Abstract

BACKGROUND

Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) is implicated in the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), osteosarcoma (OS), and synovial sarcoma (SS). The authors conducted a multi-institutional phase 2 trial of the monoclonal antibody R1507 in patients with various subtypes of recurrent or refractory sarcomas.

METHODS

Eligibility criteria included age ≥2 years and a diagnosis of recurrent or refractory RMS, OS, SS, and other soft tissue sarcomas. Patients received a weekly dose of 9 mg/kg R1507 intravenously. The primary endpoint was the best objective response rate using World Health Organization criteria. Tumor imaging was performed every 6 weeks × 4 and every 12 weeks thereafter.

RESULTS

From December 2007 through August 2009, 163 eligible patients from 33 institutions were enrolled. The median patient age was 31 years (range, 7–85 years). Histologic diagnoses included OS (n = 38), RMS (n = 36), SS (n = 23), and other sarcomas (n = 66). The overall objective response rate was 2.5% (95% confidence interval, 0.7%−6.2%). Partial responses were observed in 4 patients, including 2 patients with OS, 1 patient with RMS, and 1 patient with alveolar soft part sarcoma. Four additional patients (3 with RMS and 1 with myxoid liposarcoma) had a ≥50% decrease in tumor size that lasted for <4 weeks. The median progression-free survival was 5.7 weeks, and the median overall survival was 11 months. The most common grade 3/4 toxicities were metabolic (12%), hematologic (6%), gastrointestinal (4%), and general constitutional symptoms (8%).

CONCLUSIONS

R1507 is safe and well tolerated but has limited activity in patients with recurrent or refractory bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Additional studies to help identify the predictive factors associated with clinical benefit in selected histologies such as RMS appear to be warranted.

Keywords: sarcoma, IGF-1R, SARC, insulin-like growth factor

INTRODUCTION

The outcome for patients with advanced or recurrent bone and soft tissue sarcomas has remained unchanged over the past 20 years.1–3 Effective standard agents for this population are limited. Newer, more effective, and less toxic therapies are urgently needed to improve the outcome of these patients.4–9 Genomic analysis of sarcomas has demonstrated that identification of targets and new therapeutics is particularly challenging.10

The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) is a tyrosine kinase receptor that belongs to the insulin receptor family. Activation of the receptor by its ligands IGF-1 and IGF-2 induces mitosis, protects cells against apoptosis, and helps maintain a transformed phenotype.11 Blocking the IGF-1R decreases tumor proliferation by inhibiting v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT)-mediated survival signals, and this response appears to be correlated with elevated IGF-1R levels.12

In addition to Ewing sarcoma (ES),13,14 the IGF-1R pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of other bone and soft tissue sarcomas, including rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), osteosarcoma (OS), synovial sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and solitary fibrous tumor.14 In RMS tumors and cell lines, IGF-2 functions as an autocrine and motility growth factor, and IGF-1R is 1 of the targets for the paired box 3-forkhead box O1A (PAX3-FOXOA1) fusion transcript of alveolar RMS.15,16

Antibodies against IGF-1R are safe and exhibit clinical activity in patients with recurrent ES and neuroendocrine tumors.17–21 R1507 (F. Hoffman-LaRoche, Basel, Switzerland) is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1)-type monoclonal antibody directed against the human IGF-1R, and the Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration (SARC) conducted a phase 2, multiarm study with this agent in multiple sarcoma subtypes. On the basis of preclinical data, the authors believed that OS, RMS, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and ES were important subtypes for inclusion in that trial. The outcomes of patients with ES have been reported separately.18 The current report details the results from a phase 2 study in patients with recurrent or progressive RMS, high-grade OS, synovial sarcoma, and other soft tissue sarcomas, including translocation-associated sarcomas like alveolar soft part sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, and myxoid liposarcoma, who received treatment with R1507.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility included a centrally histologically verified diagnosis of RMS, high-grade OS, synovial sarcoma, or other sarcoma; age >2 years; a life expectancy of at least 6 weeks; a Karnofsky/Lansky performance status >70%; bidimensionally measurable disease by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging; adequate bone marrow, liver, and renal function; and off chemotherapy for at least 3 weeks. Patients with central nervous system disease had no overt neurologic deficit, were off glucocorticoids for at least 4 weeks, and were off irradiation for >6 weeks. Patients were excluded if they had significant unrelated systemic illness, prior hypersensitivity reactions to monoclonal antibodies, treatment within 2 weeks of study entry with pharmacologic doses of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents, prior therapy with insulin-like growth factor inhibitors, poorly controlled diabetes, or a history of solid organ transplantation or other malignancy within 5 years.

