Abstract

Protein regulator of cytokinesis-1 (PRC1) is a microtubule-associated factor involved in cytokinesis. Recent studies have indicated that PRC1 overexpression is involved in tumorigenesis in multiple types of human cancer. However, the expression, biological functions and the prognostic significance of PRC1 in ovarian cancer have not yet been clarified. In this study, it was confirmed that the PRC1 mRNA and protein expression levels were upregulated in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) tissues, particularly in patients without breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA) pathogenic mutations. PRC1 overexpression contributed to drug resistance, tumor recurrence and a poor prognosis. The findings also indicated that PRC1 knockdown decreased the proliferation, metastasis and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. It was also demonstrated that forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) regulated the mRNA and protein expression of PRC1. Dual-luciferase reporter assay and rescue assay confirmed that PRC1 was a direct crucial downstream target of FOXM1. On the whole, the findings of this study confirmed that PRC1 was a major prognostic factor of HGSOC and a promising therapeutic biomarker for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Keywords: protein regulator of cytokinesis-1, prognosis, drug resistance, breast cancer susceptibility gene, high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer is a fatal gynecological malignancy, resulting in 295,414 new cases and 184,799 deaths worldwide in 2018 (1), exhibiting an upward trend (1,2). High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) is the most common subtype (70%) associated with a higher degree of malignancy and a poorer prognosis (3). However, the molecular pathogenesis, the mechanisms of molecular regulation and drug resistance associated with HGSOC remain poorly characterized.

Protein regulator of cytokinesis-1 (PRC1), also known as Ase1 (yeast)/MAP65 (plant), was first identified as a CDK substrate in 1998 and was known as an essential microtubule associated protein required for cytokinesis via the phosphorylation of CDK1 (Cdc2/cyclin B) in early mitosis (4,5). Previous studies have found that cells in which PRC1 is knocked down can normally undergo interphase, prophase, prometaphase and metaphase, and chromatin can be equally distributed in the anaphase of mitosis; however, the structure of the central area of the spindle appears to be abnormal at anaphase, leading to the aberrant expression of cytokines and the formation of binuclear or multinucleated cells (5,6). Therefore, an abnormal expression of PRC1 can lead to aberrant cytokine expression, contributing to tumorigenesis and tumor progression.

It has already been demonstrated that PRC1 is upregulated in various types of tumor, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (7), gastric carcinoma (8) and pulmonary adenocarcinoma (9,10). The overexpression of PRC1 has been shown to significantly promoted the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells, and to be associated with early recurrence and a poor patient outcome by regulating the oncogenic effects of the Wnt signaling pathway (7). The knockdown of PRC1 has also been shown to significantly suppress the proliferation, reduce monolayer colony formation and to inhibit the invasive and migratory ability of gastric carcinoma cells (8). To date, however, at least to the best of our knowledge, the expression, biological functions and prognosis significance of PRC1 in ovarian cancer have not yet been elucidated.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

All evaluated HGSOC and fallopian tube (FT) tissues were collected from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital, Shandong University from 2006 to 2016. The 4 µm tissue microarrays (TMAs), including 210 cases of HGSOC and 42 normal FT tissues, were designed in our laboratory. Fresh tissues of 28 cases of HGSOC and 14 normal FT tissues were also collected. Moreover, 18 specimens with chemosensitivity information for second-line chemotherapy were obtained from the specimen library. HGSOC tissues were obtained from patients who underwent primary surgery and no neo-adjuvant chemotherapy was performed. The normal FT tissues were obtained from patients who received hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomies due to benign disease. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are presented in Table I. The accurate assessment of the disease response was based on RECIST or GCIG standards (11). Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shandong University, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Table I.

Association between PRC1 protein expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with HGOSC.

| Characteristic | No. of patients | PRC1 protein expression (n)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 0.333 | |||

| <55 | 97 | 42 | 55 | |

| ≥55 | 113 | 57 | 56 | |

| FIGO stage | 0.282 | |||

| I-II | 38 | 21 | 17 | |

| III-IV | 172 | 77 | 95 | |

| CA-125 | 0.870 | |||

| <500 U/ml | 54 | 25 | 29 | |

| ≥500 U/ml | 123 | 60 | 63 | |

| Ascites | 0.893 | |||

| <500 ml | 72 | 33 | 39 | |

| ≥500 ml | 126 | 59 | 67 | |

| Residual lesions | 0.567 | |||

| <1 cm | 133 | 61 | 72 | |

| ≥1 cm | 77 | 32 | 45 | |

| Family history | 0.891 | |||

| No | 161 | 74 | 87 | |

| Yes | 38 | 17 | 21 | |

| Platinum of first line | 0.019a | |||

| Sensitive | 87 | 40 | 47 | |

| Resistance | 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| Platinum of second line | 0.028a | |||

| Sensitive | 60 | 34 | 29 | |

| Resistance | 21 | 7 | 18 | |

| Primary recurrence | 0.127 | |||

| <6 months | 24 | 8 | 16 | |

| ≥6 months | 64 | 33 | 31 | |

| Secondary recurrence | 0.011a | |||

| <6 months | 16 | 5 | 11 | |

| ≥6 months | 15 | 12 | 3 | |

| Three-year survival | 0.006b | |||

| Alive | 89 | 55 | 34 | |

| Deceased | 54 | 20 | 34 | |

| Five-year survival | 0.003b | |||

| Alive | 72 | 47 | 25 | |

| Deceased | 71 | 28 | 43 | |

| BRCA mutation status | 0.019a | |||

| Pathogenic | 17 | 13 | 4 | |

| Non-pathogenic | 35 | 14 | 21 | |

P<0.05;

P<0.01. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma; BRCA, breast cancer susceptibility gene.

