Abstract

The most significant knowledge gaps in the prevention and control of African swine fever (ASF) were identified by the EU Veterinary services and other stakeholders involved in pig production and wild boar management through an online survey. The respondents were asked to identify the major research needs in order to improve short‐term ASF risk management. Four major gaps were identified: ‘wild boar’, ‘African swine fever virus (ASFV) survival and transmission’, ‘biosecurity’ and ‘surveillance’. In particular, the respondents stressed the need for better knowledge on wild boar management and surveillance, and improved knowledge on the possible mechanism for spread and persistence of ASF in wild boar populations. They indicated the need for research on ASFV survival and transmission from the environment, different products such as feed and feed materials, and potential arthropod vector transmission. In addition, several research topics on biosecurity were identified as significant knowledge gaps and the need to identify risk factors for ASFV entry into domestic pig holdings, to develop protocols to implement specific and appropriate biosecurity measures, and to improve the knowledge about the domestic pig–wild boar interface. Potential sources of ASFV introduction into unaffected countries need to be better understood by an in‐depth analysis of the possible pathways of introduction of ASFV with the focus on food, feed, transport of live wild boars and human movements. Finally, research on communication methods to increase awareness among all players involved in the epidemiology of ASF (including truck drivers, hunters and tourists) and to increase compliance with existing control measures was also a topic mentioned by all stakeholders.

Keywords: African swine fever, Chief Veterinary Officers, control measures, gap analysis, research gaps, risk management

Summary

African swine fever (ASF) has become a major disease of concern for Europe, Asia and Africa due to its economic impact on pig breeding. Being currently present in eastern Europe and Belgium, there is a great concern for further spread within the European Union (EU) to non‐affected Member States (MSs). To design more specific measures for the prevention and control of ASF, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) was asked to identify the main knowledge gaps that currently hamper an effective management of the disease.

Relevant stakeholders involved in the prevention and control of ASF in the EU were identified and an online survey was sent to these players using the ‘EU Survey’ tool. Each interviewee was asked to reflect the three most important priorities to be addressed in their country. The resulting answers were stratified according to the type of stakeholder in the management of ASF and to the epidemiological situation of their country. The answers received reflected the subjective perception of the stakeholders that replied to the questionnaire.

Overall, considering all the answers of all the participants and, regardless the stakeholder group, the categories perceived as major research gaps were ‘wild boar’, ‘African swine fever virus (ASFV) survival and transmission’, ‘biosecurity’ and ‘surveillance’.

In relation to wild boar, the crucial topics suggested for further research and development were: (1) harmonised methods to estimate wild boar population density in an area; (2) the possible correlation between wild boar population density and ASF occurrence; (3) effective methods to reduce the absolute number of wild boar in an area; (4) mechanisms for ASFV spread and persistence in the wild boar population; and (5) the relative importance of direct host‐to‐host transmission (taking into account wild boar behaviour).

With relation to ASFV survival and transmission, it was suggested that: (1) the role of arthropod vectors in ASFV transmission needs to be further investigated; as well as (2) ASFV survival in, and transmission from, a contaminated environment; (3) the potential for transmission through contaminated feed and feed materials; and (4) ASFV survival in, and transmission through, different bedding and forage materials, pork products and fomites.

With relation to improved biosecurity: (1) the identification of the most efficient measures for preventing the introduction of ASF into a country, region or farm was suggested; as well as (2) the need to identify the minimum biosecurity measures needed for different husbandry systems; (3) measures to reduce the risk of transmission between wild boar and domestic pigs; and (4) the possible risk factors for outbreaks of ASF in domestic pig farms.

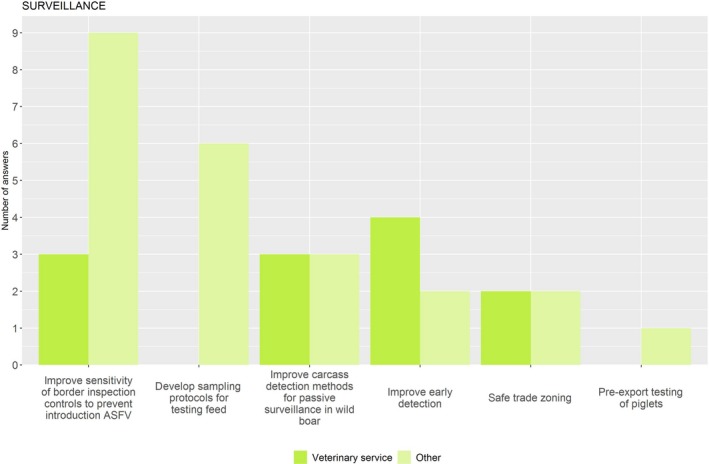

Improved methods to increase surveillance were also considered as a high priority. The following aspects were perceived as important: (1) sensitivity of border inspection controls to reduce the risk of introduction of ASFV; (2) methods for passive surveillance to improve early detection (i.e. methods for improved detection of wild boar carcasses); and (3) sampling protocols and diagnostics (e.g. methods to test feed after the final stage of processing, improved sensitivity of the tests and the development of rapid diagnostic tests able to be performed in the field, such as non‐invasive rapid tests for wild boar sampling).

In addition, especially the Veterinary services indicated the need to identify the source of introduction of ASFV into a new country, this should comprise an analysis of the possible pathways of introduction with special focus on food, feed, transport of live wild boar1 and spread due to movement of people.

Moreover, research on improved communication methods was a topic mentioned by all stakeholders. It included the need to raise awareness among all players involved in the epidemiology of the disease (including truck drivers, hunters and tourists) and to increase compliance with the control measures.

Other topics reported in the questionnaire were: the need for improved disinfection methods and carcass disposal protocols; the development of an international harmonised ASF management structure; and research on the role of low virulent virus strains in the maintenance and transmission of ASF.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

African swine fever (ASF) Genotype II is now (at the moment of receiving the request) present in nine European Union (EU) Member States: Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic,2 Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania. From 2014 to the present time, the disease has been mainly geographically limited to the eastern part of the EU and maintained in the wild boar population along the EU eastern borders followed by occasional spill over to domestic pig holdings.

Member States and the Commission are continuously updating the EU strategic approach to ASF and the related legislation. There is knowledge, legislation, scientific, technical and financial tools in the EU to properly face ASF.

One of the key areas that needs to be addressed more thoroughly is the necessity for new scientific input and joint research activities that will underpin epidemiological analysis and evaluation of mitigation measures to support risk management decisions (to prevent introduction and control the spread of ASF). Different platforms, such as the Global African Swine Fever Research Alliance (GARA) and the STAR‐IDAZ International Research Consortium on Animal Health (IRC), already exist to coordinate research and research projects to generate scientific knowledge (GARA, 2018; STAR‐IDAZ, 2018).

However, the EU needs at this stage also to identify research activities that should be mainly aimed at supporting strategic recommendations and risk management, tackling in particular the identified risk pathways (e.g. human factor and the interface between wildlife and farms). This gap analysis aims to better understand the epidemiological situation in the field and how this obtained knowledge could then be translated into the practical implementation of risk management actions, whereas pure scientific or long‐term objectives (such as vaccination) should not be considered.

It is therefore necessary to review research gaps to identify what research can bring to the risk management of preventive and control measures in the light of the current development of the ASF epidemic, updating and completing previous EFSA scientific opinions.

Therefore, in the context of Article 31 of Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002, EFSA should provide technical and scientific assistance to the Commission based on the following Terms of Reference (TOR):

Review the main ASF research gaps, with the aim to facilitate evidence‐informed decision making on prevention and spread, in particular from an epidemiological and risk management perspective.

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference (if appropriate)

To identify the main research gaps and research needs for the prevention and control of the spread of ASF, in particular from an epidemiological and risk management perspective, the use of an online questionnaire was considered the most appropriate methodology by EFSA's Standing Working group on ASF, given the available timeframe of the mandate. An online survey allowed the anonymous collection of ideas from a large number of important stakeholders involved in the prevention and control of ASF. This method also made it possible to collect the suggestions of stakeholders in non‐managerial positions, but who could play a pivotal role in the prevention and control of the disease, e.g. all sectors related to the pig industry and wild boar management. The answers received were subjective as perceived by the stakeholders invited to fill in the questionnaire and might not reflect research gaps identified by other stakeholders.

