Abstract

Rationale

Even in antiretroviral therapy (ART) treated patients, HIV continues to play a pathogenic role in cardiovascular diseases. A possible cofactor may be persistence of the early HIV response gene Nef, which we have demonstrated recently to persist in the lungs of HIV+ patients on ART. Previously, we have reported that HIV strains with Nef, but not Nef-deleted HIV strains, cause endothelial proinflammatory activation and apoptosis.

Objective

To characterize mechanisms through which HIV-Nef leads to the development of cardiovascular diseases using ex vivo tissue culture approaches as well as interventional experiments in transgenic murine models.

Methods and Results

EV (extracellular vesicles) derived from both peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and plasma from HIV+ patient blood samples induced human coronary artery endothelial cells dysfunction. Plasma derived EV from ART+ patients that were HIV-Nef+ induced significantly greater endothelial apoptosis compared to HIV-Nef- plasma EV. Both HIV-Nef expressing T cells and HIV-Nef-induced EV increased transfer of cytosol and Nef protein to endothelial monolayers in a Rac1-dependent manner, consequently leading to endothelial adhesion protein upregulation and apoptosis. HIV-Nef induced Rac1 activation also led to dsDNA breaks in endothelial colony forming cells (ECFC), thereby resulting in ECFC premature senescence and eNOS downregulation. These Rac1 dependent activities were characterized by NOX2-mediated ROS production. Statin treatment equally inhibited Rac1 inhibition in preventing or reversing all HIV-Nef-induction abnormalities assessed. This was likely due to the ability of statins to block Rac1 prenylation as geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitors were effective in inhibiting HIV-Nef-induced ROS formation. Finally, transgenic expression of HIV-Nef in endothelial cells in a murine model impaired endothelium-mediated aortic ring dilation, which was then reversed by 3-week treatment with 5mg/kg atorvastatin.

Conclusion

These studies establish a mechanism by which HIV-Nef persistence despite ART could contribute to ongoing HIV related vascular dysfunction which may then be ameliorated by statin treatment.

Keywords: HIV-Nef; endothelial dysfunction, apoptosis; extracellular vesicles; endothelial progenitor cells; endothelial colony forming cells; Inflammation; Oxidant Stress; Stem Cells; Vascular Disease

INTRODUCTION

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-positive patients remain at higher risk for developing cardiovascular diseases (CVD) including acute myocardial infarction1, peripheral arterial disease2 and hypertension despite achieving circulating viral suppression with antiretroviral therapy (ART)3–5. Importantly, CVD remains a major cause of death in HIV patients with undetectable viral loads and well-preserved CD4 counts6. These data suggest that HIV infection increases the risk of vascular pathologies.

A healthy endothelium is important for the maintenance of vascular tone and prevention of immune activation. Endothelial cell dysfunction impairs endothelium-mediated blood vessel function7 leading to dysregulation of vascular tone, arterial stiffness and cardiovascular disease development. Endothelial dysfunction8 and increased arterial stiffening 9 may contribute to greater risk of CVD10. Identification of mechanisms underlying HIV-related endothelial dysfunction may lead to the development of therapeutic strategies against HIV-associated pathologies.

Continuous expression of HIV-encoded proteins in patients on ART with undetectable HIV RNA is a potential etiology for HIV-related CVD. HIV-Nef is a myristoylated intracellular HIV protein adept at hijacking host cell signaling machinery and is released in circulating extracellular vesicles (EV)11, 12, thereby allowing widespread dissemination. HIV-Nef’s ability to persist in EV is conserved, with HIV-Nef+ EV found in the SIV macaque model13. HIV-Nef persists in multiple immune cell types, including circulating CD4 T-cells, CD8 T-cells, and B cells14 and in lung alveolar macrophages12. HIV-Nef has been isolated in the extracellular compartment of plasma15, 16 and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid12. HIV-Nef also shows persistence in several tissues including the heart17, brain18 and lung12. Thus, HIV-Nef is a likely etiologic agent for causing end-organ diseases linked to endothelial dysfunction since multiple studies have shown its capacity to induce endothelial cell apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction19–21.

HIV-Nef directly activates small GTPase Rac1 which in turn promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production22, 23. Subsequently, ROS formation contributes to vascular dysfunction by promoting pro-apoptotic pathways and downregulating eNOS15. Recent studies have suggested the use of statins, which by inhibiting the geranylgeranylation of Rac124, can block NADPH oxidase mediated ROS production. In fact, statin treatment protects HIV+ patients from the development of CVD to a larger extent than can be attributed to LDL reduction25, 26. Specifically, atorvastatin and pitavastatin have modest to no drug-drug interactions with ART, making them attractive drugs to prescribe to HIV+ patients27, 28. As such, pitavastatin is being studied in REPRIEVE, an ongoing randomized controlled study to prevent cardiovascular diseases in HIV+ patients29.

In this current study, we have identified pathways by which HIV-Nef may exert negative effects on endothelial cells, with a focus on the role of Rac1 signaling in HIV-Nef dissemination and its downstream consequences. We further analyzed the role of endothelial expression of HIV-Nef on endothelial dysfunction and vascular pathologies in a murine model in vivo.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files.

Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells (HCAEC) were cultured in EGM2MV. HIV-Nef was expressed in cells via transfection or addition of HIV-Nef+ extracellular vesicles. Extracellular vesicles were isolated from plasma or supernatants of HIV-Nef transfected cells using serial centrifugation. PBMC and plasma was obtained from patients after acquiring informed consent in accordance with IRB approval. Transgenic endothelial HIV-Nef expression was under control of VE-Cadherin promoter. Animal experiments were performed after obtaining IACUC approval.

Detailed methods are available in the online supplement.

RESULTS

PBMC and EV from HIV+ patients on ART induce endothelial dysfunction

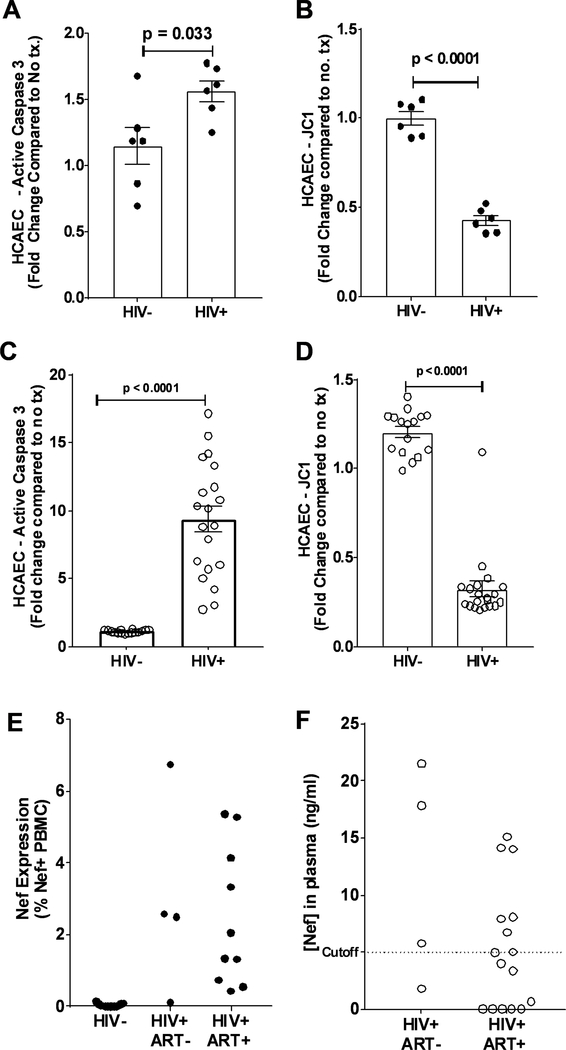

Earlier we published that co-cultivation of HIV infected T cells induce ROS formation and apoptosis in HCAEC21. Here we investigated whether HIV+ patient-derived PBMC also induce endothelial dysfunction in HCAEC. Overnight incubation of PBMC from HIV+ patients prominently increased caspase 3 activation (Figure 1A) and promoted mitochondrial depolarization (Figure 1B) when compared to control PBMC from HIV- patients.

Figure 1: HIV-Nef protein persists in virologically suppressed HIV+ patients.

Addition of PBMCs (A and B, closed circles) and extracellular vesicles (C and D, open circles) from HIV+ patients to HCAEC induced endothelial cell apoptosis as measured by active caspase 3 levels (A and B) and mitochondrial depolarization using JC-1 (C and D). HIV-Nef protein persists in PBMCs (E) and plasma (F) of HIV+ patients either treatment naïve or on antiretroviral therapy. Dotted line indicates cutoff (5ng/ml) based on HIV- control plasma and previously published results43. Statistical significance between groups was determined using Student’s T-Test with Welch’s correction. Raw p-value is indicated in graphs.

