Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most common type of cancer afflicting women and frequently presents at a late stage with a poor prognosis. While paired box 2 (PAX2) expression is frequently lost in high-grade serous ovarian cancer, it is expressed in a subset of ovarian tumors and may play a role in tumorigenesis. This study investigated the expression of PAX2 in ovarian cancer. The expression of PAX2 in a murine allograft model of ovarian cancer, the RM model, led to a more rapidly growing cell line both in vitro and in vivo. This finding was in accordance with the shorter progression-free survival observed in patients with a higher PAX2 expression, as determined in this study cohort by immunohistochemistry. iTRAQ-based proteomic profiling revealed that proteins involved in fatty acid metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation were found to be upregulated in RM tumors expressing PAX2. The expression of two key fatty acid metabolic genes was also found to be upregulated in PAX2-expressing human ovarian cancer samples. The analysis of existing datasets also indicated that a high expression of key enzymes in fatty acid metabolism was associated with a shorter progression-free survival time in patients with serous ovarian cancer. Thus, on the whole, the findings of this study indicate that PAX2 may promote ovarian cancer progression, involving fatty acid metabolic reprograming.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, fatty acid, paired box 2, proteomics, metabolic reprogramming

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women, as well as the most lethal gynecological malignancy (1). The transcription factor, paired box 2 (PAX2) is expressed in a subset of ovarian carcinomas and ovarian cancer cell lines (2,3). The role of PAX2 in ovarian cancer has been described as both that of an oncogene and a tumor suppressor, depending on the context (4,5). PAX2 is normally expressed in Müllerian-derived tissues such as the fallopian tube epithelium (FTE), whereas it is not expressed in the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE). The ectopic expression of Pax2 has been shown to lead to the transformation of rat fibroblasts (6); thus, PAX2 may also contribute to carcinogenesis.

PAX2 belongs to the paired homeobox domain family and is frequently expressed in breast and ovarian cancers and is required for cancer cell survival (7). Although PAX2 expression in ovarian cancer has been reported (2,7), few studies have focused on its role in ovarian carcinogenesis (4,5,8). Furthermore, the effects of PAX2 expression on patient prognosis have not yet been systematically analyzed, at least to the best of our knowledge. Previous studies have demonstrated a role for PAX2 in promoting cell proliferation and chemoresistance in cancer (7,9). PAX2 has been shown to enhance tumor progression or chemoresistance in xenograft models of endometrial, colon and renal cancers (10-12). In a previous study, PAX2 overexpression in a murine ovarian tumor model led to cisplatin resistance and reduced survival, at least in part by the inhibition of p53 and the induction of p-extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), resulting in decreased apoptosis in tumors arising from these cells (5). Resistance to chemotherapy is a common cause of progression or recurrence in ovarian cancer.

In this study, to clarify the potential effects of PAX2 on ovarian cancer recurrence, the association between PAX2 expression and progression-free survival time was examined. In addition, mass spectrometry-based iTRAQ proteomic profiles were employed to illuminate the underlying mechanisms of action of PAX2.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

RM cells were derived from immortalized mouse ovarian surface epithelial cells transduced with retroviral constructs to achieve ectopic expression of mutant K-Ras (KRASG12D) and Myc as previously described (5).

Construction of cell lines

The construction of the RM-PAX2 and RM-pWPI cell lines has been described in detail previously (5). Briefly, the murine Pax2 cDNA (pax2-b variant) was cloned from murine oviduct and inserted into the Not I site of pWPI (Addgene plasmid 12254) to generate a lentivirus expression vector (WPI-Pax2-IRES-eGFP, hereafter pWPI-Pax2). The empty pWPI vector was used as a control. The vector plasmids (pWPI or pWPI-Pax2), packaging plasmid pCMVR8.74 (Addgene plasmid 22036), and the ecotropic envelope expression plasmid, pCAG-Eco (Addgene plasmid 35617) were co-transfected into 293T cells (ATCC® CRL-3216™) to generate lentivirus. RM cells were infected with lentivirus and then passaged at least 3 times prior to sorting for GFP expression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Cell proliferation assay

The RM, RM-WPI or RM-PAX2 cells (5×104) were plated in 6-well plates for 72-h growth assays. Cell numbers were counted using a Vi-Cell™ XR cell viability analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

In vivo tumorigenesis experiment

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care's Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals under a protocol approved by the University of Ottawa's Animal Care Committee. Mice were maintained in a dedicated room for immune-compromised mice (21̊C, 40-60% humidity, 12/12 h light/dark cycle). A commercial rodent diet (2018 Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, ID, USA) along with acidified water was available ad libitum. Housing, food and water were autoclaved, and all animal manipulations were carried out in a certified ESCO-type A2 BSC hood, following a two-person dirty/clean protocol. Mice were allowed a 1-week acclimation period prior to the initiation of any experimental manipulations.

The RM-WPI or RM-PAX2 cells (1×107 in 500 µl PBS) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of eight 8-week-old SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory), separately. The mice injected with RM-PAX2 cells intraperitoneally had an average weight of 17.7 g at the time of purchase, and the average weight of RM-WPI group was 18.8 g. No analgesics or anesthetics were administered to the mice for the i.p. injection of cells, as i.p. injections are considered routine procedures, are performed quickly and do not appear to be very painful to the mice. Eight mice were assigned to each group. Disease progression was monitored and the mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation once a humane endpoint was reached (rapid changes in weight, loss or gain of >5 g compared to the average body weight of control mice of the same age, presence of respiratory distress, a palpable mass or abdominal distention that impairs mobility). For euthanasia, the flow rate of medical-grade CO2 was 1.5 litres/min to deliver a 30% change in the chamber volume/min. The mice were kept in the CO2 chamber for 3-5 min until they did not respond to pain stimuli (pinching tails and paws). Tumors were then excised, imaged by fluorescent microscopy (EVOS Imaging Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific), fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h, paraffin-embedded and sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm for histological analysis. Alternatively, tumor samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein analysis.

Patient samples

The tissue microarrays (TMA) consisted of specimens from 152 patients who were diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer and treated from 2005 to 2013. Among these, 131 specimens were generous gifts from the Affiliated Qilu Hospital of Shandong University and the remaining were from the Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital. The pathological diagnosis of specimens in the TMAs was reviewed by senior pathologists of that same institution. Three tissue samples used for western blot analysis were from patients who were diagnosed with high-grade serous ovarian cancer and followed by radical hysterectomy at the Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital, and no malignant lesions in ampulla of oviduct was proved by pathology. Patient informed consents were obtained prior to the experiments and the protocols were approved by the Ethics Review Committees of both the Affiliated Qilu Hospital of Shangdong University and the Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital.

