Abstract

The European Commission requested EFSA to conduct a pest categorisation of Acrobasis pirivorella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), a monophagous moth whose larvae exclusively feed on developing buds, flowers, and fruits of cultivated and wild Pyrus spp. A. pirivorella is a species with reliable methods available for identification. A. pirivorella occurs in north‐east Asia only, causing significant damage in cultivated pears. It is regulated in the EU by Council Directive 2000/29/EC where it is listed in Annex IIAI. Within this regulation, plants for planting of Pyrus spp. is a closed pathway. This species has never been reported by Europhyt. Fruits and cut branches of Pyrus spp. are open pathways. Biotic and abiotic conditions are conducive for establishment and spread of A. pirivorella in the EU. Were A. pirivorella to establish, impact on pear production is expected. Considering the criteria within the remit of EFSA to assess its regulatory plant health status, A. pirivorella meets the criteria for consideration as a potential Union quarantine pest (it is absent from the EU, potential pathways exist and its establishment would cause an economic impact). Given that A. pirivorella is not known to occur in the EU, it fails to meet some of the criteria required for regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) status.

Keywords: European Union, pest risk, plant health, plant pest, quarantine, pear moth, Pyralidae

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

Council Directive 2000/29/EC1 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community establishes the present European Union plant health regime. The Directive lays down the phytosanitary provisions and the control checks to be carried out at the place of origin on plants and plant products destined for the Union or to be moved within the Union. In the Directive's 2000/29/EC annexes, the list of harmful organisms (pests) whose introduction into or spread within the Union is prohibited, is detailed together with specific requirements for import or internal movement.

Following the evaluation of the plant health regime, the new basic plant health law, Regulation (EU) 2016/20312 on protective measures against pests of plants, was adopted on 26 October 2016 and will apply from 14 December 2019 onwards, repealing Directive 2000/29/EC. In line with the principles of the above mentioned legislation and the follow‐up work of the secondary legislation for the listing of EU regulated pests, EFSA is requested to provide pest categorisations of the harmful organisms included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC, in the cases where recent pest risk assessment/pest categorisation is not available.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 22(5.b) and Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/20023, to provide scientific opinion in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to prepare and deliver a pest categorisation (step 1 analysis) for each of the regulated pests included in the appendices of the annex to this mandate. The methodology and template of pest categorisation have already been developed in past mandates for the organisms listed in Annex II Part A Section II of Directive 2000/29/EC. The same methodology and outcome is expected for this work as well.

The list of the harmful organisms included in the annex to this mandate comprises 133 harmful organisms or groups. A pest categorisation is expected for these 133 pests or groups and the delivery of the work would be stepwise at regular intervals through the year as detailed below. First priority covers the harmful organisms included in Appendix 1, comprising pests from Annex II Part A Section I and Annex II Part B of Directive 2000/29/EC. The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 1 is June 2018. The second priority is the pests included in Appendix 2, comprising the group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), the group of Tephritidae (non‐EU), the group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms, the group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L.. and the group of Margarodes (non‐EU species). The delivery of all pest categorisations for the pests included in Appendix 2 is end 2019. The pests included in Appendix 3 cover pests of Annex I part A section I and all pests categorisations should be delivered by end 2020.

For the above mentioned groups, each covering a large number of pests, the pest categorisation will be performed for the group and not the individual harmful organisms listed under “such as” notation in the Annexes of the Directive 2000/29/EC. The criteria to be taken particularly under consideration for these cases, is the analysis of host pest combination, investigation of pathways, the damages occurring and the relevant impact.

Finally, as indicated in the text above, all references to ‘non‐European’ should be avoided and replaced by ‘non‐EU’ and refer to all territories with exception of the Union territories as defined in Article 1 point 3 of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031.

1.1.2.1. Terms of Reference: Appendix 1

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Aleurocantus spp. | Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) |

| Anthonomus bisignifer (Schenkling) | Oligonychus perditus Pritchard and Baker |

| Anthonomus signatus (Say) | Pissodes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Aschistonyx eppoi Inouye | Scirtothrips aurantii Faure |

| Carposina niponensis Walsingham | Scirtothrips citri (Moultex) |

| Enarmonia packardi (Zeller) | Scolytidae spp. (non‐EU) |

| Enarmonia prunivora Walsh | Scrobipalpopsis solanivora Povolny |

| Grapholita inopinata Heinrich | Tachypterellus quadrigibbus Say |

| Hishomonus phycitis | Toxoptera citricida Kirk. |

| Leucaspis japonica Ckll. | Unaspis citri Comstock |

| Listronotus bonariensis (Kuschel) | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Citrus variegated chlorosis | Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae (Ishiyama) Dye and pv. oryzicola (Fang. et al.) Dye |

| Erwinia stewartii (Smith) Dye | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler (non‐EU pathogenic isolates) | Elsinoe spp. Bitanc. and Jenk. Mendes |

| Anisogramma anomala (Peck) E. Müller | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Kilian and Maire) Gordon |

