Abstract

Ordered protein assemblies are attracting interest as next-generation biomaterials with a remarkable range of structural and functional properties, leading to potential applications in biocatalysis, materials templating, drug delivery and vaccine development. This Review covers ordered protein assemblies including protein nanowires/nanofibrils, nanorings, nanotubes, designed two- and three-dimensional ordered protein lattices and protein-like cages including polyhedral virus-like cage structures. The main focus is on designed ordered protein assemblies, in which the spatial organization of the proteins is controlled by tailored noncovalent interactions (including metal ion binding interactions, electrostatic interactions and ligand–receptor interactions among others) or by careful design of modified (mutant) proteins or de novo constructs. The modification of natural protein assemblies including bacterial S-layers and cage-like and rod-like viruses to impart novel function, e.g. enzymatic activity, is also considered. A diversity of structures have been created using distinct approaches, and this Review provides a summary of the state-of-the-art in the development of these systems, which have exceptional potential as advanced bionanomaterials for a diversity of applications.

1. Introduction

Nature exploits protein assemblies of different types, ranging from viruses to microtubules and bacterial pili to large protein assemblies and bacterial S-layers. Extended protein assemblies are structural components of the extracellular matrix and biofilms for example, as well as cell motility structures. Many viruses and bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) comprise ordered protein assemblies forming cages (discussed further in Section 5 below) around nucleic acids in the case of viruses or proteins in the case of BMCs, although other classes of viruses have extended assemblies (several are mentioned in Sections 2 and 3 below). Proteins can also assemble around metal centers, for example in heme proteins, or they can form large multicomponent assemblies such as ribosomes. Advances in the understanding of computational protein design and genetic engineering methods have recently enabled the rational design of protein subunit structures to form regular 1D-, 2D- and 3D- superstructures including nanowires, nanotubes, 2D and 3D lattices and cage structures. This Review describes research in the field of engineered protein nanostructures, and summarizes the various methods that have been employed to fabricate such ordered protein assemblies. We do not consider natural protein assemblies, although modified variants are discussed. Also not included is a discussion of natural protein crystal structures, obviously a huge separate subject in its own right.

Engineered protein assemblies are attractive for future applications due to their potential for large scale biosynthesis and their biofunctionality and biocompatibility. New emergent properties are expected from the nanostructured materials. Nanowire and nanotube structures may be created that have potentially valuable structural or (opto-) electronic properties. Assemblies based on enzymes may have enhanced catalytic behavior. Synthetic vaccines can be designed that are inspired by, or based on, existing virus structures. Other applications for protein cages may exploit their potential to encapsulate cargo.

In the most typical approach, fusion protein assemblies are created with predefined symmetry elements in order to define the directionality of the superstructure.1−12 Less commonly, proteins or peptides may be covalently linked (via flexible peptide or other spacers) in order to preimpose directionality of assembly.13,14

In a different approach, noncovalent interactions can be employed by modification of specific residues at the protein surface to enable π–π stacking15−18 or metal ion coordination,19−22 for example. Again, the position and relative orientations of modification sites have to be chosen to design protein assemblies with specific symmetries which lead to defined superstructures. Alternatively, host–guest ligand–receptor interactions may be employed.15−17,23 In the simplest case, binary structures can be formed through electrostatic interactions.24−34

The topic of ordered protein assemblies has been the focus of a number of previous reviews,35−41 and has been touched upon in broader reviews of protein-based materials.42 Here, the state-of-the-art in this emerging field is summarized and exemplified by selected works which elegantly highlight the precision control of nanoscale protein assemblies that can be achieved using advanced design and synthesis methods.

2. Nanofibril and Nanoring Structures

Linear arrays of proteins, i.e., nanofibrils or nanowires, result from one-dimensional (1D) assembly through suitable binary head–tail interactions such as lock-and-key or ligand–receptor interactions or complementary binding interactions. As an example of assembly guided by ligand–receptor/lock-and-key interactions, linear structures have been constructed through cucurbit[8]uril, CB[8], host–guest interactions.23 Dimers of glutathione S-transferase (GST) were modified at the two N-termini with the tripeptide FGG which forms a host–guest complex with CB[8] with high binding constant. The resulting nanowires were characterized by diameters of 5 nm and were tens of nm in length.

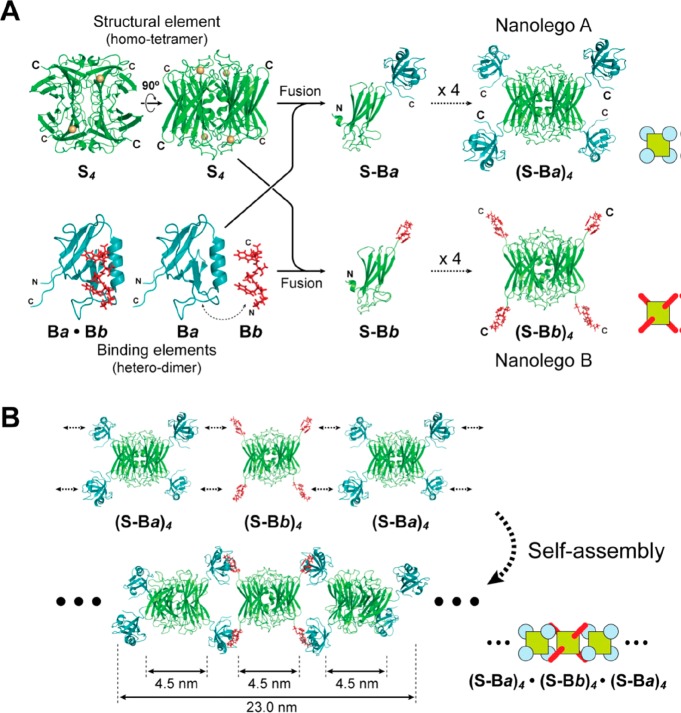

Using complementary binding peptide interactions, Usui et al. created so-called “nanolego” building blocks based on pairing of homotetrameric proteins modified at each of the four subunit C-termini by a peptide (Figure 1a).1 Two protein fusion building blocks each containing four corner peptides were produced, the two types having complementary binding peptide units (Nanolego A and B, Figure 1a). Self-assembly of a mixture of the two leads to linear aggregation and nanofibril formation (Figure 1b). The tetrameric protein scaffold was a superoxide reductase (SOR) and the peptide units were either a mouse PDZ (signaling protein) domain or a PDZ-binding peptide (these two reversibly associate with high binding affinity). In a further development, the PDZ peptides were modified with cysteine mutations to enable stepwise extension of the aggregates based on disulfide bond formation. Finally, the fabrication of finite length aggregates (3-mers) was studied by introducing capping units with only two of the four binding units.1

Figure 1.

(a) Concept to construct Nanolego A and Nanolego B building blocks from the homotetrameric S4 protein (superoxide reductase) modified with peptides Ba and Bb (PDZ domain peptide and PDZ-binding peptide) by creating fusion proteins using the subunit C-termini (shown). (b) Pairwise linear self-assembly leads to nanofibril formation. Reproduced from ref (1) with permission of John Wiley and Sons. Published by Wiley-Blackwell. Copyright 2009 The Protein Society.

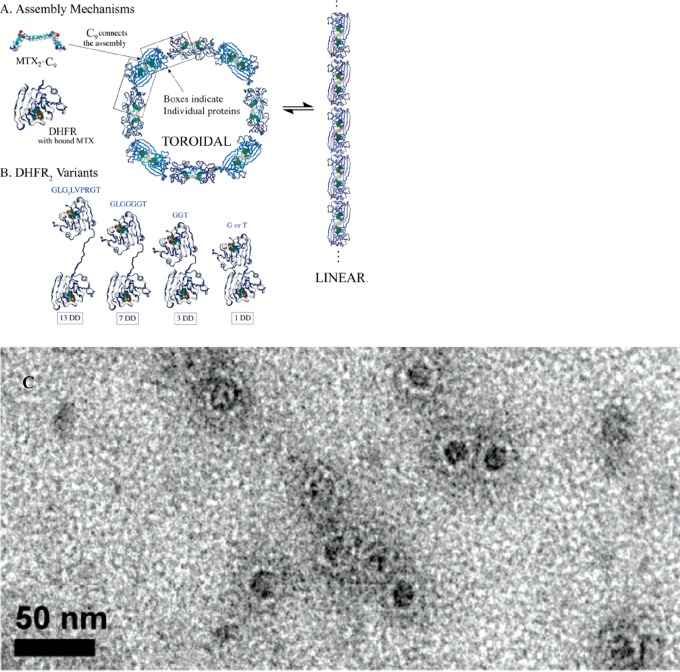

Protein nanorings have been created using chemical inducers of protein dimerization, for example using a dimeric methotrexate MTX2-C9 which has high binding affinity for dihydrofolate reductase, DHFR (which was modified with extended linkers between the two subunits).43 Methotrexate is a therapeutic molecule used in chemotherapy and the treatment of automimmune diseases including arthritis, which acts by inhibiting DHFR. Figure 2a,b show the proposed assembly mechanism along with the DHFR2 variants prepared, while Figure 2c shows a representative TEM image of nanorings (20–28 nm in outer diameter). The closure into ring structures with defined sizes (i.e., number of subunits) is proposed to result from the balance between conformational flexibility and the entropy of oligomerization.43 The same group has demonstrated ring structures with 8–30 nm diameter using fusion proteins DHFR-Hint1 (dihydrofolate reductase-histidine triad nucleotide binding) with a variable length peptide spacer between the Hint1 unit and the DHFR protein.2 These fusion proteins were polymerized with a dimeric enzyme inhibitor molecule. The ratio of intra- to inter-molecular polymerization could be controlled via adjustment of fusion protein concentration, leading to oligomers containing 2–12 monomers. Intermolecular cyclization was also favored by reduction of the length of the linking peptide.2

Figure 2.

(A) Nanoring (toroid) formation using(bis-methotrexate MTX2-C9 binding to Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase variants with extended spacers between the two subunits (B). (C) TEM image showing nanorings assembled in a solution of 1DD-G with MTX2-C9. Reproduced with permission from ref (43). Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

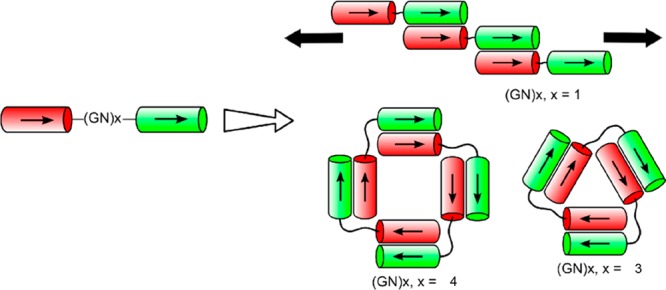

Small tetramer and trimer oligomers (“nanorings”) can be made from complementary coiled-coil forming peptides joined by a disordered flexible (GN)x peptide linker (Figure 3).14 Parallel dimeric coiled-coil formation favors the trimeric and tetrameric structures, which were detected by analytical ultracentrifugation. The peptides with the shortest linker GN1 formed fibril structures (Figure 3), as imaged by TEM.14 Peptide fibril structures are not considered further in this section, as this subject has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.44−47

Figure 3.

Dimeric coiled coil peptides with a flexible (GN)x linker between the two complementary helical peptides can form extended fibrils (x = 1), triangular trimers (x = 3) or square tetramers (x = 4). Reproduced with permission from ref (14). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

The rod-shaped M13 bacteriophage has been used as a nanowire template scaffold for a variety of applications. In one example, photocatalytic structures based on chemical grafting of photosensitizer and catalyst molecules to the M13 major coat protein p8 was reported.48 The M13 bacteriophage comprises approximately 2700 copies of α-helical coat proteins arranged around the viral DNA. Proteins with either chemically linked zinc porphyrin photosensitizer or an iridium oxide catalyst (attached noncovalently using an IrO2-binding peptide) were coassembled, producing fiber (nanowire) structures. Light-driven water splitting was observed to be catalyzed by the assemblies.48 The same strategy was used to produce cobalt oxide nanowires using p8 coat proteins modified with metal ion-binding tetra-glutamate sequences.49 Additional incorporation of gold-binding peptide produced hybrid gold–cobalt oxide wires as electrodes, which improved the charge storage capacity of model lithium ion batteries.49 In a further development, the M13 bacteriophage has been genetically engineered to incorporate a terminal peptide that binds single wall carbon nanotubes (SWCTs) and to incorporate peptides within the major coat protein that bind amorphous iron phosphate. These iron phosphate-based nanowire materials demonstrated excellent performance as cathodes for lithium ion batteries.50 An engineered M13 bacteriophage was also developed to produce a Co–Pt hybrid material with superparamagnetic properties.51 Another recent example involves the use of M13 bacteriophages as scaffolds for metal deposition onto nanofoam meshes prepared by glutaraldehyde cross-linking of M13 modified with a glutamic-acid rich peptide at the N-terminus.52 The free-standing metal nanofoams prepared may have use in the development of novel electrodes.

