Abstract

Background

With rising costs of cancer care, this study aims to estimate the prevalence of, and factors associated with, medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifices due to cancer in the United States.

Methods

We identified 963 cancer survivors from the 2016 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey - Experiences with Cancer. Medical financial hardship due to cancer was measured in material (e.g., filed for bankruptcy), psychological (e.g. worry about paying bills and finances) and behavioral (e.g., delaying or forgoing care due to cost) domains. Non-medical financial sacrifices included changes in spending and use of savings. Multivariable logistic models were used to identify characteristics associated with hardship intensity and sacrifices stratified by age group (18–64 or 65+ years).

Results

Among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years, 53.6%, 28.4% and 11.4% reported at least one, two, or all three domains of hardship, respectively. Among survivors aged 65+ years, corresponding percentages were 42.0%, 12.7% and 4.0%. Moreover, financial sacrifices due to cancer were more common in survivors aged 18–64 years (54.2%) than in survivors 65+ years (38.4%) (p<.001). Factors significantly associated with hardship intensity in multivariable analyses included low income and educational attainment, racial/ethnic minority, comorbidity, lack of private insurance coverage, extended employment change, and recent cancer treatment. Most were also significantly associated with financial sacrifices.

Conclusion

Medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices are substantial among cancer survivors in the United States, particularly for younger survivors.

Impact

Efforts to mitigate financial hardship for cancer survivors are warranted, especially for those at high risk.

Keywords: cancer survivorship, financial hardship, financial sacrifices, insurance, employment, cost of cancer care

Introduction

Medical financial hardship, including problems paying medical bills, financial distress, and delaying or forgoing medical care due to cost, is a common lasting effect of cancer diagnosis and treatment for cancer survivors and their families (1–7). Medical financial hardship has been linked to higher symptom burden (8–10) and worse health-related quality of life (10–13). Extreme financial insolvency (i.e., bankruptcy) is associated with increased risk of mortality (14).

With rising prices for cancer care, especially oral and infused antineoplastic agents, and increasing patient cost-sharing, research describing medical financial hardship has increased rapidly (1), enriching understanding of its prevalence, risk factors, and health consequences. Depending on the study population and measurement of medical financial hardship, previous studies reported prevalence as high as two-thirds of cancer survivors. Risk factors include sociodemographic characteristics such as younger age, being female, racial/ethnic minority, lack of health insurance, high cost-sharing private insurance plan, low family income, and employment changes (3,7,15). Clinical factors such as receipt of adjuvant therapy and recent treatment are also associated with hardship (1–3,7,16). However, prior research findings in clinical settings had limited generalizability as they often include only certain types of cancers from a single institute or city (1,2). Previous studies using national survey data to compare cancer survivors and individuals without a cancer history did not distinguish between medical financial hardship due to cancer from other reasons (7,15). Moreover, few national studies examined the intensity of medical financial hardship across multiple domains or other non-medical financial sacrifices as a result of cancer, including changes in spending, use of savings, or changes to housing. The current study addresses these gaps.

Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014 has markedly changed the landscape of insurance coverage, a strong determinant of medial financial hardship, among cancer population (17–19). The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to low-income residents of the states that opted-in and offers affordable private insurance on the marketplace through subsidies to low- and middle-income families. It prohibits individual insurance plans from preexisting condition exclusions and lifetime and annual coverage limits. It also includes measures to close the “donut hole” in the Medicare Part D prescription drug plan for seniors. Identifying risk factors for financial hardship intensity and sacrifices post the ACA can inform identification of cancer survivors at high risk for intervention in modern oncology and primary care settings.

Cancer-specific medical financial hardship was measured comprehensively in a nationally representative sample with the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) -Experiences with Cancer questionnaire (20) in 2016, with questions related to problems paying medical bills, bankruptcy, financial worries, delaying or forgoing care because of cost, and financial sacrifices due to cancer including reducing spending on food, changes to housing, and using savings set aside for other purposes. Using these newly available data, we identified factors associated with the intensity of medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices in cancer survivors. Because of the age-eligibility for Medicare insurance coverage in those aged 65+ years and the inter-relationship between employment status and private health insurance coverage in those aged 18–64 years, we stratified our analyses by age group.

Materials and Methods

Data and Sample

Adult cancer survivors were identified from the 2016 MEPS conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/index.jsp). The MEPS is a nationally representative sample of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population, which collects detailed information on health insurance coverage, health care utilization and expenditures, and health conditions through an overlapping panel design. Each panel within the sample is interviewed at five rounds over two calendar years. Among the two panels of 34,655 participants in 2016, those aged 18 years or older who reported a cancer history were invited to complete the Experiences with Cancer self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) after confirmation of eligibility during Round 3 of Panel 20 and Round 1 of Panel 21. The survey included questions about the effects of cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of the treatment on finances, health insurance, and employment. Among MEPS respondents, the response rate for the cancer SAQ was 81.2% and the overall response rate for the 2016 MEPS was 46.0%, resulting in an overall response rate of 37.4%.

Among the 1,236 cancer survivors, we excluded those diagnosed with only non-melanoma skin cancer and/or skin cancer with unknown kind (n=267; almost all were non-Hispanic whites; other demographics were comparable to survivors included in the analysis). Also excluded were individuals aged 65+ years without Medicare (n=6) because of the small number, resulting in a total of 963 cancer survivors in the analysis.

Measures

The MEPS Experience with Cancer SAQ contains a series of questions about financial hardship associated with cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment (Supplemental Table 1). Consistent with earlier studies, we characterized medical financial hardship in three domains—material, psychological, and behavioral(1,16). Material hardship was measured by three questions asking if cancer survivors ever (1) had to borrow money or go into debt, (2) were unable to cover their share of the cost of cancer care, and (3) had to file for bankruptcy. Psychological hardship was measured by three questions asking if survivors ever worried or were concerned about (1) having to pay large medical bills, (2) their family’s financial stability, and (3) keeping their job and maintaining their income. Behavioral hardship was measured by a series of questions asking if they ever delayed, forewent, or made other changes to their cancer care because of cost. Five types of care were assessed: prescription medicine, visit to specialist, treatment (other than prescription medicine), follow up care, and mental health services, with an additional choice of “Other”. No specification for the “Other” type was provided and it could apply to any other types of care related to cancer treatment or symptoms such as genetic counseling, dental care, eye glasses, and primary care. We generated a dichotomous summary measure for each financial hardship domain, and created an intensity measure of zero, one, two, and three domain(s) of medical financial hardship.

