Abstract

Aims

Averaged measurements, but not the progression based on multiple assessments of carotid intima-media thickness, (cIMT) are predictive of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in individuals. Whether this is true for conventional risk factors is unclear.

Methods and results

An individual participant meta-analysis was used to associate the annualised progression of systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with future cardiovascular disease risk in 13 prospective cohort studies of the PROG-IMT collaboration (n = 34,072). Follow-up data included information on a combined cardiovascular disease endpoint of myocardial infarction, stroke, or vascular death. In secondary analyses, annualised progression was replaced with average. Log hazard ratios per standard deviation difference were pooled across studies by a random effects meta-analysis. In primary analysis, the annualised progression of total cholesterol was marginally related to a higher cardiovascular disease risk (hazard ratio (HR) 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 1.07). The annualised progression of systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol was not associated with future cardiovascular disease risk. In secondary analysis, average systolic blood pressure (HR 1.20 95% CI 1.11 to 1.29) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.16) were related to a greater, while high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97) was related to a lower risk of future cardiovascular disease events.

Conclusion

Averaged measurements of systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol displayed significant linear relationships with the risk of future cardiovascular disease events. However, there was no clear association between the annualised progression of these conventional risk factors in individuals with the risk of future clinical endpoints.

Keywords: Risk factors, CVD biomarker, risk factor progression

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is still the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in western countries.1, 2 Carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) is an established non-invasive ultrasound biomarker of subclinical atherosclerosis, and is positively associated with the risk of future CVD events.3 However, we previously reported that annualised cIMT progression, assessed with repeated measurements over a 2–6-year period for individuals in general population cohort studies was not associated with future CVD event risk.4 The explanation for this apparent contradiction is uncertain, but may be related to a low signal-to-noise ratio and diverse demographics of the patient populations in PROG-IMT.

Single time point measurements of traditional CVD risk factors (i.e. systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol) show strong associations with future CVD event risk.5,6 Interestingly, studies prior to the year 2000, which assessed whether the progression of these traditional risk markers was associated with the risk of future CVD events, reported that a decrease in SBP over a 5-year period and increases in TC over a 10-year period were both related to a higher risk of future CVD events.7, 8 However, more recent studies reported no clear consensus on whether the progression of SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol in individuals is associated with future CVD events due to newer medications and better control of these factors.9, 10 Therefore, we aimed to assess whether the annualised progression of the above-mentioned traditional risk factors is associated with future CVD event risk. To draw parallels to the previous cIMT investigation,4 we used the same statistical methods and included only PROG-IMT cohorts with at least two measurements for SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol or HDL-cholesterol.

Methods

Study identification and procedures

Inclusion criteria for PROG-IMT have been described elsewhere.4 A more detailed description can be found in the Supplementary files (online). Briefly, a comprehensive PubMed search for the following criteria was performed: longitudinal observational studies, sample of or similar to the general population, well-defined inclusion criteria and recruitment strategy, at least two visits with assessment of cIMT, clinical follow-up after the second visit recording myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, death, vascular death, or a combination of these. Publications in all languages published until 10 January 2012 were included. Furthermore, articles referenced in reviews on cIMT were manually searched. When a study satisfied the inclusion criteria, the study teams were invited to participate in the project and contribute a predefined individual participant dataset.11 Initially, 22 population studies were identified as potential participants. However, two of these declined participation in the project, one did not reply to the invitation, and three accepted but did not submit their data on time to be included in the analysis. Of the remaining 16 cohorts, only 13 were included in the current analysis involving 34,072 individuals (Table 1) as these required at least two measurements of SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol or HDL-cholesterol.12–23 All datasets underwent central plausibility checks, the variables were harmonised, transformed to SI units, and ordinal variables were recoded into balanced binary categories.4 The clinical endpoints (MI, stroke, vascular death and total mortality) were defined as in the original studies (Supplementary Table 1). Probable or definite MI and any stroke (symptoms lasting more than 24 hours, including non-traumatic haemorrhages) were included.

Table 1.