Nanorings can be created by coassembly of modified M13 bacteriophages and linker molecules.53 The M13 bacteriophage was genetically engineered to incorporate antistreptavidin and hexahistidine peptides at opposite ends. Stoichiometric addition of streptavidin-NiNTA (Ni(II)-nitriloacetic acid hexahistidine-binding motifs) linkers led to the reversible formation of nanorings.53 Work on M13 bacteriophage and other viruses as scaffolds for nanomaterials development has been reviewed.54

Electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged proteins can drive assembly into nanoring structures. In a recent example, supercharged Cerulean and GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) variants were mixed to form toroid (nanoring) structures comprising two stacked octameric rings, as revealed by high resolution cryo-EM.30

3. Nanotube Structures

In this section, protein nanotubes created by design or modification of natural nanotube structures (rod-like viruses in particular) are considered. Peptide nanotube structures are not discussed in this section, this topic having been the subject of several recent reviews.55−60

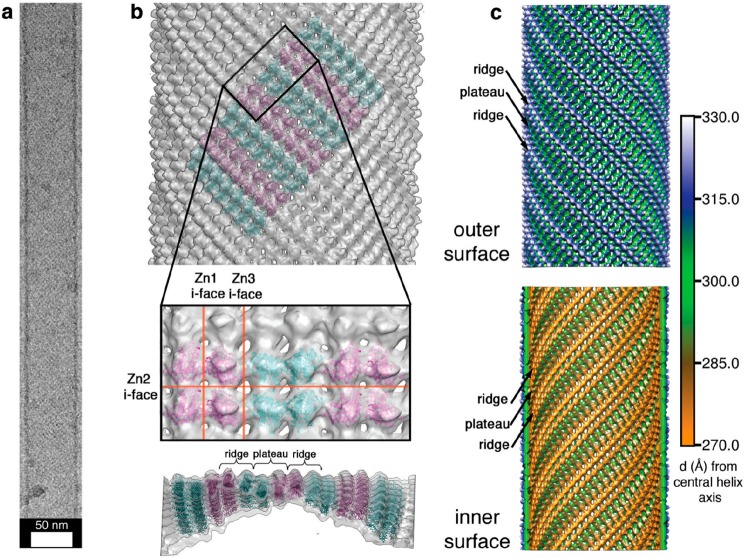

A subunit of cyotochrome c that comprises a four-helix-bundle haem protein has been used as a stable building block to produce nanotube and two- or three-dimensional (2D, 3D) crystalline structures via metal-coordination interactions.19 A variant of the protein modified to present two metal-binding bis-histidine motifs on its surface forms a C2-symmetric dimer structure stabilized by Zn2+ binding. Furthermore, one Zn2+ binding site is left open to binding by another dimer, the binding sites being positioned to favor orthogonal assembly, leading to helical chains. Appropriate solution conditions (high pH or low pH and high relative Zn2+ ion concentration) lead to fast formation of nanotubes, whereas the opposite conditions lead to slow nucleation into 2D and 3D crystals. Figure 4 shows a cryo-EM image with a model for the helical arrangement of the tetrameric (Zn2+-linked pair of dimers) building unit.19 The same cytochrome c variant was later coupled via cysteine cross-linking to produce a dimer which was used to construct a tetrameric aggregating unit via Zn2+ coordination.19 The tetrameric dimer wraps helically to form the walls of nanotubes, of two types, which were observed according to the solution conditions (pH, buffer and Zn2+ excess). Slow nucleation conditions lead to the formation of 2D- and 3D- crystals in this system, as discussed in Section 4.

Figure 4.

Nanotube structure from assembly of a designed cytochrome-based protein subunit.19 (a) Cryo-TEM image of a representative nanotube. (b) Helical arrangement of tetrameric proteins into a nanotube structure stabilized by zinc ion coordination at the interfaces (i-faces) shown, Zn1 for example denotes the dimer of C2-symmetric dimers forming the tetrameric building block. (c) Models for the outer (top) and inner (bottom) nanotube surfaces showing ridges and plateaus as shown side-on in panel b. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (19). Copyright 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/nchem/.

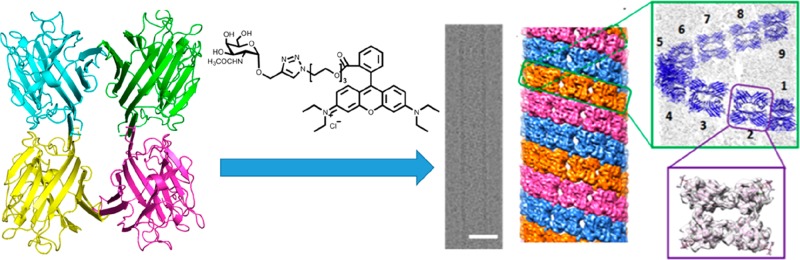

The formation of nanotubes was observed by inducing the association of the homotetrameric protein soybean agglutinin (SBA) using a ligand containing both a galactose-based sugar unit to bind the protein and an aromatic motif (Rhodamine B, RhB) to drive π–π stacking interactions (Figure 5).15 A model for the helical wrapping of the proteins to form the nanotube wall could be obtained, based on electron tomographic imaging. The nanotube growth kinetics can be changed by temperature adjustment and the nanotubes could be dissociated by adding β-cyclodextrin which binds the RhB.15 These structures resemble protein microtubule structures which are formed from dimers of the protein tubulin and have an outer diameter 24 nm and lengths up to tens of micrometers. Microtubules are involved in mitosis and this, for example, is the basis of the activity of the anticancer drug Taxol which hinders microtubule depolymerization, promoting the arrest of mitosis and death of cancer cells.61,62

Figure 5.

Soybean agglutinin (SBA) is a homotetrameric protein with D2 symmetry. Addition of designed ligands incorporating a galactosamine (shown) or galactopyranoside unit able to bind SBA linked to a Rhodamine B unit able to undergo π–π stacking interactions, drives protein association, leading to helical wrapping into nanotubes (scale bar = 25 nm). Reproduced with permission from ref (15). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) has a rod-like structure, consisting of an array of coat proteins wrapped around an RNA core, leading to a nanotube capsid structure. This has been exploited to produce protein nanotubes by modifying the coat proteins, which has benefits because it is suggested that the display of antigens in a regular array leads to an enhanced immunogenicity compared to that induced by free proteins.63 Palmer and co-workers modified TMV coat proteins to enable biotinylation which then allows binding of streptavidin-tagged proteins, exemplified with GFP and an N-terminal fragment of the canine oral papillomavirus L2 protein. In both cases, nanotube structures which elicited higher immunogenic response than unconjugated (and unassembled) protein were observed.63 In a similar fashion, an S123C mutant TMV coat protein has been used as a handle to attach electron donor and acceptor fluorescence chromophores, creating a scaffold for light harvesting.64,65 Unmodified TMV has a negatively charged surface and this has been used to template the deposition of cationically modified gold nanoparticles via electrostatic interactions, leading to the formation of twisted fiber bundle structures.34 Magnetic alignment of these structures yielded a plasmonic polarizer.

It is possible to design peptides that adsorb to particular species or surfaces. Using this inherent design flexibility, DeGrado’s group have developed antiparallel homohexameric coiled coil peptides that assemble into nanotubes around SWCTs.66 The peptides incorporate hydrophobic units, for example the Cβ methyl of Ala, to facilitate binding to the hexagonal array of carbon atoms at the nanotube surface.

4. 2D and 3D Crystal Structures

Planar assembled protein structures exist in nature, for example S-layers are monolayers of (glyco)protein structure in the membrane of archaea and certain bacteria.67 S-layer protein structures have been reconstructed using tetrameric fusion proteins comprising one of a number of S-protein fragments and three streptavidin units.3 It was shown that these engineered constructs can form planar (oblique) lattice structures on flat surfaces or on cell wall polymer-containing cell wall fragments. The regular display of the streptavidin units enables binding of biotin and biotinylated protein such as ferritin in a regular pattern.3 It has been suggested that the periodic structure of S-layers is ideal for the development of affinity matrices used in DNA, protein or antibody detection chips.68 S-layer proteins have also been examined in vaccine development, due to the ability to present antigens at surfaces, along with adjuvant properties.68 S-layer structures additionally have potential in the development of immobilized biocatalysts, this having been demonstrated with fusion constructs incorporating extremophile enzymes.69,70 The fluorescent protein GFP has been incorporated into S-layer fusion proteins, enabling the creation of fluorescent biomarkers, pH indicators and the fluorescence imaging of the uptake of S-layered liposomes into cells.68 Nanoparticle arrays can also be templated using the periodic structure of S-layers, modified to display gold-binding cysteine residues,71 or utilizing S-layer pores to grow cadmium sulfide quantum dots.72 Further details on these applications can be found in a review on S-layer structures.68

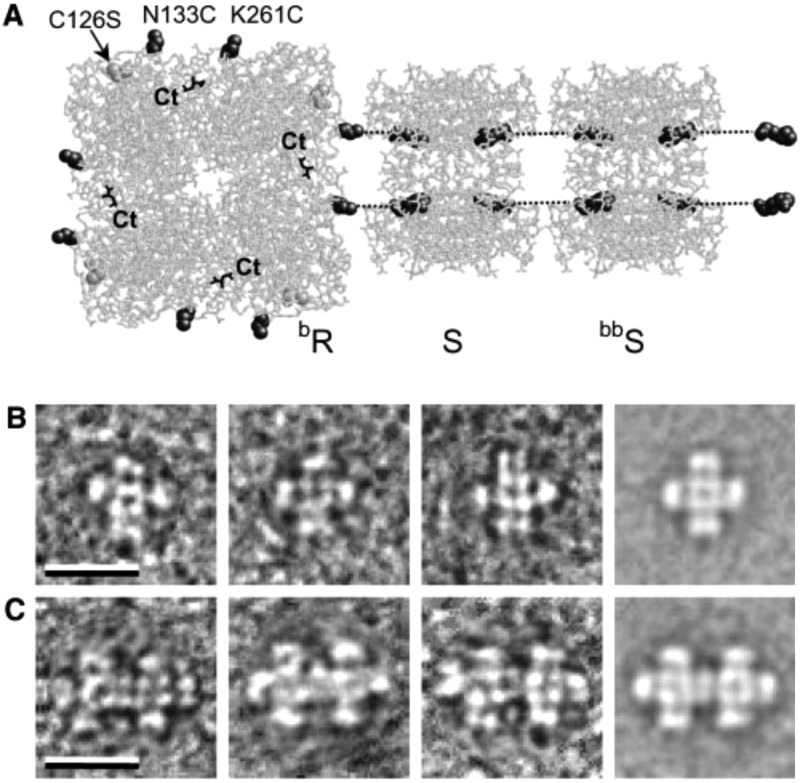

Small cross-shaped aggregates (Figure 6) have been created using the C4-symmetric tetrameric catalytic protein RhuA, l-rhamnolose-phosphate aldolase.73 Each aldolase subunit was modified with a His6 tag for oriented binding to a planar surface as well as two tethered biotin uses to bind streptavidin with defined orientation. TEM revealed the presence of the expected cross-shaped network aggregates (Figure 6) on lipid monolayers when mixing biotinylated RhuA (bR) and bR modified with four streptavidins (bR.S4). The size of the small aggregates could be expanded by adding spacers of bis-biotinylated streptavidin (bbS, Figure 6). Rod spacers created by mixing bbS and S led to extended string-like structures.73 In a further development, the authors incorporated a Ca2+-binding β-helix fragment of the enzyme serralysin between two PGAL (6-phospho-β-galactoside) proteins in a PGAL-β-PGAL construct and showed Ca2+-dependent switching, with a change in the separation of the two domains in the dumbbell-shaped fusion construct.73

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic to show modification of protein RhuA with eight biotins (bR), showing two of them binding to streptavidin (S), this in turn binding to biotinylated streptavidin linkers (bbS). The C terminal (Ct) units are highlighted; these are sites for hexahistidine tagging. (b,c) Representative TEM images of aggregates of bR and bR.S4 on lipid monolayers. The scale bars indicate 200 nm. From ref (73). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/302/5642/106.

