Abstract

The Panel on Plant Health performed a pest categorisation of Aleurocanthus spp., a well‐defined insect genus of the whitefly family Aleyrodidae (Arthropoda: Hemiptera). Difficulties within the taxonomy of the genus give doubt about the ability to accurately identify some members to species level. Nevertheless, the genus is thought to currently include about ninety species mainly reported from tropical and subtropical areas. The genus is listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC and is regulated on Citrus, Fortunella and Poncirus. Several Aleurocanthus species are highly polyphagous; Aleurocanthus spiniferus has hosts in 38 plant families; Aleurocanthus woglumi has more than 300 hosts including Pyrus, Rosa and Vitis vinifera as well as Citrus. A. spiniferus is present in the EU in restricted areas of Italy and Greece, where it is under official control. No other Aleurocanthus spp. are known to occur in the EU. Host plants for planting, excluding seeds, and cut flowers or branches are the main pathways for entry. Outside of the EU, the genus can be found in regions that have climate types which also occur within the EU, suggesting establishment is possible. Aleurocanthus spp. can be significant pests of crops that are also grown in the EU. Phytosanitary measures are available to reduce the likelihood of entry into the EU, e.g. sourcing host plants for planting from pest free areas. As a genus Aleurocanthus does satisfy all the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess and required by risk managers to give it consideration as a Union quarantine pest. Aleurocanthus does not meet all of the criteria to allow it consideration by risk managers as a Union regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP). Specifically, Aleurocanthus is not widespread in the EU.

Keywords: European Union, pest risk, plant health, polyphenic species, plant pest, taxonomy

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

Council Directive 2000/29/EC1 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community establishes the present European Union plant health regime. The Directive lays down the phytosanitary provisions and the control checks to be carried out at the place of origin on plants and plant products destined for the Union or to be moved within the Union. In the Directive's 2000/29/EC annexes, the list of harmful organisms (pests) whose introduction into or spread within the Union is prohibited, is detailed together with specific requirements for import or internal movement.

Following the evaluation of the plant health regime, the new basic plant health law, Regulation (EU) 2016/20312 on protective measures against pests of plants, was adopted on 26 October 2016 and will apply from 14 December 2019 onwards, repealing Directive 2000/29/EC. In line with the principles of the above mentioned legislation and the follow‐up work of the secondary legislation for the listing of EU regulated pests, EFSA is requested to provide pest categorisations of the harmful organisms included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC, in the cases where recent pest risk assessment/pest categorisation is not available.

1.1.2. Terms of reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 22(5.b) and Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002,3 to provide scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to prepare and deliver a pest categorisation (step 1 analysis) for each of the regulated pests included in the appendices of the annex to this mandate. The methodology and template of pest categorisation have already been developed in past mandates for the organisms listed in Annex II Part A Section II of Directive 2000/29/EC. The same methodology and outcome is expected for this work as well.

The list of the harmful organisms included in the annex to this mandate comprises 133 harmful organisms or groups. A pest categorisation is expected for these 133 pests or groups and the delivery of the work would be stepwise at regular intervals through the year as detailed below. First priority covers the harmful organisms included in Appendix 1, comprising pests from Annex II Part A Section I and Annex II Part B of Directive 2000/29/EC. The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 1 is June 2018. The second priority is the pests included in Appendix 2, comprising the group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), the group of Tephritidae (non‐EU), the group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms, the group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L.. and the group of Margarodes (non‐EU species). The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 2 is end 2019. The pests included in Appendix 3 cover pests of Annex I part A section I and all pests categorisations should be delivered by end 2020.

For the above mentioned groups, each covering a large number of pests, the pest categorisation will be performed for the group and not the individual harmful organisms listed under “such as” notation in the Annexes of the Directive 2000/29/EC. The criteria to be taken particularly under consideration for these cases, is the analysis of host pest combination, investigation of pathways, the damages occurring and the relevant impact.

Finally, as indicated in the text above, all references to ‘non‐European’ should be avoided and replaced by ‘non‐EU’ and refer to all territories with exception of the Union territories as defined in Article 1 point 3 of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031.

1.1.2.1. Terms of Reference: Appendix 1

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Aleurocantus spp. | Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) |

| Anthonomus bisignifer (Schenkling) | Oligonychus perditus Pritchard and Baker |

| Anthonomus signatus (Say) | Pissodes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Aschistonyx eppoi Inouye | Scirtothrips aurantii Faure |

| Carposina niponensis Walsingham | Scirtothrips citri (Moultex) |

| Enarmonia packardi (Zeller) | Scolytidae spp. (non‐EU) |

| Enarmonia prunivora Walsh | Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny |

| Grapholita inopinata Heinrich | Tachypterellus quadrigibbus Say |

| Hishomonus phycitis | Toxoptera citricida Kirk. |

| Leucaspis japonica Ckll. | Unaspis citri Comstock |

| Listronotus bonariensis (Kuschel) | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Citrus variegated chlorosis | Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae (Ishiyama) Dye and pv. oryzicola (Fang. et al.) Dye |

| Erwinia stewartii (Smith) Dye | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler (non‐EU pathogenic isolates) | Elsinoe spp. Bitanc. and Jenk. Mendes |

| Anisogramma anomala (Peck) E. Müller | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Kilian and Maire) Gordon |

| Apiosporina morbosa (Schwein.) v. Arx | Guignardia piricola (Nosa) Yamamoto |

| Ceratocystis virescens (Davidson) Moreau | Puccinia pittieriana Hennings |

| Cercoseptoria pini‐densiflorae (Hori and Nambu) Deighton | Stegophora ulmea (Schweinitz: Fries) Sydow & Sydow |

| Cercospora angolensis Carv. and Mendes | Venturia nashicola Tanaka and Yamamoto |

| (d) Virus and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet curly top virus (non‐EU isolates) | Little cherry pathogen (non‐ EU isolates) |

| Black raspberry latent virus | Naturally spreading psorosis |

| Blight and blight‐like | Palm lethal yellowing mycoplasm |

| Cadang‐Cadang viroid | Satsuma dwarf virus |

| Citrus tristeza virus (non‐EU isolates) | Tatter leaf virus |

| Leprosis | Witches’ broom (MLO) |

| Annex IIB | |

| (a) Insect mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Anthonomus grandis (Boh.) | Gonipterus scutellatus Gyll. |

| Cephalcia lariciphila (Klug) | Ips amitinus Eichhof |

| Dendroctonus micans Kugelan | Ips cembrae Heer |

| Gilphinia hercyniae (Hartig) | Ips duplicatus Sahlberg |

| Ips sexdentatus Börner | Sternochetus mangiferae Fabricius |

| Ips typographus Heer | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens (Hedges) Collins and Jones | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Glomerella gossypii Edgerton | Hypoxylon mammatum (Wahl.) J. Miller |

| Gremmeniella abietina (Lag.) Morelet | |

1.1.2.2. Terms of Reference: Appendix 2

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested per group. The list below follows the categorisation included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), such as: | |

| 1) Carneocephala fulgida Nottingham | 3) Graphocephala atropunctata (Signoret) |

| 2) Draeculacephala minerva Ball | |

| Group of Tephritidae (non‐EU) such as: | |

| 1) Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) | 12) Pardalaspis cyanescens Bezzi |

| 2) Anastrepha ludens (Loew) | 13) Pardalaspis quinaria Bezzi |

| 3) Anastrepha obliqua Macquart | 14) Pterandrus rosa (Karsch) |

| 4) Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) | 15) Rhacochlaena japonica Ito |

