In the summer of 2017, a small plane hummed over Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Corals far below gleamed pale white in the sunlight, a stark contrast to the cerulean sea. The scene might have been gorgeous, if it wasn’t so bleak.

At least two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef has been bleached under the extreme stress of marine heat waves. Image credit: The Ocean Agency/XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

Aerial surveys by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies in Townsville, Australia, revealed that two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef had severely paled in 2016 and 2017, “bleaching” under the extreme stress of marine heat waves that can kill corals (1, 2). Summer 2017 marked the finale of the worst mass-bleaching event on record worldwide, three consecutive years of feverish ocean temperatures, driven by climate change, which affected more than 75% of reefs (3, 4).

Newspaper headlines frequently reference bleaching events. It’s no secret that reefs are in trouble. But for all the attention to bleaching, researchers are still puzzling over the cellular mechanisms that cause it.

What’s clear is that bleaching is the breakup of the tenuous relationship between a coral and the photosynthetic algae that live inside its cells. Heat stress can disrupt this relationship, causing the coral to expel its algae and to pale. New research suggests that algae, too, can be disruptive, turning on their hosts at high temperatures by switching from symbionts to parasites, which may also lead to bleaching. Coral algae have a reputation “as this friendly, only do-good kind of hero,” because they provision the coral with nutrients, says reef ecologist David Baker at the University of Hong Kong. “And I think that’s a misguided sentiment.”

New efforts in genomics are helping to further explicate the basic biology of bleaching. In 2018, researchers even used CRISPR/Cas9 to edit coral genes for the first time, potentially leading to more targeted efforts to understand the cellular mechanisms of bleaching. The mysterious roots of this ecological disaster are starting to come into full view.

Feeling Feverish

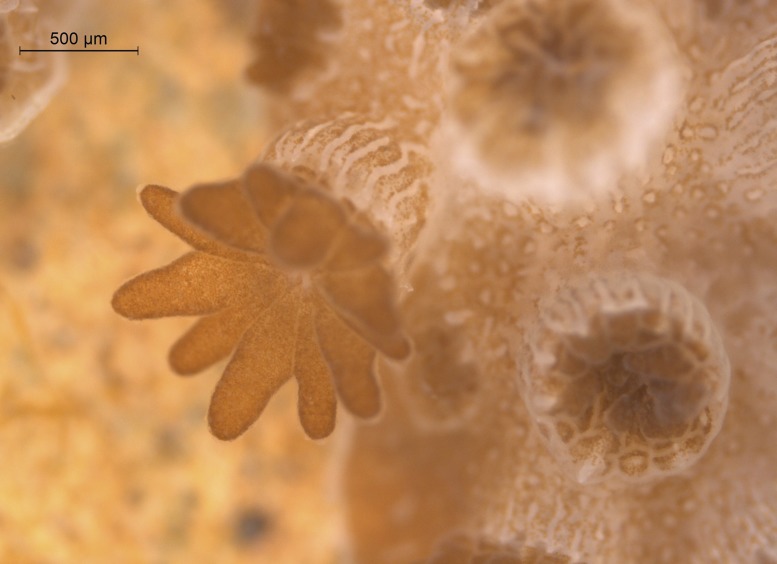

Researchers do have some idea how the bleaching process works. Corals bleach when heat stress disrupts their relationship with symbiotic algae (4, 5). Coral may look like rocks, but up close they are a living skin of soft, tentacled polyps, each anchored at its base by a hard calcium carbonate skeleton, covering over the skeletons of generations of polyps-past. Each living polyp is a sac of translucent tissue, crowned by a whorl of tentacles surrounding a central mouth, which opens to the polyp’s gut. Polyp tissue is colored by some coral pigments, as well as splotches of ruddy brown algae that live inside vacuoles in coral cells. The algae make sugars from sunlight, most of which they pass to the coral, in exchange for carbon for photosynthesis and some nitrogen in the host’s waste.

The symbiosis breaks down during stressful marine heat waves, when the coral rejects its colorful algae, bleaching white as its skeleton becomes visible through its now-translucent tissues. Bleaching can kill a coral, starving it to death, unless conditions normalize and the algae return.

