Abstract

Poultry of different ages may have to be killed on‐farm for purposes other than slaughter (in which slaughtering is defined as being for human consumption) either individually or on a large scale (e.g. because unproductive, for disease control, etc.). The processes of on‐farm killing that were assessed are handling and stunning and/or killing methods (including restraint). The latter were grouped into four categories: electrical methods, modified atmosphere, mechanical methods and lethal injection. In total, 29 hazards were identified and characterised, most of these regard stunning and/or killing. Staff were identified as origin for 26 hazards and 24 hazards were attributed to lack of appropriate skill sets needed to perform tasks or due to fatigue. Specific hazards were identified for day‐old chicks killed via maceration. Corrective and preventive measures were assessed: measures to correct hazards were identified for 13 hazards, and management showed to have a crucial role in prevention. Eight welfare consequences, the birds can be exposed to during on‐farm killing, were identified: not dead, consciousness, heat stress, cold stress, pain, fear, distress and respiratory distress. Welfare consequences and relevant animal‐based measures were described. Outcome tables linking hazards, welfare consequences, animal‐based measures, origins, preventive and corrective measures were developed for each process. Mitigation measures to minimise welfare consequences were also proposed.

Keywords: poultry, on‐farm killing, hazards, animal welfare consequences, ABMs, preventive/corrective measures

Summary

In 2009, the European Union (EU) adopted Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 ‘on the protection of animals at the time of killing’, which was prepared on the basis of two Scientific Opinions adopted by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2004 and 2006. Successively (in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2017), EFSA produced other Scientific Opinions related to this subject.

In parallel, since 2005, the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) has developed in its Terrestrial Animal Health Code over two chapters: (i) Slaughter of animals (Chapter 7.5); and (ii) Killing of animals for disease control purposes (Chapter 7.6). OIE has created an ad hoc Working Group (WG) to revise these two chapters.

Against this background, the European Commission requested EFSA to write a Scientific Opinion providing an independent view on the killing of domestic birds for purposes other than slaughter, which includes: (i) large‐scale killings outside slaughterhouses for depopulation to control diseases and for other similar situations, like environmental contamination, disaster management, etc.; and (ii) on‐farm killing of unproductive animals.

With specific reference to handling, restraint, stunning/killing, and unacceptable methods, procedures or practices on welfare grounds, EFSA was asked to: identify the animal welfare hazards and their possible origins in terms of facilities/equipment and staff (Term of Reference (ToR) 1); define qualitative or measurable criteria to assess performance on animal welfare (animal‐based measures (ABMs)) (ToR2); provide preventive and corrective measures (structural or managerial) to address the hazards identified (ToR3); and point out specific hazards related to species or types of animals (e.g. young ones, etc.; ToR4). In addition, the European Commission asked EFSA also to provide measures to mitigate the welfare consequences that can be caused by the identified hazards.

This Scientific Opinion aims at updating the above‐reported EFSA outputs by reviewing the most recent scientific publications and providing the European Commission with a sound scientific basis for future discussions at international level on the welfare of animals in the context of killing for purposes other than slaughter (in which slaughtering is defined as being for human consumption).

The animal species that are considered in this assessment are the ones that pertain to the category of ‘poultry’ as defined by the OIE that can be put in crates and containers, such as chickens, turkeys, quails, ducks and geese and game birds. It does not concern ratites, which are free moving animals.

The mandate also requested a list of unacceptable methods, procedures or practices that need to be analysed in terms of the above welfare aspects. Methods, procedures or practices cannot be subjected to a risk assessment procedure if there is no published scientific evidence related to these. In the light of this, Chapters 7.5.10 and 7.6 of the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2018) list principles and practices considered to be unacceptable, and the Panel has no scientific arguments to disagree with these statements.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 defines ‘killing’ as ‘any intentional induced process which causes the death of an animal’; and the ‘related operations’ are ‘operations that take place in the context and at the location where the animals are killed’. This Opinion concerns the killing of poultry for purposes other than slaughter (in which slaughtering is defined as being for human consumption), which does not involve slaughterhouses (so‐called on‐farm killing) and the related operations, which here are called ‘processes’.

To address the mandate, two main approaches have been used to develop this Opinion: (i) literature search; followed by (ii) expert opinion through Working Group (WG) discussion. Two literature searches have been carried out to identify peer‐reviewed scientific evidence providing information on the aspects requested by the ToRs (i.e. description of the processes, identification of welfare hazards, origin, preventive and corrective measures, welfare consequences and related ABMs) on the topic of ‘killing of poultry for purposes other than slaughter (on‐farm killing of poultry)’.

From the available literature and their own knowledge, the WG experts identified the processes that should be included in the assessment and produced a list containing the possible welfare hazards characterising each process related to on‐farm killing of poultry. To address the ToRs, experts identified the origin of each hazard (ToR1) and related preventive and corrective measures (ToR3), along with the possible welfare consequences of the hazards and relevant ABMs (ToR2). Measures to mitigate the welfare consequences were also considered. Specific hazards were identified for day‐old chicks killed via maceration (ToR4). In addition, uncertainty analysis on the hazard identification has been also carried out and it was limited to the quantification of the probability of false‐negative or false‐positive hazards.

The processes assessed in this Opinion are handling and stunning/killing methods. The description of the restraint, when it is needed, has been included in the assessment of the relevant stunning/killing method.

As this Opinion will be used by the European Commission to address the OIE standards, more stunning/killing methods than those reported in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 have been considered. However, among the methods that world‐wide are used for on‐farm killing, the following criteria have been applied for the selection of stunning/killing methods to include in this assessment: (i) all methods with described technical specifications known by the experts and not only the methods described in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009; (ii) methods currently used for stunning/killing of birds, and those which are still under development but are likely to become commercially applicable; and (iii) methods for which the welfare aspects (in terms of welfare hazards, welfare consequences, ABMs, preventive and corrective measures) are described sufficiently in the scientific literature. Applying these criteria, some methods that may be applied world‐wide have not been included in the current assessment.

The stunning and/or killing methods that have been identified as relevant for poultry can be grouped in four categories: (1) electrical; (2) mechanical; (3) modified atmospheres; and (4) lethal injection.

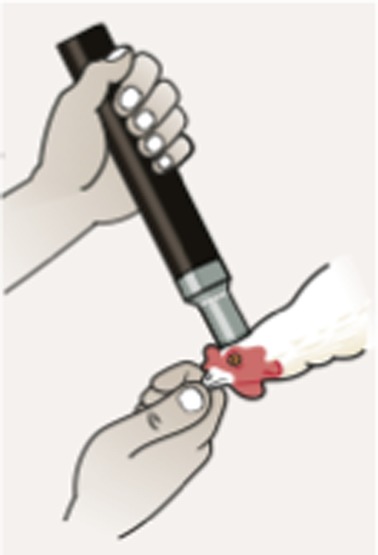

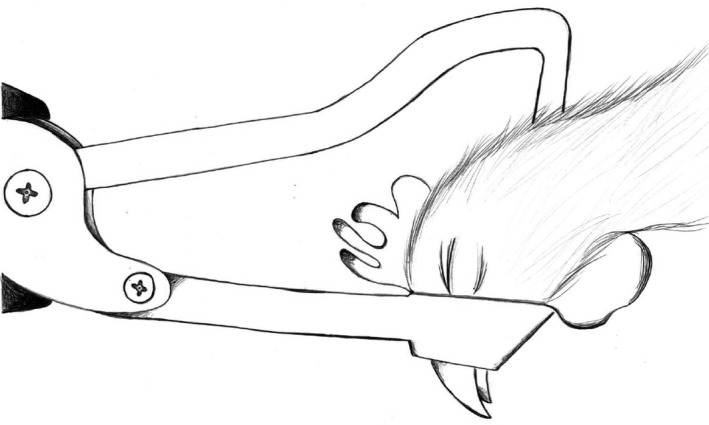

Electrical methods include waterbath, head‐only and head to body. Head only is a simple (reversible) stunning method that does not lead to death; therefore, it needs to be followed by a killing method. Modified atmosphere methods include whole house gassing, whole house gassing with gas‐filled foam, gas mixtures in containers, low atmospheric pressure stunning (LAPS). Mechanical methods include captive bolt, percussive blow to the head, maceration of day‐old chicks, cervical dislocation, neck cutting, decapitation and brain piercing. Some of these can be used as stunning and killing methods; whereas cervical dislocation, decapitation and piercing devices are considered pure killing methods and, therefore, they need to be applied on unconscious animals. Lethal injection is the intravenous injection of a lethal dose of anaesthetic drugs that cause rapid loss of consciousness followed by death; it should be administered strictly following the manufacturer's instructions on dose, route and rate of administration.

