Abstract

Based on molecular phylogenetic and morphological evidence, the new genus Linosporopsis (Xylariales) is established for several species previously classified within Linospora (Diaporthales). Fresh collections of Linospora ischnotheca from dead overwintered leaves of Fagus sylvatica and of L. ochracea from dead overwintered leaves of Malus domestica, Pyrus communis, and Sorbus intermedia were isolated in pure culture, and molecular phylogenetic analyses of a multi-locus matrix of partial nuITS-LSU rDNA, RPB2 and TUB2 sequences as well as morphological investigations revealed that both species are unrelated to the diaporthalean genus Linospora, but belong to Xylariaceae sensu stricto. The new combinations Linosporopsis ischnotheca and L. ochracea are proposed, the species are described and illustrated, and their basionyms lecto- and epitypified. Linospora faginea is synonymized with L. ischnotheca. Based on similar morphology and ecology, Linospora carpini and Linospora magnagutiana from dead leaves of Carpinus betulus and Sorbus torminalis, respectively, are also combined in Linosporopsis. The four accepted species of Linosporopsis are illustrated, a key to species is provided and their ecology is discussed.

Keywords: Ascomycota, Diaporthales, Leaf endophytes, Linospora, Molecular phylogeny, Systematics, Xylariales, 4 new combinations, 1 new name

Introduction

The genus Linospora was established by Fuckel (1870) for five species growing on dead leaves of Salicaeae. He did not designate a generic type, but Clements and Shear (1931) selected Linospora capreae, which grows on Salix caprea, as lectotype. The genus is characterized by long, filiform ascospores arranged in a single fascicle within the ascus, and by reduced black stromata embedded in dead leaf tissue containing usually one (in L. ceuthocarpa up to six) perithecia with laterally inserted ostioles. The black stromata appear in spring and are noticeable as black dots of ca. 0.5–1 mm diam on both sides of the dead, usually bleached leaves. The characteristics of ascomata and asci are clearly diaporthalean, and its classification within Gnomoniaceae (Monod 1983; Barr 1990) has also been corroborated by molecular phylogenetic analyses (Mejía et al. 2008). So far, the about eight accepted species of Linospora inhabit leaves of Salix or Populus spp. (Salicaceae), but morphological evidence suggests the presence of additional undescribed species on Salicaceae (Monod 1983).

Soon after its description, additional species with long filiform ascospores and black ascomata or stromata embedded in leaf tissues were added to Linospora. However, critical morphological re-investigations by Monod (1983) revealed that many of these are not diaporthalean and therefore unrelated to the generic type. Five of them, L. carpini from leaves of Carpinus betulus; L. faginea, and L. ischnotheca from leaves of Fagus sylvatica; L. magnagutiana from leaves of Sorbus torminalis and L. ochracea from leaves of various other rosaceous hosts from subtribe Pyrinae, were considered to be synonymous and to belong to the genus Ophiodothella (Phyllachoraceae), but Monod (1983) neither provided a detailed reasoning nor proposed a formal combination. Thus, in the lack of additional detailed studies, the nomenclature, systematic affiliation and taxonomic status of these five species remained unresolved.

Recent fresh collections of L. ischnotheca and L. ochracea provided the opportunity to study their morphology in detail and to isolate them in pure culture for sequencing. Molecular phylogenetic analyses of a multi-locus matrix of nuITS-LSU rDNA, RPB2 and TUB2 sequences and morphological studies including type material enabled us to resolve their systematic affiliation, to evaluate their species status and taxonomy, and to propose a revised classification, the results of which we report here.

Materials and methods

Sample sources

All isolates included in this study originated from ascospores of freshly collected specimens. Details of the strains including NCBI GenBank accession numbers of gene sequences used to compute the phylogenetic trees are listed in Table 1. Strain acronyms other than those of official culture collections are used here primarily as strain identifiers throughout the work. Representative isolates have been deposited at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Centre (CBS-KNAW), Utrecht, The Netherlands. Details of the specimens used for morphological investigations are listed in the Taxonomy section under the respective descriptions. Herbarium acronyms are according to Thiers (2019), and citation of exsiccata follows Triebel and Scholz (2019). Specimens have been deposited in the Fungaria of the Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Vienna (WU) and of the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (ZT).

Table 1.

Isolates and accession numbers used in the phylogenetic analyses. Isolates/sequences in bold were isolated/sequenced in the present study

| Species | Specimen or strain numbera | Origin | Statusb | GenBank accession numbersc | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | RPB2 | TUB2 | |||||

| Amphirosellinia fushanensis | HAST 91111209 | Taiwan | HT | GU339496 | N/A | GQ848339 | GQ495950 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Amphirosellinia nigrospora | HAST 91092308 | Taiwan | HT | GU322457 | N/A | GQ848340 | GQ495951 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Annulohypoxylon annulatum | CBS 140775 | Texas | ET | KY610418 | KY610418 | KY624263 | KX376353 | Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Annulohypoxylon atroroseum | ATCC 76081 | Thailand | AJ390397 | KY610422 | KY624233 | DQ840083 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Annulohypoxylon michelianum | CBS 119993 | Spain | KX376320 | KY610423 | KY624234 | KX271239 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Annulohypoxylon moriforme | CBS 123579 | Martinique | KX376321 | KY610425 | KY624289 | KX271261 | Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Annulohypoxylon nitens | MFLUCC 12–0823 | Thailand | KJ934991 | KJ934992 | KJ934994 | KJ934993 | Daranagama et al. (2015) | |

| Annulohypoxylon stygium | MUCL 54601 | French Guiana | KY610409 | KY610475 | KY624292 | KX271263 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Annulohypoxylon truncatum | CBS 140778 | Texas | ET | KY610419 | KY610419 | KY624277 | KX376352 | Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Anthostomelloides krabiensis | MFLUCC 15–0678 | Thailand | HT | KX305927 | KX305928 | KX305929 | N/A | Tibpromma et al. (2017) |

| Astrocystis concavispora | MFLUCC 14–0174 | Italy | KP297404 | KP340545 | KP340532 | KP406615 | Daranagama et al. (2015) | |

| Barrmaelia macrospora | CBS 142768 | Austria | ET | KC774566 | KC774566 | MF488995 | MF489014 | Jaklitsch et al. 2014, Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Barrmaelia moravica | CBS 142769 | Austria | ET | MF488987 | MF488987 | MF488996 | MF489015 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Barrmaelia oxyacanthae | CBS 142770 | Austria | MF488988 | MF488988 | MF488997 | MF489016 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) | |

| Barrmaelia rappazii | CBS 142771 | Norway | HT | MF488989 | MF488989 | MF488998 | MF489017 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Barrmaelia rhamnicola | CBS 142772 | France | ET | MF488990 | MF488990 | MF488999 | MF489018 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Biscogniauxia arima | WSP 122 | Mexico | IT | EF026150 | N/A | GQ304736 | AY951672 | Hsieh et al. (2005, 2010) |

| Biscogniauxia atropunctata | Y.M.J. 128 | USA | JX507799 | N/A | JX507778 | AY951673 | Hsieh et al. (2005), Mirabolfathy et al. (2013) | |

| Biscogniauxia marginata | MFLUCC 12–0740 | France | KJ958407 | KJ958408 | KJ958409 | KJ958406 | Daranagama et al. (2015) | |

| Biscogniauxia nummularia | MUCL 51395 | France | ET | KY610382 | KY610427 | KY624236 | KX271241 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Biscogniauxia repanda | ATCC 62606 | USA | KY610383 | KY610428 | KY624237 | KX271242 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Camillea obularia | ATCC 28093 | Puerto Rico | KY610384 | KY610429 | KY624238 | KX271243 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Camillea tinctor | Y.M.J. 363 | Martinique | JX507806 | N/A | JX507790 | JX507795 | Mirabolfathy et al. (2013) | |

| Clypeosphaeria mamillana | CBS 140735 | France | ET | KT949897 | KT949897 | MF489001 | N/A | Jaklitsch et al. 2016, Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Collodiscula bambusae | GZU H0102 | China | KP054279 | KP054280 | KP276675 | KP276674 | Li et al. (2015) | |

| Collodiscula fangjingshanensis | GZU H0109 | China | HT | KR002590 | KR002591 | KR002592 | KR002589 | Li et al. (2015) |

| Collodiscula japonica | CBS 124266 | China | JF440974 | JF440974 | KY624273 | KY624316 | Jaklitsch and Voglmayr (2012), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Creosphaeria sassafras | STMA 14087 | Argentina | KY610411 | KY610468 | KY624265 | KX271258 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia andina | CBS 114736 | Ecuador | HT | AM749918 | KY610430 | KY624239 | KC977259 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia bambusicola | CBS 122872 | Thailand | HT | KY610385 | KY610431 | KY624241 | AY951688 | Hsieh et al. (2005), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia caldariorum | MUCL 49211 | France | AM749934 | KY610433 | KY624242 | KC977282 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia concentrica | CBS 113277 | Germany | AY616683 | KY610434 | KY624243 | KC977274 | Triebel et al. (2005), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia dennisii | CBS 114741 | Australia | HT | JX658477 | KY610435 | KY624244 | KC977262 | Stadler et al. (2014), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia eschscholtzii | MUCL 45435 | Benin | JX658484 | KY610437 | KY624246 | KC977266 | Stadler et al. (2014), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia loculatoides | CBS 113279 | UK | ET | AF176982 | KY610438 | KY624247 | KX271246 | Johannesson et al. (2000), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia macaronesica | CBS 113040 | Spain | PT | KY610398 | KY610477 | KY624294 | KX271266 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia petriniae | MUCL 49214 | Austria | ET | AM749937 | KY610439 | KY624248 | KC977261 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia placentiformis | MUCL 47603 | Mexico | AM749921 | KY610440 | KY624249 | KC977278 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia pyrenaica | MUCL 53969 | France | KY610413 | KY610413 | KY624274 | KY624312 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Daldinia steglichii | MUCL 43512 | Papua New Guinea | PT | KY610399 | KY610479 | KY624250 | KX271269 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia theissenii | CBS 113044 | Argentina | PT | KY610388 | KY610441 | KY624251 | KX271247 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Daldinia vernicosa | CBS 119316 | Germany | ET | KY610395 | KY610442 | KY624252 | KC977260 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Diatrype disciformis | CBS 197.49 | Netherlands | N/A | DQ470964 | DQ470915 | N/A | Zhang et al. (2006) | |

