Abstract

The EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLHP) performed a pest categorisation of Saperda tridentata (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) for the EU. S. tridentata (elm borer) occurs in eastern North America. Ulmus americana and U. rubra are almost exclusively reported as hosts, apart from two 19th century records from the USA of larvae from Acer sp. and Populus sp. The Panel does not exclude the possibility of a post‐entry shift in host range to European Ulmus or Acer and Populus. S. tridentata infests trees that are already weakened, and severe infestations can result in tree death. S. tridentata occurs across a range of climate types in North America that occur also in Europe. Between 2016 and 2019, S. tridentata larvae were intercepted with North American Ulmus logs imported into the EU. In the EU, American Ulmus species are mainly found in arboreta and as ornamental specimen trees. If only North American Ulmus are hosts, establishment is unlikely. However, if European Ulmus, Populus or Acer species become hosts, establishment is much more likely, with impact confined to already weakened trees. The information currently available on geographical distribution, biology, impact and potential entry pathways of S. tridentata has been evaluated against the criteria for it to qualify as potential Union quarantine pest or as Union regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP). Since the pest is not reported in EU, it does not meet the criteria assessed by EFSA to qualify as potential Union RNQP. S. tridentata satisfies the criterion for quarantine pest regarding entry into the EU territory. Due to the scarcity of data, the Panel is unable to conclude if S. tridentata meets the post‐entry criteria of establishment, spread and potential impact.

Keywords: Elm borer, longhorn beetle, pest risk, plant health, plant pest, quarantine, host range uncertainty

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

Council Directive 2000/29/EC1 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community establishes the present European Union plant health regime. The Directive lays down the phytosanitary provisions and the control checks to be carried out at the place of origin on plants and plant products destined for the Union or to be moved within the Union. In the Directive's 2000/29/EC annexes, the list of harmful organisms (pests) whose introduction into or spread within the Union is prohibited, is detailed together with specific requirements for import or internal movement.

Following the evaluation of the plant health regime, the new basic plant health law, Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants, was adopted on 26 October 2016 and will apply from 14 December 2019 onwards, repealing Directive 2000/29/EC. In line with the principles of the above mentioned legislation and the follow‐up work of the secondary legislation for the listing of EU regulated pests, EFSA is requested to provide pest categorisations of the harmful organisms included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC, in the cases where recent pest risk assessment/pest categorisation is not available.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, to provide a scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to prepare and deliver a pest risk assessment (step 1 and step 2 analysis) for Saperda tridentata. The opinion should address all entry pathways, spread, establishment and risk reduction options. As explained in the background, please pay particular attention to the pathway of wood of Ulmus.

1.1.2.1. Background

The new Plant Health Regulation (EU) 2016/2031, on the protective measures against pests of plants, will be applying from 14 December 2019. Provisions within the above Regulation are in place for the listing of “high risk plants, plant products and other objects” (Article 42) on the basis of a preliminary assessment, and to be followed by a risk assessment. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2019 is establishing a provisional list of high risk plants, plant products or other objects, within the meaning of Article 42 of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031. The import of commodities included in the above mentioned list will be banned from 14 December 2019, awaiting the outcome of a risk assessment. Wood of Ulmus L. originating from third countries or areas of third countries where S. tridentata is known to occur, is included in this list and its introduction into the Union shall be provisionally prohibited.

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is to prepare and deliver a two‐step pest risk assessment for S. tridentata Olivier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). The first step will be to subject S. tridentata to the process of pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria, which are within the remit for EFSA to assess, for it to be regarded as a quarantine pest or of a regulated non‐quarantine pest for the area of the European Union (EU) excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores. The second step will require EFSA to conduct a more detailed assessment of all entry pathways, spread, establishment and risk reduction options. Particular attention will be given to the pathway of wood of Ulmus.

The new Plant Health Regulation (EU) 2016/2031,2 on the protective measures against pests of plants, will be applying from December 2019. The regulatory status sections (Section 3.3) of the present opinion are still based on Council Directive 2000/29/EC, as the document was adopted in November 2019.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Literature search

A comprehensive literature search on S. tridentata was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name and synonyms (Chapter 3.1.1) of the pest as search term. Relevant papers were reviewed, and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

Because of uncertainty around host plants, additional searches in the Biodiversity Heritage Library database (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/), and the JSTOR database (https://www.jstor.org/), were conducted using the scientific name of the pest and synonyms as a search term (more information in Appendix D).

2.1.2. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online) and relevant publications.

Data for the estimation of the import of elm wood were obtained from https://www.americanhardwood.org/ and Eurostats.

Data about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from the European Atlas of Forest Tree Species (https://forest.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en/european-atlas/atlas-download-page/).

The Europhyt database was consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission and is a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. The Europhyt database manages notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the Member States (MS) and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread.

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for S. tridentata, following guiding principles and steps presented in the EFSA guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) and in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures No 11 (FAO, 2014) and No 21 (FAO, 2004).

This work was initiated following an evaluation of potential high risk commodities to determine whether S. tridentata satisfied the criteria for it to qualify as a potential Union quarantine pest or a potential Union regulated non‐quarantine pest in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants, and includes additional information required in accordance with the specific terms of reference received by the European Commission. In addition, for each conclusion, the Panel provides a short description of its associated uncertainty.

Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. All relevant criteria have to be met for the pest to potentially qualify either as a potential quarantine pest or as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest. If one of the criteria is not met, the pest will not qualify. A pest that does not qualify as a quarantine pest may still qualify as a regulated non‐quarantine pest that needs to be addressed in the opinion.

Table 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest |

|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU? Describe the pest distribution briefly! |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a regulated non‐quarantine pest. (A regulated non‐quarantine pest must be present in the risk assessment area). |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3 ) | If the pest is present in the EU but not widely distributed in the risk assessment area, it should be under official control or expected to be under official control in the near future | Is the pest regulated as a quarantine pest? If currently regulated as a quarantine pest, are there grounds to consider its status could be revoked? |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways! |

Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects? Clearly state if plants for planting is the main pathway! |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? | Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated? | Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4 ) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met |

It should be noted that the Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, the Panel will present a summary of the observed pest impacts. Economic impacts are expressed in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms; addressing social impacts is outside the remit of the Panel (Table 1).

3. Pest categorisation

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

3.1.1.1.

Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? (Yes or No)

Yes, S. tridentata is established as a recognised species.

S. tridentata Olivier, 1795 is a coleopteran in the family Cerambycidae. Synonyms include Eutetrapha tridentata (Olivier, 1795), Compsidea tridentata (Olivier, 1795) and Saperda dubiosa (Haldeman, 1847). In North America, S. tridentata is known as the elm borer (Bosik, 1997) or the elm tree borer.

The genus Saperda Fabricius, 1775, consists of around 42 species. Felt and Joutel (1904) reported 16 species from North America, but Bezark (2016) revised the genus and suggests that there are 15 species of Saperda in North America.

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

Much of the literature on the biology of S. tridentata was published in the late 19th century, when S. tridentata was first recognised as a pest of American elms, and during the first half of the 20th century when it was thought to vector Ophiostoma ulmi, a causal agent of Dutch elm disease. The disease arrived in North America in the 1930s but was primarily spread by the native elm bark beetle, Hylurgopinus rufipes. Dutch elm disease killed millions of American elm trees and they are no longer a prominent feature in natural or urban landscapes (Allen and Humble, 2002). Consequent to the great loss of elms, and decrease in the supply for elm wood, almost no studies have been conducted on S. tridentata in recent decades. Much of the recent literature that mentions S. tridentata are simply records of its spatial expansion, e.g. westwards into Saskatchewan (Heffern, 1998; Bousquet et al., 2013), Colorado (Heffern, 1998) and Idaho (Rice et al., 2017). The following is therefore taken mainly from older literature describing the natural history of the species rather than from papers reporting experimental studies.

Oviposition takes place at night. Females chew a slit in the bark of branches of hosts or on logs of U. americana, U. rubra or U. crassifolia in which a single egg is oviposited. A female can chew slits quite close together (Pechuman, 1940; Drooz, 1985; Campbell et al., 1989). Females living for a month or so can lay 50–60 eggs (Pechuman, 1940). Branches that have recently died or are weakened, stressed or are otherwise low in vitality are preferred for oviposition (Baker, 1941). Host trees that have been recently felled are also favoured (Craighead, 1923). Tucker (1907) found no evidence that S. tridentata attacked healthy trees. Pechuman (1940) also suggested that healthy trees are not attacked.