In this Opinion, for each process related to on‐farm killing, a description on how it is technically and practically carried out and how the birds are kept (e.g. if still in containers or in a restraint device) is provided. In addition, for each process, a list of the main hazards that can occur and the relevant welfare consequences that the hazards can cause, is reported. In some specific cases ABMs are also provided as examples.

To answer ToR1, in total, 29 welfare‐related hazards have been identified during on‐farm killing of poultry. All the processes described in this Opinion have hazards; about the stunning/killing methods, some methods present hazards related to the restraint of birds (i.e. electrical and mechanical methods, lethal injection) other methods to the induction phase to unconsciousness (modified atmosphere methods).

Some of these hazards are common to different processes (e.g. inversion) or stunning/killing methods (e.g. manual restraint). Hazards linked to failure in provoking death are the most represented ones. Some hazards are inherent to the stunning/killing method and cannot be avoided (e.g. shackling in waterbath), other hazards originate from suboptimal application of the method, mainly due to unskilled staff (e.g. rough handling, use of wrong parameters e.g. for electrical methods). In fact, most of the hazards (26) had staff as origin and 24 hazards could be attributed to lack of appropriate skill sets needed to perform tasks or due to fatigue.

The uncertainty analysis on the set of hazards for each process provided in this Opinion revealed that the experts were 90–95% certain that they identified the main and most common welfare hazards considered in this assessment according to the three criteria described in the Interpretation of ToRs. However, when considering a global perspective (due to the lack of documented evidence on all possible variations in the processes and methods being practised on a world‐wide scale), the experts were 95–99% certain that at least one welfare hazard is missing. On the possible inclusion of false‐positive hazards, the experts were 95–99% certain that all listed hazards exist during on‐farm killing of poultry. This certainty applies to all processes described in this Opinion except the hazard ‘expansion of gases in the body cavity’ during stunning/killing with LAPS, in which the lack of field experience and of scientific data reduces the level of certainty to 33–66%.

The mandate also asked to define qualitative or measurable (quantitative) criteria to assess performance (i.e. consequences) on animal welfare (ABMs; ToR2); this ToR has been addressed by identifying the negative consequences on the welfare (so‐called welfare consequences) occurring to the birds due to the identified hazards and the relevant ABMs that can be used to assess qualitatively or quantitatively these welfare consequences. Eight welfare consequences have been identified in the context of on‐farm killing of poultry: not dead (after application of killing method), consciousness (after application of killing method), heat stress, cold stress, pain, fear, distress and respiratory distress. Birds experience these welfare consequences only when they are conscious.

Animal welfare consequences can be the result of single or several hazards. The combination of hazards would lead to a cumulative effect on the welfare consequences (e.g. pain due to injury caused by rough handling during catching will lead to more severe pain during shackling).

List and definitions of ABMs to be used for assessing the welfare consequences have been provided in this Opinion. However, under certain circumstances, not all the ABMs can be used because of low feasibility. Even if welfare consequences cannot be assessed during on‐farm killing of poultry, it does not imply they do not exist. In fact, if the hazard is present, it should be assumed that also the related welfare consequences are experienced by the birds.

In response to ToR3, the preventive and corrective measures for the identified hazards have been identified and described. Some of these are specific for a hazard, others can apply to multiple hazards (e.g. staff training and rotation). For most of the hazards (23), preventive measures can be put in place and management showed to have a crucial role in prevention. Corrective measures were identified for 13 hazards; when they are not available or feasible to put in place, actions to mitigate the welfare consequences caused by the identified hazards should be put in place.

Finally, outcome tables linking all the mentioned aspects requested by the ToRs (identification of welfare hazards, origin, preventive and corrective measures, welfare consequences and related ABMs) have been produced for each process of on‐farm killing of poultry to provide an overall outcome, in which all retrieved information is presented concisely. Conclusions and recommendations of this Scientific Opinion are mainly based on the outcome tables.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

The European Union adopted in 2009 Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/20091 on the protection of animals at the time of killing. This piece of legislation was prepared on the basis of two EFSA Opinions respectively adopted in 20042 and 20063. The EFSA provided additional Opinions related to this subject in 20124, 20135 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10, 201411 , 12, 201513 and 201714 , 15.

In parallel, since 2005, the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) has developed in its Terrestrial Animal Health Code two chapters covering a similar scope:

Slaughter of animals (Chapter 7.5).

Killing of animals for disease control purposes (Chapter 7.6).

The chapter on the slaughter of animals covers the following species: cattle, buffalo, bison, sheep, goats, camelids, deer, horses, pigs, ratites, rabbits and poultry (domestic birds as defined by the OIE).

The OIE has created an ad hoc WG with the view to revise the two chapters.

Against this background, the Commission would like to request the EFSA to review the scientific publications provided and possibly other sources to provide a sound scientific basis for future discussions at international level on the welfare of animals in the context of slaughter (i.e. killing animals for human consumption) or other types of killing (killing for other purposes than slaughter).

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

The Commission therefore considers it opportune to request EFSA to give an independent view on the killing of animals for purposes other than slaughter:

free moving animals (cattle, buffalo, bison, sheep, goats, camelids, deer, horses, pigs, ratites);

animals transported in crates or containers (i.e. rabbits and domestic birds).

The request focuses on the cases of large‐scale killings that take place for depopulation for disease control purposes and for other similar situations (environmental contamination, disaster management, etc.) outside slaughterhouses.

The request also considers in a separate section the killing of unproductive animals that might be practised on‐farm (day‐old chicks, piglets, pullets, etc.).

The request includes the following issues:

handling

restraint

stunning/killing

unacceptable methods, procedures or practices on welfare grounds.

For each process or issue in each category (i.e. free moving, in crates or containers), the EFSA will:

ToR1: Identify the animal welfare hazards and their possible origins (facilities/equipment, staff);

ToR2: Define qualitative or measurable criteria to assess performance on animal welfare (animal‐ based measures);

ToR3: Provide preventive and corrective measures to address the hazards identified (through structural or managerial measures);

ToR4: Point out specific hazards related to species or types of animals (young, with horns, etc.).

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

This Scientific Opinion concerns the killing for purposes other than slaughter of poultry [as defined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, 2018)]16 that can be put in crates and containers, such as chickens, turkeys, quails, ducks and geese, and game birds, whereas it will not concern ratites, which are free moving animals that will be treated in another Scientific Opinion.

The European Commission asked EFSA to provide an independent view on the killing of poultry for purposes other than slaughter that takes place involving: (i) large‐scale killings on‐farm (depopulation for disease control purposes and for other similar situations such as: environmental contamination, disaster management, etc.); and (ii) killing on‐farm of unproductive animals. The latter can occur for health, welfare or economic reasons and can be split in two subcategories: (a) large‐scale killing of unproductive birds; and (b) individual killing of unproductive, unhealthy or injured birds. For each of these scenarios, several welfare aspects need to be analysed (including e.g. welfare hazards, welfare consequences and preventive/corrective measures).

