Design a protein-based contrast agent for detecting liver metastases with magnetic resonance imaging.

Abstract

Liver metastases often progress from primary cancers including uveal melanoma (UM), breast, and colon cancer. Molecular biomarker imaging is a new non-invasive approach for detecting early stage tumors. Here, we report the elevated expression of chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) in liver metastases in UM patients and metastatic UM mouse models, and development of a CXCR4-targeted MRI contrast agent, ProCA32.CXCR4, for sensitive MRI detection of UM liver metastases. ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibits high relaxivities (r1 = 30.9 mM−1 s−1, r2 = 43.2 mM−1 s−1, 1.5 T; r1 = 23.5 mM−1 s−1, r2 = 98.6 mM−1 s−1, 7.0 T), strong CXCR4 binding (Kd = 1.10 ± 0.18 μM), CXCR4 molecular imaging capability in metastatic and intrahepatic xenotransplantation UM mouse models. ProCA32.CXCR4 enables detecting UM liver metastases as small as 0.1 mm3. Further development of the CXCR4-targeted imaging agent should have strong translation potential for early detection, surveillance, and treatment stratification of liver metastases patients.

INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults. Approximately 50% of UM patients will develop metastases (1). About 93% of UM metastases occur in the liver, which results in death in almost all cases due to the lack of effective treatments (2). Through histological analysis of postmortem patient samples, UM liver metastases can be classified into three stages based on size (i.e., diameter): stage 1 (≤50 μm in diameter), stage 2 (51 to 500 μm in diameter), or stage 3 (>500 μm in diameter) (3). Pathologically, UM hepatic metastases primarily have two growth patterns: infiltrative or nodular. The infiltrative pattern occurs when circulating metastatic UM cells lodge in the sinusoidal space and eventually replace the hepatic lobule. The nodular pattern metastases, however, originate in the periportal area. UM cells co-opt the portal vein, and when the tumor grows, it exhibits angiogenesis and effaces the adjacent hepatocytes (4).

There are major barriers facing clinicians in UM management, such as the lack of noninvasive and sensitive imaging methods for metastases, and the resistance of UM to traditional systemic chemotherapies (5, 6). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is a widely used modality for screening of hepatic metastases (7); however, this method is not optimal for liver lesion characterization (8). 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (18FDG) positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) not only can locate the “hotspot” for characterization of liver metastases but also has disadvantages due to the use of radiation dosimetry and the comparatively low specificity of the technology (9).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred clinical imaging modality for the assessment and characterization of liver malignancy because it does not use ionizing radiation and has high soft tissue penetration providing morphological, anatomical, and functional information. Dynamic-enhanced MRI, with liver-specific contrast agents, is widely used for liver lesion characterization, although its sensitivity and specificity are low for lesions less than 1 cm (10). In addition, MRI with the administration of clinically approved contrast agents can not differentiate the different growth patterns of UM metastases in the liver (11). Previous studies have demonstrated that molecular imaging of corresponding biomarker expression, such as HER2, improves detection sensitivity for cancers (12), but to date, diagnostic biomarkers for imaging UM liver metastases have not yet been established. Therefore, there is a pressing unmet medical need to develop MRI contrast agents for early detection and follow-up of liver metastases, especially for high-risk patients.

CXCR4 (chemokine receptor 4) plays a key role in cell migration and metastatic dissemination to several organs such as the liver, bone marrow, and lung, as these organs have intrinsically high concentrations of its natural ligand CXCL12 (Fig. 1A) (13–15). A CXCR4 antagonist, plerixafor (Mozobil, AMD3100), has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for stem cell mobilization to the peripheral blood for autologous transplantation (16). CXCR4 expression has been proposed as a prognostic factor and a potential therapeutic target. Elevated expression of CXCR4 has been reported in several UM cell line studies (17, 18). Blockage of CXCR4 gene expression by transfection with CXCR4 small interfering RNA (siRNA) has been found to inhibit invasive properties of UM cells exposed to soluble factors produced by human livers (14). On the basis of these data, we hypothesized that CXCR4 would be a potential biomarker with treatment implications for imaging UM metastases in the liver.

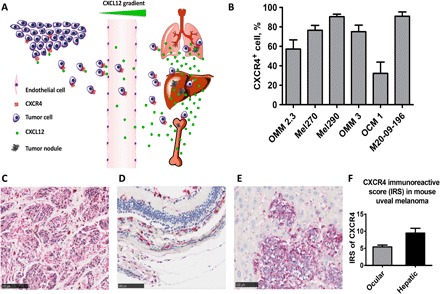

Fig. 1. CXCR4 expression is up-regulated in UM cell lines, hepatic metastases in UM patients, and metastatic UM mice.

(A) Tumor cells that express CXCR4 metastasize through CXCR4-CXCL12 interaction to specific organs that have intrinsically high concentrations of CXCL12 such as the lung, liver, and bone. (B) UM cell lines have elevated CXCR4 expression. Flow cytometry results measured elevated CXCR4 expression across different UM cell lines. Mel290 and M20-09-196 measured more than 80% of CXCR4 immunopositivity. Measurements of each cell line were done in triplicate. (C) CXCR4 IHC staining in liver tissue from metastatic UM patients (n = 4, IRS = 8.2 ± 1.3). The liver metastases displayed strong red intensity, denoting strong CXCR4 expression. (D and E) CXCR4 IHC staining of primary UM (D) and hepatic metastases (E) in metastatic UM mice. UM hepatic metastases have higher CXCR4 expression compared with primary UM, indicated by the red staining. (F) CXCR4 IRS of primary UM and metastases in the liver in metastatic UM mice. Hepatic UM metastases displayed stronger CXCR4 expression (IRS = 9.5 ± 0.8) than primary UM (IRS = 5.4 ± 0.3). P ≤ 0.05.

In this study, we confirmed and validated that CXCR4 is a diagnostic imaging biomarker by its elevated expression in liver metastases in three different systems: ex vivo using samples of UM patients, in vitro UM cell lines, and in vivo mouse models. In addition, we have successfully designed a CXCR4-targeted, protein-based contrast agent, ProCA32.CXCR4, which can detect UM hepatic metastases as small as 0.1 mm3. The detected liver micrometastases were further validated by histological analysis, which correlated with MRI results. Our results indicated that ProCA32.CXCR4 enables precision MRI capable of defining molecular signatures for identifying metastases.

RESULTS

CXCR4 is highly expressed in UM liver metastases

To validate CXCR4 as a biomarker for imaging UM metastases, we determined CXCR4 expression in multiple systems, including six UM cell lines, UM patient–derived tissue, as well as a metastatic UM mouse model. Flow cytometry analyses of six UM cell lines revealed that CXCR4 is expressed across different UM cell lines. Among these, Mel290 and M20-09-196 cell lines exhibited more than 80% CXCR4 immunopositivity (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of CXCR4 in UM patient liver tissue revealed that CXCR4 is highly expressed in liver metastases with both nodular and infiltrative growth patterns (Fig. 1C). We further observed elevated CXCR4 expression in primary ocular tumor and liver metastases in the metastatic UM mouse model generated by inoculation of M20-09-196 cells (Fig. 1, D and E), which have the BAP1 gene mutation that is often observed in aggressive UM liver metastases (19). In these M20-09-196 mice, the CXCR4 immunoreactive score (IRS) of UM metastases in the liver was significantly higher than in primary UM (P < 0.05, Fig. 1F). Together, these data indicated that CXCR4 expression is increased in UM metastases in the liver and may be a potential biomarker for diagnostic imaging of UM metastases.