Eggs hatch after a few days and larvae chew through the bark into the sapwood (Perkins, 1890). Unlike many other cerambycid species, larvae of S. tridentata do not burrow deeply but tend to remain between the sapwood and bark. As larvae grow, the tunnels they create meander in all directions within the sapwood and inner bark. There are at least three larval instars (Perkins, 1890). Feeding loosens the bark which can be peeled away easily (Perkins, 1890; Pechuman, 1940). When abundant, tunnels can girdle branches and the host's trunk (Hoffmann, 1942). Once established in a damaged or weakened branch of a host, larvae can move to healthy areas (Pechuman, 1940) although Baker (1941) reported that only occasionally were larvae found in live branches.

Larvae overwinter under the bark and in sapwood. In the spring, they bore a small distance into sapwood to form a chamber 5–6 mm into the wood. Here they develop into pupae. However, in unfavourable conditions, some remain as larvae for another year before pupae are formed the following spring.

After eclosure adults can remain in the pupal chamber for up to 7 days. They eventually exit either via the larval tunnel leading into the chamber or gnaw a new tunnel through the wood, leaving via roundish exit holes (Pechuman, 1940). Adults emerge in late spring and early summer (Campbell et al., 1989). Adults emerging in May develop from pupae that take on average 24–27 days to develop whereas adults emerging in June develop from pupae that develop in 15–18 days (Pechuman, 1940). Males emerge first. Adults feed on the mid‐rib and larger veins of host leaves, the surrounding leaf material, leaf petiole and the bark of young twigs (Craighead, 1923; Pechuman, 1940; Drooz, 1985). Adults can mate after 3 or 4 days of maturation feeding (Pechuman, 1940). Adults can fly and are most active at night; both males and females can be caught by light traps from May to August (Solomon et al., 1972; Gosling and Gosling, 1977). During the day adults shelter amongst foliage or bark (Pechuman, 1940). Adults live for 1 or 2 months.

There is usually one generation per year, but larvae hatching from eggs laid later in the summer e.g. during late July and August usually require an additional year to develop (Pechuman, 1940). When conditions are unfavourable for larval development, it may also take 2 years to complete development (Campbell et al., 1989). In wood that is dried out development may take 2 or 3 years (Pechuman, 1940).

3.1.2.1. Intraspecific diversity

Bousquet et al. (2013) list four subspecies of S. tridentata. However, no biologically relevant information could be found to justify considering them separately within this pest categorisation. The four are S. tridentata dubiosa Haldeman, 1847, S. tridentata rubronotata Fitch, 1858, S. tridentata intermedia Fitch, 1858 and S. tridentata trifasciata Casey, 1913.

3.1.3. Detection and identification of the pest

3.1.3.1.

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, light traps can capture adults. Juvenile stages can be detected by visual inspections. Traditional morphological keys are available to identify larvae and adults to species.

Detection

As a species that spends the majority of its life within its host, S. tridentata is not easy to detect until the host shows symptoms. Symptoms of S. tridentata larval infestation include the premature yellowing of leaves by a month or so (Tucker, 1907), thinning foliage, a few high branches dying before the rest of the crown, frass and sawdust on branches. When heavily infested, bark becomes loosened and can easily be peeled back to reveal larval tunnels. The inner bark can be heavily mined (Felt and Joutel, 1904). Careful inspection of trees can reveal roundish emergence holes 4–4.5 mm in diameter. Large holes in leaf tissue surrounding the larger veins and young twigs dangling by a strip of bark as a result of being chewed by adults (Pechuman, 1940) could indicate adults infesting an elm.

Identification

Traditional morphological keys can be used to identify adults and larvae. Craighead (1923) provides a species key to larvae in the genus Saperda. Packard (1890) provides a detailed description of the larvae. Craighead (1923) provides a description of the pupae. Felt and Joutel (1904) describe the adult. An image of the adult is provided in Drooz (1985).

Mature larvae are whitish legless and rather flattened, 12–25 mm long (Drooz, 1985; Solomon, 1995). Adults are 9–17 mm long; males have antennae almost as long as their body, the antennae of females are shorter. The body is grey with three orange‐yellow oblique bands on the elytra. There are twin black spots on each side of the pronotum and at the base of the elytra (Solomon, 1995).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

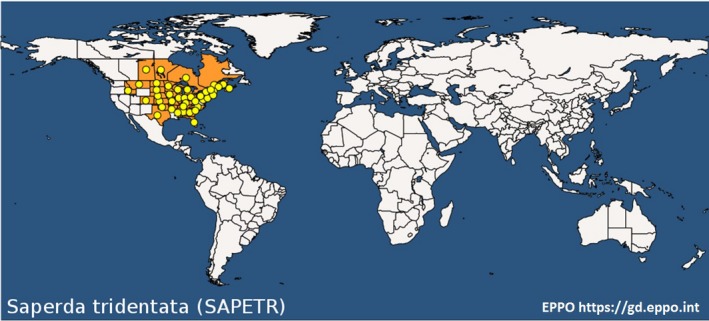

The genus Saperda occurs in temperate parts of the northern hemisphere (Felt and Joutel, 1904). S. tridentata is common in deciduous forests of eastern North America although it has been found as far west as Idaho (Rice et al., 2017). S. tridentata is not known to have spread outside North America. Figure 1 shows the known global distribution of S. tridentata.

Figure 1.

Global distribution of S. tridentata (last updated 7 November 2019). Extracted from the EPPO Global Database

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

3.2.2.1.

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU?

No. S. tridentata is not known to be present in the EU.

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Council Directive 2000/29/EC

S. tridentata is not listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC.

3.3.2. Legislation addressing the hosts of Saperda tridentata

The hosts range of S. tridentata is very uncertain (see Section 3.4.1). As a precaution, all legislation related to Ulmus species was included. Ulmus L. species comprise the major reported hosts of S. tridentata. Wood, cut branches and isolated bark of Ulmus davidiana Planch are controlled within Directive 2000/29/EC. Legislation relating to the genus Ulmus concerns the control of Agrilus planipennis (Annex IV A1, point 2.3, 2.4, 2.5), Stegophora ulmea, a pest listed in Annex II A I of the plant health directive 2000/29/EC, and Candidatus Phytoplasma ulmi (an Annex I A II pest). Tables 2 and 3 provide details of requirements pertaining to plants of Ulmus and Candidatus Phytoplasma ulmi).

Table 2.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve S. tridentata in Annex IV of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

|

Annex IV Part A |

Special requirements which must be laid down by all Member States for the introduction and movement of plants, plant products and other objects into and within all member states | |

| Section I | Plants, plant products and other objects originating outside the community | |

| Plants, plant products and other objects | Special requirements | |

| 2.3 | Whether or not listed among CN codes in Annex V, Part B, wood of […], Ulmus davidiana Planch. […] including wood which has not kept its natural round surface, and furniture and other objects made of untreated wood, originating in Canada, […] and USA |

Official statement that: (a) the wood originates in an area recognised as being free from Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire […], or (b) the bark and at least 2.5 cm of the outer sapwood are removed in a facility authorised and supervised by the national plant protection organisation, or (c) the wood has undergone ionizing irradiation to achieve a minimum absorbed dose of 1 kGy throughout the wood. |

| 2.4 | Whether or not listed among CN codes in Annex V, Part B, wood in the form of chips, particles, sawdust, shavings, wood waste and scrap obtained in whole or in part from […], Ulmus davidiana Planch. […] originating in Canada, […] USA | Official statement that the wood originates in an area recognised as being free from Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire […]. |

| 2.5 | Whether or not listed among CN codes in Annex V, Part B, isolated bark and objects made of bark of […] Ulmus davidiana Planch. […] originating in Canada, […] and USA | Official statement that the bark originates in an area recognised as being free from Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire […] |

| 14. | Plants of Ulmus L., intended for planting, other than seeds, originating in North American countries | Without prejudice to the provisions applicable to the plants in Annex IV (A)(I)(11.4), official statement that no symptoms of Candidatus Phytoplasma ulmi have been observed at the place of production or in its immediate vicinity since the beginning of the last complete cycle of vegetation. |

