Abstract

Objective

The incidence of tracheostomy-dependence in critically ill children is increasing in the US. We do not know the impact of this decision on parental outcomes. We aimed to determine the incidence of decisional conflict and regret and explore the impact on quality of life (QoL) among parents considering tracheostomy placement for their child.

Design

prospective, mixed-methods longitudinal study

Setting

Pediatric, cardiac, and neonatal intensive care units of a single quaternary medical center.

Interventions

none.

Measurements and Main Results

Parents completed a Decisional Conflict survey at the time of tracheostomy decision and Decisional Regret and quality of life surveys at two weeks and three months after the decision regarding tracheostomy placement was made. We enrolled 39 parents, of which 25 completed surveys at all three time points. Thirty five of 39 (89.7%) reported at least some decisional conflict, most commonly from feeling uninformed and pressured to make a decision. At two weeks, 13/25 (52%) parents reported regret, which increased to 18/25 participants (72%) at 3-months. Regret stemmed from feeling uninformed, ill-chosen timing of placement and perceptions of inadequate medical care. At two weeks the QoL score was in the mid-range, 78.8 (SD 13.8) and decreased to 75.5 (SD 14.2) at 3-months. QoL was impacted by the overwhelming medical care and complexity of caring for a child with a tracheostomy, financial burden and effect on parent’s psychosocial health.

Conclusions

The decision to pursue tracheostomy among parents of critically ill children is fraught with conflict with worsening regret and quality of life over time. Strategies to reduce contributing factors may improve parental outcomes after this life-changing decision.

Indexing Terms: Clinical Decision-Making; ethics, research; Child; Intensive care; Critical illness; Intensive care units, pediatric

INTRODUCTION

Tracheostomy is a common decision parents of critically ill children are asked to consider. The incidence of tracheostomy placement in the United States is increasing, with nearly 5,000 pediatric tracheostomies placed annually(1). The decision to pursue tracheostomy is not one to be taken lightly. It is associated with real benefits and, unfortunately, many burdens and complications(2). Studies have reported a 6–15% mortality rate years following tracheostomy placement, an average of 4 hospitalizations and a 38.8% complication rate in the 2-year period following tracheostomy placement(3–5). At our institution, the inpatient mortality rate after tracheostomy placement and prior to initial discharge is 11%, while the mortality rate for all children in our pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is 2–3%. In addition to high mortality rates, these patients comprise 20% of PICU admissions(6), consume high proportions of critical care resources, have prolonged lengths of stays in the intensive care unit (ICU) and often require transition to a subacute facility prior to returning home due to intense parental training(7). The potential complications and long-term implications make it imperative parents are resolute in their decision to pursue this life-altering procedure for their child.

Understanding the complex caregiver responsibilities of caring for a child with a tracheostomy is challenging. Parents must learn a lot about tracheostomy management and in most centers also complete cardiopulmonary resuscitation training. Learning these new, complicated techniques while preparing to take a child home with new technology may lead to conflicting emotions about this life-saving procedure. We do not know whether parents are conflicted about this decision and the sources of that conflict. We also do not know the incidence of regret surrounding this decision and the parent’s perspective on factors affecting their quality of life after discharge from the hospital. In this longitudinal study we aimed to determine the incidence of decisional conflict and regret surrounding tracheostomy decision and to explore the factors that contribute to this conflict and regret. We also aimed to investigate the factors impacting parental quality of life after tracheostomy placement in their child.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We performed a single-center prospective, mixed-methods longitudinal study across our three ICUs – pediatric (PICU), cardiac (CICU), and neonatal (NICU) of a quaternary medical center from January 2015 to December 2017. English-speaking parents of children in any of the three ICUs who participated in a scheduled family conference to discuss tracheostomy placement were eligible for enrollment. Qualified parents were defined as adults with primary decision-making responsibilities for the critically ill child, including the biological parent, adopted or foster parent, or member of the extended family. Research staff screened for eligibility twice a week by consulting with the clinical team and the tracheostomy nurse (H.G.M) responsible for hospital-wide tracheostomy care teaching. Written consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Children’s National Medical Center Institutional Review Board and written consent was obtained from the subjects.

