Abstract

The Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) provides a scientific opinion re‐evaluating the safety of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR, E 476) used as a food additive. In 1978, the Scientific Committee for Food (SCF) established an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 7.5 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day for PGPR. PGPR is hydrolysed in the gut resulting in the liberation of free polyglycerols, polyricinoleic acid and ricinoleic acid. Di‐ and triglycerol are absorbed and excreted unchanged in the urine; long‐chain polyglycerols show lower absorption and are mainly excreted unchanged in faeces. Acute oral toxicity of PGPR is low, and short‐term and subchronic studies indicate PGPR is tolerated at high doses without adverse effects. PGPR (E 476) is not of concern with regard to genotoxicity or carcinogenicity. The single reproductive toxicity study with PGPR was limited and was not an appropriate study for deriving a health‐based guidance value. Human studies with PGPR demonstrated that there is no indication of significant adverse effect. The Panel considered a 2‐year combined chronic toxicity/carcinogenicity study for determining a reference point and derived a no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) for PGPR (E 476) of 2,500 mg/kg bw per day, the only dose tested. Therefore, the Panel concluded that the present data set give reason to revise the ADI of 7.5 mg/kg bw per day allocated by SCF to 25 mg/kg bw per day. Exposure estimates did not exceed the ADI of 25 mg/kg bw per day and a proposed extension of use would not result in an exposure exceeding this ADI. The Panel recommended modification of the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

Keywords: polyglycerol polyricinoleate, food additive, E 476, emulsifier, PGPR, CAS Registry Number 68936‐89‐0

Summary

Following a request from the European Commission, the Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) was asked to re‐evaluate the safety of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR; E 476) when used as a food additive. In addition, following an application dossier for a modification of the conditions for use of polyglycerol polyricinoleate, the European Commission requested the Panel evaluate the safety of the proposed extension of use.

The Panel was not provided with a newly submitted dossier for the re‐evaluation of the food additive and based its assessment on previous evaluations and reviews, additional literature that came available since then and the data available following a public call for data. The Panel noted that not all original studies on which previous evaluations were based were available for re‐evaluation by the Panel.

PGPR (E 476) is authorised as a food additive in the European Union (EU) according to Annex II and Annex III of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 and specific purity criteria have been defined in the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012.

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) evaluated PGPR in 1969 and in 1974 (JECFA, 1969, 1974) and established on the basis of a reproductive toxicity study in rats an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 0–7.5 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day.

The Scientific Committee for Food (SCF) established an ADI of 7.5 mg/kg bw per day for PGPR (SCF, 1978). PGPR was also evaluated by the Nordic Council of Ministers (TemaNord, 2002). It was concluded that ‘the toxicological data available to JECFA in 1973 or to SCF in 1977 did not include all the data, which are normally required for an ADI to be set for a food additive. However, later data confirm the safety of the substance within the ADI, and taken together with the limited exposure, there seems to be no need for a re‐evaluation’.

Since PGPR is a mixture of reaction products formed by the esterification of polyglycerols with condensed castor oil fatty acids, relevant information on existing authorisations and evaluations concerning these moieties have also been examined.

JECFA (1979) considered that castor oil had a long history of use as a laxative and aside from these effects, has been used apparently without harm. JECFA concluded on this ADI on the basis that at levels of exposure that cause laxation, castor oil might be expected to inhibit the absorption of fat soluble nutrients – notably vitamins A and D – and therefore, use of castor oil should be kept well below levels where absorption would be inhibited. JECFA considered that at doses of 4 g in adults (approximately 70 mg/kg bw per day), absorption appears to be complete and may be considered as a ‘no‐effect level’ in man. In the absence of adequate long‐term relevant toxicological studies, a conservative margin of safety was applied to derive an ADI of 0–0.7 mg/kg bw per day.

The SCF (2003) allocated an ADI of 0.7 mg/kg bw per day for ricinoleic acid. In its opinion, the SCF endorsed the JECFA ADI of 0–0.7 mg/kg bw per day for castor oil and considered that ricinoleic acid, as the main constituent of castor oil, should be allocated with the same numerical ADI.

The EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) considered the safety of ricinoleic acid as an acceptable previous cargo for edible fats and oils and concluded that it was not of toxicological concern nor was there any concern regarding possible allergenicity. No reaction products of toxicological concern were known or anticipated.

The safety of polyglycerol for use in food contact materials has been reviewed by the EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF). The CEF Panel concluded that polyglycerol does not raise a safety concern for the consumer if the substance is only to be used as plasticiser at a maximum use level of 6.5% w/w in polymer blends of aliphatic‐aromatic polyesters in contact with all types of food for any time at room temperature and below.

The ANS Panel re‐evaluated the safety of glycerol (E 422) when used as a food additive and concluded that there is no need for a numerical ADI and no safety concern regarding the use of glycerol (E 422) as a food additive. However, it also concluded that the manufacturing process of glycerol should not allow the production of glycerol (E 422) that contains genotoxic and carcinogenic residuals at a level which would result in a margin of exposure below 10,000.

From the available in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) studies with oral dosing in rats, the Panel considered that PGPR was hydrolysed in the gut resulting in the liberation of free polyglycerols, polyricinoleic acid and free ricinoleic acid after oral dosing in rats. The absorption of polyglycerols depends on the chain length, e.g. di‐ and triglycerol were nearly completely absorbed and excreted unchanged in the urine, whereas long‐chain polyglycerols like decaglycerol showed lower absorption rates and were mainly excreted unchanged in the faeces. No metabolism and no accumulation of polyglycerols were observed. The Panel considered that castor oil was hydrolysed in the gastrointestinal tract to glycerol and ricinoleic acid and the ricinoleic acid moiety was absorbed and subjected to similar distribution, metabolism and excretion as orally administered ricinoleic acid. Ricinoleic acid itself was shown to be readily incorporated into the fatty acid pathway, and after oral dosing for up to 30 days, an accumulation of hydroxy acids by 5% of fatty acids in fat tissue was noted. An analysis of adipose tissue indicated an occurrence of shorter chain hydroxyl acids other than ricinoleic acid. No studies were available for polyricinoleic acid.

The Panel considered the acute oral toxicity of PGPR and of polyglycerols is low.

The Panel considered that the increases in liver weight observed in short‐term and subchronic toxicity studies were adaptive – not an adverse – response of the liver to the large amount of PGPR administered to the animals (often a very high single dose level, e.g. 16,200 mg/kg bw per day). The Panel further considered that diets containing up to 10% castor oil was not associated with toxicity to any specific organ, organ system, or tissue and identified no observed adverse effect levels (NOAELs) of 20,000 and 9,000 mg/kg bw per day for castor oil in mice and rats, respectively, the highest doses tested. No studies were available for ricinoleic acid, polyricinoleic acid and polyglycerols.

No genotoxicity data on PGPR and polyglycerol were available; however, data were available on castor oil and sodium ricinoleate. Overall, the Panel considered that PGPR (E 476) was not of concern with regard to genotoxicity.

The Panel considered that the increases in liver weight observed in chronic and carcinogenicity studies were an adaptive – not an adverse – response of the liver and that PGPR did not demonstrate any carcinogenic effects in the available studies at doses up to 7,500 and 4,500 mg/kg bw per day in mice and rats, respectively, the only doses tested. No studies were available for ricinoleic acid, castor oil, polyricinoleic acid and polyglycerols. Overall, the Panel considered a combined 2‐year combined chronic toxicity/carcinogenicity study as the critical study for determining a reference point because this combination of studies examined the most extensive range of endpoints including histopathological examinations of reproductive organs. The Panel considered that the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) for PGPR (E 476) from this study was 2,500 mg/kg bw per day, the only dose tested.

No data on the developmental toxicity of PGPR, ricinoleic acid, castor oil, polyricinoleic acid and polyglycerols were available. The single reproductive toxicity study with PGPR was considered to have limitations in study design (not comparable with a two‐generation reproductive toxicity study); in that the number of animals initially pregnant in the test group was low (n = 13); in that there was infection in the animals; in that there was reduced breeding in the second generation and in the limited reporting of the study. The Panel noted that this reproductive study was used by the SCF (and by JECFA) to derive the current ADI of 7.5 mg/kg bw per day. However, the Panel considered that due to the above limitations, this study was not an appropriate study for deriving a health‐based guidance value for PGPR.

