Abstract

The EFSA Panel on Plant Health performed a pest categorisation of Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), for the EU. C. nenuphar is a well‐defined species, recognised as a serious pest of stone and pome fruit in the USA and Canada where it also feeds on a range of other hosts including soft fruit (e.g. Ribes, Fragaria) and wild plants (e.g. Crataegus). Adults, which are not good flyers, feed on tender twigs, flower buds and leaves. Females oviposit into host fruit; if oviposition occurs in young fruit, the fruit usually falls prematurely reducing yield; oviposition in older fruit causes surface blemishes and the fruit distorts as it develops reducing marketability. Larvae develop within host fruit but exit to pupate in soil. Adults overwinter in leaf litter. C. nenuphar is not known to occur in the EU and is listed in Annex IAI of Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Fruit infested shortly before harvest and soil with leaf litter accompanying plants for planting could potentially provide a pathway into the EU. Considering the climatic similarities between North America and Europe, and that hosts occur widely within the EU, C. nenuphar has potential to establish within the EU. There could be one or two generations per year, as in North America. Impacts could be expected, e.g. in Prunus spp. and apples. Phytosanitary measures are available to reduce the likelihood of introduction of C. nenuphar. All of the criteria assessed by EFSA for consideration as a potential Union quarantine pest are met. C. nenuphar does not meet the criteria of occurring in the EU nor plants for planting being the principal means of spread. Hence it does not satisfy all of the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for it to be regarded as a Union regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP).

Keywords: European Union, pest risk, plant health, plant pest, plum curculio, quarantine

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

Council Directive 2000/29/EC1 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community establishes the present European Union plant health regime. The Directive lays down the phytosanitary provisions and the control checks to be carried out at the place of origin on plants and plant products destined for the Union or to be moved within the Union. In the Directive's 2000/29/EC annexes, the list of harmful organisms (pests) whose introduction into or spread within the Union is prohibited, is detailed together with specific requirements for import or internal movement.

Following the evaluation of the plant health regime, the new basic plant health law, Regulation (EU) 2016/20312 on protective measures against pests of plants, was adopted on 26 October 2016 and will apply from 14 December 2019 onwards, repealing Directive 2000/29/EC. In line with the principles of the above mentioned legislation and the follow‐up work of the secondary legislation for the listing of EU regulated pests, EFSA is requested to provide pest categorisations of the harmful organisms included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC, in the cases where recent pest risk assessment/pest categorisation is not available.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 22(5.b) and Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/20023, to provide scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to prepare and deliver a pest categorisation (step 1 analysis) for each of the regulated pests included in the appendices of the annex to this mandate. The methodology and template of pest categorisation have already been developed in past mandates for the organisms listed in Annex II Part A Section II of Directive 2000/29/EC. The same methodology and outcome is expected for this work as well.

The list of the harmful organisms included in the annex to this mandate comprises 133 harmful organisms or groups. A pest categorisation is expected for these 133 pests or groups and the delivery of the work would be stepwise at regular intervals through the year as detailed below. First priority covers the harmful organisms included in Appendix 1, comprising pests from Annex II Part A Section I and Annex II Part B of Directive 2000/29/EC. The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 1 is June 2018. The second priority is the pests included in Appendix 2, comprising the group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), the group of Tephritidae (non‐EU), the group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms, the group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. and the group of Margarodes (non‐EU species). The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 2 is end 2019. The pests included in Appendix 3 cover pests of Annex I part A section I and all pests categorisations should be delivered by end 2020.

For the above mentioned groups, each covering a large number of pests, the pest categorisation will be performed for the group and not the individual harmful organisms listed under ‘such as’ notation in the Annexes of the Directive 2000/29/EC. The criteria to be taken particularly under consideration for these cases, is the analysis of host pest combination, investigation of pathways, the damages occurring and the relevant impact.

Finally, as indicated in the text above, all references to ‘non‐European’ should be avoided and replaced by ‘non‐EU’ and refer to all territories with exception of the Union territories as defined in Article 1 point 3 of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031.

1.1.2.1. Terms of Reference: Appendix 1

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Aleurocantus spp. | Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) |

| Anthonomus bisignifer (Schenkling) | Oligonychus perditus Pritchard and Baker |

| Anthonomus signatus (Say) | Pissodes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Aschistonyx eppoi Inouye | Scirtothrips aurantii Faure |

| Carposina niponensis Walsingham | Scirtothrips citri (Moultex) |

| Enarmonia packardi (Zeller) | Scolytidae spp. (non‐EU) |

| Enarmonia prunivora Walsh | Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny |

| Grapholita inopinata Heinrich | Tachypterellus quadrigibbus Say |

| Hishomonus phycitis | Toxoptera citricida Kirk. |

| Leucaspis japonica Ckll. | Unaspis citri Comstock |

| Listronotus bonariensis (Kuschel) | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Citrus variegated chlorosis | Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae (Ishiyama) Dye and pv. oryzicola (Fang. et al.) Dye |

| Erwinia stewartii (Smith) Dye | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler (non‐EU pathogenic isolates) | Elsinoe spp. Bitanc. and Jenk. Mendes |

| Anisogramma anomala (Peck) E. Müller | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Kilian and Maire) Gordon |

| Apiosporina morbosa (Schwein.) v. Arx | Guignardia piricola (Nosa) Yamamoto |

| Ceratocystis virescens (Davidson) Moreau | Puccinia pittieriana Hennings |

| Cercoseptoria pini‐densiflorae (Hori and Nambu) Deighton | Stegophora ulmea (Schweinitz: Fries) Sydow & Sydow |

| Cercospora angolensis Carv. and Mendes | Venturia nashicola Tanaka and Yamamoto |

| (d) Virus and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet curly top virus (non‐EU isolates) | Little cherry pathogen (non‐ EU isolates) |

| Black raspberry latent virus | Naturally spreading psorosis |

| Blight and blight‐like | Palm lethal yellowing mycoplasm |

| Cadang‐Cadang viroid | Satsuma dwarf virus |

| Citrus tristeza virus (non‐EU isolates) | Tatter leaf virus |

| Leprosis | Witches’ broom (MLO) |

| Annex IIB | |

| (a) Insect mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Anthonomus grandis (Boh.) | Ips cembrae Heer |

| Cephalcia lariciphila (Klug) | Ips duplicatus Sahlberg |

| Dendroctonus micans Kugelan | Ips sexdentatus Börner |

| Gilphinia hercyniae (Hartig) | Ips typographus Heer |

| Gonipterus scutellatus Gyll. | Sternochetus mangiferae Fabricius |

| Ips amitinus Eichhof | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens (Hedges) Collins and Jones | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Glomerella gossypii Edgerton | Hypoxylon mammatum (Wahl.) J. Miller |

| Gremmeniella abietina (Lag.) Morelet | |

1.1.2.2. Terms of Reference: Appendix 2

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested per group. The list below follows the categorisation included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), such as: | |

| 1) Carneocephala fulgida Nottingham | 3) Graphocephala atropunctata (Signoret) |

| 2) Draeculacephala minerva Ball | |

| Group of Tephritidae (non‐EU) such as: | |

| 1) Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) | 12) Pardalaspis cyanescens Bezzi |

| 2) Anastrepha ludens (Loew) | 13) Pardalaspis quinaria Bezzi |

| 3) Anastrepha obliqua Macquart | 14) Pterandrus rosa (Karsch) |

| 4) Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) | 15) Rhacochlaena japonica Ito |

