Abstract

The Panel on Plant Health performed a pest categorisation of Tecia solanivora (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) the Guatemalan potato tuber moth, for the EU. T. solanivora is a well‐defined species which feeds exclusively on Solanum tuberosum. It was first described from Costa Rica in 1973 and has spread through Central America and into northern South America via trade of seed potatoes. It has also spread to Mexico and the Canary Islands and most recently to mainland Spain where it is under official control in Galicia and Asturias. Potatoes in the field and storage can be attacked. Some authors regard T. solanivora as the most important insect pest of potatoes globally. T. solanivora is currently regulated by Council Directive 2000/29/EC, listed in Annex II/AI as Scrobipalpopsis solanivora. Larvae feed and develop within potato tubers; infested tubers therefore provide a pathway for pest introduction and spread, as does the soil accompanying potato tubers if it is infested with eggs or pupae. As evidenced by the ongoing outbreaks in Spain, the EU has suitable conditions for the development and potential establishment of T. solanivora. The pest could spread within the EU via movement of infested tubers; adults can fly and disperse locally. Larval feeding destroys tubers in the field and in storage. In the warmer southern EU, where the development would be fastest, yield losses would be expected in potatoes. Measures are available to inhibit entry via traded commodities (e.g. prohibition on the introduction of S. tuberosum). T. solanivora satisfies all of the criteria assessed by EFSA to satisfy the definition of a Union quarantine pest. It does not satisfy EU regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) status because it is under official control. There are uncertainties over the effectiveness of preventing illegal imports via passenger baggage and the magnitude of potential impacts in the cool EU climate.

Keywords: Guatemalan potato tuber moth, pest risk, passenger baggage, Scrobipalpopsis solanivora, Solanum tuberosum, quarantine

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

Council Directive 2000/29/EC1 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community establishes the present European Union plant health regime. The Directive lays down the phytosanitary provisions and the control checks to be carried out at the place of origin on plants and plant products destined for the Union or to be moved within the Union. In the Directive's 2000/29/EC annexes, the list of harmful organisms (pests) whose introduction into or spread within the Union is prohibited, is detailed together with specific requirements for import or internal movement.

Following the evaluation of the plant health regime, the new basic plant health law, Regulation (EU) 2016/20312 on protective measures against pests of plants, was adopted on 26 October 2016 and will apply from 14 December 2019 onwards, repealing Directive 2000/29/EC. In line with the principles of the above mentioned legislation and the follow‐up work of the secondary legislation for the listing of EU regulated pests, EFSA is requested to provide pest categorizations of the harmful organisms included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC, in the cases where recent pest risk assessment/pest categorisation is not available.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 22(5.b) and Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/20023, to provide scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to prepare and deliver a pest categorisation (step 1 analysis) for each of the regulated pests included in the appendices of the annex to this mandate. The methodology and template of pest categorisation have already been developed in past mandates for the organisms listed in Annex II Part A Section II of Directive 2000/29/EC. The same methodology and outcome is expected for this work as well.

The list of the harmful organisms included in the annex to this mandate comprises 133 harmful organisms or groups. A pest categorisation is expected for these 133 pests or groups and the delivery of the work would be stepwise at regular intervals through the year as detailed below. First priority covers the harmful organisms included in Appendix 1, comprising pests from Annex II Part A Section I and Annex II Part B of Directive 2000/29/EC. The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 1 is June 2018. The second priority is the pests included in Appendix 2, comprising the group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), the group of Tephritidae (non‐EU), the group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms, the group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. and the group of Margarodes (non‐EU species). The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 2 is end 2019. The pests included in Appendix 3 cover pests of Annex I part A Section I and all pests categorisations should be delivered by end 2020.

For the above mentioned groups, each covering a large number of pests, the pest categorisation will be performed for the group and not the individual harmful organisms listed under “such as” notation in the Annexes of the Directive 2000/29/EC. The criteria to be taken particularly under consideration for these cases, is the analysis of host pest combination, investigation of pathways, the damages occurring and the relevant impact.

Finally, as indicated in the text above, all references to ‘non‐European’ should be avoided and replaced by ‘non‐EU’ and refer to all territories with exception of the Union territories as defined in Article 1 point 3 of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031.

1.1.2.1. Terms of Reference: Appendix 1

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Aleurocantus spp. | Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) |

| Anthonomus bisignifer (Schenkling) | Oligonychus perditus Pritchard and Baker |

| Anthonomus signatus (Say) | Pissodes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Aschistonyx eppoi Inouye | Scirtothrips aurantii Faure |

| Carposina niponensis Walsingham | Scirtothrips citri (Moultex) |

| Enarmonia packardi (Zeller) | Scolytidae spp. (non‐EU) |

| Enarmonia prunivora Walsh | Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny |

| Grapholita inopinata Heinrich | Tachypterellus quadrigibbus Say |

| Hishomonus phycitis | Toxoptera citricida Kirk. |

| Leucaspis japonica Ckll. | Unaspis citri Comstock |

| Listronotus bonariensis (Kuschel) | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Citrus variegated chlorosis | Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae (Ishiyama) Dye and pv. oryzicola (Fang. et al.) Dye |

| Erwinia stewartii (Smith) Dye | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler (non‐EU pathogenic isolates) | Elsinoe spp. Bitanc. and Jenk. Mendes |

| Anisogramma anomala (Peck) E. Müller | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Kilian and Maire) Gordon |

| Apiosporina morbosa (Schwein.) v. Arx | Guignardia piricola (Nosa) Yamamoto |

| Ceratocystis virescens (Davidson) Moreau | Puccinia pittieriana Hennings |

| Cercoseptoria pini‐densiflorae (Hori and Nambu) Deighton | Stegophora ulmea (Schweinitz: Fries) Sydow & Sydow |

| Cercospora angolensis Carv. and Mendes | Venturia nashicola Tanaka and Yamamoto |

| (d) Virus and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet curly top virus (non‐EU isolates) | Little cherry pathogen (non‐ EU isolates) |

| Black raspberry latent virus | Naturally spreading psorosis |

| Blight and blight‐like | Palm lethal yellowing mycoplasm |

| Cadang‐Cadang viroid | Satsuma dwarf virus |

| Citrus tristeza virus (non‐EU isolates) | Tatter leaf virus |

| Leprosis | Witches’ broom (MLO) |

| Annex IIB | |

| (a) Insect mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Anthonomus grandis (Boh.) | Ips cembrae Heer |

| Cephalcia lariciphila (Klug) | Ips duplicatus Sahlberg |

| Dendroctonus micans Kugelan | Ips sexdentatus Börner |

| Gilphinia hercyniae (Hartig) | Ips typographus Heer |

| Gonipterus scutellatus Gyll. | Sternochetus mangiferae Fabricius |

| Ips amitinus Eichhof | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens (Hedges) Collins and Jones | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Glomerella gossypii Edgerton | Hypoxylon mammatum (Wahl.) J. Miller |

| Gremmeniella abietina (Lag.) Morelet | |

1.1.2.2. Terms of Reference: Appendix 2

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested per group. The list below follows the categorisation included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), such as: | |

| 1) Carneocephala fulgida Nottingham | 3) Graphocephala atropunctata (Signoret) |

| 2) Draeculacephala minerva Ball | |

| Group of Tephritidae (non‐EU) such as: | |

| 1) Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) | 12) Pardalaspis cyanescens Bezzi |