The importance of designing the correct interface between proteins in multiprotein assemblies has been emphasized by several groups.24,74−76 Grueninger et al. emphasized the importance of rigid side chain contacts and they designed mutants of proteins with such enhanced contacts.74 In particular, they modified monomeric PGAL to favor dimer formation by enriching contacts across local 2-fold axes and also produced tetramers from dimeric O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase (Oas) and urocanase (Uro) and modified tetrameric RhuA to favor pairwise association at the C4 axis surfaces. They also adapted the mycobacterial porin MypA to give a D8-symmetric unit forming tail–tail dimers. Figure 7 shows the modified protein structures along with the symmetry axes (and Figure 7d shows a TEM image showing linear association of the modified RhuA tetramer shown in Figure 7b).74 RhuA was used as a building block for 2D lattice assembly in a study where aggregation was controlled via several types of interaction via selective protein mutations.20 Specifically, single-disulfide, double-disulfide or double-histidine (metal coordinating) mutants were prepared. The self-assembly process is reversible via oxidation/reduction (of disulfide interactions between cysteines) or using EDTA, a zinc ion chelator in the case of the double-histidine variant. Figure 8 shows the 2D lattices resulting from the assembly process which have different symmetries and a high degree of regularity. The C89RhuA variant was observed to form a number of defect-free 2D lattice polymorphs as a result of the dynamic single disulfide bond flexibility. This material shows ideal auxetic behavior, undergoing longitudinal expansion upon transverse stretching.20 Recent all-atom molecular dynamics simulations suggest that the free-energy landscape of these lattices is governed by solvent reorganization entropy.77

Figure 7.

Modification of protein interfaces (mutations marked by purple spheres) to favor small oligomers.74 (a) Crystal structure of C2-symmetric UroA tetramer showing the 2-fold molecular symmetry axis (red) and four local 2-fold axes relating the cores (black lines). (b) Octamer formed by dimerization of RhuA dimer with D4 symmetry. (c) RhuB octamer with C2 symmetry. (d) Negative stain TEM image of RhuE showing assembly of fibers, the inset scale bar shows a RhuA octamer to scale. (e) Native mycobacterial porin, with the deleted membrane-immersion part indicated by the box, giving MypA. (f) D8-symmetric assembly of two MypA molecules (top and bottom rings). The positions of the 52-residue deletions are marked by red spheres. From ref (74). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/319/5860/206.

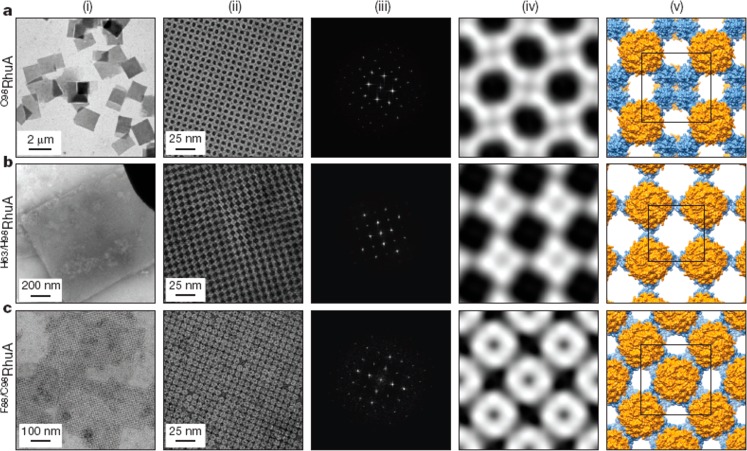

Figure 8.

Distinct 2D lattices formed by the indicated RhuA mutants. (i) Low magnification TEM images, (ii) High magnification TEM images. (iii) Fourier transforms of images in column ii. (iv) Reconstructed 2D images from the Fourier transforms. (v) Structural models based on iv. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (20). Copyright 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/.

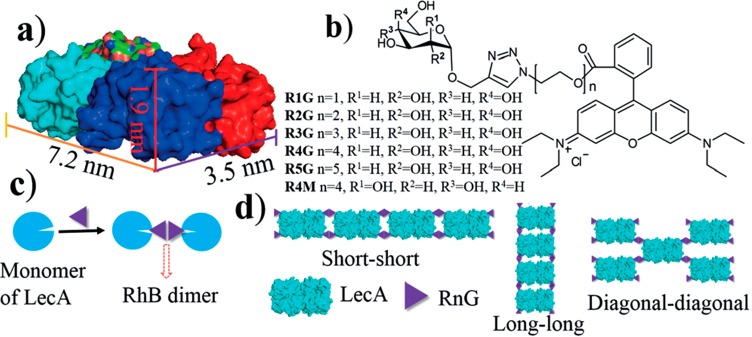

Two-dimensional crystals as well as nanoribbon and nanowire structures were observed using the homotetrameric protein LecA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa.16 LecA is galactose-specific (which influences its infectivity) and mixing LecA assembly-inducing ligands containing galactopyranoside derivatives with pendant rhodamine B (RhB) units induces association of the proteins due to π–π stacking of the RhB units (cf. Figure 5 and associated discussion in the preceding section). Several stacking modes are possible depending on the ligand spacer length, which influences the geometry of π–π stacking interactions (Figure 9). This leads to assembly into the observed ribbon, 2D crystal or nanowire structures.16 Three-dimensional crystal structures can be formed by exploiting the sugar-lectin binding and π–π stacking interactions, using concanavalin A (con A), a homotetrameric protein with D2 symmetry and mannose or lactose-based ligands incorporating aromatic Rhodamine B units to drive dimerization via π–π stacking (cf. for example Figure 5 and Figure 9).17 Platelet-shaped crystals were noted, and single crystal X-ray diffraction enabled determination of the distinct structures of the crystals formed with different ligand linkers.17

Figure 9.

Galactose-based ligand-driven assembly of LecA homotetrameric proteins. (a) Structure of the LecA tetramer (protein data bank pdb id 4LKD). (b) Chemical structures of ligands RnG (n = 1 to 5) and R4M. (c) Illustration of dimerization. (d) Possible arrangements of LecA/RnG giving rise to different 1D and 2D nanostructures. Reproduced from ref (16) with permission of John Wiley and Sons. Copyright 2017 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

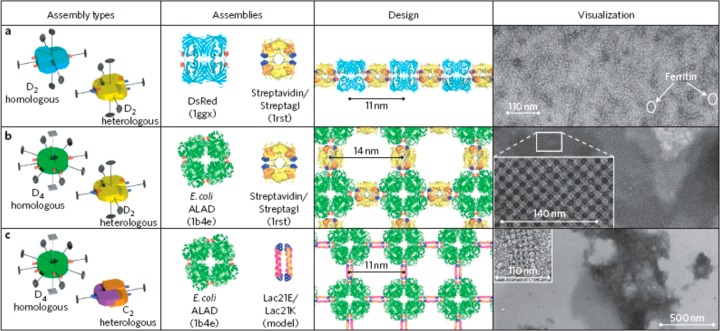

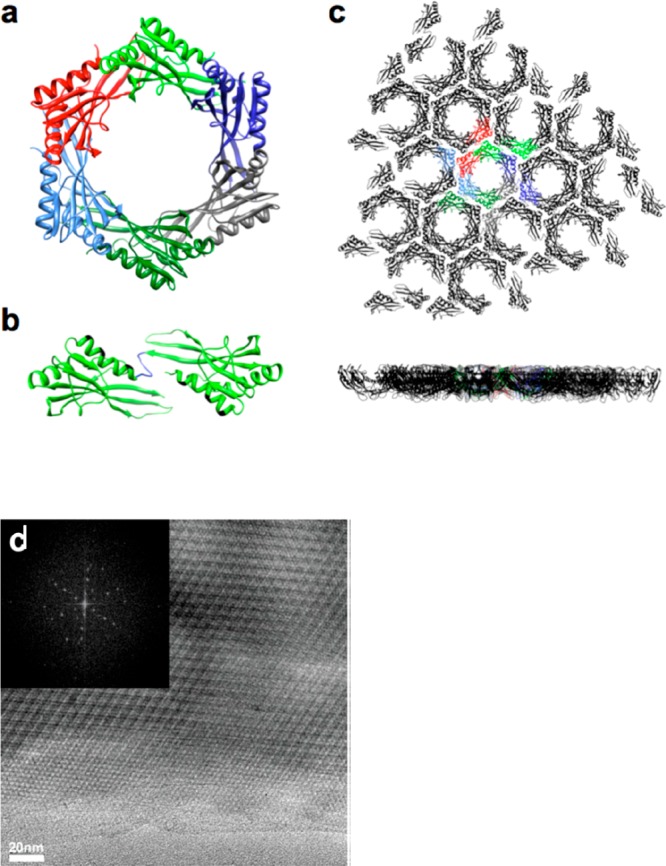

The methods discussed so far rely on protein site modification, chemical coupling, or production of fusion proteins with defined geometries to drive self-assembly. In contrast, Sinclair et al. developed a class of fusion protein comprising units taken from protein assemblies with different rotational symmetries, linked at their termini along one symmetry axis.4 The fusion constructs are suitable for high-level, soluble expression in E. coli. These can aggregate into 1D or 2D structures termed crysalins. The components may be homologous (comprising only one type of subunit) or heterologous (combined two types of subunit). Using streptavidin/Streptag I as heterologous D2 assemblies and DsRed as a homologous D2 assembly, linear assemblies were observed (Figure 10a) whereas combination of E. coli ALAD (ALAD: aminolevulinic acid dehydrogenase) as D4 homologous assembly and streptavidin/Streptag1 as D2 heterologous unit led to 2D lattices (Figure 10b). The same D4 homologous unit with Lac21E/Lac21K (heterotetrameric coiled coil peptides based on a Lac repressor protein sequence, stabilized by Glu/Lys interactions78) as a C2 building block led to a different 2D lattice (Figure 10c).4

Figure 10.

Fusion of protein assembly elements leads to 1D and 2D superstructures (termed crysalins). Left column: Schematic of assembly units showing symmetry elements. Second column: Protein/peptide components incorporated in fusion proteins. Third column: Designed structures. Right column: TEM images of observed structures. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (4). Copyright 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/nnano/.

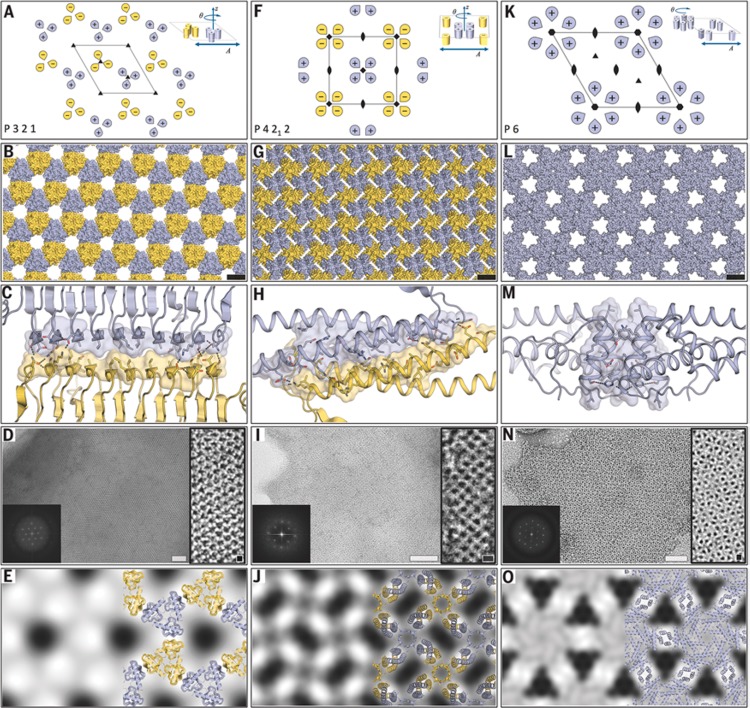

An alternative approach is de novo design of proteins to create 2D lattices. Gonen et al. used the Rosetta protein modeling software to design proteins to form 2D lattices with defined symmetries.75 Specifically, from among the 17 distinct 2D lattice structures that can be formed from 3D objects, they selected a subset with two unique interfaces and building blocks with internal point symmetry. The designed proteins were then expressed in genetically engineered E. coli and the structures assembled in solution were observed by cryo-TEM.75Figure 11 shows the targeted 2D lattices along with representations of the protein packings and the designed interface structures along with TEM images and projection maps with overlaid design models. The construct for the P321 lattice is a trimer of β-helices, that for the P4212 lattice is based on tetrameric α-helices, and that for P6 is based on α-helical hexamers.75 The same concept was used to design protein cage structures, as discussed further in Section 5.