The MEPS Experience with Cancer SAQ also included questions about financial sacrifices made by survivors and their family members because of cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment: (1) reducing spending on vacation or leisure activities, (2) delaying large purchases such as for a car, (3) reducing spending on basics such as food and clothing, (4) using savings set aside for other purposes such as retirement or educational funds, (5) making a change to their living situation such as selling or refinancing a home or moving to a smaller residence, and (6) other. A dichotomous summary measure of any financial sacrifices was created.

We hypothesized that the following patient characteristics were risk factors of medical financial hardship and financial sacrifice associated with cancer based on published research (3,7,16): age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL), health insurance coverage, number of comorbid conditions, and years since last cancer treatment. For adults aged 18–64 years, employment change due to cancer included taking extended paid time off from work or unpaid time off, or making a change in hours, duties or employment status.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were stratified by age group (aged 18–64 years and 65+ years). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. The percentages of cancer survivors reporting medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices were generated and compared between the two age groups. We fitted multivariable ordinal logistic regression models to identify survivor characteristics associated with medical financial hardship intensity and multiple logistic regression models for financial sacrifices, adjusting for age group, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, family income, health insurance, number of comorbidities, year since last cancer treatment, and employment changes (for only survivors aged 18–64 years). Adjusted percentages and odd ratios were calculated for medical financial hardship intensity and any financial sacrifice.

To further account for the dynamic contribution of different items to a specific financial hardship domain, a sensitivity analysis was conducted (21). Principal factor analysis with Promax rotation was performed with the multiple items of each domain to generate a factor score for each participant. The factor scores of the three domains were summed and then trichotomized as <−1, −1 to 1, and >1 as a measure of medical financial hardship intensity and used in ordinal logistic regressions mentioned above.

All analyses accounted for the complex MEPS design and nonresponse using SAS 9.4 and STATA/IC 14.1. Statistical tests were 2-sided with alpha set at 0.05.

Results

More than half (59.3%) of the cancer survivors were aged 65+ years (Table 1). The majority were female, non-Hispanic white, married, and had private health insurance coverage. 23.9% of the survivors were diagnosed with female breast cancer and 15.2% were diagnosed with prostate cancer. Compared to cancer survivors aged 18–64 years, those aged 65+ years were more likely to be unmarried, had lower educational attainment and more comorbid conditions. Among survivors aged 18–64 years, 40.1% were employed at or after diagnosis and did not have to make extended employment changes due to cancer and 31.6% were employed at or after diagnosis and made extended changes in employment due to cancer. The remainder (28.3%) was not employed at or after diagnosis or data for employment were missing. In both age groups, approximately 40% of cancer survivors had their last cancer treatments within the 5 years preceding the survey. Respectively, 26.6% and 21.6% of survivors aged 18–64 years and 65+ years were treated within a year prior to the survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cancer Survivors, MEPS 2016

| Total | Age 18–64 years | Age 65+ years | Χ2 P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | ||

| Total | 963 | 100.0 | 401 | 100.0 | 562 | 100.0 | -- |

| Age group | -- | ||||||

| 18–54 | 206 | 20.2 | 206 | 49.5 | -- | -- | |

| 55–64 | 195 | 20.6 | 195 | 50.5 | -- | -- | |

| 65–74 | 270 | 28.5 | -- | -- | 270 | 48.0 | |

| ≥ 75* | 292 | 30.8 | -- | -- | 292 | 52.0 | |

| Sex | 0.002 | ||||||

| Male | 366 | 38.8 | 119 | 31.8 | 247 | 43.6 | |

| Female | 597 | 61.2 | 282 | 68.2 | 315 | 56.4 | |

| Race / ethnicity | 0.05 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white only | 646 | 81.1 | 240 | 78.1 | 406 | 83.2 | |

| Other race/ethnicities # | 317 | 18.9 | 161 | 21.9 | 156 | 16.8 | |

| Current marital status | 0.01 | ||||||

| Married | 516 | 58.0 | 239 | 63.9 | 277 | 53.9 | |

| Not married† | 447 | 42.0 | 162 | 36.1 | 285 | 46.1 | |

| Education | 0.004 | ||||||

| Less than high school graduate | 178 | 13.7 | 68 | 10.5 | 110 | 15.9 | |

| High school graduate | 292 | 30.0 | 111 | 25.8 | 181 | 32.9 | |

| Some college or more | 493 | 56.3 | 222 | 63.7 | 271 | 51.2 | |

| Current family income as percent of poverty line | 0.07 | ||||||

| Low-income ≤138% | 248 | 19.5 | 111 | 20.0 | 137 | 19.1 | |

| Middle-income 139–400% | 366 | 35.0 | 141 | 29.8 | 225 | 38.6 | |

| High-income >400% | 349 | 45.5 | 149 | 50.2 | 200 | 42.4 | |

| Employment changes‡ | -- | ||||||

| Employed at or after diagnosis without extended change due to cancer | 134 | 40.1 | -- | -- | |||

| Employed at or after diagnosis and took extended change due to cancer | 127 | 31.6 | -- | -- | |||

| Not employed at or after diagnosis/missing | 140 | 28.3 | -- | -- | |||

| Current health insurance for age <65§ | -- | ||||||

| Age <65, any private | 259 | 74.9 | -- | -- | |||

| Age <65, public only | 121 | 21.7 | -- | -- | |||

| Age <65, uninsured | 21 | 3.3 | -- | -- | |||

| Current health insurance for age 65+ § | -- | ||||||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and private | -- | -- | 288 | 56.5 | |||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and other public | -- | -- | 85 | 11.0 | |||

| Age 65+*, Medicare only | -- | -- | 189 | 32.5 | |||

| Number of known MEPS priority conditions (excluding cancer) †† | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 107 | 11.2 | 79 | 20.7 | 28 | 4.6 | |