| 5) Dacus ciliatus Loew | 16) Rhagoletis completa Cresson |

| 6) Dacus curcurbitae Coquillet | 17) Rhagoletis fausta (Osten‐Sacken) |

| 7) Dacus dorsalis Hendel | 18) Rhagoletis indifferens Curran |

| 8) Dacus tryoni (Froggatt) | 19) Rhagoletis mendax Curran |

| 9) Dacus tsuneonis Miyake | 20) Rhagoletis pomonella Walsh |

| 10) Dacus zonatus Saund. | 21) Rhagoletis suavis (Loew) |

| 11) Epochra canadensis (Loew) | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms such as: | |

| 1) Andean potato latent virus | 4) Potato black ringspot virus |

| 2) Andean potato mottle virus | 5) Potato virus T |

| 3) Arracacha virus B, oca strain | 6) non‐EU isolates of potato viruses A, M, S, V, X and Y (including Yo, Yn and Yc) and Potato leafroll virus |

| Group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L., such as: | |

| 1) Blueberry leaf mottle virus | 8) Peach yellows mycoplasm |

| 2) Cherry rasp leaf virus (American) | 9) Plum line pattern virus (American) |

| 3) Peach mosaic virus (American) | 10) Raspberry leaf curl virus (American) |

| 4) Peach phony rickettsia | 11) Strawberry witches’ broom mycoplasma |

| 5) Peach rosette mosaic virus | 12) Non‐EU viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. |

| 6) Peach rosette mycoplasm | |

| 7) Peach X‐disease mycoplasm | |

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Margarodes (non‐EU species) such as: | |

| 1) Margarodes vitis (Phillipi) | 3) Margarodes prieskaensis Jakubski |

| 2) Margarodes vredendalensis de Klerk | |

1.1.2.3. Terms of Reference: Appendix 3

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Acleris spp. (non‐EU) | Longidorus diadecturus Eveleigh and Allen |

| Amauromyza maculosa (Malloch) | Monochamus spp. (non‐EU) |

| Anomala orientalis Waterhouse | Myndus crudus Van Duzee |

| Arrhenodes minutus Drury | Nacobbus aberrans (Thorne) Thorne and Allen |

| Choristoneura spp. (non‐EU) | Naupactus leucoloma Boheman |

| Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) | Premnotrypes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetverikov | Pseudopityophthorus minutissimus (Zimmermann) |

| Diabrotica barberi Smith and Lawrence | Pseudopityophthorus pruinosus (Eichhoff) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber | Scaphoideus luteolus (Van Duzee) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Mannerheim | Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) |

| Diabrotica virgifera zeae Krysan & Smith | Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) |

| Diaphorina citri Kuway | Spodoptera litura (Fabricus) |

| Heliothis zea (Boddie) | Thrips palmi Karny |

| Hirschmanniella spp., other than Hirschmanniella gracilis (de Man) Luc and Goodey | Xiphinema americanum Cobb sensu lato (non‐EU populations) |

| Liriomyza sativae Blanchard | Xiphinema californicum Lamberti and Bleve‐Zacheo |

| (b) Fungi | |

| Ceratocystis fagacearum (Bretz) Hunt | Mycosphaerella larici‐leptolepis Ito et al. |

| Chrysomyxa arctostaphyli Dietel | Mycosphaerella populorum G. E. Thompson |

| Cronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phoma andina Turkensteen |

| Endocronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phyllosticta solitaria Ell. and Ev. |

| Guignardia laricina (Saw.) Yamamoto and Ito | Septoria lycopersici Speg. var. malagutii Ciccarone and Boerema |

| Gymnosporangium spp. (non‐EU) | Thecaphora solani Barrus |

| Inonotus weirii (Murril) Kotlaba and Pouzar | Trechispora brinkmannii (Bresad.) Rogers |

| Melampsora farlowii (Arthur) Davis | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Tobacco ringspot virus | Pepper mild tigré virus |

| Tomato ringspot virus | Squash leaf curl virus |

| Bean golden mosaic virus | Euphorbia mosaic virus |

| Cowpea mild mottle virus | Florida tomato virus |

| Lettuce infectious yellows virus | |

| (d) Parasitic plants | |

| Arceuthobium spp. (non‐EU) | |

| Annex IAII | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Meloidogyne fallax Karssen | Popillia japonica Newman |

| Rhizoecus hibisci Kawai and Takagi | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Clavibacter michiganensis (Smith) Davis et al. ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al. | Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith) Yabuuchi et al. |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Melampsora medusae Thümen | Synchytrium endobioticum (Schilbersky) Percival |

| Annex IB | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say | Liriomyza bryoniae (Kaltenbach) |

| (b) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet necrotic yellow vein virus | |

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) is one of a number of pests listed in the Appendices to the Terms of Reference (ToR) to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of a quarantine pest or those of a regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) for the area of the EU excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States (MS) referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Literature search

A literature search on C. nenuphar was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name of the pest as search term. Relevant papers were reviewed and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.2. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plan Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO Global database, 2018) and relevant publications.

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Communities).

The Europhyt database was consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission, and is a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. The Europhyt database manages notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the MS and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread.

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for C. nenuphar following guiding principles and steps in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures No 11 (FAO, 2013), No 21 (FAO, 2004) and EFSA PLH Panel (2018).

This work was initiated following an evaluation of the EU plant health regime. Therefore, to facilitate the decision‐making process, in the conclusions of the pest categorisation, the Panel addresses explicitly each criterion for a Union quarantine pest and for a Union RNQP in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants, and includes additional information required in accordance with the specific terms of reference received by the European Commission. In addition, for each conclusion, the Panel provides a short description of its associated uncertainty.

Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. All relevant criteria have to be met for the pest to potentially qualify either as a quarantine pest or as a RNQP. If one of the criteria is not met, the pest will not qualify. A pest that does not qualify as a quarantine pest may still qualify as a RNQP that needs to be addressed in the opinion. For the pests regulated in the protected zones only, the scope of the categorisation is the territory of the protected zone; thus, the criteria refer to the protected zone instead of the EU territory.

Table 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding protected zone quarantine pest (articles 3235) | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1) | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU? Describe the pest distribution briefly! |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a protected zone quarantine organism | Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a regulated non‐quarantine pest. (A regulated non‐quarantine pest must be present in the risk assessment area) |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3) | If the pest is present in the EU but not widely distributed in the risk assessment area, it should be under official control or expected to be under official control in the near future. |

The protected zone system aligns with the pest free area system under the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). The pest satisfies the IPPC definition of a quarantine pest that is not present in the risk assessment area (i.e. protected zone). |

Is the pest regulated as a quarantine pest? If currently regulated as a quarantine pest, are there grounds to consider its status could be revoked? |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways! |

Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the protected zone areas? Is entry by natural spread from EU areas where the pest is present possible? |

Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects? Clearly state if plants for planting is the main pathway! |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the protected zone areas? | Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the protected zone areas such that the risk becomes mitigated? Is it possible to eradicate the pest in a restricted area within 24 months (or a period longer than 24 months where the biology of the organism so justifies) after the presence of the pest was confirmed in the protected zone? |

Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as potential protected zone quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met. |

It should be noted that the Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, the Panel will present a summary of the observed pest impacts. Economic impacts are expressed in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, whereas addressing social impacts is outside the remit of the Panel.

