Abstract

In this study, we attempted to upgrade GT−MCP/−MCP pig genetically to express MCP at a higher level and additionally thrombomodulin (TBM), which have respective roles as a complement regulatory protein and a coagulation inhibitor. We constructed a dicistronic cassette consisting of codon-optimized MCP (mMCP) and TBM (m-pI2), designed for ubiquitous expression of MCP and endothelium specific expression of TBM. The cassette was confirmed to allow extremely increased MCP expression compared with non-modified MCP, and an endothelial-specific TBM expression. We thus transfected m-pI2 into ear-skin fibroblasts isolated from a GT−MCP/−MCP pig. By twice selection using magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS), and single-cell culture, we were able to obtain clones over 90% expressing MCP. The cells of a clone were provided as a donor for nuclear transfer resulting in the generation of a GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig, which was confirmed to be carrying cells expressing MCP and functioning as an inhibitor against the cytotoxic effect of normal monkey serum, comparable with donor cells. Collectively, these results demonstrated an effective approach for upgrading transgenic pig, and we assumed that upgraded pig would increase graft survival.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-2091-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pig; Membrane cofactor protein; Thrombomodulin; Codon optimization

Introduction

Membrane cofactor protein (MCP) is a membrane protein expressed ubiquitously and plays a role in the protection of host cells by inactivation of activated C3b and C4b, which are involved in the alternative complement pathway (Iwata et al. 1995). The immunogenic protective roles of MCP have been highlighted in xenotransplantation research, which essentially requires the generation of a transgenic pig to overcome immunological rejection. MCP transgenic pigs using full genomic and minigene sequences of approximate 43 kb long and 8 kb long, respectively, have been generated (Schneider-Schaulies et al. 2000; Adams et al. 2001; Loveland et al. 2004). Eventually, cardiac transplantation of MCP transgenic pig into primate showed maximally 179-day survival (McGregor et al. 2005). Mohiuddin et al. reported that a primate grafted heart of MCP pig under the background of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase homozygous knockout pig (GTKO) survived for 236 days (Mohiuddin et al. 2012).

Thrombomodulin (TBM) is a membrane protein existing on the surface of vascular endothelial cells, and it is known to play roles in the regulation of the blood coagulation cascade(Crikis et al. 2010), protection of the vessel wall from injury,(Yang et al. 2016) and an exhibition of the anti-inflammatory response (Conway 2012; Anastasiou et al. 2012). The biochemical and molecular functions of TBM could be expected to make a contribution to overcoming and/or attenuating xenotransplantation failure by thrombotic microangiopathy, which is observed in xeno-graft of GTKO pig along with ischemic injury (Kuwaki et al. 2005). Iwase et al. (2015) reported that pig-to-baboon cardiac transplantation using TBM transgenic pig revealed suppressed thrombocytopenia, thrombotic microangiopathy, and consumptive coagulopathy. More recently, Mohiuddin et al. (2016) achieved a big advance in preclinical trials of 945-day survival by transplantation of GTKO/MCP/TBM pig heart, which possibly suggests that GTKO and MCP/TBM expressing pig is a basic platform for applying xenotransplantation research.

MCP seems to be a distinctive gene with the prediction of expression regulation being obscure in vitro and in vivo based on reports of the difficulty in the expression of MCP with MCP cDNA in vitro (Hurh et al. 2013; Milland et al. 1996) and the high levels of expression of MCP with genomic DNA. Given that MCP is one of the most crucially relevant factors for xenotransplantation, the low translational efficiency of MCP when cDNA was used has been stated as a limitation for developing new and/or upgrading genetically transgenic pigs with a simple construct approach.

In previous studies, we reported that MCP cDNA expression cassette-targeted to GT locus led to efficient expression of MCP in heterozygous GT−MCP/+ porcine fibroblasts and homozygous GT−MCP/−MCP pig (Ko et al. 2013; Hwang et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2017). The pigs were applied for cardiac xenotransplantation to cynomolgus monkeys, and the results showed a mean survival of 38 days (Lee et al. 2018). We assumed that upgrading of the pig to increase MCP expression level and to additionally express TBM would be an alternative way to improve the number of survival days of recipient monkey. To this end, we constructed two types of cassettes for MCP and TBM concurrent expression using wild-type MCP and TBM cDNA. However, we did not observe the expression of MCP from abundantly expressed mRNA transcripts, while there was an efficient expression of TBM. Thus, we attempted optimization of codon usages of MCP (mMCP), and we were able to observe the dramatic upregulation of MCP expression. Subsequently, we transfected and selected the cells with high expression of MCP, and thereby generated a single clone genotyped as GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM. Finally, we were able to generate successfully a cloned pig, GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig, carrying cells with high and functional expression of MCP as a complement regulatory protein and possessing the potential for specific expression of TBM in the endothelium.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

The protocol and standard operating procedures for the treatment of the pigs used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Animal Science, Rural Development Administration of Korea (Approval Number: NIAS2018-279). All the methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the committee.