| 2) Anastrepha ludens (Loew) | 13) Pardalaspis quinaria Bezzi |

| 3) Anastrepha obliqua Macquart | 14) Pterandrus rosa (Karsch) |

| 4) Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) | 15) Rhacochlaena japonica Ito |

| 5) Dacus ciliatus Loew | 16) Rhagoletis completa Cresson |

| 6) Dacus curcurbitae Coquillet | 17) Rhagoletis fausta (Osten‐Sacken) |

| 7) Dacus dorsalis Hendel | 18) Rhagoletis indifferens Curran |

| 8) Dacus tryoni (Froggatt) | 19) Rhagoletis mendax Curran |

| 9) Dacus tsuneonis Miyake | 20) Rhagoletis pomonella Walsh |

| 10) Dacus zonatus Saund. | 21) Rhagoletis suavis (Loew) |

| 11) Epochra canadensis (Loew) | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms such as: | |

| 1) Andean potato latent virus | 4) Potato black ringspot virus |

| 2) Andean potato mottle virus | 5) Potato virus T |

| 3) Arracacha virus B, oca strain | 6) non‐EU isolates of potato viruses A, M, S, V, X and Y (including Yo, Yn and Yc) and Potato leafroll virus |

| Group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L.,Rubus L. and Vitis L., such as: | |

| 1) Blueberry leaf mottle virus | 8) Peach yellows mycoplasm |

| 2) Cherry rasp leaf virus (American) | 9) Plum line pattern virus (American) |

| 3) Peach mosaic virus (American) | 10) Raspberry leaf curl virus (American) |

| 4) Peach phony rickettsia | 11) Strawberry witches’ broom mycoplasma |

| 5) Peach rosette mosaic virus | 12) Non‐EU viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. |

| 6) Peach rosette mycoplasm | |

| 7) Peach X‐disease mycoplasm | |

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Margarodes (non‐EU species) such as: | |

| 1) Margarodes vitis (Phillipi) | 3) Margarodes prieskaensis Jakubski |

| 2) Margarodes vredendalensis de Klerk | |

1.1.2.3. Terms of Reference: Appendix 3

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Acleris spp. (non‐EU) | Longidorus diadecturus Eveleigh and Allen |

| Amauromyza maculosa (Malloch) | Monochamus spp. (non‐EU) |

| Anomala orientalis Waterhouse | Myndus crudus Van Duzee |

| Arrhenodes minutus Drury | Nacobbus aberrans (Thorne) Thorne and Allen |

| Choristoneura spp. (non‐EU) | Naupactus leucoloma Boheman |

| Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) | Premnotrypes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetverikov | Pseudopityophthorus minutissimus (Zimmermann) |

| Diabrotica barberi Smith and Lawrence | Pseudopityophthorus pruinosus (Eichhoff) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber | Scaphoideus luteolus (Van Duzee) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Mannerheim | Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) |

| Diabrotica virgifera zeae Krysan & Smith | Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) |

| Diaphorina citri Kuway | Spodoptera litura (Fabricus) |

| Heliothis zea (Boddie) | Thrips palmi Karny |

| Hirschmanniella spp., other than Hirschmanniella gracilis (de Man) Luc and Goodey | Xiphinema americanum Cobb sensu lato (non‐EU populations) |

| Liriomyza sativae Blanchard | Xiphinema californicum Lamberti and Bleve‐Zacheo |

| (b) Fungi | |

| Ceratocystis fagacearum (Bretz) Hunt | Mycosphaerella larici‐leptolepis Ito et al. |

| Chrysomyxa arctostaphyli Dietel | Mycosphaerella populorum G. E. Thompson |

| Cronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phoma andina Turkensteen |

| Endocronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phyllosticta solitaria Ell. and Ev. |

| Guignardia laricina (Saw.) Yamamoto and Ito | Septoria lycopersici Speg. var. malagutii Ciccarone and Boerema |

| Gymnosporangium spp. (non‐EU) | Thecaphora solani Barrus |

| Inonotus weirii (Murril) Kotlaba and Pouzar | Trechispora brinkmannii (Bresad.) Rogers |

| Melampsora farlowii (Arthur) Davis | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Tobacco ringspot virus | Pepper mild tigré virus |

| Tomato ringspot virus | Squash leaf curl virus |

| Bean golden mosaic virus | Euphorbia mosaic virus |

| Cowpea mild mottle virus | Florida tomato virus |

| Lettuce infectious yellows virus | |

| (d) Parasitic plants | |

| Arceuthobium spp. (non‐EU) | |

| Annex IAII | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Meloidogyne fallax Karssen | Rhizoecus hibisci Kawai and Takagi |

| Popillia japonica Newman | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Clavibacter michiganensis (Smith) Davis et al. ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al. | Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith) Yabuuchi et al. |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Melampsora medusae Thümen | Synchytrium endobioticum (Schilbersky) Percival |

| Annex I B | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say | Liriomyza bryoniae (Kaltenbach) |

| (b) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet necrotic yellow vein virus | |

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

The subject of this pest categorisation is listed in Appendix 1 of the Terms of Reference (ToR) as Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolný. This is widely considered a junior synonym of Tecia solanivora Povolný, 1973. It is one of a number of pests listed in the Appendices to the ToR to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of a quarantine pest or those of a regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) for the area of the European Union (EU) excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States (MSs) referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Literature search

A literature search was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name (junior and senior synonyms) of the pest as search term. Relevant papers were reviewed, and further references and information were obtained from experts, from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.2. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the EPPO Global Database (EPPO, 2017).

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT.

The Europhyt database was consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network launched by the Directorate General for Health and Consumers (DG SANCO) and is a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. The Europhyt database manages notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the MSs and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread.

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for T. solanivora, following guiding principles and steps presented in the EFSA guidance on the harmonised framework for pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2010) and as defined in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures No 11 (FAO, 2013) and No 21 (FAO, 2004).

In accordance with the guidance on a harmonised framework for pest risk assessment in the EU (EFSA PLH Panel, 2010), this work was initiated following an evaluation of the EU's plant health regime. Therefore, to facilitate the decision‐making process, in the conclusions of the pest categorisation, the Panel addresses explicitly each criterion for a Union quarantine pest and for a Union RNQP in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants and includes additional information required as per the specific ToR received by the European Commission. In addition, for each conclusion, the Panel provides a short description of its associated uncertainty.

Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. All relevant criteria have to be met for the pest to potentially qualify either as a quarantine pest or as a RNQP. If one of the criteria is not met, the pest will not qualify. A pest that does not qualify as a quarantine pest may still qualify as a RNQP which needs to be addressed in the opinion. For the pests regulated in the protected zones only, the scope of the categorisation is the territory of the protected zone; thus, the criteria refer to the protected zone instead of the EU territory.

Table 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding protected zone quarantine pest (articles 32–35) | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU? Describe the pest distribution briefly! |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a protected zone quarantine organism. | Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a regulated non‐quarantine pest. (A regulated non‐quarantine pest must be present in the risk assessment area). |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3 ) | If the pest is present in the EU but not widely distributed in the risk assessment area, it should be under official control or expected to be under official control in the near future. |

The protected zone system aligns with the pest‐free area system under the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). The pest satisfies the IPPC definition of a quarantine pest that is not present in the risk assessment area (i.e. protected zone). |

Is the pest regulated as a quarantine pest? If currently regulated as a quarantine pest, are there grounds to consider its status could be revoked? |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in and spread within the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways! |

Is the pest able to enter into, become established in and spread within the protected zone areas? Is entry by natural spread from EU areas where the pest is present possible? |

Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects? Clearly state if plants for planting is the main pathway! |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the protected zone areas? | Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the protected zone areas such that the risk becomes mitigated? Is it possible to eradicate the pest in a restricted area within 24 months (or a period longer than 24 months where the biology of the organism so justifies) after the presence of the pest was confirmed in the protected zone? |

Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as potential protected zone quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. |

It should be noted that the Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, the Panel will present a summary of the observed pest impacts. Economic impacts are expressed in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, while addressing social impacts is outside the remit of the Panel, in agreement with EFSA guidance on a harmonised framework for pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2010).