This Opinion will use definitions related to the killing of poultry provided by Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 of 24 September 200917 on the protection of animals at the time of killing, and that entered into force in January 2013. The Regulation defines ‘killing’ as any intentional induced process that causes the death of an animal; and the ‘related operations’ are operations that take place in the context and at the location where the animals are killed. In the context of this Opinion, related operations are called ‘processes’.

The processes that will be assessed in this Opinion are: (1) handling; and (2) stunning/killing methods.

The stunning/killing methods that have been identified as relevant for poultry and they can be grouped in four categories: (1) electrical; (2) mechanical; (3) modified atmospheres; and (4) lethal injection.

The assessment of the relevant stunning/killing method will include a description of the restraint when it is needed.

Due to the diversity of available stunning/killing methods, in this Opinion the assessment of hazards, welfare consequences, related animal‐based measures (ABMs) and mitigation measures, hazard's origin of hazards and preventive/corrective actions will be considered separately for each method.

The mandate requests EFSA to identify hazards at different stages (processes) of killing for purposes other than slaughter and their relevant origins in terms of equipment/facilities or staff (ToR1). This Opinion will report the hazards that can occur during killing of poultry for purposes other than slaughter (in which slaughtering is defined as being for human consumption) and that does not involve slaughterhouses (so‐called on‐farm killing). In this context, ‘facilities’ has not been recognised as a possible origin category for the hazards, therefore only staff and equipment have been considered as origins.

The on‐farm killing can be performed using several stunning/killing methods, some of which are specific to on‐farm killing while others are commonly practised in slaughterhouses (for slaughter) but also applicable during on‐farm killing. For stunning/killing methods that can be used for slaughtering and also for on‐farm killing, some hazards may occur in the two scenarios (slaughtering and on‐farm killing; e.g. ‘shackling’ for waterbath), whereas some other hazards may not apply to the context of on‐farm killing (e.g. hazards related to the facilities in the slaughter plant, such as: ‘drops, curves and inclination of shackle line’ for waterbath; for details see EFSA AHAW Panel, 2019).

Additionally, the mandate does not specify the level of detail to be considered for the definition of ‘hazard’. One hazard could be subdivided into multiple ones depending on the chosen level of detail. For example, the hazard ‘inappropriate electrical parameters’ for electrical stunning/killing methods, could be further subdivided into ‘wrong choice of electrical parameters or equipment’, ‘poor or lack of calibration’, ‘voltage/current applied is too low’, ‘frequency applied is too high for the amount of current delivered’. For this Opinion, it was agreed to define hazards by a broad level of detail (‘inappropriate electrical parameters’ in the example above). Birds experience welfare consequences due to presence of hazards only when they are conscious.

The mandate also asks to define qualitative or measurable (quantitative) criteria to assess performance (i.e. consequences) on animal welfare (ABMs; ToR2); this ToR has been addressed by identifying the negative consequences on the welfare (so‐called welfare consequences) occurring to the birds due to the identified hazards and the relevant ABMs that can be used to assess qualitatively or quantitatively these welfare consequences. In some circumstances, it might be that no ABMs exist or are not feasible to use in the context of on‐farm killing of birds; in these cases, emphasis to the relevant available measures to prevent the hazards or to mitigate the welfare consequences will be given.

In this Opinion, in the description of the processes, the relevant welfare consequences that the birds can experience when exposed to hazards will be reported. The mandate does not request the ranking of the identified hazards in terms of severity, magnitude and frequency of the welfare consequences that they can cause.

The description of preventive and corrective measures for the identified hazards will be structured in two main categories: (i) structural and (ii) managerial (ToR3). When corrective measures for the hazards are not available or feasible to put in place, actions to mitigate the welfare consequences caused by the identified hazards will be discussed. In addition, it will be assessed whether specific categories or species of poultry might be subjected to specific hazards (ToR4).

In response to an additional request from the EC, measures to mitigate the welfare consequences will also be described under ToR2.

As this Opinion will be used by the European Commission to address the OIE standards, it will consider more stunning/killing methods than those reported in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009.

Among the methods that world‐wide are used for on‐farm killing, EFSA has applied the following criteria for the selection of stunning/killing methods to include in this assessment: (i) all methods with described technical specifications known by the experts and not only the method described in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009; (ii) methods currently used for stunning/killing of birds, and those that are still under development but are likely to become commercially applicable; and (iii) methods for which the welfare aspects (in terms of welfare hazards, welfare consequences, ABMs, preventive and corrective measures) are described sufficiently in the scientific literature.

Applying these criteria will result in not including nor describing in this Opinion some practices that may be applied world‐wide.

The mandate also requests a list of unacceptable methods, procedures or practices that needs to be analysed in terms of the above welfare aspects. The Panel considers that there are two problems with this request. First, the question of what practices are ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ cannot be answered by a scientific risk assessment, but it involves e.g. ethical and socioeconomic considerations that need to be weighed by the risk managers. Second, methods, procedures or practices cannot be subjected to a risk assessment procedure if there is no published scientific evidence related to these. In the light of this, Chapters 7.5.10 and 7.6 of the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code (OIE, 2018) list principles and practices that are considered to be unacceptable, and the Panel has no scientific arguments to disagree with these statements.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Data from literature

Information from the papers selected as relevant from the literature searches described in Section 2.2.1 and from additional literature identified by the WG experts was used for a narrative description and assessment to address ToR1 to ToR4 (see relevant sections in the chapter on Assessment).

2.1.2. Data from expert opinion

The data obtained from the literature were complemented by the WG experts’ opinion to identify the origins of hazards, welfare consequences, ABMs and hazard preventive, and corrective measures relevant for the current assessment.

2.2. Methodologies

To address the questions formulated by European Commission in ToR1 to ToR4, two main approaches were used to develop this Opinion: (i) literature search; followed by (ii) expert opinion through WG discussion. These methodologies were used to address the mandate extensively (see relevant sections in the chapter on Assessment) and also in a concise way with development of outcome tables (see Section 2.2.2.1).

The general principle adopted in the preparation of this Opinion was that relevant reference(s) would be cited in the text when published scientific literature is available, and expert opinion would be used when no published scientific literature is available or to complete the results retrieves.

2.2.1. Literature searches

Two literature searches (LS) were carried out to identify peer‐reviewed scientific evidence providing information on the aspects requested by the ToRs (i.e. description of the processes, identification of welfare hazards, origin, preventive and corrective measures, welfare consequences and related ABMs) on the topic of ‘killing of poultry for purposes other than slaughter (on‐farm killing of poultry)’: (1) the first search (Search 1) was a broad literature search under the framework of ‘welfare of poultry at slaughter and killing’ (for details; see Appendix A of EFSA AHAW Panel, 2019). For the current Opinion, the publications obtained from this first search were screened for their relevance to the context of ‘on‐farm killing of poultry’ and assessed: 21 papers resulted pertaining to on‐farm killing of poultry; and (2) a second literature search (Search 2) aimed specifically at retrieving additional publications relevant to on‐farm killing of poultry. From this search, five additional relevant papers resulted.

Full details of the Search 2 protocol, strategies and results are provided in Appendix A to this Opinion.

In addition, the reference list of relevant review articles and key reports was checked for further relevant articles and experts were invited to propose any additional relevant publications.

2.2.2. Expert opinion through Working Group discussion

The WG experts firstly described the processes of killing and specifically that stunning/killing methods should be considered for the current assessment.

The experts then produced, from the available literature and their own knowledge, a list containing the possible welfare hazards characterising each process related to on‐farm killing of poultry. To address the ToRs, experts then identified the origin of each hazard (ToR1) and related preventive and corrective measures (ToR3), along with the possible welfare consequences of the hazards and relevant ABMs (ToR2). Measures to mitigate the welfare consequences were also considered.

