Abstract

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) can be attributed to cardiac, respiratory, metabolic, and toxicologic etiologies. Most cases of SCD are caused by coronary artery disease and approximately 40% of cardiac arrests are unexplained1. Inherited arrythmias and cardiomyopathies are important contributors to SCA and SCD. Identifying an inherited condition after such an event not only has important ramifications for the individual, but also for relatives who may be at-risk for the familial condition. This review will provide an overview of inherited cardiovascular disorders than can predispose to SCA/SCD, review the diagnostic evaluation for an individual and/or family after a SCA/SCD, and discuss the role of genetic testing.

Keywords: sudden cardiac arrest, sudden cardiac death, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, gene, genetic testing, mutation

Case 1:

A 20-year-old female had been diagnosed with a seizure disorder, despite normal neurologic evaluations. The patient was noted to have an abnormal EKG with marked prolongation of the QTc interval. A Holter monitor revealed nonsustained polymorphic VT. Her family history was notable for her maternal aunt and maternal grandmother having died suddenly at ages 19 and 29, respectively.

Case 2:

A 19-year-old female, collegiate soccer player was noted to have an abnormal ECG with T wave inversions in V1-V3 during a preseason evaluation. A Holter monitor revealed frequent PVCs. An echo demonstrated a mildly enlarged right ventricle with an apical wall motion abnormality. Cardiac MRI confirmed areas of fibrosis corresponding to the wall motion abnormality. She reported a paternal cousin who experienced sudden cardiac arrest while running track and has an ICD.

Case 3:

A 49-year old man suffered a sudden cardiac arrest while lifting weights at the gym. He underwent cardiovascular evaluation: coronary angiography was negative and echocardiogram and cardiac MRI did not identify an overt cardiomyopathy. His resting electrocardiogram demonstrated 1st degree AV block and nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay, but there was no Brugada pattern or QT prolongation. There was no clear family history of cardiomyopathy or arrhythmia although he reported his father required a pacemaker in his 60s. He was diagnosed with idiopathic VF arrest and an ICD was placed.

Mendelian genetic disorders are conditions in which variation in a single gene is sufficient to cause disease. Multiple Mendelian disorders can present with SCA/SCD (Table 1). Inherited arrhythmias are primary electrical disorders and include long QT syndrome (LQTS), Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). LQTS is characterized by QT prolongation in the absence of a secondary cause (e.g. drug induced QT prolongation, electrolyte imbalance) and is associated with ventricular arrythmias, particularly torsade des pointes. Up to 80% of cases have an identifiable genetic etiology, with the majority of cases caused by variants in genes encoding potassium or sodium ion channels, namely KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A2. Brugada syndrome is defined as type 1 ST-segment elevation in at-least one right precordial lead. A characteristic Brugada pattern observed spontaneously or induced during a drug challenge are both considered diagnostic. Most cases of Brugada syndrome with an identifiable genetic etiology are due to variation in the SCN5A gene3. Catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia is characterized by polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that is often exercise-induced; greater than 50% of cases are attributed variants in the RYR2 gene2.

Table 1.

Key clinical features of inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies

| Characteristic Clinical Findings | Arrhythmic Triggers | Predominant Causative Genes | Genetic Testing Yield | Impact of Genetic Testing on Clinical Management | Phenocopies and Syndromic Presentations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inherited Arrhythmias | ||||||

| Long QT syndrome | Prolonged QT interval in the absence of a secondary cause (eg. QT-prolonging medications, electrolyte imbalance) | Type 1 (KCNQ1): Exercise Type 2 (KCNH2): Auditory stimuli Type 3 (SCN5A): Sleep or rest |

KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A | 80% | Diagnostic criterion Indication for beta-blocker therapy Lifestyle modification: avoid QT prolonging medication Cascade genetic testing |