Primary cell culture

Isolation and culture of porcine ear fibroblasts (pEF) were described in detail in a previous study (Ko et al. 2013). Porcine aortic endothelial cells (pAEC) were obtained from aorta vessels of a 1-month-old male pig. One end of the vessel was tied using surgical thread, filled with 0.1% collagenase type I and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The enzyme solution was collected and plated on the culture vessel. The harvested cells were cultured in endothelial cell growth medium (Lonza, Koln, Germany).

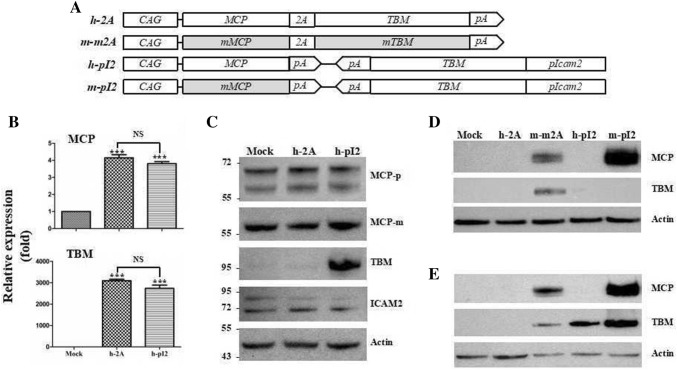

Construction of human MCP and TBM expressing cassettes and modification of sequences

The wild-type MCP cDNA (MCP) clone synthesis was described in a previous study [16]. The TBM cDNA was synthesized from NM_000361.2 as a template. The fragments containing wild-type MCP, porcine teschovirus-1 2A (2A), and TBM sequences including bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal sequences were connected with the CAG promoter (h-2A). TBM expression cassette under control of 1 kb Icam2 promoter was connected with MCP expression cassette reversely (h-pI2). Sequence modifications to optimize codons of MCP and TBM were performed with the same method as (Raab et al. 2010). The modified MCP (mMCP) and TBM (mTBM) were synthesized and substituted for MCP and TBM, respectively. The expression cassettes containing modified sequences used in this study were referred to as m-m2A and m-pI2 (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Codon optimization of MCP cDNA leads to increase of MCP expression at protein level, but not of TBM. a Schematic diagrams of expression cassettes for MCP and TBM. MCP and TBM indicate wild-type cDNA in h-2A, h-pI2, and m-pI2. The mMCP and mTBM indicate sequence-modified cDNA optimized codon usages in m-m2A and m-pI2. CAG, CMV enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter; 2A, porcine teschovirus-1 2A signal sequence; pA, bGH poly A signal sequences; pIcam2, porcine Icam2 promoter. Quantitative real-time PCR (b) and western blot (c) analyses of h-2A and h-pI2 transfected HeLa cells. (***P < 0.001). NS indicates no statistically significant difference. MCP-p indicates polyclonal-MCP antibody and MCP-m indicates monoclonal-MCP antibody. Western blot analysis of h-2A, m-m2A, h-pI2, and m-pI2 transfected pEF (d) and pAEC (e). Relevant full-length western blot images are shown in the supplementary information

Transfection

Liposome-mediated transfection was performed for the HeLa cell lines using lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The pEF and pAEC were transfected using Amaxa basic nucleofector kit for primary mammalian fibroblasts (#VPI-1002; Lonza) and endothelial cells (#VPI-1001; Lonza), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Single-cell selection and culture

To acquire single-cell culture, MACS cell separation method was used. Transfected cells were washed twice in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; Invitrogen) and were trypsinized. Cells were washed in 1 × PBS and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-human MCP antibody (BioLegend, CA, USA). A 10 μL of anti-FITC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were suspended into a 90 μL of staining buffer (1 × PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin) containing antibody labeled cells and incubated in dark conditions at 4 °C for 15 min. The cells were sorted twice using auto MACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi Biotec) (Miltenyi et al. 1990). Finally, the sorted MCP-positive cells were diluted with cell culture medium to the single-cell scale and cultured in 96-well plate.

