Abstract

Background:

Mechanisms of metabolic improvement after bariatric surgery remain incompletely understood. Intestinal glucose uptake is increased after gastric bypass in rodents, potentially contributing to reduced blood glucose and type 2 diabetes remission.

Objective:

We assessed whether intestinal glucose uptake is increased in humans after gastric surgery.

Setting:

University Hospital, United States.

Methods:

In a retrospective, case-control cohort study, positron emission tomography-computerized tomography scans performed for clinical indications were analyzed to quantify intestinal glucose uptake in patients with or without history of gastric surgery. We identified 19 cases, defined as patients over age 18 with prior gastric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [n = 10], sleeve gastrectomy [n = 1], or Billroth I [n = 2] or II gastrectomy [n = 6]), and 43 controls without gastric surgery, matched for age, sex, and indication for positron emission tomography-computerized tomography. Individuals with gastrointestinal malignancy or metformin treatment were excluded. Images were obtained 60 minutes after 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose injection (4.2 MBq/kg), and corrected by attenuation; noncontrast low-dose computerized tomography was obtained in parallel. Fused and nonfused images were analyzed; standardized uptake values were calculated for each region by volumes of interest at the region of highest activity.

Results:

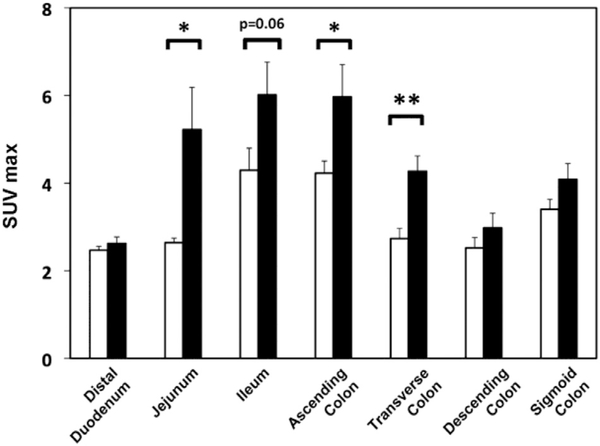

Both standardized uptake values maximum and mean were significantly increased by 41% to 98% in jejunum, ascending, and transverse colon in patients with prior gastric surgery (P < .05 versus controls).

Conclusion:

Intestinal glucose uptake is increased in patients with prior gastric surgery. Prospective studies are important to dissect the contributions of weight loss, dietary factors, and systemic metabolism, and to determine the relationship with increased insulin-independent glucose uptake and reductions in glycemia. (Surg Obes Relat Dis 2019;000:1–7.) © 2019 American Society for Bariatric Surgery. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Intestinal glucose uptake, 18D-FDG PET-CT, Gastrointestinal surgery, Glucose metabolism, Intestine

Bariatric surgery yields not only robust weight loss but also marked improvements in glucose metabolism [1–3] with reduced plasma glucose, remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D), and lowering of glucose to below-normal levels in a subset of individuals with postbariatric hypoglycemia [4,5] . Potential mechanisms engaged by bariatric and other upper gastrointestinal surgical procedures include accelerated gastric emptying, alterations in bile acid metabolism and enterohepatic recirculation, changes in the intestinal microbiome [6], and increased incretin secretion (e.g., glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), others) by intestinal neuroendocrine cells. Postprandial insulin concentrations are increased after gastric bypass surgery, largely reflecting increased incretin-dependent insulin secretion [7]. Moreover, insulin-independent glucose uptake is increased in postbariatric hypoglycemia [8]. Collectively, these data underscore the important role of the gastrointestinal tract in controlling whole-body metabolism via both insulin-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

The intestine is not only capable of glucose uptake, but is also insulin-responsive in healthy humans; glucose uptake is increased by > 2-fold in duodenum and jejunum during euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamps. By contrast, insulin fails to increase intestinal glucose uptake in obese individuals, despite similar basal glucose uptake [9]. At a cellular level, insulin resistant enterocytes fail to inhibit gluconeogenesis and glucose release from both apical and basolateral surfaces, resulting in decreased net glucose uptake. Given the large mass of the intestine, reduced intestinal glucose uptake may impact whole-body metabolism; reductions in intestinal glucose uptake closely parallel whole-body insulin resistance in obesity [9].