The Panel considered that human studies with PGPR demonstrated that there is no indication of significant adverse effect after exposure up to 10,000 mg per day (equivalent to 142.8 mg/kg bw per day) over 3 weeks. In clinical studies with castor oil used at a dose of 960 mg/kg bw, only minor gastrointestinal discomfort was reported. No human studies were available for ricinoleic acid, polyricinoleic acid and polyglycerols.

The Panel considered that although the only reproductive toxicity study had limitations and no data were available regarding potential developmental toxicity of PGPR, an additional uncertainty factor was not required because the oral 2‐year combined chronic toxicity/carcinogenicity study in rats included histopathology of reproductive organs and no changes were observed. In addition, at markedly higher doses (up to 13,000 mg/kg bw per day in mice and 16,200 mg/kg bw per day in rats), no adverse effects were observed in other chronic studies in rats and a carcinogenicity study in mice. Furthermore, no adverse effects were observed in the limited reproductive toxicity study.

Considering the available toxicological database and based on the absence of adverse effects in an oral 2‐year combined chronic toxicity/carcinogenicity study from which a NOAEL of 2,500 mg PGPR/kg bw per day, the highest dose tested, was identified and applying an uncertainty factor of 100, the Panel derived an ADI of 25 mg PGPR/kg bw per day. Therefore, the Panel considered that the available data set give reason to revise the ADI of 7.5 mg/kg bw per day allocated by SCF in 1978, to a new ADI of 25 mg/kg bw per day.

The Panel concluded that PGPR (E 476) as a food additive at the permitted or reported use and use levels would not be of safety concern considering that exposure estimates did not exceed the ADI of 25 mg/kg bw per day in any of the exposure scenarios for any population group both at the mean and the 95th percentile.

The Panel also calculated the exposure to PGPR (E 476) considering an additional use in emulsified sauces, including mayonnaise, using the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario. The Panel also concluded that the proposed extension of use of PGPR (E 476) at 4,000 mg/kg in the food category emulsified sauces would not result in an exposure to PGPR (E 476) that exceeds the ADI.

The Panel recommended that:

the maximum limits for the impurities of toxic elements (lead, mercury and arsenic) in the EC specification for PGPR (E 476) should be revised in order to ensure that PGPR (E 476) as a food additive will not be a significant source of exposure to those toxic elements in food;

a maximum limit for active ricin should be included in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476);

a maximum limit for 3‐monochloropropane‐1,2‐diol (3‐MCPD) should be included in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476);

given that during the manufacturing processes of glycerol, potential impurities of toxicological concern could be formed, limits for such impurities should be included in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476);

given that during the manufacturing processes of polyglycerols, genotoxic impurities – e.g. epichlorohydrin and glycidol – could be present, limits for such impurities should be included in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476);

an analytical method for the determination of actual PGPR (E 476) content in food should be developed.

1. Introduction

The present opinion deals with the re‐evaluation of the safety of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR) (E 476) when used as a food additive.

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the European Commission

1.1.1. Background as provided by the European Commission

1.1.1.1. Re‐evaluation of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) as a food additive

Regulation (EC) No 1333/20081 of the European Parliament and of the Council on food additives requires that food additives are subject to a safety evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) before they are permitted for use in the European Union (EU). In addition, it is foreseen that food additives must be kept under continuous observation and must be re‐evaluated by EFSA.

For this purpose, a programme for the re‐evaluation of food additives that were already permitted in the European Union before 20 January 2009 has been set up under Regulation (EU) No 257/20102. This Regulation also foresees that food additives are re‐evaluated whenever necessary in the light of changing conditions of use and new scientific information. For efficiency and practical purposes, the re‐evaluation should, as far as possible, be conducted by group of food additives according to the main functional class to which they belong.

The order of priorities for the re‐evaluation of the currently approved food additives should be set on the basis of the following criteria: the time since the last evaluation of a food additive by the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) or by EFSA, the availability of new scientific evidence, the extent of use of a food additive in food and the human exposure to the food additive taking also into account the outcome of the Report from the Commission on Dietary Food Additive Intake in the EU3 of 2001. The report ‘Food additives in Europe 20004’ submitted by the Nordic Council of Ministers to the Commission, provides additional information for the prioritisation of additives for re‐evaluation. As colours were among the first additives to be evaluated, these food additives should be re‐evaluated with a highest priority.

In 2003, the Commission already requested EFSA to start a systematic re‐evaluation of authorised food additives. However, as a result of adoption of Regulation (EU) 257/2010 the 2003 Terms of References are replaced by those below.

1.1.1.2. Extension of use for polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) in emulsified sauces

The use of food additives is regulated under the European Parliament and Council Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives. Only food additives that are included in the Union list, in particular in Annex II to that Regulation, may be placed on the market and used in foods under the conditions of use specified therein. Moreover, food additives should comply with the specifications as referred in Article 14 of that Regulation and laid down in Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/20125.

Polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) is an emulsifier, which is authorised for use as a food additive in the Union. Since, polyglycerol polyricinoleate was permitted in the Union before 20 January 2009, it belongs to the group of food additives which will be subject to a new risk assessment by EFSA, in line with the provisions of the Regulation (EU) No 257/2010, which sets up the programme for the re‐evaluation of food additives, the re‐evaluation of polyglycerol polyricinoleate shall be completed by 31 December 2016.

The European Commission has received an application from the company EMULSAR SARL for a modification of the conditions for use of polyglycerol polyricinoleate. In particular, the applicant requests an extension of use for this additive in emulsified sauces, including mayonnaise (Food Category 12.6 of part E of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 133/2008). The maximum level requested by the applicant is of 4,000 mg/kg. The use of this emulsifier would allow lowering the fat content in emulsified sauces without modifying the organoleptic properties and appeal of the product.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference as provided by the European Commission

1.1.2.1. Re‐evaluation of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) as a food additive

The Commission asks EFSA to re‐evaluate the safety of food additives already permitted in the Union before 2009 and to issue scientific opinions on these additives, taking especially into account the priorities, procedures and deadlines that are enshrined in the Regulation (EU) No 257/2010 of 25 March 2010 setting up a programme for the re‐evaluation of approved food additives in accordance with the Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on food additives.

1.1.2.2. Extension of use for polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) in emulsified sauces

The European Commission requests EFSA to provide a scientific opinion on the safety of the proposed extension of use for polyglycerol polyricinoleate in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1331/20086 establishing a common authorisation procedure for food additives, food enzymes and food flavourings.

Taking into account that EFSA is currently working on a new risk assessment for polyglycerol polyricinoleate, it is proposed that EFSA incorporates in that risk assessment the assessment of the safety of the proposed extension of use for polyglycerol polyricinoleate. In particular, EFSA is requested to prepare an additional exposure assessment scenario that incorporates the proposed extension of use for this additive in emulsified sauces (food category 12.6 of part E of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008), which a maximum level of 4,000 mg/kg.

1.2. Information on existing evaluations and authorisations

PGPR (E 476) is an authorised food additive in the EU according to Annex II and Annex III of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 and specific purity criteria have been defined in the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/20127.

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) evaluated PGPR in 1969 and in 1974 (JECFA, 1969, 1974) and established on the basis of a reproductive toxicity study in rats an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 0–7.5 mg/kg bw per day.

The Scientific Committee for Food (SCF) established an ADI of 7.5 mg/kg bw per day for PGPR (SCF, 1978). PGPR was also evaluated by the Nordic Council of Ministers (TemaNord, 2002). It was concluded that ‘the toxicological data available to JECFA in 1973 or to SCF in 1977 did not include all the data, which are normally required for an ADI to be set for a food additive. However, later data confirm the safety of the substance within the ADI, and taken together with the limited exposure, there seems to be no need for a re‐evaluation’.

Since PGPR is a mixture of reaction products formed by the esterification of polyglycerols with condensed castor oil fatty acids, relevant information on existing authorisations and evaluations concerning these moieties has also been examined.

JECFA considered that castor oil had a long history of use as a laxative and aside from these effects, has been used apparently without harm (JECFA, 1979). JECFA considered that at doses of 4 g in adults (approximately 70 mg/kg bw per day), absorption of castor oil appears to be complete and may be considered as a ‘no‐effect level’ in man. In the absence of adequate long‐term relevant studies, a conservative margin of safety (MoS) was applied to derive an ADI of 0–0.7 mg/kg bw per day. JECFA concluded on this ADI on the basis that at levels of exposure that cause laxation, castor oil might be expected to inhibit the absorption of fat soluble nutrients – notably vitamins A and D – and therefore, use of castor oil should be kept well below levels where absorption would be inhibited.