| Entoleuca mammata | J.D.R. 100 | France | GU300072 | N/A | GQ844782 | GQ470230 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Entonaema liquescens | ATCC 46302 | USA | KY610389 | KY610443 | KY624253 | KX271248 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Entosordaria perfidiosa | CBS 142773 | Austria | ET | MF488993 | MF488993 | MF489003 | MF489021 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Entosordaria quercina | CBS 142774 | Greece | HT | MF488994 | MF488994 | MF489004 | MF489022 | Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Euepixylon sphaeriostomum | J.D.R. 261 | USA | GU292821 | N/A | GQ844774 | GQ470224 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Eutypa lata | UCR-EL1 | USA | JGI | JGI | JGI | JGI | ||

| Gnomonia gnomon | CBS 199.53 | Italy | AY818956 | AF408361 | EU219295 | EU219148 | Castlebury et al. (2002), Sogonov et al. (2005, 2008) | |

| Graphostroma platystomum | CBS 270.87 | France | JX658535 | DQ836906 | KY624296 | HG934108 | ||

| Hypocreodendron sanguineum | J.D.R. 169 | Mexico | GU322433 | N/A | GQ844819 | GQ487710 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Hypomontagnella monticulosa | MUCL 54604 | French Guiana | ET | KY610404 | KY610487 | KY624305 | KX271273 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypomontagnella submonticulosa | CBS 115280 | France | KC968923 | KY610457 | KY624226 | KC977267 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon carneum | MUCL 54177 | France | KY610400 | KY610480 | KY624297 | KX271270 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon cercidicola | CBS 119009 | France | KC968908 | KY610444 | KY624254 | KC977263 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon crocopeplum | CBS 119004 | France | KC968907 | KY610445 | KY624255 | KC977268 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon fendleri | MUCL 54792 | French Guiana | KF234421 | KY610481 | KY624298 | KF300547 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon fragiforme | MUCL 51264 | Germany | ET | KC477229 | KM186295 | KM186296 | KX271282 | Stadler et al. (2013), Daranagama et al. (2015), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon fuscum | CBS 113049 | France | ET | KY610401 | KY610482 | KY624299 | KX271271 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon griseobrunneum | CBS 331.73 | India | HT | KY610402 | KY610483 | KY624300 | KC977303 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon haematostroma | MUCL 53301 | Martinique | ET | KC968911 | KY610484 | KY624301 | KC977291 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon howeanum | MUCL 47599 | Germany | AM749928 | KY610448 | KY624258 | KC977277 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon hypomiltum | MUCL 51845 | Guadeloupe | KY610403 | KY610449 | KY624302 | KX271249 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon investiens | CBS 118183 | Malaysia | KC968925 | KY610450 | KY624259 | KC977270 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon lateripigmentum | MUCL 53304 | Martinique | HT | KC968933 | KY610486 | KY624304 | KC977290 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon lenormandii | CBS 119003 | Ecuador | KC968943 | KY610452 | KY624261 | KC977273 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon musceum | MUCL 53765 | Guadeloupe | KC968926 | KY610488 | KY624306 | KC977280 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon ochraceum | MUCL 54625 | Martinique | ET | KC968937 | N/A | KY624271 | KC977300 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon papillatum | ATCC 58729 | USA | HT | KC968919 | KY610454 | KY624223 | KC977258 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon perforatum | CBS 115281 | France | KY610391 | KY610455 | KY624224 | KX271250 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon petriniae | CBS 114746 | France | HT | KY610405 | KY610491 | KY624279 | KX271274 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon pilgerianum | STMA 13455 | Martinique | KY610412 | KY610412 | KY624308 | KY624315 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon porphyreum | CBS 119022 | France | KC968921 | KY610456 | KY624225 | KC977264 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon pulicicidum | CBS 122622 | Martinique | HT | JX183075 | KY610492 | KY624280 | JX183072 | Bills et al. (2012), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon rickii | MUCL 53309 | Martinique | ET | KC968932 | KY610416 | KY624281 | KC977288 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon rubiginosum | MUCL 52887 | Germany | ET | KC477232 | KY610469 | KY624266 | KY624311 | Stadler et al. (2013), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon samuelsii | MUCL 51843 | Guadeloupe | ET | KC968916 | KY610466 | KY624269 | KC977286 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon ticinense | CBS 115271 | France | JQ009317 | KY610471 | KY624272 | AY951757 | Hsieh et al. (2005), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Hypoxylon trugodes | MUCL 54794 | Sri Lanka | ET | KF234422 | KY610493 | KY624282 | KF300548 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Hypoxylon vogesiacum | CBS 115273 | France | KC968920 | KY610417 | KY624283 | KX271275 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Jackrogersella cohaerens | CBS 119126 | Germany | KY610396 | KY610497 | KY624270 | KY624314 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Jackrogersella minutella | CBS 119015 | Portugal | KY610381 | KY610424 | KY624235 | KX271240 | Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Jackrogersella multiformis | CBS 119016 | Germany | ET | KC477234 | KY610473 | KY624290 | KX271262 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Juglanconis juglandina | CBS 133343 | Austria | KY427149 | KY427149 | KY427199 | KY427234 | Voglmayr et al., (2017) | |

| Kretzschmaria deusta | CBS 163.93 | Germany | KC477237 | KY610458 | KY624227 | KX271251 | Stadler et al. (2013), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Linospora capreae | CBS 372.69 | Netherlands | EU199194 | EU255199 | EU199152 | EU219232 | Mejía et al. (2008) | |

| Linosporopsis ischnotheca | LIF1 = CBS 145761 | Switzerland | ET | MN818952 | MN818952 | MN820708 | MN820715 | This study |

| Linosporopsis ischnotheca | LIF2 | Switzerland | MN818953 | MN818953 | MN820709 | MN820716 | This study | |

| Linosporopsis ischnotheca | LIF3 | Spain | MN818954 | MN818954 | MN820710 | MN820717 | This study | |

| Linosporopsis ochracea | LIO = CBS 145760 | Switzerland | MN818955 | MN818955 | MN820711 | MN820718 | This study | |

| Linosporopsis ochracea | LIO1 | Austria | MN818956 | MN818956 | MN820712 | MN820719 | This study | |

| Linosporopsis ochracea | LIO2 | Germany | MN818957 | MN818957 | MN820713 | MN820720 | This study | |

| Linosporopsis ochracea | LIO3 = CBS 145999 | Germany | ET | MN818958 | MN818958 | MN820714 | MN820721 | This study |

| Lopadostoma dryophilum | CBS 133213 | Austria | ET | KC774570 | KC774570 | KC774526 | MF489023 | Jaklitsch et al. 2014, Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Lopadostoma turgidum | CBS 133207 | Austria | ET | KC774618 | KC774618 | KC774563 | MF489024 | Jaklitsch et al. 2014, Voglmayr et al. (2018) |

| Melanconis stilbostoma | D143 | Poland | KY427156 | KY427156 | KY427206 | KY427241 | Voglmayr et al., (2017) | |

| Nemania abortiva | BISH 467 | USA | HT | GU292816 | N/A | GQ844768 | GQ470219 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Nemania beaumontii | HAST 405 | Martinique | GU292819 | N/A | GQ844772 | GQ470222 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Nemania bipapillata | HAST 90080610 | Taiwan | GU292818 | N/A | GQ844771 | GQ470221 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Nemania maritima | HAST 89120401 | Taiwan | ET | N/A | N/A | GQ844775 | GQ470225 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Nemania maritima | STMA 04019 = J.F. 03075 | France | KY610414 | KY610414 | N/A | N/A | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Nemania primolutea | HAST 91102001 | Taiwan | HT | EF026121 | N/A | GQ844767 | EF025607 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Obolarina dryophila | MUCL 49882 | France | GQ428316 | GQ428316 | KY624284 | GQ428322 | Pažoutová et al. (2010), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Podosordaria mexicana | WSP 176 | Mexico | GU324762 | N/A | GQ853039 | GQ844840 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Podosordaria muli | WSP 167 | Mexico | HT | GU324761 | N/A | GQ853038 | GQ844839 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Poronia pileiformis | WSP 88113001 | Taiwan | ET | GU324760 | N/A | GQ853037 | GQ502720 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Poronia punctata | CBS 656.78 | Australia | HT | KT281904 | KY610496 | KY624278 | KX271281 | Senanayake et al. (2015), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Pyrenopolyporus hunteri | MUCL 52673 | Ivory Coast | ET | KY610421 | KY610472 | KY624309 | KU159530 | Kuhnert et al. (2017), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Pyrenopolyporus laminosus | MUCL 53305 | Martinique | HT | KC968934 | KY610485 | KY624303 | KC977292 | Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Pyrenopolyporus nicaraguensis | CBS 117739 | Burkina Faso | AM749922 | KY610489 | KY624307 | KC977272 | Bitzer et al. (2008), Kuhnert et al. (2014), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Rhopalostroma angolense | CBS 126414 | Ivory Coast | KY610420 | KY610459 | KY624228 | KX271277 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Rosellinia aquila | MUCL 51703 | France | KY610392 | KY610460 | KY624285 | KX271253 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Rosellinia buxi | J.D.R. 99 | France | GU300070 | N/A | GQ844780 | GQ470228 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Rosellinia corticium | MUCL 51693 | France | KY610393 | KY610461 | KY624229 | KX271254 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Rosellinia necatrix | CBS 349.36 | Argentina | AY909001 | KF719204 | KY624275 | KY624310 | Pelaez et al. (2008), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Rostrohypoxylon terebratum | CBS 119137 | Thailand | HT | DQ631943 | DQ840069 | DQ631954 | DQ840097 | Tang et al. (2007), Fournier et al. (2010) |