Design of the CXCR4-targeted protein contrast agent ProCA32.CXCR4 and in vitro validation of CXCR4 binding

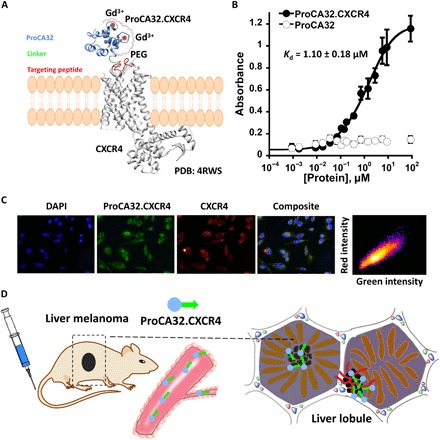

Figure 2A presents the design of ProCA32.CXCR4 and the interaction of ProCA32.CXCR4 with CXCR4. ProCA32.CXCR4 was generated by engineering a CXCR4-targeting moiety into a protein contrast agent, ProCA32, which incorporates two designed gadolinium (Gd3+) binding sites (20). The viral chemokine analog viral macrophage inflammatory protein-II (vMIP-II) is encoded by the human herpes virus 8 and interacts with CXCR4. On the basis of the complex x-ray structure of CXCR4 and vMIP-II, we designed the CXCR4 targeting moiety, including key CXCR4 interaction residues from vMIP-II that reach into the binding pocket and interact with key residues D262, D97, S285, and E288 of CXCR4 in both chemokine recognition sites 1 and 2 (21). ProCA32.CXCR4 was bacterially expressed and purified following our previously reported protocol (20). ProCA32.CXCR4 is also composed of lysine or cysteine residues, which allow post-expression PEGylation (22). PEGylation was verified by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and iodine staining (fig. S1). The CXCR4-targeting capability of ProCA32.CXCR4 was verified and quantified by immunofluorescence staining and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We determined the dissociation constant (Kd) of ProCA32.CXCR4-CXCR4 interaction using indirect ELISA (Fig. 2B). Nontargeted ProCA32 was used as a negative control. The binding curve indicated a 1:1 binding stoichiometry, and the determined Kd value was 1.10 ± 0.18 μM. The CXCR4 receptor number per Mel290 cell was 1.2 ± 0.1 × 106. Immunofluorescence staining of ProCA32.CXCR4 after incubating with the CXCR4-expressing cell line Mel290 confirmed that ProCA32.CXCR4 binds to CXCR4 with a high spatial correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.82) (Fig. 2C). We hypothesized that intravenous tail injection of ProCA32.CXCR4 would bind to tumors with elevated expression of CXCR4 and enhance the intensity of the corresponding areas in MRI, as demonstrated in Fig. 2D.

Fig. 2. ProCA32.CXCR4 binds to CXCR4.

(A) Model structure of ProCA32.CXCR4 interacting with CXCR4 [Protein Data Bank (PDB): 4RWS] through targeting moiety. ProCA32.CXCR4 was constructed by engineering the CXCR4 targeting moiety (red) to ProCA32 (blue) by a flexible linker (green). The targeting moiety of ProCA32.CXCR4 binds to CXCR4 through residue-residue and electrostatic interactions. ProCA32.CXCR4 has two Gd3+ (red circle) binding sites. (B) CXCR4 targeting study of ProCA32.CXCR4 by ELISA. The dissociation constant of ProCA32.CXCR4 binding to CXCR4 was calculated as 1.10 ± 0.18 μM, measured by indirect ELISA. n = 3. The nontargeted contrast agent ProCA32 did not exhibit CXCR4 targeting capability. (C) Fluorescence staining of Mel290 cells to study the CXCR4 binding effect of ProCA32.CXCR4. Blue fluorescence is nucleus staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), green color is fluorescein-labeled ProCA32.CXCR4, red color indicates CXCR4 staining, and composite is the combination of nucleus, CXCR4, and ProCA32.CXCR4 staining. ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited good spatial colocalization with CXCR4; Pearson’s r is 0.82. (D) Working flow of ProCA32.CXCR4. ProCA32.CXCR4 was administered through tail vein injection and distributed with blood flow, and specific targeting to CXCR4 high expression metastatic UM (indicated by black cells) was shown over time.

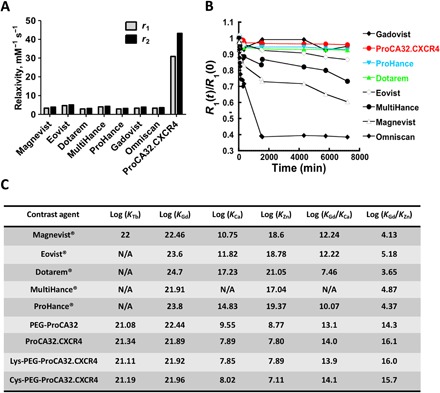

Improved r1 and r2 relaxivities of ProCA32.CXCR4

The r1 and r2 values per Gd3+ for ProCA32.CXCR4 were 30.9 mM−1 s−1 and 43.2 mM−1 s−1, respectively, at 1.5 T (Fig. 3A and fig. S2A, relaxivity reported on the basis of “per Gd3+” value). Both r1 and r2 relaxivity values were 8 to 10 times greater than the clinically approved Gd3+-based contrast agents (GBCAs) (Fig. 3A and table S1). ProCA32.CXCR4 also exhibited good relaxivities at higher magnetic field of 7.0 T (fig. S2B). The r1 and r2 relaxivity values of non-PEGylated ProCA32.CXCR4 were 23.5 and 98.6 mM−1 s−1, respectively. The relaxivities of the non-PEGylated form of ProCA32.CXCR4, lysine-PEGylated ProCA32.CXCR4 (Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4), and cysteine-PEGylated ProCA32.CXCR4 (Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4) did not exhibit significant differences. The r1 and r2 relaxivities of ProCA32.CXCR4 were largely retained after PEGylation. Overall, ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited improved r1 and r2 relaxivities when compared with clinical GBCA at both 1.5 and 7.0 T.

Fig. 3. Relaxivity (reported as “per Gd” value), transmetalation, and metal selectivity studies of ProCA32.CXCR4.

(A) Relaxivity assessment of ProCA32.CXCR4 and GBCA with 60-MHz relaxometer; ProCA32.CXCR4 has 8 to 10 times higher r1 and r2 values than clinical GBCA. (B) Transmetalation study of ProCA32.CXCR4 and other GBCA in the presence of Zn2+. Thermodynamic index of ProCA32.CXCR4 incubated at 37°C with Zn2+ was 0.96, which is better than ProHance (0.93) and Gadovist (0.95). (C) Metal (Zn2+, Ca2+, Gd3+, and Tb3+) binding affinity and metal selectivity values of ProCA32.CXCR4 in comparison with clinical contrast agents. N/A, not available; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

ProCA32.CXCR4 has uniquely high metal selectivity against transmetalation and metal toxicity

Gd3+-related toxicity, such as the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with chronic kidney disease and brain deposition of GBCA, is largely attributed to the kinetic and thermodynamic stability of GBCA (23). ProCA32.CXCR4 is stable up to 14 days when incubated with serum at 37°C (fig. S3A). The transmetalation study (Fig. 3B) indicated that the ProCA32.CXCR4 complex with Gd3+ has the highest stability in the presence of Zn2+, with a higher thermodynamic index [R1(t) = 4320 min/R0(t) = 0 min] of 0.96, greater than Gadovist (0.95), ProHance (0.93), and Dotarem (0.93) (fig. S3B). Other linear reagents such as Magnevist (gadopentetate) and Eovist (gadoxetate) cannot protect Gd3+ against transmetalation by Zn2+, and relaxivity measurements of those contrast agents were significantly reduced when incubated in the presence of Zn2+ (Fig. 3B and fig. S3B). Using our developed chelator-buffer system method (20), we determined the Gd3+ binding affinity of ProCA32.CXCR4 by competing with preloaded terbium (Tb3+) (fig. S4, A and B). ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited superior metal selectivity for Gd3+ over Zn2+ [log (KGd/KZn) =16.1] (Fig. 3C and fig. S4C), which was 1011 to 1012 orders of magnitude higher than small chelator contrast agents. For other physiological metal ions such as Ca2+, ProCA32.CXCR4 also exhibited better metal selectivity than small chelator GBCAs, such as Dotarem (gadoterate meglumine) and ProHance (gadoteridol) (Fig. 3C and fig. S4D).