The SCF allocated an ADI of 0.7 mg/kg bw per day for ricinoleic acid (SCF, 2003). In its opinion, the SCF endorsed the JECFA ADI of 0–0.7 mg/kg bw per day for castor oil and considered that ricinoleic acid, as the main constituent of castor oil, be allocated with the same numerical ADI.

The EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) considered the safety of ricinoleic acid as an acceptable previous cargo for edible fats and oils (EFSA CONTAM Panel, 2012a) and concluded that it was not of toxicological concern nor was there any concern regarding possible allergenicity. No reaction products of toxicological concern were known or anticipated.

The safety of polyglycerol for use in food contact materials has been reviewed by the EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF) (EFSA CEF Panel, 2013). The CEF Panel concluded that polyglycerol does not raise a safety concern for the consumer if the substance is only to be used as plasticiser at a maximum use level of 6.5% w/w in polymer blends of aliphatic‐aromatic polyesters in contact with all types of food for any time at room temperature and below.

The EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) re‐evaluated the safety of glycerol (E 422) and concluded that there is no need for a numerical ADI and no safety concern regarding the use of glycerol (E 422) as a food additive (EFSA ANS Panel, 2017). However, it was also concluded that the manufacturing process of glycerol should not allow the production of glycerol (E 422) that contains genotoxic and carcinogenic residuals at levels, which result in a MoS below 10,000.

Polyglyceryl‐10‐polyricinoleate, polyglyceryl‐3‐polyricinoleate, polyglyceryl‐4‐polyricinoleate and polyglyceryl‐5‐polyricinoleate are permitted in cosmetic products in the EU (European Commission database‐CosIng8).

Castor oil (PM Ref. No 14411 and 42880) is included in the Union list of authorised substances that may be intentionally used in the manufacture of plastic layers in plastic materials and articles (Annex I to Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/20119).

2. Data and methodology

2.1. Data

The Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) was not provided with a newly submitted dossier. EFSA launched public calls for data10 , 11 to collect information from interested parties.

The Panel based its assessment on information submitted to EFSA following the public calls for data, information from previous evaluations and additional available literature up to November 2016. Attempts were made at retrieving relevant original study reports on which previous evaluations or reviews were based; however, these were not always available to the Panel.

The EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database (Comprehensive Database12) was used to estimate the dietary exposure.

The Mintel's Global New Products Database (GNPD) is an online resource listing food products and compulsory ingredient information that should be included in labelling. This database was used to verify the use of PGPR (E 476) in food products.

2.2. Methodologies

This opinion was formulated following the principles described in the EFSA Guidance on transparency with regard to scientific aspects of risk assessment (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2009) and following the relevant existing guidance documents from the EFSA Scientific Committee.

The ANS Panel assessed the safety of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) as a food additive in line with the principles laid down in Regulation (EU) 257/2010 and in the relevant guidance documents: Guidance on submission for food additive evaluations by the SCF (2001).

When the test substance was administered in the feed or in the drinking water, but doses were not explicitly reported by the authors as mg/kg bw per day based on actual feed or water consumption, the daily intake was calculated by the Panel using the relevant default values as indicated in the EFSA Scientific Committee guidance document (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2012a) for studies in rodents or, in the case of other animal species, by JECFA (2000). In these cases, the daily intake is defined in the text as ‘equivalent to’. When in human studies in adults (aged above 18 years) the dose of the test substance administered was reported in mg/person per day, the dose in mg/kg bw per day was calculated by the Panel using a body weight of 70 kg as default for the adult population as described in the EFSA Scientific Committee Guidance document (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2012a).

Dietary exposure to polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) from its use as a food additive was estimated combining food consumption data available within the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database with the maximum permitted levels and/or reported use levels submitted to EFSA following a call for data. Different scenarios were used to calculate exposure (see Section 3.3.1). Uncertainties on the exposure assessment are identified and discussed.

3. Assessment

3.1. Technical data

3.1.1. Identity of the substance

PGPR (E 476) is a mixture of products formed by the esterification of polyglycerols with condensed castor oil fatty acids. According to the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012, the polyglycerol moiety is mainly composed of di‐, tri‐ and tetraglycerol with not more than 10% equal or higher than heptaglycerol. The castor oil fatty acids are mainly composed of ricinoleic acid (80–90%). Other components are oleic acid (3–8%), linoleic acid (3–7%), and stearic acid (0–2%) (Quest International, 1998 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 13]).

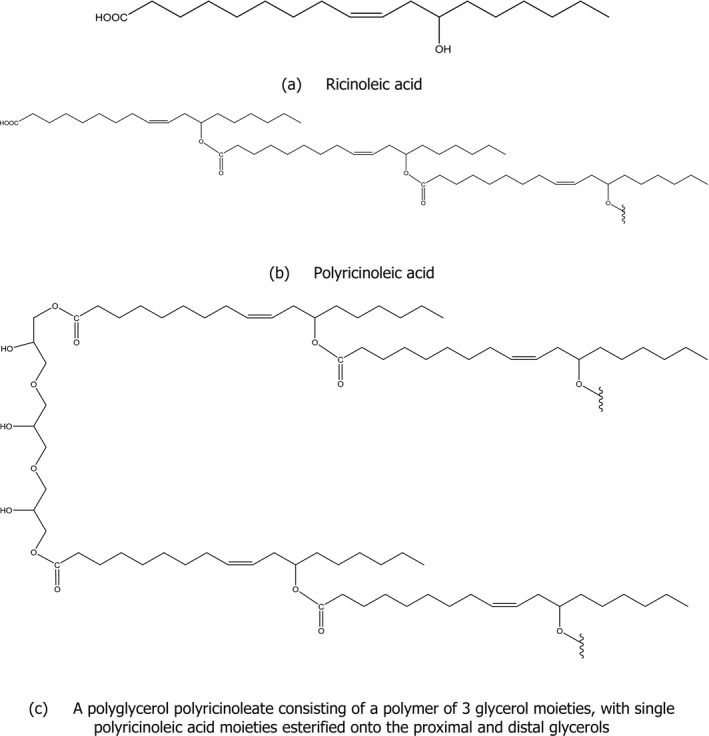

The chemical name of the main component for the CAS Registry number is 68936‐89‐0 is 1,2,3‐propanetriol, homopolymer, (9Z,12R)‐12‐hydroxy‐9‐octadecenoate (Scifinder, online) with a molecular formula of C18H34O3 · x(C3H8O3)n, an EINECS number has not been assigned. The Panel noted that an additional CAS number – 29894‐35‐7 – has been assigned with the molecular formula (C18H34O3 · C3H8O3)n. The general structural formula of PGPR is given in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Structural formula of polyglycerol polyricinoleate, adapted from Bastida‐Rodriguez, (2013). (Copyright © 2013 Josefa Bastida‐Rodríguez, Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 3.0)

PGPR is also known by the synonyms glycerol esters of condensed castor oil fatty acids, polyglycerol esters of polycondensed fatty acids from castor oil and polyglycerol esters of interesterified ricinoleic acid (Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012).

The polyglycerol moieties of PGPR are mainly linear condensation products of glycerol (Behrens and Mieth, 1984). The polyglycerols’ primary hydroxyl groups react mostly with polyricinoleate and in a minor proportion with monoricinoleate and other fatty acids (i.e. oleic, linoleic, stearic acid) to obtain PGPR (Orfanakis et al., 2013)

According to the Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012, PGPR is a clear, highly viscous liquid, which is insoluble in water and ethanol, but soluble in ether, hydrocarbons and halogenated hydrocarbons. In EFEMA (2009) [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 5], the colour of the liquid is described as light brown and it does not crystallise at 0°C.