Figure 11.

Creation of designed 2D lattices by protein design. (A, F, K) targeted lattices with (inset) protein subunit arrangements, (B, G, L) models for designed proteins packed into the lattices shown above, (C, H, M) designed interface structure for the corresponding lattice structure in the same column, (D, I, N) cryo-TEM images of expressed protein lattices (white scale bars = 50 nm, black scale bars = 5 nm), with inset Fourier transforms. (E, J, O) Calculated projection maps (14 or 15 Å resolution) with overlaid protein designs shown on the right of each image. From ref (75). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/348/6241/1365.

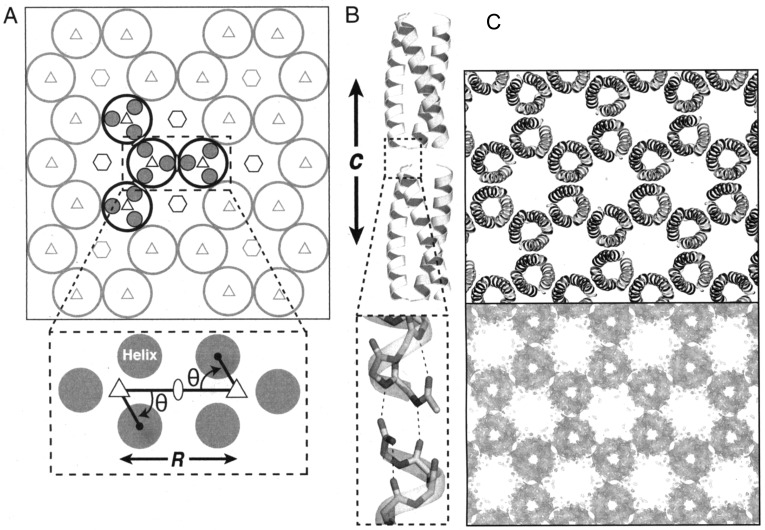

A novel route to porous 2D crystal structures was developed based on screening the protein data bank for small oligomeric proteins with defined rotational symmetry, with a central pore smaller than 5 nm, interfaces engineered to avoid steric clashes, flexible loops and termini oriented such that the C-terminus in one oligomer subunit can be linked via a short spacer to the N-terminus of a subunit in different oligomer (favoring interoligomer association).76 This concept was exploited with a dimeric protein from Salmonella typhimurium, STM4215 which forms a hexameric aggregate with a ∼3 nm pore (Figure 12a). The protein was engineered such that the subunits were linked with a six-residue linker (Figure 12b), leading to the formation of the 2D honeycomb lattice shown in Figure 12c. Self-assembly was induced by addition of calcium ions, since each subunit coordinates one Ca2+ ion. TEM observations confirmed the formation of the expected 2D honeycomb lattice (Figure 12d). Lanci et al. computationally designed a three-helix coiled coil peptide to form honeycomb (p6 symmetry) lattices, by designing a charged outer interface in a homotrimeric coiled coil (Figure 13a) to favor pairwise complementary electrostatic interactions between helices in neighboring peptides.24 A single crystal structure for the designed protein confirmed the intended designed structure (Figure 13b).24 Honeycomb lattices are discussed further in Section 5, since such structures have been observed (in the case of building blocks with flexible linkers) to curve into cage structures.76

Figure 12.

2D lattices with p6 symmetry from a modified hexameric S. typhimurium STM4215 protein TTM. (a) Ribbon structure showing native hexameric structure. (b) A dimer linked by an introduced short six-residue sequence (blue) with Rosetta designed modified interfaces (shown in black). (c) Top and side views of the expected 2D lattice with individual TTM dimers shown in different colors. (d) TEM image after incubating a protein sample with CaCl2 (inset: Fourier transform image showing hexagonal symmetry). Reproduced with permission from ref (76). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Figure 13.

Design of a honeycomb lattice from homotrimeric coiled coils. (a) Schematic of the p6 structure along with lattice symmetry elements, the parameters θ and R adjusted in the peptide design are shown in the bottom scheme. (b) Two layers of the peptides showing H-bonding at the interlayer interface facilitated by fixing the unit cell length c. (c) Electron density map from a single crystal structure (bottom) compared to a model structure (top). Reproduced from ref (24) with permission of the authors.

In a pioneering paper, Dotan et al. showed that cubic structures based on diamond lattices can be prepared by creating dimers of the lectin concanavalin A, which has a tetrameric structure.79 The proteins were dimerized using bis-mannopyranoside, leading to a dumbbell shaped dimer which packs into a diamond lattice due to the imposed configuration of the protein subunits. As mentioned in Section 3, a modified cytochrome protein comprising dimers of C2-symmetric dimers via histidine-mediated Zn2+-coordination that forms nanotubes can also assemble into 2D and 3D crystal structures under slow nucleation conditions.19

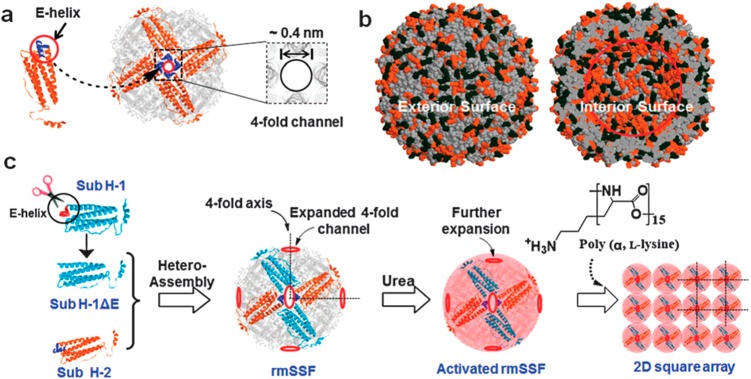

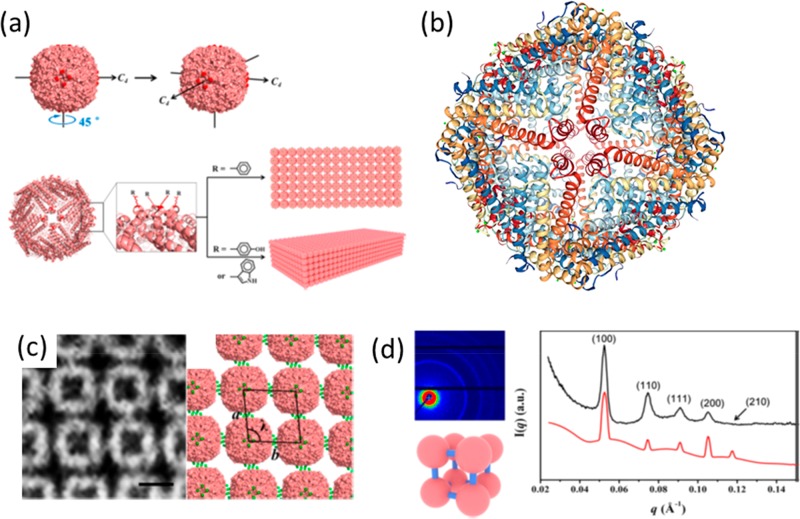

The protein ferritin is interesting for protein nanomaterials design due to its highly symmetric cage-like structure. Ferritins comprise 24 subunits which assemble into a pseudospherical shell with octahedral symmetry. Each subunit consists of a four α-helix bundle and a fifth short E-helix.25 The E-helices form the C4-symmetric channels (Figure 14), of which there are six in a ferritin shell (along with eight C3 axes). The channels in ferritin have sizes between 0.3 and 0.4 nm and allow the transport of small ions and molecules. Yang et al. expanded the C4-symmetric pore size (Figure 14) in mature soybean seed ferritin (mSSF) by E helix deletion from the H-1 half of the subunits (Figure 14).25 The expanded pore was able to accommodate poly(l-lysine) (degree of polymerization = 15), leading to tethering of the ferritin cages into a square array via electrostatic interactions (ferritin is rich in acidic residues).25 Zhou et al. have exploited the symmetry within the subunits of a ferritin protein in order to substitute aromatic residues located near the C4 symmetry axes (Figure 15a,b).18 The substitution of phenylalanine (F) or tyrosine (Y) residues at a single site within each of the 24 protein subunits was designed to induce directional aromatic stacking π–π interactions. These were shown to lead to the formation of planar 2D lattices of ferritin molecules in the case of F-substituted proteins (Figure 15c) or 3D cubic lattices in the case of Y-substituted proteins (Figure 15d) as shown schematically in Figure 15a.18

Figure 14.

(a) Schematic showing a ferritin C4-symmetry axis with pore, based on assembly of subunits shown on left with E-helix highlighted, (b) Surface charges on ferritin–orange spheres indicates negative charges and black spheres are positive charges, (c) Showing strategy to expand pore size by E-helix deletion from H-1 subunits in reconstructed mature soybean seed ferritin (rmSSF). The expanded pore size enables ingress of poly(l-lysine) which links proteins into a square array via electrostatic interactions. From Chemical communications by Royal Society of Chemistry (Great Britain). Republished with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from ref (25). Copyright 2014; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Figure 15.

2D and 3D assemblies by aromatic substitution within the 24-subunit ferritin protein cage structure. (a) Schematic of ferritin structure showing C4 rotation axes and substitution sites near these axes, leading to 2D and 3D lattices depending on the aromatic residue substituted at Glu162. (b) Showing one of the 4-fold symmetry axes of human H-chain ferritin (pdb file 2FHA).103 (c) Reconstructed image from FFT of a TEM image of a 2D oblique (rhombic) lattice for the phenylalanine substituted protein assembly. (d) SAXS pattern and one-dimensional intensity profile with indexed reflections corresponding to a simple cubic packed 3D structure (shown) for the tyrosine-substituted protein assembly. Parts a, c, d reproduced with permission from ref (18). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Three-dimensional protein crystals can be developed as the basis of a new type of metal–organic framework (MOF).21,22 The Tezcan group has developed MOFs based on ferritin arrays, initially substituting a Zn2+-binding histidine residue at residue 122 near to the C3 axis.21 The ferritin proteins were then noncovalently linked using benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, leading to bcc crystal structures.21 This work was extended to other divalent metal ions and alternative dihydroxamate linkers, leading to a range of MOFs with body-centered cubic or tetragonal lattices.22

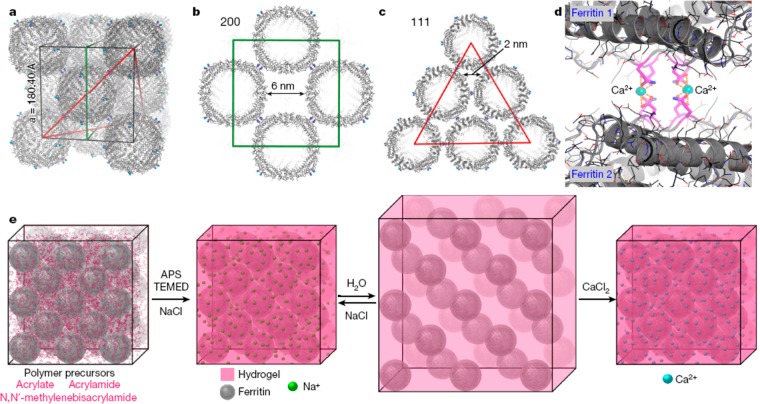

Native ferritin (human heavy chain) forms a fcc lattice (Figure 16a–c) mediated by Ca2+ K86Q interactions (Figure 16d). Tezcan and co-workers have shown that this lattice can be used as a template for polymerization of a polymer hydrogel network and that by appropriate choice of a responsive polymer, polymer gels containing embedded ferritin lattices that can be reversibly swollen by change of ionic strength or pH (Figure 16e).80 The polymer chosen was poly(acrylate-co-acrylamide) which was prepared by free radical polymerization in the presence of APS (ammonium persulfate) and TEMED (tetramethylenediamine) as initiators and with N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) as cross-linker, and NaCl was included to limit swelling during polymerization. Postpolymerization swelling was initiated by placement in deionized water (Figure 16e), leading to an increase in lattice parameter from a = 19 nm to a = 23 nm, determined by SAXS. The expansion was isotropic as confirmed by isotropic expansion of the faceted polyhedral gel crystals observed by optical microscopy. The gels exhibited self-healing behavior, for example cracks in the polyhedral crystals induced by ion-induced contraction were observed to spontaneously seal due to the dynamic nature of the bonds between polymer chains and ferritin proteins.80

Figure 16.