Jervell-Lange Nielsen syndrome Andersen-Tawil syndrome |

| Brugada syndrome | Type 1 ST-segment elevation in at least 1 right precordial lead observed spontaneously or after provocative drug challenge | Sleep or rest | SCN5A | 25% | Lifestyle modification: avoid sodium channel-blocking medication, treat fevers with antipyretics Cascade genetic testing |

|

| Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia | Adrenergic-induced bidirectional and polymorphic VT | Exercise or intense emotion | RYR2 | 50% | Diagnostic criterion Cascade genetic testing |

|

| Inherited Cardiomyopathies | ||||||

| Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy | Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy with predominant RV involvement; LBBB, VT, fibro-fatty replacement of RV. | Exercise | Desmosomal genes (PKP2, DSP, DSC2, DSG2, JUP) and others | 50% | Diagnostic criterion Lifestyle modification: avoid high-intensity endurance exercise Cascade genetic testing |

|

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy | Idiopathic left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction | Sarcomeric genes, cytoskeleton genes | 40% | Indication for ICD placement (LMNA) Cascade genetic testing |

Danon disease Skeletal myopathies Mitochondrial disorders |

|

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy | Unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy | Sarcomeric genes (MYBPC3, MYH7, TNNT2, TNNI3, TPM1, MYL3, MYL2, ACTC1) | 60% | Cascade genetic testing | RASopathies Fabry disease Pompe disease Danon disease Other infiltrative disorders (e.g. PRKAG2, TTR) Mitochondrial disorders |

|

Inherited cardiomyopathies may also present with SCA/SCD, including arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies (ACM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies (ACM) typically include arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), characterized by predominant right ventricular (RV) disease, as well as ventricular tachycardia, and fibro-fatty replacement of the RV4. Patients with ARVC can experience arrhythmias prior to the development of overt cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias are often exercise-induced. ARVC is typically an autosomal dominant disorder caused by variation in genes encoding desmosomal proteins and a causative variant is identified in up to 50% of cases5. It has been recognized that some individuals with ACM have biventricular disease or predominant left ventricle-disease, referred to as arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy (ALVC). ALVC has been associated with desmosomal, sarcomeric and cytoskeleton genes, thus sharing a genetic basis with both ARVC and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). DCM, characterized by idiopathic left ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction, has an identifiable genetic basis in up to 40% of individuals6. Genetic causes of DCM include variation in sarcomere and cytoskeleton genes, with variants in titin (TTN) accounting for approximately 15–25% of cases6,7. Variants in lamin A/C (LMNA) are responsible for approximately 5% cases and patients often present with progressive conduction system disease and/or ventricular arrhythmias, which may precede the development of cardiomyopathy6. Lastly, SCA/SCD can be the first presenting symptom in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), characterized by unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy. HCM is primarily due to variation in genes encoding the sarcomere and a causative variant is identified in up to 60% of cases5.

Some inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies represent genetic syndromes which involve extracardiac organ systems (Table 1). Examples include Jervell and Lange Nielson syndrome, (characterized by QT prolongation and congenital sensorineural hearing loss), Danon disease (characterized by hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, and intellectual disability), and Fabry disease (characterized by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, end-stage renal disease, angiokeratomas, and periodic pain crises). Cardiac disease may be the first recognized manifestation of the syndrome and confirmation of the diagnosis may help guide the affected individual’s medical management and treatment, such as in the case of Fabry disease, where enzyme replacement therapy is available.

Genetic principles of inherited cardiovascular disease

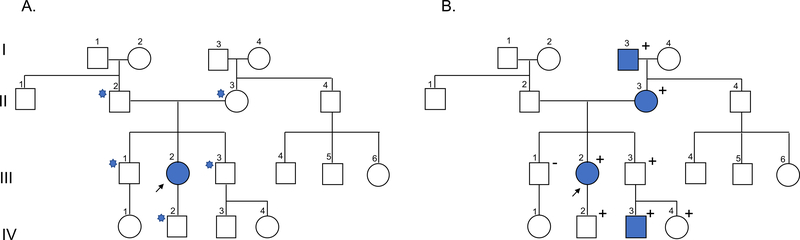

Inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies share common genetic principles (Figure 1). In most families, these conditions are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, meaning a single genetic alteration (variant) on one copy (allele) of the gene is sufficient to cause disease. Presuming the variant was inherited from one of the affected individual’s parents, the individual’s other first-degree relatives have a 50% chance to be at-risk for the condition from the same variant. If a variant is not inherited from a parent but rather occurred spontaneously (de novo) in the affected individual, the chance that the affected individual’s siblings inherited the variant is significantly reduced. Examples of cardiovascular conditions with autosomal recessive inheritance, where an affected individual must inherit two variants on opposite alleles (typically one from each parent), include CPVT caused by biallelic variants in CASQ2 or biallelic variants in CALM1, CALM2, CALM3, and TRDN associated with early-onset, severe arrhythmia phenotypes. X-linked inheritance refers to variants inherited on the X chromosome, and males may be more severely affected than females. Examples of cardiovascular conditions with X-linked inheritance include Fabry disease and Danon disease. Lastly, cardiomyopathy may be a feature of some mitochondrial disorders, inherited from the maternal mitochondrial DNA.