Using the same assays, we next questioned whether extracellular vesicles (EV) isolated from HIV+ patients can damage HCAEC. Indeed, overnight incubation of HCAEC with HIV+ plasma EV significantly increased caspase 3 activation (Figure 1C) and induced mitochondrial depolarization (Figure 1D) compared to EV from healthy individuals. When EV from ART naïve (ART-) and ART treated (ART+) HIV+ patients were compared, no significant differences in HCAEC caspase 3 activation or mitochondrial depolarization were observed (Online Figure I–B).

PBMC and EV from HIV+ patients on ART contain HIV-Nef protein

Previously12, 21 we have shown that HIV-Nef protein persists in PBMC and BAL cells from HIV+ patients in CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and alveolar macrophages. Therefore, we queried whether the effects of PBMC and EV on HCAEC could be explained by the presence of HIV-Nef protein. To detect HIV-Nef protein, we employed an approach we recently developed to cope with the high rate of mutation of the HIV using three monoclonal antibodies (SN20, EH1, and 3D12) targeting different HIV-Nef epitopes12. FACS analysis of PBMC from fourteen HIV+ patients demonstrated persistent HIV-Nef protein in 3 out of 4 treatment-naïve and 9 out of 10 ART-treated HIV patients (Figure 1E). All 13 HIV- patients had undetectable HIV-Nef showcasing the specificity of our assay. Interestingly, HIV-Nef was detected in HIV+ patients on various ART regimens (Online Table I) suggesting that HIV-Nef persistence in PBMC may be independent of ART strategy.

We detected HIV-Nef protein in plasma from ART naïve (ART-, n=4) and ART treated (ART+, n=16) HIV patients. Analysis of patients on ART revealed that 7 were HIV-Nef-positive whereas 9 were not (Figure 1F), which agrees with a previous study showing 50% of HIV+ patients on ART have HIV-Nef-positive plasma samples16. Interestingly, EV from HIV-Nef positive plasma induced more endothelial caspase-3 activation than EV from HIV-Nef negative plasma (Online Figure I–C). This suggests that the pro-apoptotic activity in HIV patients is mediated by HIV-Nef.

Therefore, both the cellular and extracellular fractions of HIV+ patient blood contain HIV-Nef protein despite suppression of viral replication using ART. As such, blood HIV-Nef-positivity could be used to predict endothelial cell dysfunction.

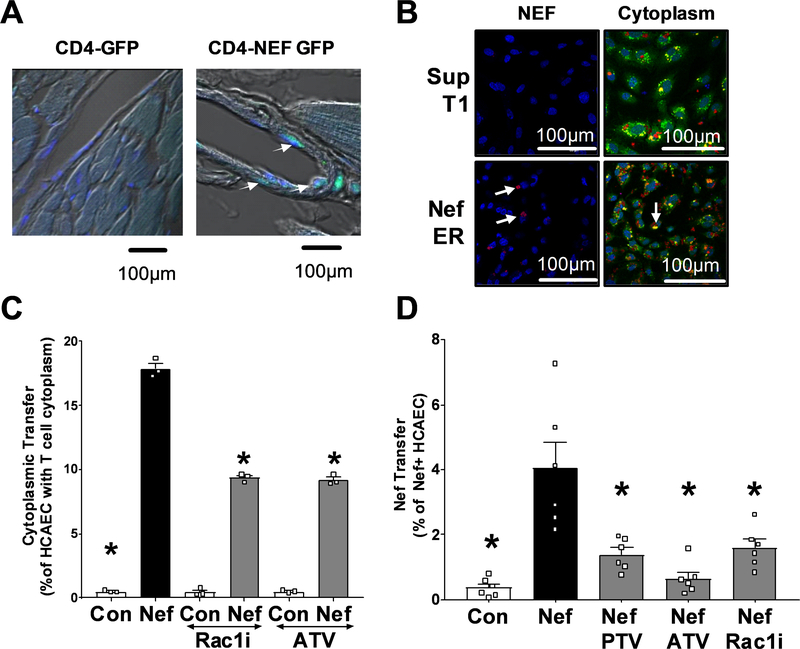

HIV-Nef increases cytosolic transfer from T cell to the endothelium

HIV-Nef protein promotes its own transfer from HIV infected CD4 T cells to the endothelium in vitro and ex vivo14, 21. Therefore, we investigated the mechanism used by HIV-Nef to facilitate the transfer of cytosol to endothelial cells. We confirmed our previous finding54 of cytosol transfer to the endothelium in a murine transgenic model expressing HIV-Nef but no other HIV protein. HIV-Nef and GFP are bi-directionally expressed in CD4 T cells allowing the use of GFP staining as a surrogate for cytoplasmic transfer from T cells to the endothelium. We observed endothelial GFP only in heart sections of the HIV-Nef-GFP transgenic mice but not in those mice only expressing GFP (Figure 2A right panel).

Figure 2: HIV-Nef protein promotes cytoplasmic transfer from T cells to coronary artery endothelial cells.

Heart sections of single CD4-GFP and double CD4-Nef-GFP transgenic mice were stained with αGFP mab (green). White arrows indicate T-Cell cytoplasm within endothelial lining (A). HIV-Nef protein transfer from SupT1 or Nef-ER T cells to HCAEC is visualized using anti-Nef EH1 mAB (left panels). Cytoplasmic transfer of Cell Tracker Deep Red Dye from T cells is seen in Calcein AM stained endothelial cells (right panels) (B). Quantification of cytoplasmic transfer (C) or HIV-Nef protein transfer (D) from T-Cells to HCAEC was quantified using FACS. ATV=5μmol/l atorvastatin; PTV=100nmol/l Pitavastatin; Rac1i = 5μmol/l NSC23766. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test. * denotes adjusted p-value<0.001 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar). Scale bars denote 100um.

To analyze the mechanism of how HIV-Nef induces cytoplasmic transfer from HIV-Nef expressing T cells to endothelial cells, we co-cultured Cell Tracker Deep Red labeled SupT1 T Cells with Calcein AM labeled HCAEC (Figure 2B). We used a tamoxifen-inducible HIV-Nef estrogen receptor (Nef-ER) model to mediate HIV-Nef-dependent activities12, 30. HIV-Nef activation in Nef-ER expressing SupT1 T cells increased cytoplasmic transfer (Figure 2B right panels) in a T cell concentration dependent fashion (Online Figure II–A) and was attenuated by both Rac1 inhibitor and atorvastatin (Figure 2C). Using confocal microscopy, we observed a significant increase in the uptake of vesicular structures containing T cell cytoplasm into HCAEC (Figure 2B right panel and Online Figure II–B). Concomitant with the cytoplasmic transfer from T cells, HIV-Nef was detected in HCAEC co-cultured with HIV-Nef-expressing T cells (Figure 2B left panels), which was significantly reduced with Rac1 inhibitor as well as pitavastatin and atorvastatin (Figure 2D).

This suggests that HIV-Nef expression enhances transfer of cytoplasm from T cells to endothelial cells in a process mediated by the small GTPase Rac1.

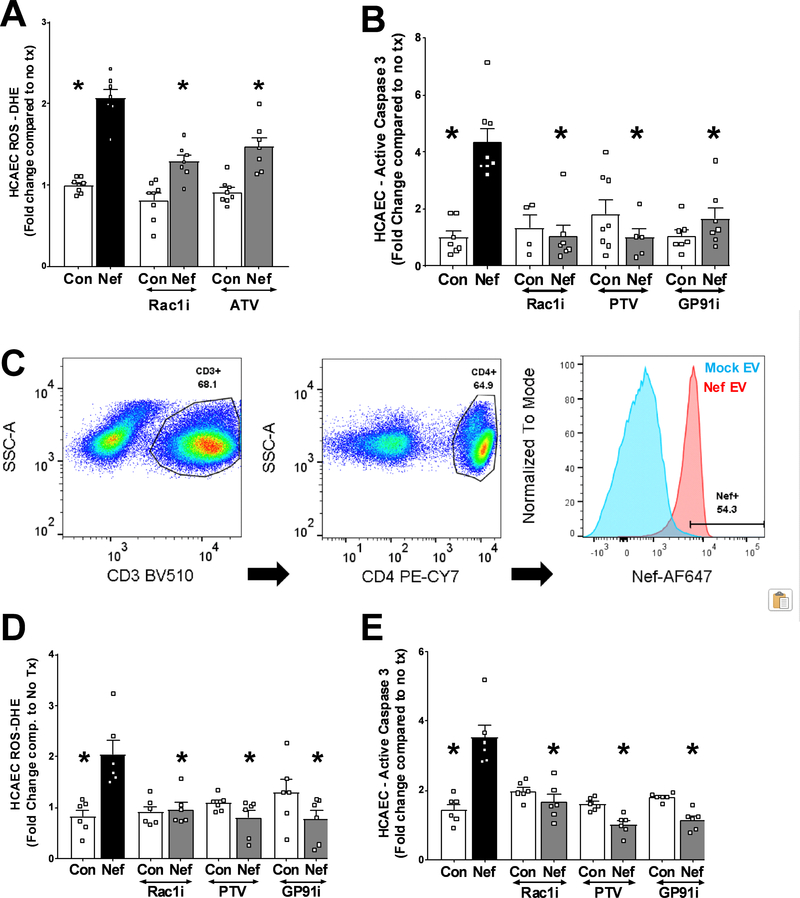

HIV-Nef expressing T cells induce endothelial cell dysfunction dependent on Rac1 activation