The ages of the 152 patients with ovarian serous carcinoma were 33 to 79 years, with an average age of 54.9±9.9 years. The median time of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) was 52.0 and 28.0 months, respectively. The patient clinical information is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Pathological features of the 152 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

| Features | Classification of cases | Case (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Vital state | Living | 68 |

| Deceased | 84 | |

| FIGOa | Stage I-II | 34 |

| Stage III-IV | 118 | |

| Pathological grade | G0-1 | 5 |

| G2-3 | 147 | |

| Serum CA125 level (U/ml) | ≤500 | 61 |

| >500 | 91 | |

| TP53 expression | Negative | 45 |

| Weakly positive | 23 | |

| Strongly positive | 84 | |

| RAS expression | Negative | 20 |

| Positive | 132 | |

| PAX2 expression | Negative | 48 |

| Positive | 104 | |

| ACAA2 expression | Low | 60 |

| High | 92 | |

| PNLIP | Low | 126 |

| High | 26 |

Patients were diagnosed at stage I-IV according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).

All patients were followed-up eacg month in the first year following surgery, every 3 months in the second year, every 6 months in the third year, and once every 3 years thereafter. The endpoint was the appearance of tumor progression (including recurrence not controlled with treatment, or death). The follow-up time ranged from 5 to 129 months (average, 43±25 months). PFS was determined as the period from the day of surgery to the time of disease recurrence. Those who did not recur and survived beyond April 1, 2016 were recorded as censored data.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The expression of PAX2, RAS, acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 2 (ACAA2) and pancreatic lipase (PNLIP) was determined by immunohisto-chemistry using the Immunohistochemistry Envision HRP kit (cat. no. KIT-5004, Maixin Biotechnologies), rabbit-anti-PAX2 antibody (cat. no. ab150391, Abcam), rabbit-anti RAS antibody [Ras (D2C1), rabbit mAb, cat. no. #8955, Cell Signaling Technology], rabbit-anti ACAA2 antibody (cat. no. PAS78709, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and rabbit-anti PNLIP (cat. no. PA5-80956, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Optimal dilution ratio of primary antibodies was 1:100.

The percentage of positive cells in each specimen and the staining intensity were independently evaluated and scored by two senior pathologists. When scored for the percentage of positive cells, '0' stands for no positive cells, '1' for 1-25, '2' for 26-50, '3' for 51-75 and '4' for 76-100%. When scored for staining intensity, '0' stands for no coloring, '1' for pale yellow, '2' for brown and '3' for deep brown. The final scores were the multiple of these two scores. For PAX2, the total score 0 was defined as negative, ≤6 was weak expression and >6 was strong expression. For RAS, 0 was defined as negative, >0 was positive; for ACAA2, 0 was defined as negative, <5 was low expression, and ≥5 was high expression; for PNLIP, 0 was defined as negative, <5 was low expression, and ≥6 was high expression.

iTRAQ proteomics profiling

Tumor tissues from the murine RM model expressing either PAX2 or not were ground under liquid nitrogen and the protein was extracted using the ProteoExtract® Complete Mammalian Proteome Extraction kit (cat. no. 539779, Merck Millipore) and quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (cat. no. 23227, Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples were then reduced, alkylated, digested and labeled with iTRAQ reagents according to the recommended protocol (iTraq Reagent 8 plex buffer kit, cat. no. P/N4381664; iTraq Reagent 8 plex Multiplex kit, cat. no. P/N4381663; Applied Biosystems). The samples were labeled as follows: RM-PAX2, iTraq reagents 117 and 118; RM-WPI iTraq reagents 119 and 121. Following iTRAQ labeling, samples were fractionated by HPLC and analyzed by high-resolution LC-MS/MS. Quantitative global proteome analysis was performed in the PTM Biolabs (https://www.ptmbiolabs.com/). Bioinformatics analysis was carried out to annotate quantifiable targets by protein annotation, functional classification, functional enrichment, functional enrichment-based cluster analysis, etc.

Gene Ontology (GO) annotation proteome was derived from the UniProt-GOA database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA/). Identified protein IDs were first converted to UniProt ID and then mapped to GO IDs by protein ID. If some identified proteins were not annotated by the UniProt-GOA database, InterProScan software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) was used to determine the GO function based on a protein sequence alignment method. Proteins were then classified by the GO annotation based on 3 categories: Biological process, cellular component and molecular function.

Western blot analysis

Protein extracts were prepared by cell lysis using RIPA Buffer. Protein concentrations were quantified using the Quick Start Bradford Protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins (40 µg) were separated on 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Western blot analysis was performed using primary antibodies from Abcam as follows: Rabbit anti-PAX2 (ab150391), fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4; ab92501), LIPA (ab219113), PNLIP (ab198181), ACAA2 (ab237540) at a 1:1,000 dilution and the secondary antibody reagent, anti-rabbit DAKO EnVision-system-HRP solution (cat. no. K4002, Dako Cytomation). Immuno-reactive bands were visualized using an ECL western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare) and the Syngene Bio-Imaging System program (PerkinElmer).

Kaplan-Meier plotter

The online meta-analysis tool 'The Kaplan Meier plotter' (http://kmplot.com/analysis/, accessed 22 December 2018) was used to assess the effects of gene expression on survival using data for 1,001 patients with stage III-IV serous ovarian cancer. The cut-off value for high or low expression was automatically determined by the Kaplan Meier plotter. The follow-up threshold was set at 60 months. The GEO datasets and TCGA datasets, as well as the bioinformatics processing used by this online tool were previously described (13,14). Biased assays and assays with a false discovery rate (FDR) of >20% were excluded.

Statistical analyses

On the basis of the number of conditions tested, statistical significance was determined by the t-test, ANOVA (Tukey's post-test), or log-rank test (Kaplan-Meier), performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.) or SPSS20.0 (IBM).

Results

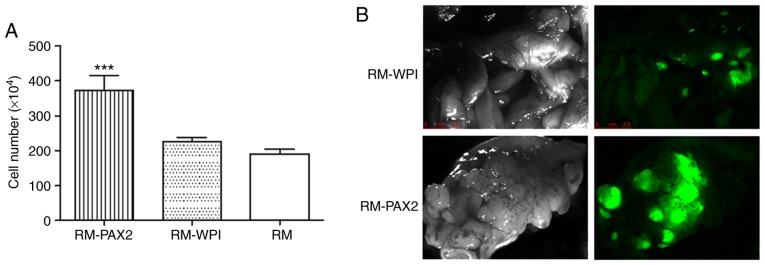

PAX2 promotes cell proliferation in vitro

Previously, the expression of PAX2 in the RM model of ovarian cancer was shown to enhance cell proliferation (5). The expression of PAX2 in the RM-PAX2 cell line was shown in a previous study [please see Fig. 4A in the study by Alhujaily et al (5)]. In this study, the cell proliferation assay confirmed that PAX2 expression led to an enhanced proliferation (Fig. 1A).

Figure 4.