Drug Administration

R1507 was administered intravenously at a dose of 9 mg/kg in 100 mL normal saline weekly (1 cycle) over 90 minutes during the initial infusion and, in the absence of any reactions, over 60 minutes during subsequent infusions.

Pharmacokinetic samples

Pharmacokinetic (PK) levels were quantified in serum using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (25 ng/mL was used as the lower limit of quantification). Blood samples (5 mL) were obtained before the first infusion; at the end of the infusion; and 24 hours, 72 to 96 hours, and 168 hours after the infusion in week 1. For graphic representation of the peak (Cmax) and trough (Cmin) values throughout the study, data were pooled from patients with this intense PK schedule and from patients whose PK samples were drawn with a less intense schedule during weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 just before dosing and at the end of the infusion.

Pharmacodynamic methods

Serum levels of total IGF-1 were analyzed by ELISA (DSL-10–5600 Active IGF-I ELISA Kit; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Jersey City, NJ). Samples were collected before the first dose and 24 hours after the infusion. Samples also were collected before the second, sixth, and 12th intravenous doses.

Clinical and Laboratory Investigations

Investigations included a baseline physical examination, complete blood count, chemistries, pregnancy test, electrocardiogram, antihuman antibodies, imaging for tumor measurements, and a positron emission tomography scan, which was repeated at day 9 and at week 18 for responders according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.22 Subsequent physical examinations, complete blood counts, and chemistries were performed weekly for 6 weeks and every 3 weeks thereafter. Tumor imaging was performed every 6 weeks 4 times and every 12 weeks thereafter. Tumor imaging was centrally reviewed.

Response to therapy was evaluated using WHO criteria.22 Off-study criteria included progressive disease, illness that prevented further administration of therapy, unacceptable adverse events, patient withdrawal from the study, a lapse >2 weeks since R1507 administration or missing ≥2 consecutive doses, death, loss to follow-up, or an unacceptable condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would prevent the patient from receiving further therapy.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoint was the best objective response, which was assessed separately within each of the different strata: OS, RMS, synovial sarcoma, and other sarcomas (alveolar soft part sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and myxoid liposarcoma). Progression-free survival at 18 weeks was a secondary objective. On the basis of the design of Green and Dahlberg,23 a maximum of 35 patients would be needed for the OS, RMS, and synovial sarcoma subtypes. The trial would stop if zero of 20 eligible patients achieved a response after the first stage; the probability of early termination was 12% if the true response rate was 10%. The null hypothesis would be rejected after the second stage if >7 of 35 patients responded. With a sample size of 35, the power to detect a 30% response rate was 87% with a 1-sided α of 2%. For “other sarcomas,” an analysis that considered each subtype separately was undertaken. A minimum of 10 eligible patients were accrued to each group, and the trial would stop if there were no responders in that subtype; otherwise, 10 more patients would be accrued to that subtype. The null hypothesis of a 5% response rate would be rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis of a 30% response rate if >3 of 20 patients responded. With a sample size of 20 eligible patients per cohort, the power to detect a 30% response rate was 94.5% with a 1-sided α of 1.5%. The probability of early termination was 60% if the true response rate was 5%.

R1507 serum-concentration time data were analyzed using noncompartmental analyses (WinNonlin release 5.2.1; Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, Calif). End-of-infusion samples were used to estimate the peak concentration (Cmax), and trough values (Cmin) were determined from predose samples. The following pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated: area under the concentration curve to the last measured time point (AUC at 0–168 hours), clearance, and volume of distribution. The dosing schedule relative to the half-life did not allow for appropriate estimation of the elimination half-life (t1/2).

