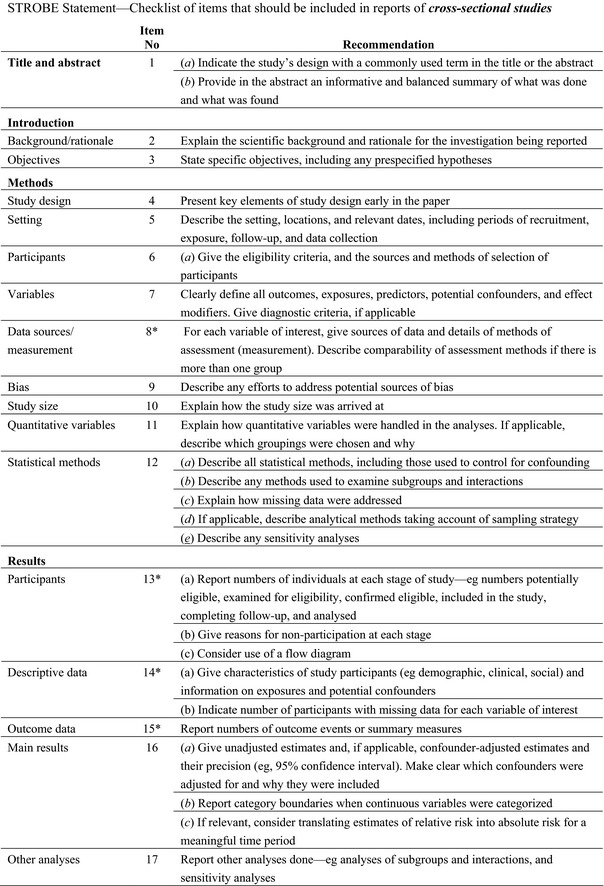

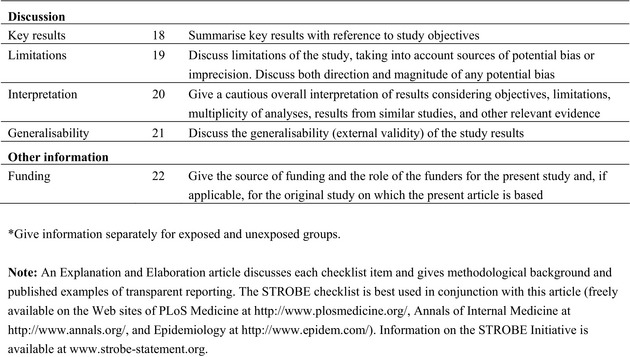

Abstract

The Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings added to Food (FAF) provided a scientific opinion re‐evaluating the safety of phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) as food additives. The Panel considered that adequate exposure and toxicity data were available. Phosphates are authorised food additives in the EU in accordance with Annex II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008. Exposure to phosphates from the whole diet was estimated using mainly analytical data. The values ranged from 251 mg P/person per day in infants to 1,625 mg P/person per day for adults, and the high exposure (95th percentile) from 331 mg P/person per day in infants to 2,728 mg P/person per day for adults. Phosphate is essential for all living organisms, is absorbed at 80–90% as free orthophosphate excreted via the kidney. The Panel considered phosphates to be of low acute oral toxicity and there is no concern with respect to genotoxicity and carcinogenicity. No effects were reported in developmental toxicity studies. The Panel derived a group acceptable daily intake (ADI) for phosphates expressed as phosphorus of 40 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day and concluded that this ADI is protective for the human population. The Panel noted that in the estimated exposure scenario based on analytical data exposure estimates exceeded the proposed ADI for infants, toddlers and other children at the mean level, and for infants, toddlers, children and adolescents at the 95th percentile. The Panel also noted that phosphates exposure by food supplements exceeds the proposed ADI. The Panel concluded that the available data did not give rise to safety concerns in infants below 16 weeks of age consuming formula and food for medical purposes.

Keywords: phosphates, phosphorus, food additive, acceptable daily intake, risk assessment, safety

Short abstract

This publication is linked to the following EFSA Supporting Publications article: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/sp.efsa.2019.EN-1624/full

Summary

The present opinion document deals with the re‐evaluation of phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) when used as a food additive.

Phosphates are authorised food additives in the European Union (EU) in accordance with Annex II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives and specific purity criteria have been defined in the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012. E 338, E 339, E 340 and E 341 are also authorised in food category 13.1 foods for infants and young children.

Phosphates have been previously evaluated by the EU Scientific Committee on Food (SCF, 1978, 1991, 1994, 1997) and by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA, 1974, 1982a,b, 2002). JECFA concluded that the allocation of an acceptable daily intake (ADI) was not appropriate for phosphates ‘as phosphorus is an essential nutrient and unavoidable constituent of food’ and it was decided, therefore, to assign a ‘maximum tolerable daily intake’ (MTDI) rather than an ADI. The MTDI allocated was 70 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day (expressed as phosphorus) for the sum of phosphates and polyphosphates, both naturally present in food and ingested as food additives (JECFA, 1982a). The SCF subsequently agreed with the JECFA MTDI estimate for phosphates and assigned the cations an ADI ‘not specified’ as they are natural constituents of man, animals and plants (SCF, 1991).

The Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals (EVM) further concluded that a total intake of 2,400 mg/day (considering 2,110 mg/day inorganic phosphorus from food including food additives and water and 250 mg/day from supplemental phosphorus) does not result in any adverse effects (Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals, 2003).

In the EFSA NDA Opinion on Tolerable Upper Intake level of phosphorus, the upper level for phosphorus was not established because available data were not sufficient and indicate that normal healthy adults can tolerate phosphorus (phosphates) intake up to at least 3,000 mg/day without adverse systemic effects (EFSA NDA Panel, 2005).

The Panel on Nutrition, Dietetic Products, Novel Food and Allergy of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) published an assessment of dietary intake of phosphorus in relation to tolerable upper intake levels suggesting 3,000 mg/day as provisional upper level (UL) for total phosphorus intake in adults and 750 mg/day as UL for supplements (VKM, 2017).

Phosphate is essential for all living organisms. Inorganic phosphate used as food additives assessed in this opinion is assumed to dissociate in the gastrointestinal tract. The inorganic phosphorus deriving from food additives is mainly absorbed in the amount of approximately 80–90% as free orthophosphate. Excretion is via the kidney through glomerular filtration and tubular handling.

The Panel considered phosphates to be of low acute oral toxicity and there is no concern with respect to genotoxicity and carcinogenicity.

In standard short‐term, subchronic and chronic toxicity studies, the only significant adverse effect of phosphates is calcification of the kidney and tubular nephropathy. In the chronic rat study with sodium triphosphate, the no‐observable‐adverse‐effect level (NOAEL) was 76 mg/kg bw per day phosphorus (Hodge, 1960). Adding the background dietary phosphorus of 91 mg/kg bw per day to the NOAEL of 76 mg P/kg bw per day gives a total value of 167 mg P/kg bw per day.

In studies performed in mice, rats, rabbits or hamsters, there are no signs of reproductive or developmental toxicity at any dose tested. The Panel thus concluded that exposure to phosphates do not present any risk for reproductive or developmental toxicity.

The epidemiological studies reviewed did not find consistent associations between dietary phosphorous intake and cardiovascular‐related outcomes and do not provide sufficient and reliable data to assess the role of phosphate on bone health.

Clinical interventional trials in which the doses were given on top of the normal diet were performed over several months. No impairment of the renal function was reported with daily doses up to 2,000 mg phosphorus (28.6 mg/kg per day), whereas doses of 4,800 mg/day (68.6 mg/kg per day) elicited renal impairment. Histopathological examinations of human kidney specimens from exposed patients showed similar findings as seen in animals. In several of the studies using phosphorus doses up to 2,000 mg/day, the subjects had soft stools or diarrhoea which is not to be seen as adverse but is classified as discomfort. However, when higher doses are given, such as the doses for bowel cleansing in preparation for colonoscopy (e.g. 11,600 mg/kg or 165.7 mg/kg bw) these doses acted as a cathartic agent and this effect has to be clearly seen as adverse.

Several case reports indicate that a high acute single dose of phosphate (160 mg/kg bw and more) can induce renal impairment.

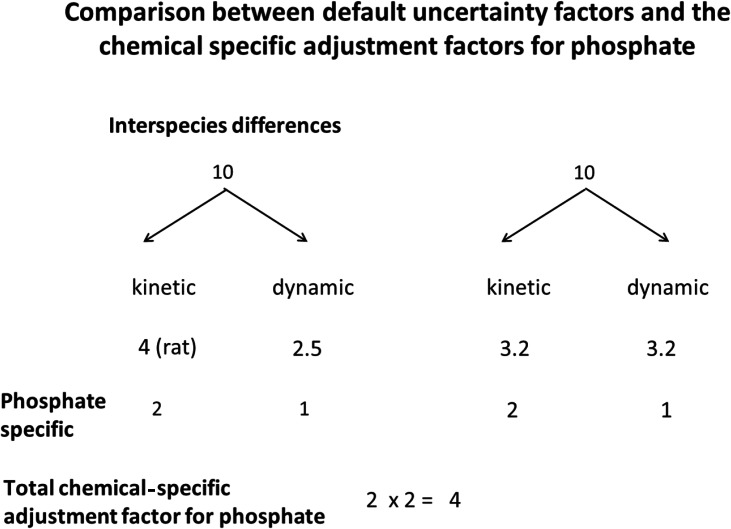

The evidence from epidemiological and human interventional studies is not suited to derive an ADI. The Panel therefore selected the 167 mg P/kg bw per day NOAEL identified by Hodge (1960) as the basis to derive the ADI. The chemical‐specific adjustment factor for phosphate accounting for interspecies and interindividual differences in toxicokinetics (TK) and toxicodynamics (TD) is 2 × 2 = 4. To this value, the phosphorus‐specific uncertainty factor of 4 is to be applied resulting in an ADI value of 42 mg/kg bw per day, rounded to 40 mg/kg bw per day.