Figure 1.

A) Pedigree illustrating the affected proband (III-2) and her first-degree at-risk relatives (II-2, II-3, III-1, III-3, IV-2). B) Pedigree illustrating autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance (III-3), age-dependent penetrance (IV-2), and the role of cascade genetic testing. Legend: squares indicate males, circles indicate females; shaded indicates affected; positive sign indicates presence of genetic variant, negative sign indicates absence of genetic variant; star indicates first-degree relative of proband

Most inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies demonstrate variable disease expression where relatives from the same family can have different clinical presentations. Additionally, many of these disorders demonstrate age-dependent penetrance, meaning the condition is more likely to present with increasing age; and reduced penetrance, where some individuals who harbor the variant may never develop disease. Therefore, if an individual is suspected to have an inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy but has no apparent family history, it remains possible that other family members harbor the familial variant and have sub-clinical disease or have not yet developed disease.

Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular disease

Genetic testing is widely available for inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies. Genetic testing typically includes DNA sequencing to assess for an alteration at a single nucleotide (single nucleotide variants; SNVs) as well as analysis for deleted or duplicated portions of DNA (copy number variants; CNVs). There are a variety of genetic tests, ranging from a focused assessment of a particular SNV or CNV to broad genetic testing where the exome (protein-coding region of each gene, e.g exon) or whole genome (which in addition to the protein-coding region also includes the non-coding region of each gene, e.g. intron) are analyzed. If there is suspicion that an individual has a specific inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy, a disease-specific panel is generally performed. Depending on the condition and laboratory, disease-specific panels may range from <10 genes to >100 genes. Larger panels, however, may include genes where there is limited evidence supporting their association with disease, providing minimal additional diagnostic yield but increasing the detection of variants of unclear clinical significance8. Therefore, consideration of panel size and appropriateness is warranted. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), an NIH-sponsored program, is leading efforts to assess gene-disease associations, which can guide panel development and selection9. Evaluation of genes associated with Brugada syndrome and HCM have already been published3,10.

More focused genetic testing, such as analysis of a single gene, may be considered if the patient has a distinct phenotype. For example, if a patient has a history of left ventricular hypertrophy, end-stage renal disease, and physical exam findings consistent with a diagnosis of Fabry disease, sequencing of GLA alone would be appropriate. In contrast, exome and genome sequencing are increasingly available and may be beneficial in cases where there is evidence of familial disease and panel testing has not identified a causative variant. Exome and genome sequencing are most effective when samples from multiple affected relatives are analyzed together, allowing for filtering and identification of variants that are shared amongst the affected individuals. However, the utility of routinely performing exome and genome sequencing in families with inherited cardiovascular disease is yet to be established 11–13.

Careful interpretation of genetic test results is critical to appropriately care for the patients and their relatives. Genetic variants represent a continuum ranging from benign variants with no evidence for disease association to pathogenic variants with well-established evidence for disease association. In 2015, the American College of Medical Genetics published recommendations to aid in the standardization of variant interpretation14. According to these recommendations, variants are classified into five categories (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variant of uncertain significance, benign, and likely benign) based on the cumulative evidence supporting pathogenicity from population, functional, computational, and familial data. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic results are generally considered positive results that may be considered for clinical decision-making. However, clinicians should be aware that likely pathogenic variants have a lesser amount of evidence supporting their pathogenicity and understanding of the variant’s association with disease may continue to evolve. In contrast, likely benign and benign variants are considered negative results.

A variant of uncertain significance (VUS) is an inconclusive result where there is either insufficient evidence or conflicting evidence regarding the variant’s pathogenicity. Therefore, a VUS does not provide molecular confirmation of a diagnosis. Additionally, genetic testing for a VUS should not be performed in other healthy relatives to clarify their risk for disease. However, in families where there are multiple affected individuals, genetic testing for the VUS in other affected relatives may help clarify its significance by determining whether the variant co-segregates with disease in the family. Both clinicians and patients should be aware of the possibility that a variant may be reclassified as additional evidence is accumulated. In order to promote data-sharing and improve the quality of variant interpretation, the ClinGen program developed ClinVar, a publicly-accessible database where laboratories, researchers, and other entities can submit variant annotations9.