Included studies.

| Country | Men (n, %) | Age at baseline (years) | Mean duration between the first 2 ultrasound visits (years) | Mean clinical follow-up after the second ultrasound visit (years) | Total number of individuals in SBP analysis (combined endpoint) | Total number of individuals in TC analysis (combined endpoint) | Total number of individuals in LDL analysis (combined endpoint) | Total number of individuals in HDL analysis (combined endpoint) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis and Insulin Resistance study (AIR)12 | Sweden | 297 (100%) | 57–58 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 297 (15) | 291 (14) | 289 (15) | 291 (15) |

| Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC)13 | USA | 5217 (42.7%) | 45–64 | 2.9 | 14.2 | 12,215 (1309) | 12,029 (1279) | 11,733 (1228) | 11,575 (1232) |

| Bruneck study14 | Italy | 299 (47.2%) | 45–84 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 633 (86) | 633 (86) | 633 (86) | 633 (86) |

| Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS)15 | Germany | 1591 (48.4%) | 19–87 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 3280 (119) | 2983 (108) | 2947 (107) | 2970 (108) |

| Cardiovascular Health Study, cohort 1 (CHS1)*16 | USA | 1380 (38.9%) | 65–95 | 2.9 | 8.5 | 3545 (1166) | 3479 (1149) | 3398 (1119) | 3474 (1148) |

| Cardiovascular Health Study, cohort 2 (CHS2)* 16 | USA | 98 (33.0%) | 64–86 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 297 (62) | |||

| Edinburgh Artery Study (EAS)17 | UK | 291 (47.5%) | 60–80 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 578 (34) | |||

| Interventionsprojekt zerebrovaskuläre Erkrankungen und Demenz im Landkreis Ebersberg (INVADE)18 | Germany | 985 (38.9%) | 53–94 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 2533 (239) | 2507 (235) | 2433 (230) | 2502 (235) |

| Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Study (KIHD)19 | Finland | 849 (100%) | 42–61 | 4.1 | 13.7 | 846 (216) | 845 (215) | 833 (213) | 843 (215) |

| Progression of Lesions in the Intima of the Carotid (PLIC)20 | Italy | 607 (39.5%) | 15–82 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 1531 (20) | 1530 (20) | 1506 (20) | 1529 (20) |

| Rotterdam Study21 | Netherlands | 991 (38.0%) | 55–95 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 2577 (512) | 2541 (508) | 2487 (493) | |

| Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP)22 | Germany | 874 (49.9%) | 44–80 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 1750 (192) | 1733 (191) | 1720 (190) | 1728 (191) |

| Tromsø study 23 | Norway | 1823 (45.7%) | 25–79 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 3990 (314) | 3976 (312) | 3970 (311) |

The Cardiovascular Health Study consists of two cohorts, one of white participants and one of African American participants that was begun 3 years later, when the first follow-up visit of the white cohort was due. They were treated as different cohorts in all subsequent analyses.

Statistical analysis

We reproduced the analysis used to assess the association of annualised cIMT progression and future CVD event risk.4 All individuals who experienced stroke or MI prior to the second visit were excluded. Annualised risk factor progression for each individual was defined as the difference between visits 2 and 1, divided by the time separation in years. For each cohort a Cox regression model for the effect of annualised risk factor progression on the risk of future CVD events (combined endpoint of MI, stroke, or vascular death) was calculated. In studies not reporting vascular death, the combined endpoint MI, stroke, or death from any cause was used instead.

Three levels of adjustment were used:

Model 1: Age and sex

Model 2: Model 1 plus risk factor average from the two time points

Model 3: Model 2 plus ethnic origin, socioeconomic status, and average and progression of other confounding risk factors (SBP (not included for analyses of SBP), antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication, TC (not included for analyses of TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol), body mass index, smoking, diabetes, creatinine and haemoglobin)

Ethnic origin and socioeconomic status (based on profession, income or education) were defined differently in each study. The average and progression of binary variables were included as four categories: (a) present at baseline and at follow-up; (b) present at baseline but not at follow-up; (c) not present at baseline but present at follow-up; and (d) not present at either baseline or follow-up. In the case that a confounding risk factor was not available at the follow-up visit, adjustment was made for the baseline confounding risk factor only; if not available at baseline, no adjustment was made (Supplementary Table 2). We pooled the log hazard ratio (HR) estimates per standard deviation (SD) increase of the different studies by random effects meta-analysis24 and displayed them in forest plots. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic.25 Even though outliers were present in some studies, their frequency was very low that their exclusion did not change the results.