Table 3.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve S. tridentata in Annex V of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex V | Plants, plant products and other objects which must be subject to a plant health inspection ([…] — in the country of origin or the consignor country, if originating outside the Community) before being permitted to enter the community | |

| PART B | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in territories, other than those territories referred to in Part A | |

| Section 1 | Plants, plant products and other objects which are potential carriers of harmful organisms of relevance for the entire Community | |

| 6. (b) | Wood within the meaning of the first subparagraph of Article 2(2), where it meets one of the following descriptions laid down in Annex I, Part two to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2658/87: | |

| CN Code | Description | |

| ex 4403 99 | Non‐coniferous wood (other than tropical wood specified in subheading note 1 to Chapter 44 or other tropical wood, oak (Quercus spp.), beech (Fagus spp.) or birch (Betula L.)), in the rough, whether or not stripped of bark or sapwood, or roughly squared, not treated with paint, stains, creosote or other preservatives | |

| ex 4407 99 | Non‐coniferous wood (other than tropical wood specified in subheading note 1 to Chapter 44 or other tropical wood, oak (Quercus spp.), beech (Fagus spp.), maple (Acer spp.), cherry (Prunus spp.) or ash (Fraxinus spp.)), sawn or chipped lengthwise, sliced or peeled, whether or not planed, sanded or end‐jointed, of a thickness exceeding 6 mm | |

Commission Implementing Decision (UE) 2015/893 targeting Anoplophora glabripennis contains requirements to inspect plants and wood of A. glabripennis hosts which include Ulmus sp.

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Host range

Felt and Joutel (1904) report that S. tridentata feeds almost exclusively on white elm (Ulmus americana) although they recognise that red elm (U. rubra) can also be attacked. Solomon (1995) states that cedar elm (U. crassifolia) is also a host. MacRae (1993) reported finding adults of S. tridentata on Ulmus alata (winged elm, native to south central and south east USA). Whether or not U. alata is a host suitable for breeding is unknown.

The literature does not report species of European elm introduced into North America as hosts of S. tridentata (Table 4). Felt and Joutel (1904) state that there is no evidence that S. tridentata attacks European elms, U. glabra or U. minor. Campbell et al. (1989) cite Metcalf et al. (1951) when reporting that S. tridentata does not attack English elm (U. minor) or wych elm (U. glabra) two of the three most common elm species in Europe (Caudullo and de Rigo, 2016). The Swedish Unit for Risk Assessment of Plant Pests (Boberg and Björklund, 2018) drafted a short document citing Krischik and Davidson (2013) which reports ‘American elms, slippery elm and other elms’ as host plants. However ‘other elms’ are not identified and it is assumed that Krischik and Davidson (2013) were referring to North American species (listed as the first four in Table 4). No evidence was found that S. tridentata attacks the third European elm species (U. laevis). Hence, S. tridentata literature does not regard European Ulmus species as hosts. However, the literature is based on observational evidence. There have been no formal experiments, such as feeding choice studies, or oviposition choice experiments to categorically confirm that S. tridentata could, or particularly could not, develop on European elms.

Table 4.

Binomial and common names of key elm species referred to within this pest categorisation and notes related to their occurrence in Europe

| Ulmus species | Common name | Host statusa | Notes in relation to occurrence in Europe |

|---|---|---|---|

| U. americana |

American elm white elm water elm |

Major | This species has been introduced in Europe but does not grow well as it is more susceptible to insect foliage damage than native European elms and is susceptible to Dutch elm disease. It grows in European arboreta (Source: Botanic Gardens Conservation International database ‐ https://tools.bgci.org/global_tree_search.php), could be present in private gardens and parks as it is sold in horticultural trade. Abundance and density uncertain |

| U. crassifolia |

cedar elm Texas cedar elm |

Minor | Grows in European garden arboreta (Source: Botanic Gardens Conservation International database – https://tools.bgci.org/global_tree_search.php) |

| U. rubra |

slippery elm red elm |

Minor | Introduced to Europe in 1830 (White and Moore, 2003) |

| U. alata | Winged elm | Uncertain; minor host if a host at all | One of three American elm species known to be cultivated in UK as an ornamental in the early 1800s (Main, 1839), now rare. Could be present in private gardens and parks as it is sold in horticultural trade also as a bonsai. Abundance and density uncertain |

| U. glabra |

mountain elm wych elm Scots elm Scotch elm |

No evidence of being a host |

Wide range across most of Europe, from UK to Siberia, including Turkey. Previously widely planted as an ornamental in urban parks and along roadsides but no longer used as such due to its susceptibility to Dutch elm disease. |

| U. minor |

field elm smooth‐leaved English elm (in US?) |

No evidence of being a host |

Mainly in southern European regions by banks of small streams |

| U. laevis |

European white elm Russian elm |

No evidence of being a host |

Occurs across Central and Eastern Europe and is relatively rare. |

Major = most common host reported in literature. Minor = very few references in the literature.

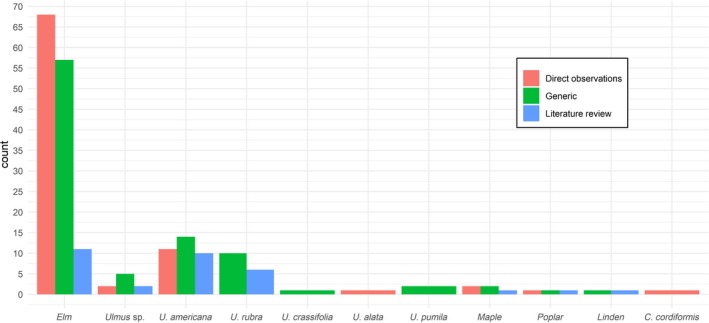

Figure 2 illustrates the number of pieces of literature that name plants as hosts of S. tridentata. Out of 304 references about S. tridentata, 183 refer to association with a named host. 94% of these associations were with Ulmus sp. (elm, Ulmus and four American species). Two generic reports refer to Siberian elm (U. pumila) introduced into North America.

Figure 2.

Number of pieces of literature that name plants as hosts of S. tridentata. Red: Count of literature with direct observations (e.g. documents reporting S. tridentata and its host(s) in open field or under laboratory conditions); Green: literature with generic observations (e.g. manuals and textbooks without supporting references); Blue: literature reviews. Names are quoted as found in the reference (Appendix D). Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library database (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/), the JSTOR database (https://www.jstor.org/), ISI Web of Knowledge. Last access to databases: 21 October 2019

However, five other broad‐leafed tree groups were mentioned in association with the pest, i.e. maple (Acer sp., n = 2), poplar (Populus sp., n = 1), linden (Tilia sp., n = 1) and bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis, n = 1) which require particular attention.

Maple: A repeatedly cited observation originally by Harrington (1883) described that he was ”…stripping the bark from a large prostrate maple on May 22nd,… The tree yielded… some pupae of Saperda tridentata, Oliv., from which imagos emerged on June 15th’’. Felt and Joutel (1904) noted (without further reference) that there is a record of S. tridentata emerging from maple (i.e. Acer). They write that the ‘infestation must have been abnormal or else the record was founded on an erroneous observation’. Ehrmann (1897) mentions that on ‘June 3. S. tridentata is found in numbers on the Elm and Acer’ without further description e.g. of distance between the elm and maple specimens, or S. tridentata phenological stage (adults or larvae). Hence, the observation by Ehrmann does not constitute a reliable record that Acer is a host on which S. tridentata development takes place.

Poplar (Populus): The only reference is by Washburn (1910) who annexed the following sentence to a chapter on S. tridentata on elm: ‘We have reared this same borer, S. tridentata, from Poplars.’ Details about the wood offered, the rearing conditions and the successful development of imagos are lacking.

Linden (Tilia): Lugger (1899) recognised that ‘S. vestida Say (linden borer), S. tridentata Oliv., and S. lateralis Fab., occur upon a variety of forest trees, such as linden, poplar and others’. Unfortunately, it remains ambiguous which borer referred to which tree, and whether by ‘others’ he referred to elm.