| Ruwenzoria pseudoannulata | MUCL 51394 | D. R. Congo | HT | KY610406 | KY610494 | KY624286 | KX271278 | Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Sarcoxylon compunctum | CBS 359.61 | South Africa | KT281903 | KY610462 | KY624230 | KX271255 | Senanayake et al. (2015), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Stilbohypoxylon elaeicola | Y.M.J. 173 | French Guiana | EF026148 | N/A | GQ844826 | EF025616 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Stilbohypoxylon quisquiliarum | Y.M.J. 172 | French Guiana | EF026119 | N/A | GQ853020 | EF025605 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Thamnomyces dendroidea | CBS 123578 | French Guiana | HT | FN428831 | KY610467 | KY624232 | KY624313 | Stadler et al. (2010), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Xylaria acuminatilongissima | HAST 95060506 | Taiwan | HT | EU178738 | N/A | GQ853028 | GQ502711 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Xylaria adscendens | J.D.R. 865 | Thailand | GU322432 | N/A | GQ844818 | GQ487709 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Xylaria arbuscula | CBS 126415 | Germany | KY610394 | KY610463 | KY624287 | KX271257 | Fournier et al. (2011), Wendt et al. (2018) | |

| Xylaria bambusicola | WSP 205 | Taiwan | HT | EF026123 | N/A | GQ844802 | AY951762 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Xylaria brunneovinosa | HAST 720 | Martinique | HT | EU179862 | N/A | GQ853023 | GQ502706 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Xylaria curta | HAST 494 | Martinique | GU322444 | N/A | GQ844831 | GQ495937 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Xylaria discolor | HAST 131023 | USA | ET | JQ087405 | N/A | JQ087411 | JQ087414 | Hsieh et al. (2010) |

| Xylaria hypoxylon | CBS 122620 | Sweden | ET | KY610407 | KY610495 | KY624231 | KX271279 | Sir et al. (2016), Wendt et al. (2018) |

| Xylaria multiplex | HAST 580 | Martinique | GU300098 | N/A | GQ844814 | GQ487705 | Hsieh et al. (2010) | |

| Xylaria polymorpha | MUCL 49884 | France | KY610408 | KY610464 | KY624288 | KX271280 | Wendt et al. (2018) | |

aATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, USA; BISH, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, USA; CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; GZU H, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China; HAST, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan; J.D.R., Jack D. Rogers, Washington State University, Pullman, USA; J.F., Jacques Fournier, Rimont, France; MFLUCC, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, Thailand; MUCL, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; STMA, Marc Stadler, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Infektionsforschung, Braunschweig, Germany; UCR, University of California, Riverside, USA; Y.M.J., Yu-Ming Ju, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan; WSP, Washington State University, Pullman, USA

bET, epitype; HT, holotype; IT, isotype; PT, paratype

cN/A, not available; JGI, sequences retrieved from JGI-DOE (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/)

Morphology

Microscopic observations were made in tap water except where noted. Methods of microscopy included stereomicroscopy using a Nikon SMZ 1500 equipped with a Nikon DS-U2 digital camera, and Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) using a Zeiss Axio Imager.A1 compound microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam 506 color digital camera. Images and data were gathered using the NIS-Elements D v. 3.22.15 or Zeiss ZEN Blue Edition software packages. Measurements are reported as maxima and minima in parentheses and the range representing the mean plus and minus the standard deviation of a number of measurements given in parentheses.

Culture preparation, DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing

Isolates were prepared from ascospores as described in Jaklitsch (2009) and grown on MEA or on 2% corn meal agar plus 2% w/v dextrose (CMD). Growth of liquid culture and extraction of genomic DNA was performed as reported previously (Voglmayr and Jaklitsch 2011; Jaklitsch et al. 2012) using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAgen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

The following loci were amplified and sequenced: the complete internal transcribed spacer region (ITS1–5.8S–ITS2) and a ca. 0.9-kb fragment of the large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA (nuLSU rDNA), amplified and sequenced as a single fragment with primers V9G (de Hoog and Gerrits van den Ende 1998) and LR5 (Vilgalys and Hester 1990); a ca. 1.2-kb fragment of the RNA polymerase II subunit 2 (RPB2) gene with primers dRPB2-5f and dRPB2-7r (Voglmayr et al. 2016a); and a ca. 1.6-kb fragment of the beta-tubulin (TUB2) gene with primers T1D and T22D (Voglmayr et al. 2019). PCR products were purified using an enzymatic PCR cleanup (Werle et al. 1994) as described in Voglmayr and Jaklitsch (2008). DNA was cycle-sequenced using the ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems,Warrington, UK) and the PCR primers; in addition, primers ITS4 (White et al. 1990), LR2R-A (Voglmayr et al. 2012) and LR3 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) were used as internal sequencing primers for the ITS-LSU rDNA region, and BtHV2r (Voglmayr et al. 2016b, 2017) and BtHVf (Voglmayr & Mehrabi 2018) for TUB2. Sequencing was performed on an automated DNA sequencer (ABI 3730xl Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems).

Data analysis

The newly generated sequences were aligned to the sequence alignments of Voglmayr et al. (2018), and GenBank sequences of four taxa of Diaporthales (Gnomonia gnomon, Juglanconis juglandina, Linospora capreae, and Melanconis stilbostoma) were added as the outgroup. Some taxa included in the matrix of Voglmayr et al. (2018) which contained poor or incomplete sequence data and which were not relevant for this study were removed from the matrices. The GenBank accession numbers of sequences used in these analyses are given in Table 1.

Sequence alignments for phylogenetic analyses were produced with the server version of MAFFT (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/), checked and refined using BioEdit v. 7.2.6 (Hall 1999). The ITS-LSU rDNA, RPB2 and TUB2 matrices were combined for subsequent phylogenetic analyses. After exclusion of ambiguously aligned regions and long gaps, the final combined data matrix contained 4718 characters (622 nucleotides of ITS, 1355 nucleotides of LSU, 1169 nucleotides of RPB2 and 1572 nucleotides of TUB2). Familial classification of Xylariaceae and pylogenetically related families follows Voglmayr et al. (2018) and Wendt et al. (2018).

Maximum parsimony (MP) analyses were performed with PAUP v. 4.0a165 (Swofford 2002). All molecular characters were unordered and given equal weight; analyses were performed with gaps treated as missing data; the COLLAPSE command was set to MINBRLEN. MP analysis of the combined multilocus matrix was done using 1000 replicates of heuristic search with random addition of sequences and subsequent TBR branch swapping (MULTREES option in effect, steepest descent option not in effect). Bootstrap analyses with 1000 replicates were performed in the same way, but using 5 rounds of random sequence addition and subsequent branch swapping during each bootstrap replicate.

Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed with RAxML (Stamatakis 2006) as implemented in raxmlGUI 1.3 (Silvestro and Michalak 2012), using the ML + rapid bootstrap setting and the GTRGAMMA substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The matrix was partitioned for the different gene regions. For evaluation and discussion of bootstrap support, values below 70% were considered low, between 70 and 90% medium/moderate and above 90% high.

Results

Molecular phylogeny

The combined multilocus matrix used for phylogenetic analyses comprised 4718 characters, of which 2129 were parsimony informative (360 from ITS, 273 from LSU, 658 from RPB2 and 838 from TUB2). Figure 1 shows a simplified phylogram of the best ML tree (lnL = − 131,936.737) obtained by RAxML. Maximum parsimony analyses revealed four MP trees 31,692 steps long, which were identical except for slightly different positions of Daldinia andina and Stilbohypoxylon quisquiliarum (not shown). The backbone of the MP trees was similar to the ML tree, except for a few minor topological differences of unsupported nodes within the Barrmaeliaceae, Graphostromataceae, Hypoxylaceae and Xylariaceae (not shown). Linospora ischnotheca and L. ochracea were revealed as closely related but distinct species with maximum support (Fig. 1). They were placed remotely from Linospora capreae (Diaporthales) in a basal position within Xylariaceae sensu stricto. A sister-group relationship with the highly (100%, ML) to moderately (89%, MP) supported Clypeosphaeria mamillana-Anthostomelloides krabiensis clade (Fig. 1) received high (98%, ML) or low (53%, MP) bootstrap support. The sequences of Linospora ochracea accessions from Malus domestica, Pyrus communis, and Sorbus intermedia were almost identical, confirming conspecificity of the accessions from these hosts.

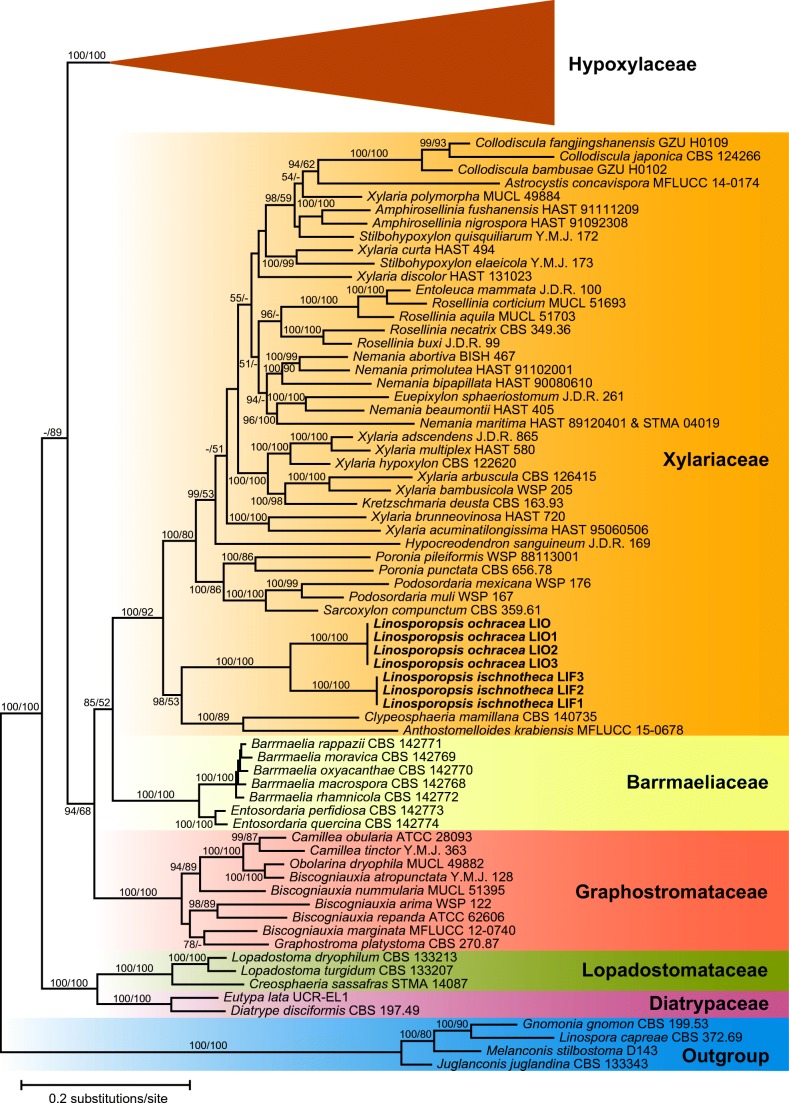

Fig. 1.