| 5) Dacus ciliatus Loew | 16) Rhagoletis completa Cresson |

| 6) Dacus curcurbitae Coquillet | 17) Rhagoletis fausta (Osten‐Sacken) |

| 7) Dacus dorsalis Hendel | 18) Rhagoletis indifferens Curran |

| 8) Dacus tryoni (Froggatt) | 19) Rhagoletis mendax Curran |

| 9) Dacus tsuneonis Miyake | 20) Rhagoletis pomonella Walsh |

| 10) Dacus zonatus Saund. | 21) Rhagoletis suavis (Loew) |

| 11) Epochra canadensis (Loew) | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms such as: | |

| 1) Andean potato latent virus | 4) Potato black ringspot virus |

| 2) Andean potato mottle virus | 5) Potato virus T |

| 3) Arracacha virus B, oca strain | 6) non‐EU isolates of potato viruses A, M, S, V, X and Y (including Yo, Yn and Yc) and Potato leafroll virus |

| Group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L.,Rubus L. and Vitis L., such as: | |

| 1) Blueberry leaf mottle virus | 8) Peach yellows mycoplasm |

| 2) Cherry rasp leaf virus (American) | 9) Plum line pattern virus (American) |

| 3) Peach mosaic virus (American) | 10) Raspberry leaf curl virus (American) |

| 4) Peach phony rickettsia | 11) Strawberry witches’ broom mycoplasma |

| 5) Peach rosette mosaic virus | 12) Non‐EU viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. |

| 6) Peach rosette mycoplasm | |

| 7) Peach X‐disease mycoplasm | |

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Margarodes (non‐EU species) such as: | |

| 1) Margarodes vitis (Phillipi) | 3) Margarodes prieskaensis Jakubski |

| 2) Margarodes vredendalensis de Klerk | |

1.1.2.3. Terms of Reference: Appendix 3

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Acleris spp. (non‐EU) | Longidorus diadecturus Eveleigh and Allen |

| Amauromyza maculosa (Malloch) | Monochamus spp. (non‐EU) |

| Anomala orientalis Waterhouse | Myndus crudus Van Duzee |

| Arrhenodes minutus Drury | Nacobbus aberrans (Thorne) Thorne and Allen |

| Choristoneura spp. (non‐EU) | Naupactus leucoloma Boheman |

| Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) | Premnotrypes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetverikov | Pseudopityophthorus minutissimus (Zimmermann) |

| Diabrotica barberi Smith and Lawrence | Pseudopityophthorus pruinosus (Eichhoff) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber | Scaphoideus luteolus (Van Duzee) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Mannerheim | Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) |

| Diabrotica virgifera zeae Krysan & Smith | Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) |

| Diaphorina citri Kuway | Spodoptera litura (Fabricus) |

| Heliothis zea (Boddie) | Thrips palmi Karny |

| Hirschmanniella spp., other than Hirschmanniella gracilis (de Man) Luc and Goodey | Xiphinema americanum Cobb sensu lato (non‐EU populations) |

| Liriomyza sativae Blanchard | Xiphinema californicum Lamberti and Bleve‐Zacheo |

| (b) Fungi | |

| Ceratocystis fagacearum (Bretz) Hunt | Mycosphaerella larici‐leptolepis Ito et al. |

| Chrysomyxa arctostaphyli Dietel | Mycosphaerella populorum G. E. Thompson |

| Cronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phoma andina Turkensteen |

| Endocronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phyllosticta solitaria Ell. and Ev. |

| Guignardia laricina (Saw.) Yamamoto and Ito | Septoria lycopersici Speg. var. malagutii Ciccarone and Boerema |

| Gymnosporangium spp. (non‐EU) | Thecaphora solani Barrus |

| Inonotus weirii (Murril) Kotlaba and Pouzar | Trechispora brinkmannii (Bresad.) Rogers |

| Melampsora farlowii (Arthur) Davis | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Tobacco ringspot virus | Pepper mild tigré virus |

| Tomato ringspot virus | Squash leaf curl virus |

| Bean golden mosaic virus | Euphorbia mosaic virus |

| Cowpea mild mottle virus | Florida tomato virus |

| Lettuce infectious yellows virus | |

| (d) Parasitic plants | |

| Arceuthobium spp. (non‐EU) | |

| Annex IAII | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Meloidogyne fallax Karssen | Popillia japonica Newman |

| Rhizoecus hibisci Kawai and Takagi | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Clavibacter michiganensis (Smith) Davis et al. ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al. | Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith) Yabuuchi et al. |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Melampsora medusae Thümen | Synchytrium endobioticum (Schilbersky) Percival |

| Annex IB | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say | Liriomyza bryoniae (Kaltenbach) |

| (b) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet necrotic yellow vein virus | |

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

Aleurocanthus spp. is listed in the Appendices to the Terms of Reference (ToR) to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of being a quarantine pest or a regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) for the area of the EU excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States (MS) referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores. For the purposes of this pest categorisation, the Panel categorises the genus as a whole rather than categorising the individual species within it.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Literature search

A literature search on Aleurocanthus was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name of the genus as a search term. Relevant papers were reviewed and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.2. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plan Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, 2018a) and relevant publications.

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Communities).

The Europhyt database was consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission and is a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. The Europhyt database manages notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the MS and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread.

The database on Arthropod Ecology, Molecular Identification and Systematics (Artemis database) hosts a dense diversity of arthropod species that are pests of different cultures throughout the world, as well as their natural enemies. The database contains DNA sequences (barcodes) to provide a reliable identification tool for all developmental stages of the target species. Arthemis also hosts information about the distribution of the sequenced species, their biology and ecology as well as taxonomic information (synonyms, etc.) and pictures. Aleyrodidae is one of the main target groups in Arthemis.

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for Aleurocanthus spp., following guiding principles and steps presented in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures No 11 (FAO, 2013) and No 21 (FAO, 2004) and EFSA PLH Panel (2018).

In accordance with the guidance on pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018), this work was initiated following an evaluation of the EU plant health regime. Therefore, to facilitate the decision‐making process, in the conclusions of the pest categorisation, the Panel addresses explicitly each criterion for a Union quarantine pest and for a Union RNQP in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants, and includes additional information required in accordance with the specific terms of reference received by the European Commission. In addition, for each conclusion, the Panel provides a short description of its associated uncertainty.

Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. All relevant criteria have to be met for the pest to potentially qualify either as a quarantine pest or as a RNQP. If one of the criteria is not met, the pest will not qualify. A pest that does not qualify as a quarantine pest may still qualify as a RNQP that needs to be addressed in the opinion. For the pests regulated in the protected zones only, the scope of the categorisation is the territory of the protected zone; thus, the criteria refer to the protected zone instead of the EU territory.

Table 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding protected zone quarantine pest (articles 32–35) | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU? Describe the pest distribution briefly! |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a protected zone quarantine organism | Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a regulated non‐quarantine pest. (A regulated non‐quarantine pest must be present in the risk assessment area) |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3 ) | If the pest is present in the EU but not widely distributed in the risk assessment area, it should be under official control or expected to be under official control in the near future |

The protected zone system aligns with the pest free area system under the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) The pest satisfies the IPPC definition of a quarantine pest that is not present in the risk assessment area (i.e. protected zone) |

Is the pest regulated as a quarantine pest? If currently regulated as a quarantine pest, are there grounds to consider its status could be revoked? |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways! |

Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the protected zone areas? Is entry by natural spread from EU areas where the pest is present possible? |

Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects? Clearly state if plants for planting is the main pathway! |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the protected zone areas? | Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the protected zone areas such that the risk becomes mitigated? Is it possible to eradicate the pest in a restricted area within 24 months (or a period longer than 24 months where the biology of the organism so justifies) after the presence of the pest was confirmed in the protected zone? |

Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4 ) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as potential protected zone quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met |

It should be noted that the Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, the Panel will present a summary of the observed pest impacts. Economic impacts are expressed in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, whereas addressing social impacts is outside the remit of the Panel.