| 1 | 182 | 18.0 | 115 | 28.4 | 67 | 10.9 | |

| 2 | 175 | 20.2 | 74 | 21.7 | 101 | 19.2 | |

| 3–8 | 499 | 50.6 | 133 | 29.1 | 366 | 65.3 | |

| Cancer site& | |||||||

| Female breast | 230 | 23.9 | |||||

| Prostate | 146 | 15.2 | |||||

| Colon | 75 | 7.8 | |||||

| Cervix | 67 | 7.0 | |||||

| Melanoma | 62 | 6.4 | |||||

| Uterus | 54 | 5.6 | |||||

| Lung | 31 | 3.2 | |||||

| Lymphoma | 28 | 2.9 | |||||

| Bladder | 25 | 2.6 | |||||

| Other | 193 | 20.0 | |||||

| Multiple sites | 52 | 5.4 | |||||

| Years since last cancer treatment | 0.55 | ||||||

| <1 | 232 | 23.6 | 108 | 26.6 | 124 | 21.6 | |

| 1 to <5 | 186 | 18.4 | 87 | 18.0 | 99 | 18.7 | |

| ≥5 ¶ | 418 | 44.9 | 153 | 42.8 | 265 | 46.3 | |

| Never treated / missing | 127 | 13.1 | 53 | 12.6 | 74 | 13.4 | |

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Age top-coded ≥ 85 by the MEPS. Bold font indicates statistically significant (p<0.05).

Other race/ethnicities include Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, Asian, other race or multiple races.

Not married includes widowed, divorced, separated, or never married.

Public insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, State Children’s Health Insurance Program, and/or other public hospital/physician coverage. TRICARE/CHAMPVA was treated as private coverage, as were employer-based, union-based, and other private insurance.

Employment change due to cancer was not considered for cancer survivors aged 65+ years because the majority was not employed.

Conditions include arthritis, asthma, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease (angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, other heart condition/disease), high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke.

Distribution of cancer site not shown by age group due to small cell sizes.

Years since last cancer treatment top-coded at ≥20 by the MEPS.

Medical Financial Hardship

The overall percentages for reporting ever having any material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardship associated with cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of the treatment were 15.5%, 30.8%, and 26.5%, respectively (Table 2). Compared to adults aged 65+ years, those aged 18–64 years were more likely to report any material and psychological financial hardship (both p<0.001). Within the domain of behavioral financial hardship, cancer survivors aged 18–64 years had higher percentages of reported delaying, forgoing, and/or making other changes to prescription drugs, visiting specialists, and follow up care because of cost than those aged 65+ years (all p<0.05). Younger cancer survivors also had higher percentages of two and three domain(s) of financial hardship (17.0%, and 11.4%, respectively) than older survivors (8.7%, and 4.0%, respectively) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Weighted Percentages of Financial Hardship Associated with Cancer, Treatment, or Lasting Effects of Treatment, by Age group, MEPS 2016

| All ages (n=963) | 18–64 years (n =401) | 65+ years* (n=562) | Chi-square P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material financial hardship | ||||

| Had to borrow money or go into debt | 7.1 (5.5 – 9.1) | 10.9 (8.1 – 14.4) | 4.4 (3.0 – 6.5) | <0.001 |

| Filed for bankruptcy | 1.5 (0.9 – 2.6) | 1.9 (1.0 – 3.7) | 1.2 (0.6 – 2.6) | 0.33 |

| Unable to cover share of the costs of cancer care | 11.4 (9.4 – 13.9) | 16.8 (13.1 – 21.2) | 7.8 (5.6 – 10.8) | <0.001 |

| Any material financial hardship † | 15.5 (13.2 – 18.2) | 23.1 (18.9 – 28) | 10.4 (7.9 – 13.5) | <0.001 |

| Psychological financial hardship | ||||

| Worried about paying large medical bills | 25.5 (22.4 – 28.8) | 33.5 (28.2 – 39.1) | 20.0 (16.5 – 23.9) | <0.001 |

| Worried about family's financial stability | 22.6 (19.8 – 25.7) | 30.7 (25.7 – 36.2) | 17.1 (13.9 – 20.7) | <0.001 |

| Concerned about keeping job and income or earnings | 15.0 (12.6 – 17.7) | 23.5 (19.5 – 28.1) | 9.1 (6.7 – 12.2) | <0.001 |

| Any psychological financial hardship ‡ | 30.8 (27.6 – 34.2) | 41.1 (35.3 – 47.1) | 23.7 (19.9 – 27.9) | <0.001 |

| Behavioral financial hardship | ||||

| Delay/forgo/make other changes to the following cancer care because of cost | ||||

| Prescription medicine | 5.8 (4.3 – 7.7) | 8.5 (5.8 – 12.2) | 3.9 (2.6 – 5.8) | 0.003 |

| Visit to specialist | 5.4 (4.1 – 7.2) | 9.4 (6.6 – 13.1) | 2.7 (1.6 – 4.6) | <0.001 |

| Treatment (other than prescription medicine) | 3.3 (2.3 – 4.5) | 3.7 (2.3 – 6.1) | 2.9 (1.8 – 4.7) | 0.50 |

| Follow up care | 7.3 (5.8 – 9.0) | 11 (8.3 – 14.3) | 4.7 (3.2 – 7) | <0.001 |

| Mental health services | 2.5 (1.6 – 3.8) | 3.4 (2.1 – 5.6) | 1.9 (0.9 – 3.7) | 0.16 |

| Other | 12.8 (10.5 – 15.4) | 11.3 (8.5 – 14.8) | 13.8 (10.8 – 17.4) | 0.27 |

| Any behavioral hardship ¶ | 26.5 (23.4 – 29.9) | 29.2 (24.1 – 34.9) | 24.7 (20.9 – 28.9) | 0.18 |

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Note: All the percentages were unadjusted percentages.

Age top-coded ≥ 85 by the MEPS. Bold font indicates statistically significant (p<0.05).

Any material financial hardship was defined as having responded yes to one or more of the individual material financial hardship measures including have to borrow money or go into debt because of cancer, unable to cover share of the cost of medical care visits for cancer, and/or file for bankruptcy because of cancer.