The Panel will not indicate in its conclusions of the pest categorisation whether to continue the risk assessment process, but, following the agreed two‐step approach, will continue only if requested by the risk managers. However, during the categorisation process, experts may identify key elements and knowledge gaps that could contribute significant uncertainty to a future assessment of risk. It would be useful to identify and highlight such gaps so that potential future requests can specifically target the major elements of uncertainty, perhaps suggesting specific scenarios to examine.

3. Pest categorisation

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? (Yes or No)

Yes, the identity of the pest is established. Tecia solanivora Povolný, 1973 is an insect in the Order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) in the family Gelechiidae (twirler moths).

This organism was first described by Povolný in 1973 who placed it in the genus Scrobipalpopsis. Povolný (1973) described it as a new species following its discovery causing damage to potatoes in Costa Rica although it was thought to have been introduced into Costa Rica via seed potatoes from Guatemala in 1970. In a taxonomic study of the male and female genitalia, Hodges and Becker (1990) concluded that Scrobipalpopsis is a junior synonym of Tecia Kieffer & Jörgensen, 1910, hence revising the binomial name and placing the original authority in brackets, i.e. T. solanivora (Povolný). However, the synonymisation was opposed by Povolný (1993) who resurrected the original name S. solanivora. The 1993 paper was little known, and subsequent authors continued to use the name T. solanivora (Povolný). Povolný published two more papers in 2004 (Povolný, 2004; Povolný and Hula, 2004) using the name S. solanivora; but later, authors still continue to use T. solanivora.

A search of Web of Science revealed 50 papers using the name T. solanivora between 1995 and 2017 and one paper using the name S. solanivora, that single paper being Povolný and Hula (2004). The search on Web of Science did not find Povolný (2004).

For the purposes of this pest categorisation, the name most commonly used in the scientific literature, T. solanivora (Povolný), will be used. The EPPO diagnostic protocol (EPPO, 2006a) uses the name T. solanivora.

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

In Central America, there are multiple generations of T. solanivora per year. At 10°C, there are two generations per year while at 25°C there can be 10 generations per year (Notz, 1996). Eggs are laid individually or in small clusters on the soil surface near tubers or close to the base of potato plants (Torres, 1989). Rarely eggs are laid on the stems or foliage of potatoes (Povolný, 1973; Barreto, 2005). When females infest potato storage facilities, they oviposit directly onto exposed potato tubers (EPPO, 2006b). Povolný (1973) reported some females laid up to approximately 300 eggs over an 8‐day period, although the mean fecundity was just under 200 eggs per female.

Eggs develop in 5–25 days, depending on the temperature (Notz, 1996). With mean minimum temperatures of 18.8°C and mean maximum temperatures of 22.1°C, eggs hatch in 6–7 days.

First instar larvae burrow into the soil searching for potato tubers; in potato storage facilities, larvae look for exposed tubers. Larvae feed on tubers; an individual larva will mine into a single tuber and create several galleries. Larvae can burrow and create galleries just underneath the surface of the tuber or burrow into the interior of the tuber. Larval feeding cause's tuber weight loss and allows access of secondary pathogens.

There are four larval instars and development usually occurs inside a single tuber (Hilje, 1994). The larval stage can last from approximately 18–80 days depending on the temperature (Notz, 1996). Mature larvae emerge from tubers to pupate.

Outdoors, larvae pupate in the soil, near the surface. In potato storage facilities, pupae are formed in sheltered areas such as in cracks or corners of building structures and also in potato sacks. It is rare for pupae to form inside a tuber itself (Povolný, 1973).

Under laboratory conditions (15.5°C, relative humidity (RH) 65.6%), the life cycle lasts 95 days for females and 91 days for males. The mean duration of developmental stages is, 15 days, 29 days, 5 days and 26 days for eggs, larvae, prepupae and pupae, respectively. Adult males live for 16 days, while adult females live for about 20 days.

At 20°C, the life cycle lasts 57 days for females and 54 days for males.

At 25°C, the life cycle lasts 42 days for females and 41 days for males (Torres et al., 1997).

3.1.3. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, as with other Lepidoptera, light traps can be used to capture adults which can then be identified using conventional morphological keys. White delta plastic traps baited with a synthetic sex pheromone can also be used to detect adult males (Nesbitt et al., 1985; Bosa et al., 2005; Cruz Roblero et al., 2011).

Tubers infested at low level can be difficult to detect. However, when larvae exit the tuber they leave circular exit holes 2–3 mm in diameter, which can be detected. Heavily infested tubers are more easily detected. If infested potato tubers are detected, larvae can be identified using morphological keys.

An EPPO diagnostic protocol exists for the identification of this organism (EPPO, 2006a). Egg and pupal stages are not reliable for identification.

Eggs are 0.46–0.63 mm long and 0.39–0.43 mm wide (Povolný, 1973; EPPO, 2006a); pearly white when first oviposited, eggs turn mat white to yellow as they mature (Carrillo and Torrado‐Leon, 2014).

First instar larvae are approximately 1.5 mm long and translucent; larvae become bluish‐green as they mature; final instar larvae are approximately 16 mm (Torres, 1998).

Pupae are 7.3 mm–9.0 mm long, coffee‐coloured light brown becoming dark brown as they develop (EPPO, 2006b). Female pupae tend to be larger and heavier than male pupae (Carrillo and Torrado‐Leon, 2014).

Adults are brown, females bright brown and males dark brown; females are 13.0 mm by 3.4 mm; males are smaller, 9.7 mm by 2.9 mm. The rear wings of both sexes have many fringes (EPPO, 2006a; CABI, 2012).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

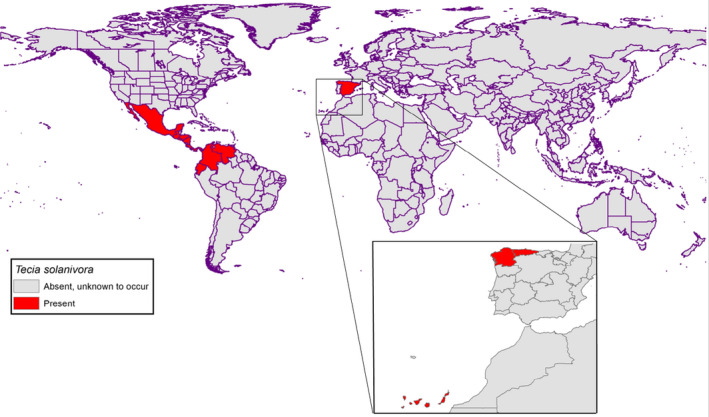

Tecia solanivora is most likely to originate from Guatemala where its genetic diversity is greatest (Torres‐Leguizamón et al., 2011). It has spread through Central America and into the north of South America and into the south of North America via movement of potato tubers. Most recently, it arrived into mainland Europe (Spain) (Table 2) (Puillandre et al., 2008). Dispersal locally occurs via adult flight. Figure 1 and Table 2 show the global distribution of T. solanivora.

