Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare wear of the natural teeth against polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia and polished lithium disilicate crowns.

Study Setting and Design:

Experimental type of study.

Materials and Methods:

Polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia and polished lithium disilicate crowns were fabricated and given to 15 patients each (n=15). Crowns were fabricated opposing natural tooth. Patients were recalled after 1year and impression were recorded with opposing arch and baseline and final cast were scanned and superimposed using 3 D scanner.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data collected by experiments were computerized and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. The normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk tests. The data were normally distributed. Statistical analysis was done by using tools of descriptive statistics such as Mean, and Standard Deviation for representing quantitative data (enamel wear measured in μm) Parametric tests: Student t-test for intergroup comparison was done.

Results:

No statistical difference were found between wear of opposing enamel for polished yttrium tetragonal and polished lithium disiliacte crowns [p=0.446].

Conclusion:

Within the limitations of the study, it can be concluded that polished lithium disilicate showed better clinical outcome than polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia, though the evaluated data was statistically non significant.

Keywords: Polished lithium disilicate, polished yttrium tetragonal zirconai, wear polished yttrium tetragonal zirconai, polished lithium disilicate, wear

INTRODUCTION

Enamel wear is a complex process, which is influenced by the thickness and hardness of the enamel. Occlusal antagonist contact is an essential reason for wear and gradual removal of dental material. Wear is caused by ploughing of hard asperities into softer surfaces, the chewing behavior in combination with parafunctional habits and neuromuscular forces, as well as the abrasive influence of food and antagonist causes wear.[1]

The placement of full-coverage crowns constitutes the most common fixed prosthodontic treatment. To meet the ever-increasing demand of patients for esthetic, metal-free, biocompatible restorations, manufacturers have developed several types of all ceramic restorations such as feldspathic porcelain, leucite-reinforced glass ceramic, lithium disilicate glass ceramic, glass-infiltrated alumina, and yttrium tetragonal zirconia during the last few decades.[2] Ceramics mimic the optical characteristics of enamel and dentin and are biocompatible and chemically durable, thus are widely used in dentistry.

At present, lot of research and clinical trials are being carried out on yttrium tetragonal zirconia owing to its favorable dimensional stability, mechanical resistance, hardness, and elastic modulus.[3] In-vitro studies have demonstrated a flexural strength of 900–1200 MPa and fracture toughness of 9–10MPa/m½.[4]

The Empress II system uses a lithium disilicate glass core material. The framework is fabricated either with lost wax and heat pressure technique or is milled out of prefabricated blanks. For lithium disilicate core material, the fracture toughness ranges between 2.8 and 3.5 MPa/m½. Lithium disilicate allows the fabrication of translucent restorations, recommended that these restorations are luted properly for their strength and longevity.[5]

The wear of human enamel and restorative material itself is often a critical concern when selecting a restorative material in any given clinical situation.[6,7] Various in-vitro studies involving yttrium tetragonal zirconia and lithium disilicate have been performed using different test methods such as ACTA and OSHU to evaluate the effect of glazing and polishing of yttrium tetragonal zirconia and lithium disilicate crowns on opposing natural enamel.[8]

However, attempts to correlate the in-vitro results with the long-term, in vivo situation have not been very successful. Complex in vivo wear behavior cannot be predicted from physical and mechanical testing.[9,10] in-vitro studies do not represent the actual masticatory environment and cannot simulate the intricate chewing pattern. Hence, there was a need for an in vivo study evaluating the wear potential of monolithic yttrium-tetragonal zirconia polycrystals (Y-TZP) and monolithic lithium disilicate crowns and comparing it with the wear occurring in natural dentition.

Hence, a clinical study was planned to comparatively evaluate the volumetric wear of enamel opposing natural antagonist, polished lithium disilicate, and polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia crowns using a laboratory-based novel technique of three-dimensional (3D) scanning and image superimposition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical committee approval and study design

This study was carried out in the Department of Prosthodontics, SMBT Dental College and Hospital, Sangamner, Maharashtra, India, in 2017–2018. Ethics was granted by the Institutional Ethical Committee and research board approval. Informed consent was signed by the patient in their regional languages, and the study conducted according to the ethical standards given in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

Sample size calculation and selection of the sample

The sample size was calculated using the references of related articles, studies, reviews, and sample size formula. The power of the study is less; thus, the sample size was taken as 30.

