Abstract

Abstract

This article summarizes the current knowledge about the presence of naproxen in the environment, its toxicity to nontarget organisms and the microbial degradation of this drug.

Currently, naproxen has been detected in all types of water, including drinking water and groundwater. The concentrations that have been observed ranged from ng/L to μg/L. These concentrations, although low, may have a negative effect of long-term exposure on nontarget organisms, especially when naproxen is mixed with other drugs. The biological decomposition of naproxen is performed by fungi, algae and bacteria, but the only well-described pathway for its complete degradation is the degradation of naproxen by Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b). The key intermediates that appear during the degradation of naproxen by this strain are O-desmethylnaproxen and salicylate. This latter is then cleaved by 1,2-salicylate dioxygenase or is hydroxylated to gentisate or catechol. These intermediates can be cleaved by the appropriate dioxygenases, and the resulting products are incorporated into the central metabolism.

Key points

•High consumption of naproxen is reflected in its presence in the environment.

•Prolonged exposure of nontargeted organisms to naproxen can cause adverse effects.

•Naproxen biodegradation occurs mainly through desmethylnaproxen as a key intermediate.

Keywords: Naproxen, Microorganisms, Toxicity, Biodegradation

Introduction

Naproxen, which is a bicyclic propionic acid derivative, is a widely known drug from the group of non-selective, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Dzionek et al. 2018). Its mechanism of action is based on the inhibition of both cyclooxygenase isoforms that are involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins, prostacyclin and thromboxane from arachidonic acid (Angiolillo and Weisman 2017; Barcella et al. 2019). The advantages of naproxen are its rapid absorption and its long duration of action, which result from its long biological half-life (approximately 13 h), and its ability to strongly bind to the plasma proteins. Another advantage is also its diffusion into the synovial fluid. It is the preferred drug for treating osteoarthritis in patients who are at a high cardiovascular risk because, unlike diclofenac and other NSAIDs including the selective ones, when it is used in high doses, it poses a lower vascular risk (Angiolillo and Weisman 2017; Barcella et al. 2019). These advantages together with fact that naproxen can be purchased without a prescription translate into its popularity on the pharmaceutical market. For more than 40 years, it has held a strong position compared to other NSAIDs (Aguilar et al. 2019; Dzionek et al. 2018). In 2003, almost 3000 t of naproxen were produced in the world (Li et al. 2016). According to ClinCalc (2019), it was prescribed 11,470,076 times in the USA in 2016. The popularity of naproxen in the treatment of pain has resulted in its occurrence in the environment (Aguilar et al. 2019; Madikizela et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2019).

Occurrence of naproxen in the environment

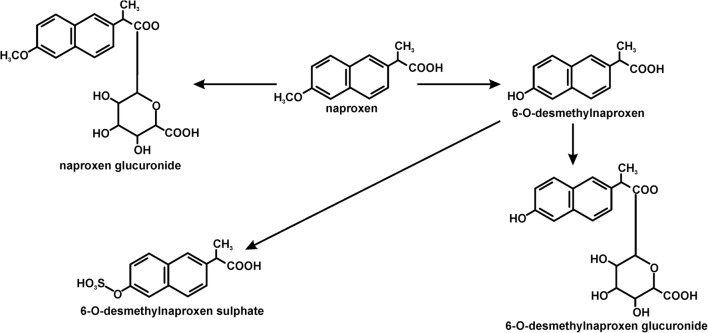

Since naproxen entered the market in 1976, it has enjoyed unflagging popularity. This has resulted in the occurrence of this compound in wastewater (Garcia-Medina et al. 2015; Shanmugam et al. 2014). In the body, naproxen is metabolized into two key products: O-desmethylnaproxen and naproxen glucuronide (Fig. 1) (Addison et al. 2000). Therefore, these compounds also end up in the wastewater. Research to date has indicated that in sewage treatment plants, naproxen does not undergo complete mineralization and despite a relatively high degree of transformation goes into the environment along with the outflow from a treatment plant (Grenni et al. 2014; Lahti and Oikari 2011; Marco-Urrea et al. 2010). The removal of naproxen in wastewater treatment plants is significantly different and ranges from its almost complete removal to only a 40% degradation level (Marco-Urrea et al. 2010). It was observed that in the effluents of wastewater treatment plants, the concentration levels of naproxen ranged from 25 ng/l to 33.9 μg/l (Marotta et al. 2013). Moreover, Suzuki et al. (2014) showed that the effluents of wastewater treatment plants also contain its major metabolite – 6-O-desmethylnaproxen at a concentration of 0.56 μg/l. Because of incomplete decomposition, naproxen occurs in groundwater, surface water as well as in drinking water (Benotti et al. 2009). It was found in 69% of >100 water samples from more than 100 European rivers at a concentration of up to 2.027 μg/l (Ding et al. 2017). Recent investigations of European Union waters have indicated that concentration of naproxen in wastewater treatment plants and in surface waters exceeds the concentration that is recommended by the European Medicines Agency by 10- to 500-fold (Grenni et al. 2013). The naproxen concentrations that have been detected in the environment are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

The transformations of naproxen that occur in higher organisms (Addison et al. 2000)

Table 1.