Table 2.

Global distribution of Tecia solanivora

| Region | Country (year when first found) | Sub‐national distribution (e.g. States/Provinces) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Mexico (2010) | Cruz Roblero et al. (2011) | |

| Central America & Caribbean | Costa Rica (1973) | Povolný (1973) | |

| El Salvador (1973) | Povolný (1973) | ||

| Guatemala (1956)a | Torres‐Leguizamón et al. (2011) | ||

| Honduras (1973) | Povolný (1973) | ||

| Nicaragua (1989) | EPPO (2006b) | ||

| Panama (1973) | Povolný (1973) | ||

| South America | Colombia (1985) | ||

| Ecuador (1996) | |||

| Venezuela (1983) | |||

| Europe | Spain (mainland Spain 2015) |

Galicia (September, 2015) Asturias (November, 2016) limited distribution, under official control (see also Africa: Canary Islands) |

EPPO (2006b) |

| Africa | Canary Islands (1999) | Tenerife, La Gomera, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote (1999) | EPPO (2006b) |

| Asia | Absent, not known to occur | ||

| Oceania | Absent, not known to occur |

Damage to potatoes by an unidentified small brown moth was reported from Guatemala in 1956 (Torres‐Leguizamón et al., 2011). Although unidentified at the time, the damage was likely to be caused by what is now known as T. solanivora.

Figure 1.

Global distribution of Tecia solanivora

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU?

Yes, T. solanivora is present in Spain, in the Canary Isles since 1999 and in the mainland since 2015, where it is under official control (Anon, 2017a,b,c).

When T. solanivora was found in the north of Tenerife, it was found in the field and in potato storage facilities; in the islands of La Gomera, Gran Canaria and Lanzarote it was found only in potato storage facilities. Although first observed in Tenerife in June 1999, the specimens were identified as T. solanivora in March 2000 (EPPO, 2006b).

In mainland Spain, T. solanivora was first found in June 2015 in potato fields in Galicia on specific pheromone monitoring traps. The identity was confirmed in August 2015 and the European Commission was notified in September 2015 (Europhyt notification, 2015). In November 2016, T. solanivora was also detected in neighbouring Asturias in open fields and potato storage warehouses (Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Food and the Environment, 2016).

T. solanivora is not known to occur in any other EU MS. The absence in the Netherlands is confirmed by survey dated June 2017 (EPPO Global Database, 2017).

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Council Directive 2000/29/EC

Tecia (=Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora is listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Details are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Tecia (= Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora in Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex II | ||

| Part A | Harmful organisms whose introduction into, and spread within, all Member States shall be banned if they are present on certain plants or plant products | |

| Section I | Harmful organisms not known to occur in the Community andrelevant for the entire Community | |

| (a) | Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Species | Subject of contamination | |

| 28.1 | Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny | Tubers of Solanum tuberosum L. |

3.3.2. Legislation addressing the hosts of Tecia (=Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora

Table 4.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve Tecia (= Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora in Annexes III, IV and V of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex III | ||

| Part A | Plants, plant products and other objects the introduction of which shall be prohibited in all Member States | |

| Description | Country of origin | |

| 10. | Tubers of Solanum tuberosum L., seed potatoes | Third countries other than Switzerland |

| 12. |

Tubers of species of Solanum L., and their hybrids, other than those specified in points 10 and 11 |

Without prejudice to the special requirements applicable to the potato tubers listed in Annex IV, Part A Section I, third countries other than Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Switzerland, Tunisia and Turkey, and other than European third countries which are either recognised as being free from Clavibacter michiganensis ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al., in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article 18(2), or in which provisions recognised as equivalent to the Community provisions on combating Clavibacter michiganensis ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al., in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article 18(2), have been complied with |

| Annex IV | ||

| Part A | Special requirements which shall be laid down by all member states for the introduction and movement of plants, plant products and other objects into and within certain protected zones | |

| Section I | Plants, plant products and other objects originating outside the Community | |

| Plants, plant products and other objects | Special requirements | |

| 25.4.2. | Tubers of Solanum tuberosum L. |

Without prejudice to the provisions applicable to tubers listed in Annex III(A)(10), (11) and (12) and Annex IV(A)(I)(25.1), (25.2), (25.3), (25.4) and (25.4.1), official statement that: (a) the tubers originate in a country where Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny is not known to occur; or (b) the tubers originate in an area free from Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny, established by the national plant protection organisation in accordance with relevant International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures. |

| Section II | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in the Community | |

| Plants, plant products and other objects | Special requirements | |

| 18.2 |

Tubers of Solanum tuberosum L., intended for planting, other than tubers of those varieties officially accepted in one or more Member States pursuant to Council Directive 70/457/EEC of 29 September 1970 on the common catalogue of varieties of agricultural plant species (1) |

Without prejudice to the special requirements applicable to the tubers listed in Annex IV(A) (II)(18.1), official statement that the tubers:

|

| Annex V | Plants, plant products and other objects which must be subject to a plant health inspection (at the place of production if originating in the Community, before being moved within the Community — in the country of origin or the consignor country, if originating outside the Community) before being permitted to enter the Community | |

| Part A | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in the Community | |

| 1. | Plants, plant products and other objects which are potential carriers of harmful organisms of relevance for the entire Community and which must be accompanied by a plant passport | |

| 1.3 | Plants of stolon‐ or tuber‐forming species of Solanum L. or their hybrids, intended for planting. | |

| Section II | Plants, plant products and other objects produced by producers whose production and sale is authorised to persons professionally engaged in plant production, other than those plants, plant products and other objects which are prepared and ready for sale to the final consumer, and for which it is ensured by the responsible official bodies of the Member States, that the production thereof is clearly separate from that of other products | |

| Part B | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in territories, other than those territories referred to in Part A | |

| 1. | Plants, plant products and other objects which are potential carriers of harmful organisms of relevance for the entire Community | |

| 4. | Tubers of Solanum tuberosum L. | |

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Host range

Tecia solanivora feeds exclusively on S. tuberosum (EPPO, 2006b; CABI, 2012; Kroschel and Schaub, 2013). T. solanivora is regulated on S. tuberosum by 2000/29 EC (Table 4).

3.4.2. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory? (Yes or No) If yes, identify and list the pathways!

Yes, the organism has already arrived in Spain hence a pathway exists. Tubers of potatoes provide the major pathway for entry.

The movement of prohibited potato tubers by people travelling between the Canary Isles and mainland Spain is thought to be the pathway for introducing Tecia and into Galicia.

Vigo and A Coruña are important Galician harbours and locals may have introduced potatoes for their kitchen garden.

Potential pathways include infested:

seed potatoes,

ware potatoes,

reused potato bags (which may contain eggs and pupae),

soil (which may carry eggs or pupae) accompanying potato tubers (EPPO, 2006b).

T. solanivora was introduced into Costa Rica, Venezuela and Colombia via seed potatoes (Povolný, 1973; Kroschel and Schaub, 2013). Entry into Tenerife (Canary Islands) has been attributed to the illegal import of infested potatoes from Venezuela, Ecuador or Colombia (EPPO, 2006b).

EUROSTAT records volumes of imported commodities entering the EU; potatoes (S. tuberosum) are recorded using a variety of Combined Nomenclature (CN) codes, according to intended use. Codes are accompanied with brief text to provide a description, e.g.

CN 0701 1000 (seed potatoes)

CN 0701 9010 (potatoes for the manufacture of starch)

CN 0701 9050 (potatoes, new (Jan 1–June 30))

CN 0701 9090 (potatoes, other i.e. excluding seed, new potatoes and potatoes for the manufacture of starch).