The Panel will not indicate in its conclusions of the pest categorisation whether to continue the risk assessment process, but following the agreed two‐step approach, will continue only if requested by the risk managers. However, during the categorisation process, experts may identify key elements and knowledge gaps that could contribute significant uncertainty to a future assessment of risk. It would be useful to identify and highlight such gaps so that potential future requests can specifically target the major elements of uncertainty, perhaps suggesting specific scenarios to examine.

3. Pest categorisation

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible?

Yes, the identity of the pest is established.

C. nenuphar (Herbst) is an insect within the family Curculionidae. In North America, it has the common name plum curculio (Bosik, 1997).

The species was first characterised and formally described as Curculio nenuphar in 1797 by Herbst (1797) (cited in Quaintance and Jenne, 1912). The species was placed in the genus Conotrachelus by Dejean (1835). The taxonomy of the organism appears to have been stable since then. A key to identify the genus Conotrachelus is provided by Arnett (1971). Schoof (1942) provides a key to species within the genus.

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

C. nenuphar is an oligophagous weevil feeding on Rosaceae (see Section 3.4.1). In Canada and north of Virginia in the USA, C. nenuphar has one generation per year (Racette et al., 1992). Adults emerge from their overwintering sites in the spring and early summer, from mid‐April to early July (Armstrong, 1958). Males and females aggregate at the base of host trees at the edges of orchards and move between the ground level and the host canopy, mainly by crawling although adults can fly. Prokopy et al. (1999) reported flight did not occur below 20°C. In general, the insect is an infrequent flier; above 20°C short distance flights are used to reach the canopy of host trees from within orchards and to return to the ground (Chen et al., 2006). Movement between the canopy and ground may be influenced by humidity (Racette et al., 1992).

Emerging adults feed on tender shoots and twigs, flower buds and leaves of hosts to undergo maturation (Racette et al., 1992). After mating, females chew small round holes in the skin of young host fruit before depositing a single egg. After oviposition, the female makes a crescent‐shaped wound in the skin of the fruit below the oviposition puncture (Eaton and Maccini, 2016). The wound prevents the fruit cells in the vicinity of the egg from developing normally and so protects the egg from being crushed within the swelling fruit. Females can lay an average of 75 eggs (range approximately 30–190), the maximum rate of oviposition is 25 eggs in 48 h (Armstrong, 1958; Mampe and Neunzig, 1967).

At mean daily temperatures of 19.3–23.3°C, eggs take 4–7 days to hatch. At a constant 27.8°C, eggs hatch in just under 3 days (Campbell et al., 1989). There are four larval instars.

Enzymes released by larvae feeding in fruit cause the fruit to drop prematurely, e.g. in apples before the fruit reaches 3 cm diameter (Levine and Hall, 1978). Larvae continue to feed within the fallen fruit for up to around 30 days (Armstrong, 1958). Larvae exit fallen fruit to pupate in the soil at depths of 1–8 cm (Racette et al., 1992). If infested fruit does not fall, the larvae are crushed and killed within the developing fruit (Quaintance and Jenne, 1912). Infested cherry fruit do not drop but instead rot on the tree. Multiple eggs can be laid in a single host fruit, for example in a heavily infested apricot orchard Armstrong (1958) reported up to 13 larvae per fruit. At 27.7°C, the average time spent in the fruit from egg deposition to larval emergence was around 13 days (range 9–24 days) (Armstrong, 1958).

Development from final instar larva to adult takes 32–45 days (Armstrong, 1958). Adults emerge in mid‐ to late summer, then feed for a short while before seeking overwintering sites. Forest with a thick layer of fallen leaves, providing shelter from desiccation, is a favoured overwintering habitat (Lafleur et al., 1987; Racette et al., 1992).

From Virginia southwards, there are two generations, and sometimes a partial third generation depending of temperature. For example, in Mississippi, eggs laid by overwintered adults in May develop more quickly given the higher temperatures than in the north, such that larvae can be found from late‐May to July, pupae from mid‐June to late‐July and adults from early July to October. The earliest summer emerging adults can mate and produce another partial generation of adults by late September. Adults of both summer and autumn populations move out of orchards to overwinter in leaf litter and weedy areas, although generally not in the soil itself (Sarai, 1969; Lafleur et al., 1987).

Akotsen‐Mensah et al. (2011) developed a day‐degree phenology model linking accumulated temperature with weekly trap captures in Alabama peach orchards. The spring generation of adults peaked at 245 DD above 10°C after 1 January; the summer generation of adults peaked at 1,105 DD and a late summer generation peaked at 1,758 DD.

3.1.3. Intraspecific diversity

Zhang et al. (2008) reports there are two strains of C. nenuphar that can be distinguished genetically; a northern univoltine strain and a southern multivoltine strain. The individuals from different regions are morphologically indistinguishable.

3.1.4. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, C. nenuphar can be detected in orchards. Beating (shaking) branches is a traditional method to dislodge adults. Visual inspection of host fruit can detect damage symptoms and fruit suspected of being infested can be cut open to find immature stages. The species can be identified by examining morphological features, for which keys exist.

If the presence of C. nenuphar is expected, hosts at the outer edges of orchards should be monitored regularly during the period of flowering up to petal fall for feeding or egg laying punctures on young fruit (Eaton and Maccini, 2016).

Several methods have been used to detect adult C. nenuphar in orchards. Johnson et al. (2002) lists methods such as beating and shaking branches and collecting adults that are dislodged and fall onto white sheets under the branches, using green painted sticky‐coated ping pong balls, pitfall traps, pyramid traps, screen traps and sticky‐trunk bands.

A simple description of eggs, larva, pupa and adults is provided in Smith et al. (1997). Final instar larvae are 6–9 mm long. Adults are about 4–6 mm long with black, grey and brown specks. A detailed description of life stages is provided in Quaintance and Jenne (1912).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

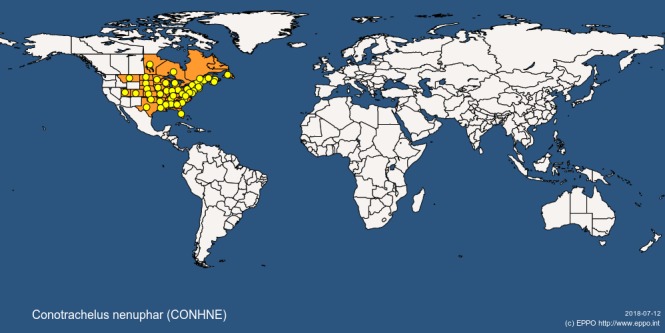

C. nenuphar is native to North America east of the Rocky Mountains, ranging from Quebec (Canada) in the north to Florida (USA) in the south. The distribution of C. nenuphar in North America broadly conforms to the distribution of its native wild hosts Prunus nigra, Prunus americana and Prunus mexicana (Smith and Flessel, 1968). Since about 1980, an isolated population, west of the Rocky Mountains, has been present in northern Utah where it is treated as a quarantine pest (Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, 1999; Alston and Stark, 2003; Alston et al., 2005) (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Global distribution of Conotrachelus nenuphar (extracted from the EPPO Global Database accessed on 12/7/2018)

Table 2.