Hickory (Carya cordiformis): The report of Park (1931) regarding relations of Coleopterans to plants for food and shelter mentions for a mesophytic oak–elm–hickory subclimax that ‘Saperda tridentata Oliv. has been beaten from the foliage of the bitter‐nut hickory in numbers on July I7, and this is in the seasonal range for the species as given by Blatchley (1910, p. 1087). It has been repeatedly beaten from elm foliage. The larvae bore into this tree (Felt 1906, I, pp. 67‐70)’. Recall that during the day adults shelter amongst foliage or bark (Pechuman, 1940). Hence, the observation by Park (1931) does not constitute a reliable record that hickory is a host on which S. tridentata development takes place.

The potential of S. tridentata to change host selection preference given host limitation was not reported in literature. Therefore, host range in other species of the genus Saperda was addressed for American and non‐American species. The reported hosts of the other 14 North American Saperda species were compiled into a table (Appendix B). Half of the 14 species are reported to feed on hosts in more than one family. Of the seven remaining species at least five feed on hosts from two or more host genera. Two of the 14 species are recorded as having a single genus as a host. Appendix C lists 22 Saperda species from outside North America and records the host plants where known. Most feed on multiple genera. Three species, S. octomaculata, S. scalaris and S. subobliterara, feed on Ulmus. In Asia, S. octomaculata and S. scalaris are reported as feeding on Ulmus and other unspecified deciduous trees. S. subobliterata is an Asian species only recorded feeding on Ulmus japonica and U. laciniata (Appendix C). Examining the hosts of other Saperda species, four out of five species feeding on Ulmus have hosts in other Families too.

3.4.2. Entry

3.4.2.1.

Is the pest able to enter the EU territory? (Yes or No) If yes, identify and list the pathways.

Yes, wood is a pathway, S. tridentata has been intercepted in the EU with U. rubra wood from USA on seven occasions since records began being centrally collected via Europhyt in 1995.

3.4.2.2. Interceptions

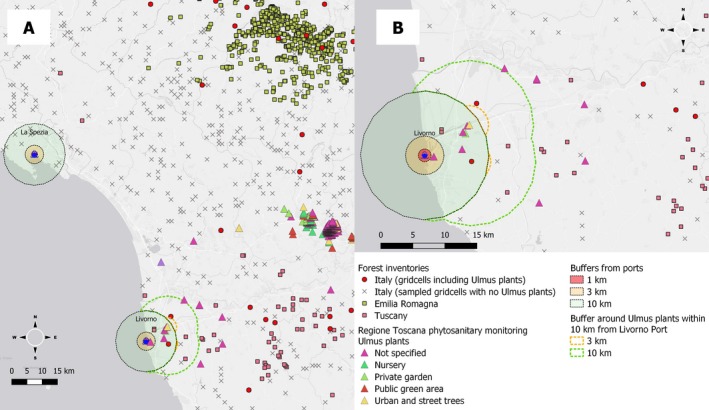

EUROPHYT data indicate that between 1995 and June 2019, there were six interceptions of S. tridentata (once in 2016, three times in 2017, once in 2018 and once in 2019) and one interception of Saperda sp. All were intercepted in Italy associated with U. rubra wood and bark from states close to the Great Lakes in USA (Ohio, Illinois, Iowa).

Prior to this pest categorisation, a 2016 interception report in EUROPHYT reported S. tridentata with a consignment of Ulmus rubra and of Juglans nigra roundwood (logs with bark) which led to J. nigra being referenced as a possible host in subsequent literature. A personal communication with the plant protection officer who conducted the original inspection has clarified that the larvae of S. tridentata were only found in U. rubra logs. The report in EUROPHYT has been clarified to prevent future misinterpretation. Consequently, the PLH Panel does not consider J. nigra as host of S. tridentata

Two records of Saperda sp. interceptions where no species is provided relate to interceptions of pallets and wood packing material from China to Germany. S. tridentata is not known to occur in China. We assume these interceptions were not S. tridentata but Asian Saperda species.

3.4.2.3. Pathways

S. tridentata could potentially enter the EU within different commodities comprising plant material including wood products (Table 5).

Table 5.

Traded wood and wood products that might comprise elm timber. Suggested pathways are listed with legislative measures which may result in S. tridentata detection during inspections required for other sanitary reasons

| CN Codea | Description | Regulatory measures |

|---|---|---|

| Solid wood packaging material (SWPM) if constructed using recently felled host timber | Managed by ISPM 15 (need to treat wood materials of a thickness greater than 6 mm, used to ship products between countries) | |

| ex 0602 | Plants for planting, other than seeds, in vitro material and naturally or artificially dwarfed woody plants for planting, originating from all third countries |

Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019. Ulmus plants for planting from North America are inspected […](2000/29 EC, Annex IV A I 14.). |

| 4401 12 00 | Fuel wood, in logs, in billets, in twigs, in faggots or in similar forms. Non‐coniferous | Requires inspection (Annex V B) |

| ex 4401 22 00 | Wood in chips or particles. Non‐coniferous | Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019 |

| ex 4401 39 00 | Sawdust and wood waste and scrap, agglomerated in logs, briquettes, pellets or similar forms. Others. | Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019 |

| ex 4403 12 00 | Wood in the rough, whether or not stripped of bark or sapwood, or roughly squared. Treated with paint, stains, creosote or other preservatives. Non‐coniferous | Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019 |

| ex 4403 99 00 | Wood in the rough, whether or not stripped of bark or sapwood, or roughly squared. Others. |

Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019. Requires inspection (See 2000/29 EC Annex V B Section I 6 b). |

| 4404 20 00 | Hoopwood; split poles; piles, pickets and stakes of wood, pointed but not sawn lengthwise; wooden sticks, roughly trimmed but not turned, bent or otherwise worked, suitable for the manufacture of walking sticks, umbrellas, tool handles or the like; chipwood and the like. Non‐coniferous | Requires inspection (Annex V B) |

| 4406 12 00 | Railway or tramway sleeps (cross‐ties) of wood. Not impregnated. Non‐coniferous | Requires inspection (Annex V B) |

| ex 4407 99 | Wood sawn or chipped lengthwise, sliced or peeled, whether or not planed, sanded or end‐jointed, of a thickness exceeding 6 mm. Other |

Included in Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2018/2019. Requires inspection (See 2000/29 EC Annex V B Section I 6 b) |

| 4408 90 | Sheets for veneering (including those obtained by slicing laminated wood), for plywood or for similar laminated wood and other wood, sawn lengthwise, sliced or peeled, whether or not planed, sanded, spliced or end‐jointed, of a thickness not exceeding 6 mm. Other | No phytosanitary measures required. Highly processed. |

| 4409 29 | Wood (including strips and friezes for parquet flooring, not assembled) continuously shaped (tongued, grooved, rebated, chamfered, V‐jointed, beaded, moulded, rounded or the like) along any of its edges, ends or faces, whether or not planed, sanded or end‐jointed. Non‐coniferous. Other | No phytosanitary measures required. Highly processed |

| 4410 | Particle board, oriented strand board (OSB) and similar board (e.g. waferboard) of wood or other ligneous materials, whether or not agglomerated with resins or other organic binding substances | No phytosanitary measures required. Highly processed |

| 4411 | Fibreboard of wood or other ligneous materials, whether or not bonded with resins or other organic substances | No phytosanitary measures required. Highly processed |

| 4412 | Plywood, veneered panels and similar laminated wood | No phytosanitary measures required. Highly processed |

Chapter 44. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1602 of 11 October 2018 amending Annex I to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2658/87 on the tariff and statistical nomenclature and on the Common Customs Tariff. Official Journal of the European Union L273, 61, 31 October 2018. (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2018:273:FULL%26from=ENCN Code)

3.4.2.4. Elm wood imports

Elm wood is relatively scarce in trade and only a small amount of elm is exported from USA (Cassens, 2007). Nevertheless, rough‐wood logs are shipped from North America to Europe.

Elm wood, Ulmus spp., is not itemised in trade nomenclature. The international nomenclature and codification system used to record trade statistics are not sufficiently detailed to determine the amount of trade specifically in elm wood. Table 5 details import classifications sub‐summing elm wood and derived products. CN 4403 (wood in the rough, whether or not stripped of bark or sapwood, or roughly squared, not treated) recognises subclass CN 4403 99 00 for rough hardwood not itemised and thus would include elm; CN 4407 (Wood sawn or chipped lengthwise, sliced or peeled, whether or not planed, sanded or end‐jointed, of a thickness exceeding 6 mm.) recognises a sub‐class CN 4407 99 for all sawn non‐tropical hardwoods not itemised and thus would include elm.