Any psychological financial hardship was defined as having responded yes to one or more of the individual psychological financial hardship measure including worried about paying large medical bills, worried about family's financial stability, and/or concerned about keeping job and income or earnings because of cancer.

Any behavioral financial hardship was defined as having responded yes to one or more of the adherence measure including prescription medicine, visit to specialist, follow up care, treatment, mental health services, and/or other non-adherence.

Figure 1.

Medical financial hardship associated with cancer by age group, unadjusted (N=963)

Weighted percentages of reporting none, one, two, and all three domains of material, psychological, and behavioral medical financial hardship in cancer survivors, by age group. Data are from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2016.

Analyses of medical financial hardship intensity are displayed in Table 3 and Supplemental Tables 2 – 3 (adjusted percentages) and 4 (adjusted odd ratios). Among those 18–64 years, being younger (18–54 years), male, having lower educational attainment, lower family income, being uninsured or publicly-insured, and experiencing a shorter time since last cancer treatment were significantly associated with higher medical financial hardship intensity (Table 3). Moreover, survivors who were employed at or after diagnosis and took extended paid or unpaid leave or switched to part time due to cancer were most likely to report multiple domains of hardship compared to those who were employed but did not take extended leave or switch to part time or those not employed at or after diagnosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted weighted percentages of medical financial hardship intensity by age group, MEPS 2016

| 18–64 years (N=401) | 65+ years (N=562) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No hardship | One domain of hardship | Multiple domains of hardship | P | No hardship | One domain of hardship | Multiple domains of hardship | P | |

| Age group | <0.001 | 0.05 | ||||||

| 18–54 | 41.1 | 21.0 | 37.9 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| 55–64 | 51.6 | 29.6 | 18.9 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| 65–74 | -- | -- | -- | 52.3 | 32.3 | 15.4 | ||

| ≥ 75* | -- | -- | -- | 62.9 | 26.5 | 10.5 | ||

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Male | 37.0 | 26.5 | 36.5 | 60.8 | 27.8 | 11.4 | ||

| Female | 50.8 | 24.1 | 25.1 | 55.6 | 30.6 | 13.8 | ||

| Race / ethnicity | 0.06 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white only | 49.0 | 25.0 | 25.9 | 61.0 | 28.0 | 10.9 | ||

| Other race/ethnicities# | 36.6 | 27.0 | 36.5 | 41.9 | 37.0 | 21.1 | ||

| Current marital status | 0.56 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Married | 44.4 | 25.2 | 30.4 | 58.4 | 29.1 | 12.5 | ||

| Not married† | 50.3 | 23.9 | 25.7 | 57.4 | 29.6 | 13.0 | ||

| Education | 0.003 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than high school graduate | 30.5 | 30.4 | 39.1 | 61.5 | 27.3 | 11.2 | ||

| High school graduate | 47.9 | 17.3 | 34.8 | 55.0 | 30.8 | 14.1 | ||

| Some college or more | 48.2 | 28.2 | 23.6 | 58.6 | 28.9 | 12.5 | ||

| Current family income as percent of poverty line | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low-income ≤138% | 39.9 | 27.0 | 33.0 | 52.6 | 28.6 | 18.8 | ||

| Middle-income 139–400% | 39.5 | 27.1 | 33.4 | 55.6 | 27.5 | 16.9 | ||

| High-income >400% | 52.9 | 24.3 | 22.9 | 62.2 | 31.8 | 6.0 | ||

| Employment changes ‡ | <0.001 | -- | ||||||

| Employed at or after diagnosis without extended change due to cancer | 48.2 | 25.2 | 26.6 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Employed at or after diagnosis and took extended change due to cancer | 39.5 | 26.7 | 33.8 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Not employed at or after diagnosis/missing | 47.0 | 25.5 | 27.6 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Current health insurance for age <65§ | <0.001 | -- | ||||||

| Age <65, any private | 54.1 | 23.7 | 22.2 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Age <65, public only | 36.4 | 27.2 | 36.4 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Age <65, uninsured | 46.7 | 25.7 | 27.6 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Current health insurance for age 65+§ | -- | <0.001 | ||||||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and private | -- | -- | -- | 56.6 | 30.9 | 12.5 | ||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and other public | -- | -- | -- | 77.0 | 12.3 | 10.7 | ||

| Age 65+*, Medicare only | -- | -- | -- | 52.8 | 33.0 | 14.3 | ||

| Number of known MEPS priority conditions (excluding cancer) †† | 0.26 | 0.006 | ||||||

| 0–1 | 51.1 | 24.1 | 24.8 | 70.4 | 22.0 | 7.6 | ||

| 2–8 | 42.0 | 26.1 | 32.0 | 55.5 | 30.8 | 13.7 | ||

| Years since last cancer treatment | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| <1 | 42.1 | 26.1 | 31.8 | 47.6 | 34.6 | 17.8 | ||

| 1 to <5 | 47.1 | 25.1 | 27.7 | 50.2 | 33.5 | 16.3 | ||

| ≥5 ¶ | 50.1 | 24.4 | 25.5 | 61.2 | 27.7 | 11.1 | ||

| Never treated / missing | 42.5 | 26.0 | 31.5 | 73.0 | 20.3 | 6.7 | ||

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Note: Three domains of financial hardship included material, psychological, and behavioral domains. Multivariable ordinal logistic models adjusted for age group, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, family income, employment change due to cancer (only for 18–64 years), health insurance, number of conditions, year since last cancer treatment. Bold font indicated statistically significant at alpha=0.05.

Age top-coded ≥ 85 by the MEPS.

Other race/ethnicities include Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, Asian, other race or multiple races.

Not married includes widowed, divorced, separated, or never married.

Employment change due to cancer was not considered for cancer survivors aged 65+ years because the majority was not employed.

Public insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, State Children’s Health Insurance Program, and/or other public hospital/physician coverage. TRICARE/CHAMPVA was treated as private coverage, as were employer-based, union-based, and other private insurance.

Conditions include arthritis, asthma, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease (angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, other heart condition/disease), high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke.

Years since last cancer treatment top-coded at ≥20 by the MEPS.

