Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii has become increasingly resistant to leading antimicrobial agents since the 1970s. Increased resistance appears linked to armed conflicts, notably since widespread media stories amplified clinical reports in the wake of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. Antimicrobial resistance is usually assumed to arise through selection pressure exerted by antimicrobial treatment, particularly where treatment is inadequate, as in the case of low dosing, substandard antimicrobial agents, or shortened treatment course. Recently attention has focused on an emerging pathogen, multi-drug resistant A. baumannii (MDRAb). MDRAb gained media attention after being identified in American soldiers returning from Iraq and treated in US military facilities, where it was termed “Iraqibacter.” However, MDRAb is strongly associated in the literature with war injuries that are heavily contaminated by both environmental debris and shrapnel from weapons. Both may harbor substantial amounts of toxic heavy metals. Interestingly, heavy metals are known to also select for antimicrobial resistance. In this review we highlight the potential causes of antimicrobial resistance by heavy metals, with a focus on its emergence in A. baumanni in war zones.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, bacteria, heavy metals, heavy metal tolerance, antimicrobial resistance, conflict, weapons

Introduction

Overview on Wars and Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

Over the past decades, Acinetobacter baumannii has emerged as a major driver of hospital-acquired Multi-Drug Resistant (MDR) infections (Manchanda et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2016; Mancilla-Rojano et al., 2019). In the decades following the Second World War, A. baumannii became one of the most prevalent pathogens during wars in Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Iraq, causing multiple outbreaks of MDR infections among combat casualties (Tong, 1972; CDC, 2004; Scott et al., 2007; Dallo and Weitao, 2010). According to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), A. baumannii was the single most isolated Gram-negative bacterium from war wounds during the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the number one causative agent of bloodstream infections among the US soldiers (CDC, 2004; Fournier et al., 2006). Moreover, the emergence of MDR, Extensively-Drug Resistant (XDR), and Pan-Drug Resistant (PDR) A. baumannii coincided with specific worldwide tension points such as the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) (Matar et al., 1992), Iraq-Iran war (1980–1988), Afghanistan war (2001–2014), Iraq war (2003–2011), and recently the Syrian war (2011–Present) (Tong, 1972; CDC, 2004; Scott et al., 2007). Warfare is associated with significant heavy metal contamination of the environment, due to destruction of built infrastructure and consequent release of HM and direct contamination from exploded ordnance and leakage from unexploded ordnance. HM resistance in bacteria is associated with antimicrobial resistance. In this review we investigate how heavy metal resistance can lead to antimicrobial resistance with a view to illuminating the emergence A. baumannii’s increased resistance in war regions.

Living Systems and Heavy Metals

Heavy metals are a group of non-biodegradable metals and semi-metals (Metalloids) with high atomic weight and a density greater than 5 g/cm3. They have high electrical conductivity, malleability, metallic luster, and are capable of transferring electrons to form Cations (Jarup, 2003; Appenroth, 2010; Tchounwou et al., 2012). The major list of heavy metals includes: Cobalt (Co), Copper (Cu), Chromium (Cr), Zinc (Zn), Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Nickel (Ni), Antimony (Sb), Boron (B), Barium (Ba), Silver (Ag), and Tungsten (W) (ATSDR, 2011). Essential heavy metals are required in many biological processes at low concentrations, where they serve as cofactors for metalloenzymes. For example, Cu serves as an integral cofactor for cytochrome c oxidase and superoxide dismutase required in mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative stress (Osredkar and Šuštar, 2011). Zn plays role in DNA and RNA polymerases catalytic functions (Markov et al., 1999). Ni and Cr are essential for the activity of urease and cytochrome P450 enzymes (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012). On the other hand, non-essential heavy metals such as Hg, Pb, Cd, and As have no known biological functions and are toxic even at low concentrations (ATSDR, 2011; Singh R. et al., 2011; Tchounwou et al., 2012).

Sources of heavy metals include water, soil, and rocks. Furthermore, they are present in the Earth’s crust and date back to 4.5 billion years ago (Fru et al., 2016). The ecosystem is continuously flooded with high amounts of heavy metals due to volcanic eruptions, soil and rock erosion, industrial operations such as petroleum combustion and coal burning, in addition to agricultural activities that include pesticides and fungicides preparation (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Tchounwou et al., 2012; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014; Pal et al., 2017). Furthermore, heavy metals have been used in medical treatments as antimicrobial and anti-parasitic agents to treat skin infections and leishmaniasis respectively; anti-inflammatory compounds to treat itchiness, and in chemotherapy to treat cancer patients (Rizzotto, 2012; Ndagi et al., 2017; Pal et al., 2017).

Heavy Metals-Mediated Bacterial Toxicity

Essential and non-essential heavy metals become toxic when exceeding specific concentrations that vary between different metals (Appenroth, 2010). In bacteria, toxic levels of heavy metals can accumulate in cells, altering cellular processes, inducing structural modifications, and ultimately leading to heavy metals-mediated damage (Rouch et al., 1995). Mechanisms of heavy metals toxicity include the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that destroy essential biomolecules and sub-cellular organelles. When in excess, Pb, Cd, Cu, As, Ag, and Zn can induce oxidative damage in bacterial cells which leads to the production of free radicals that cause DNA damage and destabilize membranous integrity through lipid peroxidation (Szivák et al., 2009; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014; Williams et al., 2016). In addition, heavy metal ions can form complexes with thiol (R-SH)-containing enzymes to alter their functions. For example, Hg2+, Ag1+, and Cd2+ can form covalent bonds with sulfhydryl functional groups (R-SH) present in enzymatic active sites thereby inducing structural conformational changes, and thus blocking their function (Rouch et al., 1995). Furthermore, heavy metals can act as competitive inhibitors leading to the displacement of essential ions from their target sites (Ianeva, 2009; Jan et al., 2015).

Heavy Metals Resistance in Bacteria

Studies have shown that the presence of heavy metal resistance determinants is ubiquitous in almost all bacterial species (Silver and Phung le, 2005). For example, Farias et al. (2015), identified 35 bacterial strains from 8 different species harboring multi-metal resistant phenotypes from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Moreover, A. baumannii isolated from agricultural soil and sediments, fuel-contaminated soil, and sewage water, have shown to exhibit resistance to various metals such as Hg, Ag, and As (Dhakephalkar and Chopade, 1994; Lima de Silva et al., 2012; Farias et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015; El-Sayed, 2016; Huang et al., 2017). To date, six proposed mechanisms of heavy metal resistance have been elucidated: (1) Release of metal ions by extracellular barriers such as capsule, cell wall, and plasma membrane. (2) Extrusion of metal ions via efflux pumps or by diffusion. (3) Intracellular sequestration of metal ions. (4) Extracellular sequestration of metal ions. (5) Bio-transformation/detoxification of toxic metal ions. (6) Decreased sensitivity of cellular targets to metal ions. In general, heavy metal resistance-encoding genes are carried on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and transposons or on chromosomal DNA (Rouch et al., 1995; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Ianeva, 2009; Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). In the following sections, we will briefly discuss these mechanisms.

Extrusion of Metal Ions via Efflux Pumps or Diffusion

Efflux pumps are the most prevalent bacterial tools conferring heavy metals resistance. This is achieved via Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis and/or through an electrochemical gradient of protons (Ianeva, 2009). Five major efflux system families are present in microorganisms: (1) ATP Binding Cassettes (ABC) family. (2) Resistance, Nodulation, Cell Division (RND) family. (3) Small Multi-Drug Resistance (SMR) family. (4) Multi-Drug and Toxic Compounds Efflux (MATE) transporters. (5) Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) family. These pumps differ in their amino acid sequence, substrate specificity, and energy consumption in pumping metal ions. For example, ATP Binding Cassettes (ABC) play a role in the efflux of metal ions and antimicrobial agents driven by ATP hydrolysis, while RNDs and SMRs pump out metal cations and antimicrobial agents via Chemiosmosis/Proton motive force (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Kourtesi et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2017). Basal levels of efflux are usually not sufficient to confer heavy metal resistance in most bacterial species. However, changes in expression, either through mutations in promoter regions or efflux pump regulators, or inactivation of repressors, can lead to the over-expression of an efflux pump or confer resistance (Li et al., 2015; Blanco et al., 2016).

