Abstract

Bone is the most preferred site for colonization of metastatic breast cancer cells for each subtype of the disease. The standard of therapeutic care for breast cancer patients with bone metastasis include bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid), which have poor oral bioavailability, and a humanized antibody (denosumab). However, these therapies are palliative and a subset of patients still develop new bone lesions and/or experience serious adverse effects. Therefore, a safe and orally bioavailable intervention for therapy of osteolytic bone resorption is still a clinically unmet need. This study demonstrates suppression of breast cancer-induced bone resorption by a small molecule (sulforaphane, SFN) that is safe clinically and orally bioavailable. In vitro osteoclast differentiation was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner upon addition of conditioned media from SFN-treated breast cancer cells representative of different subtypes. Targeted microarrays coupled with interrogation of TCGA dataset revealed a novel SFN-regulated gene signature involving cross-regulation of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and nuclear factor-κB and their downstream effectors. Both RUNX2 and p65/p50 expression were higher in human breast cancer tissues compared to normal mammary tissues. RUNX2 was recruited at the promotor of NFKB1. Inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by SFN was augmented by doxycycline-inducible stable knockdown of RUNX2. Oral SFN administration significantly increased the percentage of bone volume/total volume of affected bones in the intracardiac MDA-MB-231-Luc model indicating in vivo suppression of osteolytic bone resorption by SFN. These results indicate that SFN is a novel inhibitor of breast cancer induced osteolytic bone resorption in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: breast cancer, osteoclastogenesis, sulforaphane

Introduction

Breast cancer, a prominent cause of cancer-related mortality in American women, is a heterogeneous malignancy broadly classified into different subtypes including luminal-type, basal-like (mostly triple-negative), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-amplified, and normal-like based on unique gene expression signatures (1,2). The primary cause of mortality in patients with breast cancer is due to metastatic spread to distant organs (3,4). Even though metastatic spread in breast cancer patients is commonly observed in the liver, lung, skeleton or brain, bone is the preferred site for colonization of cancer cells for each subtype of this disease (4). Debilitating complications associated with bone metastasis include pathological fractures, nerve compression, pain, and calcium imbalance (5–7).

The bone homeostasis (turnover) under normal physiological conditions is regulated by bone forming osteoblasts (mono-nucleated cells of mesenchymal stem cell lineage) and bone resorbing osteoclasts that are multi-nucleated cells of hematopoietic lineage (7). Bone metastasis in breast cancer patients is most often accompanied by osteolytic bone resorption leading to degradation of mineralized collagen matrix and hypercalcemia (7–9). Breast cancer cells and both osteoclasts and osteoblasts support each other by secreting growth factors and cytokines [e.g., macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (NF- κB) ligand (RANKL), interleukin-8 (IL8), IL-11, etc.] creating a “vicious cycle” of breast cancer growth and osteoclast differentiation leading to osteolytic bone resorption (7–9).

The standard of therapeutic care for patients with metastatic breast cancer includes bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid) and a humanized antibody (denosumab) against RANKL, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily (10–12). However, these therapies are palliative, and a subset of patients are unresponsive and still develop new bone lesions or experience serious adverse effects (13–16). Increased risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw is one of the serious side effects of bisphosphonate therapy (16). Moreover, bisphosphonates have unfavorable pharmacokinetic attributes including poor oral bioavailability, whereas denosumab has unfavorable cost-effectiveness (17,18). These findings underscore a clinically unmet need of a safe, inexpensive, and orally bioavailable intervention for treatment of osteolytic bone resorption in breast cancer patients.

Sulforaphane (SFN), a constituent of cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli sprout, is a promising anticancer phytochemical with compelling preclinical activity in therapeutic as well as preventative settings (19–22). More importantly, the safety of SFN and SFN-rich broccoli sprout extract (SFN-BSE) has been tested clinically (23–26). In one such clinical trial with men and women with atypical nevi, we showed previously that daily oral SFN-BSE intake (50, 100, and 200 μmol/day) for 28 days was safe (26). In the present study, we investigated the in vitro and in vivo efficacy of SFN on breast cancer-induced osteoclastic bone resorption because of its favorable safety profile and excellent oral bioavailability (19–26), and inhibitory effect on osteoclast differentiation when directly added to osteoclast precursor cells (27,28).

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Use of mice for this study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol # 18012079).

Reagents

Racemic sulforaphane (SFN; purity > 99.5%) was purchased from LKT laboratories (St. Paul, MN). Stock solution of SFN (10 mM) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with growth medium (final concentration of DMSO- 0.4%). Reagents for cell culture, including fetal bovine serum (FBS), cell culture media, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and antibiotic mixture were purchased from Life Technologies-Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). An antibody against runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) for immunoblotting was purchased from MBL International (Woburn, MA) and anti-β-actin antibody was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). An antibody against RUNX2 for immunofluorescence and anti-RUNX2 antibody for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). For immunohistochemistry, anti-RUNX2 antibody was purchased from Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO), whereas anti-NF-κB (p65 subunit) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-NF-κB p105/p50 subunit antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Kits for the measurements of secreted Cathepsin K (CTSK), TNFα, and RANKL in the conditioned media from control- and SFN-treated cells were purchased from MyBioSource (San Diego, CA), eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and LSBio (Seattle, WA), respectively. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody was from Life Technologies. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody was from Abcam. Recombinant murine soluble RANKL and M-CSF were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). RANKL level in mouse plasma was measured using a kit from Abcam. Kits for determination of CTSK and IL8 levels in mouse plasma were purchased from MyBioSource.

Cell lines

Nonadherent mouse bone marrow monocytes (BMM) were isolated from the bone marrow of female C57BL/6 mice and cultured in minimum essential medium-α supplemented with M-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 3 days prior to use in the osteoclast differentiation assay. Human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, SK-BR-3, and MCF-7) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). These cell lines were last authenticated by us in March of 2017 by short tandem repeat profiling by IDEXX BioResearch (Columbia, MO). Monolayer cultures of the above-mentioned human breast cancer cell lines were maintained as recommended by the supplier. The 4T1.2 mouse mammary tumor cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Robin L. Anderson (Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia) and cultured in minimum essential medium-α supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible stable RUNX2 knockdown T47D cell line (hereafter abbreviated as T47D-shRUNX2Dox) was generously provided by Dr. Baruch Frenkel (University of Southern California, CA). The T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. RUNX2 knockdown was achieved by addition of 250 ng/mL of aqueous doxycycline solution. The MDA-MB-231 cell line stably expressing firefly luciferase (MDA-MB-231-luc-D3H1; hereafter abbreviated as MDA-MB-231-Luc) was purchased from Caliper Life Sciences (now Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and maintained in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics, non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, and L-glutamine. The 4T1.2, T47D-shRUNX2Dox, 4T1.2, and MDA-MB-231-Luc cell lines were not authenticated by us. Each cell line was maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Osteoclast differentiation assay

Osteoclast differentiation was assessed by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) assay after addition of conditioned media from control or SFN-treated breast cancer cells to osteoclast precursor BMM. Briefly, breast cancer cells were treated with either DMSO or different concentrations of SFN for 48 hours. The conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes, and stored at −20°C. BMM were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 200,000 cells per well with the supplementation of M-CSF (20 ng/mL). After 72 hours, media was replaced with osteoclast differentiation media containing M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (10 ng/mL) alone or with 10% of conditioned medium from control or SFN-treated breast cancer cells. Cultures were continued for an additional 5–6 days with replacement of osteoclast differentiation media every other day. At the end of the experiments, the cell monolayers were gently washed with PBS and fixed with a solution containing 37% formaldehyde, acetone, and citrate. TRAP assay was done using a kit from Millipore Sigma according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Multinucleated osteoclasts were counted manually and photographed using a Leica microscope equipped with a digital camera at ×20 objective magnification.