Seed potatoes: While seed potatoes are prohibited from outside the EU (excluding Switzerland), EUROSTAT data indicate imports of seed potatoes in the past from countries where T. solanivora occurs (see below). However, such imports are assumed to correspond to rejected or unsold consignments, originally exported from the EU. Apparently, this process is quite common in the potato sector.

6,900 kg from Guatemala into Belgium/Luxembourg in 1989,

21,000 kg from Costa Rica into France in 1997,

24,500 kg from Colombia into France in 1998,

20,700 kg from El Salvador into France in 1998,

250,000 kg from Honduras into NL in 2004.

EUROSTAT data does not indicate any imports of seed potatoes from Central or South America over the past 5 years (pathway is prohibited by 2000/29 EC – see Table 4).

The Netherlands NPPO kindly provided detailed trade inspection data regarding plants for planting from 2012 to 2014. It indicated that S. tuberosum was imported from Costa Rica in 2014, recorded as CN 0602 9099 (Other live plants, rooted, other). It is possible that this is also a rejected consignment originally from the EU.

Potatoes for starch: Over the 5‐year period 2012–2016, no imports of potatoes for the manufacture of starch are recorded in EUROSTAT from countries in Central or South America where T. solanivora occurs.

New (ware) potatoes: Over the 5‐year period 2012–2016, no imports of fresh or chilled new potatoes are recorded in EUROSTAT from countries in Central or South America where T. solanivora occurs.

Potatoes (other): Over the 5‐year period 2012–2016 EUROSTAT records 300 kg of fresh or chilled potatoes (excluding new potatoes and potatoes for the manufacture of starch) from Mexico (a country where T. solanivora occurs) to Spain in 2012 (Also assumed to be rejected consignments originally from EU).

There are no records of interception of T. solanivora in the Europhyt database.

3.4.3. Establishment

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory? (Yes or No)

Yes, since 2015 T. solanivora has been present in two regions of north western Spain (Galicia and Asturias) where it is under official control. Other areas of the EU would also provide suitable environmental conditions for the organism to establish.

3.4.3.1. EU distribution of main host plants

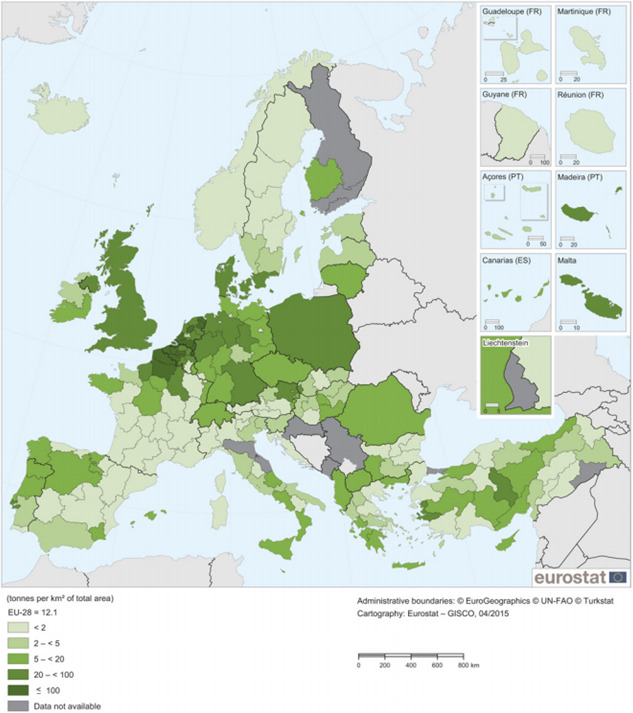

Potato (S. tuberosum) is the only host for T. solanivora (EPPO, 2006b; CABI, 2012; Kroschel and Schaub, 2013). Potatoes are widely grown throughout the EU, both commercially and in private gardens and allotments. Between 2012 and 2016, the mean area of potatoes commercially cultivated in the EU was 17,085,000 ha. Poland, Germany, Romania and France grew over 50% of the total EU potato area (Appendix A). The production of European potato is shown spatially in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

- Source: Eurostat regional yearbook 2015, Available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/7018888/KS-HA-15-001-EN-N.pdf/6f0d4095-5e7a-4aab-af28-d255e2bcb395, (accessed 13 October 2017)

3.4.3.2. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

Tecia solanivora has adapted to a variety of environmental conditions, e.g. being found in mountainous regions of Central and South America at altitudes between 1,000 m and 3,500 m (Torres et al., 1997); in the Canaries at altitudes up to 600 m (EPPO, 2006b); and on mainland Spain at altitudes below 400 m. Daily temperature ranges vary markedly between these areas. At 10°C, there are two generations per year while at 25°C there can be 10 generations per year (Notz, 1996). Optimum temperature for population development appears to be around 25°C (Torres et al., 1997). T. solanivora does not survive below 7.9°C or above 30°C (Notz, 1996).

Parts of the EU potato‐growing region have suitable temperatures that would allow multiple generations to develop each year. Cold winters, where minimum temperatures are often below 7.9°C will prevent T. solanivora from establishing outdoors in northern Europe.

Germain (2002a) conducted a pest risk analysis on T. solanivora and used the computer program CLIMEX to assess potential establishment in Europe. Taking into account the climatic conditions within a pest's existing distribution, CLIMEX is used to generate an ‘eco‐climatic index’ (EI) representing the climatic suitability of a location outside of a pests’ current distribution, thereby identifying locations where establishment is potentially possible (Sutherst and Maywald, 1985; Skarratt et al., 1995). Maps showing EI for European locations in the pest risk analysis indicate that many sites in Europe have suitable climatic conditions for the establishment of T. solanivora (Germain, 2002b). However, host distribution must also be considered when interpreting CLIMEX maps as CLIMEX does not take account of biotic factors when generating EIs.

Kroschel et al. (2016) provide a pest distribution and risk atlas for a range of invasive agricultural pests threatening Africa. One chapter examines T. solanivora and includes a global map entitled ‘Establishment Risk Index’ (ERI) (Schaub et al., 2016). How the ERI is calculated is not indicated. Nevertheless, the global map suggests that southern Europe, and in particular coastal regions around the Mediterranean and the Atlantic coast of Portugal share an ERI with parts of Central and South America where T. solanivora occurs, hence suggesting that parts of the EU provide suitable conditions for the establishment of T. solanivora.

3.4.4. Spread

Is the pest able to spread within the EU territory following establishment? (Yes or No) How?

Yes, movement of infested potato tubers could spread the pest within the EU; local spread could occur as adults fly.

RNQPs: Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects?

Yes, Long distance spread is via plants for planting (seed potatoes).

The spread of T. solanivora in Central and South America has been due to the movement of infested seed potatoes (Puillandre et al., 2008). The introduction into the Canary Islands has been attributed to the illegal movement of seed potatoes from South America (EPPO, 2006b).

Although adults are weak fliers, flying moths can contribute to local spread. Adults fly at night. They make short flights close to the ground, and during the day, they shelter in shady places on the ground, on bushes and weeds at the edges of fields and under leaf litter or between potatoes in potato storage facilities. Adults can move from potato fields into potato storage facilities and from there back to potato fields (Povolný, 2004).

When introduced into new areas in Central and South America, T. solanivora spreads rapidly in potato‐growing regions; spread was facilitated by the trade in potato tubers as well as local natural dispersal (Kroschel and Schaub, 2013).