3.1.2. Specifications

Specifications for PGPR (E 476) have been defined in Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 and by JECFA (2006). The available specifications are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specifications for PGPR (E 476) according to Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 and JECFA (2006)

| Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 | JECFA (2006) | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Polyglycerol polyricinoleate is prepared by the esterification of polyglycerol with condensed castor oil fatty acids |

Prepared by the esterification of polyglycerol with condensed castor oil fatty acids The article of commerce may be specified further as to saponification value, solidification point of the free fatty acids, iodine value, acid value, hydroxyl value, ash content and refractive index |

| Description | Clear, highly viscous liquid | Highly viscous liquids |

| Identification | ||

| Solubility | Insoluble in water and in ethanol; soluble in ether, hydrocarbons and halogenated hydrocarbons | Insoluble in water and in ethanol; soluble in ether, hydrocarbons and halogenated hydrocarbons |

| Test for glycerol | Passes test | Spot 5–20 μL of the aqueous layer obtained in the test for fatty acids under Identification test for functional groups alongside control spots of glycerol on paper such as Whatman No. 3 and develop using descending chromatography for 36 h with isopropanol:water, 90:10. The glycerol spot moves 40 cm and the polyglycerols are revealed in succession below that for glycerol when the paper is sprayed with either permanganate in acetone or ammoniacal silver nitrate |

| Test for polyglycerol | Passes test | Spot 5–20 μL of the aqueous layer obtained in the test for fatty acids under Identification test for functional groups alongside control spots of glycerol on paper such as Whatman No. 3 and develop using descending chromatography for 36 h with isopropanol:water, 90:10. The glycerol spot moves 40 cm and the polyglycerols are revealed in succession below that for glycerol when the paper is sprayed with either permanganate in acetone or ammoniacal silver nitrate |

| Test for ricinoleic acid | Passes test | The fatty acids liberated in test for fatty acids Identification tests for functional groups should have a hydroxyl value corresponding to that for castor oil fatty acids (about 150–170) |

| Refractive index | [n]D 65 between 1.4630 and 1.4665 | |

| Tests for fatty acids | Passes tests | |

| Purity | ||

| Polyglycerols | The polyglycerol moiety shall be composed of not less than 75% of di‐, tri‐ and tetraglycerols and shall contain not more than 10% of polyglycerols equal to or higher than heptaglycerol | The polyglycerol moiety shall be composed of not less than 75% of di‐, tri‐ and tetraglycerols and shall contain not more than 10% of polyglycerols equal to or higher than heptaglycerol |

| Hydroxyl value | Not less than 80 and not more than 100 | |

| Acid value | Not more than 6 | |

| Arsenic | Not more than 3 mg/kg | |

| Lead | Not more than 2 mg/kg |

Not more than 2 mg/kg Determine using an atomic absorption technique appropriate to the specified level. The selection of sample size and method of sample preparation may be based on the principles of the method described in Volume 4, ‘Instrumental Methods’ |

| Mercury | Not more than 1 mg/kg | – |

| Cadmium | Not more than 1 mg/kg | – |

The Panel noted that according to the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476), impurities of the toxic elements arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium are accepted up to a concentration of 3, 2, 1 and 1 mg/kg, respectively. Contamination at such levels could have a significant impact on the exposure to these metals, for which the exposure already are close to the health‐based guidance values or benchmark doses (lower Confidence Limits) established by EFSA (EFSA CONTAM Panel, 2009a,b, 2010, 2012b, c, d, 2014).

According to the available information on the manufacturing process (Section 3.3), PGPR (E 476) is manufactured from glycerol and castor oil. The Panel noted that following extraction of castor oil, ricin is left in the press‐cake/castor bean meal (also called castor meal, castor residue, castor extract and de‐oiled castor cake) (EFSA CONTAM Panel, 2008). The Panel noted limits for active ricin are not included in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

The Panel also noted that a maximum residual level for 3‐monochloropropane‐1,2‐diol (3‐MCPD) (not more than 0.1 mg/kg) has been established in EU specifications for glycerol (E 422) (Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012); however, there are no limits for 3‐MCPD in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

Information on the manufacturing processes of glycerol has been considered by the ANS Panel in the re‐evaluation of glycerol (E 422) (EFSA ANS Panel, 2017). The Panel noted that glycerol (E 422) can be produced by a variety of methods and that many of them lead to the presence or formation of contaminants, which are of toxicological concern. The Panel considered that the manufacturing process for PGPR (E 476) should not allow the presence of residuals of genotoxic or/and carcinogenic concern at a level which would result in a margin of exposure (MOE) below 10,000. The Panel considered that maximum limits for potential impurities in glycerol as raw material in the manufacturing process of PGPR should also be established for the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

The Panel noted that epichlorohydrin and glycidol may be present in PGPR (E 476) from the manufacturing processes of polyglycerols. The Panel considered that the presence of epichlorohydrin and/or glycidol in PGPR (E 476) would need further assessment as their presence could raise a safety concern.

3.1.3. Manufacturing process

Wilson et al. (1998) and Bastida‐Rodriguez (2013) described a process for the manufacture of PGPR, involving the following four steps:

-

i

Preparation of the castor oil fatty acids

The castor oil fatty acids are produced by hydrolysing castor oil with water and steam at a pressure of approximately 2.8 MPa without a catalyst; the resulting fatty acids are freed from glycerol by water washing. Castor oil contains, as main fatty acids: ricinoleic acid (80–90%), oleic acid (3–8%), linoleic acid (3–7%) and stearic acid (0–2%).

-

ii

Condensation of the castor oil fatty acids

The castor oil fatty acids are condensed by heating the castor oil fatty acids at a temperature of 205–210°C under vacuum and a CO2 atmosphere (to prevent oxidation) for approximately 8 h. The reaction is controlled, by monitoring the acid value, until an acid value of 35–40 mg KOH/g (i.e. about 4–5 fatty acid residues per molecule of condensed substance).

-

iii

Preparation of polyglycerols

According to Bastida‐Rodriguez (2013), the polyglycerol portion can be prepared by three routes: (1) by polymerisation of glycerol using a strong base as a catalyst, (2) by polymerisation of glycidol, which leads to linear polyglycerols or (3) by polymerisation of epichlorohydrin, followed by hydrolysis, which also leads to linear polyglycerols. Polyglycerols produced by polymerisation of epichlorohydrin contain reduced proportions of cyclic components.

The Panel noted that epichlorohydrin and glycidol may be present in PGPR (E 476) from the manufacturing processes of polyglycerols. Epichlorohydrin and glycidol are classified as carcinogen 2A according to IARC (1999) and probably carcinogenic to humans (2A) according to IARC (2000). The EFSA CONTAM Panel has characterised glycidol as genotoxic and carcinogenic (EFSA CONTAM Panel, 2016).

-

iv

Partial esterification of the condensed castor oil fatty acids with polyglycerols

The final stage of the production involves heating of an appropriate amount of polyglycerol with the polyricinoleic acid. The reaction takes place immediately following the preparation of the latter and in the same vessel, while the charge is still hot. The esterification conditions are the same as those for fatty acid condensation. The process is continued until a sample withdrawn from the reaction mixture is found to have a suitable acid value (i.e. ≤ 6 mg KOH/g) and refractive index, as required by the specifications.

Tenore (2012) described a new process for the manufacturing of PGPR using as starting materials polyglycerols and castor oil fatty acids obtained as described by Wilson et al. (1998). In this new process, non‐polymerised ricinoleic acid is combined with polyglycerols (preferably with a molecular weight in the range of 160–400 g/mol) at a ratio of about 11:1 (w/w). Non‐polymerised ricinoleic acid is condensed to polyricinoleate which is then, in a one‐step process, reacted with polyglycerol. Water is continuously removed under reduced pressure (about 0.068 MPa). The condensation, the contemporaneous co‐polymerisation and the interesterification is conducted at a temperature of 200°C. The condensation and co‐polymerisation reactions are maintained until the PGPR in the reaction mixture reaches the characteristics complying with EU specifications. It is indicated by the author that in this new process a catalyst is not necessary, but that the reaction rate can be increased using either a basic catalyst (sodium or potassium hydroxide) or an acidic catalyst (phosphoric or phosphorous acid). It is also indicated that an enzymatic catalyst (lipase approved for food applications; not further specified) can be used. When the enzymatic catalyst is used, the reaction temperature is reduced to 75°C.

Gómez et al. (2011) described the enzymatic biosynthesis of polyglycerol polyricinoleate (E 476) starting from polyglycerol and polyricinoleic acid using Rhizopus arrhizus lipase as a catalyst. The reaction takes place in the presence of a very limited amount of aqueous phase. It is stated that no organic solvent was necessary to solubilise the substrates, allowing a reaction medium solely composed of the required substrates. In the process, lipase is immobilised by physical adsorption onto an anion exchange matrix. PGPR produced by this process had an acid value of 16 mg KOH/g which was far above the required EU specification for this parameter (i.e. acid value < 6 mg KOH/g), However, when synthesised under controlled atmosphere in a vacuum reactor with dry nitrogen intake, the PGPR reaction product obtained in this way had an acid value of 4.9 mg KOH/g, complying with the EU specifications. It is stated that the method is a starting point for using the enzymatic procedure in the industrial biosynthesis of PGPR.