Genetic testing has become increasingly accessible over the past decade. The cost of genetic testing has decreased dramatically and many laboratories in the United States offer competitive billing policies, including third-party billing, self-pay policies where patients’ out-of-pocket costs are limited, and free testing for relatives. Laboratories also accept a variety of sample types including blood, saliva, buccal swabs, allowing for the samples to be collected from the patient’s home, if needed. For post-mortem genetic testing in cases of SCD, whole blood, flash-frozen tissue, and in some cases blood spot cards or paraffin-embedded tissue, may be accepted15.

Patients pursuing genetic testing should consider the potential for genetic discrimination. In the United States, the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act was passed in 2008 and provides protections against genetic discrimination by most health insurance companies and employers, although some exceptions exist. Notably, the law does not offer protections against genetic discrimination by other forms of insurance including life, disability or long-term care insurance 16. Legal protections against genetic discrimination in other countries may vary. Genetic discrimination is an especially pertinent concern for at-risk relatives undergoing genetic testing for a familial variant, as they might not have clinical manifestations of disease.

Evaluations after SCA/SCD

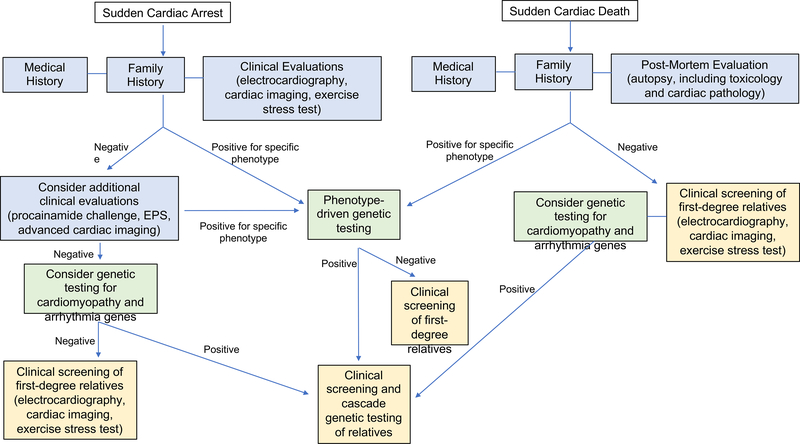

When evaluating SCA survivors for whom there is concern for an underlying inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy, the following evaluations should be considered: a detailed medical history including the circumstances of the event (e.g. exercise, sleep); family history; cardiovascular testing including electrocardiography, cardiac imaging, exercise stress-testing, and possible provocative testing such as a procainamide challenge; genetic testing; and possible cardiac evaluations and genetic testing in other family members (Figure 2). The role of electrophysiology studies in SCA survivors is uncertain but may have value17. In cases of SCD, a complete autopsy including toxicology screening, cardiac pathology, and retention of specimens suitable for post-mortem genetic testing, is recommended18. Additionally, a medical history including the circumstances of the SCD and family history should be reviewed18. If any cardiac testing was performed prior to the individual’s death, medical records should be obtained when possible.

Figure 2.

Suggested algorithm for evaluation of SCA survivors and families after a SCD.

Specific testing considerations are discussed in the manuscript text.

A detailed family history should be reviewed to ascertain any relatives with a related phenotype, assess possible inheritance patterns in the family, and identify other at-risk relatives. Family history should be obtained for at-least three generations, recording any individuals with arrythmias, cardiomyopathies, syncope, seizures, cardiac devices, cardiac surgeries or transplants, sudden deaths, and unexplained deaths or accidents that may have been caused by underlying arrhythmia (e.g. single motor vehicle accidents, drownings). When possible, medical records, autopsy reports, and genetic test results from other family members should be obtained to verify diagnoses. The family history, or patients’ knowledge of their family history, may evolve and should thus be updated at subsequent appointments.