The Panel will not indicate in its conclusions of the pest categorisation whether to continue the risk assessment process, but following the agreed two‐step approach, will continue only if requested by the risk managers. However, during the categorisation process, experts may identify key elements and knowledge gaps that could contribute significant uncertainty to a future assessment of risk. It would be useful to identify and highlight such gaps so that potential future requests can specifically target the major elements of uncertainty, perhaps suggesting specific scenarios to examine.

3. Pest categorisation

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible?

Yes, the genus Aleurocanthus is a valid genus with about 90 species recorded some of which are important plant pests.

Aleurocanthus Quaintance & Baker 1914 is an insect genus in the family Aleyrodidae (Arthropoda: Hemiptera), containing several whitefly species differing in biology, climatic requirements and distribution. The genus is clearly identifiable but there is great difficulty in identifying and distinguishing some members within the genus giving rise to uncertainty of the identity of individuals when they are found. The genus comprises of polyphenic species, i.e. the same species may express different character states when found on different hosts. The total number of Aleurocanthus species recorded varies according to the data source: 82 are reported in Evans (2017); 79 in Ouvrard and Martin (2018) (accessed 19/4/2018); 78 in Martin and Mound (2007) and 93 in the Arthemis database (accessed 4/6/2018). Differences in numbers are essentially due to species now considered invalid, which creates synonymies and to the description of new species.

Martin and Mound (2007) provides the most recent worldwide list of Aleyrodidae; it lists 78 species in the Aleurocanthus genus. Among these, eight species (10%) were described between 2000 and 2007. Gillespie (2012) described 11 new species from Australia; Dubey and Ko (2012) one species from Taiwan; Kanmiya et al. (2011) identified a new species in Japan; Martin and Lau (2011) proposed to move Aleurocanthus cheni as a synonym of Aleurocanthus spiniferus. The list of Aleyrodidae of Hong Kong (Martin and Lau, 2011) noted three unidentified species of Aleurocanthus, two of them close to A. woglumi. This constant reorganisation of the Aleurocanthus taxonomy, including synonymies or description of new species, suggests that many species remain to be identified, even by the world's best specialists on this group. As an example, A. spiniferus was recognised as a citrus pest in Japan while it was also thought to damage tea plants (Camellia sinensis) in temperate China. Han and Cui (2003) reviewed several prominent outbreaks said to involve A. spiniferus in the main tea regions of China since the 1960s. A close study of the tea‐infesting population gave a new scientific name, Aleurocanthus camelliae Kanmiya & Kasai sp. nov., and a new common name, camellia spiny whitefly, thus distinguishing it from A. spiniferus which represents the citrus‐infesting population (Kanmiya et al., 2011).

In general, Aleurocanthus remains a poorly known genus. Its systematics is currently based almost entirely on the morphology of the puparia. This situation has arisen in part because the morphological characters of the derm, the external surface of the vacated puparium (often described as a ‘pupal case’), which are observed under microscope for species identification, appear insufficient in some cases (Martin et al., 2000).

Among the 93 Aleurocanthus species listed in Arthemis, the most up to date database on whiteflies, 10 are reported as having some impact on crops, according to results of searches performed by the PLH panel in WOS and Google Scholar databases (accessed 18/5/2018) and are listed in Appendix A. Five of them occur on citrus. From these, two are significant pests widely distributed and the best documented Aleurocanthus species: A. woglumi and A. spiniferus. These are also known by the common names of ‘Citrus blackfly’ and ‘Orange/Citrus spiny whitefly’, respectively. Indeed, from the 2,400 records found in Google Scholar in a search performed by the PLH panel (accession 18/5/2018) using the search terms ‘economic’ and ‘Aleurocanthus’, 1,120 corresponded to A. woglumi and 1,110 to A. spiniferus.

Among the other Aleurocanthus species reported as having economic impact on citrus, the most important are A. citriperdus, in India and Pakistan, and A. husaini in India (David, 2012). Morphologically, these species differ from each other only by microscopic characters of the puparium and require expert preparation and identification to distinguish them reliably (CABI, 2018).

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

All species in the genus Aleurocanthus have three developmental stages (egg, nymph and adult), with the nymphal stage presenting four instars: first mobile instar, two sessile instars (second and third instars) and pupa (fourth instar). Adults are winged. The duration of the life cycle and the number of generations per year are greatly influenced by the prevailing climate (Gyeltshen et al., 2017). Some aleyrodids have more than one generation per year and in tropical and subtropical climates continuous overlapping generations may occur with slowed development during short, cold periods (Hodges and Evans, 2005). About four generations per year have been recorded for A. spiniferus in Japan while two to three generations per year are reported in India (David, 2012), and as many as seven generations occurred under ideal laboratory conditions (Gyeltshen and Hodges, 2010). A. camelliae voltinism varies from two to five generations in the major tea‐producing districts of Japan (Kasai et al., 2012; Yamashita et al., 2016).

Temperature requirements of the different species within the genus are expected to vary according to their geographical distributions, but information of biology of Aleurocanthus is manly based on two species, A. spiniferus and A. woglumi.

The following details are based on EPPO (2017) and CABI (2018) data sheets, and references therein. In tropical conditions, all stages of A. woglumi may be found throughout the year, but reproduction stops during cold periods. Eggs are laid in a characteristic spiral on the underside of young leaves in batches of 35–50 and hatch in 4–12 days depending on conditions. The first instars are active and disperse over a short distance, avoiding strong sunlight and usually settling in a dense colony of up to several hundred on the undersides of young leaves to feed on phloem sap. Functional legs are lost in the subsequent moult, and the next three immature instars are attached to the leaf by their mouthparts. All stages (except a resting phase in the fourth instar or ‘pupa’) feed on phloem sap. Each female may lay more than 100 eggs in her lifetime. CABI (2018) mentions that the life cycle takes 2–4 months depending on conditions, and there are three to six generations per year; development times of different stages are reported as: egg 11–20 days; larval instars 7–16, 5–30 and 6–20 days, respectively; ‘pupa’ 16–80 days; adult 6–12 days. Preimaginal mortality of A. woglumi is high; Dietz and Zetek (1920) recorded a level of 77.5% in Panama. The optimal conditions for development are 28–32°C and 70–80% relative humidity. A. woglumi does not survive temperatures below freezing and does not occur in areas where temperatures exceed 43°C. Dowell and Fitzpatrick (1978) give a lower threshold for development for A. woglumi of 13.7°C.

The biology of A. spiniferus is essentially similar to that of A. woglumi. Eggs are laid in a characteristic spiral on the underside of young leaved in batches of 35–50 and hatch in 4–12 days depending on conditions (CABI, 2018). The pest is most likely to be found on leaves. Infested leaves are mainly found on the lower parts of the trees (EPPO, 2017).

A. spiniferus and A. woglumi both occur on citrus in Kenya where they seem to have different ecological preferences, with A. spiniferus being dominant at higher altitudes and A. woglumi at lower altitudes. Also, A. woglumi does not occur in Korea, whereas A. spiniferus does. This may reflect less tolerance to low temperatures in A. woglumii relative to A. spiniferus (CABI, 2018).

