Abstract

Investigating individual red blood cells (RBCs) is critical to understanding hematologic diseases, as pathology often originates at the single-cell level. Many RBC disorders manifest in altered biophysical properties, such as deformability of RBCs. Due to limitations in current biophysical assays, there exists a need for high-throughput analysis of RBC deformability with single-cell resolution. To that end, we present a method that pairs a simple in vitro artificial microvasculature network system with an innovative MATLAB-based automated particle tracking program, allowing for high-throughput, single-cell deformability index (sDI) measurements of entire RBC populations. We apply our technology to quantify the sDI of RBCs from healthy volunteers, Sickle cell disease (SCD) patients, a transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia major patient, and in stored packed RBCs (pRBCs) that undergo storage lesion over 4 weeks. Moreover, our system can also measure cell size for each RBC, thereby enabling 2D analysis of cell deformability vs cell size with single cell resolution akin to flow cytometry. Our results demonstrate the clear existence of distinct biophysical RBC subpopulations with high interpatient variability in SCD as indicated by large magnitude skewness and kurtosis values of distribution, the “shifting” of sDI vs RBC size curves over transfusion cycles in beta thalassemia, and the appearance of low sDI RBC subpopulations within 4 days of pRBC storage. Overall, our system offers an inexpensive, convenient, and high-throughput method to gauge single RBC deformability and size for any RBC population and has the potential to aid in disease monitoring and transfusion guidelines for various RBC disorders.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Measuring biophysical properties of individual erythrocytes, or red blood cells (RBCs), is critical to understanding hematologic diseases, as pathology often originates at the single-cell level. An essential function of RBCs, to transport oxygen to tissues, relies on the perfusion of individual RBCs through microvascular spaces oftentimes smaller in diameter than the cell itself. The average size of a typical healthy RBC under physiologic conditions is 7.5–8.7 μm in diameter and 1.7–2.2 μm in thickness.1 Oxygen is known to reach capillaries as small as 3 μm in diameter, thus requiring individual RBCs to compress their structures.2 Ease of perfusion through the microvasculature depends on multiple parameters including RBC deformability, or the degree to which a cell can contort or change shape.3–7 Normal RBCs are able to deform due to their geometry, cytoplasmic viscosity, and cell membrane elasticity.7 Volumetric flow rate can also determine the type of deformation, or conformation of individual RBCs (slipper or parachute), observed while passing through microfluidic models.8

Decreased deformability is a major manifestation of genetic hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease (SCD).9,10 Impaired RBC deformability can lead to serious pathophysiologic complications such as vaso-occlusion caused by aggregation of RBCs in the microvasculature.9–12 Understanding the bulk deformability characteristics of RBCs in an individual with SCD can lead to further advancement in the prognosis and prevention of these vaso-occlusive events which can have multiple adverse effects such as acute episodes of pain, organ damage, and even stroke.10–12 Elucidating deformability characteristics of RBC populations has implications for other hematologic diseases and areas of study in hematology as well. For example, patients with beta thalassemia major, in which a genetic mutation results in significantly reduced beta-globin production, also produce RBCs with reduced deformability.13,14 This leads to severe anemia and subsequent dependence on RBC transfusions that may alter the patient’s hemodynamic environment.15,16 Furthermore, in transfusion medicine, physical modification and degradation of RBCs (storage lesion) is known to occur when stored in blood banks due to accumulation of microparticles and alterations in the plasma membrane structure of the stored RBCs.17–20 RBCs in aerobic storage undergo significant hemolysis and loss of membrane stability in as few as 21 days.17,19,21 These issues associated with stored RBCs have also been linked to pathological reactions, posttransfusion inflammatory reactions, and various other complications.22,23 Understanding the bulk RBC deformability profile in these patients and in stored donor RBC units can help us understand the importance of RBC deformability in the context of a variety of diseases and therapeutic strategies.24

In recent years, various methods have been used to quantify the deformability of RBCs. Two commonly employed methods, the micropore filtration assay and the ektacytometry analysis, fail to accurately capture RBC deformability at the single cell level.3 Although methods such as micropipette aspiration and atomic force microscopy can measure mechanical variations at the single cell scale, their low cell throughput cannot properly describe the entire RBC population even within a small volume blood sample.25,26 Common methods to analyze bulk flow velocities of blood cells include double slit photometry, laser-Doppler velocimetry, and anemometry. These methods, however, are prone to light scattering from high cell concentrations and thus lack accuracy in image processing.27 Doppler optical coherence tomography is a modern, high resolution method that works well within larger vessels with excellent visualization of microvasculature in vivo,28 but reconstruction of cell velocity profiles within the microvasculature causes random Doppler signals to be observed.27,29 Thus, the need for an easily accessible, clinically relevant technique to analyze RBC deformability with single-cell resolution still exists.

Recently, microfluidic devices that model the microvascular environment have enabled single RBC deformability measurements. A common measurement of RBC deformability using microfluidics is transit time, or the time a cell takes to squeeze through a microcapillary channel smaller than the diameter of the cell.30,31 Transit time is analogous to the average linear velocity of a cell through the channel. However, truly high-throughput measurements have remained elusive due to technical issues such as image processing inaccuracy or aberrant signaling when reconstructing RBC velocity profiles. Therefore, microfluidic devices that mimic vessel branching, shortening, and compression coupled with a simple image analysis algorithm address this issue and provide a simple solution to accurately model flow through the microvasculature.31,32 Multiple studies have investigated the combined use of microfluidic techniques with RBC image analysis to assess cell deformability,12,33–38 but these systems focus on either single microchannels with low cell throughput or wide channels that measure bulk cell properties. Furthermore, these studies are limited due to the inability to accurately detect cell edges within microchannels that constrict individual cells. In addition, these studies do not report single cell deformability characteristics for bulk populations of RBCs in various hematologic conditions. The importance of single cell deformability over an average sample has been described in several studies39–42 but these do so in the context of cell elongation and fail to assess cell potential to traverse a microvasculature network in which blood flow is crucial for adequate circulation. Here, we introduce an in vitro microfluidic deformability cytometer to assess the deformability of single RBCs at high-throughput (Supporting Information Figure S1) with the capability to measure a distinct single cell deformability index (sDI)—defined as the average velocity in microns per second (μm/s) of a cell through a microcapillary channel—for each RBC in the context of a variety of hematologic disorders. Using this system, we are able to link the behavior of various RBC subpopulations defined by their deformability to specific disease states and treatment strategies. We couple our microfluidic device with the UmUTracker, a highly accurate particle detection program that can be run on a standard desktop, to detect the velocity profiles of large numbers of individual RBCs under various conditions as they traverse an artificial microfluidic capillary system.32 The UmUTracker is a MATLAB based computational tool that automatically detects and tracks particles by analyzing video sequences acquired by light microscopy.43 The program can both track cells over the course of their entire transit and differentiate between the edges of cells and the constricting microchannels. It can also measure RBC size simultaneously with RBC deformability and thus enable 2D analysis of both biophysical parameters for each cell. Moreover, the plug-and-play nature of this open-source system potentially allows users to adapt the particle tracking algorithm and microfluidic system to answer a variety of scientific questions.

