Abstract

Purpose of review

In this review we will discuss efforts and challenges in understanding and developing meaningful outcomes of critical care research, quality improvement and policy, which are patient-centered and goal concordant, rather than mortality alone. We shall discuss different aspects of what could constitute outcomes of critical illness as meaningful to the patients and other stakeholders, including families and providers.

Recent findings

Different outcome pathways after critical illness impact the patients, families and providers in multiple ways. For patients who die, it is important to consider the experience of dying. For the increasing number of survivors of critical illness, challenges of survival have surfaced. The physical, mental and social debility that survivors experience has evolved into the entity called post intensive care unit syndrome.. The importance of prehospital health state trajectory and the need for the outcome of critical care to be aligned with the patients’ goals and preferences has been increasingly recognized.

Summary

A theoretical framework is outlined to help understand the impact of critical care interventions on outcomes that are meaningful to patients, families, and health care providers.

Keywords: critical illness, patient-centered outcomes, survival, dying

INTRODUCTION

“A healthy person has a thousand wishes, a sick man has but one,” [1].

In the 1950s and 1960s, when the field of critical care was developed, the primary focus was on survival—to take an imminently dying patient, support vital organs with pharmaceutical infusions and machines, and save the patient from the throes of death. While critical care rescued many patients, its practitioners also recognized that sometimes critical care prolonged the dying process. More often, patients who survived did not return to their normal selves. In 1984, approximately 20 years after the development of critical care, an English ethicist Gordon Dunstan made a following statement regarding meaningful outcomes of critical care: “The success of intensive care is not, therefore, to be measured only by the statistics of survival as if each death is a medical failure, it is to be measured by the quality of life preserved or restored, and by the quality of dying of those in whose interest it is to die, and by the quality of human relationships involved.”[2]. Half a century later, it is hard to summarize any better what critical care is all about.

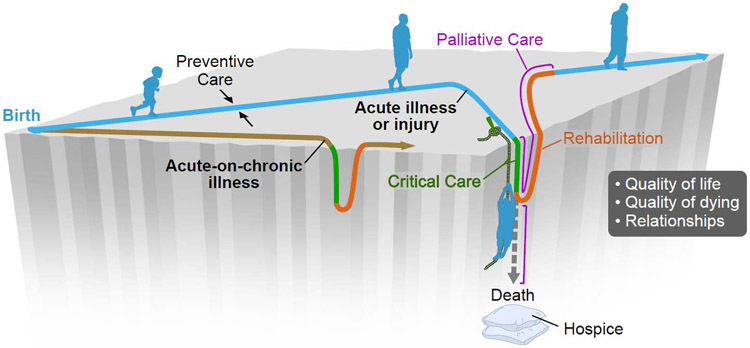

The proliferation of critical care research with the advance of electronic health records, precision medicine, and multicenter clinical trial networks is laudable but will fall far short of its promise unless outcomes of the research are assessed in a meaningful fashion. An important bias in the way we approach clinical research is our tendency to focus on what is easily measured whether they be conveniently counted outcomes such as death or association studies of molecules and disease states. It is exceedingly difficult to try to reliably incorporate into research that which is important but not so easily measured. Figure 1 illustrates the occurrence of the critical illness during the lifespan and the pathways of survival and dying after an encounter with critical illness. In this review, we will consider 1) the burden of critical illness, 2) the definitions of meaningful outcome, and 3) a brief overview of outcome measures and tools that can inform researchers, clinicians and policy makers.

Figure 1:

Critical illness during lifespan. We’re all walking on a diamond-shaped plateau in the middle of a chasm. Babies start at one tip—pretty close to the edges. Then, as children, adolescents and young adults, we live in the fat part of the diamond, pretty far away from danger. As we age, we move towards the farther tip of the diamond. Preventive medicine seeks to keep people in the middle, away from the edges. Restorative medicine tries to pull people away from the edge or throw them a rope when they slip off. Hospice medicine helps cushion the blow when people fall off for the last time. Palliative medicine works alongside all three to help people feel better despite the treatments we mete out. Some folks want to walk along the center line. They’re conservative and avoid smoking, drinking, etc. Some folks like to walk close to the edge all the time. Some folks like to walk up close to the edge from time to time, just to remind themselves of what the abyss looks like. We try to help all of these people feel better during their journeys and make some sense of the journey too. That’s the caring part.