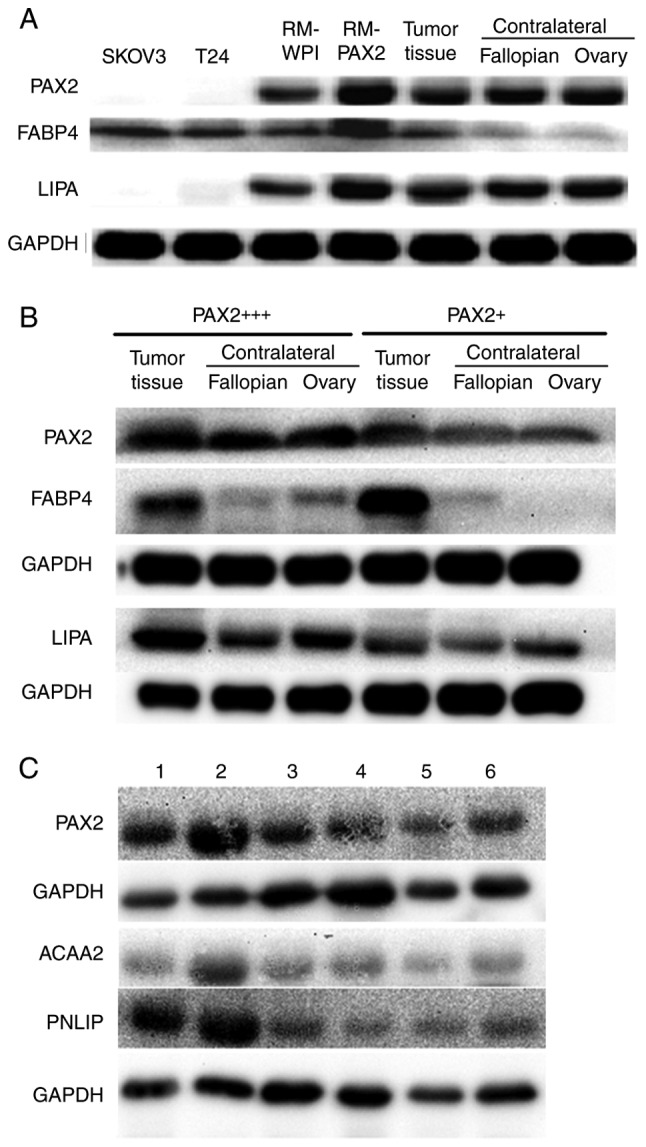

PAX2 promotes fatty acid metabolism reprogramming in RM tumors and ovarian cancer tissues. (A) Western blot analysis of the expression of PAX2, FABP4 and LIPA in RM-WPI or RM-PAX2 tumor tissue, contralateral ovarian and fallopian tube tissues, and from a case of human serous ovarian cancer. SKOV3 and T24 cell lines were used as negative controls for PAX2 expression. (B) Western blot analysis of the expression of PAX2, FABP4 and LIPA in cancer tissues from PAX2 strong (PAX2+++) or weak (PAX2+) serous ovarian cancer patients. Non-cancerous contralateral ovarian and fallopian tube tissues were also analyzed. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representative of 3 replicate experiments. PAX2 and FABP4 were probed from the same membrane, LIPA was probed from another membrane. (C) Western blot analysis of the expression of PAX2, PNLIP and ACAA2 in cancer tissues from an additional six serous ovarian cancer patients. PAX2 and ACAA2 were probed from the same membrane, PNLIP was probed from membrane. PAX2, paired box 2.

Figure 1.

PAX2 promotes RM cell proliferation and tumorigenicity. (A) Overexpression of PAX2 increases the proliferation of the RM cells compared to that of RM-WPI cells (***P<0.05). (B) RM-WPI and RM-PAX2 cells form numerous tumors in the peritoneum of IP injected SCID immune-deficient mice, as detected by GFP fluorescence. The images were acquired when the mice were sacrificed when the endpoint was met. PAX2, paired box 2.

PAX2 enhances tumorigenesis in vivo

To confirm the effects of PAX2 on tumorigenesis in vivo, the RM-WPI and RM-PAX2 cells were injected intraperitoneally into SCID mice. As observed under a fluorescence microscope, both RM-WPI and RM-PAX2 cells formed tumors. Compared to the RM-WPI cells, the RM-PAX2 cells seemed to form larger tumors and spread throughout the peritoneum, to the pancreas, liver, intestine, diaphragm, uterus and ovaries (Fig. 1B). As has been previously demonstrated (5), the survival time was markedly decreased in SCID mice injected with RM-PAX2 cells compared to those injected with RM-WPI cells [median survival, 11 vs. 16 days; please see Fig. 4E in the study by Alhujaily et al (5)].

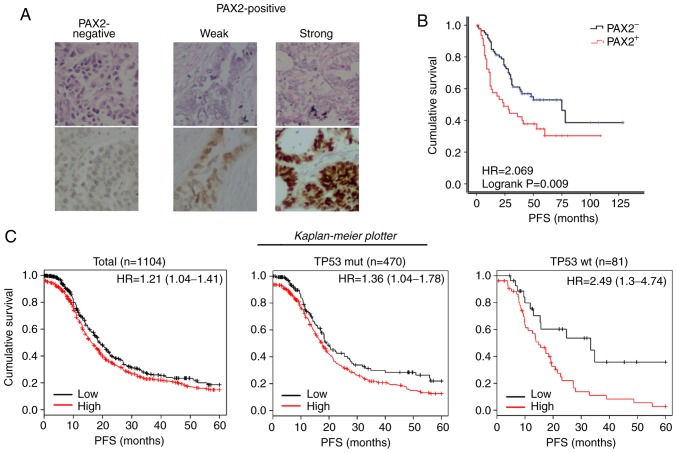

PAX2 overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer

Although the role of PAX2 in tumorigenesis remains undetermined, its expression was found to increase the tumor burden and shorten the survival of mice injected with RM cells. This result led us to investigate its role in ovarian cancer progression. First, a cohort of 152 epithelial ovarian cancer cases was identified. The patients were separated into the PAX2-positive (PAX2+, including both weak and strong expression) and PAX2-negative (PAX2-) groups according to the expression of PAX2 examined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2A). In agreement with the findings of this study on the RM model, the PFS of the PAX2+ patients was significantly reduced compared to that of the PAX2- patients (median survival of 24.0 vs. 75.0 months; Fig. 2B). Using the online meta-analysis tool, The Kaplan Meier plotter revealed that a high expression of PAX2 were associated with the shortened PFS of patients with stage III-IV serous ovarian cancer (Total: 16.1 vs. 19.0 months; TP53 mutant subgroup: 17.3 vs. 19.0 months; TP53 wild-type subgroup: 14.8 vs. 33.3 months, all P<0.05, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

PAX2 overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer. (A) Typical TMA samples of negative, weak and strong PAX2 expressions, examined by immunohistochemistry. Top panels, H&E staining; bottom panels, immunohistochemical staining of PAX2. (B) Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curves for patients with negative PAX2 expression (PAX2-) or positive PAX2 expression (PAX2+) according to the results as shown in (A). (PAX2-, n=48; PAX2+, n=105). (C) Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curves for 1,001 patients with stage III-IV serous ovarian cancer with a high PAX2 expression (PAX2+) or low PAX2 expression (PAX2−) using 'The Kaplan Meier plotter' (http://kmplot.com/analysis/, accessed December 22, 2018). Left panel, total; middle panel, TP53 mutant subgroup; right panel, TP53 wild-type subgroup. PAX2, paired box 2.