Cell lines and cell culture

The A2780 human ovarian cancer cell line was originally established from the tumor tissue of an untreated patient, and the cells grew as a monolayer and in suspension in spinner cultures. The SKOV3 cell line was originally isolated from the ascites of patients with ovarian tumors, and tumorigenesis in nude mice resulted in a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma consistent with carcinoma in situ of the ovary. The above-mentioned cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium and McCoy's 5A medium, respectively. 293T cells, which could continuously express SV40 antigen, was used in the transfection experiments with a high transfection efficiency, and was cultured in DMEM. The A2780 cell line was originally purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC; Cat. no. 93112519). The SKOV3 and 293T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Cat. nos. HTB-77 and CRL-11268, respectively). All the culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All these cells were cultured in a humidified incubator under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from cells and tissues was isolated using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). qPCR was performed using SYBR-Green qPCR master mix (Takara). The conditions for PCR indluced 3 stages: Hold stage (95°C, 30 sec), PCR stage for 40 cycles (95°C, 5 sec and 60°C, 34 sec), melt curve stage (95°C, 15 sec; 60°C, 1 min and 95°C, 15 sec).GAPDH served as the endogenous control. The primer sequences of PRC1 for RT-qPCR were as follows: Forward primer, ACA CTC TGT GCA GCG AGT TAC; reverse primer, TTC GCA TCA ATT CCA CTT GGG. The primer sequences of GAPDH were as follows: Forward, ACA ACT TTG GTA TCG TGG AAG G and reverse, GCC ATC ACG CCA CAG TTT C. The method of quantification was relative quantification and ΔΔcq was calculated to analyze the relative gene expression (12).

Plasmid construction and lentivirus production

A lentivirus vector expressing shPRC1 (TRCN0000280715) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. siRNA was synthesized by the GenePharma. The sequences were as follows: PRC1, 5′-CGC UGU UUA CUC AUA CAG U-3′; forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1), 5′-GGA CCA CUU UCC CUA CUU UUU-3′ and negative control (NC), 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG UdT dT-3′.

Lentivirus was produced in 293T cells packaged by psPAX2 and pMD2.G. The cells were infected with the 1 ml lentivirus liquid for 24 h in the presence of polybrene (8 µg/ml), and was selected with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for 1 week to acquire stable expressing cell lines. siRNA manipulation was performed in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen™). The time duration between transfection subsequent experimentation was approximately 10-14 h.

MTT assay

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was firstly used to measure the proliferative ability of the A2780 cells subjected to PRC1 knockdown or overexpression compared to the cells trans-fected with empty plasmid. The A2780 cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, and were seeded in 96-well plates at concentrations of 1,000 cells per well. Cell proliferation was monitored at different time points (1-5 days). At fixed time points, 20 µl of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) solution were added to each well. Following incubation for 4 h at 37°C, the supernatant was removed and 100 µl of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each well. The absorbance at 490 nm was evaluated using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

In addition, the changes in the IC50 values of cisplatin, taxol and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (LPD) were evaluated in the A2780 cells subjected to PRC1 knockdown or overexpression compared to the controls. The A2780 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at concentrations of 4,000 cells per well and were treated with gradually increasing concentrations of the drugs (as shown in Fig. 5C-F). Following incubation for 48 h at 37°C, 20 µl of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) solution were added to each well. The remaining steps were the same as mentioned above.

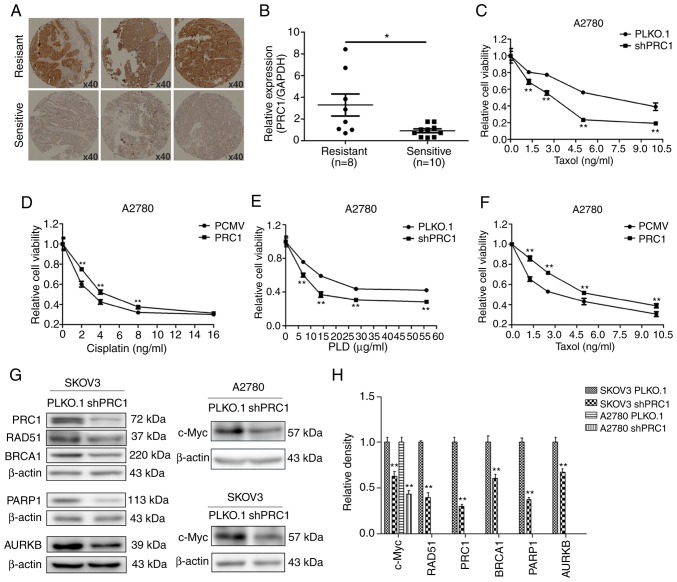

Figure 5.

PRC1 promotes the multi-drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. (A) Expression of PRC1 evaluated by immunohistochemical staining in tissues of patients with second-line platinum-based chemotherapy. (B) PRC1 mRNA expression in patients with information of second-line platinum-based chemotherpay. (C-F) MTT assay was performed to evaluate the changes of IC50 of cisplatin, taxol and LPD in PRC1 knockdown and overexpression cells. (G and H) Western blot and the corresponding densitometric analysis were used to evaluate the changes in the protein levels in the A2780 and SKOV3 cells with PRC1 knockdown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; LPD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; BRCA1, breast cancer 1; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; AURKB, Aurora B kinase.

Colony formation assay

Colony formation assay was used to measure the proliferative ability of the A2780 cells subjected to PRC1 knockdown or overexpression compared to the controls. The A2780 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate with 1,000 cells per well, and cultured at 37°C for 10-14 days. Colonies were fixed with methanol for 15 min and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Solarbio) for 20 min at room temperature. The number of colonies with >50 cells was counted under a microscope (IX71, Olympus).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed to verify whether PRC1 regulates the cell cycle. The A2780 cells transfected with PRC1 siRNA and the controls were harvested and fixed with 75% ice-cold ethanol overnight at 4°C. Cell suspensions were stained with 1 ml propidium iodide stock solution (MultiSciences Lianke Biotech Co.) and analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Transwell assays

Transwell assay was performed to confirm whether RPC1 knockdown and overexpression affected the invasive and migratory abilities of the A2780 and SKOV3 cells. In addition, it was used to determine whether the silencing of PRC1 can reverse the FOXM1-mediated enhancement of the metastatic abilities of the A2780 cells. The cells were re-suspended in serum-free medium, and 200 µl suspension containing 1-2×105 cells was seeded into the upper chambers, and 700 µl culture medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum was added to the lower compartment. The filter membrane of invasion assays was coated with diluted Matrigel (BD Biosciences). The cells that penetrated to the bottom were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Solarbio) at room temperature for >30 min following incubation under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). The incubation times for the migration of the A2780 and SKOV3 cells were 24 and 10 h, and the times for invasion was 36 and 18 h, respectively. A light microscope (IX71, Olympus) was used to examine the cells and obtain images (×100 magnification).

Wound healing assay

To confirm whether PRC1 overexpression in A2780 cells facilitates the migratioryability compared with the control, a wound healing assay was performed. The A2780 cells were seeded in 24-well plate at 3.0×105 per well. A 20 µl pipette tip was used to scratch a line when the cells reached 100% confluency as a monolayer. The cells were then cultured in serum-free medium. The distance between the two edges was monitored at 0 and 48 h following wound formation using a microscope (IX71, Olympus).