Naproxen concentration in the aquatic environment

| Sources | Concentration (μg/l) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Estuary of Seine River, France | Up to 0.275 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| German rivers | Up to 0.39 | Vulava et al. 2016 |

| Lake Greifensee, Switzerland | 0.003–0.010 | Straub and Stewart 2007 |

| Lake Haapajarvi, Finland | 0.040–0.21 | Brozinski et al. 2013 |

| A major river in Korea | 0.326 | Ji et al. 2013 |

| Marina catchment, Singapore | 0.008–0.108 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Ebro River, Spain | Up to 0.109 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Elbe River, Germany | up to 0.032 | Straub and Stewart 2007 |

| Fyris River, Sweden | 0.447 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Glatt River, Switzerland | 0.004–0.36 | Straub and Stewart 2007 |

| Han River, South Korea | 0.005–0.1 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Ladysmith River, South Africa | 2.77 | Madikizela et al. 2017 |

| Lopan River, Ukraine | 0.2–0.264 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Malir River, Pakistan | 11.4–32.00 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Mbokodweni River, South Africa | 1.0–3.8 | Sibeko et al. 2019 |

| Pearl River, China | Up to 0.328 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Rhine River, Germany and Switzerland | Up to 0.028 | Straub and Stewart 2007 |

| Sindian River, Taiwan | 0.035–0.27 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Tiber River, Italy | 0.24–0.27 | Grenni et al. 2014 |

| Rivers, Canada | Up to 4.5 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Rivers, Japan | Up to 0.24 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Rivers, Poland | Up to 0.753 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Rivers, Slovenia | Up to 0.08 | Shanmugam et al. 2014 |

| Seawater, Portugal | 0.178 | Jallouli et al. 2016 |

| Sediment of the Danube River, Europe | 7–57 μg/kg | Garcia-Medina et al. 2015 |

| Water sources from Mexico City, Mexico | 0.052–0.186 | Garcia-Medina et al. 2015 |

The concentration of naproxen in the environment depends on its physicochemical properties such as solubility and chemical stability as well as environmental properties, while its mobility in the environment correlates to chemical properties such as the dissociation constant and the value of the octanol-water partition coefficient (logKow) (Kim and Zoh 2016; Sibeko et al. 2019). The value of this coefficient for naproxen (3.2) indicates that this compound is hydrophobic (Vulava et al. 2016).

The fate of naproxen in the environment is affected by two phenomena: sorption and degradation (Liu et al. 2019; Martinez-Hernandez et al. 2016). The sorption process is strictly and inversely dependent on pH. Because naproxen has a carboxylic acid group that is deprotonated at an environmentally relevant pH (5–8), it occurs in the environment mainly in an anionic form. In this form, it can conjugate with the base forms in the aquatic and soil environments (Liu et al. 2019; Vulava et al. 2016). On the other hand, the electrostatic interactions of naproxen with negatively charged natural organic matter and clay mineral surfaces are difficult (Liu et al. 2019).

The basic changes that naproxen undergoes in surface waters are via its direct photochemical degradation and indirect photochemical pathways (Packer et al. 2003; Vulava et al. 2016). The intensity of photodegradation is affected by the intensity of light and the presence of nonorganic ions such as carbonate, nitrate, ferrous and ferric ions as well as organic matter, e.g. humic acids. Direct photochemical degradation of naproxen is possible because its UV absorption spectrum overlaps with the solar spectrum – > 290 nm (Sokół et al. 2017; Vulava et al. 2016). Its indirect photochemical degradation occurs when dissolved organic matter absorbs sunlight, which produces reactive oxygen species such as singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radicals or superoxide ions and other reactive species (Aguilar et al. 2019; Packer et al. 2003; Topp et al. 2008; Sokół et al. 2017; Vulava et al. 2016). Unfortunately, these processes lead to the formation of products that may be more persistent and more toxic (Vulava et al. 2016).

The impact of naproxen on nontarget organisms

It is well known that pharmaceuticals present in the environment may have a negative ecotoxicological effect. Naproxen can affect the organisms inhabiting ecosystems either through its toxicity to an organism or via the toxicity of its metabolites. The latter can be formed during both physicochemical and biological processes (Jallouli et al. 2016; Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al. 2011). One of the most important aspects of studies on pollutant degradation is the increased toxicity of the degradation products. The photoderivatives of naproxen have been reported as being more toxic than the parent compound to Brachionus calyciflorus, Thamnocephalus platyurus, Ceriodaphnia dubia, Vibrio fischeri and Daphnia magna (DellaGreca et al. 2004; Jallouli et al. 2016). DellaGreca et al. (2004) showed that naproxen photoderivatives with a lower molecular weight such as the ethyl, carbinol, ketone and olefin derivatives are more active against bacteria than dimeric photoproducts. Moreover, the toxicity of its dimers is stereo-dependent (DellaGreca et al. 2004). Ma et al. (2014) reported that during simulated solar radiation, the generated product of naproxen photodegradation was more toxic than the parent compound. Its toxicity is probably connected with a loss of the chemical moieties of naproxen resulting in a lower steric effect and easier penetration into the cells of Vibrio fischeri (Ma et al. 2014). However, it was also demonstrated that the solar photocatalysis of naproxen partially reduces its acute toxicity (Jallouli et al. 2016; Marotta et al. 2013).