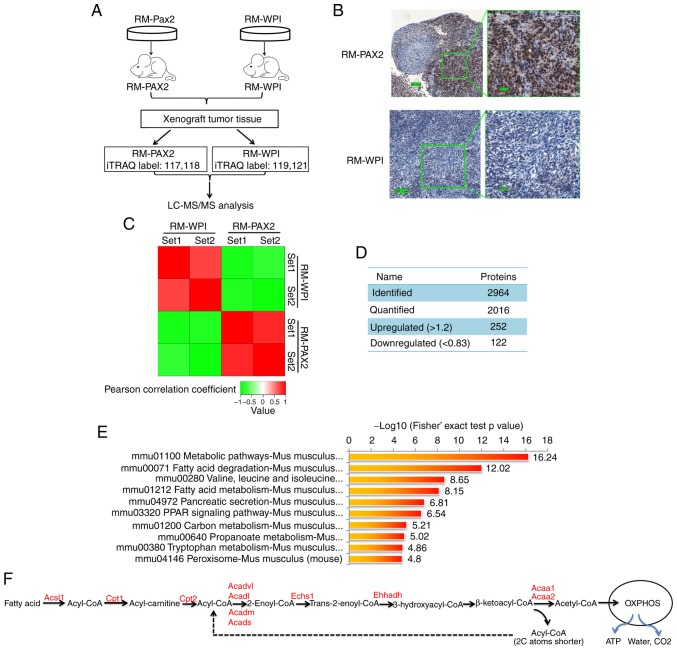

iTRAQ proteomics profiling of PAX2 overexpressing tumor tissues

To further elucidate the mechanisms through which PAX2 affects ovarian cancer progression, iTRAQ proteomic technology was exploited to identify differentially expressed proteins between RM-PAX2 and RM-WPI tumors (Fig. 3A). The expression of PAX2 in these tissue samples was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3B). In total 2,964 proteins were identified from the mouse tumors, of which 2,016 proteins were quantified. When setting quantification ratio thresholds of >1.2 as upregulated and <0.83 as downregulated, in a comparison of protein expression in RM-PAX2 vs. RM tumors, 252 proteins were upregulated and 122 proteins were downregulated (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

iTRAQ proteomics profiling of RM tumors overexpressing PAX2. (A) An overview of the workflow employed in this study. Two iTRAQ replicates were carried out to ensure the consistency and reliability of the results. (B) Expression of PAX2 in allograft RM tumors was confirmed by immunohisto-chemistry. (C) Reproducibility analysis of 2 repeated trials by Pearson's correlation coefficient. (D) Summary of identified and quantified proteins. (E) KEGG pathway-based enrichment analysis of up-regulated proteins (RM-PAX2 vs. RM-WPI). (F) Fatty acid metabolism. Enzymes upregulated by PAX2 overex-pression are indicated in red color. PAX2, paired box 2; Acsl, long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 1; Cpt1, carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase 1; Cpt2, Carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase 2; Acadl, long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial; Acadvl, very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial; Acads, short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondria; Acadm, medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial; Echs1, Enoyl-CoA hydratase; Ehhadh, peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme; Acaa1, 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase A; Acaa2, 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, mitochondrial.

KEGG signaling pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the top upregulated signaling pathways in RM-PAX2 xenograft tumors were those that regulate cell metabolism, particularly fatty acid metabolism (Fig. 3E and F). The most downregulated signaling pathways were those that regulate cell cycle, extracellular matrix receptor interaction and cell junctions (data not shown).

PAX2 promotes fatty acid metabolic reprogramming in RM cells and ovarian cancer tissues

The marked upregulation of cell metabolic pathways suggests that PAX2 may promote the reprogramming of tumor cell metabolism to support cell survival. Fatty acid catabolism involves fatty acid activation, translocation to the mitochondria and β-oxidation. In the cytoplasm, fatty acid is activated by Acyl-CoA synthetase (Acsl), which catalyzes fatty acid into fatty acyl-CoA (15). Subsequently, fatty acyl-CoA is transferred into the mitochondria by carnitine acyltransferase I (Cpt1) and carnitine acyltransferase II (Cpt2). Cpt1 is the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid metabolism. After fatty acyl-CoA enters the mitochondrial matrix, it decomposes into acetyl-CoA catalyzed by a series of fatty acid β-oxidases, including Echs1, Acads, Acadm, Acadl, Acadvl, Acaa1 and Acaa2 (Fig. 3F). The acetyl-CoA finally enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle and is completely degraded to water, CO2 and ATP through oxidative phosphorylation by the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Fig. 3F). In the PAX2-overexpressing allograft tumor tissue, almost all enzymes involved in fatty acid metabolism were significantly increased, as shown in Fig. 3F and Table II (all P<0.05).

Table II.

Differentially expressed proteins in the fatty acid metabolism pathway identified by iTRAQ.

| Process | Protein accession no. | Gene | Protein description | RM-PAX2/RM-WPI ratio | Regulated type | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | P32114 | Pax2 | Paired box protein Pax-2 | 2.83 | Up | 0.024 |

| Q8BWT1 | Acaa2 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, mitochondrial | 2.06 | Up | 0.0101 | |

| O35459 | Ech1 | Delta(3,5)-Delta(2,4)-dienoyl-CoA isomerase, mitochondrial | 1.74 | Up | 0.0036 | |

| Q9DBM2 | Ehhadh | Peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme | 1.71 | Up | 0.0032 | |

| Q61425 | Hadh | Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.69 | Up | 0.0012 | |

| Q8BH95 | Echs1 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase, mitochondrial | 1.69 | Up | 0.0418 | |

| P51174 | Acadl | Long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.64 | Up | 0.0386 | |

| Q921H8 | Acaa1a | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase A, peroxisomal | 1.57 | Up | 0.0249 | |

| Q9R0H0 | Acox1 | Peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 | 1.48 | Up | 0.0436 | |

| P50544 | Acadvl | Very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.48 | Up | 0.0435 | |

| Q07417 | Acads | Short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.44 | Up | 0.0039 | |

| P45952 | Acadm | Medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.35 | Up | 0.0346 | |

| O08756 | Hsd17b10 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase type-2 | 1.27 | Up | 0.0096 | |

| Fatty acid activation | P41216 | Acsl1 | Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 1 | 2.25 | Up | 0.0093 |

| Q8JZR0 | Acsl5 | Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 5 | 1.39 | Up | 0.0496 | |

| P97742 | Cpt1a | Carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase 1, liver isoform | 1.59 | Up | 0.0006 | |

| P52825 | Cpt2 | Carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase 2, mitochondrial | 1.31 | Up | 0.0469 | |

| Fatty acid absorption | Q6P8U6 | Pnlip | Pancreatic triacylglycerol lipase | 2.35 | Up | 0.0272 |

| Q5BKQ4 | Pnliprp1 | Inactive pancreatic lipase-related protein 1 | 5.25 | Up | 0.0058 | |

| P17892 | Pnliprp2 | Pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 | 2.47 | Up | 0.0419 | |

| P12710 | Fabp1 | Fatty acid-binding protein, liver | 2.91 | Up | 0.0393 | |

| P04117 | Fabp4 | Fatty acid-binding protein, adipocyte | 2.31 | Up | 0.0157 | |

| Fatty acid synthesis | P19096 | Fasn | Fatty acid synthase | 0.98 | - | 0.4045 |

Up, upregulated.

