Abstract

In the era of evidence based dentistry, a well-documented consolidated data about improvements in dentistry is a necessity. Concentrated growth factor (CGF) is an emerging trend in periodontology and now in implant dentistry. Various studies have been published in the literature evaluating the effect of CGF on implant osseointegration, implant stability, survival rate, sinus augmentation, and peri-implant defects. However, no systematic review has yet been documented. The present systematic review, being first of its kind, aimed to evaluate the potential outcomes of employing CGF in implant treatment. A literature search was carried out in PubMed and Google scholar for articles published between 2001 and 2019, with various keywords such as “CGF,” “dental implant,” “bone regeneration,” “CGF,” and “osseointegration.” The screening of studies was done according to PRISMA guidelines. A total of eleven studies were included in this review. Majority of the included studies pointed toward the beneficial effects of CGF in implant treatment. CGF was seen to promote osseointegration and enhance bone regeneration. Although more clinical studies are required to validate the potential merits of CGF in the long run, the preliminary results seem promising.

Keywords: Bone regeneration, concentrated growth factor and osseointegration, concentrated growth factor, dental implant

INTRODUCTION

Dental implants have come a long way in reinstating the comfort and health of the stomatognathic system. A very good success rate of 94% has been documented for implant-supported prosthesis.[1] However, it is not uncommon to encounter cases with qualitative and quantitative reduction of alveolar bone. The best way to ensure the predictability of implant treatment in such cases is enhancing osseointegration. Various methods in the literature have been proposed to facilitate this process, including alteration of implant topography, surface morphology, roughness, surface energy, strain hardening, chemical composition, the presence of impurities, thickness of titanium oxide layer and the presence of nonmetal and metal composites.[2] Another method of accelerating osseointegration is the modulation of healing after the placement of implant. This is where bioactive molecules called growth factors (GFs) come in picture.[3]

Platelets are a natural source of GFs including platelet-derived GF, transforming GF (TGF)-β1 and β2 (TGF-β2), fibroblast GF, vascular endothelial GF, and the insulin-like GF which stimulate cell proliferation, matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis.[4] Concentrated GF (CGF) was developed by Sacco in the year 2006.[5] It is produced by centrifuging venous blood, as a result of which the platelets are concentrated in a gel layer, comprising of a fibrin matrix rich in GFs and leukocytes.[6] CGF acts by degranulation of the alpha granules in platelets which play a vital role in early wound healing.[7] It has been found that CGF contains more GFs than the other platelet-based preparations such as platelet rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and unlike PRP, CGF does not dissolve rapidly following application.[8] Qin et al. proved that CGF could release GFs for at least 13 days.[9] In vitro studies have established the beneficial effects of CGF in promoting bone regeneration around implants.[10,11] Animal studies have also reported its potential merits.[6,12,13]

The literature comprises of several case reports, case series, prospective, and retrospective studies which outline the advantages of using CGF for bone regeneration.[14,15,16] However, there is no systematic review analyzing the potential benefits of CGF in dental implantology. Therefore, this systematic review was planned to retrieve a detailed data pool from the published literature to consolidate information on the effects of CGF in implant dentistry.

The focused question was formulated according to the PRISMA Guidelines. The P: Problem/Population, I: Intervention, C: Comparison, O: Outcome, S: Study design question framed was: “Is there any additional benefit of CGF on guided bone regeneration and implant therapy over traditional approaches in terms of clinical, histological and radiographic outcomes?” The study designs of interest were randomized controlled clinical studies, prospective and retrospective studies [Table 1].

Table 1.

PICOS Question for the Study

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Focus question | Is there any additional benefit of CGF on guided bone regeneration and implant therapy over traditional approaches in terms of clinical, histological, and radiographic outcomes? |

| Population | Human subjects with lack of alveolar bone and need of implant therapy (immediate placement or conventional) |

| Intervention | Use of CGF alone or in combination with a graft material in guided bone regeneration techniques and implant therapy |

| Comparison | Respective surgical procedure without CGF or change in baseline data using CGF |

| Outcome | Alveolar bone regeneration, soft tissue healing, osseointegration, implant stability, vertical bone gain, and implant survival rate |

| Study design | Randomized controlled clinical trials, prospective study, and retrospective study |