Many studies have indicated the negative effects of naproxen on aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates. It was shown that naproxen can accumulate in the bile of fishes where its concentration was 1000 times higher than this detected in samples of the lake (Brozinski et al. 2012). One explanation for the naproxen bioaccumulation may be the suppression of the metabolizing enzyme activity (Xu et al. 2019). Moreover, the presence of phase II metabolites in fish bile such as glucuronides was also detected. These intermediates undergo enzymatic deconjugation (Brozinski et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2019). It was also shown that naproxen at environmental concentrations may affect the mRNA expression and cause gastrointestinal and renal effects in zebrafish (Ding et al. 2017). A 14-day exposure to 10 μg/L of naproxen resulted in an altered gene expression in the gill tissue of zebrafish (Li et al. 2016). Li et al. (2016) observed that zebrafish embryos (LC50 = 115.2 mg/L) were more sensitive to naproxen than the larvae (LC50 = 147.6 mg/L). It was also shown that the larval zebrafish liver was particularly sensitive to naproxen. The hepatic reactions to the drug included a swelling of hepatic cells, hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration, and nuclei pycnosis and obscure cell borders were also observed. These reactions in fish may be connected with a modification of the organelles structure and an elevated stress level and could be a sign of the mobilization of an organism to detoxification. Moreover, a lower heart rate, pericardial oedema and teratogenic effects that are induced by naproxen may be connected with the inhibition of cyclooxygenases in Danio rerio. It is postulated that prostaglandins, which are products of the reactions that are catalysed by cyclooxygenases (COX), are necessary for proper heart formation (Li et al. 2016). It has also been postulated that naproxen may cause thyroid disruption in zebrafish because of the relatively high degree of similarity of the thyroid axis between humans and fishes. Xu et al. (2019) demonstrated a decrease in the thyroid hormone levels in zebrafish after exposure to naproxen. They postulated that this phenomenon resulted from a disturbance in the gene transcription along the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and a significant decrease in transthyretin level (Xu et al. 2019).

It was shown a decrease in egg fertilization of Jordanella floridae over one complete life cycle occurred 121 days after exposure to 0.1 μg/L of naproxen. A low concentration of naproxen may also inhibit the growth of crustaceans such as Ceriodaphnia dubia after 7 days of exposure (Li et al. 2016).

Górny et al. (2019a) estimated the mean value of the microbial toxic concentration MTCavg, which is equivalent EC50 on the 1.66 g/L level using the MARA test with model organisms. This value indicated a low toxicity of naproxen for bacteria, which was probably connected with the lack of a proper carrier of naproxen in bacterial cells. Moreover, changes in the composition of the total fatty acids of Bacillus thuringiensis B1 were also observed (2015b). After incubation of B1 strain in the presence of naproxen, there was a significant increase in the value of the ratio of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The occurrence of the 16:0 iso 3OH fatty acid in bacterial cell membrane may stabilize its structure by interacting with the membrane protein (Górny et al. 2019a). The EC50 values that were estimated for Chlorella vulgaris and Ankistrodesmus falcatus were 40 mg/L after 24 h of exposure to naproxen (Ding et al. 2017). Ding et al. (2017) showed that the toxicity of naproxen on two algae, Cymbella species and Scenedesmus quadricauda, depended on its concentration and the duration of the incubation. The inhibition of growth increased together with the concentration of naproxen and decreased as the duration of the exposure increased. Moreover, a significant decrease in chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and carotenoids was also observed. Naproxen decreased the number of enzymatic antioxidants, which led to a greater accumulation of OH− and H2O2. At the same time, there was an increase of the malondialdehyde concentration. This compound may interact with biomolecules such as proteins, lipoproteins and DNA (Ding et al. 2017). Garcia-Medina et al. 2015 showed an increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, which was connected with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) after Hyalella azteca was exposed to naproxen. They suggested that the increase in SOD activity led to an increase in the hydrogen peroxide concentration and, as a result, to an increase in the activity of catalase. Oxidative stress damaged the genetic material of Hyalella azteca probably via the direct interaction of reactive oxygen species with DNA (Garcia-Medina et al. (2015). The genotoxicity of naproxen at a higher concentration was also observed by Górny et al. (2019a). However, this effect was not dose-dependent (Górny et al. 2019a).