We demonstrate that this RBC deformability cytometer is a useful and multifaceted tool capable of assessing single RBC deformability and size for of a variety of hematological conditions. Specifically, we highlight the differences in RBC sDI profiles in patients suffering from RBC disorders (ie, beta thalassemia, SCD) compared with healthy control subjects. Additionally, we highlight the interpatient variability of those afflicted with these disorders, measure the relationship between RBC size and deformability in such disorders, and track the changes in the RBC deformability profile over time in a subject with transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia and in stored packed RBCs (pRBCs).

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Microfabrication of microfluidic device

The microfluidic device used in this experiment was made from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using standard soft lithography techniques (Figure 1).44 A master mold of the microvasculature network was fabricated via SU-8 photoresist patterned onto a silicon wafer. PDMS was molded over the master mold and cured at 60°C for at least 150 minutes. Inlet and outlet ports were created by punching 0.75 mm holes through the inlet and outlet channels of the device. The device was then plasma bonded onto a clean glass slide and dehydrated for >30 minutes at 60°C prior to use. The microchannels have dimensions of 5.89 ± 0.08 μm (mean ± SD) wide by 13.3 μm tall by 130 um long and are meant to simulate a capillary bed in vivo. There is a total of 64 microcapillary channels in the device. Large bypass channels prevent flow rate oscillations in the microchannels due to obstruction of any of these microchannels.

FIGURE 1.

A schematic of the microfluidic setup integrated with automated image analysis using the UmUTracker MATLAB program. RBCs diluted in PBS are infused into the microfluidic device at a constant 1 μL/min flow rate and their transits through the microcapillary channels 5.89 μm in width are recorded at 20× magnification (A). The entire microfluidic device is shown at 4× magnification (A2). RBCs traversing the microchannels over 4 frames captured at 9.6 fps are highlighted in blue for visual convenience (B1). Depiction of the UmUTracker image analysis process shows the same 3 RBCs within the microfluidic device over time as they traverse the microchannel. Images are shown after a hologram normalization setting has been applied. The particle tracking algorithm places green dots on each RBC, labels each with an ID number, and places each within a template radius. The RBC velocity within the microchannel is used to measure the sDI distribution of a population of RBCs (B2)

2.2 |. Healthy adult RBCs, SCD, beta thalassemia

Fresh samples of blood were taken from healthy adult volunteers, subjects with SCD, and a beta thalassemia major patient via venous blood draw after each gathering patient’s informed consent (Emory University IRB00105125). All SCD patients had a Hemoglobin SS (Hb SS) genotypic presentation. In each condition, 3 mL of fresh blood was collected into phlebotomy tubes of sodium citrate.45 For the beta thalassemia patient, blood was collected over a 37-day span that included 2 distinct transfusion events. Blood samples were centrifuged first under low acceleration at 150g for 15 minutes to isolate RBCs from other blood components. RBCs were washed with phosphate buffered solution (PBS) and centrifuged again at 201g for 10 minutes to ensure complete isolation of RBCs.

2.3 |. Artificially stiffened RBCs via glutaraldehyde

Samples of isolated RBCs from health volunteers were chemically stiffened using glutaraldehyde. 5 μL of 25% w/w glutaraldehyde in H2O (Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted with 3.115 mL of PBS. 1 mL of dilute glutaraldehyde was added to 1 mL of isolated RBCs to create a final concentration of glutaraldehyde of 0.04%–0.08%. The mixture was allowed to incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature (22°C), and the cross-linking reaction was stopped via addition of about 5 mL of GASP Buffer (1% w/v bovine serum albumin [BSA], 9 mM Na2HPO4, 1.3 mM NaH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4). Stiffened RBCs were isolated again through centrifugation at 150g.

2.4 |. Stored packed red blood samples

Three samples of pRBCs were isolated from donations of healthy individuals. Written informed consent was obtained from each volunteer (Emory University IRB 00010018). A 500 mL (±10%) whole blood was drawn by peripheral venipuncture into CPD-containing blood collection sets (Fenwal, Inc., Lake Zurich, Illinois), stored at 2°C–6°C for 1–3 hours, leukoreduced using integral filters, and then centrifuged at 4500 RPM for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet RBCs. Platelet-rich plasma was removed, the residual RBC pellets were mixed with additive solution, and the resulting pRBC units were transferred to a refrigerator at 2°C–6°C. Sampling was performed by first gently agitating units. Small aliquots of 1–3 mL were drawn from each bag through a port using a 21-gauge needle. Each experiment was performed on days 1, 5, 8, 12, 15, 20, 26, and 28 from being packed and stored. Bags were returned to refrigerated storage between sampling time points. Isolated RBCs were stored at 4°C for 4 weeks.

2.5 |. Microfluidic experiments

Isolated RBCs were then diluted in PBS with a final volume: volume ratio within the range of 1:200–1:100. The mixture was drawn into a 1 mL syringe (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) with microfluidic tubing attached. A 20 mg mL−1 solution of BSA in PBS was injected to perfuse through and block the microfluidic network to prevent nonspecific adhesion of RBCs to the microfluidic channel walls.46 The BSA solution was allowed to incubate within the device for >30 minutes at room temperature (22°C). A syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) infused RBCs at a fixed volumetric flow rate of 1 μL/min into the microfluidic device. Video clips in “.avi” format of cells passing through the microcapillary network were taken using a Retiga EXI Mono Camera fitted onto an inverted Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U. The camera had a frame rate of around 9.7 fps and an exposure time of 30 microseconds (μs).