The levels of SFN in the conditioned media of control and SFN-treated (0, 5 and 10 μmol/L SFN for 48 hours) MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and SK-BR-3 cells were determined essentially as described by us previously (29). Other details of LC-MS/MS have been described by us previously (29).

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

A qRT-PCR-based expression profiling was done for 84 human genes implicated in bone remodeling using RT2 Profiler™ Human Osteogenesis PCR Array (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RT2 first standard kit was used for complementary DNA synthesis and RT2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR master-mix was used for PCR amplification. Breast cancer cell lines were either treated with DMSO or 5 μM SFN for 24 hours. Data analysis was done using online-based tool of Qiagen. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control to calculate gene expression changes.

For real-time RT-PCR, cells were treated with DMSO or different concentrations of SFN for 16 hours or 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated using a RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen. The complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA with the use of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)20 primer. PCR was performed using SYBR green master-mix at 95°C (15 seconds), 60°C for annealing (60 seconds), and 72°C (30 seconds) for 40 cycles. GAPDH was used as a control. Primers were as follows: RUNX2 Forward: 5′-GGTTAATCTCCGCAGGTCACT-3′; RUNX2 Reverse: 5′-CACTGTGCTGAAGAGGCTGTT-3′; COL1A1 Forward: 5′-TCTGCGACAACGGCAAGGTG-3′; COL1A1 Reverse: 5′-GACGCCGGTGGTTTCTTGGT-3′; CTSK Forward: 5′-TTCTGCTGCTACCTGTGGTG-3′; CTSK Reverse: 5′-GCCTCAAGGTTATGGATGGA-3′; TNF Forward: 5′-GAAAGCATGATCCGGGACGTG-3′, TNF Reverse: 5′-GATGGCAGAGAGGAGGTTGAC-3′; MMP9 Forward: 5′-TTGACAGCGACAAGAAGTGG-3′, MMP9 Reverse: 5′-GCCATTCACGTCGTCCTTAT-3′; GAPDH Forward: 5′-GGACCTGACCTGCCGTCTGAA-3′; GAPDH Reverse: 5′-GGTGTCGCTGTTGAAGTCGAG-3′. Relative gene expression was calculated using the method of Livak and Schmittgen (30).

Confocal microscopy

Breast cancer cell lines (25,000 cells per well) were plated in 24-well plates in triplicate on coverslips and allowed to adhere by overnight incubation. The cells were treated with DMSO or 5 μmol/L of SFN for 24 hours. The cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, and then blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.15% glycine in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with RUNX2 antibody (1:50 dilution) overnight at 4°C. The cells were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-containing mounting solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature. Stained cells were observed under a Nikon A1 spectral confocal microscope at ×40 objective magnification in oil. Image intensity was measured using ImageJ 1.48V software.

Luciferase assay

Breast cancer cells were plated in 12-well plates (100,000 cells per well). One μg of either RUNX2-dependent or NF-κB-dependent luciferase plasmid was co-transfected with renilla luciferase plasmid using FuGENE HD (Promega, Madison, WI) as a transfection reagent. After 24 hours of transfection, the cells were treated with either DMSO or different concentrations of SFN for 24 hours. The cells were harvested in lysis buffer and luciferase activity was measured using dual-luciferase reporter assay kit from Promega. For NF-κB luciferase activity measurement, T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells were treated with either 250 ng/mL of Dox or 2.5 μmol/L of SFN for 24 hours after 24 hours of transfection with NF-κB luciferase plasmid. Values were normalized for renilla luciferase and protein concentration.

Immunohistochemistry in tissue micro arrays (TMA)

Human breast cancer (triple-negative and luminal-type) and adjacent normal mammary TMAs were purchased from US Biomax (Derwood, MD). Immunohistochemistry for RUNX2 (1:100 dilution), p65 NF-κB (1:200 dilution), or p105/p50 NF-κB (1:200 dilution) was performed essentially as described by us previously (31). Images were captured using a light microscope (Leica DM IRB) at ×20 magnification for RUNX2 and ×5 magnification for p65 NF-κB and p105/p50 NF-κB and analyzed by using Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) using a nuclear algorithm.

Western blotting

Whole cell lysate from breast cancer cells was prepared as described previously (32). Briefly, T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells were treated with DMSO or 5 μmol/L of SFN in the absence or presence of 250 ng/mL of doxycycline for 24 hours prior to preparation of whole cell lysate. Western blotting was done as described by us previously (31,32). Immunoreactive bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using UN-SCAN-IT software version 5.1 (Silk Scientific, Orem, USA).

Determination of RANKL, CTSK, and TNFα levels

Secreted levels of CTSK, TNFα, RANKL were determined in the conditioned media of MDA-MB-231 cells following 24 hours or 48 hours of culture in the presence of DMSO (control) or SFN using a human-specific kit for each cytokine and by following the manufacturer’s protocol.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data analysis

RNA-Seq data from TCGA database for breast cancer samples (n = 1097) were used to assess the correlation between RUNX2 and NFKB1 and their target genes in breast cancer samples. TCGA data set was analyzed using University of California Santa Cruz Xena Browser (https://xena.ucsc.edu/public-hubs/).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes (4×106 cells per treatment group) and treated with either DMSO or 5 μmol/L of SFN for 24 hours. The cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Magnetic ChIP kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used for immunoprecipitation and genomic DNA isolation. Normal mouse IgG and RUNX2 antibodies were used for chromatin-immunoprecipitation. Primers for NFKB1 were as follows: Site 1 Forward: 5′-GCTGGGTTTTTGTGTGTGTG-3′ (from −1175 to −1156 relative to NFKB1 start site), Site 1 Reverse: 5′-TGGGTGGAGTGACAACTGAA-3′ (from −971 to −951 relative to NFKB1 start site); Site 2 and 3 Forward: 5′-GCCTGGTGAGGACCTGATTA-3′ (from −1012 to −993 relative to NFKB1 start site), Site 2 and 3 Reverse: 5′-ATCTGGCAGAGGGGAGTTTT-3′ (from −759 to −740 relative to NFKB1 start site); Negative control Forward: 5′-CCCTGCTAGGAAGCCAGAG-3′ (from −262 to −244 relative to NFKB1 start site), Negative control Reverse: 5′-CACTGACGTCGAGAGAGCAT-3′ (from −38 to −19 relative to NFKB1 start site).

In vivo study

Twenty BALB/C-nu/nu female mice of ~4 weeks of age were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). After reaching 80–90% confluency, MDA-MB-231-Luc cells were collected by trypsin treatment, washed with PBS, and re-suspended in ice-cold PBS at a cell density of 106 cells/mL. At ~6 weeks of age, mice were anesthetized and maintained with a continuous flow of 2.5% isoflurane during the procedure of tumor cell inoculation. Cell suspension (100 μL containing 100,000 cells/mouse) was injected into the left ventricle of each mouse using a 27G needle. Three mice died after the intra-cardiac cell injection for unknown reasons. Surviving mice were randomized based on initial IVIS image intensity into two groups: a) control group (n = 8), and b) SFN treatment group (n = 9). One week after tumor cell injection, experimental group of mice received 1 mg SFN/mouse in corn oil orally 5 times per week (Monday-Friday). The control group of mice received oral corn oil 5 times per week (Monday-Friday). Two mice from the SFN treatment group died after four weeks of cell injection during bioluminescence imaging possibly due to complications from anesthesia. Body weights were recorded weekly.