RESULTS

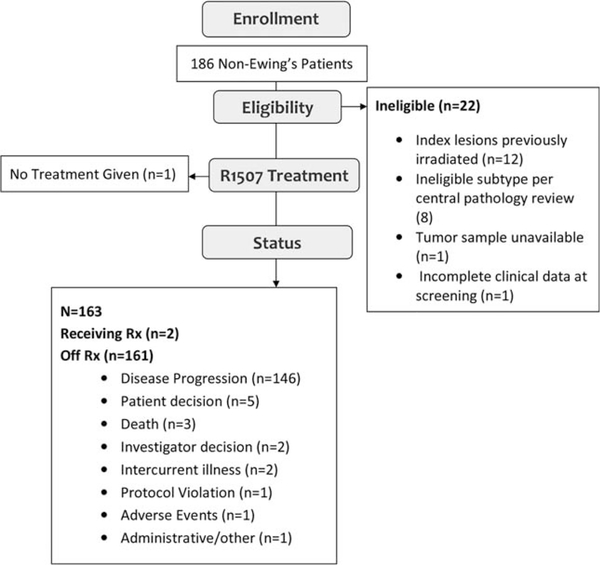

From December 31, 2007 through August 2009, 163 eligible patients from 33 institutions were enrolled and treated (Fig. 1). The median age at the time of enrollment was 31 years (range, 7–85 years). Overall, 30 patients (18%) were aged <18 years; and RMS and OS histologies accounted for the majority of these cases (Table 1).

Figure 1.

This is a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of patients registered on this study.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of 163 Eligible Patients

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age Median [range] | 31 [7–85] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 99 (60.7) |

| Female | 64 (38.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 110 (67) |

| Black | 15 (9) |

| Asian | 9 (6) |

| Other | 5 (3) |

| Not provided | 24 (15) |

| Performance status, % | |

| 70 | 16 (10) |

| 80 | 39 (24) |

| 90 | 74 (46) |

| 100 | 32 (20) |

| Histologic subtype | |

| Osteosarcoma | 38 (23) |

| Synovial sarcoma | 23 (14) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 36 (22) |

| Alveolar | 12 |

| Embryonal | 3 |

| Unknown | 21 |

| Other | 22 (14) |

| ASPS | 9 (5) |

| CCS | 12 (7) |

| DSRCT | 11 (7) |

| EMC/MLS | 12 (7) |

| No. of prior treatments | |

| ≤2 | 116 |

| ≥3 | 40 |

| Unknown | 7 |

Abbreviations: ASPS, alveolar soft part sarcoma; CCS, clear cell sarcoma; DSRCT, desmoplastic small found cell tumor; EMC, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma; MLS, myxoid liposarcoma.

Study Treatment

In total, 1813 doses were administered to 163 patients. The median number of treatment cycles was 6 (range, 1–108 cycles) per patient: 38 patients with OS received 2 to 108 cycles or more, 23 patients with synovial sarcoma received 2 to 59 cycles, 36 patients with RMS received 2 to 25 cycles, and 66 patients with other sarcomas received between 1 and 71 cycles. The median dose of R1507 per patient in mg/kg was 9.1 (range, 8.3–9.9 mg/kg).

