Abstract

Unlike sensory thalamus, studies on the functional organization of midline and intralaminar nuclei are scarce, and this has hampered the establishment of conceptual models on the function of this brain region. We have investigated the functional organization of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), a midline thalamic structure increasingly being recognized as a critical node in the control of diverse processes such as arousal, stress, emotional memory and motivation, in mice. We identify two major classes of PVT neurons – termed Type I and Type II – that differ in terms of gene expression, anatomy and function. In addition, we demonstrate that Type II neurons belong to a previously neglected class of PVT neurons that conveys arousal-related information to corticothalamic neurons of the infralimbic cortex. Our results uncover the existence of an arousal-modulated thalamo-corticothalamic loop that links the PVT and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Keywords: Paraventricular thalamus, arousal, infralimbic cortex, salience encoding

INTRODUCTION

Functional correlates of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) include roles in diverse processes such as arousal, emotional valence, internal physiological state and associative memory1–7. These correlates coincide with the notion that the PVT is a site of convergence for reticular and hypothalamic inputs and embedded in corticolimbic and corticostriatal circuits emerging from the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)8. As a result of this anatomical and functional complexity, interest has been placed in identifying whether the PVT is organized into discrete functional subregions. However, while early studies recognized the existence of anterior and posterior divisions of the PVT9,10, investigations into whether these represent functionally distinct subregions have yielded conflicting results7,11–13. Much of this is likely due to a loose definition of the boundaries that separate the anterior and the posterior parts of the PVT (aPVT and pPVT, respectively), as well as a failure to recognize the existence of a transitional middle region8. In particular, studies focused on the aPVT (from Bregma: −0.8 mm in rats and −0.2mm in mice) have traditionally targeted antero-posterior coordinates that can be considered medial PVT7,11,14. Others do not distinguish between the aPVT and pPVT, further complicating matters4,15. Together, this highlights the necessity of a systematic investigation of how functionally distinct neuronal subtypes are organized in the PVT.

Classification of neuronal subtypes have remained a major theme in neurobiology for over a century. Despite early technical barriers, substantial developments in genetic and molecular techniques have provided a means to categorize and target diverse neuronal subtypes16. These types are traditionally defined on the bases of their physiological, anatomical, and molecular (genetic) properties. Based on these criteria, the parallel development of transgenic lines and sophisticated viral techniques have conferred repeated access to a wide range of neuronal subpopulations defined from a molecular and connectional perspective. As a result, these tools have improved our ability to delineate the contributions of specific neuronal subtypes to discrete brain processes. Following this approach, here we combine molecular, anatomical, and functional criteria in mice to define two neuronal subtypes that are distributed along opposite antero-posterior PVT gradients, namely Type I and Type II PVT neurons. Specifically, while Type I neurons are largely restricted to the pPVT and collectively signal aversive states, Type II neurons predominate in the aPVT and are modulated by arousal. Our results confirm the existence of two functionally distinct PVT subregions. In addition, our observation that Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT are not restricted to specific antero-posterior locations but are rather biased to opposite ends of a gradient proposes that the current nomenclature used to define distinct regions of the PVT (i.e. aPVT and pPVT) must be revised.

RESULTS

Two major neuronal subtypes are distributed along the antero-posterior axis of the PVT

To assess whether functionally-distinct classes of neurons exist along the antero-posterior axis of the PVT, we investigated the spatial and functional properties of genetically-identified neurons in this brain region – since genetic markers commonly serve to categorize neuronal subtypes16. Specifically, because of the known enrichment of dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs) in the midline thalamus of both humans and mice17–19, we contrasted PVT neurons that differed in their expression of the Drd2 gene. In agreement with earlier reports19, in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments using RNAScope demonstrated robust expression of the Drd2 gene in the posterior PVT (pPVT) of wildtype mice (Fig. 1a–c). In addition, these experiments revealed a significant decrease in both the density of Drd2-positive cells as well as the number of Drd2 transcripts per cell in anterior regions of the PVT (Fig. 1b, c). These findings indicate that the antero-posterior axis of the PVT is composed of neuronal subpopulations that are spatially and genetically diverse.

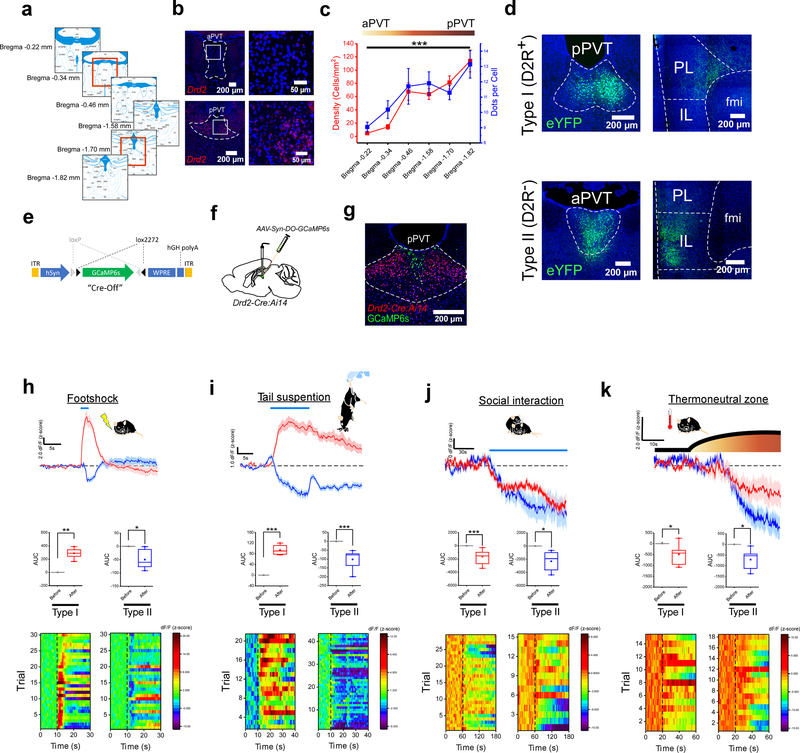

Figure 1. Functionally distinct cell types exist across the antero-posterior axis of the PVT.

a. Schematic of the antero-posterior spread of the PVT in the adult mouse brain and the Bregma locations included in our analyses of Drd2 expression. Red squares depict the Bregma locations of the representative images shown in b for aPVT and pPVT. b. Fluorescent in situ hybridization experiment showing the expression of the Drd2 gene in the aPVT (top) and the pPVT (bottom). c. Quantification of the cellular density (red) and relative expression levels (blue) of Drd2 mRNA across the antero-posterior axis of the PVT. n = 5 mice, F(5,21) = 19.64, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Bregma −0.22 vs Bregma −1.82, ***P=0.000007. d. Representative images showing the distribution of axonal projections from D2R+ (top panels) and D2R− (bottom panels) neurons of the PVT in the mPFC (data from 3 mice). e. Diagram of the vector used to target expression of the genetically-encoded Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6s to D2R− neurons of the PVT. f. Schematic of the stereotaxic injection to selectively target expression of GCaMP6s to D2R− neurons of the PVT. g. Representative image showing expression of GCaMP6s in D2R− neurons of the PVT of Drd2-Cre:Ai14 mice. h. Top: average GCaMP6s responses to footshocks from both Type I (red) and Type II neurons (blue) of the PVT (n = 7 mice). Footshock duration depicted by the blue line above the trace. Middle: quantification of GCaMP6s responses to footshocks (shown as z-score of dF/F). Area under the curve (AUC), Type I: Before, −0.27 ± 0.25; After, 302.5 ± 46.03, n = 7 mice, **P=0.0012, two-sided Paired sample t-test; Type II: Before, 0.10 ± 0.13; After, −50.05 ± 14.95, n = 6 mice, *P=0.02, two-sided Paired sample t-test. Bottom: heatmap of dF/F for all individual trials. i. Top: average GCaMP6s responses to tail suspension from both Type I (red) and Type II neurons (blue) of the PVT (n = 8 mice). The duration of the tail suspension bouts is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Middle: quantification of GCaMP6s responses to tail suspension. AUC, Type I: Before, 0.012 ± 0.01; After, 94.25 ± 10.18, n = 4 mice, **P=0.002, two-sided Paired sample t-test; Type II: Before, −0.26 ± 0.25; After, −102.5 ± 17.78, n = 8 mice, ***P=0.0007, two-sided Paired sample t-test. Bottom: heatmap of dF/F for all individual trials. j. Top: average GCaMP6s responses to social interaction from both Type I (red) and Type II neurons (blue) of the PVT. The duration of the interaction bouts is depicted by the blue line above the trace (n = 5 mice). Middle: quantification of GCaMP6s responses to social interaction. AUC, Type I: Before, 0.78 ± 0.18; After, −1647.62 ± 294.40, n = 7 mice, ***P=0.0002, two-sided Paired sample t-test; Type II: Before, 1.11 ± 1.50; After, −2316.92 ± 726.56, n = 5 mice, *P=0.033, two-sided Paired sample t-test. Bottom: heatmap of dF/F for all individual trials. k. Top: average GCaMP6s responses to the thermoneutral zone from both Type I (red) and Type II neurons (blue) of the PVT (n = 5 mice). The duration of thermoneutral zone exposure is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Middle: quantification of GCaMP6s responses to the thermoneutral zone. AUC, Type I: Before, 9.69 ± 9.54; After, −495.25 ± 198.34, n = 5 mice, *P=0.046, two-sided Paired sample t-test; Type II: Before, −0.11 ± 0.44; After, −711.94 ± 236.33, n = 6 mice, *P=0.039, two-sided Paired sample t-test. Bottom: heatmap of dF/F for all individual trials. Box chart legend: box is defined by 25th, 75th percentiles, whiskers are determined by 5th and 95th percentiles, and mean is depicted by the square symbol. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

To explore this diversity further, we first sought to investigate the anatomical distribution of efferent projections from D2R+ and D2R− neurons of the PVT. We achieved this by first injecting the PVT of Drd2-Cre mice with AAV vectors in which ChR2-eYFP expression is controlled via either Cre recombinase-mediated transcriptional activation (CreON) or inactivation (CreOFF) (Extended Data Fig. 1). Next, we investigated the anatomical projections of D2R+ and D2R− PVT neurons, hereinafter referred to as Type I and Type II PVT neurons, respectively. Consistent with previous studies8, we observed that the major targets of the PVT included the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the amygdala (Fig. 1d; Extended Data Fig. 2). However, careful assessment of the projections arising selectively from either Type I or Type II neurons of the PVT revealed that these were segregated within each of their target nuclei (Extended Data Fig. 2). For instance, while Type I neurons innervate the core and ventral shell of the NAc, Type II neurons preferentially target the dorsomedial portion of the shell. Similarly, Type I neurons innervate the prelimbic (PL) region of the mPFC, whereas Type II neurons mainly target the infralimbic area (IL; Fig. 1d; Extended Data Fig. 2). Importantly, the differential pattern of innervation produced by these two classes of PVT neurons appears to be irrespective of their antero-posterior location, highlighting the power of genetic markers as classifiers of neuronal subtypes (Extended Data Fig. 2b, c). Altogether, these findings suggest that Type I and Type II neurons may represent functionally distinct classes of PVT cells.