It was suggested by the requestor of the mandate to investigate whether the suggested research objectives would differ much between stakeholders, according to the role they play in the prevention and control of the disease, and according to the country or area that the stakeholder represents. It could be expected that stakeholders from areas with a different infection status would have different research priorities.

Given the urgent nature of the threat and the global expansion of ASF, it was envisaged to collect the major gaps of knowledge and research priorities that could help with evidence‐informed decision making in the short term (over the next 12 months). Long‐term research objectives were discarded a priori from the valid answers, e.g. the development of a vaccine, research on other immunisation strategies in domestic pig or wild boar populations, research related to genetic characterisation of the virus (including the use of a multigene family approach), etc. These long‐term research projects were not within the scope of this analysis, but they are nonetheless extremely important.

2. Methodologies

2.1. Online survey

To identify the main perceived research gaps, an online questionnaire was created using the ‘EU Survey’ tool. A sample of the survey is given in Appendix A (Figure A.1). The respondents were asked to present the three most significant priorities and to rank them from most to least important with the idea of making a classification of the results as the final outcome of this scientific report.

Figure A.1.

Screenshot of the questionnaire sent to the participants

An ‘open answer’ style questionnaire was chosen, as this allowed the respondents to freely describe their needs without any kind of conditioning, and did not limit the answers to a close pre‐devised list of options or a biased view that could result from suggesting responses (Reja et al., 2003). By following this method, it was expected to get more information with possible new outlooks on short‐term research objectives for ASF, not considered in previous reports. The replies were expected in a narrative format. The respondents were asked to identify the three most significant knowledge gaps – or priorities – that in their opinion currently hamper the appropriate management of ASF in their country. In addition, the stakeholders were asked to think about prevention, control and/or eradication of ASF in their country, without considering budgetary limitations or resource distribution. The different components of the survey are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Components of the online survey for gap analysis on ASF

2.2. Categorisation of the answers

Amongst the disadvantages of open‐ended questions are the complexity of the analysis, as there might be a need for categorising or coding the answers (narrative text) and a higher risk of non‐accurate responses (e.g. vaccine‐related answers that were not in the scope of this report).

The provided narrative answers were carefully read and cross‐checked by three independent reviewers and a list of the main categories and explanatory subcategories was assigned by every reviewer to each of the answers provided in the open question for priority 1, priority 2 and priority 3. Subsequently, the reviewers merged the three individual lists of categories and subcategories and agreed upon the final list. Then, all the answers were assigned to the agreed list of categories and subcategories (Table 1) by one of the reviewers. In a final stage, the agreed categorisation was validated by the other two reviewers and EFSA's Standing Working group on ASF and the results are shown in Section 3. The approach taken to categorise the answers is given in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Categories and subcategories of research assigned according to the answers provided by the respondents of the questionnaire

| Assigned category | Assigned subcategory | Examples provided by the respondents |

|---|---|---|

| ASFV survival and transmission in: | Excreta, carcasses, soil and/or environment | Wild boar faeces in the forest; leftovers and rests of (infected) carcasses and its surroundings (e.g. hay field, grass & pasture, crop fields); influence of the type of soil and climate conditions |

| Feed | Survival of ASFV in feed, feed additives, feed ingredients, grains, beets; risk of feed produced in affected area; contamination of ingredients during shipment; establish the minimal infective dose for ingredients and complete feed | |

| Pork and pork products | Pork products as a short‐ or long‐distance route of transmission of ASFV; review the effect of transformation processes in the stability of pork products | |

| Predators and scavengers | The role of predators and scavengers in the natural distribution of ASFV at a local and long‐distance scale | |

| Arthropod vectors | The role of flies, mosquitoes, midges, ticks and its new generations | |

| Vehicles and other fomites | Investigate possible mechanical role of fomites such as birds, rodents, survivor carriers, vehicles and humans | |

| Water | Persistence of the virus in rivers, lakes and other open source water; the role of water in spread of ASFV; role of ground water contamination due to buried affected bodies | |

| Different materials | Increase knowledge about unrecognised transmission routes (e.g. packaging materials, bedding materials, etc.) not mitigated by current biosecurity plans and beyond what could be explained by natural transmission, i.e. the outside of cargo packages as they move through outbreak areas | |

| ASFV virulence | Tolerant pig breeds | Identify the ASFV strain/pig breed combination with higher rate of survival for potential animal model experiments in the ASFV vaccine development |

| Less virulent strains | Knowledge of the importance of weak strains or low levels of virus and viral DNA | |

| Biosecurity | Biosecurity protocols | Review the strategies to increase checks/audits and boost internal and external biosecurity in a farm; training on biosecurity adapted to every level (breeders, veterinarians, laboratories, transporters, hunters, general public, etc.); protocols to avoid the introduction of meat products in the farm; extra hygiene measures for vehicles, pigs and people entering the farm; possibility to creating proportional biosecurity measures adapted to different husbandry systems and different areas (e.g. stop the importation of live animals and meat/meat products from the affected areas); apply biosecurity measures in forested, field and areas surrounding the farms |

| Incentives to increase biosecurity | Earmark funds for the control of wild boar population for all European countries (i.e. not only for EU Member States); facilitating farmers to meet biosecurity plans | |

| Interface wild boar/domestic pigs | Knowledge on the transmission cycle between wild and domestic pigs; knowledge on the effectiveness of the biosecurity measures in preventing the spread of disease in wild boar and domestic pigs | |

| Risk factors of ASF occurrence in farms | Study the influence of socioeconomic factors; role of extremely rooted and traditional way of pig farming; role and review the role of human behaviour | |

| Communication | Increase public awareness | Awareness campaigns to educate all players involved in the epidemiology of the disease (farmers, drivers, veterinarians, hunters, trade managers, tourists, general society, etc.); review of risky actions (e.g. transport of pork); review the effect of ASFV on swine populations |

| Increase acceptance or compliance with control measures | Reduce negative reactions from the public towards the preventive measures, such as wild boar culling; enforcement of control measures, such as prohibition of feeding wild boar, and compliance with biosecurity measures by outdoor‐reared‐pig farmers | |

| Clear protocols on control measures adapted to different stakeholders | Develop effective communication strategies and products for decision makers and politicians to support their messages on ASF management; facilitation of exchange of information | |

| Communication between Member States to learn from experience and update on the situation | Exchange of information and data (e.g. estimate of the number of wild boars or ASF epidemiological situation) between MS and non‐EU MS. Optimise communication at the level of areas if there is spread of the disease | |

| Open data exchange between EU MS | Exchange virus‐related information (e.g. genome sequences) to validate different laboratorial methods | |

| Training | Compulsory training for all professionals related to pig industry; information and training on the role of ‘human factor’ in the spread of ASF | |

| Diagnosis | Non‐invasive tests for wild boar | Non‐invasive sampling methodologies for wild boars |

| Improve sensitivity of diagnostics/improved rapid test/commercial confirmatory serological test | Diagnostics to distinguish between genome integrity and correlate to infectivity (especially in feed materials); develop new commercial confirmatory serological tests | |

| Cell lines for replacing primary cell cultures | Develop cell lines for replacing primary cell cultures | |

| Disinfection | Virus inactivation methods and products | Recommendations for inactivation treatments in potential contaminated feed, feed‐contact surfaces (e.g. vehicles or mills), raw materials of animal origin (e.g. blood products and hydrolysates) and bedding materials; need for studies on the efficiency of different disinfection procedures (i.e. type of product or disinfectant/acid combination), concentration, application method, equipment, time and temperature, pressure and pH); protocols for applications/applicability of disinfection; need for methods for large‐scale use of cleaning and disinfection measures if ASF is present in the wild boar population and environment; need for protocols to treat ASFV‐positive feed (e.g. by irradiation); best practices to assure recovery of an intensive pig holding after an outbreak |

| Carcass disposal methods | Safe disposal of wild boar cadavers: methods and procedures that are applicable in field conditions | |

| Member State management structure | Single point of contact for ASF management in a country | Need for the creation of a national management structure for ASF in domestic pigs and wild boar; intensification of the control efforts in key regions |

| Long‐term coordinated management strategy between involved sectors in each MS | Need for joint programmes of cooperation between agriculture and environmental sectors tailored for each MS; need for studies on the duration of the infection in the environment and on the length of the implementation of measures in the wider area; need for a strategy of coexistence with the disease | |