Western blot analysis

The fresh tissues and cells were lysed with RIPA buffer on ice. The BCA Protein Assay kit (Merck Millipore) was used to detect the protein concentration of the samples. The mass of protein loaded per lane was 50-90 µg. The sample proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (separating gel, 10%; stacking gel, 5%) and electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membrane was incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C followed by appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature the following day. The ECL system (GE Healthcare) was used to detect the protein bands, and β-actin was used as an endogenous control. The primary antibodies in this study included: Anti-β-actin (1:5,000, F3022, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-PRC1 (1:500, ab51248, Abcam), anti-cyclin B1 (CCNB1; 1:1,000, ab32053, Abcam), anti-cyclin D1 (CCND1; 1:1,000, ab16663, Abcam), anti-Aurora B kinase (AURKB; 1:1,000, ab2254, Abcam), anti-p21 (1:1,000, ab109520, Abcam), anti-E-Cadherin (1:1,000, #3195, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-N-Cadherin (1:1,000, #13116, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)9 (1:1,000, ab38898, Abcam), anti-Slug (1:1,000, ab27568, Abcam), anti-breast cancer 1 (BRCA1; 1:1,000, #9010, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-RAD51 (1:1,000, ab113534, Abcam), anti-poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1; 1:1,000, ab32138, Abcam), anti-c-Myc (1:1,000, ab32072, Abcam) and anti-FOXM1 (1:1,000, ab207298, Abcam). The secondary antibodies were purchased from KPL. Anti-rabbit IgG (5220-0336) was diluted at 1:4,000 and anti-mouse IgG (5220-0341) was diluted at 1:6,000. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, 1.48v) was used to calculate the relative density.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed in 210 cases of HGSOC and 42 normal FT tissues to determine the expression and clinical significance of PRC1 in HGSOC. In addition, the immunohistochemical staining of PRC1 and FOXM1 in corresponding HGSOC samples was analyzed to verify the association between PRC1 and FOXM1. The TMAs were incubated at 60°C for 1 h, and subsequently deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in a degraded series of ethanol. The heat-mediated antigen retrieval in EDTA buffer (pH 9.0), the inactivation of endogenous peroxidase activity and the blocking of non-specific antigens were then performed gradually. PRC1 antibody (1:100 dilution, HPA034521, Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with the slides at 4°C overnight followed by secondary antibodies (SP-9000, ZSBG-BIO) incubation for 20 min at room temperature. Then the sections were incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature. The staining was detected with the DAB detection system (Zhongshan Biotechnology Co.). Two investigators blinded to the clinical data evaluated the staining. Each sample had two duplicates and the average scores were used as the final result.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

To determine whether FOXM1 can regulate the expression of PRC1 and identify the binding site, a dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed. The 293T cells were plated in 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h at 37°C, and transiently co-transfected with PCMV-FOXM1C (RC202540, Origene), PGL4.26-PRC1 (E8441, Promega) and pRL-TK (E2241, Promega) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen™). The luciferase activity was evaluated using the Dual-Glo® Lu ciferase Assay System E2920 which was supplied by Promega. After 24 h, 75 µl fresh medium were added to the 96-well plates after the medium was removed. This was followed by the addition of 75 µl lysis reagent and Firefly luminescence was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad) after 10 min. Subsequently, 75 µl Stop buffer were added to each well and the Renilla luminescence was measured after 10 min. The relative luciferase activity was determined by the ratio of values between Firefly luminescence and Renilla luminescence.

BRCA mutation detection

In order to verify whether PRC1 expression is associated with germline BRCA mutation, germ-line BRCA genetic testing was performed in 52 patients. Fresh blood of 6 ml was extracted and sequenced using the NGS platform from Shanghai Topgen Bio-pharm Co. Ltd. The BRCA1/2 panel (Morgen, China) was used which covers the entire coding sequences of BRCA1 and BRCA2, including 10-50 bases of adjacent intronic sequence of each exon. The variants were classified based on a highly accepted 5-class classification (13).

Bioinformatics analyses

Oncomine (www.oncomine.org) was used to visualize the differential expression of PRC1 in ovarian cancer and control samples. TCGA RNA expression data of ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma were analyzed by the Cancer Genomics Browser (https://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu). Kaplan Meier-plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) was used to analyze overall survival and the progression-free survival of patients as regards PRC1 expression in ovarian cancer. Gene regulation website (www.gene-regulation.com) was used to analyze the promoter of PRC1. Pearson's correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation of PRC1 and FOXM1 expression in TCGA cohort.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 23 software. The differences between continuous data were analyzed using a Student's t-test, and the comparisons between multiple groups were performed by one-way ANOVA, and Fishers' Least Significant Difference (LSD) was used as a post hoc test. The association between PRC1 expression and the clinical characteristics of the patients were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Multivariate cox regression analysis was used to analyze the association between clinical prognostic markers and overall survival. Overall survival analysis was performed by Kaplan-Meier and the log-rank test. A value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

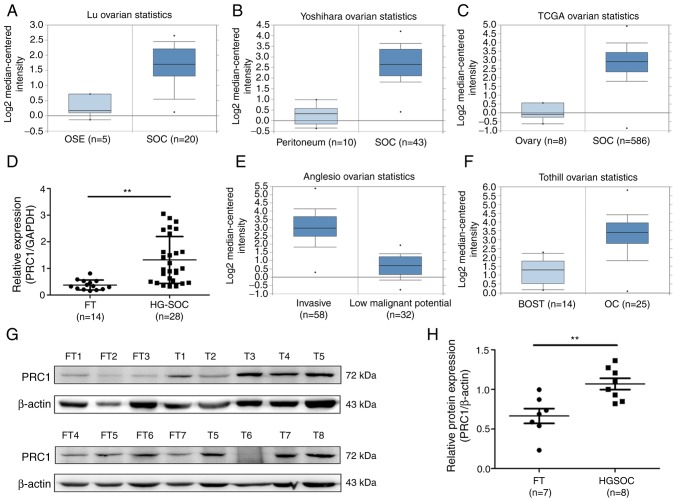

PRC1 is overexpressed in HGSOC

To determine the expression of PRC1 in HGSOC, the publicly accessible database Oncomine and TCGA cohort were employed to analyze PRC1 mRNA expression, and it was observed that PRC1 mRNA expression in serous ovarian carcinoma (SOC) was significantly higher compared with that in normal ovary tissues or normal peritoneum tissues (Fig. 1A-C). It was also found that the expression of PRC1 was positively associated with the malignancy of ovarian tumors (Fig. 1E and F). To confirm PRC1 overexpression in HGSOC, RT-qPCR was performed to measure PRC1 expression in normal FT (n=14) and HGSOC (n=28) tissues, and it was observed that the PRC1 mRNA level was significantly higher in HGSOC (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, western blot analysis was performed to determine the protein expression levels and the relative protein expression of PRC1 was calculated in normal FT (n=7) and HGSOC (n=8) tissues. The results obtained were similar to those for mRNA expression (Fig. 1G and H). All these results verified that PRC1 was markedly overexpressed in HGSOC tissues at both the mRNA and protein level, and suggested that PRC1 plays an important role in ovarian cancer development and biological characteristics.

