Abstract

Efforts to sequence single protein molecules in nanopores1–5 have been hampered by the insufficient sensitivity of a conventional nanopore measurement for identification of the few atom differences among the amino acids. Here we report ionic current detection of all twenty proteinogenic amino acids in an aerolysin nanopore with the help of a short polycationic carrier. According to molecular dynamics simulations, the aerolysin nanopore has a built-in single-molecule trap that fully confines a polycationic carrier-bound amino acid inside the aerolysin’s sensing region, giving ample time for sensitive measurement of the amino acid’s excluded volume. Experimentally, we show that distinct current blockades in wild-type aerolysin can be used to identify thirteen of the twenty natural amino acids. Furthermore, we show that chemical modifications, instrumentation advances and nanopore engineering offer a route towards identification of the remaining seven amino acids. These findings could pave the way to nanopore protein sequencing.

Reporting summary.

Further information is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this letter.

Single-molecule protein sequencing is the next frontier of biomolecular analytics6. In contrast to nucleic acids, where new methods of sequencing are being proposed and realized every year7, protein sequencing relies on just two decades-old approaches: Edman degradation8, and mass-spectrometry9, neither of which offers single molecule resolution. Miniaturization, parallelization and automatization continue to improve the efficiency of both methods, and new approaches to protein sequencing are now being reported, including fluorosequencing10, FRET fingerprinting11 and nanopore sequencing1, 5, 6, 12, 13.

In nanopore sequencing a peptide chain is driven through a nanopore by either an external electric field2, 5 or the pull of a molecular motor1, 12. The amino acid sequence of the peptide is identified by various methods, including measurement of nanopore ionic current5, 14–18, measurement of the transverse tunneling current3, 4, using a modified mass spectrometer19 or by splitting a protein into multiple fragments and using the ionic current signatures of the fragments to identify the protein (rather like conventional mass spectrometry)20. Nanopore sequencing of proteins faces additional challenges6, compared with nanopore sequencing of DNA21–23, such as realizing a unidirectional transport of heterogeneously-charged peptide chains through a nanopore and electrical recognition of individual amino acids.

Here, we present evidence that a wild-type aerolysin nanopore can detect and characterize all twenty proteinogenic amino acids. We chemically linked single amino acids to a short polycationic carrier˗˗arginine heptapeptide (Fig. 1a) to enable capture by the nanopore, because heptapeptides have been shown to produce well-defined ionic current blockades in an aerolysin nanopore24.

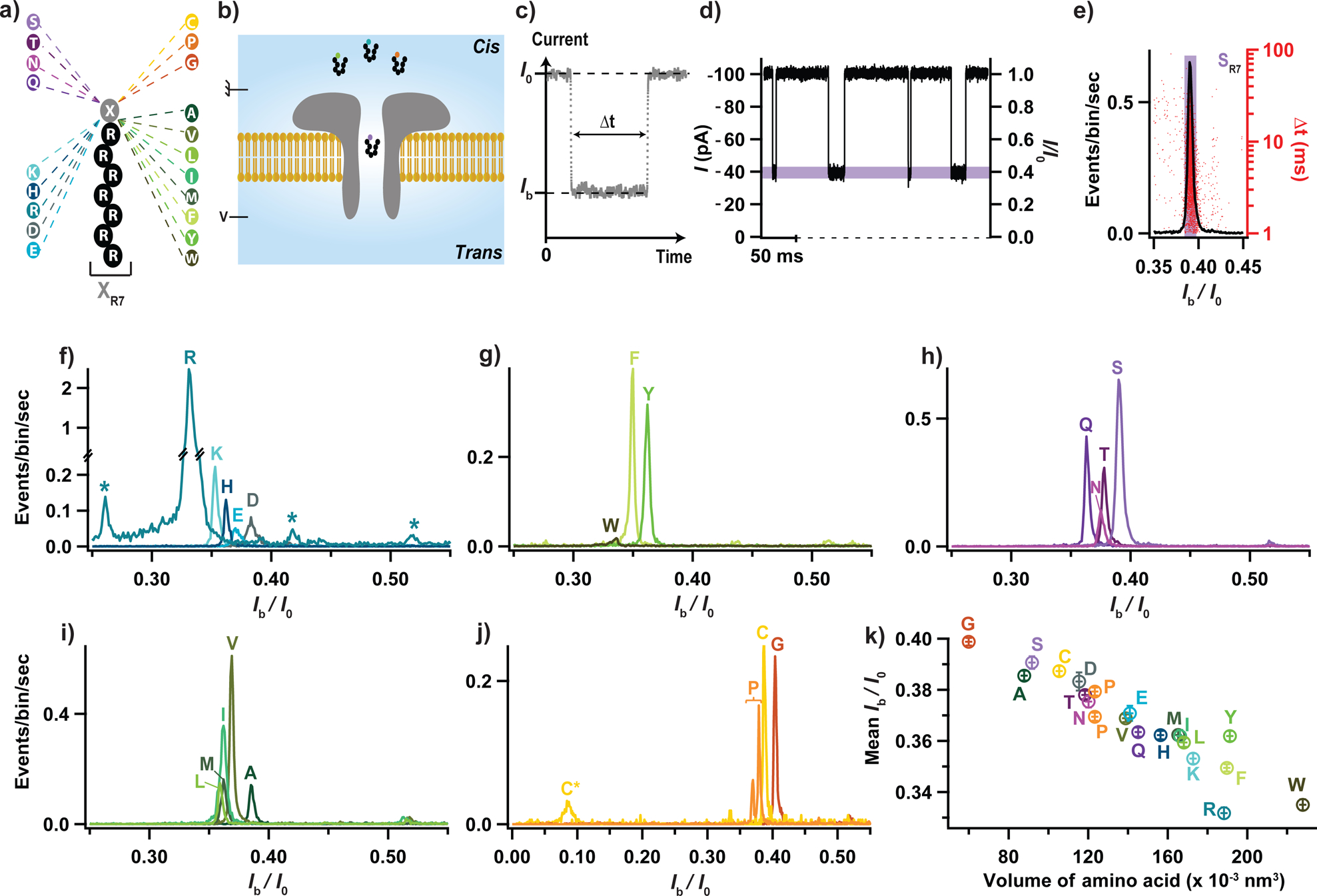

Figure 1: Electrical detection of the twenty proteinogenic amino acids.