The sample was divided into two groups, namely Groups A and B. Each group was assigned 15 participants each. The study was randomized clinical trial, and the samples were selected using these inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

The inclusion criteria for the participants were as follows:

- Normal occlusion

- Presence of natural antagonist against the proposed full-coverage crown

- Participants needed a crown on either first molar or second molar of any arch

- Presence of natural antagonist on the contralateral side for comparative analysis

- The age group of 20–40 years.

-

The exclusion criteria for the participants were as follows:

- Medical contraindication for dental treatment

- Participants with parafunctional habits, for example, bruxism

- Participants with temporomandibular joint disorder and habit of unilateral mastication

- Uncertain residency in the area within the 1-year duration of the study.

Procedure of study

From the selected thirty participants, 15 participants were divided into Group A to receive polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia full-coverage crowns, and 15 participants were divided into Group B to receive polished lithium disilicate full-coverage crowns. The tooth preparation for individual participants was done following the standard protocol. Polished monolithic yttrium tetragonal zirconia (Sagemax white zirconia blocks) and polished lithium disilicate (Ingots-IPS e. max, IvoclarVivadent, Germany) full-coverage crowns were fabricated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each full-coverage crown was cemented using Type I glass-ionomer luting cement (GC Gold Label, Japan).

Data collection

The baseline data were collected by recording the impression of the arch opposing the full-coverage crown at the time of cementation with medium-bodied consistency polyvinyl-siloxane impression (medium body, Reprosil, Dentsply, USA) material in the photopolymerized tray (Voco Profibase, Germany). A 3D white light scanner [ZirkonZannSagoo Arti, Germany; Figure 1] with accuracy up to 14 μm was used to scan the baseline casts. The participants were recalled for the evaluation of the full-coverage crowns after 12 months. At the end of 12 months, the final data were then collected by recording a second impression of the arch opposing the cemented full-coverage crown with medium-bodied consistency polyvinyl-siloxane impression material. This final impression was disinfected, poured, and the cast was scanned in a similar manner as the baseline casts.

Figure 1.

White light scanner (Sagoo, Arti)

Data analysis

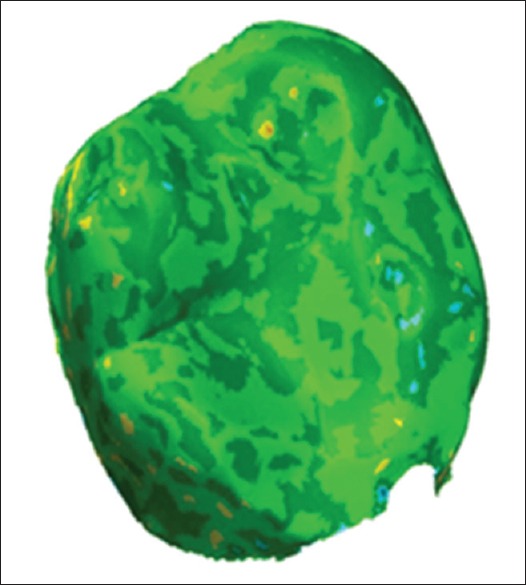

After scanning, the scanner was allowed for 3D superimposition of the baseline and final scanned images of individual participants by the selection of three reference points or areas that are not subjected to wear. It then locates and quantifies the spatial differences between the two images, thereby measuring the amount of wear in three dimensions, giving a more realistic view of the clinical characteristics of wear and the potential mechanisms involved [Figures 2 and 3]. Data collected by experiments were computerized and statistically analyzed. The normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Lawson et al., in their study, used a similar test for normality evaluation.[9] The data were normally distributed. Statistical analysis was performed by using the tools of descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation for representing quantitative data (enamel wear measured in μm) parametric tests: Student's t-test for intergroup comparison was done as the sample size was not more than 30.