Among the older group, minority race/ethnicity, higher education attainment, lower family income, Medicare-insured only, 2 or more comorbid conditions, and shorter time since last cancer treatment were associated with higher medical financial hardship intensity (Table 3). (all p<0.01).

The sensitivity analysis with factor scores showed similar patterns with family income, insurance coverage, and time since last cancer treatment identified as strong predictors of financial hardship intensity in both age groups (Supplemental Table 5).

Financial Sacrifices

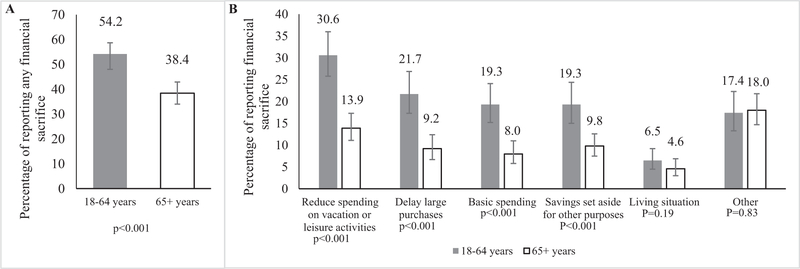

Financial sacrifices associated with cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effect of the treatment, were more common among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years than among those aged 65+ years (54.2% vs. 38.4%; p<0.001, Figure 2). Compared to the older age group, younger cancer survivors were more likely to report reduced spending for vacation or leisure activities (30.6% vs 13.9%), delaying large purchases (21.7% vs 9.2%), reducing basic spending (19.3% vs 8.0%), and utilizing savings set aside for other purposes (19.3% vs 9.8%) (all p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Financial sacrifice associated with cancer by age group, unadjusted (N=963)

(A) Weighted percentages of individuals reporting any financial sacrifice; (B) Percentages of individuals reporting separate measures of financial sacrifice. Data are from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2016. Chi-square tests were used to compare between the two age groups and calculate the p-values. Any financial sacrifices were defined as having responded yes to one or more of the individual financial sacrifice measures including reduce spending on vacation or leisure activities, delay large purchases, reduce basic spending, use savings set aside for other purposes, make a change to living situation, and/or other sacrifice because of cancer.

Among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years, being younger (18–54 years), male, considered a racial or ethnic minority, education less than high school graduate, and with moderate family income (139%−400% FPL) were associated with higher percentages of any financial sacrifices in adjusted analyses (Table 4). Cancer survivors who were employed at or after diagnosis and took extended paid or unpaid leave or switched to part time were more likely to report any financial sacrifice than those who were employed but did not take extended leave or switch to part time or who were not employed at or after diagnosis. Among survivors aged 65+ years, financial sacrifices were more common among those with 2 or more comorbid conditions and those 1 to 5 years post treatment (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 6).

Table 4.

Adjusted weighted percentages of any financial sacrifice, by age group, MEPS 2016 (N=963)

| 18–64 years | 65+ years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted % | 95% CI | P | Adjusted % | 95% CI | P | |

| Age group | 0.003 | 0.08 | ||||

| 18–54 | 62.0 | (54.2 – 69.8) | -- | -- | ||

| 55–64 | 46.8 | (39.9 – 53.8) | -- | -- | ||

| 65–74 | -- | -- | 43.0 | (35.6 – 50.3) | ||

| ≥ 75* | -- | -- | 34.2 | (28.5 – 39.9) | ||

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.57 | ||||

| Male | 63.0 | (53.5 – 72.5) | 52.1 | (42.1 – 62.2) | ||

| Female | 50.0 | (43.2 – 56.8) | 63.5 | (58.4 – 68.6) | ||

| Race / ethnicity | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white only | 51.7 | (45.1 – 58.3) | 36.5 | (31.4 – 41.6) | ||

| Other race/ethnicities# | 63.7 | (54.4 – 73.0) | 47.9 | (37.8 – 57.9) | ||

| Current marital status | 0.11 | 0.44 | ||||

| Married | 57.3 | (50.6 – 64.1) | 40.3 | (33.4 – 47.2) | ||

| Not married† | 48.4 | (39.7 – 57.1) | 36.1 | (29.0 – 43.1) | ||

| Education | <0.001 | 0.30 | ||||

| Less than high school graduate | 79.5 | (67.2 – 91.8) | 30.7 | (19.9 – 41.4) | ||

| High school graduate | 58.2 | (48.2 – 68.3) | 39.4 | (31.9 – 46.9) | ||

| Some college or more | 48.6 | (41.4 – 55.8) | 40.2 | (33.6 – 46.8) | ||

| Current family income as percent of poverty line | 0.04 | 0.21 | ||||

| Low-income ≤138% | 56.9 | (44.1 – 69.7) | 39.8 | (29.7 – 50.0) | ||

| Middle-income 139–400% | 64.3 | (54.8 – 73.9) | 43.8 | (36.0 – 51.6) | ||

| High-income >400% | 47.3 | (38.5 – 56.1) | 33.1 | (25.4 – 40.7) | ||

| Employment Changes ‡ | <0.001 | -- | ||||

| Employed at or after diagnosis without extended change due to cancer | 45.4 | (36.0 – 54.9) | -- | -- | ||

| Employed at or after diagnosis and took extended change due to cancer | 69.9 | (60.9 – 78.8) | -- | -- | ||

| Not employed at or after diagnosis/missing | 49.4 | (40.0 – 58.7) | -- | -- | ||

| Current health insurance for age <65§ | 0.72 | -- | ||||

| Age <65, any private | 53.7 | (47.2 – 60.2) | -- | -- | ||

| Age <65, public only | 54.5 | (41.0 – 67.9) | -- | -- | ||

| Age <65, uninsured | 62.7 | (41.5 – 83.8) | -- | -- | ||

| Current health insurance for age 65+§ | -- | 0.70 | ||||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and private | -- | -- | 38.9 | (32.4 – 45.3) | ||

| Age 65+*, Medicare and other public | -- | -- | 32.4 | (16.9 – 47.9) | ||

| Age 65+*, Medicare only | -- | -- | 39.7 | (32.1 – 47.3) | ||

| Number of known MEPS priority conditions (excluding cancer) †† | 0.11 | 0.04 | ||||