ToR1 of the mandate asks to identify the origins of the hazards in terms of staff or facilities/equipment. When discussing the origins, it was agreed that in the on‐farm killing context, the term ‘facilities’ has not been recognised as a possible origin category for the hazards. Therefore, only staff and equipment have been considered as origins. Moreover, it was considered necessary to explain the origins further by detailing what actions from the staff or features from equipment can cause the hazard. Therefore, for each ‘origin category’ (staff or equipment), relevant ‘origin specifications’ have been identified by expert opinion.

2.2.2.1. Development of outcome tables to answer the ToRs

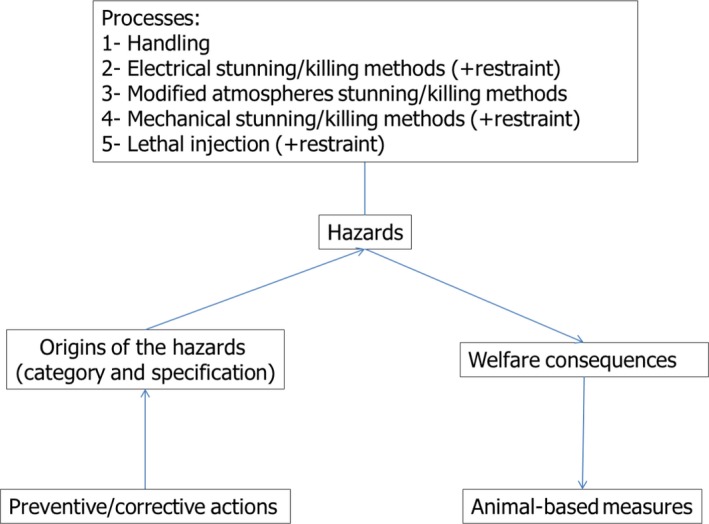

A conceptual model has been developed following EFSA's Guidance on risk assessment in animal welfare (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2012a) that shows the interrelationships between aspects corresponding to the different ToRs (see Figure 1), and the main results of the current assessment have been summarised in tables (so‐called outcome tables, see Section 3.10).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model reproducing interrelationships between the aspects corresponding to the different ToRs

The outcome tables link all the mentioned aspects requested by ToR1, ToR2 and ToR3 of the mandate and were produced to provide an overall outcome for each process of on‐farm killing of poultry, in which all retrieved information is presented concisely (see description of the structure below and, for details, Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19–20). Conclusions and recommendations of this Scientific Opinion are mainly based on the outcome tables.

Table 8.

Outcome table on ‘handling (catching and moving) of birds’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), with relevant welfare consequences, ABMs, origin of hazards and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People entering the house (3.6.1.1) | Fear | Staff | Some methods require catching and removal of birds and some other methods require preparation of the house | None (unavoidable as part of the method) | None |

| Rough handling of the birds (3.6.1.2) | Pain, fear, distress | Staff, equipment | Unskilled personnel, operator fatigue, high throughput rate, poorly designed containers (with small openings) |

|

None |

| Unexpected loud noise (3.6.1.3) | Fear | Staff, equipment | Staff shouting, machine noise, killing method |

|

None |

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Pain, fear | Staff | Carrying of birds by their legs |

|

None |

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | The process of handling implies to manually restraint the birds | None (unavoidable as part of the process) | None |

| ABMs: vocalisations, flight, injuries, wing flapping, attempt to regain posture | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 9.

Outcome table on ‘electrical waterbath stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Pain, fear | Equipment | Shackling | None | None |

| Shackling (3.6.1.6) | Pain, fear | Equipment | Shackling is part of the method | None | None |

| Inappropriate shackling (3.6.1.7) | Pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, operator fatigue, rough handling during catching, crating and uncrating, fast line speed, size and design of the shackle inappropriate to the bird size, force applied during shackling |

|

Shackle correctly |

| Pre‐stun shocks (3.6.1.8) | Pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Rough handling of birds during shackling, shackling of birds with broken or dislocated wings, poor setting up of equipment, absence of breast comfort plates, inappropriate shackle size, inappropriate positioning of the waterbath in relation to the shackle line and/or bird size, wing flapping at the entrance to the waterbath, overflow of electrified water at the entrance to the waterbath, lack of an electrically isolated entry ramp |

|

None |

| Poor electrical contact (3.6.1.9) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, inappropriate shackling practices (e.g. shackling of small/underweight birds, shackling by one leg), poor maintenance of equipment, poor or intermittent contact between shackles and earth bar, due to incorrect positioning and dirtiness, shackles inappropriate to the size of the birds, dirty and dry shackles |

|

None |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, high throughput rate in a multiple birds waterbath stunning, poor setting up of the waterbath |

|

None |

| Inappropriate electrical parameters (3.6.1.11) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Wrong choice of electrical parameters or equipment, poor or lack of calibration, voltage/current applied is too low, frequency applied is too high for the amount of current delivered, lack of skilled operators, lack of monitoring of stun quality, lack of adjustments the settings to meet the requirements |

|

None |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, attempt to regain posture; wing flapping, vocalisations, withdrawal reaction, muscle jerks, escape attempts | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 10.

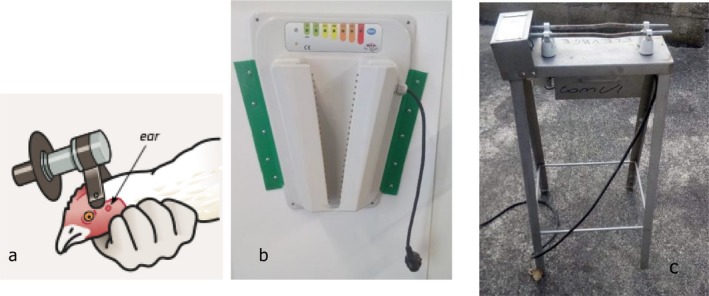

Outcome table on ‘head‐only electrical stunning’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | Presentation of birds to the method is required | None | None |

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Fear | Equipment | Restraint in a cone | Avoid the inversion of conscious animals | None |

| Poor electrical contact (3.6.1.9) | Consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, staff fatigue, incorrect placement of the electrodes, poorly designed and maintained equipment, intermittent contact |

|

None |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, high throughput rate |

|

None |

| Inappropriate electrical parameters (3.6.1.11) | Consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Wrong choice of electrical parameters or equipment, poor or lack of calibration, voltage/current applied is too low, frequency applied is too high for the amount of current delivered, lack of skilled operators, lack of monitoring of stun quality, lack of adjustments to the settings to meet the requirements |

|

None |

| Prolonged stun‐to‐kill interval (3.6.1.12) | Consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, too long time between stunning and the application of the killing method |

|

None |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, wing flapping, vocalisations, attempt to regain posture, escape attempts | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 11.

Outcome table on ‘head‐to‐body electrical stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Shackling or restraint in a cone | Avoid the inversion of conscious animals | None |

| Shackling (3.6.1.6) | Pain, fear | Equipment | Shackling is part of the method | Restraint in a cone | None |

| Inappropriate shackling (3.6.1.7) | Pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, operator fatigue, size and design of the shackle inappropriate to the bird size, force applied during shackling |

|

Shackle correctly |

| Poor electrical contact (3.6.1.9) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, staff fatigue, incorrect placement of the electrodes, poorly designed and maintained equipment, intermittent contact |

|

None |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, high throughput rate |

|

None |

| Inappropriate electrical parameters (3.6.1.11) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Wrong choice of electrical parameters or equipment, poor or lack of calibration, voltage/current applied is too low, frequency applied is too high for the amount of current delivered, lack of skilled operators, lack of monitoring of stun quality, lack of adjustments to the settings to meet the requirements |

|

Use appropriate electrical parameters |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, wing flapping, vocalisations, attempt to regain posture, escape attempts | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 12.