Additional cardiac testing may establish a diagnosis of an inherited condition in some SCA survivors without overt cardiac disease on initial evaluation. For example, exercise testing, and perhaps epinephrine challenges, may elicit a phenotype in individuals with CPVT or LQTS. A procainamide infusion may identify individuals with Brugada syndrome. Use of advanced cardiac imaging, such as cardiac MRI, may identify genetic phenotypes not readily identifiable with echocardiography including apical variant HCM or ARVC. Cardiac PET imaging may identify individuals with nongenetic phenotypes, such as myocarditis or sarcoidosis, where further genetic and family evaluation is not necessarily warranted. Studies have reported that additional cardiac testing including advanced imaging and provocative testing in individuals with unexplained SCA contributes to a diagnosis of an inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy in 41–62% of patients19–21.

If a clinical diagnosis of a specific inherited arrythmia or cardiomyopathy is established or highly suspected, all first-degree relatives should undergo cardiac evaluations to identify other relatives with sub-clinical disease5,18. Given that many of these conditions demonstrate age-dependent penetrance, longitudinal cardiac evaluations may be indicated. In cases of unexplained SCA or SCD, cardiac evaluations, including ECG, exercise stress-testing, and echocardiogram, are recommended in the individual’s first-degree relatives18. Additional cardiac testing may be warranted in some circumstances. Cardiac evaluations may identify a family member with an overt phenotype, helping to clarify the familial diagnosis. The reported yield of cardiac evaluations in relatives after an unexplained SCA or SCD has been variable, ranging from 13–40%1,20,22–25. Factors such as the age of the index case, family history, and screening modalities may influence the yield of family screening.

If a clinical diagnosis of a specific inherited arrythmia or cardiomyopathy is established or highly suspected, genetic testing may be helpful to molecularly confirm the diagnosis and should be performed according to standard practice2,5,18. If there is a family history of the condition, genetic testing should ideally be pursued in the most severely affected individual first, due to the possibility that more than one variant is contributing to the phenotype in the family. The appropriate genetic test will be informed by the patient’s phenotype or index of suspicion for the phenotype, highlighting the importance of thorough phenotyping prior to genetic testing. The yield of genetic testing depends on the particular phenotype in question, ranging from approximately 25% up to 80% (Table 1). It is important to note that a negative genetic test result in the index case (proband) does not eliminate the possibility of a genetic etiology and relatives may still be at risk for disease. In cases where a causative variant is identified, genetic testing for the familial variant can be pursued in other relatives to clarify their risk (“cascade genetic testing”).

Genetic testing can be useful in cases of unexplained SCA or SCD18,26. Early studies of unexplained SCD focused on genetic testing for a small number of genes, primarily KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A and RYR2, establishing that inherited arrhythmias account for a portion of unexplained SCD 27,28. With the advent of next-gene sequencing and decreased cost of multi-gene panels, larger panels including both arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy genes may be appropriate in cases of unexplained SCA or SCD. Broad genetic testing panels allow for the identification of individuals with ACM who have not yet developed an overt cardiomyopathy, or individuals in whom a condition was regarded as possibly nongenetic, such as drug-induced LQTS. Broad genetic testing panels, or even more comprehensive exome or genome sequencing, may be helpful when there are multiple affected relatives and family mapping of a variant is feasible or when a de novo variant is highly suspected. However, the benefits of such testing should be weighed with the potential of identifying variants of uncertain significance, which warrant careful interpretation. Families should be counseled regarding this possibility, the potential confusion these variants may cause, and the limits of current ability to provide reliable clinical interpretation of these variants.

Multiple studies have investigated the yield of genetic testing in survivors of unexplained SCA and post-mortem genetic testing after SCD1,20,21,25,29–33. In a recent study of 375 cardiac arrest survivors, genetic testing identified a pathogenic variant 17% of individuals, including 11% of phenotype-negative individuals21. Recent studies of post-mortem genetic testing in cases of sudden unexplained cardiac death have reported yields ranging from 13–27%1,25. In one study, post-mortem genetic testing in addition to family screening increased the diagnostic yield from 26% to 39%25. To summarize, the reported yield of genetic testing in unexplained SCA and SCD has been variable, and an ideal approach to evaluating families combines both genetic and clinical evaluations.