Bioluminescence and computed tomography (CT) imaging

Bioluminescence imaging was done weekly using IVIS200 (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) with FOV 25.8 and binning 8. Ten minutes prior to imaging, 150 μL D-luciferin solution (30 mg/mL) was injected via intraperitoneal route. Maximum exposure time to get bioluminescence image was 2 minutes. CT imaging was performed on the Siemens Inveon Multi-modality positron emission tomography/computed tomography scanner. Scans were done at low/medium magnification (220 projections, 60kV/500 μA with a 950 ms exposure) with a 50 mm axial field of view at 2×2 binning. CT reconstructions were done using Siemens’ Feldkamp algorithm with low noise reduction and Shepp-Logan filtering at a downsampling = 0. Images were viewed and analyzed in Siemens Inveon Research Workplace (IRW) software. The ratio of bone volume to total volume (~43 mm3) of affected bone was calculated using IRW software.

Ex Vivo 64Cu-CB-TE1A1P-DBCO-c(RGDyK) (64Cu-RGD) phosphor imaging

The 64Cu-RGD was synthesized as described by us previously (33). Mice were given a single dose of ~200 μCi 64Cu-RGD tracer via lateral tail vein injection. Prior to exposure, the phosphor screen was erased with the Fujifilm IP Eraser 3 for at least 20 minutes. At 24 hours post-injection of 64Cu-RGD, mice were sacrificed, and bones were collected. The bone samples were placed onto the phosphor screen overnight in the Fujifilm BAS Casette2 2025, and the phosphor screen was exposed for 18 hours in darkness, transferred to the laser scanner in the dark, and then imaged on a Typhoon FLA 7000 fast laser scanner (GE Healthcare) using the following settings: 650 nm later, PMT 700, 100 μm pixel size, L5 latitude. Once the scan was complete, the image file was processed using the ImageQuant™ software. Imaging data were analyzed using ImageJ 1.48V software.

Determination of RANKL, IL8, and CTSK levels in mouse plasma

Whole blood was collected from mice at the time of sacrifice in heparin-coated syringes. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. RANKL, IL8, and CTSK levels in mice plasma were determined using kits and by following manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitation of osteoclasts in vivo by TRAP assay

Affected bones identified by imaging and CT were collected and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at the end of animal study. Bones were decalcified using 14% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 7.4) solution for 14 days. H&E and TRAP staining of 5 μm sections of bones were done. Specimens were de-paraffinized in xylene, re-hydrated through ethanol-water mixture (100%, 95%, 90%, 70%, and 30%) and finally washed with deionized water before staining. The specimens were pre-incubated with TRAP staining incubation buffer (112 mmol/L of sodium acetate, 50 mmol/L of sodium tartrate dibasic dihydrate, 2.8 mL of glacial acetic acid, pH 4.7) for 30 minutes and then replaced with freshly made TRAP substrate buffer (1 mmol/L of naphthol AS-MX phosphate, 2 mmol/L of fast red violet salt, in TRAP staining incubation buffer. After 30 minutes of incubation, the specimens were washed with deionized water and mounted with aqua mount. Sections were visualized and imaged using a Leica microscope at ×5 objective magnification.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of difference was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s or Bonferroni’s adjustment. For two sample comparisons, unpaired Student t test was used. A significance level was set at .05. Statistical analyses were performed using a GraphPad Prism (v 7.02, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

SFN inhibited breast cancer cell-induced osteoclast differentiation in vitro

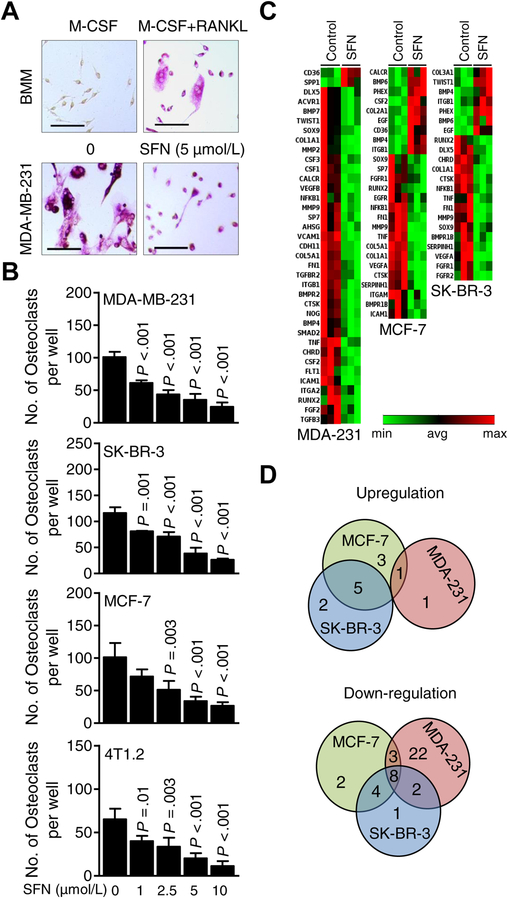

We have published previously that the steady state plasma SFN concentration ranges between 2.2 and 7.5 μmol/L after daily oral administration of SFN-BSE for 28 days in men or women with atypical nevi (26). Thus, SFN concentrations of 1–10 μM were used for the in vitro assays. To model the physiological situation in which breast cancer cells following colonization to the bone secrete cytokines and growth factors to fuel osteoclast activation, the conditioned media from well-characterized human breast cancer cell lines representative of different subtypes, including luminal-type (MCF-7), HER2-amplified (SK-BR-3), and basal-like (MDA-MB-231) and a basal-type mouse mammary tumor cell line (4T1.2) were used for the in vitro osteoclast differentiation assays. Multinucleated osteoclasts resulting from exposure of BMM to M-CSF plus RANKL mixture can be visualized in Fig. 1A. Osteoclast differentiation was inhibited significantly upon addition of conditioned media from SFN-treated breast cancer cells (Fig. 1B). These results indicated that SFN was a potent inhibitor of osteoclast differentiation in vitro at pharmacologically-relevant concentrations.

Figure 1.

Sulforaphane (SFN) treatment suppressed breast cancer cell-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro by downregulating key bone remodeling genes. A, Representative microscopic images of bone marrow monocytes (BMM) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase positive (TRAP+) multinucleated osteoclast cells resulting from exposure of BMM to macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) + receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL) with or without treatment with SFN (scale bar = 150 μm, ×20 objective magnification). B, Quantitation of the number of osteoclasts per well for data shown in panel A. Multi-nucleated (nuclei > 3) TRAP+ cells were counted. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple test. The experiments were repeated twice, and the results were consistent. C, Heat maps showing the patterns of gene expressions in MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231), MCF-7, and SK-BR-3 cells after 24 hours of treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 5 μmol/L SFN. The cutoff was ≥ 1.3-fold change in expression with a P < 0.08. D, Venn diagrams showing the upregulated and down-regulated genes in response to SFN treatment.