| 0–1 | 49.4 | (41.9 – 57.0) | 29.4 | (20.4 – 38.4) | ||

| 2–8 | 58.5 | (50.6 – 66.5) | 40.1 | (35.1 – 45.1) | ||

| Years since last cancer treatment | 0.62 | 0.009 | ||||

| <1 | 56.3 | (45.5 – 67.2) | 38.7 | (29.4 – 48.0) | ||

| 1 to <5 | 53.1 | (41.6 – 64.6) | 51.0 | (38.4 – 63.6) | ||

| ≥5 ¶ | 55.9 | (46.4 – 65.3) | 37.4 | (30.5 – 44.3) | ||

| Never treated / missing | 45.9 | (32.9 – 58.9) | 24.1 | (14.4 – 33.9) | ||

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Note: Any financial sacrifices were defined as having responded yes to one or more of the individual financial sacrifice measures including reduce spending on vacation or leisure activities, delay large purchases, reduce basic spending, use savings set aside for other purposes, make a change to living situation, and/or other sacrifice because of cancer. Multivariable logistic models adjusted for age group, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, family income, employment change due to cancer (only for 18–64 years), health insurance, number of conditions, year since last cancer treatment. Bold font indicated statistically significant at alpha=0.05.

Age top-coded ≥ 85 by the MEPS.

Other race/ethnicities include Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, Asian, other race or multiple races.

Not married includes widowed, divorced, separated, or never married.

Employment change due to cancer was not considered for cancer survivors aged 65+ years because the majority was not employed.

Public insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, State Children’s Health Insurance Program, and/or other public hospital/physician coverage. TRICARE/CHAMPVA was treated as private coverage, as were employer-based, union-based, and other private insurance.

Conditions include arthritis, asthma, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease (angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, other heart condition/disease), high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke.

Years since last cancer treatment top-coded at ≥20 by the MEPS.

Discussion

Using data from a nationally representative survey, we document substantial medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Among those aged 18–64 years, nearly a quarter reported trouble with material hardship including paying medical bills, borrowing money or even filing bankruptcy due to cancer diagnosis and treatment. Over 40% had worries about their financial situation and nearly 30% could not adhere to prescribed cancer care because of cost. Among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years, 53.6% ever had any medical financial hardship, representing nearly 3.2 million cancer survivors in the US in 2016. Cancer survivors also make non-medical financial sacrifices, distinct from medical financial hardship, as they balance trade-offs under resource constraints. We found approximately 54% reported financial sacrifices in basic spending, using savings, changing living situation or changing other spending, representing 3.2 million survivors in the US. Medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices were less common in cancer survivors aged 65+ years, despite higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, likely reflecting Medicare insurance coverage, which can protect against medical financial hardship and other financial sacrifices. Nonetheless, 42.0% reported ever having had any medical financial hardship and 38.4% reported financial sacrifices, representing nearly 3.6 million and 3.3 million cancer survivors aged 65+ respectively in the US in 2016.

We identified socioeconomic factors associated with higher medical financial hardship intensity and non-medical financial sacrifices in cancer survivors, including low family income at the time of survey and education attainment. Minority cancer survivors were also more likely to report hardship intensity and sacrifices. Prior studies have documented that these factors are associated with material, psychological or any financial hardship (3,22,23). Our study contributes additional evidence related to hardship intensity and financial sacrifices for populations that have historically experienced disparities in access to cancer care and poorer outcomes following diagnosis. Additional research is needed to identify effective strategies at the national, state, health system, and provider levels to mitigate the risk of medical financial hardship and widening of disparities in cancer outcomes.

The more recently treated cancer survivors in both age groups were at greater risk of medical financial hardship and non-medical financial sacrifices, consistent with previous findings on material and psychological financial hardships with the 2011 MEPS data (3). Cancer survivors were also prone to increased use of health care for post-treatment surveillance and for the lasting effects of cancer treatment (24). Affordable and reliable insurance coverage can protect frequent health care users from financial hardship, as suggested by the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (25,26) and by consistent findings of lower medical financial hardship among elderly survivors, who have more comorbidities but near-universal Medicare coverage (3,7). Our findings related to health insurance coverage associated with hardship intensity in both younger and elder cancer survivors also demonstrate the protection effect of insurance. Since its implementation, the ACA has reduced the uninsured rate among Americans (27,28) and more specifically among cancer patients (18,19) and survivors (17). Recent data have shown that the ACA improved financial wellbeing, particularly for low- and middle-income Americans (29,30). Aspects of the ACA are undergoing revisions, such as removal of the individual mandate, introduction of short-term coverage plans (31) in the marketplace, and the addition of work requirements and cost-sharing within Medicaid in some states. These revisions may have led to an uptick in the uninsured rate in the US (32). Besides coverage, health insurance benefit design may also influence financial hardship of beneficiaries. For example, our findings that elderly survivors with Medicare and public insurance had the least hardship compared to those with Medicare only or Medicare and private insurance suggest that cost-sharing plays an important role especially when healthcare needs are elevated due to multiple health conditions. Moreover, enrollment in high deductible health plans (HDHPs) is increasing (33), and HDHP without health savings accounts is associated with delaying or forgoing health care as part of the behavioral domain of medical financial hardship (34). Future research will need to monitor the effects of ongoing changes of health policy and benefit design on medical financial hardship and non-medical financial sacrifices among cancer survivors.

Other contributors to medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices among cancer survivors include limitations in ability to work caused by cancer diagnosis and/or treatment, and subsequent income reductions and loss of employer-sponsored health insurance coverage (35,36). As our results showed, hardship intensity was most prominent among survivors who were employed and had to make cancer-related extended employment changes. Employer-level features such as health insurance offerings, availability of paid and unpaid sick leave, and workplace accommodations, can play a large role in medical financial hardship for employed cancer survivors and family members (16). Therefore, development of workplace accommodations and supportive programs at the employer-level has potential to mitigate financial hardship experienced by cancer survivors. Documenting the prevalence, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of workplace accommodations on employee health and retention will be important for future research.