THE BURDEN OF CRITICAL ILLNESS

One in five Americans dies in the ICU [3] and virtually all of the current generation will have an ICU encounter during life time. Figure 1 illustrates the occurrence of the critical illness during lifespan and the pathways of survival and dying after critical illness.

Critical illness carries with it a fiscal burden of about $55 billion in the United States [4]. Patients who die in the hospital after an ICU stay experience an average cost of US$24,541 for ICU hospitalizations that end with a patient’s death [3]. Survivors of critical illness are at risk for subsequent hospitalization, outpatient evaluation, and healthcare related costs [5]. A One year mean post-hospitalization cost for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) survivors was estimated to be US$43,200 [6].

From the patients’ perspectives and according to goals that are meaningful to them it is essential to understand the burden of survival as well as dying from critical illness. Elderly patients (older than 65 years) account for about half of ICU admissions [7]. The combination of increasing age, frailty and comorbidities has a profound impact on long term outcomes after critical care [8]. Whereas severity of illness has been observed to impact short-term mortality, age and pre-existing comorbidities are the major determinants of long term outcomes [9]. In the elderly group with comorbidities, even those without baseline functional impairment, who undergo prolonged mechanical ventilation, are at risk of new functional impairment and even death [10].

THE IMPORTANCE OF PRE-ICU HEALTH STATE TRAJECTORY

Accurate assessment of baseline functional, cognitive, psychological and social reserve is essential for interpreting the effects of ICU exposures and interventions. Yet these are rarely accounted for in critical care research. We have seen that the development of ICU delirium is associated with worsening or developing long-term cognitive impairment [11]. It is not known to what extent critical illness causes or contributes to the development of delirium and long term cognitive impairment and to what degree critical illness merely unmasks pre-existing but clinically unappreciated underlying cognitive disorders. In a longitudinal population-based study of elderly residents in Olmsted County, Minnesota, the presence of pre-existing cognitive dysfunction was a major risk factor for the development of critical illness [12]. In another recent cohort of elderly community dwellers, pre-existing mild or moderate cognitive impairment increased the risk of post-ICU disability [13]. Similarly, the presence of pre-existing comorbidities is associated with worsening quality of life and cognition after critical illness [14].

Long term follow up studies observed an increased incidence of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in survivors of critical illness [15,16]. One-third of ICU survivors experience symptoms of anxiety during their first year of recovery [17]. In about 52% survivors of ARDS, symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD persisted. The pre-existing psychological illnesses were an important determinant of development and persistence of these symptoms after critical illness [18].

Physical functioning, which includes bodily function, activities of daily living (ADL) and participation in social roles, hobbies and return to work, is another area, where survivors of critical illness experience deterioration [15,19,20]. A prospective observational cohort study showed that survivors of critical illness had a 32% and 27% decline in ADL at 3 and 12 months respectively [15]. In a multicenter cohort of ARDS survivors, significant physical and cognitive deterioration has been observed at 6 and 12 months [21]. Again, diminished baseline function predicted subsequent decline in these parameters at 6 months [22].

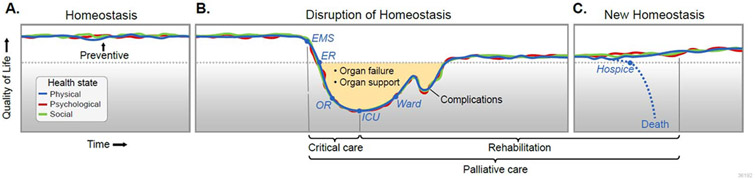

The model of critical illness describing outcome pathways after critical illness in the context of pre-existing condition is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

The model of critical illness describing outcome pathways after critical illness in the context of pre-existing condition.