| Apiosporina morbosa (Schwein.) v. Arx | Guignardia piricola (Nosa) Yamamoto |

| Ceratocystis virescens (Davidson) Moreau | Puccinia pittieriana Hennings |

| Cercoseptoria pini‐densiflorae (Hori and Nambu) Deighton | Stegophora ulmea (Schweinitz: Fries) Sydow & Sydow |

| Cercospora angolensis Carv. and Mendes | Venturia nashicola Tanaka and Yamamoto |

| (d) Virus and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet curly top virus (non‐EU isolates) | Little cherry pathogen (non‐ EU isolates) |

| Black raspberry latent virus | Naturally spreading psorosis |

| Blight and blight‐like | Palm lethal yellowing mycoplasm |

| Cadang‐Cadang viroid | Satsuma dwarf virus |

| Citrus tristeza virus (non‐EU isolates) | Tatter leaf virus |

| Leprosis | Witches’ broom (MLO) |

| Annex IIB | |

| (a) Insect mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Anthonomus grandis (Boh.) | Ips cembrae Heer |

| Cephalcia lariciphila (Klug) | Ips duplicatus Sahlberg |

| Dendroctonus micans Kugelan | Ips sexdentatus Börner |

| Gilphinia hercyniae (Hartig) | Ips typographus Heer |

| Gonipterus scutellatus Gyll. | Sternochetus mangiferae Fabricius |

| Ips amitinus Eichhof | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens (Hedges) Collins and Jones | |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Glomerella gossypii Edgerton | Hypoxylon mammatum (Wahl.) J. Miller |

| Gremmeniella abietina (Lag.) Morelet | |

1.1.2.2. Terms of Reference: Appendix 2

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested per group. The list below follows the categorisation included in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Cicadellidae (non‐EU) known to be vector of Pierce's disease (caused by Xylella fastidiosa), such as: | |

| 1) Carneocephala fulgida Nottingham | 3) Graphocephala atropunctata (Signoret) |

| 2) Draeculacephala minerva Ball | |

| Group of Tephritidae (non‐EU) such as: | |

| 1) Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) | 12) Pardalaspis cyanescens Bezzi |

| 2) Anastrepha ludens (Loew) | 13) Pardalaspis quinaria Bezzi |

| 3) Anastrepha obliqua Macquart | 14) Pterandrus rosa (Karsch) |

| 4) Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) | 15) Rhacochlaena japonica Ito |

| 5) Dacus ciliatus Loew | 16) Rhagoletis completa Cresson |

| 6) Dacus curcurbitae Coquillet | 17) Rhagoletis fausta (Osten‐Sacken) |

| 7) Dacus dorsalis Hendel | 18) Rhagoletis indifferens Curran |

| 8) Dacus tryoni (Froggatt) | 19) Rhagoletis mendax Curran |

| 9) Dacus tsuneonis Miyake | 20) Rhagoletis pomonella Walsh |

| 10) Dacus zonatus Saund. | 21) Rhagoletis suavis (Loew) |

| 11) Epochra canadensis (Loew) | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Group of potato viruses and virus‐like organisms such as: | |

| 1) Andean potato latent virus | 4) Potato black ringspot virus |

| 2) Andean potato mottle virus | 5) Potato virus T |

| 3) Arracacha virus B, oca strain | 6) non‐EU isolates of potato viruses A, M, S, V, X and Y (including Yo, Yn and Yc) and Potato leafroll virus |

| Group of viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L.,Rubus L. and Vitis L., such as: | |

| 1) Blueberry leaf mottle virus | 8) Peach yellows mycoplasm |

| 2) Cherry rasp leaf virus (American) | 9) Plum line pattern virus (American) |

| 3) Peach mosaic virus (American) | 10) Raspberry leaf curl virus (American) |

| 4) Peach phony rickettsia | 11) Strawberry witches’ broom mycoplasma |

| 5) Peach rosette mosaic virus | 12) Non‐EU viruses and virus‐like organisms of Cydonia Mill., Fragaria L., Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L., Ribes L., Rubus L. and Vitis L. |

| 6) Peach rosette mycoplasm | |

| 7) Peach X‐disease mycoplasm | |

| Annex IIAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Group of Margarodes (non‐EU species) such as: | |

| 1) Margarodes vitis (Phillipi) | 3) Margarodes prieskaensis Jakubski |

| 2) Margarodes vredendalensis de Klerk | |

1.1.2.3. Terms of Reference: Appendix 3

List of harmful organisms for which pest categorisation is requested. The list below follows the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC.

| Annex IAI | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Acleris spp. (non‐EU) | Longidorus diadecturus Eveleigh and Allen |

| Amauromyza maculosa (Malloch) | Monochamus spp. (non‐EU) |

| Anomala orientalis Waterhouse | Myndus crudus Van Duzee |

| Arrhenodes minutus Drury | Nacobbus aberrans (Thorne) Thorne and Allen |

| Choristoneura spp. (non‐EU) | Naupactus leucoloma Boheman |

| Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) | Premnotrypes spp. (non‐EU) |

| Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetverikov | Pseudopityophthorus minutissimus (Zimmermann) |

| Diabrotica barberi Smith and Lawrence | Pseudopityophthorus pruinosus (Eichhoff) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber | Scaphoideus luteolus (Van Duzee) |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Mannerheim | Spodoptera eridania (Cramer) |

