Abstract

Objective:

This study examined psychological and sexual health indicators associated with positive feelings and discrimination at the intersection of race and gender among Black gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority men (SMM).

Methods:

Participants were a national sample of 1064 Black SMM (Mdn age= 28) who responded to self-report measures of positive feelings and discrimination associated with being a Black man, psychological distress, self-efficacy, emotional awareness, and sexual HIV risk and protective behavior. Using structural equation modeling, we examined associations between the positive feelings and discrimination scales and the psychological and sexual health indicators. We also tested age as a moderator of these associations.

Results:

Our results indicated that positive feelings about being a Black man were significantly positively associated with self-efficacy (b = 0.33), emotional awareness (b = 0.16), and sexual protective behavior (b = 0.93) and negatively associated with psychological distress (b = −0.26) and sexual risk behavior (b = −0.93). Except for emotional awareness and sexual protective behavior, discrimination as a Black man was also associated with these variables, though to a lesser magnitude for positive health indicators. Moderation results showed that, except for the association between positive feelings and emotional awareness, younger men generally had stronger associations between health indicators and the positive feelings and discrimination scales.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that positive feelings, in addition to discrimination, at the intersection of race and gender may play an important role in the psychological and sexual health of Black SMM, especially earlier in their lives.

Keywords: Intersectionality, African American, MSM, HIV/AIDS, Mental health

Despite a recent increase in efforts to stem health inequities affecting Black gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority men (SMM; CDC, 2018a), these men continue to be vastly disproportionately affected by psychological difficulties (e.g., major depression; APA, 2018) and HIV (CDC, 2018b). For example, HIV seroconversion rates among Black SMM are higher than any country in the world (UNAIDS, 2018), with the highest rates among 13–24 year olds (CDC, 2018a). Recent research suggests that one key reason for these continued rates may be that interventions do not take an intersectional and culturally empathic approach to assessing and addressing risk and resilience among Black SMM (Hermanstyne et al., 2018; Malebranche, 2018; Teti et al., 2012; Reed & Miller, 2016). The development of culturally empathic and effective health interventions to serve Black SMM requires research that examines both positive and negative intersectional experiences and their associations with psychological and sexual health (Malebranche, Fields, Bryant, & Harper, 2009). The present study addresses this gap in the science by assessing associations between positive feelings and discrimination associated with being a Black man and psychological and sexual health indicators among Black SMM.

The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) frames much of the extant literature investigating the link between discrimination and biopsychosocial outcomes among Black SMM. This model identifies that people in marginalized social positions experience stigma and discrimination, such as being denied equitable treatment or access to social services. Minority stress models frame discrimination as a central contributor to the stress processes that lead to higher risk for negative psychological and sexual health outcomes. The intersectionality framework posits that social positions targeted by this discrimination are not independent, but rather are interdependent and mutually constitutive (Collins, 1995, 1998; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). The framework, therefore, asserts that discrimination targeting Black men cannot be understood by simply adding up their experiences associated with being a man and a Black person; but rather must be understood as a distinct experience in and of itself. Thus, to understand current psychological and sexual health inequities among Black SMM, the minority stress and intersectionality frameworks challenge researchers to consider how discrimination targeting individuals at the intersection of multiple and interlocking social positions (e.g., racial and gender identities) affects psychological and sexual health outcomes. These two theoretical models frame the stress model tested in the present study.

Studies examining the psychological and sexual health of Black SMM have provided evidence for minority stress theory, showing positive associations between negative psychological and sexual health outcomes and stigma targeting race (e.g., Arnold, Rebchook, & Kegels, 2014; Hermanstyne et al., 2018; Reed & Miller, 2016), sexual identity (e.g., Beasley, Jenkins & Valenti, 2015), and HIV-status (e.g., Rendina et al, 2016). Research that has taken an intersectional approach has found that stigma at the intersection of social identities also affects psychological and sexual health outcomes for these men (e.g., Arnold et al., 2014). For example, a recent study with Black, Latino, and multiracial SMM found that the interaction between experiences of racial discrimination and sexual minority stigma was positively associated with negative psychological and substance use outcomes among these men (English et al., 2018).

Along with experiences of stigma, positive experiences at the intersection of race and gender for Black SMM have important impacts on their psychological and sexual health (Franklin, 1990; Hampton, Gullotta, & Crowell, 2010). For example, Teti and colleagues (2012) found that some Black men rely on their sense of identity as a Black man to cope with negative experiences linked to stereotypes targeting them. Additional studies have found that community connectedness and a positive sense of self associated with social identities are linked to lower syndemic conditions (e.g., co-occurring depression and substance abuse; Reed & Miller, 2016) and less HIV risk behavior among Black SMM (Hermanstyne et al., 2018; Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996).

These studies notwithstanding, there is relatively little research that has examined outcomes other than stigma and sexual risk among Black SMM (Maulsby et al., 2014). In fact, sexual risk is the most commonly operationalized outcome in health-focused studies with young Black SMM, many of which focus on the impact of stigma (Wade & Harper, 2017). This is critical because a wealth of research indicates that, although the link between stigma and sexual risk is important, it does not completely account for sexual health inequities among Black SMM, as they are less likely to engage in sexual risk (e.g., condomless anal sex) than SMM of other racial/ethnic backgrounds (Rosenberg, Millett, Sullivan, del Rio, & Curran, 2014). Thus, studies that focus solely on contributors to risk may miss the important effects of a range of intersectional experiences linked to both positive and negative psychological and sexual health indicators among Black SMM.