Secondary and sensitivity analyses

In addition to the models on annualised risk factor progression, we assessed the association of the average of the two visits for each risk factor with the risk of future CVD events (models 2 and 3). As pharmacological treatment may influence the underlying risk associations, individuals taking antihypertensive medication (definition based on each study), statins (or other lipid-lowering medication) or antidiabetics at either visit were excluded for a sensitivity analysis. Individuals without antihypertensives, statins or antidiabetics are referred to as ‘individuals without cardiovascular medication over time’.

For three studies (ARIC, KIHD, INVADE) risk factors were available for four visits. We explored a potential correlation between risk factor progression in individuals from visits 1 to 2 and from visits 3 to 4.

Inappropriate confounder adjustment

Multivariable regression models which explore the influence of change (or progression) of a parameter from baseline to follow-up in observational studies adjusted for potential confounding factors need to adjust for the average of that parameter and not the baseline value alone. Adjusting for baseline alone would be inappropriate because it is artificially correlated with the change through regression to the mean.26,27 As previous research has often adjusted for baseline alone, we aimed to demonstrate how this would affect the results of our analysis. In particular, we calculated a ‘sensitivity analysis’ for the relation between the annualised progression of SBP and future CVD risk by adjusting for baseline SBP rather than average SBP.

Results

The baseline demographics and CVD events for each study are shown in Table 1. The average time between risk factor measurements ranged from 2.2 to 6.6 years. The means and SDs for the annualised progressions and for the averages of each risk factor in each study are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Association of the annualised progression of SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol with future CVD event risk