Tumor Response and Clinical Outcome

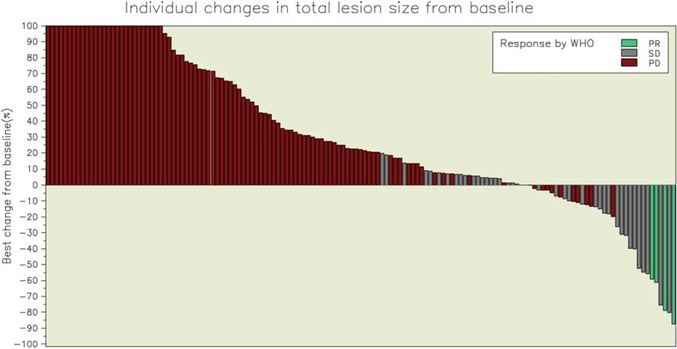

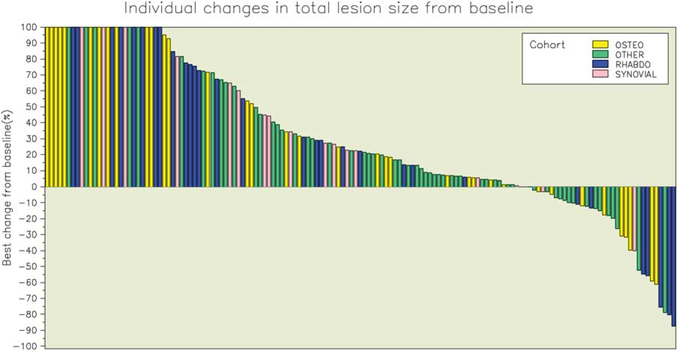

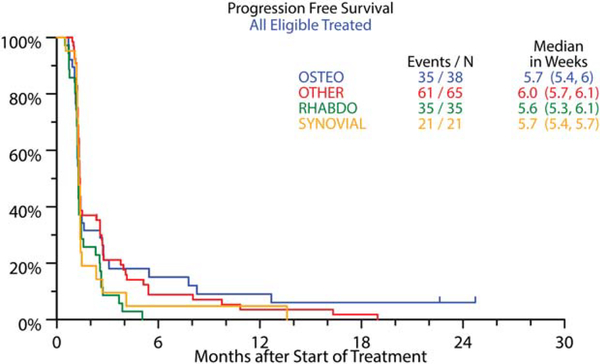

The overall objective response rate was 2.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7%−6.2%). Partial responses were observed in 4 patients, including 2 patients with OS, 1 patient with RMS (embryonal subtype), and 1 patient with an alveolar soft part sarcoma (Figs. 2, 3; Table 2). The median duration of response was 12 weeks (range, 12.3–24 weeks), and responses were observed at 6 weeks in 2 patients and at 12 weeks in the remaining 2 patients. Three patients with RMS (3 alveolar subtype) (Fig. 2) and 1 patient with myxoid liposarcoma had initial dramatic tumor shrinkage (≥50%) at week 6 but progressed by the time of the next assessment; and 2 additional patients (1 with RMS and 1 with myxoid liposarcoma) had partial responses at the week-18 disease assessments, but they were not confirmed at later assessments. Stable disease was observed in 26% of patients, including approximately one-third of patients in the other sarcoma category (41% of those with alveolar soft part sarcoma, 32% of those with extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, 19% of those with desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and 10% of those with myxoid liposarcoma), with a median duration of 6.5 weeks. For all eligible patients, median overall survival was 11.2 months (95% CI, 9.4–13.1 months), and progression-free survival was 5.7 weeks (95% CI, 5.6–5.9 weeks). Only 17% of patients (95% CI, 11.2%−22.6%) were progression-free at 12 weeks, and 7% (95% CI, 3.4%−11.4%) were progression-free at 24 weeks. The progression-free survival rates for patients with different histologies are depicted in Figure 4. There were 22 patients (10 with OS, 7 with other sarcomas, 4 with synovial sarcoma, and 1 with RMS) who were alive more than 2 years after enrollment on the protocol. These patients received a median of 10 doses of R1507 (range, 5–108 doses). One patient was still receiving therapy after 175 weeks of treatment. There was no correlation between response to therapy at week 12 and progression-free survival.

Figure 2.

The best individual changes in total lesion size from baseline are illustrated for all sarcoma types. WHO indicates World Health Organization classification; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 3.

The best individual changes from baseline are illustrated according to sarcoma type. OSTEO indicates osteosarcoma; RHABDO, rhabdomyosarcoma.

TABLE 2.

Best Response by Histologic Subtype Among 163 Eligible Patients

| No. of Patients (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best Response | OS, n = 38 | SS, n = 23 | RMS, n = 36 | Other, n = 66 | Total, n = 163a |

| Partial response | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 (2) |

| Stable disease | 10 | 4 | 6 | 22 | 42 (26) |

| Progressive disease | 26 | 17 | 26 | 40 | 109 (67) |

| Not evaluable/inadequate assessment | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 (5) |

Abbreviations: OS, osteosarcoma; RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma; SS, synovial sarcoma.

Note that percentages have been rounded up.

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival for all eligible patients. Values in parentheses are the 95% confidence interval for median progression-free survival in weeks. OSTEO indicates osteosarcoma; RHABDO, rhabdomyosarcoma.