Sources of Data

We collected clinical data from electronic medical records and survey data from parent interviews. Parents were contacted in person, by email, or by phone, based on their preference to complete surveys and a brief interview. Data collection included three separate time points: at the time of tracheostomy decision (T1), two-weeks (T2) and three-months (T3) after enrollment. Surveys included a demographic questionnaire and Decisional Conflict Scale (8) at T1, Decisional Regret questionnaire (9) and the Adult Carer Quality of Life Questionnaire (Ac-QOL)(10) at T2 and T3. All surveys are self-administered, validated tools. The Decisional Conflict scale measures personal perceptions of uncertainty in choosing options and asks parents to reflect on feelings regarding how informed and satisfied they felt with the decision. The decisional conflict scale asks parents to reflect on their distress or remorse after making a healthcare decision. Decisional regret has been associated with higher decisional conflict, lower satisfaction with the decision, and adverse health outcomes such as greater anxiety (11).

The Decisional Regret and Conflict scores are reported on Likert scales, which are then converted to a range from 0–100. A score of 0=no conflict/regret, 1–25=mild conflict/regret and >25= severe conflict/regret. The Adult Carer Quality of Life Questionnaire is a 40-question instrument devised to measure overall quality of life for adult care givers through assessment of 8 domains and scored from 0–120. Low quality of life correlated to scores of 0–40, mid-range quality of life for scores 41–80 and high quality of life for scores 81 and above. The interview focused on semi-structured questions asking parents to expand on the factors contributing to decisional conflict and regret and impacting quality of life.

Data Analysis

We employed a mixed-methods approach. Our primary outcome was incidence of decisional conflict and regret in parents of children who are offered tracheostomies. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sample characteristics. Means and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for continuous measures. Fisher’s exact test was employed to test the association between mortality and tracheostomy placement, decisional conflict and regret. Decisional conflict and regret were measured as dichotomous variables (at least some conflict/regret vs. no regret), as reported in several other studies. Probit regression was applied to test the effect of tracheostomy placement on the likelihood of reporting regret, controlling for covariates (e.g., age, race, location, marital status, education, and diagnosis category). As sample size is small, Bayesian estimator with Probit link was applied for model estimation. Model fit was evaluated using Bayesian posterior predictive checking (12, 13).

Qualitative analysis was employed to extract the intended meaning of narrative content by characterizing individual parental quotes during the semi-structured interview (14). We applied directed content analysis (15) and used investigator triangulation (16) with three investigators (A.H.J, L.M.H, T.W.O) reviewing all quotes. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Demographic and Tracheostomy Data