Simplified phylogram of the best ML trees (lnL = − 131,936.737) revealed by RAxML from an analysis of the combined ITS–LSU–RPB2–TUB2 matrix of selected Xylariales, showing the position of Linosporopsis (bold). The large Hypoxylaceae clade, which is not treated in detail, is collapsed to provide sufficient space for the other clades of interest. ML and MP bootstrap support above 60% are given at the first and second positions, respectively, above or below the branches

Taxonomy

Linosporopsis Voglmayr & Beenken, gen. nov.

MycoBank: MB 833894.

Etymology: referring to its similarity to Linospora.

Type species: Linosporopsis ischnotheca (Desm.) Voglmayr & Beenken.

Mycelium in dead overwintered leaves, strongly bleaching the host tissue. Pseudostromata immersed in dead leaves, reduced, forming a distinct black clypeus-like structure on both sides of the leaf above and below the single perithecium, composed of dark brown, septate hyphae in dead host epidermis cells and forming a textura epidermoidea-intricata. Ascomata perithecial, scattered, solitary, immersed, (sub)globose, with a central apical papilla. Peridium thin, composed of hyaline, thin-walled, pseudoparenchymatous to prosenchymatous cells forming a textura angularis. Hamathecium of unbranched, thin-walled, hyaline, septate, apically tapering paraphyses. Asci unitunicate, long-cylindrical, with a short stipe, with an indistinct, inamyloid or slightly amyloid apical apparatus, containing 8 ascospores in a single fascicle. Ascospores long-filiform, hyaline, smooth, without visible septa, without sheath or appendages. Asexual morph unknown.

Notes: Within Xylariales, the genus is distinctive by long filiform ascospores without obvious septa and by single, scattered clypeate perithecia, which are embedded in a reduced pseudostroma immersed in dead, strongly bleached leaf tissue. The often large, bleached patches on the leaves are highly distinctive, especially when the leaves are wet. Unlike the large, amyloid, wedge-shaped apical apparatus of most Xylariaceae sensu stricto, that of Linosporopsis is indistinct and usually unnoticeable, and only occasionally slightly amyloid (observed only in a single accession each of L. ochracea and L. magnagutiana; see notes below).

Linosporopsis carpini (J. Schröt.) Voglmayr & Beenken, comb. nov. Fig. 2.

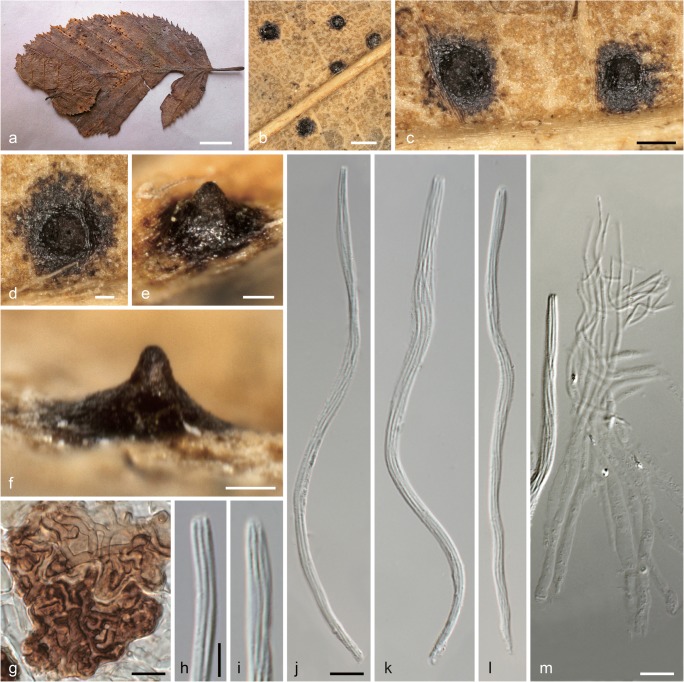

Fig. 2.

Linosporopsis carpini (W 2019-02783, isotype). a Colonies (bleached patches) on dead overwintered leaf of Carpinus betulus. b Close up of a colony with black clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. c–f Uniperitheciate pseudostromata from above (c, d) and in side view (e, f). g Host epidermis cells with dark brown, septate, branched hyphae forming a textura epidermoidea-intricata. h, i Ascus apices. j–l Asci. m Paraphyses. All in 3% KOH. Scale barsa 10 mm; b 400 μm; c 200 μm; d–f 100 μm; g, j–m 10 μm; h, i 5 μm

MycoBank: MB 833896.

Basionym. Linospora carpini J. Schröt., Hedwigia 15: 119. 1876.

Pseudostromata immersed in dead overwintered leaves, reduced, forming a distinct black clypeus (353–)384–463(–507) μm wide (n = 17) on both sides of the leaf, consisting of a textura epidermoidea-intricata composed of thick-walled, dark brown, septate hyphae 1.5–3 μm wide in dead host epidermis cells. Ascomata perithecial, scattered, solitary, immersed in dead leaf tissue, globose to ellipsoid, with a distinct central apical papilla 70–140(–185) μm wide at the base. Peridium not observed. Paraphyses unbranched, septate, thin-walled, collabent, 107–120 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the base and gradually tapering to 1–1.2 μm at the tips. Asci (118–)135–160(–165) × (3.5–)3.7–4.5(–5.0) μm (n = 30), unitunicate, long-cylindrical, with a short stipe, with eight ascospores arranged in a single fascicle, with an indistinct inamyloid apical apparatus. Ascospores (120–)136–158(–162) × 0.7–1.1 μm, l/w = (110–)145–201(–230) (n = 30), filiform, with rounded ends, hyaline, without visible septa, without sheath or appendages.

No cultures available. No asexual morph observed.

Habitat and host range: Dead overwintered leaves of Carpinus betulus.

Distribution: Europe; only known from southwestern Germany and northern Italy.

Isotypes: Germany, Baden-Württemberg, Rastatt, Apr. 1876, J. Schröter, in Rabenhorst, Fungi Eur. Exs. 2132 (M-0304424, M-0304425, W 2019–02783).

Notes: Although no DNA data are yet available, morphology of ascomata, asci and ascospores leave no doubt that the species belongs to Linosporopsis, and considering the high host specificity of the genus, we recognize L. carpini as a distinct species. Apart from the type collection, this species is to our knowledge only known from an additional collection in northern Italy (Veneto, near Conegliano), which was collected in the same year as the type (Saccardo 1877). On the herbarium label of the type collection, it was stated to be common in the forests around Rastatt; however, we are not aware of any recent collections. The type collection has been edited and distributed in numerous copies in Rabenhorst, Fungi Eur. Exs. 2132, but we have investigated in detail only the copy deposited in W, that consists of a single leaf with a few perithecia. To save material, no sections were performed, and only a microscope preparation for documentation and measurements of asci, ascospores, paraphyses and clypeus hyphae was done. Our measurements revealed distinctly longer asci and ascospores than reported in the original description (118–165 μm vs. 70–80 μm in Rabenhorst 1876), which therefore is within the range of the other accepted Linosporopsis species.

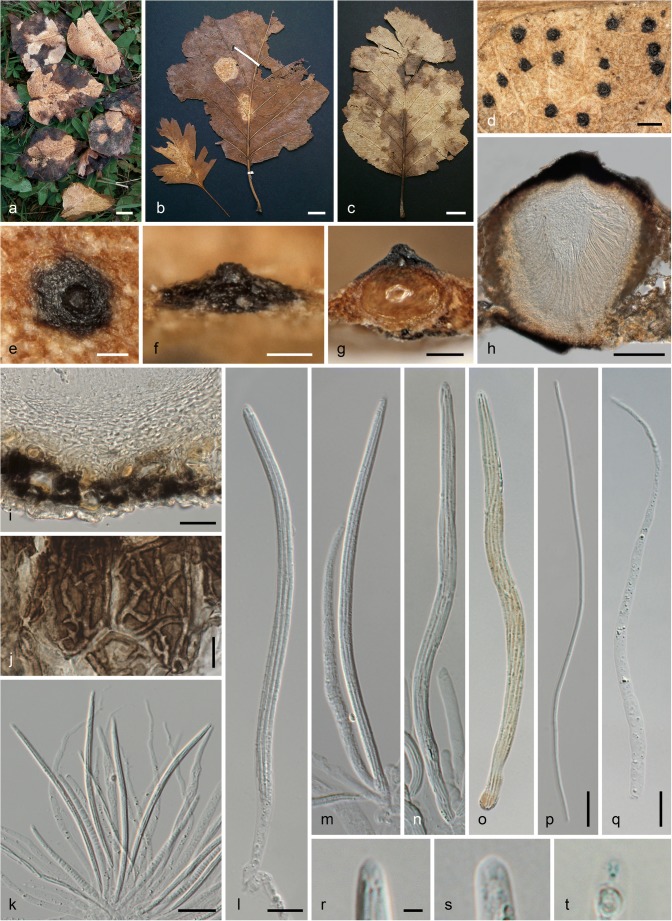

Linosporopsis ischnotheca (Desm.) Voglmayr & Beenken, comb. nov. Fig. 3.