ProCA32.CXCR4 enables early detection of stage 2 nodular growth pattern UM metastases in the liver

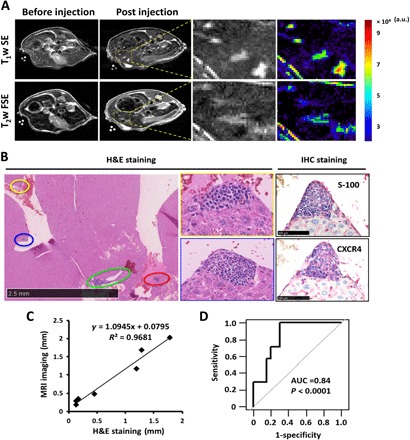

We demonstrated the unique imaging capability of ProCA32.CXCR4 for detection of liver metastases, improving the current detection limit and enabling nodular pattern detection in metastatic M20-09-196 mice at 7.0 T. The early detection of UM metastases in the liver of M20-09-196 mice can be achieved using either Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 or Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4. Liver micrometastases ranging from 0.01 to 0.08 mm3 were detected with spin echo acquisition and fast spin echo acquisition following tail vein injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (0.025 mmol/kg) (Fig. 4A). Enhancement of UM metastases was not detected by MRI following administration of Eovist or Lys-ProCA32 without the targeting moiety (fig. S5A). These results demonstrate the sensitivity and specificity of our system. These small liver lesions, detected by MRI with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, were further verified by detailed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining analysis and found to be exclusively nodular growth pattern type (labeled by the yellow, blue, green, and red circles) (Fig. 4B). The interlesion distances and diameters of lesions on MRI correlated well with the corresponding measurements in H&E staining of tissue sections (y = 1.09x + 0.08) (Fig. 4C). A statistical analysis indicated that MRI results can readily differentiate the tumor area from the healthy liver tissue, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.84 (Fig. 4D). IHC staining of S100 and CXCR4 further confirmed the lesional areas to be metastatic UM and the CXCR4 expression on metastatic UM (Fig. 4B). Following the same imaging protocol, a mouse model with Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection, in place of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, exhibited post-injection enhancement of metastases (fig. S5B).

Fig. 4. MRI images of metastatic UM mice M20-09-196 and histological correlation.

(A) T1-weighted spin echo and T2-weighted fast spin echo MR images of M20-09-196 before and 48 hours after Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection. At 48 hours after injection, both T1- and T2-weighted MR images revealed four lesions not observed before injection. The zoom-in view of the yellow rectangular region shows both gray and color scales. (B) H&E and IHC staining of M20-09-196 liver with UM metastases. H&E staining revealed four metastatic lesions, highlighted by different color circles, with similar locations as the metastases in MRI images. Higher-magnification images identified the growth pattern of metastases to be nodular pattern. S100 IHC labeling confirmed that the lesions were metastatic UM. CXCR4 immunohistological staining confirmed the CXCR4 expression on UM metastases. (C) The measurement of distances between metastases and the diameter of metastases in MRI images correlates with the H&E histological staining (y = 1.09x + 0.08). (D) Statistical analysis indicated that Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 provides diagnostic validation for UM metastases in the liver. AUC = 0.84; P < 0.0001. Three mice were used for the experiment. Analyses were based on 11 metastases found on MR images. a.u., arbitrary units.

Molecular MDCI and tumor permeability of ProCA32.CXCR4

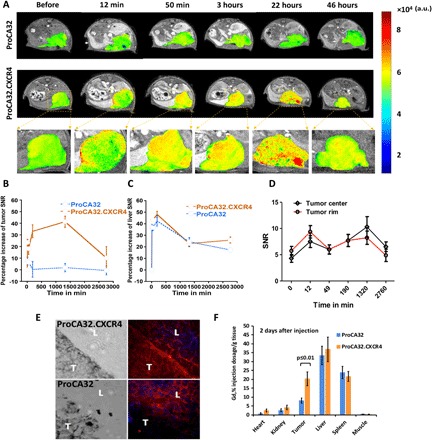

We further evaluated and validated in vivo the molecular imaging capability of ProCA32.CXCR4 at 4.7 T by generating a liver-implanted UM murine model by inoculation of the Mel290 UM cell line. Molecular dynamic contrast imaging (MDCI) was performed to display implanted UM tumor in mouse liver by administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 via intravenous injection, followed by the acquisition of T1-weighted gradient echo MRI as a function of time. The nontargeted contrast agent Lys-ProCA32 was used as a control. The tumor regions exhibited different enhancement patterns between mice with Lys-ProCA32 and Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection. In implanted Mel290 mice with Lys-ProCA32 injection, the tumor MRI signal intensity increased at 12 and 50 min after injection and decreased 3 hours after injection (Fig. 5A). However, the tumor MRI signal intensity in the Mel290 mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection gradually increased to the maximum at 22 hours after injection and then began to decrease due to excretion (Fig. 5A). The time plot of UM tumor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) change followed by Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection showed that UM tumor SNR increased more than 40% at 22 hours after injection when compared with before injection, whereas SNR of tumor region in the Mel290 mice with Lys-ProCA32 injection showed a mild increase (10%) immediately after injection (12 min) and then washed out at 3 hours after injection (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, MRI results of Mel290 mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32 injection exhibited similar patterns of SNR changes in the liver regions over time (Fig. 5C). The liver SNR of both mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32 injection increased drastically right after injection and up to 3 hours, with a percentage increase of SNR of approximately 45% at 3 hours after injection when compared with before injection. This enhancement of the liver region gradually decreased due to elimination. Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 was observed to target and distribute across the tumor tissue in Mel290 mice. The MRI of tumor regions in Mel290 mice following Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection revealed enhancement of the tumor rim immediately after injection and rapid penetration into the center (Fig. 5, A and D). The immunofluorescence staining of the administered Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 into Mel290 murine tumor tissue exhibited intense and broadly distributed red immunofluorescence labeling (Fig. 5E). In contrast, red fluorescence staining was not observed with the tumor tissues of the Mel290 mice receiving the Lys-ProCA32 injection. Gd3+ content analysis using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) indicated that the tumor tissue of Mel290 mice receiving the Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection exhibited significantly higher Gd3+ content than tumor tissue of Mel290 mice with the Lys-ProCA32 injection (Fig. 5F). These results further validated the CXCR4-targeting capability of ProCA32.CXCR4 in vivo with good tumor permeability.

Fig. 5. Progressive MR images of the intrahepatic heterotopic xenotrasplantation UM mice (n = 3 for each group) with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration.

(A) T1-weighted gradient echo MR images of control mice (with injection of nontargeted agent Lys-ProCA32) and mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection. MRI scans were acquired before and after injection at different time points until 46 hours; tumors are represented by the heat map in MRI images. (B) Percentage increase of SNR of melanoma tumors at different time points shows the dynamic binding process of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4. For mice that received the Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection, a gradual increase of intensity in melanoma tumor region was observed up to 24 hours, showing the CXCR4-targeting effect, followed by washing out at 46 hours (further time points not acquired). (C) Time plot of the liver SNR percentage increase following Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32 injection. The liver SNRs of mice receiving Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32 exhibited similar patterns of the SNR time plots, where the liver intensity substantially increased up to 3 hours after injection of both contrast agents, followed by loss of intensity after 3 hours. (D) Time plot of tumor rim and tumor center SNR change of mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration. Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited good tumor permeability; tumor rim SNR was enhanced at early time points (12 min after injection). SNR enhancement gradually penetrated to the center of the tumor. At 24 hours after injection, the view of the tumor region following Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection revealed broad distribution and heterogeneous enhancement. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32 in the liver (L) and tumor (T) of Mel290 mice. For mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection (top), Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 accumulated in the UM tumor tissue (denoted by red fluorescence). For the mice injected with Lys-ProCA32 (bottom), UM tumors exhibited dark fluorescence intensity relative to the UM tumor regions of the mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection. (F) ICP-OES analysis of Gd3+ tissue distribution 2 days after injection of ProCAs. Mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection exhibited significantly more Gd3+ distribution in tumor tissue than mice that received Lys-ProCA32 injection (P < 0.01).

Validation of the in vivo CXCR4 targeting capability of ProCA32.CXCR4 by receptor blocking experiment

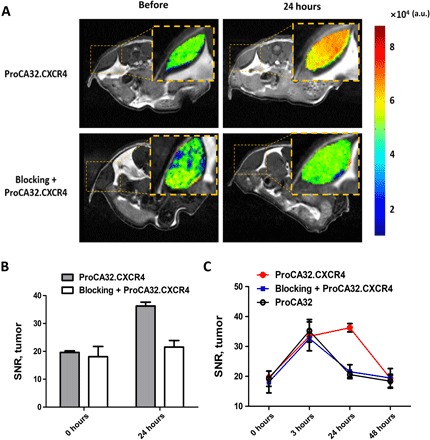

We validated the in vivo CXCR4 targeting capability of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 by receptor blocking experiment. A subcutaneous UM murine model was developed to demonstrate that UM tumor signal intensity enhancement following Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration could be blocked by first administering the CXCR4 blocking reagent (Fig. 6A). We specifically constructed a CXCR4 blocking reagent by fusing the CXCR4-targeting moiety (LGASWHRPDKFCLGYQKRPLP) of ProCA32.CXCR4 to the C terminus of glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag to ensure proper blocking. Injection of the nontargeted Lys-ProCA32 only resulted in initial SNR enhancement at 3 hours after administration due to blood pool distribution. This enhancement returned to baseline at 24 hours. In contrast, injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 resulted in maximum SNR enhancement at 24 hours after injection and returned to the baseline at 48 hours. Previous injection of CXCR4 receptor blocking reagent specifically eliminated the enhancement at 24 hours by Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 but retained the 3-hour initial enhancement due to blood pool effect (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S6). These results support the view that ProCA32.CXCR4 is able to specifically bind to the CXCR4 receptor overexpressed on the tumors and enables molecular targeting MRI.

