Abstract

Objective:

Latina breast cancer survivors (BCS) report more symptom burden and poorer health-related quality of life than non-Latina BCS. However, there are few evidence-based and culturally informed resources that are easily accessible to this population. This study aimed to establish the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the My Guide and My Health smartphone applications among Latina BCS. Both applications are culturally informed and contain evidence-based information for reducing symptom burden and improving health-related quality of life (My Guide) or healthy lifestyle promotion (My Health).

Methods:

Participants (N = 80) were randomized to use the My Guide or My Health smartphone applications for 6 weeks. Assessments occurred at baseline (T1) after the 6-week intervention (T2) and 2-week post-T2 (T3). Outcomes were participant recruitment and retention rates, patient-reported satisfaction, and validated measures of symptom burden and health-related quality of life.

Results:

Recruitment was acceptable (79%), retention was excellent (>90%), and over 90% of participants were satisfied with their application. On average, participants in both conditions used the applications for more than 1 hour per week. Symptom burden declined from T1 to T2 across both conditions, but this decline was not maintained at T3. Breast cancer well-being improved from T1 to T2 across both conditions and was maintained at T3.

Conclusions:

Latina BCS who used the My Guide and My Health applications reported temporary decreases in symptom burden and improved breast cancer well-being over time, though there were no differential effects between conditions. Findings suggest that technology may facilitate Latina BCS engagement in care after breast cancer treatment.

Keywords: breast cancer, eHealth, health-related quality of life, psychosocial intervention, symptom burden

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among Hispanic/Latina women (referred to here as Latinas). It accounts for almost 30% of Latina cancer diagnoses and is the leading cause of Latina cancer-related deaths.1 Compared with non-Latina breast cancer survivors (BCS), Latina BCS report more symptom burden, poorer health-related quality of life, and greater cancer-related psychosocial needs,2 even after adjusting for markers of socioeconomic status.3,4 These factors, in turn, are related to poorer health outcomes and must be addressed to promote optimal long-term survivorship and health.5,6

There is ample evidence showing that psychosocial interventions can facilitate decreases in symptom burden and improvements in health-related quality of life among BCS.6–8 However, Latinas are less likely to participate in cancer research than non-Latinas9 and therefore may not be benefiting from the available resources. Latinas face unique challenges to participating in cancer research including competing time demands, mistrust of medical research, lower socioeconomic status contributing to less access to health care, and lack of Spanish-language resources.10,11

In order to meet the greater needs of Latina BCS, there is a critical need to develop resources tailored to this population that address the known barriers to research participation. Indeed, studies have shown that psychosocial interventions specifically tailored to Latina BCS are effective,12,13 but they have been limited by the delivery of the interventions in-person or over the telephone. eHealth platforms such as smartphone applications are more scalable than other modes of intervention delivery and provide an innovative opportunity among Latinas,14 who seek health information online at similar or higher rates than other racial/ethnic groups in the United States.15 However, the majority of smartphone applications that have been disseminated are not evidence-based, and almost none are culturally informed and available in Spanish.16

In order to address the greater needs and unique circumstances of Latina BCS, our team developed a smartphone application called My Guide. My Guide is a culturally informed application that contains evidence-based information for reducing symptom burden and improving health-related quality of life. In a nonrandomized longitudinal trial, we previously demonstrated that My Guide is feasible among Latina BCS, and preliminary evidence supports its efficacy for improving intervention targets such as breast cancer knowledge.17 In order to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of My Guide when compared with an attention-control condition, our team subsequently developed another application called My Health, which contains evidence-based education for promoting healthy lifestyles. In line with other brief interventions,18 we conducted a 6-week pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) with which we aimed to establish the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the My Guide smartphone application compared with My Health. Here, we describe the primary findings from the My Guide RCT. We hypothesized that both study conditions (My Guide and My Health) would be feasible to participants. In addition, we hypothesized that participants randomized to the My Guide application would report significantly greater reductions in symptom burden and improvements in health-related quality of life compared with participants randomized to the My Health attention-control application.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Participants and procedures

The institutional review board approved all study procedures (ClinicalTrial.gov/ ID ). Women with stage 0 to III breast cancer were recruited through advertisements and physician referrals from two large academic medical centers in the Chicago metropolitan area and a local community-based organization that specifically serves Latina women with breast cancer. All women were at least 21 years old and within 2 to 24 months of completing primary breast cancer treatment (with the exception of ongoing endocrine therapy). Exclusion criteria included a prior cancer diagnosis, prior treatment for a serious psychiatric disorder, current suicidal ideation, and the inability to speak and read in English or Spanish.