Distribution of C. nenuphar outside the EU (Source: EPPO Global database, 2018)

| Region | Country | Subnational distribution (e.g. States/provinces) | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Canada | Present, restricted distribution | |

| Manitoba | Present, no details | ||

| New Brunswick | Present, no details | ||

| Newfoundland | Present, no details | ||

| Nova Scotia | Present, no details | ||

| Ontario | Present, no details | ||

| Prince Edward Island | Present, no details | ||

| Québec | Present, no details | ||

| USA | Present, restricted distribution | ||

| Alabama | Present, no details | ||

| Arkansas | Present, no details | ||

| Colorado | Present, no details | ||

| Connecticut | Present, no details | ||

| Delaware | Present, no details | ||

| Florida | Present, no details | ||

| Georgia | Present, no details | ||

| Illinois | Present, no details | ||

| Indiana | Present, no details | ||

| Iowa | Present, no details | ||

| Kansas | Present, no details | ||

| Kentucky | Present, no details | ||

| Louisiana | Present, no details | ||

| Maine | Present, no details | ||

| Maryland | Present, no details | ||

| Massachusetts | Present, no details | ||

| Michigan | Present, no details | ||

| Minnesota | Present, no details | ||

| Mississippi | Present, no details | ||

| Missouri | Present, no details | ||

| Montana | Present, no details | ||

| Nebraska | Present, no details | ||

| New Hampshire | Present, no details | ||

| New Jersey | Present, no details | ||

| New York | Present, no details | ||

| North Carolina | Present, no details | ||

| North Dakota | Present, no details | ||

| Ohio | Present, no details | ||

| Oklahoma | Present, no details | ||

| Pennsylvania | Present, no details | ||

| Rhode Island | Present, no details | ||

| South Carolina | Present, no details | ||

| South Dakota | Present, no details | ||

| Tennessee | Present, no details | ||

| Texas | Present, no details | ||

| Utah | Present, no details | ||

| Vermont | Present, no details | ||

| Virginia | Present, no details | ||

| West Virginia | Present, no details | ||

| Wisconsin | Present, no details |

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU?

No. C. nenuphar is not known to occur in the EU.

The absence of C. nenuphar from the Netherlands has been confirmed by survey and Slovenia declares that C. nenuphar is absent from its territory on the basis that there are no records of it in the country (EPPO global database, 2018).

3.3. Regulatory Status

3.3.1. Council Directive 2000/29/EC

C. nenuphar is listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Details are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Conotrachelus nenuphar in Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex I, Part A | Harmful organisms whose introduction into, and spread within, all member states shall be banned. |

| Section I | Harmful organisms not known to occur in any part of the community and relevant for the entire community. |

| (a) | Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development. |

| Species | |

| 10. | Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) |

3.3.2. Legislation addressing the hosts of Conotrachelus nenuphar

Table 4.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve that may involve Conotrachelus nenuphar in Annexes III, IV and V of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex III, Part A | Plants, plant products and other objects the introduction of which shall be prohibited in all Member States | |

| Description | Country of origin | |

| 9. | Plants of […] Cydonia Mill., […], Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., […], intended for planting, other than dormant plants free from leaves, flowers and fruit | Non‐European countries |

| 18. | Plants of Cydonia Mill., Malus Mill., Prunus L. and Pyrus L. and their hybrids, and Fragaria L intended for planting, other than seeds |

Without prejudice to the prohibitions applicable to the plants listed in Annex III A (9), where appropriate, non‐European countries, other than Mediterranean countries, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the continental states of the USA |

| Annex IV Part A1 | Special requirements which shall be laid down by all member states for the introduction and movement of plants, plant products and other objects into and within all member states | |

| 44. | Herbaceous perennial plants, intended for planting, other than seeds, of the families […]and Rosaceae (except Fragaria L.), originating in third countries, other than European and Mediterranean countries |

Without prejudice to the requirements applicable to plants, where appropriate, listed in Annex IV(A)(I)(32.1), (32.2), (32.3), (33) and (34) official statement that the plants: — have been grown in nurseries, and — are free from plant debris, flowers and fruits, and — have been inspected at appropriate times and prior to export, and — found from symptoms of harmful bacteria, viruses and virus‐like organisms, and — either found free from signs or symptoms of harmful nematodes, insects, mites and fungi, or have been subjected to appropriate treatment to eliminate such organisms. |

| Annex V | Plants, plant products and other objects which must be subject to a plant health inspection ((…)—in the country of origin or the consignor country, if originating outside the Community) before being permitted to enter the Community | |

| Part B | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in territories, other than those referred to in Part A | |

| Section I | Plants, plant products and other objects which are potential carriers of harmful organisms of relevance for the entire Community | |

| 1. | Plants, intended for planting, […], originating in […] the USA. […] Prunus L., Rubus L., […] | |

| 2. |

Parts of plants, other than fruits and seeds of: — Prunus L., originating in non‐European countries, |

|

| 3. |

Fruits of: — Citrus L., Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids […] — […] Cydonia Mill., […] Diospyros L., Malus Mill., […], Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L. […], and Vaccinium L., originating in non‐European countries. |

|

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Host range

Although native to North America, C. nenuphar has widened its host range to feed on introduced rosaceous fruits now grown in orchards in North America, such as Prunus domestica, Prunus persica and Malus domestica (Quaintance and Jenne, 1912; Maier, 1990; Jenkins et al., 2006).

When combined, the EPPO Global database (accessed on 12/7/2018) and CABI (2018) provide a list of approximately 37 hosts (Appendix A). Around 73% of the hosts listed belong to Rosaceae with the majority of species being Prunus spp. Major hosts highlighted by EPPO include P. persica and P. domestica. EPPO also lists Hemerocallis lilioasphodelus (Asphodelaceae) as a major host. CABI (2018) adds P. americana, Prunus armeniaca, Prunus avium, Prunus cerasus and Prunus salicina to the list of main hosts.

In a host preference field trial using mark‐recapture of adults in orchards with a range of hosts in West Virginia, Leskey and Wright (2007) determined that P. salicina (Japanese plum) was the most highly preferred host followed by P. domestica, P. persica, P. avium, P. cerasus, P. armeniaca, M. domestica and Pyrus communis, respectively.

As a pest listed in Annex I/AI of 2000/29 EC, C. nenuphar is prohibited from entry into the EU, regardless of how it arrives. It is therefore regulated on all its hosts and possible pathways. This contrasts to Annex II/AI pests that are absent from the EU and are regulated only on certain plants or plant products specified in the Annex.

3.4.2. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory?

Yes, C. nenuphar could potentially enter the EU with host plants for planting, in infested fruit, as pupae in soil, or in leaf litter from North America (USA and Canada).

The potential pathways are:

host plants for planting,

infested host fruit,

soil,

leaf litter.

Current EU legislation regulates plants for planting of Prunus and several other C. nenuphar host genera (e.g. Malus, Pyrus and Cydonia, see Section 3.3.2). While these plants for planting are prohibited from entering the EU from non‐European countries, dormant plants (free from leaves, flowers and fruit) can be imported from continental USA and Canada, where C. nenuphar occurs. However, C. nenuphar is unlikely to be closely associated with dormant nursery stock, especially if bare‐rooted. If dormant nursery stock is transported with soil and leaf litter, the chance of association increases.