(a) Schematic illustration of the peptide constructs used to probe the current blockade of the twenty amino acids. A cationic carrier of seven arginine amino acids (R7) is chemically linked at the C-terminus to the eighth amino acid, X, to form twenty XR7 peptides. (b) Schematics of the experimental setup (not to scale). (c) Illustration of a typical current blockade. (d) Representative fragment of ionic current recording. (e) Typical histogram of the relative residual current, Ib/I0 (left axis), and blockade duration, Δt (right axis), produced by the transport of SR7 peptides through the aerolysin nanopore. (f-j) Superimposed histograms of Ib/I0 obtained from nanopore experiments performed for each of the twenty XR7 peptides, analyzed individually and grouped according to the properties of amino acid X: charged (f), hydrophobic aromatic (g), polar uncharged (h), hydrophobic non-aromatic (i), and when amino acid X is either cytosine, proline or glycine (j). In panel f, stars indicate blockade levels likely produced by R9, R7 and R6 polyarginine impurities (from left to right) present in the RR7 sample. In panel j, C* and C indicate populations recorded before and after dithiothreitol treatment, see Supplementary Fig. 1. (k) Mean relative residual current and its standard deviation produced by the XR7 probes versus volume of amino acid X. All data were acquired in 4 M KCl, 25 mM HEPES buffer, at 7.5 pH, 1 μM peptide concentration, 20.0 ± 0.5°C, and under a −50 mV bias applied to the trans compartment. For each histogram, at least 1000 events were analyzed.

In a typical experiment (Fig. 1b), a single wild-type aerolysin nanopore is inserted in a lipid bilayer that separates cis and trans compartments that contain an electrolyte solution. An external negative voltage (−50 mV) is applied on the trans side of the bilayer, whilst the cis side is electrically grounded. In the absence of peptides, a steady ionic current of mean value I0 flows through the nanopore. The addition of peptides on the cis side of the bilayer induces transient blockades of the ionic current (Fig. 1c & d). Each current blockade corresponds to the presence of an individual peptide in the nanopore, and is characterized by the mean residual current Ib and the blockade duration Δt (Fig. 1c). A typical histogram of the relative residual current, Ib/I0, has a single narrow peak (Fig. 1e), which we characterize by the mean value of a Gaussian fit and its standard deviation. In the case of the SR7 (SRRRRRRR) peptide featured in Fig. 1d, Ib/I0 ≈ 0,390 ± 0.002. Similar experiments were performed separately for all twenty XR7 peptides under the same experimental conditions. The corresponding superimposed histograms of the relative residual current values are shown in Fig. 1f–j, where the data are grouped according to the family to which amino acid X belongs, i.e. electrically charged (Fig. 1f), hydrophobic aromatic (Fig. 1g), polar uncharged (Fig. 1h), hydrophobic non-aromatic (Fig. 1i) and a special case (Fig. 1j) family.

The superimposed histograms of each peptide family exhibit well-separated populations with some notable exceptions. Five populations corresponding to the five members (RR7, KR7, HR7, ER7 and DR7) of the electrically charged side chain family (Fig. 1f) can be clearly identified and distinguished from one another. Note that sub-populations tagged with an asterisk, located to the left and to the right of the RR7 population, likely correspond to arginine homopeptides impurities present in the >98% pure RR7 peptide sample, as reported previously24. One can also clearly identify and distinguish three populations corresponding to the three members (WR7, FR7, YR7) of the hydrophobic aromatic side chain family (Fig. 1g). Note that the small amplitude of the WR7 population is caused by the very low capture rate of the WR7 peptide. Four (Fig. 1h) and five (Fig. 1i) blockade current populations were also obtained for the polar uncharged (QR7, NR7, TR7, SR7) and hydrophobic non-aromatic (lR7, MR7, IR7, VR7, AR7) side chain families, respectively. Among those, the mean relative residual currents of TR7 and NR7 peptides, as well as those of LR7, MR7, and IR7 peptides, are too close to be easily distinguishable.

The superimposed histograms of the remaining three peptides (CR7, PR7 and GR7) exhibit four well-separated peaks (Fig. 1j). Indeed, PR7 peptide was found to produce two peaks with mean Ib/I0 values of 0.369 ± 0.002 and 0.379 ± 0.002. It is possible that, for the PR7 peptide, the relative residual current is sensitive to the spatial orientation of the peptide, or that the peptide has two different sites of preferred location inside the nanopore. We note that proline is the only amino acid with an alpha-amino group attached directly to the side chain. The CR7 peptide was found to produce the smallest relative residual current of all twenty XR7 peptides analyzed, 0.088 ± 0.005, which we attribute to the formation of dimers via a disulfide bond between the cysteine residues. We measured a much higher value, 0.387 ± 0.002 when we added dithiothreitol, a reducing agent of disulfide bonds (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Altogether, each of the twenty amino acids linked to the polycationic carrier produced a current blockade distinct from that of the polycationic carrier alone. Among the twenty amino acids, peptides containing R, W, F, K, L, N, T, P, D, A, C, S and G amino acids produced blockade populations distinct from one another, whereas the blockade currents of the remaining seven peptides fell within two groups, (Q, M, H, I, Y) and (E, V). The current blockades within each group were too similar to be differentiated but the current blockades of each group could be clearly distinguished from that of the rest of the peptides.

To probe the physical mechanism underlying the dependence of blockade current on amino acid type, we plotted the mean relative residual current and its standard deviation for the XR7 peptides as a function of the hydrodynamic volume25 (Fig. 1k) or the molecular mass (Supplementary Fig. 2) of the amino acid X. The residual current was found to, overall, decrease as either the excluded volume or the molecular mass increased, which is in qualitative agreement with previous experiments reporting molecular mass discrimination of neutral polymers and peptides24, 26–28. There were, however, notable exceptions, e.g., phenylalanine (F) and tyrosine (Y). Furthermore, we find isomeric amino acids leucine (L) and isoleucine (I), which have the same molecular mass, to produce distinguishable blockade currents. Overall, the mean relative residual current 〈Ib/I0〉 was found to exhibit a more systematic correlation with the hydrodynamic volume of the amino acid25 than with their molecular mass. For example, we observed distinct current blockade for amino acids having similar molecular masses but different volumes (e.g., K and E), and, vice versa, similar blockade currents for amino acids having different molar masses but similar volumes (e.g., T and N).

To determine the molecular mechanism of the blockade current modulation by the chemical structure of the XR7 peptides, we simulated ion and peptide transport through aerolysin using the all-atom MD method. Our all-atom model of the experimental system (Fig. 2a) was built using the cryo-EM structure of the aerolysin channel29, which we found to be stable when simulated in a lipid bilayer membrane (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c and Video 1), and exhibiting the expected ion conductance under a transmembrane voltage (Supplementary Fig. 3d and Video 2). The electrostatic potential map of the channel (Fig. 2b) reveals the presence of a constant-potential compartment in the middle section of the aerolysin stem, separated from the cis and trans entrances of the channel by electrostatic potential barriers. The presence of the barriers suggests that, upon entering the constant-potential compartment, a charged moiety can reside within the compartment for an extended period of time. Interestingly, the constant-potential section of the aerolysin channel disappears at elevated values of the transmembrane voltage (Fig. 2c), which is consistent with the experimentally observed loss of the peptide recognition capability at high transmembrane biases (Supplementary Fig. 4).