| International joint ASF control team | EU‐common management methods and legal authority that ensures the implementation of the control measures, including its application in neighbouring countries involved; creation of an international joint field team that would effectively act together and exchange information at expert level | |

| Ways to attract financial resources to control ASF | Training for hunters and the cancellation of hunting leases and hunters’ responsibility for damage to crops and forests when hunting prohibitions are implemented | |

| Source of introduction into a new country | Identify sources of introduction in a country (focal introduction) | Need for studies on unconsidered routes of introduction via food and feed (e.g. gain more knowledge on the frequency that ASFV‐infected meat and meat products from (a) illegal imports, (b) in part III areas, where ASF outbreaks occur in pig holdings and wild boar, and (c) ASF unaffected areas of the EU); better understanding of the ability of various feed ingredients to become contaminated during transit (ingredients coming from multiple locations); need for studies on source attribution and risk pathways in case of ASFV outbreaks (e.g. role of pork products and spread of long distances, unlawful slaughtering, illegal transport) |

| Human behaviour | Studies related to involvement of people (e.g. workers, hunters and tourists) in the transmission of ASFV over long distances | |

| Surveillance | Improve carcass detection methods for passive surveillance in wild boar | The need for new technologies (e.g. drones with thermographic cams, trained dogs, trained humans, etc.) to improve carcass detection; perform diagnostic checks on all the carcasses found in the woods/forest |

| Develop sampling protocols in feed | Develop validated sampling protocols in ingredients (feed ad ingredients); review specific operating procedures (SOPs) for the interpretation of the results and routine inspections of different feed matrices | |

| Improve sensitivity of border inspection controls to prevent introduction ASFV | Understand the quantity of infected meat that enters a country, either through legal or illegal means; intensify transit controls on passengers’ luggage coming from affected areas/countries | |

| Improve early detection | Strategies to early detection of outbreaks in wild boar and domestic pig populations; calculate reliable sample numbers and target wild boar population's sizes to detect wild boar found dead | |

| Pre‐export testing of piglets | Need for pre‐importation testing (testing at origin) | |

| Safe trade zoning | Determination of the range of occurrence of ASF within the safe zone and protection of non‐infected areas in the affected countries containing the disease. International negotiation aimed at obtaining regionalisation with non‐EU countries (China, Japan, etc.); consider learning to deal with ASF being present in wild boar populations in Europe | |

| Wild boar | Ecology | Need for studies on wild boar behaviour and their reaction towards cadavers (cannibalism), movements and migration patterns when intensified hunting; need for studies to understand better the role of feeding/non‐feeding/presence of unharvested crops on the movement of wild boar in different climatic conditions |

| Epidemiology | Need for studies on spread of ASFV within the wild boar population and the mechanisms that maintain the endemic incidence of ASF without the presence of specific vectors | |

| Population density | Need for studies to estimate the wild boar population density and population (hunting big data, drones, helicopters, satellite images as well as long‐term surveillance on the basis of faecal count/DNA/hair, great or local level) | |

| Control measures in wild boar population (management) | Need for understanding the impact of numerical reduction of the wild boar population together with limiting their natural movements; need for studies on most effective and practical techniques for reducing wild boar populations (e.g. hunting, trapping, night shots, fences, repellents, pesticides, heat‐seeking tools − cameras, rifle scopes, drones − especially after single (focal) introductions outside the main infected areas); understand better the role of physical barriers on ASFV transmission (if any); need for studies to evaluate fencing in different EU countries |

Figure 2.

Process followed for the assignment of categories and subcategories to the narrative answers received from the respondents

When some of the narrative answers from different respondents were copied (i.e. exactly the same wording was used in several surveys answered by different respondents), or repeated (i.e. the same answer was mentioned more than once by the same respondent in different ways), the assigned categories and subcategories were counted only once in order to avoid overrepresentation of certain respondents that repeated the same issues as research gaps. However, it was possible that the narrative answer of one respondent to a question led to the assignment of more than one different category and subcategory.

2.3. Stratification of the answers

The resulting answers were stratified according to the role of the stakeholder in the management of the disease and to the epidemiological situation of the affected area in their country.

2.3.1. Role of stakeholders

The questionnaire was sent to 191 different stakeholders (email addresses), and the participants were encouraged to distribute the questionnaire among members of their respective institution/organisation, to reach as many relevant respondents as possible.

In total, eight stakeholder groups were identified, and an online survey was sent to them using the ‘EU Survey’ tool. The identified stakeholder groups were: officials or veterinarians at a high managerial level (i.e. Chief Veterinary Officers or their deputies) or stakeholders involved in the support of the pig industry or wild boar management or hunting (i.e. officers from the Ministry of Agriculture representatives of the FVE, the farmers’ organisations, the pig feed industry, the official forest services and the recreational hunting organisations) (Figure 1), who can play an important role in the prevention and control of the spread of the disease.

In the analysis and presentation of answers in the Results section (Section 3.2), stakeholders were categorised as ‘Veterinary services’ or ‘Other’ for the sake of simplicity of visualisation.

2.3.2. Epidemiological status of the area

In addition to the type of stakeholder, the epidemiological status of the area was also taken into account and the possible influence this could exert on gap prioritisation was compared. It was hypothesised that priorities may change depending on the proximity of the epidemiological front, or the numbers of years the area/country had been affected by ASF.

Five different areas were considered based on a previous report from the EFSA (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2018): (1) ASF‐free area/country in the proximity of an affected area; (2) ASF‐free area/country far away from an affected area; (3) area/country with a focal ASF introduction; (4) ASF‐affected area/country for less than two summer seasons; and (5) ASF‐affected area/country for at least two summer seasons. It was possible for the respondent to select more than one option if more than one condition applied to their country.

If a country had several areas with a different epidemiological status, the worst case scenario was selected for the analysis. For example, when a country that is a free area in the proximity of an affected country as well as affected area for less than two summer seasons, the last scenario was chosen (= affected area for less than two seasons) to display the results.

2.4. Management of the priorities

Some of the respondents did not provide a reply in the fields provided in the questionnaire for the second and third priority but provided only their answer in the field provided for the first priority. However, these answers sometimes covered more than one category (see Section 2.2). Therefore, the ASF standing working group decided that ranking the results according to the three priorities was not possible and no weighting according to the priority was applied. However, for transparency reasons, an alphanumerical system was used to track the priority of the answers identified in the original answers of the respondents and this is provided in Appendix C.

3. Assessment

3.1. Description of the categories and subcategories

During the assessment, different categories and subcategories were assigned by the reviewers from the obtained answers. Some examples of the answers of these assigned categories and subcategories are provided in Table 1.

3.2. Results

There were 83 questionnaires completed out of 191 sent (43.5%). In total, 76 questionnaires were considered as valid for the analysis of the results (six provided copied answers and one participant considered that there was no research needed). From those valid questionnaires, 64% of the participants filled in the three priority fields, 30% completed two fields (priorities) and 6% completed only the first priority field. Around 30.5% of the valid responses were given by the group of Veterinary services and 60.5% by the other stakeholders.

From the narrative text provided in the questionnaire, 182 priority suggestions were assigned to the 10 categories and 273 to the 41 subcategories during categorisation (see Section 2.2). The number of assigned (sub)categories per narrative answer varied between 1 and 13.

Table 3.

Number of participants that answered per area and group of stakeholder

| Country/Area | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area | Area with an ASF focal introduction | ASF‐affected area for less than two summer seasons | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons | Total number of participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group of stakeholder | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | |

| Number of respondents | 11 | 12 | 9 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 76 |

ASFV: African swine fever virus; VS: Veterinary services.