Two protective factors that are theorized to play key roles in discrimination, positive feelings, and psychological and sexual health among Black SMM are self-efficacy and emotional awareness (Bandura, 2001; Hatzenbeuhler, 2009). Self-efficacy is a person’s beliefs about their ability to perform desired actions and/or cope with events in their lives (Bandura, 2001). One study found that Black SMM with more integrated racial and sexual identities reported higher levels of HIV prevention self-efficacy, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and less psychological distress associated with gender roles (Crawford, Allison, Zamboni, & Soto, 2002). Other studies have suggested positive associations between racial identity development and other forms of self-efficacy among Black men (e.g., Okech & Harrington, 2002; Reid, 2013). Emotional awareness includes the tendency to attend to and acknowledge one’s emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Studies have found that this can be an important protective factor among Black men and boys facing discrimination (e.g., Cunningham, Kliewer, & Garner, 2009). In addition, evidence suggests that lower emotional awareness linked to Black masculine ideologies is associated with difficulty managing negative affect following racial discrimination among Black men (Hammond, Banks, & Mattis, 2006), and sexual risk behavior among Black SMM specifically (Malebranche et al., 2009). However, relatively little is known about the interplay between both discrimination and positive feelings at the intersection of race and gender for Black SMM, and their implications for self-efficacy and emotional awareness.

Age may also play a critical role in the experience and effects of discrimination and positive experiences associated with being a Black man among Black SMM. Racial and gender identity exploration typically occur during adolescence into emerging adulthood (Steensma, Kreukels, de Vries, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2013; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014)—developmental periods in which individuals, and particularly SMM, experience spikes in discrimination, psychological difficulties, and sexual risk (Russell & Fish, 2016). Evidence suggests that these increases may be linked such that individuals at higher levels of identity exploration during emerging adulthood may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of identity-related discrimination (e.g., Yip, 2018). This is important for young Black SMM who are often negotiating their understanding and performance of Black masculinity during this period (Strayhorn & Tillman-Kelly, 2013) when gendered racism is particularly salient among Black men (Schwing, Wong, & Fann, 2013). Thus, age likely plays a critical role in the effects of discrimination and positive feelings associated with being a Black man, such that younger Black SMM may be more affected by discrimination and positive feelings than older men.

To inform intersectional, strengths-based, and culturally empathic research and practice, the present study examined psychological and sexual health indicators associated with discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man. We did so by assessing within-group, or intracategorical, intersectional experiences (McCall, 2008) that are unique to Black men using the Black Men’s Experiences Scale (BMES). The BMES is an instrument designed to assess the costs (i.e., overt discrimination and microaggressions) and benefits (i.e., positive feelings) of Black men’s experiences at the intersection of race and gender (Bowleg et al., 2016). Negative health indicators were psychological distress and sexual HIV transmission risk behavior (TRB; i.e., serodifferent/unknown anal sex without a condom or PrEP). Positive health indicators were self-efficacy, emotional awareness, and sexual HIV transmission protective behavior (TPB; i.e., serodifferent/unknown anal sex with a condom). We also examined age as a moderator of the associations between discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man and these health indicators. Our hypotheses were: 1) Discrimination at the intersection of race and gender among Black SMM would be positively associated with psychological distress and TRB, and negatively associated with self-efficacy, emotional awareness, and TPB; 2) Positive feelings about being a Black man would be negatively associated with psychological distress and TRB, and positively associated with self-efficacy, emotional awareness and TPB; 3) Age would moderate these associations such that younger men would have stronger associations between discrimination and positive feelings and health indicators as compared to their older counterparts. As an exploratory aim, we also examined whether each of the associations with health indicators were stronger for positive feelings or discrimination experiences.

Method

We drew our sample from the baseline data of the Understanding New Infections through Targeted Epidemiology study (UNITE). UNITE is a national longitudinal cohort study examining biopsychosocial predictors of HIV seroconversion among SMM at high risk for HIV. The study began enrolling in 2017 and recruited participants using targeted advertisements on social media (e.g., Facebook) and sexual networking sites/applications (e.g., Adam4Adam, Black Gay Chat). If interested, participants completed a brief electronic screener to confirm the following eligibility criteria: 1) being at least 16 years old; 2) currently identifying as male (including transgender men); 3) reporting a non-heterosexual identity; 4) residing and having a mailing address in the U.S.; 5) reporting HIV negative or unknown status; 6) reporting HIV testing in the past 12 months for adults 18 years or older; 7) willingness to complete at-home HIV/STI testing; 8) reporting risk for HIV in the past 6 months, which included at least one of the following: (a) an STI diagnosis, (b) condomless anal sex (CAS) with a casual male partner, with an HIV-positive or unknown status main partner, or with an HIV-negative main partner who reports CAS with other male partners, or (c) receiving a prescription for post-exposure prophylaxis; 9) reporting any app use to find a potential sex partner in the past six months; and 10) reporting not currently using PrEP.

In total, 14,775 Black-identified SMM completed screening, of whom 3,982 (27.0%) were deemed eligible and provided contact information, and 1,439 (36.1%) completed the enrollment survey. The analytic sample was the 1,064 participants who identified as Non-Hispanic Black/African American only (i.e., not part of a multiracial identity; n=1,439), and reported not using PrEP (n=1,182), and engaged in at least one and less than 364 sex acts over the past 90 days (outlier cutoff; n=1,091), and did not have missingness on model covariates (n=1,064). We excluded cases missing on covariates because estimating them as endogenous variables in the models described below would have imposed a distributional assumption of normality (Marcoulides & Schumacker, 1996), which we deemed untenable for categorical (e.g., transactional sex) and positively-skewed (e.g., age) covariate distributions. The 27 men excluded for missingness did not significantly differ from the included 1,064 across any study variables.