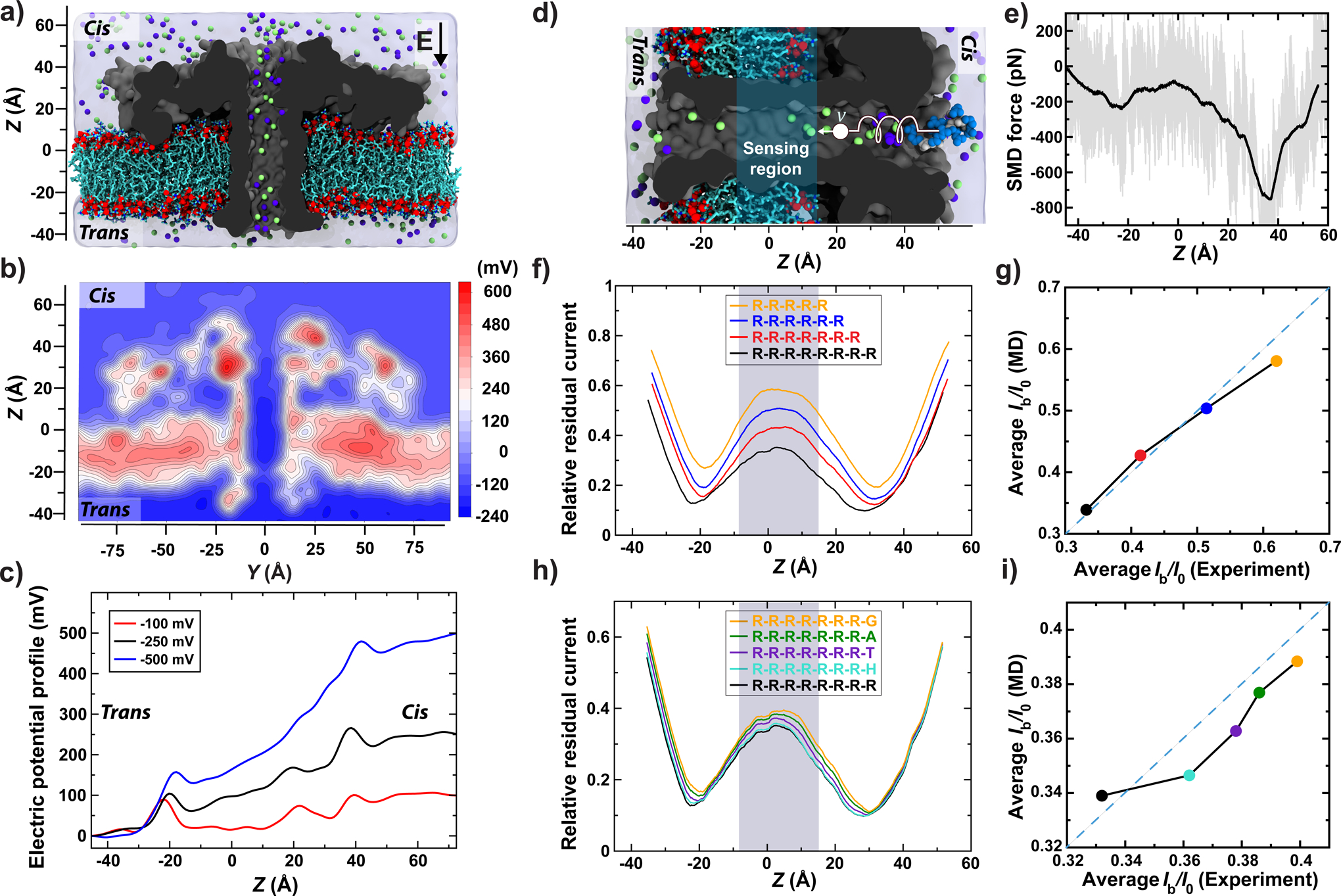

Figure 2: MD simulation of peptide translocation through aerolysin.

(a) Simulation system consisting of an aerolysin channel (cutaway molecular surface), embedded in a DPhPC membrane (cyan and red) and submerged in KCl electrolyte (blue semitransparent surface; green and purple spheres). (b) Electrostatic potential map of aerolysin at −100 mV transmembrane bias. The map was obtained by averaging instantaneous distributions of electrostatic potentials over a 20 ns MD trajectory and the six-fold symmetry of the channel. (c) Average electrostatic potential along the symmetry axis of aerolysin (the z axis). The plot was obtained by averaging instantaneous values of electrostatic potential along the symmetry axis over a 20 ns MD trajectory (10000 frames). (d) Initial state of an SMD simulation where an RR7 peptide (blue spheres) was moved through the transmembrane pore of aerolysin (grey) with a constant velocity of 1 Å/ns by means of a harmonic spring potential. For clarity, only the central part of the system is shown. The sensing region of the aerolysin pore is highlighted in cyan (same in panels f and h). (e) The force exerted on the peptide during the SMD simulation. The instantaneous SMD forces are shown in gray; their running average (5 Å window) is shown in black. (f) Relative residual current versus the CoM coordinate of RR7, RR6, RR5 and RR4 peptides. The peptides’ coordinates were derived from the conformations of RR7 sampled during the SMD simulation. The currents were computed using the steric exclusion model31 and averaged using a 10-Å running average. (g) Simulated versus experimental25 average relative currents produced by the arginine peptides within the sensing region of aerolysin. (h,i) Same as in panels f and g but for GR7, AR7, TR7, HR7 and RR7 peptides; the experimental values are reproduced from Fig. 1k. For panels g & i, the average simulated current was calculated from 130 relative residual current values corresponding to the presence of arginine peptides in the sensing region.

Next, we used the steered MD (SMD) method to simulate translocation of an RR7 peptide through the aerolysin nanopore (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Video 3). Figure 2e plots the average local force applied by the SMD method to move the peptide through the nanopore at constant velocity. The cis-side entrance to the aerolysin nanopore is seen to provide the most resistance to the peptide motion, which is in accord with the lower, overall, capture rate of aerolysin in comparison to other similar-size biological nanopores17, 18. Another major barrier is observed at the trans exit of the channel, at the same location as the trans-side electrostatic barrier (Fig. 2c). The constant-potential segment of the stem (Fig. 2b & c) is also the region where the forced displacement of the peptide encounters the least resistance, suggesting a possibility that a trapped peptide can diffuse about that segment of the stem. A repeat SMD simulation carried out using the same protocol but different initial conditions yielded quantitatively similar results (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Having obtained representative conformations of the RR7 peptide along the full length of the aerolysin nanopore, we used the steric exclusion model (SEM)30 to determine the relative blockade current as a function of the peptide location within the nanopore (Fig. 2f). The blockade current reaches the lowest values (0.17) when the peptide passes through either constriction (steric barrier) of the nanopore and is considerably higher (0.34) within the constant-potential segment of the stem. To identify the sensing volume of aerolysin, we used conformations of the RR7 peptide to computationally reconstruct the relative current blockade traces for shorter arginine peptides, RR6, RR5 and RR4, and compare the results to the experimentally determined values24. Averaging the relative current blockades over the 24 Å segment of the aerolysin stem (denoted as sensing region in Fig. 2d, f and h) yielded the best agreement with experiment (Fig. 2g). To verify that single amino acid difference of the ionic current are produced via the same mechanism, we computationally replaced the trailing arginine residue of the RR7 peptide with glycine (G), alanine (A), threonine (T) and histidine (H) and repeated SEM calculation for the ensemble of mutated structures (Fig. 2h). The blockade currents rank in the same order as in our experiment, and are in quantitative accord when averaged over the sensing region of the nanopore (Fig. 2i). Similar results were obtained when applying the same analysis to a replicate SMD run (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results indicate the steric, volume exclusion nature of the amino acid-specific ionic current blockades in aerolysin, similar to the mechanism previously established for DNA nucleotide-specific blockades in MspA31. We experimentally confirmed the volume exclusion mechanism by measuring blockade currents of VXR7 peptides (where X was K, H, E, D and R, Supplementary Fig. 6) and finding the VXR7 blockades to be linear combinations of VR7 and XR7 blockades upon subtracting the contribution of the extra RR7 fragment (Supplementary Note 1).