Figure 2.

Scanned images superimposed

Figure 3.

Analysis of scanned images using polywork software

RESULTS

Wear was measured using baseline and 12-month interval cast of opposing dentition and 3D scanning and superimposition technique. The enamel wear recorded in the participants of Group 1 and Group 2 at the end of 12 months interval is tabulated in Table 1 and for Group 2 in Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of amount of natural enamel wear against polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia Crowns (Group 1) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (Control Group)

| Case number | Group 1 – Polished yttrium–tetragonal polycrystals crowns | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth number with crowns | Antagonist tooth number | Enamel wear (mm) against crowns | Natural teeth considered | Mean enamel wear (mM) of natural antagonist | |

| 1 | 16 | 46 | 52.34 | 26.36 | 34.25 |

| 2 | 46 | 16 | 32.35 | 26.36 | 35.24 |

| 3 | 26 | 36 | 35.12 | 16.46 | 32.14 |

| 4 | 26 | 36 | 40.00 | 16.46 | 30.90 |

| 5 | 36 | 26 | 40.12 | 16.46 | 43.05 |

| 6 | 26 | 36 | 48.97 | 16.46 | 27.75 |

| 7 | 26 | 36 | 40.17 | 16.46 | 32.03 |

| 8 | 37 | 27 | 42.35 | 17.47 | 30.03 |

| 9 | 46 | 16 | 38.46 | 26.36 | 32.17 |

| 10 | 26 | 36 | 34.82 | 16.46 | 34.55 |

| 11 | 16 | 46 | 54.24 | 26.36 | 32.32 |

| 12 | 17 | 47 | 46.04 | 27.37 | 42.18 |

| 13 | 36 | 26 | 42.03 | 16.46 | 41.65 |

| 14 | 46 | 16 | 35.02 | 26.36 | 35.05 |

| 15 | 46 | 16 | 48.00 | 26.36 | 37.01 |

Table 2.

Comparison of amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate Crowns (Group 2) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (Control Group)

| Case number | Group 2 – Polished lithium disilicate crowns | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth number with crowns | Antagonist tooth number | Enamel wear (μm) against crowns | Natural teeth considered | Mean enamel wear (mm) of natural antagonist | |

| 1 | 36 | 26 | 37.94 | 16.46 | 20.57 |

| 2 | 46 | 16 | 47.31 | 26.36 | 40.40 |

| 3 | 46 | 16 | 29.07 | 26.36 | 35.3 |

| 4 | 16 | 46 | 38.00 | 26.36 | 41.38 |

| 5 | 36 | 26 | 36.05 | 16.46 | 28.46 |

| 6 | 26 | 36 | 48.09 | 16.46 | 35.42 |

| 7 | 27 | 37 | 45.09 | 17.47 | 37.71 |

| 8 | 37 | 27 | 32.05 | 17.47 | 36.57 |

| 9 | 16 | 46 | 50.07 | 26.36 | 33.34 |

| 10 | 36 | 26 | 35.6 | 16.46 | 28.92 |

| 11 | 46 | 16 | 42.19 | 26.36 | 30.42 |

| 12 | 46 | 16 | 38.32 | 26.36 | 40.25 |

| 13 | 26 | 36 | 40.56 | 16.46 | 42.25 |

| 14 | 36 | 26 | 50.64 | 16.46 | 35.25 |

| 15 | 16 | 46 | 30.05 | 26.36 | 32.14 |

A statistically significant difference was found in the comparison of the amount of natural enamel wear against polished zirconia crowns (Group 1) with the amount of natural enamel wear against natural antagonist (control Group 1, i.e., 34.55 μm) (P = 0.017) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of amount of natural enamel wear against polished yttrium–tetragonal zirconia polycrystals crowns (Group 1) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (Control group)

| Groups | Mean (μm) | SD | SE | Student t-test | P, significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel wear against Polished Y-TZP crowns (group 1) | 42.0 | 6.66 | 1.72 | 3.205 | 0.017, significant statistical difference |

| Enamel wear against natural antagonist (control group) | 34.68 | 6.49 | 1.68 |

P>0.05: Not significant, P<0.05: Significant, P<0.001: Highly significant. Y-TZP: Yttrium–tetragonal zirconia polycrystals, SD: Standard deviation, SE: Standard error