3.2.1. Research priorities according to the different stakeholders

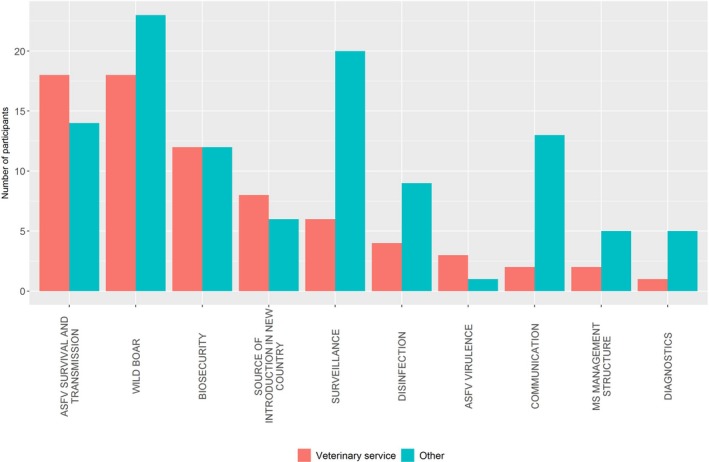

Figure 3 shows the number of suggestions for research priorities assigned to a particular category, grouped by the 2 stakeholder groups defined for this study, i.e. ‘Veterinary services’ and ‘Others’. The main gaps of concern suggested by the ‘Veterinary services’ were related to ‘ASFV survival and transmission’, ‘wild boar’ and ‘biosecurity’, while for the rest of the stakeholders the main gaps of concern were related to ‘wild boar’, followed by ‘surveillance’, ‘ASFV survival and transmission’ and ‘communication’. It is worth to highlight that both stakeholder groups suggested mainly topics related to wild boar and ASF survival and transmission. However, ‘surveillance’ and ‘communication’ stands out for the ‘Other’ group.

Figure 3.

Research priorities assigned to a category from the 182 suggested in the answers of the questionnaire, grouped by stakeholder groups

When considering the epidemiological status of the areas/countries (Table 2) of the group of stakeholders, the research priorities for the Veterinary services, stratified by area, were:

Table 2.

Number of suggestions for priorities assigned to the 10 categories grouped by ASF‐affected area/country and by group of stakeholder

| Country/Area | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area | Area with an ASF focal introduction | ASF‐affected area for less than two summer seasons | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons | All areas | Total number of assigned categories | ||||||

| VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | VS | Other | ||

| Wild boar | 6 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 41 |

| ASF survival and transmission | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 18 | 14 | 32 |

| Biosecurity | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Surveillance | 2 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 20 | 26 |

| Communication | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Source of introduction into a new area | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Disinfection | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| MS management structure | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Diagnosis | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| ASFV virulence | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 31 | 29 | 16 | 47 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 17 | 12 | 74 | 108 | 182 |

ASFV: African swine fever virus; VS: Veterinary services.

|

Equally ‘ASFV survival and transmission’, ‘biosecurity’ and ‘wild boar’ |

|

‘Wild boar’ |

|

‘ASFV survival and transmission’ |

|

‘Wild boar’ |

|

‘ASFV survival and transmission’ and ‘wild boar’ |

For the ‘Others’ stakeholder group the priorities were:

|

‘Surveillance’ followed by ‘disinfection’ |

|

‘Wild boar’ and ‘surveillance’ by far difference. There were two respondents that considered that no research was needed in this area |

|

Low representation and no category stands out for this area |

|

‘Wild boar’ |

|

Equally ‘biosecurity’, ‘communication’, ‘wild boar’ and ‘MS management structure’ |

For both groups of stakeholders, the participation rate was higher in the free areas, where the respondents were more concerned about research priorities in the ‘surveillance’ and ‘wild boar management’ categories (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of the main categories per group of stakeholder per area

| Veterinary services | Other | |

|---|---|---|

| ASF‐free area far away from the affected area/country |

1. ASFV survival and transmission 2. Biosecurity 3. Wild boar |

1. Surveillance 2. Disinfection |

| ASF‐free area/country in the proximity of an affected area | 1. Wild boar |

1. Wild boar 2. Surveillance |

| Area with an ASF focal introduction | 1. ASFV survival and transmission | 1. No outstanding category |

| ASF‐affected area/country for less than two summer seasons | 1. Wild boar | 1. Wild boar |

| ASF‐affected area/country for at least two summer seasons |

1. ASFV survival and transmission 2. Wild boar |

1. Biosecurity 2. Communication 3. Wild boar 4. MS management structure |

3.2.2. Research priorities per specific subcategory

The answers were counted separately for the subcategories, given that one category could include more than one subcategory. Therefore, the total number of assigned research priorities at the subcategory level (n = 273) was higher than the total number at the category level (182). As described in Section 2.2, when the answers from different respondents were copied (i.e. exactly the same wording was used in a few surveys answered by different respondents), or repeated (i.e. the same subcategory was mentioned more than once by the same respondent in different ways), the assigned categories and subcategories were counted only once.

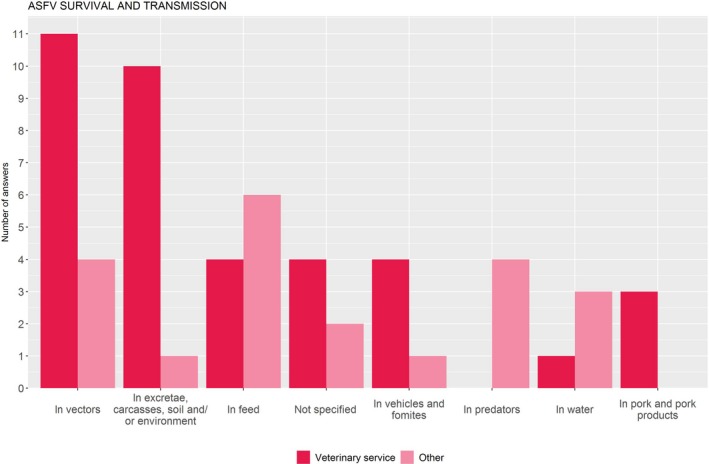

3.2.2.1. ASFV survival and transmission

The main research priority of the stakeholder group ‘Veterinary services’ was research on ‘ASFV survival and transmission’, in particular research on the possible transmission of ASFV by arthropod vectors, followed by research on the survival time of ASFV in excreta, carcasses, soil and environment, feed and other matrices such as pork and pork products. For the other stakeholders, and especially for the feed industry, research on the potential survival of ASFV in feed was a major priority, followed by research on ASFV transmission by arthropod vectors and indirect transmission of ASFV by predators (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘ASFV survival and transmission’ by each group of stakeholders

The main rationale provided for suggesting the above‐mentioned research priorities were the continuous spread of the disease in the domestic pig sector, without evidence of direct transmission (e.g. no recent purchase of domestic animals, no wild boar contact or biological vectors detected in the area), and the need to identify the exact sources of indirect transmission, such as human‐mediated spread through pork or pork products or fomites, so that it can be better prevented. Therefore, also the possible involvement of mechanical vectors in ASFV transmission was identified as a gap of knowledge by the Veterinary services.

3.2.2.2. ASFV virulence

This category is mainly reported by the Veterinary services and focuses on studies to understand the virulence of the circulating ASFV, the role of less virulent strains in the spread and maintenance of the disease as well as the use of certain less virulent ASFV strains in potential vaccines against ASFV. One respondent mentioned the need to investigate the combination of attenuated ASFV strains/tolerant pig breeds with higher rate of survival as an animal model for the development of an ASF vaccine.

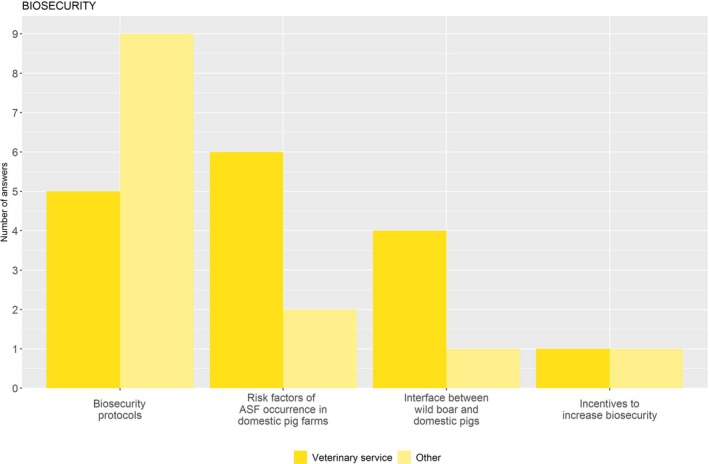

3.2.2.3. Biosecurity

According to the respondents, there was a clear need to set out and draft protocols to increase the biosecurity levels of different pig husbandry systems. The rationale provided was the implementation of improved biosecurity measures in different husbandry types is not necessarily hampered by the lack of subsidies or incentives, but by the lack of knowledge of the epidemiology of the disease, which would allow the identification of possible risk factors involved in an outbreak; and by the a lack of knowledge on the interface between both pig and wild boar populations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘biosecurity’ by each group of stakeholders

The main topic of concern suggested by the Veterinary services was related to risk factors of ASF occurrence and spread in domestic pig farms, while the other stakeholders suggested the need for a better understanding of the biosecurity levels and the availability of protocols to prevent the introduction of ASFV in pigs’ holdings and in the pork production chain.