Pharmacokinetics

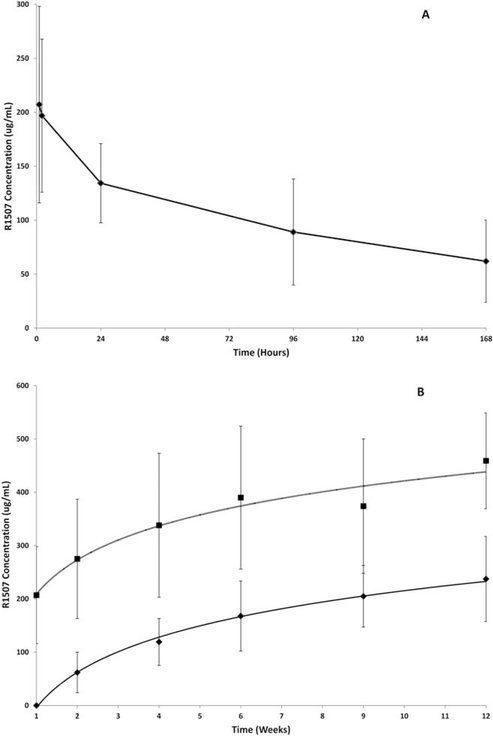

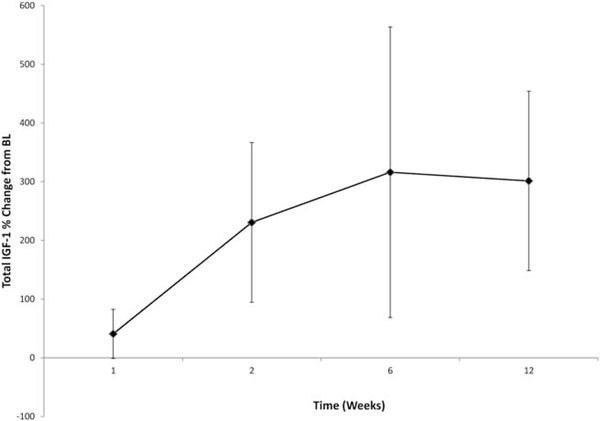

Figure 5A illustrates the mean concentration time profile observed after the first 9-mg/kg weekly dose. R1507 concentrations decreased to reach a mean trough (Cmin) value of 62 μg/mL within the first dosing interval. On the basis of the first dose, mean ± standard deviation Cmax values of 216.8 ± 90.8 μg/mL, an AUC from 0 to 168 hours of 17,329 ± 9682 μg*hour/mL, a volume of distribution of 56.2 ± 17.8 L/kg, and a clearance of 8.5 ± 2.5 mL per day per kg were consistent with previously described R1507 PK studies.18,20 These PK parameters were determined using data from 40 patients, and the interpatient variability (coefficient of variation percentage) ranged from 30% to 42%. Both Cmax and Cmin values increased over the course of 12 weeks, and there was some evidence of a PK plateau after 6 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5B).These results are consistent with estimates of a previously reported long elimination half-life.20 The observations of the respective Cmin and Cmax values were made by using all patients who had data available, including N = 155 and 142 patients (week 1), respectively; 144 and 140 patients (week 2), respectively; 139 and 37 patients (week 4), respectively; 108 and 106 patients (week 6), respectively; 13 and 12 patients (week 9), and 42 and 35 patients (week 12), respectively. Percentage changes in total IGF-1 levels from baseline are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Changes in R1507 concentrations are illustrated. (A) The mean concentration time profile observed after the first weekly dose is shown. (B) Peak values (Cmax) (top horizontal line) and trough values (Cmin) (bottom horizontal line) increased over the course of 12 weeks with some evidence for a pharmacokinetic plateau after 6 weeks of treatment. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviations.

Figure 6.

The total percentage change in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) from baseline (BL) is illustrated in weeks.

Prognostic Factors

Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified that an IGF-1 level >110 ng/mL, a Karnofsky performance status >90%, older age at diagnosis, and a diagnosis of OS were associated with longer survival (Table 3, Fig. 4). Among 92 patients who had samples available for analysis at week 6 of therapy, there were no significant associations between levels or changes in total IGF-1 and clinical outcome.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Results for Overall Survival

| Multivariate Analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No./Total No. (%) | HR [95% CI] | P |

| Total IGF-1 ≥110 ng/mL at baseline | 118/135 (87) | 0.35 [0.20–0.62] | <.001 |

| Age at randomization | 135 (100) | 0.99 [0.97–1.00] | .020 |

| Osteosarcoma | 32/135 (24) | 0.57 [0.35–0.93] | .025 |

| KPS ≥90 | 88/135 (65) | 0.64 [0.42–0.97] | .035 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; KPS, Karnofsky performance status.

P values were determined using the Wald chi-square test in Cox regression.

Toxicities

In total, 91 patients experienced adverse events related to R1507, including 37 grade 1 events, 37 grade 2 events, 15 grade e events, and 2 grade 4 events. The most common R1507-related adverse events included fatigue (n = 33), nausea (n = 23), hyperglycemia (n = 15), and muscle spasms (n = 14). The most common grade 3 and 4 toxicities related to treatment were hyperglycemia (n = 4), dehydration (n = 3), and fatigue (n = 3) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Grade 3 and 4 Toxicity Events

| No. of Events |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total Grade ≥3 |

| Hematologic | |||

| Hemoglobin | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Laboratory abnormalities | |||