Biological data for other Aleurocanthus species are less abundant. The Panel assumes that the other species within the genus have broadly similar biological requirements.

Over 100 virus species are transmitted by whiteflies (Jones, 2003). However, none of the species of Aleurocanthus are known for being vectors. The absence of reports of Aleurocantus spp. as plant virus vectors was confirmed by the results obtained during the literature searches performed for this pest categorisation.

3.1.3. Intraspecific diversity

As noted in Section 3.1.1, the taxonomy of the genus is not resolved. Some members of the genus have not been formally described or named. We found no reports on intraspecific diversity of Aleurocanthus spp. Molecular evidence for multiple phylogenetic groups within A. spiniferus and A. camelliae has been reported (Uesugi et al., 2016); however, no associations to variable biological features were informed.

3.1.4. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, detection is possible using standard techniques in entomology, e.g. yellow sticky traps to capture adults.

There are keys available for the identification at the genus level. Species identification is extremely difficult and identity not established for all Aleurocanthus spp.

There is no reference covering the identification of all Aleurocanthus spp. worldwide. Identification to the genus level is possible based on puparia morphology. A description of morphological characters to observe in slide mounted specimens can be found in Martin (1987). Species identification can be complicated. Authoritative identification of Aleurocanthus spp. involves detailed microscopic study of external puparial morphology by a whitefly specialist (CABI, 2018).

A report on Aleurocanthus species in Taiwan showed the importance of studying sex‐related dimorphism, the intraspecific variation of characters and the influence of the preparation technique on the interpretation of morphological characters, which illustrates the general complexity of the genus (Dubey and Ko, 2012).

Because of the particular A. spiniferus adults black colour, it is relatively easy to detect its presence in the field (El Kenawy et al., 2014); however, entomological expertise would be needed for the identification of immature stages (including the puparium of the pupa, the last immature stage).

The first report of A. spiniferus in Italy dates from 2008 (Porcelli, 2008); interviews with local citrus growers revealed that the pest, while noted, remained misidentified as a scale insect for at least two years (Porcelli, 2008). A. spiniferus can be confused with many other Aleurocanthus species. Adults of the two major Aleurocanthus pests, A. spiniferus and A. woglumi, cannot be easily distinguished (Gyeltshen et al., 2017). The morphological characters of the pupal case that are used to recognise Aleurocanthus spp. are very similar in appearance for these two species (Martin, 1987). A mixture of several whiteflies, including these two species, is frequently found in the same field in South Africa (Bedford et al., 1998), which complicates correct species identification.

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

Aleurocanthus species are widespread mainly in tropical and subtropical areas (Africa, America, Asia, Oceania). Several of the currently recognised Aleurocanthus species are associated with crops, but only a few are considered to have significant economic impact (Appendix A).

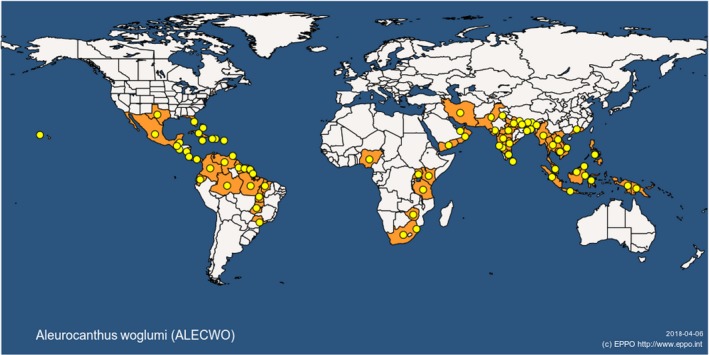

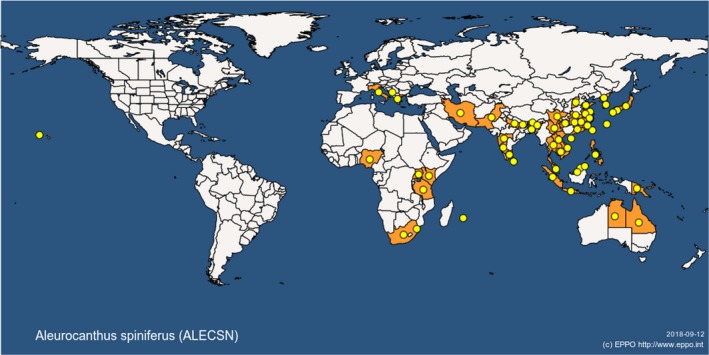

The distribution of A. spiniferus and A. woglumi, which are the most widely distributed and amongst the most economically important species, is reported in Table 2 and illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of Aleurocanthus woglumi and A. spiniferus, two of the most well‐known members of the genus. Data from: EPPO GD and CABI CPC, accessed on 6.4.2018

| Continent | Country | State/region | A. spiniferus | A. woglumi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Kenya | X | X | |