Plants for planting (seed potatoes) are a means of spread.

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes, T. solanivora is regarded as a serious pest of potato crops and of potato stocks in all countries where it is present, including Spain.

RNQPs: Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? 4

Yes, all infested tubers, including seed potatoes, are destroyed by larval infestation.

As described in Section 3.1.2 (Biology), larvae attack tubers; tuber quality is lowered and heavily infested tubers can no longer be used for human or animal consumption or can be completely destroyed (Kutinkova et al., 2016). Although unidentified at the time, T. solanivora was a pest of potatoes in Guatemala in the 1950s (Murillo (1980), cited by Torres‐Leguizamón et al. (2011) Villaneuva and Saldamando, 2013). In 1972, just before being identified, T. solanivora caused losses of 20–40% in potato crops in Costa Rica (Povolný, 1973). While larvae primarily feed on and destroy potato tubers, when there are high populations, larvae can occasionally also attack the green parts of the plant (Povolný, 1973).

In 1994, Colombia attributed losses of 276,323 tonnes to T. solanivora; during 1995, there was 4.4% damage to field potatoes and 11.3% damage to potatoes in storage (Arias et al., 1996).

After its introduction to the Canary Islands, severe outbreaks were reported by local news media, and in 2001, media attributed a 50% yield reduction to T. solanivora combined with a severe drought (EPPO, 2006b). Kutinkova et al. (2016) regard T. solanivora as the most important insect pest of potato worldwide.

As well as attacking potatoes in the field, the pest can also seriously impact tubers in storage. In Central and South America, potatoes may be held for short‐term storage at ambient temperatures in the dark, in well‐ventilated buildings (CABI, 2017). If infested tubers are introduced into such conditions, larval development can continue and multiple generations could occur. Potato stocks in such conditions can be completely destroyed in less than three months (EPPO, 2006b).

In Europe, ware potatoes are often held in storage for prolonged periods at about 4°C (CABI, 2017). In such conditions, larvae would not survive. However, tubers for processing are generally stored at 7–10°C which could allow larvae to develop and complete development (slowly).

If T. solanivora were to establish in the EU, direct impacts from larval feeding and subsequent secondary pathogen infections could be expected in the field and in potato storage facilities.

3.6. Availability and limits of mitigation measures

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, the movement of host plant material that can carry the pest, i.e. tubers of S. tuberosum, is regulated.

RNQPs: Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, tubers can be sourced from pest free areas.

3.6.1. Biological or technical factors limiting the feasibility and effectiveness of measures to prevent the entry, establishment and spread of the pest

Infested tubers are difficult to detect (entry holes are very small).

Eggs and larvae can be carried with soil accompanying tubers.

Larvae develop inside tubers where they are protected from contact insecticides and natural enemies.

Strong cultural links between South America and Spain give rise to large numbers of people moving between the regions and provide an opportunity for passengers to carry small quantities of potatoes with them in their luggage. Although such activities are prohibited, managing such pathways is very difficult.

3.6.2. Biological or technical factors limiting the ability to prevent the presence of the pest on plants for planting

Difficulties in detecting low‐level infestations.

3.6.3. Control methods

Potatoes in the field can be protected by following good crop management practices such as:

Use of healthy (uninfested) seed potato tubers

Deep tuber planting high earthing up of soil around developing potato plants

Crop rotation

Harvesting all tubers (no tubers left to become volunteers)

High‐density pheromone trapping (16 traps/ha)

Chemical insecticides targeting adults (e.g. ‘attract and kill’ traps)

Good irrigation.

In storage systems:

Ensure all potatoes are covered

Use diffuse lighting

Use pheromone dispensers to disrupt mating in storage

Use pheromone traps as a direct control method

Store tubers at or below 8°C

(CABI, 2012 and references therein).

In Spain, a 5‐year plan that aims to inhibit spread and eradicate T. solanivora, from the fields and storage facilities, includes:

Surveillance and monitoring,

Delimiting‐affected areas and buffer zones,

Destruction of contaminated tubers,

Prohibition of planting of potatoes and restriction of movements in affected areas,

Controls in places where potatoes are sold in areas identified as risk areas.

3.7. Uncertainty

There are a number of uncertainties, such as whether there were imports of potatoes from Central and South America in the past, or such trade continues but is not recorded in EUROSTAT using CN codes 0701 (codes that refer specifically to potatoes). However, once T. solanivora spread internationally via the movement of potato tubers, it could (re‐)enter the EU on infested tubers originated from Central and South America that is not prohibited by existing legislation.

There is uncertainty as to the number of generations that could develop each year in the EU that affect the magnitude of potential impacts. However, the fact that T. solanivora can complete its development and impact on potato production is evidenced by the ongoing outbreaks that are under official control in north‐west Spain.

Long‐term establishment in potato‐growing countries where winter frosts regularly occur would only be possible if storage facilities provide refuges in winter time, and if movements from there to the field is possible.

These uncertainties do not affect the categorisation conclusions.

4. Conclusions

Tecia (=Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora meets the criteria assessed by EFSA for consideration as a Union quarantine pest (Table 5).

Table 5.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1) | The identity of the pest is established. Tecia (=Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora Povolný (1973); is an insect in the Order Lepidoptera, in the family Gelechiidae. | The identity of the pest is established. Tecia (=Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora Povolný (1973) is an insect in the Order Lepidoptera in the family Gelechiidae. | None |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2) | Yes, T. solanivora is present in the EU territory, but it is not widely distributed. It occurs in Galicia and Asturias in the northwest of Spain where it is under official control. | Yes, T. solanivora is present in the EU territory, but it is not widely distributed. It occurs in Galicia and Asturias in the northwest of Spain, where it is under official control. | None |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3) | T. solanivora is regulated on Solanum tuberosum by 2000/29 EC; In Spain, it is under official control and eradication measures are in place. | T. solanivora is regulated on Solanum tuberosum by 2000/29 EC; In Spain, it is under official control and eradication measures are in place. Because it remains under official control, it does not meet this requirement for RNQP status. | None |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) | T. solanivora has entered the EU; hence, pathways exist, potential pathways include infested potato tubers (mainly seed), reused containers carrying infested tubers and soil attached to tubers. Environmental conditions, especially in southern Europe, appear suitable for establishment. Spread would occur through movement of infested potato tubers; local spread could occur by flying adults. | International and long distance spread occurs via plants for planting (seed potatoes). | Whether there are any potatoes moved (illegally?) into the EU from areas where T. solanivora occurs. |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | Establishment of T. solanivora in the EU would have an impact on production of potatoes. | Larvae of T. solanivora can destroy potato tubers; hence, their presence in seed potatoes would have an impact on the intended use of such plants for planting | The amount of damage to be expected in field potatoes and in harvested stocks is uncertain due to cooler conditions in the EU. |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | Phytosanitary measures are available to inhibit the likelihood of entry into and spread within the EU e.g. prohibition of S. tuberosum tubers from many third countries; sourcing seed potatoes from pest‐free areas; prohibiting soil from being carried with seed potatoes. | Phytosanitary measures are available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such as growing seed potatoes only in pest‐free areas; |

Uncertainty over the effectiveness of preventing illegal import (e.g. passenger baggages). Uncertainty on the effectiveness of the measures to eradicate the pest once it is introduced. |

| Conclusion on pest categorisation (Section 4) | Tecia solanivora satisfies all of the criteria assessed by EFSA to qualify as a Union quarantine pest. Although T. solanivora is present in the EU territory, it has a restricted distribution and is under official control. | Not all criteria assessed by EFSA for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest are met. Although T. solanivora is present in the EU territory, it has a restricted distribution and is under official control. | None. |