Production of cloned pig

To produce cloned pig Oocyte maturation, nuclear transfer, production of reconstructed embryos, and transfer of embryos to surrogate mother were performed as described in a previous study (Kwon et al. 2017). Briefly, in vitro matured cumulus oocyte complexes (COC) were enucleated by aspirating the first polar body and metaphase II chromosomes and a small amount of surrounding cytoplasm in manipulation medium supplemented with 5 mg/ml cytochalasin B. Freshly thawed donor cells were treated with roscovitine and placed into perivitelline space. The karyoplast–cytoplast complexes were placed into 0.2-mm diameter wire electrodes (1 mm apart) of a fusion chamber covered with 0.3 M mannitol solution containing 0.1 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM CaCl2, and 0.5 mM Hepes. For embryo reconstruction, two DC pulses (1-s interval) of 1.5 kV/cm were applied for 30 μs using an Electro-Cell fusion (Fujihira Industry Co., LTD, Japan). Reconstruction of embryos was confirmed using a stereoscope and transferred into both oviducts of the surrogate on the same day. Pregnancy was diagnosed on day 28 after embryo transfer and then was checked regularly every week by ultrasound examination. GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM cloned piglets were delivered by natural parturition.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR analysis

Total RNAs were extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript IV first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by Power SYBR green PCR Master Mix (ABI, CA, USA) and ABI StepOne Real-Time PCR system (ABI). Primers used are presented in supplementary information 1.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell proteins were extracted using mammalian protein extract reagent (Invitrogen). The amount of protein was quantified using Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) according to manufactures guidelines, then 5 μg of protein was loaded into each lane of 4–12% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen) without denaturing the sample and blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Invitrogen). Mouse monoclonal anti-MCP antibody (BioLegend), rabbit polyclonal anti-MCP antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse monoclonal anti-TBM antibody (Abcam), and goat polyclonal anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used. As secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) and donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz) were used. The blot was stained using Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Flow cytometry analysis

The suspended single cells were washed with 1 × PBS and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-human MCP antibody (BioLegend) and PE-conjugated anti-human TBM antibody (BD, Germany) in staining buffer (1 × PBS in 0.5% bovine serum albumin). The cells were analyzed by Attune NxT (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). FITC-conjugated Mouse IgG1, κ antibody was used for isotype control.

PCR analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the cells using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen). An amount of 50 ng of DNA and Prime Taq Premix (Genet Bio, Korea) were used for PCR. Primers used and PCR conditions for detection of m-m2A and m-pI2 integration into pEFs and cloned pig are presented in supplementary information 2.

Monkey serum-dependent cell cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates. Approximately 24 h later, the medium was exchanged with a medium containing 15% of complement preserved monkey serum (Xenia Inc., Seong-nam, Korea) and cells were incubated for 4 h. Cell proliferation assay was performed using Premix WST-1 kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The formula for calculating the cytotoxicity (%) was followed as described in Gao et al. (2017).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.03. Group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Optimization of MCP codon usage to enhance translation efficiency

We constructed MCP and TBM simultaneous expression cassettes with two different strategies, adopting a bicistronic 2A system under the control of CAG promoter (h-2A) and a dicistronic system allowing independent co-expression of MCP and TBM under the control of CAG promoter and endothelial-specific porcine intercellular adhesion molecule 2 (Icam2) promoter (h-pI2), respectively (Fig. 1a). Two cassettes, h-2A and h-pI2, were transfected into HeLa cells. The mRNA expressions of MCP and TBM were significantly upregulated by transfection, while there were no significant differences in the levels of either MCP or TBM between h-2A and h-pI2 (Fig. 1b). Surprisingly, we were not able to find overexpression of MCP in either h-2A or h-pI2 transfected cells despite using polyclonal and monoclonal MCP-antibody, both of which are able to detect endogenous MCP expression (Fig. 1c). TBM overexpression was only detected in h-pI2 cells and not in h-2A cells (Fig. 1c), suggesting that weak expression of TBM in h-2A cells at only the endogenous level is because of inaccurate regulation of 1st cistronic MCP expression rather than inaccurate processing of TBM cDNA synthesis. Taken together, these results suggest that MCP in the cells was transcribed at the fundamental level, but not translated sufficiently from its mRNA, and TBM is a gene with the potential to express itself at the intrinsic level by transcriptional and translational regulation.

As an alternative approach to achieve overexpression of MCP and TBM in cells, we performed codon optimization of MCP (mMCP) and TBM (mTBM) sequences as described in materials and methods. Subsequently, we substituted mMCP and mTBM for MCP and TBM in h-2A, and mMCP for MCP in h-pI2, which resulted in the construction of two more cassettes, m-m2A, and m-pI2 (Fig. 1a). The consequences of the sequence modifications were an increase of GC content to 63% of mMCP from 43% of MCP, which resulted in a 27% change of all sequences (supplementary information 3), and a decrease of GC content from 68 to 66% with a change of 17% of all TBM sequences (data not shown). Four expression cassettes were individually transfected to both porcine ear skin fibroblasts (pEF) and porcine aortic endothelial cells (pAEC) and MCP expression was detected using MCP monoclonal antibody. Western blot analysis showed overexpression of MCP in m-m2A and m-pI2 in pEF and pAEC cells and was undetectable in h-2A and h-pI2 transfected cells (Fig. 1d, e). Interestingly, the expression level of MCP was higher in the cells transfected with m-pI2 than the cells transfected with m-m2A. Probably, the dicistronic system is more efficient than a bicistronic 2A system to express the mMCP. We found upregulation of TBMs in m-m2A pEF and pAEC cells (Fig. 1d, e), indicating that upregulated MCP from mMCP led to a sequential translation of 2A mediated 2nd cistron mTBM. Collectively, these results suggested that MCP contains repressive sequences to disturb translational control at steady state in cells; thus, codon optimization of MCP could enhance its expression at the protein level.