3.4.2.5. Import volume

Eurostat statistics based on customs records of import do not explicitly itemise elm wood. Estimation thus combines secondary indicators. Luppold and Thomas (1991) estimated the volume of annual exports of individual hardwoods from USA to European countries for the years 1981–1989. The mean volume of elm hardwood was 311 m3 per year (minimum 24 m3; maximum 807 m3). The density of elm wood can be estimated by assuming 12% moisture and is estimated as 593 kg m−3 (source: http://www.americanhardwood.org). Hence, between 1981 and 1989, a mean of 185 tonnes of elm wood was imported annually into the EU (range 14–479 tonnes; Table 6). 75% of US elm exports to the EU went to Italy, 18% to France, 5% to UK and 2% to BENELUX (Luppold and Thomas, 1991) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Estimated annual volumes and weight of elm wood imported into EU from USA 1981–1989 (Source: Luppold and Thomas, 1991)

| Year | Volume (m3) | Weight (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 300 | 178 |

| 1982 | 404 | 240 |

| 1983 | 191 | 113 |

| 1984 | 175 | 104 |

| 1985 | 807 | 479 |

| 1986 | 24 | 14 |

| 1987 | 28 | 17 |

| 1988 | 300 | 78 |

| 1989 | 573 | 340 |

| Annual mean | 311 | 185 |

| Minimum | 24 | 14 |

| Maximum | 807 | 479 |

In more recent years, the import volume of two main wood categories sub‐summing elm wood (CN 4403 99 and 4407 99) is available and is reported by weight (Table 7).

Table 7.

Import of rough wood (CN 4403 99) and sawn wood (CN 4407 99) potentially containing Ulmus species, from USA 2014 to 2018, into EU members states previously known to import US elm wood, (tonnes). Source: Eurostat

| Code/wood type | Importer | 2014 | 2015 | Year 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN 4403 99 rough wood | Italy | 33,976 | 39,910 | 37,627 | 37,259 | 34,354 |

| France | 284 | 102 | 366 | 19 | 0 | |

| UK | 345 | 307 | 158 | 213 | 93 | |

| sum | 34,605 | 40,319 | 38,151 | 37,492 | 34,447 | |

| CN 4407 99 sawn wood | Italy | 30,091 | 22,992 | 21,198 | 19,787 | 18,835 |

| France | 24,205 | 22,963 | 24,205 | 7,472 | 9,162 | |

| UK | 777 | 731 | 791 | 409 | 485 | |

| sum | 55,072 | 46,686 | 46,194 | 27,667 | 28,481 | |

| CN 4403 99 + CN 4407 99 | 89,677 | 87,005 | 84,345 | 65,159 | 62,928 |

The two data sources (Tables 6 and 7) were combined using earlier available Eurostat data from 1988. In 1988, a combined total of 148,332 tonnes of ‘rough wood, other’ (CN 4403 99) and ‘sawn wood, other’ (CN 4407 99) were imported into Italy, France and UK from USA. In 1989, the figure was 156,245 tonnes. According to Table 6 (Luppold and Thomas, 1991), approximately 178 tonnes of elm wood was imported into the EU (Italy, France and UK) in 1988 and 340 tonnes in 1989. Assuming all elm wood from USA was classified as either CN 4403 99 or CN 4407 99 then in 1988 0.12% (178/148,332) of rough and sawn wood ‘other’ entering the EU from USA was elm. Similarly, in 1989, approximately 0.22% (340/156,245) may have been elm.

Applying these estimates of 0.12% and 0.22% to the recent imports (Table 8) would suggest that between 63 and almost 180 tonnes of elm wood arrived in the EU each year between 2014 and 2018 from the USA, although the trend is downwards (Table 8).

Table 8.

Estimated annual amount of elm wood in tonnes imported from USA into the EU (Italy, France, UK), 2014–2018

| Elm wood | Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Combined total of rough wood and sawn wood ‘other’ | 89,677 | 87,005 | 84,345 | 65,159 | 62,928 |

| Elm estimate assuming 0.12% | 90 | 87 | 84 | 65 | 63 |

| Elm estimate assuming 0.22% | 179 | 174 | 169 | 130 | 126 |

EU member states were approached by EFSA and asked for information on the amount of elm logs imported annually from North America since 2016 (more information in Appendix F). Results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Annual weight in tonnes of elm logs imported into EU member states from North America 2016–2019. (Note that 2019 is not a full year). (Source: replies to EFSA from individual member states, October 2019). Data were rounded to the nearest whole tonne. In some cases, weight was derived assuming a reference density (see Appendix F)

| EU member state | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 133 | 113 | 41 | 143 |

| Germany | 38 | 62 | 31 | 26 |

| Portugal | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Croatia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyprus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| France | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Poland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweden | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The Netherlands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sum | 171 | 175 | 76 | 169 |

| Denmarka | 98 | 7,827 | 32 | 2 |

Data for Denmark refers to any type of wood of Ulmus, not only logs.

From replies received from individual member states, annual imports of elm logs into the EU from North America ranged from 76 to 175 tonnes (Table 9). These figures are similar to the estimates made in Table 8 suggesting between 63 and almost 180 tonnes of elm wood arrived in the EU each year between 2014 and 2018.

Denmark was unable to provide data on the tonnage of logs of Ulmus imported but was able to provide data on the imported volume (m3) including all types of wood of Ulmus which are under phytosanitary import provisions and have been inspected on import.

3.4.3. Establishment

3.4.3.1.

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory? (Yes or No)

If European elms and/or maple and poplar species are hosts of S. tridentata, establishment is possible.

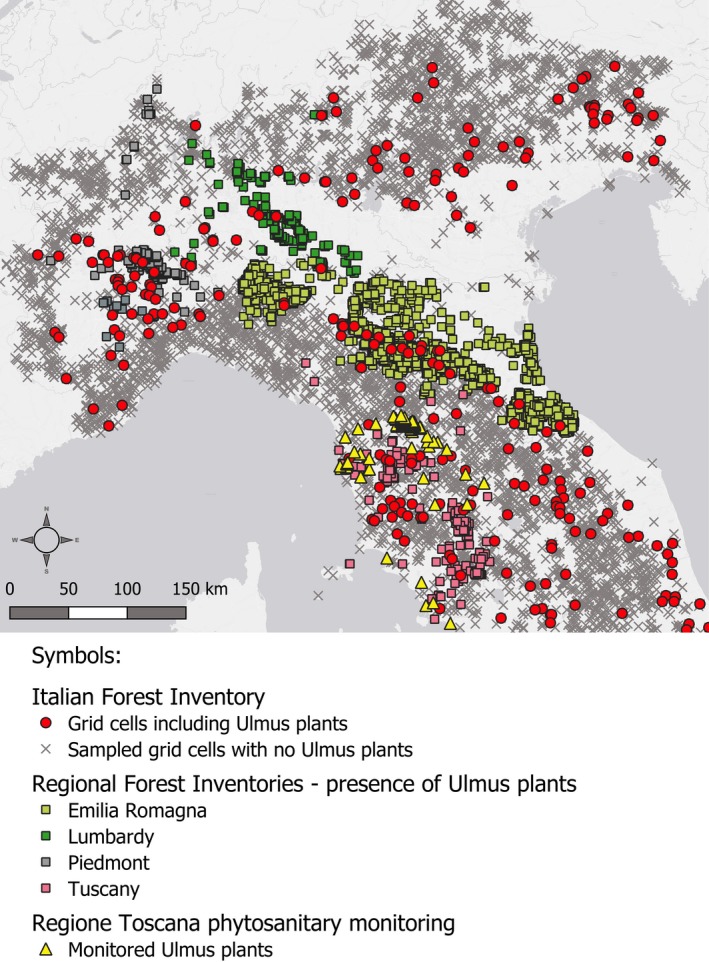

3.4.3.2. EU distribution of main host plants

Within Europe, there are limited number of arboreta where American species of elm such as U. americana and U. rubra grow (Table 10). Data of individual stand distributions are not accessible. Arboreta are assumed to be isolated and widely spread out (i.e. distances between arboreta exceed the range of adult flight capacity). There may be other American elms in private gardens and parks, but abundance and density are not known (see e.g. https://www.gbif.org/species/5361872). It is suggested that S. tridentata is unlikely to be able to establish if American elms are the only hosts. European elm species are more abundant but not known to be hosts. However, it has also not been proven that European elms are not hosts. The argument is valid also with Acer and Populus. If European elms, Acer and Populus are genuine hosts (see Section 3.4.1) and S. tridentata demonstrated a shift in host preference to European elms, Acer (maple) and Populus (poplar) in the EU, then hosts would be ubiquitous, and conditions would be conducive to establishment.