CGF: Concentrated growth factor

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was conducted based on the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration.[17]

Search strategy

The initial electronic literature search was independently conducted by two investigators (BL and DG) from January 2001 to October 2019, using MEDLINE (PubMed) and Google Scholar for articles in English language published in journals of dentistry using following search terms: “CGF and dental implants,” “CGF and dental implants and bone regeneration,” “ CGF and osseointegratiom” “CGF in implant dentistry,” “CGF and dental implant NOT plasma rich fibrin.” The search filters were not restricted by design or region. The results were limited to human studies. For Google scholar, the keywords were identified through the “advanced search” option appearing “anywhere in the article.”

The “related articles” option in the search engines was used. An additional hand search was carried out including the bibliographies of the selected papers and other narrative and systematic reviews.

Inclusion criteria

Studies designed as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), retrospective and prospective clinical studies

Studies evaluating placement of dental implant/s in human participants

Studies with an observation time of at least 3 months after implant placement

Studies evaluating clinical and radiographic changes after use of CGF.

Exclusion criteria

Implant studies carried out on animal subjects

In vitro or bench research studies including finite element analysis

Case series, case reports, or review articles

Studies which did not have full text retrievable

Duplicate studies.

Screening and selection of studies

Publication records and titles identified by the electronic search and hand search were independently screened by two reviewers (BL and DG) based on the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were solved by discussion including a third reviewer (Rheumatoid arthritis [RA]). Cohen's Kappa coefficient was used as a measure of agreement between the readers. Thereafter, full texts of the selected abstracts were obtained. The two reviewers independently performed the screening process, and then, articles that met the inclusion criteria were processed for data extraction.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extraction was done based on the inclusion criteria. The studies were classified according to study design and outcome variables. Then, outcomes were compiled in tables. All extracted data were double-checked, and any questions that came up during the screening and the data extraction were discussed within the authors to aim for consensus. Two reviewers (BL and DG) independently evaluated the methodological quality of all included studies. Any disagreement was discussed with the third reviewer (RA) until consensus was achieved.

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to assess the methodological quality of the included prospective and retrospective cohort and case–control studies [Table 2].[18] The Jadad scale was used for assessing RCTs [Table 3].[27]

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the prospective and retrospective nonrandomized studies using Newcastle–Ottawa scale

| Study (year) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (2014)[19] | *** | * | *** |

| Manoj et al. (2018)[20] | *** | ** | *** |

| Shetty et al. (2018)[21] | *** | ** | *** |

| Yang et al. (2014)[22] | *** | * | *** |

| Chen et al. (2016)[23] | *** | * | *** |

| Özveri Koyuncu et al. (2019)[24] | *** | ** | *** |

| Pirpir et al. (2017)[25] | *** | ** | *** |

| Sohn et al.(2017)[26] | *** | * | *** |

*,**,***is the quality assessment score according to Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Table 3.

Quality assessment of Randomized controlled studies using Jadad scale

| Isler et al.(2018)[28] | Inchingolo et al. (2017)[29] | Forabosco et al. (2019)[30] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jadad score | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Quality of study | Low | Low | Low |

RESULTS

After the independent screening process by two reviewers, the inter-rater agreement was calculated by Cohen's Kappa coefficient as 0.82 indicative of almost perfect agreement.