Intracellular Sequestration of Metal Ions

One important resistance mechanism involves intracellular metal ions sequestration upon binding to metal ions binding proteins [Metallothioneins (MTs), Glutathione (GSH), and Metallochaperones] (Ianeva, 2009). For example, Ni can complex with PO3–4, leading to its intracellular precipitation. Staphylococcus aureus, Providencia spp., Vibrio harveyi, Shewanella spp., and Bacillus spp., can precipitate Pb as phosphate salts (Levinson et al., 1996; Smeaton et al., 2009; Shin et al., 2012). Cd, Hg, Ag, Pb, and Zn can be trapped on cysteine-rich MT polypeptides that provide tolerance to high concentrations of heavy metals. For example, Synechococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Anabaena spp. tolerate high concentrations of heavy metals via MT trapping mechanisms (Olafson et al., 1988; Naik et al., 2012). Some bacteria use GSH as an alternative chelator to sequester metal ions. GSH scavenges and detoxifies metals via its thiol (R-SH) group. Lima et al. (2005), demonstrated the role of GSH in mediating tolerance to Cd in Rhizobium leguminosaru. Finally, metallochaperones like Cu chaperones (Cu1+ binding chaperone CusF, Cu1+, and Cu2+ periplasmic chaperones PcoC and PcoE) can bind, trap, and transport metal ions to metalloenzymes and thus, decrease their toxic effects and protect cellular compartments (Yang et al., 2010; Pal et al., 2017).

Extracellular Sequestration of Metal Ions

In addition to intracellular sequestration, extracellular sequestration of heavy metals is an additional mechanism conferring bacterial resistance. This strategy provides a “Pre-defense” strategy as it occurs outside the bacterial cell. It involves the secretion of extracellular chelating proteins such as siderophores, oxalateoxalate, phosphate, and sulfide. However, this mechanism is mainly active in static environments when constant concentrations of heavy metals are present (Cunningham et al., 1993; Rouch et al., 1995). For example, Streptomyces acidiscabies can sequester Ni via hydroxamate siderophores while Clostridium thermoaceticum use sulfide to sequester Cd (Cunningham et al., 1993; Dimkpa et al., 2008).

Bio-Transformation/Detoxification of Toxic Metal Ions

Enzymatic detoxification reduces metal toxicity, which is accomplished via oxidation, reduction, and methylation reactions (Rouch et al., 1995; Silver and Phung le, 2005). For example, Hg2+ is reduced to a less toxic Hg0 form via Mercury(II) reductase encoded by merA gene (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Pal et al., 2017). In addition, upon bacterial entry Cr6+ is reduced to Cr3+ while As3+ is oxidized to As5+ thus, decreasing their toxicity (Silver and Phung le, 2005). Interestingly, Pseudomonas spp., and Acinetobacter spp., induce Pb methylation to minimize its toxic effects. To date, Hg methylation has only been only documented in anaerobic bacteria (Parks et al., 2013; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014).

Decreased Sensitivity of Cellular Targets to Metal Ions

Reducing sensitivity of cellular targets to metal ions is a way to minimize heavy metals toxicity. This is fulfilled via several mechanisms: (1) Decreasing bacterial susceptibility to metals by introducing mutations in resistance genes or determinants, or increasing the expression of the metal target site. (2) Producing a more resistant form of the metal target site upon activating an alternative target encoded on a plasmid. (3) Repairing DNA damage upon the activation of an SOS response which is the case of Cr-induced DNA lesions (Frohlich, 2013; Maret, 2015).

Heavy Metals in Weapons

Explosives harbor huge amounts of Pb and Hg [Mercury(II) fulminate] (Navy U. S., 2008; Gebka et al., 2016). Zn, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Cr are used to coat bullets, missiles, gun barrels, and military vehicles (Audino, 2006; Casey, 2009). Ba, Sb, and B are weapon priming compounds, (Fitchett, 2019) and W is a kinetic bombardment due to its high density (19.3 g/cm3) (Rowlatt, 2014). In general, the use of heavy metals in weapons has increased since the end of World War II (Gebka et al., 2016).

Known Resistance Mechanisms to Heavy Metals Frequently Found in Ordnance

Copper (Cu)

Copper (Cu) exists in nature as a free metallic element or alternates between 2 oxidative states Cu1+ and Cu2+. In humans, Cu is essential for blood vessel elasticity, brain development, maintenance of immune responses, and neurotransmitter production (Dorsey et al., 2004; Copper Development Association, 2018). Excess concentrations of Cu lead to kidney and liver damage, neurological, and immune diseases (Dorsey et al., 2004). In wars, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Cr are heavily used as coatings for bullets, missiles, gun barrels, and in military vehicles (tanks, trucks, and aircrafts). This could increase exposure to Cu in wartime and might explain increased observation of A. baumannii in studies conducted in these settings (Davis et al., 2005; Calhoun et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2016). Extensive studies on Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas spp. reveal four Cu homeostatic resistance systems: Cue, Cus, Pco, and Cop. Cue and Cus are chromosomally encoded efflux systems while Pco and Cop are plasmid encoded resistance systems (Pal et al., 2017).

Cue System

The Cue system (Copper Efflux) is active at low Cu concentrations and under aerobic conditions. It consists of an inner membranous Cu1+ exporting P-type ATPase (CopA) and a periplasmic multi-Cu Oxidase (CueO). copA and cueO are activated by a cytoplasmic transcriptional Cu-responsive Regulon (CueR) upon sensing increased Cu concentrations (Hobman and Crossman, 2014; Delmar et al., 2015; Pal et al., 2017; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Resistance to Copper via the Cue and Cus systems. The Cue system is activated at low Cu concentrations and under aerobic conditions. Cu1+/Cu2+ enter the bacterial cells via non-specific porin proteins. CueR senses an increase in intracellular Cu concentrations and activates the expression of copA and cueO. Then, CopA translocate Cu1+ ions into the periplasm thus, protecting Cu-sensitive cytoplasmic compartments. In the periplasm, CueO oxidizes Cu1+ ions to the less toxic form Cu2+. The Cus efflux system is activated at high Cu concentrations, is strictly anaerobic, and pumps out Cu and Ag ions. Cu1+/Ag1+ ions enter the periplasm and induce the activation of CusS, which in turn phosphorylates and activates CusR. CusR induces the expression of cusCFBA operon. The protein products CusC, CusB, and CusA form a multi-Cu/Ag efflux pump (CusCBA) that pumps out Cu1+/Ag1+ ions after being transferred by the CusF metallochaperone (Franke et al., 2003; Delmar et al., 2015; Pal et al., 2017). Adapted and modified with permission from Pal et al. (2017).

Cus System

Unlike the Cue system, the Cus efflux system is active at high Cu concentrations, is strictly anaerobic, and pumps out Cu and Ag cations (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Singh S.K. et al., 2011; Delmar et al., 2015). It detoxifies Cu in the periplasmic compartment, unlike the Cue system that extrudes periplasmic and cytoplasmic Cu (Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). The Cus system consists of 4 genes forming the cusCFBA operon, which is regulated by a two-component regulatory system (CusS/CusR) (Franke et al., 2003; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Pal et al., 2017). CusS, a histidine kinase, is activated upon Cu/Ag stimulation, while CusR is a DNA-binding transcriptional activator that activates cusCFBA expression. CusC, CusB, and CusA form a multi-Cu/Ag efflux pump (CusCBA) that functions as a proton-ion antiporter. Cu1+/Ag1+ are transported to CusCBA via the periplasmic metallo-chaperone, CusF (Franke et al., 2003; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Pal et al., 2017). Cu resistance via the Cue and Cus systems are detailed in Figure 1.

