Abstract

Background

Despite the existence of effective interventions and best‐practice guideline recommendations for childcare services to implement evidence‐based policies, practices and programmes to promote child healthy eating, physical activity and prevent unhealthy weight gain, many services fail to do so.

Objectives

The primary aim of the review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies aimed at improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention. The secondary aims of the review were to:

1. Examine the cost or cost‐effectiveness of such strategies; 2. Examine any adverse effects of such strategies on childcare services, service staff or children; 3. Examine the effect of such strategies on child diet, physical activity or weight status.

4. Describe the acceptability, adoption, penetration, sustainability and appropriateness of such implementation strategies.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases on February 22 2019: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, CINAHL and SCOPUS for relevant studies. We searched reference lists of included studies, handsearched two international implementation science journals, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Selection criteria

We included any study (randomised or nonrandomised) with a parallel control group that compared any strategy to improve the implementation of a healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme by staff of centre‐based childcare services to no intervention, 'usual' practice or an alternative strategy. Centre‐based childcare services included preschools, nurseries, long daycare services and kindergartens catering for children prior to compulsory schooling (typically up to the age of five to six years).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened study titles and abstracts, extracted study data and assessed risk of bias; we resolved discrepancies via consensus. We performed meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model where studies with suitable data and homogeneity were identified; otherwise, findings were described narratively.

Main results

Twenty‐one studies, including 16 randomised and five nonrandomised, were included in the review. The studies sought to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes targeting healthy eating (six studies), physical activity (three studies) or both healthy eating and physical activity (12 studies). Studies were conducted in the United States (n = 12), Australia (n = 8) and Ireland (n = 1). Collectively, the 21 studies included a total of 1945 childcare services examining a range of implementation strategies including educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, reminders and tailored interventions. Most studies (n = 19) examined implementation strategies versus usual practice or minimal support control, and two compared alternative implementation strategies. For implementation outcomes, six studies (one RCT) were judged to be at high risk of bias overall.

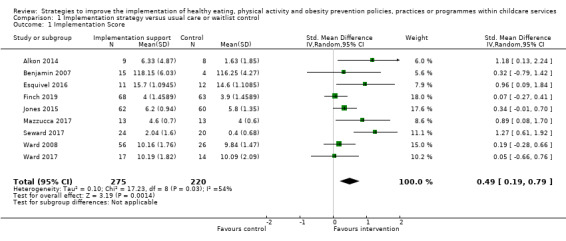

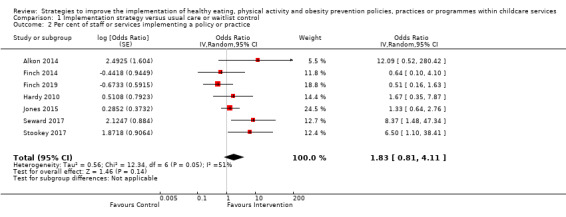

The review findings suggest that implementation strategies probably improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention in childcare services. Of the 19 studies that compared a strategy to usual practice or minimal support control, 11 studies (nine RCTs) used score‐based measures of implementation (e.g. childcare service nutrition environment score). Nine of these studies were included in pooled analysis, which found an improvement in implementation outcomes (SMD 0.49; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.79; participants = 495; moderate‐certainty evidence). Ten studies (seven RCTs) used dichotomous measures of implementation (e.g. proportion of childcare services implementing a policy or specific practice), with seven of these included in pooled analysis (OR 1.83; 95% CI 0.81 to 4.11; participants = 391; low‐certainty evidence).

Findings suggest that such interventions probably lead to little or no difference in child physical activity (four RCTs; moderate‐certainty evidence) or weight status (three RCTs; moderate‐certainty evidence), and may lead to little or no difference in child diet (two RCTs; low‐certainty evidence). None of the studies reported the cost or cost‐effectiveness of the intervention. Three studies assessed the adverse effects of the intervention on childcare service staff, children and parents, with all studies suggesting they have little to no difference in adverse effects (e.g. child injury) between groups (three RCTs; low‐certainty evidence). Inconsistent quality of the evidence was identified across review outcomes and study designs, ranging from very low to moderate.

The primary limitation of the review was the lack of conventional terminology in implementation science, which may have resulted in potentially relevant studies failing to be identified based on the search terms used.

Authors' conclusions

Current research suggests that implementation strategies probably improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services, and may have little or no effect on measures of adverse effects. However such strategies appear to have little to no impact on measures of child diet, physical activity or weight status.

Plain language summary

Improving the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes in childcare services

The review question This review aimed to look at the effects of strategies to improve the implementation (or correct undertaking) of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote children's healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention. We wanted to determine the cost or cost‐effectiveness of providing implementation support, whether support strategies were associated with any adverse effects, and whether there was an impact on child nutrition, physical activity or weight status. We also looked at the implementation strategy acceptability, adoption, penetration, sustainability and appropriateness. Background A number of childcare service‐based interventions have been found to be effective in improving child diet, increasing child physical activity and preventing excessive weight gain. Despite the existence of such evidence and best‐practice guideline recommendations for childcare services to implement these policies, practices or programmes, many childcare services fail to do so. Without proper implementation, children will not benefit from these child health‐directed policies, practices or programmes. Study characteristics We identified 21 studies, 19 of which examined implementation strategies versus usual practice or minimal support control, and two that compared different types of implementation strategies. The studies sought to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes targeting healthy eating (six studies), physical activity (three studies) or both healthy eating and physical activity (twelve studies). Collectively, the 21 included studies included a total of 1945 childcare services and examined a range of implementation strategies including educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, reminders and tailored interventions. The strategies tested were only a small number of those that could be applied to improve implementation in this setting. Search date The evidence is current to February 2019. Key results

Findings suggest that implementation support strategies can improve the implementation of physical activity policies, programmes or practices by childcare services or their staff (moderate‐certainty evidence), and do not appear to increase the risk of child injury (low‐certainty evidence). However, such approaches do not appear to have an impact on the diet, physical activity or weight status of children (low to moderate‐certainty evidence). None of the included studies reported information regarding implementation strategy costs or measures of cost‐effectiveness. The lack of consistent terminology in this area of research may have meant some relevant studies were not picked up in our search.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children up to the age of 6 years Settings: centre‐based childcare services that cater for children prior to compulsory schooling Intervention: any strategy (educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, reminders and tailored interventions) with the primary intent of improving the implementation (by usual service staff) of policies, practices or programmes in centre‐based childcare services to promote healthy eating, physical activity or prevent unhealthy weight gain Comparison: usual practice or minimal support control (19 studies) or alternate intervention (2 studies) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|

Risk with usual care or waiting‐list control |

Risk difference with Implementation strategy | |||||

| Implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention | mean score of 10.09 on the EPAO scalea | SMD of 0.49 is equivalent to a mean difference of 0.88 on the EPAO scale (95% CI 0.34 to 1.42) | SMD = 0.49 (0.19 to 0.79) |

495 participants (childcare services), 9 RCTs; reporting score‐based measures | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