After providing written informed consent, participants completed a baseline assessment (T1) in which they self-reported sociodemographic information and completed a battery of psychosocial questionnaires. Participants were reassessed postintervention (T2) and 2 weeks after theT2 assessment (T3).

Participants were randomized 1:1 to use the My Guide application or the My Health attention-control application and were provided training for using their assigned application. Participants were given the option to use their own smartphone or borrow a study-appointed smartphone for the duration of the study. Seven out of 80 women (9%) borrowed a study-appointed phone. All participants were encouraged to use the application for 2 hours each week over the course of the 6-week intervention.

This study included a telecoaching protocol adapted from a model of supportive accountability to promote optimal adherence to using the applications.19 The telecoaching calls were brief (15–20 minutes) and did not include provision of intervention content. Participants across both conditions received telecoaching calls before weeks one, two, and six of the intervention. For the remaining weeks (3–5), a stepped-care approach informed the need for additional telecoaching calls; though participants were encouraged to use the application for 2 hours per week, a threshold of 90 minutes was used to determine the need for a telecoaching call; that is, participants who used their assigned application for less than 90 minutes in a given week received a telecoaching call, whereas participants who used their application for 90 minutes or more received a reinforcing text message. Bilingual telecoaches were trained in motivational interviewing, goal setting, and sensitivity related to Latina BCS. All calls were audio recorded and reviewed with a licensed clinical psychologist during weekly supervision to ensure fidelity to the telecoaching protocol. Additional information about the telecoaching protocol is detailed elsewhere.20

2.2 |. Study applications

The My Guide and My Health smartphone applications were developed by the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies (CBITs) at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Details related to CBITs and the security measures taken to protect participants’ data are published elsewhere.20 The content of the My Guide and My Health smartphone applications was developed in collaboration with a community partner (Latina Breast Cancer Association) and culturally informed by Latina cultural values and beliefs (eg, external locus of control, familism, fatalism, and Machismo/Marianismo).21,22 All images were selected to reflect the diversity of Latina women. Both applications were available in English and Spanish and provided to participants in their preferred language. To address concerns related to low literacy, each application’s content was also available via audio and video recordings embedded throughout the applications.

2.2.1 |. My Guide

The My Guide intervention condition was designed to reduce symptom burden and improve health-related quality of life among Latina BCS. The content was developed based on prior research of eHealth interventions, models of stress and coping,23–25 and psychosocial adaptation to breast cancer;26,27 as well research indicating stress management, cancer knowledge, enhanced communication, and social support may reduce symptom burden and improve health-related quality of life among Latina BCS.21,27–29 The content focused on efficacy for coping with late effects of cancer treatments, adherence to endocrine therapies, psychosocial adaptation during cancer survivorship, stress management, cancer-related knowledge, and optimizing social support. The My Guide content was evaluated and refined using a mixed-methods pilot study, which also demonstrated preliminary feasibility of the study procedures.17

2.2.2 |. My Health

The My Health active-control condition was designed to promote optimal health and well-being through content focused on recommendations for nutrition, physical activity, prevention of chronic illnesses, and other healthy lifestyle behaviors. The health promotion information was based on similar active-control conditions in studies of psychosocial interventions among cancer survivors.30

2.3 |. Measures

All measures were made available to study participants in English or Spanish.

2.3.1 |. Sociodemographic and cancer-specific characteristics

Participants self-reported their age, Latina ancestry, country of origin, language preference, highest educational attainment, annual household income, employment status, and marital status. Participants also self-reported their cancer-specific characteristics including their stage of disease and type of treatment(s) received (eg, chemotherapy and radiation therapy), which were verified by medical chart review.

2.3.2 |. Feasibility

Consistent with Bowen et al31 and based on our prior work and published studies among racial/ethnic minority involvement in clinical trials,30,32,33 a 70% recruitment rate and an 80% retention rate were deemed acceptable. In addition, we tracked and averaged participants’ usage of the applications across the 6-week intervention period. Based on a one-arm pilot study of the My Guide intervention,17 average usage of at least 90 minutes per week was deemed acceptable.

