Abstract

Objective

Knowledge about factors influencing choice of and adherence to active surveillance (AS) for prostate cancer (PC) is scarce. We aim to identify which factors most affected choosing and adhering to AS and to quantify their relative importance.

Design, setting and participants

In 2015, we sent a questionnaire to all Swedish men aged ≤70 years registered in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden who were diagnosed in 2008 with low-risk PC and had undergone prostatectomy, radiotherapy or started on AS.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to calculate ORs with 95% CIs for factors potentially affecting choice and adherence to AS.

Results

1288 out of 1720 men (75%) responded, 451 (35%) chose AS and 837 (65%) underwent curative treatment. Of those starting on AS, 238 (53%) diverted to treatment within 7 years. Most men (83%) choose AS because ‘My doctor recommended AS’. Factors associated with choosing AS over treatment were older age (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.54), a Charlson Comorbidity Index >2 (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.13), being unaccompanied when notified of the cancer diagnosis (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.89). Men with a higher prostate-specific antigen (PSA) at the time of diagnosis were less likely to adhere to AS (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.63). The reason for having treatment after initial AS was ‘the PSA level was rising’ in 55% and biopsy findings in 36%.

Conclusions

A doctor’s recommendation strongly affects which treatment is chosen for men with low-risk PC. Rising PSA values were the main factor for initiating treatment for men on AS. These findings need be considered by healthcare providers who wish to increase the uptake of and adherence to AS.

Keywords: prostate disease, urological tumours, protocols & guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of our study include its population-based design, the high response rate for a study of its kind, the face-validated study-specific questionnaire and the direct questions on reasons for choice and adherence.

The retrospective design is a limitation, as the men’s experiences during the 7-year follow-up might have affected their recollection of their experiences.

We acknowledge that various selection mechanisms may have affected the men’s choice of treatment and that several important factors, therefore, could have been missed.

We did not have access to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels during the active surveillance (AS), only at diagnosis, which limits the possibility to investigate how PSA monitoring affects adherence to AS.

The study included Swedish men only and the findings might, therefore, not be generalisable to other cultural and healthcare settings.

Introduction

A large proportion of men with prostate cancer (PC) are diagnosed with low-risk disease with a long-life expectancy even without curative treatment. Active surveillance (AS) has, therefore, emerged as the primary strategy for these men to reduce unnecessary treatment.1 2

In Sweden, uptake of AS has increased steadily over the past decade and is now 80%–90%.3 However, the proportion of men with low-risk cancer who are on AS varies substantially between and within countries2 4 Although notable rising trends are seen in, for example, North America, Australia and Europe,5 a 2014 survey in Japan noted that roughly half of urologists used AS in <5% of men with low-risk PC and that only 27% stated that they would want to offer AS more frequently in the future.6 Additionally, a considerable proportion of men on AS diverge to treatment over time without any clear evidence of disease progression.7 8

In a systematic review on choice and adherence to AS, Kinsella et al 9 identify several factors such as clinician’s attitudes, family and social support, and patient education as potential determinants for choice and adherence to AS. However, no grading of these factors’ relative importance was made.

We could not identify any previous studies on factors influencing choice of and adherence to AS in a nationwide population-based setting. In this nationwide population-based study, representing a period in time when Sweden experienced a rapid increase in AS,3 we used a questionnaire to identify which factors most affected choosing and adhering to AS, and to quantify the relative importance of different reasons for this, thereby identifying possibly influenceable determinants to increase the implementation of AS.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

We identified all men in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR) who were diagnosed in 2008 with low-risk PC at age 70 years or younger, had radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy or AS as primary treatment and were alive in 2015. The reason for choosing men diagnosed in 2008 was that we wished to assess reasons for diverting from AS to treatment after several years of AS. The reason for choosing men younger than 70 years with low-risk disease was to avoid getting men in watchful waiting mixed with the AS group.

The NPCR has a capture rate of >96% compared with the national cancer registry, to which registration is mandatory by law.10 Low-risk disease was defined as Gleason score 6, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) <10 ng/mL and clinical stage T1 or T2.

Between February and October 2015, 1720 men were invited to participate via a letter, in which we presented the study and its purpose. The letter included a questionnaire and an addressed and stamped envelope for reply. The participants could also fill out the questionnaire online by using an individual code which was included in the letter. Men who failed to return the questionnaire were contacted by a research assistant via telephone and were sent a second questionnaire.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire consisted of EPIC-26 and 49 study-specific questions (online supplementary appendix 1). EPIC-26 is an instrument designed to assess pelvic organ function and bother after PC treatment.11 The study-specific questions were developed after interviews with men living with PC, and were tested for face validity with one investigator accompanying the men while they completed the questionnaire. Questions not fully understood were changed to achieve clarity. The questionnaire was further validated in an unpublished pilot study among men not included in the present study. Our technique for developing a study-specific questionnaire is based on a one-concept–one-question method producing self-reported outcomes and has been previously described.12–14 The questionnaire explored mental symptoms, quality of life and overall satisfaction with care. The questionnaire also assessed experiences at the time of diagnosis and at follow-up, sociodemographics, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, treatments, concurrent diseases (Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)15 and psychiatric problems (obtained by asking if they suffered from depression and/or any other mental illness).