Including nine RCTs reporting score‐based measures, all conducted in high‐income countries. In addition to score‐based measures of implementation reported here, the included randomised trials also reported improvement (effect uncertain) in the per cent of services or staff implementing a policy or practice (OR 1.83, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.11; participants = 391 childcare services; low‐certainty evidence), mixed effects for two randomised trials reporting time or frequency‐based measures (participants = 49 childcare services; low‐certainty evidence) and mixed effects for three randomised trials reporting quantity measures of implementation (foods served to children) (participants = 171 childcare services; low‐certainty evidence). Implementation strategies probably improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/ or obesity prevention. |

| Cost or cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies were found that looked at the cost or cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services. |

| Adverse consequences of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 148 participants (childcare services), 2 RCTs; reporting continuous outcomes (rates of child injury) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low b,c |

Including two RCTs, both conducted in high‐income countries. Across the two RCTs that reported continuous measures of adverse effects (rates of child injury) there were no clear differences reported between groups in rates of child injuries. Similarly, there was no difference between groups in a single trial reporting dichotomous outcomes (reported complaints received by services) (participants = 45 childcare services; very low‐certainty evidence). Strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention may have little to no impact on measures of adverse consequences. |

| Measures of child diete | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 134 participants from 182 childcare services), 2 RCTs, reporting continuous (serve‐based measures) of dietary intake | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d |

Including two RCTs, both conducted in high‐income countries. Findings regarding beneficial effects for this outcome were mixed across the two randomised trials. Strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention may lead to little or no difference in child diet intake. |

| Measures of child physical activityf | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 53 childcare services

(2 RCTs) reporting dichotomous observational outcomesg (no. children not reported) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec |

Including two RCTs, both conducted in high‐income countries. The two trials reporting dichotomous observation‐based measures of physical activity reported little to no improvement in student physical activity. Additionally, two trials using continuous and objective measures of child physical activity (e.g. pedometers) (participants = 420 children from 46 services; high‐certainty evidence) reported little to no improvement in student physical activity. Strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention probably lead to little or no difference in child physical activity. |

| Measures of child weight status | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 298 children from 66 childcare services

(2 RCTs) reporting continuous measures of BMI/zBMI |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate c |

Including two RCTs, both conducted in high‐income countries. The two trials reporting zBMI or BMI measures of weight status found mixed effects on this outcome. Additionally, one RCT reported a dichotomous measure of weight (% of children within different weight‐related categories) and found no differences between groups (participants = 209 children from 18 childcare services, low‐certainty evidence). Strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention may lead to little or no difference in child weight status. |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a Risk with usual care or waiting list control calculated as the mean Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation (EPAO) score for the control group as reported in Ward 2017

bDowngraded one level for risk of bias: studies assessed as high and unclear risk of bias for the majority of domains.

cDowngraded one level for inconsistency: narrative synthesis indicated a high level of inconsistency in results across studies and outcomes measured within studies.

dDowngraded one level for imprecision: total sample size < 400

eMeasures of child diet: included child consumption of food groups (e.g. fruit and vegetables) measured via weighed food records and researcher observations

fMeasures of child physical activity: included frequency and duration of child physical activity (e.g. step count), measured via pedometers, accelerometers and researcher observations

gDichotomous observational outcomes: included type and intensity of child physical activity (e.g. very active, walking, sedentary), measured via researcher observations

Background

Description of the condition

Internationally, the prevalence of being overweight or obese has increased across every region of the world in recent decades (Finucane 2011). Currently, over 1.9 billion adults and 340 million children are overweight or obese (World Health Organization 2018). While obesity rates in high‐income countries remain higher, prevalence rates in low‐ and middle‐income countries are accelerating (Swinburn 2011). In Africa, for example, the prevalence of being overweight among children under five years is expected to increase from 4% in 1990 to 11% by 2025 (Black 2013). Excessive weight gain increases the risk of a variety of chronic health conditions. Between the years 2010 and 2030, up to 8.5 million cases of diabetes, 7.3 million cases of heart disease and stroke, and 669,000 cases of cancer attributable to obesity have been projected in the USA and UK alone (Wang 2011). In Australia, between the years 2011 and 2050, 1.75 million lives and over 10 million premature years of life will be lost due to excessive weight gain (Gray 2009).

Description of the intervention

Physical inactivity and poor diet are key drivers of excessive weight gain. As excessive weight gain in childhood tracks into adulthood, interventions targeting children's diet and physical activity have been recommended to mitigate the adverse health effects of obesity on the population (World Health Organization 2012). A recently published World Health Organization report into population‐based approaches to childhood obesity prevention identified centre‐based childcare services (including preschools, long daycare services and kindergartens that provide educational and developmental activities for children prior to formal compulsory schooling) as an important setting for public health action to reduce the risk of unhealthy weight gain in childhood. Such settings provide an opportunity to access large numbers of children for prolonged periods of time (World Health Organization 2012). Further, randomised and nonrandomised studies have identified a number of interventions, delivered in childcare services, which have increased child physical activity and fundamental movement skill proficiency, improved child diet quality and prevented excessive weight gain (Brown 2019; Finch 2016; Stacey 2017). As such, regulations and best practice guidelines for the childcare sector recommend implementation of a number of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices, such as restricting sedentary screen time opportunities; ensuring meals provided by childcare services or foods packed by parents for consumption in care are consistent with dietary guidelines; and the provision of programmes to promote physical activity and fundamental movement skill development (Commonwealth of Australia; McWilliams 2009; Tremblay 2012).

Despite the existence of evidence‐based best‐practice guidelines for childcare services, implementation of obesity prevention policies and practices that are consistent with such guidelines is poor (McWilliams 2009; Wolfenden 2015a). In the USA, a menu audit in 83 childcare centres determined that the menus did not provide the recommended amount of carbohydrates, dietary fibre and iron, whilst providing excessive amounts of sodium (Frampton 2014). Childcare service adherence to dietary guidelines in other countries has also been reported to be poor (Grady 2018; Yoong 2014). Similarly, adherence to best‐practice recommendations for physical activity is also suboptimal. For example, only 14% of USA childcare services provided 120 minutes of active play per day, 57% to 60% did not have a written physical activity policy (McWilliams 2009; Sisson 2012), and in 18% of childcare services, children were seated for more than 30 minutes at a time (McWilliams 2009). In Australia, it has been reported that just 58% of centre‐based childcare services had written healthy eating and physical activity policies (Wolfenden 2015a), and 60% of child lunch boxes contained more than one serving of high‐fat, salt or sugar foods or drinks (Kelly 2010). Similarly in New Zealand, it has been reported that only 35% of childcare services had a written physical activity policy (Gerritsen 2016).

Without adequate implementation across the population of childcare services, the potential public health benefits of initiatives to improve healthy eating or physical activity, or prevent obesity, will not be fully realised. 'Implementation' is described as the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence‐based health interventions and to change practice patterns within specific settings (Glasgow 2012). Implementation research, specifically, is the study of strategies designed to integrate health policies, practices or programmes within specific settings (for example, primary care, community centres or childcare services) (Schillinger 2010). The National Institute of Health recognises implementation research as a fundamental component of the third stage of the research translation process ('T3') and that it is a necessary prerequisite for research to yield public health improvements (Glasgow 2012). While staff of centre‐based childcare services are responsible for providing educational experiences and an environment supportive of healthy growth and development, including initiatives designed to reduce the risk of excessive weight gain, it may be the childcare services themselves, government or other agencies (such as for licensing and accreditation requirements) that undertake strategies aimed at enhancing the implementation of such initiatives.