Outcome table on ‘whole house gassing stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected loud noise (3.6.1.3) | Fear | Staff, equipment | Staff shouting, machine noise, killing methods |

|

None |

| Too high temperature (3.6.1.13) | Heat stress | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, too early ventilation shutdown, long delay between sealing house and gas injection |

|

Increase ventilation |

| Too low temperature (3.6.1.14) | Cold stress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, CO2 injection without proper heating, injection on the birds, physical property of gas, too fast injection rate |

|

Optimise gas injection/flow rate |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear, respiratory distress | Staff | Premature evacuation of the gas, gas escaping the premise (inadequate sealing) |

|

Continue the process until all birds are dead, improve sealing |

| Too low gas concentration (3.6.1.15) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear, respiratory distress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, property of the gas, concentration of the gas, uneven distribution of the gas, method of injection, frozen equipment |

|

Add more gas or increase the exposure time to kill all birds |

| Jet stream of gas at bird level (3.6.1.16) | Pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operator, injection pipes located at bird level, lack of protection of the birds in front of injection pipes |

|

None |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, panting, shivering and (if prolonged) frozen animals, head shacking, escape attempt, wing flapping, injuries, bunching | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 13.

Outcome table on ‘whole house gassing with gas‐filled foam stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected loud noise (3.6.1.3) | Fear | Staff, equipment | Staff shouting, machine noise, killing methods |

|

None |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, fear, respiratory distress | Staff | Lack of skilled operators; too low foam capacity or foam production |

|

Continue foam production until all birds are dead |

| Too small bubble size (3.6.1.17) | Respiratory distress (suffocation), pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Inappropriate surfactant concentration, inappropriate gas supply |

|

Adjust the method to the correct settings (e.g. foam detergent concentration) |

| Low foam production rate (3.6.1.18) | Not dead, consciousness, fear | Staff, equipment | Too low capacity of equipment |

|

Increase foam production |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, wing flapping, escape attempts, vocalisations | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 14.

Outcome table on ‘gas mixtures in containers stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too low temperature (3.6.1.14) | Cold stress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, liquid delivery of gas, physical property of gas, too fast gas injection rate |

|

Optimise gas injection |

| Inhalation of high CO2 concentration (3.6.1.19) | Pain, fear, respiratory distress | Equipment | Due to the method, property of the gas | None | None |

| Overloading (3.6.1.20) | Pain, fear, respiratory distress | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, adding more than one layer of birds at one time or quick succession, introduction of a batch into container before previous batch of birds are dead |

|

Stop adding birds before the previous ones are dead |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, respiratory distress | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, lack of monitoring of the exposure time |

|

Adjust exposure time |

| Too low gas concentration (3.6.1.15) | Not dead, consciousness, respiratory distress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, lack of monitoring of the concentration, inadequate property of the gas, uneven distribution of the gas, incorrect method of injection, frozen equipment, weather (windy and temperature), inappropriate containers |

|

Add more gas or increase the exposure time to kill all birds |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, shivering, escape attempt, wing flapping, head shaking and injuries | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 15.

Outcome table on ‘low atmospheric pressure stunning/killing (LAPS)’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too fast decompression (3.6.1.21) | Pain, (respiratory) distress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, wrong rate of decompression |

|

None |

| Expansion of gases in the body cavity (3.6.1.22) | Pain | Equipment | Part of the method | None | None |

| Too short exposure time (3.6.1.10) | Not dead, consciousness, (respiratory) distress | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, too short duration of exposure considering the rate of decompression |

|

Adjust exposure time |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, escape attempts, wing flapping, hyperventilation | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 16.

Outcome table on ‘captive bolt stunning and killing’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | Presentation of birds to the method is required | None | None |

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Fear | Staff, equipment | Manual restraint with inversion or in a cone | Avoid the inversion of conscious animals | None |

| Incorrect shooting position (3.6.1.23) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, operator fatigue, poor presentation of birds |

|

Kill in the correct position |

| Incorrect captive bolt parameters (3.6.1.24) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operator, wrong choice of equipment, poor maintenance of the equipment, too narrow bolt diameter, shallow penetration, low bolt velocity |

|

None |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, wing flapping, vocalisations, attempt to regain posture | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 17.

Outcome table on ‘percussive blow’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | Presentation of birds to the method is required | None | None |

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Pain, fear | Staff | Manually inverting the birds for the application of the blow | Avoid the inversion of conscious animals | None |

| Incorrect application (3.6.1.25) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff | Lack of skilled operator, operator fatigue, poor restraint, hitting in wrong place, not sufficient force delivered to the head |

|

Correct application of the method |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, vocalisations, wing flapping | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Table 18.

Outcome table on ‘cervical dislocation’ ( a ): hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | Presentation of birds to the method is required | None | None |

| Inversion (3.6.1.4) | Pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Manually inverting the birds for the application of the method or restraint in a cone | Avoid the inversion of conscious animals | None |

| Incorrect application (3.6.1.25) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, fear | Staff, equipment | Lack of skilled operators, operator fatigue, equipment not suitable for size/species of birds, attempt to induce cervical dislocation by crushing of the neck rather than by stretching and twisting |

|

Use cervical dislocation by stretching and twisting |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, vocalisations, wing flapping | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Manual in birds up to 3 kg and mechanical in birds weighing from 3 to 5 kg.

Table 19.

Outcome table on killing with ‘maceration’ a: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), welfare consequences and relevant ABMs; hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slow rotation of blades or rollers (3.9.1) | Not dead, consciousness, pain | Staff, equipment | Lack of training, inappropriate setting |

|

None |

| Overloading (3.9.2) | Pain, distress, fear | Staff | Lack of training |

|

Stop loading chicks before the previous ones are dead, reduce the flow of chicks at the entrance to the machine |

| Rollers set too wide (3.9.3) | Not dead, consciousness, pain | Staff, equipment | Lack of training, inappropriate setting |

|

None |

| ABMs: signs of life, signs of consciousness, injuries, vocalisations | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

Applicable to day‐old chicks.

Table 20.

Outcome table on killing with ‘lethal injection’: hazards (with the No. of the section in which hazard's full description is provided), with relevant welfare consequences, ABMs, hazard's origin and preventive and corrective measures

| Hazard | Welfare consequence(s) occurring to the birds due to the hazard | Hazard origin(s) | Hazard origin specification | Preventive measure(s) of hazards (implementation of SOP) | Corrective measure(s) of the hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual restraint (3.6.1.5) | Pain, fear | Staff | Presentation of birds to the method is required | None | None |

| Inappropriate route of administration (3.6.1.26) | Not dead, consciousness, pain, distress | Staff | Lack of skilled operators, inappropriate restraint, selection of wrong route of administration |

|

Adjust injecting with right amount of drug using appropriate route |

| Sublethal dose (3.6.1.27) | Not dead, consciousness, fear, distress | Staff | Administration of wrong dose of drug |

|

Inject with right amount of drug |

| ABMs: Signs of life, signs of consciousness, vocalisations, wing flapping, attempt to regain posture | |||||

ABM: animal‐based measure; SOP: standard operating procedure.

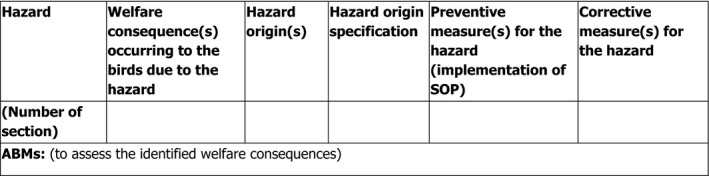

Description of the structure of the outcome tables

The outcome tables have the following structure and the following terminology should be referred to:

‘OUTCOME TABLE’: Each table represents the summarised information for the processes described in the assessment (see Sections 3.3 and 3.4).

Column ‘HAZARD’: in each table, the first column reports all hazards pertaining to the specific process related to on‐farm killing of poultry; the number of the section in which each hazard is described in detail is reported in brackets.