Post-mortem genetic testing requires careful coordination between the medical examiner, genetic testing laboratory, clinician, and family. Families should receive thorough counseling and be provided with anticipatory guidance on the expected yield of genetic testing, implications of various types of test results for family members, including the potential for an uninformative result. Informed consent for genetic testing should be obtained from the next of kin. In some cases, there may not be available sample or permission to perform genetic testing on the decedent; however, caution should be exercised when considering using an unaffected relative as the initial genetic testing proband in the family. More specifically, interpreting an uninformative result in an unaffected relative is challenging, as it does not distinguish between two scenarios: 1) there is an identifiable genetic cause of disease in the family and the relative that was tested did not inherit the variant or 2) there is not a genetic cause in the family that can be identified with current testing. When possible, post-mortem genetic test results should be correlated with the phenotypes of the decedent and other family members.

Impact of genetic testing on the patient and family

Genetic testing can have important implications for the patient. First, a positive genetic test result may be considered criteria to facilitate a diagnosis, such as with LQTS, CPVT, and ARVC4,18,34. In some cases, a positive genetic test result may also guide the patient’s medical management. For example, individuals diagnosed with LQTS are advised to avoid QT-prolongating medications and beta-blocker therapy is recommended, even for individuals with a genetic diagnosis but normal QT intervals18. In families with ARVC, it is recommended that individuals who are genotype-positive but phenotype-negative avoid high-intensity endurance exercise, which is thought to promote the development of ARVC4. Genetic test results may also influence the decision for placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), as is the case in LMNA-cardiomyopathy where individuals may be at-risk for ventricular arrhythmias prior to the development of cardiomyopathy26.

Genetic testing can also clarify the inheritance pattern, helping to inform the individual’s reproductive risk. Identification of a causative variant allows for the utilization of assisted reproductive technologies, such as preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M). Via a process of in-vitro fertilization and subsequent genetic testing of embryos, PGT-M allows for the selection of embryos that did not inherit the familial variant. Other mechanisms of reproductive testing, such as prenatal diagnosis via chronic villus sampling or amniocentesis, may also be available to families.

Lastly, genetic testing has important implications for the patient’s family members. After a causative variant is identified in the proband, cascade genetic testing for the variant can be pursued in their at-risk relatives to clarify their risk for disease. In the absence of a genetic diagnosis in the proband, it is generally recommended that first-degree relatives undergo longitudinal clinical evaluations to assess for disease development. However, cascade genetic testing enables relatives to more definitively understand their risk, and a positive genetic test result in the proband has been shown to increase the uptake of evaluations in at-risk relatives35,36. Of note, cascade genetic is not appropriate if the proband’s genetic test results were uninformative.

Genetic counseling and multi-disciplinary care

Genetic counseling is defined as “the process of helping patients understand and adapt to the medical, psychological and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease”37. Genetic counselors have training in medical genetics and counseling theory, allowing them to address both the educational and psychosocial needs of patients diagnosed with or at-risk for an inherited condition. Genetic counseling is recommended for all patients and relatives with an inherited cardiovascular condition and genetic counselors are an integral part of the multi-disciplinary team caring for these families2,38. A genetic counselor may be involved in patient care in the following capacities: generating and assessing a detailed family history; providing educational counseling about inheritance, risk to relatives and screening recommendations; providing pre-testing counseling including discussion of the benefits, limitations and implications of genetic testing; coordinating testing and selecting the appropriate genetic test; interpreting and communicating test results; providing emotional support; supporting the patients’ communication of genetic risk to their family members, which may include the provision of written materials to aid in family communication38,39. Genetic counseling and psychological support for families after a SCD is particularly important, as prior research has demonstrated that nearly 50% of family members experience prolonged grief or post-traumatic stress syndrome after the sudden death of a relative, and a significant portion of relatives report poor adaptation to genetic information after post-mortem genetic testing40,41.

In summary, inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies are important contributors to SCA and SCD. Establishing a diagnosis of an inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy has the potential to influence the patient’s medical management and inform their prognosis; additionally, a genetic diagnosis has important implications for relatives who may be at-risk and benefit from risk stratification for SCD prevention. Genetic testing, in addition to clinical evaluations, can play an important role in diagnosing a familial condition. Careful consideration should be given to test selection, variant interpretation, and the provision of genetic counseling. Given the unique clinical, psychosocial and familial aspects of caring for families with inherited cardiovascular disease, patients may benefit from evaluation by a multi-disciplinary program specialized in cardiovascular genetics42.