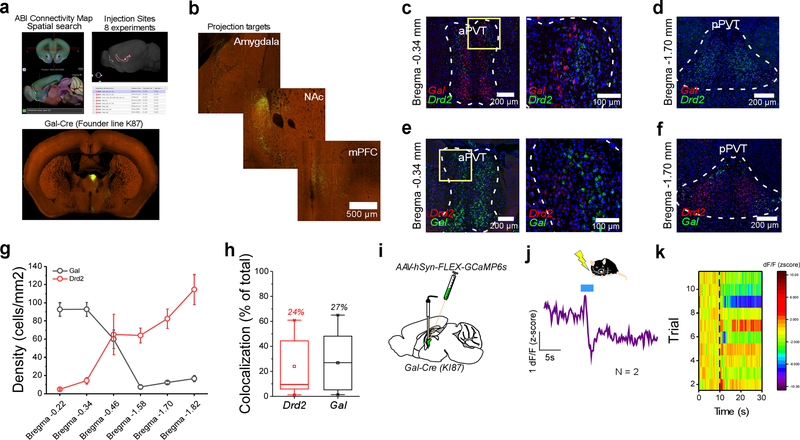

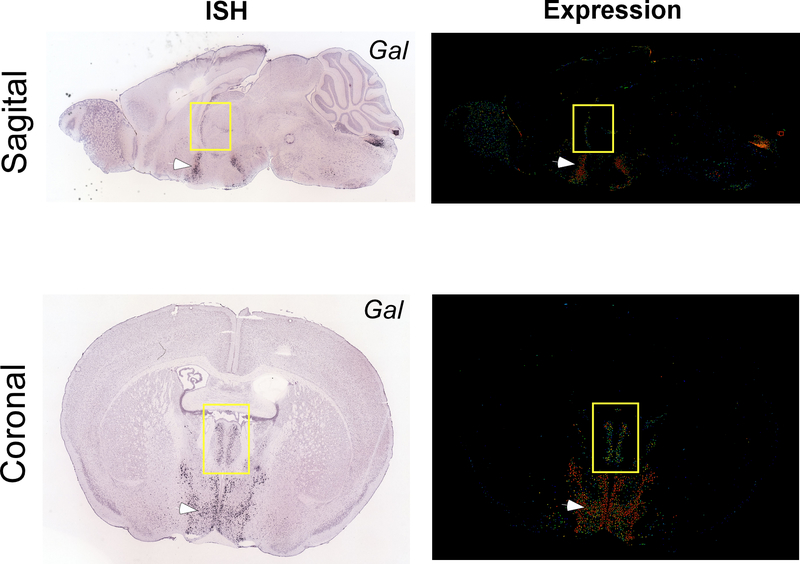

Galanin is a marker of Type II PVT neurons

Our observation that Type II PVT neurons can be distinguished based on their lack of Drd2 expression prompted us to investigate whether other known genetic markers could serve to identify this neuronal subclass. To achieve this, we utilized the Spatial Search tool on the Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas of the Allen Brain Institute (http://connectivity.brain-map.org) to identify experiments in which anatomical projections from the PVT to the IL were identified – since Type II but not Type I neurons of the PVT project to the IL (Extended Data Fig. 3). This search yielded 8 connectivity experiments, 7 of which used Cre lines to target PVT neurons (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The genes associated with these Cre lines were the following: Ppp1r17, Grm2, Gal, Lypd6, Efr3a, Calb2 and Ntrk1. To select putative Type II genetic markers from this list, we employed an additional connectional criteria of Type II neurons: selective innervation of the dorsomedial shell of the NAc (Extended Data Fig. 2). Of these, only the connectivity experiments using Ppp1r17-Cre and Gal-Cre mice satisfied these criteria (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b), suggesting that Ppp1r17 and Gal (Galanin) could be genetic markers of Type II PVT neurons. However, because for both experiments rostral regions of the aPVT were targeted, the pattern of anatomical projections from these classes of neurons could be due to regional differences and not genetic ones. To disentangle this possibility, we again used the Mouse Brain atlas of the Allen Brain Institute to probe the distribution of these two genes in the PVT. Interestingly, while Ppp1r17 expression was similarly distributed across the antero-posterior axis of the PVT, Gal expression was dense in the aPVT but sparse in the pPVT, indicating that it could be a genetic marker of Type II PVT neurons. To directly assess this possibility, we performed multiplexed RNAScope experiments to contrast the antero-posterior distribution of Gal mRNA with that of Drd2 in the PVT (Extended Data Fig. 3c–h). In contrast to Drd2 mRNA, Gal mRNA was most abundant in the aPVT and only mildly present in the pPVT (Extended Data Fig. 3c–g). Importantly, co-expression of both transcripts was only observed in a small fraction of neurons (Extended Data Fig. 3h), indicating that Gal serves as a selective genetic marker for Type II PVT neurons.

Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT respond differentially to salient stimuli

To test the prediction that Type I and Type II neurons represent functionally distinct classes of PVT cells, we selectively targeted the expression of the genetically-encoded calcium sensor GCaMP6s to either neuronal subtype of the PVT and assessed their population response to salient stimuli of opposite valence using fiber photometry (Figure 1e–k). Genetic access to Type I PVT neurons was achieved using Cre-mediated expression of GCaMP6s in Drd2-Cre mice. To gain genetic access to Type II PVT cells, attempts were initially made using Gal-Cre lines20,21 in combination with AAV vectors driving Cre-dependent expression of GCaMP6s. However, despite the robust expression of Gal mRNA in Type II PVT neurons (Extended Data Fig. 3c–h), attempts to drive GCaMP6s expression in Gal-positive neurons of the PVT of Gal-Cre mice mostly failed, with sparse GCaMP6s expression achieved in only a few animals (Extended Data Fig. 3i–k). Therefore, for the remainder of our study, genetic access to the Type II population was achieved by employing the CreOFF approach in Drd2-Cre mice described above (Fig. 1e–g; Extended Data Fig. 1). In agreement with a recent report from our group19, in vivo recordings of calcium transients from Type I neurons of the PVT showed that two independent aversive stimuli (footshock and tail suspension) promote the activity of this neuronal population (Fig. 1h, i). In contrast, stimuli reported to be rewarding for mice such as access to a female conspecific (for male mice)22 or a thermoneutral zone23, were associated with decreases in fluorescent signal in the same group of cells (Fig. 1j, k). These findings demonstrate that, at the population level, Type I neurons of the PVT are sensitive to the valence of salient stimuli. Next, we investigated the impact of aversive and rewarding stimuli on the activity of the Type II neuronal population. Unlike Type I PVT neurons, Type II neurons were inhibited by both classes of stimuli, suggesting that – at the population level – these neurons respond to stimulus salience irrespective of valence (Fig. 1h–k). Collectively, these results support the idea that functionally distinct streams of information co-exist in a single midline thalamic nucleus.

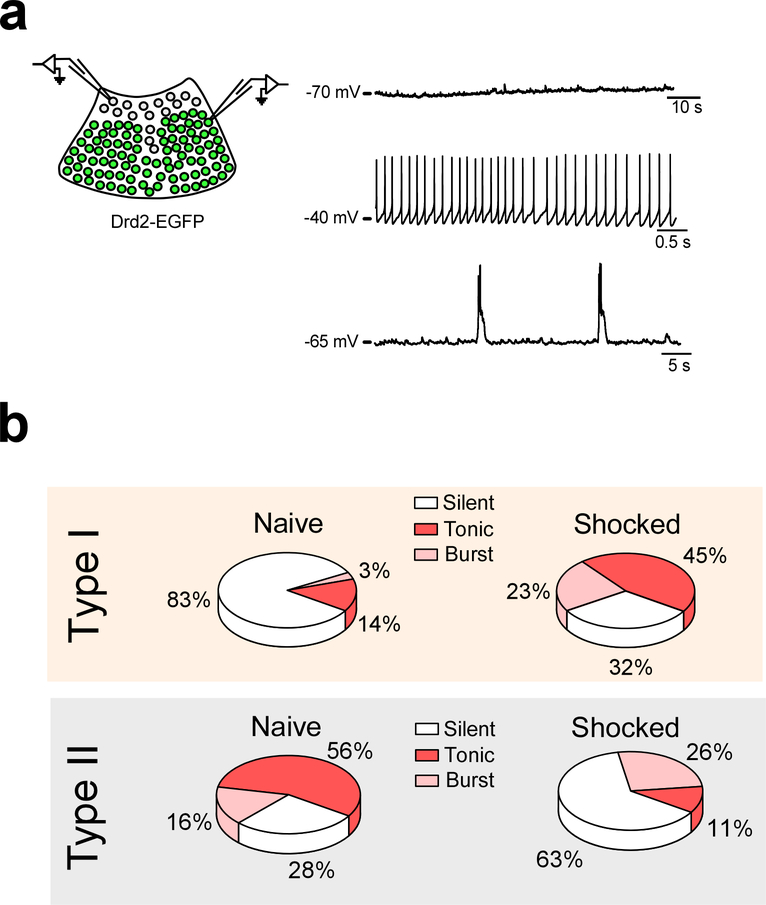

Despite the lack of a formal definition of functionally distinct regions, the presence of different classes of PVT neurons can be broadly inferred from the literature. Indeed, previous reports have demonstrated that PVT neurons can both increase and decrease their spontaneous firing rates following aversive experiences6,15. Since our newly defined subpopulations respond differentially to aversive experiences, we sought to investigate whether the bidirectional changes in spontaneous firing observed following aversive stimuli could segregate to Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT. Towards this goal, we performed ex vivo current clamp recordings from Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT of Drd2-Cre mice two hours after a footshock stimulation protocol (See Methods) and contrasted the proportion of spontaneously active neurons from each type with those of naïve subjects. First, in naïve mice, we observed that the proportion of spontaneously active neurons across PVT subtypes was disparate, with most Type I neurons in quiescent state and most Type II neurons displaying either tonic or burst firing (Extended Data Fig. 4). Next, we investigated whether footshock stimulation affected the proportion of spontaneously active neurons across both PVT subtypes. In agreement, we found that footshock stimulation led to a prominent increase in the proportion of spontaneously active Type I neurons and a concomitant decrease in the proportion of spontaneously active Type II neurons (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Collectively, these results suggest that neurons within the PVT that segregate into Type I and Type II exhibit bidirectional changes in neuronal firing in response to an aversive stimulus. These observations lend further support to our finding that Type I neurons are activated, while Type II neurons are inhibited by aversive stimuli (Fig. 1).