There are a range of potential strategies that can improve the likelihood of implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes in childcare services. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy is a framework for characterising educational, behavioural, financial, regulatory and organisational interventions (EPOC 2015); it includes three categories with 22 subcategories within the topic of 'implementation strategies'. Examples of such subcategories include continuous quality improvement, educational materials, performance monitoring, local consensus processes, and educational outreach visits (EPOC 2015).

How the intervention might work

The determinants of policy and practice implementation are complex and the mechanisms by which support strategies facilitate implementation are not well understood. Implementation frameworks have identified a large number of factors operating at multiple macro and micro levels that can influence the success of implementation (Damschroder 2009). However, few studies have been conducted in the childcare setting to identify key determinants of implementation in this setting. A study by Wolfenden and colleagues of over 200 childcare services in Australia examined associations between the existence of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices and 13 factors suggested by Damschroder's Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to impede or promote implementation (Wolfenden 2015a). The study reported that implementation policy and practice implementation was more likely when service managers, management committee and parents were supportive, and where external resources to support implementation were accessible. Applied implementation frameworks, such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (Michie 2008), suggest that strategies to facilitate implementation may be most likely to be effective with a thorough understanding of the local implementation context and barriers, and when theoretical frameworks are applied to select implementation support strategies to address key determinants of implementation. For example, knowledge barriers to implementation may be best overcome with education meetings or materials, while activity reminders, such as decision support systems, may be particularly important in instances where staff forgetfulness is identified as a local implementation barrier.

Why it is important to do this review

A number of large systematic reviews have been undertaken to assess the effectiveness of such implementation strategies in improving the professional practice of clinicians. For example, Ivers and colleagues reviewed the effectiveness of audit and feedback on the behaviour of health professionals and the health of their patients, and found such strategies generally resulted in small but important improvements in professional practice (Ivers 2012). Other reviews have examined the impact of printed education materials (Giguère 2012), reminders (Arditi 2012), education meetings and workshops (Forsetlund 2009; O'Brien 2007), incentives (Scott 2011), and other strategies on improving professional practice and implementation of evidence‐based interventions by clinicians. Public health implementation research in nonclinical community settings, while still sparse (Buller 2010), is emerging (Wolfenden 2016; Wolfenden 2019). Systematic reviews of the effects of strategies to implement interventions targeting risks of chronic disease in settings such as workplaces (Wolfenden 2018), sporting clubs (McFadyen 2018) and schools (Wolfenden 2017) report an acceleration in the number of published implementation studies over recent years. Such an increase is consistent with an increase in implementation research occurring more broadly in the field (Wilson 2017).

Similarly, our 2016 Cochrane systematic review examining the effects of implementation strategies in childcare identified just 10 studies, providing low‐certainty evidence. Since the conduct of this review, we are aware of a number of studies that are currently underway or have been completed (Finch 2019; Mazzucca 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2017). Given the current uncertainty of the existing evidence base, the importance of childcare as a setting for health promotion, and the need among policy makers and practitioners for evidence‐based implementation strategies for this setting, an update of the review is timely.

Objectives

The primary aim of the review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies aimed at improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention.

The secondary aims of the review were to:

Examine the cost or cost‐effectiveness of such strategies;

Examine any adverse effects of such strategies on childcare services, service staff or children;

Examine the effect of such strategies on child diet, physical activity or weight status;

Describe the acceptability, adoption, penetration, sustainability and appropriateness of such implementation strategies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any study (randomised, including cluster‐randomised, or nonrandomised) with a parallel control group that compared:

a strategy to improve the implementation of any healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme in centre‐based childcare services compared with no intervention or 'usual' practice;

two or more alternative strategies to improve the implementation of any healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme in centre‐based childcare services.

There was no restriction on the length of the study follow‐up period, language of publication or country of origin.

Types of participants

Centre‐based childcare services (and staff thereof) such as preschools, nurseries, long daycare services and kindergartens that cater for children prior to compulsory schooling (typically up to the age of five to six years). We excluded studies of childcare services provided in the home and specialised daycare services.

Types of interventions

Any strategy with the primary intent of improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in centre‐based childcare services to promote healthy eating, physical activity or prevent unhealthy weight gain was eligible. To be eligible, strategies must have sought to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by usual childcare service staff. Strategies could have included quality improvement initiatives, education and training, performance feedback, prompts and reminders, implementation resources, financial incentives, penalties, communication and social marketing strategies, professional networking, the use of opinion leaders, or implementation consensus processes. Interventions may have been singular or multi‐component.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We included any measure of either the completeness or the quality of the implementation of childcare service policies, practices or programmes (for example, the percentage of childcare services implementing a food service consistent with dietary guidelines or the mean number of physical activity practices implemented). To assess the review outcomes, data may have been collected from a variety of sources including educators, managers, cooks or other staff of centre‐based childcare services; or administrators, officials or other health, education, government or non‐government personnel responsible for encouraging or enforcing the implementation of health‐promoting initiatives in childcare services. Such data may have been obtained from audits of service records, questionnaires or surveys of staff, service managers, other personnel or parents; direct observation or recordings; examination of routine information collected from government departments (such as compliance with food standards or breaches of childcare service regulations) or other sources. Additionally, children, parents or childcare service staff may have provided information regarding child diet, physical activity or child weight status.

Secondary outcomes

Estimates of absolute costs or any assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services.

Any reported adverse consequences of a strategy to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services. This could include impacts on child health (for example, an increase in child injury following the implementation of physical activity‐promoting practices) or child development, service operation or staff attitudes (for example, impacts on staff motivation or cohesion) or the displacement of other key programmes, curricula or practices.

Any measure of child diet, physical activity (including sedentary behaviours) or weight status. Such measures could be derived from any data source including direct observation, questionnaire, or anthropometric assessments. We excluded studies focusing on malnutrition/malnourishment.

Any measure of acceptability, adoption, penetration, sustainability and appropriateness of the implementation support strategy (Proctor 2011). Such measures are typically included in the experimental arm of the study only, that is, those exposed to an implementation strategy or intervention. As such, we reported within‐group findings of these measures for completeness, to improve external validity and enable end‐user assessments of potential utility of strategies to implement an evidence‐based intervention. The definition of these outcomes were adapted, based on those defined by Proctor, to be as follows:

Acceptability: The perception among implementation stakeholders that a given policy, practice or programme or strategies to support its implementation is agreeable, palatable or satisfactory (Proctor 2011). Measures assessed at the individual or organisational level were included such a surveys of staff or managers of childcare services regarding their experience of features of the intervention or implementation strategy.

Penetration: The integration of a policy, practice or programme or strategies to support its implementation within a service setting or its sub settings. Penetration could be measured from the perspective of the provider, service or child individual. We included any measure of penetration at the individual or organisational level (Proctor 2011). For example, the proportion of eligible childcare services that received implementation support strategies, or the proportion of childrens' exposure to targeted intervention.