Selection of studies

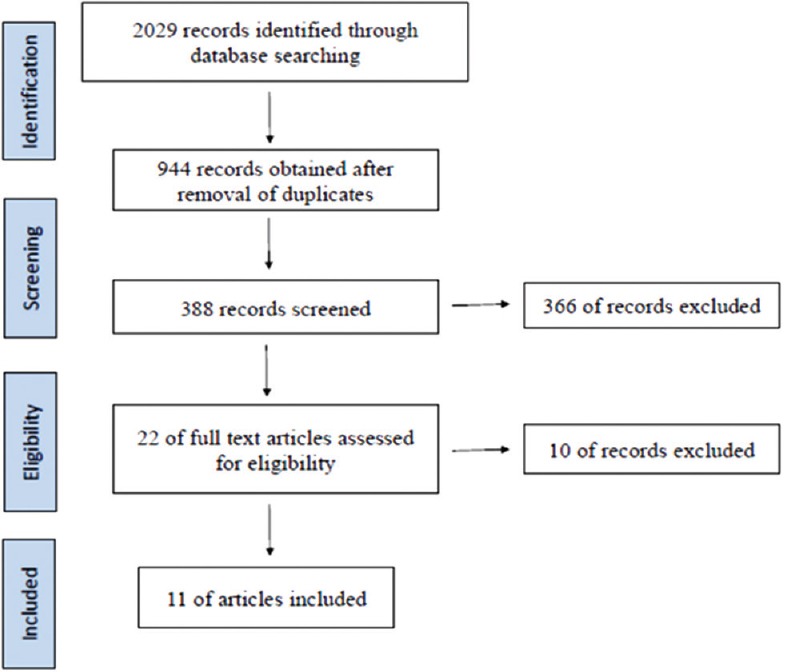

A total of 2029 studies were identified from the initial search through the databases. After removal of the duplicate records (n = 944), 388 articles were screened. Twenty-two full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility separately by two different authors (BL and DG), of which 11 were selected to be included in the final review [Figure 1 and Table 4].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection

Table 4.

List of excluded articles with reasons for exclusion

| Excluded articles | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Anitua et al., 2008[31] | Modified implant surface with growth factors |

| Mansour and Kim 2010[32] | Review article |

| Anitua 2001[33] | Case series |

| Gheno et al., 2014[34] | Case series |

| Neamat et al., 2017[35] | Case report |

| Sohn 2009[36] | Case series |

| Del Fabbro et al., 2009[37] | Coated implant surface with platelet rich growth factors |

| Huang et al., 2018[38] | Study does not use implants |

| Kim et al., 2011[39] | Full text in Chinese language, only abstract available in English |

| Javid et al., 2019[40] | Case series |

For all the included studies, the data were tabulated with information about the type of study, year of publication, duration of study, number of patients and implants, site of operation, the test and control group of each study, and the result obtained. Because of high heterogeneity present in the included studies with regard to outcome measures and study designs, a meta-analysis was not feasible. The included studies were divided into different categories depending on the outcome variables they measured [Tables 5-8].

Table 5.

Included studies: Bone gain around implant

| Study (year) | Type of study | Duration of study | No. of patients (implants) | Site of operation | Groups T: Test group C: Control group | Outcome (mean±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isler S et al (2018) | RCT | 12 months | 52 (52) | Not specified | T=CGF | T=1.63±1.00 mm |

| C=Collagen membrane (Bio Guide) | C=1.98±0.75 mm P=0.154 (NS) |

|||||

| Kim J et al (2014) | Retrospective study | 23.8 weeks | 10 (16) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF | T=8.236±2.88 mm, varying from 4.2-12.7 mm. P<0.05 (S) |

| No control group | ||||||

| S Manoj et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 10 (10) | Mandibular posterior | T=CGF | T=2.7 mm (mesial), 4.26 mm (distal), 2.3 mm (buccal) and 1.52 mm (lingual), P<0.05 (S) |

| No control group | ||||||

| Shetty M et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 20 | Maxillary posterior | T: CGF | T=1.932±2.22 (mesial), |

| C: Without CGF | 2.621±1.76 (distal), 3.864±1.51 (palatal), 4.417±2.01 (buccal) | |||||

| Yang L et al (2014) | Prospective study | 12 months | 20 (20) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF C=Bio-oss |

T=0.85±0.25mm C=0.35±0.25mm. P<0.05 (S) |

| Chen Y et al (2016) | Retrospective study | 2 years with follow up at 19.88 months | 16 (25) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF | T=9.21±0.66 mm. |

| No control group | P<0.05 (S) |

Table 8.