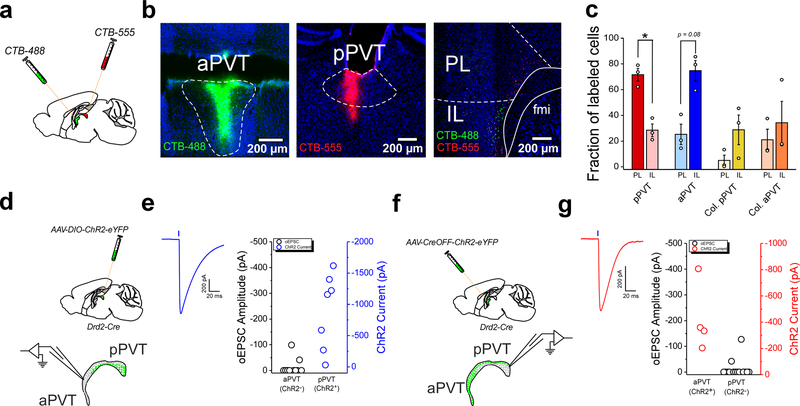

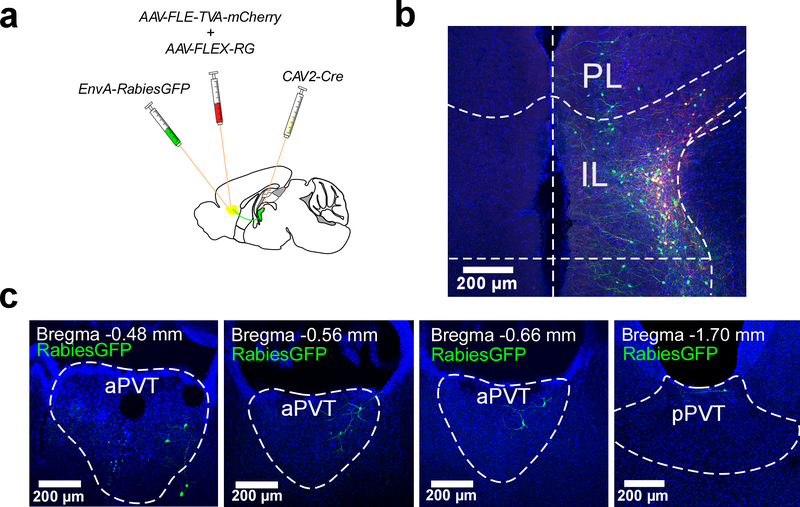

Independent thalamo-corticothalamic loops run through the PVT

Thalamo-corticothalamic loops are prominent in the mammalian brain and thought to support the synchronization of cortical and thalamic activity that underlies cognition and contributes to salience processing24,25. Based on their functional separation and because the PVT is reciprocally innervated by the mPFC26,27, we investigated whether Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT are embedded within discrete thalamo-corticothalamic loops. Towards this goal, we simultaneously labelled mPFC projections to either the aPVT (which contains mostly Type II neurons) or the pPVT (which contains mostly Type I neurons) of wildtype mice via injection of the retrograde tracers CTB-488 and CTB-555, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). Our findings demonstrated that while the PL mainly innervated the pPVT, the IL preferentially innervated the aPVT (Fig. 2b, c). In addition, monosynaptic tracings using a pseudo-typed rabies virus demonstrated that some PVT neurons synapse onto corticothalamic neurons of the IL (Extended Data Fig. 5). Together, these findings indicate that Type I and Type II neurons may be integrated into independent thalamo-corticothalamic loops. Consistent with this idea, patch clamp recordings in brain slices from Drd2-Cre mice demonstrated little to no connectivity between Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT (Fig. 2d–g).

Figure 2. Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT are integrated into independent thalamo-corticothalamic loops.

a. Schematic of the retrograde tracing strategy used to label mPFC neurons projecting to the most anterior and posterior regions of the PVT. b. Representative images showing the injection sites for CTB-488 and CTB-555 in the aPVT and pPVT, respectively. A representative image of the distribution of retrogradely-labeled cells in the mPFC is shown on the right. c. Quantification of the fraction of retrogradely labeled cells found in the PL and IL regions of the mPFC for each CTB injected subject. Fraction of labelled cells, pPVT: PL, 71.56 ± 4.595; IL, 28.44 ± 4.95, n = 3 mice, *P=0.049, two-sided Paired sample t-test; aPVT: PL, 25.25 ± 7.92; IL, 74.75 ± 8.58, n = 3 mice, P=0.08, two-sided Paired sample t-test. d. Schematic of the electrophysiology experiment to assess functional Type I to Type II connectivity in the PVT. A Cre-dependent AAV vector expressing ChR2-eYFP was injected in the PVT of Drd2-Cre mice. Acute slices containing the PVT were prepared 2–3 weeks after the injection. e. Left: sample trace showing optically-evoked responses in ChR2+ cells. Right: oEPSC (ChR2−; black open circles) and ChR2 current (blue open circles) amplitudes measured at −70 mV in the aPVT and the pPVT, respectively following light stimulation (5 ms light pulses). ChR2 currents were detected in all ChR2+ neurons probed (n = 7 neurons from 2 mice). oEPSCs were detected in only a small fraction of neurons (n = 2/10 from 2 mice). f. Schematic of the electrophysiology experiment to assess functional Type II to Type I connectivity in the PVT. A CreOFF AAV vector expressing ChR2-eYFP was injected in the PVT of Drd2-Cre mice. Acute slices containing the PVT were prepared 2–3 weeks after the injection. g. Left: sample trace showing optically-evoked responses in ChR2+ cells. Right: oEPSC (ChR2−; black open circles) and ChR2 current (red open circles) amplitudes measured at −70 mV in the pPVT and the aPVT, respectively following light stimulation (5 ms light pulses). ChR2 currents were detected in all ChR2+ neurons probed (n = 4 neurons from 2 mice). oEPSCs were detected in only a small fraction of neurons (n = 2/15 from 2 mice). Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

The PVT shapes cortical responses to salient stimuli

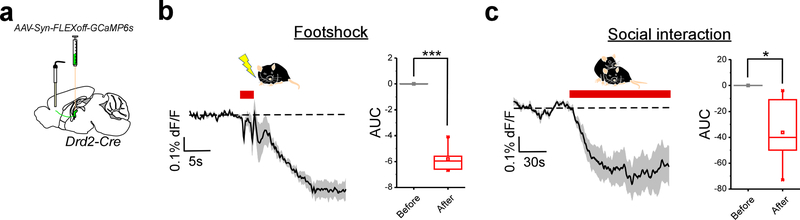

As described above, Type I neurons largely segregate to the pPVT. As such, the valence representation of this neuronal population is consistent with the notion that aversive experiences increase19, while rewarding experiences decrease neuronal activity in the pPVT28. In this regard, our assessment of this neuronal population serves to confer genetic and anatomical identity to an expected class of PVT neurons. Thus, for the remainder of our study, we focused our attention on investigating the function of the newly-defined salience-modulated Type II neuronal subtype of the PVT. To investigate whether Type II neurons of the PVT relay salience information to their downstream targets, particularly the mPFC, we recorded salient stimuli-evoked calcium transients from the axon terminals of these PVT neurons in the IL (Extended Data Fig. 6). Consistent with the responses seen in thalamic Type II cell bodies (Fig. 1h–k), both aversive and rewarding stimuli suppressed the activity of PVT terminals in the IL (Extended Data Fig. 6), thus providing evidence that the PVT relays salience information to the IL.

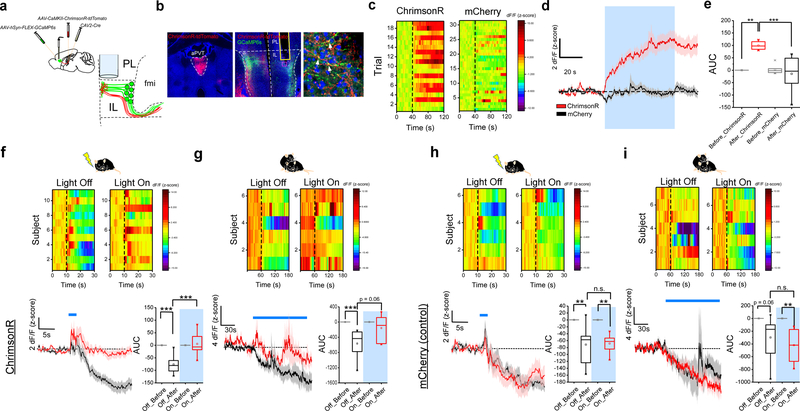

As demonstrated above, the IL selectively targets the aPVT, which contains most Type II neurons (Fig 2b, c). As such, we explored whether IL neuronal feedback projections to the PVT (ILPVT) mirrored the salience-evoked responses displayed by Type II thalamocortical projections. Towards this goal, we selectively expressed GCaMP6s in ILPVT neurons by first injecting the Cre-expressing canine adenovirus vector (CAV2-Cre) in the PVT of wildtype mice, and subsequently Cre-dependent GCaMP6s in the IL (Fig. 3a, b). Like the thalamocortical projections from Type II PVT neurons, ILPVT corticothalamic neurons displayed inhibitory responses to salient stimuli (Fig. 3f–i). As such, our results unveil the existence of a previously unidentified salience-responsive thalamo-corticothalamic loop linking the PVT and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Figure 3. PVT input shapes neuronal representations of salient stimuli in IL.