2.3.3 |. Acceptability

As part of the T2 assessment, participants completed an exit survey assessing study satisfaction and intervention usefulness. They were asked to rate their agreement with statements on a scale from 0 (disagree) to 4 (agree), and scores above neutral (2) were considered acceptable. This exit survey has been used in a previous intervention trial.30,34

2.3.4 |. Breast cancer symptom burden

The 25-item Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) symptom questionnaire assessed breast cancer-related symptoms during the past 4 weeks (eg, hot flashes and vaginal dryness).35 Respondents indicated how bothered they were by each symptom on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Items were summed such that higher scores indicate more breast cancer symptom burden. Cronbach alphas for the scale were acceptable and ranged from.91 to.92.

2.3.5 |. Health-related quality of life

The 36-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (FACT-B) assessed five domains in the context of breast cancer over the past week: breast cancer well-being (eg, “I am bothered by hair loss” [reverse]), physical well-being (eg, “I have nausea” [reverse]), social/family well-being (eg, “I feel close to my friends”), emotional well-being (eg, “I feel sad” [reverse]), and functional well-being (eg, “I am sleeping well”).36,37 Respondents indicated their agreement with statements on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Items were summed such that higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life in each domain. Cronbach alphas for the FACT-B sub-scales were acceptable and ranged from 0.71 to 0.92.

2.4 |. Statistical analyses

We projected that with 60 participants retained at T3 and a.05 alpha level, we would have a power of.95 to detect large intervention effects on the primary outcomes. We screened our primary outcome measures for normality and Winsorized outliers greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean.38 We calculated means, standard deviations, frequencies, t tests, and chi-squared analyses to characterize the sample.

We conducted linear mixed effects modeling to assess differences between study conditions for changes over time in breast cancer symptom burden and health-related quality of life domains (ie, breast cancer, physical, emotional, social, and functional well-being). All models controlled for language preference, education, and whether the participant had an average weekly application usage of at least 90 minutes. Linear mixed effects modeling accounts for an individual’s trajectory of scores and controls for correlations between repeated assessments. All data available were used to estimate models, so that participants were included at each time point for which they provided data (as opposed to listwise deletion). Six models were assessed with breast cancer symptom burden, breast cancer well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being, social well-being, and functional well-being as outcomes, respectively. In each model, we assessed the effects of time, condition (My Guide vs My Health), and the interaction of time and condition on the outcome. Models with no significant interaction of time and condition were respecified without the interaction term to evaluate the main effects of time and condition.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Sample characteristics

See Table 1 for descriptive information. In total, 80 women were enrolled and randomized. However, two participants were withdrawn because of technical issues and not included in the study analyses (one participant from each condition), and thus, 78 participants were analyzed. On average, women were 52.54 years old (SD = 11.36). Most women were born outside the United States (71%) with Mexican ancestry (64%) and preferred to communicate in Spanish (64%). The majority of participants were married or partnered (64%) with a high school education or less (54%) and an annual household income of less than $25 000 (53%). Most participants had stage II disease (41%) and had received chemotherapy (58%) and/or radiation therapy (71%). Participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics did not differ between groups (all Ps > .05).

TABLE 1.

Sample sociodemographic and cancer‐related characteristics

| Full Sample (N = 78) | My Guide (n = 39) | My Health (n = 39) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age; M (SD) | 52.54 (11.36) | 53.52 (11.25) | 51.55 (11.53) |

| Born in United States; n (%) | 23 (30) | 14 (36) | 9 (23) |

| Spanish-language preference; n (%) | 50 (64) | 25 (64) | 25 (64) |

| Mexican ancestry; n (%) | 50 (64) | 25 (64) | 25 (64) |

| Married or partnered; n (%) | 50 (64) | 23 (59) | 27 (69) |

| High school education or less; n (%) | 42 (54) | 23 (59) | 19 (49) |

| Annual household income < $25 000; n (%) | 41 (53) | 23 (59) | 18 (46) |

| Employed; n (%) | 34 (44) | 17 (44) | 17 (44) |

| Stage of disease; n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) |

| I | 28 (36) | 14 (36) | 14 (36) |

| II | 32 (41) | 16 (41) | 16 (41) |

| III | 11 (14) | 5 (13) | 6 (15) |

| Did not report | 4 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

| Received endocrine therapy | 61 (78) | 30 (77) | 31 (80) |

| Received chemotherapy; n (%) | 45 (58) | 19 (49) | 26 (67) |

| Received radiation therapy; n (%) | 55 (71) | 28 (72) | 27 (69) |

Note. Though 80 women were enrolled and randomized, two women were withdrawn because of technical issues and excluded from analyses.