In obese patients with T2D, whole-body glucose uptake progressively increases after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [10], with major contributions from skeletal muscle and heart. However, the tissue source of up to 51% of the increase in glucose uptake after bariatric surgery remains undefined. Intestinal glucose uptake is increased after RYGB surgery in rodents [11]. We hypothesized that similar patterns of increased intestinal glucose uptake are present in humans with prior gastric surgery, as recently shown after gastric resection for cancer [12]. To test this hypothesis, we performed a retrospective case-control analysis to determine whether intestinal glucose uptake (assessed using fluorodeoxyglucose, [FDG] for positron emission tomography-computerized tomography [PET-CT]) differs in individuals with or without prior gastric or bariatric surgery, and if present, to localize the anatomic regions with altered intestinal glucose uptake.

Methods

Selection of patients

The institutional nuclear medicine database was searched to identify patients with and without a history of gastric surgery. Search was by performed by using the terms “gastric bypass” (V45.86), “sleeve gastrectomy” (V45.86), and “Billroth gastrectomy” (V15.29). Selected individuals were de-identified and assigned a random number.

From a total of 18,264 PET-CT scans performed for clinical indications between November 2004 and December 2014, we identified 19 patients over age 18 with prior history of gastric surgery, including RYGB (n = 10), sleeve gastrectomy (n = 1), or gastrectomy (unspecified, n = 4; Billroth I, n = 2, or Billroth II, n = 2). Forty-three controls with no history of gastric surgery were identified in parallel and were matched by age (within 5 years), sex, presence of diabetes at time of scanning, indication for PET-CT, year of scan, and diet protocol. For each surgical patient, 1 to 3 controls were identified. Patients with known gastrointestinal malignancy (from stomach to sigmoid colon) were excluded, as tumor uptake of FDG could interfere with accurate determination of intestinal glucose uptake. Similarly, individuals taking metformin were excluded from the study, as metformin was previously reported to increase intestinal glucose uptake [13].

The study was approved by the institutional review board.

PET-CT

PET-CT scans were performed using an integrated PET-CT GE Health Care (Chicago, IL) Discovery Light Speed (before November 2014; 56 patients) and Siemens (Er-langer, Germany) Biograph mCT (after November 2014; 6 patients).

As per clinical protocol in our institution, patients were instructed to consume a high-fat, no-carbohydrate, protein-containing meal and then to fast for 3 to 5 hours before the PET/CT to decrease myocardial and brown fat activity (n = 59); 3 individuals (1 surgical, 2 controls) were imaged in the fasting state, without dietary preparation (before August 2006, when specific dietary instructions were initiated). Blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (Precision XceedPro; Abbott, Alameda, CA); if < 200 mg/dL, 18F-FDG (mCi = 0.114 × weight in kg) was injected. Patients remained in a semireclining chair for 45 to 60 minutes at room temperature, and were asked to urinate immediately before scanning. Surgical and control groups were balanced for equipment and preparation protocol employed.

PET-CT scans were routinely performed from the base of the skull to the midthigh; whole-body scans were performed if lesions were suspected in other areas or for patients with melanoma. The CT component of the study was performed first, without contrast and using the following low-dose parameters: 35 mA, 140 KeV, 4-mm slice thickness. PET images were acquired in a craniocau-dal direction, using 3-dimensional acquisition mode, 5-mm thickness, 3-min/bed position. PET images were corrected for attenuation and displayed using dedicated software (Syngo.via; Siemens).

Data analysis

Two investigators analyzed images independently, initially blinded to group and indication, although postsurgical anatomic changes were visible. PET and CT images were analyzed in parallel, permitting identification of specific bowel regions and postsurgical anatomy. Both images were reviewed in axial and multiplanar reformatted sagittal and coronal planes. Use of cross-reference tools on the imaging software allowed confident localization of specific intestinal segments, based on anatomic localization and appearance of the loops. Presence of brown fat activity was assessed qualitatively.