Concept of swellable protein-embedded polymer hydrogel crystals. (a–c) Showing fcc packing in ferritin crystals (Protein Data bank Identifier, pdb id 6B8F). (d) Ca2+-mediated interactions leading to the packing of ferritin proteins in the crystal lattice. (e) Schematic of polymerization around the ferritin lattice scaffold to produce a reversibly swellable hybrid polymer–protein crystal hydrogel structure. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (80). Copyright 2018 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/.

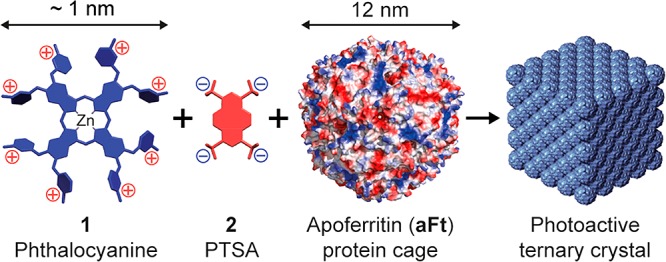

Complexes of a zinc phthalocyanine with eight cationic groups with a tetra-anionic pyrene derivative can bind to the anionic surface patches on ferritin (apoferritin), inducing crystallization into fcc packed cocrystals (Figure 17), with a lattice spacing a = 20 nm.81 The crystals retain the photoactivity of the phthalocyanine dye molecules including fluorescence and light-induced singlet oxygen production.

Figure 17.

Complexes form between a zinc phthalocyanine derivative 1 and the tetra-anionic pyrene derivative PTSA (1,3,6–8-pyrene tetra-sulfonic acid) 2. These complexes bind to anionic patches on the apoferritin protein surface, leading to the formation of cubic crystals which retain the photoactivity of the phthalocyanine dye. Reproduced with permission from ref (81). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

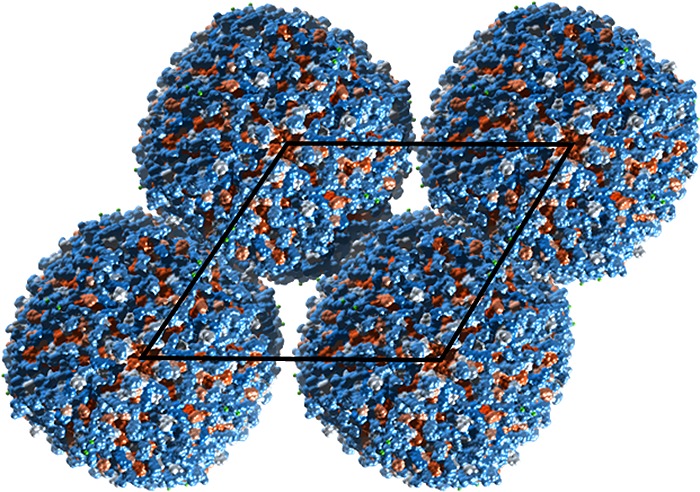

Simply using electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged proteins, it is possible to produce cocrystals of avidin (which has net negative charge) and cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) with a net positive charge, by mixing in aqueous solution.32 The crystals had a bcc structure with lattice spacing a = 35 nm. The use of avidin further enabled the pre- or post- assembly functionalization of the crystals with biotinylated molecules such as fluorescent dyes, enzymes or gold nanoparticles.32 In another example, binary crystals have been produced by cocrystallization of oppositely charged ferritin, surface modified with either basic (arginine or lysine) or acidic (glutamic acid or aspartic acid) residues.27 The binary crystal had tetragonal symmetry. Metal oxide nanoparticles could be sequestered within either or both protein cages. This concept was developed to show that the crystallization could be modulated by metal ion (Mg2+) concentration, the binary tetragonal lattice at low Mg2+ concentration being replaced with a unitary cubic lattice at high [Mg2+].82 In a related study, binary crystal structures were fabricated using mixtures of anionic proteins and cation-coated gold nanoparticles.31 The anionic proteins were cage-like ferritin (apoferritin or magnetoferritin) or CCMV, and these can encapsulate RNA or superparamagnetic iron oxide particles.

Electrostatic interactions can lead to the formation of a fcc lattice, as exemplified in mixtures of a P22 bacteriophage coat protein (virus-like particle, VLP) and a G6 (sixth generation) PAMAM dendrimer.28,83 PAMAM dendrimers are cationic poly(amido amine) particles. The P22 bacteriophage coat protein (CP) was modified with a short anionic peptide (VAALEKE)2 at the C terminus, producing an anionic particle. Mixing in appropriate proportions in suitable ionic strength conditions leads to the formation of a cubic lattice. Alternatively, amorphous aggregates could be prepared using a ditopic protein linker that binds the CP at multiple symmetry-specific sites. This linker can also be used to “cement” the ordered cubic structures formed in mixtures with PAMAM dendrimers, stabilizing the assembly against increase in ionic strength.28 Fusion proteins of the P22 CP with the enzymes ketoisovalerate decarboxylase (KivD) or alcohol dehydrogenase A (AdhA) formed capsid structures similar to those of the unmodified CP.83 The enzymatic activity was found to be retained in the G6 dendrimer-modified CP assemblies, enzymes being confined within the VLPs. In a similar fashion, PAMAM dendrimers can be used to produce binary crystal structures (with hcp or fcc structure) with ferritin.33 The lattice constant is controlled by the size of the dendrimer (i.e., the generation number).

5. Cage Structures and Polyhedral Nanoparticles

Many viruses and also some proteins such as ferritins84 or carboxysomes85 (involved in carbon fixation by bacteria) naturally form pseudospherical polyhedral cage structures. Clathrin-coated vesicles also have a cage structure, built from triskelion (three-arm) subunits of the Clathrin heavy chain (with bound light chains).86 Clathrin can form tetrahedral mini-coat, hexagonal barrel or soccer ball structures in vitro.86 A discussion of these structures, and those of viruses, is outside the scope of the present review, although examples of virus-like protein nanoparticle assemblies and of virus-derived assemblies are considered.

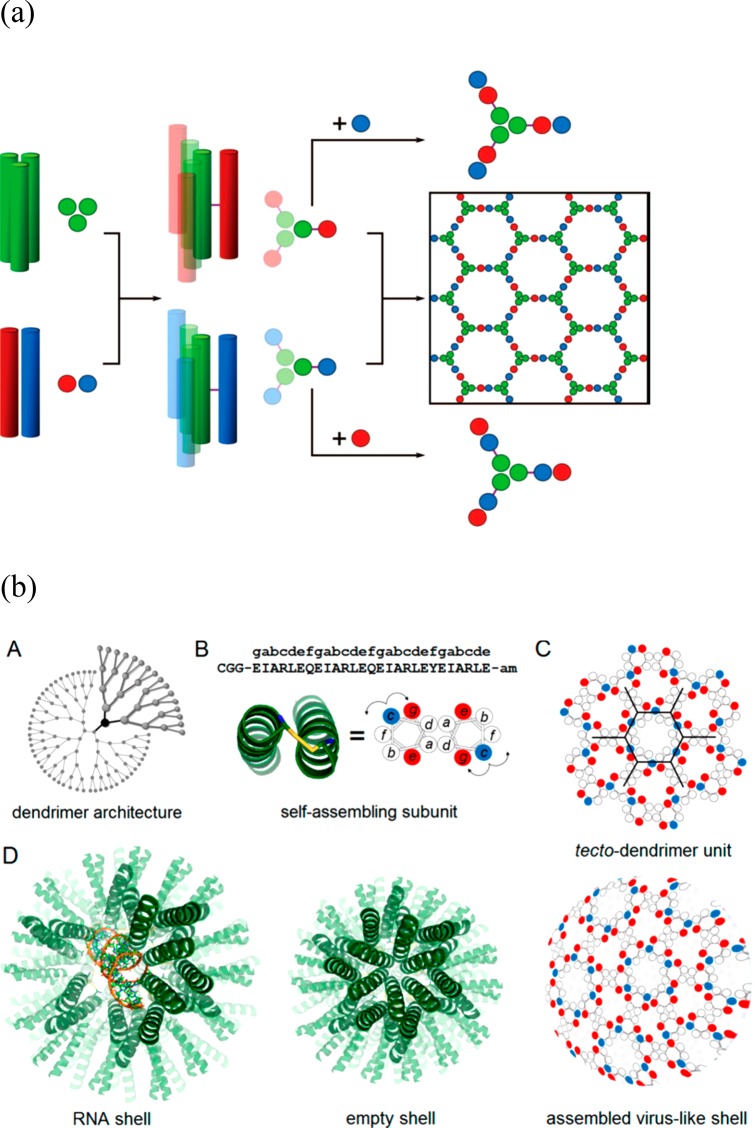

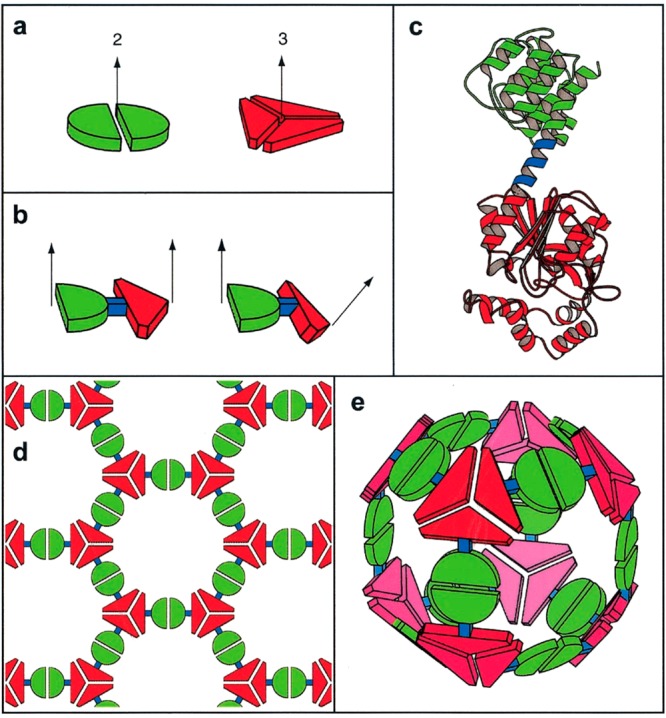

Controlling the association of coiled coil peptides by design has enabled the assembly of cage structures. Woolfson and co-workers designed a two-component system comprising a homotrimeric coiled coil linked to one of two heterodimeric coiled coils (containing complementary charged residues) through an external disulfide bond between cysteine residues (Figure 18a).87 The building blocks are expected to form a honeycomb lattice, however due to the inherent conformational flexibility, closed shell structures termed SAGES, self-assembled cage-like particles, were observed with a diameter of approximately 100 nm.87 Later, Ryadnov’s group developed cysteine-linked homodimeric coiled-coils with three different faces such that complementary electrostatic interactions between neighboring dimers would favor formation of a honeycomb lattice (Figure 18b) or so-called tecto-dendrimer unit.26 Again, curling up into virus-like cages was observed in practice, with a diameter of approximately 12–18 nm. The cage-like particles were able to transfect RNA and DNA. In related work, Castelletto et al. have prepared covalently linked “triskelion” three-arm peptides containing the self-complementary β-sheet sequence RRWTWE, based on a sequence from lactoferrin.13 These associate to give honeycomb lattices which curve into cage structures or capsules, able to encapsulate and deliver siRNA, and with additional antimicrobial activity. This was ascribed to membrane pore formation, as imaged by AFM using model supported lipid bilayers.13

Figure 18.