Abbreviations: M, mean; n, frequency; SD, standard deviation.

3.2 |. Feasibility

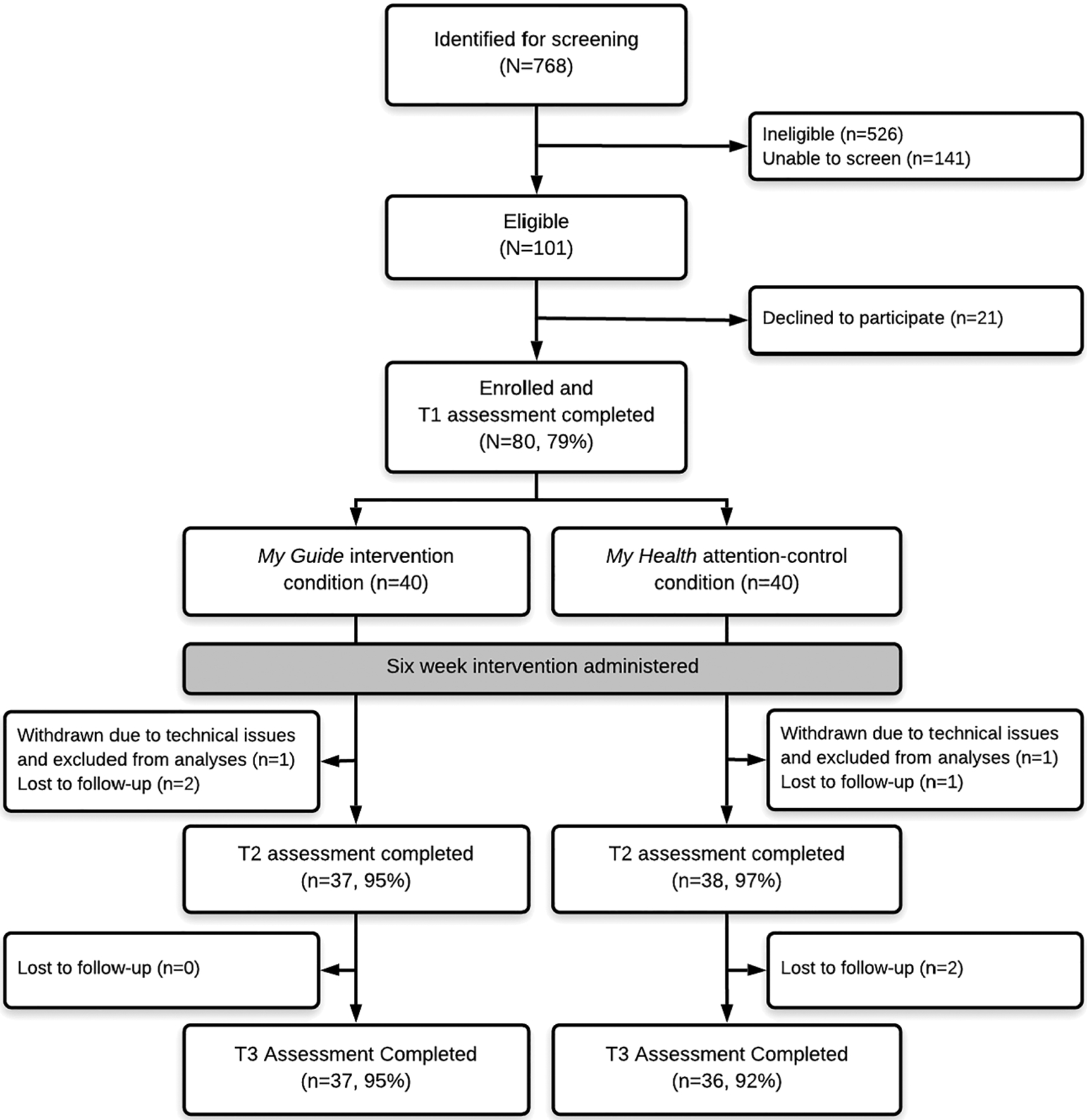

See Figure 1 for study flow and retention. Study recruitment was acceptable (79%), and retention was excellent (>90%) and did not differ across conditions at T2 (χ21 = 0.35, P = .556) or T3 (χ21 = 0.21, P = .644). Average time using the applications each week (minutes) did not differ between the My Guide (M = 86.58, SD = 66.08) and My Health conditions (M = 72.80, SD = 62.57; t76 = −0.95, P = .347) and exceeded 1 hour per week across both conditions. The proportion of participants who met the threshold of using their assigned application for at least 90 minutes per week did not differ between the My Guide (n = 18, 46.2%) and My Health conditions (n = 13, 33.3%; χ21 = 1.34, P = .247). The average number of telecoaching calls did not differ between the My Guide (M = 3.72 calls, SD = 1.26) and My Health conditions (M = 4.10 calls, SD = 1.12; t76 = 1.43, P = .157). Of participants who completed theT2 assessment, 97% of My Guide participants and 92% of My Health participants reported satisfaction with their assigned application (agree or somewhat agree; χ24 = 5.41, P = .144). Further, 100% of My Guide participants and 95% of My Health participants (all but one) would recommend their assigned application to another woman with breast cancer (χ21 = 2.00, P = .157). Finally, 92% of My Guide participants and 84% of My Health participants reported that they would like to continue using the application (agree or somewhat agree; χ24 = 4.59, P = .332).

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram with study flow and retention by study condition