Fig. 6. Validating CXCR4 binding specificity by receptor blocking study (n = 3 for each group).

(A) Comparison of subcutaneous UM tumor intensity change on T1-weighted MRI images following administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 with and without previous administration of blocking reagent; subcutaneous UM tumors are represented by color heat map. Tumor from UM mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection showed significant increase in MRI signal intensity after Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration. This enhancement could be blocked by first administrating the CXCR4 receptor blocking reagent. (B) Comparison of UM tumor SNR change following administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4. For the mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection, the SNR of UM tumor substantially increased at 24 hours after administration. This enhancement was blocked by first administrating a blocking reagent. As seen with the mice that received the blocking reagent and then the Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection, the SNR of UM tumor was notably lower in comparison with the UM tumor SNR of the mice with Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration. (C) UM tumor SNR change following administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, and Lys-ProCA32. At 3 hours after administration, mice from all three groups showed an SNR increase. At 24 hours, mice with blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration and mice with Lys-ProCA32 administration showed SNR washout, while mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited further SNR increases compared with 3 hours. At 48 hours, mice that received blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and mice that received Lys-ProCA32 administration exhibited a further SNR decrease. Mice that received Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 administration showed SNR washout at 48 hours in comparison with 24 hours.

Toxicity study of ProCA32.CXCR4

A detailed pharmacokinetic study was carried out to study the bioavailability of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4. The AUC0-72h (fig. S7A) of ProCA32.CXCR4 was 113.20 μg·h/ml. The clearance of ProCA32.CXCR4 was 0.31 ml/min per kilogram, slightly less than Eovist (0.4 ml/min per kilogram). ProCA32.CXCR4 had a half-time of 9.19 hours, with a mean residence time of 19.58 hours. The biodistribution study using ICP-OES showed very low amounts of Gd3+ in the brain [0.07% injection dosage (ID)/g tissue] at 5 days after injection of ProCA32.CXCR4 (fig. S7), with the liver displaying the highest concentration of Gd3+ (21.3% ID/g tissue). The biodistribution studies of Gd3+ demonstrated no potential Gd3+-dependent toxicity via brain deposition. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Alanine transaminase (ALT) levels of the mice injected with ProCA32.CXCR4 were comparable with levels from control mice. Albumin, total bilirubin, bilirubin-conjugated, and bilirubin-unconjugated levels in mice injected with ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibited no substantial differences when compared with control mice (table S2). Detailed histological analyses of brain, liver, spleen, muscle, and kidney tissues showed no observable tissue damage (fig. S8). Thus, injection of ProCA32.CXCR4 did not indicate acute toxicity in the mouse study.

DISCUSSION

The liver is a common site for cancer metastases. UM almost exclusively metastasizes to the liver. The mechanism of the liver-specific metastases is not well understood. One of the hypotheses in the field postulates that tumor cells that overly express CXCR4 hijack the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis during the metastatic process and spread to the liver (13–15). This hypothesis is based on the findings that the liver microenvironment in UM is rich in multiple chemoattractants including CXCL12, the natural ligand of CXCR4 (24), and CXCR4 was found to be overexpressed on UM cells in several UM cell line studies (17, 25). CXCR4 is proposed to be a prognostic marker in multiple malignancies, including acute myelogenous leukemia, breast cancers, colorectal cancers, and cutaneous melanoma (17, 26–28). Thus, development of imaging agents for CXCR4 may be used as a diagnostic biomarker in cancer and potentially as a prognostic factor.

In this investigation, we validated the diagnostic value of CXCR4 as an imaging biomarker in UM by demonstrating elevated CXCR4 expression in three different biological systems: UM patient liver metastases, UM cell lines, and an in vivo UM murine model. Multiple attempts have been made toward the development of CXCR4 molecular imaging agents over the years using different imaging technologies including Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), PET, and near-infrared imaging (29–31). MRI has the advantage of being able to provide high spatial resolution imaging without ionizing radiation and depth limitation. Despite this advantage, the application of MRI in molecular imaging is very challenging due to the sensitivity of current contrast agents and the low concentration of biomedical receptors presented on the tumor cell surface (32). To overcome these challenges, we developed a CXCR4-targeted MRI contrast agent, ProCA32.CXCR4, which exhibits 8- to 10-fold increases in both r1 and r2 relaxivities over clinical GBCA and enables sensitive MRI detection of CXCR4. We generated a metastatic UM mouse model by inoculation of M20-09-196 melanoma cells to demonstrate the imaging capacity of ProCA32.CXCR4. MRI following ProCA32.CXCR4 administration is able to detect UM micrometastases (Fig. 4A and fig. S5B) as small as 0.1 mm3 in murine livers, which is a notable improvement in the detection limit of MRI for liver lesions (10). Several factors contributed to the robust detection of micrometastases at early stages. First, CXCR4 targeting enabled ProCA32.CXCR4 accumulation at metastasis sites. Second, the high relaxivities of ProCA32.CXCR4 substantially improved the sensitivity of MRI. ProCA32.CXCR4 has a secondary coordination shell and optimized rotational correlation time, which contributes to the improvement in relaxivities compared with small molecule chelators (33). Furthermore, both high r1 and r2 of ProCA32.CXCR4 increased the confidence in the system and avoided artifacts of detection by applying both T1- and T2-weighted acquisition. Another challenge in imaging UM metastases in the liver is to identify pathological growth patterns of metastases with MRI (11). MR images of M20-09-196 mice following administration of ProCA32.CXCR4 exclusively enhanced nodular growth pattern metastases, and this may provide an approach to identify nodular growth pattern lesions with MRI.

Administration of ProCA32.CXCR4 achieved detection of liver metastases using MDCI by MRI. In the Mel290 murine model, intensity changes over time exhibited different patterns in UM than in adjacent liver tissue (Fig. 5, B and C). Tumor region intensity steadily increased up to 24 hours after Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 injection due to in vivo dynamic binding to CXCR4, followed by slow washout after 24 to 48 hours. We measured a transient increase (at 12 min) immediately after Lys-ProCA32 injection due to in vivo distribution, with subsequent washout after 3 hours. Similar enhancement patterns were observed in the liver regions of mice injected with both Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32. This special property of ProCA32.CXCR4 provides a possibility of acquiring MDCI using MRI. MDCI provides an additional avenue to noninvasively differentiate tumors from healthy livers by taking advantage of biomarker binding capabilities. In this study, we also demonstrated that ProCA32.CXCR4 exhibits excellent tumor permeability, which is very different from most nanoparticles or chelator-based targeting contrast agents that mostly enhance the tumor boundary (34). This property allows the mapping of heterogeneous CXCR4 expression inside the tumor (Fig. 5, A and D) and may facilitate monitoring of changes in CXCR4 expression through the tumor tissue during progression and treatment.

Since the FDA approval of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) in 1988, GBCAs have been widely used for clinical MRI imaging. However, the potential for NSF and Gd3+ brain deposition in patients and animals has raised concerns over the use of GBCAs (35–37). We have carefully considered these factors in the design of ProCA32.CXCR4 for translation into the clinic. The Gd3+ binding sites of ProCA32.CXCR4 were designed to balance Gd3+ binding for safety and water accessibility for relaxivities. ProCA32.CXCR4 has been shown to exhibit unprecedented Gd3+ kinetic and thermodynamic stability, with a log (KGd) of ProCA32.CXCR4 calculated at 21.89. Metal selectivity values of ProCA32.CXCR4 for Gd3+ over Zn2+ and Ca2+ are 106 to 1012 times greater than the clinically approved contrast agents Dotarem and ProHance. The inertness of ProCA32.CXCR4 in the presence of Zn2+ verified its strong stability against transmetalation. Moreover, the improved relaxivity of ProCA32.CXCR4 enabled excellent contrast enhancement in vivo with 75% reduction of Gd3+ dosage compared with other GBCAs. Acute toxicity and tissue/organ toxicity in the in vivo model were not observed. Collectively, ProCA32.CXCR4 has a safe profile, which includes strong Gd3+ binding affinity, unique metal selectivity, and inertness against transmetalation. In addition, no acute toxicity and/or tissue/organ toxicity was observed in the in vivo model. These results strongly support the safety of ProCA32.CXCR4 for diagnostic use due to the observed strong Gd3+ binding affinity, unique metal selectivity, and inertness against transmetalation.