In subsequent publications, the same authors (Ortega et al., 2013; Ortega‐Requena et al., 2014) described improved methods using lipases from R. arrhizus, Rhizopus oryzae and Candida antartica, resulting in the production of a PGPR with an acid value of 4.91, 5.31 and 1.30 mg KOH/g, respectively.

Information on the manufacture of glycerol is included in the EFSA opinion on the re‐evaluation of glycerol (E 422) as a food additive (EFSA ANS Panel, 2017).

3.1.4. Methods of analysis in food

Davies and Harkes (1977 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 3]) described a method for estimating the levels of PGPR in chocolate. In this method, the lipidic material in the chocolate was extracted with chloroform (Soxhlet method) and the chloroform then evaporated using a rotary evaporator. The residue was hydrolysed with methanolic potassium hydroxide (KOH) in the presence of methyl 2‐hydroxydocosanoate as an internal standard and again extracted with chloroform, dried with magnesium sulfate, filtered and finally evaporated to dryness. This extract was subsequently methylated with diazomethane and the resulting methylated hydroxy fatty acid esters isolated by preparative thin‐layer chromatography (TLC) followed by analysis by gas‐liquid chromatography (GLC) either directly or after being silylated. For quantitative analysis, standard solutions of methyl ricinoleate and methyl 2‐hydroxydocosanoate in toluene were used. The PRGR content in chocolate was estimated on the basis of a known ratio of the ricinolate in the food additive.

The fatty acid components of PGPR were analysed in a chocolate sample after extraction with toluene. The extract was saponified with ethanolic KOH, hydrolysed, silylated and analysed by gas chromatography (GC) (Dick and Miserez, 1976).

The Panel noted that PGPR as such cannot be directly measured in foods and that the methods employed to date involve indirect determination of hydrolysis products, which may also be derived from other food additives. All analytical methods available lead to the detection of ricinoleic acid or its esters in food and cannot be used for quantification of actual PGPR, as the ricinolate ratio in the food additive is not specified in the EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

3.1.5. Stability of the substance and reaction and fate in food

A stability test of PGPR was performed at 15°C over a period of 32 months. Physical and chemical parameters (acid value, iodine value, saponification value, refractive index, hydroxyl value, peroxide value) were measured. No significant change of these parameters could be observed (Quest International, 1997 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 12]).

According to Emulsar (2016 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 7]), the first step in PGPR degradation in food is the hydrolysis of ricinoleic acid moieties from polyglycerol.

Three samples of milk chocolate to which a known amount of PGPR was added, were stored for a period of 12 or 16 months. The content of the ricinolate moiety of PGPR was measured by GC, using the method of Davies and Harkes (1977 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 3]). The differences in ricinolate content after storage and that measured in the PGPR initially added to each of the chocolates were in all cases within the experimental error indicating a stability of ricinolate. No conclusions were drawn by the authors about the stability of the intact food additive or the degree of hydrolysis needed to yield free ricinoleic acid (Quest International, 1997 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 12]).

In storage trials of water in oil emulsions at 30°C, it has been demonstrated that the firmness of the emulsions containing PGPR remains high, indicating that the structure of PGPR does not change significantly for the tested period of 3 months (Emulsar, 2016, [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 7]).

3.2. Authorised uses and use levels

Maximum levels of PGPR (E 476) have been defined in Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives, as amended. In this document, these levels are named maximum permitted levels (MPLs).

Currently, PGPR (E 476) is an authorised food additive in the EU with MPLs ranging from 4,000 to 5,000 mg/kg in five food categories.

Table 2 summarises the food that are permitted to contain PGPR (E 476) and the corresponding MPLs as set by Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008.

Table 2.

MPLs of PGPR (E 476) in foods according to the Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008

| Food category number | Food category name | Restrictions/exception | MPL (mg/L or mg/kg as appropriate) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 02.2.2 | Other fat and oil emulsions including spreads as defined by Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 and liquid emulsions | Only spreadable fats as defined in Article 115 and Annex XV to Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007, having a fat content of 41% or less and similar spreadable products with a fat content of less than 10% fat | 4,000 |

| 05.1 | Cocoa and chocolate products as covered by Directive 2000/36/EC | 5,000 | |

| 05.2 | Other confectionery including breath freshening microsweets | Only cocoa‐based confectionery | 5,000 |

| 05.4 | Decorations, coatings and fillings, except fruit‐based fillings covered by category 4.2.4 | Only cocoa‐based confectionery | 5,000 |

| 12.6 | Sauces | Only dressings | 4,000 |

MPL: maximum permitted level.

According to Annex III, Part 2 of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008, PGPR (E 476) is also authorised as an emulsifier in preparations of food colours E 100 curcumin and E 120 cochineal, carminic acid, carmines and E 163 anthocyanins at the maximum levels of 50,000 mg/kg in the food colour preparations and at 500 mg/kg in the final food only in:

Surimi and Japanese‐type fish products (Kamaboko) (for the food additive E 120 cochineal, carminic acid, carmines);

meat products, fish pastes and fruit preparations used in flavoured milk products and desserts (for the food additives E 163 anthocyanins, E 100 curcumin and E 120 cochineal, carminic acid, carmines).

3.3. Exposure data

3.3.1. Reported use levels or data on analytical levels of PGPR (E 476)

Most food additives in the EU are authorised at a specific MPL. However, a food additive may be used at a lower level than the MPL. Therefore, information on actual use levels is required for performing a more realistic exposure assessment, especially for those food additives for which no MPL is set and which are authorised according to quantum satis (QS).

In the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives and of Commission Regulation (EU) No 257/2010 regarding the re‐evaluation of approved food additives, EFSA issued public calls13 , 14 for occurrence data (usage level and/or analytical data) on PGPR (E 476). In response to this public call, updated information on the actual use levels of PGPR (E 476) in foods was made available to EFSA by industry. No analytical data on the occurrence of PGPR (E 476) in foods were made available by the Member States.

3.3.1.1. Summarised data on reported use levels in foods provided by industry

Industry provided EFSA with data on use levels (n = 149) of PGPR (E 476) in foods for all the five food categories in which PGPR (E 476) is authorised according to Annex II to Regulation No 1333/2008 (Table 2).

Updated information on the actual use levels of PGPR (E 476) in foods was made available to EFSA by FoodDrinkEurope (FDE), European Food Emulsifiers Manufacturers Association (EFEMA), European Dairy Association (EDA) and Mars.

Data were also provided for food categories in which PGPR (E 476) is not authorised as such but in which chocolate is present as coating. Such data were received for ice‐cream (FCS 03) and coated nuts (FCS 15.2).

The Panel noted that EFEMA is not food industry using emulsifiers in its food products but an association of food additive producers. Usage levels reported by food additive producers should not, by default, be considered at the same level as those provided by food industry. Food additive producers might recommend usage levels to the food industry but the final levels used might, ultimately, be different, unless food additive producers confirm that these levels are used by food industry. According to EFEMA, all the submitted data are ‘suggested amounts and recommendations by [the] association, based on [their] technological understanding as food emulsifier manufacturers to food industry and on practical experience in model application systems, but not based on actual usage data in final consumer products’. Therefore, these levels were not used in the exposure assessment of PGPR (E 476).

Appendix A provides data on the use levels of PGPR (E 476) in foods as reported by industry.

3.3.2. Summarised data extracted from the Mintel's Global New Products Database

The Mintel GNPD is an online database, which monitors product introductions in consumer packaged goods markets worldwide. It contains information of over 2 million food and beverage products of which more than 900,000 are or have been available on the European food market. The Mintel GNPD started covering EU's food markets in 1996, currently having 20 out of its 28 member countries and Norway presented in the Mintel GNPD.15

For the purpose of this Scientific Opinion, the Mintel GNPD was used for checking the labelling of products containing PGPR (E 476) within the EU's food products as the Mintel GNPD shows the compulsory ingredient information presented in the labelling of products.

According to the Mintel GNPD, PGPR (E 476) is labelled on more than 8,200 products between 2011 and 201616 of ice‐cream (‘Dairy‐based frozen products’) and chocolates mainly.

Appendix B presents the percentage of the food products labelled with PGPR (E 476) between 2011 and 2016, out of the total number of food products per food subcategories according to the Mintel GNPD food classification.