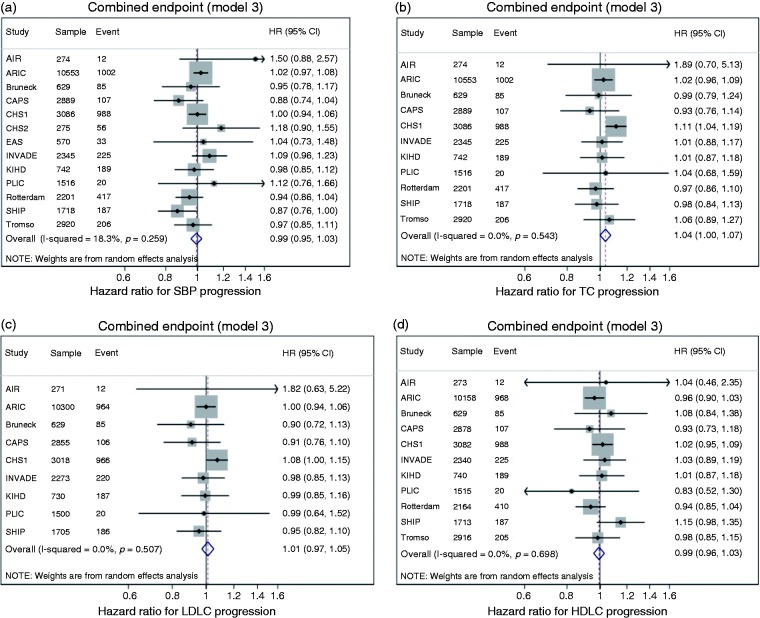

All results discussed in this section relate only to model 3. The results for models 1 and 2 are provided in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, respectively. A one SD larger progression of increase in TC was associated with a greater risk of the combined endpoint (HR 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 1.07). The annualised progression of SBP, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol was not significantly associated with the future CVD event risk (Figure 1). There was no heterogeneity in HRs between studies (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios (HRs) per one standard deviation (SD) increase in annualised risk factor progression for systolic blood pressure (SBP) (a), total cholesterol (TC) (b), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (c) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (d). HRs are for the risk of the combined endpoint. HRs adjusted for vascular risk factors (model 3, see text). Weights are from random effects analysis. AIR: Atherosclerosis and Insulin Resistance study; ARIC: Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities Study; CAPS: Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study; CHS: Cardiovascular Health Study; EAS: Edinburgh Artery Study; INVADE: Interventionsprojekt zerebrovaskuläre Erkrankungen und Demenz im Landkreis Ebersberg; KIHD: Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Study; PLIC: Progression of Lesions in the Intima of the Carotid; SHIP: Study of Health in Pomerania; Rotterdam: Rotterdam Study; Tromsø: Tromsø Study.

Association between average SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol of the two time points with future CVD event risk

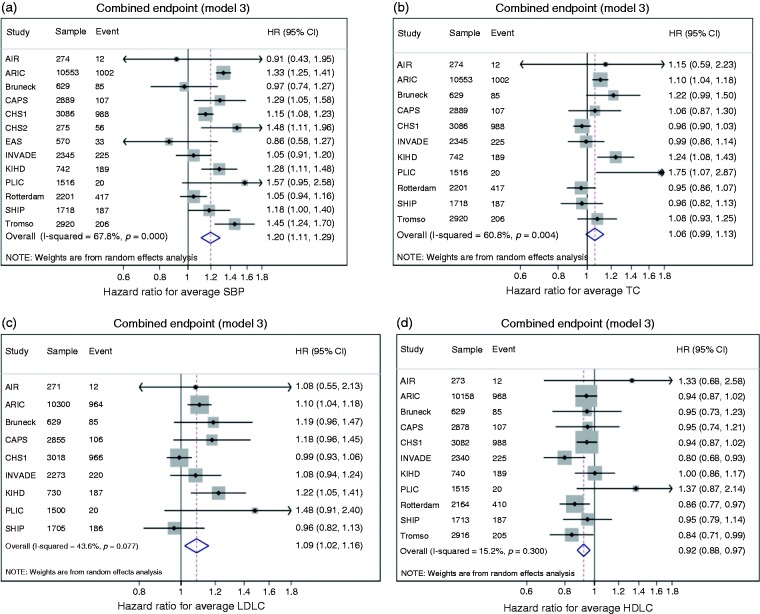

A one SD greater increase in average SBP (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.29) and average LDL-cholesterol (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.16) was associated with a greater risk of future CVD events. A one SD increase in average HDL-cholesterol was related to a lower risk (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97; Figure 2). Average TC was not significantly related to future CVD event risk. The associations of SBP and TC displayed significant heterogeneity between studies, while those for LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol did not (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios (HRs) per one standard deviation (SD) increase in risk factor average from the two visits for systolic blood pressure (SBP) (a), total cholesterol (TC) (b), LDL-cholesterol (c) and HDL-cholesterol (d). HRs are for the risk of the combined endpoint. HRs adjusted for vascular risk factors (model 3, see text). Weights are from random effects analysis. AIR: Atherosclerosis and Insulin Resistance study; ARIC: Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities Study; CAPS: Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study; CHS: Cardiovascular Health Study; EAS: Edinburgh Artery Study; INVADE: Interventionsprojekt zerebrovaskuläre Erkrankungen und Demenz im Landkreis Ebersberg; KIHD: Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Study; PLIC: Progression of Lesions in the Intima of the Carotid; SHIP: Study of Health in Pomerania; Rotterdam: Rotterdam Study; Tromsø: Tromsø Study.

Sensitivity analysis

In the analyses of individuals without cardiovascular medication over time, the sample size was reduced by about half, which altered the results. In these analyses, the annualised progression of SBP, TC and LDL-cholesterol was not associated with the risk of future CVD events. A one SD increase in HDL-cholesterol progression was related to a lower risk (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.99) of future CVD events. There was no heterogeneity with regard to HRs from the different studies for all risk factors (Supplementary Table 6).