| Diabrotica virgifera zeae Krysan & Smith | Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) |

| Diaphorina citri Kuway | Spodoptera litura (Fabricus) |

| Heliothis zea (Boddie) | Thrips palmi Karny |

| Hirschmanniella spp., other than Hirschmanniella gracilis (de Man) Luc and Goodey | Xiphinema americanum Cobb sensu lato (non‐EU populations) |

| Liriomyza sativae Blanchard | Xiphinema californicum Lamberti and Bleve‐Zacheo |

| (b) Fungi | |

| Ceratocystis fagacearum (Bretz) Hunt | Mycosphaerella larici‐leptolepis Ito et al. |

| Chrysomyxa arctostaphyli Dietel | Mycosphaerella populorum G. E. Thompson |

| Cronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phoma andina Turkensteen |

| Endocronartium spp. (non‐EU) | Phyllosticta solitaria Ell. and Ev. |

| Guignardia laricina (Saw.) Yamamoto and Ito | Septoria lycopersici Speg. var. malagutii Ciccarone and Boerema |

| Gymnosporangium spp. (non‐EU) | Thecaphora solani Barrus |

| Inonotus weirii (Murril) Kotlaba and Pouzar | Trechispora brinkmannii (Bresad.) Rogers |

| Melampsora farlowii (Arthur) Davis | |

| (c) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Tobacco ringspot virus | Pepper mild tigré virus |

| Tomato ringspot virus | Squash leaf curl virus |

| Bean golden mosaic virus | Euphorbia mosaic virus |

| Cowpea mild mottle virus | Florida tomato virus |

| Lettuce infectious yellows virus | |

| (d) Parasitic plants | |

| Arceuthobium spp. (non‐EU) | |

| Annex IAII | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Meloidogyne fallax Karssen | Rhizoecus hibisci Kawai and Takagi |

| Popillia japonica Newman | |

| (b) Bacteria | |

| Clavibacter michiganensis (Smith) Davis et al. ssp. sepedonicus (Spieckermann and Kotthoff) Davis et al. | Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith) Yabuuchi et al. |

| (c) Fungi | |

| Melampsora medusae Thümen | Synchytrium endobioticum (Schilbersky) Percival |

| Annex I B | |

| (a) Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say | Liriomyza bryoniae (Kaltenbach) |

| (b) Viruses and virus‐like organisms | |

| Beet necrotic yellow vein virus | |

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

Acrobasis pirivorella (Matsamura) (1900) is the current valid name for the species listed as Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) in Annex IIAI (see Section 3.1.1). Therefore, the species under scrutiny in this opinion will be referred to using its currently valid name. A. pirivorella is one of a number of pests listed in the Appendices to the Terms of Reference (ToR) to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of a quarantine pest or those of a regulated non‐quarantine pest (RNQP) for the area of the EU excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States (MS) referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Literature search

A literature search on A. pirivorella was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using scientific current and past names of the pest as search terms. Relevant papers were reviewed and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.2. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO Global Database, 2018) and relevant publications.

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Communities).

The Europhyt database was consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission, and is a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. The Europhyt database manages notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the MS and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread.

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for A. pirivorella, following guiding principles and steps in the International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures No 11 (FAO, 2013) and No 21 (FAO, 2004) and EFSA PLH Panel (2018).

This work was initiated following an evaluation of the EU plant health regime. Therefore, to facilitate the decision‐making process, in the conclusions of the pest categorisation, the Panel addresses explicitly each criterion for a Union quarantine pest and for a Union RNQP in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants, and includes additional information required in accordance with the specific terms of reference received by the European Commission. In addition, for each conclusion, the Panel provides a short description of its associated uncertainty.

Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. All relevant criteria have to be met for the pest to potentially qualify either as a quarantine pest or as a RNQP. If one of the criteria is not met, the pest will not qualify. A pest that does not qualify as a quarantine pest may still qualify as a RNQP that needs to be addressed in the opinion. For the pests regulated in the protected zones only, the scope of the categorisation is the territory of the protected zone; thus, the criteria refer to the protected zone instead of the EU territory.

Table 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding protected zone quarantine pest (articles 32–35) | Criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1) | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? | Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU? Describe the pest distribution briefly! |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a protected zone quarantine organism | Is the pest present in the EU territory? If not, it cannot be a regulated non‐quarantine pest. (A regulated non‐quarantine pest must be present in the risk assessment area) |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3) | If the pest is present in the EU but not widely distributed in the risk assessment area, it should be under official control or expected to be under official control in the near future |

The protected zone system aligns with the pest free area system under the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) The pest satisfies the IPPC definition of a quarantine pest that is not present in the risk assessment area (i.e. protected zone) |

Is the pest regulated as a quarantine pest? If currently regulated as a quarantine pest, are there grounds to consider its status could be revoked? |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways! |

Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the protected zone areas? Is entry by natural spread from EU areas where the pest is present possible? |

Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects? Clearly state if plants for planting is the main pathway! |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? | Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the protected zone areas? | Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the protected zone areas such that the risk becomes mitigated? Is it possible to eradicate the pest in a restricted area within 24 months (or a period longer than 24 months where the biology of the organism so justifies) after the presence of the pest was confirmed in the protected zone? |

Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as potential protected zone quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine pest were met, and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met |

It should be noted that the Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, the Panel will present a summary of the observed pest impacts. Economic impacts are expressed in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, whereas addressing social impacts is outside the remit of the Panel.