Past studies suggest that one mechanism causing bleaching is damage to the algae’s photosynthetic apparatus, leading the host to reject the algae through a stress response (6). The gears of this stress mechanism begin to turn long before a coral ever bleaches, explains ecophysiologist Clint Oakley, a postdoctoral researcher at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Prolonged elevated temperatures damage the algae’s photosynthetic machinery, so that it can’t process light efficiently, and produces reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, such as hydrogen peroxide, as a damaging byproduct (7). These molecules are “little bombs basically, and whatever they contact, often a protein, they will damage it,” Oakley says. The little bombs then presumably escape out of the algal cell into the coral host cell, he says (8). To defend itself, the coral polyp rejects its algae, destroying them inside coral cells, or ejecting them back into the gut and then expelling them through the mouth (9).

Beyond that, how exactly the symbiosis falls apart at the cellular level remains unclear. Understanding the cellular mechanisms that drive the symbiosis breakdown could help predict, and perhaps even prevent, future bleaching events.

Tiny algal symbionts (brown specks) dot Acropora tenuis coral polyps. Image credit: Katarina Damjanovic (Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia).

Fair-Weather Friends

For starters, those reactive oxygen bombs may only be part of the story. Studies in the last 10 years have shown that bleaching is possible even without heat stress or reactive oxygen, says environmental genomicist Christian Voolstra at the University of Konstanz in Germany. Out in nature, when one cell invades another, their relationship is usually parasitic, he notes. Coral and algae had been held up as this ideal, mutually beneficial relationship. But building on several years of work, researchers have begun to turn a more critical eye to the symbiosis, especially the algae.

Back in 2009, Scott Wooldridge, then a researcher at the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Townsville, first suggested that algae might shift from good sharers to selfish partners in unusually warm water (10). Under the right circumstances, he suspected that algae may leech off the host without sharing nutrients.

A 2018 study in The ISME Journal provided experimental evidence for Wooldridge’s theory (11). The work found that algae don’t share well in unusually warm water, even though they keep taking resources from their star coral hosts. “The symbionts are doing good business when the water is warm,” explains Baker, who led the work. “But they are not sharing that wealth with their landlord.”

Baker used isotope tracers to follow the flow of nutrients between the algae and the host under warming conditions. He focused on corals fringing the small Belizean island of Carrie Bow Cay, a brushstroke of white sand in a swirl of turquoise water. Baker collected fragments of healthy star corals, Orbicella faveolata, from the reefs around the island, and plunked them into shallow trays of seawater on the beach, gradually heating some to create a microcosm of warming conditions, while holding other, control tanks at normal ambient temperature.

He then took a few coral fragments from each tank and put them in Nalgene bottles full of seawater, with dissolved isotope tracers. Tracers are labeled compounds, such as nitrate, that the algae convert into a biologically available form for the coral. After incubating the coral fragments with the tracers for about 10 hours, Baker tested the concentrations of these tracers in the tissues of the algae and the coral, to see how much of each compound the algae kept for themselves, and how much they shared with their host. He found that the algae’s metabolism went into overdrive in the heat, absorbing high concentrations of the tracers. But the algae didn’t share a proportionate increase in these resources with the coral. “The partnership didn’t rise together,” Baker says. “One partner accelerated, and the other was fixed.”

Nutrient availability could help explain this selfish tendency, Voolstra notes. Normally, the coral hoards most nitrogen for itself, leaving the algae nitrogen-limited and unable to metabolize all of their photosynthetic sugars, which they release into the coral cell. “This is not a friendly service by the algae,” Voolstra says, but rather a trade-off to live inside the coral.

The trade-off ends in warm water when nitrogen-fixing bacteria become more active, hence making more nitrogen available to the coral–algae symbiosis. Now the algae can metabolize their sugars rather than releasing them, Voolstra explains. Unpublished data from his lab suggest that algae may limit sugar transfer

“It’s really important to know what the mechanism is. We need to do something to try and help corals survive climate change this century.”

—Madeleine van Oppen

at high temperatures because of their higher energy needs. “Essentially coral is acting in its own interest, and the symbiont is too,” Voolstra says.