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Blood calcium decreased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase increased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperglyemia | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Hyponatremia | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Transaminases increased | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nonhematologic | |||

| Adrenal hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Asthenia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Back pain | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Dehydration | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nausea | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Maximum grade of any adverse event | 15 | 2 | 17 |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest reported prospective, multi-institutional study in bone and soft tissue sarcomas investigating the activity of a monoclonal antibody against the IGF-1R. Our study demonstrates that R1507 has limited activity in selected bone and soft tissue sarcomas and has a very favorable toxicity profile. In our study, 2.5% of patients experienced a measurable objective response as defined by WHO criteria, and only 17% were progression-free at 12 weeks, suggesting that the drug is inactive in these patient groups.24 However, a careful analysis of our data demonstrates that patients with RMS and OS may benefit from this therapy, and further study appears to be warranted in these subgroups (Fig. 2). The results of other published sarcoma trials using various monoclonal antibodies directed against IGF-1R are provided in Table 5.17,18,21,25–27

TABLE 5.

Published Results of Single Agent Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor Antibody Studiesa

| Agent (Reference) | Sarcoma Type | No. of Patients | Response: CR/PR | Biomarker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMG 497 (Olmos 201017) | Ewing, n = 16; synovial sarcoma, n = 5; DSRCT, n = 3; RMS, n = 2; fibrosarcoma, n = 2; myxoid sarcoma, n = 1 | 29 | Ewing, n = 2 | None |

| R1507 (Pappo 201118) | Ewing | 15 | 11 | Pretreatment and wk-6 total IGF-1 ≥110 ng/mL and a higher percentage increase of total IGF-1 from baseline to wk 6 predicted improved overall survival |

| Figitumumab (Juergens 201121) | Ewing, n = 123; osteosarcoma, n = 11; other, n = 4 | 138 | Ewing, n = 16 | High pretreatment free IGF-1 levels and total circulating IGF-1 were correlated with improved survival |

| Ganitumab (Tap 201225) | Ewing, n = 22; DSRCT, n = 16 | 38 | Ewing, n = 1; DSRCT, n = 1 | No relation between baseline IGF-1 and response |

| Dalotuzumab (Atzori 201126) | Ewing, n = 6; bone, n = 3 | 80 | 0 | Mean serum IGF-1 and IGF-BP3 levels increased after 5 wks of therapy, and treatment with dalotuizumab decreased the mean H-scores of IGF-1R in tumor and skin as well as pS6, pEIF4G, pMAK, EGFR, and Ki-67 |

| Cixutumab (Schoffski 201327) | RMS, n = 17; LMS, n = 22; adipocytic sarcoma, n = 37; synovial sarcoma, n = 17; Ewing, n = 17 | 111 | Ewing, n = 1; adipocytic sarcoma, n = 1 |

Abbreviations: DSRCT, desmoplastic small round cell tumor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IGFBP3, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; pEIF4G, phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma; pS6, phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6; RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma.

It is unclear why clinical responses were disappointingly low in our study. From our data, we were able to identify distinct subsets of patients that responded differently to IGF-1R–blocking therapy. The first group, which accounted for about 66% of patients, failed to exhibit a clinical response and progressed after a median of 2 cycles of R1507. It is possible that these patients have low levels of IGF-1R receptors,13 as recently demonstrated in ES cell lines by flow cytometry,28 and/or intrinsic expression or activation of macrophage-stimulating 1 receptor (MST1R). MST1R is a met proto-oncogene (MET)-related protein tyrosine kinase expressed in 48% of embryonal RMS and 71% of alveolar RMS. It modulates IGF-1R activity through the activation of ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) and may be a mechanism of innate resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapy.29 Additional resistance mechanisms may include constitutively up-regulated phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT) and/or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) secondary to the up-regulation of TORC2 (CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2) or a compensatory switch that favors IGF-II/IR-A dependency.30,31 Laboratory studies to elucidate these potential mechanisms are currently being performed on collected tissue specimens. Approximately 25% of our patients in the other sarcoma category had stable disease; however this was short lived (about 6 weeks) and included patients who had tumors that are known for their indolent clinical course, such as alveolar soft part sarcoma. Thus, the clinical benefit of this agent in this patient group could not be accurately assessed. A small group of patients had dramatic and sustained responses to R1507. This group likely had tumors that expressed high levels of IGF-1R receptors, lacked insulin receptor expression, had low levels of BCL-2, and also may have had decreased or absent expression of MST1R.21,32,33 A third group of patients had transient responses followed by resistance, suggesting the subsequent activation of alternative signaling pathways, which may include platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), v-erb-b2 avian erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2 (ERBB2), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), or MET.34–36 The latter mechanism of resistance is being recognized increasingly in a variety of tumor systems.37 Finally, the low response rates observed in our trial could have been related to inadequate drug dosing, because R1507 tumor biodistribution reportedly was correlated with tumor response in a panel of sarcoma xenografts using immuno–single-photon emission computed tomography imaging.38 The initial dose of 9 mg/kg per week was based on phase 1 studies that demonstrated a median half-life of 8 to 10 days in concentrations that exceeded 20 μg/mL,20 a concentration expected to saturate >90% of the IGF-1 receptors. Our current data are consistent with previous observations.18 However, ongoing PK studies suggest that high serum peak levels are more important and that dosing 27 mg/kg every 3 weeks appears to be more efficacious than the same dose divided weekly.18