a. Schematic of the viral vector strategy and optical fiber placement used for combined fiber photometry imaging of GCaMP6s fluorescence from ILPVT neurons and optogenetic manipulation of the terminals of Type II PVT neurons in the IL. b. Representative images from a subject expressing ChrimsonR-tdTomato in the aPVT (left) and GCaMP6s in ILPVT neurons (middle). A high magnification image of a portion of the IL immediately below the tip of the optical fiber shows putative synaptic contacts (arrows) between the dendrites of GCaMP6s-expressing ILPVT neurons and tdTomato-labelled axons arising from the aPVT (right). c. Heatmap showing individual GCaMP6s responses to light stimulation (561 nm at 20 Hz) from both ChrimsonR- and mCherry-expressing (control) subjects. d. Average GCaMP6s responses from ILPVT neurons in ChrimsonR (red) and mCherry (black) expressing animals subjected to light stimulation, n = 6 mice per group. e. Quantification of light-evoked changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons. AUC: Before_ChrimsonR, −0.04 ± 0.01; After_ChrimsonR, 99.32 ± 7.13; Before_mCherry, 3.32 ± 7.95; After_mCherry, −14.45 ± 30.25, n = 6 mice per group; F(3,20) = 11.85, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Before_ChrimsonR vs After_ChrimsonR, **P=0.002; After_ChrimsonR vs After_mCherry, ***P=0.0004; Before_mCherry vs After_mCherry, P=0.86. f. Top: heatmap of average GCaMP6s responses to footshocks from individual ChrimsonR-expressing subjects. Bottom left: average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons in ChrimsonR-expressing animals subjected to footshocks in the presence (red) and absence (black) of light stimulation (561 nm at 20 Hz), n = 11 mice. Footshock duration is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Bottom right: quantification of footshock-evoked changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons in the presence and absence of light stimulation. AUC, Off_Before, −0.01 ± 0.06; Off_After, −76.45 ± 11.24; On_Before, 0.002 ± 0.05; On_After, 5.48 ± 12.84, n = 11 mice; F(3,40) = 21.12, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Off_Before vs Off_After, ***P=0.0000009; On_Before vs On_After, P=0.97; Off_After vs On_After, ***P=0.0000002. g. Top: heatmap of average GCaMP6s responses to social interaction from individual ChrimsonR-expressing subjects. Bottom left: average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons in ChrimsonR-expressing animals subjected to social interaction in the presence (red) and absence (black) of light stimulation (561 nm at 20 Hz), n = 6 mice. The duration of the interaction bouts is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Bottom right: quantification of social interaction-evoked changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons in the presence and absence of light stimulation. AUC, Off_Before, −0.02 ± 0.04; Off_After, −566.72 ± 162.67; On_Before, 0.10 ± 0.18; On_After, −158.58 ± 144.53, n = 6 mice; F(3,20) = 6.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Off_Before vs Off_After, **P=0.007; On_Before vs On_After, P=0.73; Off_After vs On_After, P=0.06. h. Top: heatmap of average GCaMP6s responses to footshocks from individual control subjects. Bottom left: average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons in mCherry-expressing control animals subjected to footshocks in the presence (red) and absence (black) of light stimulation, n = 6 mice. Footshock duration is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Bottom right: quantification of footshock-evoked changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons in the presence and absence of light stimulation. AUC, Off_Before, 0.08 ± 0.06; Off_After, −71.51 ± 24.82; On_Before, −0.07 ± 0.10; On_After, −68.5 ± 11.87, n = 6 mice; F(3,20) = 8.64, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Off_Before vs Off_After, **P=0.007; On_Before vs On_After, **P=0.01; Off_After vs On_After, P=0.99. i. Top: heatmap of average GCaMP6s responses to social interaction from individual control subjects. Bottom left: average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons in mCherry-expressing control animals subjected to social interaction in the presence (red) and absence (black) of light stimulation, n = 7 mice. The duration of the interaction bouts is depicted by the blue line above the trace. Bottom right: quantification of social interaction-evoked changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons in the presence and absence of light stimulation. AUC, Off_Before, 0.04 ± 0.04; Off_After, −299.29 ± 128.64; On_Before, −0.03 ± 0.02; On_After, −420.27 ± 96.02, n = 7 mice; F(3,24) = 7.07, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: Off_Before vs Off_After, P=0.06; On_Before vs On_After, **P=0.005; Off_After vs On_After, P=0.71. Box chart legend: box is defined by 25th, 75th percentiles, whiskers are determined by 5th and 95th percentiles, and mean is depicted by the square symbol. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Growing evidence ascribes an active role of the thalamus in integrating network information and shaping cortical activity29. To assess whether Type II thalamic innervation participates in shaping the activity of ILPVT neurons, we recorded the responses of ILPVT neurons to salient stimuli during optogenetic manipulations of PVT inputs using the red-shifted channelrhodopsin ChrimsonR30 (Fig. 3a, b). Given that Type II PVT projections to the IL are normally inhibited by salient stimuli (Extended Data Fig. 6), we reasoned that optogenetic excitation of these projections using ChrimsonR could serve to counteract the salience-driven inhibition observed in these neurons thereby impacting cortical representations. Consistent with this idea, light activation of thalamic input to the IL increased GCaMP6s fluorescence in ILPVT neurons (Fig. 3c–e). Notably, IL responses to aversive and rewarding stimuli were significantly attenuated during ‘light on’ trials, a result which was in stark contrast with the responses observed during ‘light off’ trials (Fig. 3f, g). Importantly, no such effects of light stimulation on GCaMP6s fluorescence were observed in animals injected with a control viral vector in the PVT (Fig. 3h, i). Finally, consistent with the idea that salient stimuli are accompanied by suppression of PVT–IL projections, optogenetic silencing of these projections during the presentation of salient stimuli did not affect cortical responses (Extended Data Fig. 7). Altogether, these results indicate that suppression of PVT inputs to the IL enable changes in cortical responses to salient stimuli, thus confirming that the PVT actively relays information about salience to the IL.

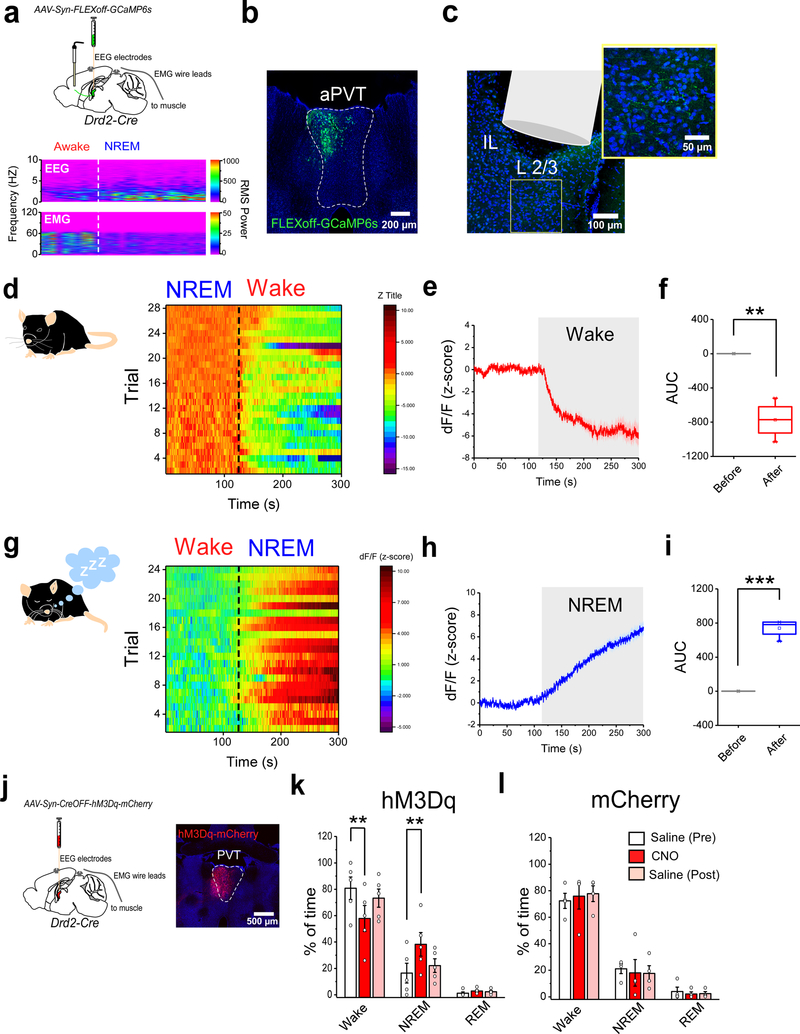

Activity in the PVT–IL loop is inversely related to arousal

Classically, the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei are thought to convey generalized arousal signals to the forebrain1. Within this context, the salience-induced negative modulation of the PVT–IL thalamo-corticothalamic loop may provide a means by which the PVT relays arousal-related information to its target structures. Thus, to investigate whether this thalamo-corticothalamic loop is modulated by arousal, we first recorded calcium transients from the IL terminals of Type II PVT neurons and simultaneously performed polysomnographic recordings to track sleep and wake states as correlates of low and high arousal, respectively (Fig. 4a–c). Our results showed that, non-REM (NREM)-Wake transitions were associated with prominent decreases, while Wake-NREM transitions yielded consistent increases in the activity of PVT–IL terminals (Fig. 4d–i). To investigate whether changes in arousal and the activity of Type II PVT neurons are causally related, we chemogenetically activated Type II neurons of the PVT in Drd2-Cre mice (Fig. 4j). Notably, chemogenetic activation of Type II neurons prior to the onset of the dark portion of the light-dark cycle was sufficient to decrease wakefulness and increase NREM sleep (Fig. 4k, l). Together, these findings demonstrate that the activity of Type II PVT neurons is causally related to arousal.

Figure 4. Type II neurons of the PVT signal arousal states.

a. Top: schematic of the viral vector strategy, optical fiber placement and EEG/EMG device implantation used for combined fiber photometry imaging of Type II PVT terminals in the IL and polysomnographic recordings. Bottom panel: sample EEG/EMG recording. Dashed lines depict state transitions between Awake and NREM sleep states. b. Representative image from a subject expressing GCaMP6s in Type II neurons within the aPVT. c. Representative image of the optical fiber placement in IL. A high magnification image of a portion of the IL immediately below the tip of the optical fiber showing GCaMP6s-expresing terminals. d. Heatmap showing individual GCaMP6s responses from Type II PVT terminals to NREM-Wake transitions for all subjects. e. Average GCaMP6s response from the terminals of Type II PVT neurons during NREM-Wake transitions (Wake depicted by shaded area), n = 4 mice. f. Quantification of GCaMP6s responses from the terminals of Type II PVT neurons for all NREM-Wake transitions. AUC: Before, 0.12 ± 0.06; After, −773.88 ± 106.15, n = 4 mice, **P=0.005, two-sided Paired sample t-test. g. Heatmap showing individual GCaMP6s responses from Type II PVT terminals to Wake-NREM transitions for all subjects. h. Average GCaMP6s response from the terminals of Type II PVT neurons during Wake-NREM transitions (NREM depicted by shaded area), n = 4 mice. i. Quantification of GCaMP6s responses from the terminals of Type II PVT neurons for all Wake-NREM transitions. AUC: Before, −0.47 ± 0.27; After, 739.28 ± 53.04, n = 4 mice, ***P=0.0008, two-sided Paired sample t-test. j. Schematic of the experimental approach used to assess the effect of chemogenetic activation of Type II neurons on sleep/wake state. A representative image of hM3Dq-mCherry expression in Type II neurons within the aPVT. k. Quantification of the percent of time spent in Wake, NREM, and REM sleep states 2 h following IP injection of saline (white and pink bars) or CNO (red bars) in hM3Dq-expressing mice (n = 5 mice). Percent time, Wake: Saline (Pre), 80.72 ± 8.50; CNO, 57.8 ± 9.82; Saline (post), 73.22 ± 6.88; **P=0.002, two-sided Paired sample t-test. NREM: Saline (Pre), 16.40 ± 7.49; CNO, 38.20 ± 8.93; Saline (post), 22.07 ± 5.16. **P=0.007, two-sided Paired sample t-test. REM: Saline (Pre), 1.16 ± 0.96; CNO, 2.80 ± 0.86; Saline (post), 2.39 ± 1.03. l. Quantification of the time spent in Wake, NREM, and REM sleep states 2 h following IP injection of saline (white and pink bars) or CNO (red bars) in mCherry-expressing (control) mice (n = 4 mice). Percent time, Wake: Saline (Pre), 72.30 ± 5.70; CNO, 75.83 ± 9.72; Saline (post), 77.70 ± 5.93. NREM: Saline (Pre), 21.08 ± 3.61; CNO, 18.01 ± 10.03; Saline (post), 17.60 ± 5.77. REM: Saline (Pre), 3.95 ± 3.27; CNO, 2.06 ± 1.64; Saline (post), 2.35 ± 1.50. Box chart legend: box is defined by 25th, 75th percentiles, whiskers are determined by 5th and 95th percentiles, and mean is depicted by the square symbol. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Next, we sought to investigate whether ILPVT corticothalamic neurons were similarly modulated by arousal. To do this, we recorded calcium transients from the cell bodies of ILPVT neurons, and simultaneously performed polysomnographic recordings as described above (Fig. 5a–c). Like Type II PVT neurons, we found that NREM-Wake transitions were associated with significant decreases in the activity of ILPVT neurons, while Wake-NREM transitions yielded the opposite outcome (Fig. 5d–g). Together, these data reveal an unexpected bidirectional correlation of the activity of Type II PVT and ILPVT neurons with unprompted transitions in cortical states, thereby supporting the idea that this PVT–IL loop is modulated by arousal. Importantly, these results are consistent with previous reports linking activation of the aPVT with increased NREM sleep and reduced wakefulness31.