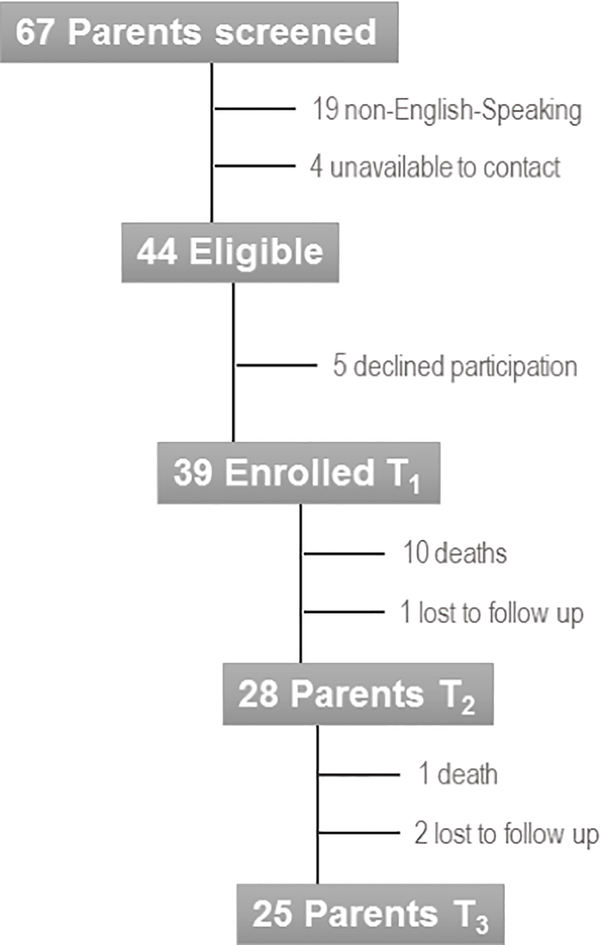

We screened 67 parents; 19 were non-English-speaking and 4 were unavailable at the bedside or by phone after 3 contact attempts, resulting in 44 eligible parents. Five parents (11.4%) declined participation resulting in 39 (88.6%) parents enrolled. Of the 39 participants, 11 children died during the study period and their parents were not contacted further (25%), an additional three parents were lost to follow up (6.8%), resulting in 25 (56.8%) parents with complete follow up assessments (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Study Enrollment Flowchart

Demographic data about the patients and their parents are described in Table 1. Of the 39 patients, 24 (61.5%) were admitted to the PICU, 12 (30.8%) to the NICU and 3 (7.7%) to the CICU. The majority of children were discharged to home (41%), while 11 (25.6%) died prior to discharge. There was no difference in mortality rates between those who opted against the tracheostomy (3/8 parents) compared to those who opted for the tracheostomy (8/31 parents, p=0.6).

Table 1:

Parent and Patient Demographic Characteristics

| Parent Demographics | N = 39 (%) | |

| Relationship to Child | Mother | 25 (64.1) |

| Parent Age (Years) | 20–29 | 5 (12.8) |

| 30–39 | 19 (48.7) | |

| 40–49 | 12 (30.8) | |

| 50–59 | 3 (7.7) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 26 (68.4) |

| Highest Education Completed | Some middle school | 1 (2.6) |

| Graduated High School/GED | 23 (59) | |

| Bachelors | 4 (10.3) | |

| Graduate/professional degree | 11 (28.2) | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 28 (73.7) |

| Religious Affiliation | None | 14 (35.9) |

| Christian | 12 (30.8) | |

| Muslim | 1 (2.6) | |

| Other | 12 (30.8) | |

| Insurance Type | Medicaid | 19 (48.7) |

| Private | 20 (51.3) | |

| Patient Demographics | N = 39 (%) | |

| Age (months) | Median (IQR) | 11 (0–248) |

| Race | Black | 19 (48.7) |

| White | 17 (43.6) | |

| Other | 3 (7.7) | |

| Primary Indication for Tracheostomy | Respiratory | 22 (56.4) |

| Non- Respiratory | 17 (43.6) | |

| Patient location | PICU | 24 (61.5) |

| NICU | 12 (30.8) | |

| CICU | 3 (7.7) | |

| Tracheostomy Accepted Death | Yes | 31 (79.5) |

| Death after Tracheostomy | 8 (25.8) | |

| Tracheostomy Refused Death | Yes | 8 (20.5) |

| Death without Tracheostomy | 3 (37.5) | |

| Disposition | Home | 16 (41) |

| Death | 11 (28.2) | |

| Long-Term Care Facility | 9 (23.1) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 3 (7.7) | |

A tracheostomy was placed in 31/39 patients (79.5%) despite only 18 (46.2%) parents reporting a preference for tracheostomy at the time the decision was made. At enrollment, 19/39 (46.3%) parents reported no prior discussions about tracheostomy with the medical team. Conversely, 20/39 parents (51.3%) reported prior discussions, of which 10.3% had three prior discussions and 17.9% had participated in >5 discussions with the medical team.

