Abstract

Objective:

Eating pathology is more prevalent among women compared to men, but prevalence and correlates associated with eating pathology likely vary among subgroups of women. This study examines prevalence and correlates of restrictive and weight control-related eating pathology in sexual minority women.

Method:

Data were collected from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS). Participants reported on sexual orientation, and race, and body mass index (BMI) was derived from interviewer collected height and weight. Participants completed the Body Image Measure and the Eating Attitudes Test-26.

Results:

Sexual minority women reported higher BMIs [F (1, 862) = 14.69, p < .001], higher levels of body dissatisfaction [F (1, 960) = 3.12, p < .01], and higher levels of eating pathology [F (1, 950) = 14.21, p < .001] than heterosexual women. Body dissatisfaction mediated the relationship between BMI and eating pathology, and levels of associations were not attenuated by sexual minority status. Race moderated the association between sexual orientation and eating pathology; compared to all other groups, White sexual minority women had the highest level of eating pathology.

Discussion:

Results indicate that White sexual minority women have higher levels of eating pathology than Black sexual minority women and both Black and White heterosexual women. Future studies that draw from larger and more diverse, community-based samples are needed.

Keywords: body image, body mass index, eating disorders, LGBTQ, race, sexual minority

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders are more prevalent among women than men with a peak onset around 16–20 years of age (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Udo & Grilo, 2018). Body dissatisfaction mediates the relationships between body mass index (BMI) and eating pathology, but these relationships appear to differ by subgroups of women (Lynch, Heil, Wagner, & Havens, 2008). For example, Black women have higher BMIs yet lower body dissatisfaction and lower prevalence of restrictive eating and weight control behaviors, on average, than White women (Bodell et al., 2018; Chao et al., 2008; Quick & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2014; Roberts, Cash, Feingold, & Johnson, 2006; Vaughan, Sacco, & Beckstead, 2008). Differences in cultural norms regarding ideal body size may partially explain these racial differences (Kronenfeld, Reba-Harrelson, Von Holle, Reyes, & Bulik, 2010; Miller et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2006; Rodgers, Berry, & Franko, 2018). Few studies have examined the mediating role of body dissatisfaction on the association between BMI and eating pathology among sexual minority women (i.e., same-sex attracted). Similar to Black women, studies indicate that sexual minority women have higher BMIs and report less body dissatisfaction than heterosexual women on average (Eliason et al., 2015; Laska et al., 2015; Miller & Luk, 2018). Recent reviews present conflicting results on the prevalence of eating pathology among sexual minority women (Calzo, Blashill, Brown, & Argenal, 2017; Meneguzzo et al., 2018). Studies using data from convenience samples find no differences in eating pathology between sexual minority and heterosexual women. In contrast, data derived from population-based samples reveal a higher prevalence of eating pathology among sexual minority women compared to heterosexual women, although race differences were not examined (Meneguzzo et al., 2018).

The present study draws from The Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS), a large population-based study with equal representation of Black and White American young women. In the present study, we examined the prevalence of eating pathology and body dissatisfaction (namely, the desire to be thinner), among sexual minority women, as well as the mediating role of body dissatisfaction on the association between BMI and eating pathology. We hypothesize that: (a) the prevalence of eating pathology and body dissatisfaction will be lower among sexual minority women than heterosexual women; (b) body dissatisfaction will mediate the association between BMI and eating pathology; (c) the associations between BMI, body dissatisfaction and eating pathology, within the mediated model, will be attenuated for sexual minority women; and (d) race will moderate the associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Participants

Data were drawn from 965 Black (57.9%) and White (42.1%) women participating in the PGS. The first wave of the PGS was conducted from 2000 to 2001 and included girls between the ages of 5 and 8 (n = 2,450). Participants completed annual interviews, conducted by trained interviewers, in the home where they answered psychosocial questionnaires. Data from the present analyses were based on interviews conducted from 2010 to 2013 when the participants were 18 years of age. The research was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board.

Race was measured by the response to a single question “What race do you identify as?” Seven response items were given: “White/Caucasian” (39.9%), “Black/African American” (54.8%), “Asian” (0.7%), “Hawaiian/Pacific Islander” (0%), “American Indian/Alaskan Native” (0%), “Other” (0%), and “Multiracial” (4.5%). White and Black women were included in the present analyses. Participants of other racial backgrounds were excluded as they made up only 5.2% of the sample.