3.3.3. Food consumption data used for exposure assessment

3.3.3.1. EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database

Since 2010, the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database (Comprehensive Database) has been populated with national data on food consumption at a detailed level. Competent authorities in the European countries provide EFSA with data on the level of food consumption by the individual consumer from the most recent national dietary survey in their country (cf. Guidance of EFSA on the ‘Use of the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database in Exposure Assessment’ (EFSA, 2011a)). New consumption surveys recently17 added in the Comprehensive database were also taken into account in this assessment.18

The food consumption data gathered by EFSA were collected by different methodologies and thus direct country‐to‐country comparisons should be interpreted with caution. Depending on the food category and the level of detail used for exposure calculations, uncertainties could be introduced owing to possible subjects’ underreporting and/or misreporting of the consumption amounts. Nevertheless, the EFSA Comprehensive Database represents the best available source of food consumption data across Europe at present.

Food consumption data from the following population groups: infants, toddlers, children, adolescents, adults and the elderly were used for the exposure assessment. For the present assessment, food consumption data were available from 33 different dietary surveys carried out in 19 European countries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Population groups considered for the exposure estimates of PGPR (E 476)

| Population | Age range | Countries with food consumption surveys covering more than 1 day |

|---|---|---|

| Infants | From more than 12 weeks up to and including 11 months of age | Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, UK |

| Toddlers | From 12 months up to and including 35 months of age | Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, UK |

| Childrena | From 36 months up to and including 9 years of age | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, UK |

| Adolescents | From 10 years up to and including 17 years of age | Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Spain, Sweden, UK |

| Adults | From 18 years up to and including 64 years of age | Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Romania, Spain, Sweden, UK |

| The elderlya | From 65 years of age and older | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Romania, Sweden, UK |

The terms ‘children’ and ‘the elderly’ correspond, respectively, to ‘other children’ and the merge of ‘elderly’ and ‘very elderly’ in the Guidance of EFSA on the ‘Use of the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database in Exposure Assessment’ (EFSA, 2011a).

Consumption records were codified according to the FoodEx classification system (EFSA, 2011b). Nomenclature from the FoodEx classification system has been linked to the food categorisation system (FCS) as presented in Annex II of Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008, part D, to perform exposure estimates. In practice, FoodEx food codes were matched to the FCS food categories.

3.3.3.2. Food categories considered for the exposure assessment of PGPR (E 476)

The food categories in which the use of PGPR (E 476) is authorised were selected from the nomenclature of the EFSA Comprehensive Database (FoodEx classification system), at the most detailed level possible (up to FoodEx Level 4) (EFSA, 2011b).

Some food categories or their restrictions/exceptions are not referenced in the EFSA Comprehensive Database and could therefore not be taken into account in the present estimate. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the exposure. The food category which was not taken into account is described below:

05.4 Decorations, coatings and fillings, except fruit‐based fillings covered by category 4.2.4.

For the four remaining food categories, the refinements considering the restrictions/exceptions as set in Annex II to Regulation No 1333/2008 were applied.

However, as mentioned above, reported use levels of PGPR (E 476) were also provided for edible ices and processed nuts for which the use is not authorised as such according to Annex II. As the food additive was labelled on many ice‐cream products (the main food labelled to contain the food additive according to the Mintel GNPD database) (Appendix B), the Panel decided that exposure via this food category (FC 03) should be taken into account. Therefore, exposure via chocolate from ice‐cream products was considered in all exposure scenarios with the assumption that chocolate as an ingredient represents 15% of all ice‐cream products. This is very likely an overestimation of the average percentage and is included in the uncertainty analysis (Section 3.4.3). Use levels provided for processed nuts were attributed to coated nuts (belonging to FC 15.2 Processed nuts) selected from the FoodEx nomenclature. The MPL attributed to the coated nuts was the one of the cocoa products (FC 05.1) (Appendix C).

As mentioned above, PGPR (E 476) is also authorised according to Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 with a maximum level of 500 mg/kg in meat products, fish pastes and fruit preparations used in flavoured milk products and desserts. The food categories meat products (FC 08.3) and fish pastes (FC 09.2) were taken into account in the regulatory maximum level scenario using the defined level of 500 mg/kg according to Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008.

Overall, in the regulatory exposure scenario, eight food categories were included (Appendix C), and in the refined exposure scenario five food categories (no reported use levels available for sauces (FC 12.6) authorised under Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008, neither for meat products (FC 08.3) and fish pastes (FC 09.2) authorised under Annex III of the same regulation) were included.

3.4. Exposure estimate

3.4.1. Exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive

The Panel estimated chronic exposure to PGPR (E 476) for the following population groups: infants; toddlers, children, adolescents, adults and the elderly. Dietary exposure to PGPR (E 476) was calculated by multiplying PGPR (E 476) concentrations for each food category (Appendix C) with their respective consumption amount per kilogram of body weight for each individual in the Comprehensive Database. The exposure per food category was subsequently added to derive an individual total exposure per day. These exposure estimates were averaged over the number of survey days, resulting in an individual average exposure per day for the survey period. Dietary surveys with only 1 day per subject were excluded as they are considered as not adequate to assess repeated exposure.

This was carried out for all individuals per survey and per population group, resulting in distributions of individual exposure per survey and population group (Table 3). On the basis of these distributions, the mean and 95th percentile of exposure were calculated per survey and per population group. The 95th percentile of exposure was only calculated for those population groups where the sample size was sufficiently large to allow this calculation (EFSA, 2011a). Therefore, in the present assessment, the 95th percentile of exposure for infants from Italy and for toddlers from Belgium, Italy and Spain were not included.

Two exposure scenarios were defined and carried out by the ANS Panel regarding the concentration data of PGPR (E 476) used: (1) MPLs as set down in the EU legislation (defined as the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario); and (2) the reported use levels (defined as the refined exposure assessment scenario). These two scenarios are discussed in detail below.

A possible additional exposure from the use of PGPR (E 476) as a food additive in food additive preparation in accordance with Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 (Part 2) was not considered in the refined exposure assessment scenarios.

3.4.1.1. Regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario

The regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario is based on the MPLs as set in Annex II and Annex III, Part 2, to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 and listed in Table 2. Appendix C summarises the concentration levels of PGPR (E 476) used in this exposure scenario.

The Panel considers the exposure estimates derived following this scenario as the most conservative as it is assumed that the population group will be exposed to PGPR (E 476) present in food at the MPL over a longer period of time.

3.4.1.2. Refined exposure assessment scenario

The refined exposure assessment scenario is based on use levels reported by industry. This exposure scenario can consider only food categories for which these data were available to the Panel.

Appendix C summarises the concentration levels of PGPR (E 476) used in the refined exposure assessment scenario. Based on the available data set, the Panel calculated two refined exposure estimates based on different model populations:

-

The brand‐loyal consumer scenario: It was assumed that a consumer is exposed long‐term to PGPR (E 476) present at the maximum reported use level for one food category. This exposure estimate is calculated as follows:

-

–

Combining food consumption with the maximum of the reported use levels for the main contributing food category at the individual level.

-

–

Using the mean of the typical reported use levels for the remaining food categories authorised according Annex II.

-

–

The non‐brand‐loyal consumer scenario: It was assumed that a consumer is exposed long‐term to PGPR (E 476) present at the mean reported use levels in food. This exposure estimate is calculated using the mean of the typical reported use levels for all food categories authorised according Annex II.

3.4.1.3. Dietary exposure to PGPR (E 476)

Table 4 summarises the estimated exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive in six population groups (Table 3) according to the different exposure scenarios (Section 3.4.1). Detailed results per population group and survey are presented in Appendix D.

Table 4.