(a) Schematic for coiled coil peptide assembly designed to self-assemble into a honeycomb lattice (which is observed to curve into a cage structure).87 Left: a homotrimeric coiled coil is linked via cysteine disulfide cross-linking to a homodimeric coiled coil. Mixing of either the top building block (center, green and red) termed Hub A with coiled coil module B (basic coil peptide, blue) or Hub B (center bottom 3-arm structure, green and blue) and module A (acidic coil peptide, red) leads to the formation of a honeycomb lattice (right). (b) Design of a dendrimer-like coiled coil peptide which forms a cage structure.26 (A) Dendrimer architecture, (B) cysteine-linked (yellow connector) coiled coil dimer; red and blue circles indicate glutamate and arginine residues, respectively. (c) Expected honeycomb lattice, (D) model for RNA-filled capsule, empty shell and observed virus-like cage structure. Part a from ref (87). Reprinted with permission from AAAS. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/340/6132/595. Part b reproduced with permission from ref (26). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Attaching coiled-coil peptides to the free C-terminus of a trimeric aldolase protein (KDPG aldolase from Thermotoga maritima) enables the design of cage-like assemblies by mixing homologues with complementary heterodimer-forming coiled coils.88 After expression of the C-terminal extended aldolase in E. coli, TEM and AUC (analytical ultracentrifugation) confirmed the presence of small assemblies in solution, with typical diameters 10–20 nm.88,89 A dimer was reported to be the most common assembled structure, although some tetrahedral and octahedral cages were detected.89 This work was extended by using an esterase C3-symmetric trimer linked via flexible spacers to C-terminally attached helical peptides, designed to form tetrameric coiled coils.5 The fusion protein was expected to form octahedral cage structures. The experiments confirmed the formation of such structures, provided the length of the spacer was sufficient, via mass spectrometry, AUC and TEM imaging.

Yeates and co-workers have produced nanocage structures from fusion proteins, using the concept shown in Figure 19. The fusion protein comprised trimeric bromoperoxidase and the dimeric M1 matrix protein of influenza virus, connected by a nine-residue helical linker. The fusion protein was expected to have a tetrahedral shape, favoring the formation of dodecameric cage structures, which indeed were observed by TEM, after recombinant expression in E. coli and preparation of aqueous solutions.6 A crystal structure for the dodecameric cage structure was later obtained.90 The authors also reported a fusion protein that forms helical filaments based on the M1 protein fused to carboxylesterase linked by a 5-residue α-helical linker.6 In a similar fashion, fusion proteins designed to encode the information necessary to direct assembly have been used to produce 24-subunit cage structures, based on positioning of trimeric building blocks along each of the 3-fold symmetry axes of a tetrahedron.7 The protein structure and interaction modeling software Rosetta91 was then used to design the sequences at the interfaces of the building blocks, in order to enhance the stability of the interface through packing of suitable hydrophobic residues. In addition, structures were assembled from four trimeric and six dimeric building blocks aligned along the respective tetrahedral symmetry axes. After screening for solubility and compatibility with self-assembly, constructs were selected for experimental study. TEM images showed that the fusion proteins expressed in E. coli self-assembled into the designed structures in solution, and crystal structures were obtained for some of the assemblies.7

Figure 19.

Fusion protein design. (a) Proteins with different subunit symmetries (here 2-fold and 3-fold rotation symmetry).6 (b) Fusion of two proteins (showing two possible geometries). (c) A ribbon diagram showing an example of a fusion construct where red and green proteins are linked by a short α-helix (blue). The fusion requires one protein to have an initial α-helix domain, the other protein must have a terminal α-helix. (d) Schematic of a 2D honeycomb lattice that assembles from flat fusion dimers. (e) Schematic of a cage structure formed when the two proteins are twisted, as shown in part b, right. Reproduced from ref (6). Copyright 2001 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.

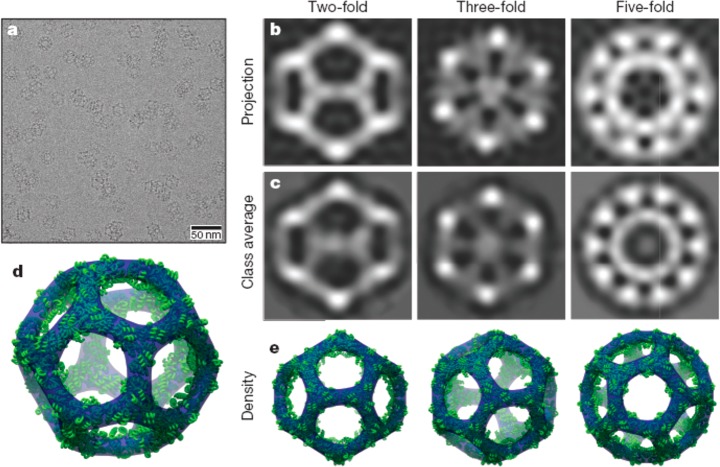

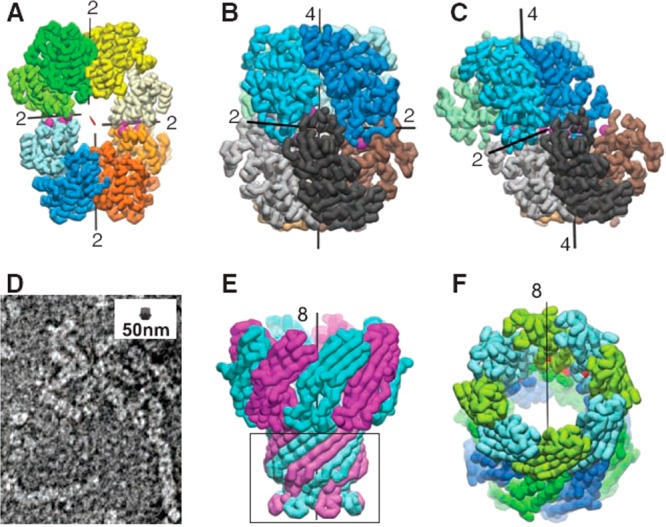

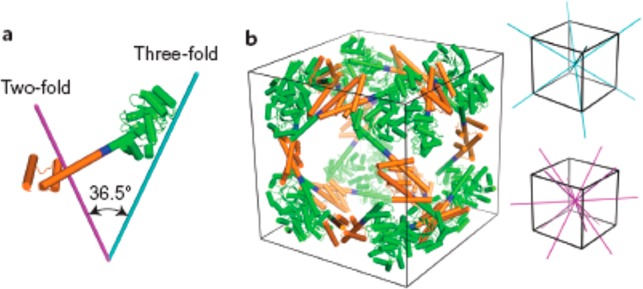

Developing this concept, icosahedral protein cages have been created by design of 60-subunit fusion proteins using trimeric protein scaffolds arranged with icosahedral symmetry (i.e., arranging the trimer 3-fold symmetry axis to be coincident with the 3-fold axes of the icosahedron).8 The distance from the icosahedron center and the rotation angle of each trimer about its axis were then optimized for close packing, minimizing steric clashes. The hydrophobic interfaces between the trimer building blocks were then filled by computer-assisted design of amino acid sequences. Figure 20 shows cryo-TEM images along with reconstructions from the model design, confirming the icosahedral cage structure.8 In an extension of this work, this group also presented 120-subunit icosahedral protein cages with sizes 24–40 nm in diameter based again on designed fusion proteins, but using heteromeric components.9 Combinations of distinct building blocks among dimers, trimers and pentamers (according to the icosahedral symmetry elements) were used, for example 12 pentameric and 20 trimeric building blocks aligned along the 5-fold and 3-fold icosahedral symmetry axes can produce an icosahedral protein cage, which can also be constructed from combinations of pentamers and dimers or trimers and dimers.9 In a parallel development of the helical oligomer fusion strategy, a cubic cage- forming structure was designed and expressed in E. coli.10 The intention was to create a porous material, resembling a MOF, although long-range cubic ordering was not observed. The fusion protein comprises trimeric KDPG aldolase (the same used by Patterson et al.88) linked via a four-residue helical linker to the dimeric domain of protein FkpA (Figure 21a). The designed 24-subunit cage structure with octahedral symmetry is shown in Figure 21b. Single crystal X-ray diffraction and TEM confirmed the presence of the cubic cage structures after incubation of solutions of the fusion protein, although 12-mers, 18-mers and 24-mers were also detected by mass spectrometry analysis, TEM and SAXS.10

Figure 20.

Icosahedral protein cages. (a) Low-magnification cryo-TEM image showing cages in different projections. (b) Back-projections of structure along different symmetry axes based on the model. (c) Class averages from cryo-TEM images (bottom). (d) Three-dimensional model of the icosahedral structure. (e) Projections corresponding to images in panels b and c. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (8). Copyright 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/.

Figure 21.

(a) Design of a fusion protein with appropriate oriented symmetry axes based on a trimeric protein (green) linked to a dimeric domain (orange) via a four-residue helical linker (blue). (b) Intended 24-subunit cubic cage structure with octahedral symmetry, the 3-fold symmetry axes (cyan) and 2-fold symmetry axes (magenta) of a cube being shown on the right. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, ref (10). Copyright 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited, https://www.nature.com/nchem/.

Ferritin, which is widely used to prepare protein lattices as discussed in the preceding section, is also a cage-like protein.92 Mutants have been engineered with Cys residues in metal-binding domains in order to sequester gold formed by reduction from Au3+ ions. A crystal structure of the cage with bound gold was obtained.92 Modification of ferritin nanocages by attachment of PEG facilitates penetration of the nanoparticles into tumor tissue and airway mucus.93,94 The PEG surface coating density was optimized by mixing highly PEGylated ferritin (attached via surface amines) with the native ferritin by disassembling the proteins and then reassembling using pH control. The anticancer drug doxorubicin was conjugated to PEGylated ferritin via an acid-labile linker as a therapeutic delivery vehicle.93

The size of protein cages can be tuned by modification of the surface charge, as exemplified by recent work on the capsid-forming enzyme AaLS which in its native form adopts an icosahedral shape (60 subunits).95,96 Directed evolution led to a supercharged luminal capsid surface, able to better encapsulate oppositely (positively charged) cargo, in particular HIV protease, with an expansion in cage size corresponding to 180 or 240 subunits.95 The structure of the expanded supercharged cages was investigated in detail using cryo-TEM and was found to comprise tetrahedrally- and icosahedrally- arranged pentameric units.96 By mixing negatively supercharged AaLS with cationically supercharged ferritin, nested cage structures are obtained.29 This is a good example in which tuning of electrostatic interactions on protein surfaces can be used to create new assemblies, in this so-called Matryoshka-type structures.