Adoption: The intention, including the initial decision, or action to try and implement a policy, practice or programme (Proctor 2011). Adoption could be measured from the perspective of the provider or service. These could include decisions by managers of childcare services to take up a potentially effective intervention, or decisions by individual childcare staff to deliver potential intervention components.

Sustainability: The extent to which a policy, practice or programme is maintained (Proctor 2011). Measures of sustainability must require successful implementation in part or in full, of an intervention, programme or service that is then sustained for a period of at least six months. This could include the proportion of childcare services maintaining implementation of targeted policy practices or programmes 12 months following the provision of implementation support.

Appropriateness: The perceived fit, relevance or compatibility of policy, practice or programme or strategies to support its implementation for a given setting, provider or consumer, and/or the perceived fit of the intervention to address a particular problem (Proctor 2011). Measures of appropriateness assessed at the individual or organisational level will be included, such as surveys of staff or managers of childcare services regarding their perception of the congruence of the implementation of a targeted policy, practice or programme with their skill set or work expectations.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted searches for peer‐reviewed articles in electronic databases. We also undertook handsearching within relevant journals and reference lists of included studies.

Electronic searches

For this update, we conducted searches in the following electronic databases on February 22, 2019: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL) (2019) via Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (1946 to February 22, 2019), MEDLINE In Process (February 22, 2019), PsycINFO (1950 to February 22, 2019) and Embase (1947 to February 22, 2019) via OVID; ERIC (February 22, 2019) via Proquest; CINAHL (February 22, 2019) via EBSCO; and SCOPUS (February 22, 2019) via SCOPUS.

We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for the other databases and we included filters used in other systematic reviews for population (childcare services) (Zoritch 2000), physical activity (Dobbins 2013), healthy eating (Jaime 2009), and obesity (Waters 2011). A search filter for intervention type (implementation interventions) was based on previous reviews (Rabin 2010), and a glossary of terms in implementation and dissemination research (Rabin 2008). See Appendix 1 for the detailed search strategy.

Small amendments to the original search strategy were made to improve the sensitivity of the search, which was performed by an experienced librarian (DB). After removal of duplicates, citations were exported and managed in Covidence.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all included studies for citation of other potentially relevant studies. We conducted handsearches of all publications for the past three years in the journal Implementation Science and the Journal of Translational Behavioural Medicine, as they are the leading implementation journals in the field. Furthermore, we conducted searches of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov). We included studies identified in such searches, which have not yet been published, in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table. We also made contact with the authors of included studies, experts in the field of implementation science and key organisations to identify any relevant ongoing or unpublished studies or grey literature publications.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (from a pool of three authors: JJ, CB and MF) independently screened abstracts and titles. Review authors were not blind to the author or journal information. We conducted the screening of studies using a standardised screening tool developed based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), which we piloted before use. We obtained the full texts of manuscripts for all potentially eligible studies for further examination. For all studies, we recorded information regarding the primary reason for exclusion and documented this in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We included the remaining eligible studies in the review. We resolved discrepancies between review authors regarding study eligibility by consensus. In instances where the study eligibility could not be resolved via consensus, a third review author made a decision.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from a pool of five authors: JJ, MF, RW, AG and CB), unblinded to author and journal information, independently extracted information from the included studies. We recorded the information extracted from the included studies in a data extraction form that we developed based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Public Health Group Guide for Developing a Cochrane Protocol (Cochrane Public Health Group 2011). We piloted the data extraction form before the initiation of the review. We resolved data extraction discrepancies between review authors by consensus and, where required, via a third review author.

We extracted the following information:

Study eligibility as well as the study design, date of publication, childcare service type, country, the demographic/socioeconomic characteristics of services and participants, the number of experimental conditions, and information to undertake an assessment of study risk of bias.

Characteristics of the implementation strategy, including the duration, number of contacts, description of implementation strategies, theoretical underpinning of the strategy (if noted in the study), information to allow classification against the EPOC taxonomy, and to enable an assessment of the overall quality of evidence using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as well as data describing consistency of the execution of the intervention with a planned delivery protocol.

Study primary and secondary outcomes, including the data collection method, validity of measures used, effect size and measures of outcome variability.

Source(s) of research funding and potential conflicts of interest.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Overall risk of bias

Within each included study two review authors (MK and FT) assessed risk of bias independently for each review outcome using the 'Risk of Bias' tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We determined an overall risk of bias ('high', 'low' or 'unclear') for individual studies and outcomes. For each included study, we assessed risk of bias as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear' for the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and 'other' potential sources of bias. We included an additional domain 'potential confounding' to assess the risk of bias in nonrandomised trial designs (Higgins 2011). Confounding was defined as the risk that an ‘unmeasured characteristic' shared by those allocated to receive the implementation intervention (or implementation strategy), rather than the intervention itself, was responsible for reported outcomes (Bilandzic 2016). We also included additional domains for cluster‐randomised controlled trials, which assessed 'recruitment to cluster', 'baseline imbalance', 'loss of clusters', 'incorrect analysis' and 'compatibility with individually randomised controlled trials' (Higgins 2011). Where required, a third review author adjudicated discrepancies regarding the risk of bias that could not be resolved via consensus (LW). We documented the risk of bias of the included studies in 'Risk of Bias' tables.

We made an overall 'Risk of bias' assessment for an outcome within a study (across domains). As the nature of the experimental manipulations of studies of implementation strategies is such that blinding of participants and personnel is unlikely to be possible, we classified outcomes within a study as at an overall ‘high risk’ when the study was judged to be at high risk of bias for that outcome on more than one of the following: sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and, in instances where self‐report measures of outcome were employed, blinding of outcome assessment. We assigned a low risk of bias to a study when the study was judged to be at low risk of bias for a study outcome on all key criteria.

We also assessed risk of bias for an outcome across studies. Consistent with other Cochrane reviews of public health interventions (Virgara 2019), we judged an outcome as i) low risk if most information for the outcome was generated from studies at low risk of bias ii) unclear risk of bias if most information was from studies at low or unclear risk of bias; or iii) high risk of bias if the proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias was sufficient to affect the interpretation of results.

Measures of treatment effect

We were able to undertake meta‐analysis for implementation outcomes given there was a sufficient number of studies considered suitably homogenous. For binary outcomes, we calculated the standard estimation of the risk ratio (Odds ratio) and a 95% confidence interval. For continuous data, we calculated a standardised mean difference (SMD), given use of different continuous outcome measures reported in the included studies. We interpreted the magnitude of effect size using the benchmarks suggested by Cohen, considering an SMD of 0.2 a small effect; 0.5 a medium effect; and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988). We have described all other secondary outcomes narratively.