The Panel will not indicate in its conclusions of the pest categorisation whether to continue the risk assessment process, but following the agreed two‐step approach, will continue only if requested by the risk managers. However, during the categorisation process, experts may identify key elements and knowledge gaps that could contribute significant uncertainty to a future assessment of risk. It would be useful to identify and highlight such gaps so that potential future requests can specifically target the major elements of uncertainty, perhaps suggesting specific scenarios to examine.

3. Pest categorisation

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest established, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible?

Yes, the identity of A. pirivorella is well established.

The pear fruit moth or pear moth, A. pirivorella (Matsamura), is an insect of the order Lepidoptera, family Pyralidae. This species was originally described by Matsamura in 1900 (Matsumura, 1900) as Nephopteryx pirivorella from specimens collected in pears in Japan. Synonyms for this insect include Nephopterix pirivorella Matsumura, Nephopteryx pauperculella (Wileman), Acrobasis pyrivorella (Matsumura), Ectomyelois pyrivorella (Matsumura), Eurhodope pirivorella (Matsumura), Numonia pirivora (Gerasimov), Numonia pyrivorella (Matsumura) and Rhodophaea pirivorella (Matsumura) (Nuss et al., 2003; Walker, 2011).

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

First‐instar larvae or, more commonly, second‐instar larvae of A. pirivorella overwinter in the flower buds of pears in a thin white cocoon (Shutova, 1970; Gibanov and Sanin, 1971). Although these buds die, they do not fall. In spring, these larvae infest developing buds, flowers and fruitlets. A single larva can destroy up to three of each of these plant organs during its development (Shutova, 1977) before reaching the third larval instar and boring into the core of the young fruit (Makaji, 1965). Upon completion of development, larvae spin a silk attachment to hold the fruit onto the tree, which together with the presence of black shrivelled fruitlets persisting on the trees are the typical symptom of attack by this species. The larva makes a prominent hole in each fruit near the calyx end with an overhanging lip of silk and excreta (EPPO Global database, 2018). In Russia, larvae pupate in the fruit, usually at the end of May and first adults emerge by mid‐July when the fruit is about the size of a hazelnut. However, peak adult emergence occurs between late July and mid‐August (Komarova, 1984). These moths, which are not good flyers, mate and lay about 120 eggs per female both on the flower buds and on the fruit. Eggs deposited on flower buds hatch in 8–10 days. Larvae penetrate flower buds and fruits to form the overwintering cocoons (Anonymous). However, larvae from eggs deposited on fruit complete development and may produce a new generation in September. These adults then lay eggs on flower buds and the resulting larvae overwinter. There is one generation per year in Russia and 2–3 in Japan (Shutova, 1977). Infested fruit remain black and shrivelled on the tree.

3.1.3. Intraspecific diversity

No intraspecific diversity has been described for this species.

3.1.4. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, detection and identification methods for A. pirivorella are available.

Pheromone trapping: (Z)‐9‐pentadecenyl acetate (Z9‐15:OAc) and pentadecenyl acetate (15:OAc) were identified in the pheromone gland of female A. pyrivorella. In a field experiment, traps baited with a lure containing Z9‐15:OAc (300 μg) and 15:OAc (21 μg) caught more males than ones baited with two virgin females (Tabata et al., 2009). Therefore, this lure could be used for monitoring and detection purposes.

Symptoms: infested fruits are normally retarded in growth and turn black and shrivelled. Moreover, these fruits remain on the tree even until the following year (Shutova, 1977). During summer conspicuous webbings on exit holes and masses of excreta on the exterior of the fruit are indicative of infestation by A. pirivorella (Shutova, 1977).

Morphology: the different developmental stages of A. pirivorella are described at EPPO Global database (2018). Adults are 9–13 mm long and have a 23–30 mm wingspan (Matsamura, 1900). The forewings have two transverse stripes and a crescent‐shaped dark apical spot between them. The hindwings are yellowish‐grey. The head, thorax and dorsum are covered with ashen‐violet‐brown bands. The species was originally described by Matsumura (1900).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

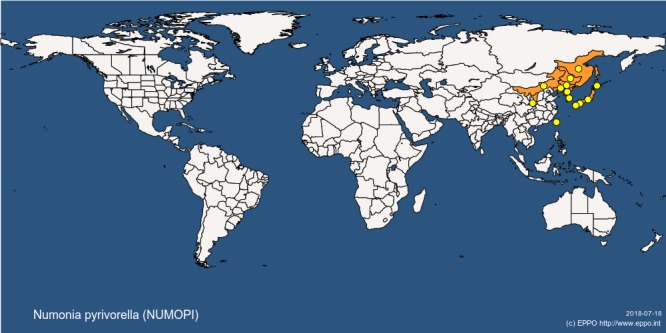

According to EPPO Global Database (2018), A. pirivorella occurs in a few countries in Asia Far East, including Japan, Taiwan, the two Korea's and some areas of China and Russia (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Current distribution of Acrobasis pirivorella worldwide (EPPO Global Database accessed 16 July 2018)