Pco System

The E. coli-resistant Pco system (Plasmid-borne-Copper Resistance) found in Cu-fed pigs consists of two operons, pcoGFE, and pcoABCDRS that are encoded by a 9-10 gene cluster (Brown et al., 1995). Like the Cus system, the Pco system is regulated by a two-component regulatory system (PcoR/PcoS) (Brown et al., 1995; Pal et al., 2017). To actively function, the Pco system requires the action of CopA from the Cue system in addition to PcoA and PcoC. PcoA is a multi-Cu Oxidase that oxidizes Cu1+ to Cu2+, while PcoC is a periplasmic Cu-binding protein that acts as a chaperone which delivers Cu1+ to CopA during oxidation and to PcoD. PcoD is an inner membrane Cu transporter that is involved in Cu uptake. PcoB and PcoE are an outer membrane transporter and a metallo-chaperone, respectively (Figure 2; Lee et al., 2002; Bondarczuk and Piotrowska-Seget, 2013; Pal et al., 2017).

FIGURE 2.

Resistance to Copper via the Pco system. The Pco system consists of 2 operons, pcoGFE and pcoABCDRS in addition to a single gene pcoE. This system cannot function independently; it requires the activity of the Cue system and CopA in specific to induce resistance to Cu, which is heavily present in bullets, missiles, gun barrels, and in military vehicles. First, Cu1+/Cu2+ enter the bacterial cell via non-specific porin proteins. PcoD transports Cu1+ into the cytoplasm. Cu1+ is toxic in the cytoplasm; Apo-PcoA transports Cu1+ back to the periplasm and PcoR/PcoS senses an increase in Cu concentrations and in turn induces the expression of pcoGFE and pcoABCDRS. In addition to Apo-PcoA, the periplasmic Cu-chaperone PcoC transports Cu1+ to the periplasm, where CopA from the Cue system and PcoA oxidize Cu1+ to the less toxic form Cu2+. Cu2+ ions are expelled out via the PcoB efflux pump. Finally, PcoE is a metallochaperone, which is believed to provide initial bacterial resistance to Cu upon its entry through sequestering Cu1+ ions until the activation of the Pco system is fulfilled (Bondarczuk and Piotrowska-Seget, 2013; Pal et al., 2017). Adapted and modified with permission from Pal et al. (2017).

Cop System

The Cop system is encoded by a cluster of 6 plasmid-borne genes arranged in two operons, copABCD and copRS (Pal et al., 2017). copABCD and copRS are homologs of pcoABCDRS. The Cop determinants are genetically associated with the Cop system and have similar roles. copABCD is under the regulation of CopR/CopS. Protein products are associated with Cu sequestration in the periplasm and outer membrane (Bondarczuk and Piotrowska-Seget, 2013; Pal et al., 2017). In Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 and E. coli, Cu ions can be sequestered by CusF in the periplasm, exported by the RND-driven CusCBA efflux pump, or oxidized to Cu2+ (Nies, 2016).

Mercury (Hg)

Mercury (Hg) is released into the environment via geological and human activities such as soil and rock erosion, volcanic eruptions, mining, and fuel combustion (Tchounwou et al., 2012). In the wake of recent conflicts in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Afghanistan, the Middle East has become one of the most polluted regions with Hg (Gworek et al., 2017). This may have led to an increased bacterial tolerance to this metal. In humans, Hg has no biological role and at very low concentrations it is fatal, leading to brain, lung, and kidney failure (Risher and Rob, 1999).

Hg can access bacteria in 2 forms: organic (CH3-Hg+) and inorganic (Hg2+), both of which are toxic (Hobman and Crossman, 2014). Despite this toxicity, several bacterial species have developed resistance mechanisms to CH3-Hg+/Hg2+ via the mer operon, and are found mainly in war zone regions (Mirzaei et al., 2008; Pérez-Valdespino et al., 2013; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). The mer operon is present on plasmids and transposons and consists of a cluster of 8 genes merTPCAGBDE regulated by MerR (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). This operon encodes a chain of proteins that bind CH3-Hg+/Hg2+ and oxidize them, such as MerA [Mercury(II) Reductase], the key player in Hg2+ detoxification (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Bacterial resistance to mercury. The mer operon consists of a cluster up to 8 genes merTPCAGBDE. Upon the entry of the inorganic form of Hg (Hg2+) via non-specific porin proteins, the first protein to bind it is MerP, a small periplasmic chaperone. MerP transports Hg2+ to MerT, MerC or MerF, which are inner membranous mercuric ions-binding proteins that in turn transport Hg2+ to the cytoplasm. merT is the most prevalent gene within the mer operon as compared to merC and merF. In the cytoplasm, MerA detoxifies Hg2+ ions through reduction-catalyzed volatilization process to a non-toxic elemental form Hg0. This form is volatile at room temperature; it diffuses outside the membranes allowing the bacterial cell to escape Hg toxicity (Nies, 1999; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Boyd and Barkay, 2012; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). MerE is an inner membranous protein of unknown function (Silver and Phung le, 2005). In Gram-negative bacteria, the mer operon is regulated by MerR, which is in turn activated by increased Hg2+ levels in the cytoplasm. This induces the expression of the whole merTPCAGBDE operon (Boyd and Barkay, 2012; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). Resistance to the organic form of Hg (CH3-Hg+) is achieved by merB, which encodes an Organomercurcial Lyase (MerB) located in the cytoplasm. When CH3-Hg+ enter the cytoplasm via non-specific porin proteins, MerB cleaves the Mercury-Carbon bond and releases Hg2+ in the cytoplasm. At this point, Hg2+ is reduced to Hg0 that diffuse outside the bacterial cell (Nies, 1999; Boyd and Barkay, 2012; Hobman and Crossman, 2014; Pal et al., 2017). Adapted and modified with permission from Silver and Phung le (2005), Boyd and Barkay (2012) and Pal et al. (2017).

Arsenic (As)

Arsenic (As) is released into the environment from soil and rock erosion, volcanic eruptions, mining, and crops treated with pesticides and herbicides (Paez-Espino et al., 2009; Tchounwou et al., 2012). In 1918, two organic As compounds, Lewisite (C2H2AsCl3) and Adamsite (C12H9AsClN) were developed by the US army as chemical weapons; both are classified as potential bioterrorism agents by CDC (2013). Agent Blue, an arsenical mixture of cacodylic acid and sodium cacodylate was sprayed by the United States on crops as part of “resource deprivation” strategies in the Vietnam war beginning in 1962 (Radke et al., 2014). The use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Civil War has been confirmed by the United Nations. This resulted in increased bacterial resistance to As via oxidation, reduction, methylation, efflux, and intracellular sequestration on cysteine-rich peptides (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Paez-Espino et al., 2009), and was associated with detrimental health effects ranging from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, gastro-intestinal symptoms, hematological disorders, diabetes, neurological, and developmental anomalies (Chou et al., 2007; Tchounwou et al., 2012).

As exists in two chemical forms: inorganic and organic. Inorganic As occurs as pentavalent Arsenate (As5+), trivalent Arsenite (As3+), elemental Arsenic (As0), and Arsenide (As3–) with As3+ and As5+ being the most toxic inorganic forms and most prevalent in nature (Nies, 1999; Paez-Espino et al., 2009; Tchounwou et al., 2012). Organic As is less toxic than inorganic arsenicals (Chou et al., 2007). Bacterial resistance to As is mainly encoded by efflux via the ars operon, which can be plasmid or chromosomally driven, even though it can also be encoded by other genetic determinants such as arr genes and aox genes (Figure 4; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Paez-Espino et al., 2009).

FIGURE 4.