bmjopen-2019-033944supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

Factors potentially associated with choice of and adherence to AS was further evaluated by two direct questions. Choice of AS was evaluated by the question ‘If you were on active surveillance for prostate cancer but later received treatment, or if you are still on active surveillance—which of the following alternative(s) influenced the decision?’. Men had the possibility to grade the following alternatives from ‘I do not agree at all’ to ‘I completely agree’, ‘I am/was not particularly worried about the prostate cancer’, ‘I did not want to risk leaking urine’, ‘I did not want to risk impairing my sexual function’, ‘I did not want to risk getting bowel problems’, ‘I preferred not undergoing any treatment’, ‘I wanted to postpone any treatment until it was deemed necessary’, ‘I felt uneasy about the available treatment strategies (surgery and radiotherapy)’ and ‘My doctor recommended active surveillance’. Adherence was evaluated by the question ‘Why was the active surveillance terminated and treatment initiated?’ with the following alternatives where men had the possibility to choose more than one alternative, ‘The PSA level was rising’, ‘The prostate biopsies showed a more aggressive tumour’, ‘The initiative was mine and had nothing to do with the PSA level or prostate biopsies’ and ‘The initiative was my doctor’s and had nothing to do with the PSA level or prostate biopsies’.

Patient and public involvement statement

Men living with PC where involved in the study early on as we conducted individual interviews with a small number of respondents to explore their perspectives on living with PC. The study-specific questions were developed after these interviews. However, men with PC were not involved in the conduct, analysis of data or writing the manuscript in other ways.

Data availability statement

No additional data available.

Data collection, analysis and statistical analysis

The questionnaires and cancer characteristics data from the NPCR were assembled in a database. Differences between responders and non-responders were analysed. To assess factors associated with the initial choice of treatment, men were grouped by their initial treatment: curative or AS. To assess factors associated with adherence to AS, responders where grouped by whether they stayed on AS or diverged to treatment. Statements such as ‘substantial information’ were defined as the highest possible response to that specific question.

Missing data were handled using multiple imputations based on the method of chained equations.16 Five imputation data sets were created. The maximum number of imputed answers was 4%.

The analysis of factors associated with choice and adherence to AS was carried out using logistic regression. A multivariate analysis was performed including age, retirement, education and CCI and it is these values that are presented. ORs with 95% CI show the probability of choosing and adhering to AS.

Results

Patient characteristics

In all, 1288 (75%) of the 1720 invited men responded. Mean age at diagnosis was 63 years old (range 40–70) (table 1A).

Table 1A.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and potential factors associated with the choice of treatment by treatment group

| Choice | AS | RP/RT | All |

| n | 451 (100.0) | 837 (100.0) | 1288 (100.0) |

| Age, n (range) | 64 (61–67) | 62 (58–65) | 63 (59–66) |

| Marital status n (%) | |||

| Married or domestic partner | 367 (81.4) | 701 (83.8) | 1068 (82.9) |

| Other | 73 (16.2) | 126 (15.1) | 199 (15.5) |

| Missing | 11 (2.4) | 10 (1.2) | 21 (1.6) |

| Children n (%) | |||

| No children | 36 (8.0) | 70 (8.4) | 106 (8.2) |

| Children | 401 (88.9) | 747 (89.2) | 1148 (89.1) |

| Missing | 14 (3.1) | 20 (2.4) | 34 (2.6) |

| Work status, n (%) | |||

| Not retired | 74 (16.4) | 211 (25.2) | 285 (22.1) |

| Retired | 377 (83.6) | 626 (74.8) | 1003 (77.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Compulsory school | 143 (31.7) | 208 (24.9) | 351 (27.3) |

| Secondary school | 166 (36.8) | 347 (41.5) | 513 (39.8) |

| University | 128 (28.4) | 265 (31.7) | 393 (30.5) |

| Missing | 14 (3.1) | 17 (2.0) | 31 (2.4) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 129 (28.6) | 282 (33.7) | 411 (31.9) |

| 1 | 142 (31.5) | 296 (35.4) | 438 (34.0) |

| 2 | 85 (18.8) | 144 (17.2) | 229 (17.8) |

| >2 | 95 (21.1) | 115 (13.7) | 210 (16.3) |

| Psychiatric illness, n (%) | |||

| No | 411 (91.1) | 770 (92.0) | 1181 (91.7) |

| Yes (depression/other) | 40 (8.9) | 67 (8.0) | 107 (8.3) |

| T-stage | |||

| T1ab | 37 (8.2) | 16 (1.9) | 53 (4.1) |

| T1c | 354 (78.5) | 599 (71.6) | 953 (74.0) |

| T2 | 60 (13.3) | 222 (26.5) | 282 (21.9) |

| PSA value at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| 0–3.0 | 31 (6.9) | 41 (4.9) | 72 (5.6) |