We acknowledge potential limitations in the translatability of our system, as images with best tumor enhancement happened between 24 and 48 hours after injection. We are in the process of optimizing polyethylene glycol (PEG) modification of ProCA32.CXCR4 to tune the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties. We are aware that CXCR4 can be expressed on normal cells (i.e., immune cells). Further studies will be conducted to more extensively evaluate ProCA32.CXCR4 before it can be considered for clinical applications.

The present research validates our hypothesis that CXCR4 may be a diagnostic imaging biomarker for liver metastases. These results were measured using UM patients’ samples, UM cell lines, and animal models. In addition, we successfully designed a CXCR4-targeting protein-based contrast agent, ProCA32.CXCR4, for early detection of UM hepatic metastases. The detected liver micrometastases were validated by histological analyses and correlated with MRI results. Collectively, our results indicate that this contrast agent can enable precision MRI capable of defining molecular signatures for identifying metastases and possibly for treatment stratification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IHC analysis

Metastatic liver tissue from UM patients was immunolabeled with anti-CXCR4 antibodies for IHC analyses. Briefly, liver tissue was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks. These blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm for the labeling. Paraffin-embedded sections were first deparaffinized and rehydrated following a mixture of one part of 30% hydrogen peroxide and nine parts of absolute methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase activity for 10 min. Samples were then washed three times using tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST), 5 min each wash. Antigen retrieval was achieved by boiling in target retrieval solution (Agilent Technologies) for 20 min. Slides were washed as before prior to blocking in a 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in TBST for 2 hours. Samples were incubated in a 1:300 dilution of the anti-CXCR4 primary antibody (Abcam, 12G5, ab189048) in TBST overnight at 4°C. IHC staining was performed with a red chromogen kit following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Counterstaining of the nucleus was performed with hematoxylin. A CXCR4-positive control (brain specimen) was processed with the same protocol. All cases of UM hepatic metastases exhibited high expression of CXCR4, indicated by the red-labeling intensity.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was performed to measure the percentage of CXCR4+ UM cells. Cultured human UM cells were dissociated with a non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), washed, and immunolabeled for 20 min at 4°C with an allophycocyanin (APC) mouse anti-human CD184 antibody (CXCR4 is also known as CD184, clone 12G5) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data acquisition was performed using a BD FACSAria IIu cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) was used for data analysis.

Molecular cloning, expression, purification, and PEGylation of ProCA32.CXCR4

ProCA32.CXCR4 was constructed by engineering a CXCR4-targeting moiety (LGASWHRPDKFCLGYQKRPLP) to the C terminus of ProCA32; PEGylation was performed for surface modification. ProCA32.CXCR4 was expressed in BL21 (DE3) pLysS cell strain and purified following our established protocol (20). Two site-specific PEGylations, cysteine PEGylation and lysine PEGylation, were used for ProCA32.CXCR4 surface modification. For cysteine PEGylation, ProCA32.CXCR4 solution [concentration between 1 and 10 mg/ml, in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2)] was degassed by bubbling with nitrogen. Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) solution was used to reduce disulfide bonds at room temperature for 20 min. Methoxy PEG maleimide (JenKem Technology) with a molecular weight of 2 kDa was reacted with reduced ProCA32.CXCR4 at a molar ratio of 1:1 overnight at 4°C. For lysine PEGylation, ProCA32/ProCA32.CXCR4 solution [concentration between 1 and 10 mg/ml, in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2)] was reacted with methoxy PEG succinimidyl carboxymethyl ester reagent (molecular weight of 2 kDa, JenKem Technology) at a molar ratio of 1:5 overnight at 4°C. Purification of the PEGylated protein sample was achieved by fast protein liquid chromatography. The PEGylation product was evaluated with Coomassie blue staining and iodine (I2) staining (fig. S1).

Determination of r1 and r2 relaxivity values

The relaxation times (T1 and T2) of ProCA32.CXCR4 were measured with 1.5 T Bruker minispec relaxometer and 7.0 T Bruker MRI scanner. We tested different concentrations of ProCA32.CXCR4 and GdCl3 (1:2) prepared in a solution of 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, with a pH of 7.2. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour before measurement. T1 and T2 relaxation times of ProCA32.CXCR4 at 1.5 T were measured by a 1.5 T Bruker minispec relaxometer, and longitudinal (r1) and transverse (r2) relaxivities were calculated in Eq. 1. The slopes of curves were the r1 and r2 relaxivities (fig. S2A). Relaxivities of ProCA32.CXCR4 at 7.0 T were measured with a 7.0 T Bruker MRI scanner with saturation recovery and spin echo sequence (fig. S2B). Commercially available GBCAs (i.e., Dotarem, Magnevist, and Eovist) were prepared in the same buffer and measured using the same procedures.

| (1) |

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining of CXCR4 was performed on cultured Mel290 and M20-09-196 UM cells. Cultured cells were harvested upon reaching 50 to 70% confluency and fixed on cover slides with 3.7% formaldehyde solution at 4°C. Fixed cells were incubated with 5 μM fluorescein 5-carbamoylmethylthiopropanoic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester-labeled ProCA32.CXCR4 (the control group was incubated with fluorescein-labeled ProCA32) for 1 hour at 37°C. Briefly, the slides were washed thoroughly with TBST buffer, and then the nucleus was labeled using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged with a Zeiss microscope. For the colocalization studies, cells were incubated with fluorescein-labeled ProCA32.CXCR4 followed by blocking with 5% BSA (prepared in TBST buffer) for 20 min at room temperature and overnight incubation with 0.1% dilution of anti-CXCR4 (Abcam, ab189048) at 4°C. UM cells were washed and incubated with a 0.1% dilution of a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Alexa Fluor 555) for 60 min at room temperature. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was applied for nuclear labeling before slides were covered and sealed. Colocalization analyses of red fluorescence (555-nm excitation) and green fluorescence (488-nm excitation) were done using Fiji’s plugin coloc2 (Fig. 2C).

Flash-frozen liver tissues of Mel290-inoculated mice were collected after injection of either ProCA32.CXCR4 or ProCA32 (control group) (Fig. 5E). Liver cryosections (4 μm) were thawed at room temperature for 20 min and rehydrated with TBST. Tissue sections were surrounded with a hydrophobic barrier using Dako pen (Agilent) and blocked with 5% BSA for 60 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with an anti-ProCA32.CXCR4 or anti-ProCA32 primary antibody (1:50 dilution) for 60 min at room temperature. After thoroughly washing with TBST, tissue slides were incubated with 0.1% dilution of goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Alexa Fluro 555) for 60 min at room temperature. Nuclear labeling proceeded by using DAPI (Thermo Fisher); slides were covered and sealed.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

An indirect ELISA assay was used to quantify the CXCR4-targeting capability. Cell lysates of Mel290 cells in NaHCO3 solution (pH 9.6) were incubated in 96-well plates overnight at 4°C. The 96-well plates were washed thoroughly in TBST buffer and blocked by 5% BSA solution (prepared in TBST) for 60 min at room temperature. Different concentrations of ProCA32.CXCR4, ranging from 0 to 5000 nM prepared in TBST, were added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. A 0.1% solution with an anti-ProCA32.CXCR4 antibody (in-house polyclonal rabbit antibody) was added for 60-min incubation at room temperature. As a secondary antibody, we used a stabilized goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody (Pierce) for 45 min at room temperature. After washing with TBST, 100 μl of 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added into each well to visualize the color change. When a blue gradient color was observed, 100 μl of 1 M H2SO4 was added into each well to stop the reaction. The absorbance intensity at 450-nm wavelength was measured by a FLUOstar OPTIMA plate reader, and data were plotted using GraphPad Prism 5.