Case 1:

A LQTS genetic testing panel was performed which revealed a heterozygous pathogenic variant in KCNH2, consistent with a diagnosis of long QT type 2. The patient was started on a beta blocker and advised to avoid QT-prolonging medications. Additionally, clinical screening and cascade genetic testing for the KCNH2 variant were recommended to identify other at-risk relatives.

The patient had recurrent symptoms despite beta blockade and ultimately a dual chamber ICD was implanted. She later experienced ICD therapy for VF after being startled by a loud siren while driving, a characteristic arrhythmic trigger for individuals with LQTS type 2.

Case 2:

Further assessment of her family history revealed that the patient’s paternal cousin was diagnosed with ARVC and found to harbor a pathogenic variant in PKP2. The patient underwent targeted genetic testing for the familial variant, which was positive, helping to establish a diagnosis of ARVC and allowing for appropriate risk stratification including discussion of an ICD. Additionally, her genetic testing implied that her father was an obligate carrier for the PKP2 variant and prompted further cascade genetic testing in the family. Genotype-positive relatives underwent cardiac evaluation and were counseled to avoid high-intensity endurance exercise.

Case 3:

A comprehensive cardiomyopathy and arrhythmia genetic testing panel was ordered, which identified a pathogenic variant in SCN5A. Variants in SCN5A are associated with LQTS, Brugada syndrome, dilated cardiomyopathy, and conduction system disease. The SCN5A variant was strongly suspected to have contributed to the patient’s cardiac arrest, although he did not demonstrate characteristic findings of LQTS or Brugada syndrome. It was recommended the patient have routine cardiac evaluations, avoid sodium channel-blocking medications, and treat fevers with antipyretics. Clinical screening for arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy were recommended for first-degree relatives and cascade genetic testing for the SCN5A variant was offered to identify other at-risk individuals.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Dr. Lubitz is supported by NIH grant 1R01HL139731 and American Heart Association 18SFRN34250007. Dr. Lubitz receives sponsored research support from Bristol Myers Squibb / Pfizer, Bayer AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has consulted for Bristol Myers Squibb / Pfizer and Bayer AG.