Bacterial resistance to arsenic. (As) enter the bacterial cell using Phosphate-Specific Transporters (Pst) and Type III Transporters (PiT) in the case of As5+ and Aquaglycerolporins in the case of As3+ (Paez-Espino et al., 2009). The ars operon harbors 3 co-transcribed core genes that confer resistance not only to As3+ and As5+, but also to Antimony (Sb3+). arsR encodes a Transcriptional Repressor, arsC encodes a Cytoplasmic Arsenate Reductase, and arsB encodes a membrane bound Arsenite Efflux Pump. Two additional genes may be present within the ars operon, arsA and arsD. The former encodes an intracellular ATPase which binds ArsB to form an ArsA-ArsB ATPase Efflux Pump, while the latter is a metallochaperone that binds and delivers As3+ and Sb3+ to ArsA-ArsB complex for efflux, in addition to its role as a trans-activating co-repressor of the ars operon along with ArsR (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Paez-Espino et al., 2009; Hobman and Crossman, 2014). Moreover, some microorganisms escape As toxicity by methylation thus, leading to the production of less toxic and volatile derivatives that diffuse outside the bacterial cell (Paez-Espino et al., 2009). Besides As toxicity, bacteria belonging to the Shewanella spp., Sulfurospirillum spp., Clostridium spp., and Bacillus spp., use As5+ as a final electron acceptor during anaerobic respiration by reducing it to As3+, while other bacteria use As3+ as an electron donor and oxidize it to As5+ during aerobic oxidation (Paez-Espino et al., 2009). The oxidation/reduction processes are mediated by the Respiratory Arsenate Reductase and Respiratory Arsenite Oxidase that are encoded by the arrAB operon and asoAB genes respectively (Silver and Phung le, 2005; Paez-Espino et al., 2009). Adapted and modified with permission from Paez-Espino et al. (2009).

Chromium (Cr)

Chromium (Cr) is the 7th most abundant heavy metal in the earth’s crust and is present in nature in several oxidation states ranging from divalent (+2) to hexavalent (+6) Cr3+ and Cr6+ are the most stable. While Cr3+ is naturally present in the environment, Cr6+ is mostly produced by industrial processes such as mining, electroplating, dye production, and leather tanning (Ahemad, 2014; Joutey et al., 2015; Pradhan et al., 2016). In weapons, Cr was initially used by the Chinese to coat metal weapons (Dunham, 2019). Nowadays, Cr is heavily used to coat gun barrels, where it is used as a bore protection (Audino, 2006). Moreover, Cr levels were highest in deciduous teeth from Iraqi patients during the Iraqi war, which highlights the heavily polluted Middle Eastern region with heavy metals (Savabieasfahani et al., 2016). The solubility and oxidizing potential of Cr6+ makes it 1000× more toxic to humans as compared to Cr3+, and this makes it a strong factor associated with nasal and bronchogenic carcinomas (International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC], 1990; Ahemad, 2014).

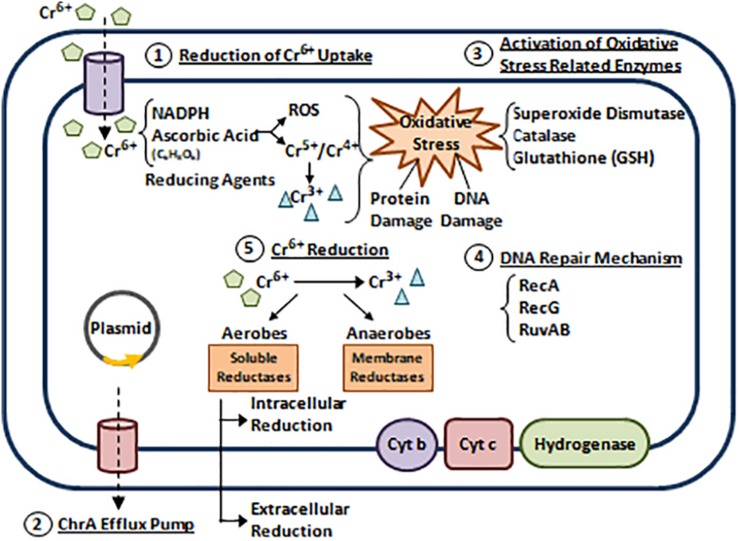

In bacteria, Cr has no metabolic role and thus, it is toxic in several species such as Pantoea spp., Aeromonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., and E. coli (Nies, 1999). However, many bacteria developed Cr resistance via 5 reported mechanisms that are mostly plasmid encoded (Camargo et al., 2005; Joutey et al., 2015). (1) Reduction of Cr6+ uptake. (2) Cr6+ efflux. (3) Activation of oxidative stress related enzymes. (4) Repairing DNA damage induced by Cr6+ and its derivatives. (5) Cr6+ reduction (Figure 5; Branco et al., 2008; Panda and Sarkar, 2012; Ahemad, 2014; Joutey et al., 2015; Pradhan et al., 2016).

FIGURE 5.

Bacterial resistance to chromium. Five Cr resistance mechanisms are reported (Camargo et al., 2005; Joutey et al., 2015). (1) Reduction of Cr6+ uptake. Cr6+ exists in the form of Oxyanions Chromate (CrO42–) and Dichromate (Cr2O72–). Bacterial cells can reduce Cr6+ uptake via the sulfate transport system (Nies, 1999; Ahemad, 2014; Joutey et al., 2015). (2) Cr6+ efflux. Studies reveal that P. aeruginosa and Alcaligenes eutrophus can extrude Cr6+ by active efflux through ChrA (Chromate) pump (Collard et al., 1994; Alvarez et al., 1999). In 2008, a plasmid encoded operon (chrBACF) was identified in Ochrobactrum tritici responsible for Cr efflux, where chrB and chrA are the main genes involved (Branco et al., 2008). (3) Activation of oxidative stress related enzymes. When Cr6+ enter the bacterial cell, it interacts with reducing agents such as Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) and Ascorbic Acid to produce free radicals and unstable Cr intermediates (Cr4+ and Cr5+) that are further reduced to Cr3+. End products of these reactions cause oxidative stress leading to protein and DNA damage. This induces the up-regulation of antioxidants enzymes that scavenge ROS and protect cellular compartments (Ahemad, 2014; Joutey et al., 2015; Pradhan et al., 2016). (4) Repairing DNA damage induced by Cr6+ and its derivatives. This is achieved via SOS response activation. Several studies highlight the roles of RuvAB, RecA, and RecG (helicases) in mediating Cr resistance through repairing Cr6+ induced DNA damage (Miranda et al., 2005; Morais et al., 2011). (5) Cr6+ reduction. Cr6+ can be reduced aerobically or anaerobically to a less toxic form Cr3+. Aerobic reduction uses cytoplasmic soluble reductases and NADPH, while anaerobic reduction uses membrane reductases belonging to the electron transport chain (cytochromes b and c, and hydrogenases) (Morais et al., 2011; Ahemad, 2014; Joutey et al., 2015). Adapted and modified with permission from Ahemad (2014).

Lead (Pb)

Lead (Pb) is predominantly released into the environment from human activities such as manufacturing pipes, X-ray shields, lead-acid storage batteries, munitions, and bullets (Abadin et al., 2007; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). It exists in two main oxidative states (Pb2+ and Pb4+). In addition to bullets, Pb is present in explosives that ignite gunpowder. It usually vaporizes upon firing and thus, Pb fumes and dust are inhaled, leading to brain damage, anemia, and high blood pressure (Abadin et al., 2007; Dermatas and Chrysochoou, 2007).