| Mauritius | X | |||

| Nigeria | X | X | ||

| Reunion | X | |||

| Seychelles | X | |||

| South Africa | X | X | ||

| Swaziland | X | X | ||

| Tanzania | X | X | ||

| Uganda | X | X | ||

| Zimbabwe | X | |||

| America | Antigua and Barbuda | X | ||

| Bahamas | X | |||

| Barbados | X | |||

| Belize | X | |||

| Bermuda | X | |||

| Brazil | Amapa | X | ||

| Amazonas | X | |||

| Goias | X | |||

| Maranhao | X | |||

| Para | X | |||

| Sao Paolo | X | |||

| Tocantins | X | |||

| Cayman Islands | X | |||

| Colombia | X | |||

| Costa Rica | X | |||

| Cuba | X | |||

| Dominica | X | |||

| Dominican Republic | X | |||

| Ecuador | X | |||

| El Salvador | X | |||

| French Guiana | X | |||

| Guadeloupe | X | |||

| Guatemala | X | |||

| Guyana | X | |||

| Haiti | X | |||

| Jamaica | X | |||

| Mexico | X | |||

| Netherlands Antilles | X | |||

| Nicaragua | X | |||

| Panama | X | |||

| Puerto Rico | X | |||

| Saint Lucia | X | |||

| St Kitts‐Nevis | X | |||

| Suriname | X | |||

| Trinidad and Tobago | X | |||

| USA | Florida | X | ||

| Hawaii | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | |||

| Venezuela | X | |||

| Virgin Islands (British) | X | |||

| Asia | Bangladesh | X | X | |

| Bhutan | X | X | ||

| Brunei Darussalam | X | |||

| Cambodia | X | X | ||

| China | Anhui | X | ||

| Aomen (Macau) | X | |||

| Fujian | X | |||

| Guangdong | X | X | ||

| Guizhou | X | |||

| Hainan | X | |||

| Hubei | X | |||

| Hunan | X | |||

| Jiangsu | X | |||

| Jianxi | X | |||

| Shandong | X | |||

| Shanxi | X | |||

| Sichuan | X | |||

| Xianggang (Hong Kong) | X | X | ||

| Yunnan | X | |||

| Zhejiang | X | |||

| Hong Kong | ||||

| India | Andhra Pradesh | X | ||

| Assam | X | X | ||

| Bihar | X | X | ||

| Delhi | X | |||

| Goa | X | |||

| Gujarat | X | |||

| Karnataka | X | X | ||

| Madhya Pradesh | X | |||

| Maharashtra | X | X | ||

| Punjab | X | |||

| Sikkim | X | |||

| Tamil Nadu | X | X | ||

| Uttar Pradesh | X | X | ||

| West Bengal | X | |||

| Indonesia | Irian Jaya | X | ||

| Java | X | X | ||

| Kalimantan | X | |||

| Sulawesi | X | |||

| Sumatra | X | X | ||

| Iran | X | X | ||

| Japana | Honshu | X | ||

| Kyushu | X | |||

| Ryukyu Archipelago | X | |||

| Shikoku | X | |||

| DPR of Korea | X | |||

| Republic of Korea | X | |||

| Laos | X | X | ||

| Malaysia | Sabah | X | X | |

| Sarawak | X | X | ||

| West | X | X | ||

| Maldives | X | |||

| Myanmar | X | |||

| Nepal | X | |||

| Oman | X | |||

| Pakistan | X | X | ||

| Philippines | X | X | ||

| Singapore | X | |||

| Sri Lanka | X | X | ||

| Taiwan | X | |||

| Thailand | X | X | ||

| United Arab Emirates | X | |||

| Viet Nam | X | X | ||

| Yemen | X | |||

| Europe (non EU) | Montenegro | X | ||

| Oceania | Australia | Northern Territory | X | |

| Queensland | X | |||

| Guam | X | |||

| Micronesia | X | |||

| Northern Mariana Islands | X | |||

| Papua New Guinea | X | X | ||

| Solomon Islands | X |

The identification in 2011 of a new Aleurocanthus species, A. camelliae, on tea in Japan and China, which had remained misidentified as A. spiniferus, creates uncertainty about the identify of data reported as A. spiniferus from Japan.

Figure 1.

Global distribution of Aleurocanthus woglumi (extracted from the EPPO Global Database accessed on 6.4.2018)

Figure 2.

Global distribution of Aleurocanthus spiniferus (extracted from the EPPO Global Database accessed on 12.9.2018)

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU?

Yes, the genus Aleurocanthus does occur in the EU. A. spiniferus is reported as present in the EU in restricted areas of Italy and Greece where it is under official control.

No other Aleurocanthus spp. are known to occur in the EU.

A. spiniferus is present in the EU. The first report of the species in the EU was from Italy, in a citrus backyard orchard in Apulia at the end of 2008 (Porcelli, 2008). The species subsequently spread in the Puglia region (Cioffi et al., 2013; El Kenawy et al., 2014). The Italian NPPO reported A. spiniferus in 2017 in Salerno town, in the Campania region, on lemon and tangerine; and in Roma on Citrus spp., Hedera helix and Rosa sp. Official phytosanitary measures are in place which seek to contain the pest (Europhyt Notifications No. 239 and 255 from 2017). In August 2018, A. spiniferus was reported from the North East Italy (Bolonia) (Europhyt Notification 621).

A. spiniferus has recently been reported from Greece, in the north‐east part of the island of Corfu. Official phytosanitary measures in the form of chemical, biological or physical treatment, which seek to eradicate the pest are in place (Europhyt Notifications No. 125 from 2016 and No. 529 from 2018).

A. spiniferus was also reported from Croatia in 2012 on ornamental potted orange seedlings (Citrus x aurantium L.) at one nursery garden in Split, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Action was taken to eradicate it (Šimala and Masten Milek, 2013). Presently, A. spiniferus is reported as eradicated by official surveys conducted in 2015. In 2016, the absence of the pest in Croatia was confirmed.

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Council Directive 2000/29/EC

Aleurocanthus spp. is listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Details are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Aleurocanthus spp. in Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex II, Part A | Harmful organisms whose introduction into, and spread within, all member states shall be banned if they are present on certain plants or plant products | |

| Section I | Harmful organisms not known to occur in the community and relevant for the entire community | |

| (a) | Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Species | Subject of contamination | |

| 11. | Aleurocantus spp. | Plants of Citrus L., Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids, other than fruit and seeds |

3.3.2. Legislation addressing the hosts of Aleurocanthus spp.

Table 4.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve Aleurocanthus spp. in Annexes III, IV and V of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex III, Part A | Plants, plant products and other objects the introduction of which shall be prohibited in all Member States | |

| Description | Country of origin | |

| 16 | Plants of Citrus L, Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids, other than fruit and seeds | Third countries |

| Annex IV, Part A | Special requirements which shall be laid down by all member states for the introduction and movement of plants, plant products and other objects into and within all member states | |

| Section I | Plants, plant products and other objects originating outside the community | |

| Plants, plant products and other objects | Special requirements | |

| 16.1 | Fruits of Citrus L, Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids, originating in third countries | The fruits should be free from peduncles and leaves and the packaging should bear an appropriate origin mark. |

| 16.5 | Fruits of Citrus L, Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids, originating in third countries |

Without prejudice to the provisions applicable to the fruits in Annex IV(A)(I) (16.1), (16.2) and (16.3), official statement that:

|

| Annex V | Plants, plant products and other objects which must be subject to a plant health inspection (at the place of production if originating in the Community, before being moved within the Community — in the country of origin or the consignor country, if originating outside the Community) before being permitted to enter the Community | |

| Part B | Plants, plant products and other objects originating in territories, other than those territories referred to in Part A | |

| Section I | Plants, plant products and other objects which are potential carriers of harmful organisms of relevance for the entire Community | |

| 1 | Plants, intended for planting, other than seeds but including seeds of […] Citrus L., Fortunella Swingle and Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids […] | |

| 3 |

Fruits of:— Citrus L., Fortunella Swingle, Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids […] |

|

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Host range

Aleurocanthus spp. is regulated in the EU on Citrus, Fortunella and Poncirus. Several species in the genus Aleurocanthus are reported to have citrus as host plants; however, most of them have a wider host range. A. woglumi occurs throughout much of the Asian range of A. spiniferus and the two species possibly share many of their hosts. These species are two of the major citrus pests and are both highly polyphagous.

A. spiniferus is reported to infest 90 plant species of 38 plant families, summarised in Cioffi et al. (2013). Citrus spp. are the main hosts of economic importance but A. spiniferus has been recorded on other crops, such as grapes (Vitis vinifera), guavas (Psidium guajava), pears (Pyrus spp.), persimmons (Diospyros kaki) and roses (Rosa spp.).

In the EU, A. spiniferus was reported for the first time on Citrus limon (Porcelli, 2008). During monitoring of A. spiniferus in Italy from 2009 to 2011, the insect was reported infesting plants of Rutaceae, Vitaceae, Araliaceae, Ebenaceae, Leguminosae‐Caesalpiniaceae, Malvaceae, Lauraceae, Moraceae, Punicaceae and Rosaceae. A. spiniferus was found to infest leaves of unreported host plants in urban areas, parks and natural protected habitats such as Citrus spp., Diospyros kaki, Ficus carica, Laurus nobilis, Malus cvs, Morus alba, Punica granatum, Pyrus spp., Rosa sp. and Vitis spp. The pest also infests the wild flora such as Hedera helix, Laurus nobilis, Prunus sp. and Salix sp. (Cioffi et al., 2013).

A. woglumi can infest more than 300 host plants, including cultivated plants, ornamentals and weeds, but mostly occurs in plants of the genus Citrus (lemon and tangerine; da Silva Lopes et al., 2013). A. woglumi occurs also on a wide range of other crops, mostly fruit trees, including avocados (Persea americana), bananas (Musa spp.), cashews (Anacardium occidentale), coffee (Coffea arabica), ginger (Zingiber officinale), grapes (Vitis vinifera), guavas (Psidium guajava), lychees (Litchi chinensis), mangoes (Mangifera indica), pawpaws (Carica papaya), pears (Pyrus spp.), pomegranates (Punica granatum), quinces (Cydonia oblonga) and roses (Rosa spp.). According to EPPO, 75 species in 38 families have been reported in Mexico as hosts on which A. woglumi can complete its life cycle (EPPO, 2017).