While much of the literature refers to immature fruit dropping early due to larval infestation, Quaintance and Jenne (1912) refer to mature peaches being infested at harvest time in southern States. Presumably such infestation is caused by adults ovipositing on much more mature fruit. Quaintance and Jenne (1912) also refer to C. nenuphar larvae surviving in apple varieties that ripen early in the year. Again, it is presumed that oviposition in these apples would have occurred after the fruit had swollen and hence developing larvae avoid being crushed. It is perhaps these fruit that are most likely to provide a pathway. There are no specific import requirements for fruits that can be used as a host plant. Nevertheless, there are no records of interceptions or outbreaks of C. nenuphar, or any other Conotrachelus spp. in the Europhyt database. To date, C. nenuphar has not spread outside its native range and CABI (2018) does not consider it to be a global invasive species.

Within the USA, an isolated population of C. nenuphar has existed in northern Utah, west of the Rocky Mountains, since about 1980 where it is restricted to neglected or unmanaged sites such as domestic gardens, roadside wild plum and neglected orchards (Alston et al., 2005). Zhang et al. (2008) speculated that it may have entered Utah via human activity. Table 5 shows import of Rosaceae fruits from Canada and the USA from 2013 to 2017.

Table 5.

Import of host commodities (fruits) from countries where Conotrachelus nenuphar occurs (quantity in 100 kg) data from Eurostat Easy Comext (accessed on 13/7/2018)

| Source | Canada | United States | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Fresh apples | 1,250 | 1,979 | 2,450 | 2,355 | 1,377 | 120,811 | 90,049 | 6,2117 | 42,907 | 24,264 |

| Fresh pears | – | 145 | – | – | 21 | 13,001 | 9,191 | 3,679 | 438 | 615 |

| Fresh plums | – | 56 | – | – | 3 | 144 | 118 | 10 | – | 44 |

| Fresh quinces | – | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | 39 |

| Fresh apricots | – | – | – | – | 0 | 595 | 8 | – | – | 3 |

| Fresh peaches and nectarines | 0 | – | – | – | 1 | 42 | 0 | – | – | 10 |

Imports to the EU of plants for planting of Malus, Prunus, Pyrus and Vaccinium occurred during the period 2012–2015 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Instances of the import of plants for planting of Conotrachelus nenuphar host genera from USA into the Netherlands 2012–2015. Source: ISEFOR database

| Host genus | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malus | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Prunus | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pyrus | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Vaccinium | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

3.4.3. Establishment

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory?

Yes, host plants are available throughout the EU and host distribution overlaps with suitable climatic regions to support long term survival of C. nenuphar within the EU.

3.4.3.1. EU distribution of main host plants

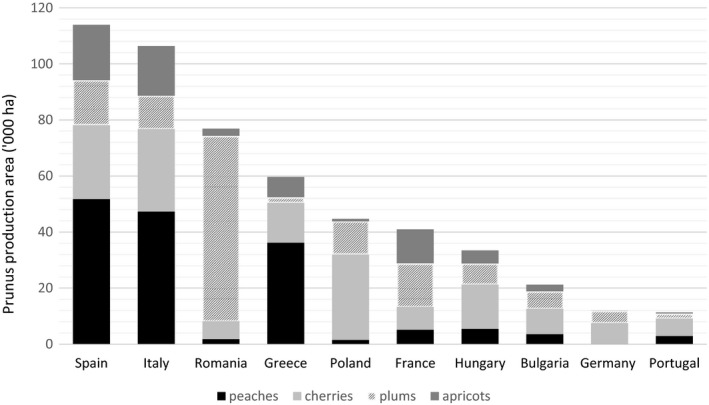

C. nenuphar hosts such as peaches, plums and apricots as well as apples and pears occur widely over the EU growing as commercial crops and in small orchards and home‐gardens (de Rougemont, 1989) (Table 7 and Figure 2). Hosts also occur as wild plants (e.g. Crataegus). Appendix B details the area of apple, pear, cherry and blueberry production in individual EU MS.

Table 7.

Crop production area in EU28 (cultivation/harvested/production) (1,000 ha) Eurostat (accessed on 13/7/2018 and 21/9/2018)

| Crop plant/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apricots | 70.56 | : | 69.5 | 72.31 | : |

| Peaches | 163.87 | : | 157.81 | 156.38 | 154.21 |

| Cherries | : | : | 173.76 | 173.3 | : |

| Plums | 162.01 | 157.36 | 154.79 | 152.73 | : |

‘:’ data not available.

Figure 2.

Mean annual crop production area of key Prunus hosts (apricots, cherries, peaches and plums) 2013–2017, for the top 10 EU producing countries by area. Source: Eurostat (accessed on 13/7/2018)

These countries represent > 95% of the area of EU apricot, cherry, peach and plum area.

3.4.3.2. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

C. nenuphar is distributed across North America (see Figure 1) within a variety of Köppen–Geiger climate zones. The global Köppen–Geiger climate zones (Kottek et al., 2006) describe terrestrial climate in terms of average minimum winter temperatures and summer maxima, amount of precipitation and seasonality (rainfall pattern). In North America, C. nenuphar occurs in a number of zones such as Dfb (continental, uniform precipitation, warm summer) and Cfb (warm temperate, fully humid, warm summer). These climate zones also occur in the EU where hosts such as Prunus and Malus are grown. We assume that climatic conditions in the EU will not limit the ability of C. nenuphar to establish.

3.4.4. Spread

Is the pest able to spread within the EU territory following establishment? How?

Yes, as a free living organism C. nenuphar adults can disperse naturally, e.g. by walking and flying. No vector is required to aid dispersal.

RNQPs: Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects?

No, plants for planting would not be the main means of spread.

C. nenuphar has no history of international spread. CABI (2018) does not consider C. nenuphar likely to be an internationally invasive species. Nevertheless, C. nenuphar has crossed the Rocky Mountains and been introduced from eastern USA into western USA, perhaps via human activity (Zhang et al., 2008). Although C. nenuphar may have been present in Utah since 1980, a survey in 2000 indicates the pest is limited to a 50 square mile area (Alston and Stark, 2003). If C. nenuphar was introduced into the EU, it could spread naturally by adults slowly walking, or in temperatures above 20°C, flying short distances. In flight mill experiments, Chen et al. (2006) reported adults flew for a maximum of 2 min at a time and the median distance travelled within 24 h was approximately 120 m (range < 1 m to approx. 8,000 m). Flight mills experiments are artificial and in general, the insect is an infrequent flier moving only short distances between the ground and canopy of host trees (Chen et al., 2006).

Lafleur and Hill (1987) reviewed the literature on C. nenuphar dispersal within orchards and concluded dispersal was limited. Lafleur and Hill (1987) also conducted capture‐mark‐recapture experiments to measure adult movements in the spring. Results show that in spring and summer adults moved from the outer edge of an orchard towards the centre, with most adults spreading by a few tens of metres. Many of the recaptured adults were recovered from the same tree that they were first found on. The greatest distance moved by an individual was 129 m in 28 days. Adult movement in the autumn was studied by Lafleur et al. (1987) who found adults moved from orchards into adjacent woodland to seek overwintering sites. Adults showed a net rate of spread of up to 3 m per day.

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes, if introduced into the EU, economic impacts on hosts such as Prunus and Malus could be expected.

RNQPs: Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? 4

Not relevant (absent in EU). In case that the pest were in the EU, its presence on plants for planting would have an economic impact.