Metal binding studies

The Gd3+ binding affinity of ProCA32.CXCR4 was investigated by a Tb3+ competition assay in a chelator buffer system (20). QM1 fluorescence spectrophotometer (PTI) was used to collect fluorescence spectra at room temperature. A Tb3+ luminescence resonance energy transfer (LRET) experiment was used to determine the Tb3+ binding affinity of ProCA32.CXCR4. Tb3+ LRET emission spectra were recorded from 500 to 600 nm wavelength with tryptophan excitation at 280 nm (fig. S4A). The chelator buffer system consisted of 30 μM ProCA32.CXCR4, 5 mM diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA), 50 mM HEPES, and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.2). DTPA is a strong chelator (Kd = 10−21 M, 25°C, National Institute of Standards and Technology). Upon titration of different concentrations of Tb3+ titrated into the solution, the “free” Tb3+ concentration can be calculated by

| (2) |

where [Tb-DTPA] is the Tb3+ -DTPA complex concentration, and it is assumed that the “free” Tb3+ triggered the terbium-tryptophan LRET and caused fluorescence signal change. The Tb3+ binding affinity to ProCA32.CXCR4 was determined by

| (3) |

where f is the fractional LRET signal change and n is the Hill number.

Gd3+ binding affinity of ProCA32.CXCR4 was determined by competing with Tb3+-loaded ProCA32.CXCR4. ProCA32.CXCR4 (10 μM) and Tb3+ (20 μM) were prepared in 5 mM DTPA, 50 mM HEPES, and 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.2. Different concentrations of Gd3+, ranging from 0 to 200 μM, were added and incubated overnight. Gd3+ replacement of Tb3+ in the ProCA32.CXCR4 binding pockets resulted in a signal decrease in fluorescence spectra (fig. S4B), and an apparent Kd of Gd3+ competition was calculated by

| (4) |

where f is the fractional LRET signal change, [Tb]T is the total Tb3+ concentration, [Gd]T is the total Gd3+ concentration, and Kdapp is the apparent dissociation constant of Gd3+ in competition with Tb3+.

The dissociation constant of Gd3+ with ProCA32.CXCR4 was then calculated by

| (5) |

where KdTb,ProCA32.CXCR4 is the dissociation constant of Tb3+ with ProCA32.CXCR4 and [Tb3+]T is the total Tb3+ concentration.

The dissociation constant between ProCA32.CXCR4 and Ca2+ was determined in an EGTA buffer system. ProCA32.CXCR4 (10 μM) was prepared in EGTA buffer [5 mM EGTA, 50 mM HEPES, and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.2)]. Free Ca2+ concentration was calculated by Tsien’s assay (38), using Eq. 6

| (6) |

The tryptophan fluorescence change triggered by the increase of the free calcium (fig. S4D), Kd of Ca2+ binding to ProCA32.CXCR4, can be fit by

| (7) |

where f is the fractional fluorescence change, [Ca2+]free is the free Ca2+ concentration, and n is the Hill number.

The dissociation constant between Zn2+ and ProCA32.CXCR4 was determined by a modified fluorescence competition assay, where 2 μM ZnCl2 and FluoZin-1 (Thermo Fisher) were combined in a 1:1 ratio. Different concentrations of ProCA32.CXCR4 were titrated into the sample, and fluorescence emission spectra were recorded from 500 to 600 nm following excitation at 495-nm wavelength (fig. S4C). The apparent Kd of ProCA32.CXCR4 -Zn2+ competition was calculated by

| (8) |

where [Zn]T is the total Zn2+ concentration, [ProCA.CXCR4]T is the total ProCA32.CXCR4 concentration, and Kdapp is the apparent dissociation constant. Using the known dissociation constant of Zn2+ to Fluozin-1, the dissociation constant between Zn2+ and ProCA32.CXCR4 was calculated using Eq. 9

| (9) |

where Kdapp is the apparent dissociation constant of ProCA32.CXCR4 and Zn2+ in competition with Fluozin-1.

Transmetalation studies

To characterize the resistance of the Gd3+-ProCA32.CXCR4 complex to transmetalation by endogenous ions such as Zn2+, a relaxometric transmetalation assay was performed using a previously reported test by Laurent and colleagues (39). Briefly, ProCA32.CXCR4 and other GBCA were mixed with the same concentration of ZnCl2 chloride (2.5 mM) in pH 7 phosphate buffer. The final mixture contained 0.026 M KH2PO4, 0.041 M Na2HPO4, 2.5 mM Gd3+ complex, and 2.5 mM ZnCl2. When transmetalation of Gd3+ by Zn2+ occurs, insoluble GdPO4 formed and a decreased proton relaxation rate was observed. The longitudinal relaxation rate change of the mixture reflected the transmetalation process of Gd3+ by Zn2+, and the thermodynamic index was calculated by r1 of the mixture after incubation in the presence of Zn2+ over the initial r1 of GBCA (fig. S3B).

Serum stability studies

A volume of 150 μl from a 500 μM ProCA32.CXCR4 was combined with 150 μl of mouse serum and incubated at 37°C to study serum stability. A total of 15 μl of each sample was taken after 3 hours, 4 hours, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 14 days of incubation. Samples were boiled for 10 min after being mixed with 2 μl of 1 M EGTA solution and SDS buffer and analyzed by Ponceau S assay (fig. S3A).

Animal studies

All animal experiments performed in this study complied with Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and complied with an animal protocol reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia State University and University of Georgia.

For intraocular melanoma mouse model with hepatic metastases, human UM M20-09-196 cells were inoculated into 10-week-old female NU/NU mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate the intraocular melanoma mouse model. Aliquots of 106 UM cells were suspended in 2.5 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and then inoculated into the suprachoroid space of the right eye of each nude mouse using a transcorneal technique. The mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine mixture. A tunnel was prepared from the limbus within the cornea, sclera, and ciliary body to the choroid with a 301/2-gauge needle under a surgical microscope. The tip of a 10-μl glass syringe with a 31-gauge/45° point metal needle (Hamilton, Reno, NV) was used to introduce the cell suspension into the suprachoroid space through the needle track. The eyes were enucleated after 2 weeks of inoculation.

Ten-week-old female NU/NU mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used to establish the intrahepatic heterotopic xenotransplantation tumor model. Mel290 cells were cultured and resuspended in sterile PBS buffer. The mice were anesthetized with a ketamine and xylazine mixture and placed in a supine position. A small incision was made along the right flank of the mouse. The liver was exposed with a small retractor. A surgical microscope was used to guide a 301/2-gauge needle into the liver until its point reached just below the liver subcapsule. Two million Mel290 cells were inoculated in a volume of 20 μl of PBS. The needle was then carefully removed at the same time that a sterile swab held to the injection site. The formation of white cell bulla between hepatic parenchyma and the capsule was the criterion for a successful injection. The incision was sutured with a 5-0 absorbable suture. After 2 to 3 weeks following Mel290 cell injection, melanoma tumors formed in the liver.

Ten-week-old female NU/NU mice were used for the subcutaneous UM murine model. Aliquots of 2 × 106 Mel290 cells were suspended in 50 μl of PBS buffer mixed with 50 μl of Matrigel Matrix (Corning Life Science) and injected subcutaneously on both the right and left side of the back of NU/NU mice. After 6 weeks, subcutaneous tumors of 60 to 120 mm3 in volume were formed.

MRI scan

M20-09-196 mice were scanned with a 7.0 T Agilent MRI scanner at University of Georgia. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane gas. The respiration rates of animals were monitored throughout the MRI scanning and controlled at 70 to 80 times per minute. T1- and T2-weighted images were collected by spin echo and fast spin echo sequence before and after one bolus injection of Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 or Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (0.025 mmol/kg) at 3, 24, and 48 hours. Control mice were injected with one bolus at the same dosage of Lys-ProCA32 and imaged at the same time points with the same parameters. The parameters of spin echo sequence were as follows: repetition time (TR), 500 ms; echo time (TE), 14.89 ms; field of view (FOV), 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm by a matrix of 512 × 512; thickness, 1 mm with no gap. The parameters of fast spin echo sequence were as follows: TR/echo spacing (ESP), 4000 ms/ 10 ms; FOV, 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm by a matrix of 512 × 512; thickness, 1 mm with no gap.

Intrahepatic xenotransplantation Mel290 mice MR images were all collected on a 4.7-T small-bore Varian MRI scanner at Emory University. Mice were anesthetized following similar procedure, and T1-weighted images were collected before and after one bolus injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (0.025 mmol/kg) at 12 min, 50 min, and 3, 22, and 46 hours by gradient echo sequence. The parameters of gradient echo sequence were as follows: TR/TE, 140 ms/11 ms; FOV, 4 cm × 4 cm by a matrix of 512 × 512.