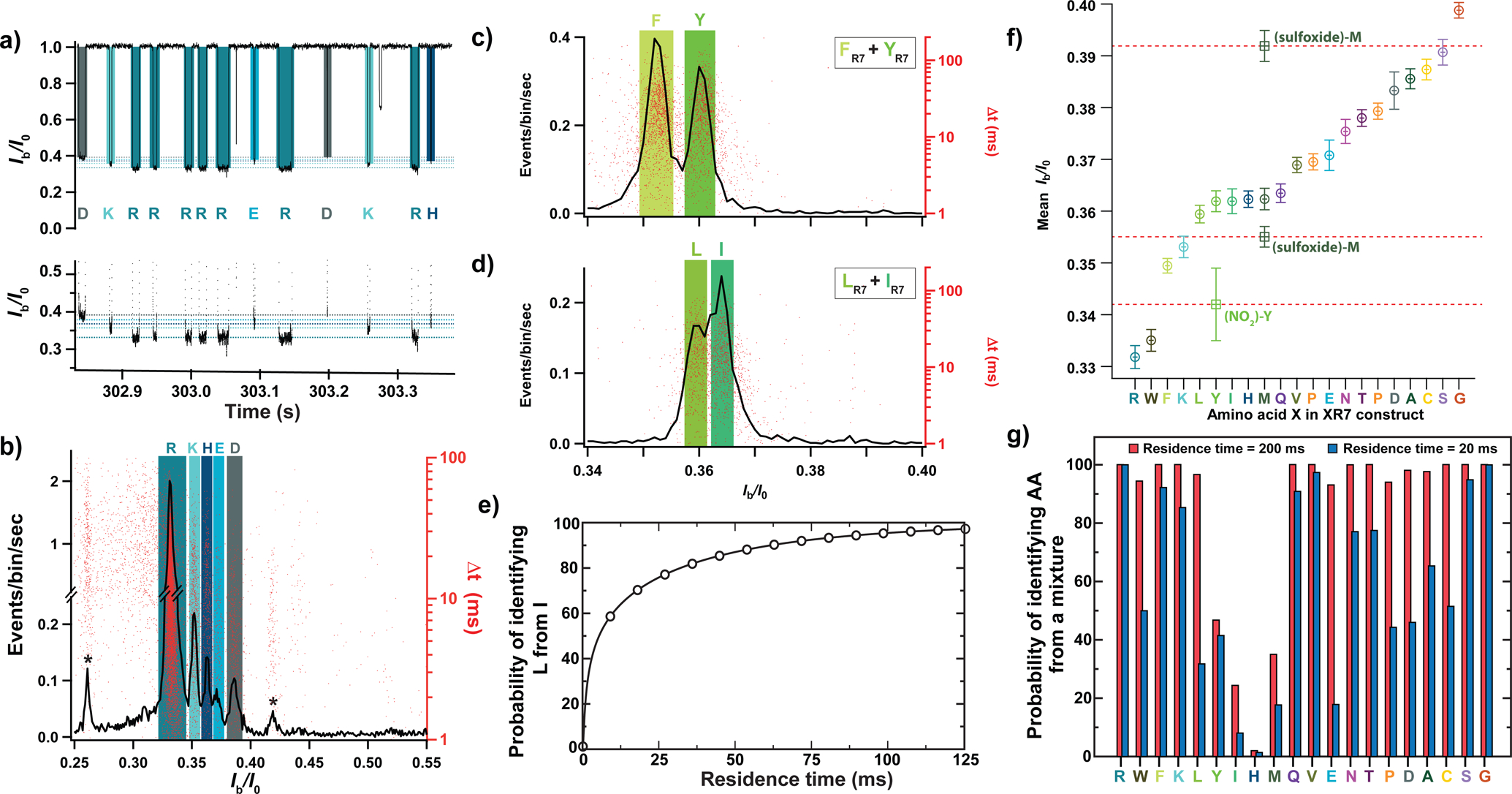

Nanopore experiments carried out using equimolar mixtures of XR7 peptides show that our experimental approach can discriminate individual peptides species from a mixture. Figure 3a shows a fragment of a typical ionic current recording obtained for an equimolar mixture of KR7, HR7, DR7, ER7, and RR7 peptides, where individual transport events can be assigned to individual peptide species. The histogram of the relative residual current and the scatter plot of blockade duration (Fig. 3b) reveal well-separated peaks matching the location of Ib/I0 peaks observed in nanopore experiments carried out using individual peptide species (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Similar well-resolved distributions were obtained when equimolar amounts of KR7, HR7, DR7, ER7, and RR7 peptides were successively added to the cis-compartment solution (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Discernible distributions were also observed for the mixture of XR7 peptides differing only by one hydroxyl group, phenylalanine-R7 (F) and tyrosine-R7 (Y) (Fig. 3c), and for the mixture of structural isomers, leucine-R7 (L) and isoleucine-R7 (I) (Fig. 3d). Successive addition experiments (Supplementary Fig. 8) provided further evidence for the distinguishability of the mixtures. The ability to decipher between amino acids of same molar mass, such as L and I, or between amino acids of very similar chemical structure, such as F and Y, suggests that detecting other subtle changes such as post-translational modifications may be feasible with our set-up.

Figure 3: Discerning amino acids from a mixture.