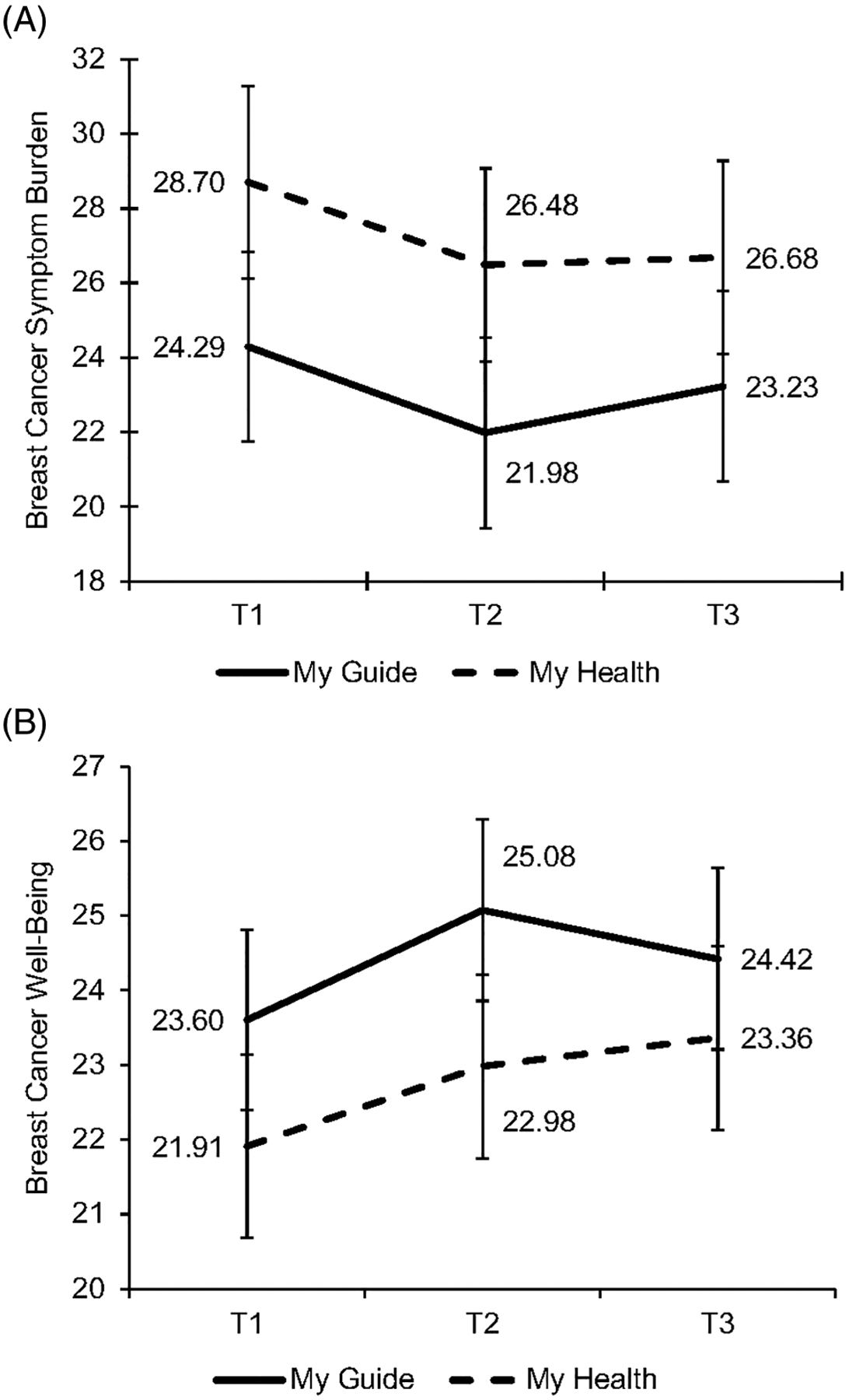

3.3 |. Breast cancer symptom burden

Table 2 displays the unadjusted means and standard deviations of breast cancer symptom burden within each condition across time. There was no interaction of time and condition on breast cancer symptom burden ( F 2,143 = 0.21, P = .808). However, there was a significant main effect of time ( F 2,145 = 3.53, P = .032) such that breast cancer symptom burden declined from T1 to T2 in both study conditions (b = −2.27, SE = 0.87, P = .010, Cohen d = 0.08), though this decline was not maintained at T3 (b = −1.54, SE = 0.88, P = .082; Figure 2A). There was no main effect of condition on breast cancer symptom burden ( F 1,72 = 1.39, P = .242).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted means and standard deviations of study outcomes by group across time

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My Guide (n = 39) | My Health (n = 39) | My Guide (n = 37) | My Health (n = 38) | My Guide (n = 37) | My Health (n = 36) | |

| Breast cancer symptom burden; M (SD) | 24.64 (15.65) | 27.92 (18.76) | 22.22 (11.98) | 25.05 (19.35) | 23.46 (12.33) | 26.39 (18.52) |

| Breast cancer well-being; M (SD) | 23.49 (6.42) | 22.08 (8.19) | 25.17 (5.51) | 23.36 (8.75) | 24.51 (5.90) | 23.53 (8.76) |

| Physical well-being; M (SD) | 21.21 (6.64) | 20.92 (6.56) | 22.05 (5.18) | 21.32 (6.60) | 20.89 (5.31) | 20.53 (7.07) |

| Emotional well-being; M (SD) | 18.82 (5.10) | 18.95 (4.46) | 19.32 (3.80) | 18.66 (5.10) | 18.70 (3.64) | 18.31 (5.04) |

| Social well-being; M (SD) | 20.51 (6.53) | 20.89 (6.19) | 20.86 (4.83) | 22.47 (4.45) | 20.48 (5.79) | 21.84 (5.25) |

| Functional well-being; M (SD) | 20.44 (5.46) | 21.18 (4.99) | 20.68 (4.80) | 20.92 (4.52) | 19.76 (5.45) | 21.00 (6.14) |