A statistically significant difference was found in the comparison of the amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2) with the amount of natural enamel wear against natural antagonist (control Group 2, i.e., 34.68 μm) (P = 0.002) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (control group)

| Groups | Mean (μm) | SD | SE | Student t-test | P, significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (group 2) | 40.06 | 7.03 | 1.81 | 2.274 | 0.031, Significant statistical difference |

| Enamel wear against natural antagonist (control group) | 35.09 | 4.72 | 1.22 |

P>0.05: Not significant, P<0.05: Significant, P<0.001: Highly. SD: Standard deviation, SE: Standard error

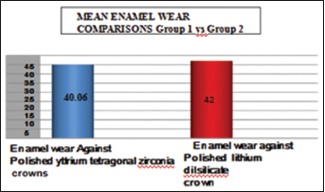

On the comparison of polished zirconia crowns (Group 1, i.e., 40.06 μm) with the amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2, i.e., 42 μm), no statistically significant difference was found among both experimental groups (P = 0.446). It is suggested that enamel wear occurring against both experimental groups was comparable [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison of amount of natural enamel wear against polished Yttrium–tetragonal zirconia polycrystals crowns (Group 1) with amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2)

| Groups | Mean (μm) | SD | SE | Student t-test | P, significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel wear against polished Y-TZP crowns (Group 1) | 42.0 | 6.66 | 1.72 | 0.773 | 0.446, no significant statistical difference |

| Enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2) | 40.06 | 7.03 | 1.81 |

P>0.05: Not significant, P<0.05: Significant, P<0.001: Highly. Y-TZP: Yttrium–tetragonal zirconia polycrystals, SD: Standard deviation, SE: Standard error

DISCUSSION

When tooth to tooth or tooth and restoration are in contact, they slide against each other and unavoidable changes occur in natural enamel. However, materials in restorative procedures accelerate this natural process. These materials may have wear properties that differ from those of the tooth structure. Either enamel causes wear of these materials or these materials cause aggressive wear of the enamel.[11]

An essential feature of the materials used in the restoration of the occlusal surfaces of fixed and removable partial dentures is resistance to wear and the lack of negative influence on the opposing teeth. To observe and assess wear, it is necessary to understand tooth wear mechanisms.[12]

Pindborg classified the loss of hard tissue as caries, erosion, attrition, or abrasion.[11] Principally, wear can be of five types, attrition wear, abrasive and cutting wear, corrosive wear, surface fatigue, and other minor types of wear. The two common types of wear seen in the oral cavity include the attrition wear and the abrasive type of wear or the combination of both. These two types of wear are of the utmost importance when new restorative material is used.[13] Wear of the antagonist depends on the ceramic material, and other factors such as fracture toughness, internal porosities, and surface defects may also accelerate the loss of opposing enamel. Hence, this in vivo study was conducted to evaluate the wear of the occlusal surfaces of teeth opposing polished Y-TZP crowns and polished lithium disilicate crowns.

A statistically significant difference was found after comparing the amount of natural enamel wear against polished Y-TZP crowns (Group 1) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (Control group 1) (P = 0.017). The results suggested that the occurrence of natural enamel wear is significantly more against polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia crowns as compared to the natural antagonist [Table 1 and Graph 1].

Graph 1.