(a) Fragment of a typical current recording from a nanopore experiment where equimolar amounts of RR7, KR7, HR7, ER7, and DR7 were introduced into the cis compartment solution. The bottom graph shows a zoomed-in view of the top graph. (b) Histogram of Ib/I0 values (black line, left axis) and the scatter plot of the blockade duration (red dots, right axis) for an equimolar mixture of RR7, KR7, HR7, ER7, and DR7 (n = 19641 events). (c,d) Histogram of Ib/I0 values (black line, left axis) and scatter plot of blockade duration (red dots, right axis) recorded from an equimolar mixture of YR7 and FR7 (panel c, n = 7731 events) or LR7 and IR7 (panel d, n = 4489 events). Colored rectangles indicate the mean (centerline) and the standard deviation (widths) of the Ib/I0 values recorded individually for each XR7 peptide (data from Fig. 1f–j and Supplementary Fig. 7). (e) Theoretically assessed probability of identifying LR7 from an equimolar mixture of LR7 and IR7 from a single nanopore passage of specified duration. (f) Experimentally determined mean Ib/I0 value and its standard deviation for all twenty XR7 peptides arranged in ascending order (circles) (n = 34025 (RR7), 1328 (WR7), 6228 (FR7), 1969 (KR7), 2319 (LR7), 3411 (YR7), 5185 (IR7), 1449 (HR7), 2317 (MR7), 3822 (QR7), 5369 (VR7), 1681 (PR7), 1655 (ER7), 3165 (NR7), 2978 (TR7), 1866 (DR7), 1717 (AR7), 3311 (CR7), 8169 (SR7), 3266 (GR7), 2626 ((NO2)-YR7), 2374 ((sulfoxide)-M R7) events). Square symbols indicate Ib/I0 values for chemically modified methionine, M-(sulfoxide), and tyrosine, Y-(NO2), peptides (see Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). The mean value (respectively uncertainty) of relative residual current of each peptide was obtained as the mean value (respectively standard deviation) of a gaussian fit of the corresponding Ib/I0 distribution; from single independent experiments. (g) Theoretically assessed probability of identifying an individual XR7 peptide from a mixture of twenty XR7 peptides from a single nanopore measurement lasting 20 (blue) or 200 (red) ms. All experimental data were acquired in 4 M KCl, 25 mM HEPES buffer, at 7.5 pH and 20.0 ± 0.5°C, and under a −50 mV bias applied to the trans compartment.

To evaluate the prospect of using our approach for protein sequencing, we theoretically determined requirements for distinguishing amino acids from a single passage measurement; see Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed description of the model. We assume that the residence time of individual peptides within the sensing volume of the aerolysin nanopore, can be increased by modifying the trans-side constriction of the aerolysin stem and that such modifications do not affect the mean, amino acid-specific blockade values, 〈Ib/I0〉X, the ionic current noise level and the peptide capture rate. For an equimolar mixture of L and I peptides, a translocation event can be identified as an L type if its 〈Ib/I0〉 value is closer to 〈Ib/I0〉L than to 〈Ib/I0〉I. The likelihood of identifying the L peptide correctly depends on the separation between 〈Ib/I0〉L and 〈Ib/I0〉I and on the deviation of the translocation mean blockade, 〈Ib/I0〉, from the true mean, 〈Ib/I0〉L, a deviation that decreases as an inverse square root of the residence time. Using this model, we can plot the likelihood of correct identification of L peptides from the L/I mixture as a function of the residence time, Fig. 3e, finding a 99% correct identification for peptide residence time of 125 ms. Note that this residence time greatly exceeds the theoretical minimum of 5 ms (Supplementary Fig. 9) obtained assuming the ion counting error being the only noise source. For the equimolar mixture of F from Y peptides, the model predicts a 99.5% identification probability from a single, 20 ms passage, a typical translocation time observed in our experiments (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Using the experimentally determined 〈Ib/I0〉X values for the twenty peptides species (Fig. 3f), we can estimate the likelihood of correctly identifying single passage of an individual peptide in the presence of all twenty peptide species (Fig. 3g). For the peptide residence time of 20 ms, six of out twenty peptides can be identified with a probability exceeding 90%. Increasing the residence time to 200 ms, one can identify 16 peptide species with a probably of 90% or higher. Assuming that a peptide’s escape through the trans barrier of aerolysin is a thermally activated process, increasing the residence time by 10 fold would require increasing the height of the barrier by only 2.3 kBT. Among all peptides, distinguishing I, H and M peptides is the most challenging because of overlapping Ib/I0 distributions (Fig. 3f).

To show that our amino acid identification strategy can be further improved, we chemically modified the M and Y amino acids, which shifted their 〈Ib/I0〉 values outside the 0.335–0.35 range, Fig. 3f and Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11. This chemical modification approach can be generalized to other difficult to distinguish amino acids through selective chemical reactions that have already been developed32, 33 and used as a part of the sample preparation procedure. These data also show that our nanopore sensing method can easily distinguish several modifications of the same amino acid (Supplementary Fig. 10) and used for identification of post-translational modifications. Finally, we show that peptide distinguishability can be improved by optimizing both the apparatus and recording conditions, which in the case of an I and L mixture, reducing the error of peptide identification from > 30 to < 5%, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 12–15.

In summary, we have demonstrated a strategy for the detection of all twenty proteinogenic amino acids using a wild-type aerolysin nanopore. Almong twenty amino acids, our approach could identify unmodified R, W, F, K, L, N, T, P, D, A, C, S and G amino acids and, upon chemical modification, Y and M amino acids. The data we report here could underpin advances beyond protein fingerprinting6, 11 and nanopore mass spectrometry20, and pave the way towards residue-by-residue protein sequencing, including detection and differentiation of residue-specific post-translational modifications. We attribute the exquisite sensitivity of our system to a single-molecule trap in the aerolysin nanopore that fully confines the amino acid ligated to a polycationic carrier within the sensing volume of aerolysin nanopore. The resulting prolonged capture of carrier-ligated individual amino acids differentiates our approach from other strategies in which a peptide chain is continuously pulled through a nanopore1, 2, 5, 20, that expose peptide fragments20 or protein regions1, 2, 5 to a sensing region for only brief periods of time.

We envision that our approach could be used for parallel protein sequencing. In the first step a terminal amino acid would be cleaved off from multiple copies of a target protein10, then in a second step terminal amino acides would be ligated to a freshly introduced carrier peptide and subjected to nanopore analyses; many such reactions could be performed in parallel in electrically isolated volumes in which synchronous reagent exchange cycles take place. As an alternative to chemical (Edman, degradation) sequential cleavage could be achieved using a protein digestion complex, such as ClpXP, which has already been shown to work in tandem with a nanopore1, 12.

Using our amino acid detector for single molecule protein sequencing would require cleavage and ligation of individual amino acids to a polypeptide carrier and subsequent capture of that ligation product by a nanopore. It might be beneficial to tether a protein digestion enzyme to the aerolysin nanopore and to carry out the ligation step first, to increase the probability of nanopore capture of the cleaved product.

Online Methods

Nanopore recordings

Single-channel current recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in the whole-cell mode with a CV-203BU headstage. The signal was filtered using an internal 4-pole Bessel filter at a cut-off frequency of 5 kHz. Data were digitized using a DigiData 1440A AD-converter (Molecular Devices) at a sampling rate of 250 kHz. Data acquisition was controlled using Clampex 10.2 software (Molecular Devices). The temperature of the experiments was set up using a Peltier device controlled by a bipolar temperature controller (CL-100, Warner Instruments) and coupled to a water circulation (LCS-1, Warner Instruments).