Currently, phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) are authorised food additives in the EU with maximum permitted levels (MPLs) ranging from 500 to 20,000 mg/kg in 104 authorised uses and at quantum satis (QS) in four.

To assess the dietary exposure to phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) from their uses as food additives, the exposure was calculated based on two different sets of concentration data: (1) MPLs as set down in the EU legislation (defined as the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario); and (2) reported use levels (defined as the refined exposure assessment scenario).

While analytical data were used to consider the exposure to phosphorus from all dietary sources.

In the context of this opinion, the Panel was in the special situation to assess the safety of food additives, phosphate salts, which are also nutrients. The Panel based its assessment on the toxicity of phosphorus (phosphate moiety). Since the ADI encompasses the phosphorus intake from natural sources and from food additives sources, the usual exposure assessment using the reported use levels of the food additives was not appropriate to characterise the risk linked to the exposure to phosphorus and the exposure assessment was based on analytical data of the total phosphorus content of foods. In this scenario, the exposure exceeds the ADI of 40 mg/kg bw per day in infants from 12 weeks to 11 months, toddlers and children both at the mean and high level. In adolescents, the high level is also exceeding the ADI of 40 mg/kg bw per day.

Based on the reported use levels, the Panel calculated two refined exposure estimates: a brand‐loyal consumer scenario and a non‐brand‐loyal scenario. The Panel considered that the refined exposure assessment approach resulted in more realistic long‐term exposure estimates and that the refined non‐brand loyal scenario is the most relevant exposure scenario for the safety evaluation of phosphates. In the non‐brand‐loyal exposure assessment scenario, estimated exposure to phosphates ranged between 1 and 48 mg P/kg bw per day at the mean and between 3 and 62 mg P/kg bw per day at the 95th percentile for all population groups.

The derived ADI 40 mg P/kg bw per day results in a exposure to phosphorus of 2,800 mg/person per day for an adult of 70 kg which is within the safety level of exposure of 3,000 mg/person per day set by the EFSA NDA Panel (2005).

The Panel concluded that the group ADI of 40 mg/kg bw per day, expressed as phosphorus, is protective for healthy adults because it is below the doses at which clinically relevant adverse effects were reported in short‐term and long‐term studies in humans. However, this ADI does not apply to humans with moderate to severe reduction in renal function. Ten per cent of general population might have chronic kidney disease with reduced renal function and they may not tolerate the amount of P per day which is at the level of ADI.

The Panel noted that in the exposure estimates based on analytical data exceeded the proposed ADI for infants, toddlers and children at the mean level and for infants, toddlers, children and adolescents at the 95th percentile. The Panel also noted that P exposure from food supplements exceeds the proposed ADI.

The Panel concluded that the available data did not give rise to safety concerns in infants below 16 weeks of age consuming formula and food for medical purposes. When receiving data on the content of contaminants in formula, the Panel noted that the high aluminium content may exceed the tolerable weekly intake (TWI).

The Panel recommends that:

The EC considers setting numerical Maximum Permitted Level for phosphates as food additives in food supplements.

The European Commission considers revising the current limits for toxic elements (Pb, Cd, As and Hg) in the EU specifications for phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) in order to ensure that phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) as a food additive will not be a significant source of exposure to those toxic elements in food.

The European Commission considers revising the current limit for aluminium in the EU specifications for the use of calcium phosphate (E 341).

The European Commission to consider revising the current EU specifications for calcium dihydrogen phosphate (E 341(i)), calcium hydrogen phosphate (E 341(ii)), tricalcium phosphate (E 341(iii)), dimagnesium phosphate (E 343(ii)) and calcium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(vii)) to include characterisation of particle size distribution using appropriate statistical descriptors (e.g. range, median, quartiles) as well as the percentage (in number and by mass) of particles in the nanoscale (with at least one dimension < 100 nm) present in calcium dihydrogen phosphate (E 341(i)), calcium hydrogen phosphate (E 341(ii)), tricalcium phosphate (E 341(iii)), dimagnesium phosphate (E 343(ii)) and calcium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(vii)) used as a food additive. The measuring methodology applied should comply with the EFSA Guidance document (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018).

The development of analytical methods for the determination of phosphate additives in the range of foods and beverages permitted to contain them should be considered.

The EFSA Scientific Committee reviews current approaches to the setting of health‐based guidance values for regulated substances which are also nutrients to assess if a coherent harmonised strategy for such risk assessments should be devised.

1. Introduction

The present opinion deals with the re‐evaluation of the following food additives: phosphoric acid (E 338), monocalcium phosphate (E 341(i)), dicalcium phosphate (E 341(ii)), tricalcium phosphate (E 341(iii)), monomagnesium phosphate (E 343(i)), dimagnesium phosphate (E 343(ii)) monosodium phosphate (E 339(i)), disodium phosphate (E 339(ii)), trisodium phosphate (E 339(iii)), monopotassium phosphate (E 340(i)), dipotassium phosphate (E 340(ii)), tripotassium phosphate (E 340(iii)), disodium diphosphate (E 450(i)), trisodium diphosphate (E 450(ii)), tetrasodium diphosphate (E 450(iii)), tetrapotassium diphosphate (E 450(v)), dicalcium diphosphate (E 450(vi)), calcium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(vii)), magnesium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(ix)), pentasodium triphosphate (E 451(i)), pentapotassium triphosphate (E 451(ii)), sodium polyphosphate (E 452(i)), potassium polyphosphate (E 452(ii)), sodium calcium polyphosphate (E 452(iii)) and calcium polyphosphate (E 452(iv)). For brevity, these food additives will be referred to as phosphates in this document (listed overview of the substances considered in this opinion is available in Appendix A).

As usual in the re‐evaluation of food additives, this opinion addresses the safety of phosphorus intake from the use of the above listed food additives in the general population.

During the drafting of the opinion, a request for extension of use has been received and is included in this opinion. The terms of reference are reported below.

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the European Commission

1.1.1. Background to the re‐evaluation of phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) as food additives

Regulation (EC) No 1333/20081 of the European Parliament and of the Council on food additives requires that food additives are subject to a safety evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) before they are permitted for use in the European Union. In addition, it is foreseen that food additives must be kept under continuous observation and must be re‐evaluated by EFSA.

For this purpose, a programme for the re‐evaluation of food additives that were already permitted in the European Union before 20 January 2009 has been set up under the Regulation (EU) No 257/20102. This Regulation also foresees that food additives are re‐evaluated whenever necessary in the light of changing conditions of use and new scientific information. For efficiency and practical purposes, the re‐evaluation should, as far as possible, be conducted by group of food additives according to the main functional class to which they belong.

The order of priorities for the re‐evaluation of the currently approved food additives should be set on the basis of the following criteria: the time since the last evaluation of a food additive by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) or by EFSA, the availability of new scientific evidence, the extent of use of a food additive in food and the human exposure to the food additive taking also into account the outcome of the Report from the Commission on Dietary Food Additive Intake in the EU3 of 2001. The report ‘Food additives in Europe 20004’ submitted by the Nordic Council of Ministers to the Commission, provides additional information for the prioritisation of additives for re‐evaluation. As colours were among the first additives to be evaluated, these food additives should be re‐evaluated with a highest priority.

In 2003, the Commission already requested EFSA to start a systematic re‐evaluation of authorised food additives. However, as a result of adoption of Regulation (EU) 257/2010 the 2003 Terms of References are replaced by those below.

1.1.1.1. Terms of Reference

The Commission asks the European Food Safety Authority to re‐evaluate the safety of food additives already permitted in the Union before 2009 and to issue scientific opinions on these additives, taking especially into account the priorities, procedures and deadlines that are enshrined in the Regulation (EU) No 257/2010 of 25 March 2010 setting up a programme for the re‐evaluation of approved food additives in accordance with the Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on food additives.

1.1.2. Background to the request for the extension of use of phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) as food additives

The Directorate‐General for Health and Food Safety received a request for the extension of use of phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) by removing the restriction ‘only sugar confectionary’ in the relevant provision in the food category 05.2 ‘Other confectionary including breath refreshing microsweets’.

1.1.2.1. Terms of Reference

The European Commission requested EFSA to provide a scientific opinion on the safety of the proposed extension of use in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1331/2008 establishing a common authorisation procedure for food additives, food enzymes and food flavourings and proposed that EFSA incorporates in that risk assessment the assessment of the safety of the proposed extension of use.

1.1.3. Interpretation of Terms of Reference

The former ANS Panel described its risk assessment paradigm in its Guidance for submission for food additive evaluations in 2012 (EFSA ANS Panel, 2012). This Guidance states, that in carrying out its risk assessments, the Panel sought to define a health‐based guidance value (HBGV), e.g. an acceptable daily intake (ADI) (IPCS, 2004) applicable to the general population. ADI is defined as ‘an estimate of the amount of a substance in food or drinking water that can be consumed over a lifetime without presenting an appreciable risk to health. It is usually expressed as milligrams of the substance per kilogram of body weight and applies to chemical substances such as food additives, pesticide residues and veterinary drugs’. (EFSA Glossary).