Figure 1.

PRC1 is overexpressed in HGSOC. (A and B) PRC1 mRNA expression in SOC samples compared to normal ovary samples and peritoneum tissues from Oncomine. (C) PRC1 mRNA expression of SOC samples compared with normal ovary samples from the TCGA chort. (D) Differential mRNA expression of PRC1 expression in normal FT (n=14) and HGSOC (n=28) tissues was examined by RT-qPCR. (E) PRC1 mRNA expression in SOC with a different invasive ability from Oncomine. (F) PRC1 mRNA expression in borderline ovrian tumors and ovarian cancer from Oncomine. (G and H) The protein expression level and relative protein expression (PRC1/β-actin) of PRC1 in the HGSOC tissues and normal FT tissues were measured by western blot analysis. **P<0.01. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma; FT, fallopian tube.

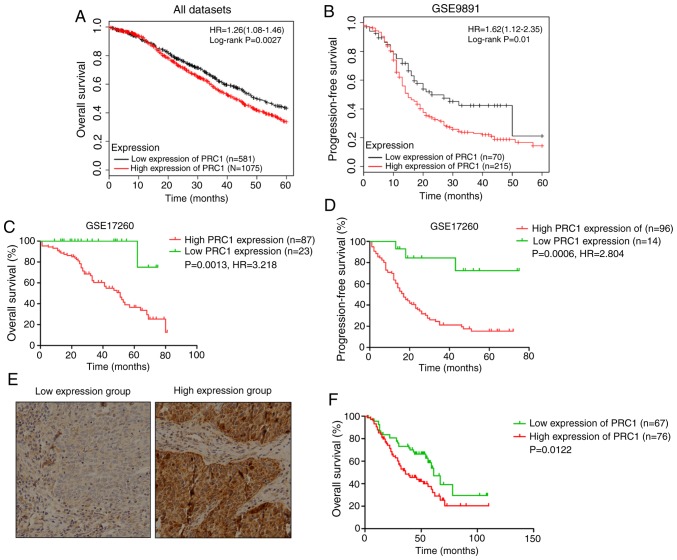

Association between PRC1 expression and clinicopathological parameters

To further determine the expression and clinical significance of PRC1 in HGSOC, an immunohistochemistry assay was conducted to examine PRC1 protein expression in 210 HGSOC tissues and 42 normal FT tissues. As shown in Fig. 2E, PRC1 staining was mainly distributed in the cytoplasm, and the expression of the PRC1 was significantly upregulated in HGSOC tissues. To better understand the significance of PRC1 in HGSOC, the association between the expression of PRC1 and the clinicopathological parameters of 210 patients was analyzed. The results revealed that the overexpression of PRC1 was significantly associated with platinum-based chemotherapy sensitivity and the secondary recurrence intervals (P<0.05). Among the 95 patients with FIGO stage III-IV disease who received satisfactory cytoreductive surgery, 7 patients were resistant to platinum-based chemotherapy, and the staining of these 7 patients, surprisingly, revealed a high expression of PRC1. For second-line chemotherapy, 5 patients had a direct progression of the disease following partial remission among the 18 drug-resistant cases with PRC1 high expression. The primary and secondary recurrence interval and the mean recurrence interval were 12.1 vs. 10.2 months (P>0.05) and 7.3 vs. 4.9 months (P<0.05), respectively. In total, 52 cases of germline BRCA mutations were summarized; 17 cases were BRCA mutation carriers, and 13 of these 17 patients had a low expression of PRC1, with a P-value of 0.019 (Table I). However, no significant association was observed between the expression of PRC1 and the age of the patients, FIGO stage, the CA-125 level, ascites volume, residual lesions, family history and the primary recurrence interval (P>0.05). All the above-mentioned data confirmed that PRC1 played a major role in drug resistance and recurrence of HGSOC.

Figure 2.

Association of PRC1 expression with the clinical outcome of patients with HGSOC. (A-D) Overall survival and progression-free survival of patients as regards PRC1 expression (PRC1 high-expression group vs. and low-expression group) in the TCGA cohort analyzed by Kaplan-Meier Plotter. (E) Representative immunohistochemical staining of PRC1 in HGSOC (magnification, ×200). (F) Kaplan-Meier was used to analyze the overall survival of PRC1 in the high-expression group vs. the low-expression group in the cohort. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

PRC1 contributes to a poor prognosis of patients with HGSOC

Kaplan Meier-plotter was used to investigate the effects of PRC1 expression on clinical prognosis, and the results revealed that the expression of PRC1 was negatively associated with the survival time (Fig. 2A-D). In total, 143 patients with HGSOC with complete survival information were analyzed to evaluate the importance of PRC1 overexpression in predicting HGSOC clinical outcomes according to immunohistochemical staining. It is found that patients with an elevated PRC1 expression had extremely significant poor outcomes in the 3-year survival rate, 5-year survival rate (Table I) and overall survival (Fig. 2F). Notably, multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that a high expression of PRC1 protein was a unique independent prognostic factor for patients with HGSOC (Table II). These results provide evidence that a high expression of PRC1 indicates a worse prognosis of patients with HGSOC.

Table II.

Multivariate analysis of PRC1 protein levels and other clinical prognostic markers related to OS in HGSOC.

| Item | OS

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% Cl) | P-value | |

| Age (≥55/<55 years) | 0.735 (0.412-1.312) | 0.298 |

| FIGO stage (III-IV/I-II) | 0.818 (0.360-1.868) | 0.631 |

| CA-125 (≥500/<500 U/ml) | 1.040 (0.592-1.827) | 0.890 |

| Ascites (≥500/<500 ml) | 0.652 (0.337-1.263) | 0.205 |

| Residual lesions (≥1/<1 cm) | 0.657 (0.381-1.134) | 0.131 |

| PRC1 level (high/low) | 1.970 (1.147-3.384) | 0.014a |

P<0.05. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio.