Uncertainty has been mentioned on the ability of A. woglumi to durably infest plants other than citrus. An experimental work on host preferences in greenhouses showed a preference of A. woglumi for laying eggs on Citrus spp. (lemon, orange and mandarin), maintaining a pattern of non‐preference in cashew and guava trees (da Silva Lopes et al., 2013). Steinberg and Dowell (1980) found evidence suggesting that A. woglumi cannot infest host species other than citrus for more than three generations, which may explain why serious infestations of other hosts are usually found in close proximity to citrus groves. However, while A. woglumi is primarily a pest of citrus, where infestations are heavy, it can also infest other species including avocado, banana, cashew, coffee, ginger, grape, mango, rose (Australian Government report, 2004). A. woglumi can be found on mango (Mangifera indica) for several generations and has been also reported from Croton sp. (CABI, 2018).

Information on the host range of other Aleurocanthus spp. is limited. Besides A. woglumi and A. spiniferus, several other species cause damage on crops of economic importance in the EU, mainly citrus, tea, bamboo, mangoes, palms (Appendix A). A. citriperdus is reported as a common pest of citrus in Indonesia (Gillespie, 2012). A. camelliae is an important pest in tea in Japan (Kasai et al., 2012) and China (Xie, 1995). A. mangiferae is mentioned as a destructive pest of mangoes in India (Australian Government report, 2004). A. longispinus is reported in Asia as completing the life cycle on bamboo (Varma and Sajeev, 1988).

3.4.2. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory?

Yes, Aleurocanthus spp. are able to enter the EU territory.

A. spiniferus has already entered and is established in a restricted area in Italy and has entered Greece. Aleurocanthus spp. could enter the EU on plants for planting, excluding seeds, and cut flowers or branches. There have been interceptions of Aleurocanthus in the EU. Up to 15 May 2018, there were 10 records of interception of Aleurocanthus spp. in the Europhyt database. Six of them were identified as A. woglumi on Citrus hystrix, Annona reticulata or Musaceae. Four interceptions were identified as A. spiniferus on either Camellia sasanqua or Camellia japonica. One interception of A. spiniferus found on C. japonica plants was reported in 2017 (Report of the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed, 2018). The recent identification of a new species on tea, A. camelliae, in Japan, previously having been misidentified as A. spiniferus (Kanmiya et al., 2011) suggests that the records of interceptions in the EU on Camellia plants refer to A. camelliae rather than to A. spiniferus. A. camelliae has been found on imported Camellia artificially dwarfed plants in the Netherlands (M. Jansen, pers. com).

The main pathways identified for Aleurocanthus species are:

host plants for planting, excluding seeds

host cut flowers or branches.

In a recent work targeting the identification of new pests likely to be introduced into Europe with fruit trade, none of the Aleurocanthus species were classified as potentially likely to enter with imports of oranges and mandarins into the EU (Suffert et al., 2018).

3.4.3. Establishment

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory?

Yes, A. spiniferus is established (under containment) in restricted areas of Italy and is present (under eradication) in Greece.

Several other species in the genus Aleurocanthus have the potential to establish into the EU territory.

One species in the genus Aleurocanthus, A. spiniferus, is already present in the EU. The current legislation does not make a distinction between species that are present and those that are not present in the EU.

The Aleurocanthus genus originates from tropical areas. However, some species occur in different regions of the world including areas where climate types match those occurring in the EU. Because suitable hosts occur across the EU, biotic and abiotic conditions are favourable for establishment.

3.4.3.1. EU distribution of main host plants

The occurrence of host plants in the EU depends on the species of Aleurocanthus considered. Many plant species reported as hosts of species of Aleurocanthus occur in the EU. Some of them are cultivated (e.g. Citrus spp., Vitis vinifera, Rosa spp.) or used in parks and recreational areas (e.g. Buxus sp. Populus sp. Camellia sp.). For polyphagous Aleurocanthus species, the presence of many potential hosts in the EU territory will favour establishment. Host range expansion could also occur as reported for A. spiniferus in Italy (Cioffi et al., 2013).

Aleurocanthus spp. infesting citrus are expected to be able to establish in citrus production areas in the EU. Table 5 shows the EU area of citrus cultivation for seven of the important citrus growing member states. According to EPPO (2017), citrus is the crop most at risk in the EU.

Table 5.

Citrus cultivation area (103 ha) in the EU. Source: Eurostat (data extracted on 21 September 2018, code: T0000)

| Country | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.21 | 2.19 | : |

| Cyprus | 2.63 | 2.69 | 2.84 | 3.41 | 3.48 |

| France | 4.34 | 4.16 | 4.21 | 4.22 | 4.35 |

| Greece | 50.41 | 49.50 | 50.94 | 45.39 | 44.52 |

| Italy | 163.59 | 140.16 | 149.10 | 147.65 | 135.36 |

| Portugal | 19.82 | 19.80 | 20.21 | 20.36 | 20.51 |

| Spain | 306.31 | 302.46 | 298.72 | 295.33 | 294.26 |

| EU (28 MS) | 549.28 | 520.95 | 528.23 | 518.54 | : |

data not available.

3.4.3.2. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

Since A. spiniferus is already present in Italy and in Greece, climatic conditions are considered suitable for the establishment of this species in the EU, at least in the Mediterranean area.

Some of the non‐EU Aleurocanthus spp., including species known as being pests in their native area, occur in climate zones that also occur in EU countries where host plants are grown (Appendix A). We assume that for those species, climatic conditions in the EU would not limit their establishment (e.g. A. woglumi, and A. camelliae).

The temperature requirements for most of the Aleurocanthus species are not precisely known and hence lead to uncertainty concerning their potential establishment.

3.4.4. Spread

Is the pest able to spread within the EU territory following establishment?

Yes, as a free‐living organism, adults of the Aleurocanthus species can disperse naturally, e.g. by walking and flying. The adults could also be dispersed for short distances by wind

RNQPs: Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects?

Yes, for several important pests in the genus Aleurocanthus, plants for planting, excluding seeds, would be probably the main means of spread.

Adults of Aleurocanthus spp. are capable of limited flight and this is not a major mean of long‐range dispersal (Meyerdink et al., 1979). Spread of Aleurocanthus spp. is mainly human assisted, largely by international trade in planting material of citrus or other hosts (USDA, 1988). Species of Aleurocanthus have been intercepted on the leaves of infested host plants moving in international trade (EPPO, 2017).

Three pests of citrus in the genus Aleurocanthus are described as highly invasive: A. spiniferus, A. woglumi and A. citriperdus. A. woglumi considered as exotic to Brazil, was first reported in 2001, has since become an important pest in many citrus‐producing regions of the country, causing direct and indirect damage to plants (Gonçalves Lima et al., 2017) and is presently reported from large parts of the Americas and the Caribbean islands. A. spiniferus originates in south‐east Asia, but now widely occurs in tropical and subtropical Asia and the Pacific, has spread to parts of central and southern Africa and is reported as present in a restricted area in the EU. A. citriperdus, while widely distributed in Fareast Asia, remains limited to tropical areas (Ouvrard and Martin, 2018, accessed 19/4/2018).