2.6 |. Computational analysis—UmUTracker

Velocity distributions of RBC perfusion through the microfluidic capillary network were measured using the UmUTracker MATLAB program.18 The UmUTracker directly processed video footage and calculated the position, major axis length, and minor axis length of each cell that traversed the device microchannels. In the program code, 2D lateral positions of particles are calculated with an algorithm based on isosceles triangle transforms. The UmUTracker can be run on a standard desktop computer with MATLAB v2017a or higher installed with the Image Processing and Parallel Computing toolboxes.

For each experiment, a video of cells traversing the microfluidic channels was loaded onto the user interface of the tracking software (Supporting Information Figure S2). A specified region of interest, the bounds of which were the edges of the microchannels of the microfluidic device, was selected (Supporting Information Figure S3). The threshold at which cells are detected is iteratively determined by the user and set through parameters including an edge detection correction factor, a pixel intensity threshold, and a morph kernel size. For 2D light microscopy videos, a hologram normalization setting is chosen. This casts a set subinterval of images as a “moving background” that refreshes. A “blob” detection algorithm is chosen in which particles that have near circular or elliptical characteristics, such as cells compressed through microfluidic channels, can be detected as particles. Cells entering the frame are interpreted as variations in pixel intensity, and an “edge detection” response threshold can be manually adjusted to accurately recognize each individual cell in a film and filter out static noise. The output of the program is a list of tracks in order of detection for each individual cell with the frame number, position along the microfluidic channel labeled as the “x” axis, and “y” position, both based on a predetermined nanometer to pixel ratio. Upon starting the tracking program, a pop-up MATLAB frame-by-frame playback of the video with marked tracked positions of each cell was present.

Each experiment captured and analyzed video footage lasting 6–10 minutes. Data from all individual cell tracks were then compiled. For each individual cell track, an average velocity over the course of its transit was found through the product of 3 values: the difference in its final and initial tracked position along the microfluidic channel axis in microns, the inverse of the number of frames the cell was captured in frames−1, and the frame rate of the camera being used in frames per second. False positives of tracked cells were prone to occur with poor microscope resolution, lighting, or adequate initial cell contrast to the background of the microfluidic bed. Thus, particles that were tracked for <50 μm of linear travel were considered to produce a poor “edge response” and thus discarded from cell counts. The effective diameter or cell size of an RBC was calculated through the average of its major and minor axis length. Velocity histograms were created for each condition, and density-colored scatter plots (DCSPs) for particle velocity vs cell diameter were created as well.

2.7 |. Code availability

The open-source particle tracking software used in this manuscript can be found at https://github.com/rmannino3/DeformabilityCytometer.

3 |. RESULTS

In order to validate the ability of our system to determine a given RBC population’s profile of single sDIs, we perfused various populations of RBCs that were artificially stiffened and known to be less deformable than healthy control cells through our microfluidic system. This included samples from 6 healthy adult volunteers, 6 SCD patients on hydroxyurea (HU), 1 SCD patient not on HU, RBCs from 6 healthy donors that were chemically stiffened with dilute glutaraldehyde, from pRBCs stored under refrigeration at 4°C, and from a beta thalassemia patient. In order to characterize the clinical impact of specific deformability-discriminated subpopulations of RBCs, metrics of deformability histogram shape were calculated. For each RBC sDI distribution curve, a relative measure of shift from a Gaussian distribution and an assessment of tail behavior, respectively known as skewness and kurtosis, were calculated. Positive values of skewness indicate a left shifted (ie, contains subpopulations of less deformable cells) distribution, and negative values indicate a right-shifted behavior (ie, contains subpopulations of more deformable cells). Positive kurtosis indicates a “heavy-tailed” distribution that is more concentrated toward a single peak (ie, contains few subpopulations of cells with different deformability characteristics), whereas negative kurtosis suggests a flatter spread of values (ie, contains subpopulations of cells with different deformability characteristics). Zero values of the 2 measures are references for Gaussian behavior. In addition, each sDI distribution is broken into 3 sections that characterize relative deformabilities within our system: sDIs above 200 μm/s (microns per second) are considered “high” in value and thus indicate high deformability, and those that fall below 150 μm/s are “low” and indicate more rigid behavior. These thresholds are the rough boundaries of ±1 SD from the average sDI of the 6 control or healthy samples.