After the screener, participants provided informed consent online. Consistent with recommendations from the Society of Adolescent Medicine, the Department of Health and Human Services, and empirical research (Nelson, Carey, & Fisher, 2019), 16 and 17 year-old participants received waivers of parental consent. After consent, participants completed an online survey assessing minority stress, psychosocial variables, and HIV risk. Participants received a $25 Amazon gift card for completing the 30–40 minute CASI. The Institutional Review Board of The City University of New York (CUNY) reviewed and approved all study procedures.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants reported demographics including address (for geocoding), age, education, income, and subjective socioeconomic status (SES, Adler & Stewart, 2007).

Black Men’s Experiences Scale (BMES).

The 12-item BMES assesses experiences with discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man (Bowleg et al., 2016). The BMES instructions read: “The next set of questions is about some experiences you may have had as a Black man.” Respondents answered questions on a 5-point scale (1 = Never to 5 = Very often/Always). We used all three BMES subscales: the 6-item Overt Discrimination subscale that assesses unambiguous discrimination (e.g., “How often have you not been hired for a job…?”); the 3-item Microaggressions subscale that measures experiences of White people’s behavior conveying discomfort and fear (e.g., “How often have White people seemed uncomfortable when they pass you on the street?”); and the 3-item Positives: Black men subscale that assesses positive feelings and/or evaluations of being a Black man (e.g., “How often have you felt that it is a blessing to be a Black man?”). Mean scores for the Microaggressions and Overt Discrimination subscales served as indicators of a discrimination latent variable. The Positives items served as indicators of a positives latent variable. All subscales showed acceptable internal consistency (α= .75 [positives], α= .86 [microaggressions], and α=.89 [overt discrimination]).

Self-Efficacy.

Participants completed the 10-item General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE; Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). The scale assesses a participants’ general and stable sense of competence to effectively deal with different stress-inducing situations (e.g., “I can usually handle whatever comes my way.”). Participants responded on a 4-point scale from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true). The 10 GSE items served as indicators of a self-efficacy latent variable. Studies have found the GSE to be a valid cross-cultural measure of self-efficacy (Luszczynska, Scholzm, & Schwarzer, 2005). The scale showed good internal consistency (α = .89).

Emotional Awareness.

Participants completed the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), including the two-item emotional awareness subscale. This subscale assesses engagement with one’s emotions (e.g., “I am attentive to my feelings”). Participants responded on a scale from 1 (almost never [0–10%]) to 5 (almost always [91–100%]). Research on the DERS factor structure showed that the awareness subscale, the only positively-valenced subscale, had weak latent factor intercorrelations with the other DERS subscales, suggesting it be measured separately (Bardeen, Fergus, & Orcutt, 2012). Thus, we examined it as a stand-alone subscale with the two items serving as indicators of an emotional awareness latent variable in our models. The scale showed good internal consistency (α = .84).

Psychological Distress.

Depressive Symptoms.

Participants received the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-10 (CESD-10; Cole, Rabin, Smith, & Kaufman, 2004). Response options ranged from 0(Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time). We generated a depressive symptoms composite variable by reverse-scoring the positive items and computing a mean across all items. The scale showed good internal consistency (α = .85).

Anxiety Symptoms.

Participants completed the anxiety items of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). This subscale consists of six items that assess symptoms of anxiety (e.g., “feeling tense or keyed up”) in the prior week. Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). We calculated the subscale score by computing a mean across its six items. The scale showed good internal consistency in this study (α=0.89).

Sexual Behavior.

Participants completed a retrospective aggregated recall method assessing sexual behavior over the past 90 days. For every instance of sexual activity, the survey inquired about the sexual partner (e.g., HIV serostatus), including the types of sexual behavior with them (e.g., anal sex with a condom). Research suggests that aggregated recall methods such as this provide an accurate picture of sexual behavior across periods over 30 days as compared to daily methods (Rendina, Moody, Ventuneac, Grov, & Parsons, 2015). For the purposes of these analyses, we calculated the total number of sexual acts and the total number of anal sex acts with a serodifferent or unknown casual partners while using and not using condoms.

Covariates.

To isolate experiences as a Black man from those associated with only racial/ethnic identity or only being a gay man, we adjusted models for the effects of gay community connectedness and racial/ethnic private regard on the health indicators.

Gay Community Connectedness.

Participants completed the 5-item Attachment to the Gay/Bisexual Community Scale to assess gay community connectedness (Carpiano, Kelly, Easterbrook, & Parsons, 2011). Participants recorded responses on a Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 4-strongly agree). This scale showed strong internal consistency (α = .92).

Ethnic Group Membership Questionnaire (EGMQ).

The EGMQ is a 12-item scale that measures race/ethnicity-related stress and perspectives on racial/ethnic group membership (Contrada et al., 2001). We used the 4-item private feelings subscale, which captures one’s own internal regard about their ethnic group membership. Higher scores indicated more positive private regard for one’s ethnic group membership. The response scale was a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). The scale showed acceptable internal consistency (α=.78).