C. nenuphar is a significant pest of stone fruits and is most harmful to plums, apricot and sweet cherry. It is an important pest in peaches in the south‐eastern USA (Yonce et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 2002; Horton and Johnson, 2005). C. nenuphar frequently causes serious damage to apple, pear and peach (Campbell et al., 1989). If not managed, C. nenuphar can be one of the most significant economic pests of pome and stone fruits throughout most of its geographic range (Hoyt et al., 1983). The relevance of C. nenuphar as a pest of particular orchard crops varies between regions. For example, in north‐eastern USA C. nenuphar is more important on apples than on peaches but in the south‐eastern USA the reverse is true, simply because peaches are a more widely grown crop in the south‐east (Akotsen‐Mensah, 2010).

Most damage is caused in neglected and uncultivated orchards, or those close to woods, thickets and weedy areas which provide overwintering habitat (Campbell et al., 1989). Damage is caused by adults feeding on new shoots, blossom buds, and tender twigs and leaves. Yield loss occurs when infested fruit drop prematurely. However, the most serious damage to fruit results from the crescent‐shaped wounds females create after oviposition. Such damage causes the infested fruit to grow in a misshapen manner reducing marketability of fruit that doesn't drop.

The main control method to manage C. nenuphar in orchards is to apply an insecticide treatment targeting adults, applying it after flowers emerge, or after the first oviposition scar is observed on fruit (Prokopy, 1985). Between 1977 and 1989, C. nenuphar damage in commercial apple orchards in Quebec, conventionally managed with insecticides, was usually below 1% but in unsprayed orchards damage varied between 6% and 85% (Vincent and Roy, 1992). When chemical spraying was stopped, pest populations returned to levels of economic importance within between 1 and 3 years (Glass and Lienk, 1971; Hall, 1974).

3.6. Availability and limits of mitigation measures

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes (see Section 3.3), entry could be inhibited if plants for planting are sourced from pest free areas or checked for pest presence (overwintering adults) in growing media. Consignments of fruit that could potentially carry the pest could be inspected. Additional control measures are also available (see text below).

RNQPs: Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Not relevant (absent in EU)

Yes, plants for planting could be sourced from pest free areas and inspected on entry to the EU.

3.6.1. Identification of additional measures

As a pest listed in Annex I/AI of 2000/29 EC, C. nenuphar is prohibited from entry into the EU, regardless of how it arrives. It is therefore regulated on all its hosts and possible pathways (see Section 3.3). However, additional control measures that maybe considered are shown below.

3.6.1.1. Additional control measures

Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance. Potential control measures relevant to C. nenuphar are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Selected control measures for pest entry and establishment (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018)

| Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Control measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1175887 | As a pest that is a poor flyer and which does not disperse widely, growing plants in isolation is a measure to consider. Non‐orchard hosts could be grown within physical protection, e.g. a dedicated structure such as glass or plastic greenhouse. Pathway: plants for planting | Entry |

| Chemical treatments on crops including reproductive material (Work in progress, not yet available) | Chemical control targeting adults around the time of oviposition is a primary means of pest control (Prokopy, 1985). Pathway: fruit | Entry |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1175929 |

The physical and chemical cleaning and disinfection of facilities, tools, machinery, transport means, facilities and other accessories Larvae from fruit infested close to ripening may exit the fruit to pupate. If this occurred during transport or storage cleaning the packaging (boxes) may help. (Pathway: fruit) |

Entry |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180171 | C. nenuphar did not survive in artificially infested apple fruit held in a controlled atmosphere of between 0°C and 3°C with 3% O2 and 2–8% CO2 for 33 days (Glass et al., 1961). (Pathway: fruit) | Entry |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181442 |

Treatment of the waste (deep burial, composting, incineration, chipping, production of bio‐energy…) in authorised facilities and official restriction on the movement of waste Consignments intercepted with C. nenuphar should be disposed of appropriately. (Pathway: plants for planting and fruit) |

Establishment |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181436 | Good orchard sanitation is an effective way to reduce adult populations. Good pruning to allow light and the wind to penetrate the canopy will reduce humidity and provide less favourable conditions for adults. Fallen fruit should be collected and destroyed (Racette et al., 1992). (Pathway: fruit) | Entry |

| https://zenodo.org/record/1181717#.W8zPxGcUnIV |

Crop rotation, associations and density, weed/volunteer control are used to prevent problems related to pests and are usually applied in various combinations to make the habitat less favourable for pests Although orchard hosts are not rotated, weeds at the edges of orchards should be well managed to remove suitable overwintering sites. Adults overwintering in the turf of orchards suffer high mortality (Lafleur et al., 1987; Racette et al., 1992). (Pathway: fruit) |

Entry |

3.6.1.2. Additional supporting measures

Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance. Potential supporting measures relevant to C. nenuphar are listed below in Table 9, which includes sourcing plants from pest free areas.

Table 9.

Additional supporting measures for pest entry and establishment (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018)

| Nr | Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Supporting measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.01 | http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181430 | Imported host plants for planting and fruit could be inspected for compliance from freedom of C. nenuphar | Entry |

| 2.02 | http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181213 | Examination, other than visual, to determine if pests are present using official diagnostic protocols | Entry |

| 2.03 | Sampling (Work in progress, not yet available) | According to ISPM 31, it is usually not feasible to inspect entire consignments, so phytosanitary inspection is performed mainly on samples obtained from a consignment | Entry |

| 2.04 | Phytosanitary certificate and plant passport (Work in progress, not yet available) | An official paper document or its official electronic equivalent, consistent with the model certificates of the IPPC, attesting that a consignment meets phytosanitary import requirements (ISPM 5) | Entry |

| 2.05 | http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180845 | Mandatory/voluntary certification/approval of premises is a process including a set of procedures and of actions implemented by producers, conditioners and traders contributing to ensure the phytosanitary compliance of consignments. It can be a part of a larger system maintained by a National Plant Protection Organization in order to guarantee the fulfilment of plant health requirements of plants and plant products intended for trade | Entry |

| 2.06 | Certification of reproductive material (voluntary/official) (Work in progress, not yet available) | Reproductive material could be examined and certified free from C. nenuphar | Entry |

| 2.07 | http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180597 | Sourcing plants from a pest free place of production, site or area, surrounded by a buffer zone, would minimise the probability of spread into the pest free zone | Entry |

| 2.08 | Surveillance (Work in progress, not yet available) | ISPM 5 defines surveillance as an official process which collects and records data on pest occurrence or absence by survey, monitoring or other procedures | Establishment |

3.6.1.3. Biological or technical factors limiting the feasibility and effectiveness of measures to prevent the entry, establishment and spread of the pest

C. nenuphar can be well controlled at source through the application of correctly timed insecticides, e.g. in apples during the pink and petal‐fall stages and in peaches and cherries during petal‐fall and shuck‐split stages. An important pest control action is to destroy the fallen damaged host fruits before the adults emerge. Removal of unmanaged orchard trees is also important (Prokopy, 1985; Racette et al., 1992; Akotsen‐Mensah, 2010). However, if chemical application is mistimed, larvae developing inside fruit are protected from contact insecticides and natural enemies.

Overall, there are no major limiting factors affecting quarantine regulations.

3.6.1.4. Biological or technical factors limiting the ability to prevent the presence of the pest on plants for planting

A small proportion of adults could overwinter in any leaf litter around plants for planting and could be transported with the dormant plants if such leaf litter was carried with the plants.

3.7. Uncertainty

By its very nature of being a rapid process, all pest categorisations contain uncertainties. However, the uncertainties in this case are insufficient to affect the conclusion of the categorisation.