The above-mentioned results suggested that PAX2 promoted fatty acid metabolism in RM tumors; however, it is unclear whether fatty acid substrates arose through de novo synthesis or by uptake from surrounding adipocytes. Lipases and fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are required for transferring lipids from adipocytes to cancer cells (16). In RM-PAX2 tumors, Pnlip, inactive pancreatic lipase-related protein 1 (Pnliprp1) and pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 (Pnliprp2) were elevated 2.35, 5.45 and 2.47-fold. Murine homologues of FABPs, Fabp1 and Fabp4 were also increased by 2.31- and 2.91-fold, respectively (Table II). Moreover, the expression of fatty acid synthase (Fasn), a key enzyme for fatty acid synthesis, was not altered (Table II).

To confirm the fatty acid metabolic reprogramming discovered by iTRAQ analysis, the expression of FABP4 and a lipase (LIPA) was analyzed in tumor tissue from both the murine RM-PAX2 model and patients with ovarian cancer. The FABP4 and LIPA expression levels were upregulated in the RM-PAX2 tumor tissue compared to the RM-WPI tissue (Fig. 4A). In accordance with the murine model, the expression of FABP4 and LIPA was higher in the ovarian tumors exhibiting a strong PAX2 expression (PAX2+++) when compared to the tumors with a weak PAX2 expression (PAX2+) (Fig. 4B). While FABP4 was expressed at higher levels in tumors expressing high levels of PAX2, FABP4 was also upregulated in the PAX2-low expressing tumors when compared to the normal contralateral fallopian and ovary tissues (Fig. 4A and B). This indicates that even low levels of PAX2 may be sufficient to induce the expression of FABP4, or perhaps other factors in the tumor, in addition to PAX2, leads to the upregulation of FABP4.

The expression of PNLIP and ACAA2 was further examined in tumor tissues of 6 patients with serous ovarian cancer with varying levels of PAX2. The expression of PNLIP and ACAA seemed to increase along with that of PAX2 (Fig. 4C). However, when assessing the potential correlation of PAX2, PNLIP and ACAA2 expression in the TMA cohort in this study, Spearman's correlation coefficients among PAX2, PNLIP and ACAA2 were not found to be significant (data not shown). The expression levels of PAX2, PNLIP and ACAA2 in the TMA cohort were determined by immunohistochemistry, as indicated in the Material and methods section.

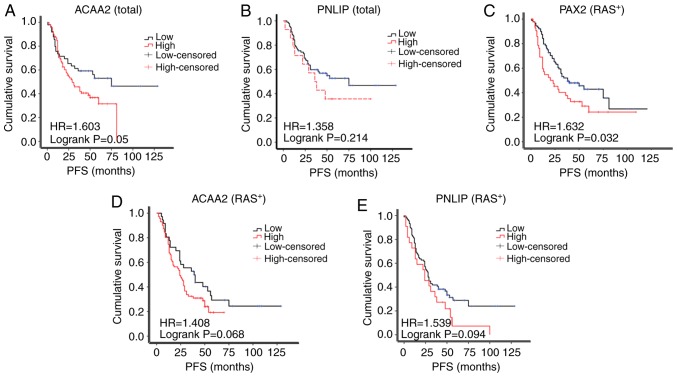

Based on the results of IHC, the patients were separated into the high or low expression subgroups. The PFS of ACAA2 in patients with a high expression was reduced compared to those with a low ACAA2 expression patients (median survival of 29.0 vs. 75.0 months; Fig. 5A). The PFS of patients with a high PNLIP expression also exhibited a trend of a reduced PFS compared to those with a low PNLIP expression (median survival of 38.0 vs. 48.0 months, Fig. 5B), although the differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

ACAA2 overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curves for patients with a low or high expression of (A) ACAA2 or (B) PNLIP among the total number of patients; (C-E) Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curves for patients with (C) a negative PAX2 expression (PAX2−) or positive PAX2 expression (PAX2+), (D) low or high ACAA2 expression or (E) low or high PNLIP in expression RAS positive (RAS+) subgroup.

The amplification of RAS signaling was common in epithelial ovarian cancer, but not the KRAS mutation which was used in the RM model in this study. Thus, the expression of RAS was further assessed in the TMA cohort in this study. As a result, 132 cases were RAS-positive, while only 20 was RAS-negative (Table I). In the RAS-positive subgroup, the PAX2+ patients exhibited a significantly shorter PFS compared with the PAX2- patients (median survival of 20.0 vs. 38.0 months, Fig. 5C). A high expression of ACAA2 or PNLIP in patients was also associated with a reduced PFS, although this was not statistically significant (29.0 vs. 56.0 months, 36.0 vs. 53.0 months, respectively, Fig. 5D and E). The RAS-negative subgroup was not analyzed due to the small sample size (n=20).

PAX2 upregulates OXPHOS but not glycolysis in RM cells

The dependency of cancer cells on glycolysis, also known as the Warburg effect, was once recognized as the most outstanding feature of tumor cell metabolism (17) and was considered an essential property of most tumor cells, including ovarian cancer (18). It has been shown more recently that enhanced mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) also plays an important role in ovarian cancer (19). In this study, proteomics analysis revealed that a key enzyme for glycolysis, pyruvate kinase (Pkm) was downregulated by PAX2. Other enzymes involved in glycolysis and Glut1, the enzyme responsible for glucose uptake, were not significantly altered (Table III). By contrast, proteins participating in the OXPHOS pathway and components of mitochondrial electron transport chain were all significantly upregulated (Table III) in PAX2-expressing tumor tissues.

Table III.