We also considered the possibility of whether SFN was still present in the conditioned media of breast cancer cells. SFN levels were measured in the conditioned media of MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and SK-BR-3 cells following 48 hours of treatment with 5 and 10 μmol/L SFN. Residual amounts of SFN representing about 20–24% of the starting dose were detectable in the conditioned media of all three cell lines. Therefore, it is possible that part of the inhibitory effect of SFN on osteoclast differentiation may be attributed to its direct action on osteoclast precursor cells at least at the 5 and 10 μmol/L concentrations.

SFN treatment downregulated a set of genes implicated in bone remodeling

Fig. 1C depicts heat maps for SFN-mediated alterations in expression of genes implicated in bone remodeling. The expression changes of individual genes are summarized in Supplementary Fig. S1A. As shown in Fig. 1D, Venn diagram showed SFN-mediated down-regulation of 8 common genes (identified by arrows in Supplementary Fig. S1A) in each tested cell line that included 3 transcription factors (RUNX2, NFKB1, and SOX9), and five secreted proteins [collagen 1A1, (COL1A1), CTSK, TNF, matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), and fibronectin 1 (FN1)] (Supplementary Fig. S1A). RT-PCR confirmed dose-dependent downregulation of some of these genes upon exposure to SFN in each tested cell line (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

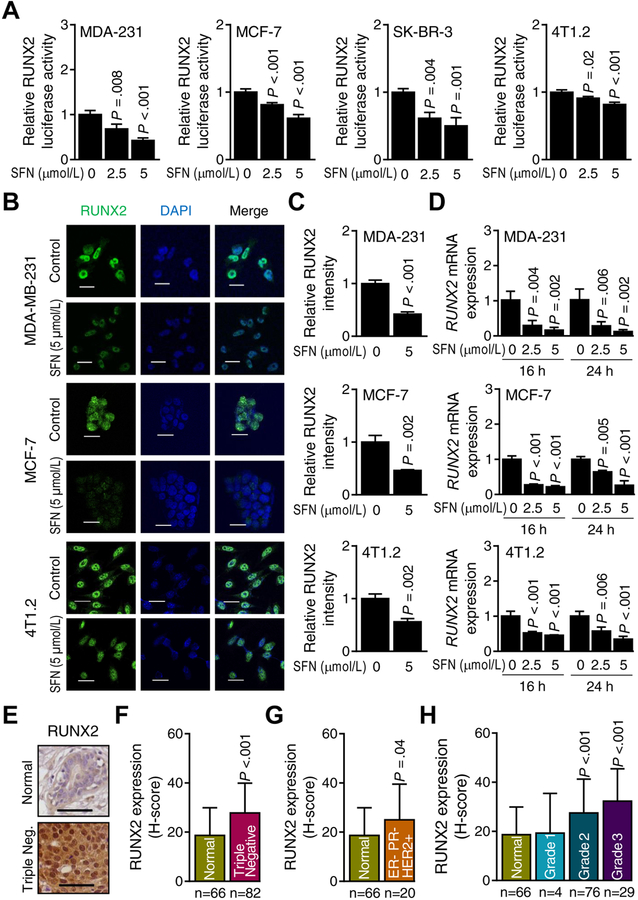

The role of RUNX2 in SFN-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation

In normal breast, RUNX2 regulates expression of genes involved in the production of milk proteins such as β-casein during lactation (34). RUNX2 is also expressed in breast cancer cells and regulates skeletal metastasis (35). SFN treatment dose-dependently inhibited the transcriptional activity of RUNX2 in each tested cell line as revealed by RUNX2-responsive luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 2A). The nuclear level of RUNX2 was markedly lower in SFN-treated breast cancer cells compared with controls (Fig. 2B,C, and Supplementary Fig. S2A,B). SFN treatment also resulted in a decrease in RUNX2 mRNA level in each cell line (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. S2C). These results indicated transcriptional repression of RUNX2 following SFN treatment.

Figure 2.

Sulforaphane (SFN) treatment inhibits runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) in breast cancer cells. A, RUNX2-dependent luciferase activity in MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231), MCF-7, SK-BR-3, and 4T1.2 cells after 24 hours of treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (control) or the indicated doses of SFN. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3–4). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Consistent results were obtained from repeated experiments. B, Representative confocal microscopic images (×63 objective magnification in oil) of RUNX2 protein (green) in MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and 4T1.2 cells after 24 hours of treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 5 μmol/L SFN. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). C, Quantitation of RUNX2 protein level intensity in breast cancer cells for data shown in panel B. Results shown are mean RUNX2 intensity ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t test. D, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of RUNX2 mRNA expression in MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231), MCF-7, and 4T1.2 cells treated with DMSO or indicated doses of SFN for specified time points. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test. Consistent results were obtained from repeated experiments. E, Representative images for RUNX2 immunohistochemistry (scale bar = 100 μm, ×20 objective magnification). F, Quantitation (H-score) of RUNX2 protein expression in normal breast tissues (n = 66) and triple negative breast tumor tissues (n = 82). G, Quantitation (H-score) of RUNX2 protein expression in normal breast tissues (n = 66) and ER−/PR−/HER2+ breast tumor tissues (n = 20). H, Quantitation (H-score) of RUNX2 protein expression in different grades [grade 1 (n = 4), grade 2 (n = 76), and grade 3 (n = 29)] of breast cancer tissues along with normal breast tissues (n = 66). Results (F–H) shown are mean ± SD and statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test (F–G) or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (H).

Fig. 2E shows immunohistochemistry for RUNX2 protein in a representative section of a normal human mammary tissue or a triple negative breast cancer. The H-score for RUNX2 protein expression was significantly higher in the triple-negative tissue array when compared to that of cancer-adjacent normal mammary tissue (Fig. 2F). The estrogen receptor-negative (ER−), progesterone receptor-negative (PR−) but HER2-positive (HER2+) breast cancers (Fig. 2G) as well as Grade 2 and Grade 3 breast carcinomas (Fig. 2H) also exhibited an increase in RUNX2 H-score in comparison with cancer-adjacent normal mammary tissue. The expression of RUNX2 protein was also higher in luminal-type breast cancer when compared to normal mammary tissue as revealed by quantitative immunohistochemistry using tissue microarrays of normal breast and luminal-type breast cancer (Supplementary Fig. S3A,B).