HIV-Nef protein is necessary and sufficient to induce ROS production which results in endothelial cell apoptosis 21. To gain insight into the mechanism mediating this process, we analyzed the importance of HIV-Nef-induced Rac1 activation previously shown to cause NADPH-dependent ROS production in cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage 31. Both transfection of HCAEC with HIV-Nef expressing plasmids (Online Figure III) and overnight co-culture with HIV-Nef-expressing SupT1 T cells (Figure 3A) induced ROS production in HCAEC, which could be ameliorated by Rac1 inhibition using both the small molecule selective inhibitor NSC23766 (that blocks Rac1 activation) and atorvastatin (reduces Rac1 trafficking to plasma membrane via inhibition of Rac1 geranylgeranylation32) (Figure 3A). As we had shown earlier 21, this HIV-Nef-induced ROS production was dependent on the NADPH oxidase complex as an inhibitory peptide against the GP91 subunit prevented caspase 3 activation after co-culture with HIV-Nef+ PBMC (Figure 3B). Following ROS imbalance, mitochondrial depolarization is considered a pathway towards apoptosis in cells. Rac1 inhibition (with both NSC23766 and statins) and NADPH oxidase inhibition (with the GP91 inhibitory peptide) ameliorated HIV-Nef-induced HCAEC mitochondrial dysfunction in endothelial cells after co-culture with HIV-Nef+ T cells (Online Figure IV–A). These treatments also blocked HIV-Nef-induced Caspase 3 activation (Figure 3C) and DNA fragmentation (Online Figures IV–C and IV–D), thereby implicating this signaling pathway in endothelial cell apoptosis.

Figure 3: Rac1 inhibition and statin treatment block HIV-Nef protein induced endothelial cell stress.

Co-culture of HIV-Nef expressing T cells (Nef) induced ROS production (A) and apoptosis (B) in HCAEC. HIV-Nef protein was taken up by CD45+/CD3+/CD4+ T cells when PBMC were treated with mock ev or HIV-Nef EV (Nef) for 2hr (Blue= mock, Red = Nef) (C). HIV-Nef EV treated PBMC induced ROS production (D) and caspase 3 activation (E) in HCAEC. ATV=5μmol/l atorvastatin; PTV=100nmol/l Pitavastatin; Rac1i = 5μmol/l NSC23766. GP91i = Inhibitory peptide 1μmol/l. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test. * denotes adjusted p-value<0.001 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar).

We next attempted to replicate our findings in Figure 1 of endothelial apoptosis induced by PBMC from HIV+ patients on ART with using a model of HIV-Nef+ PBMC. We treated PBMC from healthy donors with EV from HIV-Nef transfected (Nef) or mock transfected (Con) HEK293T cells for 2hr to create HIV-Nef+ PBMC (Figure 3C). These PBMC were co-cultured overnight with HCAEC resulting in Rac1 dependent (using Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 and pitavastatin) endothelial ROS formation (Figure 3D) which was accompanied by increased pro-apoptotic signaling (Figure 3E) and mitochondrial depolarization (Online Figure IV–B). Blocking endothelial ROS formation via inhibition of the gp91 subunit of NADPH oxidase complex also prevented HCAEC apoptosis (Figure 3E).

HIV-Nef-positivity in T cells and PBMC potently induce endothelial cell dysfunction by upregulating endothelial ROS production in a Rac1 activation dependent fashion.

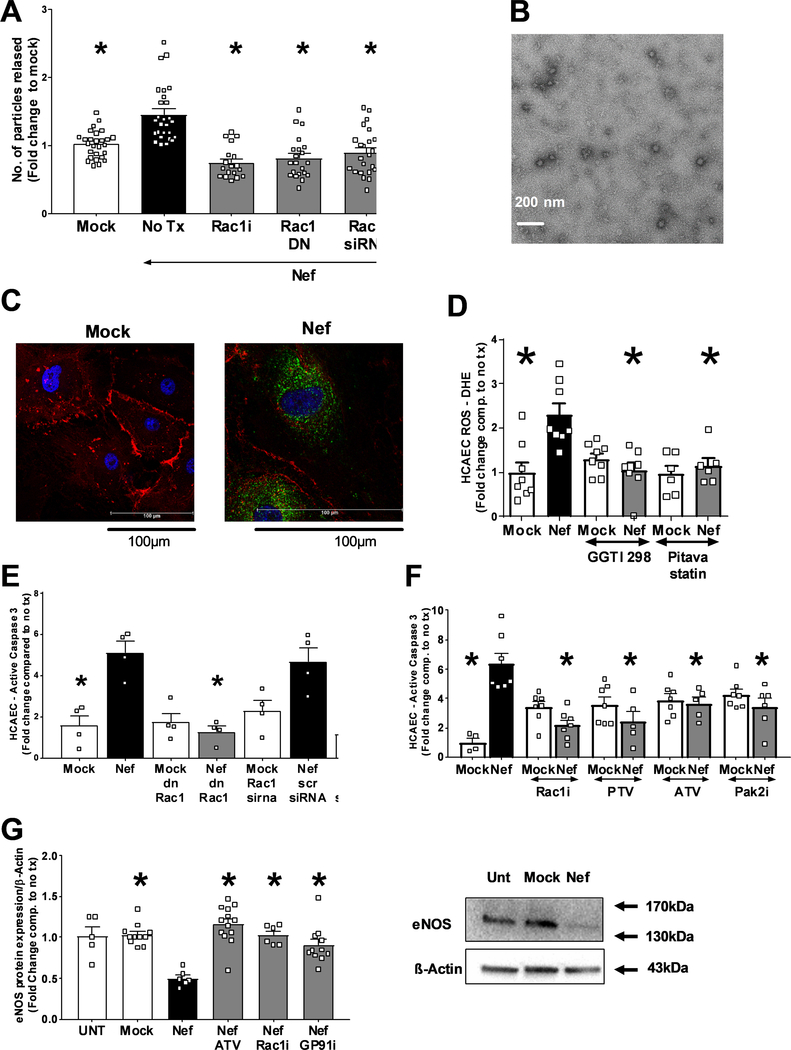

HIV-Nef+ extracellular vesicles are key mediators of HIV-Nef-induced cytosolic transfer to and dysfunction in endothelial cells

Since, EV have been suggested to mediate the transfer of HIV-Nef protein and cytoplasm to the endothelium12, we hypothesized that Rac1 inhibition could block HIV-Nef-increased EV release. Rac1 inhibition by a chemical inhibitor (NSC23766), a dominant negative Rac1 (RacT17N), Rac1 siRNA (Online Figure V), and pitavastatin all impeded HIV-Nef’s ability to increase EV release from HIV-Nef-expressing HEK293T cells (Figure 4A and Online Figure VI–A). The presence of extracellular vesicles was characterized using transmission electron microscopy (Figure 4B), Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis and Western blotting for membrane associated protein, HIV-Nef and the tetraspanin CD9 (Online Figure VI–B). Therefore, HIV-Nef utilizes a Rac1 activation dependent pathway to increase communication between T cells and the endothelium.

Figure 4: HIV-Nef EV induce endothelial cell apoptosis.

(A) HIV-Nef transfection into HEK293T increases the amount of EV released. EV morphology was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (B) with scale bar denoting 200nm. (C) Addition of HIV-Nef+ EV transferred HIV-Nef protein to HCAEC (Green = αNef EH1mab; Red = PECAM; Blue = DAPI; Scale bars = 100 μm). HIV-Nef+ EV promotes ROS production (D), apoptosis (E and F) and downregulation of eNOS (G) in HCAEC. ATV=5μmol/l atorvastatin; PTV=100nmol/l pitavastatin; Rac1i = 5μmol/l NSC23766. GP91i = Inhibitory peptide 1μmol/l; Pak2i = 5μmol/l FRAX597 GGTI-298 = 5μmol/l. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test. * denotes adjusted p-value<0.001 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar) # denotes p-value<0.0001 compared to HIV-Nef scr siRNA.

We have previously demonstrated that direct contact between T cells21 or PBMC14 from HIV+ patients and HCAEC facilitated enhanced transfer of HIV-Nef protein into endothelial cells. Here we tested whether EV could mediate this effect. First, we isolated HIV-Nef protein in the EV fraction of HIV-Nef transfected HEK 293T (Online Figure VIB) and showed that these HIV-Nef+ EV could transfer HIV-Nef protein into HCAEC after 2 hours (Figure 4C). We had earlier shown that transfection of HEK293T with wt SF2 HIV-Nef but not Pak2 activation deficient mutant produced HIV-Nef+ EV12. Using this model, we could show that HIV-Nef presence in EV cargo was necessary to induce HCAEC apoptosis (Online Figure VII). The uptake of HIV-Nef+ EV resulted in increased ROS production in HCAEC after further incubation overnight, which could be blocked with Rac1 inhibition. NADPH oxidase mediated this effect since inhibition with GP91 inhibitory peptide abrogated HIV-Nef induced ROS production (Online Figure VIII–A).