In subjects without cardiovascular medication over time, a one SD increase in average SBP (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.41) and LDL-cholesterol (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.23) was associated with a greater risk of future CVD events. No significant relationship was found for average TC. A lower risk was identified for each SD increase in average HDL-cholesterol (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.98; Supplementary Table 7).

In all subjects, using meta-regression across studies, there was no relationship between the log HRs for progression and the time interval between measurements for any of the risk factors.

Consequences of inappropriate confounder adjustment

The results for this analysis are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Adjustment for baseline SBP rather than average SBP resulted in a significantly positive association between annualised SBP progression and the risk of future CVD events (HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.14).

Correlation of risk factor progression

There were no significant correlations of annualised SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol progression in individuals from visits 1 to 2 with the progression from visits 3 to 4 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients for the annualised progression of SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol from visits 1 to 2 and visits 3 to 4.

| Study | SBP | TC | LDL | HDL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIC | –0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | –0.05 |

| KIHD | –0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | –0.03 |

| INVADE | –0.04 | –0.03 | –0.02 | –0.01 |

All correlation coefficients are not statistically significant (i.e. P > 0.05).

SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

We have here found that, similar to cIMT, averaged measurements of SBP, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol displayed significant linear relationships with the risk of future CVD events, while there was no association between the annualised progression of these conventional risk factors in individuals with the risk of future clinical endpoints (i.e. MI, stroke, vascular death).5, 28, 29 The annualised progression of TC displayed a marginally significant positive association for the combined endpoint.

Our results agree with recent studies that assessed the progression of these risk factors and future CVD event risk. In the Whitehall II study, low baseline cardiovascular health was associated with a higher risk of future CVD events, while changes in cardiovascular health were not related.9 In the Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular health progression over a 6-year period was not statistically related to coronary artery calcification progression.30 Interestingly, results from the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration demonstrated that including repeated measurements of risk factors slightly improved CVD risk prediction models.10 Future studies need to focus on differentiating between individual asymptomatic markers of CVD and CVD mortality and a better understanding of the effect of these markers in race-ethnic diverse populations.

In order to improve the understanding of the relation between SBP progression and the risk of CVD events, one needs to differentiate between two types of analyses: studies adjusting for baseline and those using average SBP as a confounder. For example, a Japanese study adjusted for baseline and reported that SBP progression over a 6-year period was associated with an increased risk of stroke.31 Furthermore, a large cohort study similarly reported that progression to hypertension over a 12-year period was associated with a higher lifetime CVD risk.32 However, adjustment for baseline values leads to ‘regression to the mean’ and therefore may not be appropriate.14,15,33 Regression to the mean becomes even more important when repeated measurements are being performed on the same individual. Adjusting for baseline alone would not be useful because it is artificially correlated with the change (see the Supplementary Appendix (online) for further explanation).26, 27 Without adjustment for baseline, SBP progression over a 10-year period was not associated with increased CVD risk in a French cohort.34 We also report that SBP progression is not related to future CVD event risk (Figure 1). Hence, the heterogeneous findings are most likely due to this incorrect adjustment for baseline, although there may be other reasons for the differential findings between the studies. In fact, if we adjusted for baseline and not average SBP, our analysis would show a significantly positive relationship between SBP progression and future CVD event risk (Supplementary Figure 3).

A large number of studies which investigated whether TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol progression are associated with future CVD event risk also adjusted for baseline. In particular, Menotti et al. reported in a meta-analysis that TC progression over 10 years was positively associated with coronary heart disease.7 However, with adjustment for average TC, no significant relation between TC progression and CVD risk was found.35 HDL-cholesterol progression was associated with potentially protective effects.29, 36 In particular, when adjusted for baseline, a HDL-cholesterol decrease over 2.75 years36 and 14 years,29 respectively, was associated with an increased CVD risk. We found no such association (Figure 1), although when we only included individuals without cardiovascular medication over time, a similar inverse association between annualised HDL-cholesterol progression and CVD risk was detected. Therefore, in our opinion, the adjustment for the baseline value of a risk factor instead of risk factor average induces a bias in assessing the true associations between the progression of conventional risk factors and CVD risk.