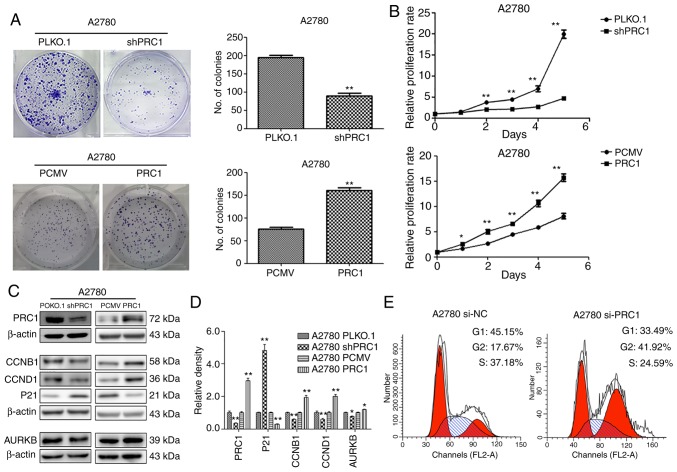

PRC1 promotes ovarian cancer cell proliferation in vitro

To evaluate the biological function of PRC1 in ovarian cancer, stable ovarian cancer cell lines with PRC1 overexpression and knockdown were established. The effect of PRC1 on the proliferative ability of the A2780 cells was then examined. Both growth curve analysis and colony formation assay demonstrated that PRC1 knockdown markedly inhibited cell growth and that PRC1 overexpression significantly enhanced cell proliferation (Fig. 3A and B). To further verify whether PRC1 regulates the cell cycle, PRC1 was knocked down in A2780 cells using siRNA and the changes in the cell cycle were then examined using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. As shown in Fig. 3E, PRC1 depletion significantly increased the percentage of cells in the G2 phase and decreased the percentage of cells in the G1 phase. In addition, the results of western blot analysis revealed that the CCNB1, CCND1 and AURKB expression levels were decreased and p21 expression was increased following PRC1 knockdown, while the corresponding expression levels were reversed with PRC1 overexpression in A2780 cells (Fig. 3C and D). All these results suggested that PRC1 promoted ovarian cancer proliferation in vitro.

Figure 3.

PRC1 increases the proliferative ability of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. (A and B) Clonogenic assay and growth curve assay were used to examine the effects of PRC1 on the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. (C and D) Cell cycle-related proteins and the corresponding densitometric analysis in A2780 cells with PRC1 knockdown and overexpression examined by western blot analysis. (E) Cell cycle analysis of PRC1 knockdown in A2780 cells compared with the control cells analyzed by flow cytometry. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1.

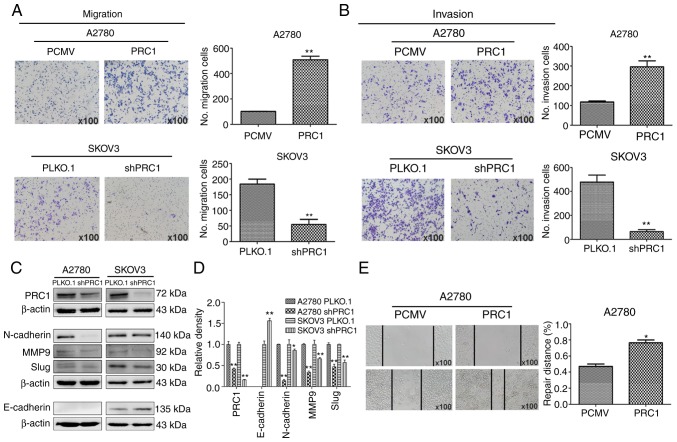

PRC1 promotes the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells in vitro

A wound healing assay was first performed to determine the effects of PRC1 expression on the metastasis of ovarian cancer cells, and the results reveled that PRC1 overexpression in A2780 cells significantly facilitated the migratory ability of the cells compared with the control (Fig. 4E). Transwell assay also revealed that the migratory and invasive ability of the cells was significantly inhibited in the PRC1-depleted cells; on the contrary however, the metastatic ability was enhanced in the PRC1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4A and B). Finally, the levels of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers were measured by western blot analysis, as shown in Fig. 4C and D. The expression of E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, MMP9 and Slug was decreased following PRC1 knockdown. Taken together, all these data suggest an important role of PRC1 in the migratory and invasive ability of ovarian cancer cells via EMT.

Figure 4.

PRC1 promotes the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. (A and B) Effects of PRC1 on the migratory and invasive ability of ovarian cancer cells with PRC1 overexpression or knockdown. (C and D) Western blot analysis of EMT-asssociated markers and the corresponding densitometric analysis in PRC1 knockdown A2780 and SKOV3 cells compared with the control cells. (E) Wound healing assay was used to assess the cell motility in PRC1-overexpressing A2780 cells compared to the control cells. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. PRC1, protein regulator of cytokinesis-1; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9.

PRC1 promotes the multi-drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells in vitro

Immunohistochemical staining was first applied to examine the expression of PRC1 in HGSOC samples with second-line treatment. As shown in Fig. 5A, the expression of PRC1 in the resistant samples was higher than in the sensitive ones. In total, 38.3% (18/47) patients with a high expression of PRC1 were resistant to platinum-based chemotherapy, while only 17.1% (7/41) of patients with a low expression of PRC1 were resistant (Table I). The mRNA expression level of PRC1 in the partial samples with second-line treatment described above was further investigated; it was found that 10 patients were sensitive to platinum, 8 were platinum-resistant, and the expression of PRC1 was evidently higher in the samples of resistant patients (Fig. 5B). Finally, MTT assay was performed to evaluate the changes in the IC50 values of cisplatin, taxol and LPD, and the results revealed that PRC1 knockdown significantly enhanced the sensitivity of the chemotherapeutic drugs (Fig. 5C-F). In addition, it was also found that PRC1 knockdown downregulated BRCA1, RAD51, PARP1 and c-Myc expression in SKOV3 cells and the expression of c-Myc was also downregulated in the A2780 cells (Fig. 5G and H). These results confirmed that PRC1 played an important role in the drug resistance of ovarian cancer.

