Abstract

Background

Digital health programs assist patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to better manage their disease. Technological and adoption barriers have been perceived as a limitation.

Objective

The aim of the research was to evaluate a digital quality improvement pilot in Medicare-eligible patients with COPD.

Methods

COPD patients were enrolled in a digital platform to help manage their medications and symptoms as part of their routine clinical care. Patients were provided with electronic medication monitors (EMMs) to monitor short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) use passively and a smartphone app to track use trends and receive feedback. Providers also had access to data collected via a secure website and were sent email notifications if a patient had a significant change in their prescribed inhaler use. Providers then determined if follow-up was needed. Change in SABA use and feasibility outcomes were evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Results

A total of 190 patients enrolled in the pilot. At 3, 6, and 12 months, patients recorded significant reductions in daily and nighttime SABA use and increases in SABA-free days (all P<.001). Patient engagement, as measured by the ratio of daily active use to monthly active use, was >90% at both 6 and 12 months. Retention at 6 months was 81% (154/190). Providers were sent on average two email notifications per patient during the 12-month program.

Conclusions

A digital health program integrated as part of standard clinical practice was feasible and had low provider burden. The pilot demonstrated significant reduction in SABA use and increased SABA-free days among Medicare-eligible COPD patients. Further, patients readily adopted the digital platform and demonstrated strong engagement and retention rates at 6 and 12 months.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; telemedicine; quality improvement, feasibility; nebulizers and vaporizers; health services

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more than 65 million adults worldwide and is expected to become the third leading cause of death by 2030 [1]. COPD is associated with progressive loss of lung function and has significant impacts on both physical and mental well-being [2].

The use of inhaled long-acting muscarinic antagonist, long-acting beta-agonists alone or in combination with a long-acting muscarinic antagonists, or an inhaled corticosteroid–long-acting beta-agonist combination has been associated with improved symptom control and decreases in exacerbations associated with COPD [3]. Short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) are prescribed to manage acute symptoms. Knowledge of actual SABA use and its signal of increased risk may be used to adjust medication regimens and identify worsening symptoms and determine risk or occurrence of an exacerbation [4-6]. Historically, information on patient use of SABA has been self-reported, leading to challenges of recall bias through incorrect recollection or fabrication [7-9].

To address the burden and morbidity of COPD [10,11], novel approaches for disease management are warranted [12]. Web-based self-management, smartphone apps, electronic medication monitors, and text-based interventions have been used to track, automate, and provide real-time feedback on medication use and clinical status. These digital health interventions have demonstrated success for chronic respiratory diseases including asthma and COPD [13-17]; however, these programs may be limited by nonengagement and attrition [18,19].

Emerging research suggests that digital health programs integrating providers [20] or human coaches may improve clinical outcomes, rates of engagement, and retention [21,22]. However, there has been little effort to engage COPD patients in these programs due to perceived challenges with patient age and comfort with technology [18,23,24], as well as perceived increases in provider burden. This analysis aimed to determine the feasibility of integrating a digital quality improvement pilot in a clinical setting to improve outcomes in a COPD Medicare population.

Methods

Recruitment and Eligibility

Patients were recruited from three JenCare Senior Medical Center clinics in Louisville, Kentucky, from December 2015 to December 2016. JenCare clinics are managed care facilities that provide high-touch care to low- to moderate-income Medicare-eligible patients. Inclusion criteria were kept broad to include as many patients as possible in the quality improvement pilot. Patients with a physician diagnosis of COPD, using a sensor-compatible SABA medication, and fluent in English or Spanish were eligible for enrollment. An in-person enrollment process was led by clinical team members and two respiratory therapists. Eligible patients were required to accept Propeller Heath’s Terms of Use [25] prior to participation, which permits the use of aggregated, de-identified data in analyses. This analysis was determined to be exempt by the Copernicus Independent Review Board.

Study Design

Patients were provided with an electronic medication monitor (EMM; Propeller Health) that attached to their compatible SABA (Figure 1). The EMM was used to objectively monitor the date and time of SABA use. The EMM was paired via Bluetooth to a smartphone, which transmitted the information to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant servers. Patients without smartphones received a wireless hub to transmit EMM data passively. Lost or malfunctioning EMMs and hubs were replaced.