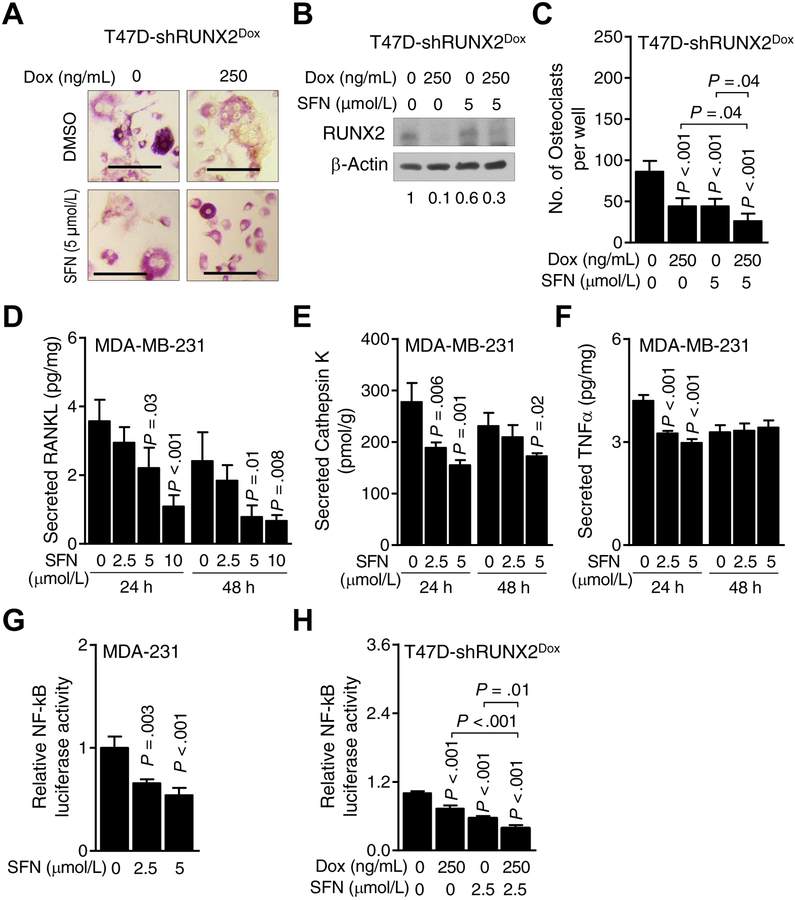

Fig. 3A depicts in vitro osteoclast differentiation in BMM cultured in the presence of M-CSF + RANKL along with addition of conditioned media from T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells treated with doxycycline and cultured for 48 hours with or without DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L SFN. Both Dox-inducible knockdown of RUNX2 as well as SFN treatment inhibited osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 3B,C). Moreover, SFN-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation was augmented by Dox-inducible knockdown of RUNX2 (Fig. 3C). The secretion of known downstream targets of RUNX2 (RANKL and CTSK; Refs. 36,37) was also suppressed in MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to SFN (Fig. 3D–F).

Figure 3.

Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) knockdown augments sulforaphane (SFN)-mediated inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. A, Representative microscopic images (×20 objective magnification) of osteoclasts from culture of bone marrow monocytes (BMM) with conditioned media from T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or SFN in the absence or presence of doxycycline (Dox). B, Western blot showing the expression of RUNX2 protein in T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells treated with DMSO or SFN in the absence or presence of Dox. The values below the blot indicate the relative expression of RUNX2 compared to control. C, Quantitation of number of osteoclasts shown in panel A. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=6). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Quantitation of secreted levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL, D), Cathepsin K (E), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα, F) in cell culture supernatant of MDA-MB-231 cells after 24- and 48-hour of treatment with different doses of SFN. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s adjustment. Consistent results were obtained from repeated experiments. G, Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-dependent luciferase activity in MDA-MB-231 cells after DMSO or SFN treatment for 24 hours. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett’s adjustment. Consistent results were obtained from repeated experiments. H, Luciferase activity of NF-κB in T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells after treatment with DMSO or SFN in the absence or presence of Dox for 24 hours. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference analyzed by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Consistent results were obtained from repeated experiments.

RUNX2 is novel regulator of NF-κB

Next, we explored possible cross-regulation of the transcription factors that were suppressed by SFN in each tested breast cancer cell line. We focused on NFKB1 (also known as p105 that is processed to the p50 NF-κB subunit) as NF-κB is known to share a common downstream target (MMP9) with RUNX2 (38,39). However, to the best of our knowledge, a role for RUNX2 in the regulation of the NFKB1 gene in breast cancer has not been suggested previously. Using a luciferase reporter, we found that the transcriptional activity of NF-κB was dose-dependently inhibited upon treatment with SFN when compared to the control (Fig. 3G). Moreover, Dox--inducible knockdown of RUNX2 in T47D-shRUNX2Dox cells augmented SFN-mediated inhibition of NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 3H). These results suggested a possible role for RUNX2 in regulation of NFKB1 gene expression.

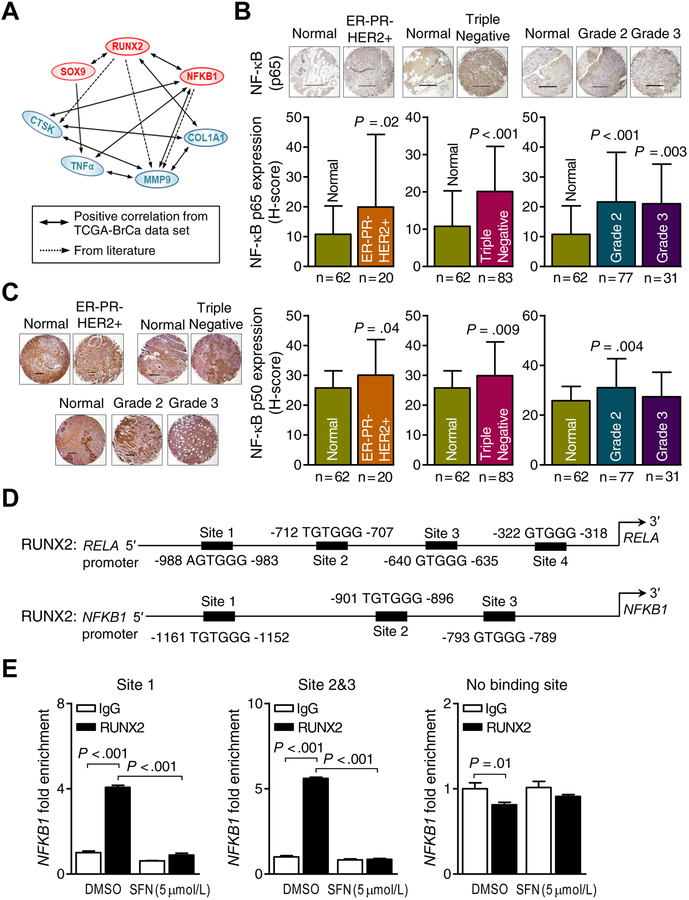

The solid lines in the mechanistic cartoon in Fig. 4A signify positive TCGA correlations between expression of RUNX2, NFKB1, and SOX9 and their putative downstream targets. The broken lines in Fig. 4A represent regulatory functions already known from the published literature, including reciprocal-regulation of RUNX2 and SOX9, regulation of MMP9 by RUNX2 as well as NF-κB, and CTSK gene regulation by RUNX2 (37–41). Analysis of the RNA-Seq data in breast cancer TCGA (n = 1097) revealed a significant positive correlation between expression of RUNX2 and NFKB1 mRNAs. Similar to RUNX2, the protein levels of the p65 (RELA) (Fig. 4B) and p50 (NFKB1) subunits (Fig. 4C) of NF-κB were higher in ER−/PR−/HER2+, triple negative, and Grade 2/3 breast cancers compared to breast cancer-adjacent normal mammary tissues (Fig. 4B,C).

Figure 4.

Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2)-nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) axis plays a central role in the inhibitory effect of sulforaphane (SFN) on breast cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis. A, Schematic diagram showing correlation among genes associated with SFN from the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) breast cancer data set and the literature. The positive TCGA correlations are highlighted by solid lines. The broken lines represent regulatory functions already known from the published literature, including reciprocal-regulation of RUNX2 and SOX9, regulation of matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) by RUNX2 as well as NF-κB, and cathepsin K (CTSK) gene regulation by RUNX2. B, upper panel: Representative p65 (RELA)-NF-κB immunohistochemical images (scale bar = 500 μm, ×5 objective magnification). lower panel: Quantitation (H-score) of p65-NF-κB expression in normal breast tissues (n = 62) and ER−/PR−/HER2+ breast tumor tissues (n = 20) (lower left); in normal breast tissues (n = 62) and triple negative breast tumor tissues (n = 83) (lower middle); in different grades [grade 2 (n = 77), and grade 3 (n = 31)] of breast cancer tissues along with normal breast tissues (n = 62) (lower right). Results shown are mean ± SD. Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test (left and middle lower panel) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (lower right panel). C, left panel: Representative p50 (NFKB1)-NF-κB immunohistochemical images (scale bar = 500 μm, ×5 objective magnification). right panel: quantitation (H-score) of p50-NF-κB expression in normal breast tissues (n = 62) and ER−/PR−/HER2+ breast tumor tissues (n = 20); in normal breast tissues (n = 62) and triple negative breast tumor tissues (n = 83); in different grades [grade 2 (n = 77), and grade 3 (n = 31)] of breast cancer tissues along with normal breast tissues (n = 62). Results shown are mean ± SD. Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student t test (for ER−/PR−/HER2+ and triple negative plots) or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (for tumor grades plot). D, Putative RUNX2 binding sequence sites in the promoter region of RELA and NFKB1 genes. E, Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using MDA-MB-231 cells showing the binding of RUNX2 transcription factor to the NFKB1 promoter. Results shown are the mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical significance of difference analyzed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

Three putative RUNX2 consensus binding sequence sites (40) were identified in the promoter of NFKB1 gene (Fig. 4D). As a proof of principle, we determined RUNX2 occupancy at the promoter of NFKB1 by ChIP assay and found that RUNX2 was present at these binding sites in the NFKB1 promoter (Fig. 4E). In addition, the RUNX2 occupancy at the NFKB1 promoter was attenuated upon treatment with SFN (Fig. 4E). As a negative control, we used a primer for amplification of a region distant from the 3 RUNX2 consensus binding sites at the NFKB1 promoter. RUNX2 occupancy or modulation by SFN treatment was not observed for the negative control (Fig. 4E). Further analyses of the TCGA data set (Supplementary Table S1) and consensus binding sequence sites for the 2 transcription factors (RUNX2, and NF-κB) in the set of 8 SFN-repressed genes (Supplementary Table S2) suggest additional cross-regulation of these 2 transcription factors. Additional target promoters had putative RUNX occupancy sites (Supplementary Table S2), including COL1A1, TNFα, and MMP9. As can be seen in Supplementary Fig. S4A,B, RUNX2 occupancy was observed at the promoter of MMP9 only.

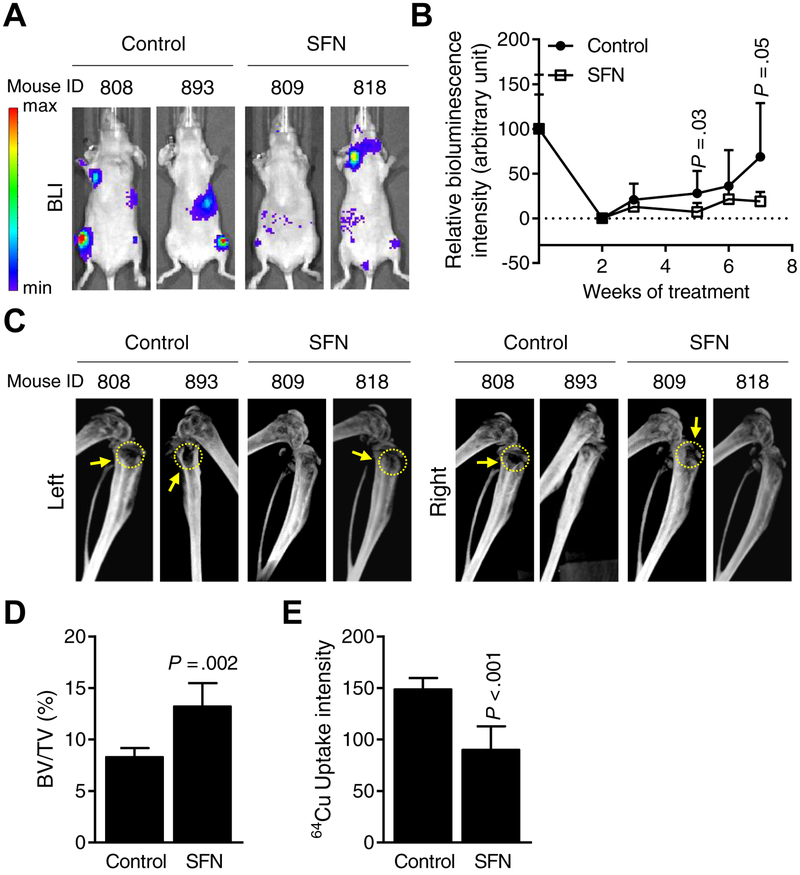

Oral administration of SFN inhibits osteolytic bone resorption in vivo

Fig. 5A shows bioluminescence imaging for representative mice of the control group and those of the SFN treatment group at day 49 after tumor cell injection. The average bioluminescence intensity in affected bones was 74% lower in SFN-treated mice when compared to controls (Fig. 5B). Representative CT images for mice of the control and SFN treatment groups at day 47 after tumor cell injection are shown in Fig. 5C. The bone loss is identified by yellow arrows and circles in Fig. 5C. The percentage of affected bone volume/total volume was 1.6-fold higher in the SFN-treated mice when compared to control (Fig. 5D; P = 0.002) indicating inhibition of bone erosion.

Figure 5.

Oral administration of sulforaphane (SFN) inhibits breast cancer-induced osteolytic bone resorption in vivo. A, Representative bioluminescence images of control (corn oil) and SFN-treated (1 mg SFN/mouse in corn oil) mice at 7 weeks after intracardiac injection of MDA-MB-231-Luc cells. Bar at left end indicates intensity of bioluminescence (red representing high intensity and blue representing low intensity). B, Quantitation of bioluminescence of control- (n = 7~8) and SFN-treated (n = 6~9) mice over time. Results shown are mean ± SD. Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. C, Representative computed tomography images of affected bones from control- and SFN-treated mice. Yellow dotted circles and arrows indicate bone resorption. D, Quantitation of bone volume (BV)/total volume (TV) of affected hind limbs of control- and SFN-treated mice. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=5 for both groups). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. E, Quantitative plot of ex vivo 64Cu-RGD uptake intensity by affected bones of control- and SFN-treated mice. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=6–7). Statistical significance of difference analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test (n = 7 for control and n = 6 for SFN group).

To evaluate osteoclasts directly mice were injected with Cu64-RGD, which binds αvβ3 integrin on osteoclasts, prior to sacrifice, and the Cu64-RGD uptake was measured ex vivo. Consistent with the BV/TV findings, the Cu64-RGD uptake intensity was 1.6-fold higher in the affected bones of control mice than those of SFN-treated mice (Fig. 5E; P < 0.001).