Differentially expressed proteins in glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation identified by iTRAQ.

| Process | Protein accession no. | Gene | Protein description | RM-PAX2 RM-WPI ratio | Regulated type | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | P17809 | Slc2a1, Glut-1, Glut1 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 | 0.86 | - | 0.3308 |

| P17710 | Hk1 | Hexokinase-1 | 0.91 | - | 0.1620 | |

| O08528 | Hk2 | Hexokinase-2 | 0.83 | - | 0.2196 | |

| Q3TRM8 | Hk3 | Hexokinase-3 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Q8VDL4 | Adpgk | ADP-dependent glucokinase | 0.87 | - | 0.2782 | |

| P06745 | Gpi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 1.05 | - | 0.2221 | |

| P12382 | Pfkl | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, liver type | 0.77 | - | 0.2985 | |

| P47857 | Pfkm | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, muscle type | 0.73 | - | 0.1779 | |

| Q9WUA3 | Pfkp | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, platelet type | 1.15 | - | 0.1916 | |

| P05063 | Aldoc | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C | 0.71 | - | 0.0788 | |

| P05064 | Aldoa | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | 0.85 | - | 0.2419 | |

| P17751 | Tpi1 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 0.83 | - | 0.0141 | |

| P17182 | Eno1 | α-enolase | 0.79 | - | 0.1339 | |

| P21550 | Eno3 | β-enolase | 0.95 | - | 0.4925 | |

| P09411 | Pgk1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 0.97 | - | 0.8095 | |

| P09041 | Pgk2 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 2 | 0.99 | - | 0.9302 | |

| Q9DBJ1 | Pgam1 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 0.87 | - | 0.0648 | |

| P52480 | Pkm | Pyruvate kinase PKM | 0.77 | Down | 0.0236 | |

| Mitochondrial electron transport chain | Q8CIM7 | Cyp2d26 | Cytochrome P450 2D26 | 2.44 | Up | 0.0004 |

| Q64459 | Cyp3a11 | Cytochrome P450 3A11 | 2.20 | Up | 0.0498 | |

| P56395 | Cyb5a | Cytochrome b5 | 1.93 | Up | 0.0278 | |

| P48771 | Cox7a2 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7A2, mitochondrial | 1.31 | Up | 0.0175 | |

| Q91VR2 | Atp5f1c | ATP synthase subunit gamma, mitochondrial | 1.29 | Up | 0.0224 | |

| Q61941 | Nnt | NAD(P) transhydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.26 | Up | 0.0099 | |

| Q99LC3 | Ndufa10 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 10, mitochondrial | 1.26 | Up | 0.0453 | |

| Q9D855 | Uqcrb | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 7 | 1.25 | Up | 0.0130 | |

| P19783 | Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 isoform 1, mitochondrial | 1.23 | Up | 0.0107 | |

| Q9Z1P6 | Ndufa7 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1α subcomplex subunit 7 | 1.25 | Up | 0.0396 | |

| Tricarboxylic acid cycle | Q9CZU6 | Cs | Citrate synthase, mitochondrial | 1.14 | - | 0.1691 |

| Q9WUM5 | Suclg1 | Succinyl-CoA ligase [ADP/GDP-forming] subunit α, mitochondrial | 1.55 | Up | 0.0112 | |

| Q8K2B3 | Sdha | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial | 1.23 | Up | 0.0374 | |

| P97807 | Fh, Fh1 | Fumarate hydratase, mitochondrial | 1.21 | - | 0.0524 |

Up, upregulated; Down, downregulated.

Glutamate is also an important energy source for OXPHOS (20). Glutamate is transferred into cells primarily through the amino acid transporter (Slc1a5), but its expression was not affected by PAX2 (Table IV). Glutamate can also be generated through the degradation of amino acids. Given that the valine, leucine and isoleucine degeneration pathway was found to be significantly upregulated (Fig. 3E) and enzymes responsible for glutamate synthesis [alanine aminotransferase (Gpt), glutamate dehydrogenase (Glud1) and glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (Gcdh)] were increased (Table IV), it is possible that PAX2 also altered cellular glutamate metabolism.

Table IV.

Differentially expressed proteins in glutamate metabolism identified by iTRAQ.

| Protein accession no. | Gene | Protein description | RM-PAX2/RM-WPI ratio | Regulated type | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q60759 | Gcdh | Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1.96 | Up | 0.0477 |

| P26443 | Glud1 | Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, mitochondrial | 1.91 | Up | 0.0376 |

| Q8QZR5 | Gpt | Alanine aminotransferase 1 | 1.91 | Up | 0.0204 |

| P51912 | Slc1a5 Aaat, Asct2, Slc1a7 | Neutral amino acid transporter B(0) | 1.00 | - | 0.8484 |

Up, upregulated.

Enhanced fatty acid catabolism pathway is associated with a poor prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer

As the high expression of PAX2 and ACAA2 shortened the PFS of patients with ovarian cancer (Figs. 2B and 5C), whether the upregulation of fatty acid metabolism is also associated with a shorter PFS was then determined. All genes listed in Table II were analyzed. The results of the Kaplan-Meier plotter analysis clearly revealed that a high expression of FABP4 and ACAA2 were associated with the shortened PFS of patients with serous ovarian cancer (Table V); this was observed in all patients regardless of the TP53 status.

Table V.

Association of enzymes of fatty acid catabolism with the duration of the progression-free survival of patients with serous ovarian cancer.

| Gene | Probe | Expression | Number | PFS (months) | P-value | FDR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FABP4 | 203980_at | Low | 568 | 19 | 2.40E-06 | 1 |

| High | 433 | 13.17 | ||||

| ACAA2 | 202003_s_at | Low | 617 | 18.07 | 0.0011 | 20 |

| High | 384 | 14 | ||||

| ACADVL | 200710_at | Low | 739 | 17.6 | 0.00045 | 20 |

| High | 262 | 14 |

PFS, progression-free survival; FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

In this study and as previously demonstrated (8), it was found that Pax2 gene expression enhanced the growth of tumors in a model of murine ovarian cancer both in vitro and in vivo. PAX2 expression in RM tumors reduced the length of survival of SCID mice. Proteomics analysis was then performed to define the possible mechanisms through which PAX2 accelerates ovarian tumor progression. The analysis of the proteome in RM-PAX2 tumors indicated that PAX2 promoted fatty acid metabolism in this murine model and this finding was extended to human ovarian carcinomas. Upregulated fatty acid metabolism may contribute to the shortened PFS of patients with serous ovarian cancer (Fig. 5 and Table V). These results highlight a novel mechanism through which PAX2 expression may promote ovarian cancer progression.

PAX2 is a specific Müllerian marker for ovarian serous carcinomas (21). In vivo, PAX2 has been shown to exhibit an oncogenic behavior, as the silencing PAX2 of has been shown to result in decreased tumor volume or enhanced cisplatin-induced tumor regression in xenograft models of human endometrioid, colon and renal carcinoma cells (10-12). However, the effects of PAX2 expression on ovarian cancer prognosis remain unclear. A previous study reported that PAX2 overexpression decreased the survival of SCID mice (5). In this study, a shortened PFS was associated with higher levels of PAX2 expression (Fig. 2) in a cohort of patients with serous ovarian cancer.