Table 10.

Number of gardens/arboreta in EU MS that are recorded as having North American elm species. Whether sites have only single specimens or multiple plantings is not known (Source: https://tools.bgci.org/global_tree_search.php)

| Country | U. americana | U. rubra | U. crassifolia | U. thomasii | U. serotina | U. alata | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 18 |

| Germany | 7 | 3 | 10 | ||||

| Belgium | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Finland | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| France | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Sweden | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Czech Republic | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Latvia | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Spain | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Estonia | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Sum | 26 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 53 |

3.4.3.3. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

The distribution and abundance of an organism that cannot control or regulate its body temperature are largely determined by host distribution and climate.

Comparing climates from the known distribution of an organism with climates in the risk assessment area can inform judgements regarding the potential distribution and abundance of an organism in the risk assessment area (Sutherst and Maywald, 1985; Ehrlén and Morris, 2015). The global Köppen–Geiger climate zone categories, and subsequent modifications made by Trewartha and Horn (1980), describe terrestrial climate in terms of factors such as average minimum winter temperatures and summer maxima, amount of precipitation and seasonality (rainfall pattern) (Trewartha and Horn, 1980; Kottek et al., 2006) and can inform judgements of aspects of establishment during pest categorisation (MacLeod and Korycinska, 2019).

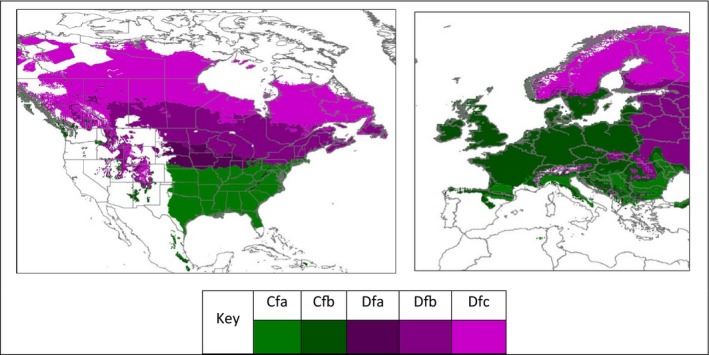

Climate types found in regions of North America where S. tridentata occurs are also found in Europe (Figures 1 and 3) suggesting that climate would support the establishment of S. tridentata in large parts of the EU.

Figure 3.

Occurrence of Köppen–Geiger climates (Trewartha and Horn, 1980) in North America (left pane) within which S. tridentata occurs and the same climates in Europe (right pane). The pane at the bottom shows the key scheme colour used for the different climates: Cfa = Humid subtropical climate, Cfb = Temperate oceanic climate, Dfa = Hot summer humid continental climate, Dfb = Warm summer humid continental climate, Dfc = Subarctic climate

3.4.4. Spread

3.4.4.1.

Is the pest able to spread within the EU territory following establishment?

Yes. If S. tridentata did establish it could spread. The species is a free‐living organism, adults can fly.

RNQPs: Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects?

No. S. tridentata would not mainly spread via plants for planting.

Adults fly during the night. They tend not to disperse far if hosts are available locally (Hanks, 1999). The dispersal of S. tridentata, like that of other cerambycids such as S. candida and S. inornata, is influenced by the dietary requirements of adults and host requirements of the larvae. Females may oviposit on their natal host if its condition has not declined too greatly; such behaviour results in adults appearing to be relatively sedentary with a disinclination to disperse (Hanks, 1999).

S. tridentata has slowly spread within the USA and Canada. The species was known to occur in the eastern states of the USA and in eastern Canada in the late 1790s and was recorded in Idaho in 2017 (Rice et al., 2017). Whether recorded spread is related to recording effort, natural spread or spread on host plant material, such as infested Ulmus wood, is unknown.

3.5. Impacts

3.5.1.

Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

The preference for weakened trees might generally limit the potential impact.

No, if S. tridentata does not feed on European species of elm impacts would be limited to isolated species of American elm growing in Europe, assuming S. tridentata could locate them.

Yes, if weakened trees of elms, poplars, or maples are hosts for S. tridentata there is likely to be an impact in the EU territory.

RNQPs: Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting?

Yes. The occurrence of S. tridentata on plants for planting could have an economic impact on the intended use of those plants. Infested plants would be introducing a potentially serious pest that could spread and kill other hosts close by. However, the stem size of such plants for planting may limit final development of the pest to the adult stage.

As the pest is not present in the EU impact estimates are based on reports for North America.

S. tridentata prefers trees suffering a lack of nutrients or moisture (Campbell et al., 1989) or are otherwise stressed or weakened. Tucker (1907) reported that there was no evidence that adults oviposit in healthy trees. Hanks (1999) considers S. tridentata to be a species that specialises in attacking host plants whose defences have been compromised in some way, such as by chronically poor growing conditions or pathogen infestation. Urban habitats (typical for elm) might make trees more prone to attack by S. tridentata. The impact of S. tridentata could be to speed up the decline of a weakened tree that was already deteriorating.

Environmental impacts would be confined to already weakened or stressed individual hosts that were located and attacked. Whilst adult feeding damages leaves and twigs, it is the feeding and tunnelling of larvae within the cambium and phloem, inner bark and sapwood, of already weakened or stressed hosts that causes most damage. Infested trees tend to die slowly, a branch at a time (Drooz, 1985) although all parts can be attacked from small branches to the main trunk. The upper branches are usually affected first. Subsequent generations will work down an infected tree. Larval mines can girdle branches killing them; when abundant larval tunnelling can girdle the trunk causing the death of the tree (Hoffmann, 1942; Krischik and Davidson, 2013). Trees can be killed after 2 or 3 years (Packard, 1890). Roots are not attacked (Packard, 1890). Rows of elms in urban areas would gradually be attacked as subsequent generations of adult S. tridentata spread from tree to tree.

S. tridentata is more injurious in USA than in Canada (Campbell et al., 1989) perhaps because larvae develop more slowly further north in cooler climates.

Elm is a valued component of the urban forest as a shade provider although Dutch elm disease has greatly reduced the population of elms both in North America and Europe (Allen and Humble, 2002). Historically elm wood was used for barrel hoops and staves, boxes, crates, curved wooden parts of furniture, and panelling, more recently, in areas where the amount of elm wood available has declined (due to Dutch elm disease), it is used for pallets and solid wood packing material (Cassens, 2007). Elm wood is also used to make hockey sticks, veneer, wood pulp and in papermaking (https://www.wood-database.com/american-elm/). When sawn, elm is mainly used to make planks 25.4 mm thick.

Extrapolating information on consequences from the native range of the S. tridentata, a potential introduction of the organism into the EU territory likely is limited to weakened trees. If S. tridentata does neither feed on European species of elm nor on Acer or Populus impacts would be limited to isolated species of American elm growing in EU, assuming S. tridentata could locate them. If, however, S. tridentata feed on trees of elms, poplars or maples, there is likely to be an environmental and/or economic impact in the EU territory. Scarce evidence on precise host range of S. tridentata in the EU territory does not support any of the impact scenarios over the other.

3.6. Availability and limits of mitigation measures

3.6.1.

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, measures used for Agrilus planipennis could be appropriate (Table 2) and those in 3.6.1. However, parameters of mechanical treatment (i.e. removal of 2.5 cm in sapwood) need to be confirmed.

RNQPs: Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, plant from planting from pest free areas.

3.6.2. Identification of additional measures

Phytosanitary measures are currently applied to Ulmus plants for planting from North America for the control of elm phloem necrosis (see Section 3.3).

Rough wood and sawn wood consignments require inspection (see Section 3.3.2). The existing general requirements are not specific to S. tridentata but inhibit the entry of many pests.

3.6.2.1. Additional control measures

Potential additional control measures are listed in Table 11.

Table 11.