| Continent | Country | State | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | China | Present, restricted distribution | |

| China | [Guangdong] | Absent, unreliable record | |

| China | Heilongjiang | Present, no details | |

| Jilin | Present, no details | ||

| Liaoning | Present, no details | ||

| Neimenggu | Present, no details | ||

| Shaanxi | Present, no details | ||

| Japan | Present, widespread | ||

| Hokkaido | Present, widespread | ||

| Honshu | Present, widespread | ||

| Kyushu | Present, widespread | ||

| Shikoku | Present, widespread | ||

| Korea Dem. People's Republic | Present, no details | ||

| Korea, Republic | Present, no details | ||

| Taiwan | Present, no details | ||

| Russia | Present, restricted distribution | ||

| Russia | Far East | Present, no details |

Figure 1.

Global distribution map for Acrobasis pirivorella (extracted from EPPO Global Database, 2018; accessed 13 July 2018). There are no reports of transient populations for this species

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest widely distributed within the EU?

No, A. pirivorella is not known to occur in the EU; it has never been reported from the EU

According to EPPO Global Database (accessed on 31 July 2018), the current distribution of A. pirivorella does not include any of the 28 EU MS.

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Council Directive 2000/29/EC

Acrobasis pirivorella is listed in Council Directive 2000/29/EC. Details are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Acrobasis pirivorella in Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex II, Part A | Harmful organisms whose introduction into, and spread within, all member states shall be banned if they are present on certain plants or plant products. | |

| Section I | Harmful organisms not known to occur in the community and relevant for the entire community. | |

| (a) | Insects, mites and nematodes, at all stages of their development | |

| Species | Subject of contamination | |

| 5. | Numonia pyrivorella | Plants of Pyrus L., other than seeds, originating in non‐European countries |

3.3.2. Legislation addressing the hosts of Acrobasis pirivorella

Table 4.

Regulated hosts and commodities that may involve Acrobasis pirivorella in Annexes III of Council Directive 2000/29/EC

| Annex III, Part A | Plants, plant products and other objects the introduction of which shall be prohibited in all Member States | |

| Description | Country of origin | |

| Plants of Pyrus L. and their hybrids, intended for planting, other than seeds. | Without prejudice to the prohibitions applicable to the plants listed in Annex III A (9), where appropriate, non‐European countries, other than Mediterranean countries, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the continental states of the USA | |

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Host range

According to EPPO Global database and CABI Invasive species compendium, A. pirivorella is a monophagous species, feeding on Pyrus communis, and Pyrus spp., which are the major and the only one listed hosts. It attacks wild and cultivated pear plants.

3.4.2. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory?

Yes, fruits, cut branches and plants for planting (excluding seeds) are the main pathways. The latter is nowadays closed.

Although so far (18 July 2018) no records of interception of A. pirivorella exist in the Europhyt database, larvae and pupae of A. pirivorella could be present in fruit at harvest time. Therefore,

-

1

fruit imported from infested areas may constitute a pathway for this moth into the EU.

Moreover, as larvae overwinter in pear flower buds,

-

2

plants for planting (excluding seeds) are another pathway,

Finally, as oviposition may take place on flower buds and fruit

-

3

Cut branches containing either flower buds or fruit would be a third pathway

The plants for planting pathway can be considered as closed because present regulations ban the import of plants of Pyrus L. and their hybrids, intended for planting, other than seeds from the infested countries (see Section 3.3.2). However, the fruit (Table 5) and the cut branches pathways remain open.

Table 5.

EU‐28 import of fresh pears (in 100 kg) from countries with reported presence of Acrobasis pirivorella (2013–2017; Source: EUROSTAT Code: 080830) accessed on 16 July 2018

| Country of origin/year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China, People's Republic of | 103,518 | 63,020 | 94,541 | 113,845 | 112,007 |

| Japan | 1 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 57 |

| Korea, Democratic People's Republic of (North Korea) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Korea, Republic of (South Korea) | 450 | 1,156 | 815 | 909 | 1,227 |

| Russian Federation (Russia) | 471 | 1,871 | 721 | 52 | 12 |

| Taiwan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 |

3.4.3. Establishment

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory?

Yes, biotic and abiotic conditions are conducive for establishment of A. pirivorella in the EU

3.4.3.1. EU distribution of main host plants

All the known hosts of A. pirivorella are in the genus Pyrus, and pear orchards are common in the EU (Table 6)

Table 6.