Analytic Approach

Prior to testing the hypothesized model, we ran separate confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) in Mplus 8.2 for all variables specified as latent (BMES subscales, self-efficacy, psychological distress, emotional awareness, and EGMQ scale). We chose to run all CFAs as separate models, even for under- or just-identified models. We did so to obtain valid parameter estimates, and fit indices for over-identified models, that did not include covariances between different constructs. We then tested the primary hypotheses using structural equation modeling. In the primary model, we tested main effects of a latent discrimination variable and a latent positives variable and adjusted for the effects of age, SES, transactional sex, gay community connectedness, and private regard. We specified sexual HIV transmission risk behavior (TRB) and sexual HIV transmission protective behavior (TPB) as count variables with a zero-inflated Poisson distribution to account for the 61% of participants who reported no serodifferent/unknown anal sex with a casual partner. We also used an offset equal to the log of the total number of sex acts. The effect of this offset is to model the rate of TRB and TPB given the overall amount of sex rather than a standard count of each, which can be biased by the number of opportunities individuals had to engage in each act. We clustered observations by U.S. region to adjust for regional variations in study variables. We conducted moderation analyses using the XWITH command to estimate latent variable interactions between the discrimination and positives latent variables and the centered continuous age variable. We regressed the dependent variables on these latent variable interactions (discrimination x age, positives x age) in separate models for each moderated pathway. Therefore, we ran an initial model with no moderated pathways and then 10 moderation models, one for each combination of interaction term and five dependent variables.

After running the hypothesized models, we examined an exploratory aim of whether the discrimination or positives subscales were more strongly associated with the dependent variables. To test this, we compared models that had equality constraints between pathways from the discrimination and positives subscales to models with parameters freely estimated using a log-likelihood ratio test (Gerhard et al., 2015). We multiplied the discrimination subscale by −1 to examine the absolute differences. If the log-likelihood ratio test indicated that the freely estimated model was a significantly better fit to the data than the constrained model, we examined the magnitude of the parameter estimates to establish which was significantly greater.

For missing data, complete data rates for primary model variables were: 100% for age, SES, transactional sex, gay community connectedness, self-efficacy, TPB, and TRB; 99.6% for depressive symptoms and emotional awareness; 99.5% for anxiety symptoms; and 99.2% for positives, discrimination, and private regard. In line with the Mplus default, we used full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption that data were missing at random (MAR; Marcoulides & Schumacker, 1996). This assumption was tenable given there were no differences between participants with and without missing data across any study variables, and there was no reason to expect systematic differences in our dependent variables based on missingness patterns (Bhaskaran & Smeeth, 2014).

Results

Table 1 contains the demographic characteristics of the study sample. The majority of participants identified as gay, single, and were not living with HIV. Ages ranged from 16 to 67 years (M=30.29 SD= 9.45). Overall, this sample is younger, with more formal education, and higher formal employment, though lower income than other U.S. Black LGBTQ communities (Nationwide rates: Mage= 35.3; high school education or less= 49%; unemployment rate= 11%; income below 24k= 36%; LGBT Demographic Data Interactive, 2019). Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for observed variables in our final model.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 793 | 74.5 |

| Queer | 19 | 1.8 |

| Bisexual | 252 | 23.7 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 628 | 59.0 |

| Part-time | 237 | 22.3 |

| Student (unemployed) | 93 | 8.7 |

| Unemployed | 84 | 7.9 |

| On disability | 22 | 2.1 |

| Highest Educational Attainment | ||

| High School Diploma, GED, or less | 202 | 19.0 |

| Some College, Associate’s degree, or currently enrolled in college | 535 | 50.3 |

| 4-Year College Degree | 223 | 21.0 |

| Graduate School | 104 | 9.8 |

| HIV Status | ||

| Positive | 32 | 3.0 |

| Negative (confirmed) | 724 | 68.0 |

| Negative (unconfirmed) | 234 | 22.0 |

| Unknown | 74 | 7.0 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 830 | 78.0 |

| Partnered | 234 | 22.0 |

| Subjective Socioeconomic Status | ||

| 1–2 | 35 | 3.3 |

| 3–4 | 188 | 17.7 |

| 5–6 | 481 | 45.2 |

| 7–8 | 328 | 30.8 |

| 9–10 | 32 | 3.0 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 424 | 39.8 |

| $20,000 to $49,000 | 455 | 42.8 |

| $50,000 to $74,000 | 113 | 10.6 |

| $75,000 or more | 63 | 5.9 |

| M | SD | |

| Age (Range: 16–67, Mdn= 28) | 30.29 | 9.45 |

| Number of Transmission Protective Behaviors (Mdn= 0) | 1.96 | 7.37 |

| Number of Transmission Risk Behaviors (Mdn= 0) | 2.42 | 7.47 |

Note. Negative (confirmed) refers to those participants who self-reported a negative HIV status and tested negative. Negative (unconfirmed) refers to participants who reported a negative HIV status, but did not complete testing. Positive refers to participants who tested positive. Unknown refers to participants who self-reported Unknown and did not complete testing. The total n for income does not equal 100% because participants under 18 were not asked.

Table 2.

Descriptives and correlations among study variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positives: Black Men | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Microaggressions | .09** | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Overt Discrimination | .06* | .55*** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Self-Efficacy | .28*** | −.04 | −.05† | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Emotional Awareness | .23*** | −.07* | −.09** | .26*** | -- | |||||||

| 6. Depressive Symptoms | −.20*** | .26*** | .20*** | −.27*** | −.18*** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Anxiety Symptoms | −.17*** | .19*** | .23*** | −.21*** | −.11*** | .63*** | -- | |||||

| 8. TPB | −.03 | .05† | .10*** | −.05† | −.10* | .07* | .07* | -- | ||||

| 9. TRB | −.04 | .05† | .14*** | −.08* | −.10** | .08* | .04 | .45*** | -- | |||

| 10. Private Regard | .48*** | −.05 | −.16*** | .18*** | .23*** | −.25*** | −.23*** | −.03 | −.07* | -- | ||

| 11. Gay Community Connectedness | .23*** | −.11*** | −.11*** | .12*** | .15*** | −.19*** | −.12*** | −.05† | −.04 | .24*** | -- | |

| 12. Age | .07* | .00 | .08* | .06* | .08** | −.16*** | −.14*** | .04 | 13*** | .08* | −.02 | -- |

| Mean | 4.04 | 3.20 | 1.92 | 3.32 | 3.79 | 5.62 | .75 | 1.96 | 2.42 | 5.49 | 2.79 | 30.29 |

| SD | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.04 | .47 | 1.10 | 3.40 | .89 | 7.37 | 7.47 | 1.47 | .81 | 9.45 |

| Alpha | .75 | .86 | .89 | .89 | .84 | .85 | .90 | -- | -- | .78 | .92 | -- |

Note.