Figure 5. Thalamocortical neurons of the IL are modulated by arousal.

a. Schematic of the viral vector strategy, optical fiber placement and EEG/EMG device implantation used for combined fiber photometry imaging of ILPVT neurons and polysomnographic recordings. b. Representative image depicts GCaMP6s expression and optical fiber placement in IL. c. Sample EEG/EMG recordings of NREM-Wake (left) and Wake-NREM (right) transitions. Dashed lines depict state transitions. d. Heatmap showing individual GCaMP6s responses from ILPVT neurons to NREM-Wake transitions for all subjects. e. Heatmap showing individual GCaMP6s responses from ILPVT neurons to Wake-NREM transitions for all subjects. f. Average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons during Wake-NREM (blue plot) and NREM-Wake (red plot) transitions (dashed line depicts state transition), n = 4 mice. g. Quantification of GCaMP6s responses from ILPVT neurons for all Wake-NREM (left plot) and NREM-Wake (right plot) transitions. AUC, Wake-NREM: Before, −0.14 ± 0.10; After, 188.68 ± 26.92, n = 4 mice, **P=0.006, two-sided Paired sample t-test. NREM-Wake: Before, −0.09 ± 0.21; After, −296.7 ± 49.32, n = 4 mice, **P=0.009, two-sided Paired sample t-test. Box chart legend: box is defined by 25th, 75th percentiles, whiskers are determined by 5th and 95th percentiles, and mean is depicted by the square symbol. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

The IL controls physiological arousal in response to salient stimuli

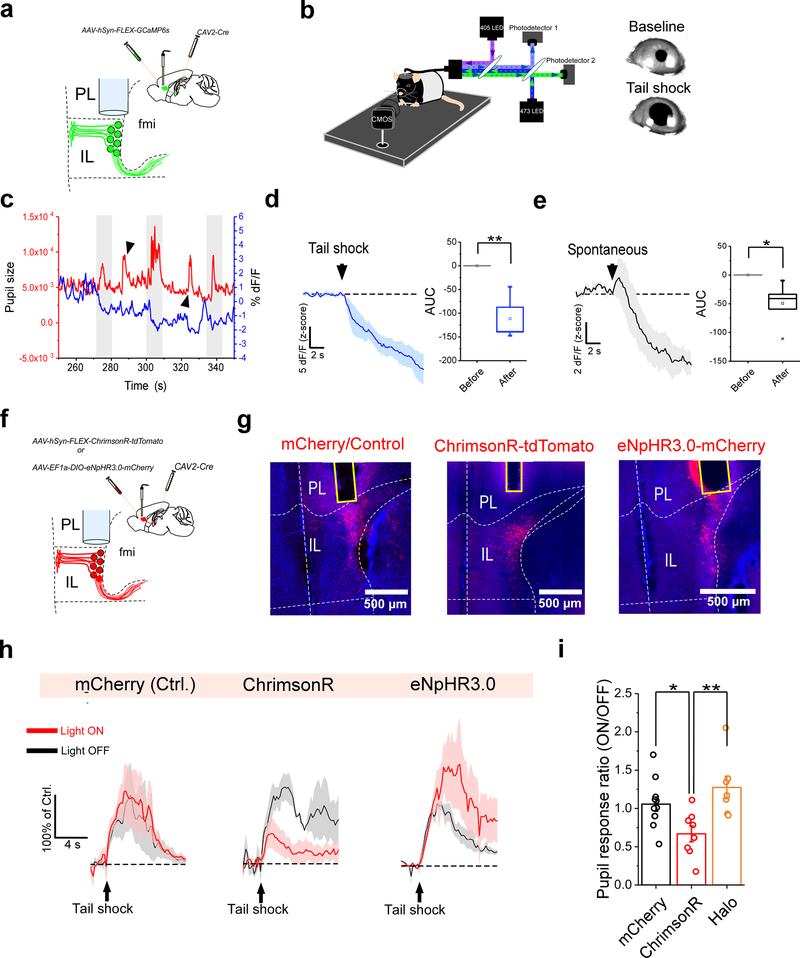

Consistent with our findings, previous reports show that emotionally-arousing events are associated with decreased activity in the IL as well as its human homolog, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)32–34. Additionally, these periods of decreased IL/vmPFC activity are coupled to the emergence of physiological and behavioral arousal, raising the possibility of a causal relationship between these processes. To address this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of bidirectional optogenetic control of ILPVT corticothalamic neurons on a physiological arousal response: pupil dilation. Extensive work has previously demonstrated that fluctuations in pupil size can be reliably used as a proxy for various cognitive processes such as arousal and attention34,35. Therefore, to assess the relationship between the IL and physiological arousal, we recorded pupil size fluctuations in head-fixed mice, while imaging the activity of ILPVT neurons expressing GCaMP6s with fiber photometry (Fig. 6a, b). Under these conditions, we observed that pupil dilations induced by mild tail shocks were consistently associated with a reduction in GCaMP6s fluorescence of ILPVT neurons, suggesting that these two events may be functionally related (Fig. 6c, d). It is possible, however, that concurring pupil dilations and ILPVT inhibition are instead independent correlates of tail shock stimulation. To evaluate this possibility, we analyzed the GCaMP6s fluorescence of ILPVT neurons during spontaneously occurring pupil dilations. Like stimulus-evoked pupil dilations, spontaneous pupil dilations were coupled to the suppression of ILPVT activity (Fig. 6c, e). These findings indicate that, as in humans, IL activity is correlated with physiological arousal34,36. However, to investigate whether IL activity shapes pupillary responses, we used optogenetics to bidirectionally modulate ILPVT neuronal activity during shock-evoked pupillary responses. Our results demonstrate that, while optogenetic excitation of ILPVT neurons with ChrimsonR significantly attenuated pupillary responses to tail shocks, optogenetic inhibition of the same neuronal population using halorhodopsin (Halo/eNpHR3.0) led to a non-significant increase in these responses (Fig. 6f–i). These results indicate that the rodent vmPFC is a negative regulator of state-dependent physiological arousal. In addition, this observation is consistent with our findings that the function of thalamic afferents in IL is inversely related to arousal.

Figure 6. The IL controls physiological arousal in response to salient stimuli.

a. Schematic of the viral vector strategy and optical fiber placement used for combined fiber photometry imaging of GCaMP6s fluorescence from ILPVT neurons and pupillometry. b. Left: diagram of the experimental setup used for head-fixed pupillomery used in conjunction with fiber photometry or optogenetics. Right: representative images of tail shock-evoked pupil dilations obtained in our recording sessions. c. Sample trace of pupil size (area) and ILPVT GCaMP6s signal from an individual recording session. Note that pupil dilations largely coincide with decreases in GCaMP6s fluorescence for both tail shock-evoked (arrowheads) and spontaneously occurring (gray shaded) pupil dilations. d. Left: Average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons during tail shocks. Right: quantification of GCaMP6s responses to tail shocks, n = 6 mice. AUC, Before, −0.02 ± 0.05; After, −111.62 ± 19.94, n = 6 mice, **P=0.005, two-sided Paired sample t-test. e. Left: Average GCaMP6s response from ILPVT neurons during spontaneously occurring pupil dilations, n = 6 mice. Right: quantification of the GCaMP6s responses during spontaneous pupil dilations. AUC, Before, 0.002 ± 0.04; After, −49.33 ± 14.02, n = 6 mice, *P=0.02, two-sided Paired sample t-test. f. Schematic of the viral vector strategy and optical fiber placement used for combined optogenetic manipulation of ILPVT neurons and pupillometry. g. Representative images depicts mCherry (left), ChrimsonR-tdTomato (middle) and Halo-mCherry (right) expression, and optical fiber placement in IL. h. Average pupil responses during ‘light off’ (gray) and ‘light on’ (red) tail shock trials for representative subjects expressing either mCherry (left), ChrimsonR (center) or Halo (right) in ILPVT neurons, n = 10 trials per sample subject (5 trials were ‘light off’ and 5 trials were ‘light on’). i. Quantification of the ratio of ‘light on’/’light off’ pupil dilations following tail shocks. AUC, mCherry, 1.06 ± 0.09, n = 11 mice; ChrimsonR 0.67 ± 0.10, n = 8 mice; Halo, 1.27± 0.15, n = 7 mice; F(2,23) = 6.66, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Group comparisons: mCherry vs ChrimsonR, *P=0.047; mCherry vs Halo, P=0.37; ChrimsonR vs Halo, ***P=0.005. Box chart legend: box is defined by 25th, 75th percentiles, whiskers are determined by 5th and 95th percentiles, and mean is depicted by the square symbol. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

Two functionally distinct neuronal cell types exist within the PVT

In the present work, we used a multidisciplinary approach to define two previously neglected functionally distinct neuronal classes of the PVT. Spanning the entire length of the midline thalamus, the PVT has traditionally been divided into anterior (aPVT, starting at −0.2mm in mice and −0.8 mm in rats) and posterior (pPVT, starting at Bregma: −1.82mm in mice and −3.65 in rats) subregions37,38. While prior studies have considered the functional implications of these two subregions of the PVT, the data surrounding the outcomes from some of these findings have generated ambiguity7,11,12. In addition, definitions of the antero-posterior location of the PVT lack consistency across studies. Here, using genetic markers as a proxy for interrogating neuronal functional identity, we have divided the PVT into two functionally distinct regions: a posterior-biased region composed of Type I neurons, and an anterior-biased region composed of Type II neurons. Notice that this definition diverges from the current nomenclature surrounding the aPVT and pPVT. Indeed, because the distribution of Type I and Type II neurons seems to be graded along the anterior-posterior axis of the PVT, two important observations follow. First, despite lower cellular densities, Type I and Type II neurons do populate the aPVT and pPVT, respectively. Second, a middle portion of the PVT that has been referred to as aPVT in some studies and as pPVT in others, serves as a transition zone with similar proportions of Type I and Type II neurons. This distribution suggests that using current definitions of aPVT and pPVT to ascribe functionally distinct regions to the PVT can be difficult to achieve. As such, we propose a new model of the PVT in which its organization reflects antero-dorsal and postero-ventral gradients, with the transitional medial PVT exhibiting more heterogeneity (Extended Data Fig. 8).

Genetic identity of Type I and Type II PVT neurons

We have identified Drd2 and Gal as genetic markers of Type I and Type II PVT neurons, respectively. Importantly, both genes were largely excluded from neighboring nuclei and displayed little to no co-expression within the PVT. We and others previously identified Drd2 as a PVT marker in rodents18,19. However, no formal definitions or systematic investigations of its distribution across the antero-posterior axis of the PVT had been achieved before. Notably, to our knowledge, our study is the first to define Gal as a PVT marker. This finding is supported by two independent repositories of gene expression – one using ISH (Allen Brain Institute) and another using RNA sequencing from individual thalamic nuclei (ThalamoSeq project39).