4. Conclusions

Considering the criteria within the remit of EFSA to assess its regulatory plant health status, C. nenuphar meets the criteria for consideration as a potential Union quarantine pest (it is absent from the EU, potential pathways exist, and its establishment would cause an economic impact). Given that C. nenuphar is not known to occur in the EU and plants for planting are not the primary means of spread, it fails to meet some of the criteria required for RNQP status. Table 10 provides a summary of the conclusions of each part of this pest categorisation.

Table 10.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1) | The identity of the pest is established. Conotrachelus nenuphar is a recognisable species with stable taxonomy and nomenclature | The identity of the pest is established. Conotrachelus nenuphar is a recognisable species with stable taxonomy and nomenclature. | None |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2) | C. nenuphar is not known to occur in the EU | C. nenuphar is not known to occur in the EU (A criterion to satisfy the definition of a regulated non‐quarantine pest is that the pest must be present in the risk assessment area) | None |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3) | Conotrachelus nenuphar is listed in I/AI of 2000/29 EC | Conotrachelus nenuphar is listed in I/AI of 2000/29 EC | None |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) |

The pest could potentially enter, establish and spread in the EU Pathways include larvae in infested host fruit, pupae in soil and overwintering adults in the soil around the roots of dormant plants for planting |

If C. nenuphar established within the EU, plants for planting would not be the principle mechanism for further spread. As a mobile insect, capable of flight, spread would occur naturally | None |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | The establishment of the pest in the EU could potentially cause yield and quality losses in hosts, particularly Prunus spp. and Malus | C. nenuphar is not normally associated with host plants for planting (i.e. dormant fruit plants), instead it feeds on hosts when actively growing | None |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | Phytosanitary measures are available to reduce the likelihood of entry into the EU, e.g. sourcing fruit from pest free areas; sourcing host plants for planting from pest free areas; prohibiting soil and leaf litter from being carried with host plants for planting | Host plants for planting should be imported free from soil and leaf litter to minimise the likelihood that overwintering adults are carried with dormant hosts | None |

| Conclusion on pest categorisation (Section 4) | Conotrachelus nenuphar satisfies all of the criteria assessed by EFSA PLH Panel to satisfy the definition of a Union quarantine pest | Conotrachelus nenuphar does not meet the criteria of (a) occurring in the EU territory, and (b) plants for planting being the principal means of spread. Hence it does not satisfy all of the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA PLHP to assess to be regarded as a Union RNQP | None |

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate | This categorisation has been precautionary. A future assessment (if necessary) should focus on likelihood of entry; entry via fruit is unlikely as infested fruit drops prematurely or is unmarketable. Soil (potentially containing pupae) and leaf litter (potentially containing overwintering adults) are potential but also unlikely pathways | ||

Abbreviations

- DG SANTÉ

Directorate General for Health and Food Safety

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- HS

Harmonized System (6 digit World Customs Organization system to categorize goods)

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

protected zone

- RNQP

regulated non‐quarantine pest

- RRO

risk reduction option

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

Glossary

(terms defined in ISPM 5 unless indicated by +)

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control measures+

Measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance.

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2017)

- Establishment (of a pest)

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2017)

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2017)

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2017)

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2017)

- Protected zones (PZ)

A protected zone is an area recognised at EU level to be free from a harmful organism, which is established in one or more other parts of the Union

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP)

A non‐quarantine pest whose presence in plants for planting affects the intended use of those plants with an economically unacceptable impact and which is therefore regulated within the territory of the importing contracting party (FAO, 2017)

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO 2017)

- Supporting measures+

Organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate Risk Reduction Options that do not directly affect pest abundance

Appendix A – Conotrachelus nenuphar host plants

1.

Data compiled from EPPO and CABI databases (accessed 13/7/2018). Hosts regarded as main hosts by EPPO or CABI are highlighted.

| Plant name | Common name | Plant family |

|---|---|---|

| Hemerocallis | Day lily | Asphodelaceae |

| Hemerocallis lilioasphodelus | Lemon day lily | Asphodelaceae |

| Diospyros kaki | Persimmon | Ebenaceae |

| Vaccinium | Blueberries | Ericaceae |

| Vaccinium corymbosum | Blueberry | Ericaceae |

| Vaccinium stamineum | Common deerberry | Ericaceae |

| Ribes | Currants | Grossulariaceae |

| Ribes uva‐crispa | Gooseberry | Grossulariaceae |

| Amelanchier arborea | Downy serviceberry | Rosaceae |

| Amelanchier canadensis | Canadese krenteboompje | Rosaceae |

| Crataegus | Hawthorn | Rosaceae |

| Cydonia oblonga | Quince | Rosaceae |

| Fragaria ananassa | Strawberry | Rosaceae |

| Malus | Apple | Rosaceae |

| Malus domestica | Apple | Rosaceae |

| Prunus | Stone fruit | Rosaceae |

| Prunus alleghaniensis | Allegheny plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus americana | American plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus armeniaca | Apricot | Rosaceae |

| Prunus avium | Sweet cherry | Rosaceae |

| Prunus cerasus | Sour cherry | Rosaceae |

| Prunus domestica | Plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus japonica | Japanese bush cherry tree | Rosaceae |

| Prunus maritima | Beach plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus mexicana | Mexican plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus nigra | Canada plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus pensylvanica | Pin cherry | Rosaceae |

| Prunus persica | Peach | Rosaceae |

| Prunus pumila | Dwarf American cherry | Rosaceae |

| Prunus salicina | Japanese plum | Rosaceae |

| Prunus serotina | Black cherry | Rosaceae |

| Prunus virginiana | Common chokecherry | Rosaceae |

| Pyrus | Pears | Rosaceae |

| Pyrus communis | European pear | Rosaceae |

| Sorbus aucuparia | Common mountain ash | Rosaceae |

| Vitis rotundifolia | Muscadine grape | Vitaceae |

| Vitis vinifera | Grapevine | Vitaceae |

Appendix B – Harvested area of key C. nenuphar Prunus hosts in individual EU Member States

1.

Source: Eurostat (accessed on 13/7/2018)

Peaches (Prunus persica)

| Country/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bulgaria | 3.80 | 2.87 | 3.55 | 3.66 | 3.73 |

| Czech Republic | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Denmark | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Germany | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| Estonia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ireland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greece | 38.24 | 39.14 | 36.52 | 33.47 | 33.52 |

| Spain | 51.51 | 50.75 | 51.46 | 52.88 | 52.14 |

| France | 5.36 | 5.30 | 5.09 | 4.83 | 4.80 |

| Croatia | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| Italy | 49.65 | 48.06 | 46.25 | 47.03 | 45.49 |

| Cyprus | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Latvia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lithuania | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Luxembourg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Hungary | 5.37 | 5.44 | 5.41 | 5.41 | 5.42 |

| Malta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Netherlands | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Austria | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Poland | 2.60 | : | 2.40 | 2.23 | : |

| Portugal | 2.77 | 2.74 | 2.85 | 2.94 | 2.97 |

| Romania | 1.93 | 1.68 | 1.69 | 1.68 | 1.62 |

| Slovenia | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Slovakia | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.32 |

| Finland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sweden | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| United Kingdom | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

‘:’ data not available.