| 3.1–7.0 | 325 (72.1) | 597 (71.3) | 922 (71.6) |

| 7.1–10.0 | 95 (21.1) | 199 (23.8) | 294 (22.8) |

| Method of detection n (%) | |||

| Screening | 228 (50.6) | 481 (57.5) | 709 (55.0) |

| LUTS | 162 (5.7) | 216 (25.8) | 377 (29.3) |

| Other symptoms | 51 (11.3) | 109 (13.0) | 160 (12.4) |

| Missing | 11 (2.4) | 31 (3.7) | 42 (3.3) |

| Alone when being notified of the cancer diagnosis n (%) | |||

| No | 107 (23.7) | 256 (30.6) | 363 (28.2) |

| Yes | 332 (73.6) | 568 (67.9) | 900 (69.9) |

| Missing | 12 (2.7) | 13 (1.6) | 25 (1.9) |

| Sufficient time from diagnosis until treatment decision, n (%) | |||

| No, i wanted a quicker decision | 27 (6.0) | 48 (5.7) | 75 (5.8) |

| Yes | 363 (80.5) | 739 (88.3) | 1102 (85.6) |

| No, i wanted more time to think | 11 (2.4) | 35 (4.2) | 46 (3.6) |

| Missing | 50 (11.1) | 15 (1.8) | 65 (5.0) |

AS, active surveillance; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RP/RT, radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

Non-responders were on average 1 year younger, had lower T-stage and lower PSA, were more likely to be diagnosed after PSA-testing and were more likely to be initially managed with AS (data from the NPCR) (online supplementary appendix 2).

bmjopen-2019-033944supp002.pdf (61.9KB, pdf)

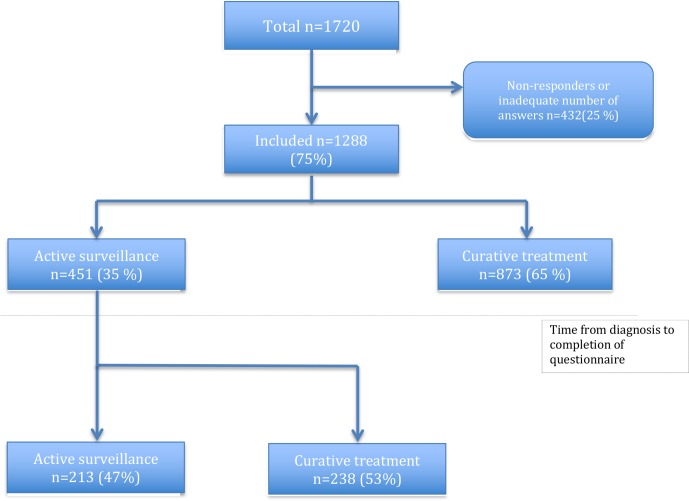

A total of 451 (35%) chose AS and 837 (65%) underwent immediate treatment. Of the men who initially chose AS, 238 (53%) diverted to treatment within 7 years, of whom 70% did so within the first 3 years (table 1B and figure 1). PCs comprised 3% T1a, 1% T1b, 74% T1c and 22% T2 tumours.

Table 1B.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and potential factors associated with adherence to active surveillance by treatment group. AS to radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. numbers are frequencies with percentages in brackets unless otherwise stated.

| Adherence | AS->AS | AS ->RP/RT | All |

| 213 (100.0) | 238 (100.0) | 451 (100.0) | |

| Age, n (range) | 65 (61–68) | 64 (61–66) | 64 (61–67) |

| Marital status n (%) | |||

| Married or domestic partner | 174 (81.7) | 193 (81.1) | 367 (81.4) |

| Other | 35 (16.4) | 38 (16.0) | 73 (16.2) |

| Missing | 4 (1.9) | 7 (2.9) | 11 (2.4) |

| Children n (%) | |||

| No children | 20 (9.4) | 16 (6.7) | 36 (8.0) |

| Children | 186 (87.3) | 215 (90.3) | 401 (88.9) |

| Missing | 7 (3.3) | 7 (2.9) | 14 (3.1) |

| Work status, n (%) | |||

| Not retired | 33 (15.5) | 41 (17.2) | 74 (16.4) |

| Retired | 180 (84.5) | 197 (82.8) | 377 (83.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Compulsory school | 65 (30.5) | 78 (32.8) | 143 (31.7) |