“MEANINGFUL” OUTCOME: TO WHOM AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE

Medical science is unique in that it works at the intersection of biography and biology. The meaningful outcomes of critical care research therefore should seek to exploit this union, endeavoring to understand how illnesses affect the ways individuals live and make sense of their lives. Other sciences, such as economics or epidemiology, have human well-being at the center of their interests, but they do not have the intense personal focus of medicine. What defines an outcome as “meaningful” versus “not meaningful” depends on 1) from whose perspective one evaluates meaning and 2) for which purpose meaning is evaluated. Some outcomes may be meaningful for clinicians or researchers, but less meaningful for patients and their families. It can be exceedingly difficult to design research that incorporates what is important but not so easily measured. Banks of big data and electronic health records may create an illusion of omniscience, beguiling investigators into believing that they contain everything that is worth knowing. But often the most meaningful parts of medical care occur at the interstitial space shared by patients, their loved ones, and the ICU team. These are rarely documented and are difficult to depict with conventional forms of data. The term “patient-centered outcomes” has been used to describe outcomes meaningful to patients and can be contrasted with “clinician-centered outcomes,” “researcher-center outcomes,” or “healthcare organization-centered” outcomes. The best critical care research should seek to exploit the union of biography and biology, seeking to understand how illnesses and treatments interact to affect both the pathology and pathophysiology of disease, and also how patients and their families experience and make sense of illness and its aftermath.

Seminal work characterizing long term patient-centered outcomes of ICU survivors by Dale Needham’s group at Johns Hopkins University has identified measurements of physical function, cognitive function, psychiatric function, and return to work as important to survivors of critical illness. Interestingly, “survival” received the second lowest rating by patients and their families, compared to researchers, who supported survival as one of the most essential outcomes to be measured [23]. In another study looking at perspectives of clinicians on 19 core domains as outcomes, survival was one of the key outcomes alongside physical function, health-related quality of life, cognitive function and return to work [24]. Health-care utilization was one of the outcomes that ranked high in priority amongst the clinicians in Australia compared to the United States [24].

With regards to death and dying, in a survey of Medicare beneficiaries, 86% of participants expressed preference to stay home at end of life [25]. This is similar to a survey of elderly patients by the Camden Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) in the UK, where ‘time spent at home’ was identified as an important patient-centered goal [25]. For elderly patients with chronic conditions, ‘maintaining independence’ ranked as the most important outcome, followed by pain or symptom relief, and lastly, staying alive [26]. A survey of severely ill hospitalized patients identified several health states to be “worse than death.” These included bowel and bladder incontinence, relying on a breathing machine, not being able to get out of bed, not being able to eat, or having a permanent cognitive impairment [27].

MORTALITY AS A PATIENT-CENTERED OUTCOME

Short term (28, 60, 90 days) mortality has been the cornerstone of most clinical research testing an intervention or exposure in the ICU. Yet multiple problems make mortality obsolete as a meaningful outcome measure. Mere survival may not be important to patients if they are to spend the rest of their lives on organ support and in nursing homes [28]. Days alive and without organ failures may provide some advantages over just ‘mortality’ when studying ICU specific syndromes and effectiveness of interventions [29]. Inappropriate statistical methodology such as use of hazard ratios for short-term survival (implying that prolonged dying is a success) may further contribute to spurious inferences. Frequentist analysis and the use of threshold p-values reported in randomized clinical trials have been criticized for lack of robustness in reporting significant effects of an intervention on risk of death [30]. The vast majority of critical care trials using mortality as an endpoint have not yielded evidence that the interventions reduce the risk of dying [31]. Moreover, “positive” critical care trials often have a high “fragility index” [30] meaning that minimal errors or biases may lead to different statistical outcomes. Paying attention to attributable causes of death could be more informative in sample size calculations and for testing an ICU specific intervention. For example, if only 15% of mortality after sepsis admission is attributable to sepsis per se (rather than pre-existing condition), even the most effective intervention will have only a small effect on total mortality [32].