Exactly how “selfish” algae might trigger bleaching is the next open question. Some researchers, including Baker, speculate that selfish algae force the coral to draw on its own carbon reserves, which eventually run out. Then the coral can’t supply carbon to the algae, forcing these ancient ocean plants to switch from carbon-based photosynthesis to oxygen-based photorespiration, which produces the destructive little bombs of reactive oxygen molecules that damage the coral cell and can induce bleaching. The finding could be “a missing piece of the puzzle” in the mechanism of bleaching Baker says.

But other studies (7) show increased reactive oxygen species in response to heat stress, notes Virginia Weis at Oregon State University in Corvallis. Weis doesn’t necessary dispute Baker’s hypothesis as a second possible model of reactive oxygen production, but she’d like to see more evidence. Voolstra adds that some researchers even question whether reactive oxygen molecules always drive bleaching. He thinks imbalanced nutrient-sharing might contribute independently of oxygen radicals.

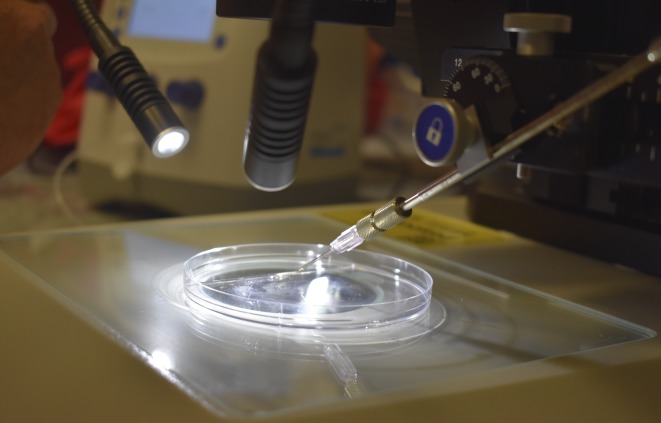

Researchers used a microinjection instrument to inject coral eggs with CRISPR/Cas9 components, seeking targeted mutations in the coral genome in hopes of understanding coral gene function. Image credit: Lorna Mitchison-Field and Amanda Tinoco (Stanford University, Stanford, CA).

Forward Thinking

Genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics are now being brought to bear to further elucidate the cellular pathways underlying the symbiosis breakup.

A July 2019 study found that 292 cnidarian genes in transcriptome analysis of the symbiotic sea anemone Exaiptasia diaphana, a close relative and emerging model organism of corals, changed their expression levels at bleaching-threshold temperatures (12). Some of the most affected genes are involved in metabolizing sugars, which the algae normally provide to the coral. That these genes are strongly affected by high temperatures suggests that sugar metabolism may be a key step to maintain the stable symbiosis, says coauthor Shinichiro Maruyama, an evolutionary biologist at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. Although not the first study to look at temperature-sensitive genes, the work supports a central role for nutrient exchange in bleaching, as in the parasitic hypothesis.

To directly decipher coral gene function, geneticists from Stanford University in Stanford, CA, along with collaborators, used CRISPR/Cas9 to genetically edit corals for the first time in 2018 (13). The researchers successfully mutated three genes as proof-of-concept, none of which is suspected to play major roles in bleaching. In a follow-up study, Stanford postdoctoral molecular geneticist and study coauthor Phillip Cleves repeated the process for bleaching-related genes. He used CRISPR to knock out a gene suspected to be involved in heat tolerance, confirming in still-unpublished experiments in 2018 that corals need the gene to survive heat.

Cleves’ motivation is to uncover the basic biology of why corals bleach, but other researchers point out that similar work could lead to more active interventions on reefs. “Once we know which [genes] are critically important in thermal tolerance, then we could think about making corals more tolerant through genetic engineering,” says Madeleine van Oppen, a coral geneticist at the University of Melbourne, Australia, and Australian Institute of Marine Science. Indeed, a recent report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in Washington, DC, summarizes more than 20 genetic, ecological, and environmental interventions to help reefs survive and become more resilient into the future. A follow-up report offers guidance to coral managers choosing between these many possible interventions, to build a local decision-making strategy (14, 15).