Blocking Rac1 activity using transfection with dominant negative mutant RacT17N and Rac1 siRNA also nullified HIV-Nef EV-induced endothelial ROS production (Online Figure VIII–A). Furthermore, incubation of HCAEC cells with HIV-Nef+ EV resulted in endothelial apoptosis (Figure 4E and 4F) and mitochondrial depolarization (Online Figure VIII–B). HIV-Nef induced Caspase-3 activation could be prevented by both atorvastatin and pitavastatin (Figure 4E). Of note, statins were comparable to the Rac1 activation inhibitor-NC23766 (Online Figure VIII–C) and Rac1 geranylgeranylation inhibitor- GGTI-298 (Fig.4D) in their ability to block HIV-Nef induced HCAEC ROS production. Thus, statins, which also inhibit Rac1 geranylgeranylation, is an effective treatment to block HIV-Nef induced endothelial stress.

HIV-Nef induced PAK2 activation is an important element for endothelial dysfunction that follows uptake of HIV-Nef+ EV into human lung microvascular endothelial cells33. In this regard, Rac1 inhibition showed potency in abrogating HIV-Nef+ EV induced HCAEC apoptosis comparable to the PAK2 inhibitor, FRAX597. We confirmed the importance of the Rac1-Pak2 signaling axis in HCAEC apoptosis using a second source of HIV-Nef+ EV, namely HIV-Nef-ER expressing SupT1 T cells (Online Figure IX).

The uptake of HIV-Nef potently downregulated eNOS expression in HCAEC (Figure 4G), suggesting that transfer of HIV-Nef to HCAEC could impair endothelium mediated vasodilation. Of note, atorvastatin treatment blocked HIV-Nef induced eNOS downregulation.

Our data strongly suggest that treatment with HIV-Nef+ EV may cause endothelial cell dysfunction contingent on Rac1 activation dependent ROS production by the NADPH oxidase complex.

HIV-Nef+ extracellular vesicles enhance T cell adhesion to the endothelium

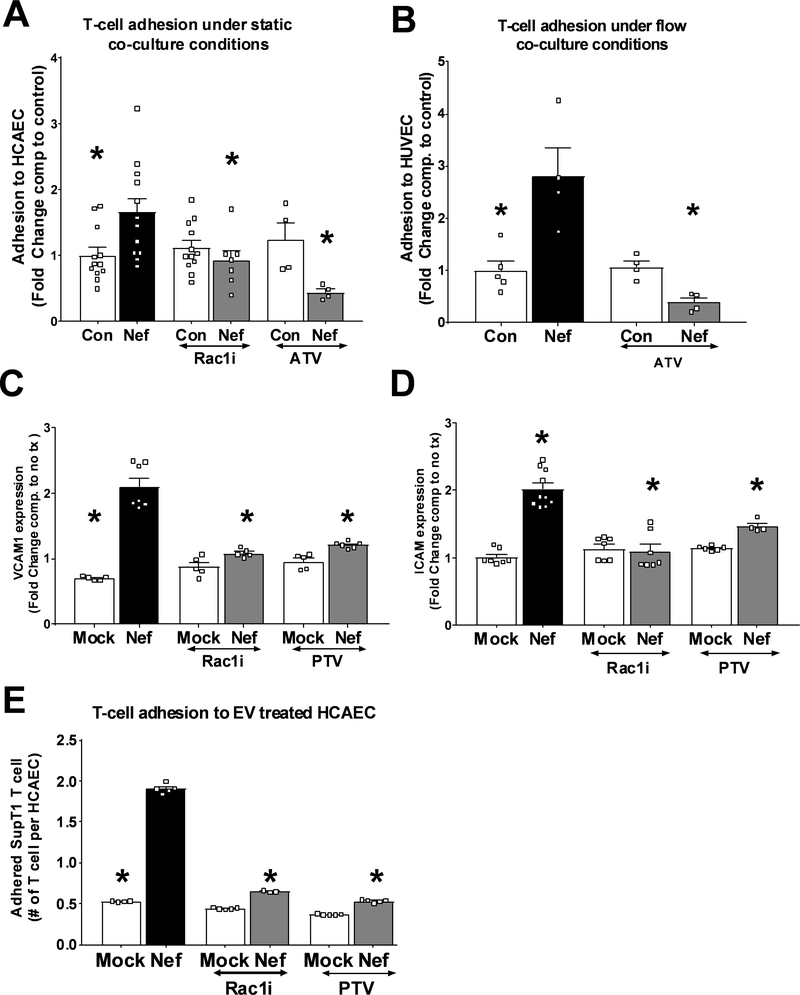

HIV-Nef protein persists in a variety of immune cell subsets, including circulating CD4 T cells, despite ART-induced virologic suppression14. Since HIV-Nef expression has been shown to regulate cellular motility34, we hypothesized that uptake of HIV-Nef+ EV from plasma would enhance CD4 T cell adhesion to an endothelial monolayer. SupT1 T cells expressing HIV-Nef showed increased adhesion to HCAEC monolayer compared to control T cells (Figure 5A) under static conditions. HIV-Nef is known to activate the small GTPase Rac1, a regulator of cellular adhesion35. Figure 5A shows that inhibition of Rac1 activation using chemical inhibitor NSC23766 and statin treatment blocked the ability of HIV-Nef to increase T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. Because T cell interaction with the endothelium in vivo is subject to flow, we studied adhesion of T cells to the endothelial monolayer under conditions that recapitulate the shear stress observed in coronary arteries (Figure 5B). Using fluorescence microscopy, we quantified the number of cells that adhered to HUVEC monolayer over one hour. Similar to static conditions, HIV-Nef-expressing T cells displayed increased attachment to endothelial monolayer compared to control T-cells which was suppressed by atorvastatin.

Figure 5: HIV-Nef expression enhances interaction between T-cell and endothelial cells.

Compared to control SupT1 T cells (SupT1), HIV-Nef expressing T cells (Nef-ER) displayed increased adhesion to HCAEC under static (A) and to HUVEC under flow (B) conditions. HCAEC treated 24hr with 3μg/ml Nef EV showed increased VCAM1 (C) and ICAM1 (D) surface expression as determined by FACS. T-cell adhesion to HCAEC pre-treated with 3μg/ml of mock ev or HIV-Nef+ EV in the presence of Rac1 inhibitors (E). ATV=5μmol/l atorvastatin; PTV=100nmol/l pitavastatin; Rac1i = 5μmol/l NSC23766. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test. * denotes adjusted p-value <0.001 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar).

Following the transfer of HIV-Nef protein to endothelial cells when HIV-Nef+ EV are added to HCAEC (Figure 4C), we explored whether exposure to HIV-Nef+ EV enhance adhesion of lymphocytes to the endothelium. First, we assessed the expression of adhesion protein being responsible for rolling (E-selectin, P-selectin) and firm adhesion (VCAM1, ICAM1)36 in HCAEC after treatment with HIV-Nef+ EV. We found that addition of HIV-Nef+ EV (Figure 5C, 5D and Online Figure X–A and X–B) to HCAEC upregulated all four adhesion mediators. This in turn enhanced adhesion of control SupT1 T cells (Figure 5E). Importantly, Rac1 inhibition with NSC23766 and pitavastatin inhibited HIV-Nef-induced upregulation of adhesion markers as well as adhesion of CD4 T cells to HIV-Nef EV-treated HCAEC. These data demonstrate that HIV-Nef expression promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells in a Rac1-dependent fashion regardless of whether the HIV-Nef protein is present on T cells or endothelial cells.