Summary of dietary exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive in the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario and in the refined exposure scenarios, in six population groups (minimum–maximum across the dietary surveys in mg/kg bw per day)

| Infants (12 weeks–11 months) | Toddlers (12–35 months) | Children (3–9 years) | Adolescents (10–17 years) | Adults (18–64 years) | The elderly (≥ 65 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario | ||||||

| Mean | 0.1–1.0 | 0.8–6.2 | 2.2–5.9 | 1.2–3.4 | 0.5–2.2 | 0.3–2.1 |

| 95th percentile | 0.6–4.2 | 2.9–12.4 | 5.8–13.3 | 3.7–8.7 | 1.6–5.9 | 1.1–6.0 |

| Refined exposure assessment scenario | ||||||

| Brand‐loyal scenario | ||||||

| Mean | 0.01–0.6 | 0.3–3.6 | 0.9–4.0 | 0.7–2.3 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.1–1.5 |

| 95th percentile | < 0.01–2.6 | 1.3–9.2 | 3.0–12.0 | 2.9–7.1 | 1.1–4.1 | 0.6–5.2 |

| Non‐brand‐loyal scenario | ||||||

| Mean | < 0.01–0.2 | 0.1–2.8 | 0.3–2.4 | 0.1–0.9 | 0.04–0.9 | 0.02–1.3 |

| 95th percentile | < 0.01–0.9 | 0.7–6.8 | 1.2–6.0 | 0.6–2.9 | 0.2–3.4 | 0.1–4.7 |

In the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario, mean exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive ranged from 0.1 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 6.2 mg/kg bw per day in toddlers. The 95th percentile of exposure to PGPR (E 476) ranged from 0.6 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 13.3 mg/kg bw per day in children.

In the refined estimated exposure scenario, in the brand‐loyal scenario, mean exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive ranged from 0.01 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 4.0 mg/kg bw per day in children. The high exposure to PGPR (E 476) ranged from < 0.01 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 12.0 mg/kg bw per day in children. In the non‐brand‐loyal scenario, mean exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive ranged from < 0.01 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 2.8 mg/kg bw per day in toddlers. The 95th percentile of exposure to PGPR (E 476) ranged from < 0.01 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 6.8 mg/kg bw per day in toddlers.

3.4.1.4. Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario (Tables 5, 6 and 7)

Table 6.

Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using the brand‐loyal refined exposure scenario (> 5% to the total mean exposure) and number of surveys in which each food category is contributing

| Food category number | Food category name | Infants | Toddlers | Children | Adolescents | Adults | The elderly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of % contribution to the total exposure (number of surveys)a | |||||||

| 02.2 | Fat and oil emulsions mainly of type water‐in‐oil | 15.6–55.5 (3) | 7.5–72.4 (5) | 6.7–61.6 (9) | 7.9–54.6 (8) | 6.5–67.8 (8) | 12.1–79.9 (9) |

| 03 | Edible icesb | 7.3–31.8 (4) | 6.0–31.7 (4) | 5.8–25.4 (7) | 5.3–26.2 (3) | 5.1–31.9 (7) | 5.0–32.8 (7) |

| 05.1 | Cocoa and Chocolate products as covered by Directive 2000/36/EC | 16.9–100 (6) | 15.7–100 (10) | 28.9–98.3 (18) | 42.8–98.8 (17) | 31.1–97.9 (17) | 19.1–95.0 (14) |

| 05.2 | Other confectionery including breath refreshening microsweetsb | 10.2–22.8 (2) | 9.8–34.7 (5) | 5.3–37.5 (6) | 6.1–51.1 (5) | 8.0–52.2 (7) | 5.7–30.2 (5) |

| 15.2 | Processed nuts | – | 6.1–12.3 (2) | – | – | – | – |

–: Food categories not contributing or contributing less than 5% to the total mean exposure.

The total number of surveys may be greater than the total number of countries as listed in Table 3, as some countries submitted more than one survey for a specific population.

Considering only the chocolate coating or filling representing 15%.

Table 7.

Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using the non‐brand‐loyal refined exposure scenario (> 5% to the total mean exposure) and number of surveys in which each food category is contributing

| Food category number | Food category name | Infants | Toddlers | Children | Adolescents | Adults | The elderly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of % contribution to the total exposure (number of surveys)a | |||||||

| 02.2 | Fat and oil emulsions mainly of type water‐in‐oil | 43.6–89.1 (3) | 24.7–86.2 (5) | 4.9–81.1 (12) | 7.8–80.5 (10) | 21.0–87.3 (8) | 28.8–92.6 (9) |

| 03 | Edible icesb | 7.4 (1) | – | 5.1 (1) | 6.1 (1) | 7.8 (1) | 7.5 (1) |

| 05.1 | Cocoa and Chocolate products as covered by Directive 2000/36/EC | 8.2–100 (6) | 5.7–100 (10) | 12.0–98.4 (18) | 19.0–98.8 (17) | 12.5–99.0 (17) | 7.3–97.8 (14) |

| 05.2 | Other confectionery including breath refreshening microsweets | 22.8–33.2 (2) | 7.9–49.8 (5) | 5.0–56.2 (11) | 8.6–69.0 (8) | 6.7–66.6 (9) | 7.7–47.2 (5) |

| 15.2 | Processed nuts | – | 10.8–17.4 (2) | – | – | – | – |

–: Food categories not contributing or contributing less than 5% to the total mean exposure.

The total number of surveys may be greater than the total number of countries as listed in Table 3, as some countries submitted more than one survey for a specific population.

Considering only the chocolate coating or filling representing 15%.

Table 5.

Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using maximum permitted levels (> 5% to the total mean exposure) and number of surveys in which each food category is contributing

| Food category number | Food category name | Infants | Toddlers | Children | Adolescents | Adults | The elderly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of % contribution to the total exposure (number of surveys)a | |||||||

| 02.2 | Fat and oil emulsions mainly of type water‐in‐oil | 22.8 (1) | 5.4–43.5 (5) | 5.5–39.6 (7) | 5.9–34.1 (5) | 5.4–44.4 (6) | 6.5–59.0 (7) |

| 03 | Edible icesb | 5.4–12.7 (3) | 5.2–19.2 (6) | 5.0–23.7 (11) | 5.0–24.5 (11) | 6.9–22.1 (4) | 5.2–20.3 (3) |

| 05.1 | Cocoa and Chocolate products as covered by Directive 2000/36/EC | 8.3–90.6 (5) | 9.3–74.6 (10) | 16.8–68.1 (18) | 22.0–69.9 (17) | 15.6–58.3 (17) | 10.9–50.1 (14) |

| 05.2 | Other confectionery including breath refreshening microsweetsb | 7.1 (1) | 6.5–18.7 (5) | 7.9–20.3 (4) | 5.0–27.2 (4) | 5.7–20.0 (5) | 5.1–12.0 (4) |

| 08.3 | Meat productsc | 9.4–96.2 (6) | 18.3–52.6 (10) | 14.4–54.7 (18) | 12.5–42.5 (17) | 17.2–64.8 (17) | 14.2–74.9 (14) |

| 09.2 | Processed fish and fishery products including molluscs and crustaceans – only fish pastec | 5.4–6.0 (2) | 5.6–6.1 (3) | 6.9 (1) | – | – | – |

| 12.6 | Sauces | 6.9 (1) | 6.2–7.1 (2) | 5.6–16.0 (6) | 7.6–18.8 (7) | 11.3–23.8 (10) | 5.8–30.2 (11) |

| 15.2 | Processed nuts | – | 6.3 (1) | – | – | – | – |

–: Food categories not contributing or contributing less than 5% to the total mean exposure.

The total number of surveys may be greater than the total number of countries as listed in Table 3, as some countries submitted more than one survey for a specific population.

Considering only the chocolate coating or filling representing 15%.

FC authorised according to Annex III to Regulation No 1333/2008.

3.4.1.5. Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using the refined exposure assessment scenario

3.4.2. Exposure to PGPR (E 476) considering the proposed extension of use for this food additive in emulsified sauces (food category 12.6)

A request was made to extend the use of PGPR (E 476) in FCS 12.6, emulsified sauces, including mayonnaise at a maximum level of 4,000 mg/kg. The exposure to PGPR (E 476) according to the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario including this proposed use level is presented in Table 8. Detailed results per population group and survey are presented in Appendix E.

Table 8.

Summary of dietary exposure to PGPR (E 476) from its use as a food additive in the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario including the proposed use level of 4,000 mg/kg for food category 12.6 (emulsified sauces) in six population groups (minimum–maximum across the dietary surveys in mg/kg bw per day)

| Infants (12 weeks–11 months) | Toddlers (12–35 months) | Children (3–9 years) | Adolescents (10–17 years) | Adults (18–64 years) | The elderly (≥ 65 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario taking into account the new proposed use | ||||||

| Mean | 0.1–2.2 | 0.9–9.4 | 2.3–8.4 | 1.4–5.2 | 0.5–3.5 | 0.3–3.0 |

| 95th percentile | 0.6–10.5 | 2.9–16.9 | 6.1–20.8 | 4.0–12.3 | 1.8–9.8 | 1.3–8.2 |

In the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario including the proposed extension of use of PGPR (E 476) to emulsified sauces, mean exposure to PGPR (E 476) ranged from 0.1 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 9.4 mg/kg bw per day in toddlers. The 95th percentile of exposure to PGPR (E 476) ranged from 0.6 mg/kg bw per day in infants to 20.8 mg/kg bw per day in children.