Subcutaneous Mel290 tumor mice MRI results were acquired with a 7.0 T Bruker MRI scanner at Yerkes National Primate Research Center. Mice were anesthetized following a similar procedure as detailed above, and T1-weighted images were collected before and after one bolus injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 or Lys-ProCA32 (0.025 mmol/kg) at 3, 24, and 48 hours. Blocking group mice received intravenous injections of CXCR4 blocking reagent (0.025 mmol/kg) 24 and 12 hours before the injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4. The parameters of the rapid imaging with refocused echoes (RARE) sequence were as follows: TR/TE, 560 ms/11 ms; FOV, 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm by a matrix of 256 × 256. MRI data were processed and analyzed by Fiji and MRIcron.

Organ distribution analysis by ICP-OES

ICP-OES was used to analyze the Gd3+ distribution in different mouse organs after injection of ProCA32.CXCR4. Healthy CD-1 mice were injected with a bolus dosage of ProCA32.CXCR4 (0.025 mmol/kg). Animals were euthanized 46 hours after receiving an injection of ProCA32.CXCR4, and heart, liver, spleen, kidney, brain, and muscle tissues were subsequently collected and used for ICP-OES analysis. Tissues (0.1 to 0.5 g) were dissolved overnight in 1 ml of Nitric Acid 67-69%, Optima (Fisher Chemical). Undissolved particles were removed by filtration, and the supernatant was retained for Gd3+ content analysis by ICP-OES (fig. S7B).

Toxicity study

ProCA32.CXCR4 acute toxicity was tested by a bolus injection of 100 μl of 7 mM ProCA32.CXCR4 to 10-week-old healthy CD-1 mice. ProCA32.CXCR4 solutions with two different PEGylation methods (Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4) were tested. Each test group had three mice, and the control group was injected with saline. Mice were observed every 8 hours after injection and then euthanized after 5 days. Terminal blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and serum was transferred immediately to microcentrifuge tube. Plasma was separated from blood cells by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min. Serum samples were used for basic blood biochemistry tests and kidney function tests to measure ALT, ALP, and electrolyte levels (table S2). Tissues including heart, muscle, liver, spleen, kidney, lung, and brain were collected for analysis of gadolinium distribution using ICP-OES.

Pharmacokinetic study

Female CD-1 mice (8 to 10 weeks old) were used to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4. Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (100 μl, 0.025 mmol/kg) was administered through tail vein injection. Blood samples were collected at various time points using the saphenous vein up to 7 days using a sparse sampling design (three to six animals per time point). Immediately following blood sample collection, samples were stored on ice, serum was obtained through centrifugation, and Gd3+ concentration was determined using ICP-OES. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the noncompartmental analysis tool of Phoenix WinNonlin software. The areas under the concentration-time curve (AUClast and AUCinf) were calculated using a linear trapezoidal rule. The clearance and volume of distribution (Vss) were estimated following intravenous dose administration. The elimination rate constant value (k) was obtained by linear regression of the log-linear terminal phase of the concentration-time profile using at least three declining concentrations in terminal phase with a correlation coefficient of >0.8. The terminal half-life value (T1/2) was calculated using the equation 0.693/k.

Statistical analysis

SNR was calculated by the mean value across different slides of MRI results of the same subjects. Analyses of differences between the two groups were performed using two-tailed Student’s t test in GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). The P values are denoted in figure legends, and differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. No estimation of sample size and blinding was performed for animal studies. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed using R and SAS. AUC was reported to measure the performance of the contrast agent. Mice were randomly assigned to groups for the experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. C. Long for operating the 4.7 T small-animal MRI scanner. We thank S. E. Woodman, T. A. McCannel, and B. L. Burgess for providing cell lines. We thank M. Kirberger for critical review and editing of this manuscript. We thank B. Canup for proofreading of this manuscript. We also thank Z. Liu, L. Yang, H. Mao, and A. Patel for helpful discussion on this project. Funding: This work was supported by NIH research grants (AA112713 and CA183376) to J.J.Y. and Georgia State University Brain & Behavior fellowship to S.T. Author contributions: Conceptualization: S.T. and J.J.Y.; formal analysis: S.T., H.Y., S.X., M.S., R.M., Y.H., P.Z.S., P.M., H.E.G., and J.J.Y.; investigation: S.T., H.Y., J.Q., W.H., F.P., K.H., Y.M., and O.Y.O.; methodology: S.T., H.Y., S.X., and J.Q.; writing (original draft): S.T.; writing (review and editing): S.T., D.L., V.M.M.-T, M.L.Y., and J.J.Y. Competing interests: F.P., S.X., and M.S. are inventors on a patent related to this work filed by Georgia State University Research Foundation Inc. (no. WO2016183223A2, published on 17 November 2016). The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper maybe requested form the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/6/eaav7504/DC1

Fig. S1. PEGylation SDS-PAGE gel of protein contrast agents.

Fig. S2. Determination the relaxivity values of ProCA32.CXCR4.

Fig. S3. Serum stability and transmetalation study of ProCA32.CXCR4.

Fig. S4. Determination of ProCA32.CXCR4 metal binding affinities.

Fig. S5. MRI images of metastatic UM mice M20-09-196 before and after administration of Lys-ProCA32, Eovist, and Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (n = 2 for Eovist group, n = 3 for Lys-ProCA32 and Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 group).

Fig. S6. T1-weighted MRI images of subcutaneous UM mice before and after administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, and Lys-ProCA32 (n = 3 for each group).

Fig. S7. Pharmacokinetic study of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and ICP-OES analysis of Gd3+ content in different mouse organs.

Fig. S8. H&E staining analysis of mice tissues collected 7 and 14 days after injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4.

Table S1. Relaxivities of investigated contrast agents in 10 mM Hepes at 37°C.