A. spiniferus spread from one place to another through nursery stocks and infested fruits (Gyeltshen et al., 2017). The species is reported as travelling on infested plants and twig‐decorated fruits (El Kenawy et al., 2014). We assume that the infested fruits referred in Gyeltshen et al. (2017) were fruits transported with infested leaves attached. Likewise, the EU‐project DROPSA devoted to identify new pests likely to be introduced into Europe with fruit trade, disregarded citrus fruits (oranges and mandarins) as a pathway for Aleurocanthus spp. (Suffert et al., 2018), as a citrus fruit from third countries imported into the EU should be free from peduncles and leaves.

In general, Aleurocanthus spp. are likely to be moved between countries on host plants for planting. Meyerdink et al. (1979) mentioned that A. spiniferus adults are able to fly downwind for a short distance and can enter cars or stick on people for long‐distance movement.

In the EU, A. spiniferus has been spreading in Italy since it was first found in 2008 in Puglia region (EPPO RS 2008/092, 2010/147). In June 2017, A. spiniferus was found on two citrus plants (Citrus limon and Citrus reticulata) in the urban area of Salerno (Campania region). In July 2017, its presence was also confirmed in the municipality of Roma (Lazio region) (El Kenawy et al., 2014). A. spiniferus was found in public and private gardens on Citrus, Hedera helix and Rosa (NPPO of Italy, 2017). Precise means of A. spiniferus spread in the EU is unknown; however, in the Roma region, pest introduction is related to ornamental sensitive plant trade from other infested areas according to Italian NPPO report (Notification No. 255 from 2017).

A. spiniferus was recorded in Croatia in 2012, on ornamental potted orange seedlings and action was taken to eradicate it (Šimala and Masten Milek, 2013). In 2013, A. spiniferus, was reported from Montenegro in citrus orchards in Baošići, Kumbor and Herceg Novi, in the area of the Boka Kotor Bay on the Adriatic Sea (Radonjic et al., 2014).

The rapid spread of A. camelliae in tea‐producing districts in Japan since the first occurrence in Kyoto in 2004 had suggested that the pest range expansion occurred via nymph transfer on tea seedlings, rather than via adult migratory flight (Kasai et al., 2012).

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes, several species of the genus Aleurocanthus have been reported as serious pests, in particular having economic impact in citrus in several continents and one (A. camelliae) on tea in Asia.

RNQPs: Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting?4

Yes, the presence of species of Aleurocanthus on plants for planting would have an economic impact.

Several Aleurocanthus species are reported in association with crops and causing economical loses, of which some infesting citrus, and are considered to be important pests. Typically, whiteflies affect host plants by sucking the sap, but they also cause damage by producing honeydew. The secretion of honeydew promotes the growth of sooty mould which covers leaves (reducing photosynthesis) and fruit (reducing quality).

A. spiniferus is considered as one of the most destructive citrus whiteflies (El Kenawy et al., 2014). El Kenawy et al. (2014) mentioned that the species is recorded as a serious pest of roses in India. The pest is also regarded as a potential threat to various ornamental plant hosts in Florida (Gyeltshen et al., 2017). A. spiniferus is regarded as a threat to citrus in Swaziland and South Africa and requires control in Japan and other Pacific countries. Another negative aspect is the pest ability to infest wild plants, which are the important pest reservoir (El Kenawy et al., 2014). The spread of A. spiniferus in Italy is considered as having serious consequences, where it represents a major threat to the environment because of the increasing pesticides use in response to massive infestations.

A. woglumi is one of the most important pests of citrus in almost all the citrus growing areas worldwide. In India, it is referred as responsible for citrus decline in Maharadhtra (David, 2012). Crop losses of limes due to A. woglumi were recorded at 25% (Plantwise Knowledge Bank factsheet, [Link]). A. woglumi has long been a threat to citrus crops in Mexico. Other crops, such as coffee, mangoes and pears, can also be attacked if planted near citrus groves heavily infested with the pest (Steinberg and Dowell, 1980).

A. woglumi is regarded as a constant menace to citrus and other crops in the USA and Venezuela. It has been recorded seriously affecting citrus in India (David, 2012). Le Pelley (1973) mentions A. woglumi as a severe pest of coffee in the New World. A woglumi shows a strong tendency to infest neighbouring plants, forming spots that grow through the planting line (da Silva et al., 2014).

A. spiniferus and A. woglumi cause a general weakening of the infested trees due to sap loss and development of sooty mould. The leaves, fruit and branches of infested trees are usually covered with sooty mould. A heavy infestation gives trees an almost completely black appearance. Dense colonies of immature stages develop on leaf undersides; the adults fly actively when disturbed. Feeding by A. woglumi can reduce fruit set by up to 80% or more (Eberling, 1954). Same as A. spiniferus, the colonisation of honeydew deposited on the fruit by sooty mould causes fruit downgrading.

A. spiniferus and A. woglumi have not been recorded as glasshouse pests, but, it could conceivably become pests in heated glasshouses in temperate countries (CABI, 2018).

A. citriperdus is reported as a common pest of citrus in Indonesia and a serious horticultural pest in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia (Gillespie, 2012).

A. camelliae is an important pest in tea plantations in Japan (Kasai et al., 2012) and in China (Chen et al., 2016), in the Guangdong province (Xie, 1995).

A. mangiferae is mentioned as a destructive pest of mangoes in India (Australian Government report, 2004).

A. longispinus is reported on bamboo in Asia. None of the Aleurocanthus species on bamboo are reported as being serious pests (Nguyen et al., 1993).

A. valenciae has been recorded as damaging citrus in Australia (Gillespie, 2012).

3.6. Availability and limits of mitigation measures

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, the same measures already in place for citrus (see Section 3.3) could be applied to the import of plants for planting and cut branches of other host plants. A few additional methods (physical, chemical and biological) could be used to contain and eradicate the pest in the EU.

RNQPs: Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, sourcing plants for planting from pest free areas.

3.6.1. Identification of additional measures

Aleurocanthus spp. are regulated in the EU on Citrus, Fortunella and Poncirus (see Section 3.3). As the two major pests of citrus, A. spiniferus and A. woglumi, are polyphagous, highly invasive species and numerous other plants could represent potential pathways (mostly plants for planting, excluding seeds, and cut branches), these measures could be extended to other potential hosts. Furthermore, EPPO recommends that planting material and produce of host plants of A. woglumi and A. spiniferus, especially citrus, should be inspected in the growing season previous to shipment and should be found free of infestation (EPPO, 2017). A phytosanitary certificate should guarantee absence of the pest from consignments of fruit. Whole or parts of host plants from countries where A. woglumi and A. spiniferus occurs should be fumigated (CABI, 2018). These measures recommended for the two citrus pests, would also be appropriate for other Aleurocanthus pests too. Therefore, additional measures would include:

Additional control measures (control measures have a direct effect on pest abundance):

Growing plants in isolation (i.e. nurseries)

Chemical control

Classical biological control

Conservation biological control.

Supporting measures (supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of the appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance):

Inspection

Laboratory testing

Plant health inspection

Certified and approved premises for export

Certification of nursery plants

Establishment of demarcated and buffer zones

Surveillance.