Note. Though 80 women were enrolled and randomized, two women were withdrawn because of technical issues and excluded from analyses.

Abbreviations: M, mean; n, frequency; SD, standard deviation; T1, study baseline; T2, immediately postintervention; T3, 2‐week post‐T2.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Breast cancer symptom burden significantly declined from T1 to T2 for both My Guide and My Health after controlling for covariates; (B) breast cancer well‐being significantly improved from T1 to T2 and T3 for both My Guide and My Health after controlling for covariates

3.4 |. Health-related quality of life

Table 2 displays the unadjusted means and standard deviations of each health-related quality of life domain within each condition across time.

3.4.1 |. Breast cancer well-being

There was no interaction of time and condition on breast cancer well-being ( F 2,143 = 0.63, P = .535). However, there was a significant main effect of time ( F 2,145 = 4.63, P = .011) such that breast cancer well-being improved from T1 to T2 in both study conditions (b = 1.27, SE = 0.46, P = .006, Cohen d = 0.20), and this improvement was maintained at T3 (b = 1.13, SE = 0.46 P = .015, Cohen d = 0.17; Figure 2B). There was no main effect of condition on breast cancer well-being ( F 1,72 = 0.96, P = .330).

3.4.2 |. Physical well-being

There was no interaction of time and condition on physical well-being ( F 2,143 = 0.96, P = .387), and there were no main effects of time ( F 2,145 = 1.73, P = .181) or condition ( F 1,72 = 0.39, P = .532).

3.4.3 |. Emotional well-being

There was no interaction of time and condition on emotional well-being ( F 2,142 = 0.61, P = .546), and there were no main effects of time ( F 2,144 = 0.56, P = .572) or condition ( F 1,70 = 0.14, P = .710).