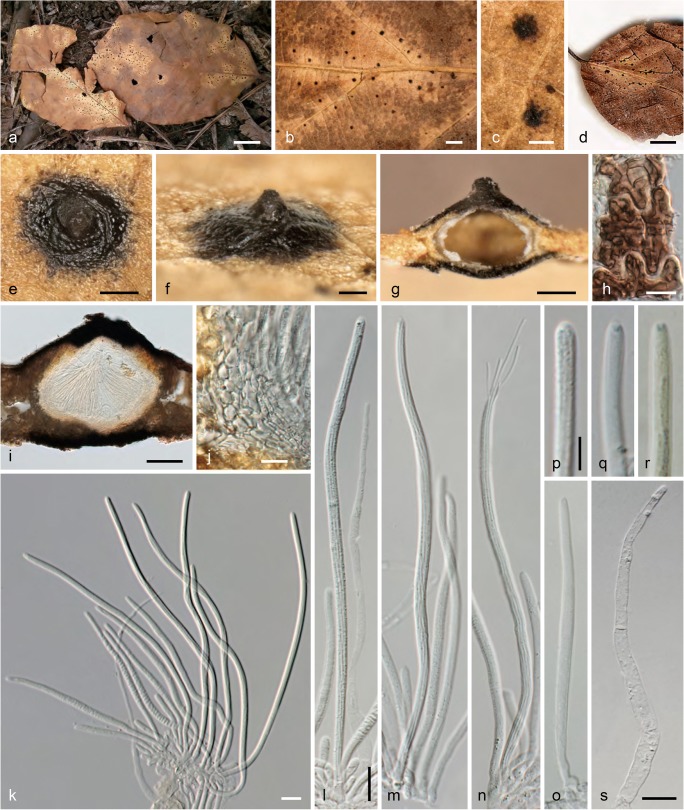

Fig. 3.

Linosporopsis ischnotheca. a Colonies (bleached patches) on dead overwintered leaves of Fagus sylvatica with scattered black, clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. b–d Close up of colonies with black clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. e–g Uniperitheciate pseudostromata from above (e), in side view (f), and in transverse section (g). h Host epidermis cells with dark brown, septate, branched hyphae forming a textura intricata. i Uniperitheciate pseudostroma in transverse section. j Pseudoparenchymatous, hyaline peridium and adjacent host tissue in section. k–o Asci (o immature). p–r Ascus apices. s Paraphysis. All in 3% KOH, except i, j, p, s in water; r in Lugol after KOH pre-treatment (a, e–g, m, n WU 40027; b PC0706583, isotype; c PC0706584, isotype; d PAD, holotype of Linospora magnagutiana subsp. faginea; h K(M) 206638, isotype; i, j, p, s WU 40026; o, q, r K(M) 206636, lectotype). Scale barsa, d 10 mm; b 1 mm; c, e 200 μm; f, g, i 100 μm; h, j–o, s 10 μm, p–r 5 μm

MycoBank: MB 833895.

Basionym. Sphaeria ischnotheca Desm., Annls Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 3 18: 365. 1852.

Synonyms. Linospora faginea Sacc., Michelia 1(no. 4): 405. 1878.

Linospora ischnotheca (Desm.) Sacc., Syll. fung. (Abellini) 2: 356. 1883.

Pseudostromata immersed in dead overwintered leaves, forming a distinct black clypeus (107–)145–247(–315) μm wide (n = 88) on both sides of the leaf, consisting of a textura epidermoidea-intricata composed of thick-walled, dark brown, septate hyphae 1.5–3 μm wide in dead host epidermis cells. Ascomata perithecial, scattered, solitary, immersed in dead leaf tissue, globose to ellipsoid, 230–340 μm diam., with a distinct central apical papilla 100–145(–160) μm wide at the base. Peridium (19–)22–32(–38) μm wide (n = 23), hyaline, pseudoparenchymatous, of hyaline isodiametric to elongate cells, marginal peridium cells (4.5–)7–13.5(–17) × (1.5–)2.5–4.5(–6.5) μm (n = 46), basal peridium cells smaller, (3–)4–9 (–10) × 1.5–2.3(–2.7) μm (n = 16). Paraphyses unbranched, septate, thin-walled, collabent, 74–110 μm long, 4.0–7.5 μm wide at the base and gradually tapering to 2–4.5 μm at the tips (n = 20). Asci (94–)122–153(–175) × (2.8–)3.4–4.3(–5.2) μm (n = 98), unitunicate, long-cylindrical, with a short stipe, with eight ascospores arranged in a single fascicle, with an indistinct inamyloid apical apparatus. Ascospores (84–)118–149(–170) × (0.6–)0.8–1.0(–1.3) μm, l/w = (35–)119–175(–205) (n = 55), filiform, with rounded ends, hyaline, without visible septa, without sheath or appendages.

Colonies on CMD and MEA white; aerial hyphae abundant. No asexual morph observed.

Habitat and host range: Dead overwintered leaves of Fagus sylvatica and F. orientalis; rarely also on Quercus sp.

Distribution: Europe; known from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland.

Typification: France, without place, date and collector, on dead leaves of Fagus sylvatica, in Desmazières, Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 2098 (K(M) 206636, lectotype of Sphaeria ischnotheca here designated, MBT 390204; PC 0706583, isotype); same collection, in Desmazières, Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 1798 (K(M) 206635, PC 0706584, isotypes). Italy, Veneto, Treviso, near Conegliano, spring 1877, C.L. Spegazzini (PAD, holotype of Linospora faginea). Switzerland, Zürich, Thuraue near Flaach, 13 May 2017, L. Beenken (WU 40024, epitype of Sphaeria ischnotheca here designated, MBT 390205; ex epitype culture CBS 145761 = LIF1).

Other specimens examined: France, Calvados (14), Caen, on dead leaves of Fagus sylvatica, without date, M.R. Roberge (M-0304427,? syntype). Landes, Lussagnet, 43.763725° N, − 0.223289° E, 140 m, 16 May 2017, A. Gross (ZT Myc 59965). Germany, Bavaria, Freising, Kranzberger Forst, Weltwald, on dead leaves of Fagus orientalis, 30 Apr. 2019, L. Beenken (WU 40033). Spain, Asturias, Gijón, on dead leaves of Fagus sylvatica, 16 Apr. 2015, Enrique Rubio Domínguez ERD 6431 (WU 40027). Ibid., on dead leaves of Fagus sylvatica and Quercus robur, 16 Apr. 2015, Enrique Rubio Domínguez (WU 40026; culture LIF3). Switzerland, Zürich, Ellikon am Rhein, 20 May 2017, L. Beenken (WU 40025, ZT Myc 59966; culture LIF2). Zürich, Winterthur, Eschenberg, 47°28′58″ N, 8°43′ 24″ E, 530 m, 16 May 2015, L. Beenken (ZT Myc 59967).

Notes: DNA sequence data and morphology place the species within Xylariaceae, as closest relative of L. ochracea. Desmazières (1851) first included specimens from leaves of Fagus sylvatica in his Sphaeria ochracea, but soon thereafter, he described them as a distinct species, S. ischnotheca (Desmazières 1852). In the protologue, he mentioned that the type collection contained only immature asci without spores, which was confirmed for all syntypes investigated in our study. The type collection was edited and distributed in two sets as Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, nos. 1798 and 2098, which is also mentioned in the protologue. Neither locality nor collector are mentioned on the herbarium labels and in the original description of the species, and no original notes of Desmazières are attached to the two copies present in PC. However, the herbarium labels of a specimen in M, probably also a syntype, indicates that it was collected by M.R. Roberge in Caen, i.e. the same place and collector as the type of L. ochracea (see below), which appears plausible considering that material of Fagus was mentioned in the original description of L. ochracea. As the type collection of Sphaeria ischnotheca is immature, we here designate a recent mature collection, for which a culture and DNA sequences are available, as epitype to stabilize the species nomenclature.

Linospora faginea, which was also described from dead leaves of Fagus sylvatica, is obviously a synonym of L. ischnotheca; the protologue in Saccardo (1878) fully matches our material. As Saccardo material of PAD is not sent out on loan, we have not been able to investigate the type in detail, but the illustrations of the specimen and label kindly provided by the Erbario dell’Università di Padua show that it agrees with L. ischnotheca (see Fig. 3d).

The inamyloid apical apparatus of L. ischnotheca is usually indistinct, and only well-seen in IKI (Fig. 3r) or cotton blue. For beautiful additional illustrations of the Spanish specimen ERD 6431, see also http://www.ascofrance.com/search_forum/35346.

Linosporopsis magnagutiana (Sacc.) Voglmayr & Beenken, comb. nov. Fig. 4.

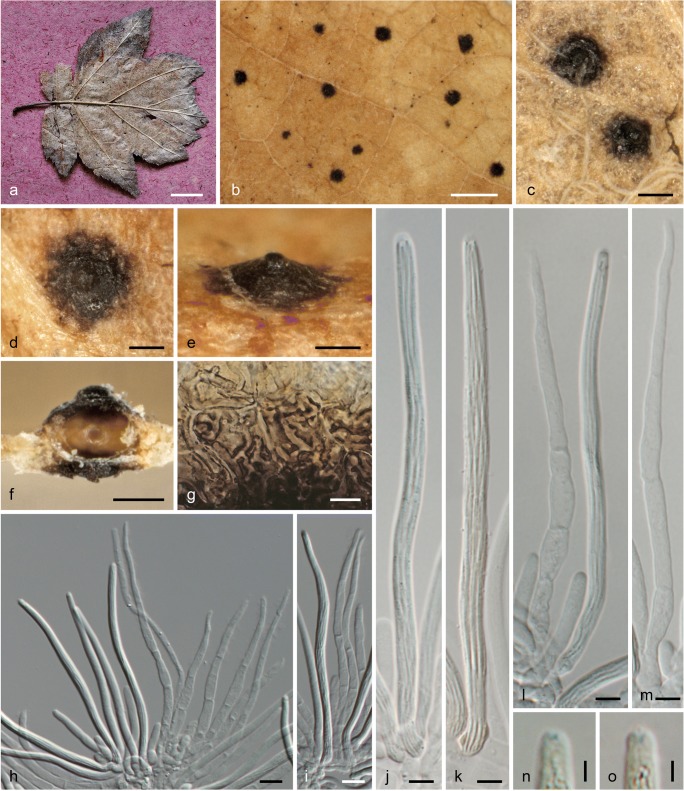

Fig. 4.