3.6.1.1. Additional control measures

Potential additional control measures for the mitigation of risk from Aleurocanthus spp. are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Selected control measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) for pest entry/establishment/spread/impact in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance

| Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Control measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1175887 | As a pest that is a poor flyer and which does not disperse widely, growing plants in isolation is a measure to consider. Non‐orchard hosts (i.e. nurseries) could be grown within physical protection, e.g. a dedicated structure such as glass or plastic greenhouse | Entry, spread, establishment, impact |

| Chemical treatments on crops including reproductive material (Work in progress, not yet available) | In general, chemical control has not proved effective against A. spiniferus, or other whiteflies in crop systems (Gyeltshen and Hodges, 2010). Frequent use of pesticides is harmful to natural enemies, and inappropriate timing of sprays seems to contribute to the increased severity of infestation (Zhang, 2006 ‐ In Cioffi 2013) | Entry (affects population at source), spread, establishment, impact |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1175910 | It is possible to control A. woglumi (and probably A. spiniferus) by fumigation of planting material, or with chemical sprays, but the latter is likely to require several successive applications because the waxy nature of the immature stages and the non‐feeding period in the ‘pupa’ reduces susceptibility (CABI, 2018) | Entry, spread |

| Biological control and behavioural manipulation (Work in progress, not yet available) |

Several natural enemies appear to be effective to control whiteflies. A. woglumi has been effectively controlled by natural enemies in all of the countries where introductions have been successful (Clausen, 1978). This is the most cost‐effective and sustainable method of control, and the parasitoids available are capable of controlling it wherever it becomes established (CABI, 2018) In Japan, A. spiniferus long recognised as a pest of citrus, was fully controlled on citrus by an introduced parasitoid wasp (Encarsia smithi) from China, and heavy infestations decreased to a low level (Kuwana and Ishii, 1927; Ohgushi, 1969) |

Establishment, spread, impact |

3.6.1.2. Additional supporting measures

Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance. Potential supporting measures relevant to Aleurocanthus spp. are listed below in Table 7.

Table 7.

Selected supporting measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance

| Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Supporting measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181430 | Imported host plants for planting and fruit could be inspected for compliance from freedom of Aleurocanthus spp. | Entry, establishment, spread (within containment zones) |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181213 | Examination, other than visual, to determine if pests are present using official diagnostic protocols | Entry |

| Sampling (Work in progress, not yet available) | According to ISPM 31, it is usually not feasible to inspect entire consignments, so phytosanitary inspection is performed mainly on samples obtained from a consignment | Entry, establishment, spread |

| Phytosanitary certificate and plant passport (Work in progress, not yet available) | An official paper document or its official electronic equivalent, consistent with the model certificates of the IPPC, attesting that a consignment meets phytosanitary import requirements (ISPM 5) | Entry, establishment, spread |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180845 | Mandatory/voluntary certification/approval of premises is a process including a set of procedures and of actions implemented by producers, conditioners and traders contributing to ensure the phytosanitary compliance of consignments. It can be a part of a larger system maintained by a National Plant Protection Organization in order to guarantee the fulfilment of plant health requirements of plants and plant products intended for trade | Entry, establishment, spread |

| Certification of reproductive material (voluntary/official) (Work in progress, not yet available) | Reproductive material could be examined and certified free from Aleurocanthus spp. | Entry, establishment, spread |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180597 | Sourcing plants from a pest free place of production, site or area, surrounded by a buffer zone, would minimise the probability of spread into the pest free zone | Entry |

| Surveillance (Work in progress, not yet available) | ISPM 5 defines surveillance as an official process which collects and records data on pest occurrence or absence by survey, monitoring or other procedures | Establishment, spread |

3.6.1.3. Biological or technical factors limiting the effectiveness of measures to prevent the entry, establishment and spread of the pest

Identification of the different species within the genus Aleurocanthus is based on the morphology of puparia only and high expertise is needed to separate closely related species.

Detection of small populations is difficult.

3.7. Uncertainty

Identity at the species level is not established for all Aleurocanthus spp.

Species identification needs high expertise, and misidentifications might occur (e.g. A. spiniferus remained misidentified for two years after its arrival in Italy).

Host preference of the non‐EU Aleurocanthus spp. is largely unknown. Uncertainty on pathways excluding the best documented species (Appendix A).

Uncertainty exists regarding potential damage of Aleurocanthus species not known to be present in the EU. For these species, transfer to new environments might lead to changes in damage caused by the pest.

Uncertainty regarding effectiveness of official control measures to contain spread of A. spiniferus in Italy.

4. Conclusions

Aleurocanthus spp. meets the criteria assessed by EFSA for consideration as a Union quarantine pest (Table 8).

Table 8.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column) for Aleurocanthus spp

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Yes, the identity of the genus Aleurocanthus is established | Yes, the identity of the genus Aleurocanthus is established |

|

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) | Yes, Aleurocanthus is present in the EU, in a restricted area of Italy and Greece where it is under official control | Yes, Aleurocanthus is present in the EU, in a restricted area of Italy and Greece where it is under official control | Uncertainty regarding the presence of A. camelliae in EU. A manuscript has been submitted to a journal regarding finds on Camellia plants imported into the Netherlands (Jansen pers. comm.) |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3 ) | Aleurocanthus spp. are listed in II AI of 2000/29 EC and are currently regulated on Citrus, Fortunella and Poncirus plants and their hybrids, other than fruit and seeds | Aleurocanthus spp. are listed in II AI of 2000/29 EC and are currently regulated on Citrus, Fortunella and Poncirus plants and their hybrids, other than fruit and seeds | None |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) |

Aleurocanthus can enter and spread in the EU. Pathways of entry include plants for planting, excluding seeds, and host cut flowers or branches Aleurocanthus is already in the EU and it is also able to enter and spread with plants for planting (excluding seeds) and cut flowers and branches It could spread within the EU on host plant material or leaves attached to fruits. Short‐distance spread can occur naturally (adults are winged) |

Aleurocanthus species are able to enter and spread in the EU, plants for planting would be the main pathway | None |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) |

The establishment of several Aleurocanthus species could have an economic impact in several crops in the EU The most important crops at risk are citrus and tea. Other crops at risk might be mango, palms and bamboo |

Aleurocanthus spp. could have an economic impact if present on host plants for planting | Besides on citrus, uncertainty exists regarding the extent of damage that Aleurocanthus spp. would cause to other plants in the EU |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Phytosanitary measures are available to reduce the likelihood of entry into the EU, e.g. sourcing host plants for planting from pest free areas | Pest‐free area and pest free places/sites of production reduce the likelihood of pests being present on plants for planting | None |

| Conclusion on pest categorisation (Section 4 ) | As a genus Aleurocanthus does satisfy all the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess to allow it consideration by risk managers as a Union quarantine pest | Aleurocanthus does not meet all of the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess to allow it consideration by risk managers as a Union RNQP. Specifically Aleurocanthus is not widespread in the EU |

|

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate | If the taxonomy of the genus were to be resolved, in principle it would be possible to distinguish between species of Aleurocanthus that satisfy the criteria to be considered for Union quarantine pest status and those that do not. However, efficient methods for species identification are needed. A revision of the genus to allow species delimitation is needed | ||

Abbreviations

- DG SANTÉ

Directorate General for Health and Food Safety

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

protected zone

- RNQP

regulated non‐quarantine pest

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

Glossary

(terms defined in ISPM 5 unless indicated by +)

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control measures+

Measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance.

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2017)

- Establishment (of a pest

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2017)

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2017)

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2017)

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2017)

- Protected zones (PZ)

A Protected zone is an area recognised at EU level to be free from a harmful organism, which is established in one or more other parts of the Union

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP)

A non‐quarantine pest whose presence in plants for planting affects the intended use of those plants with an economically unacceptable impact and which is therefore regulated within the territory of the importing contracting party (FAO, 2017)

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO 2017)

- Supporting measures+