‘ROW’: For each hazard, the individual row represents the summarised information relevant to the aspects analysed for that hazard. Therefore, it links among an identified hazard, the relevant welfare consequences, origin(s) of hazards and preventive and corrective measures (see example in Figure 2).

Column ‘WELFARE CONSEQUENCES OCCURRING TO THE BIRDS DUE TO THE HAZARD’: in which the welfare consequences on the birds due to the mentioned hazards are listed.

Column ‘HAZARD ORIGIN’: this contains the information related to the main origins of the hazard; for on‐farm killing it can be staff or equipment related. Hazards can have more than one origin.

Column ‘HAZARD ORIGIN SPECIFICATION’: this further specifies the origin of the hazard. This information is needed to understand and choose among the available preventive and corrective measures.

Column ‘PREVENTIVE MEASURE(S) OF THE HAZARD’: depending on the origin(s) of the hazard, several measures are proposed to prevent the hazard. They are also aspects for implementing standard operating procedures (SOP).

Column ‘CORRECTIVE MEASURE(S) OF THE HAZARD’: practical actions/measures for correcting the identified hazards are proposed. These actions may relate to the identified origin of the hazards.

Row ‘ANIMAL‐BASED MEASURES’: list of the feasible measures to be performed on the birds to assess the welfare consequences of a hazard.

Figure 2.

Structure of outcome table (for details on the data, see Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20–20)

2.2.3. Uncertainty analysis

The outcome tables include qualitative information on the hazards and related aspects identified through the methodologies explained in Section 2.2.

When considering the outcome tables, uncertainty exists at two levels: (i) related to the completeness of the information presented in the table, namely to the number of rows within a table (i.e. hazard identification); and (ii) related to the information presented within a row of the table (i.e. completeness of hazard origins, preventive and corrective measures on the one side, and welfare consequences and ABMs on the other side).

However, owing to the limited time available to develop this Scientific Opinion, there will not be an uncertainty analysis for the latter level, but only for the first level, i.e. for the hazard identification.

In such a process of hazard identification, uncertainties may result in false‐negative or false‐positive hazard identifications:

Incompleteness (false negative): Some welfare‐related hazards may be missed in the identification process and so would be considered non‐existent or not relevant.

Misclassified (false positive): Some welfare‐related hazards may be wrongly included in the list of hazards of an outcome table without being a relevant hazard.

Incompleteness (false negatives) can lead to under‐estimation of the hazards with the potential to cause (negative) welfare consequences.

The uncertainty analysis was limited to the quantification of the probability of false‐negative or false‐positive hazards. False‐negative hazards can relate to: (i) the situation under assessment, i.e. limited to the on‐farm killing practices considered in this assessment according to the three criteria described in the Interpretation of ToRs (see Section 1.2); or (ii) the global situation i.e. including all possible variations to the on‐farm killing practices that are employed in the world, and that might be unknown to the experts of the WG. The Panel agreed it was relevant to distinguish the false‐negative hazard identification analysis for these two cases.

For false‐negative hazard identification, the experts elicited the probability that at least one hazard was missed in the outcome table. For false‐positive hazard identification, the experts elicited the probability that each hazard included in the outcome table was correctly included.

For the elicitation the experts used the approximate probability scale (see Table 1) proposed in the EFSA Uncertainty Guidance (EFSA, 2019). Individual answers were then discussed, and a consensus judgement was obtained.

Table 1.

| Probability term | Subjective probability range | Additional options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almost certain | 99–100% | More likely than not: >50% |

Unable to give any probability: range is 0–100% Report as ‘inconclusive’ cannot conclude, or ‘unknown’ |

| Extremely likely | 95–99% | ||

| Very likely | 90–95% | ||

| Likely | 66–90% | ||

| About as likely as not | 33–66% | ||

| Unlikely | 10–33% | ||

| Very unlikely | 5–10% | ||

| Extremely unlikely | 1–5% | ||

| Almost impossible | 0–1% | ||

A qualitative translation of the outcome of the uncertainty assessment was also derived (e.g. ‘extremely unlikely’ for an uncertainty of 1–5%: see Table 1).

3. Assessment

3.1. Introduction

Section 3.2 provides an overview of the practices that can be performed on‐farm in the context of killing of birds for purposes other than slaughter (on‐farm killing). The following sections (Sections 3.3 and 3.4) describe in detail the processes related to on‐farm killing, and are structured in two sections: (i) process description, with information on how they are technically and practically carried out and how the birds are kept (e.g. if still in containers or in a restraint device); and (ii) a section on hazards and welfare consequences in which, to explain the impact of each process on birds’ welfare, a list of the main hazards that can occur in the process and the relevant welfare consequences that the hazards can cause, is provided. In some specific cases ABMs are also provided as examples.

Section 3.5 deals with the unacceptability on welfare grounds of methods, procedures or practices.

The details of the hazard's characterisation and origins (ToR1) and the description of hazard's preventive and corrective measures (ToR3) are discussed in Section 3.6; the description of the welfare consequences, the related ABMs (ToR2) and of the measures to mitigate the welfare consequences is provided in Section 3.7. The preventive measures (ToR3) that are considered general and applicable to several hazards and processes are presented in Section 3.8. Specific hazards related to animal categories (i.e. day‐old chicks) (ToR4) are reported in Section 3.9.

Finally, outcome tables linking the above‐mentioned aspects requested by the ToRs of the mandate are reported in Section 3.10.

3.2. Description of on‐farm killing practices

3.2.1. Introduction

Killing of animals for purposes other than slaughter could be due to different reasons such as the culling of injured and sick individuals, needs associated with stock management, or emergency killing for disease control, management of natural disasters or other emergencies including those related to animal welfare. The methods used to cull small numbers of animals on farm are diverse and they may differ from those applied on a large scale, e.g. for depopulation.

According to the mandate, the current assessment should be focus on two scenarios: (1) large‐scale killing that takes place in case of depopulation for disease control purposes and for other similar situations; and (2) the killing of unproductive or surplus animals that might be practised on farm. This second scenario can be split in two categories: (i) large‐scale killing of unproductive animals; and (ii) individual killing of unproductive, unhealthy or injured birds.

3.2.2. Large‐scale killing

Large scale cannot simply be defined by setting a limit at a certain number of birds, as the concept should be viewed not only in terms of absolute numbers but also in relation to the total number of birds in the flock and at the farm. The assumption is that a group, a considerable proportion of the birds, are involved: not just a few individuals.

The expression ‘large‐scale killing’ is not used for small non‐commercial entities (backyard or hobby flocks), even in cases in which all birds in a flock are killed. In contrast to depopulation, large‐scale killing does not necessarily – but commonly does – involve the entire flock; the main difference relates to the context in relation to the reason for the killing. In relation to poultry, the expression ‘large scale’ is commonly not used for groups or flocks of less than approximately 500 birds, but this is not a fixed, pre‐defined number.