Linosporopsis magnagutiana. a Colonies on dead overwintered bleached leaf of Sorbus torminalis. b Close up of a colony with black clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. c–f Uniperitheciate pseudostromata from above (c, d), in side view (e) and in transverse section (f). g Host epidermis cells with dark brown, septate, branched hyphae forming a textura epidermoidea-intricata. h–l Asci with paraphyses (h, j, l). m Paraphysis. n, o Ascus apices with slightly amyloid ring. All in 3% KOH, except k, n, o Lugol after KOH pre-treatment (a–m Thümen, Mycoth. Univ. 1454 (a M s.n., b–m WU s.n.); n, o Saccardo, Mycoth. Ven. 1352 (WU s.n.)). Scale barsa 10 mm; b 1 mm; c–f 100 μm; g–i 10 μm; j–m 5 μm; n, o 2 μm

MycoBank: MB 833897.

Basionym. Linospora magnagutiana Sacc., Michelia 1(no. 1): 45. 1877.

Pseudostromata immersed in dead overwintered leaves, reduced, forming a distinct black clypeus (109–)126–203(–294) μm wide (n = 42) on both sides of the leaf, consisting of a textura epidermoidea-intricata composed of thick-walled, dark brown, septate hyphae 2–4 μm wide mostly in dead host epidermis cells. Ascomata perithecial, scattered, solitary, immersed in dead leaf tissue, globose to depressed globose, ca. 150–170 μm diam., with a distinct central apical papilla 30–65 μm wide at the base. Paraphyses unbranched, septate, thin-walled, collabent, (73–)81–100(–111) μm long, (3.5–)4–5.5(–6) μm wide at the base and gradually tapering to (1.2–)1.6–2.3(–2.6) μm at the tips (n = 23). Asci (79–)94–121(–137) × (3.5–)4.2–5.3(–6.2) μm (n = 96), unitunicate, long-cylindrical, with a short stipe, with eight ascospores arranged in a single fascicle, with an indistinct inamyloid to slightly amyloid apical apparatus. Ascospores (73–)90–116(–132) × (0.7–)0.8–1(–1.3), l/w = (74–)94–137(–174) (n = 89), with rounded ends, hyaline, without visible septa, without sheath or appendages.

No cultures available. No asexual morph observed.

Habitat and host range: Dead overwintered leaves of Sorbus torminalis.

Distribution: Europe; only known from northern Italy.

Holotype: Italy, Veneto, Mantova, Bosco della Fontana, on dead leaves of Sorbus torminalis, Apr. 1873, A. Magnaguti-Rondini (PAD, not seen).

Specimens examined: Italy, Veneto, Conegliano, on dead leaves of Sorbus torminalis, summer 1878, C. Spegazzini, in Saccardo, Mycoth. Ven. 1352 (WU s.n.). Same place, May 1878, C. Spegazzini, in Baglietto, Cesati & Notaris, Erb. Critt. Ital. Ser. II 727 (M-0304429, Z Myc 8040). Same place, Apr. 1879, C. Spegazzini, in Thümen, Mycoth. Univ. 1454 (M-0304428, WU s.n., ZT Myc 60357).

Notes: Due to the lack of fresh specimens, no cultures and sequence data are available for L. magnagutiana, but its morphology clearly places it in Linosporopsis. Only few historic records from northern Italy, all collected in the 1870ies, are known. We have not been able to investigate the type from PAD, which is not sent out on loan, but two additional authentic collections from the same area were available for study. As the historic material is very brittle, no useable section of the peridium could be prepared. The rosaceous host, Sorbus torminalis, and similar morphology indicates that L. magnagutiana may be conspecific with L. ochracea. However, in one locality (Bayerisches Landesarboretum “Weltwald”), where leaves of Pyrus domestica and Sorbus latifolia were heavily infected by L. ochracea, no Linosporopsis could be found on leaves of directly close-by Sorbus torminalis, indicating that they are distinct. In addition, the asci and ascospores of L. magnagutiana are slightly shorter than those of L. ochracea ((79–)94–121(–137) and (73–)90–116(–132) μm vs. (91–)108–130(–153) and (88–)103–126(–149) (n = 139) μm, respectively), and also its clypei are somewhat smaller ((109–)126–203(–294) vs. (97–)172–276(–355) μm). Therefore, for the time being, we argue for maintaining them as distinct species.

Linosporopsis ochracea (Sacc.) Voglmayr & Beenken, comb. nov. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Linosporopsis ochracea. a–c Colonies (bleached patches) on dead overwintered leaves of Pyrus communis (a), Crataegus sp. (left) and Sorbus latifolia (right) (b), and Sorbus intermedia (c), with scattered black, clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. d Close up of colony with black clypeus-like uniperitheciate pseudostromata. e–g Uniperitheciate pseudostromata from above (e), in side view (f), and in transverse section (g). h Uniperitheciate pseudostroma in transverse section. i Pseudoparenchymatous, hyaline peridium, adjacent host tissue and lower clypeus in section. j Host epidermis cells with dark brown branched hyphae. k–o Asci. p Ascospore. q Paraphysis. r–t Ascus apices. All in 3% KOH, except h, l, p, q in water; o, t in Lugol after KOH pre-treatment (a, d, g–j, l, p WU 40029; b, f, n, o, r PC 0706581, lectotype; c, e, k, m, q WU 40031, epitype; s PC 0706581; t WU 40028. Scale barsa–c 10 mm; d 500 μm; e–h 100 μm; i, k 20 μm; j, l–q 10 μm; r–t 2 μm

MycoBank: MB 833898.

Basionym. Linospora ochracea Sacc., Syll. fung. (Abellini) 2: 355. 1883.

Replaced synonym. Sphaeria ochracea Desm., Annls Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 3 16: 317. 1851, nom. illegit. Art. 53.1, non Sphaeria ochracea Pers., Syn. meth. fung. (Göttingen) 1: 18. 1801.

Pseudostromata immersed in dead overwintered leaves, reduced, forming a distinct black clypeus (97–)172–276(–355) μm wide (n = 143) on both sides of the leaf, consisting of a textura epidermoidea-intricata composed of thick-walled, dark brown, septate hyphae 1.5–3.7 μm wide mostly in dead host epidermis cells. Ascomata perithecial, scattered, solitary, immersed in dead leaf tissue, globose to depressed globose, 180–260 μm diam., with a distinct central apical papilla (45–)60–89(–114) μm wide at the base (n = 88). Peridium (22–)26–37(–41) μm wide (n = 20), hyaline, pseudoparenchymatous, of hyaline isodiametric to elongate cells, marginal peridium cells (6.2–)8.5–14.8(–17.3) × (3.7–)4.8–7.7(–10) μm (n = 25), basal peridium cells smaller, (4–)5–9.5(–11.3) × (1.7–)2.5–4.2(–5) μm (n = 26). Paraphyses unbranched, septate, thin-walled, collabent, 75–160 μm long, 3–6(–9.7) μm wide at the base and gradually tapering to 1–2 μm at the tips (n = 34). Asci (91–)108–130(−153) × (3–)4–5.5(–6.7) μm (n = 205), unitunicate, long-cylindrical, with a short stipe, with eight ascospores arranged in a single fascicle, with an indistinct inamyloid or slightly amyloid apical apparatus. Ascospores (88–)103–126(−149) × (0.8–)0.9–1.3(–1.6) μm, l/w = (62–)87–132(–174) (n = 139), filiform, with rounded ends, hyaline, without visible septa, without sheath or appendages.

Colonies on CMD and MEA white; aerial hyphae abundant. No asexual morph observed.

Habitat and host range: Dead overwintered leaves of various Rosaceae, subtribus Pyrinae; e.g., Crataegus spp., Cydonia oblonga, Malus domestica, Mespilus germanica, Pyrus spp. and Sorbus spp.

Distribution: Europe; known from Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

Typification: France, Calvados (14), Caen, Hérouville-Saint-Clair, Parc de Lébisey, on dead leaves of Crataegus monogyna and Sorbus latifolia, May 1850, M.R. Roberge, in Desmazières, Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 2099 (PC 0706581, lectotype of Linospora ochracea here designated, MBT 390206; K(M) 206803, K(M) 206804, K(M) 206805, K(M) 206,806, PC 0706579, isotypes). Germany, Bavaria, Freising, Kranzberger Forst, Bayerisches Landesarboretum “Weltwald”, on dead leaves of Sorbus intermedia, 30 Apr. 2019, L. Beenken (WU 40031, epitype of Linospora ochracea here designated, MBT 390207, isoepitype ZT Myc 59968; ex epitype culture CBS 145999 = LIO3).

Other specimens examined: Austria, Niederösterreich, Marchegg, at the railroad embankment near the river March, on dead leaf of Malus domestica, 1 May 2019, H. Voglmayr (WU 40032); Oberösterreich, Raab, Wetzlbach, on dead leaves of Pyrus communis, 23 Mar. 2019, H. Voglmayr (WU 40029; culture LIO1). France, Calvados (14), Caen, Hérouville-Saint-Clair, Parc de Lébisey, on dead leaves of Pyrus argentea, Apr. 1851, M.R. Roberge (K(M) 206645, PC 0706580); same collection data, in Desmazières, Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 2100 (K(M) 206641, K(M) 206642, K(M) 206644, PC 0706582); same collection data, in Desmazières, Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 2, Ser. 1, no. 1800 (K(M) 206643); same place, collector and host, without date (M-0304431); same place and collector, on dead leaves of Sorbus sp., without date (M-0304430). Germany, Bavaria, Freising, Kranzberger Forst, Weltwald, on dead leaves of Pyrus communis, 30 Apr. 2019, L. Beenken (WU 40030, ZT Myc 59969; culture LIO2). Switzerland, Zürich, Henggart, on dead leaves of Malus domestica, 13 May 2017, L. Beenken (WU 40028, ZT Myc 59970; culture CBS 145760 = LIO).