Selected control measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel et al., 2018) for pest entry/establishment/spread/impact in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance

| Information sheet title (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Control measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| https://zenodo.org/record/1311026#.XchtZ-eTLVo |

Use of chemical compounds that may be applied to plants or to plant products after harvest, during process or packaging operations and storage. The treatments addressed in this information sheet are: a) fumigation; b) spraying/dipping pesticides; c) surface disinfectants; d) process additives; e) protective compounds |

Entry. Fumigants available. In principle applicable but challenging to put into practice for large timbers. |

| https://zenodo.org/record/1311058#.XchuAueTLVo | This information sheet deals with the following categories of physical treatments: irradiation/ionisation; mechanical cleaning (brushing, washing); sorting and grading, and removal of plant parts (e.g. debarking wood). This information sheet does not address: heat and cold treatment (information sheet 1.14); roughing and pruning (information sheet 1.12) |

Entry. Rough wood should be bark free rather than debarked to reduce the likelihood of entry |

| Heat and cold treatments | Controlled temperature treatments aimed to kill or inactivate pests without causing any unacceptable prejudice to the treated material itself. The measures addressed in this information sheet are: autoclaving; steam; hot water; hot air; cold treatment |

Entry. Equipment available. For large timbers complex in routine practice. |

| Roguing and pruning of infested brunches | If detected sufficiently early, pruning and burning of infested branches could remove infestations within individual trees | Establishment, Spread. |

| Felling and burning of infested trees | Felling and burning of infested trees to reduce the spread to neighbouring hosts. | Spread. |

| Insecticides targeting adults | Insecticides targeting adults could be applied to foliage; insecticides with long‐lasting residual activity could be applied to trunks | Spread. Reduce establishment. |

3.6.2.2. Additional supporting measures

Potential additional supporting measures are listed in Table 12.

Table 12.

Selected supporting measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance

| Information sheet title (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Supporting measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| https://zenodo.org/record/1311135#.XchvGueTLVo |

Inspection is defined as the official visual examination of plants, plant products or other regulated articles to determine if pests are present or to determine compliance with phytosanitary regulations (ISPM 5). The effectiveness of sampling and subsequent inspection to detect pests may be enhanced by including trapping and luring techniques. |

Light traps at ports of entry and inland at sites for wood distribution could be used to monitor for adults emerging from imported wood. Establishment |

| Encourage tree health and vigour | S. tridentata attacks weakened trees therefore practices that encourage tree health and vigour such as site selection, mulching and watering. | Establishment, spread, impact. |

3.7. Uncertainty

The precise hosts of S. tridentata in the EU are unknown and judgements about the expected establishment and/or spread come with high uncertainty. These critical uncertainties are not expected to lessen by conducting risk assessment.

Host diversity and plasticity of S. tridentata are unknown due to inconclusive anecdotal evidence and lack of experimental studies. Indicative reports on diverse species, other than North American elms, are isolated, mostly inconclusive/speculative in biological relevance, and not representative of any situation in the EU. Categorisation of the potential to establish within EU is highly uncertain and driven by assumptions regarding hosts.

Assuming European elms could be hosts of S. tridentata in the EU, still the occurrence, density and distribution of European elms in Europe is uncertain. The categorisation of capability to spread is highly uncertain as to whether there are enough hosts at local reach to enable the establishment of S. tridentata (i.e. perpetuate for the foreseeable future).

4. Conclusions

Table 13 provides a summary of the conclusions of each part of this pest categorisation.

Table 13.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criteria in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pests (Section 3.1 ) | S. tridentata Olivier, (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) is a well‐established and recognised pest | None |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) | S. tridentata is not known to occur in the EU. The pest occurs in eastern North America (USA and Canada) | A few interceptions have been recorded |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3 ) | S. tridentata is not under official control | |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) |

Entry is possible (proven by interceptions). If European elms and/or maple and poplar species are hosts of S. tridentata, then establishment is possible. Spread is possible as S. tridentata is a free‐living organism and adults can fly |

High uncertainty level. No experimental data; only anecdotal evidence; inadequate information on the precise host range in the EU. |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) | If S. tridentata does not feed on European species of elm, impacts would be limited to isolated species of American elm growing in Europe, assuming S. tridentata could locate them. The preference for weakened trees might generally limit the potential impact. If European elms, poplars or maples are hosts for S. tridentata, there is likely to be an impact in the EU territory | High uncertainty level. No experimental evidence (e.g. choice experiments) to anticipate behaviour when known hosts (American elms) are scarce. |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Measures for wood‐inhabiting beetles with similar biology are available | Efficacy of measures unknown against S. tridentata |

|

Conclusion on pest categorisation (Section 4 ) |

Information on geographical distribution, biology, epidemiology, impact and potential entry pathways of S. tridentata has been evaluated against the criteria for it to qualify as potential Union quarantine pest or as Union regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP). Since the pest is not reported in EU or plants for planting are not the principal means of spread, it does not meet the criteria assessed by EFSA to qualify as potential Union regulated non‐quarantine pest. S. tridentata satisfies the criterion regarding entry into the EU territory. Due to the scarcity of data, the Panel is unable to conclude if S. tridentata meets the post‐entry criteria of establishment, spread and potential impact | Uncertainty regarding the precise host range and behaviour in the EU cannot be reduced by any subsequent risk assessment without new experimental evidence in these regards |

| Aspects of the assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in the future if appropriate | As it is, there is little reason to believe there are hosts on the European continent except those American elms in arboreta, but a host shift cannot be excluded as a possibility. A firm conclusion on all criteria of the categorisation can be achieved through gathering conclusive experimental evidence about the precise host range and behaviour in the EU | |

Glossary

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2017)

- Establishment (of a pest)

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2017)

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2017)

- Measures

Control (of a pest) is defined in ISPM 5 (FAO 2017) as “Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population” (FAO, 1995). Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate Risk Reduction Options that do not directly affect pest abundance.

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2017)

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2017)

- Protected zones (PZ)

A Protected zone is an area recognised at EU level to be free from a harmful organism, which is established in one or more other parts of the Union.

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Regulated non‐quarantine pest

A non‐quarantine pest whose presence in plants for planting affects the intended use of those plants with an economically unacceptable impact and which is therefore regulated within the territory of the importing contracting party (FAO, 2017)

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO, 2017)

Abbreviations

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

Protected Zone

- RNQP

regulated non‐quarantine pest

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

Appendices to the Pest Categorisation on Saperda tridentata

To further inform decision‐making regarding the quarantine status of S. tridentata in the EU, the EFSA PLH Panel collected accessible information and observational knowledge supporting conclusions. The outcome is collated within the Appendices (Appendices A–F). The extra information and data were thought useful given the uncertainties about the host range of S. tridentata in EU. Nevertheless, interpretation of the data and information requires caution due to the non‐systematic collection, patchy accessibility and observational character (data assembled for different purposes).

List of Appendices:

Appendix A – Detailed Saperda tridentata global distribution

Appendix B – Host plants of North American Saperda species, other than S. tridentata

Appendix C – Host plants of non‐North American Saperda species

Appendix D – Literature search and review on S. tridentata hosts

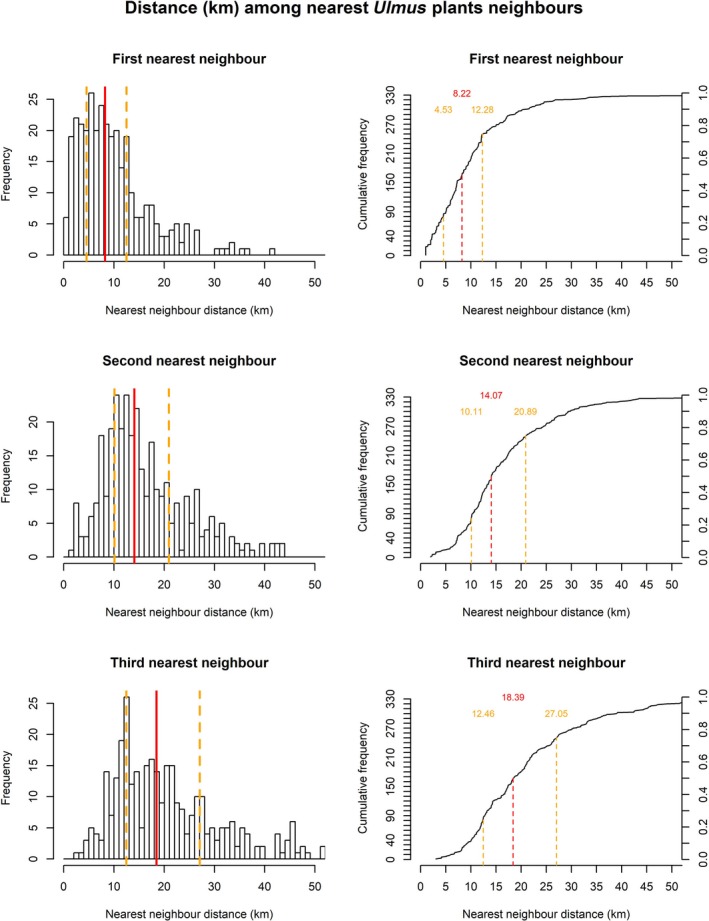

Appendix E – Scoping review on the flight capacity of adult Saperda tridentata and other Cerambycidae, and analysis of spatial separation of European elm trees in Northern Italy

Appendix F – Ulmus logs imports in Europe.