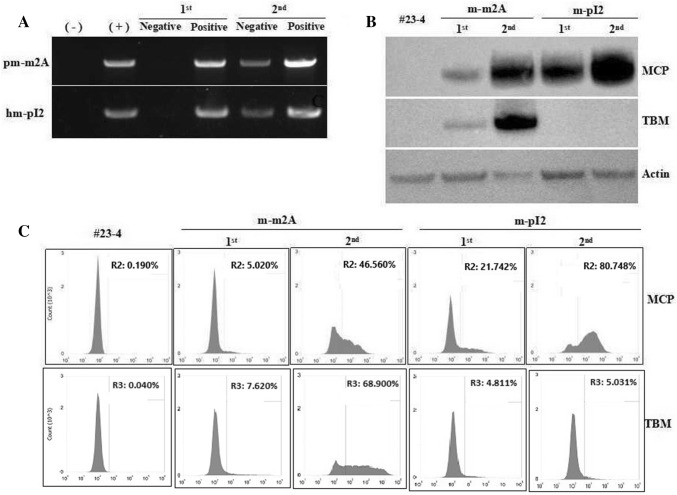

Upgrade of GTMCP/−MCP transgenic pig cells

Next, we isolated pEF from GT−MCP/−MCP pigs (#23–4), cultured the cells and transfected with m-m2A and m-pI2 constructs. We performed two rounds of MACS-based selection to isolate cells expressing MCP. The first selection allowed the elimination of 97.58% of m-m2A and 98.23% of m-pI2 cells as MCP negative cells (Fig. 2a, Table 1). We cultured the MCP positive cells further, to expand the cell numbers. The second MACS-based selection led to an increased population of MCP positive cells accounting for 34.92% of m-m2A cells and 52.27% of m-pI2 cells (Fig. 2a, Table 1). These selection procedures enabled us to obtain higher MCP expressing cell populations, which was clearly demonstrated by western blot (Fig. 2b) and flow cytometry analyses (Fig. 2c). We also detect that TBM expression was increased as much as that of MCP in m-m2A cells (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Cell sorting using MACS sorter allows specific selection of MCP and TBM expressing cells. The transfected pEFs of #23–4 GT-MCP−MCP pig with m-m2A and pm-pI2 were selected twice, indicated as 1st and 2nd. a Genotype analysis of the selected pEFs using forward primers to recognize modified MCP, and reverse primers to recognize modified TBM and wild-type TBM. Western blot (b) and flow cytometry (c) analyses for MCP and TBM expression. Relevant full-length western blot images are shown in the supplementary information

Table 1.

Summary for selection of MCP expressing cells

| Cassette | Sored | Cell numbers (cells/ml) | Viability (%) | % of total cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Live | Dead | |||||