Included studies: Implant survival rate

| Study (year) | Type of study | Duration of study | No. of patients (implants) | Site of operation | Groups T: Test group C: Control group | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forabosco A et al (2019) | RCT | 12 months | 50 (106) | Maxillary posterior | T=xenograft + CGF | T=96.4% survival rate |

| C=xenograft alone | C=96.1% survival rate | |||||

| P>0.05 (NS) | ||||||

| Sohn D et al (2011) | Prospective study | 10 months | 53 (113) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF No control group |

T=98.2% survival rate |

| S Manoj et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 10 (10) | Mandibular posterior | T=CGF | T=100% |

| No control group | ||||||

| Shetty M et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 20 | Maxillary posterior | T: CGF | T=100% |

| C: Without CGF | C=100% | |||||

| Kim J et al (2014) | Retrospective study | 23.8 weeks | 10 (16) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF | T=100% |

| No control group | ||||||

| Chen Y et al (2016) | Retrospective study | 2 years with follow up at 19.88 months | 16 (25) | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF | T=100% |

| No control group |

Alveolar bone gain:

Six included studies depicted alveolar bone regeneration which could easily be identified through subsequent radiographs.[19,20,21,22,23,28] The bone gain was seen in various forms such as decrease in the vertical defect depth after 12 months as analyzed through computer software,[28] or simply as vertical bone gain by increase in bone height around the implants measured from specific points[19,20,21,22,23] or even as increase in bone width measured from implant shoulder to the apical point [Table 5].[22]

Implant stability quotient:

Two of the included studies measured implant stability quotient (ISQ).[24,25] Measurements were taken through resonance frequency analysis using the Osstell® device at the time of implant placement and at the 1st, 2nd, and 4th weeks[24] and at the 1st and 4th weeks after implant placement [Table 6].[25]

Table 6.

Included studies: Implant stability quotient measurement

| Study (year) | Type of study | Duration of study | No. of patients (implants) | Site of operation | Groups T: Test group C: Control group | Outcome (mean±SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koyuncu B et al (2019) | Prospective study | 4 weeks | 12 (24) | Mandible | T=CGF | T | C | |

| C=Without CGF | Immediate: | 67.75 ± 10.074 | 62.08 ± 7.489 | |||||

| 1st week: | 64.00 ± 10.081 | 62.67 ± 6.213 | ||||||

| 2nd week: | 63.00 ± 9.313 | 61.75 ± 7.162 | ||||||

| 4th week: | 67.00 ± 4.573 | 64.75 ± 5.065 | ||||||

| Pirpir C et al (2017) | Prospective study | 4 weeks | 12 (40) | Maxillary anterior and premolar region | T=CGF | T | C | |

| C=without CGF | Immediate: | 78.00 ± 2.828 | 75.75 ± 5.552 | |||||

| 1st week: | 79.40 ± 2.604 | 73.50 ± 5.226 | ||||||

| 2nd week: | 78.60 ± 3.136 | 73.45 ± 5.680 | ||||||

Bone density around implant threads:

The quality of bone formed around implant threads was assessed through radiographic analysis in two studies.[20,21] Another study employed the texture analysis of panoramic radiographs comparing the results obtained immediately after implant placement and after 8 months postoperatively as area under curve.[29] All the three studies concluded that CGF had a positive impact on the quality of bone formed around implants [Table 7].

Table 7.

Included studies: Bone density around implants

| Study (year) | Type of study | Duration of study | No. of patients (implants) | Site of operation | Groups T: Test group C: Control group | Outcome (mean±SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S Manoj et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 10 (10) | Mandibular posterior | T=CGF | Buccal: Lingual: Mesial: Distal: | Apical 2nd last thread 11.5 ± 559.55 175.5 ± 501.12 64.8 ± 352.89 -276 ± 520.95 P>0.05 (NS) |

Apical last thread thread 11.5 ± 559.55 175.5 ± 501.12 64.8 ± 352.89 -276 ± 520.95 P>0.05 (NS) |

Crestal 1st thread -580.9 ± 516.98 -295 ± 520.55 -475.2 ± 638.65 -552.3 ± 696.36 P<0.05 except in lingual (S) |

Crestal 2nd thread -801.9 ± 568.526 -371.8 ± 844.40 -360.5 ± 662.286 -513.5 ± 347.91 P<0.05 except in lingual and mesial (S) |

| No control group | ||||||||||

| Shetty M et al (2018) | Prospective study | 6 months | 20 | Maxillary posterior | T=CGF C= Without CGF |