Notes: DNA sequence data and morphology place the species within Xylariaceae, as closest relative of L. ischnotheca. It was first described as Sphaeria ochracea by Desmazières (1851), but the name is illegitimate as it is a younger homonym of Sphaeria ochracea Pers. (1801). Therefore, Linospora ochracea Sacc., originally established as a new combination of Sphaeria ochracea Desm., is to be treated as a replacement name and represents the valid basionym.

In the protologue, Desmazières (1851) listed leaves of Crataegus, Cydonia, Mespilus, Sorbus and also Fagus as hosts; however, no collection or specimen data were given. For the specimens on Fagus, Desmazières (1852) subsequently described a distinct species, Sphaeria ischnotheca (see above). As concluded from the original material of Desmazières in PC and K, and from his notes attached to the specimen PC 0706581, the species was based on material collected by M.R. Roberge in Hérouville-Saint-Clair near Caen in May 1850, which Desmazières edited in his Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 2099. This exsiccatum contains material from Crataegus monogyna and Sorbus latifolia. From the same locality, Desmazières also distributed material from Pyrus argentea (as Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 1, no. 2100 and Pl. Crypt. N. France, Ed. 2, Ser. 1, no. 1800), under the unpublished name Sphaeria ochracea f. pyrina, which, however, does not qualify for the type, as this host is not listed in the protologue; in addition, it was collected one year later (Apr. 1851) than the type, which may be a reason why this host was not cited in the protologue.

Unlike all other accessions of L. ochracea investigated by us, which had an indistinct, inamyloid apical apparatus, the Swiss collection WU 40028 from Malus domestica showed a tiny, wedge-shaped, slightly amyloid apical apparatus after KOH pre-treatment (see Fig. 5t). However, the sequences obtained from this accession fully matched the other collections, indicating a variable iodine reaction that probably depends on the maturity and preservation of the specimen.

Key to the species of Linosporopsis

1. On leaves of Rosaceae..................................................2

1. On leaves of Fagaceae (Fagus, Quercus) or Betulaceae (Carpinus).........................................................................3

2. On leaves of Sorbus torminalis............L. magnagutiana

2. On leaves of other rosaceous hosts (Crataegus, Cydonia, Malus, Pyrus, Sorbus)......................L. ochracea

3. On leaves of Fagus; occasionally also Quercus .....................................................................L. ischnotheca

3. On leaves of Carpinus ....................................L. carpini

Discussion

The results of our molecular phylogenetic investigations confirmed the conclusions of Monod (1983) that the species treated here are not congeneric with Linospora and do not belong to Diaporthales. However, while he assumed that they belong to Ophiodothella, currently classified within Phyllachoraceae (Phyllachorales), our phylogenetic analysis placed them in a basal clade of Xylariaceae sensu stricto (Xylariales). Based on the presence of an amyloid apical ascus ring, conidia resembling Diatrypaceae and a single nuSSU rNDA sequence, Hanlin et al. (2002) assumed xylarialean affinities of Ophiodothella; however, these conclusions were based on non-type species and need to be verified by re-investigation of the generic type. No type material of the generic type, O. atromaculans (Henn.) Höhn., is extant in B where the material of Hennings is kept (R. Lücking, personal communication). However, even if xylarialean, the following features do not support that Ophiodothella is congeneric with the species treated here: an obligate parasitic lifestyle in living leaves, a tropical to subtropical distribution almost exclusively in the New World, formation of pycnidial or acervular conidiomata, lack of distinct bleaching of the substrate and morphological differences of the ascomata (Hanlin et al. 1992, 2002, 2018). Particularly the generic type, O. atromaculans, deviates significantly from our species by an extended effuse, black stromatic crust (Hennings 1904; Hanlin et al. 1992). Additional genera with solitary clypeate ascomata and filiform ascospores that were previously attributed to Xylariales include Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon; however, these have been shown to belong to Chaetosphaeriales by sequence data (Konta et al. 2017). As no suitable described genus is available within Xylariaceae, we establish the new genus Linosporopsis for them.

Sister group relationship of Linosporopsis to the Clypeosphaeria mamillana-Anthostomelloides krabiensis clade is highly supported in the ML analyses, but receives only low support in the MP analyses. Linosporopsis is similar to the latter species in solitary ascomata of similar size that are embedded in a reduced pseudostroma within the host tissue and shares a distinct clypeus and apical papilla with Clypeosphaeria mamillana. However, marked differences to Linosporopsis include ellipsoid to oblong brown ascospores; a large, wedge-shaped, strongly amyloid apical ascus apex; and, in A. krabiensis, the lack of a clypeus and of an apical papilla (Jaklitsch et al. 2016; Tibpromma et al. 2017).

Ecologically, there is evidence that Linosporopsis occupies a niche as a leaf endophyte, and there is so far no indication of parasitism. Observations in Austrian and Swiss sites with abundant sporulation of Linosporopsis ochracea on dead overwintered Pyrus and Malus leaves revealed no obvious symptoms on living Pyrus and Malus leaves during the following summer. Evidently, the life cycle of Linosporopsis is connected with that of their hosts, as the short-lived ascospores are only produced briefly after their hosts unfold their new leaves in spring. These young leaves are then infected by the ascospores to complete the life cycle, with the living leaf tissue remaining asymptomatic during the growing season. After leaf abscission, the mycelium continues growth on the fallen leaves during the winter season, causing a distinctive bleaching of the decaying leaves, and finally ascomata and ascospores are produced again in the following spring.

The filiform, hyaline ascospores of Linosporopsis are very unusual for Xylariaceae, which mostly have more or less ellipsoid, brown ascospores, and therefore, the placement of Linosporopsis within Xylariaceae sensu stricto is somewhat surprising. However, ascospore morphology has proven not to be a good character for family segregation in the Xylariales, while the asexual morphs seem to agree better with the phylogeny (Ju and Rogers 1996, 2002; Wendt et al. 2018). So far, no asexual morph is known for Linosporopsis. The hyaline, filiform spores are likely an adaptation to colonization and infection of living leaves of trees. While little understood and investigated in detail, there is strong evidence that long, curved spores are effective adaptations to facilitate attachment on vertical or otherwise challenging exposed surfaces and are therefore advantageous for successful germination and establishment on aerial plant parts (Calhim et al. 2018). It is therefore not surprising that filiform ascospores have independently evolved in leaf-inhabiting species of various ascomycete lineages. This also provides an explanation for the morphological similarities to the unrelated diaporthalean genus Linospora, which has a similar ecology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Enrique Rubio Domínguez for sending fresh material of L. ischnotheca, Rosella Marcucci (Erbario dell’Università di Padua – PAD) for providing illustrations of the type of L. faginea, the herbarium curators of K, M, and PC for loan of herbarium specimens, and Walter Till (WU) for handling the herbarium loans.

Funding information

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). HV is financially supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; project P27645-B16).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Barr ME. Podromus to nonlichenized, pyrenomycetous members of class Hymenoascomycetes. Mycotaxon. 1990;39:43–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bills GF, Gonzalez-MenendezV MJ, Platas G, Fournier J, Persoh D, Stadler M. Hypoxylon pulicicidum sp. nov. (Ascomycota, Xylariales), a pantropical insecticide-producing endophyte. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitzer J, Læssøe T, Fournier J, Kummer V, Decock C, Tichy HV, Piepenbring M, Peršoh D, Stadler M. Affinities of Phylacia and the daldinoid Xylariaceae, inferred from chemotypes of cultures and ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol Res. 2008;112:251–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhim S, Halme P, Petersen JH, Læssøe T, Bässler C, Heilmann-Clausen J. Fungal spore diversity reflects substrate-specific deposition challenges. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5356. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23292-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Jaklitsch WM, Vasilyeva LN. A preliminary overview of the Diaporthales based on large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia. 2002;94:1017–1031. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2003.11833157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements FE, Shear CL. Genera of fungi. 2. New York: H.W.Wilson; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Daranagama DA, Camporesi E, Tian Q, Liu X, Chamyuang S, Stadler M, Hyde KD. Anthostomella is polyphyletic comprising several genera in Xylariaceae. Fungal Divers. 2015;73:203–238. doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0329-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoog GS, Gerrits van den Ende AHG. Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous basidiomycetes. Mycoses. 1998;41:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmazières MJBHJ. Dix-neuvième notice sur les plantes cryptogames récemment découvertes en France. Annales des Sciences Naturelles Botanique, Série. 1851;3(16):296–330. [Google Scholar]

- Desmazières MJBHJ. Vingtième notice sur les plantes cryptogames récemment découvertes en France. Annales des Sciences Naturelles Botanique, Série. 1852;3(18):355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J, Flessa F, Peršoh D, Stadler M. Three new Xylaria species from southwestern Europe. Mycol Prog. 2011;10:33–52. doi: 10.1007/s11557-010-0671-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier Jacques, Stadler Marc, Hyde Kevin D., Duong Minh Lam. The new genus Rostrohypoxylon and two new Annulohypoxylon species from Northern Thailand. Fungal Diversity. 2010;40(1):23–36. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0026-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuckel KWGL. Symbolae Mycologicae. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Rheinischen Pilze Jahrb Nassau Ver Naturkd. 1870;23–24:1–459. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlin RT, Goh TK, Skarshaug AJ. A key to and descriptions of species assigned to Ophiodothella, based on the literature. Mycotaxon. 1992;44:103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlin RT, González M, Tortolero O, Renaud J. A new species of Ophiodothella on Casearia from Venezuela. Mycoscience. 2002;43:321–325. doi: 10.1007/S102670200047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlin RT, Owens J, Icard A, Glenn A, González M. Observations on the biology of Ophiodothella angustissima. North American Fungi. 2018;13(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hennings P. Fungi amazonici II. a cl. Ernesto Ule collecti. Hedwigia. 1904;43:242–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HM, Ju YM, Rogers JD. Molecular phylogeny of Hypoxylon and closely related genera. Mycologia. 2005;97:844–865. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HM, Lin CR, Fang MJ, Rogers JD, Fournier J, Lechat C, Ju YM. Phylogenetic status of Xylaria subgenus Pseudoxylaria among taxa of the subfamily Xylarioideae (Xylariaceae) and phylogeny of the taxa involved in the subfamily. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;54:957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM. European species of Hypocrea Part I. The green-spored species. Stud Mycol. 2009;63:1–91. doi: 10.3114/sim.2009.63.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM, Voglmayr H. Phylogenetic relationships of five genera of Xylariales and Rosasphaeria gen. nov. (Hypocreales) Fungal Divers. 2012;52:75–98. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM, Stadler M, Voglmayr H. Blue pigment in Hypocrea caerulescens sp. nov. and two additional new species in sect. Trichoderma. Mycologia. 2012;104:925–941. doi: 10.3852/11-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM, Fournier J, Rogers JD, Voglmayr H. Phylogenetic and taxonomic revision of Lopadostoma. Persoonia. 2014;32:52–82. doi: 10.3767/003158514X679272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM, Gardiennet A, Voglmayr H. Resolution of morphology-based taxonomic delusions: Acrocordiella, Basiseptospora, Blogiascospora, Clypeosphaeria, Hymenopleella, Lepteutypa, Pseudapiospora, Requienella, Seiridium and Strickeria. Persoonia. 2016;37:82–105. doi: 10.3767/003158516X690475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson H, Laessøe T, Stenlid J. Molecular and morphological investigation of the genus Daldinia in Northern Europe. Mycol Res. 2000;104:275–280. doi: 10.1017/S0953756299001719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YM, Rogers JD (1996) A revision of the genus Hypoxylon. Mycologia memoir no.° 20. APS press, St. Paul, 365 pp