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate |

|

||

Abbreviations

- CN

Combined Nomenclature

- DG

SANCO Directorate General for Health and Consumers

- EI

eco‐climatic index

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- ERI

Establishment Risk Index

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- RH

relative humidity

- RNQP

Regulated Non‐Quarantine Pest

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

Appendix A – Area of cultivated potatoes (ware and seed) in the EU 2012–2016

Source: Eurostat STRUCPRO 1000 ha, accessed 29 September 2017.

| EU MS\Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 5‐year mean | 5‐year mean as % of EU sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union (28) | 1,797.7 | 1,741.2 | 1,662.2 | 1,650.0 | 1,691.7 | 1,708.5 | 100.0 |

| Poland | 373.0 | 337.0 | 267.1 | 292.5 | 302.5 | 314.4 | 18.4 |

| Germany | 238.3 | 242.8 | 244.8 | 236.7 | 242.5 | 241.0 | 14.1 |

| Romania | 229.3 | 207.6 | 202.7 | 190.2 | 186.2 | 203.2 | 11.9 |

| France | 154.1 | 161.0 | 168.0 | 167.3 | 179.0 | 165.9 | 9.7 |

| Netherlands | 150.0 | 156.0 | 156.0 | 155.7 | 156.3 | 154.8 | 9.1 |

| United Kingdom | 149.0 | 139.0 | 141.0 | 129.0 | 139.0 | 139.4 | 8.2 |

| Belgium | 67.0 | 75.4 | 80.4 | 78.7 | 89.1 | 78.1 | 4.6 |

| Spain | 72.0 | 72.4 | 76.0 | 71.7 | 72.1 | 72.8 | 4.3 |

| Italy | 58.7 | 50.4 | 52.4 | 50.4 | 48.1 | 52.0 | 3.0 |

| Denmark | 39.5 | 39.6 | 19.6 | 42.0 | 46.1 | 37.4 | 2.2 |

| Lithuania | 31.7 | 28.3 | 26.8 | 23.0 | 20.8 | 26.1 | 1.5 |

| Portugal | 25.1 | 26.8 | 27.2 | 24.6 | 24.2 | 25.6 | 1.5 |

| Sweden | 24.7 | 23.9 | 23.8 | 23.1 | 24.1 | 23.9 | 1.4 |

| Czech Republic | 23.7 | 23.2 | 24.0 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 1.4 |

| Greece | 24.2 | 24.7 | 23.8 | 20.5 | 20.1 | 22.7 | 1.3 |

| Finland | 20.7 | 22.1 | 22.0 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 1.3 |

| Austria | 21.8 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 20.4 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 1.2 |

| Hungary | 25.1 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 18.7 | 16.4 | 20.4 | 1.2 |

| Bulgaria | 14.9 | 12.8 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 11.5 | 0.7 |

| Latvia | 12.2 | 12.4 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 0.7 |

| Croatia | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 10.2 | 0.6 |

| Ireland | 9.0 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 0.5 |

| Slovakia | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 0.5 |

| Cyprus | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 0.3 |

| Estonia | 5.5 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 0.3 |

| Slovenia | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.2 |

| Malta | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Luxembourg | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

Suggested citation: EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Health) , Jeger M, Bragard C, Caffier D, Candresse T, Chatzivassiliou E, Dehnen‐Schmutz K, Gilioli G, Grégoire J‐C, Jaques Miret JA, Navajas Navarro M, Niere B, Parnell S, Potting R, Rafoss T, Rossi V, Urek G, Van Bruggen A, Van der Werf W, West J, Winter S, Gardi C, Bergeretti F and MacLeod A, 2018. Scientific Opinion on the pest categorisation of Tecia solanivora . EFSA Journal 2018;16(1):5102, 25 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5102

Requestor: European Commission

Question number: EFSA‐Q‐2017‐00322

Panel members: Claude Bragard, David Caffier, Thierry Candresse, Elisavet Chatzivassiliou, Katharina Dehnen‐Schmutz, Gianni Gilioli, Jean‐Claude Grégoire, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Michael Jeger, Alan MacLeod, Maria Navajas Navarro, Björn Niere, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Trond Rafoss, Vittorio Rossi, Gregor Urek, Ariena Van Bruggen, Wopke Van der Werf, Jonathan West and Stephan Winter.

Adopted: 23 November 2017

Notes

Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community. OJ L 169/1, 10.7.2000, p. 1–112.

Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament of the Council of 26 October 2016 on protective measures against pests of plants. OJ L 317, 23.11.2016, p. 4–104.

Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. OJ L 31/1, 1.2.2002, p. 1–24.

See Section 2.1 on what falls outside EFSA's remit.

References

- Anon , 2017a. [Resolution of February 8, 2017, of the Ministry of Rural Development and Natural Resources, which declares the presence of the quarantine pest known as Tecia solanivora (Povolny) or Guatemalan potato moth in various areas of the Principality of Asturias and transitional measures are established for this pest). Boletin oficial del Principado de Asturia, No. 33 DE 10‐II‐2017 [in Spanish] Available online: https://sede.asturias.es/bopa/2017/02/10/2017-01425.pdf

- Anon , 2017b. El Gobierno aprueba el program nacional de control y erradicación de la polilla guatemalteca. Phytoma, 288, p4. [Google Scholar]

- Anon N, 2017c. Núm. 54 Sáturday 4 March 2017 Section I. Page 15749. Real Decreto 197/2017, de 3 de marzo, por el que se establece el Programa nacional de control y erradicación de Tecia (Scrobipalpopsis) solanivora (Povolny). Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2017/03/04/pdfs/BOE-A-2017-2312.pdf

- Arias RJ, Pelaez JA, Penaranda EA, Rocha MN and Munoz GL, 1996. [Evaluation of the incidence and severity of damage of the large potato moth Tecia solanivora in Antioquia Department] [in Spanish]. Actualidades Corpoica, 10, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto N, 2005. Estudios bioecologicos de la polilla guatemalteca de la papa Tecia solanivora (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) en el altiplano Cundiboyacense Colombiano. In: López‐Ávila A (ed.). Memorias III Taller Internacional Sobre la Polilla Guatemalteca de la Papa, Tecia solanivora. Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 16–17 October 2003, pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bosa CF, Cotes AM, Fukumoto T, Bengtsson M and Witzgall P, 2005. Pheromone‐mediated communication disruption in Guatemalan potato moth, Tecia solanivora . Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 114, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International), 2012. Tecia solanivora (potato tuber moth) Datasheet 52956, CABI Crop Protection Compendium Last Modified 1st February 2012 http://www.cabi.org/cpc/datasheet/52956 [Accessed: 30th Sept 2017]

- CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International), 2017. Solanum tuberosum. Datasheet 50561, CABI Crop Protection Compendium. Last Modified 8th February 2017. http://www.cabi.org/cpc/datasheet/50561 [Accessed 14th October 2017]