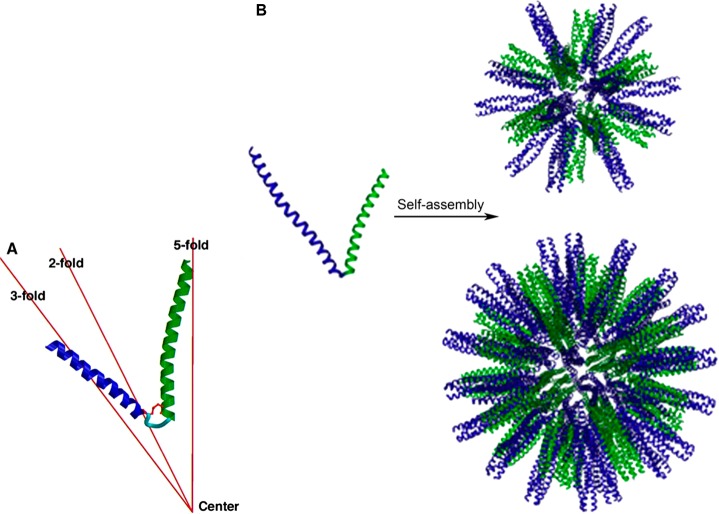

Self-assembling peptide nanoparticles (SAPNs) have been designed based on peptides that contain two α-helical domains linked by a two-glycine residue spacer, one of the oligomerization domains comprises a coiled coil that forms pentamers, while the other is from a trimeric coiled-coil domain (Figure 22a).97,98 The peptides are positioned to lie on the C5 and C3 symmetry axes respectively of an icosahedron or dodecahedron. The nanoparticles containing 60 or 180 peptides were modeled based on an icosahedral structure (Figure 22b).98 The former nanoparticle structure is favored for a de novo designed sequence containing cysteine residues (for which there is the potential for disulfide cross-linking)97 whereas the latter results from a modified construct with alanines replacing the cysteines and with extended terminal domains.98 The systems form roughly spherical nanoparticles with a diameter of 16 nm (for the 60 subunit protein)97 or 27 nm (for the 180 subunit protein).98 In an extension of this research, variant SAPNs were prepared and characterized by SANS, STEM (which enables molar mass estimation) and DLS.99 Based on the determined particle size (the core radius from SANS was 35–37 nm) and molar mass, it was proposed that these larger nanoparticles contain 240, 300, or 360 peptides, which were modeled as virus-like polyhedra.99

Figure 22.

Polyhedral peptide nanoparticles based on (a) building block comprising two linked coiled-coil peptides designed to form pentamers (green) or trimers (blue),97 with (b) models for their assembly into icosahedral particles. Top: Nanoparticle containing 60 peptides. Bottom: nanoparticle containing 180 peptides.98 Reprinted from refs (97, 98). Copyright 2006 and 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

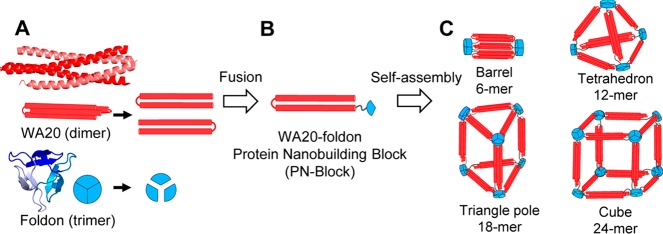

Fusion of a de novo designed protein that forms a dimeric folded four-helix bundle with a trimeric domain from T4 bacteriophage fibritin leads to oligomers comprising multiples of 6-mers, as shown in Figure 23.11 Fitting of SAXS data enabled the envelope shape of the aggregates in solution to be obtained, which indicated the presence of tetrahedral and barrel-shaped assemblies.11

Figure 23.

(a, b) Fusion protein from a designed four-helix dimer and a trimer from T4 phage fibritin. (c) Possible assemblies expected for the fusion protein, which are based on multiples of 6-mers. Reproduced with permission from ref (11). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

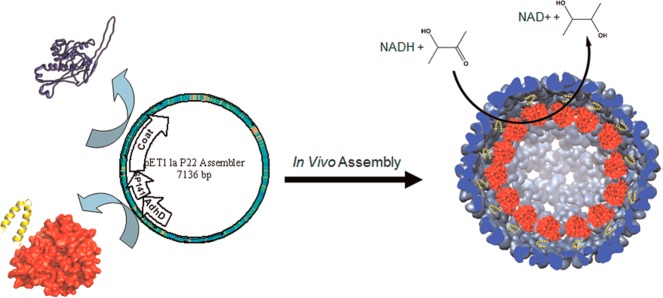

Virus-like particles (VLPs) have been modified to create nanoreactors, based on enzymes incorporated as fusion proteins with the scaffold proteins (SPs) which form the inner shell of viruses, which are surrounded with coat proteins (CPs). This is exemplified by the N-terminal conjugation of alcohol dehydrogenase (AdhD) to the SP of bacteriophage P22 (Figure 24).12 A P22 VLP is composed of approximately 420 copies of a 46.6 kDa coat protein (CP) that assembles into an icosahedral capsid with the aid of approximately 100–330 copies of a 33.6 kDa scaffolding protein (SP). In the AdhD-SP conjugate, the C-terminal α-helical scaffold protein facilitates coassembly with the P22 CP, leading to particles indistinguishable from those of native P22. The AdhD gene is inserted into the pET11 expression vector (Figure 24). The catalytic activity was maintained, furthermore since P22 undergoes structural transitions on heating which lead to expansion or pore formation, the accessibility of the tethered enzymes can be adjusted thermally.12 In a parallel study, encapsulation of thermostable CelB glycosidase inside the P22 capsid was demonstrated using the same concept, again with no loss of enzyme activity and without impairing the ability of the P22 to undergo thermally induced morphology changes.100 The packaging of fluorescent proteins on the interior surface of P22 VLPs was demonstrated in a similar fashion.101 The concept was later extended to incorporate multiple (2 or 3) fused enzymes, including CelB and dimeric ADP-dependent glucokinase and also monomeric AT-dependent galactokinase in the 3-enzyme construct.102 These enzymes can catalyze a cascade of coupled reactions, demonstrated with lactose as substrate. The activity of all encapsulated enzymes was confirmed, and the kinetic parameters were measured.

Figure 24.

Incorporation of alcohol dehydrogenase into the pET expression vector for bacteriophage P22 produces the AlhD-SP conjugate (red, with C-terminal truncated scaffold protein shown in yellow), and coassembly with the coat protein shown in blue leads to assembly of virus-like particles shown on the right, decorated with enzymes on the interior with model enzymatic activity shown (NAD: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide). Reproduced with permission from ref (12). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In summary, a variety of approaches have been successfully demonstrated to assemble proteins into defined aggregates including cages and 1D, 2D or 3D structures. Protein assembly can be induced by noncovalent interactions such as metal-ion mediated pairing or hydrophobic side-chain interface engineering or electrostatic interactions using modified proteins or by de novo design of proteins. Protein mutants can be created exploiting C- or N-terminal modifications or site-selective modifications, utilizing suitable residues such as cysteines located with respect to protein subunit symmetry axes. A range of natural multi- subunit proteins can be used for this purpose, there being a range of proteins with suitable C2, C3, C6, D2 and D4 subunit symmetries, among others, which can be used to produce 2D and 3D lattices, while an essential element of large cage structures is the inclusion of pentameric proteins in the design. It is possible to produce cage and 2D and 3D lattices with a remarkable degree of precision in the ordering using protein assemblies, provided appropriate design rules are followed.

It will be interesting to follow further research developments that lead to the design and creation of novel lattice structures (and possibly aperiodic quasicrystals). Perhaps inspiration can be taken from the field of DNA origami, utilizing stronger covalent interactions (such as multiple hydrogen bonds between nucleic acids) than have been exploited thus far. Other superstructures such as multiring (and interlinked) assemblies can be envisaged in analogy with the field of rotaxanes, with the related challenge to construct novel protein motors, inspired or distinct from natural ones.

Coiled coil proteins/peptides are an attractive design unit for simple de novo designed assemblies including polyhedral particles, ring structures, planar lattices and linear assemblies although coiled coils are combined with other elements to create cage and 3D lattice structures. On the other hand, assemblies based on natural proteins such as enzymes can enable the potential exploitation of the native function, for example biocatalysis. Native and mutant proteins can be produced recombinantly (commonly using E. coli expression vectors), leading to the potential to scale up the synthesis.

An alternative method to produce functional protein-based materials is to use protein assemblies as templates or scaffolds, as exemplified by the modification of polyhedral or rod-like virus capsids with desired function by engineering of the coat or scaffold proteins. Another example is the use of bacterial S-layers to produce two-dimensional protein arrays, modified to enable metal templating or to create planar catalysts by positioning enzymes. Materials with remarkable catalytic and optoelectronic properties have been engineered in this way. These may have a role in addressing important challenges, for example in photocatalytic water oxidation or in CO2 fixation, as discussed above, and related applications in clean energy generation can be envisaged, by choice of appropriate enzymes. Since enzyme cascades have important roles in vivo, their engineering using protein assemblies is also an exciting avenue for future developments.

As well as applications in biocatalysis, protein assemblies have potential in the creation of novel porous materials for separation and cage-like structures can be used to encapsulate and deliver cargo such as drug molecules, in a targeted manner (exploiting or modifying the protein coating to target particular cell functionalities). Alternatively, the intrinsic properties of such particles could be used to induce immunogenicity, with the potential additional benefits arising from self-adjuvant properties. Another class of therapeutic approaches may involve the modification of the assembly pathway of protein superstructures such as microtubules, which is the basis of Taxol’s anticancer activity. There are many related examples of protein structures (e.g., extracellular protein assemblies, ion pumps etc.) involved in disease progression which have not yet been targeted.

As yet, there are few examples of dynamic engineered protein assemblies, although in one recent example it has been demonstrated that a transition in 2D lattice structure of RhuA variant crystals (discussed in detail in Section 4) can be achieved by vigorous mixing and sedimentation (or by reversible Ca2+-induced switching).77 There is considerable scope to produce new responsive materials by incorporating biological motor protein elements (myosins, dyneins, ATPase etc.). This is an area with great potential to produce innovative active biomaterials.

Considering the impressive examples outlined in this Review, it should be clear that protein materials are very promising components of next-generation structural and functional biomaterials based on the unprecedented diversity of structures and properties that have evolved in natural proteins or can be designed into de novo constructs.

The author declares no competing financial interest.