Area of cultivation/production of pears (1,000 ha) in EU MS (Source: EUROSTAT accessed on 16 July 2018 and 21 September 2018)

| Country/Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union (current composition) | 120.40 | 117.01 | 117.80 | 117.26 | 116,24 |

| Belgium | 8.92 | 9.08 | 9.34 | 9.69 | 10.02 |

| Bulgaria | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| Czech Republic | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.71 |

| Denmark | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) | 1.93 | 1.93 | 1.93 | 1.93 | 2.14 |

| Estonia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ireland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greece | 4.82 | 4.97 | 4.95 | 4.08 | 3.78 |

| Spain | 24.24 | 23.64 | 22.88 | 22.55 | 21.89 |

| France | 5.35 | 5.36 | 5.37 | 5.30 | 5.25 |

| Croatia | 0.80 | 1.04 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| Italy | 31.53 | 30.15 | 30.86 | 32.29 | 31.73 |

| Cyprus | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Latvia | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Lithuania | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| Luxembourg | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Hungary | 3.00 | 2.89 | 2.88 | 2.88 | 2.87 |

| Malta | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Netherlands | 8.51 | 8.60 | 9.23 | 9.40 | 9.70 |

| Austria | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Poland | 9.50 | 9.20 | 9.20 | 7.49 | : |

| Portugal | 12.01 | 12.01 | 12.12 | 12.62 | 12.56 |

| Romania | 3.91 | 3.46 | 2.91 | 3.15 | 3.14 |

| Slovenia | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Slovakia | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Finland | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Sweden | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| United Kingdom | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

‘:’ data not available.

3.4.3.2. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

Optimal climatic conditions for survival and development of A. pirivorella are moderate rainfall and high humidity (MAF BioSecurity New Zealand, 2009). In fact, this species occurs in the Asian Far East (see Figure 1) in areas with humid climate types occurring in the EU as well (i.e., Köppen–Geiger Cfa, Dfa, Dfb climate types). Because in the areas of eastern Russia where A. pirivorella occurs, it can be found wherever pears are grown (CABI, 2018), and Pyrus spp. occurs across the EU, biotic and abiotic conditions are conducive for establishment of this moth in the EU.

3.4.4. Spread

Is the pest able to spread within the EU territory following establishment? How?

Yes. Although adult moths can fly over relatively short distances, movement of infested material (either fruit, plants, or branches) would be the main means of spread.

RNQPs: Is spread mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects?

Yes, spread is mainly via plants for planting.

The natural spread of A. pirivorella by adult flight is over relatively short distances. The main means of spread would be trade of planting material with infested buds (Shutova, 1977). Infested fruits may also carry the pest, however, its presence in fruits is relatively conspicuous; therefore, they could be easily detected and removed from the pathway.

In Far East Russia, A. pirivorella reportedly occurs wherever pears are grown. The natural spread by adult flight is over relatively short distances and the main means of spread is likely to be trade of planting material and unchecked infested fruits (Shutova, 1977).

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests’ introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes, the introduction of A. pirivorella would most probably have an economic impact in the EU.

RNQPs: Does the presence of the pest on plants for planting have an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting?

Yes, the presence of the pest on plants for planting has an economic impact on its intended use.

In the Far Eastern territories of Russia, it is considered as the most serious pest of cultivated pears. It is also of economic importance in Japan (EPPO Global database, 2018). The percentage infestation of fruit is 60–70% (Shutova, 1977).

3.6. Availability and limits of mitigation measures

Are there measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, extending the existing measures for plants for planting (see Section 3.3.2; i.e. sourcing plants from Pest Free Areas (PFA)) to the remaining pathways would mitigate the risk of entry, establishment and spread within the EU.

RNQPs: Are there measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting such that the risk becomes mitigated? 4

Yes, sourcing plants for planting from PFA would mitigate the risk.

3.6.1. Identification of additional measures

As a pest listed in Annex IIAI of 2000/29 EC, A. pirivorella is prohibited from entry into the EU only on Pyrus plants for planting. Therefore, the same measures could be applied to the remaining pathways (fruit and cut branches).

Additional control measures (i.e. those having a direct effect on pest abundance):

Production of plants for planting in isolation (i.e., greenhouse)

Conservation biological control

Bagging fruit/bait‐fruit

Proper disposal of infested material.

Supporting measures (i.e. those of organisational nature supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance):

Inspection

Laboratory testing

Sampling

Plant health inspection

Certified and approved premises for export

Establishment of demarcated areas and buffer zones

Surveillance.

3.6.1.1. Additional control measures

Potential control measures for the mitigation of risk from A. pirivorella are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Selected options for official control of hosts and pathways currently unregulated (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018). Official control is the effective enforcement of mandatory phytosanitary procedures with the objective of eradication or containment of quarantine pests or for the management of regulated non‐quarantine pests

| Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Control measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1175887 | As a pest that is a poor flyer and which does not disperse widely, growing plants in isolation is a measure to consider. Non‐orchard hosts (i.e. nurseries) could be grown within physical protection, e.g. a dedicated structure such as glass or plastic greenhouse | Entry |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181442 | Consignments intercepted with A. pirivorella spp. should be disposed of appropriately | Establishment |

| Biological control and behavioural manipulation (Work in progress, not yet available) |

The parasitic wasp Meteorus colon has been reported to parasitize A. pirivorella up to 57% (Komarova, 1984) The practice of bagging individual fruit is likely to prevent adult females from laying eggs on the fruit surface or the calyx. However, there is a period of up to four weeks from fruit set before fruit are bagged, during which eggs could be laid. Pyrus sp. nr. communis are not bagged (MAF Biosecurity New Zealand, 2009). In addition, fruits in certain trees remain unbagged and serve as bait‐fruits which are destroyed after infestation (Shutova, 1977) |