First two threads | Last two threads | |||

| Buccal: Palatal: Mesial: Distal: | Test group 874.2 ± 338.84 1049.8 ± 434.12 593.3 ± 406.75 597.6 ± 315.38 | Control group 531.8 ± 151.12 652.5 ± 147.30 573.5 ± 150.83 485 ± 98.88 | Test group 1027.1 ± 325.89 1020.7 ± 249.16 838.5 ± 372.89 764.8 ± 340.62 | Control group 569.3 ± 167.36 655.3 ± 225.74 550.7 ± 81.34 472.6 ± 83.66 | ||||||

| Inchingolo et al (2017) | RCT | 8 months | 19 | Not specified | T=CGF C= Without CGF |

T= 0.82 AUC (Area Under Curve) C= 0.51-0.68 AUC (Area Under Curve) |

||||

Implant survival rate:

The survival rate of implants was measured in six of the included studies.[19,20,21,23,26,30] It was determined on the basis of number of complications during the follow-up period of the study. All the studies showed a high survival rate of almost 100% for implants placed along with CGF [Table 8].

DISCUSSION

The literature has a dearth of studies determining the effects of CGF and their potential role in implant dentistry. The present systematic review, being first of its kind, was conducted to contribute to the literature of evidence-based dentistry. The aim was to evaluate the clinical indications of CGF in all fields of dental implantology such as alveolar bone gain, improved bone quality around implants, enhancement of osseointegration, maxillary sinus augmentation, achievement of implant stability and implant survival rate.

CGF is now emerging as a viable treatment option due to various reasons. First, it has the capability for extended release of GFs, presenting a stronger effect on enhancement of wound healing around implants.[9] Second, it can be used alone or in combination with synthetic graft materials and facilitate osseointegration.[20,21] Third, it is easy to prepare and manipulate, and it is inexpensive.[41] The various outcomes discussed in the included studies show a positive trend toward the use of CGF in implant dentistry, although statistically significant conclusion cannot be drawn.

Alveolar bone regeneration

The primary aim to employ CGF for bone augmentation is to facilitate implant placement in a prosthetically driven position. Two studies[19,23] evaluated the vertical bone gain after sinus augmentation and reported positive outcomes. In both the studies, the technique used for sinus augmentation was different, but the graft material utilized was CGF. Sohn et al.[15] reported that CGF induced fast new bone formation in sinus augmentation. Furthermore, Sohn et al. proved in a clinical and histological evaluation that CGF, as a sole material, when inserted alone in sinus augmentation, induced rapid new bone formation in the new compartment under the elevated sinus membrane through the transcrestal and the lateral approaches.[26,42] As the result, bone regeneration along the implant body was evident radiographically and statistically significant.

Two other studies[21,28] revealed new alveolar bone formation for CGF group at the follow-up period of 12 months when compared to baseline values. Although the control group exhibited greater bone formation than the test group, the results were not statistically significant.

The study by Yang et al.[22] showed improved buccal bone width after 1 year of immediate implant placement. This has been attributed to the GFs in CGF which regulate wound healing, cell proliferation, and cell migration. Furthermore, another study revealed vertical bone gain on all four aspects (buccal, lingual, mesial, and distal) after immediate implant placement.[20] The jumping distance was filled with CGF because it provides for higher fibrin tensile strength and stability due to agglutination of fibrinogen, factor XIII and thrombin.[43] Furthermore, CGF acted as barrier membrane to accelerate soft tissue healing, and when mixed with bone graft, it could accelerate new bone formation.[20]

Implant stability quotient

Investigators have recommended that implants with ISQ <49 measured when placed should not be loaded during the 3-month healing period; implants with ISQ ≥54 may be loaded.[25] In some studies, there is a meaningful reduction in ISQ values measured sometime after the placement of implants.[44,45,46] Subsequently, there can be an increase in the value indicating greater stability. This increase or decrease is due to continuous alveolar bone remodeling during healing. In one of the included studies, an increase in the ISQ values was seen in the test group.[25] This suggested that CGF administration improved the implant primary stability by accelerating the osseointegration process. However, another study did not report any significant benefits of CGF on improving Implant stability.[24] Similarly, Ergun et al.[47] evaluated the effect of local application of PRP on the outcome of early loaded implants and found no statistically significant differences between ISQ values of PRP and non-PRP implants in the follow-up periods. However, Dohan Ehrenfest DM.[48] reported in a different experimental study that L-PRF usage during implant placement may enhance and increase the wound healing and early implant stability. Hence, while studies may indicate the use of CGF for implant stability, conclusive results can still not be drawn. Therefore, the use of CGF remains questionable with regard to implant stability.