Figure 1.

Electronic medication monitor that captures inhaler medication use.

The EMM provided is part of a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared digital health platform comprising a mobile app, Web dashboards, and short message service and email modalities [13,14,26]. Patients had access to a Web or mobile platform that promoted self-management with information about their SABA use trends, potential environmental triggers, and guidelines-based education [3]. Further, because this was a quality improvement pilot, there was no formal retention plan such that patients were not required to have a final visit or last sensor sync. No incentives were provided.

Health Care Providers and Electronic Notifications

Patients authorized their health care providers to view collected data and summary reports through a secure Web dashboard. This information could be used to inform clinical treatment such as medication adjustments or early intervention at the sign of increasing SABA use. In addition, at-risk notifications were sent to providers if a patient was considered at increased risk for an exacerbation (defined as use of ≥10 SABA puffs in a 24-hour period or SABA use above the patient’s personal baseline level for two or more consecutive days). Based on these notifications, providers could determine appropriate follow-up with a patient via telephone or an in-person visit as needed. A respiratory therapist assisted patients with technical questions by phone and in person.

Feasibility Outcomes

We evaluated patient retention at 3, 6, and 12 months (defined as an EMM sync with at least 3, 6, and 12-month data points, respectively). Syncs demonstrate that the EMM is capable of collecting and transmitting data via a smartphone or hub. While syncs do not require actuation of the medication, they do require that the patient maintain the digital platform. For example, patients must ensure the hub remains charged and connected to an outlet and that the EMM is transferred to any refilled inhaler prescriptions. As such, to evaluate patient engagement, we examined the proportion of days that a sync was recorded at 3, 6, and 12 months. We also compared the percentage of daily active users with the percentage of monthly active users to determine level of daily engagement. Finally, we assessed provider notification burden by averaging the number of at-risk notifications sent to the provider per patient over the 12-month program.

Short-Acting Beta-Agonist Use

Change in mean SABA use and percentage of SABA-free days was assessed at 3, 6, and 12 months. The date, time, and number of SABA puffs were recorded as mean puffs per day. Nighttime SABA use was calculated as a subcategory of daily use, defined as use between 10:00 pm and 6:00 am. Percentage of SABA-free days were calculated as the percentage of days (unique 24-hour periods) in which a patient did not use their SABA inhaler.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were completed for the feasibility outcomes at 3, 6, and 12 months. SABA use outcome analyses compared the change in the mean number of SABA uses per day, mean number of nighttime SABA uses, and percentage of SABA-free days from baseline to specified end points. The baseline period was defined as week 1 (days 1-7), with day 1 as the first EMM sync. We evaluated outcomes at baseline and compared against three end points: 3 months (week 13), 6 months (week 26), and 12 months (week 52) among those patients with sufficient follow-up. To account for potential biases due to attrition during the 12-month study period, we calculated stabilized inverse probability of attrition weights for each participant with 3 months of data, conditional on age, race, gender, season of enrollment, smartphone or hub use, baseline SABA use, and syncing using logistic regression [27]. We then estimated changes in SABA use parameters from baseline to 3, 6, and 9 months using attrition-weighted longitudinal, mixed-effects linear models adjusting for age, race, gender, and season of enrollment. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Population

A total of 190 patients enrolled in the digital quality improvement pilot. Patients were primarily white (99/190, 52.1%) or African American (85/190, 44.7%), female (124/190, 65.3%), and over age 60 years (153/190, 80.6%) with a mean age of 68.0 (SD 9.2) years (Table 1). Almost all patients transmitted data using the wireless hub device (184/190, 96.8%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics (n=190).