Quantitative analysis

18F-FDG uptake was semiquantitatively analyzed by determining maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) in the small and large intestine, with the following segments identified by anatomic characteristics and landmarks: third portion of the duodenum, proximal jejunum, distal ileum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid. In the nonsurgical group, jejunum could not be anatomically discriminated from proximal ileum, so analysis of these 2 structures was limited by upper and inferior quadrants. In the surgical group, the presence of surgical material in the anastomosis helped to delimit the proximal jejunum.

Quantification was performed by selecting the area with highest 18F-FDG activity within each segment visually and windowing the PET images, reducing the background activity to allow identification of the highest point of uptake in each segment. All of the measurements were calculated in 3-dimensional volumes of interest (VOIs). VOI spheres were manually placed and drawn for each intestinal segment. Inside each sphere only intestinal activity was considered for quantification, using a contouring tool delimiting the intestine (“isocontours,” Supplementary Fig. 1). VOIs differed across segments due to differences in width and the need to exclude nearby structures. VOIs included intestinal walls and possible luminal content but not ex-traintestinal content. For each VOI, both SUVmax and mean were obtained. To ensure that the SUVmax was not due to a single pixel, SUVmean (average of uptake among the included pixels) of the area quantified for SUVmax was also recorded. Single “hot spots” were not included in quantification. SUV mean was also measured in a fixed 1-cm3 sphere VOI in both cerebellum (hemisphere) and liver (right lobe) as an internal reference of glucose metabolism for each subject.

Statistics

Between-group comparisons were analyzed using unpaired, 2-tailed, Student’s t test (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), with P < .05 considered significant.

Results

Demographic information is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Mean age (65 ± 11 yr) did not differ between groups. Mean body mass index (BMI) did not differ between individuals with history of gastric surgery versus controls (29.4 ± 8.6 versus 27.5 ± 8.1). Ten individuals (6 control, 4 gastric surgery) had a history of T2D; none were on metformin [13,14]. Capillary glucose at the time of tracer injection did not differ between surgical and control groups (109 ± 21 versus 113 ± 18 mg/dL). Postsurgical duration was available for 16 of 22 patients; median was 13 years (range, .5–40 yr). Indications for scanning included lung cancer (28), anal cancer (3), melanoma (6), breast cancer (10), gynecologic cancer (3), head and neck cancer (4), lymphoma (2), and others (5); in accord with matching strategy, indications did not differ between groups. PET/CT scans were positive for malignancy in 35 (10 surgical, 25 controls) and negative in 26 (9 surgical, 17 controls). One PET/CT in the control group was positive for vasculitis of the great vessels. Seventeen of 62 PET/CTs were performed during chemotherapy (2 surgical, 15 controls).

Image analysis of cerebellum and liver revealed that SUVmean did not differ between groups in these tissues (Supplementary Fig. 2). No uptake suggestive of brown adipose tissue was observed in the neck or upper thoracic region.