HIV-Nef EV induce premature senescence in Endothelial Colony Forming Cells due to cleavage of transmembrane TNFα

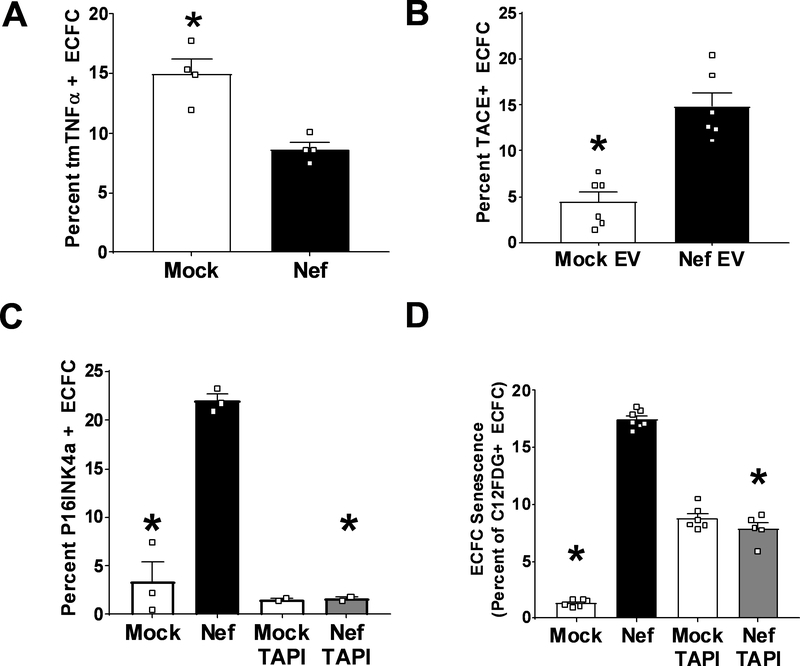

Recently, we have shown that plasma of HIV+ patients independent of ART can impair endothelial cell function in terms of network formation of cord blood-derived endothelial colony forming cells (ECFC) 37. ECFC were chosen since these are highly proliferative endothelial cells that play an important role in the repair of damaged vasculature 38. We investigated whether HIV-Nef in EV could serve as a factor in acellular plasma that is capable of inducing ECFC dysfunction. Indeed, HIV-Nef+ EV induced the expression of two cellular senescence markers, namely the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a (Figure 6C) and lysosomal β-galactosidase activity (Figure 6D). To address the underlying mechanism through which HIV-Nef induces premature senescence in this endothelial progenitor population, we analyzed the ability of HIV-Nef+ EV to regulate transmembrane TNFα (tmTNFα), which we had earlier shown to be critical for preserving the replicative potential of ECFC through TNFR2 signaling39. We observed a strong downregulation of tmTNFα in ECFC treated with HIV-Nef+ EV (Figure 6A). This could be attributed to the increased activity of ADAM17/TNFα Converting Enzyme (TACE) upon treatment of ECFC with HIV-Nef+ EV (Figure 6B). As previously analyzed in depth39, tmTNFα protects ECFC from premature senescence. Therefore, we evaluated ECFC senescence in the presence of TACE inhibitor TAPI. Indeed, TAPI treatment effectively blocked HIV-Nef’s ability to promote premature senescence in ECFC as evidenced by reduced p16INK4a expression (Figure 6C) and lysosomal β galactosidase activity (Figure 6D). These results support potential links between vascular inflammation, HIV-Nef activity, and exhaustion of vascular repair cells.

Figure 6: HIV-Nef EV downregulates tmTNFα to induce premature ECFC senescence.

Addition of HIV-Nef+ EV downregulates surface expression of transmembrane TNFα (A) via upregulation of TACE activity (B). HIV-Nef+ EV induced ECFC senescence as evidenced by p16INK4a induction (C) and lysosomal β-galactosidase activity (D). TAPI = 10μmol/l. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test or Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. * denotes adjusted p-value <0.05 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar).

HIV-Nef EV induce endothelial dysfunction in Endothelial Colony Forming Cells via induction of Rac1-dependent ROS production

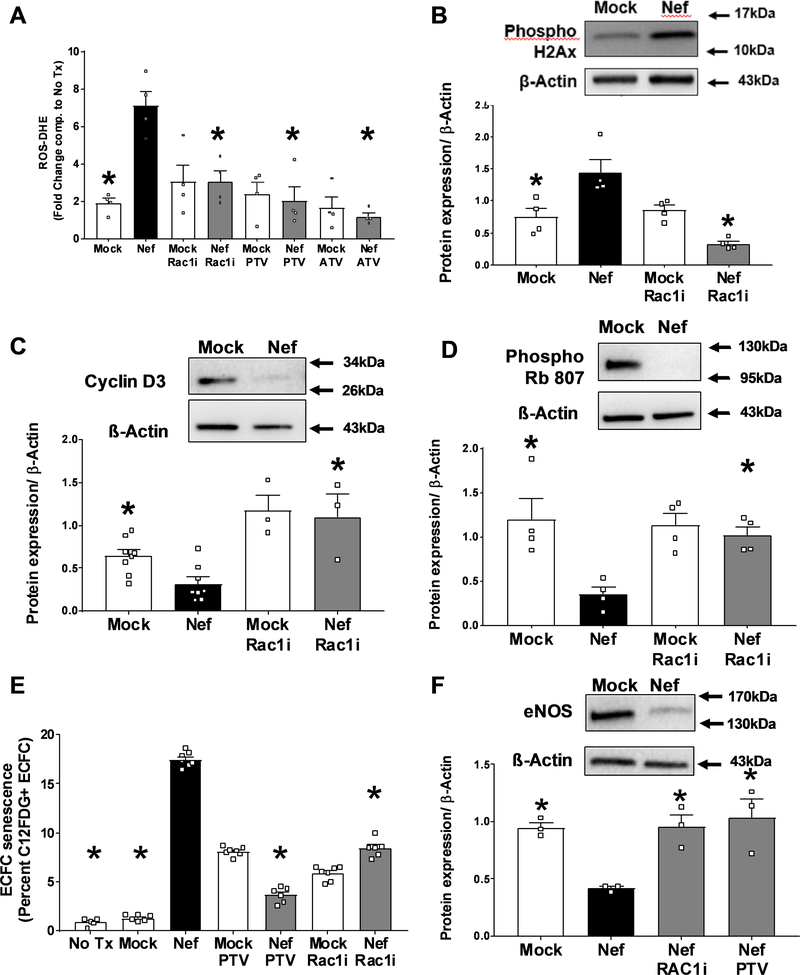

We hypothesized that HIV-Nef+ EV addition would lead to ECFC dysfunction by upregulating Rac1-dependent ROS production. Indeed, HIV-Nef+ EV increased ROS production in ECFC which could then be completely abrogated with Rac1 inhibition using the chemical inhibitor NSC23766 and both atorvastatin and pitavastatin (Figure 7A). EV isolated from cells transfected with the HIV-Nef PAK2 activation deficient mutant (F195R) and treatment with Rac1 geranylgeranylation inhibitior GGTI-298 did not induce ECFC ROS production (Online Figure XI–A), thereby providing support for a Rac1 dependent mechanism for HIV-Nef+ EV induced ROS production as PAK2 is a Rac1 downstream effector. Following increased ROS production, we quantified DNA damage in ECFC by measuring phosphorylated histone 2Ax using both FACS (Online Figure XII) and western blot. Histone 2Ax is phosphorylated at Ser139 upon double-stranded DNA breaks. Rac1 inhibition successfully blocked HIV-Nef+ EV-induced DNA damage (Figure 7B).

Figure 7: HIV-Nef+ EV induce ECFC dysfunction.

Addition of HIV-Nef EV induce ROS production (A) and double stranded DNA breaks (B) in ECFC quantified using DHE staining and phosphorylated histone 2Ax respectively. HIV-Nef+ EV downregulates of Cyclin D3 (C) and Phospho Rb 807 (D). HIV-Nef+ EV induces premature senescence in ECFC quantified using C12FDG staining to measure lysosomal β-galactosidase activity (E). HIV-Nef+ EV downregulates eNOS protein expression in ECFC (F). ATV=5μmol/l atorvastatin; PTV=100nmol/l pitavastatin; Rac1i = 5μmol/l NSC23766. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Post-hoc test or Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. * denotes adjusted p-value <0.05 compared to HIV-Nef group (black bar).

We hypothesized that ROS formation and DNA damage would decrease ECFC proliferative capacity by inhibiting cell cycle progression. We observed G1 cell cycle arrest as evidenced by decreased cell cycle checkpoint regulator – cyclin D3 (Figure 7C). Cyclin D3 downregulation resulted in the lack of phosphorylation of Rb protein at sites Ser795 (Online Figure XIII) and Ser807 (Figure 7D), which controls cell cycle progression from G1 to S-phase. Rac1 inhibition prevented HIV-Nef EV-induced cell cycle arrest. Cell cycle arrest in senescent cells is associated with increased lysosomal accumulation. In this regard, we measured cellular senescence using lysosomal β-galactosidase activity using C12FDG dye staining. HIV-Nef EV potently induced ECFC senescence, which was abrogated with Rac1 inhibition and statin treatment (Figure 7E). Similarly, EV isolated from HIV-Nef F195R mutant transfected HEK did not induce premature senescence (Online Figure XI–B). Finally, Nef induced ECFC dysfunction was also confirmed by finding reduced protein expression of eNOS, which could be also rescued with Rac1 inhibition using both NSC23766 and pitavastatin (Figure 7F).

Therefore, HIV-Nef+ EV induce ECFC dysfunction by promoting ROS mediated DNA damage that results in cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence.