3.4.4 |. Social well-being

There was no interaction of time and condition on social well-being ( F 2,143 = 1.76, P = .175), and there were no main effects of time ( F 2,145 = 1.28, P = .282) or condition ( F 1,71 = 0.75, P = .388).

3.4.5 |. Functional well-being

There was no interaction of time and condition on functional well-being ( F 2,143 = 1.20, P = .305), and there were no main effects of time ( F 2,145 = 0.66, P = .519) or condition ( F 1,72 = 0.31, P = .582).

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study assessed the feasibility of the My Guide application and assessed the preliminary efficacy of My Guide when compared with an attention-control application called My Health. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to deliver a culturally informed intervention to Latina BCS through a smartphone application. Delivering the intervention via smartphone allowed women to guide themselves through the intervention on their own time and addressed many common barriers to research participation in this population.10,11

The study procedures were feasible, and we had excellent retention within each condition across all time points.31 In addition, both My Guide and My Health were acceptable to participants, as evidenced by high satisfaction ratings postintervention. These findings suggest that culturally informed smartphone applications, and potentially other eHealth platforms, can be used to engage Latinas in cancer research.9,14 Most women did not meet the threshold of using their assigned application for 90 minutes per week. However, women used both applications for an average of more than 1 hour per week, which is more time than a patient might expect to spend individually with an in-person counselor (typically 50-minute appointments once per week or less). It is possible that the recommended application usage was too long for most participants, and 1 hour may be more aligned with realistic usage on a weekly basis.

Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find an effect of study condition on breast cancer symptom burden or health-related quality of life over time. However, women across both conditions reported decreases in breast cancer symptom burden and improvements in breast cancer well-being (a disease-specific domain of health-related quality of life). Both conditions included content related to physical symptoms and techniques for symptom management (eg, physical activity and nutrition recommendations).30 Thus, it is possible that women in both conditions implemented behavior changes resulting in reduced breast cancer symptom burden and improved breast cancer well-being. Alternatively, the information related to side effects and physical health may have normalized the experience of symptom burden so that women were less bothered by these symptoms over time. These potential mechanisms of effectiveness should be explored in future research.

The lack of findings related to more general domains of health-related quality of life (eg, emotional well-being) could be explained by the favorable baseline levels of health-related quality of life in this sample. Participants’ mean baseline scores on the FACT measures were similar to the general population, which indicates that participants were not experiencing compromised health-related quality of life at the time of study entry. Therefore, there was potentially little room for improvement on this outcome. In fact, a recent study by Greer et al39 found that cancer patients who had the highest levels of distress at study entry benefited most from a mobile psychosocial application. It is possible that My Guide might be more beneficial for women experiencing poorer levels of health-related quality of life, and this possibility should be further explored. In addition, the length of the intervention delivery might have been suboptimal. Six weeks is shorter than other effective evidence-based psychosocial interventions, which have been between 8 and 10 weeks8,24 and may be particularly short in the absence of an intervention facilitator. Indeed, at the postintervention assessment, the vast majority of participants expressed a desire to continue using their assigned applications, suggesting that participants recognize that they may gain additional benefit by using the applications for a longer time frame. It is also possible that My Guide would be more beneficial for women in active treatment as opposed to women who have completed cancer treatment. Based on these possibilities, the study team is currently evaluating the My Guide application among Latina women in active treatment for breast cancer, and we have extended the length of intervention delivery to 3 months. This new study will allow us to determine the feasibility of the My Guide application among Latinas in active treatment and over a longer intervention time span.

This study has important strengths. All participants were Latina BCS, who are largely underrepresented in cancer research.9 Many of the study participants were Spanish speaking and immigrants, underscoring the feasibility and cultural appropriateness of these application for Latinas. The My Guide and My Health applications were available in English and Spanish, included audio accessible features, and integrated Latina cultural values throughout the content. Using a smartphone application to deliver an evidence-based intervention is innovative, particularly among Latinas,14 and we remotely tracked the participants’ usage of the applications rather than relying on self-report. Finally, the longitudinal design, robust statistical methodology, and inclusion of an attention-control condition (My Health) reflect scientific rigor.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to design a culturally informed smartphone application for Latina BCS (My Guide) and compare it with an attention-control smartphone application (My Health). The study procedures were feasible, and acceptability of the applications was high. Latina BCS in both conditions reported decreased breast cancer symptom burden and improved breast cancer well-being over time, though we did not find differential effects between study conditions and improvements in symptom burden were not sustained through the final assessment time point. Findings suggest that technology may facilitate Latina BCS engagement in care after completion of breast cancer treatment.