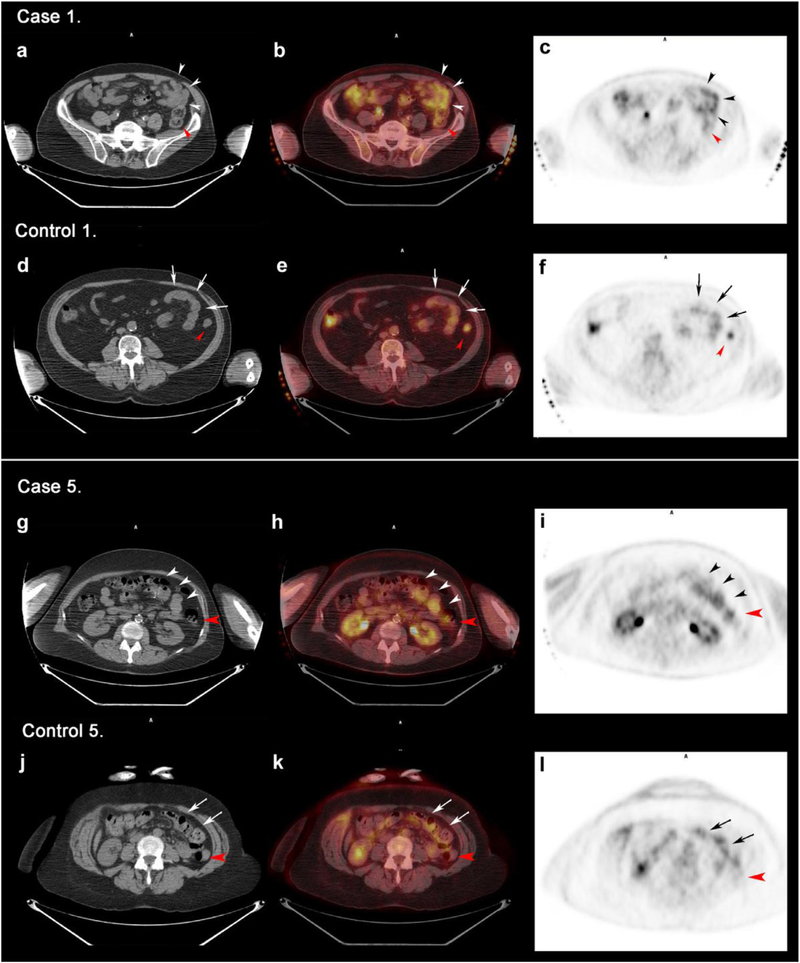

Specific intestinal segments were identified by parallel analysis of CT images. SUVmax did not differ for duodenum, descending or sigmoid colon (Fig. 1). However, SUVmax was greater (P < .05) in the gastric surgical group for jejunum (98% higher, representative scans, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), ascending colon (41% higher), and transverse colon (56% higher), with similar trend for increased SUVmax in ileum (P = .06). In some postsurgical patients, the Roux limb was specifically identified, and uptake was increased (Fig. 2, arrowheads). Similar patterns were observed for SUVmean, with significant increase in jejunum (P < .01), ascending colon (P < .05), and transverse colon (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 2). SUV in jejunum or ascending colon did not correlate with current BMI. Interobserver correlation for SUV measurements was .96.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative comparison of standard uptake value maximum (SUVmax) in intestinal segments. White column represents control group and black solid column represents postsurgical patients. *P < .05, **P < .01 for postsurgical patients versus controls.

Fig. 2.

Jejunal limb uptake in representative matched surgical cases and controls. Computed tomography (CT), fused positron emission tomography (PET/CT), and positron emission tomography (PET) images are displayed from left to right. Cases and controls are matched by age, sex, indication, presence of type 2 diabetes, diet protocol, and time period of scan. Distal segment of the jejunal limb of the surgical patients or normal jejunum in control patients are shown with black and white arrowheads. Red arrowheads indicate ascending colon. (A–F) Postsurgical case 1 (A–C) and matched control 1 (D–F). (A–C) restaging PET/CT axial slices of an 80-year-old male with nonsmall cell lung cancer status postgastric bypass show moderately increased uptake in the jejunal limb with 4.78 SUVmax and 2.87 standard uptake value mean (SUVmean). (D–F) Staging PET/CT axial slices from a 78-year-old male with nonsmall cell lung cancer shows a less glucose-avid jejunum (SUVmax 3, SUV mean 1.73). (G–L) Postsurgical case 5 (G–I) and matched control 5 (J–L). Staging PET/CT axial slices of a 55-year-old female with melanoma status postRYGB and (J–L) restaging PET/CT axial slices of a 61-year-old female with melanoma. Postsurgical patient presents a much higher jejunal glucose activity (SUVmax 3.66, SUVmean 2.4) in comparison to matched control (SUV max 2.72, SUVmean 1.55).