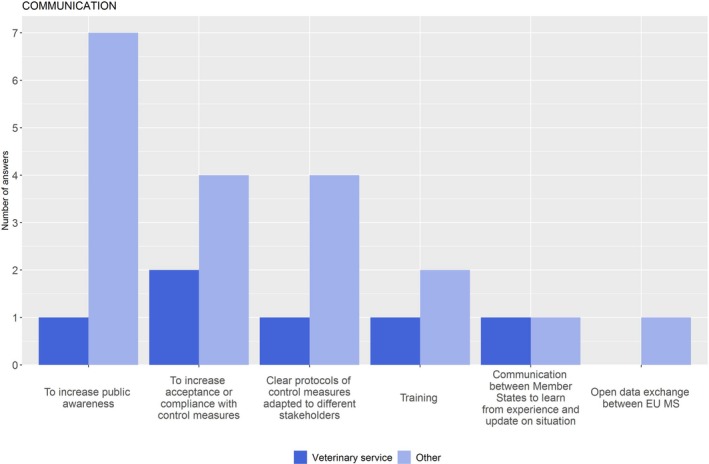

3.2.2.4. Communication

The main topic of concern for the Veterinary services in this category was to increase the compliance with control measures of every group involved with the prevention and control of ASF in the field, even though this category was not identified as a main priority of the Veterinary services.

For the rest of the participants, communication and increased public awareness was a major area of concern, to ensure the compliance with the control measures such as wild boar culling and wild boar management, cleaning and disinfection of potentially infected transported pork products, implementation of the minimum biosecurity measures or the reinforcement of the existing swill feeding ban.

This stakeholder group also indicated the need to develop clear protocols adapted to each of the stakeholder groups involved (e.g. drivers, farmers, veterinarians, hunters, trade managers or general society) in the management of the disease, with clear instructions (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘communication’ by each group of stakeholders

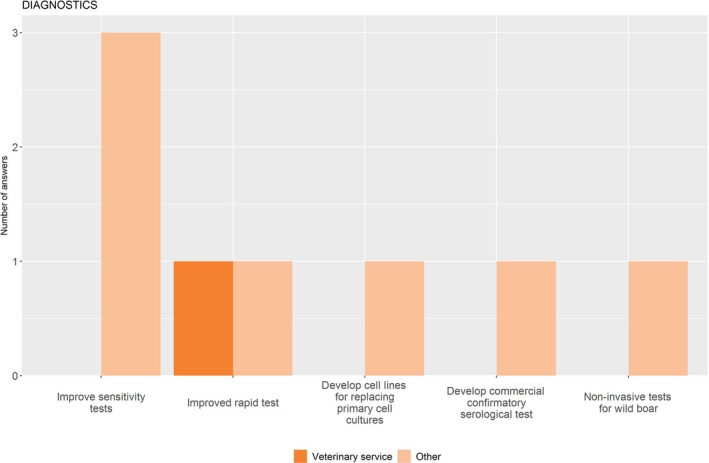

3.2.2.5. Diagnostics

Within this research priority category, the main identified need was to improve the diagnostic sensitivity of tests and the ability to distinguish between polymerase chain reaction (PCR)‐positive samples and samples that contained infectious virus, in particular for feed and feed components. In addition, a knowledge gap was identified in the interpretation of PCR‐positive carcasses in very decomposed carcasses, to improve the timing of ASFV infection and the establishment of a freedom‐from‐disease status of a wild boar population.

Moreover, the need for further research on the development of rapid and sensitive diagnostic assays (also applicable for wild boar testing and feed testing as well as testing of food or other products) was suggested, as well as the need for research into the other subcategories shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘diagnostics’ by each group of stakeholders

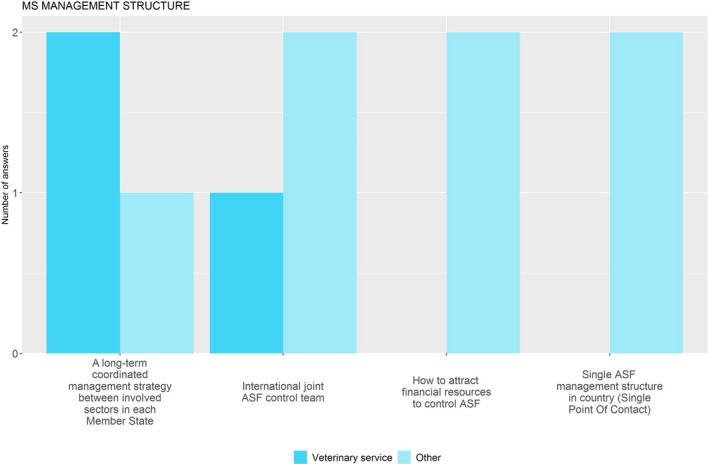

3.2.2.6. MS management structure

The Veterinary services expressed the need for a long‐term strategy for prevention and control of ASF and for a joint (international) control programmes for ASF management in cooperation with the different sectors involved and tailored to the situation of each country (despite an already existing strategy and legal framework in terms of international cooperation). The other stakeholders also expressed the need to manage the spread of the disease in a more harmonised way (via a joint/international effort of the teams in the field) with enough financial resources to implement management measures in a coordinated, fast and efficient way (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘Member State management structure’ by each group of stakeholders

3.2.2.7. Disinfection and inactivation methods

There was a clear demand for research on methods and products for virus inactivation in different contaminated materials and products derived from potentially infected animals. Several stakeholders expressed the need to list the most effective and practical ways to inactivate or disinfect ASFV from their products. In addition to the need to disinfect products and/or matrices, stakeholders also identified the need to improve knowledge on the effect of using large‐scale disinfection in the environment and to identify the best protocols to clean and disinfect affected holdings, to reduce the allowed time before repopulation of affected pig holdings. The Veterinary services also expressed the need for an optimum method for safe disposal of carcasses of wild boar and domestic pigs.

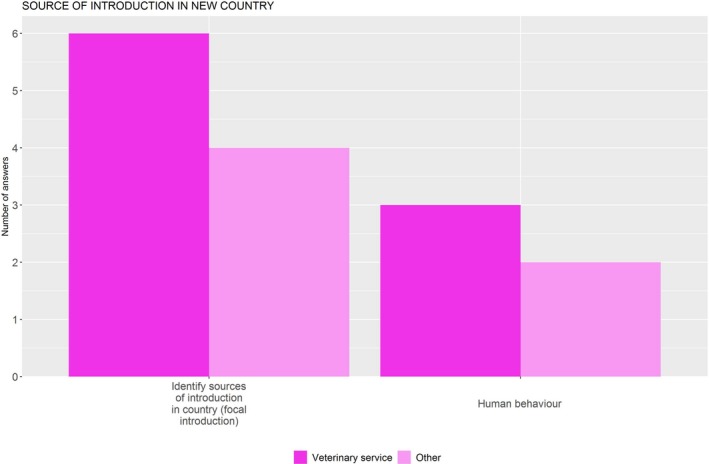

3.2.2.8. Source of introduction into a newly affected country or area

The lack of identification of the source of introduction into a new country or area was considered to be a significant gap of knowledge in many previous risk assessments. Therefore, many stakeholders expressed the need for studies that could contribute to fill these gaps and focus also on the possibility of unconsidered routes of introduction that could be human‐mediated, e.g. via food (pork and pork products) and feed from affected farms and especially via illegal transport of animals for slaughter into ASF‐free regions from areas where ASF outbreaks had occurred. In addition, it was suggested that, as long‐distance introductions had occurred, there was a need to better understand human behaviour, and the socioeconomic aspects of human‐mediated spread also needed to be investigated (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘source of introduction in a new country’ by each group of stakeholders

3.2.2.9. Surveillance

The need for methods with improved passive surveillance strategies for early detection of positive domestic pigs or wild boar was highlighted by the Veterinary services. In addition, the need to optimise the detection of wild boar carcasses and to develop new technologies to improve border controls of passengers, trucks and commercialised products to intercept the possible introduction risky materials (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘surveillance’ by each group of stakeholders

3.2.2.10. Wild boar

To prevent and control the spread of ASFV in wild boar populations, a reduction in the wild boar population density in the intensive hunting area around the affected area, possibly together with a limitation of their natural movements in the infected core area had been suggested (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2018). However, it was suggested by the respondents that there is still a need to find the best and most effective (and practical) way to achieve this goal.