| m-m2A | 1st | Negative | 3.1 × 107 | 2.8 × 107 | 2.9 × 106 | 90.95 | 97.58 |

| Positive | 7.7 × 105 | 4.4 × 105 | 3.2 × 105 | 58.15 | 2.42 | ||

| 2nd | Negative | 4.1 × 105 | 3.3 × 105 | 7.7 × 104 | 81.35 | 65.08 | |

| Positive | 2.2 × 105 | 1.7 × 105 | 4.7 × 104 | 78.60 | 34.92 | ||

| m-pI2 | 1st | Negative | 3.0 × 107 | 2.6 × 107 | 4.3 × 106 | 85.70 | 98.23 |

| Positive | 5.4 × 105 | 2.7 × 105 | 2.7 × 105 | 50.60 | 1.77 | ||

| 2nd | Negative | 2.1 × 105 | 1.8 × 105 | 3.5 × 104 | 83.30 | 47.73 | |

| Positive | 2.3 × 105 | 1.8 × 105 | 5.6 × 104 | 76.10 | 52.27 | ||

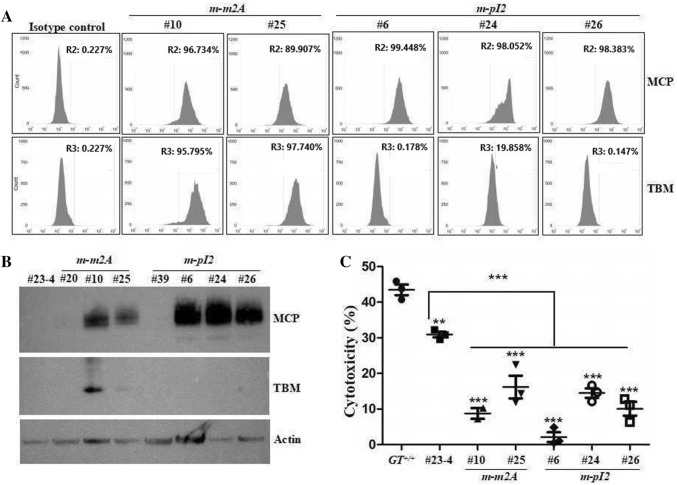

To further separate the cells based on the expression levels of MCP, we diluted the cells to a single cell culture scale and seeded in 96 well plates. We were able to obtain 77 clones and 92 clones from m-m2A cells and m-pI2 cells, respectively (Table 2). We classified the clones into populations over 90%, between 90 and 50%, and below 50% of MCP expression by flow cytometry analysis; and two clones of m-m2A and eight clones of m-pI2 cells were identified as clones expressing MCP over 90% (Table 2). Selected clones expressing MCP and TBM over 90% and under 50% (#20 and #39) are shown in Fig. 3a, b.

Table 2.

Isolation of single clones depending on MCP expression level

| DNA | No. of clones isolated | No. of clones analyzed | No. of Clones < 50% | No. of clones ≥ 50% and < 90% | No. of clones ≥ 90% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m-m2A | 77 | 13 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

| m-pI2 | 92 | 18 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

Fig. 3.

Selected clones show a higher MCP expression and less cytotoxicity against monkey serum. a Representative MACS images of indicated clones expressing MCP over 90%. b Western blot analysis of indicated clones. c Cytotoxicity assay of indicated clones against 15% of normal monkey serum (n = 3 per group), (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Relevant full-length western blot images are shown in the supplementary information

To determine whether overexpressed MCP could lead to improved protection against cytotoxicity from the monkey complement, we cultured five clones in medium supplemented with 15% of normal monkey serum. All clones examined showed significant attenuation (P < 0.001) of cell death compared to wild type (Fig. 3c), indicating that MCP translated from codon-optimized mMCP transcripts plays a role in protection from activated complement attack. Interestingly, the monkey serum-induced cytotoxicity of the clones expressing MCP over 90% (#10, #25, #6, #24 and #26) was significantly lesser (P < 0.001) than the cells derived from GT−MCP/−MCP pig (#23–4), indicating that upregulation of MCP could provide a better anti-cytotoxicity effect.

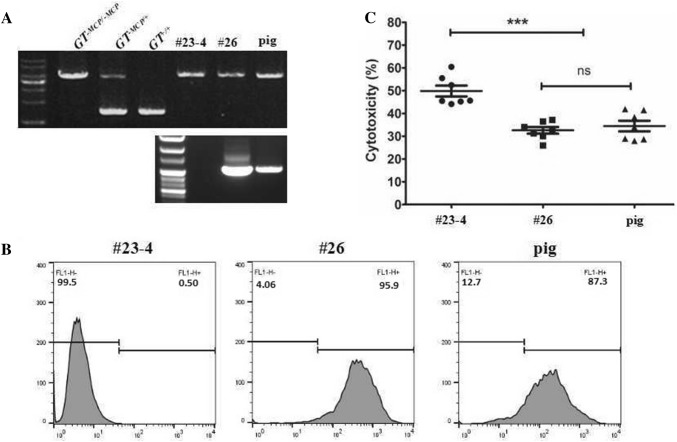

Generation of GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM Pig

We applied clone #26 as donor cells for the production of cloned-embryo. As shown in Table 3, we transferred 121.8 ± 11.2 (mean ± SD) reconstructed embryos to 13 surrogate mothers. Subsequently, we were able to generate a piglet identified as transgenic GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig (Fig. 4a). To test whether the pig cells produce MCP, we isolated ear fibroblasts of a GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM piglet and performed flow cytometry analysis using FITC-MCP antibody. We found that 87.3% of the ear fibroblasts were expressing MCP (Fig. 4b). Next, to test the functional ability of MCP, we performed in vitro cytotoxic assay using monkey serum. The survivability of the pig cells was significantly higher (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4c) when compared to wild-type cells, and was similar to donor cells (#26), suggesting GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig produce functional MCP.

Table 3.

In vitro production of cloned pig embryos

| Number of* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovaries per experiment | Oocytes recovered | Oocytes matured in vitro (%) | Oocytes reconstructed | Embryos transferred per surrogate |

| 138.5 ± 2.8 | 568 ± 21.9 | 417.2 ± 19.6 (82.1 ± 1.3) | 213.9 ± 6.0 | 121.8 ± 11.2 |

*Data are represented as means of 13 rep

Fig. 4.