While a transgenic mouse line approach effectively granted genetic access to the Drd2-expressing population (Drd2-Cre) of the PVT, this approach was ineffective for targeting the Gal-expressing population. It is unlikely that this was due to the source of the Cre-line or the method used for generating mutants, since we compared both a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic (Gal-Cre/KI87Gsat)20 and a knock-in mouse (Gal-IRES-Cre/Hmun)21. Both mouse lines have been previously used to successfully target hypothalamic Gal neurons21,40. One possible explanation to our inability to transduce PVT Gal neurons is that Gal expression, and as a result Cre expression, is lower in the thalamus when compared to the hypothalamus (Extended Data Fig. 9). Future studies will be required to determine more efficient strategies to gain genetic access to this PVT subpopulation (e.g. in-depth single-cell RNA sequencing).

Functional differences of Type I and II PVT neurons

Our data indicates that, in addition to their genetic and anatomical differences, Type I and Type II are functionally distinct. Specifically, using fiber photometry, we observed that the Type I subpopulation responds in a bidirectional manner to salient stimuli of opposite valence. In contrast, the Type II subpopulation is inhibited by salient stimuli and differentially modulated by arousal. It is important to consider the technical limitations of using fiber photometry bulk fluorescence imaging. Since the activity of individual neurons cannot be directly inferred from the recorded signal, this opens the possibility that individual neurons within our Type I and Type II subpopulations may respond differentially to their overall population signal. Precise determination of whether individual PVT neurons encode valence or salience information would require single cell imaging techniques or in vivo single unit recordings. Despite our inability to conclude that individual Type I and Type II neurons encode valence and salience information, respectively, our collective results demonstrate that – at the population level – these PVT subclasses are functionally distinct.

Prior studies on the posterior PVT, where the majority of Type I neurons reside, have provided increasing evidence for its role in signaling aversive states, emotional memory and adaptive motivated behavior5,41–43. In a recent study from our group, we demonstrated that stress-dependent dopaminergic signaling increases neuronal excitability within the pPVT through activation of D2Rs19. As Type I neurons are D2R positive, our results are consistent with the idea that Type I neurons signal aversive states. Furthermore, we find that the anatomical distribution of this subpopulation of the PVT follows a gradient that is biased towards the posterior PVT, rather than being delineated by a strict antero-posterior boundary. On the other hand, the Type II neuronal population, represents a previously unidentified neuronal subtype of the PVT that is negatively modulated by both salience and arousal. In contrast with our findings, recent studies have indicated that neuronal activity in the PVT is positively correlated to arousal and wakefulness3,4. One potential explanation to this discrepancy is that these studies largely focused on posterior-biased regions of the PVT, where aversion-activated Type I neurons concentrate. Considering the two-dimensional theory of emotion qualifying affect based on valence and arousal44, the role of the pPVT in promoting wakefulness could be directly associated to the structure’s sensitivity to aversive stimuli. In agreement, a recent study demonstrated that starvation (an aversive experience) promotes arousal and wakefulness by engaging calretinin positive neurons of the mid-posterior PVT in mice15. In contrast, the Type II neuronal subpopulation uncovered by us represents the first evidence of a PVT neuronal population that antagonizes arousal and promotes sleep. Therefore, contrary to the dominant view, our findings indicate that the PVT may bidirectionally control arousal and wakefulness in addition to its role in valence.

Parallel processing streams in the PVT

Based on our anatomical tracings and electrophysiological recordings, we have concluded that Type I and II neurons of the PVT form mostly independent channels of information processing with the mPFC. Specifically, Type I selectively innervates the PL while Type II neurons mainly target the IL. In turn, the pPVT which contains mostly Type I neurons is preferentially innervated by the PL, and the aPVT where Type II neurons concentrate receives most of its mPFC input from the IL. Moreover, our electrophysiological recordings indicate that, in addition to being segregated into independent thalamo-corticothalamic loops, Type I and Type II neurons show little to no direct interaction with each other. This suggests that information processed by these two cell types is done in parallel and are not dependent on local interactions within the PVT. Similar parallel processing streams were recently described for the neighboring parafascicular nucleus45. That our findings are consistent with this recent report suggests that the functional organization observed in the PVT and the parafascicular nucleus could be common to other midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei.

The role of PVT-IL circuitry in physiological arousal

Consistent with classical models of an ascending reticular activating system implicating the midline thalamus1, our study demonstrates that a subpopulation of neurons within the PVT gates neuronal responses to arousing stimuli in the IL. Moreover, our evidence that the IL participates in the regulation of physiological responses to arousing stimuli suggests that PVT projections to the IL may impact this process. Notably, both structures participate in emotional and arousal processing2,3,34,36,46. Our findings that the IL is part of a thalamocortical node that processes arousal-related information and controls physiological arousal sheds new light on how this cortical region regulates emotion. Prior reports show that IL activity decreases following fear conditioning32,33. Since here we have demonstrated that reduced IL activity enables physiological arousal, it is possible that the decrease in IL activity associated with fear learning is permissive to fear memory formation32. In rodents, silencing of the IL during fear memory retrieval has been shown to impair fear extinction, whereas activation of IL neurons potentiates extinction memory formation and retrieval47. This indicates that IL activity is required for proper extinction of emotional memories. In this context, the increased activity in PVT–IL circuitry when an animal transitions to a state of lower arousal may serve as a critical pathway to promote general signaling of lower arousal states, thereby minimizing the behavioral and physiological impact of stimuli previously considered threatening. Future studies will be required to investigate the precise mechanisms by which the IL controls autonomic responses to arousing stimuli. Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated direct projections from the IL to autonomic centers within the medulla and the spinal cord27,48.

We note that other midline and intralaminar nuclei that send dense projections to the mPFC (i.e., paratenial, centromedial, and reuniens nuclei) may also participate in arousal signaling49,50. Additionally, thalamic innervation of the mPFC varies in density over its rostral-caudal axis50. Since neighboring thalamic nuclei are embedded in individualized circuits, future studies should assess the contributions of subpopulations within each of these nuclei to arousal signaling, as well as consider differences in the rostral-caudal location of mPFC innervation.

Concluding remarks

The PVT has been implicated in a broad range of functions; however, how the neuronal circuits of the PVT are organized to contribute to each of these functions is not well-understood. Our anatomical and functional characterization of two parallel streams within the PVT should serve as a starting point to begin to disentangle how discrete subpopulations of PVT neurons guide behavior. Moreover, our newly proposed model should prompt a revision of the current conceptualization of how PVT neuronal circuits are organized and may explain previously conflicting observations regarding PVT function.

METHODS

Mice

All procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice used in this study were housed under a 12-h light-dark cycle (6 a.m. to 6 p.m. light), with food and water available ad libitum. The following mouse lines were used: Drd2-Cre (GENSAT – founder line ER44), Gal-Cre (GENSAT – founder line KI87), and Ai14 (The Jackson Laboratory). In addition, we used C57BL/6NJ strain mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Similar numbers of male and female mice 7–12 weeks of age were used for all experiments. Animals were randomly allocated to the different experimental conditions reported in this study.

Viral vectors

AAV9-Syn-Flex-GCaMP6s-WPRE-SV40 was produced by the Vector Core of the University of Pennsylvania. AAV5-Syn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato (Addgene plasmid # 62723) was produced by Addgene. AAV2-EF1a-FLEX/OFF-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP and AAV2-EF1a-FLEX/OFF-hM3Dq-mCherry were produced by Vector Biolabs. AAV9-Syn-DO-GCaMP6s and AAV9-Syn-DO-oScarlett were produced by Charu Ramakrishnan (Deisseroth’s lab, Stanford University). CAV2-Cre was produced by the Adenovirus Vector Core of the Institut de Genetique Moleculaire de Montpellier. AAV9-EF1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry, AAV2-CaMKIIa-mCherry, AAV2-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP, and AAV2-EF1a-DIO-mCherry were produced by the Vector Core of the University of North Carolina. AAV9-EF1a-FLEX-TVA-mCherry (Addgene plasmid # 38044) and AAV9-CAG-FLEX-RG (Addgene plasmid # 38043) were produced by Vigene Biosciences, Inc. EnvA-SAD-ΔG-eGFP (Addgene plasmid # 32635) was produced by the Viral Vector Core of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. All viral vectors were stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. The CreOFF viral vectors (DO and FLEX/OFF) used in this study are fully available from the authors upon request.

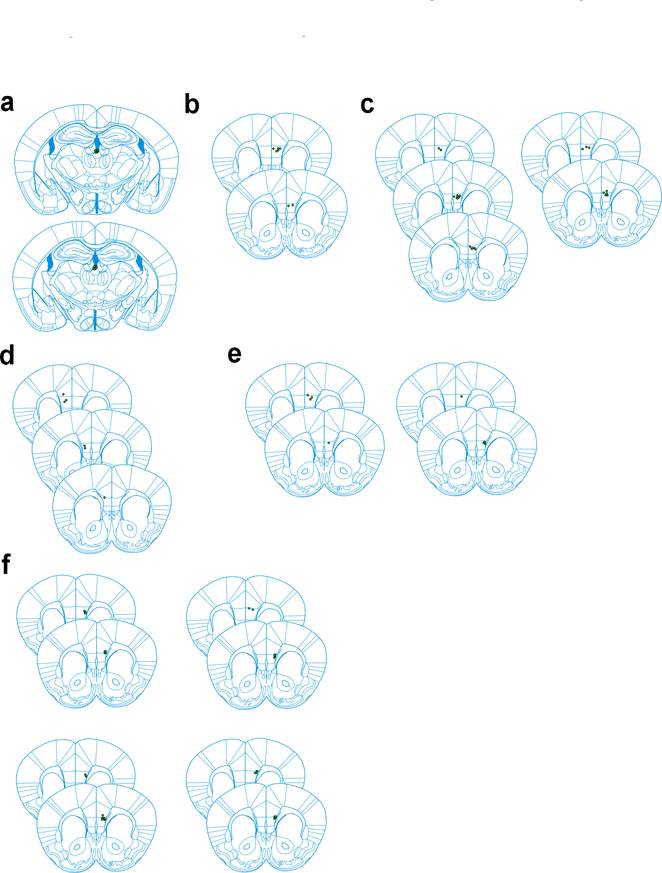

Stereotaxic surgery

All viral injections were performed using previously described procedures5 and an AngleTwo stereotaxic device (Leica Biosystems) at the following stereotaxic coordinates: aPVT, –0.30 mm from Bregma, 0.00 mm lateral from midline, and −4.30 mm vertical from cortical surface; pPVT, –1.60 mm from Bregma, 0.06 mm lateral from midline, and −3.30 mm vertical from cortical surface; IL, 1.50 mm from Bregma, 0.70 mm lateral from midline, and −3.10 mm vertical from cortical surface. For fiber photometry imaging and optogenetic experiments, an optical fiber (400 μm, Doric Lenses) was implanted over the PVT or the IL immediately after viral injections and cemented using Metabond Cement System (Parkell, Inc.) and Jet Brand dental acrylic (Lang Dental Manufacturing Co., Inc.). For simultaneous fiber photometry measurement of GCaMP6s signal in the IL and polysomnographic recordings, an EEG/EMG headmount (Cat. # 8201, Pinnacle Technology Inc.) was positioned immediately behind the optical fiber (secured with Metabond only) and fixed to the skull first using a small amount of cyanoacrylate and subsequently with four EEG screws. To ensure continuity, a 2-part silver epoxy (Cat. # 8226, Pinnacle Technology Inc) was applied in between the screws and the headmount board. Continuity between the screws and the headmount pins was tested using a multimeter (Cat. # 8255, Pinnacle Technology Inc). Next, EMG wires were inserted through a small pocket in the nuchal muscles using a pair of forceps. Once the EEG/EMG headmount was implanted and the EMG wires placed inside the nuchal muscles, dental acrylic was used to secure the device and anchor the optical fiber. Following all surgical procedures, animals were allowed to recover on a heating pad and returned to their home cages after 24 h post-surgery recovery and monitoring. Animals received subcutaneous injections with Metacam (meloxicam, 1–2 mg/kg) for analgesia and anti-inflammatory purposes. All AAVs were injected at a total volume of approximately 1 μl and were allowed 2–3 weeks for maximal expression. Mice without correct targeting of optical fibers, tracers and/or vectors were excluded from this study.