References

- 1.Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J, et al. A prospective study of sudden cardiac death among children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2441–2452. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, et al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies. Europace. 2011;13(8):1077–1109. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosseini SM, Kim R, Udupa S, et al. Reappraisal of reported genes for sudden arrhythmic death: Evidence-based evaluation of gene validity for brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2018;138(12):1195–1205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Hear Rhythm. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershberger RE, Givertz MM, Ho CY, et al. Genetic Evaluation of Cardiomyopathy—A Heart Failure Society of America Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2018;24(5):281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugh TJ, Kelly MA, Gowrisankar S, et al. The landscape of genetic variation in dilated cardiomyopathy as surveyed by clinical DNA sequencing. Genet Med. 2014;16(8):601–608. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MRG, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns C, Bagnall RD, Lam L, Semsarian C, Ingles J. Multiple Gene Variants in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Era of Next-Generation Sequencing. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(4):1–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehm HL, Berg JS, Brooks LD, et al. ClinGen — The Clinical Genome Resource. N Engl J Med. 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1406261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingles J, Goldstein J, Thaxton C, et al. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genes. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2019;12(2):57–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoche AE, Horvat C, Johnson R, et al. Genome sequencing as a first-line genetic test in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Genet Med. 2019;21(3):650–662. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0084-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagnall RD, Ingles J, Dinger ME, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Improves Outcomes of Genetic Testing in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirino AL, Lakdawala NK, Mcdonough B, et al. HHS Public Access. 2018;10(5):1–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001768.A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baudhuin LM, Leduc C, Train LJ, et al. Technical Advances for the Clinical Genomic Evaluation of Sudden Cardiac Death: Verification of Next-Generation Sequencing Panels for Hereditary Cardiovascular Conditions Using Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues and Dried Blood Spots. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(6):1–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prince AER, Roche MI. Genetic Information, Non-Discrimination, and Privacy Protections in Genetic Counseling Practice. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(6):891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9743-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts JD, Gollob MH, Young C, et al. Bundle Branch Re-Entrant Ventricular Tachycardia: Novel Genetic Mechanisms in a Life-Threatening Arrhythmia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3(3):276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Inherited Primary Arrhythmia Syndromes: Document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Hear Rhythm. 2013;10(12):1932–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krahn AD, Healey JS, Chauhan V, et al. Systematic assessment of patients with unexplained cardiac arrest: Cardiac arrest survivors with preserved ejection fraction registry (CASPER). Circulation. 2009;120(4):278–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Peters S, Thompson T, et al. Familial cardiological and targeted genetic evaluation: Low yield in sudden unexplained death and high yield in unexplained cardiac arrest syndromes. Hear Rhythm. 2013;10(11):1653–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellor G, Laksman ZWM, Tadros R, et al. Genetic Testing in the Evaluation of Unexplained Cardiac Arrest: From the CASPER (Cardiac Arrest Survivors with Preserved Ejection Fraction Registry). Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(3). doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGorrian C, Constant O, Harper N, et al. Family-based cardiac screening in relatives of victims of sudden arrhythmic death syndrome. Europace. 2013;15(7):1050–1058. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Der Werf C, Hofman N, Tan HL, et al. Diagnostic yield in sudden unexplained death and aborted cardiac arrest in the young: The experience of a tertiary referral center in the Netherlands. Hear Rhythm. 2010;7(10):1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan HL, Hofman N, Van Langen IM, Van Der Wal AC, Wilde AAM. Sudden unexplained death: Heritability and diagnostic yield of cardiological and genetic examination in surviving relatives. Circulation. 2005;112(2):207–213. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.522581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahrouchi N, Raju H, Lodder EM, et al. Utility of Post-Mortem Genetic Testing in Cases of Sudden Arrhythmic Death Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(17):2134–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Hear Rhythm. 2018;15(10):e190–e252. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahrouchi N, Behr ER, Bezzina CR. Next-Generation Sequencing in Post-mortem Genetic Testing of Young Sudden Cardiac Death Cases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3(May):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2016.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wijeyeratne YD, Behr ER. Sudden death and cardiac arrest without phenotype: the utility of genetic testing. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2017;27(3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lahrouchi N, Raju H, Lodder EM, et al. The yield of postmortem genetic testing in sudden death cases with structural findings at autopsy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0500-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asatryan B, Schaller A, Seiler J, et al. Usefulness of Genetic Testing in Sudden Cardiac Arrest Survivors With or Without Previous Clinical Evidence of Heart Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(12):2031–2038. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunn LM, Lopes LR, Syrris P, et al. Diagnostic yield of molecular autopsy in patients with sudden arrhythmic death syndrome using targeted exome sequencing. Europace. 2016;18(6):888–896. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson JH, Tester DJ, Will ML, Ackerman MJ. Whole-exome molecular autopsy after exertion-related sudden unexplained death in the young. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9(3):259–265. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagnall RD, Das K J, Duflou J, Semsarian C. Exome analysis-based molecular autopsy in cases of sudden unexplained death in the young. Hear Rhythm. 2014;11(4):655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia: Proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010;121(13):1533–1541. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris S, Cirino AL, Carr CW, et al. The uptake of family screening in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and an online video intervention to facilitate family communication. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;(February):1–10. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanninen M, Klein GJ, Laksman Z, et al. Reduced Uptake of Family Screening in Genotype-Negative Versus Genotype-Positive Long QT Syndrome. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(4):558–564. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9776-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resta RG. Defining and redefining the scope and goals of genetic counseling. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C(4):269–275. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingles J, Yeates L, Semsarian C. The emerging role of the cardiac genetic counselor. Hear Rhythm. 2011;8(12):1958–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuter C, Grove ME, Orland K, Spoonamore K, Caleshu C. Clinical Cardiovascular Genetic Counselors Take a Leading Role in Team-based Variant Classification. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0175-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingles J, Spinks C, Yeates L, McGeechan K, Kasparian N, Semsarian C. Posttraumatic stressand prolonged grief after the sudden cardiac death of a young relative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(3):402–405. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates K, Sweeting J, Yeates L, McDonald K, Semsarian C, Ingles J. Psychological adaptation to molecular autopsy findings following sudden cardiac death in the young. Genet Med. 2019;21(6):1452–1456. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0338-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmad F, McNally EM, Ackerman MJ, et al. Establishment of Specialized Clinical Cardiovascular Genetics Programs: Recognizing the Need and Meeting Standards: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2019;12(6):e000054. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]