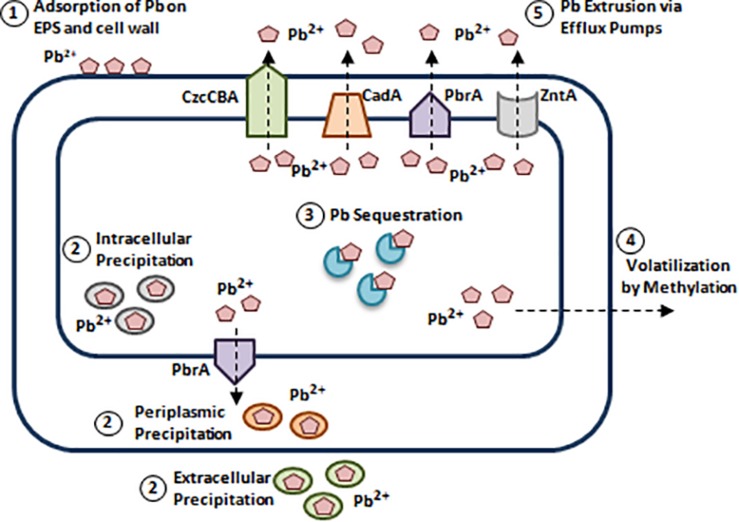

Pb toxicity involves inducing cellular damage through ROS formation, disrupting enzymatic conformations, and interfering in calcium (Ca) metabolism (Tchounwou et al., 2012). Due to the widespread Pb contamination, bacteria have developed Pb resistance mechanisms (Levinson et al., 1996; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). (1) Adsorption of Pb on EPS and bacterial cell wall. (2) Reducing Pb accumulation via intracellular and extracellular precipitation. (3) Pb sequestration via intracellular proteins. (4) Pb detoxification via methylation. (5) Pb extrusion via efflux pumps (Figure 6; Levinson et al., 1996; Silver and Phung le, 2005; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014; Subramanian, 2018).

FIGURE 6.

Bacterial resistance to lead. Bacterial species such as Pseudomonas spp., and Acinetobacter spp., developed Pb resistance mechanisms. (1) Adsorption of Pb on EPS and bacterial cell wall. Structures like cell wall and extracellular polymers can adsorb Pb2+ due to the presence of negatively charged functional groups [Carboxyl (C(= O)OH), Hydroxyl (R-OH), and Phosphate groups (PO3–4)] (Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). (2) Reducing Pb accumulation via intracellular and extracellular precipitation. S. aureus, Providencia spp., and Pseudomonas spp., can precipitate Pb intracellularly in the form of Lead(II) phosphate [Pb3(PO4)2], while in Citrobacter freundii, extracellular Pb precipitation is mediated by phosphatase. In addition to intracellular and extracellular precipitation, periplasmic precipitation of Pb involves adsorption to polymers present in the cell wall (al-Aoukaty et al., 1991; Levinson et al., 1996; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). (3) Pb sequestration via intracellular proteins. Pb binding-MTs were reported in Pb resistant P. aeruginosa strain WI-1 and Providencia vermicola strain SJ2A. This is mediated by a plasmid-borne MT encoding gene, bmtA responsible for Pb sequestration (Naik et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2017). (4) Pb detoxification via methylation. Methylation of Pb is documented in Acinetobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., Aeromonas spp., and others. Arctic marine bacteria convert inorganic Pb to tri-methyl-lead (C3H9Pb), while Acinetobacter spp., convert it to tetra-methyl derivatives (Wong et al., 1975; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). (5) Pb extrusion via efflux pumps. Pb efflux is mediated by P-type ATPases such as, CadA of S. aureus, ZntA of E. coli, and PbrA of Cupriavidus metallidurans and to a lower extent by RND/CBA chemiosmotic transporters. CadA, ZntA, and PbrA are homologous P-type ATPases that can pump out Pb2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ (Leedjärv et al., 2007; Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget, 2014). Adapted and modified with permission from Jaroslawiecka and Piotrowska-Seget (2014).

Association Between Heavy Metals and AMR

Worldwide concerns about heavy metal contamination, resistance, and its ability to induce AMR are increasing. These concerns are associated with the heavy metals used in manufacturing weapons; most heavy metals are non-biodegradable and persist in the environment. Moreover, many bacterial species evolved resistance mechanisms to combat metals toxicity (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Yu et al., 2017). These mechanisms are encoded by resistant genes to heavy metals and antimicrobial agents that are physically linked on mobile genetic elements (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Yu et al., 2017). More importantly, heavy metals can induce selective pressure on microbial populations leading to antimicrobial resistance through a mechanism called “co-selection” which occurs via 3 major ways (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012).

Co-resistance

Co-resistance occurs when genes encoding resistance to heavy metals and antimicrobial agents are physically linked/located in close proximity to each other on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, genomic islands (GIs), transposons, or integrons (Trevors and Oddie, 1986; Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Yu et al., 2017). For example, in Cu-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated from pigs, tcrB and genes encoding resistance to erythromycin and vancomycin are encoded on the same conjugative plasmid (Hasman and Aarestrup, 2002; Silveira et al., 2014). Moreover, in Serratia marcescens, plasmid-borne resistance to chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and tetracycline is genetically linked to As, Cu, Hg, and Ag resistance genes (Gilmour et al., 2004). Interestingly, Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) analysis in Salmonella typhi reveal a genetic association between Hg resistance and several unrelated antimicrobial agents resistance genes (chloramphenicol, ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfonamide, and trimethoprim) (Wireman et al., 1997).

Cross-Resistance

Cross-resistance occurs when one resistance mechanism confers resistance to heavy metals and antimicrobial agents simultaneously. This is mainly achieved via multi-drug efflux pumps (Baker-Austin et al., 2006; Pal et al., 2017). The MdrL efflux pump in Listeria monocytogenes encodes resistance to Zn, Co, Cr, erythromycin, josamycin, and clindamycin (Mata et al., 2000). Moreover, the DsbA-DsbB (Disulfide Bond) multi-drug efflux system in Burkholderia cepacia induces cross-resistance to β-lactams, kanamycin, erythromycin, novobiocin, ofloxacin, and Zn2+ and Cd2+ metal ions (Hayashi et al., 2000). In addition, resistance to antimicrobial agents, Co, and Cu is mediated via the CmeABC multi-drug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni (Lin et al., 2002).

Co-regulatory Resistance

Co-regulation is the least common mechanism of co-selection. It is fulfilled when resistant genes to antimicrobial agents and heavy metals are controlled by a mutual regulatory protein (Pal et al., 2017). A very well characterized co-regulatory resistance system is the CzcS-CzcR two component regulatory system of P. aeruginosa. This system induces resistance to Zn2+, Cd2+, and Co2+ by activating the expression of czcCBA (Cobalt Zinc Cadmium) efflux pump and to the carbapenem imipenem by suppressing expression of the OprD porin encoding gene (Perron et al., 2004).

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Heavy Metal Resistance

Many reports highlighted the importance of WGS as an effective tool to detect genome-wide modifications and the emergence of heavy metal resistance genes. Nowadays, it is feasible to assess the entire bacterial genome at low costs and in a timely manner, making it an ideal method for AMR surveillance. Therefore, WGS provides a practical solution to evaluate genomes and determine resistant genes for compounds that are not frequently assessed. Moreover, this tool allows scientists to discover novel resistance mechanisms and provides valuable information to researchers and clinicians in antimicrobial prescriptions (Khromykh and Solomon, 2015; Jagadeesan et al., 2019). For example, the arsenic resistance cassette, arsRCDAB, present on a class 1 integron and mobilized on a conjugative plasmid was detected in two Salmonella enterica isolates from Singapore with high tolerance to arsenate (Wilson et al., 2019). Moreover, heavy metal resistant genes to Manganese (Mn2+) and Cd2+ in addition to exopolysaccharides production (EPS) were documented upon WGS analysis in Pseudaminobacter manganicus isolated from a manganese mine. This aspect sheds light on metal removal/adsorption and reflects bioremediation capabilities in contaminated regions (Xia et al., 2018). In A. baumannii, WGS analysis revealed the role of two integrases in the excision and circularization of heavy metal resistance (GIs) in E. coli (Al-Jabri et al., 2018). Bacterial WGS and typing databases such as BacWGSTdb (PMID: 26433226)1 serve as easy, rapid, powerful, and convenient tools to assess AMR and provide valuable information to WGS analysis and daily use in the clinical microbiology laboratories (Ruan and Feng, 2016). Moreover, “BacMet: Antibacterial Biocide and Metal Resistance Genes Database” provides an accurate and high quality resource of bacterial genes associated with heavy metal resistance present in literature2. These available databases serve as important tools to help understand bacterial resistance mechanisms to heavy metals by linking various factors and parameters involved.