| Secondary school | 78 (36.6) | 88 (37.0) | 166 (36.8) |

| University | 64 (30.0) | 64 (26.9) | 128 (28.4) |

| Missing | 6 (2.8) | 8 (3.4) | 14 (3.1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 56 (26.3) | 73 (30.7) | 129 (28.6) |

| 1 | 70 (32.9) | 72 (30.3) | 142 (31.5) |

| 2 | 36 (16.9) | 49 (20.6) | 85 (18.8) |

| >2 | 51 (23.9) | 44 (18.5) | 95 (21.1) |

| Psychiatric illness, n (%) | |||

| No | 189 (88.7) | 222 (93.3) | 411 (91.1) |

| Yes (depression/other) | 24 (11.3) | 16 (6.7) | 40 (8.9) |

| T-stage | |||

| T1ab | 26 (12.2) | 11 (4.6) | 37 (8.2) |

| T1c | 156 (73.2) | 198 (83.2) | 354 (78.5) |

| T2 | 31 (14.6) | 29 (12.2) | 60 (13.3) |

| PSA value at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| 0–3.0 | 23 (10.8) | 8 (3.4) | 31 (6.9) |

| 3.1–7.0 | 151 (70.9) | 174 (73.1) | 325 (72.1) |

| 7.1–10.0 | 39 (18.3) | 56 (23.5) | 95 (21.1) |

| Method of detection n (%) | |||

| Screening | 94 (44.1) | 134 (56.3) | 228 (50.6) |

| LUTS | 89 (41.8) | 72 (30.3) | 161 (35.7) |

| Other symptoms | 22 (10.3) | 29 (12.2) | 51 (11.3) |

| Missing | 8 (3.8) | 3 (1.3) | 11 (2.4) |

| Alone when being notified of the cancer diagnosis n (%) | |||

| No | 44 (20.7) | 63 (26.5) | 107 (23.7) |

| Yes | 164 (77.0) | 168 (70.6) | 332 (73.6) |

| Missing | 5 (2.3) | 7 (2.9) | 12 (2.7) |

| Sufficient time from diagnosis until treatment decision, n (%) | |||

| No, i wanted a quicker decision | 9 (4.2) | 18 (7.6) | 27 (6.0) |

| Yes | 152 (71.4) | 211 (88.7) | 363 (80.5) |

| No, i wanted more time to think | 5 (2.3) | 6 (2.5) | 11 (2.4) |

| Missing | 47 (22.1) | 3 (1.3) | 50 (11.1) |

AS, active surveillance; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RP/RT, radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing patients participation and treatment.

The vast majority of men primarily consulted either a urologist or a clinical oncologist, 18% consulted both a urologist and a clinical oncologist.