Our previous investigation showed that cIMT progression was not related to the risk of future CVD events. The previous analysis also showed correlation coefficients near zero for repeated assessments of cIMT progression. For the current study we also assessed the correlation for SBP, TC, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol progression from different visits from three studies. Similar to our cIMT analysis, all correlations within the same individual were near zero (Table 2). Hence, one may wonder how two unrelated events should be able to predict future CVD risk. These findings demonstrate that the signal-to-noise ratio of the measure of progression is too low to allow for appropriate risk prediction.

Statins and other lipid-lowering medication may impact the results in general population cohorts by reducing TC and LDL-cholesterol in individuals with high cardiovascular disease risk and thereby disrupt the underlying associations. In particular, if at-risk patients are treated according to guidelines (e.g. receive statins to lower LDL-cholesterol) but do not reach their target risk factor value, physicians may escalate treatment and thereby influence risk factor progression. This may contribute to the non-significant associations of risk factor progression and future CVD event risk. In addition, newer and more potent lipid-lowering medications have recently been prescribed in many countries.

Implications for public health

We demonstrated that cIMT and conventional risk factors are similar in that accumulated average measurements but not progression based on multiple measurements in individuals predict future cardiovascular event risk. Our results suggest that measuring risk factor progression based on two measurements only a few years apart has a very low signal-to-noise ratio which does not allow for appropriate individual risk prediction. This implies that either more measurements of risk factors, or measurements taken over a longer time span, are necessary to enable effective individual risk prediction. Moreover, we have shown that, in an analysis of risk factor progression, statistical adjustment for the baseline risk factor value alone is misleading and should be avoided.

Take-home message

The progression of conventional risk factors has a low signal-to-noise ratio and is not associated with future cardiovascular disease risk.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, CPR877078 Supplemental Material for Progression of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and vascular disease risk in individuals: insights from the PROG-IMT consortium by Martin Bahls, Matthias W Lorenz, Marcus Dörr, Lu Gao, Kazuo Kitagawa, Tomi-Pekka Tuomainen, Stefan Agewall, Gerald Berenson, Alberico L Catapano, Giuseppe D Norata, Michiel L Bots, Wiek van Gilst, Folkert W Asselbergs, Frank P Brouwers, Heiko Uthoff, Dirk Sander, Holger Poppert, Michael Hecht Olsen, Jean Philippe Empana, Ulf Schminke, Damiano Baldassarre, Fabrizio Veglia, Oscar H Franco, Maryam Kavousi, Eric de Groot, Ellisiv B Mathiesen, Liliana Grigore, Joseph F Polak, Tatjana Rundek, Coen DA Stehouwer, Michael R Skilton, Apostolos I Hatzitolios, Christos Savopoulos, George Ntaios, Matthieu Plichart, Stela McLachlan, Lars Lind, Peter Willeit, Helmuth Steinmetz, Moise Desvarieux, M Arfan Ikram, Stein Harald Johnsen, Caroline Schmidt, Johann Willeit, Pierre Ducimetiere, Jackie F Price, Göran Bergström, Jussi Kauhanen, Stefan Kiechl, Matthias Sitzer, Horst Bickel, Ralph L Sacco, Albert Hofman, Henry Völzke, Simon G Thompson and on behalf of the PROG-IMT Study Group in European Journal of Preventive Cardiology

Acknowledgements

The authors used a restricted access dataset of the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. The ARIC Study was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) in collaboration with the ARIC Study investigators. This article does not necessarily convey the opinions or views of the ARIC Study or the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Author contribution