Comparison of MCP expression level and functionality of cloned GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig cells with donor cells. a Genotyping analysis of cloned pig generated by nuclear transfer of GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM (#26) cells, and GT−MCP/−MCP (#23–4) as a donor. GT−MCP/−MCP representing the non-modified donor cells (#23–4), GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM (#26) the codon-optimized cells and pig representing the cloned pig. b Representative flow cytometry graphs of indicated corresponding transgenic pig cells. c Cytotoxicity assay of indicated cells against 15% normal monkey serum (n = 7 per group), (***P < 0.001). NS indicates no statistically significant difference

Discussion

In this study, we reported that the upgrade of transgenic GT−MCP/−MCP pig produces increased MCP expression and potentially endothelium-specific TBM expression. Using codon optimization bias technology, we enhanced the MCP expression of wild-type cDNA that is known to be difficult to express in vitro and in vivo. The effort of sequence modification to optimize codon usage resulted in increased GC content and changes of putative polyadenylation signal sequences located between 498 and 509 bp from the translation initiation codon. We installed dicistronic expression cassettes, which were designed to be regulated by different promoters, ubiquitous CAG, and endothelial-specific Icam2, in one construct. GT−MCP/−MCP cell successfully contributed to the generation of GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig of which primary cells express functional MCP at a high level, although TBM expression on the endothelium could not be confirmed.

GT−MCP/+ and GT−MCP/−MCP founder pigs carrying wild-type MCP cDNA under control of CMV promoter in GT loci express constantly MCP; therefore, it is difficult to explain why in this study wild-type MCP was not upregulated at the protein level under the control of CAG promoter, which is known as one of the strong promoters in pig that was used, while showing significant upregulation at the mRNA level (Lee et al. 2017). In contrast, Hurh et al. reported that the CAG promoter was sufficient to induce MCP expression and CMV promoter was not sufficient with identical MCP-2A-TBM (Hurh et al. 2013). We wondered what biochemical and molecular mechanisms were involved in post-transcriptional regulation for MCP expression. It is clear, at least in this study, that there are limitations with wild-type MCP for efficient translational control from its abundant transcripts.

Codon optimization bias has been considered as an attractive technology to increase expression at the protein level. This technology has been applied for the production of pharmaceuticals (Ward et al. 2011) and nucleic acid therapies (Frelin et al. 2004). However, it was reported that synonymous codon changes may affect protein conformation and alter protein function (Tsai et al. 2008; Agashe et al. 2012; Zucchelli et al. 2017). Mauro et al. (2014) suggested that a codon optimization approach is reconsidered, particularly for in vivo applications (Mauro and Chappell 2014). In the field of xenotransplantation research, Miyagawa et al. (2001) reported that codon exchanges of decay accelerating factor (DAF) resulted in an increase of expression at protein levels in transgenic mice, with function as a complement regulatory protein to protect complement-mediated cytotoxicity (Miyagawa et al. 2001). In this study, we showed that increased expression of MCP provided significant protection against normal monkey serum (Figs. 3c, 4c), meaning that complement regulatory proteins expressed from codon-optimized sequences, at least DAF and MCP, do not lead to functional impairment in vitro and in vivo. Although the expression of MCP was not detectable in #23–4 by western blot analysis (Figs. 2b, 3b), #23–4 provided significant protection against the cytotoxic effect of normal monkey serum compared with wild type (Fig. 3c). This implies that the functional ability of MCP depends on its expression level. However, the physiological compatibility of the GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig remains elusive.

TBM does not seem to be relevant for enhancing translation expression by codon optimization (Fig. 1c, e). We were not able to observe any difference in mRNA and protein expression levels between TBM and the mTBM in dicistronic cassettes m-pI2 and m-mpI2 (data not shown), meaning that wild-type TBM cDNA is suitable for expression in vitro and in vivo. The 1 kb size porcine Icam2 promoter used in this study was confirmed to lead to the most upregulation and endothelial cell-specific expression of reporter gene among variable sizes (personal communication with Dr. JW Lee of Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology). We also showed that the promoter led to sufficient TBM expression in HeLa cells expressing ICAM2 (Fig. 1c) and pAECs (Fig. 1e), but not in pEFs (Figs. 1d, 2b, c). We chose the m-pI2 construct to generate donor cells that could express MCP ubiquitously and TBM endothelium-specifically. The procedures of cell sorting-selection using MCP specific-antibody and MACS cell sorting along with the separation of single-cell clones were successful for the generation of a transgenic pig. From the results taken together, we believe that cardiac xenotransplantation of the GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig could prolong the survival of recipient monkey to over 60 days by the contribution of increased functioning MCP as a complement regulator and TBM as a thrombosis inhibitor in the endothelium.