Unit of analysis issues

Clustered studies

We examined clustered studies for unit of analysis errors and recorded these if they occurred in the 'Risk of Bias' tables. No studies included in meta‐analysis of implementation outcomes used clustered designs. These designs, however, were utilised in the assessment of individual level child outcomes such as measures of effect on child diet or physical activity.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of included studies to provide additional information if any outcome data were unclear or missing. All information received was included in the results of the review. We noted any instances of potential selective or incomplete reporting of outcome data in the 'Risk of Bias' tables. We performed meta‐analysis using an intention‐to‐treat principle. Missing data did not preclude inclusion of any studies in meta‐analysis, and as such, the potential impact of missing data on the pooled estimates of intervention effects were not investigated in sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For studies included in meta‐analysis, we explored heterogeneity via forest plots and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2019). We described study participants, intervention, outcomes, and comparators of all included studies in the results and documented such information in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Assessment of reporting biases

The comprehensive search strategy for this review helped to reduce the risk of reporting bias. We also conducted comparisons between published reports and study protocols, and trial registers, where such reports were available. Instances of potential reporting bias were documented in the 'Risk of Bias' tables.

Data synthesis

Two authors (CB, LW) were responsible for entering data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software. Where studies with suitable data were identified, we performed meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model in RevMan 5. Meta‐analysis was undertaken using the generic inverse variance method. We did not pool data from randomised and nonrandomised trial designs. Similarly, we did not attempt to pool data from nonrandomised studies of different study designs. We reported measures of treatment effect from included studies that were adjusted for potential confounding variables over reported estimates that were not adjusted for potential confounding. Where studies used multiple follow‐up periods, we used data from the final (most recent) study follow‐up. We included data from the primary implementation outcome in meta‐analyses. In instances where the authors of included studies did not identify a primary implementation outcome, we used the outcome on which the study sample size and power calculation was based. In its absence, for studies using score‐based measures of implementation, and reporting total and subscale scores, we assumed the total score represented the primary implementation outcome. Otherwise, we attempted to calculate a relative effect size for each implementation outcome measure, rank these based on effect size and used the measure reporting the median effect size to include in any pooled analysis. We calculated the effect size by subtracting the change from baseline of the primary implementation outcome for the control or comparison group from the change from baseline in the experimental or intervention group. If data to enable calculation of the change from baseline were unavailable, we used the differences between groups post‐intervention. For score‐based measures, we calculated a standardised ('d') measure of effect size for each outcome to rank the effect size. Where there were an even number of implementation outcomes, one of the two measures at the median was randomly selected and used for inclusion in meta‐analysis. We reverse scored implementation measures that did not represent an improvement (for example, the proportion of services without a nutrition policy).

We synthesised findings by outcome, and within the study, synthesised effects by comparison. We included a 'Summary of intervention, measures and absolute intervention effect size table', where we reported the employed implementation strategies classified using the EPOC taxonomy (EPOC 2015), the comparison, the primary implementation outcome measures, the effect sizes on these measures (or median effect size and range of effects where multiple measures of the same outcome are reported) for each study (Table 2).

1. Summary of intervention, measures and absolute intervention effect size in included studies.

| Study | Implementation strategies | Comparison group | Primary implementation outcome measures | Effect sizea |

| Alkon 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings and audit and feedback | Usual practice |

Score: nutrition and physical activity policy quality using the CHPHSPC and nutrition and physical activity practices using the EPAO assessed via observation (5 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: Services with a nutrition or physical activity policy (2 measures) % of foods offered to children (10 measures) |

Median (range)c: 1.4 (0 to 4.29) Median (range): 33%% (22% to 44%)c Median (range): 7.7% (133% to ‐2.7% |

| Bell 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, and small incentives or grants | Usual practice |

% of staff or services implementing a practice: percentage of services implementing nutrition policies and practices and menus consistent with nutrition recommendations (10 measures) Quantity of food served (servings/items): mean number of items or servings of healthy/unhealthy foods on service menus (4 measures) |

Median (range): 9.5% (2% to 36%) Median (range): 0.5 serves/items (‐0.4 to 0.8) |

| Benjamin 2007 | Educational materials, educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Usual practice | Score: nutrition, physical activity environments assessed via questionnaire (NAPSACC) completed by service managers (total score) | Mean difference (95% CI)c: 5.10 (‐2.80 to 13.00) |

| Finch 2012 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives | Usual practice |

% of staff or services implementing a practice: percentage of services implementing physical activity policies and practices (11 measures) Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice: time (hours/day) spent on structured physical activities (1 measure) |

Median (range): 2.5% (‐4% to 41%) Mean: 6 minutes |

| Finch 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives | Usual practice |

Frequency of staff or service implementation of a practice: occasions of implementation of fundamental movement skill activities, staff role modelling and verbal prompts and positive comments (4 measures) Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice (per session or day): minutes of fundamental movement skill activities, structured time, television viewing or seated time (4 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: services with seated time > 30 minutes or with an activity policy (2 measures) Mean number of resources or equipment per service: (3 measures) |

Median (range): 2.6 (12.1 to 0.6) Median (range)c: 4.3 minutes (‐12 minutes to 39 minutes) Median (range): 5 (30 to ‐20) Median (range): ‐01 (‐0.6 to ‐0.1) |

| Gosliner 2010 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants with staff wellness programme | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing | % of staff or services implementing a practice: Provision of food items by staff 'more often' assessed via staff‐completed questionnaire (8 measures) | Median (range): 17% (0% to 23%) |

| Hardy 2010 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants | Usual practice |

Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice: Minutes (per week or session) of structured and unstructured play or fundamental movement skills activities (3 measures) Frequency of staff or service implementation of a practice: Frequency (per week or day) of structured or unstructured play, and of fundamental movement skill activities (3 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: conduct of food‐based activities, development of new rules around food and drink bought from home, and the provision of health information to families (3 measures) |

Median (range): 7.7 minutes (6.5 minutes to 10.1 minutes) Median (range): 0.2 (‐0.9 to 1.9) Median (range)c: 11% (‐7% to 31%) |

| Johnston Molloy 2013 | Educational materials, manager and staff educational meetings and audit and feedback | Educational materials, manager educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Score: On the Health Promotion Evaluation Activity Scored Evaluation form assessed via observation (total score) | Difference in median score: ‐2b |

| Ward 2008 | Educational materials, educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Usual practice | Score: nutrition and physical activity practices using the EPAO assessed via observation (total score) | Mean difference (95% CI)c: 1.01 (0.18 to 1.84) |

| Williams 2002 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants | Usual practice | Quantity of food served (servings/grams): Primary outcome – grams of saturated fat assessed via menu audit (one measure) | Median (range): 17% (0% to 23%) |

| O’Neill 2017 | Educational meetings, release of practice guidelines | Usual practice |

% of staff or services implementing a practice: Percent of services implementing a practice consistent with standards for the setting (13 measures) Score: physical activity environment using the EPAO assessed via researcher observation (1 measure‐ total score) |

Median (range) OR = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.87 to 1.29 (OR 1.35 to 0.89) Mean difference: 0.9 (P = 0.06) |

| Jones 2015 | Audit with feedback, educational material, educational meetings, opinion leaders, local consensus approach, educational outreach or academic detailing. Other: employment of communication strategies and implementation support staff |

Usual practice |

Score: mean number of policies and practices implemented (1 measure) % of staff or services implementing a practice: proportion of services implementing all seven healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices (1 measure) |

Mean Difference: 0.4 (P = 0.05) Main analysis OR: 1.33 (0.64, 2.76) |

| Seward 2017 | Audit with feedback, educational materials, educational meetings, opinion leaders, educational outreach or academic detailing | Usual practice |