Entry |

3.6.1.2. Additional supporting measures

Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance. Potential supporting measures relevant to A. pirivorella are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Selected supporting measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance

| Information sheet (with hyperlink to information sheet if available) | Supporting measure summary | Risk component (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181430 | Imported host plants for planting, fruit and cut branches could be inspected for compliance from freedom of A. pirivorella | Entry, establishment, spread (within containment zones) |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181213 | Examination, other than visual, to determine if pests are present using official diagnostic protocols | Entry |

| Sampling (Work in progress, not yet available) | According to ISPM 31, it is usually not feasible to inspect entire consignments, so phytosanitary inspection is performed mainly on samples obtained from a consignment | Entry, establishment, spread |

| Phytosanitary certificate and plant passport (Work in progress, not yet available) | An official paper document or its official electronic equivalent, consistent with the model certificates of the IPPC, attesting that a consignment meets phytosanitary import requirements (ISPM 5) | Entry, establishment, spread |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180845 | Mandatory/voluntary certification/approval of premises is a process including a set of procedures and of actions implemented by producers, conditioners and traders contributing to ensure the phytosanitary compliance of consignments. It can be a part of a larger system maintained by a National Plant Protection Organization in order to guarantee the fulfilment of plant health requirements of plants and plant products intended for trade | Entry, establishment, spread |

| Certification of reproductive material (voluntary/official) (Work in progress, not yet available) | Reproductive material could be examined and certified free from A. pirivorella | Entry, establishment, spread |

| http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1180597 | Sourcing plants from a pest free place of production, site or area, surrounded by a buffer zone, would minimize the probability of spread into the pest free zone | Entry |

| Surveillance (Work in progress, not yet available) | ISPM 5 defines surveillance as an official process which collects and records data on pest occurrence or absence by survey, monitoring or other procedures | Establishment, spread |

3.6.1.3. Biological or technical factors limiting the feasibility and effectiveness of measures to prevent the entry, establishment and spread of the pest

The difficulty of identifying infested organs (buds, fruits) is considered low.

3.7. Uncertainty

By its very nature of being a rapid process, uncertainty is high in a categorisation. However, the uncertainties in this case are insufficient to affect the conclusions of the categorisation.

4. Conclusions

Considering the criteria within the remit of EFSA to assess its regulatory plant health status, A. pirivorella meets the criteria for consideration as a potential Union quarantine pest (it is absent from the EU, potential pathways exist and its establishment would cause an economic impact). Given that A. pirivorella is not known to occur in the EU, it fails to meet some of the criteria required for RNQP status. Table 9 provides a summary of the conclusions of each part of this pest categorisation.

Table 9.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column)

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union quarantine pest | Panel's conclusions against criterion in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding Union regulated non‐quarantine pest | Key uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1) | The identity of A. pirivorella is clearly established | The identity of A. pirivorella is clearly established | NA |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2) | The pest is not present in the EU territory | The pest is not present in the EU territory. Therefore, it fails this criterion to be regarded as a regulated non‐quarantine pest | NA |

| Regulatory status (Section 3.3) | The pest is currently listed in Annex IIAI of 2000/29 EC | There are no grounds to consider its status of quarantine pest to be revoked | NA |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4) | The pest has potential to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory. The main pathways are:

|

Spread is mainly via specific plants for planting, rather than via natural spread or via movement of plant products or other objects | NA |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5) | The pests’ introduction would most probably have an economic impact on the EU territory | The presence of the pest on plants for planting has an economic impact, as regards the intended use of those plants for planting | NA |

| Available measures (Section 3.6) | There are measures available to prevent the entry into, establishment within or spread of the pest within the EU (i.e. sourcing plants from PFA) | There are measures available to prevent pest presence on plants for planting (i.e. sourcing plants from PFA, PFPP) | NA |

| Conclusion on pest categorisation (Section 4) | All criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest are met with no uncertainties | The criterion of the pest being present in the EU territory, which is a prerequisite for consideration as a potential regulated non‐quarantine, is not met | NA |

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate | |||

Abbreviations

- DG SANTÉ

Directorate General for Health and Food Safety

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PFA

Pest Free Areas

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

protected zone

- RNQP

regulated non‐quarantine pest

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

Glossary

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 1995, 2017)

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2017)

- Establishment (of a pest)

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2017)

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2017)

- Measures

Control (of a pest) is defined in ISPM 5 (FAO 2017) as “Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population” (FAO, 1995). Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate Risk Reduction Options that do not directly affect pest abundance

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2017)

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2017)

- Protected zones (PZ)

A Protected zone is an area recognised at EU level to be free from a harmful organism, which is established in one or more other parts of the Union.