Patterns were similar for the subgroup of individuals without diabetes, with significant increases in SUVmax for jejunum (59% increase, P = .007) and transverse colon (62% increase, P = .002) and trend for ascending colon (P = .06). Restriction of analysis to those individuals with gastric bypass performed for obesity also revealed significant increases in SUVmax in transverse colon (34% increase, P = .03) and trend for increased jejunal uptake (2.2-fold, P = .1). Patterns remained similar when considering data from males or females only, old versus new scanner, and differing preprocedure protocols.

Discussion

Emerging evidence indicates the intestine itself may be a major contributor to increased systemic glucose uptake and improved whole-body metabolism after upper gastrointestinal and bariatric surgery. We now report that intestinal glucose uptake is increased in humans with a history of gastric surgery. Significant increases in glucose uptake (assessed by SUV) were observed in multiple gut segments, including jejunum, ascending colon, and transverse colon, with trend for increases in ileum.

Our data are analogous to patterns observed in post-bypass rodents, in which increased glucose uptake is observed in both the Roux limb and more distal common limb [11]. Similar patterns were observed in a small series of 3 postRYGB humans, in which qualitative increases in Roux limb uptake were observed in comparison with 4 BMI-matched controls [15]. Likewise, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake was increased in the jejunum by 40% at 6 months after either RYGB or sleeve gastrectomy [16]. In a series of postgastrectomy patients, small intestinal SUV was increased by 48% at 12 months postoperatively [12], more commonly after Roux-en-Y procedures. We also observed increased glucose uptake in ascending and transverse colon—patterns similar to those in metformin-treated humans and mice [13,17,18].

During PET-CT scanning, tracer is injected intravenously; thus, increased SUV reflects increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake into intestinal cells from the blood-stream on their basolateral side (not luminal). Previous studies in mice and pigs verified that PET-defined uptake accurately reflects tracer accumulation in tissue and correlates with tissue glucose uptake ex vivo [9]. The majority of tracer uptake is found in the mucosal layer, with less in the submucosa and muscular layer, and no tracer in the lumen [9,19]. Intestinal content, which is more prominent in large intestine, may account for up to 6% to 12% of total gastrointestinal uptake in rodents [19].

While we do not know the specific pathways contributing to increased glucose uptake in humans, expression of the basolateral glucose transporter GLUT1 is increased in the Roux limb and proximal common limb of postRYGB rodents, and GLUT1 inhibition reduces intestinal glucose uptake [11]. Increased intestinal glucose uptake, per gram of tissue, was robust, with magnitude exceeded only in the brain. Moreover, increases in intestinal uptake in postRYGB rodents are similar in nonobese and insulin deficient rats, indicating these patterns are un-likely to result from weight loss per se, and are insulin-independent. Moreover, transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis in both rodents and humans indicate increased glucose metabolism via glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, suggesting proliferative responses could drive increased glucose metabolism or vice versa [20]. One possibility is that intestinal proliferative responses driven in part by the trophic hormone GLP2, could contribute to intestinal hypertrophy [21], as observed in postbariatric rodents [22,23] and humans [22,24] as well as increased blood flow and nutrient uptake, including glucose [25]. We cannot exclude the possibility of differential transit of tracer into the lumen via sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT)-dependent mechanisms [15], altered intestinal permeability, or differential uptake by the intestinal microbiome [26] as contributors to altered patterns of tracer uptake after gastric surgery. Unfortunately, parallel and longitudinal analysis of tissue samples and PET-CT glucose uptake to dissect these relationships in human patients is not feasible.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, we performed a retrospective analysis of PET-CT scans obtained for clinical indication, as scanning in otherwise healthy individuals would expose them to radiation unnecessary for clinical care. However, previous studies have demonstrated intestinal PET-CT FDG uptake is stable across a range of age, fasting conditions, blood glucose levels, and with repeated scanning over time [27]. Second, PET-CT scans were obtained for staging of malignancy; it is possible that patients with malignancy may have unique metabolic profiles (resulting either from the malignancy or chemotherapy), which could perturb intestinal glucose uptake. To minimize the impact of tumor type, we matched for similar tumor type and indications for scanning. Nevertheless, a paired prospective comparison of intestinal glucose uptake in otherwise healthy individuals before and after achievement of stable long-term weight loss after bariatric surgery would be helpful to fully evaluate the impact of surgery. Third, our retrospective study of clinically obtained scans does not allow us to quantitatively determine the contribution of higher intestinal glucose uptake to whole-body glucose metabolism; this would be important for future studies. Fourth, given the retrospective nature of this study, insulin sensitivity and postprandial insulin concentrations were not available.