- Carrillo D and Torrado‐Leon E, 2014. Tecia solanivora Povolny (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), an invasive pest of potatoes Solanum tuberosum L. in the Northern Andes. In: Pena JE (ed). Potential invasive pests of agricultural crops. CABI, Wallingford. pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Roblero EN, Castillo Vera A and Malo EA, 2011. First report of Tecia solanivora (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) attacking the potato Solanum tuberosum in Mexico. Florida Entomologist, 94, 1055–1056. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Health), 2010. PLH Guidance on a harmonised framework for pest risk assessment and the identification and evaluation of pest risk management options by EFSA. EFSA Journal 2010;8(2):1495, 66 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization), 2006a. Tecia solanivora. Diagnostic protocol PM 7/72 (1). EPPO Bulletin, 36, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization), 2006b. Tecia solanivora. Datasheets on Quarantine Pests. EPPO Bulletin, 35, 399–401. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization), 2017. EPPO Global Database (available online). https://gd.eppo.int

- EUROPHYT Notification , 2015. Notification of the presence of the harmful organism Tecia solanivora (elaborated according with commission implementing decision 2014/917/EU), 24th September 2015.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2004. ISPM (International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures) 21—Pest risk analysis of regulated non‐quarantine pests. FAO, Rome, 30 pp. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/sites/default/files/documents//1323945746_ISPM_21_2004_En_2011-11-29_Refor.pdf

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2013. ISPM (International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures) 11—Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests. FAO, Rome, 36 pp. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/sites/default/files/documents/20140512/ispm_11_2013_en_2014-04-30_201405121523-494.65%20KB.pdf

- Germain J‐F, 2002a. Tecia solanivora. Pest Risk Analysis. EPPO doc 02/9829. Available online: https://www.eppo.int/QUARANTINE/Pest_Risk_Analysis/PRA_documents.htm [Accessed 13th October 2017]

- Germain J‐F, 2002b. Tecia solanivora. Pest Risk Analysis. EPPO doc 02/9829. Supplementary information: Tecia solanivora: Indice Eco‐climatique dans la zone OEPP. https://www.eppo.int/QUARANTINE/Pest_Risk_Analysis/PRAdocs_insects/02-9829%20PRA%20Tecia%20solanivorafig.pdf [Accessed 13th October 2017]

- Hilje L, 1994. [Characterization of the damage by the potato moths Tecia solanivora and Phthorimaea operculella in Cartago, Costa Rica.]. Revista Manejo Integrado de Plagas, 31, 43–46 (in Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RW and Becker VO, 1990. Nomenclature of some Neotropical Gelechiidae (Lepidoptera). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 92, 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kroschel J and Schaub B, 2013. Biology and ecology of potato tuber moths as major pests of potato. In: Alyokhin A, Vincent C, Giordanengo P (eds.). Insect Pests of Potato: Global Perspectives on Biology and Management. Academic Press, London. pp 165–192. 10.1016/b978-0-12-386895-4.00006-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroschel J, Mujica N, Carhuapoma P and Sporleder M. (eds.), 2016. Pest distribution and risk atlas for Africa. Potential global and regional distribution and abundance of agricultural and horticultural pests and associated biocontrol agents under current and future climates. Lima (Peru). International Potato Center (CIP). 10.4160/9789290604761-2 [DOI]

- Kutinkova H, Caicedo F and Lingren W, 2016. The Main Pests on Solanacea Crops in Zona 1 of Ecuador. New Knowledge Journal of Science, 5, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Food and the Environment , 2016. Notification of the presence of a harmful organism according to Article 16 of Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Notification to Europhyt, ES‐647.

- Murillo R, 1980. Memoria del primer seminario internacional sobre polillas de la papa Scrobipalposis solavivora Povolny y Phthorimaea operculella Zeller. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganaderia. Actualidades Corpoica, pp 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt B, Beevor P, Cork A, Hall D, Murillo R and Leal H, 1985. Identification of components of the female sex pheromone of the potato tuber moth, Scrobipalpopsis solanivora . Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 38, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Notz A, 1996. Influencia de la Temperatura sobre la Biología de Tecia solanivora (Povolny) (Lepidoptera: Gelechidae) Criadas en Tubérculos de papa Solanum tuberosum L. Boletin de Entomología Venezolana, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Povolný D, 1973. Scrobipalpopsis solvanivora sp.n. A new pest of potato (Solanum tuberosum) from Central America. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae, Facultas Agronomica, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Povolný D, 1993. Zur Taxonomie und Nomenklatur der amerikanischen gnorimoschemoiden Gattungen Tuta Strand, Tecia Strand, Scrobipalpopsis Povolný und Keiferia Busck (Insecta: Lepidoptera – Gelechiidae). Reichenbachia (Dresden), 30, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Povolný D, 2004. The Guatemalan potato tuber moth (Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolný, 1973) before the gateways of Europe (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 52, 183–196. Available online: https://acta.mendelu.cz/media/pdf/actaun_2004052010183.pdf [Accessed 13/10/2017] [Google Scholar]

- Povolný D and Hula V, 2004. A new potato pest invading southwestern Europe, the Guatemala Potato Tuber Moth Scrobilpalpopsis solanivora (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). ENTOMOLOGIA GENERALIS, 27, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Puillandre N, Dupas S, Dangles O, Zeddam JL, Capdevielle‐Dulac C, Barbin K, Torres‐Leguizamon M and Silvain JF, 2008. Genetic bottleneck in invasive species: the potato tuber moth adds to the list. Biological Invasions, 10, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub B, Carhuapoma P and Kroschel J, 2016. Guatemalan potato tuber moth, Tecia solanivora (Povolny 1973). In: Kroschel J, Mujica N, Carhuapoma P and Sporleder M. (eds.). Pest distribution and risk atlas for Africa. Potential global and regional distribution and abundance of agricultural and horticultural pests and associated biocontrol agents under current and future climates. Lima (Peru). International Potato Center (CIP), pp. 24–38. 10.4160/9789290604761-2. [DOI]

- Skarratt DB, Sutherst RW and Maywald GF, 1995. CLIMEX for Windows Version 1.1, User's Guide. Computer software for predicting the effects of climate on plants and animals. CSIRO and CRC for Tropical Pest Management.

- Sutherst RW and Maywald GF, 1985. A computerised system for matching climates in ecology. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment, 13, 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Torres WF, 1989. [Some aspects of the biology and behavior of the potato tuber moth, Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny 1973 (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in the State of Tachira, Venezuela]. MSc.Thesis. Maracay, Venezuela: Central University of Venezuela. [In Spanish]

- Torres F, 1998. Biología y Manejo Integrado de la polilla Centroamericana de la Papa Tecia solanivora en Venezuela. Serie A. No 14, Fondo Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, Fundación para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología del Estado Táchira, Maracay, Venezuela, pp. 60.

- Torres WF, Notz A and Valencia L, 1997. [Life cycle and other aspects of the biology of Tecia solanivora (Povolny) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Tachira state, Venezuela]. Boletin de Entomologia Venezolana, 12, 95–106. [in Spanish]. [Google Scholar]

- Torres‐Leguizamón M, Dupas S, Dardon D, Gómez Y, Niño L, Carnero A, Padilla A, Merlin I, Fossoud A, Zeddam JL, Lery X, Capdevielle‐Dulac C, Dangles O and Silvain JF, 2011. Inferring native range and invasion scenarios with mitochondrial DNA: the case of T. solanivora successive north–south step‐wise introductions across Central and South America. Biological Invasions, 13, 1505–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva Mejia D and Saldamando Benjumea CI, 2013. Tecia solanivora Povolny (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): a Review of its Origin, Dispersion and Biological Control Strategies. Ingeniería y Ciencia, 9, 197–214. Available online: http://publicaciones.eafit.edu.co/index.php/ingciencia/article/view/1927. [Accessed: 17 Oct 2017]. 10.17230/ingciecia.9.18.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]