Sexual orientation was measured by response to a single question “Which sexes are you attracted to?” Five response options were given: “Only attracted to females” (n = 13; 1.3%), “Mostly attracted to females” (n = 13; 1.3%), “Equally attracted to females and males” (n = 71; 7.4%), “Mostly attracted to males” (n = 100; 10.4%), and “Only attracted to males” (n = 768; 79.6%). Sexual minority status was defined as reporting any same sex attraction (n = 197).

2.2 |. Body mass index

Interviewer-measured height and weight were used to calculate BMI. BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared (Nuttall, 2015).

2.3 |. Body dissatisfaction

Body dissatisfaction was determined using ideal- and self-body image as established by the Body Image Measure (BIM; Collins, 1991). The participant was asked to evaluate seven body silhouettes, ranging from extremely underweight to extremely overweight, and to choose which silhouette best represented her current body image and her ideal body image by answering answered two questions: “Which image looks the most like you?” and “Which image is closest to how you want to look?” Body dissatisfaction was then calculated as the difference between self- and ideal-body image, with scores ranging from −6 to 6. Negative scores indicate body dissatisfaction in the direction of wanting to be heavier and positive scores indicate body dissatisfaction in the direction of wanting to be thinner. In the present study, 45.9% reported no body satisfaction (i.e., no difference between self and ideal image), 11.0% reported a desire to be heavier, and 43.1% reported a desire to be thinner. For the purposes of the present study, participants reporting body image satisfaction (i.e., no difference between self and ideal image) as well as a desire to be heavier were coded as 0. Scores for participants reporting a desire to be thinner ranged from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating larger discrepancies between self and ideal body image.

2.4 |. Eating pathology

Eating pathology was assessed with the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), a reliable and valid self-report measure that assesses concerns about being overweight, eating control, and restriction to reduce weight (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979). EAT-26 scores range from 0 to 78 with higher scores indicating more concerns and eating problems.

2.5 |. Data analytic approach

The analytic strategy proceeded in three steps. First, we conducted one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to examine differences in BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology by sexual orientation. Second, structural equation modeling (SEM) using MPlus (Byrne, 2013) was used to estimate mediation models that characterized the relationships among BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology. Specifically, we estimated direct effects of BMI on eating pathology before and after including body dissatisfaction as a mediator. Three standard model fit indices were used to determine quality of models: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker–Lewis index, and comparative fit index (CFI). Models with RMSEA below 0.1 and TLI and CFI values above 0.95 indicate good model fit. We then tested moderation effects of sexual minority status on the mediation model. We used Wald tests for equality to assess for differences of parameter estimates across groups. Last, we conducted ANOVAs to examine the moderating effect of race on associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology. In the present analyses, sexual orientation and race were measured categorically, and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology were measured continuously.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive statistics for BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology

In the present study, the average BMI was 26.35 (SD = 6.98), with a range from 10 to 53. The average body dissatisfaction score was 0.55 (SD = 0.72), with a range from 0 to 5. The average EAT-26 score was 5.86 (SD = 6.93), with a range from 0 to 77. Sexual minority women had higher BMIs [F (1, 862) = 14.69, p < .001], reported higher levels of body dissatisfaction [F (1, 960) = 3.12, p < .01], and more eating pathology [F (1, 950) = 14.21, p < .001] than heterosexual women.

3.2 |. Mediation effects of body dissatisfaction on the association between BMI and eating pathology