Phosphates are normal constituents in the body and are regular components of the diet. According to the EFSA NDA Panel the available data are not sufficient to establish an upper level (UL) for phosphorus (EFSA NDA Panel, 2005). The EFSA NDA Panel stated in this opinion that ‘The available data indicate that normal healthy individuals can tolerate phosphorus (phosphate) intakes up to at least 3,000 mg/day without adverse systemic effects’. In 2015, the NDA Panel set adequate intakes (AIs) values for various age groups.

Inorganic phosphates authorised as a food additive are efficiently absorbed and used systemically. It is noteworthy that although phosphorus is an essential constituent of the human body and other life forms, the element itself always occurs systemically in the oxidation state (V) as free or combined phosphate. It is absorbed and involved in many structural and functional roles as phosphate (HPO2− 4) (see Section 3.5.1). However, dietary and environmental exposure to phosphorus may come from other forms of phosphorus (V). Whereas the systemic physiologically active moiety is phosphate it has become conventional in nutritional and risk assessment as well as regulatory contexts to use inorganic phosphorus as generic the term (Pi). For the purposes of this opinion, phosphorus will be expressed as P. This is particularly necessary in the context of establishing a group ADI which encompasses phosphorus from all sources including all classes of phosphates as food additives (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452). The mass conversion factors between phosphate and P2O5 or P are summarised in Appendix B.

The Panel considered that sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium salts of phosphate and condensed phosphates are expected to dissociate in the gastrointestinal tract into phosphate and their corresponding cations. The resulting sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium cations will enter their normal physiological processes. The kinetics of the corresponding cations are not assessed in the opinion.

Data were not always available for all the authorised phosphates for all endpoints but for the reason described above the Panel considered that it is possible to perform read‐across between different phosphate additives.

The opinion will also conclude on the proposed extensions of use received during the course of the drafting opinion.

1.2. Information on existing authorisations and evaluations

Phosphates are authorised food additives in the EU in accordance with Annex II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/20085. E 338, E 339, E 340, E 341 are also authorised in food category 13.1 foods for infants and young children. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/127 and Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/128, as well as Commission Directive 2006/141/EC and Commission Directive 1999/21/EC, define minimum and maximum levels for phosphorus as well as for the cations of the various phosphate salts (i.e. calcium, potassium and sodium) in the final formula. These statutory requirements are based on the scientific advice by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF, 1996, 1997, 1998) and EFSA (EFSA NDA Panel, 2013). The minimum and maximum levels of phosphorus for infant formula are set at 25 mg/100 kcal and 90 mg/100 kcal, in the case of infant formula based on soy the maximum level is 100 mg/100 kcal. The minimum and maximum levels for infant formula for special medical purposes are set at 25 mg/100 kcal and 100 mg/100 kcal. In Europe, the phosphates that are permitted as additives in infant formula (category 13.1.1) and foods for infants for special medical purposes (13.1.5.1) are specified in Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008. The permitted level of phosphates used as a food additive, either alone or in combination, is set at a maximum concentration of 1,000 mg/L reconstituted formula. The maximum level is expressed as P2O5.

In addition, tricalcium phosphate is authorised, according to Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008, for use as food additives in nutrients in infant formula. The maximum carry‐over of tricalcium phosphate from nutrients is set at 150 mg/kg as P2O5 and within the limit for calcium, phosphorus and calcium:phosphorus ratio as specified in Commission Directive 2006/141/EC. In addition to their use as food additives, calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium salts of orthophosphoric acid are included in the list of mineral substances which may be used in the manufacture of food supplements reported in the Annex II of Directive 2002/46/EC6 and in the list of mineral substances which may be added to foods reported in the Annex II of Regulation (EC) No 1925/20067.

Calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium salts of orthophosphoric acid are included in the Union list set out in the Annex to Regulation (EU) No 609/20138 as permitted for use in: infant formula and follow‐on formula, food for special medical purposes and total diet replacement for weight control. Calcium and magnesium sodium salts of orthophosphoric acid are also permitted for use in processed cereal‐based food and baby food.

According to the CODEX STAN 72‐1981 on Infant Formula and Formulas for Special Medical Purposes (FSMP) intended for infants, sodium phosphates (339(i), (ii), (iii)) and potassium phosphates (340(i), (ii), (iii)) may be used as additives in infant formula and infant FSMP. The maximum level is specified at 450 mg/L as phosphorus in the ready‐to‐use product, singly or in combination and within the limits for sodium, potassium and phosphorus (SNE, 2018).

Phosphates have been previously evaluated by the EU SCF (1978, 1991, 1994, 1997) and by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) latest in 1973 and 1982 (JECFA, 1974, 1982a,b).

The toxicology and safety of diphosphates, triphosphates and polyphosphates when used as food additives has previously been evaluated by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) as part of a larger group of phosphate compounds (JECFA, 1964, 1974, 1982a,b, 1986, 2002). At its 26th meeting, JECFA concluded that the allocation of an ADI was not appropriate for phosphates ‘as phosphorus is an essential nutrient and unavoidable constituent of food’ (JECFA, 1982a). It was decided, therefore, to assign a ‘maximum tolerable daily intake’ (MTDI) rather than an ADI. The MTDI allocated was 70 mg/kg bw per day (expressed as phosphorus) for the sum of phosphates and polyphosphates, both naturally present in food and ingested as food additives. ‘The lowest level of phosphate that produced nephrocalcinosis in rat (1% P in the diet) is used as the basis for the evaluation and, by extrapolation based on the daily food intake of 2,800 calories, gives a dose level of 6,600 mg P per day as the best estimate of the lowest level that might conceivably cause nephrocalcinosis in man’. The use of a safety factor was not considered suitable by JECFA with the justification that phosphorous is also a nutrient.

The SCF agreed with the JECFA MTDI estimate for phosphates and assigned the cations an ADI ‘not specified’ as they are natural constituents of man, animals and plants (SCF, 1991).

In 2012, JECFA evaluated magnesium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(ix)) for use as food additive (JECFA, 2012a). In its 76th report, JECFA stated the following: ‘The information submitted to the Committee and in the scientific literature did not indicate that the MTDI of 70 mg/kg bw for phosphate salts, expressed as phosphorus, is insufficiently health protective. On the contrary, because the basis for its derivation might not be relevant to humans, it could be overly conservative. Therefore, there is a need to review the toxicological basis of the MTDI for phosphate salts expressed as phosphorus (JECFA, 2012b).

The Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals (EVM) used as a starting point 750 mg/day; this is the dose that, after oral administration of phosphorus as various phosphate salts, gives osmotic diarrhoea and mild gastrointestinal symptoms in humans. The EVM applied an uncertainty factor of 3 (to allow interindividual variations) to the 750 mg/day and concluded that a supplemental intake of 250 mg/day (3.6 mg/kg bw per day) would not be expected to induce adverse effects (Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals, 2003). The EVM further concluded that a total intake of 2,400 mg/day (considering 2,110 mg/day inorganic phosphorus from food including food additives and water and 250 mg/day from supplemental phosphorus) does not result in any adverse effects. The exposure calculation in food has been based on a survey from 1986/7 (NDNS 1986/7) which does not include specific estimation of phosphates content in food from food additives.

In the EFSA NDA Opinion on Tolerable Upper Intake level of phosphorus (EFSA NDA Panel, 2005), the upper level for phosphorus was not established because available data were not sufficient, although some adverse gastrointestinal effects have been reported at doses of phosphorus‐containing supplements exceeding 750 mg/day. EFSA reported that the mean dietary and supplemental intake of phosphorus in European countries is approximately 1,000–1,500 mg/day and indicate that normal healthy adults can tolerate phosphorus (phosphates) intake up to at least 3,000 mg/day without adverse systemic effects.

In 2015, EFSA published a Scientific Opinion on Reference Values for phosphorus setting adequate intakes (AIs) for all population groups. The AI recommended is 160 mg/day for infants aged 7–11 months, between 250 and 640 mg/day for children and 550 mg/day for adults. The AI for phosphorus has been derived based on the Dietary Reference Values (DRVs) for calcium by using a molar calcium to phosphorus ratio of 1.4:1 (EFSA NDA Panel, 2015).

In 2006, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the New Zealand Ministry of Health published AIs for infants between 0 and 6 months (Australian Government, NHMRC). The AI of 100 mg/day was calculated by multiplying the average intake of breast milk (0.78 L/day) by the average concentration of phosphorus in breast milk (124 mg/L) from 10 studies reviewed by Atkinson et al. (1995).

The Panel on Nutrition, Dietetic Products, Novel Food and Allergy of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) published an assessment of dietary intake of phosphorus in relation to tolerable upper intake levels suggesting 3,000 mg/day as provisional UL for total phosphorus intake in adults and 750 mg/day as UL for supplements (Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM, 2017)).

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

The Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF) and its predecessor, the Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources, were not provided with a newly submitted dossier. EFSA, therefore, launched a public call for data9 and a public consultation.10 A technical report has been issued by EFSA collecting the answers received in response to the public consultation. All answers received were considered in the development of this opinion.

For the re‐evaluation, the Panel based its assessment on information submitted to EFSA following the public calls for data, the public consultation, information from previous evaluations and additional available literature up to 18 March 2019. Attempts were made at retrieving relevant original study reports on which previous evaluations or reviews were based however these were not always available to the Panel.