p≤ .001,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .10

TPB= Sexual protective behavior, TRB= Sexual risk behavior

All correlations are with observed scores. Private regard and gay community connectedness are control variables in the analyses depicted in Figure 1. The estimates presented are Pearson’s r with the exception of those for sexual behavior for which Spearman’s ρ is utilized due to the nonparametric nature of the count data.

For the latent variable CFAs, the self efficacy CFA indicated that a 10-item, 1-factor model fit the data well, χ2(35)= 149.46, p = .00, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .06. Consistent with past CFAs with this scale (Scholz, Doña, Sud, & Schwarzer, 2002), standardized factor loadings ranged from .46-.75. All other models were just-identified (3-indicator model) or under-identified (2-indicator model), therefore we report factor loadings and not model fit indices. For the positives CFA, standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.64 to 0.78. For the discrimination CFA, standardized factor loadings were high at 0.68 (microaggressions) and 0.82 (overt). For the psychological distress and emotional awareness CFAs, standardized factor loadings were 1.00 (anxiety) and 0.61 (depressive symptoms) and 0.84 (attentive) and 0.87 (care), respectively. For the private regard variable CFA, standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.51 to 0.88.

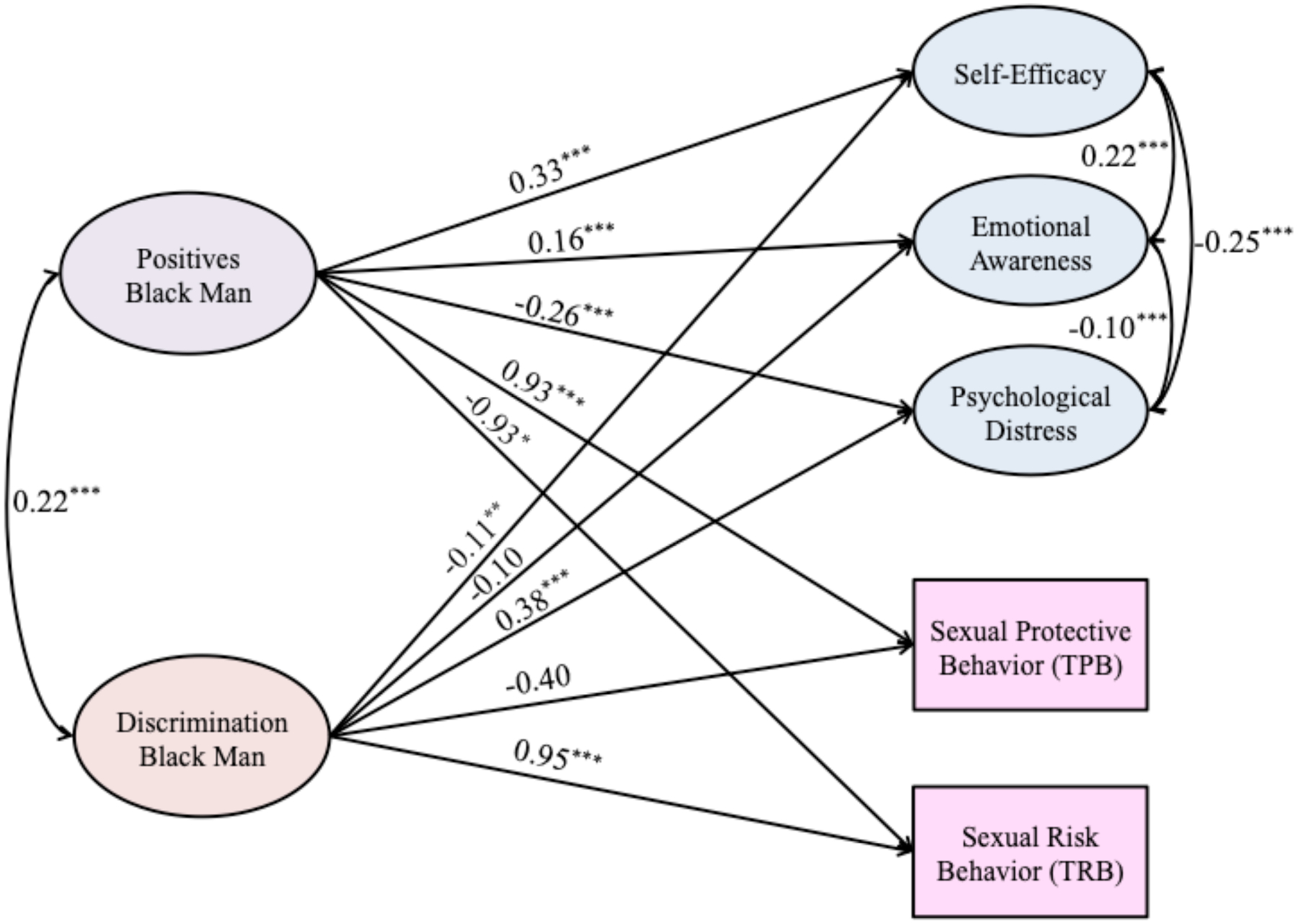

Figure 1 depicts the primary structural equation model. The discrimination latent variable was positively associated with psychological distress (b = 0.38, S.E. = 0.05, p < 0.001) and TRB (b = 0.95, S.E. = 0.19, p < 0.001). There was a significant negative association between discrimination and self-efficacy (b = −0.11, S.E. = 0.04, p < 0.01). There was not a significant association between discrimination and emotional awareness (b = −0.10, S.E. = 0.07, p = 0.15) or TPB (b = −0.40, S.E. = 0.209, p = 0.17). The positives subscale was negatively associated with psychological distress (b = −0.26, S.E. = 0.08, p = 0.001) and TRB (b = −0.93, S.E. = 0.40, p < 0.05) and positively associated with emotional awareness (b = 0.16, S.E. = 0.04, p < 0.001), TPB (b = 0.93, S.E. = 0.06, p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (b = 0.33, S.E. = 0.03, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model depicting associations between positives and discrimination associated with being a Black man and psychological and sexual risk and protective variables.

Note. *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001.

Sex variables are zero-inflated poisson distributed counts. This model is adjusted for racial/ethnic private regard, gay community connectedness, age, subjective SES, and history of transactional sex. Sex variables were offset by total count of sexual acts. Indicators of latent variables are not depicted in this figure.

Significant interactions are depicted in Figure 2. The interaction between positives and age was significantly associated with TRB (b = 0.02, S.E. = 0.01, p < 0.05). The plot shows the negative association between positives and TRB was significantly stronger for younger compared to older men. The interaction between positives and age was significantly associated with emotional awareness (b = 0.004, S.E. = 0.001, p < 0.01). The plot shows the positive association between positives and emotional awareness was significantly stronger for older compared to younger men. The interaction between discrimination and age was significantly associated with emotional awareness (b = 0.01, S.E. = 0.002, p = 0.01). The plot shows the negative association between discrimination and emotional awareness was significantly stronger for younger compared to older men. The interaction between discrimination and age was significantly associated with TPB (b = 0.05, S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.01). The plot shows the negative association between discrimination and TPB was significantly stronger for younger compared to older men. No other interactions were significant.

Figure 2.

Graphs depicting significant interaction between positives and discrimination associated with being a Black man, age, and psychological and sexual risk and protective variables.