Although low concentrations of naproxen occur in the environment, the increase in its toxicity may be related to a synergy effect with other contaminations. Zdarta et al. (2019) examined the toxicity of untreated and enzymatically treated solutions of naproxen and diclofenac against Artemia salina. However, they observed that after 24 h, the EC30 (the concentration of the drug at which 30% of the microorganisms showed a positive response after the exposure time) values for untreated naproxen and diclofenac solutions amounted around 20% and 25%, respectively. Enzymatic treatment with encapsulated laccase resulted in decreasing the EC30 values to around 80% and 85% for diclofenac and naproxen, respectively (Zdarta et al. 2019). A decrease in the toxicity was also observed by Marco-Urrea et al. (2010) and Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al. (2011) during the treatment of naproxen effluent using Trametes versicolor. A standard toxicity test using Vibrio fischeri showed a significant toxicity for naproxen at 10 mg/L only for the uninoculated control (EC50 amounted to 33% after 15 min of exposure) (Marco-Urrea et al. 2010).

Cleuvers (2004) showed that predicting the toxicity of a mixture is also indispensable because pharmaceuticals very rarely occur as a single contamination in the environment. When the concentrations of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that are used in a mixture were compared to the individual compound, no observable effect concentrations (NOECs) of the single drugs revealed that considerable combination effect may occur even if substances were applied in concentrations below their NOEC (Cleuvers 2004). This observation was confirmed by Melvin et al. (2014) during research on Limnodynastes peronei. They observed an interactive effect of naproxen, carbamazepine and sulfamethoxazole on amphibian growth and development at environmental concentrations (Melvin et al. 2014). Jiang et al. (2017) showed that a mixture of naproxen, diclofenac and ibuprofen led to an increase in bacterial diversity in a sequencing batch reactor. According to the Shannon-Wiener diversity index, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes were enriched, whereas the number of Micropruina and Nakamurella decreased after the addition NSAIDs. Moreover, they observed damage in the cell wall of the microorganisms (Jiang et al. 2017). On the other hand, Grenni et al. (2014) showed that the chronic exposure to naproxen of the natural microbial community of the Tiber River caused a decrease in β-Proteobacteria especially ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and the Archaea. At the same time, an increase in α- and γ-Proteobacteria was observed. It is speculated that these last two are involved in naproxen biodegradation (Grenni et al. 2014). Due to the potential risk to organisms living in naproxen-contaminated environments, it is necessary to seek effective methods for its removal.