The median overall survival in our patients was 13 months. This is similar to the survival reported in other studies for patients with advanced RMS, OS, and synovial sarcomas, emphasizing the critical need for effective therapies in the relapsed setting. Although R1507 is much less toxic than more the traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies used for these malignancies in the refractory setting, the response rates are lower.

Although the company has halted development of this drug, we believe that IGF-1R inhibitors may play a role in the treatment of selected sarcomas, particularly ES and RMS. However, it will be crucial to incorporate the development of both positive and negative prospective biomarkers into future clinical studies. For example, some tumors have undetectable levels of the IGF-1R on their surface, which would lead to a prediction that such patients would be unlikely to respond to IGF-1R blockade. Thus, the incorporation of a sensitive, quantitative assay for the expression of the IGF-1R as a selection criteria would likely lead to an increase in response rates. Unfortunately, the presence of the IGF-1R does not positively predict a response to anti-IGF-1R therapy, and predictive biomarkers of response clearly are needed. This probably will require prospective biopsies before entry on study so that tumors can be studied for activation of signaling pathways that hopefully could identify predictors of response. Furthermore, such analysis also may help to identify the potential activation of resistance pathways, leading to rational combination therapies that could include mTOR inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, and/or Src family kinase inhibitors.39–43

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

This study was supported by F. Hoffman-LaRoche. Dr. Maki was supported by a grant from F. Hoffman-LaRoche. Dr. Chow was supported by a grant from the Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Dr. Ladanyi reports personal fees from NanoString Technologies, Puma Biotechnology, and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Chawala reports research funding from Amgen, CytRx, Threshold, Berg Pharma, and GSK outside the submitted work and has acted as a consultant to Amgen, Roche, CytRx, Threshold, GSK, and Berg Pharma. Dr. Maki reports personal fees from Hoffman-LaRoche outside the submitted work. Dr. Grippo, Dr. Dall, and Dr. Maki are employed by Hoffman-LaRoche Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pappo AS, Devidas M, Jenkins J, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant vincristine, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support in children and adolescents with advanced-stage nonrhabdomyosarcomatous soft tissue sarcomas: a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4031–4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: Children’s Oncology Group Study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5182–5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, HYPERLINK “/csr/1975_2010/”http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl M, Ranft A, Paulussen M, et al. Risk of recurrence and survival after relapse in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempf-Bielack B, Bielack SS, Jurgens H, et al. Osteosarcoma relapse after combined modality therapy: an analysis of unselected patients in the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group (COSS). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2625–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Oosterhuis JW, et al. Prognostic factors for the outcome of chemotherapy in advanced soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 2,185 patients treated with anthracycline-containing first-line regimens—a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor BS, Barretina J, Maki RG, Antonescu CR, Singer S, Ladanyi M. Advances in sarcoma genomics and new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:541–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atzori F, Traina TA, Ionta MT, Massidda B. Targeting insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor in cancer therapy. Target Oncol. 2009;4:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao L, Yu Y, Darko I, et al. Addiction to elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor and initial modulation of the AKT pathway define the responsiveness of rhabdomyosarcoma to the targeting antibody. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8039–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Wan X, Helman LJ. Targeting IGF-1R in the treatment of sarcomas: past, present and future. Bull Cancer. 2009;96:E52–E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maki RG. Small is beautiful: insulin-like growth factors and their role in growth, development, and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28: 4985–4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minniti CP, Helman LJ. IGF-II in the pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma: a prototype of IGFs involvement in human tumorigenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;343:327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao L, Yu Y, Bilke S, Walker RL, Mayeenuddin LH, Azorsa DO, et al. Genome-wide identification of PAX3-FKHR binding sites in rhabdomyosarcoma reveals candidate target genes important for development and cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6497–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olmos D, Postel-Vinay S, Molife LR, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody figitumumab (CP-751871) in patients with sarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma: a phase 1 expansion cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappo AS, Patel SR, Crowley J, et al. R1507, a monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, in patients with recurrent or refractory Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: results of a phase II Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4541–4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolcher AW, Sarantopoulos J, Patnaik A, et al. Phase I, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of AMG 479, a fully human monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor receptor 1. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5800–58007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurzrock R, Patnaik A, Aisner J, et al. A phase I study of weekly R1507, a human monoclonal antibody insulin-like growth factor-I receptor antagonist, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2458–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juergens H, Daw NC, Geoerger B, et al. Preliminary efficacy of the anti-insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor antibody figitumumab in patients with refractory Ewing sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4534–4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green SJ, Dahlberg S. Planned versus attained design in phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 1992;11:853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Glabbeke M, Verweij J, Judson I, Nielsen OS. Progression-free rate as the principal end-point for phase II trials in soft-tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tap WD, Demetri G, Barenette P, et al. Phase II study of ganitumab, a fully human anti-type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor antibody, in patients with metastatic Ewing family tumors or desmoplastic small round cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atzori F, Tabernero J, Cervantes A, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of dalotuzumab (MK-0646), an anti-insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6304–6312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoffski P, Adkins D, Blay JY, et al. An open-label, phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy and safety of the anti-IGF-1R antibody cixutumumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma or Ewing family of tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49:3219–3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Neill A, Shah N, Zitomersky N, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor as a therapeutic target in Ewing sarcoma: lack of consistent upregulation or recurrent mutation and a review of the clinical trial literature [serial online]. Sarcoma 2013:450478, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potratz JC, Saunders DN, Wai DH, et al. Synthetic lethality screens reveal RPS6 and MST1R as modifiers of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor activity in childhood sarcomas. Cancer Res. 2010; 70:8770–8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbiah V, Naing A, Brown RE, et al. Targeted morphoproteomic profiling of Ewing’s sarcoma treated with insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) inhibitors: response/resistance signatures [serial online]. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garofalo C, Mancarella C, Grilli A, et al. Identification of common and distinctive mechanisms of resistance to different anti-IGF-IR agents in Ewing’s sarcoma. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1603–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayeenuddin LH, Yu Y, Kang Z, Helman LJ, Cao L. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor antibody induces rhabdomyosarcoma cell death via a process involving AKT and Bcl-x(L). Oncogene. 2010;29: 6367–6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scotlandi K, Manara MC, Serra M, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor system components in Ewing’s sarcoma and their association with survival. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang F, Hurlburt W, Greer A, et al. Differential mechanisms of acquired resistance to insulin-like growth factor-I receptor antibody therapy or to a small-molecule inhibitor, BMS-754807, in a human rhabdomyosarcoma model. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7221–7231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham J, Prajapati SI, Nishijo K, et al. Evasion mechanisms to Igf1r inhibition in rhabdomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10: 697–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katayama R, Khan TM, Benes C, et al. Therapeutic strategies to overcome crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancers harboring the fusion oncogene EML4-ALK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7535–7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puzanov I, Burnett P, Flaherty KT. Biological challenges of BRAF inhibitor therapy. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleuren ED, Versleijen-Jonkers YM, van de Luijtgaarden AC, et al. Predicting IGF-1R therapy response in bone sarcomas: immune-SPECT imaging with radiolabeled R1507. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17: 7693–7703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurmasheva RT, Dudkin L, Billups C, Debelenko LV, Morton CL, Houghton PJ. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-targeting antibody, CP-751871, suppresses tumor-derived VEGF and synergizes with rapamycin in models of childhood sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7662–7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang F, Greer A, Hurlburt W, Han X, Hafezi R, Wittenberg GM, et al. The mechanisms of differential sensitivity to an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor (BMS-536924) and rationale for combining with EGFR/HER2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naing A, Kurzrock R, Burger A, Gupta S, Lei X, Busaidy N, et al. Phase I trial of cixutumumab combined with temsirolimus in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6052–6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeung C, Ngo V, Grohar P, et al. Loss-of-function screen in rhabdomyosarcoma identifies CRKL-YES as a critical signal for tumor growth. Oncogene. 2013;32:5429–5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz GK, Tap WD, Qin LX, et al. Cixutumumab and temsirolimus for patients with bone and soft-tissue sarcoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]