Conclusion

The reason for the rapid emergence of drug resistant A. baumannii in war-wounded patients remains unclear. Heavy metal contaminated areas may be driving the increase in antimicrobial resistance. This may explain an observed increase in bacterial resistance to both heavy metals and antimicrobial agents and lead to the development of novel mechanisms of resistance. The role of this pathway in A. baumannii is poorly understood.

Until now antimicrobial resistance has been largely attributed to poor antimicrobial stewardship in humans and in animals. The mechanisms described above, whereby heavy metals may produce antimicrobial resistance in their absence, identifies a potential pathway driving global antimicrobial resistance that would not be addressed through improved antimicrobial stewardship. This pathway would be facilitated in wartime, and could explain the emergence of previously little reported pathogens as possible amplification points along this pathway.

Further research into the role of heavy metals driving antimicrobial resistance, its influence in war zones, and the contribution of A. baumannii as a reservoir, are therefore warranted given the implications for addressing the global AMR crisis.

Author Contributions

AGA, WB, AN, L-PH, MZ, and PH contributed to reviewing the literature and the write up of the manuscript. V-KN, HL, OD, GA-S, MM, NK, AA, CK, and GM contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding

This project was part of the War, AntiMicrobial Resistance, and Acinetobacter baumannii (WAMRA) consortium and was supported by the Medical Practice Plan, Faculty of Medicine, American University of Beirut.