Microbial decomposition of naproxen

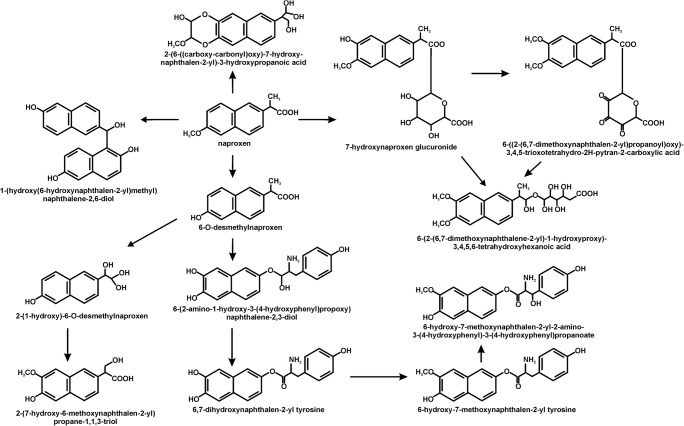

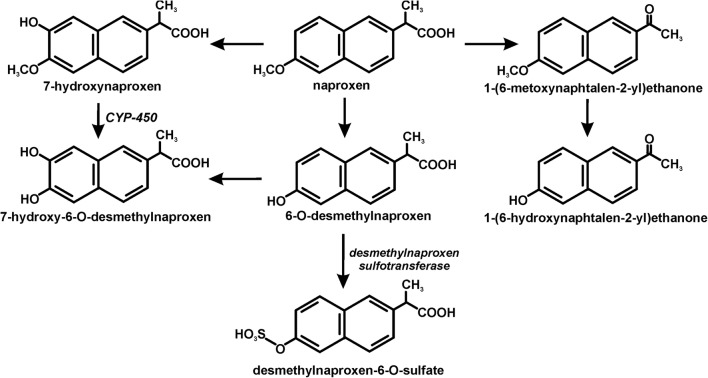

Despite the increase in interest in the breakdown of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, ketoprofen and diclofenac in recent years, relatively little is known about the microbiological breakdown of naproxen. This is due to the relatively high stability of naproxen and its resistance to microbial degradation, which is connected with the presence of two condensed rings. This has been confirmed by the research that has been carried out to date. These show that most often there is only a microbiological transformation of naproxen, during which the aromatic rings are not cleaved (Domaradzka et al. 2015b). The transformation of naproxen is performed by bacteria, fungi and algae. Ding et al. (2017) observed the transformation of naproxen by the freshwater algae Cymbella sp. and Scenedesmus quadricauda. They identified 12 metabolites that had resulted from the hydroxylation, decarboxylation, demethylation, tyrosine conjugation and glucuronidation of naproxen (Fig. 2). Among the fungi, only Aspergillus niger, Trametes versicolor, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Myceliophthora thermophile, Cunninghamella blakeslesna AS 3.153, Cunninghamella echinulata AS 3.2004, Cunninghamella elegans AS 3.156, Bjerkandera adusta and Bjerkandera sp. R1 can decompose naproxen (Jureczko and Przystaś 2018; Lloret et al. 2010; Marco-Urrea et al. 2010; Rodarte-Morales et al. 2011; Rodarte-Morales et al. 2012; Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al. 2010; Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al. 2011; Tran et al. 2010; Zhong et al. 2003). The transformation of naproxen by fungi is accompanied by the involvement of the extracellular oxidative enzymes such as laccase, manganese peroxidase, lignin peroxidase and versatile peroxidase (Lloret et al. 2010; Rodarte-Morales et al. 2012). Moreover, Marco-Urrea et al. (2010) showed that cytochrome P-450 might also play a role in the transformation of naproxen. The key metabolites that were observed included 7-hydroxynaproxen, 7-hydroxy-6-O-desmethylnaproxen, desmethylnaproxen, desmethylnaproxen-6-O-sulfate, 1-(6-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)ethanone, 1-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)ethanone (Fig. 3) (He and Rosazza 2003; Marco-Urrea et al. 2010; Qurie et al. 2013; Rodarte-Morales et al. 2012; Zhong et al. 2003). The efficiency of the transformation of naproxen by fungi is almost 100%. Moreover, Tran et al. (2010) showed that commercial laccase is more effective than crude laccase from Trametes versicolor.

Fig. 2.

The decomposition pathways of naproxen in algae (Ding et al. 2017)

Fig. 3.

The decomposition pathways of naproxen in fungi (He and Rosazza 2003; Marco-Urrea et al. 2010; Qurie et al. 2013; Rodarte-Morales et al. 2012; Zhong et al. 2003)

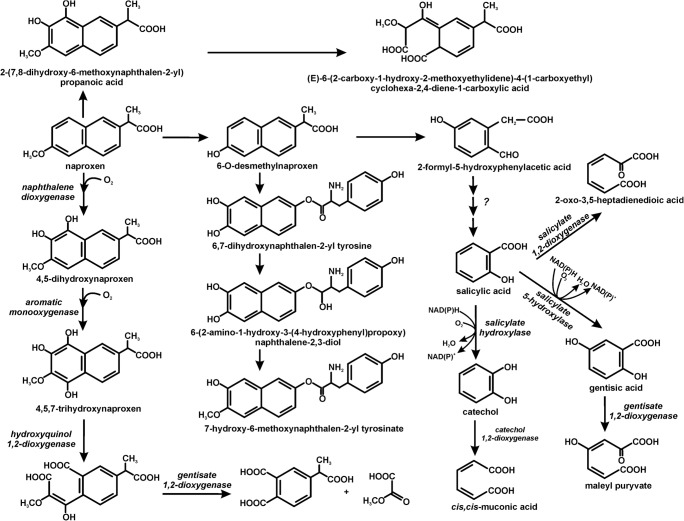

The total degradation of naproxen by pure strains was observed only in bacterial cultures: Planococcus sp. S5, Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia KB2 and Pseudoxanthomonas sp. DIN-3 (Domaradzka et al. 2015a; Górny et al. 2019b; Lu et al. 2019; Marchlewicz et al. 2016; Wojcieszyńska et al. 2014). The degradation of naproxen in monosubstrate conditions occurred with a low efficiency. However, the presence of an additional carbon source such as glucose, phenol, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid or 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid increased the effectiveness of this process (Górny et al. 2019a; Wojcieszyńska et al. 2014). Similar results were obtained by Lu et al. (2019). In cometabolic conditions with acetate, glucose or methanol, the DIN-3 strain degraded naproxen with a higher efficiency than in monosubstrate conditions. Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase is involved in the cleavage of naproxen in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia KB2 and Planococcus sp. S5 (Wojcieszyńska et al. 2014; Wojcieszyńska et al. 2016). Liu et al. (2019) proposed the transformation of naproxen by eliminating the methyl group. The O-desmethylnaproxen that is formed may conjugate with tyrosine to 6,7-dihydroxynaphthalene-2-yl-tyrosine. Naproxen can also be degraded via its hydroxylation to 2-(7,8-dihydroxy-6-methoxynaphthalene-2-yl) propanoic acid, which may subsequently undergo ring opening. The final product is (E)-6-(2-carboxy-1-hydroxy-2-methoxyethylidene)-4-(-1carboxyrthyl) cyclohexa-2,4-diene-1-carboxylic acid (Lu et al. 2019). The best described is the naproxen degradation pathway in Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b), which occurs via demethylation to O-desmethylnaproxen. This metabolite is converted to 2-formyl-5-hydroxyphenyl-acetate. Another identified metabolite of this pathway is salicylic acid, which is cleaved by salicylate 1,2-dioxygenase or is hydroxylated to catechol or gentisic acid. The pathway with catechol as an intermediate, which is cleaved to cis,cis-muconic acid involved in central metabolism, probably dominates in this strain (Górny et al. 2019b). The microbial pathways of naproxen decomposition are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The biodegradation pathways of naproxen in bacteria (Domaradzka et al. 2015a; Górny et al. 2019b; Liu et al. 2019; Lu et al. 2019; Marchlewicz et al. 2016; Wojcieszyńska et al. 2014)