In addition, the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms for spread and perpetuation of ASF in wild boar populations, as well as the potential factors contributing to endemicity in an area were highlighted.

It was also suggested that there is a lack of knowledge on the behaviour of wild boar and the effect on the potential spread of ASF, especially behavioural patterns not reported before (e.g. cannibalism) (FAO, 2019); the need for research on effective methods to estimate the wild boar population density in the different countries was also identified (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Number of unique answers given for each subcategory within the category ‘wild boar’ by each group of stakeholders

4. Discussion

The response rate of this questionnaire was 43.5%; this can be considered as an average and good response rate for an external survey. However, the response rate could have been improved by providing the respondents more time to complete the questionnaire and extend the deadline for receiving the answers. In total, eight different stakeholder groups were identified and stratified into two categories for analysis: the Veterinary services (containing two groups of stakeholders) and ‘other stakeholders’ (containing six group of stakeholders). A higher response rate was received from the other stakeholder (60.5% than the Veterinary services vs 39.5% for the other stakeholders). Thanks to the questionnaire being extended also to stakeholders with non‐managerial positions, but who could play an important role in the prevention and the spread of the disease, these differences can be noted and taken into account when managerial decisions are made.

The epidemiological status of the area did not appear to play a significant role in the research gaps provided. However, the response rate was higher for the respondents from ASF‐free areas, reflecting the higher proportion of free areas compared to affected ones.

The open‐ended questionnaire was intentionally meant to obtain clear information on research gaps as perceived by the stakeholders via a narrative answer. The disadvantage of this approach might be a subjective interpretation of reviewers during the categorisation (Section 2.2), and therefore, it could be considered in the future to use a close‐ended questionnaire using the defined categories and take advantage of the priorities given by the respondents (first, second and third), which was not possible during this study. Nonetheless, the assigned categories were reviewed and agreed by three independent reviewers and the number of assigned (sub)categories proved that there was not ‘overinterpretation’ of the original answers provided. Some of the identified research gaps may require more than 12 months (short term) to be implemented. Furthermore, the list of different suggestions received through the open questions was extensive and would have most likely not been captured in a set of given answers, provided by the assessors.

5. Conclusions/recommendations

Given the subjectivity of the task of assigning open answers to different research priority categories, the most significant outcomes of this report are the rationales behind the different categories and the suggested subcategories of research priorities, rather than the exact numbers of suggestions for each of the different categories made by the different stakeholders involved in ASF prevention and control.

Overall, the four categories identified as major research gaps, considering the answers of all the participants (regardless of the stakeholder group to which they belonged) were ‘wild boar’, ‘ASFV survival and transmission’, ‘biosecurity’ and ‘surveillance’.

-

In relation to wild boar, the crucial identified gaps of knowledge were the need for:

-

–

harmonised methods to estimate wild boar population density in an area;

-

–

studies on the possible correlation of the population density of wild boar and ASF occurrence in wild boar;

-

–

identify effective methods to reduce the absolute number of wild boar/population size in an area;

-

–

studies on the mechanism of spread and potential ASFV persistence in the wild boar population;

-

–

studies on the possible role of direct host‐to‐host transmission, taking into account the typical wild boar's behaviour.

-

–

-

For ASFV survival and transmission, more knowledge was requested to better understand and manage:

-

–

the role of arthropod vectors in ASF transmission (biological and mechanical);

-

–

ASFV survival and transmission from a contaminated environment;

-

–

the potential transmission with origin in contaminated feed and feed materials, i.e. to investigate the possible risk of contamination during production of feed materials or during processing of compound feed, the possible survival of ASFV during transportation and storage of compound feed and the possible contamination of feed after packaging;

-

–

the potential survival and transmission of ASFV from different bedding and forage materials, pork products and fomites.

-

–

-

For biosecurity, some identified critical gaps of knowledge were the identification of:

-

–

the most efficient measures for preventing the introduction of ASF in a country or region and in a farm;

-

–

the minimum biosecurity measures for different husbandry systems, e.g. by developing effective protocols and by increased awareness of biosecurity on different types of farms;

-

–

measures to reduce the transmission between wild boar and domestic pigs;

-

–

possible risk factors for outbreaks of ASF in domestic pig farms (e.g. socioeconomic factors, factors related to farming practices and traditions).

-

–

-

For surveillance, it was suggested that of primordial importance was the need:

-

–

to develop methods to improve border inspection controls over moving people, trucks and/or goods to reduce the risk for introduction of ASF into new countries/areas;

-

–

to improve methods for passive surveillance to improve early detection, more precisely in the areas of:

-

o

carcass detection;

-

o

sampling protocols (e.g. to test feed after the final stage of processing);

-

o

sensitive and rapid on‐site diagnostic tests that can be performed in the field (non‐invasive tests in case of wild boar).

-

o

-

–

In addition, especially the Veterinary services identified the need to identify the source of ASFV introduction into a previously unaffected country that should comprise an analysis of the possible pathways of introduction with a special focus on food, feed, transport of live wild boar1 and human‐mediated spread (especially transmission over long distances).

Finally, research on improved communication methods was a topic mentioned by almost every group of stakeholders. It included the need to raise awareness among all players involved in the epidemiology of the disease (including drivers, hunters and tourists) and to increase compliance with the control measures.

Among the less repeated categories, the need for improved disinfection methods and carcass disposal protocols were identified, as well as the need for the development of an international harmonised ASF management structure − despite an already existing strategy and legal framework in terms of international cooperation − and the need for more research on the role of low virulent virus strains in the maintenance of the disease.

Based on the results above the following studies could be recommended:

-

in relation ASFV survival and transmission:

-

–

studies on the potential ASFV survival in feed and feed components before, during and after processing of feed from different sources;

-

–

studies on the role of different arthropod vectors in ASFV transmission.

-

–

-

in relation to wild boar density and wild boar population management:

-

–

studies to evaluate the impact of reducing the wild boar population densities in relation to transmission of ASFV; and studies on the natural behaviour of wild boar to improve wild boar population management.

-

–

-

in relation to biosecurity:

-

–

benchmarking studies or studies on the use of monitoring tools to improve biosecurity in domestic pig farming;

-

–

risk factor analysis for the entry of ASFV at farm level;

-

–

improving the husbandry practices and livestock production (professionalising pig farming) with appropriate biosecurity measures.

-

–

-

in relation to surveillance:

-

–

validation studies on rapid field diagnostics for ASFV;

-

–

methods or tools to increase sensitivity for carcass detection (passive surveillance);

-

–

sampling protocols for feed testing for ASFV.

-

–

-

other recommendations:

-

–

more border controls to control more the potential import of infected material/commodities;

-

–

promote more efficient communication via the distribution of leaflets;

-

–

distribution of protocols for cleaning and disinfection for ASFV in environment and equipment; training on decontamination programmes and procedures (FAO, 2001).

-

–

Glossary

- Answer

input gave by the respondent in the questionnaire.

- Copied answer

an answer which is copied word by word by more than one respondent.

- Group of stakeholders

groups created as'Veterinary services’ and'Others’ for ease in displaying the results.

- Repeated answer

same category mentioned more than once for a same participant.

- Respondent

individual that provided an answer to the questionnaire. Used as synonym of stakeholder in the report.

- Stakeholder

different pig related sectors whom the questionnaire was sent, which includes Chief Veterinary Officer, Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services, FVE, Ministry of Agriculture from all EU MS, farmers’ organisations, forest official services, pig feed industry and recreational hunting organisations.

- (Sub)category

interpretation made by the reviewers to classify/categorise the answers of the respondents.

- Valid answer

all suggestions received excluding copied and repeated answers and long‐term suggestions (e.g. vaccine related).

Abbreviations

- AHAW Panel

EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare

- ASF

African swine fever

- ASFV

African swine fever virus

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- FAO

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

- FVE

Federation of Veterinarians of Europe

- GARA

Global African Swine Fever Research Alliance

- IPT

immunoprecipitation

- IRC

STAR‐IDAZ International Research Consortium on Animal Health

- MGF

multigene family

- MS

Member State

- NGO

Non‐governmental organisation

- OIE

World Organisation for Animal Health

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SOP

specific operating procedure

- WB

wild boar

Appendix A – Sample of the questionnaire sent out to stakeholders related to ASF

1.