Previous research has suggested that glycolysis is an important driver of ovarian cancer and inhibitors of glycolysis, such as 2-deoxy-glucose would benefit ovarian cancer patients (22). However, there is accumulating evidence to indicate that ovarian cancer cells exhibit an altered metabolic phenotype during progression (23). Metabolome studies have revealed that metabolites involved in fatty acid metabolism are increased in both primary ovarian tumors and their metastases (24). Abnormal phospholipid metabolism, altered l-tryptophan catabolism, aggressive fatty acid β-oxidation and the aberrant metabolism of piperidine derivatives have also been reported in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (25). In this study, it was found that the expression of PAX2 significantly upregulated the expression of enzymes involved in fatty acid metabolism, the mitochondrial OXPHOS pathway and components of the mitochondrial electron transfer chains (Figs. 3 and 4, and Table II). This would be predicted to promote the use of fatty acid as an energy source, depending on mitochondrial OXPHOS to produce ATP.

In addition to accelerating tumor growth, thereby shortening PFS, remodeled fatty acid metabolism and enhanced OXPHOS may contribute to resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. For example, higher basal content of intracellular mobile lipids and higher lipid accumulation within cytoplasmic droplets have been observed in a cisplatin-resistant ovarian cell line (26). Furthermore, the inhibition of fatty acid synthase has been found to render ovarian cancer cells more sensitive to cisplatin (27). The metabolic profile of cancer stem cells isolated from patients with epithelial ovarian cancer has been shown to be dominated by OXPHOS, and the overexpression of genes associated with glucose uptake, OXPHOS and fatty acid beta-oxidation. This OXPHOS profile was maintained in models of glucose deprivation both in vitro and in vivo and may be responsible for the resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies (28). A previous study found that PAX2 enhanced resistance to cisplatin and increased prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 (PTGS2 and COX2) in RM cells (5). The association between COX2 expression and fatty acid metabolism in ovarian cancers is unclear, although COX2 has been implicated in chemoresistance in ovarian cancers (29,30). Thus, fatty acid metabolic reprogramming induced by PAX2 may partly explain the enhanced resistance to platinum-based therapy and may lead to the more rapid recurrence of disease in patients with high levels of PAX2 expression.

Ovarian cancer has a clear predilection for metastasis to the omentum. Previous studies have revealed that primary human omental adipocytes promote the homing, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. The co-culture of omental adipocytes and ovarian cancer cells may induce lipolysis in adipocytes followed by uptake and beta-oxidation of the fatty acids in the cancer cells (16). In this manner, adipocytes may provide an energy source for the cancer cells. FABP4 expression has been detected in ovarian cancer cells at the adipocyte-tumor cell interface and may facilitate the transfer of lipids from adipocytes to ovarian cancer cells (16). RM-PAX2 cells formed larger tumors in the omentum and mesenteric adipose tissue, tissues that are rich of adipocytes (31). This study demonstrated a marked increase in the expression of several lipases and FABP4 in the RM-PAX2 tumors (Table II and Fig. 4A). In addition, FABP4 expression was associated with increased PAX2 expression in tissues from serous ovarian cancer patients (Fig. 4A and B). As RM-PAX2 cells formed larger tumors in the omentum and mesenteric adipose tissue, and those tissues were composed mostly of adipocytes, it is suggested that PAX2 enhances pathways that facilitate the uptake of fatty acids from surrounding adipocytes to promote their proliferation in the omentum. Further in vitro and in vivo research is required to confirm this mechanism.

Glutamate is another important substrate for oxidative phosphorylation in tumor cells with OXPHOS activity. A higher expression of glutamine synthetase in ovarian cancer patients has been shown to be associated with a worse disease-free and overall survival (32). Glutamate metabolic programming has been reported to play a role in the metastasis of many tumors (17). In this study, while enzymes responsible for glutamate uptake did not increase with the increased expression of PAX2 (Table IV), some enzymes in glutamate metabolism were up-regulated by PAX2 (Table IV). One function of glutamate metabolism is to maintain the redox status by regulating the intracellular glutathione (GSH) level in cells (33,34). The increased expression of the catalytic subunit of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase and the total GSH content has previously been implicated in doxorubicin resistance in ovarian cancer (33). In addition, glutamine, which serves as the precursor of glutamate, has been shown to increase the activity of glutaminase and glutamate dehydrogenase and to promote the proliferation of several ovarian cancer cell lines (34). This evidence suggests that PAX2-induced changes in the glutamate metabolism pathway can also influence cell proliferation or chemoresistance by affecting the intracellular redox status.

Based on the results of this study, PAX2 may be a marker which can be used to identify individuals who will benefit from treatment targeting fatty acid metabolism or OXPHOS. Currently, certain drugs have exhibited potential. For example, orlistat decreases tumor fatty acid metabolism by inhibiting fatty acid synthase, and combined treatment with orlistat and cisplatin enhances apoptotic and necrotic cell death in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells (35). Statins, a drug widely used to prevent and treat hypercholesterolemia, which blocks cholesterol synthesis, can prevent the development of ovarian cancer (36). Metformin inhibits mitochondrial OXPHOS and can also reverse cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells (37). In addition, therapeutic siRNA delivery targeting mouse endothelial FABP4 has been shown to markedly inhibit the angiogenesis, growth and metastasis if ovarian tumor xenografts (38).

In conclusion, the findings of this study demonstrated that PAX2 expression promoted the growth of the RM murine model of ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo, and reduced the length of survival of allografted SCID mice. A high expression of PAX2 also shortened the PFS of patients with serous ovarian cancer. PAX2 may promote fatty acid metabolism in serous ovarian cancer, which may be responsible for the shortened PFS.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Didier Trono for providing plasmids pPWI (Addgene plasmid #12254) and pCMVR8.74 (Addgene plasmid #22036) and Dr Arthur Nienhuis for providing plasmid pCAGEco (Addgene plasmid #35617). The authors would also like to thank Professor Beihua Kong of Affiliated Qilu Hospital of Shandong University for providing tissue arrays of ovarian cancer.

Funding

This study was funded in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81360341, 81560428 and 81860459), the National High-Tech Research and Development Program (863 Program) (no. 2014AA020605) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (nos. 2018GXNBSFBA138033 and 2018GXNSFAA138060).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors' contributions