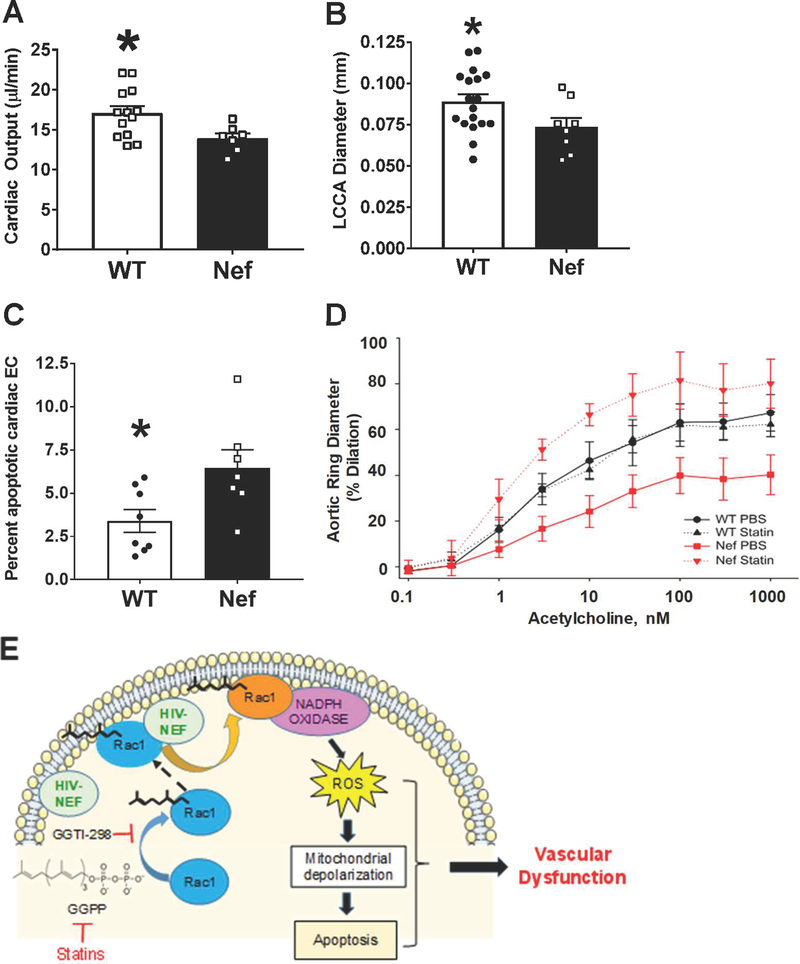

Endothelial HIV-Nef expression leads to vascular pathologies in a transgenic murine model

While HIV infection is limited to CD4 T cell and macrophages, HIV-Nef protein is capable of mediating its own transfer to endothelial cells21. To determine if endothelial HIV-Nef is sufficient to cause vascular pathologies, we generated transgenic mice expressing HIV-Nef in endothelial cells under control of the VE-Cadherin promoter33.

There were no apparent changes in heart/body weight ratio at 4 and 5 months of age in these transgenic mice. However, we did observe a statistically significant decrease in cardiac output (Figure 8A) in HIV-Nef transgenic mice as compared to WT littermates. In addition, the diameter of the left circumflex carotid artery (Online Figure XIV) was significantly smaller in HIV-Nef transgenic mice (Figure 8B). This finding suggests endothelial dysfunction accompanied the reduction in cardiac output.

Figure 8: Endothelial expression of HIV-Nef in VE-Cadherin promoter driven HIV-Nef transgenic mice induces cardiovascular dysfunction.

Echocardiography was used to evaluate Left Circumflex Coronary Artery (LCCA) diameter (A) and cardiac output (B). Endothelial cells in the heart showed increased apoptosis measured through cleaved caspase 3 staining in CD31+/CD45- endothelial cells (C). Aortic rings isolated from WT and HIV-Nef expressing mice treated with vehicle or 5mg/kg atorvastatin (daily for 3 weeks) were preconstricted using phenylephrine and endothelium dependent vasodilation was measured in response to increasing concentration of acetylcholine (D). Schematic describes proposed mechanism of HIV-Nef induced endothelial dysfunction (E). Groups were compared using Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. * denotes adjusted p-value<0.05 compared to HIV-Nef group.

Consistent with our in vitro data on HIV-Nef-induced endothelial dysfunction, we observed an elevated level of endothelial cell apoptosis in the heart of HIV-Nef transgenic mice when compared to HIV-Nef- littermates (Figure 8C). We then assessed endothelial-specific vascular function in HIV-Nef transgenic mice by measuring the dilation of pre-constricted aortic rings in response to acetylcholine. Aortas from 3 month-old HIV-Nef transgenic animals showed dramatically impaired ability to dilate in an endothelial-dependent manner. Importantly, aortas from HIV-Nef transgenic animals treated for three weeks with atorvastatin showed normalized dilation in response to acetylcholine (Figure 8D).

Similarly, HIV-Nef expression by CD4+ cells impacted the endothelium. These CD4-Nef tg mice also displayed impaired endothelium mediated vasodilation as evidenced by small responses to acetylcholine in aortic rings isolated from HIV-Nef tg mice but not their WT littermates (Online Figure XV).

Therefore, transfer of HIV-Nef to the endothelium is sufficient to induce a variety of vascular pathologies clinically relevant to those observed in HIV+ patients on ART (Figure 8E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that PBMC and plasma EV isolated from HIV+ patients induced apoptosis in HCAEC. Moreover, HIV-Nef+ EV from plasma obtained from patients virally suppressed on ART induced HCAEC dysfunction, thereby supporting a role for persistent HIV-Nef on vascular pathology. Although we did not analyze factors like other viral proteins and inflammatory cytokines as reviewed by Marincowitz et al40 that could influence vascular dysfunction in HIV+ patients on ART, the following lines of evidence suggest that HIV-Nef may contribute to the persistently heightened cardiovascular risk observed in ART-treated HIV patients: 1. compared to the other early response HIV genes rev and tat, HIV-Nef continues to be produced at high levels even when patients are receiving virologically suppressive ART41; 2. HIV-Nef is the only HIV protein that has been found in the blood circulation of patients on ART15, 16, and 3. Transgenic endothelial HIV-Nef expression causes similar endothelial dysfunction in vivo (this study and Chelvanambi et al.12).

While HIV itself only infects a few human cell types, the ability of Nef+ EV to transfect other cell types could possibly explain the widespread identification of HIV-Nef in PBMC14, the heart21 and endothelial cells42, 43As we have shown that HIV-Nef transfer to endothelial cells cause their dysfunction, this mechanism may lead to various end-organ pathologies in the aging HIV+ population. Interestingly, we also demonstrate in vitro that HIV-Nef transfer to endothelial cells is prevented by statins, which suggests that these currently available drugs could help prevent HIV-Nef dependent endothelial dysfunction in ART treated HIV+ patients.

Immune cell-mediated endothelial cell activation is a major contributor to endothelial dysfunction in HIV+ patients44. HIV-Nef is capable of increasing endothelial cell adhesion markers such as ICAM-1 in an ERK signaling dependent fashion45. Here we show that Nef+ EV independently upregulate T cells adhesion to a HCAEC monolayer via increased surface expression of adhesion markers (Figure 5). HIV-Nef+ EV may be a major factor in inducing lymphocyte adhesion to the endothelium as a secreted protein from T cells in patients on ART. Our demonstration that Rac1 inhibition using statins was capable of preventing upregulation of these adhesion markers to block HIV-Nef-induced adhesion of T cells to the endothelium suggests that statin treatment could be a viable strategy to reduce vascular inflammation in HIV+ patients.

Cardiovascular dysfunction46, impaired endothelium-mediated vasodilation8 and arterial stiffening47 are well-established phenotypes in the HIV patient population. Similarly, endothelial dysfunction has been characterized in mammals including transgenic rats expressing HIV proteins48, porcine pulmonary arterial rings treated ex vivo with HIV-Nef 49 and SHIV-infected macaques50. Our study shows that endothelial HIV-Nef independently impaired endothelium-mediated aortic ring vasodilation in two different HIV-Nef transgenic murine models, even in the absence of other HIV-associated confounding variables, including direct ART drug effects, immune cell activation, and viral replication.

The first murine model expressed endothelial HIV-Nef under the control of CD4 promoter elements (CD4c) and is already well-described for its induction of AIDS and cardiac pathology51. We used this model to address production of HIV-Nef-induced EV. Reproducing observations from our previous publication, we observed cytosol from CD4 T cells to be present within the endothelium of the cardiac vasculature (Figure 2A). These mice display endothelial dysfunction when tested in our ex vivo arterial dilatation model (Online Figure XV). This cardiovascular phenotype could also be attributed to the transfer of HIV-Nef protein directly to cardiac myocytes as described by Gupta et. al17. In order to specifically address the effects of HIV-Nef transfer into endothelial cells we expressed HIV-Nef under control of the endothelial specific VE-cadherin promoter12. Using this mouse model we could replicate the most important cardiovascular findings with CD4c-Nef transgenic mice, namely vascular dysfunction and impaired cardiac output (Figure 8). Importantly this model reflects our in vitro findings that HIV-Nef expression in the endothelium is sufficient to initiate vascular dysfunction and that statins can reverse these effects.