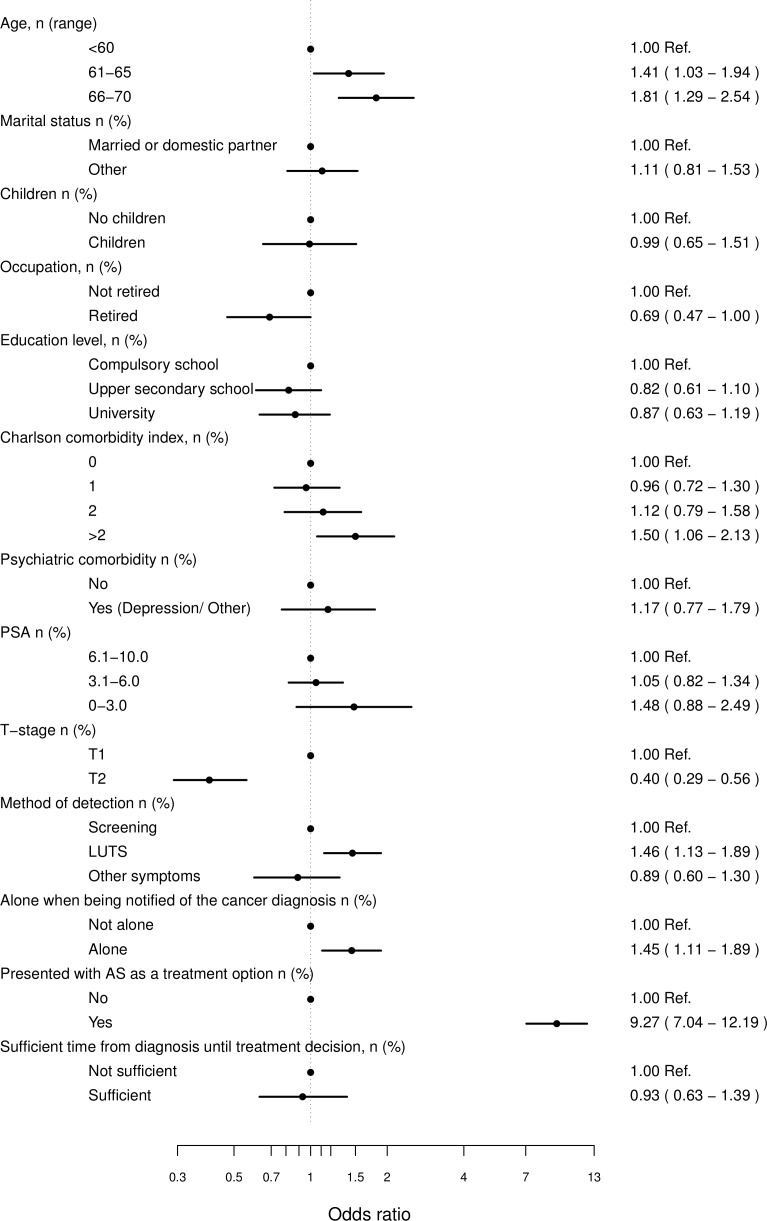

Factors associated with choice

Factors statistically associated with choosing AS over treatment included older age (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.54 for men aged <60 years vs men aged 66–70 years), a CCI >2 (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.13, compared with CCI 0), unaccompanied when being notified of the diagnosis (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.89) and being presented with AS by the treating physician (OR 9.27, 95% CI 7.04 to 12.19). Factors statistically associated with not choosing AS over treatment included whether men were still working (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.00) and/or had a T2 tumour (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.56) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forrest plot illustrating choice. OR shows the probability of choosing AS as primary treatment. An OR above one favour AS. Adjusted for age, work status, education and Charlson Comorbidity Index. AS, active surveillance; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

PSA at diagnosis (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.13), time to reflect on treatment options (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.39) and whether the men had seen both a urologist and a clinical oncologist (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.53) were not statistically significantly associated with choice.

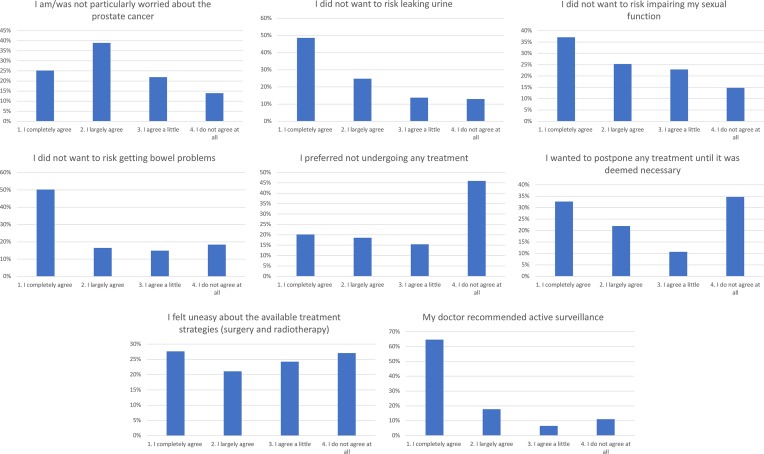

Regarding the direct questions on why the men chose AS (figure 3) (defined as completely or largely agreed).

Figure 3.

Bar chart illustrating the direct question on why men chose active surveillance as their primary treatment. Numbers are frequencies with percentages.

83% ‘My doctor recommended AS’.

74% ‘I did not want to risk leaking urine’.

66% ‘I did not want to risk getting bowel problems’

64% ‘I am/was not particularly worried about the prostate cancer’.

62% ‘I did not want to risk impairing my sexual function’.

55% ‘I wanted to postpone any treatment until it was deemed necessary’.

49% ‘I felt uneasy about the available treatment strategies (surgery and radiotherapy)’.

39% ‘I preferred not undergoing any treatment’.