Along with advancements in cancer treatment, the cost of new cancer therapies has escalated. The average price of anti-cancer drugs increased more than five-fold in the past decade (37). Meanwhile, increased patient cost-sharing has led to rising patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs (38), increasing the risk of financial hardship for cancer patients, survivors, and their families. Although most states have passed oral oncology parity laws to equalize cost-sharing for new oral cancer therapies to that of infused cancer therapies, evidence suggests that the impact of these laws is limited. They often benefit only those who already had low copayments (39–41). More targeted programs are needed to provide financial protection to those cancer patients facing high OOP. Hospital/clinic-based financial navigation programs (42–45) and patient financial assistance programs administered by patient advocacy organizations (46) (see a list of financial resources at https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/financial-considerations/financial-resources) or pharmaceutical manufacturers (47–50), may help alleviate medical financial hardship for some cancer patients and survivors. Other examples of future efforts in the healthcare system include systematic screening for financial hardship at diagnosis and tracking for financial status during treatment and follow-up care, which can be aided with electronic health record functionality and may require discussions about OOP cost and the total cost of cancer care (16). Although patient-physician cost discussions is desired by most cancer patients (51–54) and recommended by the Institute of Medicine (55) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (56), it still rarely happens due to multiple barriers such as insufficient time, limited training, lack of cost transparency, and lack of knowledge about costs of cancer care across multiple payers. Additional research and evaluation are needed to identify who in the care team should discuss these issues and when are the best times for the discussions (52,57). The factors associated with high intensity of medical financial hardship identified in this study can help prioritize limited healthcare resources to those high-risk populations who need the financial screening, navigation, and assistance programs the most.

Our study’s strengths include the recent nationally representative sample and well-designed questions to measure medical financial hardship due to cancer and its lasting effects. These strengths facilitated our ability to provide national estimates and identify risk factors for medical financial hardship intensity and evaluate financial sacrifices for the first time. Our study has limitations in common with other national survey studies including potential recall bias in self-reporting, relatively low response rate, and lack of data on the clinical features of cancers such as stage and treatment specifics. Although the questions specified experience “because of your cancer, its treatment or the lasting effects of that treatment”, there might be variations and measurement errors when survivors attributing financial hardship from cancer or other health conditions. In addition, our measures of insurance coverage, family income and number of comorbidities were current estimates at the time of the survey whereas measures of financial hardship and sacrifices were defined as ever. We were also limited by sample size to analyze important subpopulations such as racial/ethnic minorities and survivors with high deductible health plans and/or health savings accounts. The associations we observed cannot infer causal relationships. Longitudinal studies are needed to elucidate the dynamic relationships of insurance coverage, family income, and health conditions with financial hardship and sacrifice after a cancer diagnosis.