Appendix B – Major gaps amongst all the stakeholders

1.

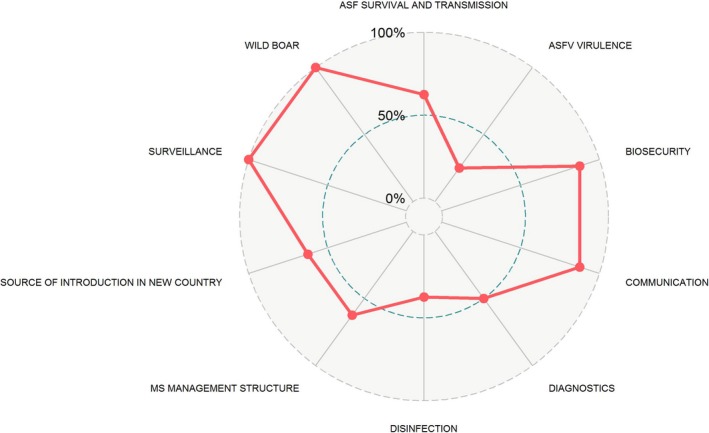

The most reported categories in the prevention and control of ASF are shown in Figure B.1, as a percentage of the different stakeholder groups that suggested a particular category. When a category scores 100%, it means that at least one participant of each of the eight stakeholder groups suggested that specific category.

Figure B.1.

Spider graph showing the percentages of different stakeholder groups suggesting a particular category of research priority. It shows the ‘popularity’ of the categories amongst the stakeholder groups as a unit

‘Wild boar’ and ‘surveillance of ASF’ were the two most suggested research categories − which were mentioned by at least one respondent of every stakeholder group − followed by ‘biosecurity’ and ‘communication’. ‘survival and transmission of ASFV through different products’, the ‘management structure in the different MSs’ and ‘source of introductions into a new country’ were also considered as significant research gaps. The topics that were considered less important, in decreasing order were ‘diagnostics’, ‘disinfection’ and ‘ASFV virulence’, which were mentioned by 50% or less of the different stakeholder groups.

Appendix C – Original answers obtained from the questionnaire

1.

| Indicate which position/role you have or which stakeholder group you represent: | Epidemiological status |

First priority (a) Second priority (b) Third priority (c) |

CATEGORY, subcategory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Knowledge on wild boar biology. b. Reliable methods for estimating wild boar population densities. c. Epidemiology of ASF in wild boar |

1. WILD BOAR, wild boar ecology 1. WILD BOAR, wild boar density 1. WILD BOAR, ASF epidemiology in wild boar |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons |

a. ASF virus spread within the wild boar population: wild boar movement patterns, ways of virus introduction and spread, role of seropositive animals, role of dead wild boar carcasses. b. ASF introduction in to pig holdings – the way the virus entered the farm, role of different mechanical transmitters – human, vehicles, feed, insects. c. ASF epidemiology – survival of the ASF virus in the soil, in the carcasses, in the meat – new data are requested |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF epidemiology in wild boar 2. WILD BOAR, wild boar ecology 1. BIOSECURITY, Risk factors of ASF occurrence in domestic pig farms 2. ASF survival and transmission in vehicles 3. ASF survival and transmission in feed 4. ASF survival and transmission in vectors 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, ASF survival in soil and or environment 2. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in carcasses 3. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in pork and pork products |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Extended transit controls of people from affected areas/countries, especially transports with living pigs. Food preserves or lunch bags originating from these countries should be safely removed. b. Detection of infected pigs as soon as possible. c. Protection of non‐infected areas within the affected countries |

1. SURVEILLANCE, surveillance to improve sensitivity of border inspection controls to prevent introduction ASFV 1. SURVEILLANCE, Surveillance to improve early detection 1. SURVEILLANCE, safe trade zoning |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. ASF in [country] is present exclusively in the region of [X region], which is an island, far away from European MS affected. In this island, ASF has been present for many years and its eradication has always been made difficult mainly due to social problems, linked to the extremely rooted and traditional way of pig farming on the island [1]. To date, extraordinary measures have been implemented that have significantly improved the situation on the island. As regards the continental part of Italy, where the disease is not present, taking into account the current European epidemiological situation and the role of wild boar population (which has developed in uncontrolled manner) in the spread of the disease, activities are being prepared to increase the level of passive surveillance in wild boars, with the diagnostic check of all the carcasses found in the woods [2], in case of road accident or other eventualities, and through the sampling check of the boar killed by the hunters. In addition, measures aimed at the numerical reduction of wild boar population are being evaluated, based on an accurate numerical estimate, assessment of the areas at greatest risk of introduction of the disease [3]. Not feeding wild boar is already ongoing. Given the role of the ‘human factor’ in the transmission of the disease, including long‐distance ‘jumps’, Italy is preparing training and information courses [4] aimed at all the possible categories: veterinarians, hunters, farmers, check point staff, travellers, transporters, trekkers, participants in the food sector, users. The level of biosecurity will be increased in pig farms to prevent the spread of the virus from wild boar to domestic pigs [5] and preparation courses will be carried out for the early recognition of the disease on the farm and to raise the level of prompt response [6] if there is of suspicion of the disease (containment in small areas, coordinate actions, etc.). b. Consolidate the level of preparation and knowledge of the disease: ban of feeding wild boar (already underway) [2], recognition of symptoms, risk related to the transport of pigmeat. Develop and updating legislation to take into account the development of the disease in each single Member State. Meetings/exchange of information and data between Member States to review ongoing ASF situation. Also for non‐EU countries? c. A long‐term management strategy and joint programmes of cooperation between the agriculture and environmental sector tailored to the situation of each single Member State |

1. BIOSECURITY, risk factors of ASF occurrence in domestic pig farms 2. SURVEILLANCE, improve carcass detection methods in wild boar 3. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 4. COMMUNICATION, training 5. BIOSECURITY, interface between wild boar and domestic pigs 6. SURVEILLANCE, improve early detection 1. COMMUNICATION, to increase public awareness 2. COMMUNICATION, to increase acceptance or compliance with control measures 3. COMMUNICATION, Communication between Member States to learn from experience and update on situation 4. MS MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE, International joint ASF control team 1. MS MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE, A long‐term coordinated management strategy between involved sectors in each Member State |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐affected area for less than two summer seasons |

a. The EFFECTS OF WILD BOAR FEEDING (or unharvested crops) on the movement/keeping in place of wild boar versus its effect on the population size UNDER DIFFERENT CLIMATIC CONDITIONS (in our country winters are often mild and there is plenty of feed available for wild boar to survive winter; however, if feeding is banned – as prescribed by current EU guidelines –/crops harvested/, the wild boar will leave that area which could be a problem in an infected area). b. We would be happy to see studies on the SURVIVAL OF THE VIRUS IN DIFFERENT FEED/BEDDING MATERIALS which have a possible role in transmitting the disease. For example, in the current guideline there is a 30 days’ waiting period for fresh grass or grains, whereas 90 days for straw, but what is the evidence for this? What is the recommended treatment of these materials, safe to inactivate the virus and safe to be fed to food producing animals? |

1. WILD BOAR, ecology 2. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in feed 2. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in different materials 3. DISINFECTION, virus inactivation methods and products |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | Area with an ASF focal introduction |

a. Way of spreading ASF in a natural way in the wild boar population in conditions of very low density of wild boar and the possibility of preventing this spread; which mechanisms maintain the endemic incidence of ASF under these conditions and without the presence of specific vectors. b. Searching and safe disposal of wild boar cadavers: possibilities, methods, safely procedures; research into the behaviour of wild boar towards cadavers. c. Survival of ASF virus in the wild under natural conditions, the role of passive ASF virus vectors |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF epidemiology in wild boar 2. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 1. SURVEILLANCE, improve carcass detection methods for passive surveillance in wild boar 2. DISINFECTION, carcass disposal methods 3. WILD BOAR, ecology 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, ASF survival in soil and or environment 2. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons |

a. Importance of ELISA positive wild boar. b. Threshold and fade out of ASF. c. Insects role in a spread of ASF |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF epidemiology in wild boar 1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, identify sources of introduction in country (focal introduction) 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐affected area for less than two summer seasons |

a. Availability of an effective vaccine for wild boar for oral application. b. Effective and practical methods to reduce the wild boar population. c. Practical methods for estimating the wild boar population density |