Bone density around implants

The quality of bone formed around implants is indicative of implant osseointegration activity. In two studies,[20,21] bone density of the newly formed bone around implants was measured using CBCT in Hounsfield units. Both the studies revealed a significant increase in bone volume. The test group showed better statistically significant bone quality as compared to the control group which was attributed to the faster bone formation with CGF as observed by Kim et al.[6] Another study[29] employed textural analysis (an intensity based registration method that utilized the mean square error metric) to compensate any minor geometrical distortions between the two panoramic radiographs (preoperative and postoperative) of each patient. The results revealed that the CGF group exhibited higher values indicating increased osseointegration activity in the bone-to-implant region. Thus, the positive outcome obtained from the three studies could be attributed to the fact that CGF induced increased osteoblastic differentiation promoting early osseointegration.

Implant survival

The success of implant restorations is determined on the implant stability and absence of complications during the follow-up period. Six studies measured the implant survival rate.[19,20,21,23,26,30] Two studies[20,21] reported a 100% survival rate at 6 months. One retrospective study.[23] concluded that all implants were stable and pain free with 100% survival rate over a period of around 20 weeks. However, in a RCT,[30] two implants were lost in both, the test group and the control group, indicating a survival rate of 96.4% in test group and 96.1% in control. After maxillary sinus augmentation, a survival rate of 98.2% has been reported after 10 months in a study[19] because of membrane perforation occurring in a few cases. Very similar outcomes were also obtained in an investigation, in which autologous fibrin-rich blocks with CGFs without grafting materials were used in the sinus augmentation by lateral window approach.[49] Another study has demonstrated that both PRF and CGF preparations contain significant amounts of GFs capable of stimulating periosteal cell proliferation,[50] suggesting that PRF and CGF preparations act not only as a scaffolding material but also as a reservoir to deliver certain GFs at the site of application.[26]

Although statistically significant conclusions cannot be drawn, a higher recovery limit of CGF (due to its osseoinductive platelet factors and osseoconductive fibrin grid) can still be considered as a potential benefit for use in dental implantology.[51]

CONCLUSION

Based on limited studies with a limited statistical power, the present systematic review suggests that:

CGF might aid in obtaining vertical bone gain around implants, when used alone or in combination with allogenous and xenogenous grafts

The quality of new bone formed around implants is significantly improved with the use of CGF

There is lack of adequate studies evaluating the effect of CGF on implant stability, sinus floor augmentation, soft tissue healing and implant survival per se, although the preliminary data seems promising.