Following the request for additional data on particle size sent by EFSA on 18 September 2018, one of the Interested Parties requested a clarification teleconference, which was held on 4 October 2018.

An applicant has submitted a dossier in support of the application for the extension of use of phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) as a food additive which is also addressed in this opinion (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 1).

The EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database (Comprehensive Database11) was used to estimate the dietary exposure.

The Mintel's Global New Products Database (GNPD) is an online resource listing food products and compulsory ingredient information that are included in labelling. This database was used to verify the use of food additive (E 338, E 341(i), E 341(ii), E 341(iii), E 343(i), E 343(ii) E 339(i)), (E 339(ii), E 339(iii), E 340(i), E 340(ii), E 340(iii), E 450(i), E 450(ii), E 450(iii), E 450(v), E 450(vi), E 450(vii), E 450(ix), E 451(i), E 451(ii), E 452(i), E 452(ii), E 452(iii) and E 452(iv) in food products.

2.2. Methodologies

This opinion was formulated following the principles described in the EFSA Guidance on transparency with regard to scientific aspects of risk assessment (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2009) and following the relevant existing guidance documents from the EFSA Scientific Committee.

The FAF Panel assessed the safety of phosphates as food additives in line with the principles laid down in Regulation (EU) 257/2010 and in the relevant guidance documents: Guidance on submission for food additive evaluations by the SCF (2001) and taking into consideration the Guidance for submission for food additive evaluations in 2012 (EFSA ANS Panel, 2012).

On 31 May 2017, EFSA published a guidance document on the risk assessment of substances present in food intended for infants below 16 weeks of age thus enabling EFSA to assess the safety of food additives uses in food for infants below 12 weeks of age (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017). Therefore, the current evaluation also addresses the safety of use of food additives for all age groups, including the infants below 12 or 16 weeks of age following the principles outlined in that guidance.

When the test substance was administered in the feed or in the drinking water, but doses were not explicitly reported by the authors as mg/kg bw per day based on actual feed or water consumption, the daily intake was calculated by the Panel using the relevant default values as indicated in the EFSA Scientific Committee Guidance document (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2012a) for studies in rodents or, in the case of other animal species, by JECFA (2000). In these cases, the daily intake is expressed as equivalent. When in human studies in adults (aged above 18 years) the dose of the test substance administered was reported in mg/person per day, the dose in mg/kg bw per day was calculated by the Panel using a body weight of 70 kg as default for the adult population as described in the EFSA Scientific Committee Guidance document (EFSA, 2012a).

Dietary exposure to phosphates from their use as food additives was estimated combining food consumption data available within the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database with the maximum levels according to Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/200812. Reported use levels and analytical data submitted to EFSA following a call for data were used to assess exposure under different scenarios(see Section 3.3.1). Uncertainties on the exposure assessment were identified and discussed.

Dietary exposure for infants (0–16 weeks) from infant formula and from foods for special medical purposes (FSMP) was calculated based on the minimum and maximum content as defined in the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/127 and Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/128, as well as Commission Directive 2006/141/EC and Commission Directive 1999/21/EC and the reference values on the energy requirements of infants in the first months of life (EFSA NDA Panel, 2013, 2014).

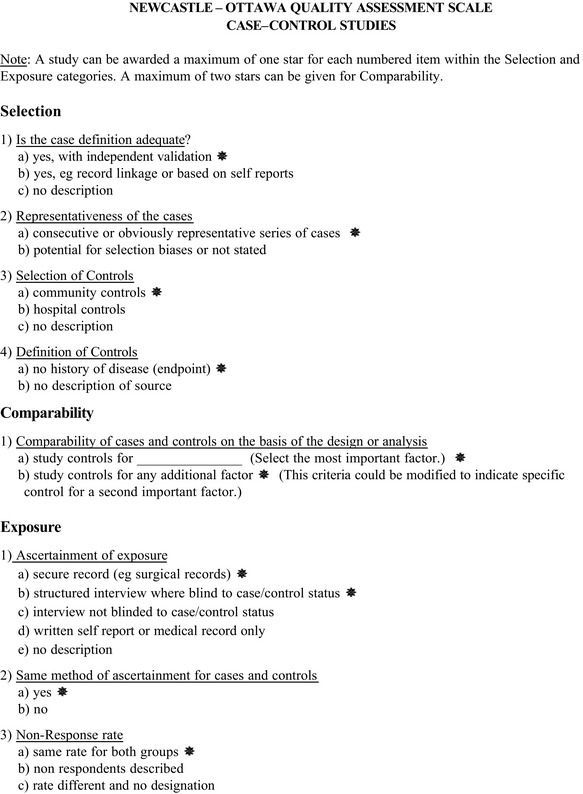

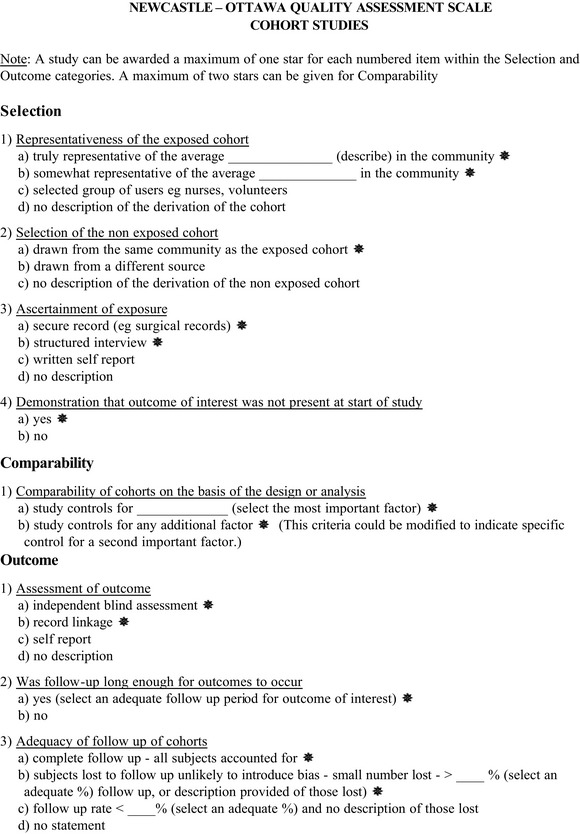

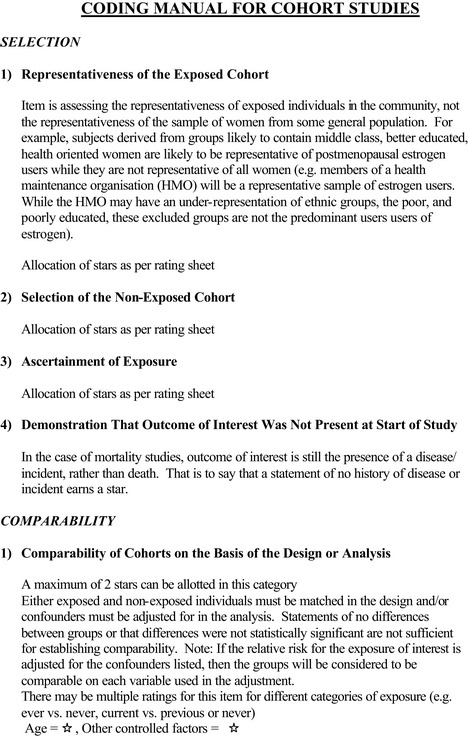

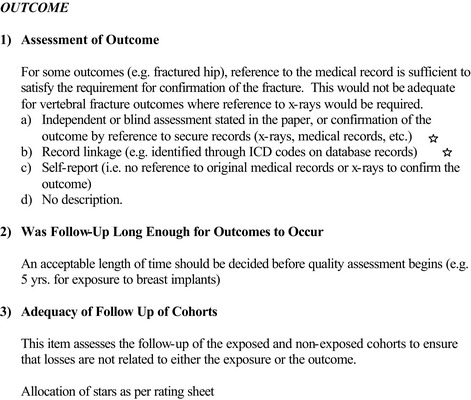

For the assessment of epidemiological studies, a systematic approach has been taken and the protocol is provided in the Appendixes C and D. In addition, the answers received in response to the Public Consultation have been considered for the interpretation of the epidemiology studies. It should be noted that because this opinion is dealing with general population, studies focussing on subpopulations with specific health conditions (e.g. patients with moderate to severe decreased renal function) were not considered.

3. Assessment

3.1. Technical data

3.1.1. Chemistry of phosphates

All phosphorus oxoacids and anions have POH groups in which the hydrogen atom is ionisable (Cotton and Wilkinson, 1972). The principal acid is orthophosphoric acid and its various anions. The phosphate ion carries a −3 formal charge and is the conjugate base of the hydrogen phosphate ion, HPO4 2−, which is the conjugate base of H2PO4 −, the dihydrogen phosphate ion, which in turn is the conjugate base of H3PO4, phosphoric acid. Linear polyphosphates are salts of the anions of general formula [PnO3n+1](n+2)−. Examples are MI 4P2O7, (where M represents the associated cation) diphosphate (also named pyrophosphate), and MI 5P3O10, a tripolyphosphate. Cyclic phosphates are salts of anions of general formula [PnO3n+1]n−. Examples are M3P3O9, a trimetaphosphate, and M4P4O12, a tetrametaphosphate.

