayed sleep phase syndrome. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1993;47:563–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1993.tb01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta T, Iwata T, Kayukawa Y, Okada T. Daily activity and persistent sleep-wake schedule disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16:529–537. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(92)90058-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki N, Iwata T, Itoh A, Ohta T, Okada T, Kasahara Y. A treatment trial of delayed sleep phase syndrome with triazolam. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1989;43:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1989.tb02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuma H, Miyahara Y, Sakamoto T, Kotorii T, Nakazawa Y. Two cases of delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;45:163–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamadera H, Takahashi K, Okawa M. A multicenter study of sleep-wake rhythm disorders: therapeutic effects of vitamin B12, bright light therapy, chronotherapy and hypnotics. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;50:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1996.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]