Compared to the exposure estimates taking into account only the current authorised uses, the intakes increased up to a factor 2 for certain population groups and countries.

3.4.2.1. Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) according to the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario including the proposed use level of 4,000 mg/kg for food category 12.6 (emulsified sauces) (Table 9)

Table 9.

Main food categories contributing to exposure to PGPR (E 476) using maximum permitted levels considering the proposed extension of use for this food additive in emulsified sauces (> 5% to the total mean exposure) and number of surveys in which each food category is contributing

| Food category number | Food category name | Infants | Toddlers | Children | Adolescents | Adults | The elderly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of % contribution to the total exposure (number of surveys)a | |||||||

| 02.2 | Fat and oil emulsions mainly of type water‐in‐oil | 11.8 (1) | 5.3–31.9 (4) | 5.6–29.4 (5) | 5.0–15.8 (6) | 6.2–23.6 (4) | 5.1–40.4 (6) |

| 03 | Edible icesb | 10.8–11.5 (2) | 8.0–17.9 (4) | 5.1–22.7 (10) | 5.7–22.1 (5) | 5.8–19.7 (4) | 8.2–19.0 (2) |

| 05.1 | Cocoa and Chocolate products as covered by Directive 2000/36/EC | 7.6–90.6 (5) | 6.1–63.1 (10) | 9.8–60.3 (18) | 13.6–60.2 (17) | 9.3–48.9 (17) | 7.4–43.7 (14) |

| 05.2 | Other confectionery including breath refreshening microsweetsb | 6.4 (1) | 5.5–11.7 (4) | 5.9–14.8 (4) | 8.8–16.7 (3) | 6.2–12.0 (4) | 5.2–7.0 (2) |

| 08.3 | Meat productsc | 9.4–95.4 (6) | 11.7–48.9 (10) | 9.5–53.1 (18) | 8.0–35.7 (17) | 9.1–64.2 (17) | 9.7–74.9 (14) |

| 09.2 | Processed fish and fishery products including molluscs and crustaceans – only fish pastec | – | 5.4 (1) | 6.5 (1) | – | – | – |

| 12.6 | Sauces | 8.9–54.7 (4) | 7.7–46.0 (8) | 5.5–42.6 (16) | 9.8–59.7 (16) | 10.8–52.9 (16) | 6.9–48.4 (12) |

–: Food categories not contributing or contributing less than 5% to the total mean exposure.

The total number of surveys may be greater than the total number of countries as listed in Table 3, as some countries submitted more than one survey for a specific population.

Considering only the chocolate coating or filling representing 15%.

FC authorised according to Annex III to Regulation No 1333/2008.

With the current authorised uses, sauces (FC 12.6) contributed up to 30% for one survey in the elderly, and in some surveys, it contributed less than 5% to the total mean exposure estimates (e.g. for infants, only in one survey the contribution is above 5%). Taking into account the proposed extension of use to emulsified sauces, the contribution of FC 12.6 to the mean exposure to PGPR (E 476) increased in most of the surveys for all population groups to almost 60% (in one adults survey).

3.4.3. Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainties in the exposure assessment of PGPR (E 476) have been discussed above. In accordance with the guidance provided in the EFSA opinion related to uncertainties in dietary exposure assessment (EFSA, 2007), the following sources of uncertainties have been considered and summarised in Table 10.

Table 10.

Qualitative evaluation of influence of uncertainties on the dietary exposure estimate

| Sources of uncertainties | Directiona |

|---|---|

| Uncertainties common for all assessments | |

| Consumption data: different methodologies/representativeness/underreporting/misreporting/no portion size standard | +/− |

| Use of data from food consumption survey of a few days to estimate long‐term (chronic) exposure for high percentiles (95th percentile) | + |

| Correspondence of reported use levels to the food items in the EFSA Comprehensive Food Consumption Database: uncertainties to which types of food the levels refer to | +/− |

| Uncertainty in possible national differences in use levels of food categories | +/− |

| Specific uncertainties for this assessment | |

| Food categories selected for the exposure assessment: exclusion of food categories due to missing FoodEx linkage (n = 1/5 food categories from Annex II Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008) | − |

|

Concentration data:

|

+ |

|

Regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario:

|

+/− + |

|

Refined exposure assessment scenarios:

|

− +/− − |

+, uncertainty with potential to cause overestimation of exposure; −, uncertainty with potential to cause underestimation of exposure.

The Panel noted that there might be a slight underestimation of the exposure estimate because not all authorised uses of PGPR (E 476) according to Annex III were considered in the regulatory maximum level exposure assessment scenario and none of these uses were taken into account in the refined exposure assessment scenario.

Overall, the Panel considered that the uncertainties identified would, in general, result in an overestimation of the exposure to PGPR (E 476) as a food additive in European countries considered in the EFSA European Comprehensive Food Consumption Database for both the regulatory maximum level exposure scenario and the refined exposure scenario.

For the scenario including the extended uses of PGPR (E 476) to emulsified sauces, the Panel also considered that the uncertainties identified would result in an overestimation of the exposure to PGPR (E 476) as this scenario assumes that all emulsified sauces would contain the food additive at the proposed maximum use level of 4,000 mg/kg.

3.4.4. Exposure via other sources

Further uses of PGPR, other than as a food additive, are in drugs, cosmetics and personal care products, textile finishing, oil and water emulsions, and release agents (Austen Business Solutions Ltd, 2011 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 2]) (EFEMA, 2009 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 5]). The exposure via these uses is unknown, and was therefore not taken into account in this opinion.

3.5. Biological and toxicological data

This section describes the biological and toxicological data available for PGPR. However, after oral uptake, the Panel considered that PGPR is subjected to hydrolysis by lipases in the gastroinstestinal tract to liberate polyricinoleic acid, ricinoleic acid and other fatty acids present as minor component moiety fatty acids of castor oil, polyglycerols and glycerol. Relevant biological and toxicological data concerning ricinoleic acid, castor oil, polyricinoleic acid and polyglycerols have also been described.

The Panel did not consider biological and toxicological data for glycerol in this opinion since its use as a food additive was recently re‐evaluated by the Panel (EFSA ANS Panel, 2017). The Panel noted however, that glycerol is liberated from normal lipid dietary constituents (e.g. triglycerides) and is re‐esterified at, or soon after absorption (EFSA NDA Panel, 2010).

The Panel noted that the test material used in the Grieco (1974) studies was stated to be an emulsifier widely used in Europe in the manufacturing of various chocolate products. However, it is unknown if this material meets the current EU specifications for PGPR (E 476).

3.5.1. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

3.5.1.1. PGPR

The metabolic fate of 14C[polyglycerol]PGPR was investigated in six rats by gavage of 1.0 mL per rat as a 50% aqueous emulsion. Expired CO2 was monitored for 36 h. Urine and faeces were collected at 24 h intervals for 4 days. Animals were provided with food and water ad libitum. A total of 70% of the administered dose was recovered after 4 days. Chromatographic analysis of the urine revealed that the radioactivity was primarily lower glycerol polymers, i.e. diglycerol and triglycerol. Analysis of the faeces by TLC revealed that approximately 85% of the 14C recovered was as free polyglycerols. The author considered that the PGPR was broken down in the intestine. The data indicated, however, that approximately 10% of the 14C found in the faeces was either undigested or partially digested PGPR. The author suggested that the administered emulsion had separated in the stomach and formed globules of PGPR which could not be completely digested (Grieco, 1974 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 9]).

In another experiment, 14C[polyglycerol]PGPR was administered in an aqueous dietary slurry. Analysis of expired CO2, urine and faeces revealed radioactive recoveries of 8%, 31% and 54%, respectively (time course not specified). According to the author, chromatographic analysis showed that PGPR was completely broken down in this study to liberate polyglycerols. The author considered that PGPR was digested in the rat liberating polyglycerols, some of which are absorbed and excreted unchanged in the urine (lower polymers) and others, which remained to be excreted in the faeces (higher polymers) (Grieco, 1974 [Documentation provided to EFSA n. 9]).