Our study cohort was heterogeneous, potentially related in part to the small sample size resulting from our matching strategy. For example, a small number of individuals with T2D was included, but representation was equivalent in surgical and control groups. While T2D has been shown to increase diffuse colon FDG uptake [28], similar significant increases in intestinal glucose uptake were observed when patients with diabetes were excluded. Although glucose levels were similar at the time of injection, we do not have data for overall glycemic control in all individuals. Similarly, the study cohort included individuals with several types of gastric surgery; patterns of glucose uptake within the intestine and ascending colon were similar in the dominant RYGB subset compared with the entire postsurgical cohort. However, it is possible that subclinical differences in whole-body metabolic control for individual patients or surgical groups could contribute to distinct patterns of intestinal glucose uptake. Additional complexity likely arises from differences in chronic dietary composition and microbiota between individuals, both of which could potentially modulate tracer uptake [29]. Indeed, treatment with rifaximin to modulate the microbiome has been shown to reduce intestinal FDG uptake [26], suggesting potential interactions between the microbiome and local regulation of glucose uptake.

Conclusion

In summary, we report that intestinal glucose uptake is increased in patients with a remote history of gastric surgery, compared with a matched-control group. Prospective analysis will be required to define relationship between intestinal glucose uptake and resolution of diabetes after gastric surgery, and to define the contributions of weight loss, dietary factors, and systemic metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

EF and MEP designed the study. EF performed database queries to select patients and matched controls. EF and GW analyzed SUV for each intestinal segment. MEP performed comparative analysis of between-group differences in SUV. GMK and ABG assisted with manuscript edits.

Disclosures

EF, GW, and GMK declare no conflicts of interest. MEP acknowledges research grant support for other projects from Medimmune, Nuclea, BMS, and AZ. ABG acknowledges research grant support from the American Diabetes Association, NIDDK, NHLBI (recently completed), and Cleveland Clinic (subcontract, funds derived from Ethicon and Covidien ). ABG is now an employee of Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research.

Footnotes

We gratefully acknowledge support for this project from Fundación Alfonso Martin Escudero (E.F.) and P30 DK036836 (D.R.C., Joslin Diabetes Center).

EF, GW, and GMK declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.soard.2019.01.018.