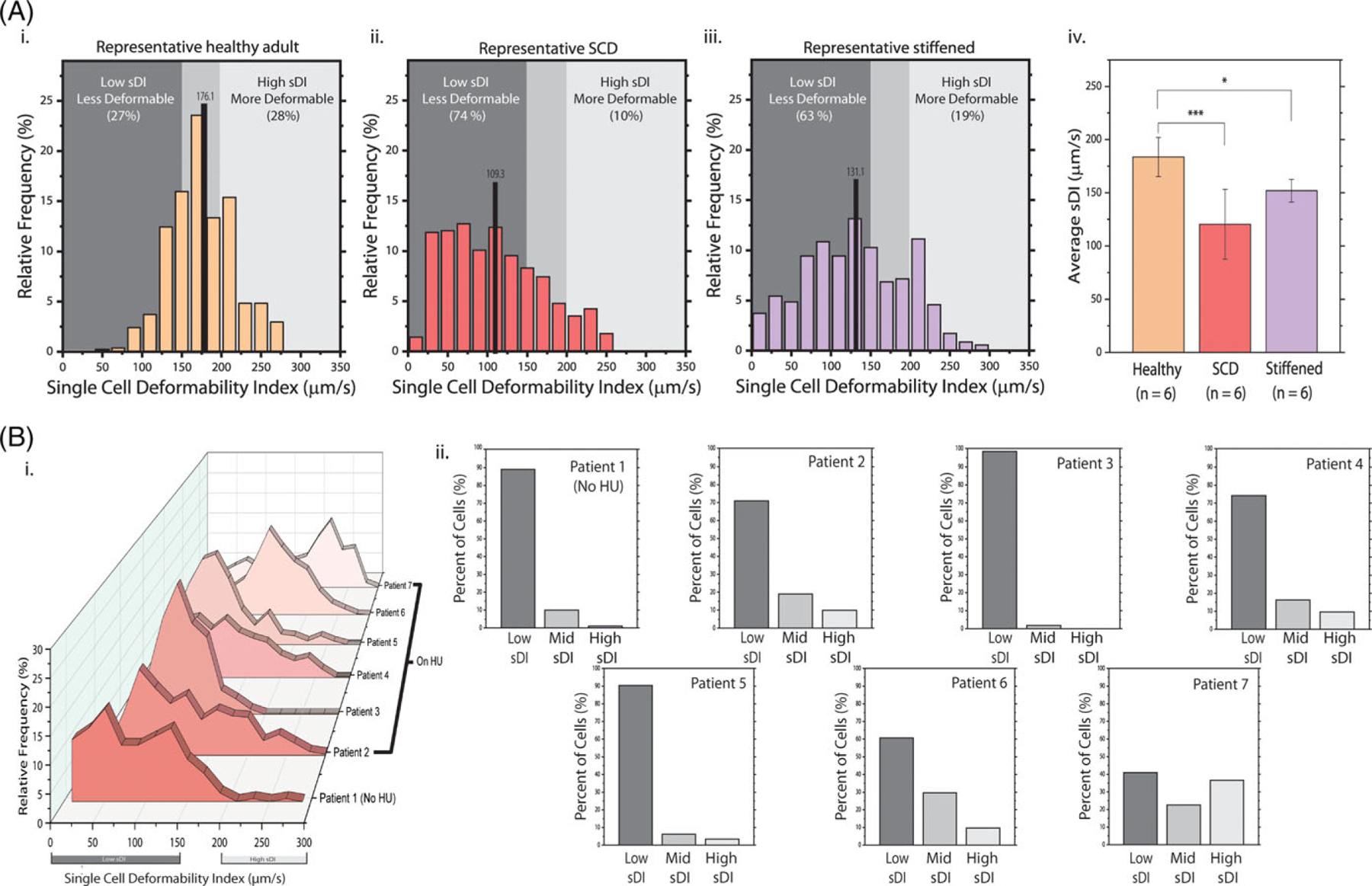

Cell counts >250 were recorded in each experiment for fresh RBCs from healthy adults, SCD patients, and glutaraldehyde-stiffened cells as positive controls. Representative histograms of each condition (healthy, SCD, stiffened) have varied distributions (Figure 2). The average sDI of the healthy volunteer was 176.1 (SD ± 40.7) μm/s, and had a skewness and kurtosis of 0.1 and −0.09, respectively. For the SCD patient, the average sDI was 109.3 (SD ± 60.2) μm/s with a skewness and kurtosis of 0.47 and −0.67. For the glutaraldehyde treated cells, the average sDI was 131.1 (SD ± 62.9) μm/s with a skewness and kurtosis of 0.11 and −0.86. When compared with those for healthy RBCs, the sDI distribution curves for glutaraldehyde-stiffened RBCs (as positive controls) resulted in an expected “left shift” and decrease in the mean sDI). In the case of the healthy volunteer, a small, near zero skewness and kurtosis indicates a near Gaussian distribution, whereas the larger positive skewness and larger negative kurtosis of the representative SCD histogram indicates a left shifted, wider spread behavior. For the 3 conditions respectively, the percentage of cells in each sample that fell into the “Low sDI” range were 27%, 74%, and 63%, and the percentage of cells that fell into the “High sDI” range were 28%, 10%, and 19%.

FIGURE 2.

sDI distributions confirm less deformable RBC subpopulations in SCD RBCs and in artificially stiffened RBCs and SCD patients, in particular, exhibit significant inter-patient variability of RBC deformability. (A) Representative sDI histograms of healthy, SCD, and glutaraldehydestiffened RBCs are shown. Healthy RBCs (1 donor, 540 cells) demonstrate sDIs distributed toward an average value of 176.1 (SD ± 40.7) μm/s, and 45% of sDIs are in the mid-range (i). A small magnitude skewness of 0.1 and kurtosis of −0.09 indicate a near-Gaussian distribution of values. The SCD RBCs (1 donor, 567 cells) from a patient on HU had both a lower average sDI of 109.3 (SD ± 60.2) μm/s and a significantly left-shifted nonnormal distribution as evidenced by a large positive skewness of 0.47 and large negative kurtosis of −0.86 (ii). The emergence of prominent subpopulations is most notable at lower velocities, as 74% of cells are within the low sDI range. The sDI profile of glutaraldehyde-treated RBCs (1 donor, 350 cells) had an average of 131.1 (SD ± 62.9) μm/s, a skewness of 0.11 and a kurtosis of −0.86 (iii). The mean sDI’s across 6 independent experiments for each condition are compared using a Student’s ttest on means (iv). All SCD samples were from patients on HU. The rough boundaries of ±1 SD from the average sDI of the 6 control or healthy samples dictate the middle range of sDIs. (B) the RBC sDI distributions for 7 SCD patients demonstrate significant interpatient variation and the emergence of prominent heterogeneous RBC subpopulations (i). The average sDI from a patient not on HU (patient 1) is 83.0 (SD ± 51. 4) μm/s with a “left shifted” peak sDI and wide spread as indicated by a skewness of 0.44 and a kurtosis of −0.33. The overall average sDI of all 6 patient samples on HU is 120.5 (SD ± 32.9) μm/s with relatively “right shifted” peak sDIs. The sDI distribution skewness for each patient on HU is 0.54, 0.27, 0.47, 1.07, 0.01, and −0.33, and respective kurtosis was −0.66, −0.07, −0.67, 1.07, −0.16, and 0.−84. Percentages of cells in each sDI regime (low, middle, and high) show large distributions of rigid cells within most patient’s RBC sample (ii)