MB contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation and drafted the manuscript as well as giving final approval. MWL contributed to conception or design and to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation as well as critically revising the manuscript and giving final approval. HV and SGT contributed to conception and design and contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript as well as providing final approval. LG, KK, TPT, SA, GB, AC, GDN, MB, WvG, FWA, FPB, HU, DS, HP, MHO, JPE, US, DB, FV, OHF, MK, EdG, SHT, LG, CS, EBM, JFP, DNY, TR, CDAS, MRS, AIH, GN, SM, LL, PW, HS, MD, MAI, CS, JW, PD, JFP, GB, JKa, SK, MS, HB, RLS and AH contributed to acquisition, critically revising the manuscript and giving final approval.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this work was supported by a variety of institutions and funding agencies.The Bruneck study was supported by the Pustertaler Verein zur Praevention von Herz- und Hirngefaesserkrankungen, Gesundheitsbezirk Bruneck, and the Assessorat fuer Gesundheit (Province of Bolzano, Italy). The Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study was supported by the Stiftung Deutsche Schlaganfall-Hilfe. The Cardiovascular Health Study research reported in this article was supported by contracts (HHSN268201200036C, N01-HC-85239, N01-HC-85079 to N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133) and grant (HL080295) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Bethesda, MD, USA). Additional support was provided through (AG-023629, AG-15928, AG-20098, and AG-027058) from the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD, USA). A full list of principal Cardiovascular Health Study investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm. Etude sur le vieillissement artériel was organised with an agreement between INSERM and Merck, Sharp and Dohme-Chibret. The Northern Manhattan Study/The Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant (R37 NS 029993) and the Oral Infections, Carotid Atherosclerosis and Stroke Study by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (Bethesda, MD, USA) grant (R01 DE 13094). The Interventionsprojekt zerebrovaskuläre Erkrankungen und Demenz im Landkreis Ebersberg Study was supported by AOK Bayern. The Rotterdam Study was supported by the Netherlands Foundation for Scientific Research, ZonMw (Vici 918-76-619). The Study of Health in Pomerania is part of the Community Medicine Research network of the University Medicine Greifswald, Germany, funded by the German Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research for SHIP (BMBF, grant 01ZZ96030, 01ZZ0701). The PROG-IMT project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Lo 1569/2-1, DFG Lo 1569/2-3). Folkert W Asselbergs is supported by UCL Hospitals NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