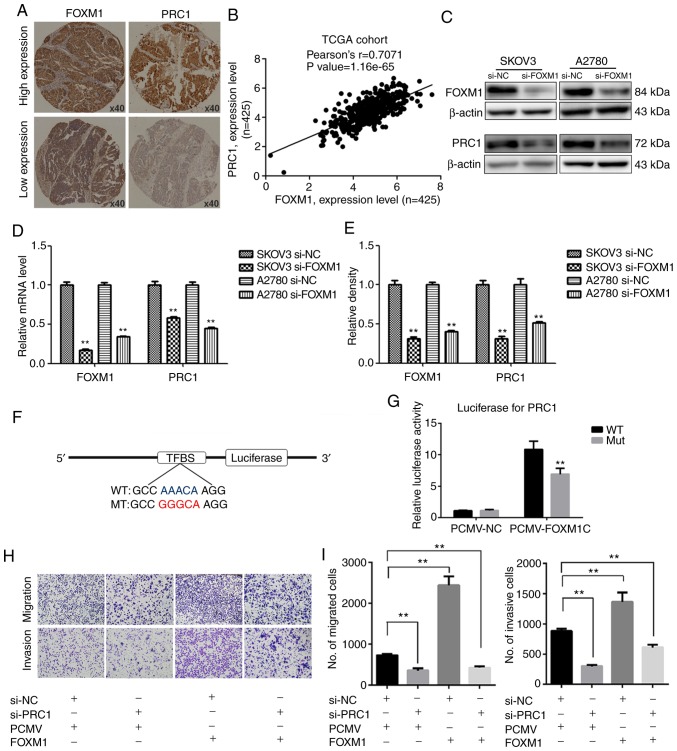

FOXM1 activates the expression of PRC1 through binding to its promoter directly

The promoter of PRC1 was analyzed using a gene regulation website (www.gene-regulation.com), and it was found that a number of transcription factors could bind to its promoter, including FOXM1. The expression of PRC1 was found to positively correlate with the expression of FOXM1 in the TCGA cohort analysis (Fig. 6B). It was found that the expression of PRC1 was markedly decreased at both the mRNA and protein level following FOXM1 knockdown (Fig. 6C-E). The results of immunohistochemical staining of corresponding HGSOC samples revealed that the expression of PRC1 was consistent with the expression of FOXM1 (Fig. 6A). The results of luciferase report assay revealed that FOXM1 activated the expression of PRC1 by directly binding to the promoter of PRC1 and PRC1 luciferase activity was decreased when the binding site was mutated (Fig. 6F and G). To determine whether PRC1 serves as a downstream target of FOXM1, PRC1 was knocked down in FOXM1-overexpressing cells. Transwell assay was then used to determine whether the silencing of PRC1 could reverse the FOXM1-mediated increase in the metastatic ability of A2780 cells. As shown in Fig. 6H and I, the silencing of PRC1 inhibited the FOXM1-mediated promotion of the migratory and invasive ability of the ovarian cancer cells. These results thus suggested that the overexpression of PRC1 was ascribed from the regulation of FOXM1, and it may serve as an important executor.

Figure 6.

PRC1 expression is regulated by FOXM1. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of PRC1 and FOXM1 in corresponding HGSOC samples. (B) Correlation analysis of FOXM1 and PRC1 from the TCGA chort. (C and E) Western blot analysis and corresponding densitometric analysis were used to examine the expression of PRC1 following FOXM1 knockdown in SKOV3 and A2780 cells. (D) The mRNA expression of PRC1 following FOXM1 knockdown in SKOV3 and A2780 cells was examined by RT-qPCR. (F and G) Luciferase report assay was used to determine the regulatory association between FOXM1 and PRC1. (H and I) Transwell assay was used to examine the effect on the migratory and invasive ability following PRC1 konckdown in A2780 FOXM1-overexpressing cells. **P<0.01.

Discussion

Although ovarian cancer is not the most common malignant tumor of gynecological cancers, it is the most lethal, and despite advances being made in surgical and chemotherapy management, ovarian cancer mortality has remained virtually unaffected (14,15). PARP inhibitors targeting BRCA pathogenic mutations are the only major breakthrough made in the treatment of ovarian cancer in recent decades; however, only approximately 20% of patients can benefit from these (16). At present, there is still no systematic mechanism for the pathogenesis, metastasis, drug-resistance mechanisms of ovarian cancer. In this study, it was verified that PRC1 was significantly overexpressed in HGSOC, particularly in patients without BRCA pathogenic mutations, and that its overexpression was strongly associated with the sensitivity of platinum-based chemotherapy and poor prognosis of patients. In addition, we further demonstrated that PRC1 was essential for the function of ovarian cancer cells. As a key target gene of FOXM1, PRC1 is expected to be a novel therapeutic target of ovarian cancers, particularly for patients without BRCA pathogenic mutations.

Proliferation is an important characteristic of life activity, and the manifestation of cellular level is cell division. The accurate entry of cells into the growth and division cycle is a prerequisite for maintaining normal cell proliferation and genomic stability. Cytokinesis is a physical separation of two daughter cells during cell division and is the final stage of the cell cycle. However, the tetraploid and chromosomes instability caused by failure of accurate cell division can promote tumorigenesis and development (17,18). Thus far, the key role of PRC1 has been demonstrated in a variety of malignancies associated with the p53 and Wnt signaling pathways (7-10). However, there is no relevant study available to date on PRC1 in ovarian cancer; to the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first study to describe the key role of PRC1 in ovarian cancer both as regards the clinicopathological features and the mechanisms involved.

In this study, it was confirmed that PRC1 promotes the proliferation, invasion, migration and multi-drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells. The data indicated that PRC1 knockdown was significantly related to mitotic-related genesm including cyclin B1, cyclin D1, p21 and AURKB. Therefore, it was concluded that PRC1 promotes the proliferation of cancer cells through the cytokinesis-related function. Furthermore, AURKB, one of the few effective targets for the treatment of ovarian cancer, was closely related to PRC1 expression. The overexpression or amplification of AURKB is generally detected in a number of of human cancers, such as breast cancer (19), ovarian cancer (20-23), gastrointestinal cancer (24) and other tumors (25-29) and is associated with drug resistance and a poor prognosis. c-Myc has been reported in most types of human malignancies (30,31), and integrated genome analysis of ovarian carcinoma using the TCGA project have revealed that c-Myc is one of the 8 common genes that are amplified in 30-60% of human ovarian carcinomas at the somatic level (32,33). Targeting c-Myc in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer has been confirmed as a potential therapeutic method (34). In summary, PRC1 knockdown can enhance the sensitivity of chemotherapeutic drugs by downregulating the expression of AURKB and c-Myc.