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2017)

- Regulated non‐quarantine pest

A non‐quarantine pest whose presence in plants for planting affects the intended use of those plants with an economically unacceptable impact and which is therefore regulated within the territory of the importing contracting party (FAO, 2017)

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO, 2017)

Suggested citation: EFSA Plant Health Panel , Bragard C, Dehnen‐Schmutz K, Di Serio F, Gonthier P, Jacques M‐A, Jaques Miret JA, Justesen AF, Magnusson CS, Milonas P, Navas‐Cortes JA, Parnell S, Potting R, Reignault PL, Thulke H‐H, Van der Werf W, Vicent Civera A, Yuen J, Zappalà L, Czwienczek E, Bali E and MacLeod A, 2018. Scientific Opinion on the pest categorisation of Acrobasis pirivorella . EFSA Journal 2018;16(10):5440, 20 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5440

Requestor: European Commission

Question number: EFSA‐Q‐2018‐00024

Panel members: Claude Bragard, Katharina Dehnen‐Schmutz, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Marie‐Agnès Jacques, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Panagiotis Milonas, Juan A. Navas‐Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Philippe Lucien Reignault, Hans‐Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen and Lucia Zappalà.

Adopted: 27 September 2018

Reproduction of the images listed below is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder:

Figure 1: © EPPO

Notes

Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community. OJ L 169/1, 10.7.2000, p. 1–112.

Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament of the Council of 26 October 2016 on protective measures against pests of plants. OJ L 317, 23.11.2016, p. 4–104.

Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. OJ L 31/1, 1.2.2002, p. 1–24.

See Section 2.1 on what falls outside EFSA's remit.

References

- Anonymous . Pear fruit moth. CRC 10010. Enhanced Risk Analysis Tools. Available online http://www.padil.gov.au/viewpestdiagnosticimages.aspx?id=512

- CABI , 2018. Invasive Species Compendium. CAB International, Wallingford, UK: Available online: http://www.cabi.org/isc [Google Scholar]

- EFSA PLH Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Health), Jeger M, Bragard C, Caffier D, Candresse T, Chatzivassiliou E, Dehnen‐Schmutz K, Grégoire J‐C, Jaques Miret JA, MacLeod A, Navajas Navarro M, Niere B, Parnell S, Potting R, Rafoss T, Rossi V, Urek G, Van Bruggen A, Van Der Werf W, West J, Winter S, Hart A, Schans J, Schrader G, Suffert M, Kertész V, Kozelska S, Mannino MR, Mosbach‐Schulz O, Pautasso M, Stancanelli G, Tramontini S, Vos S and Gilioli G, 2018. Guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment. EFSA Journal 2018;16(8):5350, 86 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPPO Global Database (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Global Database), 2018. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/NUMOPI/photos [accessed: 16 July 2018].

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 1995. ISPM (International standards for phytosanitary measures) No 4. Requirements for the establishment of pest free areas. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/en/publications/614/

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2004. ISPM (International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures) 21—Pest risk analysis of regulated non‐quarantine pests. FAO, Rome, 30 pp. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/sites/default/files/documents/1323945746_ISPM_21_2004_En_2011-11-29_Refor.pdf

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2013. ISPM (International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures) 11—Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests. FAO, Rome, 36 pp. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/sites/default/files/documents/20140512/ispm_11_2013_en_2014-04-30_201405121523-494.65%20KB.pdf

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2017. ISPM (International standards for phytosanitary measures) No 5. Glossary of phytosanitary terms. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/en/publications/622/

- Gibanov PK and Sanin YV, 1971. Lepidoptera ‐ pests of fruits in the Maritime Province. Zashchita Rastenii, 16, 41–43 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Komarova GF, 1984. The pear pyralid. Zashchita Rastenii No. 7, 36 (in Russian).

- MAF Biosecurity New Zealand , 2009. Import Risk Analysis: Pears (Pyrus bretschneideri, Pyrus pyrifolia, and Pyrus sp. nr. communis) fresh fruit from China Final. Wellington, New Zealand: 545 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Makaji N, 1965. An infestation habitat of the pear fruit moth. Abstract Annual Meeting Japanese Society of Applied Entomology and Zoology p. 32 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura S, 1900. Neue japanische Microlepidopteren. Entomologische Nachrichten, Berlin, 26, 193–199 (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Nuss M, Landry B, Mally R, Vegliante F, Tränkner A, Bauer F, Hayden J, Segerer A, Schouten R, Li H, Trofimova T, Solis MA, De Prins J and Speidel W, 2003. –2017. Global Information System on Pyraloidea. (Globales Informationsystem Zümsfer). Available online: http://www.pyraloidea.org/ [Accessed: 4 September 2018].

- Shutova NN, 1970. The pear moth Numonia pirivorella Mats In: Shutova NN. (ed.). Guide to quarantine pests, diseases and weeds. Kolos, Moscow, USSR; (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Shutova NN, 1977. The pear pyralid. Zashchita Rastenii, 9, 38 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Tabata J, Minamishima M, Sugie H, Fukumoto T, Mochizuki F and Yoshiyasu Y, 2009. Sex Pheromone Components of the Pear Fruit Moth, Acrobasis pyrivorella (Matsumura). Journal of Chemical Ecology, 35, 243–249. 10.1007/s10886-009-9597-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K, 2011. Pear fruit moth (Acrobasis pyrivorella). Pest and Diseases Image Library (updated: December, 2006). Available online: http://www.padil.gov.au/ (Accessed: 31 July 2018).