In summary, we found that cancer survivors commonly experience material, psychological, behavioral hardship, and non-medical financial sacrifices resulting from their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Extended employment change, insurance and comorbidities were associated with intensity of medical financial hardship and financial sacrifices. Future research is warranted to monitor the effects of ongoing changes in health policy and benefit design, especially in light of ongoing implementation of the ACA, on financial hardship and sacrifices among cancer survivors. Our findings highlight a need for financial intervention at multiple levels, such as patient financial navigation and availability of patient assistance programs, physician-patient communication regarding care costs, improved employer accommodation, and state and federal policy ensuring affordable health insurance for cancer survivors. These interventions are important for preventing and addressing cancer-related financial hardship among survivors and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues Drs. Elizabeth Fallon and Bob Stephens for their help in implementing factor analysis in sensitivity analyses.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109(2) doi 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A Systematic Review of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Survivors: We Can’t Pay the Co-Pay. Patient 2017;10(3):295–309 doi 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr., Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(3):259–67 doi 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27(2):80–1, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, Reeder-Hayes KE. Financial Impact of Breast Cancer in Black Versus White Women. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(17):1695–701 doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, Weaver KE, de Moor JS, Rodriguez JL, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 2013;119(20):3710–7 doi 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, Guy GP Jr., Li C, Davidoff AJ, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer 2019;125(10):1737–47 doi 10.1002/cncr.31913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan RJ, Gordon L, Zafar SY, Miaskowski C. Financial toxicity and symptom burden: what is the big deal? Support Care Cancer 2018;26(5):1357–9 doi 10.1007/s00520-018-4092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan RJ, Gordon LG, Tan CJ, Chan A, Bradford NK, Yates P, et al. Relationships between Financial Toxicity and Symptom Burden in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018. doi 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, Klosky JL, Krull KR, Srivastava D, et al. Determinants and Consequences of Financial Hardship Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018. doi 10.1093/jnci/djy120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisu M, Azuero A, Halilova KI, Williams CP, Kenzik KM, Kvale EA, et al. Most impactful factors on the health-related quality of life of a geriatric population with cancer. Cancer 2018;124(3):596–605 doi 10.1002/cncr.31048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, DiGiovanna MP, Pusztai L, Sanft T, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract 2014;10(5):332–8 doi 10.1200/JOP.2013.001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, McNees P, Pisu M. Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecol Oncol 2012;124(3):437–43 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(9):980–6 doi 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Han X, Zheng Z. Prevalence and Correlates of Medical Financial Hardship in the USA. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(8):1494–502 doi 10.1007/s11606-019-05002-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X. Medical Financial Hardship among Cancer Survivors in the United States: What Do We Know? What Do We Need to Know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018. doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidoff AJ, Guy GP Jr., Hu X, Gonzales F, Han X, Zheng Z, et al. Changes in Health Insurance Coverage Associated With the Affordable Care Act Among Adults With and Without a Cancer History: Population-based National Estimates. Med Care 2018;56(3):220–7 doi 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han X, Yabroff KR, Ward E, Brawley OW, Jemal A. Comparison of Insurance Status and Diagnosis Stage Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer Before vs After Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol 2018;4(12):1713–20 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, Han X. Changes in Insurance Coverage and Stage at Diagnosis Among Nonelderly Patients With Cancer After the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(35):3906–15 doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, Ekwueme DU, Meissner H, Soni A, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6(4):407–19 doi 10.1007/s11764-012-0221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yong AG, Pearce S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology 2013;9(2):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: Understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(2):153–65 doi 10.3322/caac.21443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lentz R, Benson AB 3rd, Kircher S. Financial toxicity in cancer care: Prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol 2019. doi 10.1002/jso.25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro CL. Cancer Survivorship. N Engl J Med 2018;379(25):2438–50 doi 10.1056/NEJMra1712502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon experiment--effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med 2013;368(18):1713–22 doi 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year. Q J Econ 2012;127(3):1057–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez ME, Zammitti EP, Cohen RA. Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2018. In: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services CfDcaP, National Center for Health Statistics, editor 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early Coverage, Access, Utilization, and Health Effects Associated With the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: A Quasi-experimental Study. Ann Intern Med 2016;164(12):795–803 doi 10.7326/M15-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu L, Kaestner R, Mazumder B, Miller S, Wong A. The Effect of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions on Financial Wellbeing. J Public Econ 2018;163:99–112 doi 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKenna RM, Langellier BA, Alcala HE, Roby DH, Grande DT, Ortega AN. The Affordable Care Act Attenuates Financial Strain According to Poverty Level. Inquiry 2018;55:46958018790164 doi 10.1177/0046958018790164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollitz K, Long M, Semanskee A, Kamal R. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief: Understanding short-term limited duration health insurance. April. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sommers BD, Clark KL, Epstein AM. Early Changes in Health Insurance Coverage under the Trump Administration. N Engl J Med 2018;378(11):1061–3 doi 10.1056/NEJMc1800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen RA, Zammitti EP. High-deductible Health Plan Enrollment Among Adults Aged 18–64 With Employment-based Insurance Coverage. NCHS Data Brief 2018(317):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Banegas MP, Han X, Yabroff KR. High-Deductible Health Plans and Cancer Survivorship: What Is the Association With Access to Care and Hospital Emergency Department Use? J Oncol Pract 2019:JOP1800699 doi 10.1200/JOP.18.00699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pisu M, Henrikson NB, Banegas MP, Yabroff KR. Costs of cancer along the care continuum: What we can expect based on recent literature. Cancer 2018;124(21):4181–91 doi 10.1002/cncr.31643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zajacova A, Dowd JB, Schoeni RF, Wallace RB. Employment and income losses among cancer survivors: Estimates from a national longitudinal survey of American families. Cancer 2015;121(24):4425–32 doi 10.1002/cncr.29510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saluja R, Arciero VS, Cheng S, McDonald E, Wong WWL, Cheung MC, et al. Examining Trends in Cost and Clinical Benefit of Novel Anticancer Drugs Over Time. J Oncol Pract 2018;14(5):e280–e94 doi 10.1200/JOP.17.00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Foster G, Whitmore H. Section 7. Employee Cost Sharing. Employer Health Benefits 2017 Annual Survey. USA 2017. p 97–129. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chin AL, Bentley JP, Pollom EL. The impact of state parity laws on copayments for and adherence to oral endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Cancer 2018. doi 10.1002/cncr.31910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Winn AN, Basch E, Keating NL. Out-of-Pocket and Health Care Spending Changes for Patients Using Orally Administered Anticancer Therapy After Adoption of State Parity Laws. JAMA Oncol 2018;4(6):e173598 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winn AN, Dusetzina SB. More evidence on the limited impact of state oral oncology parity laws. Cancer 2018. doi 10.1002/cncr.31904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison AL, Ishihara-Wong DD, Domingo JB, Nishioka J, Wilburn A, Tsark JU, et al. Helping cancer patients across the care continuum: the navigation program at the Queen’s Medical Center. Hawaii J Med Public Health 2013;72(4):116–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Linden H, Ramsey S, et al. Pilot Feasibility Study of an Oncology Financial Navigation Program. J Oncol Pract 2018;14(2):e122–e9 doi 10.1200/JOP.2017.024927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Sherman D, Shankaran V. Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient out-of-pocket spending. Am J Manag Care 2018;24(5 Suppl):S74–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Friedman NL, Mosen D, Ender AX, Chang TR, et al. Evaluation of a Novel Financial Navigator Pilot to Address Patient Concerns about Medical Care Costs. Perm J 2019;23 doi 10.7812/TPP/18-084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajurkar SP, Presant CA, Bosserman LD, McNatt WJ. A copay foundation assistance support program for patients receiving intravenous cancer therapy. J Oncol Pract 2011;7(2):100–2 doi 10.1200/JOP.2010.000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pashos CL, Cragin LS, Khan ZM. Effect of a patient support program on access to oral therapy for hematologic malignancies. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012;69(6):510–6 doi 10.2146/ajhp110383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao L, Joseph J, Santoro-Levy M, Gotlieb VK, Multz AS. Use of a Prescription-Assistance Program for Medically Uninsured Patients With Cancer: Case Study of a Public Hospital Experience in New York State. J Oncol Pract 2014;10(2):104 doi 10.1200/JOP.2013.001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zafar SY, Peppercorn J, Asabere A, Bastian A. Transparency of Industry-Sponsored Oncology Patient Financial Assistance Programs Using a Patient-Centered Approach. J Oncol Pract 2017;13(3):e240–e8 doi 10.1200/JOP.2016.017509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell A, Muluneh B, Patel R, Basch E. Pharmaceutical assistance programs for cancer patients in the era of orally administered chemotherapeutics. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2018;24(6):424–32 doi 10.1177/1078155217719585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract 2014;10(3):162–7 doi 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, Buss MK. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. Journal of oncology practice 2012;8(4):e50–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Irwin B, Kimmick G, Altomare I, Marcom PK, Houck K, Zafar SY, et al. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. Oncologist 2014;19(11):1135–40 doi 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zafar SY, Ubel PA, Tulsky JA, Pollak KI. Cost-related health literacy: a key component of high-quality cancer care. J Oncol Pract 2015;11(3):171–3 doi 10.1200/JOP.2015.004408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press; Washington, DC; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, Mulvey TM, Langdon RM Jr., Blum D, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(23):3868–74 doi 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altomare I, Irwin B, Zafar SY, Houck K, Maloney B, Greenup R, et al. Physician Experience and Attitudes Toward Addressing the Cost of Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract 2016;12(3):e281–8, 47–8 doi 10.1200/JOP.2015.007401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.