EMT is a process through which epithelial cells lose cell polarity and homogenous adhesion, and gain migratory and invasive properties (35). In recent studies, EMT has been confirmed to be associated with drug resistance in hepatic carcinoma (36-38), colorectal cancer (39-41), gastric cancer (42), breast cancer (43,44) and non-small cell lung cancer (45). This study confirmed that PRC1 expression was closely related to E-cadherin, N-cadherin, MMP9 and Slug, which participated in the important process of EMT, and mediated the invasion, migration and drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells.

More importantly, this study obtained results from the analysis of clinical data which are worthy of mention. It is well known that chemo-resistance causes disease relapse and metastasis, remaining the main obstacle to cancer therapy. Previous studies have indicated that the aberrant expression of PRC1 may point to biochemical recurrence and a poor prognosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma (9) and hepatic carcinoma (7). In this study, it was confirmed that PRC1 over-expression led to platinum-based chemo-resistance both in the first line and second line. PRC1 overexpression shortened the recurrence interval, and furthermore, PRC1 was an independent risk factor of overall survival. Although the experiments in this study confirmed that PRC1 was associated with metastasis in vitro, there was no significant difference found in the FIGO stage, and this may be related to the failure of the early diagnosis of ovarian cancer. All these results suggest that PRC1 may prove to be a therapeutic target with great potential.

FOXM1 is a tumorigenic transcription factor of the forkhead family, and has been confirmed to play a crucial role in the proliferation and progression of multiple tumor cells. FOXM1 is overexpressed in >20 human tumors and promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis and the chemo-resistant processes of ovarian cancers (46-50). In addition, the overexpression of FOXM1 has been shown to significantly reduce the survival of ovarian cancer patients (51). In this study, it was confirmed that PRC1 was a direct downstream gene of FOXM1 via mRNA and protein expression verification and luciferase assay. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the silencing PRC1 inhibited the invasive and migratory ability of FOXM1-overexpressing ovarian cancer cells.

In conclusion, this study verified the expression pattern, molecular mechanisms and clinical information of PRC1 in HGSOC, and confirmed that the upregulated expression of PRC1 enhanced the proliferation, invasion, migration and multi-drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. Clinical data analysis also confirmed the key role of PRC1 in tumor resistance, recurrence and a poor prognosis. The study thus indicated that PRC1 may prove to be a promising molecular target for ovarian cancer, and small molecule inhibitors targeting PRC1 may have desirable anticancer effects.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81874107, 81572554 and 81572559), and the Program for Interdisciplinary Basic Research of Shandong University (grant no. 2018JC014).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