Score: Mean number of food groups compliant with guidelines % of staff or services implementing a practice: Proportion of services fully compliant with nutrition guidelines for all food groups (7 measures) |

Mean difference 1.57 (0.82, 2.33) OR Median (range): OR 6.26; 95% CI 1.26 to 43.40 (OR 1 to 16.54) |

| Yoong 2016 | Educational materials | Usual practice | Quantity of food served: number of fruit and vegetable serves on the service menu assessed via questionnaire (2 measures) | Mean difference median (range): 0.25 (0.0 to 0.50) |

| Esquivel 2016 | Educational materials, educational meetings. Other: monthly employee wellness activities | Waiting‐list control (delayed intervention) | Score: nutrition and physical activity environments using the EPAO assessed via researcher observation (total score) | Mean difference: 1.1 |

| Mazzucca 2017 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach or academic detailing, reminders, tailored interventions | Usual practice | Score: physical activity environment assessed using modified EPAO assessed via service self‐report (7 measures) | Median/Mean differences (range): 0.4 (‐0.7 to 0.9) |

| Morshed 2016 | Educational materials, educational meeting | Usual practice | Quantity of food served: number of fruit, vegetable, and whole grain servings, grams of discretionary fat, teaspoons of added sugar, and grams of fat from milk provided assessed via researcher observation (6 measures) |

Relative change estimate: OR (95% CI): 1.00 (0.81 to 1.24) (OR 1.09 to 0.82) |

| Sharma 2018 | Educational meetings, educational outreach or academic detailing, reminders | Usual practice | Score: Implementation index assessed via teacher‐completed survey (1 measure) | Mean difference: 15.17 |

| Stookey 2017 | Audit with feedback, educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach or academic detailing, incentives, tailored interventions | Waiting‐list control (delayed intervention). | % of staff or services implementing a practice: children’s exposure to three nutrition and physical activity practices: use of physical activity curriculum, staff usually join in physically active play; pitchers of drinking water visible in the classroom (1 measure) | OR (95% CI): 6.5; (1.1 to 40.6) |

| Ward 2017 | Audit with feedback, educational materials, educational meetings | Waiting‐list control (delayed intervention) | Score: nutrition environment assessed using the EPAO assessed via service self‐report (total score) | Mean difference: 0.73 |

| Finch 2019 | Educational materials, audit with feedback, continuous quality improvement, educational outreach or academic detailing, opinion leaders, tailored interventions | Usual practice |

Score: mean number of policies and practices implemented (1 measure) % of staff or services implementing a practice: Proportion of services implementing all six policies/practices (1 measure) |

Mean difference: 0.1; 95% CI −0.4 to 0.6 OR (95%CI): 0.51 (0.16 to 1.58) |

aEffect size calculated first using the primary outcome (where a single primary outcome was reported); otherwise using a total score (when total and subscale scores were provided); otherwise using the median effect size across measures (where more than one outcome measure was reported and not specified as primary).

bMean not reported. Represents the difference in median score between manager‐ and staff‐trained versus manager only‐trained group.

cAdditional data obtained from study authors where unclear or missing

CHPHSPC: Californian Childcare Health Programme Health and Safety Checklist DOCC: Diet Observation in Child Care EPAO: Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation NAPSACC: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self‐Assessment for Child Care

We included a 'Summary of findings' table to present the key findings of the review (Table 1). We generated the table based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the EPOC Group and included i) a list of all primary and secondary outcomes in the review, ii) a description of intervention effect, iii) the number of participants and studies addressing each outcome, and iv) a grade for the overall quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. In particular, the table provides key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of the effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes. 'Summary of findings' tables were produced using data from randomised controlled trials only as the included nonrandomised trials did not provide greater certainty evidence, nor did they include outcomes that were not also reported in included randomised trials. Similarly, 'Summary of findings' tables were produced for studies reporting the effects of interventions versus usual care or a minimal support comparison group, as this was considered of primary interest to end‐users.

Two review authors (CB, RH) rated the overall quality of evidence for each outcome using the GRADE system (Guyatt 2010), with any disagreements resolved via consensus or, where required, by a third review author (LW). The GRADE system defines the quality of the body of evidence for each review outcome regarding the extent to which one can be confident in the review findings. The GRADE system required an assessment of methodological quality, directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias. We used the GRADE quality ratings (from 'very low' to 'high') to describe the quality of the body of evidence for each review outcome and we included these in 'Table 1'. We assessed the quality of evidence separately for randomised and non‐randomised trials. Where there were multiple measures of the same outcome, we assessed the quality of evidence for each measure separately. In such instances, we selected the measure of the outcome with the greatest collective (across study) sample size to present in the 'Summary of findings' tables to represent the GRADE assessment of that outcome. However, we also noted the GRADE assessments of other measures of the outcome as comments in the 'Summary of findings' table for completeness.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the published protocol (Wolfenden 2015b), subgroup analyses and box plots were planned to explore heterogeneity if the I2 value was greater than 75%. As measures of heterogeneity did not reach this threshold, subgroup analyses were not undertaken. Nonetheless, clinical and methodological heterogeneity of included studies was described narratively. To describe the impact of implementation strategies delivered 'at scale' (defined as involving 50 or more childcare services), we performed subgroup analyses narratively for the primary implementation outcomes. Specifically, this was undertaken for included studies that sought to improve implementation of policies, practices or programmes across 50 or more services.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was planned by removing studies with a high risk of bias and by removing outliers contributing to statistical heterogeneity following visual inspection of the forest plots (i.e. where the confidence intervals of a study did not overlap with other included studies). However, none of the studies included in meta‐analysis were judged to be at high risk of bias, nor were outliers identified following inspection of forest plots.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