Studies with mixed populations of microorganisms indicate a higher efficiency of naproxen degradation using monocultural systems. The natural microbial community in the Tiber River degraded 0.1 mg/l naproxen within about 40 days, although there was a transient negative effect on this community (Grenni et al. 2014). Moreover, Caracciolo et al. (2012) observed the ability of an autochthonous bacterial community in river water to completely eliminate naproxen over the course of 30 days. In turn, Quintana et al. (2005) showed that in the presence of powdered milk, 20 mg/l of naproxen was transformed by 50% by the active sludge in a membrane bioreactor. It was also demonstrated that naproxen degradation can occur under anaerobic conditions (Lahti and Oikari 2011).

Conclusion

Analysis of the current state of knowledge indicates that due to the increasing intake of naproxen, the problem of its occurrence in the environment will continue to increase. Toxicological studies indicate that long-term exposure to environmental doses may negatively affect the organisms that live in a habitat, especially if naproxen co-occurs with other drugs. The vast majority of literature reports indicate the transformation of naproxen without decomposition of condensed aromatic rings. Another problem is the appearance of hydroxylated derivatives of naproxen as a result of transformation, which may have a more negative impact on living organisms, due to their greater hydrophilicity. To date, only a few bacterial strains possessing enzymes of the full naproxen degradation pathway have been described. However, compared to monocyclic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, the level of naproxen degradation is definitely lower. Therefore, it is still necessary to search for the strains and consortia of microorganisms that have an increased potential to degrade naproxen.

Author contributions

DW prepared of subchapters “Occurrence of naproxen in the environment” and “Microbial decomposition of naproxen”; UG prepared of subchapter “The impact of naproxen on non-target organisms” and drew figures; DW and UG critically revised the work.

Funding information

This work was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant number 2018/29/B/NZ9/00424).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This work did not involve the direct study of humans or animals.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Addison RS, Parker-Scott SL, Hooper WD, Eadie MJ, Dickinson RG. Effect of naproxen co-administration on valproate disposition. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2000;21:235–242. doi: 10.1002/bdd.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar CM, Chairez I, Rodriguez JL, Tiznado H, Santillan R, Arrieta D, Poznyak T. Inhibition effect of ethanol in naproxen degradation by catalytic ozonation with NiO. RSC Adv. 2019;9:14822–14833. doi: 10.1039/c9ra02133g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiolillo DJ, Weisman SM. Clinical pharmacology and cardiovascular safety of naproxen. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2017;17(2):97–107. doi: 10.1007/s40256-016-0200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcella CA, Lamberts M, McGettigan P, Fosbol EL, Lindhardsen J, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH, Olsen AS. Differences in cardiovascular safety with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy-a nationwide study in patients with osteoarthritis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124:629–641. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotti MJ, Trenholm RA, Vanderford BJ, Holady JC, Stanford BD, Snyder SA. Pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. drinking water. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:597–603. doi: 10.1021/es801845a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozinski JM, Lahti M, Aeierjohann A, Oikari A, Kronberg L. The anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac, naproxen and ibuprofen are found in the bile of wild fish caught downstream of a wastewater treatment plant. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;47:342–348. doi: 10.1021/es303013j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caracciolo AB, Patrolecco L, Di Lenola M, Battaglia A, Grenni P. Degradation of emerging pollutants in aquatic ecosystems. Chem Eng Trans. 2012;28:37–42. doi: 10.3303/CET1228007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleuvers M. Mixture toxicity of the anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen and acetylsalicylic acid. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004;59:309–315. doi: 10.1016/S0147-6513(03)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinCalc.com. ClinCalc DrugStats database. clincalc.com/DrugStats. Accessed October 1, 2019