Histology

Animals were deeply anesthetized with euthanasia solution (Vet One) and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 1X, pH 7.4), followed by paraformaldehyde (PFA; 4% in PBS). After extraction, brains were postfixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for a minimum of 2 hours, and subsequently cryoprotected by transferring to a 30% PBS-buffered sucrose solution until brains were saturated (~24–36 h). Coronal brain sections (45 μm) were cut using a freezing microtome (SM 2010R, Leica). For projection mapping experiments, the signal was enhanced using immunohistochemistry. Similar procedures were also employed for validating the specificity of our Cre-OFF constructs. For this, brain sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hr at RT, followed by incubation with primary antibodies in 10% NGS-PBST overnight at 4 °C. Sections were then washed with PBST (5 × 15 min) and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h. All washes and incubations were done over a shaker at low speed. After washing with PBS (5 × 15 min), sections were subsequently mounted onto glass slides and coverslipped with ProLong Diamond antifade (ThermoFisher Scientific). Images were taken using an LSM 780 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Image analysis and cell counting were performed using ImageJ software (Fiji, version 2017 May 30). Optical fiber placements for all subjects included in this study are presented in Extended Data Fig. 10. A description of the histological procedures used for in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments is provided below.

Antibodies

The primary antibodies used were: anti-GFP (1:1000, rabbit, Abcam, catalog# ab13970, validated for both species and application by producer), anti-D2 (1:1000, mouse, Frontier Institute, catalog# D2R-Rb-Af960, validated for both species and application by producer), anti-mCherry (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog# PA5–34974). Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Antibodies were diluted in PBS with 10% NGS and PBST. No publications were found with rigorous validation of the anti-mCherry antibody for the application used in our study. However, the distribution of immunostained axonal projections resembled that of the endogenous mCherry fluorescence.

In Situ hybridization

Sample preparation and ISH procedure (RNAscope)

Fresh-frozen brains from adult male C57BL/6NJ mice (8–12 weeks) were sectioned at a thickness of 16 μm using a Cryostat (Leica Biosystems). Sections were collected onto Superfrost Plus slides (Daigger Scientific, Inc), immediately placed on dry ice and subsequently transferred to a −80°C freezer. Drd2 mRNA signal was detected by using the RNAscope Fluorescent kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Specifically, slides with sections covering the entire antero-posterior spread of the PVT were removed from the −80°C freezer, fixed with freshly prepared ice-chilled 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4°C, and then dehydrated using a series of ethanol solutions at different concentrations (5 min each, room temperature): 1 × 50%, 1 × 70%, and 2 × 100%. Next, sections were treated with Protease IV (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) at room temperature for 30 min. Slides were then washed with PBS twice (1 min each), dried for 5 minutes at room temperature, and sections were circled with an ImmEdge Hydrophobic Barrier PAP Pen (Vector Laboratories). Hybridization was performed on a HybEZ oven for two hours at 40°C by using a Drd2 and/or a Gal probe(Advanced Cell Diagnostics). After this, the slides were washed twice with washing buffer (2 minutes each), then incubated with Hybridize Amp 1-FL, Hybridize Amp 2-FL, Hybridize Amp 3-FL, and Hybridize Amp 4-FL for 30 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 15 minutes, respectively. Next, the slides were washed twice with washing buffer (2 min each) and sections were coverslipped using Diamond Prolong antifade mounting medium with DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Signal detection and analysis

24h after the amplification procedure, dried slides were examined on an LSM 780 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a 63X objective. Signal was subsequently quantified with CellProfiler 3.1.8 using a freely available pipeline (macros) for RNAscope51. A protocol with a step-by-step description of how to implement this pipeline for analyzing RNAscope data was recently published52. All RNAscope data were analyzed in a blinded manner.

Retrograde tracings

For retrograde tracing experiments 2 mg/mL Alexa-Fluor-488 or Alexa-Fluor-555 conjugated cholera toxin B (CTB; ThermoFisher Scientific) were stereotaxically injected into either the aPVT or the pPVT at a volume of 0.4–0.6 μl. Animals were sacrificed as described above 3–4 days after injection.

Fiber photometry

The fiber photometry procedure was performed as previously described19. Briefly, fluorescent signals were recorded using a commercial Mini Cube Fiber photometry apparatus (Doric Lenses) connected to two continuous sinusoidally modulated LED (DC4100, ThorLabs) tuned at 473 nm (211 Hz) and 405 nm (531 Hz), and two separate photoreceivers (2151, Newport Corporation). Both LED were coupled to a large core (400 μm), high NA (0.48) optical fiber patchcord, which was mated to a matching brain implant in each mouse. The light intensity at the interface between the fiber tip and the animal ranged from 10–20 μW (but was constant throughout each testing session). GCaMP6s and autofluorescence (AF) signals were collected by the same fiber and focused onto a separate photoreceiver. Similarly, optogenetic manipulations were achieved through the same optic fiber via a 561 nm DPSS laser (OEM Laser Systems) coupled to an optogenetic port available on the Mini Cube. Fluorescent signals were acquired using an RZ5P acquisition system (Tucker-Davis Technologies; TDT) equipped with a lock-in amplifier for independent demodulation of the GCaMPs and AF signals. The occurrence of behaviorally-relevant events was recorded by the same system via a TTL input. The data was analyzed by first applying a least-squares linear fit to the 405 nm signal to align it to the 470 nm signal. The resulting fitted 405 nm signal was then used to normalize the 473 nm as follows: ΔF/F = (473 nm signal − fitted 405 nm signal)/fitted 405 nm signal. Changes in fluorescence following behaviorally-relevant events were quantified by measuring the area under the ΔF/F curve. All photometry data is presented as z-score of the ΔF/F from baseline (pre-stimulus) segments. All experiments were performed in behavioral chambers (Coulbourn Instruments) and video recorded using video cameras installed above each behavioral chamber. Behavioral variables, such as shocks and social interaction, were marked in the signaling traces via the real-time processors as TTL signals from the video tracking software.

Behavioral protocols

Footshocks

Following habituation to the behavioral chamber, optic fiber-tethered mice received five presentations of a 2-s 1mA unsignaled footshock. The behavioral chamber was illuminated throughout the entire procedure. For optogenetic experiments each subject was presented with a total of ten unsignaled footshocks, five in the presence and five in the absence of laser stimulation.

Tail suspensions

Animals where tethered to an optical patchcord and allowed to habituate for 10 minutes. After this, animals were suspended by their tails by a single experimenter for total of five occurrences, each lasting 10–12 s every two minutes. Calcium signals were detected as described above.

Social interaction

For social interaction experiments, male mice were introduced in a test chamber (Coulbourn Instruments) where they underwent three separate bouts of interaction with a novel ovariectomized C57BL/6NJ female mice (8–12 weeks old). Each bout lasted approximately 2 min. For optogenetic experiments male subjects received a total of six interaction bouts, three in the presence and three in the absence of laser stimulation.

Thermoneutral zone

Behavioral and neuronal responses to a thermoneutral zone were evaluated using custom thermal chambers built by the Section for Instrumentation of the NIMH. Each chamber was equipped with a temperature sensor (Omega), a low-speed ventilator and a thermal camera (FLIR Systems) for imaging temperature gradients across the chamber (ResearchIR Max 4 software, FLIR). The ventilator itself was equipped with an in-line heater and a temperature controller (Omega) commanded by FreezeFrame (Coulbourn Instruments). Upon TTL command, the temperature ramped from room temperature to the desired value (31 °C). Mice were presented with three heating bouts lasting 1 min each. During the heating episodes animals systematically approached the heat source. Concomitant changes in GCaMP6s fluorescence in neurons of the PVT were assessed using fiber photometry.

Electrophysiology

For electrophysiological experiments, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane, decapitated and their brains quickly removed and chilled in ice-cold dissection buffer (110.0 mM choline chloride, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 7.0 mM MgCl2, 25.0 mM glucose, 11.6 mM ascorbic acid and 3.1mM pyruvic acid, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). Coronal sections (300 μm thick) containing the pPVT were cut in dissection buffer using a VT1200S automated vibrating-blade microtome (Leica Biosystems), and were subsequently transferred to incubation chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (118 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 20 mM glucose, 2 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2, at 34 °C, pH 7.4, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). After at least 40 min recovery time, slices were transferred to room temperature (20–24 °C) and were constantly perfused with ACSF.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from PVT neurons were obtained with Multiclamp 700B amplifiers (Molecular Devices). Recordings were done under visual guidance using an Olympus BX51 microscope with transmitted light illumination. Recordings were made in the ACSF and the internal solution for voltage-clamp experiments contained 115 mM cesium methanesulphonate, 20 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM Na2-ATP, 0.4 mM Na3GTP, 10 mM Na-phosphocreatine and 0.6 mM EGTA (pH 7.2). To investigate the synaptic connectivity across neuronal populations of the PVT, ChR2 was selectively expressed onto either Type I or Type II neurons via stereotaxic injection of AAV2-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP or AAV2-EF1a-FLEX/OFF-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP, respectively, into both the aPVT and the pPVT of Drd2-Cre mice and allowed to express for 3 weeks. Acute brain slices containing the PVT were prepared as described above and a blue light (pE-300white; CoolLED Ltd.) was used to stimulate ChR2-expressing neurons. Type I and Type II neurons were identified based on their eYFP fluorescence, or lack thereof. To measure the spontaneous activity of Type I and Type II PVT neurons, acute brain slices from the PVT of either naïve or footshock-stimulated Drd2-Cre:Ai14 mice were prepared as described above. Recordings were always performed on interleaved naïve and footshock-stimulated mice. Current clamp recordings were made with an internal solution containing: 130 mM K-Gluconate, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM Na2AP, 0.4 mM Na3GTP, 10 mM Na-phosphocreatine, 0.6 mM EGTA (pH 7.2). For cells displaying tonic firing, observations were initially made in cell-attached mode and subsequently in current clamp mode during the first 60 s of breaking the seal.

Pupillometry

Head bar surgery

Following stereotaxic surgery for viral vector delivery and optical fiber implantation as described above, a head bar 22.3 mm long and 3mm wide was fixed to the back of the head using metabond and covered with dental acrylic.