HB and YL contributed to the experimental work, figures and drafting of the manuscript. CJ made substantial contributions to the design of the study and data analysis. HY, XW assisted with the experiments and data analysis. JC, YW and YM assisted with acquisition and analysis of clinical information. YZ and BK designed and supervised all the experiments. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shandong University, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nik NN, Vang R, Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Origin and pathogenesis of pelvic (ovarian, tubal, and primary peritoneal) serous carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:27–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang W, Jimenez G, Wells NJ, Hope TJ, Wahl GM, Hunter T, Fukunaga R. PRC1: A human mitotic spindle-associated CDK substrate protein required for cytokinesis. Mol Cell. 1998;2:877–885. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollinari C, Kleman JP, Jiang W, Schoehn G, Hunter T, Margolis RL. PRC1 is a microtubule binding and bundling protein essential to maintain the mitotic spindle midzone. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurasawa Y, Earnshaw WC, Mochizuki Y, Dohmae N, Todokoro K. Essential roles of KIF4 and its binding partner PRC1 in organized central spindle midzone formation. EMBO J. 2004;23:3237–3248. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Rajasekaran M, Xia H, Zhang X, Kong SN, Sekar K, Seshachalam VP, Deivasigamani A, Goh BK, Ooi LL, et al. The microtubule-associated protein PRC1 promotes early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in association with the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. Gut. 2016;65:1522–1534. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang B, Shi X, Xu G, Kang W, Zhang W, Zhang S, Cao Y, Qian L, Zhan P, Yan H, et al. Elevated PRC1 in gastric carcinoma exerts oncogenic function and is targeted by piperlongumine in a p53-dependent manner. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:1329–1341. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan P, Xi GM, Liu HB, Liu YF, Xu WJ, Zhu Q, Zhou ZJ, Miao YY, Wang XX, Jin JJ, et al. Protein regulator of cytokinesis-1 expression: Prognostic value in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:2054–2060. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhan P, Zhang B, Xi G, Wu Y, Liu HB, Liu YF, Xu WJ, Zhu QQ, Cai F, Zhou ZJ, et al. PRC1 contributes to tumorigenesis of lung adenocarcinoma in association with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:108. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0682-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustin GJ, Vergote I, Eisenhauer E, Pujade-Lauraine E, Quinn M, Thigpen T, du Bois A, Kristensen G, Jakobsen A, Sagae S, et al. Definitions for response and progression in ovarian cancer clinical trials incorporating RECIST 1.1 and CA 125 agreed by the Gynecological Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:419–423. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182070f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, Foulkes WD, Genuardi M, Greenblatt MS, Hogervorst FB, Hoogerbrugge N, Spurdle AB, Tavtigian SV. Sequence variant classification and reporting: Recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/humu.20880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughan S, Coward JI, Bast RC, Jr, Berchuck A, Berek JS, Brenton JD, Coukos G, Crum CC, Drapkin R, Etemadmoghadam D, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: Recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:719–725. doi: 10.1038/nrc3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi T, Wang P, Xie C, Yin S, Shi D, Wei C, Tang W, Jiang R, Cheng X, Wei Q, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer patients from China: Ethnic-related mutations in BRCA1 associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2051–2059. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova EV, Bronson RT, Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature. 2005;437:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature04217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steigemann P, Wurzenberger C, Schmitz MH, Held M, Guizetti J, Maar S, Gerlich DW. Aurora B-mediated abscission checkpoint protects against tetraploidization. Cell. 2009;136:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Jiang C, Li H, Lv F, Li X, Qian X, Fu L, Xu B, Guo X. Elevated Aurora B expression contributes to chemo-resistance and poor prognosis in breast cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:751–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetland TE, Nymoen DA, Holth A, Brusegard K, Flørenes VA, Kærn J, Tropé CG, Davidson B. Aurora B expression in metastatic effusions from advanced-stage ovarian serous carcinoma is predictive of intrinsic chemotherapy resistance. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beussel S, Hasenburg A, Bogatyreva L, Hauschke D, Werner M, Lassmann S. Aurora-B protein expression is linked to initial response to taxane-based first-line chemotherapy in stage III ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:29–35. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson B, Nymoen DA, Elgaaen BV, Staff AC, Tropé CG, Kærn J, Reich R, Falkenthal TE. BUB1 mRNA is significantly co-expressed with AURKA and AURKB mRNA in advanced-stage ovarian serous carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:701–707. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YJ, Chen CM, Twu NF, Yen MS, Lai CR, Wu HH, Wang PH, Yuan CC. Overexpression of Aurora B is associated with poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honma K, Nakanishi R, Nakanoko T, Ando K, Saeki H, Oki E, Iimori M, Kitao H, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Contribution of Aurora-A and -B expression to DNA aneuploidy in gastric cancers. Surg Today. 2014;44:454–461. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0581-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuncel H, Shimamoto F, Kaneko Guangying, Qi H, Aoki E, Jikihara H, Nakai S, Takata T, Tatsuka M. Nuclear Aurora B and cytoplasmic Survivin expression is involved in lymph node metastasis of colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:1109–1114. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeshita M, Koga T, Takayama K, Ijichi K, Yano T, Maehara Y, Nakanishi Y, Sueishi K. Aurora-B overexpression is correlated with aneuploidy and poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;80:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadri-Moskwik M, Weiderhold KN, Deeraksa A, Chuang C, Pan J, Lin SH, Yu-Lee LY. Aurora B is regulated by acetylation/deacetylation during mitosis in prostate cancer cells. FASEB J. 2012;26:4057–4067. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-206656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Premkumar DR, Jane EP, Pollack IF. Cucurbitacin-I inhibits Aurora kinase A, Aurora kinase B and survivin, induces defects in cell cycle progression and promotes ABT-737-induced cell death in a caspase-independent manner in malignant human glioma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:233–243. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.987548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz RJ, Golbourn B, Shekarforoush M, Smith CA, Rutka JT. Aurora kinase B/C inhibition impairs malignant glioma growth in vivo. J Neurooncol. 2012;108:349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vita M, Henriksson M. The Myc oncoprotein as a therapeutic target for human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker VV, Borst MP, Dixon D, Hatch KD, Shingleton HM, Miller D. c-myc amplification in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:340–342. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90069-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prathapam T, Aleshin A, Guan Y, Gray JW, Martin GS. p27Kip1 mediates addiction of ovarian cancer cells to MYCC (c-MYC) and their dependence on MYC paralogs. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32529–32538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reyes-Gonzalez JM, Armaiz-Peña GN, Mangala LS, Valiyeva F, Ivan C, Pradeep S, Echevarría-Vargas IM, Rivera-Reyes A, Sood AK, Vivas-Mejía PE. Targeting c-MYC in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2260–2269. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesen-chymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Zeng S, Ma J, Deng G, Qu Y, Guo C, Shen H. Nestin overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma associates with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:111. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0387-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Q, Wang R, Yang Q, Hou X, Chen S, Hou Y, Chen C, Yang Y, Miele L, Sarkar FH, et al. Chemoresistance to gemcitabine in hepatoma cells induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and involves activation of PDGF-D pathway. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1999–2009. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ju BL, Chen YB, Zhang WY, Yu CH, Zhu DQ, Jin J. miR-145 regulates chemoresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma via epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand) 2015;61:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee TY, Liu CL, Chang YC, Nieh S, Lin YS, Jao SW, Chen SF, Liu TY. Increased chemoresistance via Snail-Raf kinase inhibitor protein signaling in colorectal cancer in response to a nicotine derivative. Oncotarget. 2016;7:23512–23520. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Liu H, Yu J, Yu H. Chemoresistance to doxorubicin induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via upregulation of transforming growth factor beta signaling in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:192–198. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Huang S, Li Y, Zhang W, He K, Zhao M, Lin H, Li D, Zhang H, Zheng Z, Huang C. Decreased expression of LncRNA SLC25A25-AS1 promotes proliferation, chemore-sistance, and EMT in colorectal cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:14205–14215. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng S, Zheng Z, Feng L, Yang L, Chen Z, Lin Y, Gao Y, Chen Y. Proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole inhibits the proliferation, selfrenewal and chemoresistance of gastric cancer stem cells via the EMT/β-catenin pathways. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:3207–3214. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang L, He D, Yang D, Chen Z, Pan Q, Mao A, Cai Y, Li X, Xing H, Shi M, et al. MiR-489 regulates chemoresistance in breast cancer via epithelial mesenchymal transition pathway. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2009–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu SH, Wang CH, Huang ZJ, Liu F, Xu CW, Li XL, Chen GQ. miR-760 mediates chemoresistance through inhibition of epithelial mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:5002–5008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin Z, Guan L, Song Y, Xiang GM, Chen SX, Gao B. MicroRNA-138 regulates chemoresistance in human non-small cell lung cancer via epithelial mesenchymal transition. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westhoff GL, Chen Y, Teng NNH. Targeting Foxm1 improves cytotoxicity of paclitaxel and cisplatinum in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:887–894. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tassi RA, Todeschini P, Siegel ER, Calza S, Cappella P, Ardighieri L, Cadei M, Bugatti M, Romani C, Bandiera E, et al. FOXM1 expression is significantly associated with chemotherapy resistance and adverse prognosis in non-serous epithelial ovarian cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:63. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0536-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen N, Wang Y, Wen L, Zhao SH, Ai ZH, Wang Y, Wu B, Lu HX, Yang H, Liu WC, Li Y. Overexpression of FOXM1 predicts poor prognosis and promotes cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Transl Med. 2014;12:134. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao F, Siu MK, Jiang L, Tam KF, Ngan HY, Le XF, Wong OG, Wong ES, Gomes AR, Bella L, et al. Overexpression of forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) in ovarian cancer correlates with poor patient survival and contributes to paclitaxel resistance. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiu WT, Huang YF, Tsai HY, Chen CC, Chang CH, Huang SC, Hsu KF, Chou CY. FOXM1 confers to epithelial-mesenchymal transition, stemness and chemoresistance in epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2349–2365. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin C, Liu Z, Li Y, Bu H, Wang Y, Xu Y, Qiu C, Yan S, Yuan C, Li R, et al. PCNA-associated factor P15PAF, targeted by FOXM1, predicts poor prognosis in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:2973–2984. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.