The sodium, potassium and ammonium orthophosphates are all water‐soluble. Most other phosphates (including magnesium and calcium) are only slightly soluble or are insoluble in water. As a rule, the hydrogen and dihydrogen phosphates are slightly more soluble than the corresponding non‐hydrogenated phosphates. The pyrophosphates are mostly water‐soluble. Aqueous phosphate exists in four forms: in strongly basic conditions, the phosphate ion (PO4 3−) predominates. Phosphoric acid is tribasic: at 25°C, pK1 = 2.15, pK2 = 7.1 and pK3 ≅ 12.4. In weakly basic conditions, the hydrogen phosphate ion (HPO4 2−) is prevalent. In weakly acidic conditions, the dihydrogen phosphate ion (H2PO4−) is most common. In strongly acidic conditions, trihydrogen phosphate (H3PO4) is the main form. H3PO4, HPO4 2− and H2PO4− behave as separate weak acids because the successive pK values differ by more than 4. The region in which the acid is in equilibrium with its conjugate base is defined by pH ≈ pK ± 2. Thus, the three pH regions are approximately 0–4, 5–9 and 10–14.

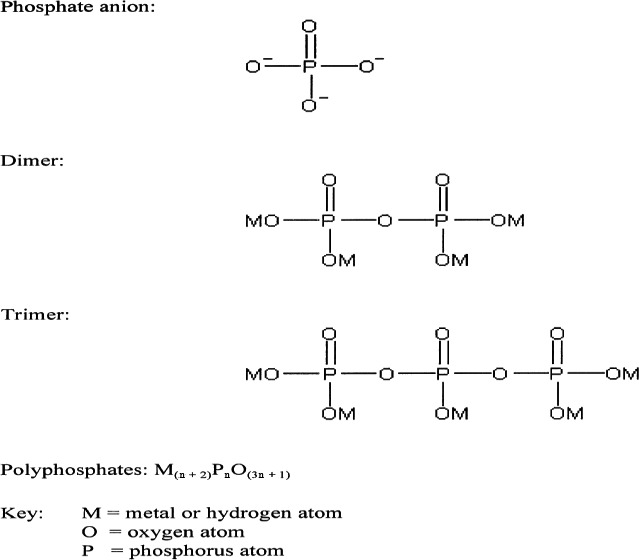

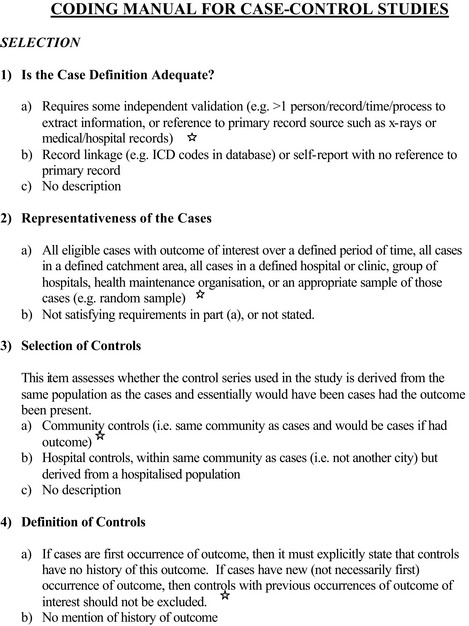

A general structural formula of basic structure of ortho and condensed phosphates is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of basic structure of ortho‐ and condensed phosphates taken from Weiner et al. (2001)

Annex 1 of EU 1333/2008 describes the range of additive functional classes which have been summarised in Appendix A for phosphates as described in JECFA Monographs (JECFA, 2018).

Organic phosphates in different forms are also present in the diet and differ considerably in the physico‐chemical and physiological properties from inorganic phosphates.

3.1.2. Specifications

The identity of substances description and specifications for phosphates as defined in the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 and by JECFA are listed in Appendix E.

The Panel noted that, according to the EU specifications for phosphates impurities of elements arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury are each permitted up to a concentration of 1 mg/kg. Contamination of phosphate additives at such levels could have a significant impact on the exposure to these metals, for which the exposure already are close to the HBGVs or benchmark doses (lower confidence limits) established by EFSA (EFSA CONTAM Panel, 2009a,b, 2010, 2012a,b,c, 2014).

The Panel noted that in EU specifications for E 343(i) the chemical name monomagnesium dihydrogen monophosphate has to be corrected.

When considering the information submitted by the industry on the actual aluminium content in infant formula (final food), the Panel noted that the amount of aluminium may result in an exceedance of the respective tolerable weekly intake (TWI) (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 2,3,4,5).

The Panel noted that the use of calcium phosphate (E 341), for which maximum limits for aluminium have been set in the EU specifications, can contribute to the total aluminium content in infant formula.

3.1.3. Particle size

Industry (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 6) provided information on the particle size distribution (volume‐based (Dv) values) of calcium dihydrogen phosphate (E 341(i)) (n = 3), calcium hydrogen phosphate (E 341(ii)) (n = 6), tricalcium phosphate (E 341(iii)) (n = 7), dimagnesium phosphate (E 343(ii)) (n = 2) and calcium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(vii)) (n = 2) analysed by five laboratories using dynamic light scattering (DLS). One of the laboratories indicated that the sample feeding took place by vibrating plate. The lower Dv50 values were reported for six out of the seven samples of E 341(iii) (around 5 μm) while for the other sample the Dv50 value range from 33 to 92 μm (STD = 22). The major difference in the Dv50 value was observed between the two analysed samples for (E 343(ii)), for one was around 7 μm (STD = 0689) and for the other ranged from 152 to 196 μm (STD = 18).

Additional information of the analysis of other samples of calcium dihydrogen phosphate (E 341(i)) (n = 3), calcium hydrogen phosphate (E 341(ii)) (n = 5), tricalcium phosphate (E 341(iii)) (n = 6), dimagnesium phosphate (E 343(ii)) (n = 3) and calcium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(vii)) (n = 3) by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and DLS was submitted (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 7). Median minimum Feret diameter values were reported among other parameters for SEM and TEM.

The lower median minimum Feret diameter values were reported for E 341(iii) (ranged from 2 to 7 μm) using SEM. A big variability on the median minimum Feret diameter values was observed between the analysed samples of E 341(i) (ranged from 3 to 150 μm) using SEM. Similar observations were noted for the results reported by TEM. Before the microscopic analyses, the samples were applied at the adhesive carbon tape by gently tapping of the SEM stub with the applied adhesive tape on top of the appropriate sample. According to the authors, this approach allowed them to observe the particles and their aggregates/agglomerates in the native form.

SEM imagines were post‐processed considering a uniform rectangular grid (49–196 nodal points) and only the particles or particles aggregates/agglomerates in the nodal‐points were analysed. The Panel noted that the point counting methodology tends to give biased results since large particles have more chance to be selected for measurement than the small. In addition, for some samples magnification should be higher to allow precise measurement.

As indicated in the report, in the TEM images only the particles with well detectable boundaries were analysed. The Panel noted that the magnification used did not allow to identify if there are or not smaller particles.

The same samples were analysed by DLS and number‐based (Dn) values were reported (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 6). Dn10 values for some of the samples of E 341(ii), E 341(iii), E 343(ii) and E 450(vii) were around 140 nm.

Based on the available information, the Panel cannot exclude that particles in the nanorange can be present in phosphates when used as a food additive.

3.1.4. Manufacturing process

Information was submitted by CEFIC – Phosphoric Acid and Phosphates Producers Association (PAPA) in response to the public call for data.

Phosphoric acid and salts

Phosphoric acid is produced commercially by two main methods, either a wet process or an electrothermal process. In the wet process, phosphate rock is digested with a mineral acid (usually sulfuric acid, but nitric or hydrochloric acids may also be used). A filtration step then separates the ‘wet’ phosphoric acid from the insoluble calcium sulfate slurry. As variable amounts of inorganic impurities may be present depending on the origin of the phosphate rock the phosphoric acid is purified through a solvent extraction purification process to produce the food‐grade additive. In the electrothermal process, the phosphate rock, coke and silica are first heated in an electric resistance furnace to more than 1,100°C to extract elemental phosphorus from the ore. The elemental phosphorus is then oxidised to P4O10 (phosphorus pentoxide) and subsequently hydrated and the mist is collected. This process produces a high‐purity orthophosphoric acid due to the use of pure phosphorous for combustion and only the impurity arsenic needs to be removed in an additional purification step involving treatment with excess hydrogen sulfide and filtration of the precipitate (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 8).

Calcium and magnesium phosphates are produced commercially from phosphoric acid and either calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide, and either magnesium oxide or magnesium hydroxide, respectively. The raw materials are mixed together and the product is separated via centrifugation or filtration. The product is a solid that undergoes further physical treatment (drying, milling, sieving) before being passed through a metal detector and then packaged (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 9,10). No further information on purity requirements for the Ca and Mg containing starting materials were provided.

Both mono‐ and disodium phosphates are prepared commercially by neutralisation of phosphoric acid using sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide. Crystals of a specific hydrate can then be obtained by evaporation of the resultant solution within the temperature range over which the hydrate is stable. For the preparation of trisodium phosphate, sodium hydroxide must be used to reach the high pH because carbon dioxide cannot be stripped readily from the solution above a pH approaching 8. Similarly, the potassium phosphates are produced by successive replacement of the protons (H+) of phosphoric acid with potassium ions.