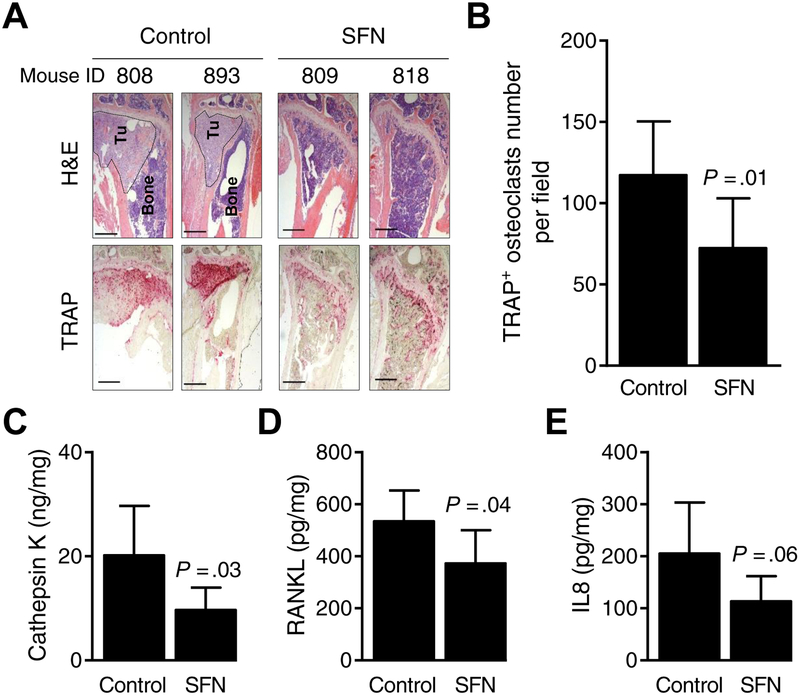

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and TRAP staining in representative bone sections of control and SFN-treated mice are shown in Fig. 6A. The TRAP+ osteoclast number per field was significantly lower in the affected bones of SFN-treated mice when compared to controls (Fig. 6B). The plasma levels of CTSK (Fig. 6C; P = 0.03), RANKL (Fig. 6D; P = 0.04), and IL8 (Fig. 6E; P = 0.06) were lower by 30–52% in SFN-treated mice compared with controls. Finally, SFN administration was safe and did not cause weight loss in mice. Collectively, these results provided in vivo evidence for suppression by osteolytic bone erosion by oral administration of SFN.

Figure 6.

Sulforaphane (SFN) administration inhibits osteoclast formation in vivo. A, Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections (upper panel) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase positive (TRAP+) osteoclasts (lower panel) at ×5 objective magnification from control- and SFN-treated mice [dotted circles (Tu) indicate breast cancer cells in bone]. B, Quantitation of TRAP+ osteoclast number per field of bones. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=8). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test). Quantitation of plasma levels of cathepsin K (C), receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL, D), and interleukin-8 (IL8, E) from control- and SFN-treated mice. Results shown are mean ± SD (n=6–8). Statistical significance of difference was analyzed by unpaired Student t test (n = 7–8 for control and n = 6 for SFN group).

Discussion

SFN is a promising phytochemical with compelling preclinical activity and a favorable clinical safety profile (20–26). Preclinically, temporal prenatal/maternal exposure to an SFN-BSE diet prevented breast cancer development in two different transgenic mouse models (20). In another study, SFN treatment was shown to not only enhance the anticancer efficacy of doxorubicin but also offer protection against its cardiotoxicity in a preclinical model of breast cancer (21). The SFN metabolites were bioavailable in normal mammary epithelial cells of women undergoing reduction mammoplasty following a single oral administration of SFN-BSE (24). The present study demonstrates that SFN is a novel inhibitor of breast cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro and in vivo. The in vitro activity of SFN in genetically heterogeneous cell lines has broader implications because skeletal metastasis is prevalent in each subtype of the breast cancer.

It is important to mention that Kim et al. (28) were the first to demonstrate inhibition of RANKL (100 ng/mL)/M-CSF (100 ng/mL)-stimulated differentiation of osteoclasts by SFN (1 μmol/L) when added directly to the BMM. Exposure of murine Raw 264.7 cells to 5 and 10 μmol/L SFN resulted in inhibition of NF-κB activity (28). Addition of SFN to cultures of MC3T3-E1, a pre-osteoblastic cell line derived from a new-born mouse calvaria, resulted in promotion of their differentiation (41). Furthermore, SFN administration (7.5 mmol/L intraperitoneally every other day for 5 weeks) to overectomized mice in a non-cancer model (C57BL6/J), which exhibit bone loss due to estrogen deficiency, as well as sham-operated control mice resulted in higher bone volume/total volume and total number of trabecular cells (41). Mechanistic studies showed that SFN treatment promoted osteoblast differentiation by increasing extracellular matrix mineralization (41). Collectively, these results indicate that SFN has opposing effects on differentiation of osteoclasts (inhibition of differentiation) and osteoblasts (promotion of differentiation) when added to their respective precursor cells.

The present study reveals a novel SFN-regulated gene network in suppression of breast cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis. The SFN-treated cells exhibit downregulation of the genes for RUNX2, NFKB1, and SOX9 transcription factors. There was a positive association between RUNX2 and NFKB1 evident in the TCGA data set. In an analysis of protein expression, we found up-regulation of both RUNX2 and the p50-NF-κB and its partner p65-NF-κB in Grade 2/3 breast tumor tissue arrays and in different subtypes in comparison with normal mammary tissue. We also found RUNX2 occupancy at the NFKB1 and MMP9 promoters. The lower levels of RUNX2 and NF-κB activity leads to reduced transcription and secretion of matrix degrading factors, including COL1A1, MMP9, and CTSK, which have been implicated in metastasis for different types of cancers including breast cancer (42–44). MMP9 has been implicated in metastasis for different types of cancers including breast cancer (42). CTSK is a cysteine protease that plays an important role in degradation of the demineralized collagen matrix (6,7). COL1A1 was shown recently to promote metastatic potential of breast cancer cells (44).

In this study, the SFN-mediated inhibition of breast cancer-induced bone resorption in vivo in mice was associated with a significant decrease in circulating (plasma) levels of IL8. Significantly, the IL8 finding from the present study corroborates our previous observations from a pilot clinical trial in which we showed that the plasma level of IL8 was below the detection limit following 28 days of oral administration of SFN-BSE in patients with atypical nevi, whereas, the IL8 was detected in the plasma of the same patients at baseline prior to SFN-BSE administration (26). The IL8 gene was not included in the targeted qRT-PCR array used in this study. Nevertheless, published work has revealed important roles of IL8 in breast cancer-induced osteolysis that is independent of the RANKL pathway (45–47). These results suggest that both RANKL and IL8 suppression by SFN may be important mechanistic factors in its osteoclastogenesis inhibitory effects.