Membrane and nanopore formation

Single-channel experiments were carried out using a classical vertical lipid bilayer setup (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) including two chambers (cis and trans) connected by a 150 μm-diameter aperture. The planar lipid bilayer membrane was formed by painting and thinning a film of 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) dissolved in decane (10 mg/ml) over the aperture connecting the two chambers. Two Ag/AgCl electrodes were used to apply a transmembrane voltage and to measure the transmembrane ionic current. The cis-chamber was at voltage ground. All experiments were conducted in aqueous 4 M KCl solution buffered with HEPES 25 mM and set to pH=7,5. The temperature was set to 20.0±0.5°C for all the experiments. Recombinant wild-type pro-aerolysin was produced as described previously24. Pro-aerolysin was digested by trypsin (5:3 pro-aerolysin:trypsin mass ratio) for 15 minutes at room temperature to eliminate the pro-peptide sequence and form aerolysin. After membrane formation, aerolysin was added to a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml to the cis compartment. The insertion of a single aerolysin nanopore in the membrane generates a current jump of approximately −100 pA at −50 mV in our experimental conditions.

Peptide detection

For all nanopore measurements, we used high-purity (> 98%) heteropeptides (NH2-R-R-R-R-R-R-R-X-COOH, named XR7) (Clinisciences, Nanterre, France) composed of seven arginine amino acids (R7) and an eighth amino acid (X) that varied among the 20 proteinogenic amino acids. Chemically modified peptides (NO2)-YR7, (SO3H2)-YR7, (P)-YR7 and (sulfoxide)-MR7 were provided from Clinisciences, Nanterre, France. Prior to nanopore measurements, peptides were dissolved in an aqueous 5 mM HEPES pH=7,5 buffer. All nanopore experiments were performed at constant −50 mV voltage applied to the trans compartment, unless stated otherwise. In the case of the individual XR7 peptide experiments, peptides were added to the cis chamber to the final concentration of 1 μM, unless otherwise stated. In the case of peptide mixture experiments, peptides were simultaneously added to the cis chamber to have 1 μM final concentration of each peptide. In the case of the successive addition experiments, peptides were successively added to the cis chamber to the final concentration of 1 μM. In the case of the CR7 reduction experiment, dithiothreitol (Invitrogen life technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) was added to the cis chamber to 25 mM final concentration in presence of CR7 peptides upon which ionic current recordings were performed continuously. In every case, the peptide addition was followed by a 20 times ≈ 100 μl mixing of the volume of the cis-chamber before data acquisition.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Igor Pro 6.12A software (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR, USA) and in-house developed procedures. Typically, at least 1000 blockade events were collected in each ionic current measurement. Peptide-induced current blockades were detected using a two-thresholds method24. A first threshold, th1 = I0 - 4σ, was used to identify a possible blockade event. Here, I0 and σ are, respectively, the mean value and the standard deviation of the open pore current obtained from a Gaussian fit to the open pore current distribution. Thus, a possible blockade event always begins when the pore current decreases below th1 and ends when the pore current first increases above th1. Using this first threshold eliminates the overwhelming part of the open pore current fluctuations. If the mean value of the current blockade during the event, Ib, falls below the second threshold, th2 = I0 - 5σ, then this event is considered as a peptide-induced blockade event. Histograms of the relative residual current, Ib/I0, were constructed using bins of 0,001 width. The number of blockades per second per bin corresponds to the ratio of the Ib/I0 histogram values to the total duration of the corresponding current recording. The mean relative residual current blockade 〈Ib/I0〉X of each peptide was obtained as the mean value of a Gaussian fit to the corresponding Ib/I0 distribution. The uncertainty of 〈Ib/I0〉X determination was expressed using the standard deviation σX of the Gaussian fit. The current blockades corresponding to each peptide were identified as the current blockades with Ib/I0 values located within the 〈Ib/I0〉X −3σX to 〈Ib/I0〉X +3σX range. From the current blockades corresponding to each peptide, the mean blockade duration were calculated for each peptide. The mean blockade duration corresponds to the arithmetic mean of blockade durations.

General MD Methods

All MD simulations were carried out using NAMD234, a 2 fs integration timestep, periodic boundary conditions and CHARMM3635 force-field. All covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms were restrained using the SETTLE36 and RATTLE37 algorithms for water and proteins, respectively. Particle-Mesh Ewald38 method was used to evaluate long range electrostatic interactions over a 1Å-spaced grid. Constant pressure simulations were realized using a Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston pressure control39. Temperature was maintained at a constant value by coupling all non-hydrogen atoms to a Langevin thermostat40. The van der Waals forces were calculated using a cutoff of 12 Å and a switching distance of 10 Å. Multiple time stepping41 was used to calculate local interactions at every time step and full electrostatics every second time step.

All Atom Model of Aerolysin

The initial structural model of aerolysin was taken from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 5JZT)29. After aligning the protein’s primary principal axis with the z axis, the protein structure was merged with a 19.2 nm × 19.2 nm patch of pre-equilibrated diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (DPhPC) lipid bilayer. The bilayer was placed parallel to the x-y plane and having the CoM of the bilayer the same z coordinate as that of residues 230–267 (stem) of aerolysin. All DPhPC molecules that overlapped with the atoms of aerolysin were removed. The protein-lipid system was submerged in a rectangular volume of TIP3P42 water molecules. At first, 42 K+ ions were added to neutralize the net negative charge of the aerolysin pore. Following that, 1679 K+ and 1679 Cl− ions were added to make a 1 M KCl solution, by replacing an equivalent number of water molecules. We chose to conduct our all-atom MD simulations at 1 M KCl concentration, as we previously found the molecular force field to exhibit ion-pairing artifacts at 4 M KCl43. The final system measured 19.2 nm × 19.2 nm × 14.5 nm and contained 447, 121 atoms. After 2000 steps of energy minimization, the system was heated to 293 K and then equilibrated in the constant number of atoms (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) ensemble for 0.5 ns having all protein’s non-hydrogen atoms restrained to the initial coordinates while forcing water molecules out of the membrane-protein interface using a custom tclforces script. The system was then equilibrated for 10 ns without any restraints. All equilibration simulations were carried out keeping the area of the lipid bilayer constant while allowing the system’s dimensions to change along the z axis to realize the target pressure. During the equilibration, the hydrophobic lipid tails formed a waterless contact with the stem of aerolysin whereas the headgroups of the top leaflet moved towards and formed contacts with the bottom of the aerolysin’s vestibule, see Supplementary Video 1. The root mean squared deviation of the protein’s coordinates saturated at 3.5 Å, Supplementary Fig. 3c. The final equilibrated structure was used for all subsequent constant volume simulations using, as system’s dimensions, the average values from the last 9 ns of the equilibration run. The system was simulated under a constant electric field E applied normal to the lipid bilayer to produce a transmembrane bias V = - E * Lz, where Lz was the system’s dimension along the z axis44. Each Cα atom of aerolysin was harmonically (kspring = 69.5 pN/nm) restrained to maintain the same coordinate as in the last frame of the equilibration trajectory.