QUALITY OF LIFE, POST-INTENSIVE CARE SYNDROME AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC BURDEN

Until recently, patient-centered outcomes including quality of life, functional and cognitive impairments have rarely been the primary focus of clinical studies [33]. The physical, mental and social debility experienced by survivors of critical illness has been defined as an entity of its own, as post-ICU syndrome (PICS). This also affects families of survivors, who risk a high prevalence of psychological symptoms [33,34]. There has been a growing effort towards identifying and modifying factors in the intensive care unit that may result in PICS. Delirium from a variety of causes, including the use of sedation, from hypoxia or metabolic imbalances, and from severe sepsis has been associated with PICS development [35,36]. Physical therapy may improve functional status in patients with respiratory failure and resultant severe deconditioning [37,38]. Sedation interruption and early mobilization in the intensive care unit with physical and occupational therapy has shown to lower the number of days of delirium and result in better functional outcomes at hospital discharge [39]. Studies looking at cognitive and physical therapy post-ICU discharge suggest that such interventions are feasible and modestly effective in these domains [40,41]. Asking patients or their loved ones to keep ICU diaries is another intervention that may lower the incidence of PTSD [16,42]. PICS clinics, which are well established in the United Kingdom and parts of Europe, are beginning to become established in the United States. These serve as multidisciplinary support sources for patients as well as their families to address deficits in their different aspects of health related quality of life [43].

The socio-economic burden of critical illness to patients and families is substantial yet rarely accounted for. In a prospective follow up of ICU survivors, there was a 50% reduction in the number of patients whose income was based on employment [44]. Also noted in this study, was the high burden of care for the survivors provided by family members [44]. In a cohort of ARDS survivors, close to half of those who were employed prior to critical illness returned to work at 6 and 12 months, and government medical insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) replaced employment-linked commercial medical insurance in a substantial number of cases [45]. Those unable to return to work reported worse quality of life [45]. Financial stress, even amongst the insured, impacts not only in survivors but also family members, and is observed to have a direct effect on symptoms of anxiety and depression [46]. Recently, experience from a 5-week multidisciplinary program InS:PIRE (Intensive care Syndrome: Promoting Independence and Return to Employment) from Scotland, revealed effectiveness in improving quality of life and return to employment or volunteering in ICU survivors [47].

QUALITY OF DYING

A primary focus on survival and quality of life in those who are fortunate to survive has at times, overshadowed an equally important focus on quality of dying. Up to one third ICU patients die before hospital discharge, and most patients who die in the ICU do so after a decision has been made to withhold or withdraw some medical treatment [48,49]. The quality of the process of end of life decision making and caring for dying patients is variable among ICUs and among physicians in a single ICU [50,51]. Several nursing, physician, hospital, family member, and patient factors have been shown to play a role in end-of-life decision making [52].

Recent efforts have been made to identify important patient-centered as well as family-centered components essential to a high quality dying process [53-55]. Beyond achieving adequate control of symptoms, incorporating high quality dying as a meaningful outcome, includes creating opportunities for patients and families to say good-bye [56], helping patients achieve life closure and honoring last wishes [57], getting affairs in order, honoring spiritual beliefs and traditions, not dying alone, and maintaining a sense of awareness [53]. Understanding specific preferences that patients may have, such as participating in a family event or being at home, becomes essential when trying to deliver care that honors individuals’ values and preferences [58]. Though medical care, and especially ICU care, may seem costly, at times the most important job is to build a complex ledge that stops the free-fall and buys everyone time to do or say what is important to them. If patients and their loved ones understand that descent is inevitable, “the time on the ledge can become holy.” [59].

CONCLUSION

Critical care, and all medical care, can and should be understood in the context of the trajectory of each person’s life. Therefore, critical care’s scientific inquiry should strive to incorporate key information about an individual’s background in order to understand where in life’s trajectory each patient is, at the onset of critical illness. We recognize the enormous challenges that face researchers who are trying to develop reliable measures necessary for interpreting the effects of critical care exposures and interventions on meaningful outcomes. Patient preference, preexisting functional, cognitive and psychosocial status, and both quality of life and quality of dying ought to be taken into consideration when testing novel hypotheses.

KEY POINTS.

Meaningful outcomes on critical illness are important to understand and define from the perspectives of patients, families and providers.

Meaningful outcomes need to be concordant with patients’ wishes. From patient perspective, the quality of life, independence, and quality of death and dying are often as or more important than survival per se.