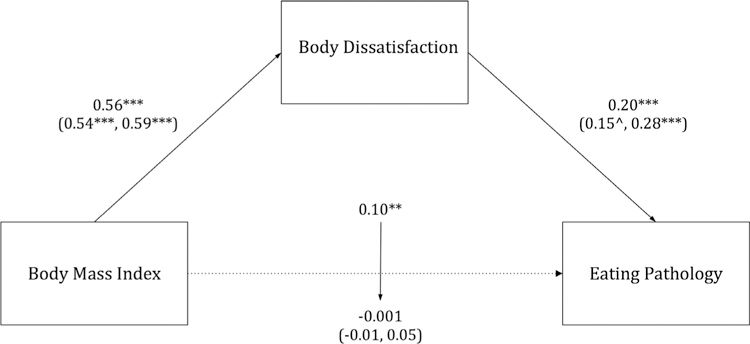

In a multivariate SEM, BMI was positively associated with body dissatisfaction (β = 0.56, p < .001) and body dissatisfaction was positively associated with eating pathology (β = 0.20, p < .01) prior to including body dissatisfaction as a mediator. After including body dissatisfaction, BMI was no longer associated with eating pathology (β = −0.001, p > .1), indicating full mediation. Fit indices for the mediation model suggested that the model fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99) (see Figure 1). Sexual minority status did not moderate the mediated pathway: BMI remained positively associated with body dissatisfaction for sexual minority women (β = 0.59, p < .001) and heterosexual women (β = 0.54, p = <.001). Body dissatisfaction remained positively associated with eating pathology for sexual minority women (β = 0.28, p < .01) and, to a lesser extent, heterosexual women (β = 0.15, p < .05). Both of these effects were not significantly different between sexual minority and heterosexual women. BMI was not associated with eating pathology for either group (p > .1), again indicating that body image mediated the association between BMI and eating pathology in both sexual orientation groups.

FIGURE 1.

Mediation of body dissatisfaction on the association between body mass index and eating pathology among sexual minority (n = 197) and heterosexual young adult women (n = 768) Notes. Figure represents structural equation model of the direct effects of body mass index on eating pathology and indirect effects via body dissatisfaction. All paths shown are significant (p < .05) except for dashed lines. Standardized parameter estimates are provided for overall models with effects shown in parentheses for (heterosexual, sexual minority) participants.^p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01; ***p < .001

3.3 |. Moderation effects of race on the associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology

Lastly, we examined the moderating effect of race on associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology. In these analyses, we conducted ANOVAs with sexual orientation and race entered as separate main effects followed by their interaction. There were significant main effects of sexual orientation on BMI [F (1, 862) = 14.58, p < .001, eta = 0.13] and on eating pathology [F (1, 950) = 16.41, p < .001, eta = 0.12], but not on body dissatisfaction. Race moderated the association between sexual orientation and eating pathology [F (1, 950) = 4.68, p = .031, eta = 0.07]; White sexual minority women had higher eating pathology scores than all other groups, which were on average a half a SD above the sample mean. Race did not moderate the association between sexual orientation and BMI (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Moderation effects of race on the associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology

| Sexual minority |

Heterosexual |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (n = 114) |

White (n = 83) |

Black (n = 445) |

White (n = 323) |

Test statistic (F) |

Sig (p) |

Effect size (eta) |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.99 | 8.13 | 26.78 | 6.55 | 26.85 | 7.48 | 24.45 | 5.14 | 0.03 | .87 | 0.00 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.11 | .74 | 0.00 |

| EAT-26 | 6.46 | 6.33 | 8.96 | 12.24 | 5.40 | 5.45 | 5.48 | 6.89 | 4.68** | .03 | 0.07 |

Notes. EAT-26: Eating Attitudes Test used to measure eating pathology; BMI: body mass index.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to examine the relationships among BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology in sexual minority women within a large, racially diverse, population-based sample. We began by examining whether BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology differ by sexual orientation. Sexual minority women reported higher BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology compared to heterosexual women. We found that body dissatisfaction mediated the relationship between BMI and eating pathology, and, contrary to our hypothesis, sexual minority status did not attenuate the magnitude of the associations in the mediated model. Lastly, we analyzed the moderating effect of race on associations between sexual orientation and BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology. Race moderated the relationship between sexual orientation and eating pathology, such that White sexual minority women had the highest level of eating pathology of all groups, whereas Black sexual minority women had eating pathology levels comparable to the heterosexual groups.

Results from the present study align with the few existing studies drawn from population based samples (e.g., Calzo et al., 2017), indicating that, in general, sexual minority status does not protect women against the broader societal pressure to be thin (Owens, Hughes, & Owens-Nicholson, 2008). Race, however, appears to moderate this relationship. Despite the similarity in body dissatisfaction scores between Black and White sexual minority women, Black sexual minority women reported lower levels of eating pathology than White sexual minority women. These findings underline the importance of diverse samples, and consideration of racial differences in future research on eating pathology in sexual minority women.

The present results should be interpreted in light of study limitations. First, our analyses utilized cross-sectional data and therefore do not allow for examination of temporal relationships among BMI, body dissatisfaction, and eating pathology. [Correction added on 30 March 2019, after first online publication: in the preceding sentence, “body image” and “satisfaction” were removed and replaced with “BMI” and “body dissatisfaction.”] Second, we were unable to examine sexual minority subgroups (i.e., lesbian and bisexual) separately due to insufficient power. Additionally, this study did not examine pathology related to body dissatisfaction for women wanting to be heavier, which may be more common among Black women in comparison to White women. Furthermore, the measure of body dissatisfaction and the EAT-26 are likely correlated, as the EAT-26 includes items measuring the desire to be thinner. Finally, eating pathology was measured using self-reported symptoms on a questionnaire rather than a structured diagnostic interview.