Diphosphates

The three sodium diphosphates are produced commercially by the neutralisation of phosphoric acid with sodium hydroxide. Solutions of the two reagents are mixed in the required proportions for the specific product (1:1 sodium hydroxide:phosphoric acid for E 450(i); 3:2 for E 450(ii); and 2:1 for E 450(iii)). After reaction, the solution is filtered to remove insoluble impurities. The solution is spray‐dried or passed through a rotary kiln or drum dryer. Temperatures greater than 200°C are used; as well as evaporating the water, this temperature promotes a condensation reaction between phosphate groups to produce the diphosphate. The solid material produced is milled, sieved or ground, passed through a metal detector and packaged. Information on manufacturing of tetrasodium diphosphate (E 450(iv)) is missing.

Tetrapotassium diphosphate is manufactured in a similar way, using potassium hydroxide and phosphoric acid. A higher temperature of 350–400°C is used to dry the product and promote the condensation of phosphate groups. The solid product is processed in the same way as described above.

Dicalcium diphosphate is produced from anhydrous dicalcium phosphate (calcium hydrogen phosphate, CaHPO4). The dicalcium phosphate is calcined in a drum drier, rotary kiln or kneader drier at 350–400°C, under which conditions a condensation reaction occurs between phosphate groups. The coarse granules formed are milled, sieved, passed through a metal detector and bagged.

Calcium dihydrogen diphosphate is made in a similar way to the above, but the starting material is monocalcium phosphate (Ca(H2PO4)). This is calcined in a drum drier, rotary kiln or kneader drier at 270–350°C, where condensation between phosphate groups occurs. The solid product is treated in the same way as described in the above paragraphs.

Magnesium dihydrogen diphosphate (E 450(ix)) is manufactured by adding an aqueous dispersion of magnesium hydroxide slowly to phosphoric acid, until a molar ratio of approximately 1:2 (Mg:P) is achieved. The temperature is held at 60°C during the reaction. Approximately 0.1% hydrogen peroxide is added and the resulting slurry is heated and milled (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 7).

Triphosphates

Pentasodium triphosphate and pentapotassium triphosphate are produced commercially by the neutralisation of phosphoric acid with sodium or potassium hydroxide, respectively. The neutralised mixture is dried via spray‐drying or by being passed through a drum dryer or rotary kiln at temperatures above 250°C. The phosphate produced (di‐, tri‐ etc) depends on the degree of neutralisation and the temperature and residence time in the dryer or kiln. The coarse granules formed are usually milled, sieved, passed through a metal detector and then bagged.

Polyphosphates

The thermal dehydration of monosodium phosphate can give a number of condensed polyphosphates. The particular products formed depend on the conditions used – temperature, water vapour and tempering. Heating NaH2PO4 to above 620°C and quenching rapidly gives Graham's salt, a water‐soluble polyphosphate glass with a composition of (NaPO3)x (where x = 4–1.1). The glass consists of around 90% high molecular weight polyphosphates, with the rest being made up of various cyclic metaphosphates. In contrast, the dehydration of NaH2PO4 at 260–300°C produces the low temperature form of Maddrell's salt, (NaPO3)n – III, insoluble metaphosphate III. Further heat treatment of this at 360–430°C produces a second form of Maddrell's salt, insoluble metaphosphate II (also (NaPO3)n). The potassium compound, Kurrol's salt, is similarly obtained by thermal dehydration of KH2PO4. No information on manufacturing of E 452(iii) sodium calcium polyphosphate and E 452(iv) calcium polyphosphate.

3.1.5. Methods of analysis in food

Introduction

A variety of analytical methods have been used for the determination of phosphate additives in foods and beverages. So‐called ‘classical’ methods are generally only useful for total phosphate but have been modernised for current applications in some areas. Modern methods such as ion chromatography (IC), capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) can separate, identify and quantify different phosphate types but are not be able to differentiate between added and naturally occurring phosphates. Moreover, most methods suffer from lack of information on natural variation of phosphate levels where only a few useful but limited reviews are available.

Plasma spectrometry is a useful tool for the estimation of the total phosphorus content. Upon comparing IC with direct current plasma spectrometry (DCP), IC can only provide information on ionic phosphates while DCP can allow the determination of all forms of phosphorus. However, a combination of the two techniques can provide a powerful tool for separating, identifying and measuring all forms of phosphorus (Urasa and Ferede, 1986).

The measurement of added phosphates in food products is not straightforward due to the presence of several types of phosphate additives (i.e. poly, tri‐, pyro‐, orthophosphates). The quantification of phosphate alone cannot be used to verify the presence of added phosphates due to the presence of naturally occurring phosphates and other phosphorus‐containing components such as phospholipids and phosphoproteins. For example, there is ca. 0.1–4.8% naturally occurring phosphates in seafood (Campden, 2012); hence, there is a need to distinguish between natural phosphates, which are not well defined, and added phosphates. In addition, there is the issue of stability since polyphosphates are readily hydrolysed to pyrophosphates and (eventually) to orthophosphates due to phosphatase activity (temperature‐dependent), processing conditions and during analysis (Scharpf and Kichline, 1967; Das et al., 2011; Campden 2012).

Extraction procedures for phosphates are sample‐specific and therefore vary across foods and beverages permitted to contain phosphate additives. Certain extraction conditions (e.g. acids) can also promote the degradation of polyphosphates to orthophosphates.

Indirect methods

Indirect methods for estimation phosphate content are essentially restricted to moisture content and protein content. The ratios of moisture:protein and phosphate:protein can provide useful information on added phosphates. However, the moisture contents of foodstuffs vary greatly and protein measurement relies on the use of interim nitrogen factors following Kjeldahl analysis. While these methods can show when phosphates and/or water have been added, their accuracy is questionable due to natural variation in phosphate content of foodstuffs (Campden, 2012).

Direct methods

Phosphate may be determined in meat samples using digestion with a mixture of hydrochloric and nitric acids, followed by filtration and treatment with quimociac reagent to form precipitates of quinolinium phosphomolybdate, which are then filtered, washed, dried and quantified gravimetrically (USDA, 2009).

Spectrophotometric methods

Direct analysis of phosphate in foodstuffs is commonly carried out using spectrophotometric (colorimetric) methods, e.g. by measuring the intensity of colour resulting from the interaction of orthophosphates with reagents such as molybdenum blue, yellow vanamolybdate complex and malachite green (Þórarinsdóttir et al. (2010); Campden, 2012). Colorimetric analysis requires the decomposition of poly‐, tri‐ and other forms to orthophosphates achieved through the use of strong acids such as trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). The total phosphate content is usually expressed as P2O5 and therefore does not distinguish between different classes of phosphate additive. A spectrophotometric method has been developed that is able to distinguish between phosphorus due to water‐soluble (i.e. inorganic) from organic phosphorus sources such as phospholipid and phosphoprotein (Cupisti et al., 2012). An adaptation of this method can be used to distinguish between orthophosphate and condensed polyphosphates (Þórarinsdóttir et al., 2010). The condensed forms react much more slowly, so measurements are made at 15 and 90 min and the difference between the results is the amount of the condensed forms. The method described above cannot distinguish between the di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates.

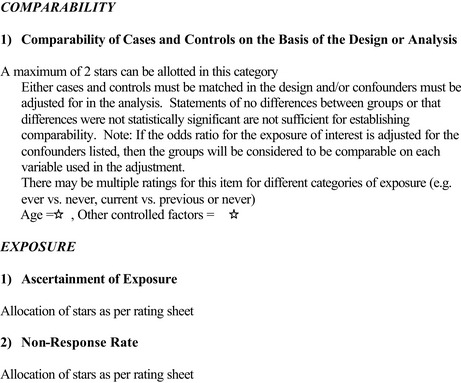

Modern spectrophotometric methods have good sensitivity and precision, which is important because of the natural variation in total phosphates content in foodstuffs. McKie and McCleary (2016) developed and validated a novel and rapid method for the determination of total phosphorus and phytic acid in foods and animal feeds. The method involves the extraction of phytic acid followed by dephosphorylation with phytase and alkaline phosphatase, and measured colorimetrically using a modified molybdenum blue assay. Such methods are used for determining the phosphate content of fertilisers and for assessing the purity of phosphate food additives (JECFA, 2018; EU, 231/2012). The Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) method describes a standard colorimetric method for the determination of orthophosphate in water (AOAC, 1997). Method details are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reference methods listed by BVL (2018) and available standard methods

| E number(s) | Method number, name, origin | Analyte(s) | Analytical technique | Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BVL methods | ||||

| 450–452 | L 06.00‐15L 07.00‐20L 08.00‐22 | Condensed phosphates | Thin‐layer chromatography | Meat, meat products, processed meats, bakery wares |

| 450–452 | L 06.00‐9 | Di‐, Tri‐, Poly‐ Phosphate | Spectrophotometry | Foodstuff, e.g. meat products, fish products, dairy, bakery products, grain‐based foods |

| 450(i–vii) | L 06.00‐15ISO‐Norm 5553 | Diphosphate | Thin‐layer chromatography | Dairy, meat products, fish products |

| 451(i, ii) | L 06.00‐15ISO‐Norm 5553 | Triphosphate | Thin‐layer chromatography | Dairy, meat products, fish products |

| 452(i–iv) | L 06.00‐15 mod. Iso‐Norm 5553(qualitative)L 06.00‐09 mod. (quantitative) | Di‐, Tri‐, Poly‐ Phosphate | Thin‐layer chromatography Spectrophotometry | Meat products, dairy (cheese, processed cheese), fish products |