Future directions

The studies included in this review are limited, and thus, the clinical relevance of the measured outcomes remains questionable. Some may suggest the use of CGF in all fields of implant dentistry, but the potential benefits cannot yet be established. Well-designed RCTs with long-term follow-ups are required to substantiate the findings due to the present study limitations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sohn DS, Lee JS, Ahn MR, Shin HI. New bone formation in the maxillary sinus without bone grafts. Implant Dent. 2008;17:321–31. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e318182f01b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elias CN, Meirelle L. Improving osseointegration of dental implants. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7:241–56. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Öncü E, Bayram B, Kantarci A, Gülsever S, Alaaddinoǧlu EE. Positive effect of platelet rich fibrin on osseointegration. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016;21:e601–7. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intini G. The use of platelet-rich plasma in bone reconstruction therapy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4956–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacco L. International academy of implant prosthesis and osteoconnection. Lecture. 2006;4:12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim TH, Kim SH, Sándor GK, Kim YD. Comparison of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), and concentrated growth factor (CGF) in rabbit-skull defect healing. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59:550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senzel L, Gnatenko DV, Bahou WF. The platelet proteome. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:329–33. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832e9dc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao J, An N, Ouyang X. Quantification of growth factors in different platelet concentrates. Platelets. 2017;28:774–8. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1267338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin J, Wang L, Zheng L, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Yang T, et al. Concentrated growth factor promotes Schwann cell migration partly through the integrin β1-mediated activation of the focal adhesion kinase pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1363–70. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahin IO, Gokmenoglu C, Kara C. Effect of concentrated growth factor on osteoblast cell response. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;119:477–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borsani E, Bonazza V, Buffoli B, Cocchi MA, Castrezzati S, Scarì G, et al. Biological characterization and in vitro effects of human concentrated growth factor preparation: An innovative approach to tissue regeneration. Biol Med. 2015;7:5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuerst G, Gruber R, Tangl S, Sanroman F, Watzek G. Enhanced bone-to-implant contact by platelet-released growth factors in mandibular cortical bone: A histomorphometric study in minipigs. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:685–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weibrich G, Hansen T, Kleis W, Buch R, Hitzler WE. Effect of platelet concentration in platelet-rich plasma on peri-implant bone regeneration. Bone. 2004;34:665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemalata M, Jayanthi D, Vivekanand L, Shafi GA, Keerti V. Sandwich technique of socket preservation using concentrated growth factor and tricalcium phosphate and an immediate interim prosthesis with a natural tooth pontic: A case report. Int J Adv Health Sci. 2016;2:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohn DS, Moon JW, Moon YS, Park JS, Jung HS. The use of concentrated growth factor (CGF) for sinus augmentation. J Oral Implant. 2009;38:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javid K, Kurtzman GM, Nadi M, Javid H. Utilization of concentrated growth factor as a sole sinus augmentation material. Int J Growth Factors Stem Cells Dent. 2018;1:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane; 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 60 (updated July 2019) Available from: wwwtrainingcochraneorg/handbook . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 25]. Available from: http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp .

- 19.Kim JM, Sohn DS, Bae MS, Moon JW, Lee JH, Park IS. Flapless transcrestal sinus augmentation using hydrodynamic piezoelectric internal sinus elevation with autologous concentrated growth factors alone. Implant Dent. 2014;23:168–74. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manoj S, Punit J, Chethan H, Nivya J. A study to assess the bone formed around immediate postextraction implants grafted with concentrated growth factor in the mandibular posterior region. J Osseointegr. 2018;10:121–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shetty M, Kalra R, Hegde C. Maxillary sinus augmentation with concentrated growth factors: Radiographic evaluation. J Osseointegr. 2018;10:109–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Liu Z, Chen S, Xie C, Wu B. The study of the effect of Concentrated Growth Factors (CGF) on the new bone regeneration of immediate implant. Adv Mater Res. 2015;1088:500–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Cai Z, Zheng D, Lin P, Cai Y, Hong S, et al. Inlay osteotome sinus floor elevation with concentrated growth factor application and simultaneous short implant placement in severely atrophic maxilla. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep27348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özveri Koyuncu B, İçpınar Çelik K, Özden Yüce M, Günbay T, Çömlekoǧlu ME. The role of concentrated growth factor on implant stability: A preliminary study. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;(19):S2468–7855. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2019.08.009. 30208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirpir C, Yilmaz O, Candirli C, Balaban E. Evaluation of effectiveness of concentrated growth factor on osseointegration. Int J Implant Dent. 2017;3:7. doi: 10.1186/s40729-017-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohn DS, Heo JU, Kwak DH, Kim DE, Kim JM, Moon JW, et al. Bone regeneration in the maxillary sinus using an autologous fibrin-rich block with concentrated growth factors alone. Implant Dent. 2011;20:389–95. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e31822f7a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–2. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isler SC, Soysal F, Ceyhanlı T, Bakırarar B, Unsal B. Regenerative surgical treatment of peri-implantitis using either a collagen membrane or concentrated growth factor: A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20:703–12. doi: 10.1111/cid.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inchingolo F, Georgakopoulos P, Dipalma G, Tsantis S, Batani T, Cheno E, et al. Computer based textural evaluation of Concentrated Growth Factors (CGF) in osseointegration of oral implants in dental panoramic radiography. J Implant Adv Clin Dent. 2017;9:20–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forabosco A, Gheno E, Spinato S, Garuti G, Forabosco E, Consolo U. Concentrated growth factors in maxillary sinus floor augmentation: A preliminary clinical comparative evaluation. Int J Growth Factors Stem Cells Dent. 2018;1:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anitua E, Orive G, Aguirre JJ, Andía I. Clinical outcome of immediately loaded dental implants bioactivated with plasma rich in growth factors: A 5-year retrospective study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1168–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansour P, Kim P. Use of Concentrated Growth Factor (CGF) in implantology. Australasian Dental Practice. 2010;(33):163–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anitua E. The use of Plasma-Rich Growth Factors (PRGF) in oral surgery. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:487–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gheno E, Palermo A, Buffoli B, Rodella LF. The effectiveness of the use of xenogeneic bone blocks mixed with autologous Concentrated Growth Factors (CGF) in bone regeneration techniques: A case series. J Osseointegr. 2014;6:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neamat AH, Ali SM, Boskani SW, Mahmud PK. An indirect sinus floor elevation by using piezoelectric surgery with platelet-rich fibrin for sinus augmentation: A short surgical practice. Int J Case Rep Images. 2017;8:380–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohn D. The Effect of Concentrated Growth Factors on Ridge Augmentation Dental Inc. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Oct 13]. Available from: http://wwwykdentcomtw/pdf/cgf1pdf .