The distributions of SCD RBCs, which are well known to have increased rigidity, lie to the left relative to normal RBCs. The spread of normal RBCs is also more contained around the mean than is the spread for SCD. The overall mean for 6 experiments each of normal, SCD, and chemically stiffened RBCs was 183.5 (SD ± 18.3) μm/s, 120.5 (SD ± 32.9) μm/s in SCD, and 156.9 (SD ± 10.6) μm/s, respectively. Differences in the overall average were statistically significant between normal RBCs and SCD RBCs (P < .001) and between normal RBCs and chemically stiffened RBCs (P <.05). The sDI distribution of RBCs from the SCD patient not on HU was 83.0 (SD ± 51.4) μm/s with a left shifted distribution relative to that of the other patients on HU (Figure 2). For each SCD patient, the skewness was 0.44, 0.54, 0.27, 0.47, 1.07, 0.01, and −0.33, and the kurtosis was −0.33, −0.66, −0.07, −0.67, 1.07, −0.16, and −0.84. The majority of SCD patients exhibits left shifted (positive skewness) distributions and wide value spread (negative kurtosis). Characteristic population distributions in both the SCD and chemically stiffened histograms have larger widths, as suggested by lower kurtosis values, and lower averages relative to that of normal RBCs.

For all conditions, cell populations have notable deviations in deformability from the mean value in either direction. Therefore, regarding RBC deformability in SCD, while the mean sDI for SCD RBCs was expectedly decreased, the sDI distribution was clearly nonnormal, indicating the existence of heterogeneous RBC subpopulations with different deformabilities. These heterogeneous sDI distributions were observed in multiple SCD patients, including those on HU and not, although patients on HU exhibited RBCs subpopulations with relatively higher sDIs.

The sDI profiles of donated pRBCs as a function of storage time was determined using this system. The averages for the presented sample show a decreasing trend in mean value over the course of 28 days (Figure 3). Distributions of these velocities also shift with a decreasing trend over time, with peaks lying successively at lower velocities (Supporting Information Figure S4). The overall averages of the means of the 3 samples also show a decreasing trend for the same days. Performing an exponential decay regression on these data points yields a sharp downward curve (R2 = 0.98). The largest drop in mean single cell deformability occurred in the period between days 15 and 20 in which the sDIs were 135.4 (SD ± 3.0) μm/s and 100.7 (SD ± 21.0) μm/s respectively. The mean sDI entered the “Low sDI” region between days 8 and 12. These results also indicate that while stored pRBCs showed an expected drop in mean sDI over time, our system detected notable shifts in peak sDI over only 4-day intervals. The shifting of subpopulations across sDI regimes for the given pRBC unit is further quantified in the final panel of Figure 3A, in which the percentage of cells in a sample within the “Low sDI” region rises sharply over time. In addition, analysis of the skewness and kurtosis of each stored unit’s data does not show notable trends.

FIGURE 3.

sDI distributions fluctuate significantly in healthy RBCs in storage and in thalassemia patients after blood transfusions. (A) RBC sDI distributions extracted from a single bag of refrigerated pRBCs shows distinct decreasing peak sDIs from days 1 to 28 of storage (i). analysis of skewness and kurtosis for these distributions does not reveal notable trends. The most prominent decrease occurred between days 15 to 20, when the average sDIs across 3 stored pRBC units were 135.4 (SD ± 3.0) and 100.7 (SD ± 21.0), respectively (ii). After 12 days of storage, the average sDI of the 3 samples enters the low SDI regime. Quantification of cell percentages within each sDI range shows a sharp increase in distribution of low sDI cells over time in storage (iii). (B) RBC sDI distributions from a single beta thalassemia patient over 37 days are shown with times of transfusions indicated in red (i) whereas average RBC sDI values (right) do not indicate significant changes before or after transfusions (ii), analysis of the entire RBC sDI distributions reveal more obvious changes at the RBC subpopulation level. Specifically, an increase in the number of more deformable RBCs (right shift) is observed immediately after both transfusions (red), as indicated by shifts to more negative values of skewness across each respective transfusion (0.49 to −0.1 over transfusion 1 and −0.72 to −0.82 over transfusion 2). This more deformable subpopulation steadily decreases throughout the rest of the cycle (left shift)

The sDI profiles of RBCs taken from a subject with transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia were assessed over 2 transfusion cycles (Figure 3). The sDI data demonstrate that each time the beta thalassemia patient was transfused, the peak sDI shifted to the right, as indicated by larger negative values of skewness (0.49 to −0.1 and − 0.72 to −0.82, across each respective transfusion). The sDI peak gradually decreased over the course of the transfusion cycle, while the mean sDI exhibited minimal change over time, indicating that RBC subpopulations of different deformabilities clearly exist but require high-throughput single cell measurements, and not bulk ensemble measurements such as ektacytometry, to detect and track. sDI distribution skewness and kurtosis values across the transfusion events oscillated around zero, a sign of relatively normal behavior.

Along those lines, we also leverage the capability of our system to simultaneously measure RBC size as well as deformability and again, apply this to healthy RBCs, SCD RBCs, and beta thalassemia RBCs. DCSPs display the sDI of each RBC on 1 axis and the corresponding cell size of the RBC on the other axis, creating a 2D map similar to those used in flow cytometry (Figure 4). Each DCSP is divided into 4 Quadrants that categorize the deformability and size relationship. Splitting each sample into 4 quadrants allows for simple visual categorization of cell subpopulations. Cells with sDI values >150 indicate normal or highly deformable behavior, and these cells are found in Quadrants I and II. Cells with sizes of >5 U are considered normal and are found in quadrants I and IV. In total 95% of control healthy cell sizes across all 6 samples was in the range of the 5-unit threshold or greater. Healthy individuals show narrow, condensed distributions of RBC size for the given distribution in sDI, and their DCSPs are contained within quadrant I. SCD patient samples have a larger and wider spread in RBC size values that are not correlated with their respective sDI distributions and as such, SCD patient RBCs exhibit a wide range of deformability and size. The beta thalassemia patient samples show increases, or rightward shifts, in effective diameter distribution immediately following a transfusion event (days 2 and 23). Specifically, before transfusion in beta thalassemia, a low sDI and small cell size RBC subpopulation dominates, and immediately after transfusion, a second high sDI, larger cell size, donor-derived RBC subpopulation is detected, which diminishes over time until the next transfusion. This idea is depicted as a noticeable shift of the DCSP point density from quadrants III and IV to quadrant I. This trend is further quantified in the final panel of Figure 4, in which the percentage of cells in quadrant I rises sharply following each transfusion event. Interestingly, over the course of transfusion cycles, mean sDI RBC exhibited minimal change.