Preexisting functional, cognitive and psychosocial status and both quality of life and quality dying have to be taken into consideration when testing novel research, quality improvement and policy interventions.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

- 1.Berger R A healthy person has a thousand wishes, a sick person only one. Agnes Karll Schwest Krankenpfleger 1968; 22:315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunstan GR. Hard questions in intensive care. A moralist answers questions put to him at a meeting of the Intensive Care Society, Autumn, 1984. Anaesthesia 1985; 40:479–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Doig CJ, Ghali WA, et al. Detailed cost analysis of care for survivors of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruhl AP, Huang M, Colantuoni E, Karmarkar T, Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in ARDS survivors: a 1-year longitudinal national US multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43:980–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisani MA, Redlich C, McNicoll L, et al. Underrecognition of preexisting cognitive impairment by physicians in older ICU patients. Chest 2003; 124:2267–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas B, Wunsch H. How does prior health status (age, comorbidities and frailty) determine critical illness and outcome? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016; 22:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garland A, Olafson K, Ramsey CD, et al. Distinct determinants of long-term and short-term survival in critical illness. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson ME, Barwise A, Heise KJ, et al. Long-term return to functional baseline after mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:562–569.* Population-based study describing baseline functional status and short and long term changes in survivors of critical illness

- 11.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1306–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teeters DA, Moua T, Li G, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and risk of critical illness. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:2045–2051.* This population based study suggested that cognitive impairment often precedes ICU admission and patients who have mild cognitive impairment are at increased risk of ICU admission

- 13.Ferrante LE, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, et al. Pre-ICU cognitive status, subsequent disability, and new nursing home admission among critically ill older adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15:622–629.* Another study confirming the importance of pre-ICU cognitive status on post-ICU outcomes

- 14.Griffith DM, Salisbury LG, Lee RJ, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life after ICU: Importance of patient demographics, previous comorbidity, and severity of illness. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:594–601.** In the nested cohort from a previous randomized control trial, post ICU quality of life was determined by pre-ICU co-morbidities, social deprivation and age, but not severity of acute illness

- 15.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2:369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bienvenu OJ, Gerstenblith TA. Posttraumatic stress disorder phenomena after critical illness. Crit Care Clin 2017; 33:649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016; 43:23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bienvenu OJ, Friedman LA, Colantuoni E, et al. Psychiatric symptoms after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:38–47.** Long term multicenter follow up of ARDS survivors describes high long-term prevalence of psychiatric conditions accross multiple domains. Again, the pre-ICU psychiatric morbidity was highly associated with post-ICU status

- 19.Hopkins RO, Suchyta MR, Kamdar BB, et al. Instrumental activities of daily living after critical illness: A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14:1332–1343.* Systematic review of studies reporting impairments in instrumental activities of daily living in ICU survivors

- 20.Parry SM, Huang M, Needham DM. Evaluating physical functioning in critical care: considerations for clinical practice and research. Crit Care 2017; 21:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, et al. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biehl M, Kashyap R, Ahmed AH, et al. Six-month quality-of-life and functional status of acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors compared to patients at risk: a population-based study. Crit Care 2015; 19:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Davis WE, et al. Perspectives of survivors, families and researchers on key outcomes for research in acute respiratory failure. Thorax 2018; 73:7–12.** Stakeholder survey identified four critical outcome domains: physical function, cognitive function, return to work or prior activities, and mental health

- 24.Hodgson CL, Turnbull AE, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Core domains in evaluating patient outcomes after acute respiratory failure: International multidisciplinary clinician consultation. Phys Ther 2017; 97:168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home - A patient-centered goal and outcome. New Engl J Med 2016; 375:1610–1612* Thoughtful perspective with regards to “days spent at home” as a pragmatic, meaningful patient centered outcome

- 26.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, et al. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1854–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States worse than death among hospitalized patients with serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1557–1559.** Survey of patients hospitalized with serious illnesses identifies several conditions that the patients considered to be as bad or worse outcome than death

- 28.Curtis JR. The “patient-centered” outcomes of critical care: what are they and how should they be used? New Horiz 1998; 6:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell JA, Lee T, Singer J, De Backer D, Annane D. Days alive and free as an alternative to a mortality outcome in pivotal vasopressor and septic shock trials. J Crit Care 2018; May 12:in press.* Using several recent clinical trials comparing different vasopressors, the authors identified “days alive and free from life support interventions” as an outcome more appropriate than mortality for clinical trials