- DellaGreca M, Brigante M, Isidori M, Nardelli A, Previtera L, Rubino M, Temussi F. Phototransformation and ecotoxicity of the drug naproxen-Na. Environ Chem Lett. 2004;1:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s10311-003-0045-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Lin K, Yang B, Yang M, Li J, Li W, Gan J. Biodegradation of naproxen by freshwater algae Cymbella sp. and Scenedesmus quadricauda and the comparative toxicity. Bioresour Technol. 2017;238:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domaradzka Dorota, Guzik Urszula, Wojcieszyńska Danuta. Biodegradation and biotransformation of polycyclic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology. 2015;14(2):229–239. doi: 10.1007/s11157-015-9364-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domaradzka D, Guzik U, Hupert-Kocurek K, Wojcieszyńska D. Cometabolic degradation of naproxen by Planococcus sp. strain S5. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015;226:297. doi: 10.1007/s11270-015-2564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzionek A, Wojcieszyńska D, Hupert-Kocurek K, Adamczyk-Habrajska M, Guzik U. Immobilization of Planococcus sp. S5 strain on the loofah sponge and its application in naproxen removal. Catalysts. 2018;8:176. doi: 10.3390/catal8050176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Medina AL, Galar-Martinez M, Garcia-Medina S, Gomez-Olivan LM, Razo-Estrada C. Naproxen-enriched artificial sediment induces oxidative stress and genotoxicity in Hyalella azteca. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015;226:195–110. doi: 10.1007/s11270-015-2454-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Górny D, Guzik U, Hupert-Kocurek K, Wojcieszyńska D. Naproxen ecotoxicity and biodegradation by Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;167:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górny D, Guzik U, Hupert-Kocurek K, Wojcieszyńska D. A new pathway for naproxen utilisation by Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b) and its decomposition in the presence of organic and inorganic contaminants. J Environ Manag. 2019;239:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenni P, Patrolecco L, Ademollo N, Tolomei A, Caracciolo AB. Degradation of gemfibrozil and naproxen in a river water ecosystem. Microchem J. 2013;107:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2012.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grenni P, Patrolecco L, Ademollo N, Di Lenola M, Caracciolo AB. Capability of the natural microbial community in a river water ecosystem to degrade the drug naproxen. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21:13470–13479. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A, Rosazza JPN. Microbial transformation of S-naproxen by Aspergillus niger ATCC 9142. Pharmazie. 2003;58:420–422. doi: 10.1002/chin.200339085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallouli N, Elghniji K, Hentati O, Ribeiro AR, Silva AMT, Ksibi M. UV and solar photo-degradation of naproxen: TiO2 catalyst effect, reaction kinetics, products identification and toxicity assessment. J Hazard Mater. 2016;304:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, Liu X, Lee S, Kang S, Kho Y, Giesy JP, Choi K. Effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on hormones and genes of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonad axis and reproduction of zebrafish. J Hazard Mater. 2013;254-255:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Geng J, Hu H, Ma H, Gao X, Ren H. Impact of selected non-steroidal anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals on microbial community assembly and activity in sequencing batch reactor. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jureczko M, Przystaś W. Pleurotus ostreatus and Trametes versicolor, fungal strains as remedy for recalcitrant pharmaceuticals removal current knowledge and future perspectives. Miomed J Sci & Tech res. 2018;3(3):BJSTR.MS.ID.000903. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.03.000903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Zoh KD. Occurrence and removals of micropollutants in water environment. Environ Eng Res. 2016;21:319–332. doi: 10.4491/eer.2016.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti M, Oikari A. Microbial transformation of pharmaceuticals naproxen, bisoprolol and diclofenac aerobic and anaerobic environments. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2011;61:202–210. doi: 10.1007/s00244-010-9622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang P, Chen L, Gao H, Wu L. Acute toxicity and histopathological effects of naproxen in zebrafish (Danio rerio) early life stages. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:18832–18841. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Mielsen AH, Vollertsen J. Sorption and degradation potential of pharmaceuticals in sediments form a stormwater retention pond. Water. 2019;11:526. doi: 10.3390/w11030526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloret L, Eibes G, Lu-Chau TA, Moreira MT, Feijoo G, Lema JM. Laccase-catalyzed degradation of anti-inflammatories and estrogens. Biochem Eng J. 2010;51:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2010.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Sun W, Li C, Ao X, Yang C, Li S. Bioremoval of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by Pseudoxanthomonas sp. DIN-3 isolated from biological activated carbon process. Water Res. 2019;161:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Liu G, Lv W, Yao K, Zhang X, Xiao H. Photodegradation of naproxen in water under simulated solar radiation: mechanism, kinetics and toxicity variation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21:7797–7804. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madikizela LM, Mdluli PS, Chimuka L. An initial assessment of naproxen, ibuprofen and diclofenac in Ladysmith water resources in South Africa using molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction followed by high performance liquid chromatography-photodiode array detection. S Afr J Chem. 2017;70:145–153. doi: 10.17159/0379-4350/2017/v70a21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marchlewicz A, Domaradzka D, Guzik U, Wojcieszyńska D. Bacillus thuringiensis B1(2015b) is a gram-positive bacteria able to degrade naproxen and ibuprofen. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016;227:197. doi: 10.1007/s11270-016-2893-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Urrea E, Perez-Trujillo M, Blanquez P, Vicent T, Caminal G. Biodegradation of analgesic naproxen by Trametes versicolor and identification of intermediates using HPLC-DAD-MS and NMR. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:2159–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta R, Spasiano D, Di Somma I, Andreozzi R. Photodegradation of naproxen and its photoproducts in aqueous solution at 254 nm: a kinetic investigation. Water Res. 2013;47:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez V, Meffe R, Lopez SH, de Bustamante I. The role of sorption and biodegradation in the removal of acetaminophen, carbamazepine, caffeine, naproxen and sulfamethoxazole during soil contact: a kinetics study. Sci Total Environ. 2016;559:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin SD, Cameron MC, Lanctot CM. Individual and mixture toxicity of pharmaceuticals naproxen, carbamazepine and sulfamethoxazole to Australian striped marsh frog tadpoles (Limnodynastes peronii) J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2014;77:337–345. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2013.865107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer JL, Werner JJ, Latch DE, McNeill K, Arnold WA. Photochemical fate of pharmaceuticals in the environment: naproxen, diclofenac, clofibric acid and ibuprofen. Aquat Sci. 2003;65:342–351. doi: 10.1007/s00027-003-0671-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana JB, Weiss S, Reemtsma T. Pathways and metabolites of microbial degradation of selected acidic pharmaceutical and their occurrence in municipal wastewater treated by a membrane bioreactor. Water Res. 2005;39:2654–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qurie M, Khamis M, Malek F, Mir S, Abufo-Jihad Abbadi SA, Scrano L, Karaman R. Stability and removal of naproxen and its metabolite by advanced membrane wastewater treatment plant and micelle-clay complex. Clean Soil Air Water. 2013;41:1–7. doi: 10.1002/clen.201300179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodarte-Morales AI, Feijoo G, Moreira MT, Lema JM. Degradation of selected pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) by white-rot fungi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27:1839–1846. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0642-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodarte-Morales AI, Feijoo G, Moreira MT, Lema JM. Biotransformation of three pharmaceutical active compounds by the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium in a fed batch stirred reactor under air and oxygen supply. Biodegradation. 2012;23:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s10532-011-9494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez CE, Marco-Urrea E, Caminal G. Degradation of naproxen and carbamazepine in spiked sludge by slurry and solid-phase Trametes versicolor systems. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:2259–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez CE, Jelić A, Llorca M, Farre M, Caminal G, Petrović M, Barceló D, Vicent T. Solid-phase treatment with the fungus Trametes versicolor substantially reduces pharmaceutical concentrations and toxicity from sewage sludge. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:5602–5608. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam G, Sampath S, Selvaraj KK, Larsson DGJ, Ramaswamy BR. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Indian rivers. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21:921–231. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-1957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibeko PA, Naicker D, Mdluli PS, Madikizela LM. Naproxen, ibuprofen and diclofenac residues in river water, sediments and Eichhornia crassipes of Mbokodweni river in South Africa: an initial screening. Environ Forensic. 2019;20:129138. doi: 10.1080/15275922.2019.1597780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokół A, Borowska K, Karpińska J. Investigating the influence of some environmental factors on the stability of paracetamol, naproxen and diclofenac in simulated natural conditions. Pol J Environ Stud. 2017;26:293–302. doi: 10.15244/pjoes/64310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straub JO, Stewart K. Deterministic and probabilistic acute-based environmental risk assessment for naproxen for Western Europe. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2007;26:795–806. doi: 10.1897/06-212r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kosugi Y, Hosaka M, Nishimura T, Nakae D. Occurrence and behaviour of the chiral anti-inflammatory drug naproxen in an aquatic environment. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33:2671–2678. doi: 10.1002/etc.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp E, Hendel JG, Lapen DR, Chapman R. Fate of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen in agricultural soil receiving liquid municipal biosolids. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27:2005–2010. doi: 10.1897/07-644.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NH, Urase T, Kusakabe O. Biodegradation characteristics of pharmaceutical substances by whole fungal culture Trametes versicolor and its laccase. J Water Environ Technol. 2010;8:125–139. doi: 10.2965/jwet.2010.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vulava VM, Cory WC, Murphey VL, Ulmer CZ. Sorption, photodegradation and chemical transformation of naproxen and ibuprofen in soils and water. Sci Total Environ. 2016;565:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszyńska D, Domaradzka D, Hupert-Kocurek K, Guzik U. Bacterial degradation of naproxen – undisclosed pollutant in the environment. J Environ Manag. 2014;145:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszyńska D, Domaradzka D, Hupert-Kocurek K, Guzik U. Enzymes involved in naproxen degradation by Planococcus sp. S5. Pol J Microbiol. 2016;65:177–182. doi: 10.5604/17331331.1204477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Niu L, Guo H, Sun X, Chen L, Tu W, Dai Q, Ye J, Liu W, Liu J. Long-term exposure to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) naproxen causes thyroid disruption in zebrafish at environmentally relevant concentrations. Sci Total Environ. 2019;676:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdarta J, Jankowska K, Wyszowska M, Kijeńska-Gawrońska E, Zgoła-Grześkowiak A, Pinelo M, Meyer AS, Moszyński D, Jesionowski T. Robust biodegradation of naproxen and diclofenac by laccase immobilized using electrospun nanofibers with enhanced stability and reusability. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;103:109789. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong DF, Sun L, Liu L, Huang HH. Microbial transformation of naproxen by Cunninghamella species. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24:442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]