In summary, the present study shows inhibition of breast cancer-induced osteolytic bone resorption by oral administration of SFN. Mechanistic studies identify a novel SFN-regulated gene network in breast cancer cells important for its inhibitory activity. Finally, we have identified a pharmacodynamic biomarker (IL8) whose circulating level is significantly decreased in mice and humans following oral administration of SFN or SFN-BSE.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was supported in part by a Hillman Foundation Pilot grant (S.V. Singh), the National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA225716 and R01 CA142604 (S.V. Singh), and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R01 AR057310 (D.L. Galson). This study used the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center Core Facilities, including the Animal Facility, the In Vivo Imaging Facility, and the Tissue and Research Pathology Facility partly supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health grant P30 CA047904. The funders had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, manuscript preparation or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References:

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:10869–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van ‘t Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, Cheang MC, Voduc D, Speers CH, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubens RD. The nature of metastatic bone disease In: Rubens RD, Fogelman I, editors. Bone metastasis: diagnosis and treatment. London; Springer-Verlag; 1991. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 1997;80:1588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:584–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weilbaecher KN, Guise TA, McCauley LK. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:411–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Pape F, Vargas G, Clézardin P. The role of osteoclasts in breast cancer bone metastasis. J Bone Oncol 2016;5:93–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Acker HH, Anguille S, Willemen Y, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF. Bisphosphonates for cancer treatment: mechanisms of action and lessons from clinical trials. Pharmacol Ther 2016;158:24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathew A, Brufsky A. Bisphosphonates in breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2015;137:753–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gül G, Sendur MA, Aksoy S, Sever AR, Altundag K. A comprehensive review of denosumab for bone metastasis in patients with solid tumors. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennel KA, Drake MT. Adverse effects of bisphosphonates: implications for osteoporosis management. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:632–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compston J. Safety of long-term denosumab therapy for osteoporosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:485–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Body JJ, Bone HG, de Boer RH, Stopeck A, Van Poznak C, Damião R, et al. Hypocalcaemia in patients with metastatic bone disease treated with denosumab. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1812–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung P, Bedogni G, Bedogni A, Petrie A, Porter S, Campisi G, et al. Time to onset of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Oral Dis 2017;23:477–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cremers SC, Pillai G, Papapoulos SE. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of bisphosphonates: use for optimisation of intermittent therapy for osteoporosis. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005;44:551–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matuoka JY, Kahn JG, Secoli SR. Denosumab versus bisphosphonates for the treatment of bone metastases from solid tumors: a systematic review. Eur J Health Econ 2018; in press, doi: 10.1007/s10198-018-1011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh SV, Singh K. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary isothiocyanates mature for clinical translational research. Carcinogenesis 2012;33:1833–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Buckhaults P, Li S, Tollefsbol T. Temporal efficacy of a sulforaphane-based broccoli sprout diet in prevention of breast cancer through modulation of epigenetic mechanisms. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2018;11:451–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bose C, Awasthi S, Sharma R, Beneš H, Hauer-Jensen M, Boerma M, et al. Sulforaphane potentiates anticancer effects of doxorubicin and attenuates its cardiotoxicity in a breast cancer model. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro NP, Rangel MC, Merchant AS, MacKinnon G, Cuttitta F, Salomon DS, et al. Sulforaphane suppresses the growth of triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2019;12:147–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atwell LL, Zhang Z, Mori M, Farris P, Vetto JT, Naik AM, et al. Sulforaphane bioavailability and chemopreventive activity in women scheduled for breast biopsy. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:1184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornblatt BS, Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Erb M, Fahey JW, Singh NK, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of sulforaphane for chemoprevention in the breast. Carcinogenesis 2007;28:1485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cipolla BG, Mandron E, Lefort JM, Coadou Y, Della Negra E, Corbel L, et al. Effect of sulforaphane in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:712–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tahata S, Singh SV, Lin Y, Hahm ER, Beumer JH, Christner SM, et al. Evaluation of biodistribution of sulforaphane after administration of oral broccoli sprout extract in melanoma patients with multiple atypical nevi. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2018;11:429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takagi T, Inoue H, Takahashi N, Katsumata-Tsuboi R, Uehara M. Sulforaphane inhibits osteoclast differentiation by suppressing the cell-cell fusion molecules DC-STAMP and OC-STAMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;483:718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SJ, Kang SY, Shin HH, Choi HS. Sulforaphane inhibits osteoclastogenesis by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB. Mol Cells 2005;20:364–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh SV, Warin R, Xiao D, Powolny AA, Stan SD, Arlotti JA, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits prostate carcinogenesis and pulmonary metastasis in TRAMP mice in association with increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. Cancer Res 2009;69:2117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hahm ER, Lee J, Kim SH, Sehrawat A, Arlotti JA, Shiva SS, et al. Metabolic alterations in mammary cancer prevention by withaferin A in a clinically relevant mouse model. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1111–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao D, Srivastava SK, Lew KL, Zeng Y, Hershberger P, Johnson CS, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate, a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells by causing G2/M arrest and inducing apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 2003;24:891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ocak M, Beaino W, White A, Zeng D, Cai Z, Anderson CJ. 64Cu-Labeled phosphonate cross-bridged chelator conjugates of c(RGDyK) for PET/CT imaging of osteolytic bone metastases. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2018;33:74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rooney N, Riggio AI, Mendoza-Villanueva D, Shore P, Cameron ER, Blyth K. Runx genes in breast cancer and the mammary lineage In: Groner Y, Ito Y, Liu P, Neil J, Speck N, van Wijnen A, editors. RUNX Proteins in Development and Cancer. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Singapore; Springer; 2017. p. 353–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wysokinski D, Blasiak J, Pawlowska E. Role of RUNX2 in breast carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2015;16:20969–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enomoto H, Shiojiri S, Hoshi K, Furuichi T, Fukuyama R, Yoshida CA, et al. Induction of osteoclast differentiation by Runx2 through receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin regulation and partial rescue of osteoclastogenesis in Runx2−/− mice by RANKL transgene. J Biol Chem 2003;278:23971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trotter TN, Li M, Pan Q, Peker D, Rowan PD, Li J, et al. Myeloma cell-derived Runx2 promotes myeloma progression in bone. Blood 2015;125:3598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pratap J, Javed A, Languino LR, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, et al. The Runx2 osteogenic transcription factor regulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 in bone metastatic cancer cells and controls cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:8581–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang H, Lee M, Choi KC, Shin DM, Ko J, Jang SW. N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide inhibits breast cancer cell invasion through suppressing NF-κB activation and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. J Cell Biochem 2012;113:2845–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Deen M, Akech J, Lapointe D, Gupta S, Young DW, Montecino MA, et al. Genomic promoter occupancy of runt-related transcription factor RUNX2 in Osteosarcoma cells identifies genes involved in cell adhesion and motility. J Biol Chem 2012;287:4503–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thaler R, Mauizi A, Roschger P, Sturmlechner I, Khani F, Spitzer S, et al. Anabolic and antiresorptive modulation of bone homeostasis by the epigenetic modulator sulforaphane, a naturally occurring isothiocyanate. J Biol Chem 2016;291:6754–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fingleton B. Matrix metalloproteinases: roles in cancer and metastasis. Front Biosci 2006;11:479–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clézardin P. Therapeutic targets for bone metastases in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2011;13:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, Shen JX, Wu HT, Li XL, Wen XF, Du CW, et al. Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1) promotes metastasis of breast cancer and is a potential therapeutic target. Discov Med 2018;25:211–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bendre MS, Margulies AG, Walser B, Akel NS, Bhattacharrya S, Skinner RA, et al. Tumor-derived interleukin-8 stimulates osteolysis independent of the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand pathway. Cancer Res 2005;65:11001–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bendre MS, Montague DC, Peery T, Akel NS, Gaddy D, Suva LJ. Interleukin-8 stimulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption is a mechanism for the increased osteolysis of metastatic bone disease. Bone 2003;33:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartman ZC, Poage GM, den Hollander P, Tsimelzon A, Hill J, Panupinthu N, et al. Growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells relies upon coordinate autocrine expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8. Cancer Res 2013;73:3470–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.