References

- [1].Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386(9997):964–73 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP for the STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017;376:641–51 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Patients (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013;273(3):219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Service GJ, Thompson GB, Service FJ, Andrews JC, Colla-zo-Clavell ML, Lloyd RV. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with nesidioblastosis after gastric-bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2005;353(3):249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Patti ME, McMohon G, Mun EC, et al. Severe hypoglycaemia postgastric bypass requiring partial pancreatectomy: evidence for inappropriate insulin secretion and pancreatic islet hyperplasia. Diabetologia 2005;48(11):2236–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tremaroli V, Karlsson F, Werling M , et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty induce long-term changes on the human gut microbiome contributing to fat mass regulation. Cell Metab 2015;22(2):228–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goldfine AB, Mun EC, Devine E , et al. Patients with neuroglycopenia after gastric bypass surgery have exaggerated incretin and insulin secretory responses to a mixed meal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92(12):4678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Patti ME, Li P, Goldfine AB . Insulin response to oral stimuli and glucose effectiveness increased in neuroglycopenia following gastric bypass. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(4):798–807 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Honka H, Makien J, Hannukainen JC, et al. Validation of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography (PET) for the measurement of intestinal metabolism in pigs, and evidence of intestinal insulin resistance in patients with morbid obesity. Diabetologia 2013;56(4):893–900 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Morbelli S, Marini C, Adami GF, et al. Tissue specificity in fasting glucose utilization in slightly obese diabetic patients submitted to bariatric surgery. Obesity 2013;21(3):E175–81 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Saeidi N, Meoli L, Nestoridi E, et al. Reprogramming of intestinal glucose metabolism and glycemic control in rats after gastric bypass. Science 2013;341(6144):406–10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ku CR, Lee N, Hong JW, et al. Intestinal glycolysis visualized by FDG PET/CT correlates with glucose decrement after gastrectomy. Diabetes 2017;66:38–91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ozulker T, Ozulker F, Mert M, Ozpacaci T . Clearance of the high intestinal (18)F-FDG uptake associated with metformin after stop-ping the drug. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010;37(5):1011–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, et al. Disentangling the effects of type 2 diabetes and metformin on the human gut microbiota. Nature 2015;528(7581):262–6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cavin JB, Couvelard A, Lebtahi R, et al. Differences in alimentary glucose absorption and intestinal disposal of blood glucose after Rouxen-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy. Gastroenterology 2016;150(2):454–64 e459 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mäkinen J, Hannukainen JC, Karmi A, et al. Obesity-associated intestinal insulin resistance is ameliorated after bariatric surgery. Diabetologia 2015;58(5):1055–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vidal JD . The impact of age on the female reproductive system. Toxicol Pathol 2017;45(1):206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bailey CJ, Mynett KJ, Page T . Importance of the intestine as a site of metformin-stimulated glucose utilization. Br J Pharmacol 1994;112(2):671–5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Massollo M, Marini C, Brignone M, et al. Metformin temporal and localized effects on gut glucose metabolism assessed using 18F-FDG PET in mice. J Nuclear Med 2013;54(2):259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ben-Zvi D, Meoli L, Abidi WM, et al. Time-dependent molecular responses differ between gastric bypass and dieting but are conserved across species. Cell Metab 2018;28(2):310–23 e6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Drucker DJ, Yusta B . Physiology and pharmacology of the enteroendocrine hormone glucagon-like peptide-2. Annu Rev Physiol 2014;76:561–83 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].le Roux CW, Borg C, Wallis K, et al. Gut hypertrophy after gastric bypass is associated with increased glucagon-like peptide 2 and intestinal crypt cell proliferation. Ann Surg 2010;252(1):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Borg CM, le Roux CW, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Patel AG . Biliopancreatic diversion in rats is associated with intestinal hypertrophy and with increased GLP-1, GLP-2 and PYY levels. Obes Surg 2007;17(9):1193–8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cazzo E, Gestic MA, Utrini MP, et al. Glp-2: a poorly understood mediator enrolled in various bariatric/metabolic surgery-related pathophysiologic mechanisms [in Portuguese]. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2016;29(4):272–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Guan X, Stoll B, Lu X, et al. GLP-2-mediated up-regulation of intestinal blood flow and glucose uptake is nitric oxide-dependent in TPN-fed piglets 1. Gastroenterology 2003;125(1):136–147 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Franquet E, Palmer MR, Gifford AE, et al. Rifaximin suppresses background intestinal 18F-FDG uptake on PET/CT scans. Nucl Med Commun 2014;35(10):1026–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].de Groot M, Meeuwis APW, Kok PJM, Corstens FHM, Oyen WJG . Influence of blood glucose level, age and fasting period on nonpathologic FDG uptake in heart and gut. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32(1):98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ozguven MA, Karacalioglu AO, Ince S, Emer MO . Altered biodistribution of FDG in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Nucl Med 2014;28(6):505–11 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kang JY, Kim HN, Yun Y, et al. Gut microbiota and physiologic bowel (18)F-FDG uptake. EJNMMI Res 2017;7(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.