QW, KG and BCV were responsible for the conception and design of the experiments. YF, YT, YM, YL, DY, LY contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. YF drafted the manuscript. KG, BCV and QW revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for this research was obtained from the patients prior to surgery. The Ethics Review Committee of Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital approved the present study. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care's Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals under a protocol approved by the University of Ottawa's Animal Care Committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perets R, Wyant GA, Muto KW, Bijron JG, Poole BB, Chin KT, Chen JY, Ohman AW, Stepule CD, Kwak S, et al. Transformation of the fallopian tube secretory epithelium leads to high-grade serous ovarian cancer in brca; tp53; pten models. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M, Ma H, Pan Y, Xiao W, Li J, Yu J, He J. PAX2 and PAX8 reliably distinguishes ovarian serous tumors from mucinous tumors. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23:280–287. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song H, Kwan SY, Izaguirre DI, Zu Z, Tsang YT, Tung CS, King ER, Mok SC, Gershenson DM, Wong KK. PAX2 expression in ovarian cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:6090–6105. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alhujaily EM, Tang Y, Yao D, Carmona E, Garson K, Vanderhyden BC. Divergent roles of PAX2 in the Etiology and Progression of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2015;8:1163–1173. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0121-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maulbecker CC, Gruss P. The oncogenic potential of Pax genes. EMBO J. 1993;12:2361–2367. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muratovska A, Zhou C, He S, Goodyer P, Eccles MR. Paired-Box genes are frequently expressed in cancer and often required for cancer cell survival. Oncogene. 2003;22:7989–7997. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen EY, Mehra K, Mehrad M, Ning G, Miron A, Mutter GL, Monte N, Quade BJ, McKeon FD, Yassin Y, et al. Secretory cell outgrowth, PAX2 and serous carcinogenesis in the Fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2010;222:110–116. doi: 10.1002/path.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robson EJ, He SJ, Eccles MR. A PANorama of PAX genes in cancer and development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:52–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang HS, Yan XB, Li XB, Fan L, Zhang YF, Wu GH, Li M, Fang J. PAX2 Protein induces expression of cyclin D1 through activating AP-1 protein and promotes proliferation of colon cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44164–44172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang LP, Shi XY, Zhao CY, Liu YZ, Cheng P. RNA interference of pax2 inhibits growth of transplanted human endometrial cancer cells in nude mice. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:400–406. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hueber PA, Iglesias D, Chu LL, Eccles M, Goodyer P. In vivo validation of PAX2 as a target for renal cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penzvalto Z, Lanczky A, Lenart J, Meggyesházi N, Krenács T, Szoboszlai N, Denkert C, Pete I, Győrffy B. MEK1 is associated with carboplatin resistance and is a prognostic biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:837–837. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Szallasi Z. Implementing an online tool for genome-wide validation of survival-associated biomarkers in ovarian-cancer using microarray data from 1287 patients. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2012;19:197–208. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marín-García J. Mechanisms of bioenergy production in mitochondria. Springer; Boston, MA: 2013. pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR, Romero IL, Carey MS, Mills GB, Hotamisligil GS, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med. 2011;17:1498–1503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellenberger LD, Bruin JE, Greenaway J, Campbell NE, Moorehead RA, Holloway AC, Petrik J. The role of dysregulated glucose metabolism in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Oncol. 2010;2010:514310. doi: 10.1155/2010/514310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim HY, Ho QS, Low J, Choolani M, Wong KP. Respiratory competent mitochondria in human ovarian and peritoneal cancer. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chivukula M, Dabbs DJ, O'Connor S, Bhargava R. PAX 2: A novel Mullerian marker for serous papillary carcinomas to differentiate from micropapillary breast carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:570–578. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181a76fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priebe A, Tan L, Wahl H, Kueck A, He G, Kwok R, Opipari A, Liu JR. Glucose deprivation activates AMPK and induces cell death through modulation of Akt in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson AS, Roberts PC, Frisard MI, McMillan RP, Brown TJ, Lawless MH, Hulver MW, Schmelz EM. Metabolic changes during ovarian cancer progression as targets for sphingosine treatment. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1431–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong MY, McDunn J, Kakar SS. Identification of metabolites in the normal ovary and their transformation in primary and metastatic ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ke C, Hou Y, Zhang H, Fan L, Ge T, Guo B, Zhang F, Yang K, Wang J, Lou G, Li K. Large-scale profiling of metabolic dysregulation in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:516–526. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montopoli M, Bellanda M, Lonardoni F, Ragazzi E, Dorigo P, Froldi G, Mammi S, Caparrotta L. 'Metabolic reprogramming' in ovarian cancer cells resistant to cisplatin. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:226–235. doi: 10.2174/156800911794328501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauerschlag DO, Maass N, Leonhardt P, Verburg FA, Pecks U, Zeppernick F, Morgenroth A, Mottaghy FM, Tolba R, Meinhold-Heerlein I, Bräutigam K. Fatty acid synthase over-expression: Target for therapy and reversal of chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. J Transl Med. 2015;13:146–146. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0511-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasto A, Bellio C, Pilotto G, Ciminale V, Silic-Benussi M, Guzzo G, Rasola A, Frasson C, Nardo G, Zulato E, et al. Cancer stem cells from epithelial ovarian cancer patients privilege oxidative phosphorylation, and resist glucose deprivation. Oncotarget. 2014;5:4305–4319. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raspollini MR, Amunni G, Villanucci A, Boddi V, Taddei GL. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and P-glycoprotein-170 (MDR1) expression is associated with chemotherapy resistance and poor prognosis. Analysis in ovarian carcinoma patients with low and high survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:255–260. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrandina G, Lauriola L, Zannoni GF, Fagotti A, Fanfani F, Legge F, Maggiano N, Gessi M, Mancuso S, Ranelletti FO, Scambia G. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression is associated with chemotherapy resistance and outcome in ovarian cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1205–1211. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chkourko Gusky H, Macdougald OA, Podgorski I. Omentum and bone marrow: How adipocyte-rich organs create tumour microenvironments conducive for metastatic progression. Obes Rev. 2016;17:1015–1029. doi: 10.1111/obr.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan S, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Lu J, Wu Z, Shan Q, Sun C, Wu D, Li M, Sheng N, et al. High expression of glutamate-ammonia ligase is associated with unfavorable prognosis in patients with ovarian cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:6008–6015. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shim GS, Manandhar S, Shin DH, Kim TH, Kwak MK. Acquisition of doxorubicin resistance in ovarian carcinoma cells accompanies activation of the NRF2 pathway. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;47:1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan L, Sheng X, Willson AK, Roque DR, Stine JE, Guo H, Jones HM, Zhou C, Bae-Jump VL. Glutamine promotes ovarian cancer cell proliferation through the mTOR/S6 pathway. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:577–591. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papaevangelou E, Almeida GS, Box C, deSouza NM, Chung YL. The effect of FASN inhibition on the growth and metabolism of a cisplatin-resistant ovarian carcinoma model. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:992–1002. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi Y, Kashima H, Wu RC, Jung JG, Kuan JC, Gu J, Xuan J, Sokoll L, Visvanathan K, Shih IeM, Wang TL. Mevalonate pathway antagonist suppresses formation of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and ovarian carcinoma in mouse models. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4652–4662. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matassa DS, Amoroso MR, Lu H, Avolio R, Arzeni D, Procaccini C, Faicchia D, Maddalena F, Simeon V, Agliarulo I, et al. Oxidative metabolism drives inflammation-induced platinum resistance in human ovarian cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1542–1554. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harjes U, Bridges E, Gharpure KM, Roxanis I, Sheldon H, Miranda F, Mangala LS, Pradeep S, Lopez-Berestein G, Ahmed A, et al. Antiangiogenic and tumour inhibitory effects of downregulating tumour endothelial FABP4. Oncogene. 2017;36:912–921. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.