FIGURE 4.

DCSPs of effective RBC diameter and sDI in various hematologic contexts illustrate RBC subpopulations and their shifts over time. DCSPs of RBC sDI vs effective cell diameter or cell size for 3 healthy individuals show narrow and condensed spreads of both RBC sDIs and sizes (A). These spreads are contained mostly within quadrant I, a region of normal to high sDI and normal cell size. An SCD patient not on HU has a much wider distribution of sDI vs cell diameter; the bulk of the spread lies within quadrants III and IV, regions of lower sDI (B). Wide spread of subpopulations is also observed in 2 other DCSPs for SCD patients on HU. DCSPs for a beta thalassemia patient tracked over the course of 2 transfusion cycles show significant rightward intensity shifts in cell size distribution immediately following transfusion events (days 2 and 23) and gradual leftward shifts in between the transfusion events (C). Quantification of cell percentages in each quadrant shows a shift in subpopulation density from quadrants III and IV to quadrant I following transfusion events (D)

4 |. DISCUSSION

Here, we have demonstrated that an accessible computational method, which can be easily operated on any desktop computer, paired with a robust microfluidic device has the high-throughput capability to detect distinct RBC subpopulations at the single cell level, while also measuring RBC size. Moreover, single cell measurements of RBC deformability vs RBC size using our system enables quantitative analysis of how these biophysical properties relate over time in RBC disorders including SCD, beta thalassemia, and the storage lesion of pRBCs.

Specifically, we have demonstrated significant variability in the distributions of normal RBCs vs those RBCs of SCD patients and RBCs that are chemically stiffened. sDI RBC curves detect subpopulations of cells that exist within bulk samples of RBCs that a simple average cell deformability cannot detect. This average value of deformability could be gauged at the bulk scale through the use of ektacytometry,10,47 but examining single cell distributions could provide information on how specific subpopulations of RBCs may cause disease complications, for example, such as vaso-occlusive crises in SCD. It has been previously shown that patients on HU therapy exhibit lower rigidity in the RBC membrane than of those patients not on HU, albeit still lower than normal controls.48,49 The sample from a patient not on HU shows an expected mean sDI that is <1 SD from than the average sDI of 6 SCD samples on HU. The nonHU sample also has an sDI distribution that is strongly left shifted with a skewness of 0.44, and a large percentage (89%) of cells that fall into the “Low sDI” range, indicating the existence of a significantly less deformable subpopulation of cells. Our measurements beg the question of whether these subpopulations of low sDI RBCs may play a role in the pathophysiology of SCD, something that cannot be determined by measuring average bulk deformability alone using currently available techniques; ongoing studies will assess that issue.

Furthermore, this system is capable of directly influencing techniques and treatments in transfusion medicine. Our results regarding the change in deformability over time of pRBCs reveal an exponential decay of RBC deformability that leads to rapid decreases in deformability and complete occlusion of our system after ~4 weeks. This finding challenges the currently accepted maximum storage time of pRBCs of 42 days,50 and is supported by numerous studies showing that even after 21 days, RBCs in storage can undergo significant breakdown and loss in membrane functionality, leading to a potential list of complications within the patient receiving a transfusion.17,19,21,51 Our results suggest that a sharp decrease in RBC deformability occurs between 2 and 3 weeks of refrigerated storage. The variation in between stored bags between these 2 days also became more apparent with an increase in SD (SD ± 3.0 μm/s to SD ± 21.0 μm/s). Skewness and kurtosis data for each of the 3 U fluctuates largely and shows neither a correlation between units nor trends over time. Furthermore, the subtle variability in data between donors suggests that each bag of stored RBCs may experience a unique rate of internal degradation with specific RBC subpopulations that may play dominant roles in potential adverse effects of transfusion. Accordingly, assessments of single cell deformability profiles of individual bags of stored RBCs might provide insight into how to optimize blood transfusion safety, and an accessible and simple microfluidic technique provides a quick method to gather large quantities of data. Going forward, we will conduct further studies with a greater sample size to investigate this.

Although numerous studies have applied microfluidics to study RBC mechanics, ours is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to conduct high-throughput studies of RBCs in disease states that measure single RBC deformability vs size. Although an elegant study applying microfluidics to measure single cell deformability was recently published, the focus was on normal and not diseased RBCs.52 Indeed, our work now puts what has been discussed in the literature for decades, the existence of biophysically altered RBC subpopulations, and places those concepts in a quantitative, “big data” format using flow cytometry-like plots, or DCSPs. To characterize both size and sDI, we divided each DCSP into 4 Quadrants. In our system, beta thalassemia patients exhibit a low sDI, small RBC cell size population found primarily in quadrants III and IV, which is not unexpected given the microcytic, low deformability nature of thalassemia RBCs. However, immediately after a pRBC transfusion, our system appropriately detects 2 RBC biophysical subpopulations of RBCs—the thalassemia recipient RBCs and the healthy donor-derived RBCs, which are larger and more deformable. Skewness and kurtosis data of the individual indicate relatively normalized distributions as each oscillates around a zero-value for all days. Immediately following transfusions on days 2 and 23, values in distribution skewness become more negative (0. 49 to −0.10 and − 0.72 to −0.82, respectively) and indicate right shifts in distribution. The center of density in the DCSP points following both transfusion events shifts toward quadrant I. After the first transfusion event, a dense subpopulation of cells remains within quadrant III. This observation confirms the expected presence of a new, biophysically distinct subpopulation of RBCs that are more deformable and larger sized. These results suggest the potential of this system to determine the lifetime of transfused red cells to better personalize transfusion schedules for transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients, and to aid in the identification of specific donors for specific patients. It has been suggested that transfused RBC deformability determines transfusion-induced changes in the recipient’s RBC deformability,53 but our method quantifies this idea through 2 distinct biophysical parameters at the single cell level. Both populations are easily detected with DCSPs, and the simplicity of our system now opens the possibility for accurate tracking of these RBC subpopulations over time. These high-resolution DCSPs, in turn, will allow for detection and quantitative tracking of cellular subpopulations and determination of their clinical relevance, similar to what is done for leukemia, in which flow cytometry is now an integral part of patient care and diagnosis.54,55 We conjecture that for transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients, our method with its flow cytometry-like DCSPs may enable detection of which specific donors are best for specific individual patients.