Decisional Conflict

At the time the parent made a decision to opt for or against tracheostomy placement 35/39 (89.7%) reported at least some decisional conflict. The average conflict score was 19.7 (SD 16.8), falling into the mild conflict category.

Thematic analysis of the sources of conflict revealed six themes: parents feeling as if they have no choice, needing more information to make the decision, struggling to maintain hope, feeling pressured from the medical team, balancing their needs with the needs of their child and weighing options without judgement (Table 2).

Table 2:

Themes Describing Parental Conflict Regarding the Tracheostomy Decision

| Theme | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| No Choice | “If I knew there was any other option, I would have taken it. We chose the tracheostomy as a last resort to save our baby’s life.” “As it was explained to my husband and I in our ‘family meeting’ with the attending Neonatalogist, the trach was the only option for [our son] to ever be able to leave the hospital. If we chose to not do the surgery, we would be ‘letting him go’ and he would not survive without the trach and ventilator. Looking back, I feel that [our son’s] condition was unfairly evaluated as more dire than it actually is. I still wonder if the trach would have been necessary if [our son’s] condition continued to improve.” |

| Uninformed | “I don’t know what the options are. What are the benefits of a trach vs. intubation? Is there a possibility she might get better on her own?” ‘We had to do a lot of research online on our own so it has taken me long to decide because I do not feel informed.’ |

| Maintaining Hope | “My son may need a trach but we are not sure yet. I want to do what’s best for my son but I also hope he does not need a trach.” “The doctors would not give me a full spectrum of his possible prognoses, only the worst case scenarios. When asked about the best case, they avoided the question. Not because best case scenarios may not exist, but because even talking about best case scenarios might mean that, we the parents, would ignore the other end of the spectrum. As a result, any decision I made would not be informed.” |

| Putting My Child’s Needs Above My Own | “I am not as sure about what to do as his mother. I want what’s best for him” ‘I know my son should not get a trach... I am making the decision that is best for my son, NOT the decision that is best for me’ |

| Felt Pressured | “The doctors had already made the decision to place the trach. All discussions and answers to questions were designed to convince me to agree with their decision.” It would be better if they (physicians) didn’t mention it so many times, maybe tighten up the communication channels and not have so many different people saying the same thing. I understand it is their job to take care of [my son] medically, but they should also be aware of our family’s emotions. |

| Weighing Options without Judgement | “‘I changed my decision between Friday and Monday from trach to no trach and I felt judged by the new nurse... she treated me like I hadn’t thought at all about it which is clearly NOT the case. I prayed, paced, and cried about the decision, so it set me into orbit that she thought I could be so careless.” “I hear the word tracheostomy and I just worry. I worry what my family and my community will think.” |

Decisional Regret

Two weeks after the tracheostomy decision, 13/25 (52%) reported some decisional regret, with an average score of 13.8 (SD 18.8), falling into the mild regret category. Parents of children who died had significantly less regret (10%) compared to those whose child survived (80%, p=0.001). At 3-months after the tracheostomy decision was made more parents 18/25 (72%) reported some decisional regret with an average score rising to 18.8 (SD 23.2). Regression analysis revealed parents who did not prefer a tracheostomy but had one placed were significantly less likely to report regret at T3 (β=−1.450, 95% CI: −3.093, −0.005) compared to others. None of the covariates including age, race, ICU location, marital status, education, or primary diagnosis had a significant effect on the likelihood of regret at T3.

Qualitatively, decisional regret fell into three themes: parents feeling uninformed, ruing the timing of the decision (either tracheostomy placed too late or too soon) and disappointment in the medical care received (Table 3). Not all parents reported regret. Seven parents reported high satisfaction with the decision they participated in making (Table 3).