- 30.Ridgeon EE, Young PJ, Bellomo R, et al. The fragility index in multicenter randomized controlled critical care trials. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:1278–1284.* Using a novel statistical measure, “fragility index”, the authors point out that the “positive” or “negative” results of critical care trials often depend on a small number of events and, consequently, have far from robust and replicable results

- 31.Vincent JL. Improved survival in critically ill patients: are large RCTs more useful than personalized medicine? No. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42:1778–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shankar-Hari M, Harrison DA, Rowan KM, Rubenfeld GD. Estimating attributable fraction of mortality from sepsis to inform clinical trials. J Crit Care 2018; 45:33–39.** The authors calculated attributable mortality of sepsis which may be considerably smaller than actual mortality, the finding that can have broad implications on sample size calculations and the overall interpretation of research studies of ICU interventions

- 33.Gaudry S, Messika J, Ricard JD, et al. Patient-important outcomes in randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Ann Intensive Care 2017; 7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrinec AB, Martin BR. Post-intensive care syndrome symptoms and health-related quality of life in family decision-makers of critically ill patients. Palliat Support Care 2017; December 26:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girard TD, Thompson JL, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6:213–222.* Prospective study describing association between different clinical phenotypes of delirium and long-term cognitive dysfunction

- 36.Bruck E, Schandl A, Bottai M, Sackey P. The impact of sepsis, delirium, and psychological distress on self-rated cognitive function in ICU survivors-a prospective cohort study. J Intensive Care 2018; 6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiang LL, Wang LY, Wu CP, et al. Effects of physical training on functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Phys Ther 2006; 86:1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Su CL, Wu YT, et al. Physical training is beneficial to functional status and survival in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. J Formos Med Assoc 2011; 110:572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 373:1874–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC, et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:1088–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the activity and cognitive therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones C, Backman C, Capuzzo M, et al. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care 2010; 14:R168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huggins EL, Bloom SL, Stollings JL, et al. A clinic model: Post-intensive care syndrome and post-intensive care syndrome-family. AACN Adv Crit Care 2016; 27:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffiths J, Hatch RA, Bishop J, et al. An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health-related quality of life after critical illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care 2013; 17:R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamdar BB, Huang M, Dinglas VD, et al. Joblessness and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome in a 1-year national multicenter study. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2017; 196:1012–1020.* Multicenter study describing return to work outcomes in ARDS survivors

- 46.Khandelwal N, Hough CL, Downey L, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of financial stress in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:e530–e539.* Multicenter long term follow up study describing financial stress in survivors of critical illness

- 47.McPeake J, Shaw M, Iwashyna TJ, Daniel M, Devine H, Jarvie L, et al. Intensive care syndrome: promoting independence and return to employment (InS:PIRE). Early evaluation of a complex intervention. PloS One 2017; 12:e0188028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown SM, Lanspa MJ, Jones JP, et al. Survival after shock requiring high-dose vasopressor therapy. Chest 2013; 143:664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quill CM, Ratcliffe SJ, Harhay MO, Halpern SD. Variation in decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapies in US ICUs. Chest 2014; 146:573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garland A, Connors AF. Physicians’ influence over decisions to forego life support. J Palliat Med 2007; 10:1298–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:1174–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000; 284:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Virdun C, Luckett T, Lorenz K, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: A meta-synthesis identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families describe as being important. Palliat Med 2017; 31:587–601.* Systematic review of patient and family perspectives on important domains of end-of-life care

- 55.Courtright KR, Benoit DD, Halpern SD. Life after death in the ICU: detecting family-centered outcomes remains difficult. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43:1529–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson ME. Saving a death when we cannot save a life in the intensive care unit. JAMA Intern Med 2018; April 16 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cook D, Swinton M, Toledo F, Clarke F, Rose T, Hand-Breckenridge T, et al. Personalizing death in the intensive care unit: the 3 Wishes Project: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turnbull AE, Hartog CS. Goal-concordant care in the ICU: a conceptual framework for future research. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43:1847–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.@vitaincerta, Turnbull AE, March 2, 2018, https://twitter.com/vitaincerta/status/969737340997505024* Conteptual framework for measuring goal-concordant care as an important outcome of critical illness