References

- Usui K.; Maki T.; Ito F.; Suenaga A.; Kidoaki S.; Itoh M.; Taiji M.; Matsuda T.; Hayashizaki Y.; Suzuki H. Nanoscale elongating control of the self-assembled protein filament with the cysteine-introduced building blocks. Protein Sci. 2009, 18 (5), 960–969. 10.1002/pro.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T.-F.; So C.; White B. R.; Carlson J. C. T.; Sarikaya M.; Wagner C. R. Enzyme nanorings. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 2519–2525. 10.1021/nn800577h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll D.; Huber C.; Schlegel B.; Pum D.; Sleytr U. B.; Sara M. S-layer-streptavidin fusion proteins as template for nanopatterned molecular arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (23), 14646–14651. 10.1073/pnas.232299399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J. C.; Davies K. M.; Venien-Bryan C.; Noble M. E. M. Generation of protein lattices by fusing proteins with matching rotational symmetry. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6 (9), 558–562. 10.1038/nnano.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciore A.; Su M.; Koldewey P.; Eschweiler J. D.; Diffley K. A.; Linhares B. M.; Ruotolo B. T.; Bardwell J. C. A.; Skiniotis G.; Marsh E. N. G. Flexible, symmetry-directed approach to assembling protein cages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (31), 8681–8686. 10.1073/pnas.1606013113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla J. E.; Colovos C.; Yeates T. O. Nanohedra: Using symmetry to design self assembling protein cages, layers, crystals, and filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98 (5), 2217–2221. 10.1073/pnas.041614998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N. P.; Bale J. B.; Sheffler W.; McNamara D. E.; Gonen S.; Gonen T.; Yeates T. O.; Baker D. Accurate design of co-assembling multi-component protein nanomaterials. Nature 2014, 510 (7503), 103–108. 10.1038/nature13404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia Y.; Bale J. B.; Gonen S.; Shi D.; Sheffler W.; Fong K. K.; Nattermann U.; Xu C. F.; Huang P. S.; Ravichandran R.; Yi S.; Davis T. N.; Gonen T.; King N. P.; Baker D. Design of a hyperstable 60-subunit protein icosahedron. Nature 2016, 535 (7610), 136–139. 10.1038/nature18010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale J. B.; Gonen S.; Liu Y. X.; Sheffler W.; Ellis D.; Thomas C.; Cascio D.; Yeates T. O.; Gonen T.; King N. P.; Baker D. Accurate design of megadalton-scale two-component icosahedral protein complexes. Science 2016, 353 (6297), 389–394. 10.1126/science.aaf8818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. T.; Reading E.; Hura G. L.; Tsai K. L.; Laganowsky A.; Asturias F. J.; Tainer J. A.; Robinson C. V.; Yeates T. O. Structure of a designed protein cage that self-assembles into a highly porous cube. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6 (12), 1065–1071. 10.1038/nchem.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N.; Yanase K.; Sato T.; Unzai S.; Hecht M. H.; Arai R. Self-Assembling Nano-Architectures Created from a Protein Nano-Building Block Using an Intermolecularly Folded Dimeric de Novo Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (35), 11285–11293. 10.1021/jacs.5b03593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D. P.; Prevelige P. E.; Douglas T. Nanoreactors by Programmed Enzyme Encapsulation Inside the Capsid of the Bacteriophage P22. ACS Nano 2012, 6 (6), 5000–5009. 10.1021/nn300545z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelletto V.; de Santis E.; Alkassem H.; Lamarre B.; Noble J. E.; Ray S.; Bella A.; Burns J. R.; Hoogenboom B. W.; Ryadnov M. G. Structurally plastic peptide capsules for synthetic antimicrobial viruses. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (3), 1707–1711. 10.1039/C5SC03260A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle A. L.; Bromley E. H. C.; Bartlett G. J.; Sessions R. B.; Sharp T. H.; Williams C. L.; Curmi P. M. G.; Forde N. R.; Linke H.; Woolfson D. N. Squaring the Circle in Peptide Assembly: From Fibers to Discrete Nanostructures by de Novo Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (37), 15457–15467. 10.1021/ja3053943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G.; Zhang X.; Kochovski Z.; Zhang Y. F.; Dai B.; Sakai F. J.; Jiang L.; Lu Y.; Ballauff M.; Li X. M.; Liu C.; Chen G. S.; Jiang M. Precise and Reversible Protein-Microtubule-Like Structure with Helicity Driven by Dual Supramolecular Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (6), 1932–1937. 10.1021/jacs.5b11733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G.; Ding H. M.; Kochovski Z.; Hu R. T.; Lu Y.; Ma Y. Q.; Chen G. S.; Jiang M. Highly Ordered Self-Assembly of Native Proteins into 1D, 2D, and 3D Structures Modulated by the Tether Length of Assembly-Inducing Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (36), 10691–10695. 10.1002/anie.201703052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai F.; Yang G.; Weiss M. S.; Liu Y. J.; Chen G. S.; Jiang M. Protein crystalline frameworks with controllable interpenetration directed by dual supramolecular interactions. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 8. 10.1038/ncomms5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K.; Zang J.; Chen H.; Wang W.; Wang H.; Zhao G. On-axis alignment of protein nanocage assemblies from 2D to 3D through the aromatic stacking interactions of amino acid residues. ACS Nano 2018, 12 (11), 11323–11332. 10.1021/acsnano.8b06091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin J. D.; Ambroggio X. I.; Tang C. Y.; Parent K. N.; Baker T. S.; Tezcan F. A. Metal-directed, chemically tunable assembly of one-, two- and three-dimensional crystalline protein arrays. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4 (5), 375–382. 10.1038/nchem.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Cardone G.; Restrepo D.; Zavattieri P. D.; Baker T. S.; Tezcan F. A. Self-assembly of coherently dynamic, auxetic, two-dimensional protein crystals. Nature 2016, 533 (7603), 369. 10.1038/nature17633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontz P. A.; Bailey J. B.; Ahn S.; Tezcan F. A. A Metal Organic Framework with Spherical Protein Nodes: Rational Chemical Design of 3D Protein Crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (36), 11598–11601. 10.1021/jacs.5b07463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. B.; Zhang L.; Chiong J. A.; Ahn S.; Tezcan F. A. Synthetic Modularity of Protein-Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (24), 8160–8166. 10.1021/jacs.7b01202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C.; Li J.; Zhao L.; Zhang W.; Luo Q.; Dong Z.; Xu J.; Liu j. Construction of protein nanowires through cucurbit[8]uril-based highly specific host-guest interactions: An approach to the assembly of functional proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5590–5593. 10.1002/anie.201300692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanci C. J.; MacDermaid C. M.; Kang S. G.; Acharya R.; North B.; Yang X.; Qiu X. J.; DeGrado W. F.; Saven J. G. Computational design of a protein crystal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109 (19), 7304–7309. 10.1073/pnas.1112595109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R.; Chen L.; Yang S.; Lv C.; Leng X.; Zhao G. 2D square arrays of protein nanocages through channel-directed electrostatic interactions with poly(α, L-lysine). Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (22), 2879–2882. 10.1039/c3cc49306g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble J. E.; De Santis E.; Ravi J.; Lamarre B.; Castelletto V.; Mantell J.; Ray S.; Ryadnov M. G. A De Novo Virus-Like Topology for Synthetic Virions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (37), 12202–12210. 10.1021/jacs.6b05751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzle M.; Eckert T.; Beck T. Binary Protein Crystals for the Assembly of Inorganic Nanoparticle Superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (39), 12731–12734. 10.1021/jacs.6b07260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy K.; Uchida M.; Lee B.; Douglas T. Templated Assembly of a Functional Ordered Protein Macromolecular Framework from P22 Virus-like Particles. ACS Nano 2018, 12 (4), 3541–3550. 10.1021/acsnano.8b00528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T.; Tetter S.; Künzle M.; Hilvert D. Construction of Matryoshka-Type Structures from Supercharged Protein Nanocages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (3), 937–940. 10.1002/anie.201408677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A. J.; Zhou Y.; Ramasubramani V.; Glaser J.; Pothukuchy A.; Gollihar J.; Gerberich J. C.; Leggere J. C.; Morrow B. R.; Jung C.; Glotzer S. C.; Taylor D. W.; Ellington A. D. Supercharging enables organized assembly of synthetic biomolecules. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11 (3), 204–212. 10.1038/s41557-018-0196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostiainen M. A.; Hiekkataipale P.; Laiho A.; Lemieux V.; Seitsonen J.; Ruokolainen J.; Ceci P. Electrostatic assembly of binary nanoparticle superlattices using protein cages. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8 (1), 52–56. 10.1038/nnano.2012.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljestrom V.; Mikkila J.; Kostiainen M. A. Self-assembly and modular functionalization of three-dimensional crystals from oppositely charged proteins. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 9. 10.1038/ncomms5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljestrom V.; Seitsonen J.; Kostiainen M. A. Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Soft Matter Nanoparticle Cocrystals with Tunable Lattice Parameters. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (11), 11278–11285. 10.1021/acsnano.5b04912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljestrom V.; Ora A.; Hassinen J.; Rekola H. T.; Nonappa; Heilala M.; Hynninen V.; Joensuu J. J.; Ras R. H. A.; Torma P.; Ikkala O.; Kostiainen M. A. Cooperative colloidal self-assembly of metal-protein superlattice wires. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 10. 10.1038/s41467-017-00697-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papapostolou D.; Howorka S. Engineering and exploiting protein assemblies in synthetic biology. Mol. BioSyst. 2009, 5 (7), 723–732. 10.1039/b902440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howorka S. Rationally engineering natural protein assemblies in nanobiotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22 (4), 485–491. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. T.; King N. P.; Yeates T. O. Principles for designing ordered protein assemblies. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22 (12), 653–661. 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciore A.; Marsh E. N. G.. Symmetry-directed design of protein cages and protein lattices and their applications. In Macromolecular Protein Complexes, Harris J. R., Marles-Wright J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp 195–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q.; Hou C. X.; Bai Y. S.; Wang R. B.; Liu J. Q. Protein Assembly: Versatile Approaches to Construct Highly Ordered Nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (22), 13571–13632. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan S. L.; Bergamini F. R. G.; Weil T. Functional protein nanostructures: a chemical toolbox. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47 (24), 9069–9105. 10.1039/C8CS00590G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumiller W. M.; Uchida M.; Douglas T. Protein cage assembly across multiple length scales. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47 (10), 3433–3469. 10.1039/C7CS00818J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rica R.; Matsui H. Applications of peptide and protein-based materials in bionanotechnology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39 (9), 3499–3509. 10.1039/b917574c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. C. T.; Jena S. S.; Flenniken M.; Chou T. F.; Siegel R. A.; Wagner C. R. Chemically controlled self-assembly of protein nanorings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (23), 7630–7638. 10.1021/ja060631e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamley I. W. Peptide fibrillisation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8128–8147. 10.1002/anie.200700861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A. M. Neuroprotective therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease: progress and prospects. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32 (3), 141–147. 10.1016/j.tips.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida T.; Meijer E. W.; Stupp S. I. Functional Supramolecular Polymers. Science 2012, 335 (6070), 813–817. 10.1126/science.1205962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G.; Su Z. Q.; Reynolds N. P.; Arosio P.; Hamley I. W.; Gazit E.; Mezzenga R. Self-assembling peptide and protein amyloids: from structure to tailored function in nanotechnology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46 (15), 4661–4708. 10.1039/C6CS00542J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y. S.; Magyar A. P.; Lee D.; Kim J. W.; Yun D. S.; Park H.; Pollom T. S.; Weitz D. A.; Belcher A. M. Biologically templated photocatalytic nanostructures for sustained light-driven water oxidation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5 (5), 340–344. 10.1038/nnano.2010.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. T.; Kim D. W.; Yoo P. J.; Chiang C. Y.; Meethong N.; Hammond P. T.; Chiang Y. M.; Belcher A. M. Virus-enabled synthesis and assembly of nanowires for lithium ion battery electrodes. Science 2006, 312 (5775), 885–888. 10.1126/science.1122716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J.; Yi H.; Kim W. J.; Kang K.; Yun D. S.; Strano M. S.; Ceder G.; Belcher A. M. Fabricating Genetically Engineered High-Power Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Multiple Virus Genes. Science 2009, 324 (5930), 1051–1055. 10.1126/science.1171541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K.; Yun D. S.; Belcher A. M. Cobalt ion mediated self-assembly of genetically engineered bacteriophage for biomimetic Co-Pt hybrid material. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7 (1), 14–17. 10.1021/bm050691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura J. F.; Burpo F. J.; Lescott C. J.; Ransil A.; Yoon Y.; Records W. C.; Belcher A. M. Highly adjustable 3D nano- architectures and chemistries via assembled 1D biological templates. Nanoscale 2019, 11 (3), 1091–1102. 10.1039/C8NR04864A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. T.; Peelle B. R.; Lee S. W.; Belcher A. M. Genetically driven assembly of nanorings based on the M13 virus. Nano Lett. 2004, 4 (1), 23–27. 10.1021/nl0347536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn C. E.; Lee S. W.; Peelle B. R.; Belcher A. M. Viruses as vehicles for growth, organization and assembly of materials. Acta Mater. 2003, 51 (19), 5867–5880. 10.1016/j.actamat.2003.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Matsui H. Peptide-based nanotubes and their applications in bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 2037–2050. 10.1002/adma.200401849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. J.; Zheng J.; Zanuy D.; Haspel N.; Wolfson H.; Aleman C.; Nussinov R. Principles of nanostructure design with protein building blocks. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 2007, 68 (1), 1–12. 10.1002/prot.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon S.; Aggeli A. Self-assembling peptide nanotubes. Nano Today 2008, 3 (3–4), 22–30. 10.1016/S1748-0132(08)70041-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valéry C.; Artzner F.; Paternostre M. Peptide nanotubes: molecular organisations, self-assembly mechanisms and applications. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9583–9594. 10.1039/c1sm05698k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamley I. W. Peptide Nanotubes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (27), 6866–6881. 10.1002/anie.201310006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Abramovich L.; Gazit E. The physical properties of supramolecular peptide assemblies: from building block association to technological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (20), 6881–6893. 10.1039/C4CS00164H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff P. B.; Fant J.; Horwitz S. B. Promotion of Microtubule Assembly Invitro by Taxol. Nature 1979, 277 (5698), 665–667. 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M. A.; Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4 (4), 253–265. 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. L.; Lindbo J. A.; Dillard-Telm S.; Brosio P. M.; Lasnik A. B.; McCormick A. A.; Nguyen L. V.; Palmer K. E. Modified Tobacco mosaic virus particles as scaffolds for display of protein antigens for vaccine applications. Virology 2006, 348 (2), 475–488. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. A.; Presley A. D.; Francis M. B. Self-assembling light-harvesting systems from synthetically modified tobacco mosaic virus coat proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (11), 3104–3109. 10.1021/ja063887t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]