Table 3:

Themes Describing Parental Regret Regarding the Tracheostomy Decision

| Theme | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Uninformed | “We quickly arrived at what the decision needed to be. Our problem was always more around how the ‘choices’ were presented and the information that was held back” “I am not really certain that the tracheostomy was the best decision for my son based on the information given to us.” |

| Regret Timing | “I almost wish we had seen the scope sooner, so she could have been on the road to recovery earlier. The not knowing made things difficult” “Though I am very confident we made the right choice to get a tracheostomy, sometimes I wonder if we should have given my child more time to develop the airway protective reflexes.” |

| Regret: Medical Care | “My daughter has been caused much more harm than good with her trach and nurses need more training with trach care, as well a respiratory therapists” |

| No Regret | ‘These questions don’t really apply because my son is doing much better’ “Without the trach, my child would have suffered and probably failed to thrive. It has been a blessing. It was a very, very difficult decision to make, and still there is daily angst just to make sure it is clear, clean, and in place, but I have no regrets.” “Now that my son has a diagnosis, his need for a long-term tracheostomy has been confirmed. It was an incredibly difficult and painful decision, but it has allowed my son to thrive at home, and avoid repeat hospitalizations.” |

Short Term Quality of Life

At 2 weeks after the decision, parents reported an average QoL score of 78.8 (SD 13.8) compared to a slightly lower score of 75.5 (SD 14.2) at the 3-month time period, both falling in the mid-range of QOL. Parental QoL for those who opted for the tracheostomy was impacted by four main aspects: the overwhelming medical care, complexity of caring for a child with a tracheostomy, financial burden, and parental psychosocial health. For parents who opted against the tracheostomy, all of their quotes regarding QoL fell into the psychosocial health theme (Table 4).

Table 4:

Themes Describing Influencers on Quality of Life after the Tracheostomy Decision

| Theme | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Parent Psychosocial Wellbeing | “Looking at the crib last week was saddening because when you go through pregnancy you expect things to be okay after” “I cry a lot. It is hard, so hard.” |

| Financial Burden | “The financial concerns are also overwhelming, even with the benefits of health insurance” “I worry about money, but not because of caring.” |

| Medical Fragility | “It’s not the role of caregiver that’s frustrating, it is the fragility of the prognosis. I hold my breath all day long waiting for the next ‘issue’ positive or negative. It’s completely unsettling” “Having a child who is medically fragile is one of the most difficult challenges of my life. It is a sacrifice that it absolutely worth it, but it is not a decision that should be taken lightly or without careful thought.” |

| Overwhelming Medical Care | “Adding the trach just adds a new layer of responsibility and stress. Learning to care can be exhausting and overwhelming” “I wish I had known how difficult it is to find qualified nursing for the home, and I wish I had a better idea of how Medicaid works. Had I known that we wouldn’t have night nurses due to a lack of availability I could have planned differently.” |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore decisional conflict, regret and factors affecting quality of life in parents across three different ICU settings. At the time of decision to pursue tracheostomy nearly 90% of parents reported decisional conflict. Two-weeks after the decision was made the majority (52%) of parents reported decisional regret, increasing to 72% of parents at three months after the decision. Interestingly, we found that parents who did not prefer tracheostomy, but had one placed reported less regret. This may indicate that parents prefer some level of paternalism when making these potentially life-limiting decisions so that the burden is shared by the healthcare team and does not lie solely on the parent. These finding can also indicate the need for families to “do something” when feeling hopeless. Reacting to devastating illness can lead parents to make decisions that are not necessarily motivated by care in the best interest of the child (17). Additionally, it may be that those parents who did not prefer the tracheostomy had lower expectations of its benefits, including potential earlier rehabilitation and thus ultimately had less regret when the tracheostomy proved to be better than they expected. The reason for this association is unknown, future work is needed to explore parental decision-making preferences.