Our combined microfluidic/image analysis system can also correlate an individual RBC’s effective diameter with its deformability. Healthy volunteers with normal blood show condensed distributions of both size and deformability. When compared with healthy volunteers, SCD patients have wider distributions in size and overall lower values of sDI. Further research is needed to correlate specific subpopulations, such as those with relatively large sizes and small sDIs, to certain conditions experienced within hematological diseases. There is a lack of a trend between SCD patients to be observed, and thus a DCSP of sDI and effective diameter for a given patient’s RBC populations can contribute to a personalized deformability signature. The beta thalassemia patient’s RBC population samples show shifts to higher values in both sDI and size distributions. These distributions appear to decline in tandem in the period in between transfusion events. Data on effective diameter and sDI can have significant impacts in transfusion medicine if it is found that the biophysical properties of stored RBCs at the time of transfusion have a correlation to the deformability and size metrics of the RBCs of patients receiving the blood following the transfusion event. Every system has limitations, and in our case, accuracy in the marked values of RBC size can be compromised due to several parameters in the setup, including microscope light intensity, contrast of cells to their background due to focus of the camera, the thickness of the PDMS device, and the edge detection correction factor for blob detection that is manually set through the user interface of the UmUTracker. Videos that have poor cell contrast will require a higher threshold for edge detection, potentially leading to detected cell diameters that lie further than the actual cell diameters. Calculations of the distribution of cell size within each video analysis, however, will remain consistent with the specified settings.

Overall, our novel combined microfluidic/portable image analysis system demonstrates the high-throughput capability to detect distinct RBC subpopulations, at the single cell level, of different deformabilities in SCD, beta thalassemia, and aging stored RBCs. We address the problem of accurate cell edge detection at the microchannel wall and represent the variance in single cell deformability across various conditions through the scope of the smallest channels in microvasculature flow. This heterogeneity indicates that, in these disease states, RBC deformability cannot be fully characterized with mean or bulk biophysical measurements such as those obtained with ektacytometry. Examination of sDI distributions to characterize important RBC subpopulations may involve comparison of the distribution skewness and kurtosis relative to normal, healthy individuals, but a much larger sample size is needed to define a skewness or kurtosis “standard range” based on healthy individuals. Ongoing studies will determine how changes in sDI profiles are associated with clinical events and different therapies, the biological significance of these RBC subpopulations with varied deformabilities, and the underlying mechanisms for these differences.

Supplementary Material

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: 2 P01 HL 086773-06A1R01 HL095479-06, R01HL121264, R21MD011590, R01HL140589