Despite these limitations, results from the present study extend the existing literature. Our findings indicate that White sexual minority women have higher levels of restrictive and weight control-related eating pathology than Black sexual minority women and both Black and White heterosexual women. Future studies focusing on risk and prevention of eating pathology in sexual minority women, which draw from larger, more diverse, population-based samples are necessary.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: R01 HL137246; National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Mental Health, Grant/Award Number: R01 MH056630

REFERENCES

- Bodell LP, Wildes JE, Cheng Y, Goldschmidt AB, Keenan K, Hipwell AE, & Stepp SD. (2018). Associations between race and eating disorder symptom trajectories in black and white girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(3), 625–638. 10.1007/s10802-017-0322-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus : Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge; 10.4324/9780203807644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Blashill AJ, Brown TA, & Argenal RL. (2017). Eating disorders and disordered weight and shape control behaviors in sexual minority populations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(8), 49 10.1007/s11920-017-0801-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao YM, Pisetsky EM, Dierker LC, Dohm F-A, Rosselli F, May AM, & Striegel-Moore RH. (2008). Ethnic differences in weight control practices among U.S. adolescents from 1995 to 2005. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(2), 124–133. 10.1002/eat.20479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins ME. (1991). Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(2), 199–208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Ingraham N, Fogel SC, McElroy JA, Lorvick J, Mauery DR, & Haynes S. (2015). A Systematic Review of the Literature on Weight in Sexual Minority Women. Women’s Health Issues, 25(2), 162–175. 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, & Garfinkel PE. (1979). The eating attitudes test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9(2), 273–279. 10.1017/S0033291700030762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, & Kessler RC. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenfeld LW, Reba-Harrelson L, Von Holle A, Reyes ML, & Bulik CM. (2010). Ethnic and racial differences in body size perception and satisfaction. Body Image, 7(2), 131–136. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska MN, VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Lust K, Eisenberg ME, & Rosser BRS. (2015). Disparities in weight and weight behaviors by sexual orientation in college students. American Journal of Public Health, 105(1), 111–121. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WC, Heil DP, Wagner E, & Havens MD. (2008). Body dissatisfaction mediates the association between body mass index and risky weight control behaviors among White and Native American adolescent girls. Appetite, 51(1), 210–213. 10.1016/j.appet.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneguzzo P, Collantoni E, Gallicchio D, Busetto P, Solmi M, Santonastaso P, & Favaro A. (2018). Eating disorders symptoms in sexual minority women: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(4), 275–292. 10.1002/erv.2601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Gleaves DH, Hirsch TG, Green BA, Snow AC, & Corbett CC. (2000). Comparisons of body image dimensions by race/ethnicity and gender in a university population. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 27(3), 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM, & Luk JW. (2018). A systematic review of sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors among adolescents and young adults: Toward a developmental model. Adolescent Research Review, 4, 1–22. 10.1007/s40894-018-0079-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall FQ. (2015). Body mass index: Obesity, BMI, and health: A critical review. Nutrition Today, 50(3), 117–128. 10.1097/NT.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens LK, Hughes TL, & Owens-Nicholson D. (2008). The effects of sexual orientation on body image and attitudes about eating and weight. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7(1), 15–33. 10.1300/J155v07n01_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick VM, & Byrd-Bredbenner C. (2014). Disordered eating, sociocultural media influencers, body image, and psychological factors among a racially/ethnically diverse population of college women. Eating Behaviors, 15(1), 37–41. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Cash TF, Feingold A, & Johnson BT. (2006). Are black-white differences in females’ body dissatisfaction decreasing? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1121–1131. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RF, Berry R, & Franko DL. (2018). Eating disorders in ethnic minorities: An update. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(10), 90 10.1007/s11920-018-0938-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, & Grilo CM. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Biological Psychiatry, 84(5), 345–354. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CA, Sacco WP, & Beckstead JW. (2008). Racial/ethnic differences in body mass index: The roles of beliefs about thinness and dietary restriction. Body Image, 5(3), 291–298. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]