The log-likelihood difference between the free model and the model with the psychological distress pathways constrained to be equal was not significant, D = 3.78, df = 1, p > 0.052, indicating that the discrimination and positives pathways were not significantly different. The log-likelihood difference value between the free model and the self-efficacy constrained model was significant, D = 14.24, df = 1, p < 0.001, indicating that the positives pathway was stronger than that of discrimination. The log-likelihood difference value between the free model and the TRB constrained model was significant, D = 56.15, df = 1, p < 0.001, indicating that the discrimination path was stronger than that of the positives subscale. The pathways from discrimination to emotional awareness and TPB were not significant, indicating that we could not be certain that the values were anything other than 0. Since the positives pathways were significantly different than 0, we concluded that the positives pathways were stronger.

Discussion

Despite the need for interventions tailored to promote the health of Black SMM (Malebranche, 2018; Malebranche & Bowleg, 2013), there is little research that examines associations between their positive and negative intersectional experiences and their psychological and sexual health (AmFar, 2015). The present study provides evidence for associations between discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man and psychological and sexual health indicators among Black SMM. Our results showed that greater positive feelings about being a Black man was positively associated with self-efficacy, emotional awareness, and sexual protective behavior; and negatively associated with psychological distress and sexual risk behavior for Black SMM. Except for emotional awareness and sexual protective behavior, discrimination experiences as a Black man were also associated with these variables, though to a lesser magnitude for positive health indicators. Moderation analyses showed that younger men generally had stronger associations between discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man and these health indicators than older men. Our results suggest that positive feelings, in addition to discrimination, at the intersection of race and gender play an important role in the psychological and sexual health of Black SMM, particularly for younger men.

The associations between discrimination at the intersection of race and gender among Black SMM and psychological and sexual risk/protective factors are consistent with past minority stress research that evinces the negative health impacts of discrimination (Arnold et al., 2014; Beasley et al., 2015). Our results expand upon these previous findings to suggest that experiences specifically associated with being a Black man may be critical for the psychological and sexual wellbeing of Black SMM. As such, the present findings highlight the value of not just examining discrimination targeting individual social positions, but also discrimination at the intersection of race and gender for Black SMM.

The present results are the first of their kind, to our knowledge, to quantitatively show positive associations between positive feelings at the intersection of race and gender among Black SMM and their psychological and sexual health. These results expand upon past research showing that positive components of racial and sexual identity can be protective for Black SMM (Crawford et al., 2002), and suggest the importance of examining positive feelings and experiences associated with being a Black man, specifically. Critically, our analyses adjusted for ethnic/racial private regard, suggesting there are positive feelings at the intersection of race and gender for Black SMM that are unique from racial/ethnic identity alone. These results are novel given the majority of research examining psychological and sexual health among Black SMM takes a deficits-focus (Matthews, Smith, Brown, & Malebranche, 2016; Reed & Miller, 2016). That is, studies have predominantly examined individual-level risk for HIV, rather than the social processes (e.g., discrimination, positive experiences) that target social position and affect their strengths and supports (see Hermanstyne et al., 2018; Teti et al., 2012 for exceptions). Our results even show that positive feelings about being a Black man had stronger associations with positive psychological and sexual health indicators than discrimination. Thus, examining positives at the intersection of race and gender may be critical to future health promotion research with Black SMM.