In summary, we reported a genetic manipulation approach that upgraded GT−MCP/−MCP pig to GT−MCP/−MCP/mMCP/TBM pig. Codon optimization of MCP enabled genetically upgraded pigs to produce MCP at a high level. The dicistronic cassette used in this study allowed the expressions of both functional MCP and an endothelial-specific TBM. Furthermore, single clones carrying dual expression cassette were successfully selected based on MCP expression level and were subsequently used for somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Thus, the technologies used in the present study provide a simple yet reliable approach to generate new transgenic animals and to upgrade previously developed transgenic animals.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development [Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea] under Grant [Project Number PJ012022] and (2017) by Academy = Research = Industry Support Program of Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- 2A

Porcine teschovirus-1 2A

- bp

Base pair

- GTKO

Alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase homozygous knockout

- Icam2

Porcine intercellular adhesion molecule 2 (Icam2)

- MCP

Membrane cofactor protein

- pEF

Porcine ear skin fibroblasts

- pAEC

Porcine aortic endothelial cells

- SCNT

Somatic cell nuclear transfer

- TBM

Thrombomodulin

Author contributions

KBO designed the experiments. HL, BMKV, HY, and SJB performed experiments. KBO, HL, SAO, and HCL analyzed the data. IH, JSW, SH, and MIP performed in vitro culture of oocytes, nuclear transfer, and embryo transfer. HL, IH, and BMKV wrote a draft. BMKV, HRR and KBO edited the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Heasun Lee and In-sul Hwang have contributed equally.

References

- Adams DH, Kadner A, Chen RH, Farivar RS, Logan JS, Diamond LE. Human membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD 46) protects transgenic pig hearts from hyperacute rejection in primates. Xenotransplantation. 2001;8(1):36–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0908-665X.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agashe D, Martinez-Gomez NC, Drummond DA, Marx CJ. Good codons, bad transcript: large reductions in gene expression and fitness arising from synonymous mutations in a key enzyme. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;30(3):549–560. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou G, Gialeraki A, Merkouri E, Politou M, Travlou A. Thrombomodulin as a regulator of the anticoagulant pathway: implication in the development of thrombosis. Blood Coag Fibrinol. 2012;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834cb271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway EM (2012) Thrombomodulin and its role in inflammation. In: Seminars in immunopathology, 2012. vol 1. Springer, pp 107–125 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crikis S, Zhang X, Dezfouli S, Dwyer KM, Murray-Segal L, Salvaris E, Selan C, Robson S, Nandurkar H, Cowan P. Antiinflammatory and anticoagulant effects of transgenic expression of human thrombomodulin in mice. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(2):242–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelin L, Ahlen G, Alheim M, Weiland O, Barnfield C, Liljeström P, Sällberg M. Codon optimization and mRNA amplification effectively enhances the immunogenicity of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3/4A gene. Gene Ther. 2004;11(6):522. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Chen P, Wei L, Xu J, Liu L, Zhao Y, Hara H, Pan D, Li Z, Cooper DK. Angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 protect porcine iliac endothelial cells from human antibody-mediated complement-dependent cytotoxicity through phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway activation. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(4):e12309. doi: 10.1111/xen.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurh S, Cho B, You D-J, Kim H, Lee EM, Lee SH, Park SJ, Park HC, Koo OJ, Yang J. Expression analysis of combinatorial genes using a bi-cistronic T2A expression system in porcine fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e70486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S, Oh KB, Kwon D-J, Ock S-A, Lee J-W, Im G-S, Lee S-S, Lee K, Park J-K. Improvement of cloning efficiency in minipigs using post-thawed donor cells treated with roscovitine. Mol Biotechnol. 2013;55(3):212–216. doi: 10.1007/s12033-013-9671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, Bhama J, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Klein E, Wagner R, Long C, Thacker J. Pig-to-baboon heterotopic heart transplantation–exploratory preliminary experience with pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin and comparison of three costimulation blockade-based regimens. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(3):211–220. doi: 10.1111/xen.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata K, Seya T, Yanagi Y, Pesando JM, Johnson PM, Okabe M, Ueda S, Ariga H, Nagasawa S. Diversity of sites for measles virus binding and for inactivation of complement C3b and C4b on membrane cofactor protein CD46. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(25):15148–15152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko N, Lee J-W, Hwang SS, Kim B, Ock SA, Lee S-S, Im G-S, Kang M-J, Park J-K, Jong OhS. Nucleofection-Mediated α1, 3-galactosyltransferase Gene inactivation and membrane cofactor protein expression for pig-to-primate xenotransplantation. Animal biotechnology. 2013;24(4):253–267. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2012.752741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwaki K, Tseng Y-L, Dor FJ, Shimizu A, Houser SL, Sanderson TM, Lancos CJ, Prabharasuth DD, Cheng J, Moran K. Heart transplantation in baboons using α1, 3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs as donors: initial experience. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):29. doi: 10.1038/nm1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D-J, Kim D-H, Hwang I-S, Kim D-E, Kim H-J, Kim J-S, Lee K, Im G-S, Lee J-W, Hwang S. Generation of α-1, 3-galactosyltransferase knocked-out transgenic cloned pigs with knocked-in five human genes. Transgenic Res. 2017;26(1):153–163. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9979-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Park S, Lee H, Ji S, Lee J, Byun S, Hwang S, Kim K, Ock S, Oh K (2017) Development of α 1, 3-galactosyltransferase inactivated and human membrane cofactor protein expressing homozygous transgenic pigs for Xenotransplantation. J Embryo Transf