Comparison of Polished Yttrium Tetragonal Zirconia (Group 1) vs Polished Lithium Disilicate (Group 2)

Stober et al. measured enamel opposing zirconia that was polished, glazed, adjusted, and re-polished in a 6-month clinical study. They found more wear on teeth opposing zirconia crowns (33 μm/6 mo) than teeth opposing natural teeth (10 μm/6 mo). Furthermore, in this study, wear of the contralateral natural tooth pair was assessed. The result obtained showed that the enamel wear by the enamel of the contralateral teeth was significantly less than the wear of the teeth which were opposed by zirconia (means: 10 μm vs. 33 μm, maximum 46 μm versus 112 μm).[14]

A statistically significant difference was found by the comparison of the amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2) with enamel wear against natural antagonist (control Group 2) (P = 0.031). The results showcased that the occurrence of natural enamel wear is significantly more against polished lithium disilicate crowns as compared to the natural antagonist.

On comparison of the amount of natural enamel wear against polished Y-TZP crowns (Group 1) with the amount of natural enamel wear against polished lithium disilicate crowns (Group 2), no statistically significant difference was found among both experimental groups (P = 0.446). It is suggested that both experimental groups (crowns) were similar in producing an amount of natural enamel wear.

Lawson et al. compared the wear of a steatite antagonist against polished, glazed, and adjusted lithium disilicate and zirconia crowns. In their study, no statistically significant difference was noted between polishing, glazing, or adjusting any of the ceramics. Furthermore, like some other studies, this study stated that no surface wear was seen on polished or adjusted zirconia, but measurable wear occurred on the surface of lithium disilicate.[9]

A review of the literature from various other studies is in support of this study. According to al-Hiyasat et al., porcelain postadjustment should be glazed or polished to minimizes opposing enamel wear as after adjustment is broken porcelain fragment help wear of opposing enamel with the same rate.[15]

A study by Mitov et al. suggested girt used for adjusting zirconia affects opposing enamel wear. Zirconia adjusted with fine 30 μm diamond burs produces similar opposing enamel wear as polished zirconia and less compared to adjusted zirconia with coarse 100 μm diamond bur.[16]

Lithium disilicate has shown to produce more volumetric wear loss than zirconia when opposed by zirconia.[17] Previous studies have shown that lithium disilicate caused more wear to oppose enamel than zirconia.[18,19,20] While another study found that lithium disilicate causes less enamel wear than zirconia.[21]

Lambrechts et al. stated that the examination of teeth could best determine the rate at which the enamel is lost in the same individuals over some time. The gradual wear of opposing teeth is a normal phenomenon in the human dentition.[22] At an ultrastructural level, modification in the surface wear of natural tooth structure and antagonistic restorative material occurs. It is a contributing role of structure of restorative material, crystal size, and surface hardness in controlling antagonistic enamel wear.[23] In this study, the 3D anatomical changes of the functional occlusal surfaces of the tooth were elucidated over time. A highly accurate 3D optical scanner that uses the principles of triangulation and reference automated 3D-superimposition software was used.

The study shows no statistical difference between polished zirconia and polished lithium disilicate crown. The probable reason for it could be a monolithic crown; it is in accordance with the studies by Rupawala et al., Palmer et al., and Lawson et al.[9,24,25,26]