This practice takes place in case of depopulation18 for disease control purposes (Raj et al., 2006; Berg, 2009a; Gerritzen and Raj, 2009) and for other similar situations (environmental contamination, natural disaster management such as earthquake, floods, etc.; Raj, 2008; Thornber et al., 2014) outside slaughterhouses under the supervision of the competent authority. Large‐scale killing for disease control involves the killing of all birds in at least one given biosecurity‐based compartment, such as a poultry house, where a disease has been diagnosed or is suspected or the empty a zone if there are difficulties in controlling the disease. More often, and depending on the nature of the disease, it involves the killing of all birds at the premises involved, i.e. possibly in several compartments or houses at the same farm (Berg, 2009a) or at several farms in an area (with the aim of ‘stamping out’ the disease), for example if a case of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was detected (EFSA, 2004, 2008). Furthermore, the activity may involve pre‐emptive killing of poultry at adjacent farms and farms with known or suspected contact, direct or indirect, with the infected premises (Berg, 2012). In relation to a serious disease outbreak, various other restrictions may be imposed regionally, such as a stand‐still prohibiting live poultry transport and feed transports. Already within a few days, such restrictions may lead to poultry welfare problems related to overstocking or feed shortage, and birds may then have to be killed on‐farm to prevent further suffering (Raj, 2008; Berg, 2012). In emergencies other than disease outbreaks, these may be linked e.g. to various types of disasters such as flooding or wildfires, but also chemical environmental contamination or nuclear power plant accidents. In practice, it is rarely possible to evacuate the birds from large‐scale commercial poultry farms and, if producer and staff have to be evacuated for human health reasons, the birds may be left behind. In such cases, especially if evacuation is expected to be long‐lasting and the birds will run out of feed, water and be without supervision for an extended period of time, killing of the flocks is a preferred alternative from an animal welfare perspective. The same applies if the disaster itself will affect the birds in a way that will make their meat or eggs unsuitable for human consumption. In summary, depopulation can be defined as the process of killing animals for public health, animal health, animal welfare or environmental reasons and, in the EU, according to Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009, it should be carried out under the supervision of the competent authority. Depopulation is usually large scale when commercial flocks are involved, but can also be small scale, if the farm is small or for backyard flocks. Large‐scale killing and depopulation can be applied to any type of poultry of any age. It has been suggested that welfare of animals can be greatly improved if the facilities take into consideration, at the time of design and construction stages, the various needs for depopulation (Gavinelli et al., 2014).

3.2.3. Killing of unproductive or surplus animals

This practice can be split in subcategories (see also Table 2).

Table 2.

Stunning/killing methods used on‐farm and approved for poultry under Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 as described in this Scientific Opinion for depopulation and individual killing of animals, with indication of the purpose of killing (see Section 3.2)

| Method | Purpose of on‐farm killing | |

|---|---|---|

| Large‐scale killing | Individual killing | |

| Electrical | ||

| Waterbath | Yes | No |

| Head only | Yes | Yes |

| Head to body | Yes | Yes |

| Modified atmospheres | ||

| Whole house gassing | Yes | No |

| Whole house gassing with gas‐filled foam | Yes | No |

| Gas mixtures in containers | Yes | Yes |

| Low atmospheric pressure a | Yes | No |

| Mechanical | ||

| Captive bolt | Yes | Yes |

| Percussive blow to the head b | Yes | Yes |

| Cervical dislocation b | Yes | Yes |

| Maceration c | Yes | No |

| Lethal injection | Yes | Yes |

Low atmospheric pressure stunning/killing (LAPS) has not been evaluated.

Certain conditions apply to percussive blow to the head and cervical dislocation and these are presented under the relevant sections (Sections 3.4.4.2 and 3.4.4.4).

Maceration is permitted only for day‐old chicks (for details, see Section 3.4.4.3).

3.2.3.1. Large‐scale killing of unproductive animals

This practice relates, for example, to the killing of end‐of‐lay hens (Berg et al., 2014), surplus male broiler breeders or male day‐old layer chicks. The latter category includes male day‐old layer chicks or surplus male day‐old breeder chicks, when animals are hatched on the farm. Otherwise, it is performed in the hatchery itself.

For end‐of‐lay hens, slaughter is not always an option, depending on the geographical location of the farm in relation to the nearest available laying hen slaughterhouse, and on the costs and work involved in catching, crating, transporting and slaughtering birds with a very limited economic value. There are also egg producers that choose on‐farm killing of the end‐of‐lay hens for animal welfare reasons, to spare the birds the stress of being caught (depending on the method), crated and transported. Furthermore, there are cases in which the end‐of‐lay hens are deemed unfit for transport due to poor plumage condition, poor skeletal condition or are unlikely to be accepted for human consumption due to underlying infections and that may not be affecting the birds but are considered problematic for meat quality or consumer health (e.g. Salmonella contamination). If the meat from these birds is not acceptable for human consumption, the birds should not be sent to a slaughterhouse, but instead be killed on the farm. Large‐scale killing of unproductive birds at end of lay predominantly refers to end‐of‐lay hens after egg production, but can in some cases also involve end‐of‐lay breeding poultry of any species, for example, end‐of‐lay broiler breeders, laying hen breeders or turkey breeders, although these categories are more often sent for slaughter, when there is market demand.

A separate case relates to male broiler breeders during the production cycle, in which natural mating predominantly occurs and the proportion of males to females will usually be deliberately decreased with time. This means that healthy male birds will routinely be killed during the production cycle. It can be debated if the killing of surplus male broiler breeders during the production cycle is truly ‘large scale’ as it only involves a few per cent of the birds in a given shed, but as the birds are neither sick nor injured they may still be included in this category.

3.2.3.2. Individual killing

On any farm, individual birds may become sick or injured. This covers for example production‐related diseases, metabolic diseases, infectious diseases, health issues emanating from behavioural problems such as injurious pecking, or injuries caused by accidents. In commercial large‐scale poultry production, single or low numbers of sick or injured birds are often not attended by a veterinarian and not treated individually. Instead, they are killed to prevent further suffering, and to avoid the possible costs related to the keeping of low producing/non‐producing birds (Berg, 2009b). For animal welfare reasons, such birds should be killed and not left to die slowly while remaining in the flock. Hence, it is of utmost importance that the producer or staff routinely, preferably twice daily, inspect the flock to identify and kill such birds. The producer and stockpersons at a farm are responsible for ensuring that birds that are suffering from injury or disease, when treatment is not an option, are humanely killed. According to the EU Broiler Directive (2007/43/EC)19, broiler keepers are obliged to participate in specific training, including emergency killing and culling. Individual killing on‐farm can be applied to any type of poultry of any age.

It is hence important to differentiate between ‘on‐farm killing’ of poultry in general, which can be carried out for a number of different reasons as described above and relate to single or multiple birds or the entire flock (unproductive or surplus birds, disease control, disaster management, animal welfare reasons) and ‘emergency killing’. Emergency killing is always urgent, and it is related to single or multiple birds or the entire flock. The term ‘emergency killing’, as used in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009, means the killing of animals that are injured or have a disease associated with acute pain or suffering, and when there is no other practical possibility to alleviate this pain or suffering. In this case, the killing needs to be provoked immediately. In contrast, the term ‘depopulation’ is used for describing a planned process of killing animals for public health, animal health, animal welfare or environmental reasons under the supervision of the competent authority (as described in Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009), and should refers to the killing of an entire flock – or several flocks – at the same or adjacent premises of birds.

All the methods presented in Table 2 are applicable for emergency killing of individual birds. However, cartridge powered captive bolts are the most feasible option in this context, owing to the portability of equipment and ease of use, especially in large/heavy birds like broiler breeders, turkeys, ducks and geese. Manual or mechanical cervical dislocation by stretching, or percussive blow to the head can also be used if appropriate to the bird type. Electrical and controlled atmosphere stunning/killing methods are usually not used for emergency killing, for practical reasons (lack of equipment, need of skilled personnel, etc.).

Poultry are usually kept in large groups in closed, controlled housing systems. An important reason for killing poultry on‐farm is related to problems with the general fitness of individuals. In commercial flocks, single birds are rarely treated or placed in separate sick pens. Instead, birds that are not fit to follow the routines in the large flocks (sick or injured) are usually removed and killed. Birds that are not apparently sick but are growing considerably slower than the remaining flock (with poor growth rate, often referred to as runts) will also be culled. The reason for this is twofold: as feed and water lines are gradually elevated to fit the size of the birds, the runts may experience difficulties reaching these resources and so suffer from prolonged thirst and hunger and even die from it. Second, these very small birds are usually not accepted by the slaughterhouse, even if they survived the last journey, as the stunning and processing equipment does not fit these. Council Regulation (EC) No. 1099/2009 clearly states that birds that are likely to miss the waterbath stunners, which is the most common method used throughout the world, should not be shackled, but instead killed humanely, preferably on the farm before transport. In addition, birds that are not fit for transport (Council Regulation (EC) No. 1/2005020 should be killed humanely on the farm to avoid unnecessary suffering during transport.