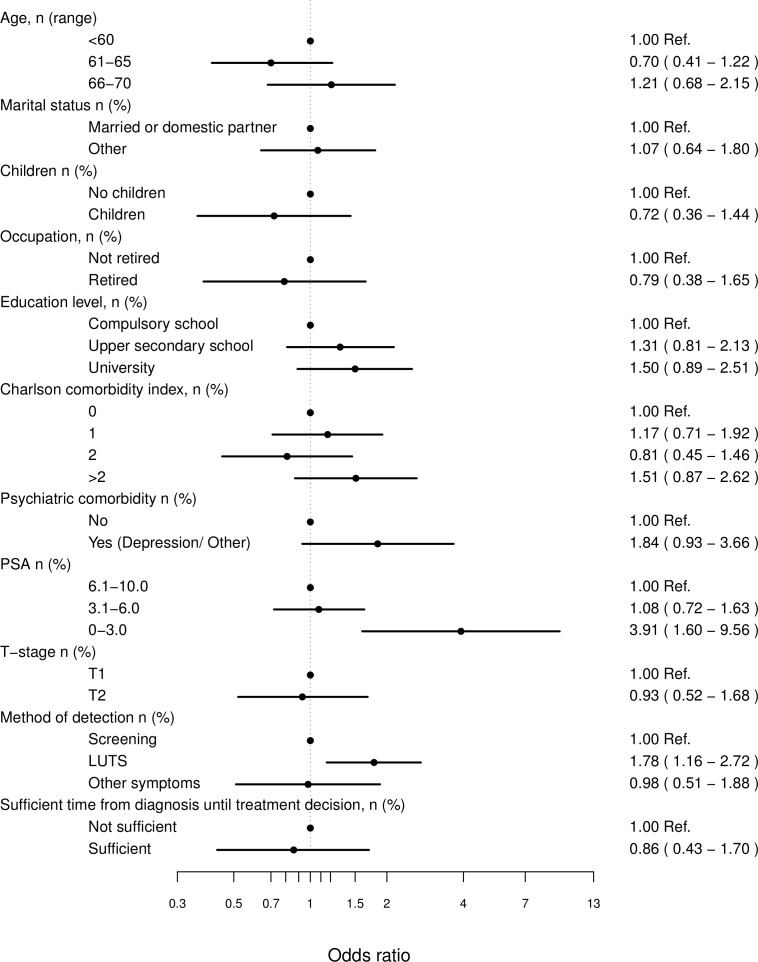

Factors associated with adherence

Men with PC detected during the investigation of lower urinary tract symptoms(LUTS) rather than screening was associated with adhering to AS (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.72). Men with a higher PSA at the time of diagnosis (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.63) were less likely to adhere to AS (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forrest plot illustrating adherence. OR shows the probability of adhering to active surveillance. An OR above one favour adhering to AS. Adjusted for age, work status, education and Charlson Comorbidity Index. AS, active surveillance; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

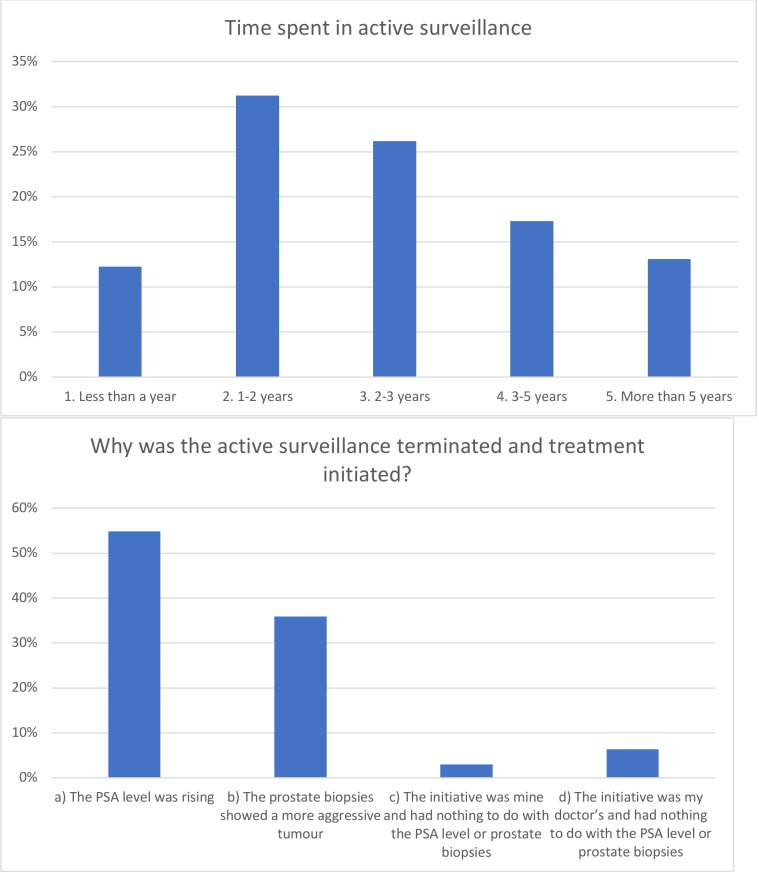

Regarding the direct question on reasons for diverting to treatment (figure 5), (defined as completely or largely agreed).

Figure 5.

Bar chart illustrating the direct question on time spent in active surveillance and why men terminated active surveillance. Numbers are frequencies with percentages. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

55% ‘the PSA level was rising’.

36% ‘the prostate biopsies showed a more aggressive tumour’.

6% ‘the initiative was my doctor’s and had nothing to do with the PSA level or prostate biopsies’.

3% ‘the initiative was mine and had nothing to do with the PSA level or prostate biopsies’.

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based study, a doctor’s recommendation was a strong predictor for choosing AS, as was patient characteristics such as older age and more concurrent diseases. Men without anyone accompanying them when they were notified of the cancer diagnosis were more likely to opt for AS. Regarding adherence to AS, a low PSA at the time of diagnosis was an important factor, both according to the multivariate analysis and the direct question. Further, men whose PC was detected during the investigation of LUTS were more likely to adhere to AS. A unique feature of our study is that we could quantify the relative importance of different potential reasons for choosing and adhering to AS, as the men could tick more than one reason and grade its importance.