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

| Age in years |

|

|

|

|

40-49 | 1 (0.5) |

|

|

50-59 | 36 (18.9) |

|

|

60-69 | 67 (35.3) |

|

|

70 and older | 86 (45.3) |

| Gender, female | 124 (65.3) | |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

White | 99 (52.1) |

|

|

African American | 85 (44.7) |

|

|

Other | 4 (2.1) |

|

|

Unknown | 2 (1.1) |

| Device type |

|

|

|

|

Hub | 184 (96.8) |

|

|

Smartphone | 6 (3.2) |

Feasibility Outcomes

Patient retention was 90.5% (172/190) at 3 months, 81.0% (154/190) at 6 months, and 63.1% (120/190) at 12 months (Table 2). There were no significant differences in age, race, gender, baseline SABA use, or sync history between those patients who completed 12 months and those who did not (Table 3). The percentage of daily active users to monthly active users remained above 90% for all three end points. Similarly, the mean proportion of days patients synced at 3, 6, and 12 months was 91%, 90%, and 88%, respectively. Providers were sent 397 at-risk notifications over 12 months, a mean of 2.1 notifications per patient.

Table 2.

Feasibility and process outcomes.

| Characteristics | Value | |

| Patient retention, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

3 months | 172 (90.5) |

|

|

6 months | 154 (81.0) |

|

|

12 months | 120 (63.1) |

| Patient engagement (proportion of days with at least one sync), % |

|

|

|

|

3 months | 91 |

|

|

6 months | 90 |

|

|

12 months | 88 |

|

|

Daily active user/monthly active user | 90.5 |

| Provider at-risk alerts, n (mean per patient) | 397 (2.1) | |

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with complete and noncomplete follow-up at 12 months.

| Characteristic | Patients who completed 12 months (n=120) | Patients who did not complete 12 months (n=70) | P value | |

| Age, n (%) | — | — | .38 | |

|

|

40-49 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | — |

|

|

50-59 | 18 (15) | 17 (24) | — |

|

|

60-69 | 44 (37) | 24 (34) | — |

|

|

70 and older | 57 (48) | 29 (41) | — |

| Race, n (%) | — | — | .35 | |

|

|

White | 61 (51) | 38 (54) | — |

|

|

African American | 56 (47) | 29 (41) | — |

|

|

Other | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | — |

|

|

Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | — |

| Female, n (%) | 82 (68) | 42 (60) | .31 | |

| SABAa at baseline, puffs/day, mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.3) | 4.0 (1.6) | .18 | |

| Days with at least one sync at baseline, % | 94 | 88 | .09 | |

aSABA: short-acting beta-agonist.