References

- Abadin H., Ashizawa A., Stevens Y.-W., ATSDR, Llados F., Diamond G., et al. (2007). Toxic Substances Portal- Lead. Atlanta: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24049859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas S. Z., Rafatullah M., Hossain K., Ismail N., Tajarudin H. A., Abdul Khalil H. P. S. (2017). A review on mechanism and future perspectives of cadmium-resistant bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 15 243–262. 10.1007/s13762-017-1400-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M. (2014). Bacterial mechanisms for Cr(VI) resistance and reduction: an overview and recent advances. Folia Microbiol. 59 321–332. 10.1007/s12223-014-0304-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Aoukaty A., Appanna V. D., Huang J. (1991). Exocellular and intracellular accumulation of lead in Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 is mediated by the phosphate content of the growth medium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 67 283–290. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jabri Z., Zamudio R., Horvath-Papp E., Ralph J. D., Al-Muharrami Z., Rajakumar K., et al. (2018). Integrase-controlled excision of metal-resistance genomic islands in Acinetobacter baumannii. Genes 9:E366. 10.3390/genes9070366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez A. H., Moreno-Sanchez R., Cervantes C. (1999). Chromate efflux by means of the ChrA chromate resistance protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181 7398–7400. 10.1128/jb.181.23.7398-7400.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenroth K.-J. (2010). What are “heavy metals” in plant sciences? Acta Physiol. Plant. 32 615–619. 10.1007/s11738-009-0455-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR (2011). Toxic Substances Portal. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ (accessed March 22, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Audino M. J. (2006). Use of Electroplated Chromium in Gun Barrels. Washington, DC: Army Benet Laboratories. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C., Wright M. S., Stepanauskas R., McArthur J. V. (2006). Co-selection of antibiotic and metal resistance. Trends Microbiol. 14 176–182. 10.1016/j.tim.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P., Hernando-Amado S., Reales-Calderon J. A., Corona F., Lira F., Alcalde-Rico M., et al. (2016). Bacterial multidrug efflux pumps: much more than antibiotic resistance determinants. Microorganisms 4:E14. 10.3390/microorganisms4010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarczuk K., Piotrowska-Seget Z. (2013). Molecular basis of active copper resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 29 397–405. 10.1007/s10565-013-9262-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd E. S., Barkay T. (2012). The mercury resistance operon: from an origin in a geothermal environment to an efficient detoxification machine. Front. Microbiol. 3:349. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco R., Chung A. P., Johnston T., Gurel V., Morais P., Zhitkovich A. (2008). The chromate-inducible chrBACF operon from the transposable element TnOtChr confers resistance to chromium(VI) and superoxide. J. Bacteriol. 190 6996–7003. 10.1128/JB.00289-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. L., Barrett S. R., Camakaris J., Lee B. T., Rouch D. A. (1995). Molecular genetics and transport analysis of the copper-resistance determinant (pco) from Escherichia coli plasmid pRJ1004. Mol. Microbiol. 17 1153–1166. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun J. H., Murray C. K., Manring M. M. (2008). Multidrug-resistant organisms in military wounds from Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466 1356–1362. 10.1007/s11999-008-0212-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo F. A. O., Okeke B. C., Bento F. M., Frankenberger W. T. (2005). Diversity of chromium-resistant bacteria isolated from soils contaminated with dichromate. Appl. Soil Ecol. 29 193–202. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey T. (2009). US Military Targets Toxic Enemy #1: Hexavalent Chromium. Available at: https://cleantechnica.com/2009/07/04/us-military-targets-toxic-enemy-1-hexavalent-chromium/ (accessed July 4, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2004). Acinetobacter baumannii infections among patients at military medical facilities treating injured U.S. service members, 2002-2004. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53 1063–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2013). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. Lewisite (L): Blister Agent. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ershdb/emergencyresponsecard_29750006.html (accessed April 01, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Chou S., Harper C., ATSDR, Ingerman L., Llados F., Colman J., et al. (2007). Toxic Substances Portal- Arsenic. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Collard J. M., Corbisier P., Diels L., Dong Q., Jeanthon C., Mergeay M., et al. (1994). Plasmids for heavy metal resistance in Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34: mechanisms and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 14 405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copper Development Association (2018). Benefits of Copper. Available at: https://copperalliance.org.uk/benefits-copper/health/ (accessed March 22, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D. P., Leon L., Lundie J. R. (1993). Precipitation of cadmium by Clostridium thernoaceticum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 7–14. 10.1128/aem.59.1.7-14.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallo S. F., Weitao T. (2010). Insights into acinetobacter war-wound infections, biofilms, and control. Adv. Skin Wound Care 23 169–174. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000363527.08501.a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. A., Moran K. A., McAllister C. K., Gray P. J. (2005). Multidrug-resistant acinetobacter extremity infections in soldiers. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11 1218–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmar J. A., Su C.-C., Yu E. W. (2015). Heavy metal transport by the CusCFBA efflux system. Protein Sci. 24 1720–1736. 10.1002/pro.2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatas D., Chrysochoou M. (2007). Lead particle size and its association with firing conditions and range maintenance: implications for treatment. Environ. Geochem. Health 29 347–355. 10.1007/s10653-007-9092-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakephalkar P. K., Chopade B. A. (1994). High levels of multiple metal resistance and its correlation to antibiotic resistance in environmental isolates of acinetobacter. Biometals 7 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa C., Svatos A., Merten D., Buchel G., Kothe E. (2008). Hydroxamate siderophores produced by Streptomyces acidiscabies E13 bind nickel and promote growth in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) under nickel stress. Can. J. Microbiol. 54 163–172. 10.1139/w07-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey A., Lisa I., Steven S. (2004). Toxic Substances Portal - Copper. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=206&tid=37 (accessed September 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Dunham W. (2019). Scientists Solve Mystery of Pristine Weapons of China’s Terracotta Warriors. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-science-warriors/scientists-solve-mystery-of-pristine-weapons-of-chinas-terracotta-warriors-idUSKCN1RG2HT (accessed April 5, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed M. H. (2016). Multiple heavy metal and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii strain HAF ⋅⋅C 13 isolated from industrial effluents. Am. J. Microbiol. Res. 4 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Farias P., Espirito Santo C., Branco R., Francisco R., Santos S., Hansen L., et al. (2015). Natural hot spots for gain of multiple resistances: arsenic and antibiotic resistances in heterotrophic, aerobic bacteria from marine hydrothermal vent fields. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 2534–2543. 10.1128/AEM.03240-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett B. (2019). Priming Compounds and Primers Introduction. Bev Fitchett’s guns magazine. Available at: https://www.bevfitchett.us/ballistics/priming-compounds-and-primers-introduction.html [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P. E., Richet H., Weinstein R. A. (2006). The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 692–699. 10.1086/500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke S., Grass G., Rensing C., Nies D. H. (2003). Molecular analysis of the copper-transporting efflux system CusCFBA of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185 3804–3812. 10.1128/jb.185.13.3804-3812.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich E. (2013). Cellular targets and mechanisms in the cytotoxic action of non-biodegradable engineered nanoparticles. Curr. Drug Metab. 14 976–988. 10.2174/1389200211314090004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fru E. C., Nathalie R., Camille P., Stefan L., Per A., Dominik W., et al. (2016). Cu isotopes in marine black shales record the great oxidation event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 4941–4946. 10.1073/pnas.1523544113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebka K., Beldowski J., Beldowska M. (2016). The impact of military activities on the concentration of mercury in soils of military training grounds and marine sediments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23 23103–23113. 10.1007/s11356-016-7436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour M. W., Thomson N. R., Sanders M., Parkhill J., Taylor D. E. (2004). The complete nucleotide sequence of the resistance plasmid R478: defining the backbone components of incompatibility group H conjugative plasmids through comparative genomics. Plasmid 52 182–202. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gworek B., Dmuchowski W., Baczewska A. H., Bragoszewska P., Bemowska-Kalabun O., Wrzosek-Jakubowska J. (2017). Air contamination by mercury, emissions and transformations-a review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 228:123. 10.1007/s11270-017-3311-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasman H., Aarestrup F. M. (2002). tcrB, a gene conferring transferable copper resistance in Enterococcus faecium: occurrence, transferability, and linkage to macrolide and glycopeptide resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 1410–1416. 10.1128/aac.46.5.1410-1416.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S., Abe M., Kimoto M., Furukawa S., Nakazawa T. (2000). The dsbA-dsbB disulfide bond formation system of Burkholderia cepacia is involved in the production of protease and alkaline phosphatase, motility, metal resistance, and multi-drug resistance. Microbiol. Immunol. 44 41–50. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobman J. L., Crossman L. C. (2014). Bacterial antimicrobial metal ion resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 64(Pt 5), 471–497. 10.1099/jmm.0.023036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Lu Q., Wang J., Chen X., Mao X., He Z. (2017). Inhibition of the bioavailability of heavy metals in sewage sludge biochar by adding two stabilizers. PLoS One 12:e0183617. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianeva O. D. (2009). [Mechanisms of bacteria resistance to heavy metals]. Mikrobiol. Z 71 54–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC] (1990). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Chromium, Nickel and Welding. Lyon: IARC. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesan B., Gerner-Smidt P., Allard M. W., Leuillet S., Winkler A., Xiao Y., et al. (2019). The use of next generation sequencing for improving food safety: translation into practice. Food Microbiol. 79 96–115. 10.1016/j.fm.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A. T., Azam M., Siddiqui K., Ali A., Choi I., Haq Q. M. R. (2015). Heavy metals and human health: mechanistic insight into toxicity and counter defense system of antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 29592–29630. 10.3390/ijms161226183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroslawiecka A., Piotrowska-Seget Z. (2014). Lead resistance in micro-organisms. Microbiology 160(Pt 1), 12–25. 10.1099/mic.0.070284-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarup L. (2003). Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 68 167–182. 10.1093/bmb/ldg032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutey N. T., Sayel H., Bahafid W., El Ghachtouli N. (2015). Mechanisms of hexavalent chromium resistance and removal by microorganisms. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 233 45–69. 10.1007/978-3-319-10479-9_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khromykh A., Solomon B. D. (2015). The benefits of whole-genome sequencing now and in the future. Mol. Syndromol. 6 108–109. 10.1159/000438732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. Y., Yoon J. K., Kim T. S., Yang J. E., Owens G., Kim K. R. (2015). Bioavailability of heavy metals in soils: definitions and practical implementation–a critical review. Environ. Geochem. Health 37 1041–1061. 10.1007/s10653-015-9695-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourtesi C., Ball A. R., Huang Y.-Y., Jachak S. M., Vera D. M., Khondkar P., et al. (2013). Microbial efflux systems and inhibitors: approaches to drug discovery and the challenge of clinical implementation. Open Micrbiol. J. 7 34–52. 10.2174/1874285801307010034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. M., Grass G., Rensing C., Barrett S. R., Yates C. J., Stoyanov J. V., et al. (2002). The Pco proteins are involved in periplasmic copper handling in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295 616–620. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00726-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedjärv A., Ivask A., Virta M. (2007). Interplay of different transporters in the mediation of divalent heavy metal resistance in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 190 2680–2689. 10.1128/jb.01494-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson H. S., Mahler I., Blackwelder P., Hood T. (1996). Lead resistance and sensitivity in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 145 421–425. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Z., Plesiat P., Nikaido H. (2015). The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28 337–418. 10.1128/CMR.00117-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A. I. G., Corticeiro S. C., de Almeida Paula Figueira E. M. (2005). Glutathione-Mediated Cadmium Sequestration in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lima de Silva A. A., de Carvalho M. A., de Souza S. A., Dias P. M., da Silva Filho R. G., de Meirelles Saramago C. S., et al. (2012). Heavy metal tolerance (Cr, Ag AND Hg) in bacteria isolated from sewage. Braz. J. Microbiol. 43 1620–1631. 10.1590/S1517-838220120004000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Michel L. O., Zhang Q. (2002). CmeABC functions as a multidrug efflux system in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 2124–2131. 10.1128/aac.46.7.2124-2131.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda V., Sanchaita S., Singh N. (2010). Multidrug resistant acinetobacter. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2 291–304. 10.4103/0974-777X.68538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancilla-Rojano J., Castro-Jaimes S., Ochoa S. A., Bobadilla Del Valle M., Luna-Pineda V. M., Bustos P., et al. (2019). Whole-genome sequences of five Acinetobacter baumannii strains from a child with leukemia M2. Front. Microbiol. 10:132. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. (2015). Analyzing free zinc(II) ion concentrations in cell biology with fluorescent chelating molecules. Metallomics 7 202–211. 10.1039/c4mt00230j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markov D., Naryshkina T., Mustaev A., Severinov K. (1999). A zinc-binding site in the largest subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase is involved in enzyme assembly. Genes Dev. 13 2439–2448. 10.1101/gad.13.18.2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M. T., Baquero F., Perez-Diaz J. C. (2000). A multidrug efflux transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187 185–188. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matar G. M., Gay E., Cooksey R. C., Elliott J. A., Heneine W. M., Uwaydah M. M., et al. (1992). Identification of an epidemic strain of Acinetobacter baumannii using electrophoretic typing methods. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8 9–14. 10.1007/bf02427385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda A. T., Gonzalez M. V., Gonzalez G., Vargas E., Campos-Garcia J., Cervantes C. (2005). Involvement of DNA helicases in chromate resistance by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mutat. Res. 578 202–209. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei N., Kafilzadeh F., Kargar M. (2008). Isolation and identification of mercury resistant bacteria from Kor river, Iran. J. Biol. Sci. 8 935–939. 10.3923/jbs.2008.935.939 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morais P. V., Branco R., Francisco R. (2011). Chromium resistance strategies and toxicity: what makes Ochrobactrum tritici 5bvl1 a strain highly resistant. Biometals 24 401–410. 10.1007/s10534-011-9446-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik M. M., Pandey A., Dubey S. K. (2012). Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain WI-1 from Mandovi estuary possesses metallothionein to alleviate lead toxicity and promotes plant growth. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 79 129–133. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navy U. S. (2008). Hawaii Range Complex: Environmental Impact Statement. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Ndagi U., Mhlongo N., Soliman M. E. (2017). Metal complexes in cancer therapy – an update from drug design perspective. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 11 599–616. 10.2147/DDDT.S119488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies D. H. (1999). Microbial heavy-metal resistance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51 730–750. 10.1007/s002530051457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies D. H. (2016). The biological chemistry of the transition metal “transportome” of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics 8 481–507. 10.1039/c5mt00320b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafson R. W., McCubbin W. D., Kay C. M. (1988). Primary- and secondary-structural analysis of a unique prokaryotic metallothionein from a Synechococcus sp. cyanobacterium. Biochem. J. 251 691–699. 10.1042/bj2510691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osredkar J., Šuštar N. (2011). Copper and zinc, biological role and significance of copper/zinc imbalance. J. Clin. Toxicol. S3-001, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Espino D., Tamames J., de Lorenzo V., Canovas D. (2009). Microbial responses to environmental arsenic. Biometals 22 117–130. 10.1007/s10534-008-9195-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C., Asiani K., Arya S., Rensing C., Stekel D. J., Larsson G. J. D., et al. (2017). Metal resistance and its association with antibiotic resistance. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 70 261–313. 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda J., Sarkar P. (2012). Isolation and identification of chromium-resistant bacteria: test application for prevention of chromium toxicity in plant. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 47 237–244. 10.1080/10934529.2012.640895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks J. M., Johs A., Podar M., Bridou R., Hurt R. A., Smith S. D., et al. (2013). The genetic basis for bacterial mercury methylation. Science 339 1332–1335. 10.1126/science.1230667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Valdespino A., Celestino-Mancera M., Lorena Villegas-Rodríguez V., Curiel-Quesada E. (2013). Characterization of mercury-resistant clinical Aeromonas species. Braz. J. Microbiol. 44 1279–1283. 10.1590/s1517-83822013000400036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron K., Caille O., Rossier C., Delden C. V., Dumas J.-L., Köhler T. (2004). CzcR-CzcS, a two-component system involved in heavy metal and carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 279 8761–8768. 10.1074/jbc.m312080200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S., Singh N., Bhagwat Prasad R., Thatoi H. N. (2016). Bacterial chromate reduction: a review of important genomic, proteomic, and bioinformatic analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 1659–1703. 10.1080/10643389.2016.1258912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radke B., Jewell L., Piketh S., Namieśnik J. (2014). Arsenic-based warfare agents: production, use, and destruction. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 1525–1576. 10.1080/10643389.2013.782170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risher J., Rob D. (1999). Toxic Substances Portal- Mercury. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp46.pdf (accessed March 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Rizzotto M. (2012). Metal Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents. London: Intechopen. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch D. A., Lee B. T., Morby A. P. (1995). Understanding cellular responses to toxic agents: a model for mechanism-choice in bacterial metal resistance. J. Ind. Microbiol. 14 132–141. 10.1007/bf01569895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlatt J. (2014). Tungsten: The Perfect Metal for Bullets and Missiles. London: BBC. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Z., Feng Y. (2016). BacWGSTdb, a database for genotyping and source tracking bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D682–D687. 10.1093/nar/gkv1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savabieasfahani M., Ali S. S., Bacho R., Savabi O., Alsabbak M. (2016). Prenatal metal exposure in the Middle East: imprint of war in deciduous teeth of children. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188:505. 10.1007/s10661-016-5491-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P., Deye G., Srinivasan A., Murray C., Moran K., Hulten E., et al. (2007). An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex infection in the us military health care system associated with military operations in Iraq. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 1577–1584. 10.1086/518170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler C., Berendonk T. (2012). Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 3:399. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma J., Shamim K., Dubey S. K., Meena R. M. (2017). Metallothionein assisted periplasmic lead sequestration as lead sulfite by Providencia vermicola strain SJ2A. Sci. Total Environ. 579 359–365. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M. N., Shim J., You Y., Myung H., Bang K. S., Cho M., et al. (2012). Characterization of lead resistant endophytic Bacillus sp. MN3-4 and its potential for promoting lead accumulation in metal hyperaccumulator Alnus firma. J. Hazard. Mater. 199–200 314–320. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira E., Freitas A. R., Antunes P., Barros M., Campos J., Coque T. M., et al. (2014). Co-transfer of resistance to high concentrations of copper and first-line antibiotics among Enterococcus from different origins (humans, animals, the environment and foods) and clonal lineages. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69 899–906. 10.1093/jac/dkt479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver S., Phung le T. (2005). A bacterial view of the periodic table: genes and proteins for toxic inorganic ions. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32 587–605. 10.1007/s10295-005-0019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Gautam N., Mishra A., Gupta R. (2011). Heavy metals and living systems: an overview. Indian J. Pharmacol. 43 246–253. 10.4103/0253-7613.81505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K., Roberts S. A., McDevitt S. F., Weichsel A., Wildner G. F., Grass G. B., et al. (2011). Crystal structures of multicopper oxidase CueO bound to copper(I) and silver(I): functional role of a methionine-rich sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 286 37849–37857. 10.1074/jbc.M111.293589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeaton C. M., Fryer B. J., Weisener C. G. (2009). Intracellular precipitation of Pb by Shewanella putrefaciens CN32 during the reductive dissolution of Pb-jarosite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43 8086–8091. 10.1021/es901629c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S. (2018). Studies on the biosorption of Pb(II) ions using Pseudomonas putida. Sep. Sci. Technol. 53 2550–2562. 10.1080/01496395.2018.1464025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szivák I., Behra R., Sigg L. (2009). Metal-induced reactive oxygen species production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (chlorophyceae). J. Phycol. 45 427–435. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou P. B., Yedjou C. G., Patlolla A. K., Sutton D. J. (2012). Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp. Suppl. 101 133–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong M. J. (1972). Septic complications of war wounds. JAMA 219 1044–1047. 10.1001/jama.219.8.1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevors J. T., Oddie K. M. (1986). R-plasmid transfer in soil and water. Can. J. Microbiol. 32 610–613. 10.1139/m86-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. L., Neu H. M., Gilbreath J. J., Michel S. L., Zurawski D. V., Merrell D. S. (2016). Copper resistance of the emerging pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 6174–6188. 10.1128/aem.01813-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A., Fox E. M., Fegan N., Kurtboke D. I. (2019). Comparative genomics and phenotypic investigations into antibiotic, heavy metal, and disinfectant susceptibilities of Salmonella enterica strains isolated in Australia. Front. Microbiol. 10:1620. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wireman J., Liebert C. A., Smith T., Summers A. O. (1997). Association of mercury resistance with antibiotic resistance in the gram-negative fecal bacteria of primates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 4494–4503. 10.1128/aem.63.11.4494-4503.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P. T. S., Chau Y. K., Luxon P. L. (1975). Methylation of lead in the environment. Nature 253 263–264. 10.1038/253263a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., Li J., Zhou Z., Wang D., Huang J., Wang G. (2018). High-quality-draft genome sequence of the multiple heavy metal resistant bacterium Pseudaminobacter manganicus JH-7(T). Stand. Genomic Sci. 13:29. 10.1186/s40793-018-0330-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Rawat S., Stemmler T. L., Rosen B. P. (2010). Arsenic binding and transfer by the ArsD As(III) metallochaperone. Biochemistry 49 3658–3666. 10.1021/bi100026a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Gunn L., Wall P., Fanning S. (2017). Antimicrobial resistance and its association with tolerance to heavy metals in agriculture production. Food Microbiol. 64 23–32. 10.1016/j.fm.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]