Simulation of Relative Residual Current

An atomic model of eight-arginine peptide (RR7) was obtained using Avogadro45 and preequilibrated in a water box. The RR7 peptide was placed near the cis entrance of the aerolysin pore along the pore’s symmetry axis (see Fig. 2d). The resulting system was equilibrated for 5 ns in the NPT ensemble while harmonically restraining the Cα atoms of both aerolysin and the peptide to their initial coordinates. Following that, the peptide was pulled along the pore axis using the SMD method46, 47 while the Cα atoms of aerolysin were restrained to their equilibrated coordinates. During a 120 ns SMD run, the CoM of the peptide was coupled to a template particle via a harmonic potential (kspring = 4865 pN/nm) while the particle was pulled along the pore axis with a constant velocity of 1 Å/ns. The SMD simulation was performed in the presence of −100 mV transmembrane bias. Atomic coordinates of the RR7 peptide, of the aerolysin protein, and of the DPhPC membrane were recorded every 0.2 ns and used for subsequent calculations of the ionic current using the steric exclusion model (SEM)30. The currents were divided by the average open pore current to obtain 535 instantaneous relative residual current values. The currents were sorted in ascending order according to the CoM coordinate and averaged using a 10-Å running average window. These averaged currents are plotted in Fig. 2e & f. Each conformation of RR7 peptide was used to generate atomic structures of shorter RR peptides (RR6, RR5 and RR4) and other R7 peptide variants (GR7, HR7, AR7 and TR7). Thus, the structures of RR6, RR5 and RR4 were obtained by cutting off 1, 2 or 3 arginine residues from either end of the RR7 peptide, producing 2, 3 or 4 conformations of RR6, RR5 and RR4, respectively. The GR7, HR7, AR7 and TR7 structures were obtained by mutating the arginine residue at the trailing end of the RR7 peptide into glycine, histidine, alanine or threonine, while keeping the same backbone structure. The traces of relative residual currents for these peptide structures were calculated using the SEM method following the same protocols as for the RR7 peptide.

Low-noise ionic current recordings.

Low-noise recordings were performed on a modified Orbit16 (Nanion Technologies, Munich, Germany) set-up using MECA16 (Ionera Technologies, Freiburg, Germany) microelectrode cavity array chips with 16 cavities of diameter 50 μm. The modification consisted in disconnecting the multichannel amplifier and shortening the connection between the single channel amplifier headstage and the chip to a 1 cm unshielded wire in order to minimize stray capacitance. Lipid bilayers were formed automatically using remotely actuated spreading of diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine in octane (5 mg/ml) as described in Ref. 48. All solutions and reagents as well as the aerolysin reconstitution protocol were identical to those used on the classical bilayer set-up.

The single channel amplifier was an Axopatch 2B patch clamp amplifier operated in capacitive feedback mode at 50 mV/pA or 100 mV/pA gain. Total capacitance was carefully balanced to minimize noise from the voltage command input. The amplifier’s internal analog 4-pole Bessel filter was set to a cut-off frequency of 10 kHz. Command voltage was set and current was digitized at 1 MHz sampling rate using a National Instruments (Austin, TX) NI PCI-6251 16-bit ADC interface controlled by GePulse software (Michael Pusch, University of Genoa, Italy). Digital current amplitude resolution was 6.10 or 3.05 fA/bit. Gepulse data files were exported into Axon Binary Format (abf1) and event detection was perfomed using using a Labview executable (DetectIvent) written by Norbert Ankri, University of the Mediterranean, Marseille, France49. Briefly, the algorithm creates two versions of the original data traces where the point to point changes in current value are added over time for as long as they are negative or positive – i.e. as long as the signal changes monotonously in one direction – but which is set to zero once the difference reverses sign. Effectively, this creates two signals that rise as a peak whenever there is a change in current level in the original trace. Thresholding is simultaneously performed on both derived signals and the first and last points of a peak exceeding a given threshold are defined as the onset and end, respectively, of a transition. All data points between the end of a suprathreshold transition and the next onset are averaged to obtain the mean current value of a level.

In the next step of data treatment, the point averages of all levels are converted into relative current levels by defining an absolute current threshold above which all levels are considered to be open pore current levels. A running average baseline of 10 open pore current levels is used as the denominator to calculate the relative residual current (Ib/I0), thereby also removing the influence of slow current drifts (< 0.1 pA /min) due to temperature fluctuations, evaporation or slight electrode polarization during long recordings (typically ≥ 10 minutes). Besides the average I/I0 values, the baseline, the date of onset, the number of points used in calculating the average, as well as the variance of I/I0 values for each level are recorded in a text file. This text file is further processed using a threshold of I/I0 = 0.9 to detect resistive pulses (r.p.s) which are made up of all levels between a transition to a blocked state (I/I0< 0.9) and the first subsequent transition back to the open state (Ib/I0 > 0.9). This routine also enables the definition of a range of Ib/I0 values outside of which levels are not taken into account in computing the r.p.’s mean Ib value, thus preventing short visits to deep-blocked states from affecting the point average of the r.p. (see Supplementary Fig. 15).

Statistics and reproducibility.

All experimental data were replicated multiple times [AU state a range here eg. 5–20x] independently.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR (ANR-17-CE09-0032-01 to A.O and F.P; ANR-17-CE09-0044-02 to P.M, J.P and A.O) and by the Direction Générale de l’Armement (the French Defence Procurement Agency, n° 2017 60 0042 to A.O. and H.O) and by the Region Ile-de-France in the framework of DIM ResPore (n° 2017-05 to A.O., H.O, P.M. and J.P). K.S. and A.A. were supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-HG007406 and P41-GM104601 and the National Science Foundation grant PHY-1430124. K.S. and A.A. gladly acknowledge supercomputer time provided through XSEDE Allocation Grant MCA05S028 and the Blue Waters Sustained Petascale Computer System at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. T.E. is a fellow in the International Research Training Group (IRTG) 1642 ”Soft Matter” of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). We thank F. Gisou van der Goot (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing the pET22b-proAL plasmid containing the pro-aerolysin sequence. We thank Manuela Pastoriza-Gallego for producing recombinant wild-type pro-aerolysin.

Footnotes

Code availability.

Experimental data acquisition was controlled using Clampex 10.2 software (Molecular Devices). Experimental data were analyzed using Igor Pro 6.12A software (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR, USA) and in-house developed procedures, which are available at https://gitlab.engr.illinois.edu/tbgl/tools/blockade-detection. All MD simulation trajectories were generated using NAMD2 software package, the source code of which is available at: www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd/. Ionic current analysis of the MD trajectories was carried out using a Steric Exclusion Model (SEM), which is described in full detail in Reference 30. A python implementation of the SEM model is available at https://gitlab.engr.illinois.edu/tbgl/tools/sem.