5.1 |. Study limitations

Most data collected were self-reported and thus vulnerable to issues of self-representation. Though the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample are noteworthy, our results may not generalize to all Latina BCS. In addition, it is possible that our findings were limited by the length of the intervention (6 weeks), and stronger associations might have emerged over a longer intervention timeframe. Future studies should carefully consider the intervention length as it relates to the hypothesized intervention effects. Finally, our sample size was relatively small (N = 78), and it is possible that stronger intervention effects may have emerged with a larger sample. Thus, the findings reported here should be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution.

5.2 |. Clinical implications

Health care providers may consider using eHealth technologies such as smartphone applications to engage Latinas in psychosocial care after breast cancer treatment. Further, policy makers may consider supporting health care legislation that includes funding allocations to support evidence-based interventions delivered through eHealth platforms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute grants U54-CA-202995, U54-CA-202997, and U54-CA-203000. Authors L.B.O. and S.H.B. were supported by the National Cancer Institute training grant T32-CA-193193. The content reported here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding information

National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Number: T32-CA-193193; National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Numbers: U54-CA-203000, U54-CA-202997 and U54-CA-202995

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available because of ethical restrictions. This is to ensure data confidentiality and to protect the privacy of the research participants who participated in this pilot study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Society AC. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2015–2017. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moadel AB, Morgan C, Dutcher J. Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):191–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGregor BA, Antoni MH. Psychological intervention and health outcomes among women treated for breast cancer: a review of stress pathways and biological mediators. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(2): 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3450–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, et al. Reduction of cancer specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1791–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22): 2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3(2):e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health 2014;104(2):e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM. Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashing K, Rosales M. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2014;23(5):507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prochaska JJ, Coughlin SS, Lyons EJ. Social media and mobile technology for cancer prevention and treatment. Am Soc Clinic Oncol Educ Book Am Soc Clinic Oncol Meet. 2017;37:128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez MH, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Patten E. Closing the Digital Divide: Latinos and Technology Adoption 2013. October 1, 2014 Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/03/07/closing-the-digital-divide-latinos-and-technology-adoption/.

- 16.Bender JL, Yue RY, To MJ, Deacken L, Jadad AR. A lot of action, but not in the right direction: systematic review and content analysis of smartphone applications for the prevention, detection, and management of cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(12):e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buscemi J, Buitrago D, Iacobelli F, et al. Feasibility of a Smartphone based pilot intervention for Hispanic breast cancer survivors: a brief report. Transl Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DA, Cary MA, Groner KH, et al. Improving physical functional status in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief cognitive behavioral intervention. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(6):1280–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanez BR, Buitrago D, Buscemi J, et al. Study design and protocol for My Guide: an e-health intervention to improve patient-centered outcomes among Hispanic breast cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;65:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nápoles-Springer A, Ortíz C, O’Brien H, Díaz-Méndez M. Developing a culturally competent peer support intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11 (4):268–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Interian A, Díaz-Martínez AM. Considerations for culturally competent cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression with Hispanic patients. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;14(1):84–97. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Person. 1987;1(3):141–169. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penedo F, Molton I, Dahn J, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(3): 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanez B, Buitrago D, Carrio M, Salas K, Reyes K, Penedo FJ. Adherence to endocrine therapies among Hispanic breast cancer survivors: aqualitative analysis. Washington D.C: Society for Behavioral Medicine; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton AL, Snider PR. Coping with a breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(1):16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graves K, Jensen R, Cañar J, et al. Through the lens of culture: quality of life among Latina breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(2):603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(3):19–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(3): 413–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanez B, McGinty HL, Mohr DC, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a technology-assisted psychosocial intervention for racially diverse men with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4407–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How We design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. Cancer. 2007;109(S2): 414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: survival and psychosocial outcome from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouchard LC, Yanez B, Dahn JR, et al. Brief report of a tablet-delivered psychosocial intervention for men with advanced prostate cancer: acceptability and efficacy by race. Transl Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT symptom scales: a measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. J Nat Canc Ins. 2005;97(6):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE, et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Med Care. 1998;36(9): 1407–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilcox RR. Some results on a Winsorized correlation coefficient. Bf J Math Stat Psychol. 1993;46(2):339–349. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greer JA, Jacobs J, Pensak N, et al. Randomized Trial of a Tailored Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Mobile Application for Anxiety in Patients with Incurable Cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(8):1111–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]