- Ju YM, Rogers JD. The genus Nemania (Xylariaceae) Nova Hedwigia. 2002;74:75–120. doi: 10.1127/0029-5035/2002/0074-0075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konta S, Hongsanan S, Liu JK, Eungwanichayapant PD, Jeewon R, Hyde KD, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Boonmee S. Leptosporella (Leptosporellaceae fam. nov.) and Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon (Linocarpaceae fam. nov.) are accommodated in Chaetosphaeriales. Mycosphere. 2017;8:1943–1974. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/8/10/16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koukol O., Kelnarová I., Černý K. Recent observations of sooty bark disease of sycamore maple in Prague (Czech Republic) and the phylogenetic placement ofCryptostroma corticale. Forest Pathology. 2014;45(1):21–27. doi: 10.1111/efp.12129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert E, Fournier J, Peršoh D, Luangsa-ard JJD, Stadler M. New Hypoxylon species from Martinique and new evidence on the molecular phylogeny of Hypoxylon based on ITS rDNA and β- tubulin data. Fungal Divers. 2014;64:181–203. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0264-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert E, Sir EB, Lambert C, Hyde KD, Hladki AI, Romero AI, Rohde M, Stadler M. Phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic resolution of the genus Annulohypoxylon (Xylariaceae) including four new species. Fungal Divers. 2017;85:1–43. doi: 10.1007/s13225-016-0377-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li QR, Kang JC, Hyde KD (2015) Two new species of the genus Collodiscula (Xylariaceae) from China. Mycol Prog 14:52

- Mejía LC, Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Sogonov MV, White JF. Phylogenetic placement and taxonomic review of the genus Cryptosporella and its synonyms Ophiovalsa and Winterella (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) Mycol Res. 2008;112:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabolfathy M, Ju YM, Hsieh HM, Rogers JD. Obolarina persica sp. nov., associated with dying Quercus in Iran. Mycoscience. 2013;54:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2012.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monod M. Monographie taxonomique des Gnomoniaceae (Ascomycètes de'l ordre des Diaporthales) Beihefte zur Sydowia. 1983;9:1–315. [Google Scholar]

- Pažoutová S, Srutka P, Holuša J, Chudickova M, Kolarik M. The phylogenetic position of Obolarina dryophila (Xylariales) Mycol Prog. 2010;9:501–507. doi: 10.1007/s11557-010-0658-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez F, Gonzalez V, Platas G, Sanchez-Ballesteros J. Molecular phylogenetic studies within the family Xylariaceae based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Fungal Divers. 2008;31:111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rabenhorst GL. Fungi Europaei. Cent. 21 und 22. Hedwigia. 1876;15:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo PA. Fungi Veneti novi vel critici vel mycologiae Veneti addendi. Series VI Michelia. 1877;1(1):1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo PA. Fungi Veneti novi vel critici vel mycologiae Venetae addendi. Series IX Michelia. 1878;1(4):361–445. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake IC, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Hyde KD, Bhat JD, EBG J, MK EH, Dai DQ, Dagaranagama DA, Dayarathne MC, Goonasekara ID, Konta S, Li WL, Shang QJ, Stadler M, Wijayawardene NN, Xiao XP, Norphanphoun C, Li QR, Liu XZ, Bahkali AH, Kang JC, Wang Y, Wen TC, Wendt L, Xu JC, Camporesi E. Towards unraveling relationships in Xylariomycetidae (Sordariomycetes) Fungal Divers. 2015;73:73–144. doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0340-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestro D, Michalak I. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org Divers Evol. 2012;12:335–337. doi: 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sir EB, Lambert C, Wendt L, Hladki AI, Romero AI, Stadler M. A new species of Daldinia (Xylariaceae) from the argentine subtropical montane forest. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1378–1388. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/7/9/11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sogonov MV, Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Farr DF, White JF. The type species of genus Gnomonia, G. gnomon, and the closely related G. setacea. Sydowia. 2005;57:102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sogonov MV, Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Mejía LC, White JF. Leaf-inhabiting genera of the Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales. Stud Mycol. 2008;62:1–79. doi: 10.3114/sim.2008.62.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M, Fournier J, Læssøe T, Chlebicki A, Lechat C, Flessa F, Rambold G, Peršoh D. Chemotaxonomic and phylogenetic studies of Thamnomyces (Xylariaceae) Mycoscience. 2010;51:189–207. doi: 10.1007/S10267-009-0028-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M, Kuhnert E, Peršoh D, Fournier J. The Xylariaceae as model example for a unified nomenclature following the “one fungus-one name” (1F1N) concept. Mycol Int J Fungal Biol. 2013;4:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M, Læssøe T, Fournier J, Decock C, Schmieschek B, Tichy HV, Peršoh D. A polyphasic taxonomy of Daldinia (Xylariaceae) Stud Mycol. 2014;77:1–143. doi: 10.3114/sim0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis E. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP* 4.0b10: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods) Sunderland: Sinauer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tang AM, Jeewon R, Hyde KD (2009) A re-evaluation of the evolutionary relationships within the Xylariaceae based on ribosomal and protein-coding gene sequences. Fungal Divers 34:155–153

- Thiers B (2019) Index Herbariorum: a global directory of public herbaria and associated staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ Accessed 25 Nov. 2019

- Tibpromma S, Daranagama DA, Boonmee S, Promputtha I, Nontachaiyapoom S, Hyde KD. Anthostomelloides krabiensis gen. et sp. nov. (Xylariaceae) from Pandanus odorifer (Pandanaceae) Turkish J Bot. 2017;40:107–116. doi: 10.3906/bot-1606-45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triebel D, Scholz P (2019) IndExs – index of Exsiccatae. Botanische Staatssammlung München. http://indexs.botanischestaatssammlung.de/ Accessed 25 Nov. 2019

- Triebel D, Peršoh D, Wollweber H, Stadler M. Phylogenetic relationships among Daldinia, Entonaema and Hypoxylon as inferred from ITS nrDNA sequences. Nova Hedwigia. 2005;80:25–43. doi: 10.1127/0029-5035/2005/0080-0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/JB.172.8.4238-4246.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Jaklitsch WM. Prosthecium species with Stegonsporium anamorphs on Acer. Mycol Res. 2008;112:885–905. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Jaklitsch WM. Molecular data reveal high host specificity in the phylogenetically isolated genus Massaria (Ascomycota, Massariaceae) Fungal Divers. 2011;46:133–170. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0078-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Mehrabi M. Molecular phylogeny and a new Iranian species of Caudospora (Sydowiellaceae, Diaporthales) Sydowia. 2018;70:67–80. doi: 10.12905/0380.sydowia70-2018-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr Hermann, Rossman Amy Y., Castlebury Lisa A., Jaklitsch Walter M. Multigene phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Melanconiella (Diaporthales) Fungal Diversity. 2012;57(1):1–44. doi: 10.1007/s13225-012-0175-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Akulov OY, Jaklitsch WM. Reassessment of Allantonectria, phylogenetic position of Thyronectroidea, and Thyronectria caraganae sp. nov. Mycol Prog. 2016;15:921. doi: 10.1007/s11557-016-1218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Gardiennet A, Jaklitsch WM. Asterodiscus and Stigmatodiscus, two new apothecial dothideomycete genera and the new order Stigmatodiscales. Fungal Divers. 2016;80:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s13225-016-0356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H., Castlebury L.A., Jaklitsch W.M. Juglanconis gen. nov. on Juglandaceae, and the new family Juglanconidaceae (Diaporthales) Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2017;38(1):136–155. doi: 10.3767/003158517X694768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Friebes G, Gardiennet A, Jaklitsch WM. Barrmaelia and Entosordaria in Barrmaeliaceae (fam. nov., Xylariales), and critical notes on Anthostomella-like genera based on multi-gene phylogenies. Mycol Prog. 2018;17:155–177. doi: 10.1007/s11557-017-1329-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H, Jaklitsch WM, Mohammadi H, Kazemzadeh Chakusary M. The genus Juglanconis (Diaporthales) on Pterocarya. Mycol Prog. 2019;18:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s11557-018-01464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt L, Sir EB, Kuhnert E, Heitkämper S, Lambert C, Hladki AI, Romero AI, Luangsa-ard JJ, Srikitikulchai P, Peršoh D, Stadler M. Resurrection and emendation of the Hypoxylaceae, recognised from a multigene phylogeny of the Xylariales. Mycol Prog. 2018;17:115–154. doi: 10.1007/s11557-017-1311-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werle E, Schneider C, Renner M, Völker M, Fiehn W. Convenient single-step, one tube purification of PCR products for direct sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4354–4355. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Castlebury LA, Miller AN, Huhndorf SM, Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Rossman AY, Rogers JD, Kohlmeyer J, Volkmann-Kohlmeyer B, Sung GH. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia. 2006;98:1076–1087. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]