The decision to place a tracheostomy in a child is complicated, without a strict algorithm to help guide the process. These children have long lengths of stay in our various ICU’s, have high utilization of resources and have high rates of mortality (25% compared to 2–3% across most ICUs caring for infants and children). Choosing which patients would benefit from tracheostomy placement is important. We were surprised to find no difference in mortality between those who had a tracheostomy placed compared to those who did not. We do not know the quality of life reports for bereaved children who had undergone tracheostomy placement, but it does beg the question; was tracheostomy placement the best decision for these children who died during the hospitalization after tracheostomy placement?

Patient selection is important, but it is equally important how this decision is discussed with parents. These results show parents report feeling pressured and uninformed, which contributes to conflict around this decision. Similar to the literature, we found parents expressed a desire for more information both at the time of the decision to pursue tracheostomy and after the decision was made and a need to feel confident they are putting their child’s needs above their own. Research from our group and others has found parents often rely on fulfilling their internal definition of being a good parent to their ill child when making complicated medical decisions (18, 19). Aligning with a parent’s values and how they see their role as a parent may be a strategy to help parents feel more secure in their decision, thereby experiencing less conflict.

Nearly 18% of parents were approached more than five times by the healthcare team without any association between number of tracheostomy discussions and a decision to pursue tracheostomy. It may be that based on experience, the healthcare team would recommend tracheostomy placement and our results suggest parents hear that message, but many may not agree with it and repeating the message does not seem to lead to a quicker or different decision. We know from the literature that high decisional conflict is positively correlated with decisional regret. We also know that decisional regret by surrogate decision makers is linked to psychosocial outcomes, such as anxiety and depression (20–21). These psychosocial consequences (20–21) can be long-lasting and further impact a parent’s ability to care for a child with a tracheostomy. Our results show parental quality of life is already impacted early on. It is important to collect data on parental QoL in future studies because a reduced parental QoL impacts not only the caregiver, but also the patient, family and community (22). And this impact may vary based on the child’s diagnosis, clinical course and other factors such as the potential for decannulation in the future. The biggest burdens contributing to lower QoL included overwhelming medical care, fear of death with a medically fragile child requiring constant vigilance and the psychological and financial impact on caregivers. Our job as a healthcare team is to ensure parents are informed not only about the immediate, but also the long-term effects of this decision. The healthcare team must balance giving parents enough information to feel informed, but not overwhelmed.

Navigating this fine line is hard work and the healthcare team should not do it alone. Connecting parents with a support system of peers through a registry of families who have pursued and not pursued tracheostomy may be a way to give them the information they so desire without feeling pressured into a decision (23). Providing resources such as consultation with a nurse tracheostomy specialist, complex care team or parent navigator and internet resources may also help families gain access to information. Offering parents simulation-based experiences to practice caregiving prior to discharge may also help parents achieve confidence.

Although this paper offers the critical care field a valuable exploration of parental decisional conflict and regret surrounding the decision to pursue tracheostomy, we acknowledge these sentiments may not be universal given the small sample size and single center nature of this study. Enrollment of additional participants may have allowed for exploration of how various covariates (including race, age, ICU location, marital status, education and diagnosis/indication for tracheostomy) could potentially affect decisional conflict and regret. We recognize completing surveys labeled “decisional regret and conflict” may bias parents into viewing their experience through the lens of regret and conflict. We chose surveys that are validated tools which have been used in a variety of settings to mitigate the impact. We also did not collect information about the child’s quality of life or family functioning, which may be important factors influencing a parent’s decision and ensuing regret. We were unable to capture the conflict and regret experienced by bereaved parents at the three-month follow-up and only report data among English-speaking caregivers. Lastly, we only captured regret and quality of life measures up to three months after the decision was made, we do not know the trajectory of these measures over time and their impact on long term psychosocial outcomes, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression. A recent study concluded high decisional satisfaction among parents of children with medical complexity who opted for a tracheostomy (24). These interviews occurred up to five years after the decision was made and parents reported providing medical care to their children although difficult, improved over time. Additionally, these decisions all occurred within the critical care environment, where emotions are often heightened. We do not know the levels of decisional conflict and regret among parents making these decisions in outpatient settings where the intensity and time to make decisions may be different. Further study is needed to capture the full weight of this complicated, life-changing decision including following parents for a longer period of time to determine the true impact of this decision.