| 338–341, 343,450–452 | Photometric determination of phosphate after acid digestion in drinks | Total phosphate as PO4 | Spectrophotometry | Soft drinks |

| 338–341, 343,450–452 | L 06.00‐9 | Total phosphate as P2O5 | Spectrophotometry | Meat, meat products, cheese, dairy |

| 338–343, 450, 451 | Condensed phosphatesL 06.00‐15 | Condensed phosphates | Qualitative chromatography | Meat and meat products |

| 338–343, 450, 451 | Total phosphorus contentL 06.00‐9 | P2O5 | Spectrophotometry | Meat and meat products |

| 338–343, 450, 451 | Total phosphorus contentL 03.00‐17 | Phosphorous | Spectrophotometry | Cheese, processed cheese, processed cheese preparations |

| 339(i–iii) | L 06.00‐15 mod | Triphosphate | Thin‐layer chromatography | Fish products |

| 340(i–iii) | Not specified | Phosphoric acid | Ion chromatography | Soft drinks |

| 338 | L 31.00‐6 | Phosphate | Spectrophotometry without ashing | Soft drinks |

| Other standard methods/norms | ||||

| BSI 4401‐15:1981/ISO 5553;1981. Methods of test for meat and meat products. Detection of polyphosphates (by spectrophotometry) | ||||

| PD ISO/TS 18083:2013. Processed cheese products. Calculation of content of added phosphate calculated as phosphorus (by spectrophotometry) | ||||

| AOAC, 1997. Standard colorimetric method for the determination of orthophosphate in water (by spectrophotometry) | ||||

Chromatographic methods

Thin‐layer chromatography (TLC) methods for determining phosphates are relatively simple and cheap and can separate poly‐, tri‐, pyro‐ and orthophosphates. Quantitative estimates of phosphates content can be achieved by comparing colour intensities of spots with standard phosphate solutions. The main disadvantage of TLC is the hydrolysis in situ of phosphates during sample extraction and analysis (Campden, 2012). Without additional analysis, TLC is essentially a qualitative technique and it has been shown that false‐negative results can arise. For example, where polyphosphates have completely hydrolysed to orthophosphates and are no longer detectable as a distinct species, while similar observations during the TLC analysis of white shrimp, where the limit of detection was estimated at 0.08% (w/w) sodium triphosphate (Campden 2012).

High‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), or more accurately IC, has been shown to be a useful method for the determination of individual polyphosphates and other phosphate species. IC can separate and quantify poly‐, tri‐, pyro‐ and orthophosphates. Post‐column colorimetric and conductivity detection can be used to provide sensitive and selective performance with good linear range. IC methods can be used for the simultaneous determination of condensed phosphates including orthophosphates (P1), diphosphates (P2) and polyphosphates (P3 and greater).

Examples of the application of IC in fish, shellfish and crustacea may be found in Campden (2012). A similar methodology has been used IC has been used to determine phosphate species in sausage (Dionex 2010) and for the determination of polyphosphates in fish, shrimp and cuttlefish, and on commercial products of cooked ham, wurstel, corned beef, processed cheese and fish (Iammarino and Di Taranto, 2012). IC has been used recently for the rapid and automated determination of orthophosphate in carbonated soft drinks (De Borba and Rohrer, 2018). Method details are summarised in Table 1.

Electrophoretic methods

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is a family of related techniques used to separate charged particles based on their size to charge ratio when an electric current is applied (Campden, 2012). The most commonly used technique is capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE), where separation is based on differences in solute size and charge at a given pH. In capillary isotachophoresis (cITP), samples are loaded into a capillary set between two electrolytes (leading and terminating), whereupon the analytes are separated into discrete zones between the electrolytes according to their electrophoretic mobility. Both techniques, either alone or in combination, have been used to detect added phosphates in foodstuffs. Detection techniques include conductivity, fluorescence or ultraviolet (UV). CZE/cITP with conductivity detection has been used to determine phosphate in meat, canned meat products, ham, smoked ham, sausages, paté, prawns, squid and mixed seafood (Jastrzębska, 2009, 2011; Campden 2012). Method details are summarised in Table 1. The clear advantages of using CZE/cITP methods is that they can determine different phosphate species (ortho, di‐ and tri‐) simultaneously and rapidly, requiring a relatively small amount of sample. While results have been reported to be sensitive, accurate and precise the importance of robust sample preparation is requisite. Sample inhomogeneity and the presence of protein and fat can decrease method precision.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

31P NMR has been used generally as a research tool rather than as a routine analytical procedure but this technique is becoming more widely available and affordable. 31P NMR can differentiate simultaneously between different phosphate types and is quantifiable. It has been applied to fish and meat products with adequate sensitivity (Campden, 2012). Method details are summarised in Table 1. The results obtained by 31P NMR are reported to more accurate and precise compared to those obtained using the molybdovanadate yellow spectrophotometric method (Szłyk and Hrynczyszyn, 2011).

The issue of polyphosphate degradation notwithstanding, non‐destructive, simultaneous observation of different phosphate species is clearly an analytical advantage. Moreover, 31P NMR it has been used to measure total phosphates or polyphosphates but cannot be used to distinguish between natural and added compounds.

Ion chromatography

Upon comparing IC with DCP, IC can only provide information on ionic phosphates while DCP can allow the determination of all forms of phosphorus. However, a combination of the two techniques can provide a powerful tool for separating, identifying and measuring all forms of phosphorus (Urasa and Ferede, 1986).

Other methods

Much less widely used techniques for phosphate determination include thermal differential photometry and microwave dielectric spectroscopy, which are essentially research tools that are not readily applicable to routine analysis of foodstuffs. X‐ray fluorescence has also been used (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 7) although is not a widespread technique.

Standard methods and norms

There are few validated official methods available. Those identified to date are summarised with standard methods listed by BVL (2018) in Table 1. The scope of these methods covers ortho‐, condensed and polyphosphate analytes, and most foodstuffs and beverages apart from those for infants (e.g. infant formula). Analytical techniques are essentially limited to TLC and/or spectrophotometry, except for IC which is specified for the analysis of soft drinks. Data provided by CEFIC‐PAPA provide evidence for the accuracy and precision requirements of standard methods for phosphate determination. For example, the total phosphorus is calculated as g/100 g reported to two significant figures (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 11).

The scope of methods for the determination of phosphates in foodstuffs must cover the complete range of foods and beverages permitted to contain phosphate additives and must be readily applicable in laboratories, i.e. not unnecessarily complex or costly.

While quantitative spectrophotometric methods provide sufficient sensitivity and ease of use, they are limited in scope to the detection and measurement of phosphates in the ortho form, i.e. di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates must be hydrolysed first to orthophosphates. Hydrolysis may be achieved chemically and/or enzymatically but it will not be possible to discriminate between phosphates present naturally and phosphate additives (however, the latter are likely to be present at a much higher concentration relative to natural phosphates). Published spectrophotometric methods therefore require further development to encompass all foodstuffs within the required scope, especially with respect to extraction and isolation techniques.

Since spectrophotometric methods cannot be used qualitatively to identify different phosphate additive species, the use of more sophisticated techniques that can separate, identify and quantify different phosphate species is required. Of the available methods, IC is the most widely used but to date, has not been applied to the full range of foodstuffs permitted to contain phosphate additives. For the simultaneous determination of condensed phosphates using IC, systems employing a mobile phase comprising KOH (or NaOH) and macroporous divinyl benzene/ethylvinyl benzene stationary phase run under gradient elution conditions with suppressed conductivity detection, are the most widely reported. In order to reduce the reporting of false positive and/or false negative results, it is recommended that sample preparation times should be as short as possible and should include steps to deactivate phosphatase enzymes.

Appropriate analytical methods must be developed and validated to recognised international protocols so that they are fit for purpose with respect to expected phosphate concentration ranges (i.e. ranging from ca. 500 to 50,000 mg/kg, as well as quantum satis). Some foodstuffs have ‘no limit defined’. There should also be clear distinction between methods for total phosphate and methods for identifying and quantifying separate phosphate types, i.e. methods must be robust, and the units used for reporting phosphate content should be standardised.

There is a clear inconsistency in the reporting of levels of phosphates in food products (as well as in serum and urine), due largely to the form in which the results are expressed. Historically, phosphorus content has been expressed in terms of mg P2O5/100 g, which is usually applied to determination of total phosphorus and phytic acid in fertilisers, which allows for normalisation of P content across a range of products comprising different mixtures of phosphates. It is also applied to some foods and animal feeds. Other (particularly clinical) studies report phosphorus levels as mg P/kg. Modern analytical methods tend to report P content as mg/kg total phosphate or where possible as mg/kg individual ortho‐, pyro‐ or polyphosphates.

In order to fulfil the requirements of EU regulation EU 1333/2008 with regard to the presence and maximum levels of phosphates, it is recommended that analytical results are expressed as either total phosphates (P3O4 3− irrespective of counter ion), or in terms of the individual phosphate species, as mg/kg.

Literature sources show that spectrophotometry has been established as a reliable technique for the determination of total phosphate in foodstuffs. Similarly, IC has been applied successfully to a limited range of foodstuffs for the simultaneous determination of different phosphate additive species. The Panel noted the need for development of analytical methods since those currently available for total phosphate and phosphate speciation do not cover the entire range of foodstuffs permitted to contain phosphate additives.