1. Exclude 1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 1. WILD BOAR, density |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Prevent the illegal transport of infected meat. b. Early warning systems |

1. SURVEILLANCE, surveillance to improve sensitivity of border inspection controls to prevent introduction ASFV 1. SURVEILLANCE, surveillance to improve early detection |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. An analysis of the likely cause of disease being detected in areas far from any known outbreaks of ASF. b. An analysis of the effectiveness of biosecurity in preventing the spread of disease from wild to domestic species. c. Validated disinfection and decontamination best practices to assure recovery of intensive pig housing post‐outbreak |

1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, identify sources of introduction in country (focal introduction) 1. BIOSECURITY, interface between wild boar and domestic pigs 1. DISINFECTION, virus inactivation methods and products |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Immunisation strategies in wild boar populations. b. Further investigation in the potential pathways in the entrance of the virus in a territory |

1. Exclude 1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, identify sources of introduction in country (focal introduction) |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. Development and validation of rapid and field diagnostic tests for ASF. b. Role of wild boar in ASF transmission and maintenance |

1. DIAGNOSTICS, improved rapid test 1. WILD BOAR, epidemiology in wild boar |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. Increased biosecurity in holdings: research into the risk of the disease spreading to holdings of pigs via vectors as insects, hay, straw, silage. b. Evaluation of wild boar population/density in areas, prevalence in the country. Research into how to best estimate/decide the size of a wild boar population and where they are. c. Reduction of wild boar density: research into best practices of population reduction by means of trapping, hunting, fencing with euthanasia, etc. |

1. BIOSECURITY, biosecurity protocols 2. BIOSECURITY, risk factors of ASF occurrence in domestic pig farms 3. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in fomites 4. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors 1. WILD BOAR, epidemiology in wild boar 2. WILD BOAR, density 1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Animal model to address long‐term questions: if all of the infected pigs die within days there is no way to study vaccines etc. Need to investigate further strains of ASFV in other animal (breeds) to determine the most resistant combination. b. Stability of ASFV in different pork meat products: some of the acclaimed stability does not suit an enveloped virus. c. Disinfection procedures that work under field conditions (wild boar carcasses in particular) |

1. ASFV VIRULENCE FACTOR, tolerant pig breeds 2. ASFV VIRULENCE FACTOR, less virulent strains 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in pork and pork products 1. DISINFECTION, carcass disposal methods |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | Area with an ASF focal introduction |

a. The virulence of circulating strains. A weakened strain can spread unnoticed and become endemic in the wild population. b. the possible role of insects (flies, mosquitoes, midges, ticks) in the transfer of ASF under field conditions. c. Is there a risk related to the use of feed (e.g. corn) produced in infected areas, given the resistance of the virus in the environment |

1. ASFV VIRULENCE FACTOR, less virulent strains 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in feed |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. Survival of the virus in the carcass surroundings: – Do different kinds of soil influence the survival of the virus? b. Are there any practical/feasible ways to permanently lower the wild boar prevalence? |

1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in soil and/or environment 1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. How do pig holdings in affected areas become infected despite state‐of‐the art biosecurity plans? Is there an unrecognised transmission route for ASF virus [1] that is not mitigated by current biosecurity plans? The seasonal pattern of outbreaks (June–September) in northern and eastern Europe suggests that insect vectors [2] (other than soft ticks) are much more involved than previously recognised. How can outbreaks in pig holding be prevented [3] much more efficiently than now? b. How does ASF virus escape the established control zones and colonise unaffected areas beyond what can be explained by natural transmission in wild boar populations? This has happened on numerous occasions in the last 4 years. c. What is the frequency of ASF virus infected meat and meat products from: (1) illegal imports, (2) in part III areas, where ASF outbreaks occur in pig holdings and wild boar, (3) ASF unaffected areas of the EU |

1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in different materials 2. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors 3. BIOSECURITY, biosecurity protocols 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in soil and or environment 1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, identify sources of introduction in country (focal introduction) |

| Veterinary Officer/Veterinary services | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons |

a. – The importance of insects in virus transmission. Ornithodoros or other soft ticks areal in Europe. – The role of other vectors (rats, birds, etc.). b. The transmission from wild boar to domestic pigs’ cycle. Resistance and survival time of virus in different objects, environment. c. How much does minimum biosecurity measures guarantees the safety of a farm |

1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION 1. BIOSECURITY, interface between wild boar and domestic pigs 2. ASF survival and transmission in different materials 3. ASF survival and transmission in soil and or environment 1. BIOSECURITY, protocols |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐affected area for at least two summer seasons |

a. Role of wild boar behaviour in ASF virus spread and persistence in the wild boar meta‐population. b. ASF virus infectiveness in the environment (forest), how long a time a virus in the active form persists in the environment after ASF epidemic stage |

1. WILD BOAR, ecology 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, ASF survival in soil and or environment |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Research to develop a vaccine in wild boar an pig population. b. Research to understand better the epidemiology of the disease. c. Study to understand better the different risk factors of introduction of the virus in the pig population |

1. Exclude 1. WILD BOAR, ASF epidemiology in wild boar 1. BIOSECURITY, risk factors of ASF occurrence in domestic pig farms |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Any, the most important thing is vaccination possibility and control of spreading of disease in WB population. b. Survival of virus in the population of ticks living in the middle European region and their direct influence of spread of disease. c. Survival of virus in cadavers (dead wild boar) taking into account climate conditions in the middle European region |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar populations (management) 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in vectors 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in carcasses |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. How to control the wild boar population ([country of the respondent] has a small wild boar population 1,000–1,500 animals. Our neighbour [neighbour country] has a population of 400,000 animals. We have a long boarder towards [neighbour country]). b. How to control the risk of infection through labour coming from countries with ASF, working in [country of the respondent] pig farms. c. The risk connected with hunters hunting wild boar abroad [from the country of the respondent] |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, human behaviour 1. SOURCE OF INTRODUCTION IN NEW COUNTRY, human behaviour |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. Information on the current impact of physical barriers on ASF transmission in wild boar population (between metapopulations) and also to domestic pigs – the current impact on the spread rate – whether it is to prevent (stop) the spread of the disease or only by slowing the migrations of wild boar to reduce the spread rate? b. More information is needed on the impact of the duration of the infection: the impact of the leftovers of infected cadavers, faeces in the forest,…on the length of the implementation of measures [4], in the wider area, not only in the infected area itself. What this means for other activities in the forest: transport, cleaning, disinfecting vehicles… |

1. WILD BOAR, ASF control measures in wild boar (management) 1. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, ASF survival in soil and or environment 2. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in carcasses 3. ASF SURVIVAL AND TRANSMISSION, in faeces, urine 4. MS MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE, a long‐term coordinated management strategy between involved sectors in each Member State |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area; ASF‐free area in the proximity of an affected area |

a. Affected countries indicate that eradication in wild boar seems almost impossible, strategies to clearly differentiate between outbreaks in wild boar and domestic pig populations need to be prepared. Europe will have to learn to deal with ASF being present in wild boar populations, as it is common practice with other diseases e.g. Aujeszky's disease. b. Nevertheless, all measures to gain the upstanding aim, need to consider ‘alternative’ and small‐scale production systems. Sustainability and animal welfare are priority demands from the public. Unproportional biosecurity requirements and profound changes in existing production systems might make alternative pig production impossible. Additional risk assessment considering different levels of biosecurity might be helpful |

1. SURVEILLANCE, to improve early detection 2. SURVEILLANCE, safe trade zoning 1. BIOSECURITY, protocols |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |

a. To control risk material introductions through transit (borders, live swine, products obtained from swine). To control personal luggage and consignments coming from infected zones. b. To intensify passive surveillance (collecting samples from dead boar found in the nature). c. To improve biosecurity in pig farms |

1. SURVEILLANCE, surveillance to improve sensitivity of border inspection controls to prevent introduction ASFV 1. SURVEILLANCE, improve carcass detection methods for passive surveillance in wild boar 1. BIOSECURITY, protocols |

| Chief Veterinary Officer | ASF‐free area far away from the affected area |