CONCLUSIONS

The decision to pursue tracheostomy while your child is in the intensive care unit is complex and surrounded by parental conflict with worsening regret and quality of life over the short term. Feeling uninformed and pressured to make a decision is a major source of conflict and regret. As a medical community we must develop strategies to better support families through this emotional decision and after the decision to prepare parents for consequences that may impact their quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by grant 1K23HD080902 from the National Institutes of Health and grant UL1TR0001876 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences to the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children’s National Health Systems.

“Copyright form disclosure: Dr. October’s institution received funding from National Institutes of Health (NIH), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Services; she received funding from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children’s National Health Systems; and she received support for article research from the NIH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.”

Footnotes

The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahida JB, Asti L, Boss EF, et al. Tracheostomy Placement in Children Younger Than 2 Years. JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg 2016;142:241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert LM, Watson AC, Madrigal V, et al. Discussing Benefits and Risks of Tracheostomy. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:e592–e597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry JG, Graham DA, Graham RJ, et al. Predictors of Clinical Outcomes and Hospital Resource Use of Children After Tracheotomy. Pediatrics 2009;124:563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr MM, Poje CP, Kingston L, et al. Complications in Pediatric Tracheostomies. Laryngoscope 2001;111:1925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watters K, O’Neill M, Zhu H, et al. Two-year mortality, complications, and healthcare use in children with medicaid following tracheostomy. Laryngoscope 2016;126:2611–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heneghan JA, Reeder RW, Dean JM, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Critical Illness in Children With Feeding and Respiratory Technology Dependence. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019;1.doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang J, Amin R. Respiratory Care Considerations for Children with Medical Complexity. Children 2017;4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickman RL, Daly BJ, Lee E. Decisional conflict and regret: Consequences of surrogate decision making for the chronically critically ill. Appl Nurs Res 2012;25:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a Decision Regret Scale. Med Decis Mak 2003;23:281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph S, Becker S, Elwick H, et al. Adult carers quality of life questionnaire (AC-QoL): development of an evidence-based tool. Ment Heal Rev J 2012;17:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becerra Pérez, Menear M, Brehaut JC, et al. Extent and Predictors of Decision Regret about Health Care Decisions: A Systematic Review. Med Decis Making. 2016. August;36(6):777–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, et al. Bayesian Data Analysis, Third Edition. Chapman Texts Stat Sci Ser; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill J Introduction to Applied Bayesian Statistics and Estimation for Social Scientists. J Am Stat Assoc 2008;103:1322–1323. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shelley M, Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. J Am Stat Assoc 1984;79:240. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, et al. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014;41:545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendler D The Value of doing Something. CCM 2019; 47:149–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madrigal VN, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, et al. Parental decision-making preferences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2876–2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, et al. The Parent Perspective; “being a good parent” when making Critical Decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15(4):291–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson-Leduc P, Turcotte S, Labrecque M, Légaré F. Prevalence of clinically significant decisional conflict: an analysis of five studies on decision-making in primary care. BMJ Open 2016;6:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoester H, Grootenhuis MA, and Bos AP. Outcome of paediatric intensive care survivors. Eur J Pediatr 2007; 166(11):1119–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chilren’s National Health Systems. October 20, 2016. Tracheostomy – What is it and is it right for my child? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDuPPl22-7E&t=39s

- 24.Nageswaran S, Golden SL, Gower WA, et al. Caregiver Perceptions about their Decision to Pursue Tracheostomy for Children with Medical Complexity. J Pediatr 2018; 203:354–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]