A doctor’s recommendation emerged as strongest factor associated with choice. This is highlighted in our direct question on choice where a doctor’s recommendation was the single strongest predictor for choosing AS with 83% stating that they chose AS because their doctor recommended it. In fact, more men specified a doctor’s recommendation as a reason for choosing AS than the will to avoid side effects from treatment. This is in line with the review article about factors influencing men’s choice of and adherence to AS by Kinsella et al,9 in which a physician’s recommendation was identified as an important element in choosing AS.17–20 In light of the evidence from multiple studies for the importance of the physician’s recommendation in favour for choosing AS, the most important cause of the rapid increase in uptake on AS in Sweden over the past decade,3 was probably the Swedish national guidelines’ clear recommendation since 2007 of AS for men with low-risk PC. The recommendation was during this time period less clear in the European and US recommendations,21 22 in which AS was mentioned as an alternative to radical treatment rather than the first choice option.

That patient characteristics, such as a higher age, were associated with AS is in line with previous studies.18 23 It is possible that some of these men might have diverted from AS to watchful waiting during the 7 years of follow-up as the oldest had reached 77 years by 2015 and might not have been eligible for treatment.

On multivariate analysis, being unaccompanied when notified of the cancer diagnosis predicted choice of AS. This might reflect that these men are more prone to accept the physician’s suggestion if no one else was influencing them to undergo treatment. This highlights the responsibility of the treating physician, not only directed towards the patients but also to their significant others, to facilitate an informed treatment decision. A recently published qualitative study by Mader et al stating that spousal and social support play important roles in helping men understand and accept their PC diagnosis and chosen care plan.24 In our study, 18% of men saw both a urologist and a clinical oncologist but this did not affect the choice of treatment.

The participants in our study were diagnosed in 2008. Since then, uptake on AS in Sweden has steadily increased and reached 74% by 2014.3 In our study, 35% initially chose AS and 47% were still on AS after 7 years follow-up. This is in line with a study by Loeb et al from 2015 that reported 64% adherence to AS after 5 years25 as well as the PRIAS study where 50% diverted to treatment within 5 years, mostly due to protocol-based reclassification (biopsy related, changes in T-stage and/or PSA-doubling time).26

The main patient reported driver behind diverting to treatment was a rise in PSA. Only 9% of the men stated that the decision to diverge from AS to treatment was not because of PSA and/or biopsy results. PSA is considered a poor marker for disease progression, which for example was shown by Fall et al when looking at men with high-risk disease.27 Several studies have shown that many men with low-risk PC overestimate the risk of living with an untreated cancer,28 29 something that might be further magnified by rising PSA. In the Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) study, no difference in mortality was detected between men who were randomised to radical prostatectomy or observation after nearly 20 years of follow-up.30 Roughly half of the men in our study, who all had low-risk PC diverted to treatment within these 7 years that represents a significant overtreatment. Adherence to AS protocols and additional methods for follow-up such as MRI31 and evidence-based triggers for treatment might reduce the fear of living with untreated cancer and thereby reduce unnecessary treatment.

Interestingly, men whose PC was detected during the investigation of LUTS rather than through screening was more likely to adhere to AS. This finding persisted after adjusting for age, retirement and CCI. A possible explanation might be a higher degree of anxiety in the group whose PC was detected through screening rather through the investigation on LUTS, although we do not have any data to support this. A recently published review article on psychological distress during the cancer screening32 indicated that psychological distress, although low and not a barrier to screening, might be present. There might also be a motivational difference where men diagnosed through screening actively sought the investigation of PC and might be more motivated to undergo treatment. Another possible explanation might be that men diagnosed through the investigation of LUTS might have received drugs that reduce PSA, for example, Finasteride.

The strengths of our study include its population-based design, the high response rate for a study of its kind, the face-validated study-specific questionnaire and the direct questions on reasons for choice and adherence. We acknowledge that various selection mechanisms affected the men’s choice of treatment and that several important factors could have been missed. The retrospective design is a limitation, as the men’s experiences during the 7 years follow-up might have affected their recollection of their experiences. We did not have access to PSA levels during AS, only at diagnosis, which limits the possibility to investigate how PSA monitoring affects adherence to AS. Regarding being unaccompanied when notified of the cancer diagnosis, it is important to acknowledge that while these where unaccompanied during the appointment, they still might have had support from people in their support network. The study included Swedish men only and the findings might, therefore, not be generalisable to other cultural and healthcare settings.

Conclusions

A doctor’s recommendation strongly affects which treatment is chosen for men with low-risk PC. Rising PSA values were the main factor for initiating treatment for men on AS. These findings need to be considered by healthcare providers who wish to increase the uptake of and adherence to AS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ellen Kragsterman for her excellent help with data collection during this study. We also wish to thank all of the men who answered the questionnaire.