We found that HIV-Nef protein can induce endothelial cell apoptosis due to increased ROS production by the NADPH Oxidase complex due to Rac1 activation. Of clinical relevance is our finding that statins also mitigated this endothelial pathology both in vitro and in vivo.

One of the limitations of our study was the small number of treatment naïve patients included (n=4). Therefore, we could not detect any potentially statistically significant differences between plasma EV from these patients with those from the ART+ patients to induce HCAEC apoptosis (Online Figure I–A). However, we did find statistically significant differences between the HIV+ Nef+ and HIV+Nef- samples in their ability to induce HCAEC apoptosis (Online Figure I–C). When examining for potential associations between the collected medical histories of these patients (Online Table I) with the HIV-Nef-related results or which patients would be HIV-Nef+ vs. HIV-Nef-, we could not identify any (though we acknowledge we did not have data on route of HIV acquisition nor illicit drug use). We could not assess the relationship of smoking on our results since only non-smokers were purposefully enrolled. Larger studies are necessary to identify clinical factors predicting HIV-Nef persistence in HIV+ patients. However, our study lays the foundation that HIV-Nef persistence in plasma of HIV+ patients on ART could be used as a predictor for risk of developing endothelial dysfunction.

We have recently shown that plasma from both ART treated and untreated HIV+ patients impair angiogenic properties of ECFC52. This current study is the first to identify a virally encoded protein being capable of reducing eNOS and inducing premature senescence in this population of progenitor cells, which may thus further impair vascular function and repair. Future studies can study how chronic infection by other viruses impacts the endothelial progenitor cell population. The ability of statins to reverse HIV-Nef induced effects on ECFC in the current study is in line with other studies showing the benefits of statin treatment on endothelial progenitor populations in murine models53 and in clinical trials of statin intervention 54.

These findings are of particular interest as premature senescent cells which are positive for p16ink4A and senescence associated β-galactosidase (Figures 6 and 7) have been demonstrated to cause many features of human aging including cardiovascular dysfunction55. Our observation of NADPH oxidase mediated endothelial ROS production followed by decrease in eNOS protein expression was also reported in aging HUVEC15, 43. Combined with our observation that HIV-Nef induces premature senescence in endothelial progenitor cell populations, our study lends credence to the theory that end organ failure in HIV patients on ART is a disease of accelerated aging56.

In conclusion, HIV-Nef protein persists in HIV patients on ART at levels comparable to ART naïve patients. Our findings suggest that HIV-Nef uses a Rac1 mediated pathway to induce endothelial cell stress which in turn leads to endothelial dysfunction. The ability of statin treatment to block HIV-Nef mediated Rac1 signaling could help limit vascular dysfunction in HIV patients on ART and potentially delay the development of cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

HIV increases the risk of age-related disorders including cardiovascular disease.

HIV encodes a protein, Nef, which can be found encapsulated in extracellular vesicles in the blood.

HIV-Nef protein is necessary and sufficient to mediate HIV virus induced death of vascular endothelial cells.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

HIV-Nef protein is present in mononucleated peripheral blood cells of HIV+ individuals on anti-retroviral therapy at similar levels to treatment naive patients.

HIV-Nef protein in extracellular vesicles can result in arterial endothelial dysfunction; the latter can be reversed by treatment with statins.

HIV-Nef causes premature aging (senescence) in an endothelial progenitor cell population that helps regenerate blood vessels following injury, thus providing another novel mechanism of how HIV can contribute to vascular diseases.

Over 1.1 million Americans are HIV positive. Although they are protected against development of AIDS due to viral load suppressing anti-retroviral therapy (ART), these patients have a persistently increased risk for cardiovascular disease. In our study, we show that the HIV-secreted protein Nef remains present in aviremic HIV patients. Strategies are presented to extend these findings, i.e., we demonstrate that the Rac1 signaling pathway plays an important role for the transfer of HIV-Nef via extracellular vesicles into endothelial cells and their progenitors (named “endothelial colony forming cells” or ECFC). This same pathway is also responsible for HIV-Nef induced endothelial dysfunction in human coronary arterial endothelial cells and premature senescence in ECFC. Importantly, this study provides strong evidence that the Nef-Rac1-ROS pathway can be targeted using two different FDA approved statins (Atorvastatin and Pitavastatin) that have minimal drug-drug interactions with ART and are routinely prescribed to HIV+ patients for dyslipidemia. This study provides a rationale to prescribe statins, even to HIV+ patients without dyslipidemia, to reduce the risk of HIV-associated cardiovascular diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Nef-ER #31 Clone from Drs. Scott Walk, Kodi Ravichandran, and David Rekosh; Anti-HIV-1 SF2 Nef Monoclonal (EH1) from Dr. James Hoxie; Cat #2949; Anti-HIV-1 Nef Polyclonal from Dr. Ronald Swanstrom; pcDNA3.1SF2Nef (Cat #11431) from Dr. J. Victor Garcia; 1SF2NefF195R (Cat#11430) from Dr. J. Victor Garcia and pNL4-3 from Dr. Malcolm Martin. We appreciate the help of Dr. Ting Wang, Dr. Linden Green and Noelle Dahl.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This publication was made possible with support from the American Heart Association (16PRE27260181 to SC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH: 5R21HL120390-02 (MC, SKG) 1R01HL1 29843-01 (MC, AO, PJ), R01 HL141909-01A1 (ZP), NSF-CAREER Award No 1651385 (ZP), and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Award Number UL1TR002529 from the NIH, NCATS, and CTSA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EV