Appendix A – Detailed Saperda tridentata global distribution

1.

Table A.1.

S. tridentata global distribution according to the online EPPO Global database (https://gd.eppo.int/). Last access: 7 November 2019

| Continent | Country | Sub‐national distribution | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Canada | Present, restricted distribution | |

| Manitoba | Present, no details | ||

| New Brunswick | Present, no details | ||

| Nova Scotia | Present, no details | ||

| Ontario | Present, no details | ||

| Québec | Present, no details | ||

| Saskatchewan | Present, no details | ||

| USA | Present, restricted distribution | ||

| Alabama | Present, no details | ||

| Arkansas | Present, no details | ||

| Colorado | Present, no details | ||

| Connecticut | Present, no details | ||

| Florida | Present, restricted distribution | ||

| Georgia | Present, no details | ||

| Idaho | Present, no details | ||

| Illinois | Present, no details | ||

| Indiana | Present, no details | ||

| Iowa | Present, no details | ||

| Kansas | Present, no details | ||

| Kentucky | Present, no details | ||

| Maine | Present, no details | ||

| Maryland | Present, no details | ||

| Massachusetts | Present, no details | ||

| Michigan | Present, no details | ||

| Minnesota | Present, no details | ||

| Mississippi | Present, no details | ||

| Missouri | Present, no details | ||

| Montana | Present, restricted distribution | ||

| Nebraska | Present, no details | ||

| New Hampshire | Present, no details | ||

| New Jersey | Present, no details | ||

| New York | Present, no details | ||

| North Carolina | Present, no details | ||

| North Dakota | Present, no details | ||

| Ohio | Present, no details | ||

| Oklahoma | Present, no details | ||

| Pennsylvania | Present, no details | ||

| Rhode Island | Present, no details | ||

| South Carolina | Present, no details | ||

| South Dakota | Present, no details | ||

| Tennessee | Present, no details | ||

| Texas | Present, no details | ||

| Vermont | Present, no details | ||

| West Virginia | Present, no details | ||

| Wisconsin | Present, no details |

Appendix B – Host plants of North American Saperda species, other than S. tridentata

1.

Table B.1 includes a list of host plants of North American Saperda species, other than S. tridentata based on Felt and Joutel (1904), Zasada and Phipps (1990), Nord et al. (1972), and the http://titan.gbif.fr website.

Table B.1.

List of host plants of North American Saperda species, other than S. tridentata (Sources: a = Felt and Joutel, 1904; b = http://titan.gbif.fr/sel_plantes1.php?numplantes=7140; c = Zasada and Phipps, 1990; d = Nord et al., 1972)

| HOST FAMILY Genus species | North American Saperda spp. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. imitans | S. discoidea | S. lateralis | S. vestita | S. candida | S. puncticolis | S. moesta | S. cretata | S. fayi | S. calcarata | S. obliqua | S. inornata | S. horni | S. mutica | |

| ACERACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Acer sp. | b | |||||||||||||

| ANACARDIACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Rhus radicans | a | |||||||||||||

| Rhus toxicodendron | a | |||||||||||||

| Toxicodendron radicans | a | |||||||||||||

| BETULACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Alnus serrulata | a | |||||||||||||

| Betula sp. | b | a | ||||||||||||

| BURCERACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Cammiphora opobalsamum | a | |||||||||||||

| CARYOCARACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Caryocar sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| CORNACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Cornus sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| JUGLANDACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Carya amara | a | |||||||||||||

| Carya cordiformis | a | a | ||||||||||||

| Carya glabra | a | a | ||||||||||||

| Carya ovata | a | |||||||||||||

| Juglans nigra | a | |||||||||||||

| ROSACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Amelanchier alnifolia | a | |||||||||||||

| Amelanchier arborea | a | |||||||||||||

| Amelanchier canadensis | a | |||||||||||||

| Aronia sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Cotoneaster sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Crataegus crus‐galli | a | |||||||||||||

| Crataegus oxyacantha | a | |||||||||||||

| Crataegus phaenopyrum | a | |||||||||||||

| Crataegus sp. | a | a | a | a | ||||||||||

| Crataegus tomentosa | a | |||||||||||||

| Cydonia oblonga | a | |||||||||||||

| Malus sp | a | a | a | |||||||||||

| Prunus avium | a | |||||||||||||

| Prunus domestica | a | |||||||||||||

| Prunus sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Pyracantha sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Pyrus communis | a | |||||||||||||

| Sorbus americana | a | |||||||||||||

| SALICACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Populus balsamifera | a | c | a | |||||||||||

| Populus deltoides | a | |||||||||||||

| Populus grandidentata | a | |||||||||||||

| Populus nigra | a | |||||||||||||

| Populus sp. | a | a | ||||||||||||

| Populus tremuloides | a | d | ||||||||||||

| Salix lasiolepis | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix scouleriana | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix bebbiana | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix concolor | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix discolor | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix humilis | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix interior | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix petiolaris | a | |||||||||||||

| Salix sp. | a | a | a | a | a | a | ||||||||

| TILIACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Tilia americana | a | |||||||||||||

| Tilia sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| ULMACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Ulmus sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Ulmus rubra | a | |||||||||||||

| VITACEAE | ||||||||||||||

| Parthenocissus engelmannii | a | |||||||||||||

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia | a | |||||||||||||

| Vitis sp. | a | |||||||||||||

| Number of host families | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of host genera | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

References

Felt EM, and Joutel L, 1904. “Monograph of the genus Saperda,” New York State Education Dept., Albany.

Nord JC, Grimble DG, and Knight FB, 1972. Biology of Saperda inornata (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in Trembling Aspen, Populus Iremuloides1. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 65, 127–135.

Zasada JC, and HPhipps HM, 1990. Populus balsamifera L. ‐ Balsam Poplar. In “Silvics of North America ‐ Volume 2, Hardwoods” (R. M. Burns and B. H. Honkala, eds.), pp. 518–529. Forest Service, United Service Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

Appendix C – Host plants of non‐North American Saperda species

1.

Table C.1 includes a list of host plants of non‐North American Saperda species.

Table C.1.

List of host plants of non‐North American Saperda species

| Saperda species | Distribution | Hosts | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. alberti | Asia (Japan, North Korea, China, Mongolia, Russia) |

Salix Populus |

Cherepanov (1991) |

| S. bacillicornis | China | Salix |

Wallin et al. (2017) Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. balsamifera | Siberia, NE China, Korea, Japan |

Populus alba Salix |

Sheng and Hilszczanski (2009) Cherepanov (1991) |

| S. bilineatocollis | China, Russia | Unknown |

Danilevsky (2010) Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. carcharias | Europe, northern Asia, China, Korea |

Alnus Populus Prunus Quercus Salix |

Cherepanov (1991) Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. facetula | Vietnam | Unknown ‐ | Holzschuh (1999) |

| S. gilanense | Iran | Unknown | Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. gleneoides | Laos, Vietnam | Unknown | Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. interrupta | Siberia, NE China, Korea, Japan |

Abies (fir) Picea (spruce) Pinus (pine) other conifers |

Cherepanov (1991) |

| S. kojimai | Taiwan | Unknown | Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |

| S. maculosa |

Iran, Transcaspia (=Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan Uzbekistan) |

Unknown | Tavakilian and Chevillotte (2019) |