Apricots (Prunus armeniaca)

| Country/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bulgaria | 2.33 | 1.74 | 2.48 | 2.55 | 2.90 |

| Czech Republic | 1.20 | 1.21 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.10 |

| Denmark | 0.00 | : | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Germany | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| Estonia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ireland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greece | 6.56 | 7.27 | 7.45 | 7.33 | 7.65 |

| Spain | 20.33 | 18.45 | 18.82 | 20.35 | 21.00 |

| France | 12.18 | 12.21 | 11.99 | 12.18 | 12.20 |

| Croatia | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.28 | : |

| Italy | 17.54 | 17.63 | 17.19 | 18.92 | 17.36 |

| Cyprus | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Latvia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lithuania | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Luxembourg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Hungary | 4.44 | 4.57 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.91 |

| Malta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Netherlands | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Austria | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Poland | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.10 | 0.99 | : |

| Portugal | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| Romania | 2.84 | 2.98 | 2.62 | 2.20 | 2.10 |

| Slovenia | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Slovakia | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| Finland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sweden | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| United Kingdom | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

‘:’ data not available.

Cherries (accessed on 13/7/2018) divided by Member States

| Country/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 1,189.00 | 1.27 | 1.31 | 1.32 | 1.40 |

| Bulgaria | 9.05 | 7.21 | 9.26 | 9.60 | 10.06 |

| Czech Republic | 2.54 | 2.45 | 2.28 | 2.19 | 2.11 |

| Denmark | 1.33 | 1.22 | 1.14 | 0.79 | 0.66 |

| Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) | 7.42 | 7.36 | 7.21 | 7.14 | 7.96 |

| Estonia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Ireland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greece | 11.88 | 13.60 | 14.63 | 15.57 | 15.32 |

| Spain | 25.36 | 25.59 | 26.49 | 26.95 | 27.59 |

| France | 8.26 | 8.22 | 8.15 | 8.14 | 8.01 |

| Croatia | 3.20 | 3.55 | 3.35 | 3.43 | : |

| Italy | 29.73 | 28.97 | 29.25 | 29.97 | 29.27 |

| Cyprus | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| Latvia | : | : | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Lithuania | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| Luxembourg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Hungary | 16.38 | 16.06 | 15.64 | 15.64 | 15.49 |

| Malta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Netherlands | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Austria | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Poland | 38.00 | 38.60 | 39.10 | 36.81 | : |

| Portugal | 6.10 | 6.12 | 6.37 | 6.43 | 6.30 |

| Romania | 7.08 | 6.45 | 6.31 | 6.13 | 6.08 |

| Slovenia | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| Slovakia | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Finland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sweden | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| United Kingdom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

‘:’ data not available.

Plums (accessed on 13/7/2018) divided by Member States

| Country/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Bulgaria | 5.89 | 4.88 | 6.83 | 6.71 | 6.82 |

| Czech Republic | 1.92 | 1.91 | 1.87 | 1.88 | 1.76 |

| Denmark | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Germany | 4.35 | 4.35 | 4.34 | 4.35 | 4.83 |

| Estonia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Ireland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greece | 1.57 | 1.81 | 2.05 | 2.60 | 2.08 |

| Spain | 16.61 | 17.00 | 16.06 | 15.28 | 15.20 |

| France | 16.95 | 16.05 | 14.97 | 14.81 | 15.06 |

| Croatia | 4.80 | 4.85 | 5.12 | 4.83 | : |

| Italy | 12.41 | 12.27 | 11.63 | 11.57 | 11.68 |

| Cyprus | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Latvia | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Lithuania | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| Luxembourg | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Hungary | 7.66 | 7.36 | 7.22 | 7.22 | 7.98 |

| Malta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Netherlands | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| Austria | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| Poland | 16.50 | 15.30 | 13.90 | 13.39 | : |

| Portugal | 1.68 | 1.69 | 1.79 | 1.80 | 1.78 |

| Romania | 68.01 | 66.55 | 65.67 | 65.11 | 65.67 |

| Slovenia | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Slovakia | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.52 |

| Finland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sweden | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| United Kingdom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.60 |

‘:’ data not available.

Suggested citation: EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Plant Health Panel) , Bragard C, Dehnen‐Schmutz K, Di Serio F, Gonthier P, Jacques M‐A, Jaques Miret JA, Justesen AF, Magnusson CS, Milonas P, Navas‐Cortes JA, Parnell S, Potting R, Reignault PL, Thulke HH, Van der Werf W, Vicent Civera A, Yuen J, Zappalà L, Czwienczek E and MacLeod A, 2018. Scientific opinion on the pest categorisation of Conotrachelus nenuphar . EFSA Journal 2018;16(10):5437, 29 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5437

Requestor: European Commission

Question number: EFSA‐Q‐2018‐00025

Panel members: Claude Bragard, Katharina Dehnen‐Schmutz, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Marie‐Agnès Jacques, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Panagiotis Milonas, Juan A Navas‐Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Philippe Lucien Reignault, Hans‐Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen and Lucia Zappalà.

Adopted: 27 September 2018

Reproduction of the images listed below is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder:

Figure 1: © EPPO

Notes

Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community. OJ L 169/1, 10.7.2000, p. 1–112.

Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament of the Council of 26 October 2016 on protective measures against pests of plants. OJ L 317, 23.11.2016, p. 4–104.

Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. OJ L 31/1, 1.2.2002, p. 1–24.

See Section 2.1 on what falls outside EFSA's remit.

References

- Akotsen‐Mensah C, 2010. Ecology and Management of Plum Curculio, Conotrachelus nenuphar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Alabama Peaches. PhD thesis, Auburn University, Alabama August 9, 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266578531_Ecology_and_Management_of_Plum_Curculio_Conotrachelus_nenuphar_Coleoptera_Curculionidae_in_Alabama_Peaches [Accessed: 22 July 2018]

- Akotsen‐Mensah C, Boozer RT, Appel AG and Fadamiro HY, 2011. Seasonal occurrence and development of degree‐day models for predicting activity of Conotrachelus nenuphar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Alabama Peaches. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 104, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Alston DG and Stark A, 2003. Plum curculio biology, host range, distribution, and control in Utah Final Report. Department of Biology, Utah State University (USU). Available online: http://jenny.tfrec.wsu.edu/wtfrc/PDFfinalReports/2003FinalReports/AppleEntomology/Alston2000.pdf [Accessed: 27 July 2018]

- Alston DG, Rangel DEN, Lacey LA, Golez HG, Kim JJ and Roberts DW, 2005. Evaluation of novel fungal and nematode isolates for control of Conotrachelus nenuphar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) larvae. Biological Control, 35, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T, 1958. Life history and ecology of the plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar Hbst. [Coleoptera: Curculionidae]) in the Niagara peninsula, Ontario. Canadian Entomologist, 90, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett RH, 1971. The beetles of the United States (A manual for identification). The American Entomological Institute, Ann Arbor, MI. 1112 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Bosik JJ, 1997. Common names of insects and related organisms. Entomological Society of America, Committee on common names of insects: 232 pp. [Google Scholar]

- CABI , 2018. Conotrachelus nenuphar (plum curculio). CABI Invasive Species Compendium. Datasheet last modified 28 March 2018. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/ISC/AppError/Index?aspxerrorpath=/isc/datasheet/15164 [Accessed: 28 July 2018]

- Campbell JM, Sarazin MJ and Lyons DB. 1989. Canadian beetles (Coleoptera) injurious to crops, ornamentals, stored products, and buildings. Agriculture Canada Publication 1826, Canadian Government Publishing centre, Ottawa, 491 pp.

- Chen H, Kaufmann C and Scherm H, 2006. Laboratory evaluation of flight performance of the plum curculio (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 99, 2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]