Footnotes

Twitter: @BergengrenOskar

Contributors: OsB had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: OsB, HG, OlB, EJ and AB-A. Acquisition of data: OsB, EJ and AB-A. Analysis and interpretation of data: OsB, HG, LH, EJ and AB-A. Drafting of the manuscript: OsB, EJ and AB-A. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: OsB, OlB, LH, EJ and AB-A. Statistical analysis: HG. Obtaining funding: AB-A. Administrative, technical or material support: AB-A. Supervision: LH, EJ and AB-A.

Funding: This research was funded by grants from the Swedish cancer society.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board at Uppsala University approved of the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Cooperberg MR. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate Cancer-An evolving international standard of care. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1398–9. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990-2013. JAMA 2015;314:80–2. 10.1001/jama.2015.6036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Curnyn C, et al. Uptake of active surveillance for Very-Low-Risk prostate cancer in Sweden. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1393–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auffenberg GB, Lane BR, Linsell S, et al. Practice- vs Physician-Level variation in use of active surveillance for men with low-risk prostate cancer: implications for collaborative quality improvement. JAMA Surg 2017;152:978–80. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kinsella N, Helleman J, Bruinsma S, et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of contemporary worldwide practices. Transl Androl Urol 2018;7:83–97. 10.21037/tau.2017.12.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitsuzuka K, Koga H, Sugimoto M, et al. Current use of active surveillance for localized prostate cancer: a nationwide survey in Japan. Int J Urol 2015;22:754–9. 10.1111/iju.12813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bul M, Zhu X, Valdagni R, et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer worldwide: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol 2013;63:597–603. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tosoian JJ, Mamawala M, Epstein JI, et al. Intermediate and longer-term outcomes from a prospective Active-Surveillance program for Favorable-Risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3379–85. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.5764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kinsella N, Stattin P, Cahill D, et al. Factors influencing men's choice of and adherence to active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: a mixed-method systematic review. Eur Urol 2018;74:261–80. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. Cohort profile: the National prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:956–67. 10.1093/ije/dys068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899–905. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00858-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johansson E, Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, et al. Time, symptom burden, androgen deprivation, and self-assessed quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the randomized Scandinavian prostate cancer Group study number 4 (SPCG-4) clinical trial. Eur Urol 2009;55:422–32. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med 2002;347:790–6. 10.1056/NEJMoa021483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1175–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa040366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buuren Svan. Flexible imputation of missing data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davison BJ, Breckon E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information preferences of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ Couns 2012;87:369–74. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoffman KE, Niu J, Shen Y, et al. Physician variation in management of low-risk prostate cancer: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1450–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorin MA, Soloway CT, Eldefrawy A, et al. Factors that influence patient enrollment in active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Urology 2011;77:588–91. 10.1016/j.urology.2010.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scherr KA, Fagerlin A, Hofer T, et al. Physician recommendations Trump patient preferences in prostate cancer treatment decisions. Med Decis Making 2017;37:56–69. 10.1177/0272989X16662841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ganz PA, Barry JM, Burke W, et al. National Institutes of health State-of-the-Science conference: role of active surveillance in the management of men with localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:591–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol 2011;59:61–71. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maurice MJ, Abouassaly R, Kim SP, et al. Contemporary nationwide patterns of active surveillance use for prostate cancer. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1569–71. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mader EM, Li HH, Lyons KD, et al. Qualitative insights into how men with low-risk prostate cancer choosing active surveillance negotiate stress and uncertainty. BMC Urol 2017;17:35 10.1186/s12894-017-0225-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Makarov DV, et al. Five-Year nationwide follow-up study of active surveillance for prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015;67:233–8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bokhorst LP, Valdagni R, Rannikko A, et al. A decade of active surveillance in the PRIAS study: an update and evaluation of the criteria used to recommend a switch to active treatment. Eur Urol 2016;70:954–60. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fall K, Garmo H, Andrén O, et al. Prostate-Specific antigen levels as a predictor of lethal prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:526–32. 10.1093/jnci/djk110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu J, Janisse J, Ruterbusch JJ, et al. Patients' survival expectations with and without their chosen treatment for prostate cancer. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:208–14. 10.1370/afm.1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kendel F, Helbig L, Neumann K, et al. Patients' perceptions of mortality risk for localized prostate cancer vary markedly depending on their treatment strategy. Int J Cancer 2016;139:749–53. 10.1002/ijc.30123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-Up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:132–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Litwin MS, Tan H-J. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: a review. JAMA 2017;317:2532–42. 10.1001/jama.2017.7248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chad-Friedman E, Coleman S, Traeger LN, et al. Psychological distress associated with cancer screening: a systematic review. Cancer 2017;123:3882–94. 10.1002/cncr.30904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033944supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033944supp002.pdf (61.9KB, pdf)