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nothing to report.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diez-Silva M, Dao M, Han J, Lim C-T, Suresh S. Shape and biomechanical characteristics of human red blood cells in health and disease. MRS Bull/Mater Res Soc. 2010;35(5):382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen RT, Fung YC. Effect of velocity distribution on red cell distribution in capillary blood vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1978;235(2): H251–H257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sosa JM, Nielsen ND, Vignes SM, Chen TG, Shevkoplyas SS. The relationship between red blood cell deformability metrics and perfusion of an artificial microvascular network. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2014; 57(3):291–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stadler A, Linderkamp O. Flow behavior of neonatal and adult erythrocytes in narrow capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1989;37(3):267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart J. Erythrocyte rheology. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38(9):965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsyth AM, Wan J, Ristenpart WD, Stone HA. The dynamic behavior of chemically “stiffened” red blood cells in microchannel flows. Microvasc Res. 2010;80(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohandas N, Clark MR, Jacobs MS, Shohet SB. Analysis of factors regulating erythrocyte deformability. J Clin Investig. 1980;66(3):563–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tahiri N, Biben T, Ez-Zahraouy H, Benyoussef A, Misbah C. On the problem of slipper shapes of red blood cells in the microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 2013;85:40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Dao M, Lykotrafitis G, Karniadakis GE. Biomechanics and biorheology of red blood cells in sickle cell anemia. J Biomech. 2017;50: 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabai M, Detterich JA, Wenby RB, et al. Deformability analysis of sickle blood using ektacytometry. Biorheology. 2014;51(0):159–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripette J, Alexy T, Hardy-Dessources M-D, et al. Red blood cell aggregation, aggregate strength and oxygen transport potential of blood are abnormal in both homozygous sickle cell anemia and sickle-hemoglobin C disease. Haematologica. 2009;94(8):1060–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alapan Y, Matsuyama Y, Little JA, Gurkan UA. Dynamic deformability of sickle red blood cells in microphysiological flow. Dent Tech. 2016; 4(2):71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dondorp AM, Chotivanich KT, Fucharoen S, et al. Red cell deformability, splenic function and anaemia in thalassaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999; 105(2):505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangalani M, Lokeshwar MR, Banerjee R, Nageswari K, Puniyani RR. Hemorheological changes in blood transfusion-treated beta thalassemia major patients. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1998;18(2–3):99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barshtein G, Arbell D, Yedgar S. Hemodynamic functionality of transfused red blood cells in the microcirculation of blood recipients. Front. Physiol 2018;9:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barshtein G, Goldschmidt N, Pries AR, Zelig O, Arbell D, Yedgar S. Deformability of transfused red blood cells is a potent effector of transfusion-induced hemoglobin increment: a study with beta-thalassemia major patients. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(9):E559–e560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Roa M, del Carmen Vicente-Ayuso M, Bobes AM, et al. Red blood cell storage time and transfusion: current practice, concerns and future perspectives. Blood Transfus. 2017;15(3):222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godin C, Caprani A. Effect of blood storage on erythrocyte/wall interactions: implications for surface charge and rigidity. Eur Biophys J. 1997;26(2):175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin O, Crettaz D, Tissot J-D, Lion N. Microparticles in stored red blood cells: submicron clotting bombs? Blood Transfus. 2010;8(Suppl 3):s31–s38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z, Zheng Y, Wang X, Shehata N, Wang C, Sun Y. Stiffness increase of red blood cells during storage. Microsyst. Nanoeng 2018;4:17103. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin O, Delobel J, Prudent M, et al. Red blood cell-derived microparticles isolated from blood units initiate and propagate thrombin generation. Transfusion. 2013;53(8):1744–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almizraq RJ, Seghatchian J, Acker JP. Extracellular vesicles in transfusion-related immunomodulation and the role of blood component manufacturing. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;55(3):281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jy W, Ricci M, Shariatmadar S, Gomez-Marin O, Horstman LH, Ahn YS. Microparticles in stored RBC as potential mediators of transfusion complications. Transfusion. 2011;51(4):886–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomaiuolo G. Biomechanical properties of red blood cells in health and disease towards microfluidics. Biomicrofluidics. 2014;8(5): 051501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa KD. Single-cell elastography: probing for disease with the atomic force microscope. Dis Markers. 2003;19(2–3):139–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skoutelis AT, Kaleridis V, Athanassiou GM, Kokkinis KI, Missirlis YF, Bassaris HP. Neutrophil deformability in patients with sepsis, septic shock, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2000; 28(7):2355–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bukowska DM, Derzsi L, Tamborski S, Szkulmowski M, Garstecki P, Wojtkowski M. Assessment of the flow velocity of blood cells in a microfluidic device using joint spectral and time domain optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2013;21(20):24025–24038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zotter S, Pircher M, Torzicky T, et al. Visualization of microvasculature by dual-beam phase-resolved Doppler optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2011;19(2):1217–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wojtkowski M. High-speed optical coherence tomography: basics and applications. Appl Opt. 2010;49(16):D30–D61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rendell M, Luu T, Quinlan E, et al. Red cell filterability determined using the cell transit time analyzer (CTTA): effects of ATP depletion and changes in calcium concentration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992; 1133(3):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoelzle DJ, Varghese BA, Chan CK, Rowat AC. A microfluidic technique to probe cell deformability. J Vis Exp. 2014;91:51474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenbluth MJ, Lam WA, Fletcher DA. Analyzing cell mechanics in hematologic diseases with microfluidic biophysical flow cytometry. Lab Chip. 2008;8(7):1062–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang YJ, Lee SJ. In vitro and ex vivo measurement of the biophysical properties of blood using microfluidic platforms and animal models. Analyst. 2018;143(12):2723–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L, Huang S, Xu X, Han J. Study of individual erythrocyte deformability susceptibility to INFeD and ethanol using a microfluidic chip. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodrigues RO, Pinho D, Faustino V, Lima R. A simple microfluidic device for the deformability assessment of blood cells in a continuous flow. Biomed Microdevices. 2015;17(6):108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bransky A, Korin N, Nemirovski Y, Dinnar U. Correlation between erythrocytes deformability and size: a study using a microchannel based cell analyzer. Microvasc Res. 2007;73(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Feng Y, Wan J, Chen H. Enhanced separation of aged RBCs by designing channel cross section. Biomicrofluidics. 2018;12:024106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shevkoplyas SS, Yoshida T, Gifford SC, Bitensky MW. Direct measurement of the impact of impaired erythrocyte deformability on microvascular network perfusion in a microfluidic device. Lab Chip. 2006; 6(7):914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cluitmans JCA, Chokkalingam V, Janssen AM, Brock R, Huck WTS, Bosman GJCGM. Alterations in red blood cell deformability during storage: a microfluidic approach. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014: 764268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dobbe JG, Hardeman MR, Streekstra GJ, Strackee J, Ince C, Grimbergen CA. Analyzing red blood cell-deformability distributions. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28(3):373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Relevy H, Koshkaryev A, Manny N, Yedgar S, Barshtein G. Blood banking-induced alteration of red blood cell flow properties. Transfusion. 2008;48(1):136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobbe JG, Streekstra GJ, Hardeman MR, Ince C, Grimbergen CA. Measurement of the distribution of red blood cell deformability using an automated rheoscope. Cytometry. 2002;50(6):313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Stangner T, Wiklund K, Rodriguez A, Andersson M. UmUTracker: a versatile MATLAB program for automated particle tracking of 2D light microscopy or 3D digital holography data. Comput Phys Commun. 2017;219:390–399. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lake M, Narciso C, Cowdrick K, et al. Microfluidic Device Design, Fabrication, and Testing Protocols Exchange. 2015.

- 45.Mollison PL. The introduction of citrate as an anticoagulant for transfusion and of glucose as a red cell preservative. Br J Haematol. 2001; 108(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schrott W, Slouka Z, Červenka P, et al. Study on surface properties of PDMS microfluidic chips treated with albumin. Biomicrofluidics. 2009; 3(4):044101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vent-Schmidt J, Waltz X, Pichon A, Hardy-Dessources MD, Romana M, Connes P. Indirect viscosimetric method is less accurate than ektacytometry for the measurement of red blood cell deformability. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2015;59(2):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Athanassiou G, Moutzouri A, Kourakli A, Zoumbos N. Effect of hydroxyurea on the deformability of the red blood cell membrane in patients with sickle cell anemia. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006; 35(1–2):291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballas SK, Dover GJ, Charache S. Effect of hydroxyurea on the rheological properties of sickle erythrocytes in vivo. Am J Hematol. 1989; 32(2):104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D’Alessandro A, Liumbruno G, Grazzini G, Zolla L. Red blood cell storage: the story so far. Blood Transfus. 2010;8(2):82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flegel WA, Natanson C, Klein HG. Does prolonged storage of red blood cells cause harm? Br J Haematol. 2014;165(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosendahl P, Plak K, Jacobi A, et al. Real-time fluorescence and deformability cytometry. Nat Methods. 2018;15(5):355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barshtein G, Pries AR, Goldschmidt N, et al. Deformability of transfused red blood cells is a potent determinant of transfusion-induced change in recipient’s blood flow. Microcirculation. 2016;23(7):479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters JM, Ansari MQ. Multiparameter flow cytometry in the diagnosis and management of acute leukemia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011; 135(1):44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weir EG, Borowitz MJ. Flow cytometry in the diagnosis of acute leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2001;38(2):124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.