Limitations of this study would be further long-term studies can be envisioned using direct intraoral scanning, larger sample size, and other parameters not included in this study. A new approach would be more pragmatic, integrating problem-based learning, and evidence-based dentistry with the traditional overview of clinical materials and material science concepts, which is still more important to maintain the balance of the stomatognathic system.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this in vivo study, the conclusion is in accordance with expected objectives or hypotheses. It can be concluded that polished lithium disilicate showed better clinical outcomes than polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia, though the evaluated data were statistically nonsignificant. While the comparison of polished yttrium tetragonal zirconia crowns and polished lithium disilicate against natural enamel wear showed significant results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Preis V, Behr M, Kolbeck C, Hahnel S, Handel G, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of substructure ceramics and veneering porcelains. Dent Mater. 2011;27:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva NR, Thompson VP, Valverde GB, Coelho PG, Powers JM, Farah JW, et al. Comparative reliability analyses of zirconium oxide and lithium disilicate restorations in vitro and in vivo. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(Suppl 2):4S–9S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agustín-Panadero R, Román-Rodríguez JL, Ferreiroa A, Solá-Ruíz MF, Fons-Font A. Zirconia in fixed prosthesis. A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e66–73. doi: 10.4317/jced.51304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daou EE. The zirconia ceramic: Strengths and weaknesses. Open Dent J. 2014;8:33–42. doi: 10.2174/1874210601408010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raigrodski AJ. Contemporary materials and technologies for all-ceramic fixed partial dentures: A review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 2004;92:557–62. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmaria A, Goldstein G, Vijayaraghavan T, Legeros RZ, Hittelman EL. An evaluation of wear when enamel is opposed by various ceramic materials and gold. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:345–53. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A, Swain M, He L, Lyons K. Wear behavior of human enamel against lithium disilicate glass ceramic and type III gold. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:1399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mundhe K, Jain V, Pruthi G, Shah N. Clinical study to evaluate the wear of natural enamel antagonist to zirconia and metal ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2015;114:358–63. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawson NC, Janyavula S, Syklawer S, McLaren EA, Burgess JO. Wear of enamel opposing zirconia and lithium disilicate after adjustment, polishing and glazing. J Dent. 2014;42:1586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zandparsa R, El Huni RM, Hirayama H, Johnson MI. Effect of different dental ceramic systems on the wear of human enamel: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2016;115:230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong R. Intra-oral restorative materials wear: Rethinking the current approaches: How to measure wear. Dent Mater. 2006;22:702–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koczorowski R, Włoch S. Evaluation of wear of selected prosthetic materials in contact with enamel and dentin. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:453–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)80013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heintze SD. How to qualify and validate wear simulation devices and methods. Dent Mater. 2006;22:712–34. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagger DC, Harrison A. An in vitro investigation into the wear effects of selected restorative materials on enamel. J Oral Rehabil. 1995;22:275–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1995.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.al-Hiyasat AS, Saunders WP, Sharkey SW, Smith GM, Gilmour WH. The abrasive effect of glazed, unglazed, and polished porcelain on the wear of human enamel, and the influence of carbonated soft drinks on the rate of wear. Int J Prosthodont. 1997;10:269–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitov G, Heintze SD, Walz S, Woll K, Muecklich F, Pospiech P. Wear behavior of dental Y-TZP ceramic against natural enamel after different finishing procedures. Dent Mater. 2012;28:909–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albashaireh ZS, Ghazal M, Kern M. Two-body wear of different ceramic materials opposed to zirconia ceramic. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;104:105–13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MJ, Oh SH, Kim JH, Ju SW, Seo DG, Jun SH, et al. Wear evaluation of the human enamel opposing different Y-TZP dental ceramics and other porcelains. J Dent. 2012;40:979–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preis V, Weiser F, Handel G, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of monolithic dental ceramics with different surface treatments. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:393–405. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosentritt M, Preis V, Behr M, Hahnel S, Handel G, Kolbeck C. Two-body wear of dental porcelain and substructure oxide ceramics. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:935–43. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amer R, Kurklu D, Kateeb E, Seghi RR. Three body wear potential of dental yttrium stabilized zirconia ceramic after grinding polishing and glazing treatments. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;101:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambrechts P, Braem M, Vuylsteke-Wauters M, Vanherle G. Quantitative in vivo wear of human enamel. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1752–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulay G, Dugal R, Buhranpurwala M. An evaluation of wear of human enamel opposed by ceramics of different surface finishes. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2015;15:111–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-4052.155031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rupawala A, Musani SI, Madanshetty P, Dugal R, Shah UD, Sheth EJ. A study on the wear of enamel caused by monolithic zirconia and the subsequent phase transformation compared to two other ceramic systems. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2017;17:8–14. doi: 10.4103/0972-4052.194940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer DS, Barco MT, Pelleu GB, Jr, McKinney JE. Wear of human enamel against a commercial castable ceramic restorative material. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:192–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90161-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gundugollu Y, Yalavarthy RS, Krishna MH, Kalluri S, Pydi SK, Tedlapu SK. Comparison of the effect of monolithic and layered zirconia on natural teeth wear: An in vitro study. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2018;18:336–42. doi: 10.4103/jips.jips_105_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]