Given the scale of threat to reefs, it’s tempting to skip the basic research and dive straight for solutions, Weis says. Could a better understanding of the finer details actually help researchers tackle the bleaching problem?

Rescuing Corals with the Right Bacteria

Clarifying the relative roles of algae and coral in the bleaching process could offer researchers new ways to protect reefs (16).

Madeleine van Oppen, a coral geneticist at the University of Melbourne and Australian Institute of Marine Science, is culturing many strains of the bacteria that naturally live on corals. In unpublished research, she has found that some strains are good at mopping up reactive oxygen molecules. Now, van Oppen is inoculating a model anemone with some of the most efficient strains, but she says initial results have been inconclusive. A 2018 study showed promising early results, however, using bacterial probiotics to ease coral bleaching (17).

If researchers accumulate more evidence that algae become parasitic and trigger bleaching through disrupted nutrient sharing, similar studies might inoculate coral with bacteria to scavenge reactive oxygen, or offer critical nutrients when sharing breaks down in the symbiosis.

Such targeted interventions require an understanding of the cell biology that results in bleaching. “It’s really important to know what the mechanism is,” van Oppen says. “We need to do something to try and help corals survive climate change this century.”

Maybe. Genetically modified corals, for example, although incredibly complex and difficult to make, could serve as one potential conservation tool that requires basic research insights. Researchers could, in principle, target genes responsible for the breakup of the symbiosis caused by heat stress and parasitic algae. Van Oppen knows that genetically modified organisms stir controversy, and that releasing modified corals onto reefs would take much greater public acceptance and regulatory approval than exists today. “But,” she says, “that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t develop the tools.”

References

- 1.Harrison H., et al. , Back-to-back coral bleaching events on isolated atolls in the Coral Sea. Coral Reefs 38, 713–719 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooney C., ‘An enormous loss’: 900 miles of the Great Barrier Reef have bleached severely since 2016. Washington Post (2017). https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2017/04/09/for-the-second-year-in-a-row-severe-coral-bleaching-has-struck-the-great-barrier-reef/. Accessed October 29, 2019

- 3.Hughes T. P., et al. , Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association , El Nino prolongs longest global coral bleaching event (2016). https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/el-ni-o-prolongs-longest-global-coral-bleaching-event. Accessed October 29, 2019

- 5.Glynn P. W., Widespread coral mortality and the 1982-83 El Nino warming event. Environ. Conserv. 11, 133–146 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weis V. M., Cellular mechanisms of Cnidarian bleaching: Stress causes the collapse of symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3059–3066 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lesser M. P., Oxidative stress causes coral bleaching during exposure to elevated temperatures. Coral Reefs 16, 187–192 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajiboland R., Oxidative Damage to Plants (Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014), chap. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown B. E., Coral bleaching: Causes and consequences. Coral Reefs 16, S129–S138 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wooldridge S. A., A new conceptual model for the warm-water breakdown of the coral–algae endosymbiosis. Mar. Freshw. Res. 60, 483–496 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker D. M., Freeman C. J., Wong J. C. Y., Fogel M. L., Knowlton N., Climate change promotes parasitism in a coral symbiosis. ISME J. 12, 921–930 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii Y., et al. , Global shifts in gene expression profiles accompanied with environmental changes in Cnidarian-Dinoflagellate endosymbiosis. G3 (Bethesda) 9, 2337–2347 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleves P. A., Strader M. E., Bay L. K., Pringle J. R., Matz M. V., CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in a reef-building coral. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5235–5240 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , A Research Review of Interventions to Increase the Persistence and Resilience of Coral Reefs (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2019).

- 15.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , A Decision Framework for Interventions to Increase the Persistence and Resilience of Coral Reefs (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2019).

- 16.Weis V. M., Cell biology of coral symbiosis: Foundational study can inform solutions to the coral reef crisis. Integr. Comp. Biol. 59, 845–855 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosado P. M., et al. , Marine probiotics: Increasing coral resistance to bleaching through microbiome manipulation. ISME J. 13, 921–936 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]