Change in Short-Acting Beta-Agonist Use

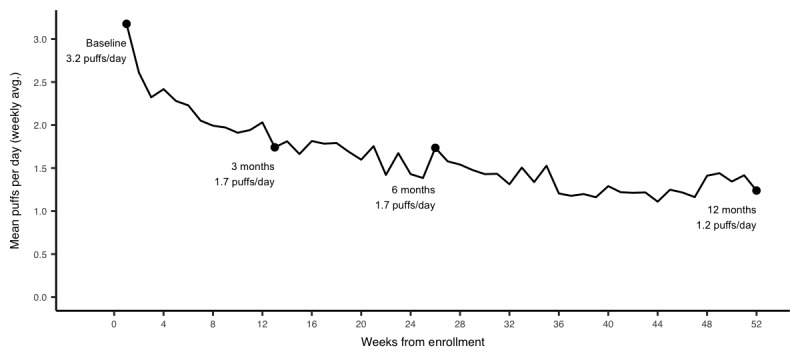

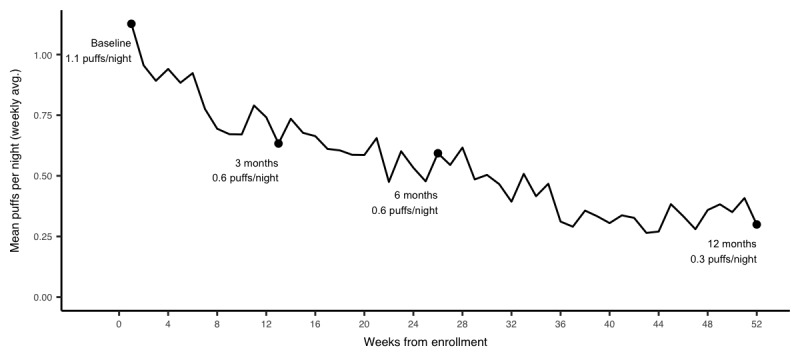

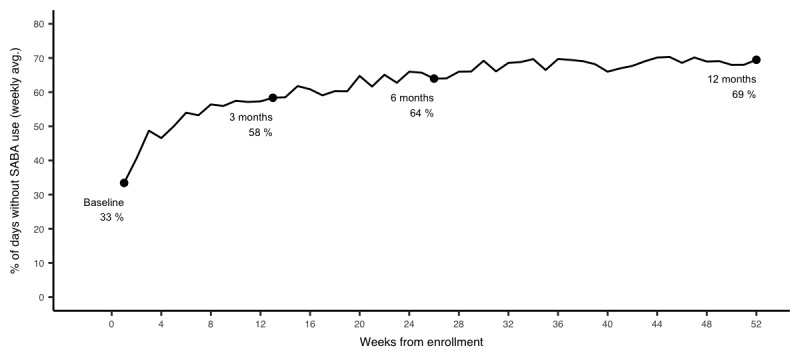

In crude analyses, decreases in mean SABA use and nighttime SABA use and increases in SABA-free days were observed over the study period in patients with 3, 6, and 12 months of follow-up (Multimedia Appendix 1). After accounting for potential biases due to attrition and adjusting for potential confounders, mean SABA use, nighttime SABA use, and SABA-free days were 3.2 puffs per day, 1.1 puffs per day, and 33%, respectively. SABA use decreased on average by 1.4 (95% CI –1.6 to –1.2), 1.6 (95% CI –1.7 to–1.2), and 1.9 (95% CI –2.1 to –1.7) puffs per day, from baseline to 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (Figure 2). Similarly, nighttime SABA use decreased by 0.5 (95% CI –0.6 to –0.4), 0.5 (95% CI –0.7 to –0.4), and 0.8 (95% CI –0.9 to –0.7) and the weekly proportion of SABA-free days increased by 25% (95% CI 22 to 28), 31% (95% CI 27 to 34), and 36% (95% CI 33 to 39) points from baseline to 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Attrition-weighted and adjusted mean daily short-acting beta-agonist use at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Figure 3.

Attrition-weighted and adjusted nighttime short-acting beta-agonist use at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Figure 4.

Attrition-weighted and adjusted percent of short-acting beta-agonist–free days at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study evaluated the feasibility of a clinically integrated digital quality improvement pilot in a Medicare-eligible COPD population. Patients demonstrated significant improvements from baseline to 3, 6, and 12 months for reduced daily and nighttime SABA use and an increased percentage of SABA-free days. Further, this study demonstrated that a digital health program was feasible in this COPD population.

Providers had access to the patient’s clinical status and real-time use of SABA. Providers received at-risk notifications at the patient level to alert them to increased SABA use and provide the opportunity for earlier intervention. While we did not formally record changes to medication regimens, other studies have shown that real-time identification of increased SABA use enables more timely provider intervention and may result in lower exacerbation rates and acute health care utilization including hospitalizations and emergency department visits [4,5]. Additional randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm this effect.

Comparison With Prior Work

Previous studies have demonstrated that engagement rates for digital health applications may peak around 3 months and decline rapidly thereafter [28,29], with approximately 10% of participants engaging at 6 months [30]. In this study, we saw 81% retention and 90% of days with a sync at 6 months. The three recruitment centers are characterized by high-touch, engaged providers. It is possible that the clinical improvement and engagement in this study may be explained in part by the frequency and quality of the provider engagement. For example, a previous meta-analysis exploring the impact of provider communication on patient engagement found a positive correlation between provider feedback and medication adherence rates [31]. Additional research shows that active provider engagement may improve retention rates [32,33]. Patient-provider data sharing and transparency may also improve outcomes and engagement through shared decision-making [15,34].

Digital health interventions may also increase provider burden [23]. However, this analysis suggests that passively tracking medication use and integrating this information into a comprehensive clinical care model may result in stronger patient engagement without excessive provider burden. For example, only 2.1 at-risk notifications were sent on average per patient throughout the 12-month study period. Future studies should address provider burden and satisfaction in a more robust manner.

EMMs may reduce patient burden. Measures of medication use in clinical studies frequently rely on self-report, placing the burden on patients and increasing the likelihood of recall bias [28]. By objectively and passively collecting medication use data and transmitting it to the provider, both patient burden and reporting accuracy may be improved.