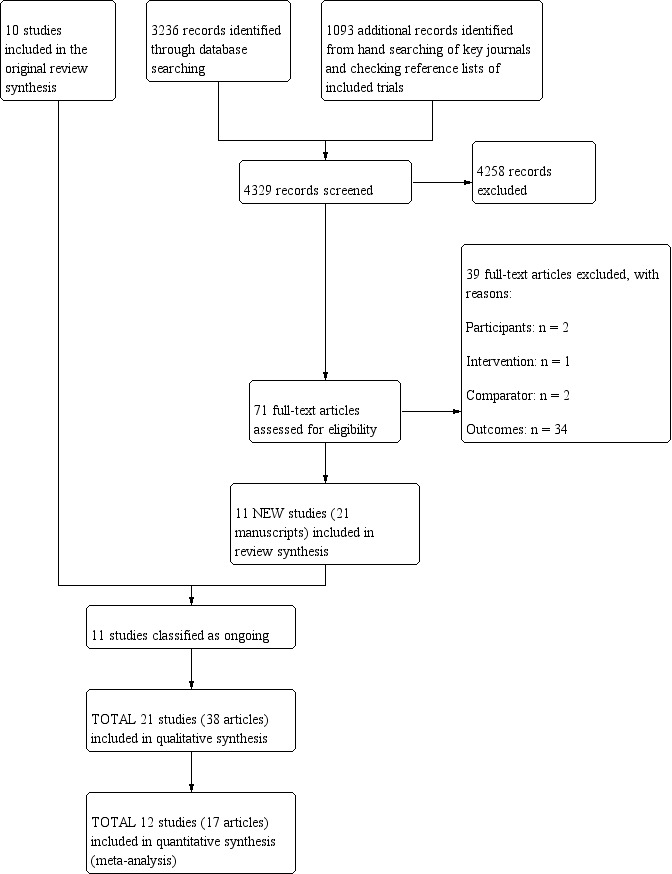

Results of the search

The electronic search for this update, conducted on 22 February 2019, yielded 3236 citations (Figure 1). We identified an additional 1093 records from handsearching key journals and checking reference lists of included studies. We identified no additional records through our contact with the authors of included studies, experts in the field of implementation science and key organisations. Following screening of titles and abstracts, we obtained the full texts of 71 manuscripts for further review, of which we included as part of this update 21 manuscripts describing 11 individual studies. We contacted the authors of four included studies to provide additional information where any outcome data were unclear or missing. All information received by authors was included in the results of the review. As 10 studies were included in the original version of this review (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008; Williams 2002), this update brought the total number of included studies to 21 studies. Additionally, 11 studies were identified as ongoing studies through searches of clinical trial registration databases that have not yet been published.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Types of studies

The included studies were predominantly conducted in the USA (n = 12) (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Gosliner 2010; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; O’Neill 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008; Ward 2017; Williams 2002) and Australia (n = 8) (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Hardy 2010;Jones 2015;Seward 2017;Yoong 2016), but there was also one study from Ireland (Johnston Molloy 2013). Studies were conducted between 1995 and 2018, although two studies did not report the years of data collection (Benjamin 2007; Gosliner 2010). There was evidence of some heterogeneity in the participants, interventions, outcomes and study design characteristics of included studies. All but one included study (Mazzucca 2017) reported receiving funding support to undertake the study. Funding support for such studies were from government or charitable foundations. No industry funding was reported.

Participants

Of the 21 included studies, 15 recruited childcare services located in disadvantaged areas or specifically serving disadvantaged, low‐income or minority children (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; Morshed 2016; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Ward 2017; Williams 2002). The socioeconomic characteristics of the service locality or children attending the childcare services were not described in the remaining six studies. The number of childcare services participating in the studies included in the review varied. The largest study recruited 583 childcare services (preschools) (Bell 2014), and a further eight studies sought to improve implementation of policies, practices or programmes in 50 or more services (Finch 2012; Finch 2019; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Ward 2008; Yoong 2016). Six studies recruited between nine and 20 services (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Morshed 2016; Williams 2002). Twelve of the 21 included studies were conducted in high‐income countries by two research groups in the USA and Australia (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Seward 2017; Ward 2008;Ward 2017;Yoong 2016).

Interventions

Six studies targeted the implementation of healthy eating policies or practices only (Bell 2014; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017; Ward 2017; Williams 2002;Yoong 2016), three targeted the implementation of physical activity policies and practices only (Finch 2012; Finch 2014;Mazzucca 2017), and 12 targeted both healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; O’Neill 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008).

All studies used multiple implementation strategies, with the exception of one study (Yoong 2016). The strategies tested across studies examined only a small number of those described in the EPOC taxonomy that could be applied to improve implementation in the setting. The definitions of each of the EPOC subcategories used to classify implementation strategies employed by studies included in the review are provided in Table 3. Using the EPOC taxonomy descriptors for tested implementation strategies, 17 of the 21 studies tested educational meetings and educational materials (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008; Ward 2017; Williams 2002). The remaining studies testing educational meetings and educational materials in combination with other strategies such as audit and feedback (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013;Jones 2015;Seward 2017;Stookey 2017;Ward 2017), educational outreach visits or academic detailing (Benjamin 2007; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017Ward 2008), small incentives (Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Stookey 2017; Williams 2002) or opinion leaders (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2019; Seward 2017).

2. Definition of EPOC subcategories utilised in the review.

| EPOC subcategory | Definition |

| Educational materials | Distribution to individuals, or groups, of educational materials to support clinical care, i.e. any intervention in which knowledge is distributed. For example, this may be facilitated by the internet, learning critical appraisal skills; skills for electronic retrieval of information, diagnostic formulation; question formulation. |

| Educational meetings | Courses, workshops, conferences or other educational meetings |

| Educational outreach visits or academic detailing | Personal visits by a trained person to health workers in their own settings, to provide information with the aim of changing practice |

| Small incentives or grants | Transfer of money or material goods to healthcare providers conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target, for example incentives for lay health workers |

| Audit and feedback | A summary of health workers’ performance over a specified period of time, given to them in a written, electronic or verbal format; the summary may include recommendations for clinical action. |

| Opinion leaders | The identification and use of identifiable local opinion leaders to promote good clinical practice |

| Tailored interventions | Interventions to change practice that are selected based on an assessment of barriers to change, for example, through interviews or surveys. |

| Reminders | Manual or computerised interventions that prompt health workers to perform an action during a consultation with a patient, for example, computer decision support systems |

| Local opinion leaders | The identification and use of identifiable local opinion leaders to promote good clinical practice |

| Local consensus processes | Formal or informal local consensus processes, for example, agreeing a clinical protocol to manage a patient group, adapting a guideline for a local health system or promoting the implementation of guidelines |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines | Clinical guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist healthcare providers and patients to decide on appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances (USA IOM). |

IOM: Institute of Medicine

Twelve studies reported that strategies to support implementation were theoretically based (Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Ward 2008;Yoong 2016). The theories adopted in these studies included components of social cognitive theory (Benjamin 2007; Mazzucca 2017; Sharma 2018; Ward 2008), practice change and capacity building theoretical frameworks (Bell 2014), theory of planned behaviour (Yoong 2016), consolidated framework for implementation research (Finch 2019; Jones 2015), theoretical domains framework (Seward 2017) and social‐ecological models of health behaviour change (Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014;Morshed 2016).

Intervention duration for the included studies ranged from six to eight weeks (Yoong 2016) to three years (Williams 2002). The duration of the majority of interventions were six to 12 months (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Jones 2015; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008) and four studies had a duration of longer than 12 months (Bell 2014; Morshed 2016; Sharma 2018; Williams 2002).

Outcomes

A variety of implementation outcome measures were used to assess the implementation strategies across included studies. Nineteen studies included continuous measures of implementation outcomes including policy or environment scores (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2019; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Ward 2008; Ward 2017), minutes of policy or programme implementation (Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), frequency of policy or programme implementation (Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), or quantity of food or beverages or macronutrients provided to children (Bell 2014; Morshed 2016; Williams 2002;Yoong 2016).

Eleven studies reported a dichotomous measure of implementation, each of which reported the percentage of staff or childcare services that implemented a policy, practice or programme (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Jones 2015; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017).

Implementation was primarily assessed using telephone interviews or surveys/questionnaires completed by childcare service staff (Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Ward 2017; Yoong 2016), audits of service documents conducted by researchers (Bell 2014; Seward 2017; Williams 2002) or by direct observation (Alkon 2014; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013; Morshed 2016; O’Neill 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008).