- Lee S, Kim J, Chee H, Yun I, Park K, Yang H, Park J (2018) Seven years of experiences of preclinical experiments of xeno-heart transplantation of pig to non-human primate (cynomolgus monkey). In: Transplantation proceedings, vol 4. Elsevier, pp 1167–1171 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Loveland BE, Milland J, Kyriakou P, Thorley BR, Christiansen D, Lanteri MB, van Regensburg M, Duffield M, French AJ, Williams L. Characterization of a CD46 transgenic pig and protection of transgenic kidneys against hyperacute rejection in non-immunosuppressed baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11(2):171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3089.2003.00103_11_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro VP, Chappell SA. A critical analysis of codon optimization in human therapeutics. Trends in molecular medicine. 2014;20(11):604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor Christopher G.A., Davies William R., Oi Keiji, Teotia Sumeet S., Schirmer Johannes M., Risdahl Jack M., Tazelaar Henry D., Kremers Walter K., Walker Randall C., Byrne Guerard W., Logan John S. Cardiac xenotransplantation: Recent preclinical progress with 3-month median survival. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2005;130(3):844.e1-844.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milland J, Christiansen D, Thorley BR, Mckenzie IF, Loveland BE. Translation is enhanced after silent nucleotide substitutions in A+ T-rich sequences of the coding region of CD46 cDNA. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238(1):221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0221q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenyi Stefan, Müller Werner, Weichel Walter, Radbruch Andreas. High gradient magnetic cell separation with MACS. Cytometry. 1990;11(2):231–238. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa S, Yamada M, Matsunami K, Koresawa Y, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Shirakura R. A synthetic DAF (CD55) gene based on optimal codon usage for transgenic animals. The Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;129(5):795–801. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin M. M., Corcoran P. C., Singh A. K., Azimzadeh A., Hoyt R. F., Thomas M. L., Eckhaus M. A., Seavey C., Ayares D., Pierson R. N., Horvath K. A. B-Cell Depletion Extends the Survival of GTKO.hCD46Tg Pig Heart Xenografts in Baboons for up to 8 Months. American Journal of Transplantation. 2011;12(3):763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Thomas III ML, Clark T, Lewis BG, Hoyt RF, Eckhaus M, Pierson III RN, Belli AJ (2016) Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO. hCD46. hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nat Commun 7:11138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raab D, Graf M, Notka F, Schödl T, Wagner R. The GeneOptimizer algorithm: using a sliding window approach to cope with the vast sequence space in multiparameter DNA sequence optimization. Syst Synth Biol. 2010;4(3):215–225. doi: 10.1007/s11693-010-9062-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Schaulies J, Martin MJ, Logan JS, Firsching R, ter Meulen V, Diamond LE. CD46 transgene expression in pig peripheral blood mononuclear cells does not alter their susceptibility to measles virus or their capacity to downregulate endogenous and transgenic CD46. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(6):1431–1438. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C-J, Sauna ZE, Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM, Nussinov R. Synonymous mutations and ribosome stalling can lead to altered folding pathways and distinct minima. J Mol Biol. 2008;383(2):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NJ, Buckley SM, Waddington SN, VandenDriessche T, Chuah MK, Nathwani AC, McIntosh J, Tuddenham EG, Kinnon C, Thrasher AJ. Codon optimization of human factor VIII cDNAs leads to high-level expression. Blood. 2011;117(3):798–807. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Wei X, Zhang J, Yi B, Zhang G-X, Yin L, Yang X-F, Sun J. Antithrombotic effects of Nur77 and Nor1 are mediated through upregulating thrombomodulin expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(2):361–369. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchelli E, Pema M, Stornaiuolo A, Piovan C, Scavullo C, Giuliani E, Bossi S, Corna S, Asperti C, Bordignon C. Codon optimization leads to functional impairment of RD114-TR envelope glycoprotein. Mol Therap Methods Clin Dev. 2017;4:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.