- 37.Del Fabbro M, Boggian C, Taschieri S. Immediate implant placement into fresh extraction sites with chronic periapical pathologic features combined with plasma rich in growth factors: Preliminary results of single-cohort study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2476–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang L, Zou R, He J, Ouyang K, Piao Z. Comparing osteogenic effects between concentrated growth factors and the acellular dermal matrix. Braz Oral Res. 2018;32:e29. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.vol32.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim J, Lee J, Park I. New bone formation using fibrin rich block with concentrated growth factors in maxillary sinus augmentation. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;37:278–86. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Javid K, Kurtzman GM, Nadi M, Javid H. Utilization of concentrated growth factor as a sole sinus augmentation. Int J Growth Factors Stem Cells Dent. 2018;1:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu R, Yan M, Chen S, Huang W, Wu D, Chen J. Effectiveness of platelet-rich fibrin as an adjunctive material to bone graft in maxillary sinus augmentation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2019/7267062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JM, Sohn DS, Heo JU, Park JS, Jung HS, Moon JW, et al. Minimally invasive sinus augmentation using ultrasonic piezoelectric vibration and hydraulic pressure: A multicenter retrospective study. Implant Dent. 2012;21:536–42. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3182746c3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tadić A, Puskar T, Petronijević B. Application of fibrin rich blocks with concentrated growth factors in pre-implant augmentation procedures. Med Pregl. 2014;67:177–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barewal RM, Oates TW, Meredith N, Cochran DL. Resonance frequency measurement of implant stability in vivo on implants with a sandblasted and acid-etched surface. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:641–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monov G, Fuerst G, Tepper G, Watzak G, Zechner W, Watzek G. The effect of platelet-rich plasma upon implant stability measured by resonance frequency analysis in the lower anterior mandibles. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:461–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huwiler MA, Pjetursson BE, Bosshardt DD, Salvi GE, Lang NP. Resonance frequency analysis in relation to jawbone characteristics and during early healing of implant installation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ergun G, Egilmez F, Cekic-Nagas I, Karaca IR, Bozkaya S. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on the outcome of early loaded dental implants: A three year follow-up study. J Oral Implantol. 2013;39:256–63. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, de Peppo GM, Doglioli P, Sammartino G. Slow release of growth factors and thrombospondin-1 in Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A gold standard to achieve for all surgical platelet concentrates technologies. Growth Factors. 2009;27:63–9. doi: 10.1080/08977190802636713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Misch CE, Perel ML, Wang HL, Sammartino G, Galindo-Moreno P, Trisi P, et al. Implant success, survival, and failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus Conference. Implant Dent. 2008;17:5–15. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3181676059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masuki H, Okudera T, Watanebe T, Suzuki M, Nishiyama K, Okudera H, et al. Growth factor and pro-inflammatory cytokine contents in platelet-rich plasma (PRP), plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF), advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF), and concentrated growth factors (CGF) Int J Implant Dent. 2016;2:19. doi: 10.1186/s40729-016-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prakash M, Ganapathy D, Mallikarjuna A. Knowledge awareness practice survey on awareness of concentrated growth factor among dentists. Drug Interv Today. 2018;11:730–3. [Google Scholar]