3.1.6. Stability of the substance and fate in food

No information was identified in the literature on the reaction and fate of phosphoric acid or its calcium and magnesium salts in food. Phosphoric acid is soluble in water and is expected to dissociate in beverages and fresh food to phosphate and H+ ions. No information was identified in the literature on the reaction and fate of sodium and potassium phosphates in food. Since sodium and potassium phosphates are freely soluble in water they are expected to be dissolved in beverages and fresh food to phosphate and the respective cations.

Phosphoric acid and its sodium and potassium salts dissociate readily after being added to foods and beverages, thereby affecting its technological function as an acidity regulator (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 8), whereas calcium and magnesium phosphates require solubilisation under acidic conditions (Documentation provided to EFSA n. 9,10).

The effects of phosphates in general on the colour and quality of salted fish are summarised by Þórarinsdóttir et al. (2010). Yellowing of the fish due to oxidation reduces the commercial quality. Positive effects of phosphates on colour and the commercial quality of the fish (by maintaining the natural colour of the fish) are thought to be due to reduced oxidation, which is brought about by the sequestering action of the phosphates on metals present in the salt used.

The addition of sodium phosphates to meat has been shown to have antioxidant effects that decrease the rate of oxidation of lipids in meat (Miller, 2010). Di‐, tri‐ and higher phosphates are susceptible to the action of phosphatase enzymes, in particular during extraction from food or biological samples when they can be converted into monophosphates. Das et al. (2011) used Zn(II) and Cd(II)‐based complexes to bind with tetrasodium diphosphate in order to investigate the activity of alkaline phosphatase in physiological conditions. Allen and Cornforth (2009) describe the iron‐binding activity of sodium tripolyphosphate in a lipid‐free model system. At concentrations of 1 and 0.05 mg/mL, 88% and 21%, respectively, of the added iron was bound. This activity was considered to be the basis for the antioxidant effect of sodium tripolyphosphate. Weilmeier and Regenstein (2004) added sodium polyphosphate to mackerel samples and observed an antioxidant effect, although this was not as strong as the effect with propyl gallate, ascorbic acid or erythorbic acid. Jin et al. (2011) purified and characterised the tripolyphosphatase responsible for the hydrolysis of tripolyphosphates in rabbit psoas major muscle tissue.

Polyphosphates

All polyphosphates (also referred to as condensed phosphates) are subject to hydrolytic decomposition (reversion) when in solution. The rate of decomposition is affected by:

Temperature

pH (generally < 7 or > 11)

Multivalent metal ions, e.g. Ca2+, Fe2+

Concentration at mg/L level, since as the concentration increases, the reversion rate decreases

Phosphatase enzymes

Phosphate species.

It is generally accepted that pyrophosphate is the most stable, followed by tripolyphosphates. During hydrolysis of the longer chain phosphates, shorter chains as well as orthophosphates are formed. Among the shorter chains formed are pyrophosphates. Research suggests that when the pyrophosphate concentration increases, due to hydrolysis of higher polyphosphates, the rates of reversion diminish. It may be that an equilibrium is established between the higher condensed phosphates and their hydrolysis products.

Scharpf and Kichline (1967) showed that following the addition of long‐chain sodium polyphosphate to cheese extracts in which the natural alkaline phosphatase activity was high, the concentration and distribution of phosphate species remained unchanged after storage at 3–7°C for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks storage at 20°C, the concentration of the long‐chain species decreased from 89% to 64%, whereas the concentration of the orthophosphate species increased from 4% to 27%.

In a conservative review of polyphosphate breakdown and stability (Campden, 2012) it was reported that:

Most polyphosphates added to food are broken down to orthophosphate units in the stomach and may be significantly hydrolysed to orthophosphates during storage and cooking.

After 2 weeks of frozen storage, only 12% of the total phosphorus in uncooked shrimp muscle corresponded to the tripolyphosphate added. After ten weeks, the phosphorus levels corresponded to 45% orthophosphate. This was considered to be due to natural rather than heat‐induced hydrolysis.

At elevated temperatures, such as in steam cooking, sodium tripolyphosphate will hydrolyse rapidly to orthophosphates.

Samples of three different commercially available cooked shrimp products treated with tripolyphosphate and stored frozen for 11 months, showed that the total polyphosphate was 87%, 89% and 103% of the original levels, indicating that very little hydrolysis occurred.

The stability of polyphosphates in fish and shrimps under various treatment and storage regimen was reported by Campden (2012). Samples were either untreated or treated and analysed after 0, 1, 2 and 3 days storage. The relative level of polyphosphate (expressed as P2O5) in raw shrimps was reduced from 1,500 mg/kg to 0 mg/kg after 4 days due to phosphatase activity. Conversely, no polyphosphate degradation was observed in cooked shrimp treated with polyphosphate (at 2,600 mg/kg) after cooking, indicating heat‐induced phosphatase deactivation during cooking.

The addition of sodium phosphates to meat has been shown to have antioxidant effects that decrease the rate of oxidation of lipids in meat (Miller, 2010). Di‐, tri‐ and higher phosphates are susceptible to the action of phosphatase enzymes, in particular during extraction from food or biological samples when they can be converted into monophosphates. Campden (2012) report that flash heat treatment with a microwave oven can be used to avoid this.

The impact of high temperature treatments of on the composition of polyphosphates with regard to phosphate chain length in aqueous solutions in the presence and absence of calcium ions has been reported by Rulliere et al. (2012). Treatment at 120°C for 10 min led to the hydrolytic degradation of long‐chain polyphosphates into orthophosphate and trimetaphosphate, whereas heating the salts to 100°C in aqueous solutions had little effect on composition. The presence of calcium ions increased the rate of hydrolysis of long‐chain phosphates leading to increased amounts of trimetaphosphate and pyrophosphate end products. The evolution of emulsifying salts composition under heat treatment was reported to lead to modification of their chelating properties since short‐chain phosphates are less efficient at chelating calcium than long‐chain phosphates.

3.2. Authorised uses and use levels

Maximum levels of phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) have been defined in Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/200813 on food additives, as amended. In this document, these levels are named maximum permitted levels (MPLs).

Currently, phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) are authorised food additives in the EU with MPLs ranging from 500 to 20,000 mg/kg expressed as P2O5 in 104 authorised uses and at quantum satis (QS) in four. The 108 different uses and use levels are corresponding to 65 different food categories. Table for converting phosphates into P2O5 and P is in Appendix B.

Table 2 summarises the food categories with their restrictions/exceptions that are permitted to contain added phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) and the corresponding MPLs as set by Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008.

Table 2.

MPLs of phosphates (E 338–341, E 343, E 450–452) in foods according to the Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008

| Food category code | Food category name | Restrictions/exceptions | E‐number | Name | MPL (mg/L or mg/kg as appropriate) | Footnotes (as in Reg (EC) No 1333/2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Food additives permitted in all categories of foods | Only foods in dried powdered form (i.e. foods dried during the production process, and mixtures thereof), excluding foods listed in table 1 of Part A of this Annex | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 10,000 | 1 , 4 , 57 |

| 01.1 | Unflavoured pasteurised and sterilised (including UHT) milk | Only sterilised and UHT milk | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 1,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.4 | Flavoured fermented milk products including heat‐treated products | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 3,000 | 1 , 4 | |

| 01.5 | Dehydrated milk as defined by Directive 2001/114/EC | Only partly dehydrated milk with less than 28% solids | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 1,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.5 | Dehydrated milk as defined by Directive 2001/114/EC | Only partly dehydrated milk with more than 28% solids | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 1,500 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.5 | Dehydrated milk as defined by Directive 2001/114/EC | Only dried milk and dried skimmed milk | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 2,500 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.6.3 | Other creams | Only sterilised, pasteurised, UHT cream and whipped cream | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 5,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.7.1 | Unripened cheese excluding products falling in category 16 | Except mozzarella | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 2,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.7.5 | Processed cheese | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 20,000 | 1 , 4 | |

| 01.7.6 | Cheese products (excluding products falling in category 16) | Only unripened products | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 2,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.8 | Dairy analogues, including beverage whiteners | Only whipped cream analogues | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 5,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.8 | Dairy analogues, including beverage whiteners | Only processed cheese analogues | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 20,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.8 | Dairy analogues, including beverage whiteners | Only beverage whiteners | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 30,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 01.8 | Dairy analogues, including beverage whiteners | Only beverage whiteners for vending machines | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 50,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 02.2.1 | Butter and concentrated butter and butter oil and anhydrous milkfat | Only soured cream butter | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 2,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 02.2.2 | Other fat and oil emulsions including spreads as defined by Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 and liquid emulsions | Only spreadable fats | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 5,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 02.3 | Vegetable oil pan spray | Only water‐based emulsion sprays for coating baking tins | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 30,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 03 | Edible ices | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 1,000 | 1 , 4 | |

| 04.2.4.1 | Fruit and vegetable preparations excluding compote | Only fruit preparations | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 800 | 1 , 4 |

| 04.2.4.1 | Fruit and vegetable preparations excluding compote | Only seaweed based fish roe analogues | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 1,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 04.2.4.1 | Fruit and vegetable preparations excluding compote | Only glazings for vegetable products | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 4,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 04.2.5.4 | Nut butters and nut spreads | Only spreadable fats excluding butter | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 5,000 | 1 , 4 |

| 04.2.6 | Processed potato products | Including prefried frozen en deep frozen potatoes | E 338–452 | Phosphoric acid–phosphates – di‐, tri‐ and polyphosphates | 5,000 | 1 , 4 |