References

- 1.Atlas Writing Group. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 508–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology, Prevention Statistics Committee, Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137: e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, et al. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2007; 115: 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorenz MW, Polak JF, Kavousi M, et al. PROG-IMT Study Group. Carotid intima-media thickness progression to predict cardiovascular events in the general population (the PROG-IMT collaborative project): a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012; 379: 2053–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arsenault BJ, Rana JS, Stroes ES, et al. Beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: respective contributions of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, and the total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio to coronary heart disease risk in apparently healthy men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 55: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in men. Hypertension 2000; 36: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menotti A, Blackburn H, Kromhout D, et al. Changes in population cholesterol levels and coronary heart disease deaths in seven countries. Eur Heart J 1997; 18: 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tervahauta M, Pekkanen J, Enlund H, et al. Change in blood pressure and 5-year risk of coronary heart disease among elderly men: the Finnish cohorts of the Seven Countries Study. J Hypertens 1994; 12: 1183–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Sloten TT, Tafflet M, Perier MC, et al. Association of change in cardiovascular risk factors with incident cardiovascular events. JAMA 2018; 320: 1793–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paige E, Barrett J, Pennells L, et al. Use of repeated blood pressure and cholesterol measurements to improve cardiovascular disease risk prediction: an individual-participant-data meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2017; 186: 899–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenz MW, Bickel H, Bots ML, et al. PROG-IMT Study Group. Individual progression of carotid intima media thickness as a surrogate for vascular risk (PROG-IMT): rationale and design of a meta-analysis project. Am Heart J 2010; 159: 730–736 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallenfeldt K, Bokemark L, Wikstrand J, et al. Apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-I in relation to the metabolic syndrome and change in carotid artery intima-media thickness during 3 years in middle-aged men. Stroke 2004; 35: 2248–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, et al. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, 1987–1993. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 146: 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiechl S, Egger G, Mayr M, et al. Chronic infections and the risk of carotid atherosclerosis: prospective results from a large population study. Circulation 2001; 103: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenz MW, von Kegler S, Steinmetz H, et al. Carotid intima-media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke 2006; 37: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG, et al. Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sander D, Kukla C, Klingelhöfer J, et al. Relationship between circadian blood pressure patterns and progression of early carotid atherosclerosis: a 3-year follow-up study. Circulation 2000; 102: 1536–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch J, Kaplan GA, Salonen R, et al. Socioeconomic status and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Prospective evidence from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997; 17: 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norata GD, Garlaschelli K, Ongari M, et al. Effects of fractalkine receptor variants on common carotid artery intima-media thickness. Stroke 2006; 37: 1558–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iglesias del Sol A, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness at different sites: relation to incident myocardial infarction. The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2002; 23: 934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Sarnowski B, Ludemann J, Volzke H, et al. Common carotid intima-media thickness and Framingham risk score predict incident carotid atherosclerotic plaque formation: longitudinal results from the study of health in Pomerania. Stroke 2010; 41: 2375–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stensland-Bugge E, Bonaa KH, Joakimsen O, et al. Sex differences in the relationship of risk factors to subclinical carotid atherosclerosis measured 15 years later: the Tromso study. Stroke 2000; 31: 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lord FM. A paradox in the interpretation of group comparisons. Psychol Bull 1967; 68: 304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, et al. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 162: 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borghi C, Dormi A, L’Italien G, et al. The relationship between systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular risk – results of the Brisighella Heart Study. J Clin Hypertens 2003; 5: 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahilly-Tierney C, Bowman TS, Djousse L, et al. Change in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and incident coronary heart disease in apparently healthy male physicians. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102: 1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang SJ, Onuma O, Massaro JM, et al. Maintenance of ideal cardiovascular health and coronary artery calcium progression in low-risk men and women in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation Cardiovasc Imag 2018; 11: e006209–e006209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu Y, Kato H, Lin CH, et al. Relationship between longitudinal changes in blood pressure and stroke incidence. Stroke 1984; 15: 839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen N, Berry JD, Ning H, et al. Impact of blood pressure and blood pressure change during middle age on the remaining lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease: the cardiovascular lifetime risk pooling project. Circulation 2012; 125: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol 2005; 34: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benetos A, Zureik M, Morcet J, et al. A decrease in diastolic blood pressure combined with an increase in systolic blood pressure is associated with a higher cardiovascular mortality in men. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iribarren C, Reed DM, Chen R, et al. Low serum cholesterol and mortality. Which is the cause and which is the effect? Circulation 1995; 92: 2396–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laitinen DL, Manthena S. Impact of change in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol from baseline on risk for major cardiovascular events. Adv Ther 2010; 27: 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, CPR877078 Supplemental Material for Progression of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and vascular disease risk in individuals: insights from the PROG-IMT consortium by Martin Bahls, Matthias W Lorenz, Marcus Dörr, Lu Gao, Kazuo Kitagawa, Tomi-Pekka Tuomainen, Stefan Agewall, Gerald Berenson, Alberico L Catapano, Giuseppe D Norata, Michiel L Bots, Wiek van Gilst, Folkert W Asselbergs, Frank P Brouwers, Heiko Uthoff, Dirk Sander, Holger Poppert, Michael Hecht Olsen, Jean Philippe Empana, Ulf Schminke, Damiano Baldassarre, Fabrizio Veglia, Oscar H Franco, Maryam Kavousi, Eric de Groot, Ellisiv B Mathiesen, Liliana Grigore, Joseph F Polak, Tatjana Rundek, Coen DA Stehouwer, Michael R Skilton, Apostolos I Hatzitolios, Christos Savopoulos, George Ntaios, Matthieu Plichart, Stela McLachlan, Lars Lind, Peter Willeit, Helmuth Steinmetz, Moise Desvarieux, M Arfan Ikram, Stein Harald Johnsen, Caroline Schmidt, Johann Willeit, Pierre Ducimetiere, Jackie F Price, Göran Bergström, Jussi Kauhanen, Stefan Kiechl, Matthias Sitzer, Horst Bickel, Ralph L Sacco, Albert Hofman, Henry Völzke, Simon G Thompson and on behalf of the PROG-IMT Study Group in European Journal of Preventive Cardiology