Table S2. Clinical pathology profile of mouse serum.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Singh A. D., Topham A., Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973-1997. Ophthalmology 110, 956–961 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group , Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS): COMS report no. 15. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 670–676 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossniklaus H. E., Progression of ocular melanoma metastasis to the liver: The 2012 Zimmerman lecture. JAMA Ophthalmol. 131, 462–469 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossniklaus H. E., Zhang Q., You S., McCarthy C., Heegaard S., Coupland S. E., Metastatic ocular melanoma to the liver exhibits infiltrative and nodular growth patterns. Hum. Pathol. 57, 165–175 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira P. R., Odashiro A. N., Lim L.-A., Miyamoto C., Blanco P. L., Odashiro M., Maloney S., De Souza D. F., Burnier M. N. Jr., Current and emerging treatment options for uveal melanoma. Clin. Ophthalmol. 7, 1669–1682 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvajal R. D., Sosman J. A., Quevedo J. F., Milhem M. M., Joshua A. M., Kudchadkar R. R., Linette G. P., Gajewski T. F., Lutzky J., Lawson D. H., Lao C. D., Flynn P. J., Albertini M. R., Sato T., Lewis K., Doyle A., Ancell K., Panageas K. S., Bluth M., Hedvat C., Erinjeri J., Ambrosini G., Marr B., Abramson D. H., Dickson M. A., Wolchok J. D., Chapman P. B., Schwartz G. K., Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311, 2397–2405 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopper K. D., Singapuri K., Finkel A., Body CT and oncologic imaging. Radiology 215, 27–40 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudkerk M., Torres C. G., Song B., König M., Grimm J., Fernandez-Cuadrado J., Op de Beeck B., Marquardt M., van Dijk P., de Groot J. C., Characterization of liver lesions with mangafodipir trisodium-enhanced MR imaging: Multicenter study comparing MR and dual-phase spiral CT. Radiology 223, 517–524 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffeth L. K., Use of PET/CT scanning in cancer patients: Technical and practical considerations. Proc. (Baylor Univ. Med. Cent.) 18, 321–330 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker-Weidman D. J. S., Kalb B., Sharma P., Kitajima H. D., Lurie C. R., Chen Z., Spivey J. R., Knechtle S. J., Hanish S. I., Adsay N. V., Farris A. B. III, Martin D. R., Hepatocellular carcinoma lesion characterization: Single-institution clinical performance review of multiphase gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging—Comparison to prior same-center results after MR systems improvements. Radiology 261, 824–833 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao A., Mittal P., Lawson D. H., Yang J. J., Szalai E., Grossniklaus H. E., Radiologic and histopathologic correlation of different growth patterns of metastatic uveal melanoma to the liver. Ophthalmology 125, 597–605 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiao J., Li S., Wei L., Jiang J., Long R., Mao H., Wei L., Wang L., Yang H., Grossniklaus H. E., Liu Z.-R., Yang J. J., HER2 targeted molecular MR imaging using a de novo designed protein contrast agent. PLOS ONE 6, e18103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ara T., Tokoyoda K., Okamoto R., Koni P. A., Nagasawa T., The role of CXCL12 in the organ-specific process of artery formation. Blood 105, 3155–3161 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H., Yang W., Chen P. W., Alizadeh H., Niederkorn J. Y., Inhibition of chemokine receptor expression on uveal melanomas by CXCR4 siRNA and its effect on uveal melanoma liver metastases. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 5522–5528 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobner B. C., Riechardt A. I., Joussen A. M., Englert S., Bechrakis N. E., Expression of haematogenous and lymphogenous chemokine receptors and their ligands on uveal melanoma in association with liver metastasis. Acta Ophthalmol. 90, e638–e644 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deol A., Abrams J., Masood A., Al-Kadhimi Z., Abidi M. H., Ayash L., Ratanatharathorn V., Lum L. G., Uberti J. P., Use of plerixafor to overcome stem cell mobilization failure: Long term follow up of patients proceeding to transplant using plerixafor mobilized stem cells. Blood 118, 4390 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scala S., Ottaiano A., Ascierto P. A., Cavalli M., Simeone E., Giuliano P., Napolitano M., Franco R., Botti G., Castello G., Expression of CXCR4 predicts poor prognosis in patients with malignant melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 1835–1841 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robledo M. M., Bartolomé R. A., Longo N., Rodríguez-Frade J. M., Mellado M., Longo I., van Muijen G. N. P., Sánchez-Mateos P., Teixidó J., Expression of functional chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CXCR4 on human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45098–45105 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harbour J. W., Onken M. D., Roberson E. D. O., Duan S., Cao L., Worley L. A., Council M. L., Matatall K. A., Helms C., Bowcock A. M., Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science 330, 1410–1413 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue S., Yang H., Qiao J., Pu F., Jiang J., Hubbard K., Hekmatyar K., Langley J., Salarian M., Long R. C., Bryant R. G., Hu X. P., Grossniklaus H. E., Liu Z.-R., Yang J. J., Protein MRI contrast agent with unprecedented metal selectivity and sensitivity for liver cancer imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 6607–6612 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin L., Kufareva I., Holden L. G., Wang C., Zheng Y., Zhao C., Fenalti G., Wu H., Han G. W., Cherezov V., Abagyan R., Stevens R. C., Handel T. M., Structural biology. Crystal structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in complex with a viral chemokine. Science 347, 1117–1122 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dozier J. K., Distefano M. D., Site-specific PEGylation of therapeutic proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 25831–25864 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semelka R. C., Ramalho J., Vakharia A., AlObaidy M., Burke L. M., Jay M., Ramalho M., Gadolinium deposition disease: Initial description of a disease that has been around for a while. Magn. Reson. Imaging 34, 1383–1390 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendt M., Cardier J. E., Stromal-derived factor-1 and its receptor, CXCR4, are constitutively expressed by mouse liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: Implications for the regulation of hematopoietic cell migration to the liver during extramedullary hematopoiesis. Stem Cells Dev. 21, 2142–2151 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scala S., Giuliano P., Ascierto P. A., Ieranò C., Franco R., Napolitano M., Ottaiano A., Lombardi M. L., Luongo M., Simeone E., Castiglia D., Mauro F., De Michele I., Calemma R., Botti G., Caracò C., Nicoletti G., Satriano R. A., Castello G., Human melanoma metastases express functional CXCR4. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 2427–2433 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spoo A. C., Lübbert M., Wierda W. G., Burger J. A., CXCR4 is a prognostic marker in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 109, 786–791 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirisola V., Zuccarino A., Bachmeier B. E., Sormani M. P., Falter J., Nerlich A., Pfeffer U., CXCL12/SDF1 expression by breast cancers is an independent prognostic marker of disease-free and overall survival. Eur. J. Cancer 45, 2579–2587 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottaiano A., Franco R., Talamanca A. A., Liguori G., Tatangelo F., Delrio P., Nasti G., Barletta E., Facchini G., Daniele B., Blasi A. D., Napolitano M., Ieranò C., Calemma R., Leonardi E., Albino V., De Angelis V., Falanga M., Boccia V., Capuozzo M., Parisi V., Botti G., Castello G., Iaffaioli R. V., Scala S., Overexpression of both CXC chemokine receptor 4 and vascular endothelial growth factor proteins predicts early distant relapse in stage II-III colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 2795–2803 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss I. D., Jacobson O., Molecular imaging of chemokine receptor CXCR4. Theranostics 3, 76–84 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derlin T., Gueler F., Bräsen J. H., Schmitz J., Hartung D., Herrmann T. R., Ross T. L., Wacker F., Wester H.-J., Hiss M., Haller H., Bengel F. M., Hueper K., Integrating MRI and chemokine receptor CXCR4-targeted PET for detection of leukocyte infiltration in complicated urinary tract infections after kidney transplantation. J. Nucl. Med. 58, 1831–1837 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan G., Lu Y., Zhu X., Liu L., Chen J., Ma Q., Zhang Y., Wen Y., Yang L., Liu T., Wang W., Ran H., Qiu X., Ke S., Zhou Y., CXCR4-targeted near-infrared imaging allows detection of orthotopic and metastatic human osteosarcoma in a mouse model. Sci. Rep. 5, 15244 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunn A. D., Linder K. E., Tweedle M. F., Can receptors be imaged with MRI agents? Q. J. Nucl. Med. 41, 155–162 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue S., Qiao J., Jiang J., Hubbard K., White N., Wei L., Li S., Liu Z.-R., Yang J. J., Design of ProCAs (protein-based Gd3+ MRI contrast agents) with high dose efficiency and capability for molecular imaging of cancer biomarkers. Med. Res. Rev. 34, 1070–1099 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Z., Wu X., Kresak A., Griswold M., Lu Z. R., Peptide targeted tripod macrocyclic Gd(III) chelates for cancer molecular MRI. Biomaterials 34, 7683–7693 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marckmann P., Skov L., Rossen K., Dupont A., Damholt M. B., Heaf J. G., Thomsen H. S., Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 2359–2362 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanda T., Fukusato T., Matsuda M., Toyoda K., Oba H., Kotoku J., Haruyama T., Kitajima K., Furui S., Gadolinium-based contrast agent accumulates in the brain even in subjects without severe renal dysfunction: Evaluation of autopsy brain specimens with inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy. Radiology 276, 228–232 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adin M. E., Kleinberg L., Vaidya D., Zan E., Mirbagheri S., Yousem D. M., Hyperintense dentate nuclei on T1-weighted MRI: Relation to repeat gadolinium administration. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 1859–1865 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y., A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurent S., Vander Elst L., Henoumont C., Muller R. N., How to measure the transmetallation of a gadolinium complex. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 5, 305–308 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/6/eaav7504/DC1

Fig. S1. PEGylation SDS-PAGE gel of protein contrast agents.

Fig. S2. Determination the relaxivity values of ProCA32.CXCR4.

Fig. S3. Serum stability and transmetalation study of ProCA32.CXCR4.

Fig. S4. Determination of ProCA32.CXCR4 metal binding affinities.

Fig. S5. MRI images of metastatic UM mice M20-09-196 before and after administration of Lys-ProCA32, Eovist, and Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 (n = 2 for Eovist group, n = 3 for Lys-ProCA32 and Lys-ProCA32.CXCR4 group).

Fig. S6. T1-weighted MRI images of subcutaneous UM mice before and after administration of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, blocking reagent + Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4, and Lys-ProCA32 (n = 3 for each group).

Fig. S7. Pharmacokinetic study of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4 and ICP-OES analysis of Gd3+ content in different mouse organs.

Fig. S8. H&E staining analysis of mice tissues collected 7 and 14 days after injection of Cys-ProCA32.CXCR4.

Table S1. Relaxivities of investigated contrast agents in 10 mM Hepes at 37°C.

Table S2. Clinical pathology profile of mouse serum.