Domestic birds are killed on the farm during production for several reasons, including economic ones. For example, newly hatched chicks derive nutrients from their yolk sacks for survival for the first few days of life (up to 72 h after hatching) and may not survive if they do not begin to eat and drink before this source is depleted. Broiler farmers therefore routinely monitor the flock and they recognise the chicks’ viability from their growth and activity patterns. Chicks showing signs of poor health or welfare or viability are usually killed, this is commonly known as ‘culling’ and this is a continuous operation throughout the production cycle in a flock.

Poultry are killed regularly for various reasons that lead to poor welfare, most notably, those severely injured due to feather pecking or cannibalism, which is most commonly seen in laying hens. Also, in turkeys, including breeding stock, injurious pecking can be a reason for on‐farm killing. In any type of poultry, severe injuries caused by other birds or by interactions with equipment are a cause for killing to avoid further suffering. The same applies to obviously sick or moribund poultry of any type, regardless of the underlying cause or signs, as a clear diagnosis is often not made.

One major reason for killing broilers on farm is associated with leg disorders. Leg disorders may begin to develop in the flock as early as 14 days of age and worsen very rapidly during 25–45 days of age. It is a common practice in the industry to kill broilers showing signs of severe lameness, i.e. birds being unable to walk or having great difficulties in walking or sustained standing, due to the fact that these birds will be suffering severe pain and they would, as a result of their increasing immobility, be deprived of access to feed and water (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2012b).

3.3. Handling of the birds

3.3.1. General principles

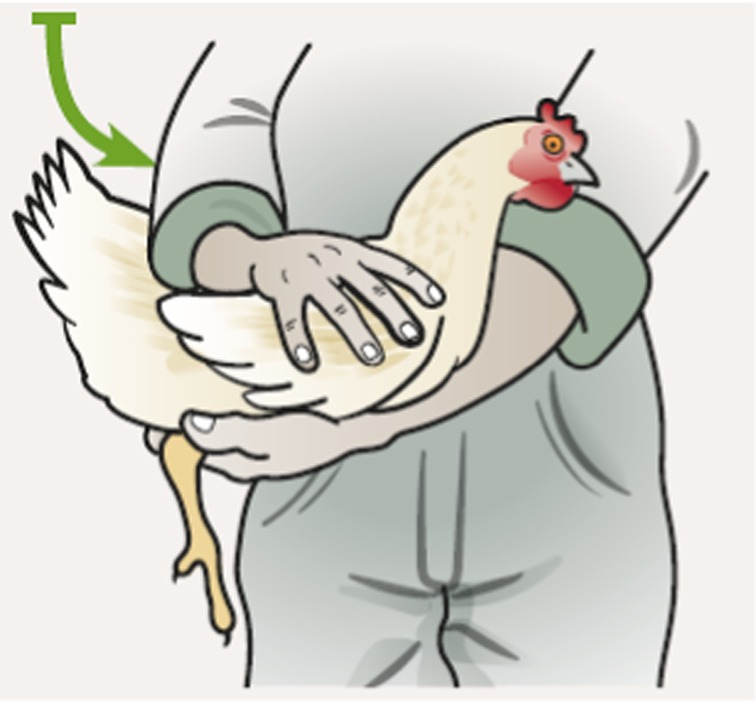

Although domestication and subsequent genetic selection of poultry have reduced the magnitude of their fear responses, poultry still perceive humans as predators (Gerritzen and Raj, 2009). Response to handling may vary between flocks and farms based on the animal species, the rearing system and the amount and nature of previous interactions with stockpersons.

Housing systems used to rear domestic birds vary widely according to the species (e.g. broiler vs layer hens) stage of production (e.g. chick brooder vs pullets and broilers on deep litter vs laying hens in barns or cages), size of the farming operation (number of birds at each stage) and the farming/housing system (e.g. indoor vs free range) and country/geographical location in the world. It is therefore inevitable that the nature of hazards and the magnitude of animal welfare consequences would vary according to these factors during the life of the birds and when handled for any purpose, including killing.

In addition, the method of killing to be employed will also determine the nature of hazards and the number of birds exposed to these.

3.3.2. Process description

Handling consists in removing birds from their rearing environment; depending of the housing systems and the method of killing, the scenarios that it could occur are:

Absence of bird handling and minimum movement (e.g. in the cases of whole house gassing).

-

Manual handling:

-

‐

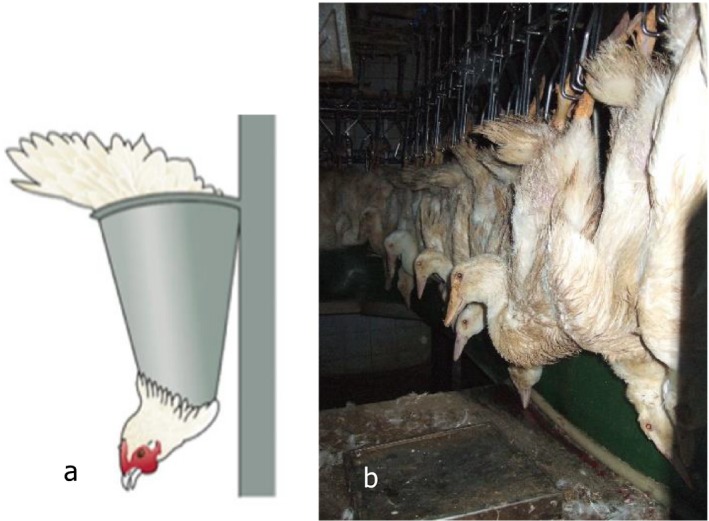

e.g. for electrical waterbath or gassing in containers, birds are manually caught by their legs, inverted and carried up to three birds in each hand of the operator to the point of killing on distances that can be long;

-

‐

e.g. for containerised gassing, birds are caught by their legs, inverted and placed rapidly in containers and moved in containers to the point of killing either inside or outside the building.

-

‐

Movement of birds may involve passing these from operator to operator several times, each acting as trigger for wing flapping. For example, the catcher would pass the birds to the carrier who would pass these on to the loader to put these into containers (Tinker et al., 2004). When birds are killed outside the house, operators catching birds inside the house may hand these over to a different operator to carry these to the point of killing or hand these over to operators performing restraint of individual birds (e.g. shackling or placing inverted in cones).

Lighting intensity during rearing, breed and strain of birds, age at sexual maturity, age at depopulation, weight and catching method might impact bird reactivity and affect welfare outcomes (EFSA, 2004).

Among all domestic birds considered in this Opinion, laying hens are the most vulnerable to suffer injuries due to reduced bone strength related to osteoporosis in end of lay (Gregory and Wilkins, 1989).

Diverse types of containers are used for moving birds and hazards may vary according accordingly. When housed in cages, the type of cage can influence handling conditions and laying hens welfare:

Battery cages are widely used outside the EU for layer hens and they are arranged in tiered rows along the length of the house with passageways between these. Up to six hens may be kept in each cage and removing these through a narrow cage opening and carrying inverted birds, up to three in each hand, along the narrow passageways impose high welfare risks (Tinker et al., 2004), especially broken bones (Gregory et al., 1993).

Enriched cages are now compulsory in the EU, but the design and layout of facilities (presence of nest boxes and perches) and colony size (up to 60–80 birds) are significant factors to be considered during catching and handling. There are at least two types of cage‐free systems used for layer hens: those with flat floor and those with up to four tiers of perches (known as aviaries). Some design and layout of perches may affect the practicability of catching and handling the birds (Gregory et al., 1990; Knowles and Wilkins, 1998; Leyendecker et al., 2005).