The validity of six of the ten studies utilising survey/questionnaire based instruments to assess implementation was not reported (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010;Sharma 2018). Outcome assessments were conducted at various time points following intervention completion. Four studies conducted outcome assessments immediately following intervention completion (Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017), whilst other studies included follow‐up assessments of five months (Hardy 2010) to four years following intervention completion (Johnston Molloy 2013).

Nine studies included child behavioural or weight‐related outcomes (Alkon 2014; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Williams 2002). Of the nine studies, four measured child diet (Jones 2015; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Williams 2002), five measured child physical activity (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Sharma 2018) and five measured child weight status (Alkon 2014; Esquivel 2016; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Williams 2002).

Three of the 21 included studies reported on potential adverse effect outcomes, which included negative feedback received by the childcare service (Seward 2017) and occurrence of child injury (Finch 2014; Jones 2015). Eight studies included a measure of acceptability (Benjamin 2007, Finch 2012, Finch 2014, Finch 2019, Hardy 2010, Jones 2015, Mazzucca 2017, Ward 2017), and 12 studies measured penetration of the intervention and implementation strategies (Alkon 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010; Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008; Yoong 2016). None of the 21 studies reported intervention costs or cost‐effectiveness analyses.

Study design characteristics

Sixteen of the included studies were randomised trials (or cluster‐randomised trials) (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008;Ward 2017;Yoong 2016), and five were nonrandomised trials with a parallel control group (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; O’Neill 2017; Sharma 2018; Williams 2002).

Nineteen studies compared an implementation strategy to usual practice or minimal support control (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Finch 2019; Hardy 2010; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; O’Neill 2017; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008; Ward 2017; Williams 2002; Yoong 2016). Two studies directly compared two different implementation strategies (Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013).

Excluded studies

Thirty‐nine studies were excluded following review of 71 full texts (Figure 1) for the following reasons: participants n = 2; intervention n = 1; comparator n = 2; outcomes n = 34. We excluded a study based on 'inappropriate outcomes' if it: did not measure implementation outcomes, did not measure implementation outcomes for both intervention and control groups, or did not measure between‐group differences in implementation outcomes.

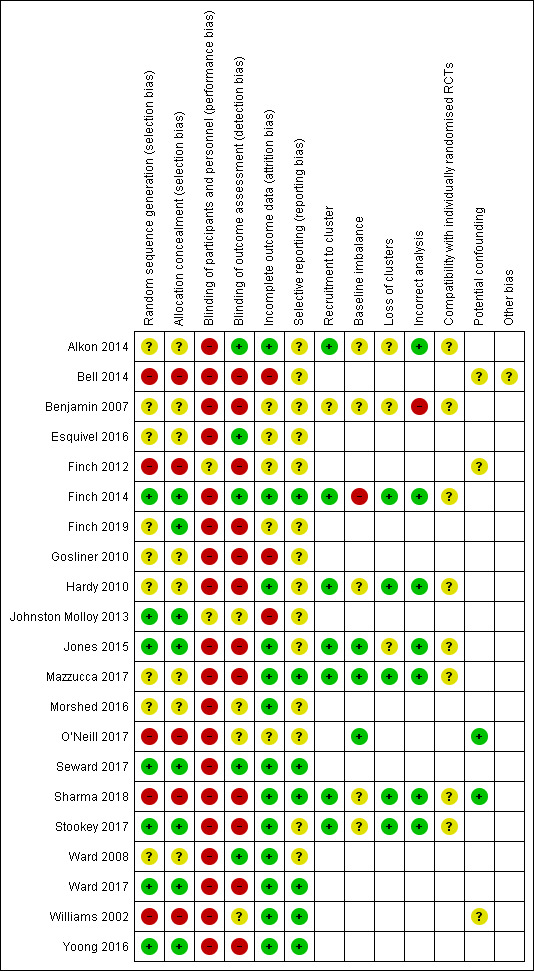

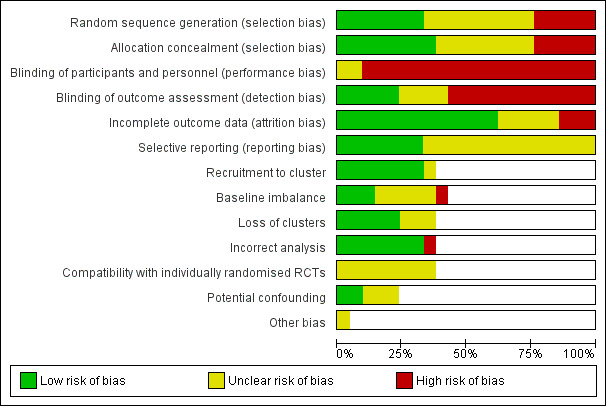

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies. For the primary implementation outcomes, 'Risk of bias' assessment for each criterion for each study is presented in Figure 2 and summarised within the Characteristics of included studies tables. Figure 3 illustrates the overall risk of bias of each study for primary implementation outcomes (across all domains). 'Risk of bias' assessments are described in detail below. Risk of bias assessments for secondary outcomes of each study are presented in Appendix 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias graph': review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Risk of selection bias differed across studies. Seven studies were low risk as computerised random number functions or tables were used to generate random sequences and allocation was undertaken automatically in a single batch, preventing allocation from being pre‐empted (Finch 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013;Jones 2015;Seward 2017;Stookey 2017;Ward 2017;Yoong 2016). While the study conducted by Finch and colleagues (Finch 2019) also undertook these procedures, participating services were removed following randomisation and it is unclear whether this affected the randomisation. For the five studies with non‐randomised designs, the risk of selection bias was high (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; O’Neill 2017; Sharma 2018; Williams 2002). For the remaining eight studies, such bias was unclear as these studies did not report on methods for sequence generation or allocation.

Blinding

For almost all studies (n = 19), the risk of performance bias was high due to participants and research personnel not being blind to group allocation. For the remaining two studies, the risk of performance bias was unclear as in both studies the control group also received some form of intervention (Finch 2012; Johnston Molloy 2013). Detection bias differed across studies based on whether outcome measures were objective (low risk) or self‐reported (high risk), and whether research personnel were blind to group allocation when conducting outcome assessment (low risk). For five studies, the risk of detection bias was low (Alkon 2014; Esquivel 2016; Finch 2014; Seward 2017; Ward 2008). For the remainder of the studies, the risk of detection bias was either high (n = 12) or unclear (n = 4) due to insufficient information on whether data collection staff were blind to group allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

For just over half the studies (n = 13), the risk of attrition bias was low as either all or most participating services were followed up and/or sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of missing data (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010; Jones 2015; Mazzucca 2017; Morshed 2016; Seward 2017; Sharma 2018; Stookey 2017; Ward 2008; Ward 2017; Williams 2002; Yoong 2016). For two studies, the risk of such bias was high due to a large difference in the proportion of participating services lost to follow‐up between groups (Bell 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013). Risk of attrition bias was also high for the study conducted by Gosliner and colleagues, as participants who did not complete the intervention were excluded from the analysis (Gosliner 2010). For the remaining studies, the risk of attrition bias was unclear as insufficient information was provided regarding the treatment of missing data.

Selective reporting