Limitations

This study is limited, in part, by its design as a single-arm study and regression to the mean for SABA use should be considered. Further, controller medication use was not tracked due to a noncompatible formulary, limiting the opportunity for controller medication adherence promotion and possible impact on SABA use. It is also possible that patients used additional SABA inhalers without attaching an EMM. Measurement of engagement and clinical outcomes was limited and future programs should consider more definitive measures a priori. Finally, factors beyond the EMMs and platform may have contributed to the observed outcomes, and future randomized studies are needed to confirm the findings.

Conclusion

This quality improvement pilot demonstrates that a digital health program with integrated clinical care is feasible in a Medicare-eligible population of COPD patients. The results demonstrated strong retention rates at 12 months, with reduced daily and nighttime SABA use and more SABA-free days. With the increasing medical resources being used for COPD treatment [10], novel approaches for disease management are warranted [12].

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the JenCare providers who participated: Drs Ali, Anderson, Gross, Kiriakos, and Mahin, as well as Shannon Goeldi, Melissa Williams, and Jennifer Morgan of Propeller Health for assistance with patient enrollment and outreach. We would also like to acknowledge the broad network of local partners that made the broader AIR Louisville program possible and thank the City of Louisville and all participants for supporting the program. Additional thanks to the Institute for Healthy Air, Water, and Soil and the Community Foundation of Louisville. We thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for its generous funding (grant number #71592) and guidance. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Abbreviations

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- EMM

electronic medication monitor

- SABA

short-acting beta-agonist

Appendix

Changes in short-acting beta-agonist use.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JC receives salary and equity as an employee of ChenMed. SJ-F and TS are employees of JenCare. LK, MT, MB, RG, KH, DVS, and DS receive salary as employees of Propeller Health. DVS and MB have patents pending related to their work at Propeller Health, but not directly related to this manuscript. VC declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. [2019-09-16]. Chronic respiratory diseases: burden of COPD http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en.