Extracellular vesicles

- HCAEC

Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells

- ECFC

Endothelial Colony Forming Cells

- ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Samir Gupta obtained travel support and personal/advisory fees from Gilead Sciences and GSK/ViiV Healthcare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paisible AL, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, Butt AA, Leaf DA, Budoff M, Rimland D, Bedimo R, Goetz MB, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crane HM, Gibert CL, Brown ST, Tindle HA, Warner AL, Alcorn C, Skanderson M, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. Hiv infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:209–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JA, Duncan MS, Alcorn CW, So-Armah K, Butt AA, Goetz MB, Tindle HA, Sico J, Tracy RP, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. Association of hiv infection and risk of peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francisci D, Giannini S, Baldelli F, Leone M, Belfiori B, Guglielmini G, Malincarne L, Gresele P. Hiv type 1 infection, and not short-term haart, induces endothelial dysfunction. AIDS. 2009;23:589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currier JS, Lundgren JD, Carr A, Klein D, Sabin CA, Sax PE, Schouten JT, Smieja M. Epidemiological evidence for cardiovascular disease in hiv-infected patients and relationship to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Circulation. 2008;118:e29–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schechter M, Deeks S, Amin J, Gilson R, Paredes R, Bakowska E, Engsig FN, Phillips A, Insight Smart ESG. Mortality in well controlled hiv in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the smart and esprit trials compared with the general population. AIDS. 2013;27:973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solages A, Vita JA, Thornton DJ, Murray J, Heeren T, Craven DE, Horsburgh CR Jr., Endothelial function in hiv-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1325–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:932–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schillaci G, De Socio GV, Pucci G, Mannarino MR, Helou J, Pirro M, Mannarino E. Aortic stiffness in untreated adult patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Hypertension. 2008;52:308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arenaccio C, Chiozzini C, Columba-Cabezas S, Manfredi F, Affabris E, Baur A, Federico M. Exosomes from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (hiv-1)-infected cells license quiescent cd4+ t lymphocytes to replicate hiv-1 through a nef- and adam17-dependent mechanism. J Virol. 2014;88:11529–11539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chelvanambi S, Bogatcheva N, Bednorz M, Agarwal S, Maier B, Alves NJ, Li W, Syed F, Saber MM, Dahl N, Lu H, Day RB, Smith P, Jolicoeur P, Yu Q, Dhillon NK, Weissmann N, Twigg Iii HL, Clauss M. Hiv-nef protein persists in the lungs of aviremic hiv patients and induces endothelial cell death. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNamara RP, Costantini LM, Myers TA, Schouest B, Maness NJ, Griffith JD, Damania BA, MacLean AG, Dittmer DP. Nef secretion into extracellular vesicles or exosomes is conserved across human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. MBio. 2018;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang T, Green LA, Gupta SK, Byrd D, Tohti A, Yu Q, Twigg IH, Clauss M. Intracellular nef protein detected in cd4+ and cd4- pbmcs from hiv patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JH, Schierer S, Blume K, Dindorf J, Wittki S, Xiang W, Ostalecki C, Koliha N, Wild S, Schuler G, Fackler OT, Saksela K, Harrer T, Baur AS. Hiv-nef and adam17-containing plasma extracellular vesicles induce and correlate with immune pathogenesis in chronic hiv infection. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:103–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferdin J, Goricar K, Dolzan V, Plemenitas A, Martin JN, Peterlin BM, Deeks SG, Lenassi M. Viral protein nef is detected in plasma of half of hiv-infected adults with undetectable plasma hiv rna. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta MK, Kaminski R, Mullen B, Gordon J, Burdo TH, Cheung JY, Feldman AM, Madesh M, Khalili K. Hiv-1 nef-induced cardiotoxicity through dysregulation of autophagy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranki A, Nyberg M, Ovod V, Haltia M, Elovaara I, Raininko R, Haapasalo H, Krohn K. Abundant expression of hiv nef and rev proteins in brain astrocytes in vivo is associated with dementia. AIDS. 1995;9:1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acheampong EA, Parveen Z, Muthoga LW, Kalayeh M, Mukhtar M, Pomerantz RJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef potently induces apoptosis in primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells via the activation of caspases. J Virol. 2005;79:4257–4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenassi M, Cagney G, Liao M, Vaupotic T, Bartholomeeusen K, Cheng Y, Krogan NJ, Plemenitas A, Peterlin BM. Hiv nef is secreted in exosomes and triggers apoptosis in bystander cd4+ t cells. Traffic. 2010;11:110–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T, Green LA, Gupta SK, Kim C, Wang L, Almodovar S, Flores SC, Prudovsky IA, Jolicoeur P, Liu Z, Clauss M. Transfer of intracellular hiv nef to endothelium causes endothelial dysfunction. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janardhan A, Swigut T, Hill B, Myers MP, Skowronski J. Hiv-1 nef binds the dock2-elmo1 complex to activate rac and inhibit lymphocyte chemotaxis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilhardt F, Plastre O, Sawada M, Suzuki K, Wiznerowicz M, Kiyokawa E, Trono D, Krause KH. The hiv-1 nef protein and phagocyte nadph oxidase activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42136–42143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oesterle A, Laufs U, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statins on the cardiovascular system. Circulation research. 2017;120:229–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo J, Lu MT, Ihenachor EJ, Wei J, Looby SE, Fitch KV, Oh J, Zimmerman CO, Hwang J, Abbara S, Plutzky J, Robbins G, Tawakol A, Hoffmann U, Grinspoon SK. Effects of statin therapy on coronary artery plaque volume and high-risk plaque morphology in hiv-infected patients with subclinical atherosclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e52–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aberg JA, Sponseller CA, Ward DJ, Kryzhanovski VA, Campbell SE, Thompson MA. Pitavastatin versus pravastatin in adults with hiv-1 infection and dyslipidaemia (intrepid): 12 week and 52 week results of a phase 4, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, superiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e284–e294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malvestutto CD, Ma Q, Morse GD, Underberg JA, Aberg JA. Lack of pharmacokinetic interactions between pitavastatin and efavirenz or darunavir/ritonavir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:390–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blonk M, van Beek M, Colbers A, Schouwenberg B, Burger D. Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction study between raltegravir and atorvastatin 20 mg in healthy volunteers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert JM, Fitch KV, Grinspoon SK. Hiv-related cardiovascular disease, statins, and the reprieve trial. Top Antivir Med. 2015;23:146–149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walk SF, Alexander M, Maier B, Hammarskjold ML, Rekosh DM, Ravichandran KS. Design and use of an inducibly activated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef to study immune modulation. J Virol. 2001;75:834–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olivetta E, Mallozzi C, Ruggieri V, Pietraforte D, Federico M, Sanchez M. Hiv-1 nef induces p47(phox) phosphorylation leading to a rapid superoxide anion release from the u937 human monoblastic cell line. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:812–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao H, Qin X, Ping D, Zuo K. Inhibition of rho and rac geranylgeranylation by atorvastatin is critical for preservation of endothelial junction integrity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelvanambi S, Bogatcheva NV, Bednorz M, Agarwal S, Maier B, Alves NJ, Li W, Syed F, Saber MM, Dahl N, Lu H, Day RB, Smith P, Jolicoeur P, Yu Q, Dhillon NK, Weissmann N, Twigg Iii HL, Clauss M. Hiv-nef protein persists in the lungs of aviremic patients with hiv and induces endothelial cell death. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2019;60:357–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamas-Murua M, Stolp B, Kaw S, Thoma J, Tsopoulidis N, Trautz B, Ambiel I, Reif T, Arora S, Imle A, Tibroni N, Wu J, Cui G, Stein JV, Tanaka M, Lyck R, Fackler OT. Hiv-1 nef disrupts cd4(+) t lymphocyte polarity, extravasation, and homing to lymph nodes via its nef-associated kinase complex interface. J Immunol. 2018;201:2731–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen HH, Yu HI, Cho WC, Tarn WY. Ddx3 modulates cell adhesion and motility and cancer cell metastasis via rac1-mediated signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2015;34:2790–2800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones DA, McIntire LV, Smith CW, Picker LJ. A two-step adhesion cascade for t cell/endothelial cell interactions under flow conditions. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2443–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta SK, Liu Z, Sims EC, Repass MJ, Haneline LS, Yoder MC. Endothelial colony-forming cell function is reduced during hiv infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2019;219:1076–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, Meade V, Fenoglio A, Mortell K, Pollok K, Ferkowicz MJ, Gilley D, Yoder MC. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104:2752–2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green LA, Njoku V, Mund J, Case J, Yoder M, Murphy MP, Clauss M. Endogenous transmembrane tnf-alpha protects against premature senescence in endothelial colony forming cells. Circ Res. 2016;118:1512–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marincowitz C, Genis A, Goswami N, De Boever P, Nawrot TS, Strijdom H. Vascular endothelial dysfunction in the wake of hiv and art. FEBS J. 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer M, Joos B, Niederost B, Kaiser P, Hafner R, von Wyl V, Ackermann M, Weber R, Gunthard HF. Biphasic decay kinetics suggest progressive slowing in turnover of latently hiv-1 infected cells during antiretroviral therapy. Retrovirology. 2008;5:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marecki JC, Cool CD, Parr JE, Beckey VE, Luciw PA, Tarantal AF, Carville A, Shannon RP, Cota-Gomez A, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Flores SC. Hiv-1 nef is associated with complex pulmonary vascular lesions in shiv-nef-infected macaques. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JH, Ostalecki C, Zhao Z, Kesti T, Bruns H, Simon B, Harrer T, Saksela K, Baur AS. Hiv activates the tyrosine kinase hck to secrete adam protease-containing extracellular vesicles. EBioMedicine. 2018;28:151–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nordoy I, Aukrust P, Muller F, Froland SS. Abnormal levels of circulating adhesion molecules in hiv-1 infection with characteristic alterations in opportunistic infections. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan Y, Liu C, Qin X, Wang Y, Han Y, Zhou Y. The role of erk1/2 signaling pathway in nef protein upregulation of the expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in endothelial cells. Angiology. 2010;61:669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinha A, Ma Y, Scherzer R, Hur S, Li D, Ganz P, Deeks SG, Hsue PY. Role of t-cell dysfunction, inflammation, and coagulation in microvascular disease in hiv. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sevastianova K, Sutinen J, Westerbacka J, Ristola M, Yki-Jarvinen H. Arterial stiffness in hiv-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:925–935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen L, Parker I, Sutliff RL, Platt MO, Gleason RL, Jr. Endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffening, and intima-media thickening in large arteries from hiv-1 transgenic mice. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41:682–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duffy P, Wang X, Lin PH, Yao Q, Chen C. Hiv nef protein causes endothelial dysfunction in porcine pulmonary arteries and human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. The Journal of surgical research. 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panigrahi S, Freeman ML, Funderburg NT, Mudd JC, Younes SA, Sieg SF, Zidar DA, Paiardini M, Villinger F, Calabrese LH, Ransohoff RM, Jain MK, Lederman MM. Siv/shiv infection triggers vascular inflammation, diminished expression of kruppel-like factor 2 and endothelial dysfunction. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;213:1419–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kay DG, Yue P, Hanna Z, Jothy S, Tremblay E, Jolicoeur P. Cardiac disease in transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef in cells of the immune system. The American journal of pathology. 2002;161:321–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta SK, Liu Z, Sims EC, Repass MJ, Haneline LS, Yoder MC. Endothelial colony-forming cell function is reduced during hiv infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2018:jiy550–jiy550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, Mildner-Rihm C, Adler K, Tiemann M, Rutten H, Fichtlscherer S, Martin H, Zeiher AM. Hmg-coa reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the pi 3-kinase/akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:391–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Zaromitidou M, Hatzis G, Mourouzis K, Chrysohoou C, Zisimos K, Mazaris S, Tourikis P, Athanasiou D, Stefanadis C, Papavassiliou AG, Tousoulis D. Atorvastatin treatment improves endothelial function through endothelial progenitor cells mobilization in ischemic heart failure patients. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Twigg HL 3rd, Knox KS, Zhou J, Crothers KA, Nelson DE, Toh E, Day RB, Lin H, Gao X, Dong Q, Mi D, Katz BP, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM. Effect of advanced hiv infection on the respiratory microbiome. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;194:226–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.