Head-fixed pupillometry

After recovery from surgery, mice were acclimated to a custom-built head fixation device as previously described53 under dim light conditions. Briefly, for head-fixation, the protruding sides of the head bar were seated into notches within the stainless-steel custom-built head-fixation frame. Next, the animal’s body was inserted into an acrylic tube ~1.2 inches wide installed on a kinematic base (ThorLabs), with its head extending out of the front of the tube to allow the mouse to grip to edge of the tube with its front paws. The tube was designed such that mice fit comfortably (not tightly) inside. The acclimation procedure lasted between 3–5 sessions, with each session (1 per day) lasting approximately 20 min long. The goal of the acclimation procedure was to minimize the stress caused by the head-fixation procedure. Throughout this process, mice were monitored for signs of struggle. Such signs nearly disappeared by the third day and were essentially absent by day 5.

After mice were fully acclimated to head-fixation, a monochromatic CMOS camera equipped with a macro zoom lens (MVL7000, ThorLabs) was used to collect images from the left pupil at 5 frames per second. High contrast images of the pupil were obtained by using an infrared LED lamp (LIU850A, ThorLabs) to illuminate the eye. For concomitant assessment of GCaMP6s fluorescence in the mPFC or optogenetic manipulations, an optical patch cord was connected to the optical ferrule on the animal’s head. Pupillary responses were triggered by a mild shock (1s, at ~250 μA) delivered to the animal’s tail and recorded using ThorCam 3.3.1 (ThorLabs). The recorded images were subsequently analyzed using Bonsai 2.4, and changes in pupil size (area) were plotted for each session and synchronized to the timestamps of individual tail shocks or optogenetic events recorded in Synapse version 92 (TDT). These timestamps were also used to align pupil data to the photometry signal. Spontaneously occurring pupillary responses were detected using a peak analysis software (Mini Analysis 6.0.3, Synaptosoft, Inc.). Pupil responses were analyzed for a 10s period defined by the onset of the tail shock (or pupillary dilation onset for spontaneous responses) and normalized to the average pupil size for a 2s period immediately preceding the stimulus onset.

Monosynaptic Rabies tracing

Retrograde tracing of monosynaptic inputs onto PVT-projecting (ILPVT) neurons of the IL was accomplished using a previously described method54. Briefly, to selectively map monosynaptic inputs onto ILPVT neurons we first injected ~1 μl of CAV2-Cre in the aPVT of C57BL/6NJ (as described above). Next, a cocktail containing AAV9-FLEX-TVA-mCherry and AAV9-FLEX-RG (2:1) ratio was injected in the IL (~1 μl). Two weeks later mice were injected in the IL with a pseudotyped rabies virus: EnvA-SAD-ΔG-eGFP (1.2 μl). In summary, this method ensures that the rabies virus (eGFP) exclusively infects TVA-expressing ILPVT (mCherry) cells. Importantly, complementation of the modified rabies virus with the rabies glycoprotein (AAV9-FLEX-RG) in TVA-expressing cells permits the generation of infectious particles, which subsequently trans-synaptically infect presynaptic neurons.

Polysomnography

Following the stereotaxic surgery for viral vector delivery and implantation of the EEG/EMG headmount, mice recovered single-housed for 2–3 weeks. Next, mice were transferred to a circular acrylic cage (10” d x 8” h) and connected to an optical patch cord and a preamplifier (100x gain, 0.5 Hz high-pass filter for EEG, 10 Hz high-pass filter for EMG; Pinnacle Technology, Inc.). The preamplifier was in turn connected to a lightweight 4-Ch swivel. Animals were habituated to the chamber for 4–5 sessions (30 min per session, 1 session per day) before experiments started. While in the chambers, mice had free access to food and water. EEG/EMG signals were routed to a data acquisition/ conditioning system (#8206, Pinnacle Technology, Inc.) and further amplified (50x) and filtered (50 Hz for EEG and 200 Hz for EMG). Signals were collected at a sample rate of 500 Hz, digitized and routed to a PC-based acquisition software (SIRENIA®, Sleep, Pinnacle Technology, Inc.).

Recordings were conducted over a four-hour period during the light portion of the light/dark cycle. Continuous EEG/EMG recordings were broken into epochs lasting 10 s. Each epoch was subsequently classified as wake, NREM and REM sleep depending on the waveform occupying >50% of the total epoch duration. Polysomnographic EEG/EMG recordings were scored using a clustering method (SIRENIA®, Sleep Pro, Pinnacle Technology, Inc.). Wakefulness was defined by a desynchronized, high-frequency and low-amplitude EEG with high EMG activity. In contrast, NREM sleep was characterized by a synchronized, low-frequency (<4 Hz) and high-amplitude EEG with low EMG activity, and REM sleep as a period characterized by theta oscillations on EEG and minimal EMG activity. Fiber photometry data associated with polysomnographic recordings were analyzed in a blinded manner.

Statistics and data presentation

All data were imported to OriginPro 2016 (OriginLab Corp.) for statistical analyses. Initially, normality tests (D’Agostino-Pearson and Kolmogorov-Smirnov) were performed to determine the appropriateness of the statistical tests used. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. No assumptions or corrections were made prior to data analysis. Differences between two groups were always examined using a two-sided Student’s t-test, where P<0.05 was considered significant and P>0.05 was considered non-significant. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using ANOVA (one-way and two-way), followed by Tukey’s test. The sample sizes used in our study are about the same or exceed those estimated by power analysis (power = 0.9, α = 0.05). For fiber photometry analyses, the sample size is 4–11 mice. For anatomical/projection analyses, the sample size is 2–3 mice. For RNAscope experiments the sample size is 4–5 mice. For ex vivo electrophysiological recordings of spontaneous activity in PVT neurons the sample size is 19–32 neurons from 3–4 mice. For ex vivo electrophysiological recordings of oEPSC the sample size 10–15 neurons from 2 mice. For pupillometry experiments the sample size is 6–11 mice. All experiments were replicated at least once, and all subjects were randomly allocated to the different experimental conditions.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary

Additional information on experimental design and materials used in our study is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Data availability

All the data that support the findings presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

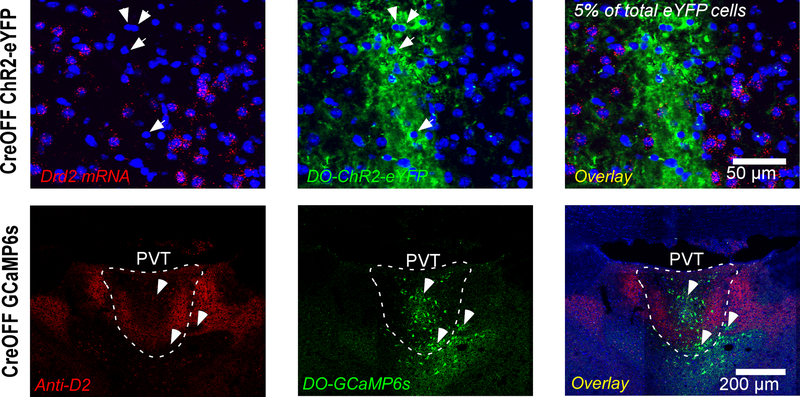

Extended Data Fig. 1. Validation of our CreOFF vectors.

Top: Representative images from an RNAscope ISH experiment used to validate our FlexOFF (a.k.a. CreOFF) construct (produced by Vector Biolabs). AAV2-EF1a-FLEX/OFF-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was injected in the PVT of a Drd2-Cre mouse and allowed to express for two weeks. Notice that ChR2-eYFP is almost exclusively (~95%) expressed in Drd2-negative cells (arrows). Data from 1 mouse, with the experiment independently repeated twice. Similar results were obtained on both occasions. Bottom: Representative images from an immunohistochemistry experiment used to validate our DO (CreOFF) construct (cloned and packaged by Charu Ramakrishnan). AAV9-Syn-DO-GCaMP6s was injected in the PVT of a Drd2-Cre mouse and allowed to express for two weeks. An antibody against D2R (see Methods) was used to label D2R+ regions of the PVT. Notice that GCaMP6s expression is selectively observed in areas where D2 labeling is low or absent (arrows). Data from 1 mouse.

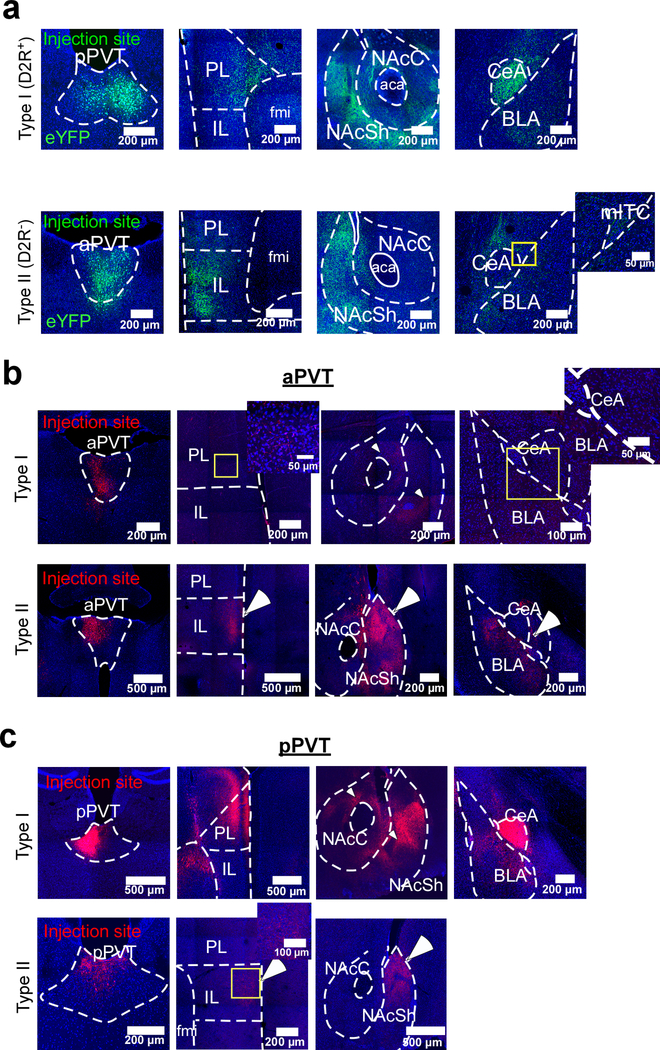

Extended Data Fig. 2. Anatomical projections from Type I and Type II neurons of the PVT.

a. Representative images showing the distribution of axonal projections from Type I neurons of the pPVT (top) and Type II neurons of the aPVT (bottom) across three major PVT targets: the mPFC, the NAc and the amygdala (data from 3 mice). b. Representative images showing the distribution of the axonal projections from Type I (top) and Type II (bottom) neurons of the aPVT across the mPFC, the NAc and the amygdala. Notice that since Type I neurons are rather scarce in the aPVT, the efferent projections from these neurons are sparse and more difficult to resolve. Data from 2 mice. c. Representative images show the distribution of the axonal projections from Type I (top) and Type II (bottom) neurons of the pPVT across the mPFC, the NAc and the amygdala. Because only a few Type II neurons populate the pPVT, the efferent projections from these neurons are sparse and not as dense when compared to those of Type I neurons. Data from 2 mice. Arrowheads indicate regions selectively innervated by Type I neurons, whereas arrows indicate regions selectively innervated by Type II neurons. Magnifications of the areas depicted by the yellow boxes are shown as inserts. Anterograde tracing experiments were independently repeated three times, with similar results obtained across repetitions.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Type II neurons selectively express Galanin (Gal).