Data availability.

Experimental raw data, all input files necessary to rerun the MD simulations, the simulation trajectories and raw SEM current data are available at Illinois Data Bank, https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-4905767_V1.

Competing financial interest

AU include any patents pending as a result of this work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A.O, J.P and P.M are co-founders of DreamPore S.A.S. and F.P. is the head of research development of DreamPore S.A.S. J.C.B is cofounder of Ionera Technologies GmbH, Freiburg, Germany and of Nanion Technologies GmbH, Munich, Germany.

References

- [1].Nivala J, Marks DB & Akeson M Unfoldase-mediated protein translocation through an α-hemolysin nanopore. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 247–250 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rodriguez-Larrea D & Bayley H Multistep protein unfolding during nanopore translocation. Nat. Nanotech 8, 288–295 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhao Y et al. Single-molecule spectroscopy of amino acids and peptides by recognition tunnelling. Nat. Nanotech 9, 466–473 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ohshiro T et al. Detection of post-translational modifications in single peptides using electron tunnelling currents. Nat. Nanotech 9, 835–840 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kennedy E, Dong Z, Tennant C & Timp G Reading the primary structure of a protein with 0.07 nm3 resolution using a subnanometre-diameter pore. Nat. Nanotech 11, 968–976 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Restrepo-Perez L, Joo C & Dekker C Paving the way to single-molecule protein sequencing. Nat. Nanotech 13, 786–796 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goodwin S, McPherson JD & McCombie WR Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet 17, 333 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Edman P A method for the determination of the amino acid sequence in peptides. Arch. Biochem 22, 475–476 (1949). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Steen H & Mann M The abc’s (and xyz’s) of peptide sequencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 5, 699 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Swaminathan J et al. Highly parallel single-molecule identification of proteins in zeptomole-scale mixtures. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 1076 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].van Ginkel J et al. Single-molecule peptide fingerprinting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, 3338–3343 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nivala J, Mulroney L, Li G, Schreiber J & Akeson M Discrimination among protein variants using an unfoldase-coupled nanopore. ACS Nano 8, 12365–12375 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wilson J, Sloman L, He Z & Aksimentiev A Nanopore sequencing: graphene nanopores for protein sequencing. Adv. Funct. Mater 26, 4829–4829 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Boersma AJ & Bayley H Continuous stochastic detection of amino acid enantiomers with a protein nanopore. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 51, 9606–9609 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Singh PR et al. Pulling peptides across nanochannels: resolving peptide binding and translocation through the hetero-oligomeric channel from Nocardia farcinica. ACS Nano 6, 10699–10707 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Asandei A, Rossini AE, Chinappi M, Park Y & Luchian T Protein nanopore based discrimination between selected neutral amino acids from polypeptides. Langmuir 33, 14451–14459 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Movileanu L Interrogating single proteins through nanopores: challenges and opportunities. Trends Biotechnol. 27, 333–341 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Howorka S & Siwy Z Nanopore analytics: sensing of single molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev 38, 2360–2384 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bush J et al. The nanopore mass spectrometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum 88, 113307 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Huang G, Voet A & Maglia G FraC nanopores with adjustable diameter identify the mass of opposite-charge peptides with 44 dalton resolution. Nat. Commun 10, 835 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Branton D et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 1146–1153 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jain M, Fiddes IT, Miga KH, Paten B & Akeson M Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nat. Methods 12, 351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manrao EA et al. Reading DNA at single-nucleotide resolution with a mutant MspA nanopore and phi29 DNA polymerase. Nat. Biotechnol 30, 349–353 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Piguet F et al. Identification of single amino acid differences in uniformly charged homopolymeric peptides with aerolysin nanopore. Nat. Commun 9, 966 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Perkins SJ Protein volumes and hydration effects: The calculations of partial specific volumes, neutron scattering matchpoints and 280-nm absorption coefficients for proteins and glycoproteins from amino acid sequences. Eur. J. Biochem 157, 169–180 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Robertson JWF et al. Single-molecule mass spectrometry in solution using a solitary nanopore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 8207–8211 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Baaken G et al. High-resolution size-discrimination of single nonionic synthetic polymers with a highly charged biological nanopore. ACS Nano 9, 6443–6449 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chavis AE et al. Single molecule nanopore spectrometry for peptide detection. ACS Sens. 2, 1319–1328 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Iacovache I et al. Cryo-EM structure of aerolysin variants reveals a novel protein fold and the pore-formation process. Nat. Commun 7, 12062 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wilson J, Sarthak K, Si W, Gao L & Aksimentiev A Rapid and accurate determination of nanopore ionic current using a steric exclusion model. ACS Sens. 4, 634–644 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bhattacharya S, Yoo J & Aksimentiev A Water mediates recognition of DNA sequence via ionic current blockade in a biological nanopore. ACS Nano 10, 4644–4651 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Spicer CD & Davis BG Selective chemical protein modification. Nat. Commun 5, 4740 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Taylor MT, Nelson JE, Suero MG & Gaunt MJ A protein functionalization platform based on selective reactions at methionine residues. Nature 562, 563 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Phillips JC et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem 26, 1781–1802 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].MacKerell AD Jr et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Miyamoto S & Kollman PA Settle: An analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem 13, 952–962 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [37].Andersen HC Rattle: A “velocity” version of the shake algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Phys 52, 24–34 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- [38].Darden T, York D & Pedersen L Particle mesh Ewald: An N log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys 98, 10089–10092 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ & Klein ML Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys 101, 4177–4189 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- [40].Brünger AT X-PLOR: version 3.1: a system for x-ray crystallography and NMR (Yale University Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tuckerman M, Berne BJ & Martyna GJ Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys 97, 1990–2001 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW & Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- [43].Comer J & Aksimentiev A Predicting the DNA sequence dependence of nanopore ion current using atomic-resolution brownian dynamics. J. Phys. Chem C 116, 3376–3393 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Aksimentiev A & Schulten K Imaging α-hemolysin with molecular dynamics: ionic conductance, osmotic permeability, and the electrostatic potential map. Biophys. J 88, 3745–3761 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hanwell MD et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminformatics 4, 17 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Isralewitz B, Izrailev S & Schulten K Binding pathway of retinal to bacterio-opsin: a prediction by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J 73, 2972–2979 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Grubmüller H, Heymann B & Tavan P Ligand binding: molecular mechanics calculation of the streptavidin-biotin rupture force. Science 271, 997–999 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].del Rio Martinez JM, Zaitseva E, Petersen S, Baaken G & Behrends JC Automated formation of lipid membrane microarrays for ionic single-molecule sensing with protein nanopores. Small 11, 119–125 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Baaken G, Ankri N, Schuler A-K, Rühe J & Behrends JC Nanopore-based single-molecule mass spectrometry on a lipid membrane microarray. ACS Nano 5, 8080–8088 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.