- 2.Putcha N, Drummond MB, Wise RA, Hansel NN. Comorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, influence on outcomes, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Aug;36(4):575–591. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556063. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26238643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Chen R, Decramer M, Fabbri LM, Frith P, Halpin DMG, López VMV, Nishimura M, Roche N, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Sin DD, Singh D, Stockley R, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Agustí A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Mar 01;195(5):557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan VS, Gylys-Colwell I, Locke E, Sumino K, Nguyen HQ, Thomas RM, Magzamen S. Overuse of short-acting beta-agonist bronchodilators in COPD during periods of clinical stability. Respir Med. 2016 Dec;116:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0954-6111(16)30094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumino K, Locke ER, Magzamen S, Gylys-Colwell I, Humblet O, Nguyen HQ, Thomas RM, Fan VS. Use of a remote inhaler monitoring device to measure change in inhaler use with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2018 Jun;31(3):191–198. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2017.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharafkhaneh A, Altan AE, Colice GL, Hanania NA, Donohue JF, Kurlander JL, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Altman PR. A simple rule to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who may need treatment reevaluation. Respir Med. 2014 Sep;108(9):1310–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.07.002. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0954-6111(14)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourbeau J, Bartlett SJ. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax. 2008 Sep;63(9):831–838. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.086041. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18728206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rand C. "I took the medicine like you told me, doctor": self-report of adherence with medical regimens. In: Stone A, editor. The Science of Self-Report: Implications for Research and Practice. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004 Mar;42(3):200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khakban A, Sin DD, FitzGerald JM, McManus BM, Ng R, Hollander Z, Sadatsafavi M. The projected epidemic of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations over the next 15 years. a population-based perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Dec 01;195(3):287–291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1162PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jinjuvadia C, Jinjuvadia R, Mandapakala C, Durairajan N, Liangpunsakul S, Soubani AO. Trends in outcomes, financial burden, and mortality for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the United States from 2002 to 2010. COPD. 2017 Dec;14(1):72–79. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1199669. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27419254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged ≥ 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015 Jan;147(1):31–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett MA, Humblet O, Marcus JE, Henderson K, Smith T, Eid N, Sublett JW, Renda A, Nesbitt L, Van Sickle D, Stempel D, Sublett JL. Effect of a mobile health, sensor-driven asthma management platform on asthma control. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 Dec;119(5):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant RK, Inamdar R, Quade RC. Effectiveness of population health management using the propeller health asthma platform: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(3):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? BMJ. 1999 Sep 18;319(7212):780–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.780. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/10488014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster JM, Usherwood T, Smith L, Sawyer SM, Xuan W, Rand CS, Reddel HK. Inhaler reminders improve adherence with controller treatment in primary care patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Dec;134(6):1260–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKibben S, De Simoni A, Bush A, Thomas M, Griffiths C. The use of electronic alerts in primary care computer systems to identify the excessive prescription of short-acting beta-agonists for people with asthma: a systematic review. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2018 Apr 16;28(1):14. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0080-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29662064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabak M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, Hermens H, Vollenbroek-Hutten M. A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:935–944. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S60179. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S60179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, A'Court C, Hinder S, Fahy N, Procter R, Shaw S. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Nov 01;19(11):e367. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merchant R, Szefler SJ, Bender BG, Tuffli M, Barrett MA, Gondalia R, Kaye L, Van Sickle D, Stempel DA. Impact of a digital health intervention on asthma resource utilization. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0209-0. https://waojournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40413-018-0209-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennison L, Morrison L, Lloyd S, Phillips D, Stuart B, Williams S, Bradbury K, Roderick P, Murray E, Michie S, Little P, Yardley L. Does brief telephone support improve engagement with a web-based weight management intervention? Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e95. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3199. http://www.jmir.org/2014/3/e95/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yardley L, Ware LJ, Smith ER, Williams S, Bradbury KJ, Arden-Close EJ, Mullee MA, Moore MV, Peacock JL, Lean MEJ, Margetts BM, Byrne CD, Hobbs RFD, Little P. Randomised controlled feasibility trial of a web-based weight management intervention with nurse support for obese patients in primary care. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:67. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-67. http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/11//67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard S, Lang A, Sharples S, Shaw D. What are the pros and cons of electronically monitoring inhaler use in asthma? A multistakeholder perspective. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2016;3(1):e000159. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000159. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27933181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson M, Perrin A. Tech adoption climbs among older adults. Washington: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2017. [2019-09-16]. https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2017/05/PI_2017.05.17_Older-Americans-Tech_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Propeller Health: User Agreement. 2018. [2019-01-02]. https://my.propellerhealth.com/terms-of-service.

- 26.Van Sickle D, Magzamen S, Truelove S, Morrison T. Remote monitoring of inhaled bronchodilator use and weekly feedback about asthma management: an open-group, short-term pilot study of the impact on asthma control. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055335. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, Napravnik S, Eron JJ. Selection bias due to loss to follow up in cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–97. doi: 10.1097/ede.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birnbaum F, Lewis D, Rosen RK, Ranney ML. Patient engagement and the design of digital health. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Jun;22(6):754–756. doi: 10.1111/acem.12692. doi: 10.1111/acem.12692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farago P. App engagement: the matrix reloaded. 2012. Oct 22, [2019-09-16]. http://flurrymobile.tumblr.com/post/113379517625/app-engagement-the-matrix-reloaded.

- 30.Dorsey ER, Yvonne CY, McConnell MV, Shaw SY, Trister AD, Friend SH. The use of smartphones for health research. Acad Med. 2017 Feb;92(2):157–160. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zolnierek KBH, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009 Aug;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19584762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryant J, McDonald VM, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R, Paul C, Melville J. Improving medication adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Respir Res. 2013 Oct 20;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-109. https://respiratory-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1465-9921-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farmer A, Williams V, Velardo C, Shah SA, Yu L, Rutter H, Jones L, Williams N, Heneghan C, Price J, Hardinge M, Tarassenko L. Self-management support using a digital health system compared with usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017 May 03;19(5):e144. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7116. http://www.jmir.org/2017/5/e144/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tapp H, Shade L, Mahabaleshwarkar R, Taylor YJ, Ludden T, Dulin MF. Results from a pragmatic prospective cohort study: shared decision making improves outcomes for children with asthma. J Asthma. 2017 May;54(4):392–402. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1227333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Changes in short-acting beta-agonist use.