Moderation analyses indicated that the associations between discrimination and positive feelings as a Black man and psychological and sexual health indicators were generally more pronounced for younger than older participants. These results provide support for research that suggests younger Black SMM, who are the most likely to be engaging in social identity exploration, may be the most affected by messages targeting their social identities (Strayhorn & Tillman-Kelly, 2013; Yip, 2018). The one exception we found to this was that older Black SMM had a stronger association between positive feelings about being a Black man and emotional awareness than younger men. This may have been the case because older men may tend to engage in more emotional exploration than their younger counterparts (Lewis, Haviland-Jones, & Barrett, 2010) and, as such, be primed to experience increases in their emotional awareness as a result of positive experiences and/or feelings as a Black man.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Regarding strengths, the present study included a large national sample of Black SMM. This study is also among the first to examine positive sexual and psychological correlates with experiences linked to the intersection of race and gender among Black SMM. Thus, this study provides important support for the pursuit of strengths-based research among Black SMM. These study strengths, however, must be considered in the context of our study’s weaknesses.

First, the response rate among individuals who screened eligible for the survey was low (36%) and the demographics of our participants were not entirely representative of Black LGBTQ communities in the U.S. Thus, our results may reflect how discrimination and positives about being a Black man may operate for relatively younger Black SMM with more formal education and employment, but lower income. Additionally, because we used cross-sectional data, our analyses could not incorporate temporal precedence between independent and dependent variables, meaning we were unable to establish the directionality of our associations. In addition, we relied on self-report data for both independent and dependent variables, which can risk a common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Our measure of positive feelings associated with being a Black man was also limited because it consists of only three items, which likely capture only a fraction of the range of positive intersectional feelings/experiences of our participants. Since we found relatively robust associations, even with these limitations, future researchers may be encouraged to expand upon our measurement of these positives among Black SMM. Another limitation of the present study was that we exclusively examined sexual risk and protection in the context of casual partners, which only accounts for a portion of sexual risk among SMM (Sullivan, Salazar, Buchbinder, & Sanchez, 2009). Similarly, regarding the sexual HIV risk variable, we were unable to adjust for participants’ partners’ viral suppression at the time of sex, which may confer no HIV risk (Eisinger, Dieffenbach, & Facui, 2019).

There are several future directions for this research. First, the model presented in this manuscript should be examined longitudinally with a representative sample and test for temporal precedence between the independent and dependent variables. Such a study could also examine the nature of associations between the discrimination and positive feelings variables since we found positive correlations between these constructs. Additionally, although we only examined the present model with respect to discrimination and positive feelings about being a Black man, it is likely that similar patterns are occurring among people at different sociodemographic intersectional positions (e.g., Black transwomen). It will be vital to investigate both positive and discriminatory experiences across the intersections of different Black sexual and gender identities, while incorporating sociostructural variables (e.g., state and local-level policies).

In all, the present study sought to answer calls from public health and HIV experts to examine both protective and proactive, as well as vulnerable and risky, aspects of psychological and sexual health among Black SMM (e.g., Malebranche, 2018). Our results suggest that positive feelings and discrimination Black SMM experience at the intersection of their race and gender are associated with key psychological and sexual health indicators. Additional research is needed to assess if health programs may most effectively serve Black SMM when they identify and focus on intersectional resilience and prevention, along with vulnerability and risk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants who volunteered their time, without whom this study would not have been possible. We would like to thank all the staff, students, and volunteers who made this study possible, particularly those who worked closely on the study: Trinae Adebayo, Juan Castiblanco, Jorge Cienfuegos Szalay, Nicola Forbes, Ruben Jimenez, Scott Jones, Jonathan López Matos, Nico Tavella, and Brian Salfas. We would also like to thank our collaborators, Drs. Carlos Rodriguez-Díaz and Brian Mustanski. This study was supported by research grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, and National Institute on Mental Health (UG3-AI133674, PI: Rendina; K01-MH118091, PI: English) and we are grateful for the work of the NIH staff who supported these grants, particularly Drs. Gerald Sharp, Sonia Lee, Michael Stirratt, and Gregory Greenwood. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adler NE, & Stewart J (2007) The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php.

- American Psychological Association, APA Working Group on Health Disparities in Boys and Men. (2018). Health disparities in racial/ethnic and sexual minority boys and men. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/race-sexuality-men.aspx

- Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, & Kegeles SM (2014). ‘Triply cursed’: Racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(6), 710–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JR, Fergus TA, & Orcutt HK (2012). An examination of the latent structure of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(3), 382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley CR, Jenkins RA, & Valenti M (2015). Special section on LGBT resilience across cultures: Introduction. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55 (1–2), 164–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran K, & Smeeth L (2014). What is the difference between missing completely at random and missing at random? International Journal of epidemiology, 43(4), 1336–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2008). When Black+ lesbian+ woman≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59(5–6), 312–325. 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, English D, del Rio-Gonzalez AM, Burkholder GJ, Teti M, & Tschann JM (2016). Measuring the pros and cons of what it means to be a Black man: Development and validation of the Black Men’s Experiences Scale (BMES). Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(2), 177.754–767. Doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM, Kelly BC, Easterbrook A, & Parsons JT (2011). Community and drug use among gay men: The role of neighborhoods and networks. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(1), 74–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018a). HIV and African American Gay and Bisexual Men. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018b). Effective interventions. Retrieved from: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/hiv-negative-persons/group-1/many-men-many-voices/resources-implementation-tools---many-men-many-voices

- Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, & Kaufman AS (2004). Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychological Assessment, 16(4), 360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1995). Symposium: On West and Fenstermaker’s “Doing difference”. Gender & Society, 9, 491–513. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1998). It’s all in the family: Intersections of gender, race, and nation. Hypatia, 13, 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, … & Chasse V (2001). Measures of ethnicity-related stress: Psychometric properties, ethnic group differences, and associations with well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(9), 1775–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, & Soto T (2002). The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research, 39(3), 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JN, Kliewer W, & Garner PW (2009). Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 261–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, & Fauci AS (2019). HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection: Undetectable equals untransmittable. JAMA. 321(5), 451–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Rendina HJ, & Parsons JT (2018). The effects of intersecting stigma: A longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 669–679. doi: 10.1037/vio0000218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ, Jackson JS (1990). Factors contributing to positive mental health among Black Americans In: Ruiz DS; Comer JP, editors. Handbook of mental health and mental disorder among Black Americans. New York: Greenwood Press, p. 291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard C, Klein AG, Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Gäde J, & Brandt H (2015). On the performance of likelihood-based difference tests in nonlinear structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(2), 276 [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9102-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP, Banks KH, & Mattis JS (2006). Masculinity ideology and forgiveness of racial discrimination among African American men: Direct and interactive relationships. Sex Roles, 55(9–10), 679–692. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RL, Gullotta, Crowel RL (2010). Well-being and resilience: Another look at African American psychology In Handbook of African American Health (pp. 106–120) New York, NY: Guildord. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanstyne KA, Green HD Jr, Cook R, Tieu HV, Dyer TV, Hucks-Ortiz C, Wilton L, Latkin C, & Shoptaw S (2018). Social network support and decreased risk of seroconversion in black MSM: Results of the BROTHERS (HPTN 061) study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 78(2), 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, & Barrett LF (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of Emotions. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- LGBT Demographic Data Interactive (January 2019). Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska A, Scholz U, & Schwarzer R (2005). The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. The Journal of psychology, 139(5), 439–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, (2018). Making the treatment cascade work in vulnerable and key populations. Plenary presentation at the 22nd Annual International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, & Bowleg L (2013). So much more than gay, bisexual or DL: Investigating the structural determinants of sexual HIV risk among Black men in the United States Social determinants of health among African American men. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Fields EL, Bryant LO, & Harper SR (2009). Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men and Masculinities, 12(1), 90–112. doi: 10.1177/1097184X07309504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoulides GA, & Schumacker RE (1996). Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DD, Smith JC, Brown AL, & Malebranche DJ (2016). Reconciling epidemiology and social justice in the public health discourse around the sexual networks of Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 808–814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, & Holtgrave D (2014). HIV among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: A review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior, 18(1), 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall L (2008). The complexity of intersectionality. In Intersectionality and beyond (pp. 65–92). Routledge-Cavendish. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KM, Carey MP, & Fisher CB (2019). Is guardian permission a barrier to online sexual health research among adolescent males interested in sex with males?. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 593–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okech AP, & Harrington R (2002). The relationships among Black consciousness, self-esteem, and academic self-efficacy in African American men. The Journal of Psychology, 136(2), 214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, & Podsakoff NP (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SJ, Miller RL (2016). Thriving and adapting: resilience, sense of community, and syndemics among young Black gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(1–2), 129–143. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KW (2013). Understanding the relationships among racial identity, self-efficacy, institutional integration and academic achievement of Black males attending research universities. The Journal of Negro Education, 82(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Gamarel KE, Pachankis JE, Ventuneac A, Grov C, & Parsons JT (2016). Extending the minority stress model to incorporate HIV-positive gay and bisexual men’s experiences: A longitudinal examination of mental health and sexual risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 147–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, Grov C, & Parsons JT (2015). Aggregate and event-level associations between substance use and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: Comparing retrospective and prospective data. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, & Reid H (1996). Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(2), 136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg ES, Millett GA, Sullivan PS, del Rio C, & Curran JW (2014). Understanding the HIV disparities between black and white men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: A modeling study. The Lancet HIV, 1(3), e112–e118. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, & Fish JN (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz U, Doña BG, Sud S, & Schwarzer R (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, & Jerusalem M (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. Measures in Health Psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs, 1(1), 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwing AE, Wong YJ, & Fann MD (2013). Development and validation of the African American Men’s Gendered Racism Stress Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Steensma TD, Kreukels BP, de Vries AL, & Cohen-Kettenis PT (2013). Gender identity development in adolescence. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn TL, & Tillman-Kelly DL (2013). Queering masculinity: Manhood and Black gay men in college. Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men, 1(2), 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, & Sanchez TH (2009). Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS, 23(9), 1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Martin AE, Ranade R, Massie J, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM, & Bowleg L (2012). “I’ma keep rising. I’ma keep going forward, regardless” Exploring Black men’s resilience amid sociostructural challenges and stressors. Qualitative Health Research, 22(4), 524–533. doi:22:524–533.10.1177/1049732311422051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Foundation for AIDS Research (AmFar) (2015). HIV and the Black community: Do“#Black(GAY) lives matter?” Retrieved from https://www.amfar.org/uploadedFiles/_amfarorg/Articles/On_The_Hill/2016/Black-Gay-Men-and-HIV.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, … & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2018) Global AIDS monitoring: Indicators for monitoring the 2017 United Nations Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Wade RM, & Harper GW (2017). Young Black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men: A review and content analysis of health-focused research between 1988 and 2013. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1388–1405. doi: 10.1177/1557988315606962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T (2018). Ethnic/racial identity—A double-edged sword? Associations with discrimination and psychological outcomes. Current directions in psychological science, 27(3),170–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]